Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to determine the effectiveness of a proficiency-based progression (PBP) training approach to clinical communication in the context of a clinically deteriorating patient.

Design

This is a randomised controlled trial with three parallel arms.

Setting

This study was conducted in a university in Ireland.

Participants

This study included 45 third year nursing and 45 final year medical undergraduates scheduled to undertake interdisciplinary National Early Warning Score (NEWS) training over a 3-day period in September 2016.

Interventions

Participants were prospectively randomised to one of three groups before undertaking a performance assessment of the ISBAR (Identification, Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation) communication tool relevant to a deteriorating patient in a high-fidelity simulation facility. The groups were as follows: (i) E, the Irish Health Service national NEWS e-learning programme only; (ii) E+S, the national e-learning programme plus standard simulation; and (iii) E+PBP, the national e-learning programme plus PBP simulation.

Main outcome measures

The primary outcome was the proportion in each group reaching a predefined proficiency benchmark comprising a series of predefined steps, errors and critical errors during the performance of a standardised, high-fidelity simulation assessment case which was recorded and scored by two independent blinded assessors.

Results

6.9% (2/29) of the E group and 13% (3/23) of the E+S group demonstrated proficiency in comparison to 60% (15/25) of the E+PBP group. The difference between the E and the E+S groups was not statistically significant (χ2=0.55, 99% CI 0.63 to 0.66, p=0.63) but was significant for the difference between the E and the E+PBP groups (χ2=22.25, CI 0.00 to 0.00, p<0.000) and between the E+S and the E+PBP groups (χ2=11.04, CI 0.00 to 0.00, p=0.001).

Conclusions

PBP is a more effective way to teach clinical communication in the context of the deteriorating patient than e-learning either alone or in combination with standard simulation.

Trial registration number

NCT02886754; Results.

Keywords: handover, simulation, safety, communication, assessment, performance

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first randomised controlled trial of a proficiency-based progression (PBP) educational intervention for a non-technical skill.

The performance outcomes are robust objective measurements that do not rely on subjective assessments or learner perceptions.

Limitations are the single-centre design and the future need for the impact of PBP programmes on patient outcomes.

Introduction

Simulation-based training is being increasingly deployed for both technical and non-technical skill acquisition in healthcare with the aim of reducing medical error and patient harm. There is a need for an evidence-based approach to such training to ensure that the resources used can reliably deliver a quantifiable improved skill set rather than just an enhanced educational experience. Proficiency-based progression (PBP) training is a form of outcomes-based training that involves training individuals to achieve a proficiency benchmark. The process involves ‘deliberate’ practice against a set of clearly defined objective metrics. The proficiency benchmark is set as the mean performance of clinicians who undertake the procedure regularly in clinical practice. It has been shown to improve the performance of individuals undertaking technical procedures.1–7 Metrics are operationally defined to facilitate objective scoring. For example, in the study by Cates et al demonstrating improved performance of carotid angiography, predefined metric errors include ‘number of diagnostic catheters used to obtain diagnostic pictures’ and ‘catheter advancing without a guide-wire in front of it’.6 Despite these results, PBP methodology has not previously been applied to simulation-based training for non-technical skills yet communication failures are a significant source of medical error and preventable adverse events equal if not greater than errors due to lack of technical skill.8–10 Escalation of care for an acutely deteriorating patient demands the most efficient, concise and accurate flow of information among healthcare workers of different disciplines for the best outcome to be achieved.

Early Warning Scores facilitate early detection of deterioration by categorising a patient’s severity of illness and prompting escalation of care at specific trigger points using a structured communication tool such as ISBAR (Identification, Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation). This enables a more timely response using a common language.11 Ireland was one of the first countries to agree and implement a standardised Early Warning Score (National Early Warning Score (NEWS)) across the entire acute hospital sector. NEWS uses the ISBAR tool as the recommended structured communication tool for the acutely deteriorating patient.12 13 The NEWSe-learning programme is recommended as the interdisciplinary education programme for healthcare professionals working in acute services in Ireland. The programme teaches ISBAR as the standardised tool to escalate care in the context of the acutely deteriorating patient.

The primary aim of this study was to determine if the addition of a PBP simulation training programme to the national NEWS e-learning module results in better performance of clinical communication of a deteriorating patient than either the e-learning module alone or in combination with standard simulation.

Methods

Study design

This is a randomised controlled trial with three parallel arms.

Participants

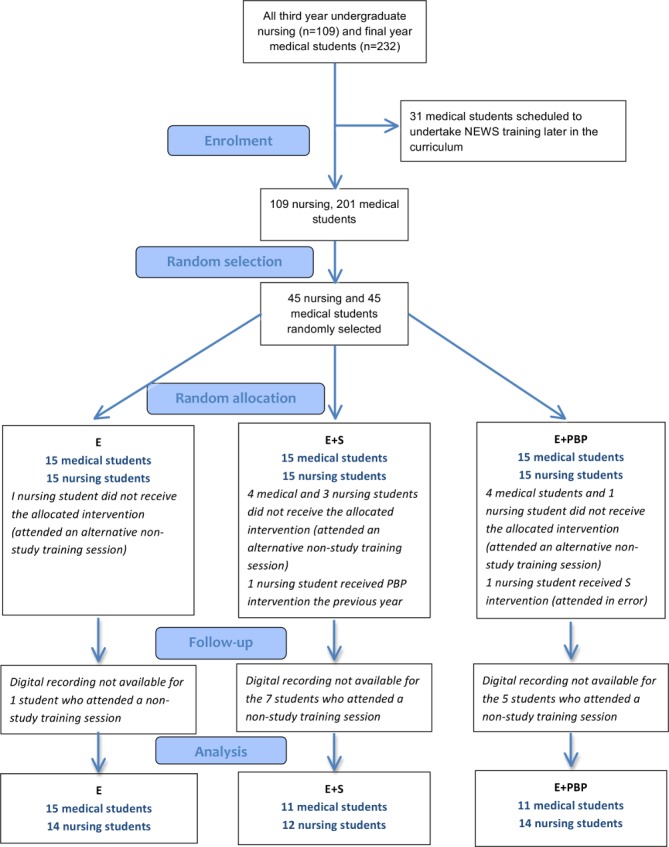

Eligible participants were 109 third year nursing and 201 final year medical students who were scheduled to undertake interdisciplinary NEWS training in September 2016 as part of their undergraduate curriculum. This comprised the entire undergraduate nursing and medical classes except for 31 medical students who were scheduled to undertake this training at a later time in the curriculum (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Consort diagram outlining selection, allocation and follow-up of undergraduate medical and nursing participants in a study comparing the effect of e-learning alone (E), e-learning plus standard simulation (E+S) and e-learning plus proficiency-based progression simulation (E+PBP) on clinical communication. NEWS, National Early Warning Score.

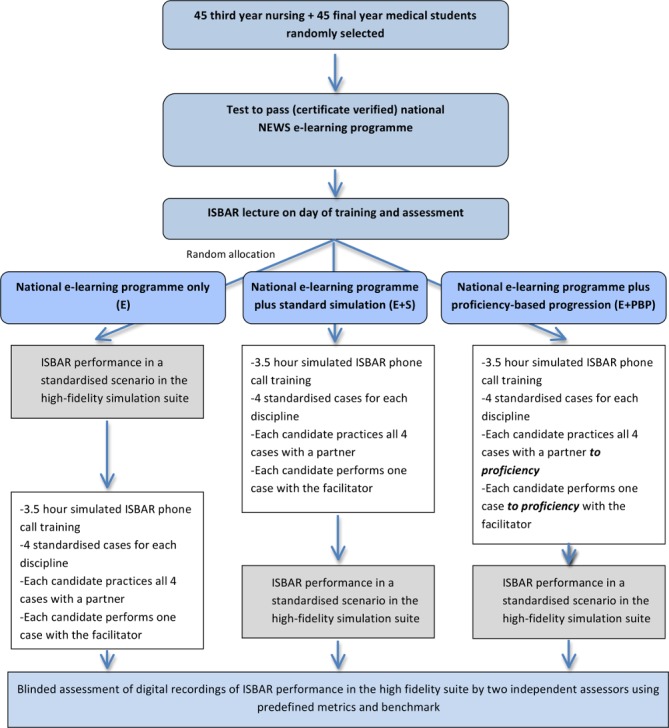

Interventions

All third year nursing and final year medical students were emailed prior to training and instructed to undertake the NEWS e-learning programme. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. On the day of training, participants were required to submit a certificate of successful completion of the e-learning programme. A 15 min lecture on the ISBAR tool was delivered before participants undertook training as per their allocated groups. Students were not notified as to which study group they were allocated. The study flow is outlined in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Outline of experimental design and study flow indicating training interventions and assessment of the three study training groups (E, E+S, E+PBP) of undergraduate medical and nursing participants. ISBAR, Identification, Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation; NEWS, National Early Warning Score.

The three training groups were as follows:

e-learning only group (E)

Participants in this group proceeded immediately following the 15 min lecture to the high-fidelity suite for performance assessment. After outcome assessment was complete, participants undertook simulation training similar to the E+S group as outlined below in order to ensure that all students were afforded the same training opportunity from a curriculum perspective.

e-learning plus standard simulation group (E+S)

Participants worked in pairs of a medical student and nursing student. If a participant did not have a partner, then a non-study peer student was asked to pair with that individual for the purposes of training. Data from the non-study student were not included in the analysis.

Training consisted of a series of simulated phone calls using four standardised paper cases for each discipline. Case materials included case notes, NEWS charts and a blank ISBAR template indicating the categories and type of information that should be communicated. Each scenario had a deteriorating patient event that necessitated an ISBAR telephone communication. Participants alternated between making and receiving simulated phone calls. A standardised script was given to the recipient. Two facilitators conducted the simulation training. Both facilitators were experienced clinicians and educators who had previously undergone the ‘Train the Trainer NEWS programme’ and regularly facilitate NEWS training and healthcare simulation. The facilitators offered support and feedback in line with standard NEWS training by listening to simulated phone calls and offering guidance on the ISBAR framework and by answering questions as they arose. Participants were required to work through all four cases with their partner. Towards the end of the training session, the participants presented to the facilitator to repeat a simulated phone call for either case 3 or 4. The training session was 3.5 hours in duration, and the participants were required to stay until the end of the training regardless of progress. If an individual had completed all the cases, they were asked to assist by continuing to be the recipient of phone calls for their partner or by continuing to practice by repeating the cases if required.

e-learning plus proficiency-based progression simulation group (E+PBP)

Participants underwent a training programme of the same structure, duration (3.5 hours), content and facilitator: student ratio as the E+S group. The same two facilitators facilitated both the E+S and the E+PBP training. However, in the E+PBP group, partners scored each other’s phone calls during training against a series of predefined metrics (quantified as steps, errors and critical errors for each case) on a score sheet to ascertain if the proficiency benchmark for that case was reached. Partners shared the results of the metrics and proficiency scores with each other as feedback at the end of each simulated phone call. If proficiency was not achieved, the case was repeated before progressing to the next case. Participants were required to reach proficiency on all four cases with their partner before performing case 3 or 4 with the facilitator and demonstrating proficiency again. If proficiency was not achieved with the facilitator, then the participant returned to repeat cases with their partner and present for reassessment to the facilitator until proficiency was demonstrated. The training session was 3.5 hours in duration, and the participants were required to stay until the end of the training regardless of progress. If an individual had completed all the cases, they were asked to assist by continuing to be the recipient of phone calls for their partner or by continuing to practice by repeating the cases if required.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the ability to reach the proficiency benchmark on the standardised high-fidelity simulation assessment case. The secondary outcomes were the number of successfully completed steps, errors and critical errors performed by each group.

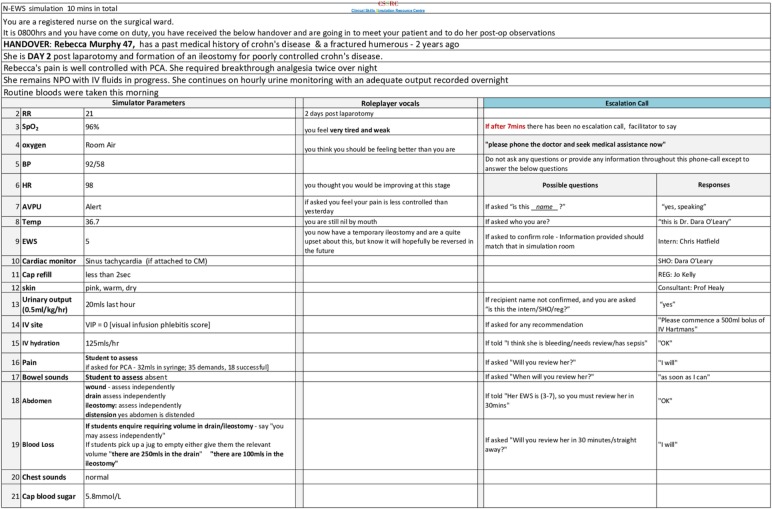

Performance metrics were developed for the training cases and for the high-fidelity simulation assessment case as part of a pilot study in the previous year. Each case presented a different but commonly encountered clinical scenario of an acutely deteriorating patient. As an example, the outline of the nursing component of the high-fidelity simulation assessment case is shown in figure 3.

Figure 3.

Outline of the high-fidelity simulation performance assessment case for nursing undergraduates.

The metrics were derived for each of the training and assessment cases according to the five components of the ISBAR tool and were specific to each case.

The performance metrics were validated through a modified Delphi expert panel consisting of nine senior nurses and eight medical staff who regularly facilitate NEWS/ISBAR communication training. Delphi panel members reviewed the performance metric for each of the simulation cases, and the high-fidelity performance outcome case and metric units were included, excluded or modified by consensus. Each metric unit was then classified as a step, error or critical error by consensus. The majority of metrics were common to both medicine and nursing. The number of metrics per case ranged from 24 to 26.

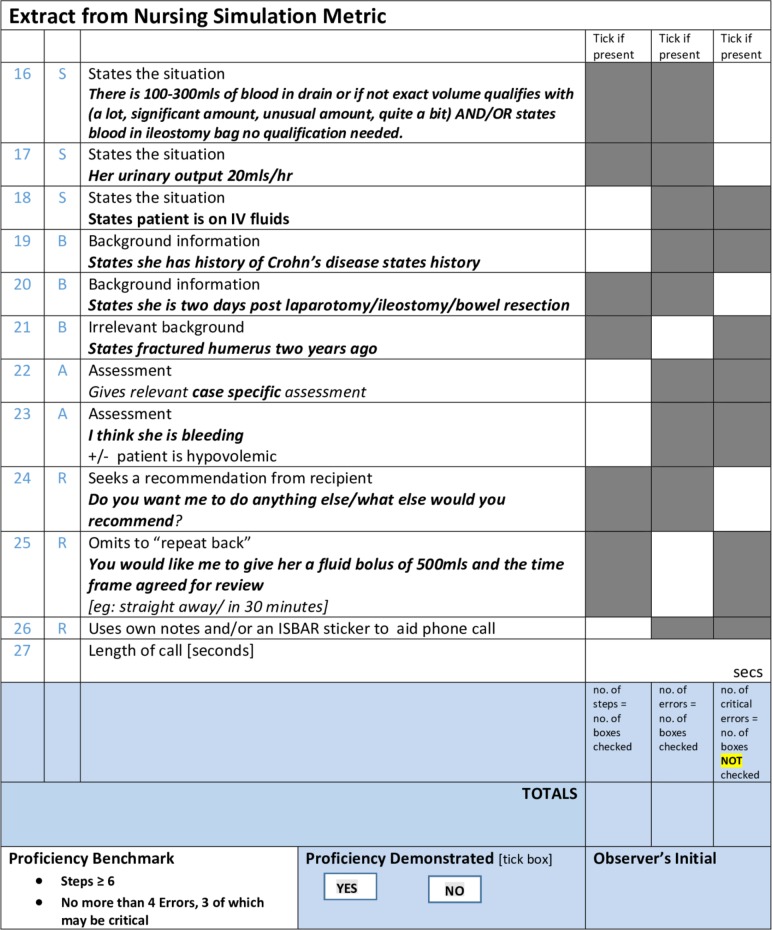

The proficiency benchmark was set as the mean performance of qualified personnel from the respective disciplines on each case. Nine nursing and five medically qualified practitioners (who regularly escalate care in the acute healthcare setting and with a mean years of experience=3 years) underwent the high-fidelity simulation case. The proficiency benchmark for the assessment case was set as the mean performance for each discipline as scored by two independent assessors using the predefined metrics. An extract from the metric scoring sheet and proficiency benchmark for the high-fidelity simulation assessment case is shown in figure 4.

Figure 4.

Extract from the nursing metric scoring sheet illustrating some of the metrics and the proficiency benchmark for the high-fidelity simulation assessment case.

Digital recordings of each participant’s performance of the standardised case in the high-fidelity assessment suite were reviewed and scored by two independent assessors (experienced acute care nurses) using the predefined metrics and proficiency benchmark.

The assessors underwent training on scoring the material using 10 recordings of the same case obtained from non-study participants. Assessment of the digital recordings was undertaken within 2 months of study participation. An inter-rater reliability of >85% was achieved prior to commencing scoring study material. The assessors were not part of the investigator group, were blinded to the study group allocations and had no prior knowledge of any of the participants.

Sample size

Power calculation: the numbers needed in each arm was based on transfer of training (the degree to which trainees transfer the knowledge and skills acquired from one learning situation to another setting) observed in previous studies of PBP simulation in surgery and cardiology, where transfer of training rates of 42%–69% have been observed.1–6 In a pilot for the current study on 133 medical and nursing students in the previous academic year, the transfer of training rate was observed to be 16% for the proficiency-based training group and 3% for the standard simulation group. The pilot, however, was constrained by the existing curriculum, which only allowed for 90 min training time once the e-learning programme was complete. In the current study, a longer training time (3.5 hours) and a more rigorous structure was facilitated. We therefore expected to observe an increase in transfer of training to >40% based on a threefold increase in objective, blind, assessment of proficiency when compared with the control group (ie, 9% for the E group vs 49% for the E+PBP group). A two-tailed test, with n=20 trainees in each group with an alpha of 5% (which corresponds to a 95% CI), would yield a statistical power of 89.9. Therefore, 30 (15 medical and 15 nursing students) were randomised to each group to allow for dropout rates observed in the pilot due to students rescheduling to non-study training dates as a result of conflicting demands of their curriculum.

Randomisation and blinding

A de-identified numbered list of nursing and medical student numbers was obtained from the School of Nursing and Midwifery and the School of Medicine. The lists comprised 109 third year nursing and 201 final year medical students scheduled to complete an interdisciplinary ISBAR training programme as part of the university undergraduate curriculum in September 2016. Randomisation was stratified by discipline and was conducted using a computer-generated programme (GraphPad QuickCals software package, www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs/) as a two-stage process (figure 1).

First, n=45 nursing and n=45 medical students were randomly selected using the programme. These 90 students were then randomly allocated by discipline using the same computer programme to one of the three training groups: E, E+S and E+PBP. Subjects were excluded from the study if (1) a certificate of successful completion (within the previous 4 weeks) of the NEWS e-learning education programme was not presented on the day of training and (2) lack of consent.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS V.22. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to determine if there was a statistical difference between groups in relation to the primary end point (the numbers reaching proficiency) and the secondary end points (the number of completed steps, errors and critical errors). The relationship of the three training programmes on proficiency was explored using logistic regression analysis.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the design or conduct of the study.

Results

Baseline characteristics with respect to age, gender, discipline, nationality and first language of the participants in each group are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the three study groups: e-learning alone (E), e-learning plus standard simulation (E+S) and e-learning plus proficiency-based progression simulation (E+PBP)

| Study group | E | E+S | E+PBP | Total | |

| n=30 | n=30 | n=30 | n=90 | ||

| Discipline | Nursing (%) | 15 (50.0%) | 15 (50.0%) | 15 (50.0%) | 45 (50.0%) |

| Medicine (%) | 15 (50.0%) | 15 (50.0%) | 15 (50.0%) | 45 (50.0%) | |

| Age group | 18–23 years (%) | 21 (70.0%) | 19 (63.3%) | 20 (66.7%) | 60 (66.7%) |

| 24–29 years (%) | 7 (23.3%) | 8 (26.7%) | 9 (30.0%) | 24 (26.7%) | |

| >30 years (%) | 2 (6.7%) | 3 (10.0%) | 1 (3.3%) | 6 (6.7%) | |

| Gender | Male (%) | 6 (20.0%) | 5 (16.7%) | 6 (20.0%) | 17 (18.9%) |

| Female (%) | 24 (80.0%) | 22 (83.3%) | 24 (80.0%) | 73 (81.1%) | |

| Nationality | Irish (%) | 22 (73.3%) | 24 (80.0%) | 21 (70.0%) | 67 (74.4%) |

| Non-Irish (%) | 8 (26.7%) | 6 (20.0%) | 9 (30.0%) | 23 (25.6%) | |

| First language | English (%) | 25 (83.3%) | 22 (73.3%) | 19 (63.3%) | 66 (73.3%) |

| Other (%) | 5 (16.7%) | 4 (13.3%) | 7 (23.3%) | 16 (17.8%) | |

| Not available (%) | – | 4 (13.3%) | 4 (13.3%) | 8 (8.9%) | |

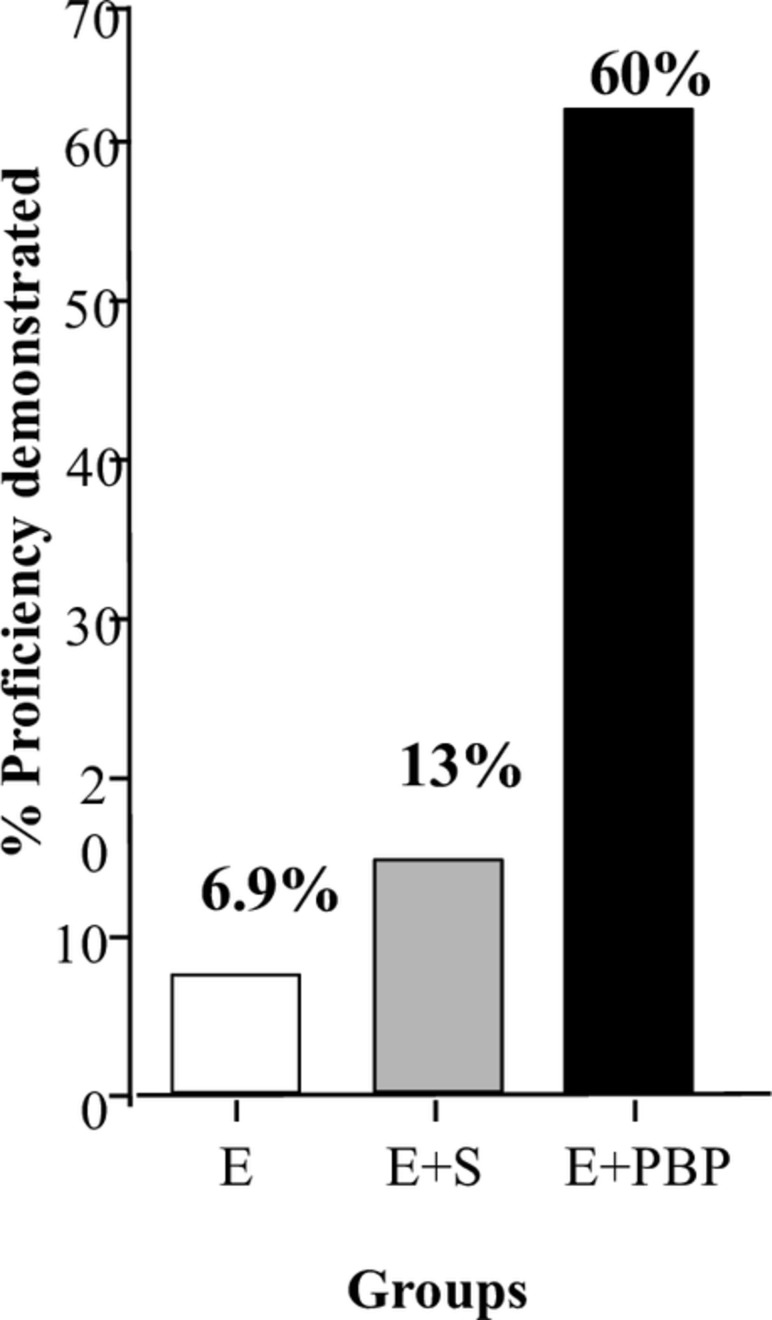

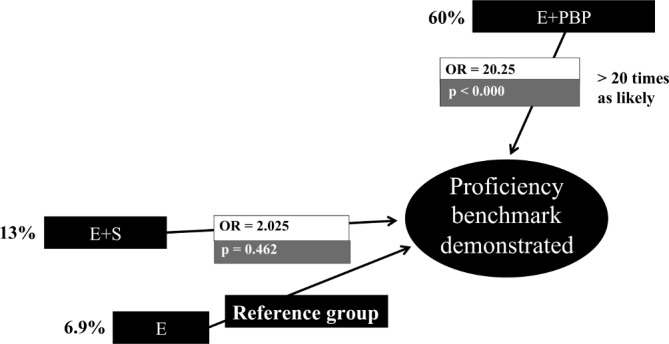

Figure 5 shows percentages of participants in each group who demonstrated the proficiency benchmark following assessment in the high-fidelity simulation suite. At the end of training, 6.9% (2/29) of the e-learning only (E) group and 13% (3/23) of the standard simulation (E+S) group demonstrated proficiency. In comparison, 60% (15/25) of proficiency-based progression simulation (E+PBP) group were proficient. The difference between the E group and the E+S group was not statistically significant (χ2=0.55, 99% CI 0.63 to 0.66, p=0.63) but was significant for the difference between the E group and the E+PBP group (χ2=22.25, CI 0.00 to 0.00, p<0.000) and between the E+S group and the E+PBP group (χ2=11.04, CI 0.00 to 0.00, p=0.001).

Figure 5.

The percentages reaching the proficiency benchmark at the end of training of the three study training groups: e-learning alone (E), e-learning plus standard simulation training (E+S) and e-learning plus proficiency-based progression simulation training (E+PBP).

On logistic regression analysis (figure 6), it was found that in comparison to the E group, the E+PBP trained group were more than 20 times as likely to demonstrate proficiency and the difference was statistically significant (Ext (B)=20.25, 95% CI 3.91 to 105, p<0.000).

Figure 6.

Logistic regression analysis for the relative differences between the three study training groups of undergraduate medical and nursing participants: e-learning alone (E), e-learning plus standard simulation training (E+S) and e-learning plus proficiency-based progression simulation training (E +PBP).

The E+PBP group completed significantly more steps, mean 8.5 (1.7), than either the E group, mean 5.8 (1.6), p<0.000, or the E+S group, mean 6.3 (2.1), p<0.000. Similarly, combined errors and critical errors were significantly less in the E+PBP group, mean 3.7 (1.6), than either the E group, mean 5.9 (2.1), p<0.000, or the E+S group, mean 5.2 (1.5), p<0.01. Inter-rater reliability of the two assessors was 97%.

Discussion

Our results show that addition of a PBP simulation programme to an e-learning module can deliver a superior set of skills for ISBAR communication in relation to a deteriorating patient than an e-learning module either alone or in combination with standard simulation. Furthermore, this benefit is seen within the same resources, that is, materials, timeframe and facilitators as standard simulation. The Irish health service like its international counterparts has prioritised clinical communication as a key part of the patient safety agenda.12–16 Clinical communication is now viewed as an essential skill and training is recommended as mandatory for all health and social care professionals.13 All participants were required to produce a recent certificate of successful completion of the e-learning programme but only 6.9% of the group who undertook the e-learning module only demonstrated the proficiency benchmark. The addition of standard simulation did not significantly improve performance with only 13% of the E+S group reaching the benchmark.

It could be argued that exposure to metrics-based scoring in the practice cases resulted in better performance in the assessment case for the E+PBP group. However, this is precisely the desired effect, that is, that trainees know what skills need to be achieved, practice to achieve them to an objective predefined standard and transfer that training to a dynamic scenario. The E+S and E+PBP groups differed in only two respects: (i) practice was ‘repeated’ in the E+S cohort as opposed to ‘deliberate’ in E+PBP cohort, that is, focused on pre-defined metrics and (ii) the E+PBP group was required to reach proficiency benchmarks to progress through simulation cases whereas the E+S group were not. Our results demonstrate that proficiency-based training can achieve skill acquisition rates of the order of 60%, similar to those seen with technical skills using this approach. In a study of similar experimental design, Angelo et al found that there were 56% fewer intraoperative errors and 69% fewer critical errors when compared with traditional training.2 To our knowledge, our study is the first randomised trial of PBP training of a non-technical skill.

The main strength of the study is the use of robust methodology to determine the effectiveness of an educational intervention on objectively assessed performance outcomes. The study combines the rigour of a randomised controlled trial with that of an outcomes based-training approach (PBP) to clinical communication. A significant body of evidence already exists in relation to the use of PBP for technical skill acquisition.7–13 Our results support the use of PBP training for communication skills also.

Weaknesses of the study include the single-centre design and the application to the undergraduate population only, although the training programme was designed for qualified nurses and doctors also. Since the completion of study, the programme has been applied successfully to both nursing and medical undergraduate programmes in the university setting and to doctors in training in the hospital setting. There is a need for future research on the application of the programme in different clinical settings and its impact on patient outcomes.

The study was limited by the restriction on training time. The duration of simulation training for both E+S and E+PBP groups was extended to 3.5 hours from the initial pilot (1.5 hours), but was still restricted by the existing undergraduate curriculum rather than that which would ideally be required to train a fundamental skill. Skills consolidation is an important part of the learning process particularly for new skills.17 In the study by Angelo et al,2 trainees had a weekend in which to acquire, refine and consolidate their skills before their proficiency assessment at the end of training. Another difficulty, which may have impinged on the effectiveness of training, was the disparity in fidelity between the paper-based training environment and the assessment undertaken in the high fidelity simulation environment. This disparity is challenging for those with limited clinical experience such as the undergraduate population. Van Sickle et al 3 and Gallagher and O’Sullivan4 have commented on the detrimental impact that this disparity can have on proficiency demonstration by trainees.

It is now widely recognised that clinical communication skills underpin patient safety. Implementation of a training programme in relation to clinical communication has already been shown to reduce medical error and preventable adverse events.18 There is a need for valid, reliable, cost-efficient clinical communication training programmes to address this need and the impact on patient as well as healthcare provider outcomes.

In summary, our study shows that PBP is a more effective way to teach clinical communication for the deteriorating patient than e-learning either alone or in combination with standard simulation. Furthermore, improved performance with PBP simulation was achieved with the same training time and facilitator/student ratio as standard simulation.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors listed below met the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria for contributorship as outlined below. DB contributed substantially to the conception and design of the work; the acquisition of the data for the work; drafting the work, revising the work critically for important intellectual content; drafting and approval of the final version to be published; and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. SOB contributed substantially to the conception and design of the work; the acquisition of data for the work; revising the work critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. NMC contributed substantially to the conception and design of the work; the acquisition of data for the work; revising the work critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. AG contributed substantially to the conception and design of the work; the analysis and interpretation of data for the work; revising the work critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. NW contributed substantially to the conception and design of the work; the acquisition of data for the work; revising the work critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Institutional review board approval was obtained. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Consent was not obtained for data sharing but the presented data are anonymised and risk of identification is low.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Gallagher AG, Seymour NE, Jordan-Black JA, et al. Prospective, randomized assessment of transfer of training (ToT) and transfer effectiveness ratio (TER) of virtual reality simulation training for laparoscopic skill acquisition. Ann Surg 2013;257:1025–31. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318284f658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Angelo RL, Ryu RK, Pedowitz RA, et al. A Proficiency-based progression training curriculum coupled with a model simulator results in the acquisition of a superior arthroscopic bankart skill set. Arthroscopy 2015;31:1854–71. 10.1016/j.arthro.2015.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Van Sickle KR, Ritter EM, Baghai M, et al. Prospective, randomized, double-blind trial of curriculum-based training for intracorporeal suturing and knot tying. J Am Coll Surg 2008;207:560–8. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gallagher AG, O’Sullivan GC. Fundamentals of surgical simulation; principles & practices. London: Springer Verlag, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Seymour NE, Gallagher AG, Roman SA, et al. Virtual reality training improves operating room performance: results of a randomized, double-blinded study. Ann Surg 2002;236:458–63. 10.1097/00000658-200210000-00008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cates CU, Lönn L, Gallagher AG. Prospective, randomised and blinded comparison of proficiency-based progression full-physics virtual reality simulator training versus invasive vascular experience for learning carotid artery angiography by very experienced operators. BMJ Simulation and Technology Enhanced Learning 2016;2:1–5. 10.1136/bmjstel-2015-000090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ahlberg G, Enochsson L, Gallagher AG, et al. Proficiency-based virtual reality training significantly reduces the error rate for residents during their first 10 laparoscopic cholecystectomies. Am J Surg 2007;193:797–804. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.06.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wilson RM, Runciman WB, Gibberd RW, et al. The quality in australian health care study. Med J Aust 1995;163:458–71. 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1995.tb124691.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bhasale AL, Miller GC, Reid SE, et al. Analysing potential harm in Australian general practice: an incident-monitoring study. Med J Aust 1998;169:73–6. 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1998.tb140186.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death. Caring to the end? A review of the care of patients who died in hospital within four days of admission: NCEPOD, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Riesenberg LA, Leitzsch J, Little BW. Systematic review of handoff mnemonics literature. Am J Med Qual 2009;24:196–204. 10.1177/1062860609332512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. National Clinical Effectiveness Committee. National early warning score, national clinical guideline. http://health.gov.ie/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/NEWSFull-Report-August2014.pdf

- 13. National Clinical Effectiveness Committee. Communication (Clinical Handover) in Acute and Children’s Hospital Services, National Clinical Guideline. http://health.gov.ie/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/NCG-No-11-Clinical-Handover-Acute-and-Childrens-Hospital-Services-Full-Report.pdf

- 14. British Medical Association. Safe handover: safe patients. Guidance on clinical handover for clinicians and managers. London: BMA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Australian Medical Association. 2006, Safe Handover-safe patients: guidance on clinical handover for clinicians and managers. AMA 2006. https://ama.com.au/sites/default/files/documents/Clinical_Handover_0.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 16. Joint Commission. Joint commission on accreditation of healthcare organizations. National patient safety goals. 2005. https://www.jointcommission.org/PatientSafety/NationalPatientSafetyGoals/

- 17. Keane MT, Eysenck MW. Cognitive pscychology: a student’s handbook: Psychology Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Starmer AJ, Spector ND, Srivastava R, et al. Changes in medical errors after implementation of a handoff program. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1803–12. 10.1056/NEJMsa1405556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.