Abstract

Introduction

The clinical course of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN2/3) is characterised by a high spontaneous regression rate. Histological assessment is unable to differentiate between CIN2/3 lesions likely to regress and those likely to persist or progress. Most CIN2/3 lesions are treated by surgical excision, leading to overtreatment of a substantial proportion. In this prospective study, we evaluate the value of DNA methylation of host cell genes, which has shown to be particularly sensitive for the detection of advanced CIN2/3 and cervical cancer, in the prediction of regression or non-regression of CIN2/3 lesions.

Methods and analysis

This is a multicentre observational longitudinal study with 24-month follow-up. Women referred for colposcopy with an abnormal cervical scrape, who have been diagnosed with CIN2/3 and a small cervical lesion (≤50% of cervix) will be asked to participate. Participants will be monitored by 6-monthly cytological and colposcopic examination. In case of clinical progression, participants will receive treatment and exit the study protocol. At baseline and during follow-up, self-sampled cervicovaginal brushes and cervical scrapes will be collected for high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) testing and FAM19A4/miR124-2 methylation analysis. A colposcopy-directed biopsy will be taken from all participants at the last follow-up visit. The primary study endpoint is regression or non-regression at the end of the study based on the histological diagnosis. Regression is defined as CIN1 or less. Non-regression is defined as CIN2 or worse. The secondary study endpoint is defined as HPV clearance (double-negative HPV test at two consecutive time-points). The association between methylation status and regression probability will be evaluated by means of χ2 testing.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval was obtained in all participating clinics. Results of the main study will be submitted for publication in a peer-reviewed journal.

Trial registration number

NTR6069; Pre-results

Keywords: cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, colposcopy, human papillomavirus, DNA methylation, overtreatment, natural history

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Longitudinal data and cervical sample collection from women with untreated CIN2/3 will allow us to study the natural history of these lesions in relation to DNA methylation markers.

Strict criteria for inclusion and 6-monthly cytological and colposcopic evaluation are applied to minimise the risk of missing carcinomas or progression into cervical cancer.

Close surveillance allows for monitoring lesion outcome, yet cervical sampling (including cervical biopsies) may influence the clinical course.

Women are included after diagnosis of CIN2/3 on a cervical biopsy, resulting in the collection of the first study sample after an initial biopsy.

If FAM19A4/miR124-2 methylation analysis proves to predict regression or non-regression, overtreatment of CIN2/3 lesions could be prevented by using this test in clinical management decisions.

Introduction

Current cervical screening programmes serve to detect and treat premalignant lesions (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, CIN, graded 1–3) to prevent invasive cervical cancer. Clinical management of women with an abnormal screening test is based on the histological diagnosis of a cervical biopsy: CIN1 lesions are managed conservatively, whereas CIN2 lesions or worse are generally treated with surgical excision. However, this diagnostic-treatment trajectory is associated with considerable overtreatment as CIN2/3 lesions have high regression rates. An estimated 44%–50% of CIN2% and 32% of CIN3 regress spontaneously,1–3 while ~5% of untreated CIN2 and 12%–31% of untreated CIN3 ultimately progress to cervical cancer.1 4

Because predictive markers for cancer progression of CIN2/3 lesions are lacking, most CIN2/3 lesions are treated similarly by surgical excision, either large loop excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ) or cold knife conisation. While this treatment of CIN2/3 lesions detected through screening programmes led to a dramatic decline in cervical cancer incidence in developed countries, there are several adverse effects. Excisional treatment of cervical lesions is associated with an increased risk of pregnancy-related morbidity due to preterm delivery.5–7 As women receiving cervical treatment are often of reproductive age, distinction between CIN2/3 lesions likely to regress and CIN2/3 lesions likely to progress will be of great clinical and social value. Biomarker testing could guide clinical decision-making, treating only those CIN2/3 lesions likely to progress, thus preventing overtreatment.

To accurately predict the individual cancer risk, adjuvant methods are needed. Although several potential prognostic factors, such as human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 positivity,2 8 9 high HPV viral load10 11 and overexpression of cell cycle regulatory proteins p16INK4A 12–18 and Ki-67,19 have been evaluated, none of these have proven their true clinical prognostic value in CIN2/3 lesions.20 DNA methylation analysis of host cell genes has emerged as a promising biomarker that can distinguish between advanced transforming CIN2/3, with a high short-term risk of cervical cancer, and productive or early transforming CIN2/3 lesions, with a low short-term risk of cervical cancer.21–23 Among other genes, hypermethylation of host cell genes FAM19A4 and miR124-2 has been studied extensively. An increase in methylation levels of these genes is not only related to the degree but also to the duration of CIN2/3 disease, and levels are exceptionally high in cervical samples of women with cervical cancer.22 24 Additionally, a negative FAM19A4/miR124-2 methylation test provides a low long-term cancer risk among HPV-positive women.25 This suggests that the FAM19A4/miR124-2 methylation test is particularly sensitive for CIN2/3 lesions with an increased short-term risk of progression.

In this multicentre observational longitudinal cohort study, we will clinically validate whether FAM19A4/miR124-2 methylation analysis can distinguish CIN2/3 lesions likely to persist and progress from those likely to regress, thus determining the need of immediate treatment versus active surveillance. This could prevent overtreatment and the associated cervical morbidity, which is especially relevant for women of childbearing age.

Methods and analysis

The aim of this study is to clinically validate whether hypermethylation of host cell genes can predict regression or non-regression of CIN2/3, and, consequently, allows distinction between advanced transforming CIN2/3, in need of treatment, and productive or early transforming CIN2/3, for which an active surveillance approach is acceptable.

This is an ongoing multicentre observational longitudinal cohort study with 24-month follow-up. Study inclusion started in May 2017 and takes place in three participating clinics in The Netherlands: OLVG (Amsterdam), Flevoziekenhuis (Almere) and Bergman Clinics (Amstelveen). HPV testing and methylation analysis takes place at the Department of Pathology of Amsterdam UMC, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Women referred to the participating clinics for colposcopy because of an abnormal cervical scrape, who have been diagnosed with a CIN2 or CIN3 on a cervical punch biopsy and who have a small cervical lesion (covering ≤50% of the visible cervix), will be asked to participate in the study. A total of 100 women will be included in this group. In order to be eligible for inclusion, women must meet all of the following criteria: non-pregnant and aged 18–55 years. Women who meet one or more of the following criteria will be excluded from study participation: cervical adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) on histology, history of cervical pathology (ie, CIN1 or worse) in the preceding 2 years, inadequate colposcopy (ie, transformation zone is not fully visible (type 3 transformation zone according to International Federation of Cervical Pathology and Colposcopy guidelines26)), prenatal diethylstilboestrol exposure, concomitant cancer or insufficient Dutch or English language skills.

Informed consent procedure

Women will be informed about the study during their first colposcopy visit to the clinic. During this visit, routine colposcopic examination is performed, the size of the cervical lesion is assessed and a diagnostic cervical punch biopsy for histopathology is taken. Approximately 2 weeks after this initial visit, women will be informed about their histology result of the cervical punch biopsy by their gynaecologist. Women who meet the inclusion criteria and who are willing to participate will be asked to give oral and written informed consent.

Study procedures

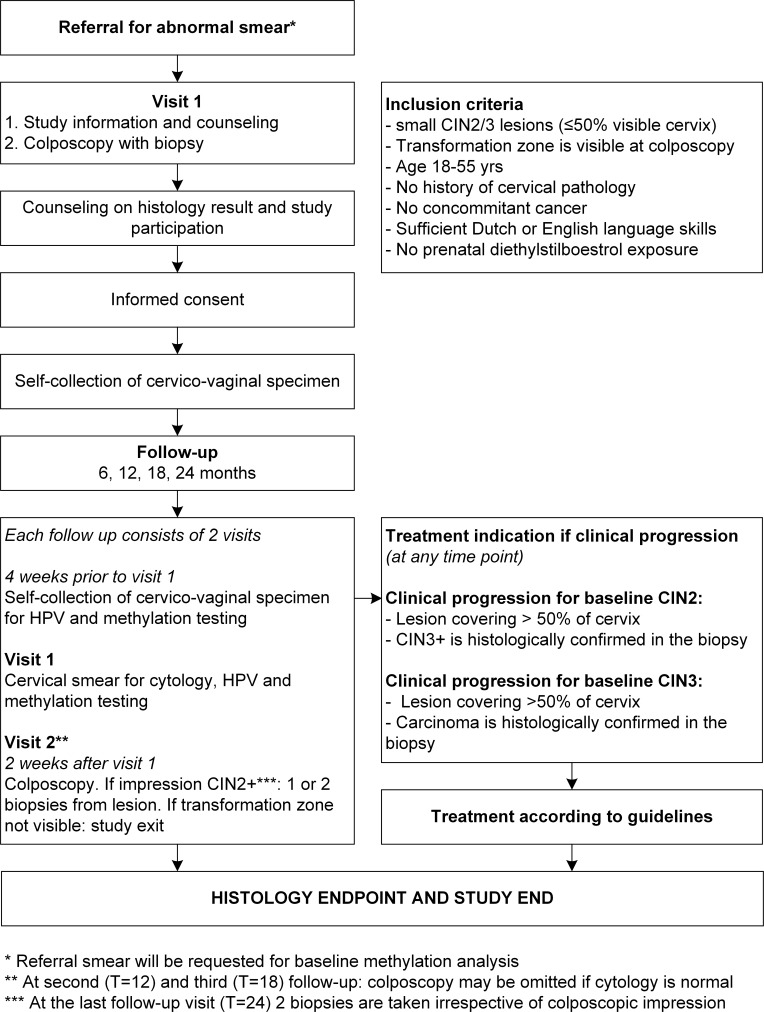

Study participants will receive an Evalyn brush (Rovers Medical Devices B.V., Oss, The Netherlands) directly after inclusion for the self-collection of a cervicovaginal sample which will be used for baseline high-risk HPV testing and methylation analysis. Clinical information regarding medical history, cytological diagnosis, colposcopic impression and a digital colposcopy photo of the lesion will be retrieved through the participating clinics. Participants will be monitored by an intense follow-up schedule with 6-monthly visits to the colposcopy clinic for 2 years. The study flowchart (figure 1) shows all study procedures schematically.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study procedures.

Follow-up will take place at 6, 12, 18 and 24 months after the first visit for colposcopy. Each follow-up consists of two visits. At the first visit of each follow-up, a cervical scrape will be taken by a specialised nurse or gynaecologist for routine cytological evaluation according to CISOE-A classification by a local pathologist.27 28 A few days prior to this visit, participants are requested to use the Evalyn brush for the self-collection of a cervicovaginal sample. The second visit of each follow-up consists of colposcopic examination by an experienced gynaecologist, who will annotate the colposcopic impression, record an image of the cervix and indicate the location of the biopsy (if applicable). Cervical biopsies will be taken according to the colposcopic impression of the gynaecologist. At the last follow-up visit, two exit biopsies are taken from a lesion, or at random if there is no visible lesion. All participants with a CIN2 or worse at this last study visit will receive treatment according to regular care.

If routine cytological evaluation of the cervical scrape shows no abnormalities at 12-month or 18-month follow-up, colposcopic examination may be omitted. This can be decided by the gynaecologist together with the study participant.

Treatment indication

If at any time during follow-up the transformation zone is not completely visible or AIS is found on cervical histology, participants will be excluded from the study protocol and treated. Furthermore, a participant will exit the study and receive treatment if the lesion shows clinical progression.

For women with a CIN2 lesion at baseline, progression is defined as: (1) increase in colposcopic volume of the lesion (covering >50% of visible cervix) at follow-up or (2) follow-up histology of a cervical biopsy showing CIN3 or carcinoma. For women with a CIN3 lesion at baseline, progression is defined as: (1) increase in colposcopic volume of the lesion (covering >50% of visible cervix) at follow-up or (2) follow-up histology of a cervical biopsy showing carcinoma.

Study endpoints

The primary study endpoint is regression or non-regression at the end of the study based on histology of the cervical exit biopsy. All cervical biopsies will be examined by local pathologists, who are blinded to the methylation results, and classified as no dysplasia, CIN1, CIN2, CIN3 or cervical carcinoma according to international standards.29 Regression is defined as a ≤CIN1 diagnosis in the exit biopsy. Non-regression is defined as a CIN2+ diagnosis in the exit biopsy.

It has been shown that HPV-clearance precedes regression of cervical lesions by an average of 3 months.26 Therefore, the secondary study endpoint is defined as HPV clearance (double-negative HPV test at two consecutive time points).

Study parameters

All self-sampled cervicovaginal cells and all cervical scrapes (liquid-based cytology) collected during the study will be stored in ThinPrep PreservCyt Solution (Hologic, Marlborough, Massachusetts, USA). Methylation analysis and high-risk HPV testing will be performed on these samples blinded to the cytology and histology results from routine clinical diagnostics. DNA will be isolated from these samples using the Microlab STAR robotic system (Hamilton, Reno, Nevada, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. HPV DNA detection will be performed using the clinically validated HPV-risk assay (Self-screen B.V., Amsterdam, The Netherlands), a multiplex real-time PCR-based assay that targets the E7 region of 15 (probable) high-risk HPV types (ie, HPV16, HPV18, HPV31, HPV33, HPV35, HPV39, HPV45, HPV51, HPV52, HPV56, HPV58, HPV59, HPV66, HPV67 and HPV68) and enables partial genotyping for HPV16 and HPV18.30 31 For methylation analysis, cervical DNA will be subjected to bisulphite treatment using the EZ DNA Methylation kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, California, USA), and a commercially available, CE-labelled, multiplex quantitative methylation-specific PCR kit (QIAsure Methylation Test, QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) will be used to measure the methylation status of host cell genes FAM19A4 and miR124-2. 21

Sample size calculation

In total, 100 women will be included in the study yielding a width of the 95% CI <20% when assuming a regression probability of 30%. If we assume that the regression probability is 15% for methylation-positive, and 45% for methylation-negative women, and assume that 50% of the women are methylation positive, then a sample size of 100 provides a power of 87% to detect a significant difference in regression probability (significance level 0.05, two-sided).

Statistical analysis

The regression probabilities will be estimated by a binomial proportion. CIs will be constructed by Wilson’s score method. The association between methylation status and regression probability will be evaluated by means of χ2 testing. The results will be adjusted for presence of HPV16 and HPV18.

Monitoring

The study will be monitored for quality and regulatory compliance by Amsterdam UMC. The frequency depends on inclusion rates, questions and pending queries from earlier audits and will be once or twice a year.

Patient and public involvement

No patient advisors were involved in the development and design or conduct of this study. Study results will be disseminated to the study participants via an information letter.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval was obtained in The Netherlands at the Medical Ethics Committee VU University Medical Center (Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016/471). Additional approval was obtained from the participating clinics. The trial is registered with The Netherlands National Trial Registry.

Dissemination to the medical and scientific community will be achieved through publication in peer-reviewed scientific journals and presentation at international scientific conferences.

On completion of the trial and after publication of the primary manuscript, data requests can be submitted to the researchers at Amsterdam UMC, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: WWK, JB, MCGB, DAMH, NEvT, CJLMM and GGK were involved in conception and study design. WWK, CJLMM and GGK were involved in drafting of the article. JB, MCGB, DAMH, NEvT, MWB and HRV were involved in critical revision of the article for important intellectual content. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version. JB provided statistical expertise. WWK, MWB and HRV will be involved in data acquisition. Collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of the report, and the decision to submit the report for publication is the responsibility of GGK, the principal investigator of the study.

Funding: This work was supported by ZonMw grant number 531002010.

Competing interests: DAMH and CJLMM are minority shareholders of Self-screen B.V., a spin-off company of VU University Medical Center; Self-screen B.V. holds patents related to the work (ie, high-risk HPV test and methylation markers for cervical screening); DAMH has been on the speakers bureau of Qiagen and serves occasionally on the scientific advisory boards of Pfizer and Bristol-Myers Squibb; JB received consultancy fees from Roche, GlaxoSmithKline and Merck, and received travel support from DDL. All fees were collected by his employer; CJLMM has received speakers fee from GSK, Qiagen, and SPMSD/Merck, and served occasionally on the scientific advisory board (expert meeting) of GSK, Qiagen, and SPMSD/Merck; CJLMM has a very small number of shares of Qiagen and holds minority stock in Self-screen B.V.; CJLMM is part-time director of Self-screen B.V. since September 2017.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Ostör AG. Natural history of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a critical review. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1993;12:186–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Castle PE, Schiffman M, Wheeler CM, et al. . Evidence for frequent regression of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia-grade 2. Obstet Gynecol 2009;113:18–25. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31818f5008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tainio K, Athanasiou A, Tikkinen KAO, et al. . Clinical course of untreated cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 under active surveillance: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2018;360:k499 10.1136/bmj.k499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McCredie MR, Sharples KJ, Paul C, et al. . Natural history of cervical neoplasia and risk of invasive cancer in women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2008;9:425–34. 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70103-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kyrgiou M, Koliopoulos G, Martin-Hirsch P, et al. . Obstetric outcomes after conservative treatment for intraepithelial or early invasive cervical lesions: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2006;367:489–98. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68181-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arbyn M, Kyrgiou M, Simoens C, et al. . Perinatal mortality and other severe adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: meta-analysis. BMJ 2008;337:a1284 10.1136/bmj.a1284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jin G, LanLan Z, Li C, et al. . Pregnancy outcome following loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2014;289:85–99. 10.1007/s00404-013-2955-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cho HW, So KA, Lee JK, et al. . Type-specific persistence or regression of human papillomavirus genotypes in women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 1: A prospective cohort study. Obstet Gynecol Sci 2015;58:40–5. 10.5468/ogs.2015.58.1.40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Trimble CL, Morrow MP, Kraynyak KA, et al. . Safety, efficacy, and immunogenicity of VGX-3100, a therapeutic synthetic DNA vaccine targeting human papillomavirus 16 and 18 E6 and E7 proteins for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2/3: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial. Lancet 2015;386:2078–88. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00239-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Depuydt CE, Jonckheere J, Berth M, et al. . Serial type-specific human papillomavirus (HPV) load measurement allows differentiation between regressing cervical lesions and serial virion productive transient infections. Cancer Med 2015;4:1294–302. 10.1002/cam4.473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang SM, Colombara D, Shi JF, et al. . Six-year regression and progression of cervical lesions of different human papillomavirus viral loads in varied histological diagnoses. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2013;23:716–23. 10.1097/IGC.0b013e318286a95d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Baak JP, Kruse AJ, Robboy SJ, et al. . Dynamic behavioural interpretation of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia with molecular biomarkers. J Clin Pathol 2006;59:1017–28. 10.1136/jcp.2005.027839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kruse AJ, Skaland I, Janssen EA, et al. . Quantitative molecular parameters to identify low-risk and high-risk early CIN lesions: role of markers of proliferative activity and differentiation and Rb availability. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2004;23:100–9. 10.1097/00004347-200404000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ovestad IT, Gudlaugsson E, Skaland I, et al. . The impact of epithelial biomarkers, local immune response and human papillomavirus genotype in the regression of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grades 2-3. J Clin Pathol 2011;64:303–7. 10.1136/jcp.2010.083626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Miralpeix E, Genovés J, Maria Solé-Sedeño J, et al. . Usefulness of p16INK4a staining for managing histological high-grade squamous intraepithelial cervical lesions. Mod Pathol 2017;30:304–10. 10.1038/modpathol.2016.168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Omori M, Hashi A, Nakazawa K, et al. . Estimation of prognoses for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2 by p16INK4a immunoexpression and high-risk HPV in situ hybridization signal types. Am J Clin Pathol 2007;128:208–17. 10.1309/0UP5PJK9RYF7BPHM [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Guedes AC, Brenna SM, Coelho SA, et al. . p16(INK4a) Expression does not predict the outcome of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2007;17:1099–103. 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.00899.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nishio S, Fujii T, Nishio H, et al. . p16(INK4a) immunohistochemistry is a promising biomarker to predict the outcome of low grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: comparison study with HPV genotyping. J Gynecol Oncol 2013;24:215–21. 10.3802/jgo.2013.24.3.215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kruse AJ, Baak JP, Janssen EA, et al. . Low- and high-risk CIN 1 and 2 lesions: prospective predictive value of grade, HPV, and Ki-67 immuno-quantitative variables. J Pathol 2003;199:462–70. 10.1002/path.1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Koeneman MM, Kruitwagen RF, Nijman HW, et al. . Natural history of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a review of prognostic biomarkers. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2015;15:527–46. 10.1586/14737159.2015.1012068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Steenbergen RD, Snijders PJ, Heideman DA, et al. . Clinical implications of (epi)genetic changes in HPV-induced cervical precancerous lesions. Nat Rev Cancer 2014;14:395–405. 10.1038/nrc3728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. De Strooper LM, van Zummeren M, Steenbergen RD, et al. . CADM1, MAL and miR124-2 methylation analysis in cervical scrapes to detect cervical and endometrial cancer. J Clin Pathol 2014;67:1067–71. 10.1136/jclinpath-2014-202616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bierkens M, Hesselink AT, Meijer CJ, et al. . CADM1 and MAL promoter methylation levels in hrHPV-positive cervical scrapes increase proportional to degree and duration of underlying cervical disease. Int J Cancer 2013;133:1293–9. 10.1002/ijc.28138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. De Strooper LM, Meijer CJ, Berkhof J, et al. . Methylation analysis of the FAM19A4 gene in cervical scrapes is highly efficient in detecting cervical carcinomas and advanced CIN2/3 lesions. Cancer Prev Res 2014;7:1251–7. 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-14-0237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. De Strooper LMA, Berkhof J, Steenbergen RDM, et al. . Cervical cancer risk in HPV-positive women after a negative FAM19A4/mir124-2 methylation test: A post hoc analysis in the POBASCAM trial with 14 year follow-up. Int J Cancer 2018;143:1541–8. 10.1002/ijc.31539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bornstein J, Bentley J, Bösze P, et al. . 2011 Colposcopic Terminology of the International Federation for Cervical Pathology and Colposcopy. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2012. 120:166–72. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318254f90c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hanselaar AG. Criteria for organized cervical screening programs. Special emphasis on The Netherlands program. Acta Cytol 2002;46:619–29. 10.1159/000326965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bulk S, Van Kemenade FJ, Rozendaal L, et al. . The Dutch CISOE-A framework for cytology reporting increases efficacy of screening upon standardisation since 1996. J Clin Pathol 2004;57:388–93. 10.1136/jcp.2003.011841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wright TC, Ronnett BM, Kurman RJ, et al. . Precancerous lesions of the cervix : Kurman RJ, Hedrick Ellenson L, Ronnett BM, Blaustein’s pathology of the female genital tract. 6th edn: Springer, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hesselink AT, Berkhof J, van der Salm ML, et al. . Clinical validation of the HPV-risk assay, a novel real-time PCR assay for detection of high-risk human papillomavirus DNA by targeting the E7 region. J Clin Microbiol 2014;52:890–6. 10.1128/JCM.03195-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Polman NJ, Oštrbenk A, Xu L, et al. . Evaluation of the clinical performance of the HPV-Risk assay using the VALGENT-3 Panel. J Clin Microbiol 2017;55:3544–51. 10.1128/JCM.01282-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.