Abstract

The recent discovery of genetically distinct shrew- and mole-borne viruses belonging to the newly defined family Hantaviridae (order Bunyavirales) has spurred an extended search for hantaviruses in RNAlater®-preserved lung tissues from 215 bats (order Chiroptera) representing five families (Hipposideridae, Megadermatidae, Pteropodidae, Rhinolophidae and Vespertilionidae), collected in Vietnam during 2012 to 2014. A newly identified hantavirus, designated Đakrông virus (DKGV), was detected in one of two Stoliczka’s Asian trident bats (Aselliscus stoliczkanus), from Đakrông Nature Reserve in Quảng Trị Province. Using maximum-likelihood and Bayesian methods, phylogenetic trees based on the full-length S, M and L segments showed that DKGV occupied a basal position with other mobatviruses, suggesting that primordial hantaviruses may have been hosted by ancestral bats.

Subject terms: Viral evolution, Viral reservoirs

Introduction

The long-standing consensus that hantaviruses are harbored exclusively by rodents has been disrupted by the discovery of distinct lineages of hantaviruses in shrews and moles of multiple species (order Eulipotyphla, families Soricidae and Talpidae) in Asia, Europe, Africa and North America1,2. Not surprisingly, bats (order Chiroptera, suborders Yangochiroptera and Yinpterochiroptera), by virtue of their phylogenetic relatedness to shrews and moles and other placental mammals within the superorder Laurasiatheria3,4, have also been shown to harbor hantaviruses1,2. Subsequently, based on phylogenetic analysis of the full-length S- and M-genomic segments, members of the genus Hantavirus (formerly family Bunyaviridae) have been reclassified into four newly defined genera (Loanvirus, Mobatvirus, Orthohantavirus and Thottimvirus) within a new virus family, designated Hantaviridae5,6.

All rodent-borne hantaviruses, as well as nearly all newfound hantaviruses hosted by shrews and moles, belong to the genus Orthohantavirus6. By contrast, bat-borne hantaviruses have been assigned to the Loanvirus and Mobatvirus genera. To date, bat-borne loanviruses include Mouyassué virus (MOYV) in the banana pipistrelle (Neoromicia nanus) from Côte d’Ivoire7 and in the cape serotine (Neoromicia capensis) from Ethiopia8, Magboi virus (MGBV) in the hairy slit-faced bat (Nycteris hispida) from Sierra Leone9, Huángpí virus (HUPV) in the Japanese house bat (Pipistrellus abramus) from China10, Lóngquán virus (LQUV) in the Chinese horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus sinicus), Formosan lesser horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus monoceros) and intermediate horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus affinis) from China10, and Brno virus (BRNV) in the common noctule (Nyctalus noctula) from the Czech Republic11.

Mobatviruses include Xuân Sơn virus (XSV) in the Pomona roundleaf bat (Hipposideros pomona) from Vietnam12,13, Láibīn virus (LAIV) in the black-bearded tomb bat (Taphozous melanopogon) from China14, Makokou virus (MAKV) in the Noack’s roundleaf bat (Hipposideros ruber) from Gabon15, and Quezon virus (QZNV) in the Geoffroy’s rousette (Rousettus amplexicaudatus) from the Philippines16. QZNV is the only hantavirus reported hitherto in a frugivorous bat species (family Pteropodidae).

Several orthohantaviruses hosted by murid and cricetid rodents cause either hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) in Europe and Asia17–19 or hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome (HCPS) in the Americas20,21. HFRS varies in clinical severity from mild to life threatening, with mortality ranging from <1% to ≥15%22,23, whereas HCPS is generally severe, and despite intensive care treatment, mortality rates are 25% or higher24,25. Humans are typically infected with rodent-borne orthohantaviruses by the respiratory route via inhalation of aerosolized excretions or secretions26,27. Transmission of hantaviruses from person-to-person has been reported only with Andes virus in Argentina28 and Chile29,30.

The pathogenicity of the newfound shrew-, mole- and bat-borne hantaviruses is unknown. That is, despite a report of IgG antibodies against recombinant nucleocapsid proteins of shrew-borne hantaviruses in humans from Côte d’Ivoire and Gabon31, there is no definitive proof that any of the recently reported orthohantaviruses, thottimviruses, loanviruses and mobatviruses, harbored by shrews, moles and bats, cause clinically identifiable diseases or syndromes in humans2.

This multi-institutional study represents an extended search for novel bat-borne loanviruses and mobatviruses to better understand their geographic distribution and host diversification. Our data indicate that a newly identified mobatvirus in the Stoliczka’s Asian trident bat (Aselliscus stoliczkanus) is genetically distinct and phylogenetically related to other bat-borne mobatviruses, suggesting that primordial hantaviruses may have been hosted by ancestral bats.

Results

Hantavirus detection

Repeated attempts to detect hantavirus RNA were successful in only one of the 215 lung specimens (Supplemental Table 1), despite using PCR protocols that led to the discovery of other bat-borne hantaviruses. Sequence analysis of the full-length S-, M- and L-genomic segments showed a novel hantavirus, designated Đakrông virus (DKGV), in one of two Stoliczka’s Asian trident bats (Fig. 1A), captured in Đakrông Nature Reserve (16.6091N, 106.8778E) in Quảng Trị Province (Fig. 1B), in August 2013.

Figure 1.

(A) Stoliczka’s Asian trident bat (Aselliscus stoliczkanus). (B) Map of Vietnam, showing Quảng Trị Province (colored red), where a mobatvirus-infected Stoliczka’s Asian trident bat was captured in Đakrông Nature Reserve.

Sequence analysis

The overall genomic organization of DKGV was similar to that of other hantaviruses. A nucleocapsid (N) protein of 427 amino acids was encoded by the 1,746-nucleotide S segment, beginning at position 58, and with a 405-nucleotide 3′-noncoding region (NCR). The hypothetical NSs open reading frame was not found.

A glycoprotein complex (GPC) of 1,127 amino acids was encoded by the 3,622-nucleotide M segment, starting at position 21, and with a 218-nucleotide 3′-NCR. Two potential N-linked glycosylation sites were found in the Gn at amino acid positions 344 and 396 and one in the Gc at position 924. Another possible site was present at amino acid position 133 of the Gn. For comparison, the amino acid positions of N-linked glycosylation sites of other representative hantaviruses are summarized in Table 1. Also, the highly conserved WAASA amino-acid motif was found at amino acid positions 641–645. The full-length Gn/Gc amino acid sequence similarity was highest between DKGV and LAIV (73.0%) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Potential N-linked glycosylation sites in the Gn and Gc glycoproteins of DKGV strain VN2913B72 and representative bat-, rodent-, shrew- and mole-borne hantaviruses.

| Reservoir host | Virus and strain | Gn | Gc | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bat | DKGV VN2913B72 | 133? | 344 | 396 | 924 | |||

| XSV VN1982B4 | 143 | 230 | 345 | 397 | 540 | 925 | ||

| LAIV BT20 | 133 | 344 | 396 | 539, 606 | 924 | |||

| LQUV Ra-25 | 134 | 349? | 441 | 544, 569, 608? | 883, 929 | |||

| BRNV 7/2012/CZE | 96 | 137? | 313, 352? | 444 | 931, 1053 | |||

| QZNV MT1720/1657 | 133 | 300 | 399 | 564 | 928 | |||

| Murid rodent | DOBV/BGDV Greece | 134 | 235 | 347 | 399 | 518, 562 | 928 | |

| HTNV 76-118 | 134 | 235 | 347 | 399 | 609 | 928 | ||

| SANGV SA14 | 134 | 235 | 347 | 399 | 518, 562, 566 | 928 | ||

| SEOV HR80-39 | 132 | 233 | 345 | 397 | 560 | 926 | ||

| SOOV SOO-1 | 134 | 235 | 347 | 399 | 609 | 928 | ||

| Cricetid rodent | PUUV Sotkamo | 142 | 357 | 409 | 898, 937 | |||

| MUJV 11-1 | 136 | 351 | 403 | 892, 931 | ||||

| PHV PH-1 | 139 | 353 | 405 | 527 | 933 | |||

| TULV M5302v | 140 | 355? | 407 | 583 | 935 | |||

| SNV NMH10 | 138 | 351 | 403 | 931 | ||||

| ANDV Chile9717869 | 138 | 350 | 402 | 524 | 930 | |||

| Crocidurine shrew | BOWV VN1512 | 23 | 142 | 355 | 407 | 526, 701 | 936, 1060? | |

| JJUV 10-11 | 142 | 355 | 407 | 936, 1058 | ||||

| MJNV Cl05-11 | 133 | 288 | 387 | 915, 1078 | ||||

| TPMV VRC66412 | 134 | 289 | 388 | 505, 585 | 916 | |||

| Soricine shrew | ASIV Drahany | 138 | 351 | 403 | 566 | 932 | ||

| ARTV MukawaAH301 | 138 | 351 | 403 | 932 | ||||

| CBNV CBN-3 | 138 | 351 | 403 | 932 | ||||

| YKSV Si-210 | 138 | 351 | 403 | 566 | 932 | |||

| Mole | RKPV MSB57412 | 135 | 349 | 401 | 577 | 890, 929 | ||

| OXBV Ng1453 | 138 | 353 | 405 | 524, 617, 623 | 934 | |||

| ASAV N10 | 138 | 352 | 404 | 933 | ||||

| NVAV Te34 | 101 | 133 | 344 | 396 | 539 | 924 | ||

Đakrông virus (DKGV) VN2913B72, Xuân Sơn virus (XSV) VN1982B4, Láibīn virus (LAIV) BT20, Lóngquán virus (LQUV) Ra-25, Brno virus (BRNV) 7/2012/CZE and Quezon virus (QZNV) MT1720/1657 were detected in bats, Dobrava-Belgrade virus (DOBV/BGDV) Greece, Hantaan virus (HTNV) 76-118, Sangassou virus (SANGV) SA14, Seoul virus (SEOV) HR80-39 and Soochong virus (SOOV) SOO-1 in murid rodents, Puumala virus (PUUV) Sotkamo, Muju virus (MUJV) 11-1, Prospect Hill virus (PHV) PH-1, Tula virus (TULV) M5302v, Sin Nombre virus (SNV) NMH10 and Andes virus (ANDV) Chile9717869 in cricetid rodents, Bowé virus (BOWV) VN1512, Jeju virus (JJUV) 10-11, Imjin virus (MJNV) Cl05-11 and Thottapalayam virus (TPMV) VRC66412 in crocidurine shrews, Asikkala virus (ASIV) Drahany, Artybash virus (ARTV) MukawaAH301, Cao Bằng virus (CBNV) CBN-3 and Yákèshí virus (YKSV) Si-210 in soricine shrews and Rockport virus (RKPV) MSB57412, Oxbow virus (OXBV) Ng1453, Asama virus (ASAV) N10 and Nova virus (NVAV) Te34 in moles.

Table 2.

Nucleotide (nt) and amino acid (aa) sequence similarities of the coding regions of the full-length S, M and L segments of DKGV strain VN2913B72 and representative bat-, rodent-, shrew- and mole-borne hantaviruses.

| Reservoir host | Virus and strain | S segment | M segment | L segment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1284 nt | 427 aa | 3384 nt | 1127 aa | 6438 nt | 2145 aa | ||

| Bat | XSV VN1982B4 | 69.9% | 76.5% | 66.9% | 69.3% | 71.3% | 79.4% |

| LAIV BT20 | 70.3% | 76.8% | 69.2% | 73.0% | 73.4% | 81.2% | |

| LQUV Ra-25 | 62.0% | 59.6% | 55.4% | 45.9% | 69.8% | 72.2% | |

| HUPV Pa-1 | 64.0% | 63.1% | — | — | 68.8% | 79.0% | |

| BRNV 7/2012/CZE | 59.7% | 56.7% | 54.6% | 45.6% | 65.6% | 66.1% | |

| QZNV MT1720/1657 | 55.9% | 64.6% | 58.4% | 53.3% | 66.3% | 69.4% | |

| Murid rodent | DOBV/BGDV Greece | 57.2% | 53.2% | 53.7% | 45.9% | 64.6% | 65.4% |

| HTNV 76-118 | 57.0% | 52.5% | 53.7% | 43.6% | 64.6% | 65.3% | |

| SANGV SA14 | 58.0% | 52.2% | 53.8% | 45.6% | 64.3% | 65.0% | |

| SEOV HR80-39 | 56.3% | 51.1% | 53.7% | 43.4% | 64.9% | 65.4% | |

| SOOV SOO-1 | 57.5% | 53.9% | 53.5% | 43.9% | 65.0% | 65.0% | |

| Cricetid rodent | PUUV Sotkamo | 58.0% | 53.2% | 54.2% | 46.0% | 64.8% | 65.1% |

| TULV M5302v | 59.1% | 51.8% | 54.8% | 46.4% | 64.0% | 64.8% | |

| PHV PH-1 | 59.1% | 53.2% | 54.9% | 47.2% | 62.9% | 65.1% | |

| SNV NMH10 | 56.9% | 50.4% | 54.7% | 48.2% | 63.2% | 64.7% | |

| ANDV Chile9717869 | 57.1% | 52.7% | 54.6% | 47.0% | 63.9% | 64.9% | |

| Soricine shrew | CBNV CBN-3 | 57.4% | 53.0% | 54.5% | 44.9% | 64.3% | 65.6% |

| ARRV MSB734418 | 53.3% | 44.0% | — | — | 65.4% | 65.2% | |

| JMSV MSB144475 | 55.3% | 50.2% | 58.1% | 50.6% | 64.2% | 65.9% | |

| ARTV MukawaAH301 | 56.2% | 50.9% | 54.1% | 44.8% | 63.7% | 64.8% | |

| SWSV mp70 | 55.8% | 51.4% | 60.5% | 56.6% | 62.5% | 62.4% | |

| KKMV MSB148794 | 56.0% | 51.2% | 53.5% | 44.0% | 63.9% | 64.9% | |

| QHSV YN05 284 S | 56.7% | 50.5% | 56.6% | 48.3% | 71.4% | 75.2% | |

| YKSV Si-210 | 56.4% | 50.0% | 53.9% | 44.9% | 63.2% | 65.1% | |

| TGNV Tan826 | 55.1% | 47.6% | — | — | 67.5% | 67.2% | |

| AZGV KBM15 | 57.9% | 54.6% | 55.1% | 44.5% | 63.5% | 65.2% | |

| Crocidurine shrew | JJUV SH42 | 56.4% | 49.8% | 54.1% | 45.1% | 63.7% | 63.7% |

| BOWV VN1512 | 56.7% | 49.9% | 55.1% | 43.6% | 62.3% | 63.8% | |

| MJNV Cl05-11 | 53.6% | 45.8% | 51.2% | 40.0% | 63.3% | 64.9% | |

| TPMV VRC66412 | 54.4% | 44.9% | 51.4% | 42.1% | 63.6% | 64.8% | |

| Myosoricine shrew | ULUV FMNH158302 | 55.7% | 49.1% | 54.2% | 42.6% | 63.1% | 64.5% |

| KMJV FMNH174124 | 55.4% | 48.7% | 54.9% | 45.4% | 63.3% | 64.1% | |

| Mole | RKPV MSB57412 | 57.7% | 53.2% | 55.7% | 46.0% | 63.7% | 64.4% |

| OXBV Ng1453 | 56.0% | 51.1% | 53.6% | 44.2% | 63.1% | 64.4% | |

| ASAV N10 | 57.4% | 51.3% | 53.8% | 45.3% | 64.1% | 64.6% | |

| NVAV Te34 | 60.7% | 57.0% | 60.7% | 56.4% | 65.5% | 67.0% | |

Huángpí virus (HUPV) was detected in a bat species, Ash River virus (ARRV), Azagny virus (AZGV), Jemez Springs virus (JMSV), Kenkeme virus (KKMV), Qian Hu Shan virus (QHSV), Seewis virus (SWSV) and Tanganya virus (TGNV) were detected in soricine shrews, and Kilimanjaro virus (KMJV) and Uluguru virus (ULUV) were detected in myosoricine shrews. The other abbreviations of virus names are the same as in Table 1. Three bat-borne hantaviruses from Africa, Makokou virus (MAKV), Magboi virus (MGBV) and Mouyassué virus (MOYV), are not included because only relatively short regions of the L segment were available for analysis. Hyphens indicate no available sequence data.

Analysis of the 6,535-nucleotide L segment, which encoded a 2,145-amino acid RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP), showed the highly conserved A, B, C, D and E motifs, The functional constraints on the RdRP were evidenced by the overall high nucleotide and amino acid sequence similarity of 60% or more in the L segment between DKGV and other hantaviruses (Table 2).

Comparison of the full-length S, M and L segments indicated amino acid sequence similarities ranging from 45.6% (BRNV GPC) to 81.2% (LAIV RdRP) between DKGV and representative bat-borne hantaviruses (Table 2), and showed that DKGV differed at the amino acid level by 30% or more from nearly all rodent- and shrew-borne orthohantaviruses.

Nucleocapsid and glycoprotein secondary structures

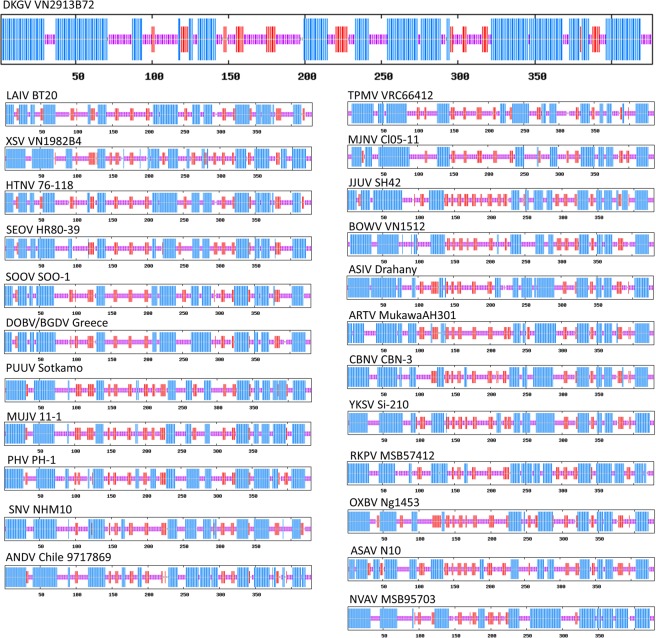

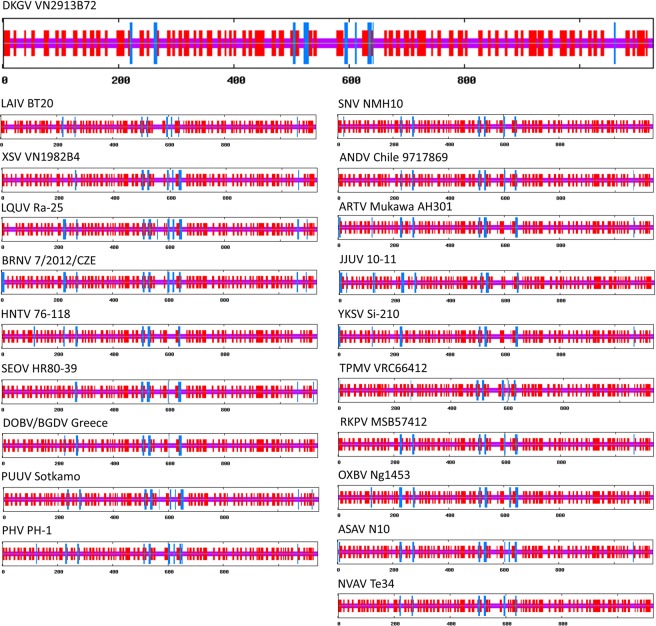

Secondary structure analysis of the N and Gn/Gc proteins indicated similarities and differences between DKGV and representative rodent-, shrew-, mole- and bat-borne hantaviruses (Figs 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Comparison of consensus secondary structures of entire nucleocapsid (N) proteins of DKGV VN2913B72 (large top panel) and other representative hantaviruses (smaller panels), predicted using several methods at the NPS@ structure server14. N protein structures are shown for bat-borne mobatviruses (DKGV VN2913B72, LAIV BT20 and XSV VN1982B4), rodent borne orthohantaviruses (HTNV 76-118, SEOV HR80-39, SOOV SOO-1, DOBV/BGDV Greece, PUUV Sotkamo, MUJV 11-1, PHV PH-1, SNV NMH10 and ANDV Chile9719869) and shrew-borne thottimviruses (TPMV VRC66412 and MJNV Cl05-11), shrew-borne orthohantaviruses (JJUV SH42, BOWV VN1512, ASIV Drahany, ARTV MukawaAH301, CBNV CBN-3 and YKSV Si-210), and mole-borne orthohantaviruses (RKPV MSB57412, OXBV Ng1453 and ASAV N10) and mole-borne mobatvirus (NVAV MSB95703). Blue bars represent α-helices, red bars β-strands, and purple indicate random coil and unclassified structures, respectively. Abbreviations: ANDV, Andes virus; ARTV, Artybash virus; ASAV, Asama virus; ASIV, Asikkala virus; BOWV, Bowé virus; CBNV, Cao Bằng virus; DKGV, Đakrông virus; DOBV/BGDV, Dobrava-Belgrade virus; HTNV, Hantaan virus; JJUV, Jeju virus; LAIV, Láibīn virus; MJNV, Imjin virus; MUJV, Muju virus; NVAV, Nova virus; OXBV, Oxbow virus; PHV, Prospect Hill virus; PUUV, Puumala virus; RKPV, Rockport virus; SEOV, Seoul virus; SNV, Sin Nombre virus; SOOV, Soochong virus; TPMV, Thottapalayam virus; XSV, Xuân Sơn virus; YKSV, Yákèshí virus.

Figure 3.

Comparison of consensus secondary structures of entire envelope glycoproteins (G) of DKGV VN2913B72 (large top panel) and other representative hantaviruses (smaller panels), predicted at the NPS@ structure server44. G protein structures are shown for bat-borne mobatviruses (DKGV VN2913B72, LAIV BT20 and XSV VN1982B4), bat-borne loanviruses (LQUV Ra-25 and BRNV 7/2012/CZE), rodent borne orthohantaviruses (HTNV 76-118, SEOV HR80-39, DOBV/BGDV Greece, PUUV Sotkamo, PHV PH-1, SNV NMH10 and ANDV Chile 9717869), shrew-borne orthohantaviruses (ARTV MukawaAH301, JJUV 10-11 and YKSV Si-210), shrew-borne thottimvirus (TPMV VRC66412), mole-borne orthohantaviruses (RKPV MSB57412, OXBV Ng1453, ASAV N10) and mole-borne mobatvirus (NVAV Te34). Blue bars represent α-helices, red bars β-strands, and purple indicate random coil and unclassified structures, respectively. Abbreviations: BRNV, Brno virus; LQUV, Lóngquán virus; other abbreviations of virus names, as in Fig. 2 legend.

The DKGV N protein secondary structure, comprising 53.16% α-helices, 10.07% β-sheets and 35.13% random coils, resembled that of other hantavirus N proteins. A two-domain, primarily α-helical structure joined by a central β-pleated sheet, was observed. Although the N-terminal domain length was nearly the same, structural changes were evident in the central β-pleated sheet and adjoining C-terminal α-helical domain, according to the phylogenetic relationships of the N proteins.

That is, the N protein comprised two α-helical domains and a central β-pleated sheet (Fig. 2) irrespective of the low amino acid sequence similarity among the orthohantaviruses and thottimviruses. However, the central β-pleated sheet motif and RNA-binding region (amino acid positions 175 to 217) of DKGV differed from that of other hantaviruses, which resembled that of murid rodent-borne orthohantaviruses (Fig. 2).

The DKGV glycoprotein secondary structure, comprising 3.82% α-helices, 40.20% β-sheets and 55.99% random coils, resembled that of other hantavirus glycoproteins (Fig. 3). Also, the four transmembrane helices of the DKGV glycoprotein resembled that of other hantaviruses (Fig. 4), and the putative fusion loop (WGCNPVD) and zinc finger domain (CVVCTRECSCTEELKAHNEHCIQGSCPY CMRDLHPSQHVLTEHYKTC) were observed at residues 760–766 and 542–588, respectively.

Figure 4.

Comparison of consensus predicted transmembrane helices of the envelope glycoprotein complex (GPC) of DKGV VN2913B72 and other representative hantaviruses. GPC structures are shown for mobatviruses hosted by bats (DKGV VN2913B72, LAIV BT20 and XSV VN1982B4) and mole (NVAV Te34), bat-borne loanviruses (LQUV Ra-25 and BRNV 7/2012/CZE), orthohantaviruses harbored by rodents (HTNV 76-118, SEOV HR80-39, DOB/BGDV Greece, PUUV Sotkamo, PHV PH-1, SNV NMH10 and ANDV Chile 9717869), shrews (JJUV 10-11, ARTV Mukawa AH301 and YKSV Si-210) and moles (RKPV MSB57412, OXBV Ng1453, ASAV N10) and shrew-borne thottimvirus (TPMV VRC66412). Red bars represent transmembrane structure, and blue and pink lines indicate inside and outside membrane, respectively.

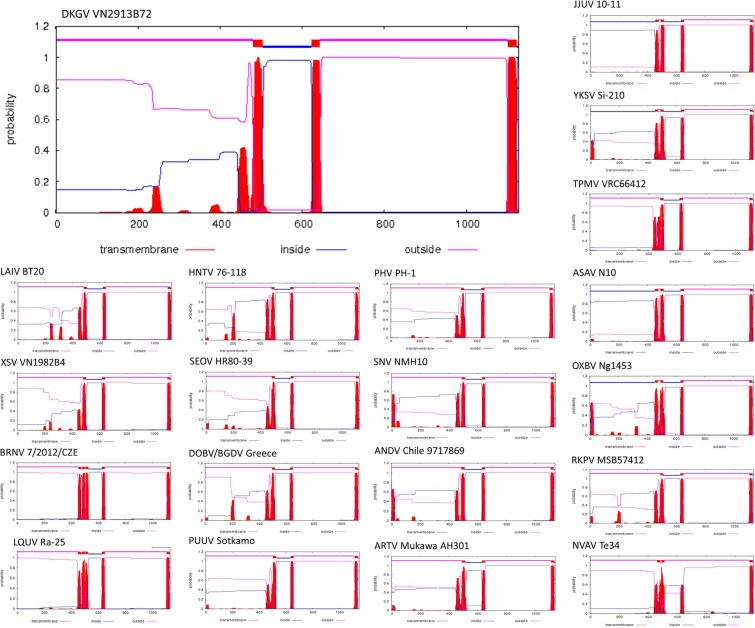

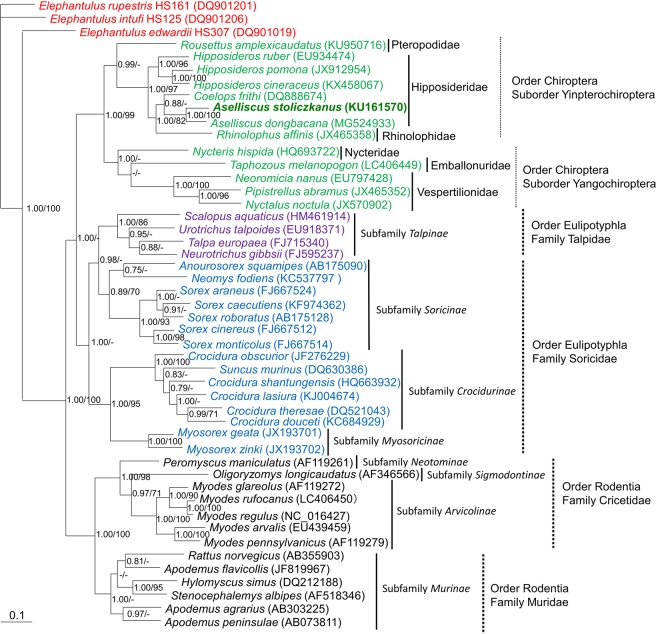

Hantavirus phylogeny

DKGV was distinct from other hantaviruses in phylogenetic trees, based on S-, M- and L-segment sequences using the Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) Bayesian methods (Fig. 5). In all analyses, DKGV and LAIV shared a common ancestry. The basal position of mobatviruses and loanviruses in phylogenetic trees suggested that primordial hantaviruses may have been hosted by ancestral bats (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic trees, based on 1,284-, 3,384- and 6,438-nucleotide regions of the S-, M- and L-genomic segments, respectively, of Đakrông virus (DKGV VN2913B72) (S: MG663534, M: MG663535 and L: MG663536) from Stoliczka’s Asian trident bat, generated by the Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo estimation method, under the GTR + I + Γ model of evolution. The phylogenetic position of DKGV is shown in relation to other chiropteran- and mole-borne mobatviruses, including Láibīn virus (LAIV BT20, S: KM102247; M: KM102248; L: KM102249) from Taphozous melanopogon, Xuân Sơn virus (XSV VN1982B4, S: KC688335; M: KU976427; L: JX912953) from Hipposideros pomona, Quezon virus (QZNV MT1720/1657, S: KU950713; M: KU950714; L: KU950715) from Rousettus amplexicaudatus, and Nova virus (NVAV Te34, S: KR072621; M: KR072622; L: KR072623) from Talpa europaea. Loanviruses including Brno virus (BRNV 7/2012/CZE, S: KX845678; M: KX845679; L: KX845680) from Nyctalus noctula, Lóngquán viruse (LQUV Ra-25, S: JX465415; M: JX465397; L: JX465381) from Rhinolophus affinis, and Huángpí viruse (HUPV Pa-1, S: JX473273; L: JX465369) from Pipistrellus abramus were shown. Also shown are shrew-borne orthohantaviruses including Ash River virus (ARRV MSB734418, S: EF650086; L: EF619961) from Sorex cinereus, Artybash virus (ARTV MukawaAH301, S: KF974360; M: KF974359; L: KF974361) from Sorex caecutiens, Azagny virus (AZGV KBM15, S: JF276226; M: JF276227; L: JF276228) from Crocidura obscurior, Boginia virus (BOGV 2074, M: JX990966; L: JX990965), Bowé virus (BOWV VN1512, S: KC631782; M: KC631783; L: KC631784) from Crocidura douceti, Cao Bằng virus (CBNV CBN-3, S: EF543524; M: EF543526; L: EF543525) from Anourosorex squamipes, Jeju virus (JJUV SH42, S: HQ663933; M: HQ663934; L: HQ663935) from Crocidura shantungensis, Jemez Springs virus (JMSV MSB144475, S: FJ593499; M: FJ593500; L: FJ593501) from Sorex monticolus, Kenkeme virus (KKMV MSB148794, S: GQ306148; M: GQ306149; L: GQ306150) from Sorex roboratus, Qian Hu Shan virus (QHSV YN05-284, S: GU566023; M: GU566022; L: GU566021) from Sorex cylindricauda, Seewis virus (SWSV mp70, S: EF636024; M: EF636025; L: EF636026) from Sorex araneus, Tanganya virus (TGNV Tan826, S: EF050455; L: EF050454) from Crocidura theresea and Yákèshí virus (YKSV Si-210, S: JX465423; M: JX465403; L: JX465389) from Sorex isodon, as well as mole-borne orthohantaviruses including Asama virus (ASAV N10, S: EU929072; M: EU929075; L: EU929078) from Urotrichus talpoides, Oxbow virus (OXBV Ng1453, S: FJ5339166; M: FJ539167; L: FJ593497) from Neurotrichus gibbsii, and Rockport virus (RKPV MSB57412, S: HM015223; M: HM015222; L: HM015221) from Scalopus aquaticus. Shrew-borne thottimviruses include Thottapalayam virus (TPMV VRC66412, S: AY526097; L: EU001330) from Suncus murinus, Imjin virus (MJNV Cl05-11, S: EF641804; M: EF641798; L: EF641806) from Crocidura lasiura, Uluguru virus (ULUV FMNH158302, S: JX193695; M: JX193696; L: JX193697) from Myosorex geata, and Kilimanjaro virus (KMJV FMNH174124, S: JX193698; M: JX193699; L: JX193700) from Myosorex zinki. Other taxa include rodent borne orthohantaviruses, Andes virus (ANDV Chile9717869, S: AF291702; M: AF291703; L: AF291704), Sin Nombre virus (SNV NMH10, S: NC_005216; M: NC_005215; L: NC_005217), Dobrava-Belgrade virus (DOBV/BGDV Greece, S: NC_005233; M: NC_005234; L: NC_005235), Hantaan virus (HTNV 76-118, S: NC_005218; M: NC_005219; L: NC_005222), Hokkaido virus (HOKV Kitahiyama, S: AB675463; M: AB676848; L: AB712372), Muju virus (MUJV 11-1, S: JX028273; M: JX028272; L:JX028271), Prospect Hill virus (PHV PH-1, S: Z49098; M: X55129; L: EF646763), Puumala virus (PUUV Sotkamo, S: NC_005224; M: NC_005223; L: NC_005225), Sangassou virus (SANGV SA14, S: JQ082300; M: JQ082301; L: JQ082302), Seoul virus (SEOV HR80-39, S: NC_005236; M: NC_005237; L: NC_005238), Soochong virus (SOOV SOO-1, S: AY675349; M: AY675353; L: DQ056292), and Tula virus (TULV M5302v, S: NC_005227; M: NC_005228; L: NC_005226). The numbers at each node are Bayesian posterior probabilities (>0.7, left of slash) based on 150,000 trees: two replicate Markov chain Monte Carlo runs, consisting of six chains of 10 million generations each sampled every 100 generations with a burn-in of 25,000 (25%) and bootstrap value (>70%, right of slash) based on 1000 bootstrap replicates. Scale bars indicate nucleotide substitutions per site. Bat-borne hantaviruses are shown in green lettering (DKGV VN2913B72 shown in bold), shrew-borne hantaviruses in blue, mole-borne hantaviruses in purple and rodent borne hantaviruses in black.

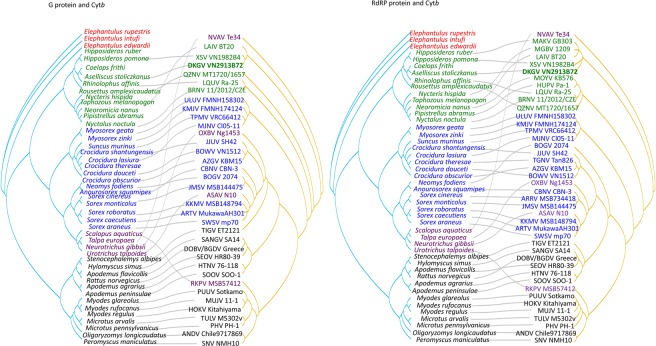

Host phylogeny

Taxonomic classification of the bats was confirmed by PCR amplification and sequencing of the cytochrome b (Cyt b) and cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) genes. Morphologically indistinguishable Aselliscus stoliczkanus and Aselliscus dongbacana were identified by Cyt b (KU161558–KU161575 and MG524933–MG524935) and COI (LC406430–LC406448) gene sequence analysis. Phylogenetic analysis of bats belonging to the suborders Yinpterochiroptera and Yangochiroptera resembled that of DKGV and other bat-borne hantaviruses (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Bayesian phylogenetic tree, based on the 1,140-nucleotide cytochrome b (Cyt b) region of mtDNA of small mammals within the order Eulipotyphla (families Talpidae and Soricidae), order Rodentia (families Muridae and Cricetidae) and order Chiroptera, suborder Yinpterochiroptera (families Pteropodidae, Hipposideridae, Rhinolophidae) and suborder Yangochiroptera (families Nycteridae, Emballonuridae and Vespertilionidae). The tree was rooted using Elephantulus (order Macroscelidea, GenBank accession numbers DQ901019, DQ901206 and DQ901201). Numbers at nodes indicate posterior probability values (>0.7, left of slash) based on 150,000 trees: two replicate Markov chain Monte Carlo runs, consisting of six chains of 10 million generations each sampled every 100 generations with a burn-in of 25,000 (25%) and bootstrap value (>70%, right of slash) based on 1000 bootstrap replicates. Scale bars indicate nucleotide substitutions per site. Letterings for taxa are shown in green for bats, blue for shrews, purple for moles, black for rodents and red for Elephantulus. The GenBank accession number for the Cyt b sequence for Aselliscus stoliczkanus is KU161570.

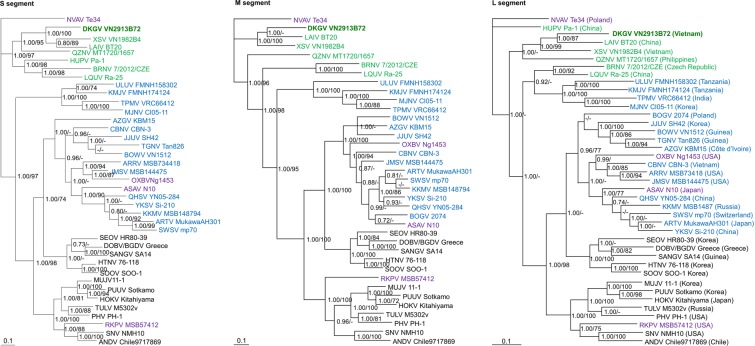

Co-phylogeny of hantavirus and host

Segregation of hantaviruses according to the subfamily of their reservoir hosts was demonstrated by co-phylogeny mapping, using consensus trees based on the Gn/Gc glycoprotein and RdRP protein amino acid sequences (Fig. 7). The phylogenetic positions of DKGV and other mobatviruses (XSV and MAKV) mirrored the phylogenetic relationships of their Hipposideridae hosts. By contrast, the phylogenetic positions of LAIV from Taphozous melanopogon, QZNV from Rousettus amplexicaudatus and LQUV from Rhinolophus affinis were mismatched between virus and host species tanglegram.

Figure 7.

Tanglegram comparing the phylogenies of hantaviruses and their chiroptera, eulipotyphla, and rodent hosts. The host tree on the left was based on cytochrome b (Cyt b) gene sequences, while the hantavirus tree on the right was based on the amino acid sequences of glycoprotein (A) and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (B), respectively. Letterings for taxa are shown in green for bats, blue for shrews, purple for moles, black for rodents and red for Elephantulus in the each left panel. Bat-borne hantaviruses are shown in green lettering (DKGV VN2913B72 shown in bold), shrew-borne hantaviruses in blue, mole-borne hantaviruses in purple and rodent borne hantaviruses in black in the each right panel. The host species and viruses relationship (Cyt b and each segment sequence accession number) were listed in Supplemental Table 3.

Discussion

The Stoliczka’s Asian trident bat, one of three species in the genus Aselliscus, is found throughout Southeast Asia. The Dong Bac’s trident bat (Aselliscus dongbacana), a closely related species, overlaps in body size, distribution, echolocation and habitat32. However, we failed to detect hantavirus RNA in this latter species. As in previous studies, in which only one or two individual bats were found to be infected7,12,13,16, hantavirus RNA was detected in a single Stoliczka’s Asian trident bat. Technical issues (such as primer mismatches, suboptimal cycling conditions, limited tissues and degraded RNA), as well as the restricted transmission and/or immune-mediated clearance of hantavirus infection in bats, are possible contributing factors.

By virtue of the N protein and Gc glycoprotein sequence divergence between DKGV and other hantaviruses, as well as the unique host species, DKGV likely represents a new hantavirus species. A three-dimensional, bi-lobed protein architecture for RNA binding was suggested by the DKGV N protein secondary structure and that of other bat-borne hantaviruses. The fusion loop and zinc finger domain of the glycoprotein suggested that DKGV and other bat-borne loanvirus and mobatviruses have similar mechanisms of protein modification with rodent-borne orthohantaviruses33,34. On the other hand, the envelope GPC is implicated in virus attachment and cell entry. Further insights for receptor and receptor binding sites of hantaviruses harbored by shrews, moles and bats will contribute to a deeper understanding about their host specificities.

Recently, far greater genetic diversity than those in rodents have been detected in orthohantaviruses harbored by shrews and moles of multiple species, belonging to five subfamilies (Soricinae, Crocidurinae, Myosoricinae, Talpinae and Scalopinae) within the order Eulipotyphla, in Europe, Asia, Africa and/or North America. Similarly, hantavirus RNA has been detected in tissues of several bat species belonging to the families Emballonuridae, Nycteridae and Vespertilionidae (suborder Yangochiroptera) and the families Rhinolophidae, Hipposideridae and Pteropodidae (suborder Yinpterochiroptera). It is unclear to what extent spillover or host switching is responsible for the overall low prevalence of hantavirus infection in only 14 bat species to date, and the inability to detect hantavirus RNA in nearly 100 other bat species analyzed to date7–16.

Previously, the overall congruence between gene phylogenies of rodent-borne orthohantaviruses and their hosts led to the conjecture that orthohantaviruses had co-evolved with their reservoir hosts4. However, recent studies, based on co-phylogenetic reconciliation and estimation of evolutionary rates and divergence times, conclude that local host-specific adaptation and preferential host switching account for the phylogenetic similarities between hantaviruses and their mammalian hosts35,36. Although our co-phylogenetic analysis also indicates that bat-borne loanvirus and mobatviruses and their host species have not co-diverged, the availability of whole genome sequences for only four of the 10 bat-borne hantaviruses presented a significant limitation. Thus, future efforts must focus on obtaining full-length genomes of newfound hantaviruses, particularly those harbored by bats in southeast Asia and Africa, to gain additional insights into the phylogeography and evolutionary origins of viruses in the family Hantaviridae.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

Field procedures and protocols for trapping, euthanasia and tissue processing, conforming to the guidelines of the American Society of Mammalogists37,38, were approved by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development in Vietnam. Moreover, permission for this study was obtained from the Vietnam Administration of Forest, belonging to the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, before collecting bat specimens (permission numbers: 1492/TCLN-BTTN; 701/TCLN-BTTN; 389/TCLN-BTTN; 767/TCLN-BTTN). Also, the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, of the National Institute of Infectious Diseases, reviewed and approved the field protocols and experimental procedures (permission number: 112152).

Trapping

Mist nets and harp traps were used to trap bats, during December 2012 to June 2014, in Xuân Lien Nature Reserve (19.8736N, 105.2156E) in Thanh Hóa Province; Vĩnh Cửu Nature Reserve, recently renamed Đồng Nai Culture and Nature Reserve (11.3808N, 107.0622E), in Đồng Nai Province; Khau Ca Nature Reserve (22.8381N, 105.1161E) in Hà Giang Province; Bắc Hướng Hóa Nature Reserve and Đakrông Nature Reserve in Quảng Trị Province; Nà Hang Nature Reserve (22.3532N, 105.4197E) in Tuyên Quang Province; and near Hoàng Liên National Park (22.2833N, 103.9219E) in Lào Cai Province. Live-caught bats were euthanized and lung tissues were preserved in RNAlater® (Qiagen) until testing by RT-PCR.

RNA extraction

Using the MagDEA RNA 100 Kit (Precision System Science, Matsudo, Japan)39, total RNA was extracted from lung tissues of 215 bats, representing 15 genera and 46 species in five families (Hipposideridae, Megadermatidae, Pteropodidae, Rhinolophidae and Vespertilionidae) (Supplemental Table 1). RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA was synthesized using the PrimeScript II 1st strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara bio, Otsu, Japan) and an oligonucleotide primer (OSM55F, 5′–TAGTAGTAGACTCC–3′) designed from conserved 5′–end of the S, M and L segments of hantaviruses39.

RT-PCR and sequencing

Oligonucleotide primers previously used to detect hantaviruses12,13,16,39–43 were employed to amplify S, M and L segments (Supplemental Table 2). First-round PCR was performed in 20-μL reaction mixtures, containing 250 μM dNTP, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1 U of Takara LA Taq polymerase Host Start version (Takara Bio) and 0.25 μM of each primer16. Second-round PCR was performed in 20-μL reaction mixtures, containing 200 μM dNTP, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1 U of AmpliTaq 360 Gold polymerase (Life Technologies, Foster City, CA, USA) and 0.25 μM of each primer16. Initial denaturation at 95 °C for 1 min for first PCR or at 95 °C for 10 min for second PCR were followed by two cycles each of denaturation at 95 °C for 20 s, two-degree step-down annealing from 46 °C to 38 °C for 40 s, and elongation at 68 °C for 1 min, then 30 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 20 s, annealing at 42 °C for 40 s, and elongation at 68 °C for 1 min, in a Veriti thermal cycler (Life Technologies)7,12,13,16,39. PCR products, treated with ExoSAP-IT (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction, were sequenced directly using an ABI 3730xl DNA Analyzer (Life Technologies)16.

Secondary structure analysis

Full-length amino acid sequences were submitted to NPS@ structure server44 to predict secondary structures of the N protein and Gn/Gc glycoproteins36. Glycosylation and transmembrane sites were predicted at the NetNlyc 1.0 and Predictprotein45 and TMHMM version 2.046, respectively. The program COILS47 was used to scan the N protein for expected coiled-coil regions36.

Phylogenetic analysis

Maximum likelihood and Bayesian methods, implemented in RAxML Blackbox webserver48 and MrBayes 3.149, under the best-fit GTR + I + Γ model of evolution and jModelTest version 2.1.650, were used to generate phylogenetic trees13. Two replicate Bayesian Metropolis–Hastings MCMC runs, each consisting of six chains of 10 million generations sampled every 100 generations with a burn-in of 25,000 (25%), resulted in 150,000 trees overall13,16. The S-, M- and L-genomic segments were treated separately in the phylogenetic analyses. Topologies were evaluated by bootstrap analysis of 1,000 iterations, and posterior node probabilities were based on 10 million generations and estimated sample sizes over 100 (implemented in MrBayes)16. With a robust phylogeny of shrew-, mole-, bat- and rodent-borne hantaviruses10, we readdressed the co-evolutionary relationship between hantaviruses and their hosts that formed the basis of our predictive paradigm for hantavirus discovery, by comparing the degree of concordance between reservoir host and hantavirus cladograms in TreeMap 3β124351.

Host identification

Total DNA was extracted from lung tissues, using MagDEA DNA 200 Kit (Precision System Science), and PCR amplification of the 1,140-nucleotide Cyt b gene and 1,545-nucleotide COI gene52,53 was performed with newly designed primer sets: Cy-14724F (5′–GACYARTRRCATGAAAAAYCAYCGTTGT–3′)/Cy-15909R (5′–CYYCWTYIYTGGTTTACAAGACYAG–3′)16 and KOD multi enzyme (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan), and MammMt-5533F (5′–CYCTGTSYTTRRATTTACAGTYYAA–3′)/MammMt-7159R (5′–GRGGTTCRAWWCCTYCCTYTCTT–3′) and Phusion enzyme (New England Biolabs, Ipswitch, MA, USA), respectively. Initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min was followed by two cycles each of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s, two-degree step-down annealing from 60 °C to 50 °C for 30 s, and elongation at 68 °C for 1 min 30 s, then 30 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s, and elongation at 68 °C for 1 min 30 s, in a Veriti thermal cycler13. PCR products were purified by Mobispin S-400 (Molecular Biotechnology, Lotzzestrasse, Germany) and were sequenced directly.

GenBank accession numbers

MG663534, MG663535 and MG663536 for Đakrông virus; MG524933–MG524935 and LC406452–LC406456 for cytochrome b and LC406430–LC406448 for cytochrome c oxidase I of Aselliscus stoliczkanus and Aselliscus dongbacana.

Supplementary information

Đakrông virus, a novel mobatvirus (Hantaviridae) harbored by the Stoliczka’s Asian trident bat (Aselliscus stoliczkanus) in Vietnam

Acknowledgements

We thank Hitoshi Suzuki, Shinichiro Kawada, Satoshi D. Ohdachi and Kimiyuki Tsuchiya for supporting field investigations and for valuable advice. This work was supported in part by a grant-in-aid Research on Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases, Health Labour Sciences Research Grant in Japan (H25-Shinko-Ippan-008), grants-in-aid on Research Program on Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases, Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) JP15fk0108005, JP16fk0108117, JP17fk0108217, JP18fk0108017 and JP19fk0108097, grant-in aid from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science 24405045 (Scientific Research grant B), grant-in-aid on NAFOSTED (106-NN.05-2016.14), and VAST-JSPS (QTJP01.02/18-20).

Author Contributions

S.A., S.H.G., R.Y. and K.O. conceived and designed the experiments; S.A., N.T.S., V.T.T., D.F. and H.T.T. conducted the trapping and field collections; S.A., K.A. and F.K. performed the experiments; S.A., G.K. and R.Y. analyzed the data; N.T.S., V.T.T. and H.T.T analyzed the host morphology; S.A., Y.Y., K.T., S.M., R.Y. and K.O. contributed reagents, materials and analysis tools. S.A., N.T.S., V.T.T., S.M. and R.Y. prepared the figures and manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

1/15/2020

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-46697-5.

References

- 1.Yanagihara R, Gu SH, Arai S, Kang HJ, Song J-W. Hantaviruses: rediscovery and new beginnings. Virus Res. 2014;187:6–14. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2013.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yanagihara, R., Gu, S. H. & Song, J.-W. Expanded host diversity and global distribution of hantaviruses: implications for identifying and investigating previously unrecognized hantaviral diseases In Global Virology I – Identifying and Investigating Viral Diseases (eds Shapshak, P., Sinnott, J. T., Somboonwit, C. & Kuhn, J. H.) 161–198 (Springer New York, 2015).

- 3.Mouchaty SK, Gullberg A, Janke A, Arnason U. The phylogenetic position of the Talpidae within eutheria based on analysis of complete mitochondrial sequences. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17:60–67. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennett SN, Gu SH, Kang HJ, Arai S, Yanagihara R. Reconstructing the evolutionary origins and phylogeography of hantaviruses. Trends Microbiol. 2014;22:473–482. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams MJ, et al. Changes to taxonomy and the International Code of Virus Classification and Nomenclature ratified by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Arch Virol. 2017;162:2505–2538. doi: 10.1007/s00705-017-3358-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maes Piet, Adkins Scott, Alkhovsky Sergey V., Avšič-Županc Tatjana, Ballinger Matthew J., Bente Dennis A., Beer Martin, Bergeron Éric, Blair Carol D., Briese Thomas, Buchmeier Michael J., Burt Felicity J., Calisher Charles H., Charrel Rémi N., Choi Il Ryong, Clegg J. Christopher S., de la Torre Juan Carlos, de Lamballerie Xavier, DeRisi Joseph L., Digiaro Michele, Drebot Mike, Ebihara Hideki, Elbeaino Toufic, Ergünay Koray, Fulhorst Charles F., Garrison Aura R., Gāo George Fú, Gonzalez Jean-Paul J., Groschup Martin H., Günther Stephan, Haenni Anne-Lise, Hall Roy A., Hewson Roger, Hughes Holly R., Jain Rakesh K., Jonson Miranda Gilda, Junglen Sandra, Klempa Boris, Klingström Jonas, Kormelink Richard, Lambert Amy J., Langevin Stanley A., Lukashevich Igor S., Marklewitz Marco, Martelli Giovanni P., Mielke-Ehret Nicole, Mirazimi Ali, Mühlbach Hans-Peter, Naidu Rayapati, Nunes Márcio Roberto Teixeira, Palacios Gustavo, Papa Anna, Pawęska Janusz T., Peters Clarence J., Plyusnin Alexander, Radoshitzky Sheli R., Resende Renato O., Romanowski Víctor, Sall Amadou Alpha, Salvato Maria S., Sasaya Takahide, Schmaljohn Connie, Shí Xiǎohóng, Shirako Yukio, Simmonds Peter, Sironi Manuela, Song Jin-Won, Spengler Jessica R., Stenglein Mark D., Tesh Robert B., Turina Massimo, Wèi Tàiyún, Whitfield Anna E., Yeh Shyi-Dong, Zerbini F. Murilo, Zhang Yong-Zhen, Zhou Xueping, Kuhn Jens H. Taxonomy of the order Bunyavirales: second update 2018. Archives of Virology. 2019;164(3):927–941. doi: 10.1007/s00705-018-04127-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sumibcay L, et al. Divergent lineage of a novel hantavirus in the banana pipistrelle (Neoromicia nanus) in Cote d’Ivoire. Virol J. 2012;9:34. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-9-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Těšíková J, Bryjová A, Bryja J, Lavrenchenko LA, Goüy de Bellocq J. Hantavirus strains in East Africa related to Western African hantaviruses. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2017;17:278–280. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2016.2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiss S, et al. Hantavirus in bat, Sierra Leone. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:159–161. doi: 10.3201/eid1801.111026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo WP, et al. Phylogeny and origins of hantaviruses harbored by bats, insectivores, and rodents. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003159. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Straková P, et al. Novel hantavirus identified in European bat species Nyctalus noctula. Infect Genet Evol. 2017;48:127–130. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2016.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arai S, et al. Novel bat-borne hantavirus, Vietnam. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:1159–1161. doi: 10.3201/eid1907.121549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gu SH, et al. Molecular phylogeny of hantaviruses harbored by insectivorous bats in Cote d’Ivoire and Vietnam. Viruses. 2014;6:1897–1910. doi: 10.3390/v6051897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu L, et al. Novel hantavirus identified in black-bearded tomb bats, China. Infect Genet Evol. 2015;31:158–160. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2015.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Witkowski PT, et al. Phylogenetic analysis of a newfound bat-borne hantavirus supports a laurasiatherian host association for ancestral mammalian hantaviruses. Infect Genet Evol. 2016;41:113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2016.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arai S, et al. Molecular phylogeny of a genetically divergent hantavirus harbored by the Geoffroy’s rousette (Rousettus amplexicaudatus), a frugivorous bat species in the Philippines. Infect Genet Evol. 2016;45:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2016.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee HW, Lee P-W, Johnson KM. Isolation of the etiologic agent of Korean hemorrhagic fever. J Infect Dis. 1978;137:298–308. doi: 10.1093/infdis/137.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee HW, Lee P-W, Lähdevirta J, Brummer-Korventkontio M. Aetiological relation between Korean haemorrhagic fever and nephropathia epidemica. Lancet. 1979;1:186–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brummer-Korvenkontio M, et al. Nephropathia epidemica: detection of antigen in bank voles and serologic diagnosis of human infection. J Infect Dis. 1980;141:131–134. doi: 10.1093/infdis/141.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nichol ST, et al. Genetic identification of a hantavirus associated with an outbreak of acute respiratory illness. Science. 1993;262:914–917. doi: 10.1126/science.8235615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duchin JS, et al. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome: a clinical description of 17 patients with a newly recognized disease. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:949–955. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199404073301401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yanagihara, R. & Gajdusek, D. C. Hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome: a historical perspective and review of recent advances in CRC Handbook of Viral and Rickettsial Hemorrhagic Fevers (ed. Gear, J. H. S.) 155–181 (CRC Press, Inc., Boca Raton, Florida, 1988).

- 23.Vaheri A, et al. Hantavirus infections in Europe and their impact on public health. Rev Med Virol. 2013;23:35–49. doi: 10.1002/rmv.1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jonsson CB, Figueiredo LTM, Vapalahti O. A global perspective on hantavirus ecology, epidemiology, and disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:412–441. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00062-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacNeil A, Ksiazek TG, Rollin PE. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, United States, 1993-2009. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1195–1201. doi: 10.3201/eid1707.101306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsai TF. Hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome: mode of transmission to humans. Lab Anim Sci. 1987;37:428–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yanagihara R. Hantavirus infection in the United States: epizootiology and epidemiology. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12:449–457. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.3.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Padula PJ, et al. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome outbreak in Argentina: molecular evidence for person-to-person transmission of Andes virus. Virology. 1998;241:323–330. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toro J, et al. An outbreak of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, Chile, 1997. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998;4:687–694. doi: 10.3201/eid0404.980425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martinez-Valdebenito C, et al. Person-to-person household and nosocomial transmission of andes hantavirus, Southern Chile, 2011. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1629–1636. doi: 10.3201/eid2010.140353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heinemann P, et al. Human infections by non-rodent-associated hantaviruses in Africa. J Infect Dis. 2016;214:1507–1511. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tu VT, et al. Description of a new species of the genus Aselliscus (Chiroptera, Hipposideridae) from Vietnam. Acta Chiropterologica. 2015;17:233–254. doi: 10.3161/15081109ACC2015.17.2.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Estrada DF, Boudreaux DM, Zhong D, St Jeor SC, De Guzman RN. The hantavirus glycoprotein G1 tail contains dual CCHC-type classical zinc fingers. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:8654–8660. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808081200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cifuentes-Munoz N, Salazar-Quiroz N, Tischler ND. Hantavirus Gn and Gc envelope glycoproteins: key structural units for virus cell entry and virus assembly. Viruses. 2014;6:1801–1822. doi: 10.3390/v6041801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kang HJ, et al. Host switch during evolution of a genetically distinct hantavirus in the American shrew mole (Neurotrichus gibbsii) Virology. 2009;388:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramsden C, Holmes EC, Charleston MA. Hantavirus evolution in relation to its rodent and insectivore hosts: no evidence for codivergence. Mol Biol Evol. 2009;26:143–153. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kirkland JGL. Guidelines for the Capture, Handling, and Care of Mammals as Approved by the American Society of Mammalogists. J Mammal. 1998;79:1416–1431. doi: 10.2307/1383033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sikes RS, Animal C. & Use Committee of the American Society of, M. 2016 Guidelines of the American Society of Mammalogists for the use of wild mammals in research and education. J Mammal. 2016;97:663–688. doi: 10.1093/jmammal/gyw078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arai S, et al. Genetic diversity of Artybash virus in the Laxmann’s shrew (Sorex caecutiens) Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2016;16:468–475. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2015.1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klempa B, et al. Hantavirus in African wood mouse, Guinea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:838–840. doi: 10.3201/eid1205.051487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klempa B, et al. Novel hantavirus sequences in shrew, Guinea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:520–522. doi: 10.3201/eid1303.061198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song JW, et al. Newfound hantavirus in Chinese mole shrew, Vietnam. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1784–1787. doi: 10.3201/eid1311.070492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Song JW, et al. Seewis virus, a genetically distinct hantavirus in the Eurasian common shrew (Sorex araneus) Virol J. 2007;4:114. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-4-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Combet C, Blanchet C, Geourjon C, Deleage G. NPS@: network protein sequence analysis. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:147–150. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(99)01540-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gavel Y, von Heijne G. Sequence differences between glycosylated and non-glycosylated Asn-X-Thr/Ser acceptor sites: implications for protein engineering. Protein Eng. 1990;3:433–442. doi: 10.1093/protein/3.5.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lupas A, Van Dyke M, Stock J. Predicting coiled coils from protein sequences. Science. 1991;252:1162–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.252.5009.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stamatakis A, Hoover P, Rougemont J. A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML Web servers. Syst Biol. 2008;57:758–771. doi: 10.1080/10635150802429642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D. jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat Methods. 2012;9:772. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Charleston MA, Robertson DL. Preferential host switching by primate lentiviruses can account for phylogenetic similarity with the primate phylogeny. Syst Biol. 2002;51:528–535. doi: 10.1080/10635150290069940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tu VT, et al. Comparative phylogeography of bamboo bats of the genus Tylonycteris (Chiroptera, Vespertilionidae) in Southeast Asia. Eur. J Taxon. 2017;274:1–38. doi: 10.5852/ejt.2017.274. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tu VT, Hassanin A, Furey NM, Son NT, Csorba G. Four species in one: multigene analyses reveal phylogenetic patterns within Hardwicke’s woolly bat, Kerivoula hardwickii-complex (Chiroptera, Vespertilionidae) in Asia. Hystrix It J Mamm. 2018 doi: 10.4404/hystrix-00017-2017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Đakrông virus, a novel mobatvirus (Hantaviridae) harbored by the Stoliczka’s Asian trident bat (Aselliscus stoliczkanus) in Vietnam