Abstract

This study aimed to explore potential biocontrol mechanisms involved in the interference of antagonistic bacteria with fungal pathogenicity in planta. To do this, we conducted a comparative transcriptomic analysis of the “take-all” pathogenic fungus Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici (Ggt) by examining Ggt-infected wheat roots in the presence or absence of the biocontrol agent Bacillus velezensis CC09 (Bv) compared with Ggt grown on potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates. A total of 4,134 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified in Ggt-infected wheat roots, while 2,011 DEGs were detected in Bv+Ggt-infected roots, relative to the Ggt grown on PDA plates. Moreover, 31 DEGs were identified between wheat roots, respectively infected with Ggt and Bv+Ggt, consisting of 29 downregulated genes coding for potential Ggt pathogenicity factors – e.g., para-nitrobenzyl esterase, cutinase 1 and catalase-3, and two upregulated genes coding for tyrosinase and a hypothetical protein in the Bv+Ggt-infected roots when compared with the Ggt-infected roots. In particular, the expression of one gene, encoding the ABA3 involved in the production of Ggt’s hormone abscisic acid, was 4.11-fold lower in Ggt-infected roots with Bv than without Bv. This is the first experimental study to analyze the activity of Ggt transcriptomes in wheat roots exposed or not to a biocontrol bacterium. Our results therefore suggest the presence of Bv directly and/or indirectly impairs the pathogenicity of Ggt in wheat roots through complex regulatory mechanisms, such as hyphopodia formation, cell wall hydrolase, and expression of a papain inhibitor, among others, all which merit further investigation.

Keywords: endophytic bacteria, pathogenic fungi, phytopathology, RNA sequencing, wheat disease

Introduction

“Take-all” is one of the most severe soil-borne diseases of wheat plants worldwide, caused by the necrotrophic fungus Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici (Bithell et al., 2016). This pathogen infects healthy wheat roots via infectious hyphae that penetrate the cortical cells of the root and progress upward into the stem base. Because this process invariably disrupts water flow, it eventually results in the premature death of infected plants. However, since the well-known virulence mechanism of Ggt might contribute to improved control of this fungal pathogen, considerable research effort has sought to better understand the mechanisms underlying Ggt pathogenicity (Dori et al., 1995; Yu et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2012). Consequently, many genes that contribute to Ggt pathogenicity have been identified, such as cellulase, endo-β-1,4-xylanase, pectinase, xylanase, β-1,3-exoglucanase, glucosidase, aspartic protease, and β-1,3-glucanase of cell wall degrading enzymes (CWDEs) (Yang et al., 2015). Based on their comparative transcriptome analysis of Ggt in axenic culture and Ggt-infected wheat, Yang et al. (2015) recently pointed out that many genes related to signaling, penetration, fungal nutrition, and host colonization are highly expressed during Ggt pathogenesis in wheat roots. Nevertheless, because of the complexity of the interaction between Ggt and its host plants, the pathogenesis of Ggt in wheat roots remains unclear. Additionally, control of the disease is hindered by a lack of resistant varieties and environmentally friendly fungicides.

Several studies have shown that beneficial bacteria, such as Bacillus subtilis (Liu et al., 2009, 2011; Durán et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2018), Bacillus velezensis (Wu et al., 2012; Luo et al., 2013; Kang et al., 2018), and Pseudomonas fluorescens (Daval et al., 2011; Kwak and Weller, 2013; Lagzian et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2014, 2017), could be used as effective and eco-friendly biocontrol agents to protect wheat from take-all disease. Among them, B. velezensis is a newly reported species that may be used to control take-all and other fungal diseases, such as spot blotch and powdery mildew (Cai et al., 2017; Kang et al., 2018). More specifically, B. velezensis CC09 (Bv) is an endophytic biocontrol bacterium, originally isolated from healthy Cinnamomum camphora leaves, that has broad antifungal spectra against many phytopathogens (Cai et al., 2016). It possesses several key biocontrol traits, namely, the production of strong antifungal metabolites (e.g., iturins and fengycins), promotion of plant growth, and induction of plant resistance (Cai et al., 2017; Kang et al., 2018). Recently, we found that this strain can cause the swelling, deformation, and cell content release of Ggt mycelia in vitro, inhibiting Ggt mycelia density and spread in wheat (Kang et al., 2018). Moreover, we also found that Bv could colonize and migrate in plants, leading to a 66.67% disease-control efficacy of take-all and 21.64% of spot blotch, with a single treatment inoculated on roots (Kang et al., 2018). These attributes make Bv a promising biocontrol agent for the long-term and effective protection of wheat from soil-borne and leaf diseases.

Yet, despite these established biocontrol features of Bv, limited information is available concerning its direct and indirect effects upon Ggt’s fungal pathogenicity in planta. For example, how Ggt responds to the presence of Bv in Ggt-infected plants remains unknown. In this study, we performed an RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) analysis of Ggt in wheat roots with and without Bv. Since the Ggt transcriptome in axenic culture and Ggt-infected wheat roots differed markedly and varied during the infection process (Yang et al., 2015), the transcriptome of Ggt grown on potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates was also determined to serve as the control (CK). Through a comparative analysis of Ggt transcriptomes under three different conditions (e.g., grown on PDA, within wheat roots in the presence or absence of Bv), we sought to reveal the possible pathogenicity gene(s) of Ggt and its regulation by Bv in planta during the early infection of wheat roots.

Materials and Methods

The Wheat, Bacterium, and Fungus

The winter wheat (Triticum aestivum “Sumai 188”) used in this study was purchased from the Jiangsu Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Nanjing, China. The endophytic bacterium Bv was isolated from C. camphora leaf tissue (Cai et al., 2016) and deposited in the China Center of Industrial Culture Collection (No. CICC24093). The genome sequence of Bv was deposited in the GenBank database under accession number CP015443. Bv was cultured in LB medium at 37°C and 200 rpm for 12 h (exponential growth phase), and then harvested by centrifugation at 8,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C, and finally resuspended in distilled water to a final concentration of 1.0 × 108 CFU/mL (Kang et al., 2018). The take-all causative pathogen, Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici strain Ggt-C2 (Ggt), was deposited in Agricultural Culture Collection of China (No. ACCC 30310); it was a gift from Prof. Jian Heng (Department of Plant Pathology, Chinese Agricultural University, Beijing, China). The pathogenicity of Ggt was evaluated on T. aestivum Sumai 188 in our prior study (Kang et al., 2018). The periphery of 10-day-old colonies of Ggt on PDA plates at 25°C was used for inoculations.

Root Inoculation and Sampling

Seeds of winter wheat were surface disinfected and germinated, as described by Kang et al. (2018). Germinated wheat seeds were cultured on a sterilized 72-cell seedling tray containing 120 mL of 1/2 MS (Duchefa Biochemie, Haarlem, Netherlands, catalog number M022250) and incubated at 25°C under a 14-h light/10-h dark cycle for 7 days. The roots of 15 7-day-old seedlings were inoculated with 30 mL of Bv inoculum (1.0 × 108 CFU/mL). An equal amount of sterile distilled water was used to treat the roots, as a negative control. Five days after inoculation with Bv, the seedlings were gently removed from the tray, their roots were rinsed with sterile water, and then they were placed on water agar plates. Half of the seedling roots, whether inoculated with Bv or not, were fully covered by the fresh periphery of the 10-day-old colonies of Ggt and maintained for 3 days in a plant growth chamber at 25°C, under 50% relative humidity and a 14-h light/10-h dark cycle (light intensity of 200 μmol m–2 s–1). At this time, the mycelium had invaded the root cortex of wheat roots, but these lacked obvious symptoms (Kang et al., 2018). Approximately 15 seedling roots were pooled for each biological replicate of the Ggt or Bv+Ggt treatment; they were immediately flash frozen, and stored in liquid nitrogen until later usage, while 0.1 g of the periphery of the 10-day-old Ggt colony was remove from PDA plates and maintained in liquid nitrogen as well. Assays were repeated for three independent experiments. Thus, the total number of seedlings used was 45 (three replicates) per treatment or control group.

RNA-Seq and Data Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from Ggt- and Bv+Ggt-infected roots of wheat seedlings using an RNAiso Plus kit (TaKaRa, Otsu, Japan). The same method was used to extract total RNA from Ggt (periphery of 10-day-old colony) grown on PDA plates. The purity and integrity of the total RNA were determined using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer RNA chip (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, United States). The mRNA was purified from 3 μg of total RNA per sample using oligo(dT) magnetic beads and then cleaved into short fragments using divalent cations under elevated temperature. The short fragments were used for first-strand cDNA synthesis by using random primers and reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, United States), followed by a second-strand cDNA synthesis, performed using DNA polymerase I and RNaseH. After the end repair process and ligation of adaptors, these second-strand cDNA products were purified and amplified via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to create the final cDNA library.

The cDNA libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeqTM 4000 platform by following the default Illumina Stranded RNA protocol (Personalbio, Shanghai, China). Clean reads were obtained by removing adapter sequences, any reads with more than 10% N, along with low-quality sequences (e.g., more than 50% of each read that had a Phred score Q ≤ 5). The Q20, Q30, and GC contents of the cleaned data were calculated (Yang et al., 2015). Each sample resulted in approximately 17 million 150-bp clean reads (sequencing data >2 gigabases per sample) for Ggt on PDA plates and 180 million 150-bp clean reads (sequencing data >25 gigabases per sample) for Ggt- or Bv+Ggt-infected root sample. Filtered clean reads were aligned to the reference Ggt genome in the genome website1 using SOAPaligner/SOAP2 (Li et al., 2009). All RNA-Seq data generated for this study were deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive under BioProject IDs PRJNA485739 and PRJNA496308. Reads per kilobase per million (RPKM) were used to normalize the levels of gene expression for each replicate. To evaluate the reproducibility of RNA-Seq, a hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) was done using the command “heatmap3::heatmap3” in the R (v3.5.3) package “gplots” (Warnes et al., 2015) with the hclust command (R Core Team, 2009). The “DESeq” package (1.10.1) of R was used to analyze differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in Ggt among the three conditions under the criteria of P values < 0.05 and an absolute log2 ratio ≥1 (Anders and Huber, 2012).

Functional Analysis of RNA-Seq Data

Two enrichment analyses of DEGs between samples were performed, topGO, and KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes), by respectively, using the AgriGO analytical tools2 and the KEGG website3 (Alexa and Rahnenfuhrer, 2010; Yang et al., 2015). GO terms and KEGG pathways were considered significantly enriched by DEGs if the P values were < 0.05. All Venn diagrams were produced using Venny Tools4. Pathogenesis-related genes were identified through a BLAST search of the pathogen–host interaction (PHI) database (identity >25, E-value: 1e-10) (Jing et al., 2017).

The STEM (short time-series expression miner) software5 (Ernst et al., 2005) was used to identify the significantly enriched expression profiles (P values < 0.05) in Ggt on PDA plates and in Ggt- and Bv+Ggt-infected wheat roots. The log2-transformed RPKM values of Ggt on plates and in Ggt-infected roots in the absence or presence of Bv were used as the input data set. The software parameters for this STEM analysis were as follows: maximum number of model profiles = 8; maximum unit change in model profiles between treatments = 2; and calculated method of significance level = permutation test corrected by Bonferroni correction.

Validation of RNA-Seq Results via Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR

The expression levels of six pathogenicity DEGs were determined by using quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) to confirm the prior results of the RNA-Seq analysis. Total RNA from Ggt- and Bv+Ggt-infected wheat roots was each reverse transcribed into cDNA with the PrimeScriptTM 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Takara, Dalian, China, Code No. 6110A) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The qRT-PCR was carried out by an Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States) using a SYBR® Advantage® qPCR premix (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan). Each qRT-PCR was performed with a 20-μL volume containing 2 μL of cDNA, 0.4 μL of each primer (10 μM), 10 μL of 2 × SYBR Green PCR Master Mix, and 7.2 μL of nuclease-free water. The amplification went as follows: 95°C for 30 s, 40 cycles at 95°C for 5 s, and 60°C for 5 s. The qRT-PCR primers used for the DEGs’ validation are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Three housekeeping genes – encoding actin, tubulin beta, and elongation factor2-1 – served as internal reference for qRT-PCR. Each reaction was performed in triplicate independent experiments for the reference and selected genes. Gene expression was evaluated by applying the 2–ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

Statistical Analyses

The qRT-PCR amplification data are expressed here as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of at least three independent biological experiments. PRISM software v7.0 (Graph-Pad Software, San Diego, CA, United States) was used to perform one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) that compared the three conditions. Tukey’s multiple pairwise comparison test was applied to the mean relative expression levels of selected pathogenicity genes (first normalized by the three internal reference genes). A P-value of less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

Results

General Analyses of RNA-Seq Data

After removing the low-quality reads and adaptors, a total of 67,293,916, 553,791,342, and 553,453,160 clean reads were generated from the mRNA of Ggt on PDA and Ggt in wheat roots with and without Bv, which accounted for 91.6%, 83.2%, and 84.9% of raw reads, respectively (Supplementary Table S2). The quality of each library was similar, ranging from 97.02% to 98.63% of the raw reads with quality values of Q ≥ 20, and likewise from 92.16% to 96.03% of the raw reads with quality values of Q ≥ 30. Their average GC contents were 59.52%, 56.67%, and 57.77% for Ggt on PDA and Ggt in wheat roots with and without Bv, respectively. Together, these results confirmed the high quality of our sequencing data and their robust suitability for further analysis.

Identification of DEGs

A total of 9,588, 9,389, and 8,826 expressed genes were, respectively detected in Ggt on PDA and in wheat roots in the absence and presence of Bv, which corresponded to 64.19%, 62.86%, and 59.09% of all genes (14,936) in the Ggt genome. We found 8,395 genes expressed in Ggt (RPKM > 1) under all three conditions. Based on the respective RPKM values of these 8,395 genes, HCA showed that the three biological replicates from each treatment clustered into an independent branch (Supplementary Figure S1), thus indicating RNA-Seq data were reliable, being highly repeatable between biological replicates. When compared with Ggt grown on PDA, 4,134 DEGs (2,142 upregulated, 1,992 downregulated) and 2,011 DEGs (957 upregulated, 1,054 downregulated) were identified in Ggt in wheat roots in the absence and presence of Bv, respectively (Supplementary Figure S2A). The total numbers of upregulated and downregulated genes in the Ggt-treated samples were, respectively, 2.24- and 1.89-fold higher than those observed in the Bv+Ggt-treated group. As the Venn diagram shows, 1,251 and 66 upregulated DEGs, as well as 1,000 and 62 downregulated DEGs, were uniquely found in Ggt in wheat roots without and with Bv, respectively (Supplementary Figure S2B). However, overall rates of gene expression were similar between these two treatments (Supplementary Figure S2C).

In addition, a total of 31 DEGs were detected between the Ggt- and Bv+Ggt-infected wheat root libraries, with two upregulated genes (GGTG_06400 and GGTG_05929) and 29 downregulated genes in Bv+Ggt-infected roots relative to Ggt-infected roots (Table 1). Among the downregulated DEGs in Bv+Ggt-infected wheat roots, 13 genes (41.94%) were associated with secreted proteins, three genes (9.68%) encoded pathogenicity proteins (para-nitrobenzyl esterase, cutinase 1, and catalase-3), two genes were linked to cell wall lysis enzymes (esterase and cutinase), and one gene encoded peroxidases (catalase-3). In particular, the expression of ABA3 protein-encoding gene involved in the biosynthesis of abscisic acid was downregulated 4.11 times in Bv+Ggt-infected wheat roots compared with Ggt-infected wheat roots; this suggested that Bv might inhibit mycelial infection by regulating Ggt-derived abscisic acid. All these results indicated that the presence of Bv in wheat root directly or indirectly reduced the expression of pathogenicity genes.

TABLE 1.

The expression profile of Ggt DEGs that were only affected by Bv in planta based on the analysis comparing Bv+Ggt and Ggt transcriptomic data.

| Gene ID | Ggt | Bv+Ggt | Bv+Ggt_vs_Ggt | Protein name | Secreted protein | PHI |

| GGTG_03282 | 5.29 | 2.90 | −2.33 | Para-nitrobenzyl esterase | Yes | PHI:2032 |

| GGTG_10566 | 11.38 | −4.80 | Cutinase 1 | Yes | PHI:2383 | |

| GGTG_10011 | −2.38 | Catalase-3 | Yes | PHI:1034 | ||

| GGTG_08754 | 4.39 | 1.79 | −2.54 | Endothiapepsin | Yes | |

| GGTG_06400 | 2.97 | 1.96 | Tyrosinase | Yes | ||

| GGTG_12447 | 3.94 | −2.56 | Arylsulfatase-like protein | Yes | ||

| GGTG_06631 | 9.83 | −3.93 | Cell wall protein | Yes | ||

| GGTG_05929 | −2.09 | 1.42 | Hypothetical protein | Yes | ||

| GGTG_13651 | 10.54 | 8.25 | −2.23 | Hypothetical protein | Yes | |

| GGTG_07328 | 8.98 | 6.96 | −1.96 | Hypothetical protein | Yes | |

| GGTG_00233 | 12.22 | 9.88 | −2.28 | Diaminopimelate decarboxylase | Yes | |

| GGTG_08345 | 10.69 | 8.20 | −2.44 | Hypothetical protein | Yes | |

| GGTG_08028 | 10.15 | −4.05 | Cell wall protein | Yes | ||

| GGTG_07717 | 5.68 | 3.97 | −1.65 | Copper-transporting ATPase 1 | ||

| GGTG_08722 | 4.03 | −2.50 | Sodium/phosphate symporter | |||

| GGTG_07931 | 3.18 | 1.65 | −1.47 | Putative nucleosome assembly protein | ||

| GGTG_12291 | 2.03 | −1.53 | 2-hydroxyacid dehydrogenase | |||

| GGTG_05152 | 3.04 | −2.48 | Arsenical-resistance protein | |||

| GGTG_08620 | 3.95 | 2.36 | −1.52 | L-ornithine 5-monooxygenase | ||

| GGTG_05151 | 3.94 | −2.20 | NADPH-dependent FMN reductase ArsH | |||

| GGTG_02030 | 3.32 | −2.13 | Aldehyde reductase ii | |||

| GGTG_02188 | −1.62 | −1.94 | Glycosyl Hydrolase-glycosidase superfamily | |||

| GGTG_03806 | 4.28 | −2.32 | NAD(P)-binding protein | |||

| GGTG_09078 | 4.86 | −4.59 | ubiE/COQ5 methyltransferase | |||

| GGTG_10994 | 4.11 | −2.25 | Glycosyl transferase, family 25 | |||

| GGTG_11842 | 10.71 | 7.84 | −2.82 | Putative cytochrome P450 monooxygenase | ||

| GGTG_03493 | 1.95 | −2.85 | Integral membrane protein | |||

| GGTG_11826 | 9.68 | 5.97 | −3.66 | Cyclohexanone –monooxygenase | ||

| GGTG_11845 | 7.77 | −4.11 | Putative ABA3 protein | |||

| GGTG_03814 | 5.90 | −2.92 | AhpD-like protein | |||

| GGTG_11844 | 5.97 | −3.62 | Putative cytochrome p450 monooxygenase protein/pisatin demethylase protein |

Ggt, the comparison of total Ggt transcriptome on wheat roots compared to Ggt on PDA plate; Bv+Ggt, the comparison of total Ggt transcriptome on wheat roots pretreated by Bv compared to Ggt on PDA plates; Bv+Ggt_vs_Ggt, the comparison of total Ggt transcriptome on wheat roots pretreated by Bv compared to Ggt on wheat roots. “−” represents negative values (downregulation).

HCA of DEGs

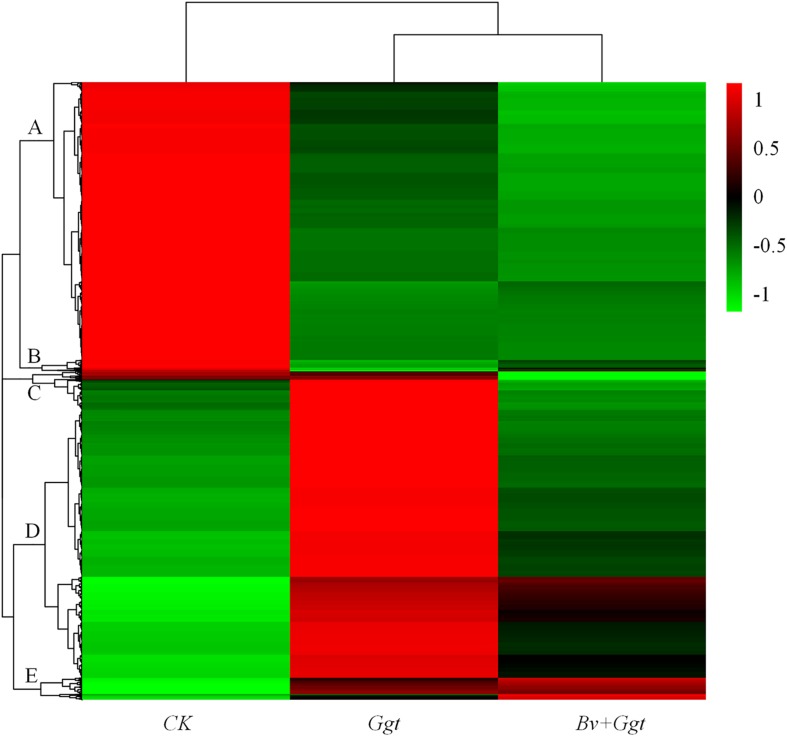

The HCA was conducted using those 4,260 DEGs that underwent significant changes in their expression in at least one replicate sample. This analysis revealed clear clustering of Ggt-infected wheat roots whether precolonized with Bv (Bv+Ggt) or not (Ggt), with the Ggt sample on PDA clustered into another branch entirely (Figure 1). Based on the expression levels of the DEGs, gene expression patterns were divided into five groups for the three experimental conditions. Clusters A and D contained the bulk of the DEGs. Cluster A and B were enriched in transcripts showing lower expression levels in Ggt-infected wheat roots, regardless of precolonization with Bv, versus the Ggt on PDA. Cluster C and D contained transcripts that were highly upregulated in the Ggt-infected wheat roots but whose upregulation was significantly suppressed in the presence of Bv or in Ggt on PDA. Cluster E contained those DEGs with very lower expression levels for Ggt on PDA while representing a higher expression level in the infected wheat roots with or without Bv.

FIGURE 1.

Hierarchical clustering analyses of all DEGs. The analysis was based on three treatments’ RPKM value from the transcriptomic data of CK, Ggt, and Bv+Ggt treatments; red indicates high expression of genes, while green indicates low expression of genes. CK, the Ggt sample on the PDA plates; Ggt, the wheat roots infected with pathogen Ggt; Bv+Ggt, the Ggt-infected wheat roots in the presence of Bv.

Functional Enrichment of DEGs

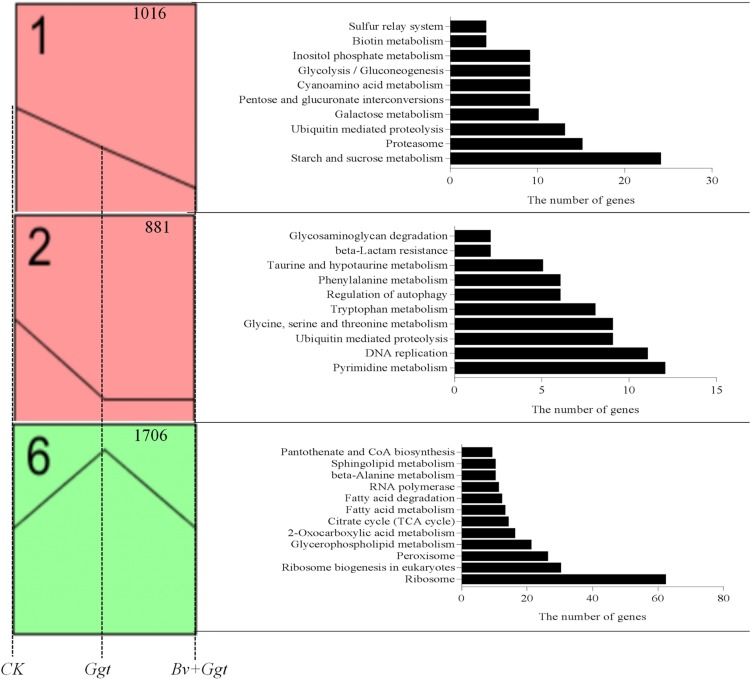

A total of 4,260 transcripts that showed significant differential expression in at least one sample were used for the STEM analysis, resulting in three significantly enriched expression profiles (Figure 2) out of the eight enriched expression profiles (P values <0.05). Profile 1 contained 1,016 transcripts, which were significantly enriched in 10 pathways based on the KEGG database. These pathways were mainly involved in carbohydrate metabolism, such as for starch and sucrose, pentose and glucuronate interconversions, galactose, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, and inositol phosphate. Compared with Ggt on PDA, all of the included DEGs were downregulated in Ggt in wheat roots with or without Bv. Yet, the expression levels of genes in Ggt in the Bv+Ggt-infected wheat roots were lower than those observed in Ggt-infected wheat roots. Profile 2 had 881 genes, enriched in 10 pathways, of which three were related to amino acid metabolism (e.g., taurine and hypotaurine; tryptophan, glycine, serine; and threonine and phenylalanine), while two pathways were involved in DNA replication and pyrimidine metabolism. These genes were downregulated in both the Ggt- and the Bv+Ggt-infected wheat roots relative to Ggt on PDA. Profile 6 contained the highest numbers of transcripts (1,706), which were enriched into 12 pathways, including lipid metabolism (e.g., sphingolipid, fatty acid, glycerophospholipid, and fatty acid degradation), tricarboxylic acid cycle, and peroxisome metabolism assigned to primary metabolism. Expression of these genes in Ggt-infected wheat roots was much higher than that on PDA plates or in Bv+Ggt-infected roots; hence, Bv might inhibit Ggt infection by regulating its primary metabolism.

FIGURE 2.

The significant (P values < 0.05) expression profiles generated by the analysis of the RPKM value based on the Ggt transcriptomic data of CK, Ggt, and Bv+Ggt treatments. The figure at the upper right corner represents the gene number. All significant annotated KEGG pathways for each profile are listed on the right shown by histograms. CK, the Ggt sample on the PDA plates; Ggt, the wheat roots infected with pathogen Ggt; Bv+Ggt, the Ggt-infected wheat roots in the presence of Bv.

DEGs for Secreted Proteins

During the process of host infection, fungi generally secrete a suite of proteins and enzymes to evade or counteract plant defense systems and alter the microenvironment of their host. Ggt reportedly harbors 1,001 secreted proteins with structures consisting of signal peptides and cleavage sites, subcellular targeting, transmembrane (TM) spanning regions, and glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor proteins (Xu et al., 2016). When compared to the gene ID of secreted proteins recently predicted by Xu et al. (2016), we identified a total of 458 (372 upregulated, 86 downregulated) and 198 (161 upregulated, 37 downregulated) secreted protein-coding DEGs (Supplementary Figure S3) among the 4,260 DEGs (Supplementary Figure S2A) in Ggt- and Bv+Ggt-infected roots, respectively. This clearly suggested that precolonization by Bv significantly regulated the expression of genes associated with secreted proteins in Ggt in wheat roots.

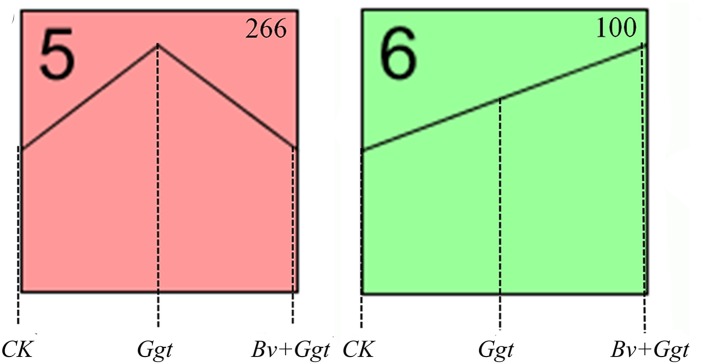

The STEM analysis revealed that all 469 DEGs encoding secreted proteins clustered significantly into profiles 5 and 6 (P values < 0.05) (Figure 3) but not so (P values> 0.05) in the other six profiles (not shown). Profile 5 included 266 genes whose expression was activated in Ggt-infected wheat roots but were mostly unaltered in the Bv+Ggt-infected roots or in Ggt on PDA (Figure 3). Profile 6 included 100 genes upregulated in the Ggt- and Bv+Ggt-infected wheat roots compared with Ggt grown on PDA (Figure 3). Moreover, the genes of both profiles were largely enriched in categories of catalytic activity, carbohydrate binding, and pattern binding. In profiles 5 and 6, a total of 137 genes (37.43%) participated in catalytic activities primarily related to hydrolases and oxidoreductases (Supplementary Tables S3, S4). Among these hypothesized hydrolase genes, most of them encode pectase, cellulase, xylanase, keratase, and peptidase, all of which play key roles in cell wall degradation. All the genes encoding oxidoreductase are capable of peroxidase activity with the function of pathogen self-defense against plant immune response. Additionally, the expression of Ggt genes encoding papain inhibitors involved in suppressing host protease activity was distinctly suppressed in Bv+Ggt-infected wheat roots. Collectively, these results suggested the presence of Bv directly and/or indirectly impaired the pathogenicity (e.g., cell wall degradation enzymes, oxidoreductases, and papain inhibitors, among others) of Ggt in wheat roots through complex regulatory mechanisms.

FIGURE 3.

The significant (P values < 0.05) expression profiles for identified secreted protein-coding genes. The analysis was based on the RPKM value of the Ggt transcriptomic data from CK, Ggt, and Bv+Ggt treatments. CK, the Ggt sample on the PDA plates; Ggt, the wheat roots infected with pathogen Ggt; Bv+Ggt, the Ggt-infected wheat roots in the presence of Bv.

DEGs for Fungal Pathogenicity

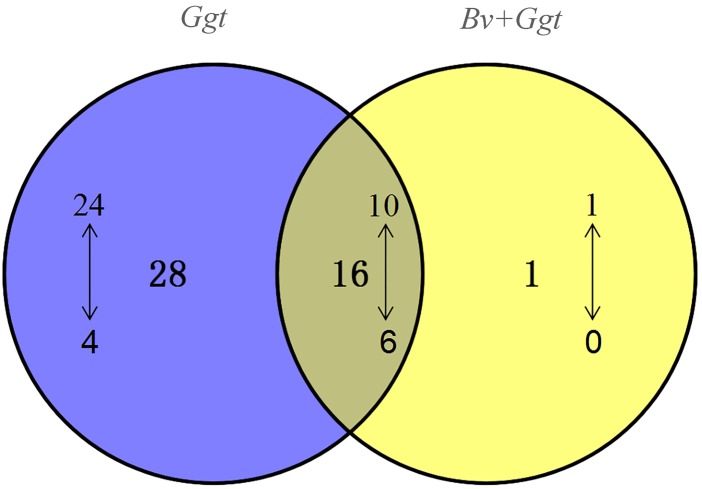

Based on the BLAST analyses of the PHI database, a total of 151 pathogenicity-related genes were identified in the Ggt genome (Supplementary Table S5). Of those, 83 genes are recognized as established determinants of pathogenicity in various pathogenic fungi (Supplementary Table S5), for which 44 (34 upregulated, 10 downregulated) were significantly expressed in Ggt-infected wheat roots in the absence of Bv, whereas 17 (11 upregulated, 6 downregulated) were significantly expressed in Bv+Ggt-infected wheat roots. The distribution of up- and downregulated Ggt pathogenicity DEGs is depicted in the Venn diagram (Figure 4). Evidently, 28 pathogenicity genes were uniquely regulated in Ggt-infected wheat roots, of which 4 genes – CTB5, Sc Srb10, ACP, and DEP4 – were downregulated during Ggt infection (Supplementary Table S6). Only one gene coding for appressorial penetration-associated GAS2 was found upregulated (2.69 fold change) in Bv+Ggt-infected wheat roots but not in Ggt-infected wheat roots. These results suggested that the presence of the biocontrol bacterium Bv reduces the pathogenesis of Ggt during its infection of wheat roots.

FIGURE 4.

The numbers of DEGs encoding Ggt pathogenicity proteins. The Venn diagram illustrates the shared and specific pathogenicity genes generated by the comparative Ggt transcriptomic data analysis of Ggt-infected wheat roots with or without Bv compared to Ggt on PDA plates. The upward (or downward)-pointing arrow represents up (or down)-regulated gene expression. Ggt, the comparison of total Ggt transcriptome on wheat roots compared to Ggt on PDA plate; Bv+Ggt, the comparison of total Ggt transcriptome on wheat roots pretreated by Bv compared to Ggt on PDA plates.

qRT-PCR Validation

The expression of the target genes, normalized by three internal reference genes, was downregulated between Ggt- and Bv+Ggt-infected wheat roots. Comparing the ratio of qRT-PCR expression and RPKM values for the Bv+Ggt-infected to the Ggt-infected wheat roots revealed they were mostly consistent, indicating the RNA-Seq data were robust (Supplementary Table S7).

Discussion

This study compared the transcriptomes of Ggt and Ggt-infected wheat root in the absence and presence of the biocontrol bacterium Bv using the RNA-Seq platform. A total of 4,134 and 2,011 twofold DEGs were, respectively identified from the Ggt in the Ggt-infected roots without and with Bv relative to Ggt grown on PDA plates. Numbers of the upregulated and downregulated DEGs in the Ggt-infected roots were, respectively reduced by 55.3% and 47.1% when Bv had precolonized wheat roots. Some of these DEGs, whether related to Ggt pathogenicity or not, are consistent with those reported by Yang et al. (2015), but many of them were newly identified and, thus, warrant future investigation. However, only 31 DEGs (2 upregulated, 29 downregulated) were detected by directly comparing the Ggt- and Bv+Ggt-infected wheat root libraries (Table 1). These limited numbers of DEGs may truly reflect the direct or indirect (e.g., induced plant resistance) regulation of Ggt’s gene expression by endophytic Bv in wheat roots. Previous studies have shown that Bv can mutually coexist with plants and produce antifungal metabolites such as iturins in vitro and in vivo, which might have contributed to the changed Ggt transcriptome in the infected wheat roots (Gong et al., 2015; Cai et al., 2017; Kang et al., 2018). Moreover, beneficial bacteria impose small impacts upon plant root transcriptomes (Pieterse et al., 2014), and they may impose similarly small impacts upon fungal transcriptomes. This may explain the small number of DEGs observed between Ggt- and Bv+Ggt-infected wheat roots in this study.

Many secretory proteins have crucial functions in the fungal infection process. For example, CWDEs are the major pathogenicity factors involved in plant cell wall breakdown and are secreted by many pathogens during infection, such as Fusarium graminearum (Zhang et al., 2012), Colletotrichum orbiculare (Gan et al., 2013), Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (Alkan et al., 2015), Zymoseptoria tritici (McDonald et al., 2015), Colletotrichum graminicola (Torres et al., 2016), Dothistroma septosporum (Bradshaw et al., 2016), and Leptosphaeria maculans (Gervais et al., 2017). For example, the expression of genes encoding CWDEs (e.g., endo-1,4-b-xylanase, glycoside hydrolase family 61) were highly upregulated in Magnaporthe oryzae, a rice fungus closely related to the pathogen Ggt (Kawahara et al., 2012). Thus, inhibition of CWDE gene expression is one of the mechanisms by which bacteria exert biocontrol in vitro (Mela et al., 2011; Gkarmiri et al., 2015). Our in vivo test also demonstrated the biocontrol efficacy of Bv against Ggt might contribute to the inhibition of gene expression encoding CWDEs, since these genes were significantly upregulated in Ggt-infected roots but downregulated in Bv+Ggt-infected wheat roots compared to Ggt grown on PDA plates (Figure 3, Table 1, and Supplementary Tables S3, S4). For instance, the expression of cutinase 1 and xylanase in Bv+Ggt-infected roots was at least twofold lower than that in Ggt-infected roots.

Papain-like cysteine proteases (PLCPs) are a large class of proteolytic enzymes found in most plant species (Misas-Villamil et al., 2016). According to recent studies, a plant can protect itself from pest or pathogen attacks by producing PLCPs (Misas-Villamil et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2018); however, in the long-term battle waged between pathogens and plants, pathogens will evolve a PLCP inhibitor (e.g., EPIC2B and avirulence protein 2) to counteract host-derived PLCPs (Kruger et al., 2002; Tian et al., 2004, 2005, 2007). In line with this, we found that the expression of PLCP inhibitor-encoding genes was upregulated in Ggt-infected wheat roots compared with Ggt grown on PDA (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table S4), indicating that one or more PLCP inhibitors may play an important role in the process of Ggt infection. In stark contrast, the expression of PLCP inhibitor-encoding genes in Ggt-infected wheat roots precolonized by Bv was reduced substantially (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table S4). This result strongly suggests that low-level expression of PLCP inhibitor-encoding genes may be one of the biocontrol mechanisms exerted by Bv toward the fungal pathogen Ggt.

As a member of the peroxidases, catalase could mediate the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide into water and molecular oxygen, so as to protect the pathogens from reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced by both fungi themselves and host plants (Gardiner et al., 2015; Mir et al., 2015). Work by Singh et al. (2012) revealed that in the response of the fungal pathogen Verticillium longisporum to Brassica napus xylem sap, catalase peroxidase (VlCPEA) was the most upregulated protein, whereas knockdowns of VlCPEA-encoding genes resulted in sensitivity against ROS. In our study, many genes with predicted peroxidase activity (e.g., catalase) were found upregulated (Figure 3, Table 1, and Supplementary Table S4) during the pathogen Ggt’s infection of wheat roots, a result that agrees with previous reports (Govrin and Levine, 2000; Singh et al., 2012; Bao et al., 2014). This result suggests that, similar to the mechanism underlying other pathogenic infections, catalase peroxidase might also participate in protecting the fungus Ggt from the oxidative stress generated by wheat plants (Singh et al., 2012). Yet, because the expression of genes encoding peroxidase (e.g., catalase) was decreased in Bv+Ggt-infected wheat roots (Figure 3, Table 1, and Supplementary Table S4), the presence of biocontrol bacteria in planta could have diminished such detoxification activity by reducing peroxidase secretion.

ABA is a crucial molecule for regulating the growth and development of plants, and their stress responses and pathogenicity, and it has been widely studied (Spence et al., 2015). By examining the role of ABA produced by M. oryzae in rice leaves, Spence et al. (2015) suggested that it enhances disease severity in two ways, by increasing plant susceptibility and accelerating the pathogenicity of the pathogen itself. For instance, Pseudomonas syringae indirectly utilizes ABA as an effector molecule to modulate endogenous host biosynthesis of ABA, thus perturbing the ABA-mediated host defense responses (Lievens et al., 2017). In this current study, we identified a homologous gene (ABA3) encoding an enzyme involved in ABA biosynthesis (Siewers et al., 2006; Fan et al., 2009). The expression of this gene was 7.77-fold higher in Ggt-infected wheat roots but was lowered by almost 50% to being 4.11-fold higher in Bv+Ggt-infected wheat roots relative to PDA (Table 1). This result suggests that ABA, at least, is likely a critical component in plant–pathogen interactions between wheat and Ggt, whereas Bv might also use this ABA functioning to impair pathogen infection by disturbing Ggt-derived ABA synthesis and thus limiting fungal pathogenesis. Targeting these candidate pathogenicity genes/factor through further experimental analysis, such as gene knockouts in Ggt, will enable a better understanding of the biocontrol mechanisms of Bv that act on the pathogen Ggt.

Many plant pathogenic fungi have evolved the capacity to breach intact cuticles of their plant hosts by using an infection structure called the appressorium (Ryder and Talbot, 2015). Previous studies reported that during infection with a pathogen, the accumulation of glycerol in appressoria/hyphopodia results in highly localized turgor pressure upon the cell wall, and this further assists fungal pathogens to overcome cellular barriers for successful hyphal infection and extension (DeJong et al., 1997). For example, Martin-Urdiroz et al. (2016) have shown that glycerol accumulation of the appressorium in rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae drives turgor-mediated penetration of the rice leaf. However, work by Sha et al. (2016) indicated that, in vitro, the biocontrol strain Bacillus subtilis suppressed the appressorial formation of Magnaporthe oryzae. The metabolism of glycerophospholipids, carbohydrate, and peroxisome may have direct or indirect effects on the biosynthesis of glycerol or its precursors’ replenishment (Supplementary Figure S4). As shown in profile 6, the activation or enhancement of the metabolism of glycerol (Figure 2) could be beneficial for Ggt to infect wheat roots. Conversely, the metabolism of glycerol was suppressed in Bv+Ggt-infected wheat roots. Thus, limiting the expression of glycerol synthesis-related genes in Ggt may be among the biocontrol strategies that Bv employs in planta.

Inexplicably, when compared with Ggt on PDA, 10 pathogenicity-related genes were downregulated in Ggt-infected wheat roots, and likewise six genes in Bv+Ggt-infected wheat root (Figure 4). These genes mainly encode MoAAT (4-aminobuty-rate aminotransferase), Chi2 (endochitinase), avenacinase, Ss-ggt1 (gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase), and SS-odc2 (oxalate decarboxylase). Although we do not know why these pathogenicity-related genes are downregulated in infected wheat roots, plausible reasons include the following: (1) these genes are host dependent and their activation is not essential in the Ggt–wheat ecological system; (2) the internal environment of wheat roots is not suitable for the expression of these genes; and (3) these genes are highly expressed in PDA, resulting in relatively low expression in wheat. As to which explanation is most probable and operative, this ought to be tested in the future.

Conclusion

This study has provided novel insights into a potential pathogenicity mechanism of Ggt in wheat roots, whether strain CC09 is present or absent (relative to the Ggt grown on PDA plates) through comparative analysis of their transcriptomes using the Illumina platform. Many novel candidate genes related to Ggt pathogenesis were identified, and some potential targets of biocontrol bacteria were discussed. The gene expression data presented in this study suggest that the following mechanisms likely play a role in the biocontrol efficacy of Bv against Ggt in wheat: (a) decreased amount of fungus-derived CWDEs; (b) repressed genes encoding papain inhibitors, catalase-3, and ABA3; and (c) limited hyphopodia formation that impedes pathogen infection. In addition, our results enhance our knowledge of not only the pathogenicity of Ggt at the early infection stage in wheat roots but also the potential mechanism of an endophytic biocontrol bacterium in planta. Nonetheless, to what extent Bv-induced plant defense fosters the biological control effect of Bv upon Ggt infection remains to be elucidated.

Data Availability

The datasets generated for this study are available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information, PRJNA 485739 and PRJNA496308.

Author Contributions

CL, YX, and XK designed the research study. XK, YG, and SL performed the experiments. XK and CL wrote the manuscript and analyzed the data. CL, XK, SL, YG, LX, and LW assisted in structuring and editing the work. All authors contributed substantially to revisions and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Prof. Jian Heng (Department of Plant Pathology, Chinese Agricultural University, Beijing, China) for providing the fungal pathogen Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici. We thank the two reviewers and Charlesworth Author Services for reviewing the manuscript and improving the quality of the writing, respectively.

Funding. This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 31471810, 41773083, and 31272081), the National Key R&D Project from the Minister of Science and Technology, China (Grant No. 2017YFD0800705), and the Program B for Outstanding Ph.D. Candidate of Nanjing University.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01474/full#supplementary-material

Hierarchical clustering of transcripts for each replicate from Ggt and Bv+Ggt treatments. Hierarchical clustering analysis of the transcriptional profiles was performed using the hclust command in R and the default complete linkage method. Each gene’s expression was Z-score normalized separately within each of the three data sets. Rows (genes) were clustered hierarchically. Columns (RNA samples) were sorted by sample metadata. The genes with higher (red) or lower (blue) expression are represented. CK, the Ggt sample on the PDA plates; Ggt, the wheat roots infected with pathogen Ggt; Bv+Ggt, the Ggt-infected wheat roots in the presence of Bv.

The DEG expression profile obtained from the comparison of total Ggt transcriptome on wheat roots pretreated by Bv or not compared to Ggt on the PDA plate. (A) The number of Ggt DEGs in response to Ggt- and Bv+Ggt-infected wheat roots, respectively. (B) Venn diagram illustrating the number of Ggt DEGs upregulated or downregulated in Ggt- and Bv+Ggt-infected wheat roots. (C) The level of Ggt gene expression in response to Ggt- and Bv+Ggt-infected wheat roots, respectively. The expression level is shown along the horizontal axis, while values on the vertical axis indicate the gene number. CK, the Ggt sample on the PDA plates; Ggt, the wheat roots infected with pathogen Ggt; Bv+Ggt: the Ggt-infected wheat roots in the presence of Bv.

The number of DEGs encoding secreted proteins obtained from the comparison of total Ggt transcriptome on wheat roots pretreated by Bv or not compared to Ggt on the PDA plate.

Overview of the glycerol biosynthesis in fungus. The solid lines, dashed lines, circle marks, and frames represent the direct link, indirect links/unknown reaction, chemical compound, and metabolism/enzymes, respectively.

The selected DEGs and the sequences of primer pairs used for the qRT-PCR experiment.

Summary of the sequence analysis after Illumina sequencing.

List of molecular functions for the identified secreted protein-coding genes, based on the data of profile 6 in Figure 3.

List of molecular functions for identified secreted protein-coding genes, based on the data of profile 5 in Figure 3.

The pathogenicity-related genes identified in the Ggt genome.

The expression profile of DEGs assigned to pathogenicity proteins.

Relative expression levels of selected pathogenicity-related DEGs in Ggt- and Bv+Ggt-infected wheat roots.

References

- Alexa A., Rahnenfuhrer J. (2010). topGO: Enrichment Analysis for Gene Ontology. R Package Version 2.36.0. [Google Scholar]

- Alkan N., Friedlander G., Ment D., Prusky D., Fluhr R. (2015). Simultaneous transcriptome analysis of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides and tomato fruit pathosystem reveals novel fungal pathogenicity and fruit defense strategies. New Phytol. 205 801–815. 10.1111/nph.13087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders S., Huber W. (2012). Differential Expression of RNA-Seq Data at the Gene Level—the DESeq Package. Heidelberg: EMBL. [Google Scholar]

- Bao G. H., Bi Y., Li Y. C., Kong Z. H., Hu L. G., Ge Y. H., et al. (2014). Overproduction of reactive oxygen species involved in the pathogenicity of Fusarium in potato tubers. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 86 35–42. 10.1016/j.pmpp.2014.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bithell S. L., McKay A. C., Butler R. C., Cromey M. G. (2016). Consecutive wheat sequences: effects of contrasting growing seasons on concentrations of Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici DNA in soil and take-all disease across different cropping sequences. J. Agric. Sci. 154 472–486. 10.1017/S002185961500043X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw R. E., Guo Y., Sim A. D., Kabir M. S., Chettri P., Ozturk I. K., et al. (2016). Genome-wide gene expression dynamics of the fungal pathogen Dothistroma septosporum throughout its infection cycle of the gymnosperm host Pinus radiata. Mol. Plant Pathol. 17 210–224. 10.1111/mpp.12273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X. C., Kang X. X., Xi H., Liu C. H., Xue Y. R. (2016). Complete genome sequence of the endophytic biocontrol strain Bacillus velezensis CC09. Genom. Announc. 4:e01048-16. 10.1128/genomeA.01048-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X. C., Liu C. H., Wang B. T., Xue Y. R. (2017). Genomic and metabolic traits endow Bacillus velezensis CC09 with a potential biocontrol agent in control of wheat powdery mildew disease. Microbiol. Res. 196 89–94. 10.1016/j.micres.2016.12007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daval S., Lebreton L., Gazengel K., Boutin M., Guillerm-Erckelboudt A., Sarniguet A. (2011). The biocontrol bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf29Arp strain affects the pathogenesis-related gene expression of the take-all fungus Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici on wheat roots. Mol. Plant Pathol. 12 839–854. 10.1111/J.1364-3703.2011715.X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeJong J. C., MCCormack B. J., Smirnoff N., Talbot N. J. (1997). Glycerol generates turgor in rice blast. Nature 389 244–245. 10.1038/38418 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dori S., Solel Z., Barash I. (1995). Cell wall-degrading enzymes produced by Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici in vitro and in vivo. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 46 189–198. 10.1006/pmpp.1995.1015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Durán P., Acuña J. J., Jorquera M. A., Azcón R., Paredes C., Rengel Z., et al. (2014). Endophytic bacteria from selenium-supplemented wheat plants could be useful for plant-growth promotion, biofortification and Gaeumannomyces graminis biocontrol in wheat production. Biol. Fertil. Soils 50 983–990. 10.1007/s00374-014-0920-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst J., Nau G. J., Bar-Joseph Z. (2005). Clustering short time series gene expression data. Bioinformatics 21 i159–i168. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J., Hill L., Crooks C., Doerner P., Lamb C. (2009). Abscisic acid has a key role in modulating diverse plant–pathogen interactions. Plant Physiol. 150 1750–1761. 10.1104/pp.109.137943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan P., Ikeda K., Irieda H., Narusaka M., O’Connell R. J., Narusaka Y., et al. (2013). Comparative genomic and transcriptomic analyses reveal the hemibiotrophic stage shift of Colletotrichum fungi. New Phytol. 197 1236–1249. 10.1111/nph.12085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner M., Thomas T., Egan S. (2015). A glutathione peroxidase (GpoA) plays a role in the pathogenicity of Nautella italica strain R11 towards the red alga Delisea pulchra. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 91 1–5. 10.1093/femsec/fiv021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gervais J., Plissonneau C., Linglin J., Meyer M., Labadie K., Cruaud C., et al. (2017). Different waves of effector genes with contrasted genomic location are expressed by Leptosphaeria maculans during cotyledon and stem colonization of oilseed rape. Mol. Plant Pathol. 18 1113–1126. 10.1111/mpp.12464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gkarmiri K., Finlay R. D., Alstrom S., Thomas E., Cubeta M. A., Hogberg N. (2015). Transcriptomic changes in the plant pathogenic fungus Rhizoctonia solani AG-3 in response to the antagonistic bacteria Serratia proteamaculans and Serratia plymuthica. BMC Genom. 16:630. 10.1186/s12864-015-1758-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong A., Li H., Yuan Q., Song X., Yao W., He W., et al. (2015). Antagonistic mechanism of iturin A and plipastatin A from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens S76-3 from wheat spikes against Fusarium graminearum. PLoS One 10:e0116871. 10.1371/journal.pone.0116871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govrin E. M., Levine A. (2000). The hypersensitive response facilitates plant infection by the necrotrophic pathogen Botrytis cinerea. Curr. Biol. 10 751–757. 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00560-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing L., Guo D. D., Hu W. J., Niu X. F. (2017). The prediction of a pathogenesis-related secretome of Puccinia helianthi through high-throughput transcriptome analysis. BMC Bioinform. 18:166. 10.1186/s12859-017-1577-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang X. X., Zhang W. L., Cai X. C., Zhu T., Xue Y. R., Liu C. H. (2018). Bacillus velezensis CC09: a potential ‘vaccine’ for controlling wheat diseases. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 31 623–632. 10.1094/MPMI-09-17-0227-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara Y., Oono Y., Kanamori H., Matsumoto T., Itoh T. (2012). Simultaneous RNA-seq analysis of a mixed transcriptome of rice and blast fungus interaction. PLoS One 7:e49423. 10.1371/journal.pone.0049423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger J., Thomas C. M., Golstein C., Dixon M. S., Smoker M., Tang S. K., et al. (2002). A tomato cysteine protease required for Cf-2-dependent disease resistance and suppression of autonecrosis. Science 296 744–747. 10.1126/science.1069288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak Y. S., Weller D. M. (2013). Take-all of wheat and natural disease suppression: a review. Plant Pathol. J. 29 125–135. 10.5423/PPJ.SI.07.2012.0112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagzian A., Riseh R. S., Khodaygan P., Sedaghati E., Dashti H. (2013). Introduced Pseudomonas fluorescens VUPf5 as an important biocontrol agent for controlling Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici the causal agent of take-all disease in wheat. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Protoc. 46 2104–2116. 10.1080/03235408.2013.785123 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li R. Q., Yu C., Li Y. R., Lam T. W., Yiu S. M., Kristiansen K., et al. (2009). SOAP2: an improved ultrafast tool for short read alignment. Bioinformatics 25 1966–1967. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lievens L., Pollier J., Goossens A., Beyaert R., Staal J. (2017). Abscisic acid as pathogen effector and immune regulator. Front. Plant Sci. 8:587. 10.3389/fpls.2017587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Huang L. L., Kang Z. S., Buchenauer H. (2011). Evaluation of endophytic bacterial strains as antagonists of take-all in wheat caused by Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici in greenhouse and field. J. Pest Sci. 84 257–264. 10.1007/s10340-011-0355-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Qiao H. P., Huang L. L., Buchenauer H., Han Q. M., Kang Z. H., et al. (2009). Biological control of take-all in wheat by endophytic Bacillus subtilis E1R-j and potential mode of action. Biol. Control 49 277–285. 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2009.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H. J., Hu M. H., Wang Q., Cheng L., Zhang Z. B. (2018). Role of papain-like cysteine proteases in plant development. Front. Plant Sci. 9:1717. 10.3389/fpls.2018.01717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2[-delta delta C(T)] method. Methods 25 402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J., Zhang X., Huang H., Zhai F., An T. C., An D. R. (2013). Control effect and mechanism of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens Ba-168 on wheat take-all. Acta Phyto-phylac. Sin. 40 475–476. 10.13802/j.cnki.zwbhxb.2013.05.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Urdiroz M., Oses-Ruiz M., Ryder L. S., Talbot N. J. (2016). Investigating the biology of plant infection by the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. Fungal Genet. Biol. 90 61–68. 10.1016/j.fgb.2015.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald M. C., McDonald B. A., Solomon P. S. (2015). Recent advances in the Zymoseptoria tritici–wheat interaction: insights from pathogenomics. Front. Plant Sci. 6:102. 10.3389/fpls.2015.00102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mela F., Fritsche K., de Boer W., van Veen J. A., de Graaff L. H., van den Berg M., et al. (2011). Dual transcriptional profiling of a bacterial/fungal confrontation: Collimonas fungivorans versus Aspergillus niger. ISME J. 5 1494–1504. 10.1038/ismej.2011.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mir A. A., Park S., Abu Sadat M., Kim S., Choi J., Jeon J., et al. (2015). Systematic characterization of the peroxidase gene family provides new insights into fungal pathogenicity in Magnaporthe oryzae. Sci. Rep. 5:11831. 10.1038/srep11831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misas-Villamil J. C., van der Hoorn R. A. L., Doehlemann G. (2016). Papain-like cysteine proteases as hubs in plant immunity. New Phytol. 212 902–907. 10.1111/nph.14117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse C. M., Zamioudis C., Berendsen R. L., Weller D. M., Van Wees S. C., Bakker P. A. (2014). Induced systemic resistance by beneficial microbes. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 52 347–375. 10.1146/annurev-phyto-082712-102340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2009). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Ryder L. S., Talbot N. J. (2015). Regulation of appressorium development in pathogenic fungi. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 26 8–13. 10.1016/j.pbi.2015.05.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sha Y. X., Wang Q., Li Y. (2016). Suppression of Magnaporthe oryzae and interaction between Bacillus subtilis and rice plants in the control of rice blast. Springerplus 5:1238. 10.1186/s40064-016-2858-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siewers V., Kokkelink L., Smedsgaard J., Tudzynski P. (2006). Identification of an abscisic acid gene cluster in the grey mold Botrytis cinerea. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72 4619–4626. 10.1128/AEM.02919-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S., Braus-Stromeyer S. A., Timpner C., Valerius O., Von T. A., Karlovsky P., et al. (2012). The plant host Brassica napus induces in the pathogen Verticillium longisporum the expression of functional catalase peroxidase which is required for the late phase of disease. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 25 569–581. 10.1094/MPMI-08-11-0217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence C. A., Lakshmanan V., Donofrio N., Bais H. P. (2015). Crucial roles of abscisic acid biogenesis in virulence of rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. Front. Plant Sci. 6:1082. 10.3389/fpls.2015.01082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian M., Win J., Song J., van der Hoorn R., van der Knaap E., Kamoun S. (2007). A Phytophthora infestans cystatin-like protein targets a novel tomato papain-like apoplastic protease. Plant Physiol. 143 364–377. 10.1104/pp.106.090050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian M. Y., Benedetti B., Kamoun S. (2005). A second Kazal-like protease inhibitor from Phytophthora infestans inhibits and interacts with the apoplastic pathogenesis-related protease P69B of tomato. Plant Physiol. 138 1785–1793. 10.1104/pp.105.061226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian M. Y., Huitema E., Da Cunha L., Torto-Alalibo T., Kamoun S. (2004). A Kazal-like extracellular serine protease inhibitor from Phytophthora infestans targets the tomato pathogenesis-related protease P69B. J. Biol. Chem. 279 26370–26377. 10.1074/jbc.M400941200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres M. F., Ghaffari N., Buiate E. A. S., Moore N., Schwartz S., Johnson C. D., et al. (2016). A Colletotrichum graminicola mutant deficient in the establishment of biotrophy reveals early transcriptional events in the maize anthracnose disease interaction. BMC Genom. 17:202. 10.1186/s12864-016-2546-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnes G. R., Bolker B., Bonebakker L., Gentleman R., Huber W., Liaw A., et al. (2015). Gplots: Various R Programming Tools for Plotting Data. R Package Version 3.0.1. Available at: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/gplots/index.html (accessed January 27, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- Wu X. B., Sun R. K., Wu Y. X., Wang Z. Y., Wu X. X., Mao Z. C., et al. (2012). Screening and identification of biocontrol Bacillus strains against take-all of wheat. Acta Agric. Jiangxi 24 53–55. 10.3969/j.issn.1001-8581.2012.11.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X. H., He Q., Chen C., Zhang C. L. (2016). Differential communications between fungi and host plants revealed by secretome analysis of phylogenetically related endophytic and pathogenic fungi. PLoS One 11:e0163368. 10.1371/journal.pone.0163368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Han X., Zhang F., Goodwin P. H., Yang Y., Li J., et al. (2018). Screening Bacillus species as biological control agents of Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici on wheat. Biol. Control 118 1–9. 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2017.11.004 28977681 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L. R., Huang Y., Liang S., Xue B. G., Quan X. (2012). “Screening wheat take-all disease mutant by Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation,” in Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of Chinese Society for Plant Pathology, ed. Guo Z. J. (Beijing: China Agriculture Press; ), 555. [Google Scholar]

- Yang L. R., Xie L. H., Xue B. G., Goodwin P. H., Quan X., Zheng C. L., et al. (2015). Comparative transcriptome profiling of the early infection of wheat roots by Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici. PLoS One 10:e0120691. 10.1371/journal.pone.0120691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M., Wen S., Mavrodi D. V., Mavrodi O. V., von Wettstein D., Thomashow L. S., et al. (2014). Biological control of wheat root diseases by the CLP-producing strain Pseudomonas fluorescens HC1-07. Phytopathology 104 248–256. 10.1094/PHYTO-05-13-0142-R [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M. M., Mavrodi D. V., Mavrodi O. V., Thomashow L. S., Weller D. M. (2017). Construction of a recombinant strain of Pseudomonas fluorescens producing both phenazine-1-carboxylic acid and cyclic lipopeptide for the biocontrol of take-all disease of wheat. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 149 683–694. 10.1007/s10658-017-1217-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y. T., Kang Z. S., Han Q. M., Buchenauer H., Huang L. L. (2010). Immunolocalization of 1, 3-β-glucanases secreted by Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici in infected wheat roots. J. Phytopathol. 158 344–350. 10.1111/j.1439-0434.2009.01614.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. W., Jia L. J., Zhang Y., Jiang G., Li X., Zhang D., et al. (2012). In planta stage-specific fungal gene profiling elucidates the molecular strategies of Fusarium graminearum growing inside wheat coleoptiles. Plant Cell 24 5159–5176. 10.1105/tpc.112.105957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Hierarchical clustering of transcripts for each replicate from Ggt and Bv+Ggt treatments. Hierarchical clustering analysis of the transcriptional profiles was performed using the hclust command in R and the default complete linkage method. Each gene’s expression was Z-score normalized separately within each of the three data sets. Rows (genes) were clustered hierarchically. Columns (RNA samples) were sorted by sample metadata. The genes with higher (red) or lower (blue) expression are represented. CK, the Ggt sample on the PDA plates; Ggt, the wheat roots infected with pathogen Ggt; Bv+Ggt, the Ggt-infected wheat roots in the presence of Bv.

The DEG expression profile obtained from the comparison of total Ggt transcriptome on wheat roots pretreated by Bv or not compared to Ggt on the PDA plate. (A) The number of Ggt DEGs in response to Ggt- and Bv+Ggt-infected wheat roots, respectively. (B) Venn diagram illustrating the number of Ggt DEGs upregulated or downregulated in Ggt- and Bv+Ggt-infected wheat roots. (C) The level of Ggt gene expression in response to Ggt- and Bv+Ggt-infected wheat roots, respectively. The expression level is shown along the horizontal axis, while values on the vertical axis indicate the gene number. CK, the Ggt sample on the PDA plates; Ggt, the wheat roots infected with pathogen Ggt; Bv+Ggt: the Ggt-infected wheat roots in the presence of Bv.

The number of DEGs encoding secreted proteins obtained from the comparison of total Ggt transcriptome on wheat roots pretreated by Bv or not compared to Ggt on the PDA plate.

Overview of the glycerol biosynthesis in fungus. The solid lines, dashed lines, circle marks, and frames represent the direct link, indirect links/unknown reaction, chemical compound, and metabolism/enzymes, respectively.

The selected DEGs and the sequences of primer pairs used for the qRT-PCR experiment.

Summary of the sequence analysis after Illumina sequencing.

List of molecular functions for the identified secreted protein-coding genes, based on the data of profile 6 in Figure 3.

List of molecular functions for identified secreted protein-coding genes, based on the data of profile 5 in Figure 3.

The pathogenicity-related genes identified in the Ggt genome.

The expression profile of DEGs assigned to pathogenicity proteins.

Relative expression levels of selected pathogenicity-related DEGs in Ggt- and Bv+Ggt-infected wheat roots.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information, PRJNA 485739 and PRJNA496308.