Abstract

Introduction

The prevalence of hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa is among the world’s highest; however, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in this region are suboptimal. Among other barriers, the overburdened healthcare system poses a great challenge for hypertension control. Community peer-support groups are an alternative and promising strategy to improve adherence and blood pressure (BP) control. The CLUBMEDS study aims to evaluate the feasibility and impact of adherence clubs to improve hypertension control in Nigeria.

Methods and analysis

The CLUBMEDS study will include a formative (pre-implementation) qualitative evaluation, a pilot study and a process (postimplementation) qualitative evaluation. At the formative stages, focus group discussions with patient groups and in-depth interviews with healthcare providers, managers and key decision makers will be conducted to understand the feasibility, barriers and facilitators, opportunities and challenges for the successful implementation of the CLUBMEDS strategy. The CLUBMEDS pilot study will be implemented in two primary healthcare facilities, one urban and one rural, in Southeast Nigeria. Each adherence club, which consists of a group of 10–15 patients with hypertension under the leadership of a role-model patient, serves as a support group to encourage and facilitate adherence, BP self-monitoring and medication delivery on a monthly basis. A process evaluation will be conducted at the end of the pilot study to evaluate the acceptability and engagement with the CLUBMEDS strategy. To date, 104 patients were recruited and grouped into nine clubs, in which patients will be followed-up for 6 months.

Ethics and dissemination

The study was approved by the University of Abuja Teaching Hospital and the Federal Teaching Hospital Abakaliki Human Research Ethics Committees and all patients provided informed consent. Our findings will provide preliminary data on the potential effectiveness and acceptance of this strategy in a hypertension context. Study findings will be disseminated via scientific forums.

Keywords: medication adherence, peer-support groups, adherence clubs, hypertension, anti-hypertensives

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Hypertension prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa is among the world’s highest; however, access to antihypertensive treatment is limited by the significant health system, geographical and financial barriers.

Alternative models of care using community peer-support groups are a promising strategy to overcome these barriers to hypertension control and reach those patients who are not captured in regular healthcare settings.

Adherence clubs, which consists of groups of 10–15 patients with hypertension under the leadership of a role-model patient, might be a promising strategy, serving as a support group to encourage and facilitate adherence, blood pressure self-monitoring and medication delivery.

The CLUBMEDS study, which will include a formative (pre-implementation) qualitative evaluation, a pilot study and a process (postimplementation) qualitative evaluation, aims to evaluate the feasibility and impact of adherence clubs to improve hypertension control in Nigeria.

This study is a pilot study and, therefore, it is limited by its small sample size and short-term follow-up; however, the study findings will provide preliminary data on the potential effectiveness and acceptance of this strategy in a hypertension context.

Introduction

The burden of hypertension in Sub-Saharan Africa and Nigeria

Hypertension is the second leading risk factor for lost disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) in men and the leading risk factor in women globally.1 Despite the global effort to mitigate the impact of hypertension worldwide, it remains a major public health threat, accounting for 10.5 million deaths in 2016.1 The estimated prevalence of hypertension was 28.5% in high-income countries (HICs) and 31.5% in low-to-middle-income countries (LMICs), accounting for 349 million and 1.04 billion people living with hypertension, respectively, in 2010.2 In addition, the estimated awareness, treatment and control rates for hypertension were 37.9%, 29.0% and 7.7%, respectively, in LMICs, whereas in HICs they were estimated to be 67.0%, 55.6% and 28.4%, respectively.2

The prevalence of hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is among the world’s highest, having been reported to vary between 15% and 70% among SSA countries, with an average of 30%.3 Approximately 128.6 million people in SSA were living with hypertension in 2010, having increased from 50.4 million in 2000.2 Furthermore, it is known that mortality and morbidity rates associated with hypertension and its complications, such as ischaemic heart disease, stroke and heart failure, are higher in SSA when compared with other regions of the world.4 This high prevalence of complications is worsened by the low rates of hypertension awareness (27%), treatment (18%) and control (7%) in SSA.3 In addition, many SSA countries struggle to appropriately tackle hypertension, as they face a double burden of communicable and chronic diseases, and often healthcare spending on communicable diseases is prioritised, resulting in hypertension-related healthcare spending not being enough to cover the costs of basic diagnostic equipment, health workers training and treatment supplies.4 5 Nigeria is the most populous country in Africa with an estimated population of 193 million in 2016.6 Like other SSA countries, the prevalence and complication rates of hypertension in Nigeria are high, while hypertension awareness, treatment and control are low. The prevalence of hypertension in Nigeria was estimated to be 22.5%, while hypertension awareness was estimated to be between 14.2% and 30%, treatment between 18.6% and 21.0% and control between 5.0% and 17.5%.7 Therefore, hypertension is a major public health challenge in this country.

Barriers to blood pressure control

There are three major categories of barriers to control of hypertension: (1) patient-related, (2) provider-related, and (3) healthcare system-related.8 9 In Nigeria, a 2014 study evaluated patient-related barriers and found that poor knowledge of the consequences of inadequate blood pressure (BP) control, forgetfulness in taking BP medications and non-affordability of medications were associated with poor hypertension control.10 Another study from Nigeria reported that the main barriers to medication adherence and BP control included healthcare system-related barriers, such as inconvenient clinic operating hours, long waiting times and underdispensing of prescribed medications, when due to the lack of availability of antihypertensive medications the pharmacists dispense a smaller quantity of pills than needed by the patients.11 Patient-related barriers were also reported, such as the lack of knowledge that regular medication use is needed and interruption of the antihypertensive treatment due to side effects or cultural/faith-motivated reasons.11 To overcome some of these barriers, alternative models of care, in which there is a shift of the provision of care and treatment from the healthcare facilities to the community, are needed.

Community-based models of care

The term communitisation of healthcare has been previously used to describe the shift in how healthcare is delivered, in which patients, communities and healthcare systems share the responsibility for finding solutions to healthcare problems and challenges.12 Peer support groups are an example of this concept of communitisation of care. Peer support groups consist of groups of patients with the same health condition, in which the patients support each other and share the challenges, and often the solutions, of living with that specific chronic health condition. Previous studies have shown that peer support groups improve patient experience, adherence, health outcomes and service use among patients with different health conditions, mainly mental illness and HIV/AIDS.12

In the HIV/AIDS context, different types of peer support groups have been studied and shown to be effective. One of these types of peer support groups are the so-called adherence clubs. In these adherence clubs, lay counsellors, who act as the club facilitators, dispense medication to stable patients in a community setting.13–15 The lay counsellors also measure weight, conduct symptom-based general assessments and provide peer support to encourage medication adherence.16 A few studies in patients with HIV/AIDS in South Africa have shown that this club-based strategy improved adherence, reduced virological rebound and improved retention in care.14 17–19

The adherence clubs were proven effective in the HIV/AIDS setting and it has the potential to be translated to other chronic diseases, such as hypertension. However, to date, this club-based strategy has not been evaluated in other chronic disease conditions. Therefore, the CLUBMEDS study aims to evaluate a community club-based strategy to deliver antihypertensive medication to patients with hypertension in Southeast Nigeria.

Methods and analysis

The CLUBMEDS study

The CLUBMEDS study aims to evaluate the feasibility and impact of adherence clubs to improve hypertension control in Nigeria. For a community-based model/strategy to work, it is essential to involve the patients, their relatives and the whole community in the planning and implementation of such strategy. Before implementing any community-based strategy, it is important to understand patients’ preferences, the barriers and facilitators from various stakeholders’ perspectives, including patients, healthcare providers and the health system managers. Therefore, this feasibility evaluation will provide valuable insights for future implementation of a community club-based medication delivery strategy in a larger scale and will guide important adaptations to the model depending on the context it is being implemented.

The CLUBMEDS study will include a formative (pre-implementation) qualitative evaluation, a pilot study and a process (postimplementation) qualitative evaluation.

Patient and Public involvement statement

It is important to acknowledge that patients will be involved in the development of this study.

Formative qualitative evaluation

As part of the CLUBMEDS study, a qualitative evaluation will be done at the formative stage of the strategy. Focus group discussions with patient groups and in-depth interviews with healthcare providers, managers and key decision makers will be conducted to understand the feasibility, barriers and facilitators, opportunities and challenges for the successful implementation of the CLUBMEDS strategy. This qualitative evaluation will also help build ownership of the CLUBMEDS strategy among the stakeholders. We will explore three main conceptual areas: (1) current understanding of hypertension and the health risks associated with it; (2) the challenges faced in accessing and adhering to medications by those who are using antihypertensive medications, and (3) the perceived value and acceptability of future implementation of the CLUBMEDS strategy.

The CLUBMEDS pilot study

The CLUBMEDS pilot study will be implemented in two primary healthcare facilities, one urban and one rural, in Southeast Nigeria. The urban site is located at Abakaliki, the capital city of Ebonyi State. According to the 2006 census, the population in Abakaliki city was 79 280, whereas in the Abakaliki Local Government Area, it was 149 683.20 21 To date, there are no published data on the prevalence of hypertension in Abakaliki, however, a study in a nearby urban city of Enugu with similar population characteristics reported an overall prevalence of hypertension of 42%. The rural site is located at Awkuzu, a town in Oyi Local Government Area of Anambra State. According to the 2006 census, the population of Oyi Local Government Area was 168 201,22 however, there are no published data on the Awkuzu’s population. According to the unpublished report of the Removing the Mask on Hypertension project, prevalence, treatment and control of hypertension in Awkuzu are 18.61%, 8.23% and 1.98%, respectively.

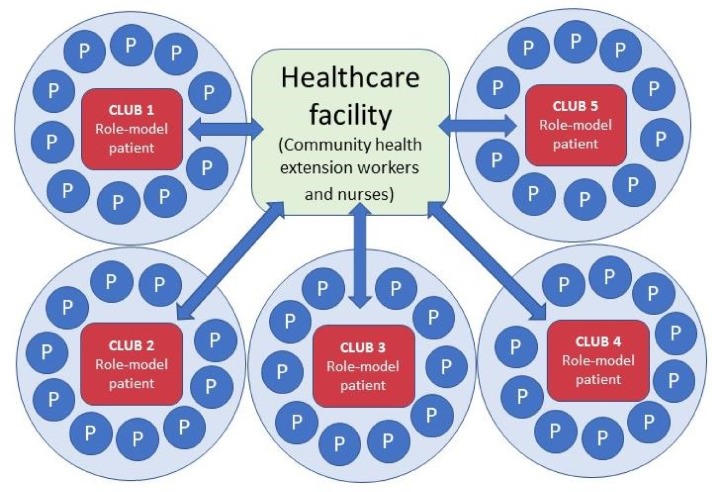

The structure of the CLUBMEDS pilot study will mimic the structure used in the HIV/AIDS adherence clubs. The CLUBMEDS adherence clubs will consist of one role-model patient, who will act as the club facilitator, and between 10 and 15 male and female patients with hypertension, who will be called club members. The adherence clubs will meet on a monthly basis for 6 months. Between three to five adherence clubs will be formed in each primary healthcare facility. As this is a pilot study evaluating the feasibility of the CLUBMEDS strategy, we are aiming to recruit a convenient sample of 100 patients (figure 1). In each primary healthcare facility, community health extension workers (CHEWs) and nurses will be the point of contact for any clinical support to the adherence clubs.

Figure 1.

A model of club-based medication delivery strategy in hypertension context from CLUBMEDS Study being implemented in Nigeria. Note: P refers to a patient or club member.

Recruitment and training

Research nurses working on the CLUBMEDS study will recruit hypertensive patients in each primary healthcare facility to participate in the CLUBMEDS strategy. To be eligible to participate in the study, patients will have to have a confirmed diagnosis of hypertension and be indicated for treatment with antihypertensive medications, irrespective of their level of adherence at baseline. All patients will be required to provide informed consent to participate in the study. After obtaining informed consent, the research nurse will perform a baseline assessment, in which information on demographics, hypertension history, comorbidities, lifestyle risk factors, antihypertensive medications being taken and medication adherence will be collected. In addition, BP measurements will be performed using an automated BP monitor. Among the enrolled patients, the research nurses will then identify and select patients that are eligible to be the role-model patients. To be eligible to be a role-model patient, the selected patients will have to meet the following criteria:

- Be considered adherent to the antihypertensive treatment, if they:

- Have collected the antihypertensive medication every month in the last 6 months.

- Have attended the primary healthcare facility at least twice in the last 6 months.

Have at least secondary school completion.

Agree to take the responsibility of acting as the club facilitator.

After identifying and selecting the role-model patients, the research nurses will provide training on BP monitoring, management of hypertension and how the CLUBMEDS strategy will work to both the role-model patients and the facility CHEWs. CHEWs will participate in a 3-day training programme, whereas role-model patients will receive a simplified and tailored 1-day training programme. The training will include:

- Basic information on hypertension:

- Epidemiology, causes, related risk factors, diagnosis and management of hypertension.

- Information on non-pharmacologic management of hypertension.

- Information on the importance of adherence to antihypertensive medications.

- Information on the importance of regular BP checks.

- Training on:

- How to measure BP appropriately with an automated BP monitor.

- How to identify alert signs, for example, uncontrolled and complications of high BP.

- Management of the adherence clubs, including how to register the patients, record data in the register and distribute the medications to the patients (only to role-model patients).

Finally, the research nurses will help the patients to form the CLUBMEDS adherence clubs by assigning one role-model patient and around 10 to 15 patients with hypertension, the club members, to an adherence club based on their domiciliary proximity. Once the adherence clubs are formed, the patients take responsibility for the overall running of the clubs.

CLUBMEDS monthly sessions

The CLUBMEDS adherence clubs will meet on a monthly basis in a local community centre. The role-model patient and the club members will decide which day and time the clubs will meet on a regular basis, for example, every last Sunday of the month at 6:00 pm. The monthly adherence club meeting will be open for club members’ relatives or friends who wish to attend and support the club members in adhering to their antihypertensive treatment.

The role-model patients will act as the club facilitators, being responsible for preparing and running the club sessions, including the following tasks:

Preparing for the club session, which includes ensuring that the antihypertensive medication refills are ordered at the healthcare facility and ready for pick-up before the club session.

Registering club members by writing the club members’ names in the CLUBMEDS monthly session register when they arrive at the club session.

Measuring the club members’ BP using an automated BP monitor.

Delivering the antihypertensive medications to each club member.

Recording information in the CLUBMEDS monthly session register, including the BP measurements, the number of pills returned by the club members, if any, and the number of pills provided to each club member in the current club session.

Supporting/educating the club members about adherence.

Identifying any symptoms and alert signs for complications of uncontrolled hypertension in the club members, for example, extremely high levels of BP, severe headache, dizziness, blurred vision, nausea/vomiting, nosebleeds, and chest pain/shortness of breath.

Referring club members back to the primary healthcare facility to be evaluated by a CHEW or nurse, if symptom/alert signs are present or, if the club member is due to a regular 6-month check-up at the facility.

After the club session, returning any uncollected medications to the primary healthcare facility and following-up with club members who missed the club session.

Given that their responsibilities are quite extensive, the role-model patients will receive some incentives to be the club facilitators. The role-model patients will be able to keep the automated BP monitor after the study completion and will receive financial support to purchase BP monitor batteries and for transportation to the facility.

The facility CHEWs and nurses will be the point of contact for the role-model patients and club members in the primary healthcare facilities to support the overall conduct of the adherence clubs and to help resolve any adherence-related issues that role-model patients might not be able to address during the club meetings. However, the CHEWs and nurses will not be present in the CLUBMEDS monthly sessions. The facility CHEWs and nurses will be still responsible for the clinical management of the patients participating in the CLUBMEDS study by:

Ensuring the 6 monthly scripting for club members.

Scheduling regular return visits to the facility for club members every 6 months.

Up-titrating or changing the antihypertensive medications.

Evaluating club members with symptoms/alert signs who are referred to the facility by the role-model patients and, if necessary, referring them to the hospital for further evaluation, the Federal Teaching Hospital Abakiliki for club members from the urban facility and the Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University Teaching Hospital Awka for club members from the rural facility.

Supporting the role-model patients in any club-related issues, if necessary.

Due to lack of pharmacists and pharmacist assistants at the facilities, the facility nurses and the CHEWs will be responsible for prepacking the antihypertensive medication refills for the adherence clubs to be collected by the role-model patients before every CLUBMEDS monthly session. There will be no regular physician involvement in the CLUBMEDS strategy due to shortages of physicians working in the primary healthcare facilities involved in the study. In these facilities, non-physicians (CHEWs and nurses) are the ones responsible for seeing and handling the patients’ health issues.

Data collection and outcomes

The CLUBMEDS strategy will be tested for 6 months and the outcome variables to be evaluated during this pilot study are presented in box 1. At 6 months, the role-model patients and club members will be re-assessed by the CLUBMEDS research nurses. Data on medication adherence, BP, hospitalisations due to cardiovascular clinical events and the antihypertensive medications being taken by the participants will be collected by the research nurses. Medication adherence will be assessed using a visual analogue scale, information on the number of pills missed in the last 7 days and pill count. Three BP measurements will be conducted using an automated BP monitor (Omron model 705IT). The first BP measurement will be discarded and the mean value of the last two measurements will be calculated. Data on the club attendance, BP measurements and medication adherence collected during the club sessions will be also evaluated. All data will be entered by the research nurses in a secure password-protected electronic database (REDCap).

Box 1. CLUBMEDS primary and secondary outcomes.

Primary

Medication adherence: visual analogue scale

Secondary

Medication adherence: number of pills missed in the last 7 days and pill count

Blood pressure: resting, sitting automated digital recording, mean of last two readings

Hospital admissions due to cardiovascular clinical events: self-report

Attendance to club sessions: CLUBMEDS monthly session register

Acceptability and engagement with the CLUBMEDS strategy (as part of the process qualitative evaluation)

Statistical analysis

Baseline data will be presented as means and standard deviations (SD) or medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables, and as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. A prepost analysis will be done for the analyses of the study outcomes. Continuous variables will be analysed using t tests and categorical variables using χ2 tests as appropriate. Mann-Whitney U tests will be used if data are not normally distributed.

To further understand the important determinants of medication adherence in our study population, we will perform linear regression analyses using the visual analogue scale as a continuous variable. We will also perform logistic regression analyses using a defined cut-off on the visual analogue scale (eg, adherence >80%). The study team is well aware of the small sample size of the pilot study and, therefore, variable selection for these models will be parsimonious and the results will only be hypothesis-generating.

Process qualitative evaluation

A process evaluation will be conducted at the end of the pilot study (postimplementation stage) to evaluate the acceptability and engagement with the CLUBMEDS strategy. Focus group discussions with club members and in-depth interviews with the role-model patients, CHEWs, nurses and any other healthcare providers involved in the CLUBMEDS study will be conducted to understand the strengths and weaknesses of the strategy, what worked and what did not work, how can the strategy by adapted and improved according to any challenges identified in this pilot study that might preclude the future successful implementation of the CLUBMEDS strategy.

CLUBMEDS progress to date

The recruitment to the CLUBMEDS strategy started in March 2018. Two focus groups (18 male and 20 female participants) and five in-depth interviews were successfully conducted in both the urban and rural sites as part of the formative qualitative evaluation. These qualitative data are currently being analysed and the findings will be published in a separate paper.

To date, 104 patients were recruited to participate in the CLUBMEDS pilot study between March and September 2018, being 82 at the urban site and 22 at the rural site. Nine role-model patients were identified, selected and trained to run the adherence clubs in both sites. Seven adherence clubs were formed in the urban site with between 10 and 13 club members in each club, while two adherence clubs were formed in the rural site with 10 and 13 club members in each club. At the baseline assessment, the recruited CLUBMEDS participants had a mean age of 56.8 years (SD 10.7), 73 (70%) were women and had a mean BP of 146.7/86.9 mm Hg (SD 20.1/11.2). The majority of participants reported taking only one (49.0%) or two (47.1%) antihypertensive medications at the baseline assessment, whereas only 3.8% reported taking three classes of anti-hypertensive medications. The median medication adherence percentage of antihypertensive medications taken by the participants in the past month was 44.5% (IQR 30) measured by the visual analogue scale. The CLUBMEDS monthly sessions are currently being held successfully.

Ethics and dissemination

The findings of this study will be disseminated via scientific forums including peer-reviewed publications and presentations at international and national conferences. The study design and conduct are being overseen by a steering committee (authors), a group of Emerging Leaders from the World Heart Federation. This committee has expertise in large-scale clinical trials, qualitative research and clinical CVD management. This study will adhere to the Declaration of Helsinki, a statement of ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. The study was approved by the University of Abuja Teaching Hospital and the Federal Teaching Hospital Abakaliki Human Research Ethics Committees and all patients provided informed consent.

Discussion

Hypertension is a major public health issue worldwide and even more so in LMICs, such as Nigeria. The current healthcare facility-based model of care has failed to provide appropriate care to ensure adequate BP control in patients with hypertension. Alternative models of care based on shared responsibility between patients, communities and the healthcare system might be the way forward. The CLUBMEDS study is one of the first studies evaluating a community club-based strategy to deliver antihypertensive medication to patients with hypertension in Nigeria, adapting a strategy that was shown to be effective in HIV/AIDS to the hypertension context.

In the HIV/AIDS context, a variety of innovative strategies to increase community engagement in the care and antiretroviral therapy (ART) delivery have been piloted and studied in southern Africa in the last decade.13 15 23 24 Community-based models of ART delivery aim to improve retention in care, by separating drug delivery from clinical visits. From the patient perspective, the main advantages of these strategies are the reduction of travel costs and time spent in frequent clinic visits and peer support encouragement at the community level.13 15 From the healthcare system’s perspective, the major advantages are the reduction of staff workload, keeping the clinical staff focused on clinical problems and the encouragement of patient autonomy.13 15 One of these strategies that have been previously implemented and evaluated is the community-based ART adherence clubs, including facility-based and community-based adherence clubs.13 15

Similar to the CLUBMEDS strategy, in the ART adherence club community-based medication delivery strategy, lay counsellors dispensed the medications to stable patients in a community setting, either in patients’ home or at community venues.13–15 The lay counsellors, who acted as the club facilitators, were also responsible for measuring the patients’ weight, conducting symptom-based general assessments and providing peer support to encourage medication adherence.16 These ART adherence clubs, which had between 15 and 30 patients, met regularly and were supported by a facility nurse.16 An evaluation of the club-based strategy for HIV/AIDS in South Africa showed that <0.1% (9/2133) patients died and 0.3% (53/2133) were referred back to the facility due to clinical complications over 18 months.17 In another study in South Africa, 12% more patients remained in care and were 67% less likely to experience a virological rebound in the club-based strategy compared with clinic-based care.14 18 This club-based strategy has also been shown to reduce costs and have fewer barriers to ongoing access to care, including shorter waiting times, higher acceptability of services and fewer missed clinic appointments.25

An important finding from these studies was that for the club-based strategy to be successful, it was essential that the medications, in this case the ART, were prepackaged and labelled for each patient at the facility, and that the club facilitator collected and transported the packs to the meeting venue. Also, it was important that patients reporting any symptoms or adverse effects, such as weight loss in the HIV/AIDS context, were referred back to the facility to be assessed by a nurse and that all club participants saw a facility nurse at least once a year for their regular clinical check-up.

In the CLUBMEDS study, we will assess if a similar club-based intervention is feasible and effective in improving BP control in the context of hypertension in Nigeria. Although the CLUBMEDS strategy has the potential to address several barriers to adherence to antihypertensive medications, this study has several limitations. First, this is a small feasibility study and, as such, a convenient sample of 100 patients was chosen to be included in the study. Second, the inclusion of both non-adherent and adherent patients in the study might limit the efficacy of the intervention, as adherent patients might not benefit from the intervention as much as non-adherent patients. Third, due to cultural norms, the presence of both men and women as club members might interfere with how these people share their challenges and concerns about adherence in the presence of people of the opposite sex in the monthly club meetings. However, the postimplementation process evaluation will be able to determine whether this was an interfering factor on the participation and success of the CLUBMEDS strategy. Last, financial constraints, medication shortages and the lack of pharmacists, pharmacist assistants, nurses or CHEWs responsible for prepacking the medications in the primary healthcare facilities might limit the scalability of this strategy to other regions of Nigeria and other SSA countries.

If shown to be effective and acceptable to the patients and other stakeholders, the CLUBMEDS strategy has the potential to change the current hypertension scenario, especially in resource-limited settings like many SSA countries, including Nigeria. The CLUBMEDS strategy has the potential of delivering better care to patients with hypertension by involving them, their relatives and their communities in their healthcare. With this engagement, we aim to improve the patients’ knowledge about hypertension, encourage medication adherence and facilitate medication delivering, bringing the medications closer to the patients.

Conclusion

With the growing burden of hypertension in Nigeria and other LMICs, a change in the current model of hypertension management and treatment from the healthcare facility to the community is imperative. If we are to achieve the ‘25×25’ World Heart Federation and WHO target of reducing premature cardiovascular disease mortality by 25% by 2025 worldwide, we need to accelerate our efforts in bringing antihypertensive treatment closer to the population and ensure that at least 50% of eligible people are receiving medications to prevent heart attacks and strokes. A club-based strategy, which was shown to be effective and acceptable in the HIV/AIDS context, can similarly improve the provision of care and treatment to hypertensive patients in resource-limited areas in LMICs. The CLUBMEDS study aims to evaluate a similar club-based strategy in patients with hypertension in Nigeria, where hypertension awareness, treatment and control remain suboptimal. The CLUBMEDS pilot study together with the formative and process qualitative evaluations will provide important preliminary data on the potential implementation of this approach in the hypertension context. If this strategy is shown to be feasible and acceptable, future studies may test the effectiveness of this strategy to improve BP control and longer-term medication adherence in LMICs, such as Nigeria. The CLUBMEDS findings will add to the body of evidence supporting adherence clubs as a way to overcome barriers to optimal treatment adherence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the World Heart Federation Emerging Leaders Programme and Committee who supported and peer-reviewed the content of this research. In particular, the authors thank Mark Huffman, Pablo Perel and Karen Sliwa for their support and enthusiasm. The authors also thank the local staff at the rural and urban primary healthcare facilities for their engagement in this research.

Footnotes

Contributors: KS, GCI, EA, SRM, RP, LM, AO and SV: conceived the original concept of the study and obtained funding as a collaborative group during a one-week international seminar and subsequent meetings through the World Heart Federation Emerging Leaders Programme. GCI, SBF, CU and AO: are involved in the data acquisition locally in Nigeria. KS: drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The CLUBMEDS study is supported by a World Heart Federation Emerging Leaders Programme pilot funding grant.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committees from the University of Abuja Teaching Hospital (UATH/HREC/PR/2017/012/001) and the Federal Teaching Hospital Abakaliki (FETHA/REC/VOL 2/2018/008) and all patients provided informed consent.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Abajobir AA, Abate KH, Abbafati C, et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet 2017;390:1345–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mills KT, Bundy JD, Kelly TN, et al. Global disparities of hypertension prevalence and control: a systematic analysis of population-based studies from 90 Countries. Circulation 2016;134:441–50. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ataklte F, Erqou S, Kaptoge S, et al. Burden of undiagnosed hypertension in sub-saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension 2015;65:291–8. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Echouffo-Tcheugui JB, Kengne AP, Erqou S, et al. High Blood Pressure in Sub-Saharan Africa: the urgent imperative for prevention and control. J Clin Hypertens 2015;17:751–5. 10.1111/jch.12620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. de-Graft Aikins A, Unwin N, Agyemang C, et al. Tackling Africa’s chronic disease burden: from the local to the global. Global Health 2010;6:5 10.1186/1744-8603-6-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nigerian National Bureau of Statistics. National population estimates: population 2006-2016. 2016. http://nigerianstat.gov.ng/elibrary?page=36&offset=350 (Accessed 1 Jun 2018).

- 7. Ogah OS, Okpechi I, Chukwuonye II, et al. Blood pressure, prevalence of hypertension and hypertension related complications in Nigerian Africans: a review. World J Cardiol 2012;4:327–40. 10.4330/wjc.v4.i12.327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ogedegbe G. Barriers to optimal hypertension control. J Clin Hypertens 2008;10:644–6. 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.08329.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Siegel D. Barriers to and strategies for effective blood pressure control. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2005;1:9–14. 10.2147/vhrm.1.1.9.58940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Okwuonu CG, Ojimadu NE, Okaka EI, et al. Patient-related barriers to hypertension control in a Nigerian population. Int J Gen Med 2014;7:345–53. 10.2147/IJGM.S63587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Odusola AO, Hendriks M, Schultsz C, et al. Perceptions of inhibitors and facilitators for adhering to hypertension treatment among insured patients in rural Nigeria: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:624 10.1186/s12913-014-0624-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jain Y, Jain P. Communitisation of healthcare: peer support groups for chronic disease care in rural India. BMJ 2018;360:k85 10.1136/bmj.k85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Medicins Sans Frontieres & Southern Africa Medical Unit (SAMU). Reaching closer to home: progress implementing community-based and other adherence strategies supporting people on HIV treatment. 2013. https://samumsf.org/sites/default/files/2017-07/5_eng_reaching_closer_to_home_2013.pdf (Accessed 1 Jun 2018).

- 14. ART adherence clubs: A long-term retention strategy for clinically stable patients receiving antiretroviral therapy. Southern African Journal of HIV Medicine 2013;14(No 2):2013 10.4102/sajhivmed.v14i2.77 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Community-based antiretroviral therapy delivery: experiences from MSF. Joint United Nations Programme on HI/AIDS (UNAIDS) and Medicins Sans Frontieres. 2015. http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2015/20150420_MSF_UNAIDS_JC2707 (Accessed 1 Jun 2018).

- 16. ART adherence club: Report and Toolkit. Medicins Sans Frontieres. 2014. https://samumsf.org/sites/default/files/2017-07/ART-Adherence-Club-REPORT-and-TOOLKIT_OCT2014.pdf (Accessed 1 Jun 2018).

- 17. Grimsrud A, Sharp J, Kalombo C, et al. Implementation of community-based adherence clubs for stable antiretroviral therapy patients in Cape Town, South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc 2015;18:19984 10.7448/IAS.18.1.19984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Luque-Fernandez MA, Van Cutsem G, Goemaere E, et al. Effectiveness of patient adherence groups as a model of care for stable patients on antiretroviral therapy in Khayelitsha, Cape Town, South Africa. PLoS One 2013;8:e56088 10.1371/journal.pone.0056088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bango F, Ashmore J, Wilkinson L, et al. Adherence clubs for long-term provision of antiretroviral therapy: cost-effectiveness and access analysis from Khayelitsha, South Africa. Trop Med Int Health 2016;21:1115–23. 10.1111/tmi.12736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Population in Abakaliki city. 2006. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abakaliki (Accessed 18 Oct 2018).

- 21. Population in Abakaliki Local Government Area. 2006. https://www.citypopulation.de/php/nigeria-admin.php?adm2id=NGA011001 (Accessed 18 Oct 2018).

- 22. Population in Oyi Local Government Area. 2006. https://www.citypopulation.de/php/nigeria-admin.php?adm2id=NGA004021 (Accessed 18 Oct 2018).

- 23. Decroo T, Rasschaert F, Telfer B, et al. Community-based antiretroviral therapy programs can overcome barriers to retention of patients and decongest health services in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Int Health 2013;5:169–79. 10.1093/inthealth/iht016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Haberer JE, Sabin L, Amico KR, et al. Improving antiretroviral therapy adherence in resource-limited settings at scale: a discussion of interventions and recommendations. J Int AIDS Soc 2017;20:21371 10.7448/IAS.20.1.21371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bango FWL, Van Cutsem G. Cleary S: Cost-effectiveness of ART adherence clubs for long-term management of clinically stable ART patients International Conference on AIDS and STIs in Africa (ICASA 2013). Cape Town, South Africa, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.