Abstract

Lymphatic filariasis is an infection transmitted by blood-sucking mosquitoes with filarial nematodes of the species Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi und B. timori . It is prevalent in tropical countries throughout the world, with more than 60 million people infected and more than 1 billion living in areas with the risk of transmission. Worm larvae with a length of less than 1 mm are transmitted by mosquitoes, develop in human lymphatic tissue to adult worms with a length of 7–10 cm, live in the human body for up to 10 years and produce millions of microfilariae, which can be transmitted further by mosquitoes. The adult worms can be easily observed by ultrasonography because of their size and fast movements (the so-called “filarial dance sign”), which can be differentiated from other movements (e. g., blood in venous vessels) by their characteristic movement profile in pulsed-wave Doppler mode. Therapeutic options include (combinations of) ivermectin, albendazole, diethylcarbamazine and doxycycline. The latter depletes endosymbiotic Wolbachia bacteria from the worms and thus sterilizes and later kills the adult worms (macrofilaricidal or adulticidal effect).

Key words: parasite, guideline, elastography, contrast-enhanced ultrasound

Introduction

Parasitic diseases are rarely encountered in Europe and the clinical and imaging features are generally not well known. In the era of worldwide migration and refugees, knowledge of such diseases has gained importance as illustrated by multiple recently published reports of hydatid diseases 1 2 3 4 5 , schistosomiasis 6 7 , fasciolosis 8 , ascariasis 9 , liver flukes 10 , toxocariasis and other rare intestinal diseases 11 12 . This article describes the clinical and imaging features along with current treatment strategies for filariasis.

Across the world, nematodes (roundworms) cause a wide variety of parasitic infections of the subcutaneous and lymphatic tissue of almost all organs with significant economic and psychosocial damage. Three species, Wuchereria bancrofti (90% of lymphatic filariasis infections, humans are the only hosts), Brugia malayi (up to 10% of lymphatic filariasis infections, humans, domestic and wild animals are hosts), and B. timori , cause lymphatic filariasis (LF) affecting approx. 60 million patients worldwide 13 . Lymphangitis, lymphedema and the formation of fibrosis, sclerosis and scars are the pathophysiologically important sequelae. Loiasis and onchocerciasis are rarely associated with lymphedema.

LFI caused by W. bancrofti is common in the tropical regions of India and Southeast Asia, Pacific islands, Latin America and Caribbean area as well as in sub-Saharan Africa. B. malayi occurs mainly in China, India, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines and the Pacific islands. B. timori occurs only on the Timor Island of Indonesia and some neighboring islands.

Nematodes are transmitted by mosquitoes. The mosquito vectors for filariasis vary geographically including the genus Culex, Anopheles, Aedes, Mansonia, and Coquillettidia. Humans are the so-called definitive host where the sexual stages develop. The adult worms do not replicate in humans. Therefore travelers have a short exposure to infective larvae and the disease ceases generally after a certain period. Transmission most often happens in childhood 14 15 . The disease is almost not detected in travelers and very rarely in expatriates.

The larvae develop into mature adult worms, which mate and produce sheathed microfilariae with mainly nocturnal periodicity. In addition, a mosquito ingests the microfilariae again during a blood meal; these develop into larvae, which can infect another human when the mosquito takes a subsequent blood meal, completing the life cycle.

The prevalence increases with age. Travelers usually have insufficient exposure to filariasis to develop sufficiently high worm burdens. More often a local hypersensitivity including eosinophilic infiltrate with lymphangitis and lymphadenopathy, urticaria, and peripheral eosinophilia is observed.

Humans are infected during a blood meal. The mosquito-transmitted larvae develop into mature adult worms in about 9 months. The adult parasites can be observed in lymphatic vessels. Larvae appear in the blood stream after a prepatent period of about 12 months. They often show periodic activity in the blood stream. In areas with mosquitos that are active at night, the larvae appear in the blood in astonishingly precise nocturnal periods. In areas with mosquitos that are active during the day, the larvae can be detected in the blood during the day, e. g., Brugia malayi . The adult worms survive for approximately five years. The size of the filariae is species-dependent from 10 –100 mm in length and 0.07×0.1 mm in width. In ultrasound images the echoes appear bigger than the real worm. Measurements resulted in echoes of up to 2.5 mm.

Filarial disease is influenced by the extent and duration of exposure to infective mosquito bites, i. e., the quantity of accumulating adult worm antigen in the lymphatics. The adult worms in the lymphatics induce an inflammatory response 16 but also mechanical damage 17 . As rickettsia-like organisms, Wolbachia are endosymbiotic to adult worms 18 and may be responsible for the inflammatory changes 19 20 21 22 23 24 . Treatment with antibiotics such as doxycycline or rifampicin kills Wolbachia and as a result the adult worms become sterile and can no longer reproduce. As such, treated patients are no longer infectious.

Symptoms and Clinical Manifestations

Only one third of infected patients develop overt symptoms 25 . Symptoms range from asymptomatic to severely disabling. The severity of symptoms and the course of the disease are determined by the extent and duration of the exposure to infective mosquito bites, the quantity of accumulating adult worm antigen in the lymphatics, the host immune response, and the number of secondary bacterial and fungal infections.

Acute disease

Acute disease is caused by spontaneous or drug-induced death of adult filariae, with filarial fever, chills, acute lymphadenopathy (with retrograde lymphangitis, mainly the inguinal lymph nodes), myalgia and tropical pulmonary eosinophilia with microfilariae trapped in the lungs characterized by nocturnal wheezing 26 . In general, the recurrent acute inflammation occurs once, twice or five times a year and resolves after few days to one week depending on severity 27 28 29 .

Chronic disease

Local symptoms (pitting lymphedema, hydrocele) are the prominent signs of chronic infection within the skin and the surrounding tissues, especially the lower extremities 30 . The mechanism might be partially explained by bacterial superinfection (e. g., interdigital microtrauma), and once the lymphatic vessels are damaged, lymphedema may progress even in the absence of filarial infection 31 . In Brugian filariasis ulcerating abscess formation may occur along the involved lymphatics including the genitalia. Many organs can be involved, including the scrotum (scrotal lymphangiectasia, hydrocele up to 30 cm, epididymitis and rarely orchitis), urogenital and renal manifestations 32 33 34 with chyluria (intestinal lymph may be intermittently discharged into the renal pelvis 35 , ovary and inner genital 36 , eyes and heart. The hydrocele is a fluid collection between the parietal and visceral layers of the tunica vaginalis, surrounding the testis and spermatic cord. Progressive non-pitting lymphedema with limb swelling is related to chronic inflammation of the lymphatic vessels resulting in hyperpigmentation and hyperkeratosis and sometimes elephantiasis of the lower limbs. The breast can be involved in females.

Diagnosis

Confirming serological diagnosis

Blood eosinophilia is typical, sometimes exceeding 3/nL 26 and serves as screening in patients with typical symptoms. Diagnosis of LF can be best achieved by detecting circulating filarial antigen (CFA) of W. bancrofti -DNA in the blood 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 , detecting circulating microfilariae or by detecting adult worms in the lymphatics 44 . Examination of blood smears is a less sensitive but acceptable alternative in settings where antigen testing is not available. Blood tests have better sensitivity than biopsy and histological evaluation 45 46 . CFA is diagnostic in W. bancrofti only but false-positive W. bancrofti antigen testing may occur in patients with severe circulating Loa loa microfilariae 47 48 . Negative blood results have been observed in treated “burned out” infections 46 49 50 . Definitive diagnosis of filariasis requires blood smear examination for microfilariae or the presence of circulating filarial antigen. Serological testing may be helpful in appropriate clinical settings. Unless they use the single recombinant antigen Wb 123 (which is not commercially available) 51 , antifilarial serologic antibody tests do not differentiate between the various types of filarial infections and often show a cross-reaction with antigens from other diseases caused by helminths 52 . They do not allow differentiation between acute and chronic infection 53 . Species-specific polymerase chain reaction techniques have been used but they are not commercially available 54 55 . Examination of concentrated 56 blood smears using Giemsa or Wright stains (taken during the nocturnal activity period) for microfilariae is a second-line diagnostic tool if circulating antigen testing is not available or Brugian filariasis is suspected 57 58 . Morphologic characteristics on blood smear allow differentiation of the LF species. W. bancrofti and both Brugia species have an acellular staining sheath visible on light microscopy. W. bancrofti has no nuclei in its tail whereas B. malayi has terminal and subterminal nuclei in its tail.

Imaging diagnosis

Video 1

Video 2

Imaging in general and ultrasound specifically may demonstrate the parasites’ respective complications 59 60 61 62 63 . Damaging conventional X-ray contrast lymphangiography has been replaced by scintigraphy 33 .

X-ray lymphangiograms made in patients with filarial lymphedema show a typical pattern of varicosities which clearly differentiate this condition from lymphostatic verrucosis, the prevalent form of non-filarial lymphedema 64 . Also, lymphography was useful in the treatment of chyluria 65 . Contrast lymphangiography, while widely used to visualize the morphology of the lymphatic vessels 66 , carries the potential risk of lymphatic damage. The unpredictable consequences of such studies have hampered the early evaluation of the lymphatics of asymptomatic individuals 67 . To overcome these difficulties, lymphoscintigraphy using radiolabeled albumin or dextran has been developed 68 . This technique can be performed and repeated safely so that serial studies of individuals are possible. Preliminary studies with this technique have demonstrated the presence of lymphatic abnormalities in asymptomatic microfilaremics with no evidence of edema. Lymphoscintigraphy allows clear and precise analysis of lymphatic system function in patients at risk. This technique could be used for the examination of infected but asymptomatic individuals to determine whether they have morphological or functional lymphatic abnormalities and how these alterations could be changed, especially by chemotherapy. It could also provide a new epidemiological tool for detailed studies of morbidity due to endemic filariasis.

Ultrasound allows the detection of moving adult worms in lymphatic vessels (“filarial dance sign”) and also monitoring of the effectiveness of treatment 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 ( Video 1 ). Pulsating blood vessels can be differentiated from irregular moving worms containing lymphatics by Doppler ultrasound 78 79 80 81 ( Video 2 ). The “filarial dance sign” has been observed in many organs including the limbs 71 80 Fig. 1 , scrotum 69 70 72 73 74 82 83 84 Fig. 2 and Fig. 3 , breast and axillary lymphatics 75 78 85 86 Fig. 4 and Fig. 5 or cord Fig. 6 . The role of different ultrasound techniques in evaluating lymphatic disease has been extensively described 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 . The role of contrast-enhanced ultrasound 88 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 and elastography 99 100 101 103 104 105 106 in the evaluation of filariasis has not yet been described. Both methods might be helpful in identifying fibrosis and scars. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound can also be used to evaluate the lymphatic tissue directly 107 108 .

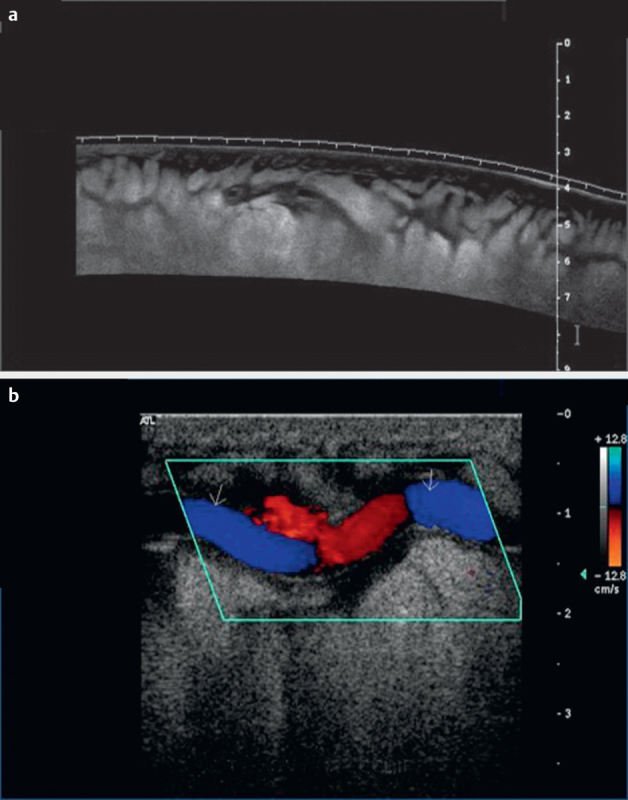

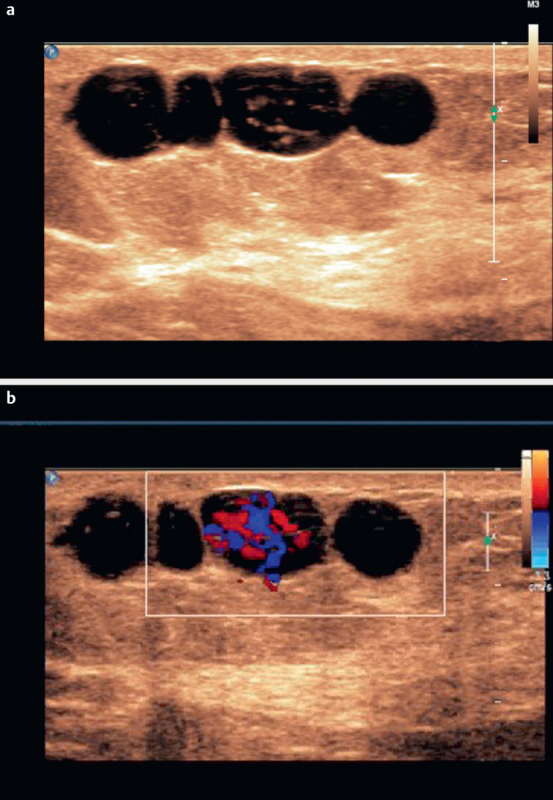

Fig. 1.

Leg filariasis, B-mode imaging of leg filariasis a , color Doppler imaging of leg filariasis b in a patient with subcutaneous thickening.

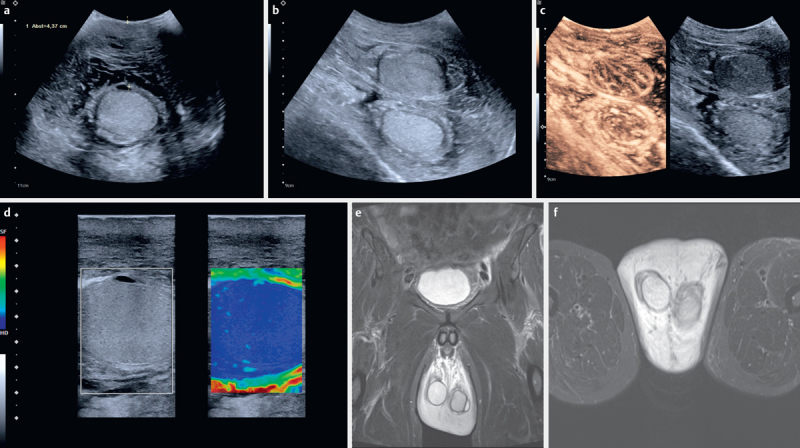

Fig. 2.

60-year-old patient from Guatemala, Latin America with recurrent scrotal swelling with thickness of the pure scrotum without testis of > 40 mm a and b , the swelling is indicated between markers) on both sides b . A hydrocele was operated on a few years ago. Treatment with mebendazole has been reported during that time. The “filarial dance sign” could be seen on real-time ultrasound below the testis. The testes showed increased stiffness using elastography c and little contrast enhancement on contrast-enhanced ultrasound d , indicating chronic orchitis. MRI images (T2, koronar) are also shown e , f .

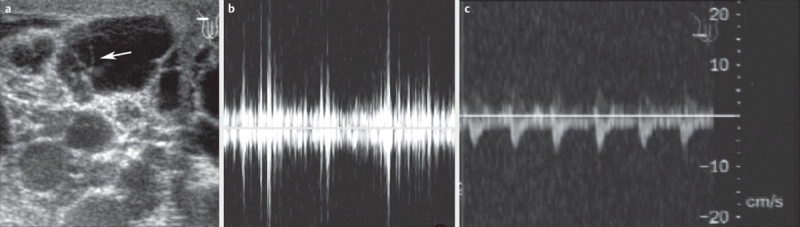

Fig. 3.

Ultrasound of enlarged lymph vessels in the scrotal area; in the left part of the biggest vessel, a moving worm can be detected a . On pulse wave Doppler, the movements appear as irregular amplitudes b and can be differentiated from pulsating vessels c .

Fig. 4.

Lymph scrotum with thickened skin a . Thickness can be measured by ultrasound b .

Fig. 5.

Breast filariasis. B-mode imaging a and color Doppler imaging of breast filariasis b . Irregular amplitudes of color signals could be used to make a differential diagnosis.

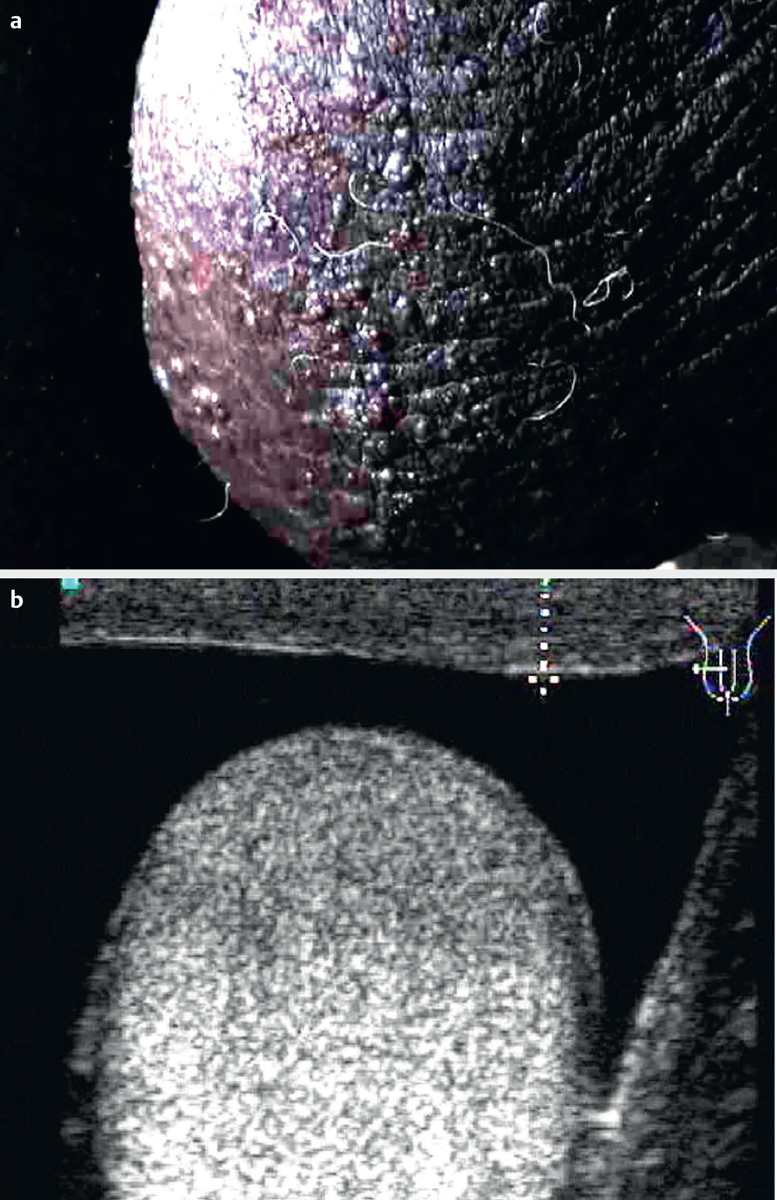

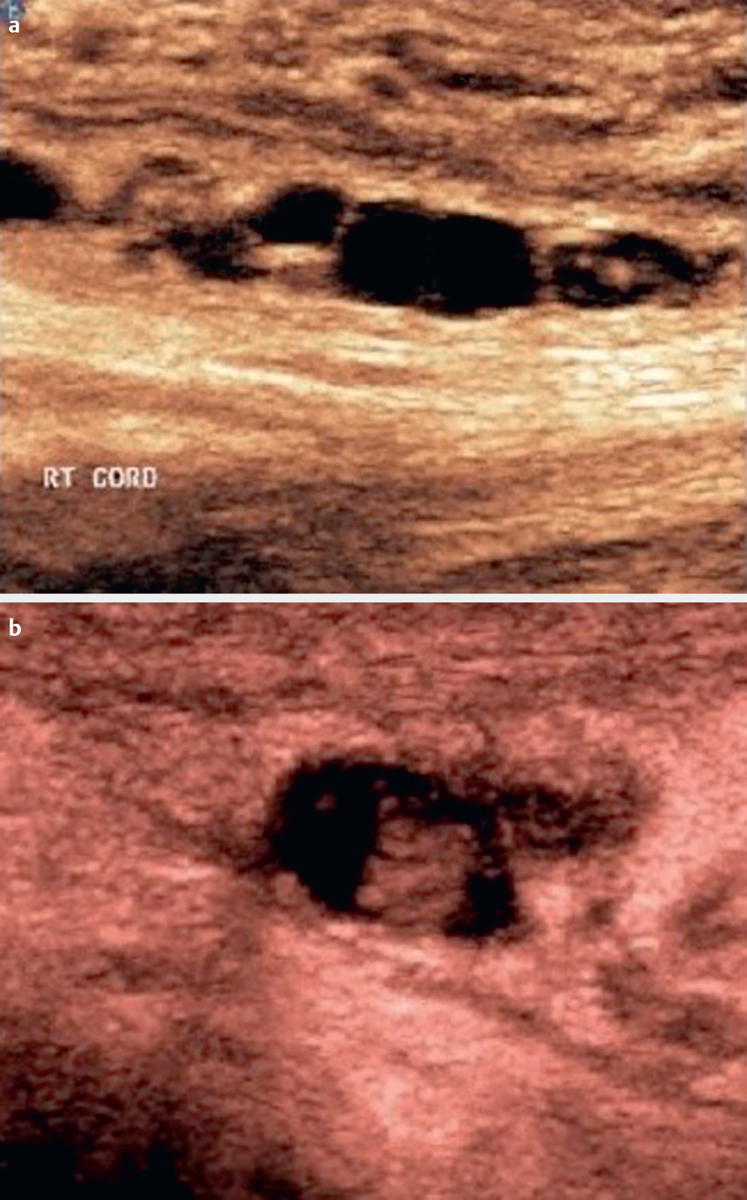

Fig. 6.

Cord filariasis, grayscale imaging of cord filariasis a , detailed view of small adult worms b .

Almost no helpful and specific experience has been published about CT 109 110 111 and MRI 112 113 114 115 findings in filariasis also due to the small size of the parasites.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of LF with retrograde lymphedema includes primary lymphedema, progressive cellulitis, neoplastic diseases (e. g., cancer) and a variety of inflammatory diseases (e. g., antegrade bacterial lymphangitis, tuberculosis), as well as loiasis, onchocerciasis, podoconiosis (abnormal inflammatory reaction to mineral particles in altitudes higher than mosquito transmission zones for filariasis (above 1 500 m)) 116 . Loiasis and onchocerciasis are rarely associated with lymphedema.

The filarial nematode L. loa causes loiasis. The diagnosis is established by identifying the migrating adult worm in the subcutaneous tissue swelling (calabar) of the distal limbs and during the subconjunctival migration of the worm around the orbita or by detecting microfilariae in a blood smear 47 117 118 . False-positive antigen tests for W. bancrofti in the setting of L. loa microfilaremia may complicate the diagnosis of occult W. bancrofti in coinfected patients.

The filarial nematode Onchocerca volvulus causes onchocerciasis. The clinical manifestations include skin and eye involvement and systemic manifestations. The so-called “hanging groin” is a result of skin atrophy of the groin and anterior thigh. Chains of (scary) lymph nodes result in folds of loose skin.

Treatment

Early treatment is recommended also in asymptomatic patients to prevent lymphatic disease. In patients with advanced disease with scars and fibrotic tissue, treatment success is less obvious. The treatment of local and systemic secondary bacterial infections is mandatory and includes regular antibiotics and prophylactic antibiotics in some cases and the use of antibacterial creams on damaged skin and small erosions. Careful attention to hygiene including regular nail cleaning, wearing of shoes, washing of affected areas daily, etc. is important. The affected limb(s) should be regularly exercised and if necessary lymph flow should be enhanced by complex decongestive therapy (CDT). Elevation of the affected limb during the night is recommended after the exclusion of arterial occlusive disease.

The standard treatment of choice in monoinfection of Wucheria bancrofti , Brugia malayi , and Brugia timori is diethylcarbamazine (DEC, 6–10 mg/kg for up to 2 (3) weeks) 1 119 120 121 . The dosage and mechanism of action depend on the species 122 123 124 . DEC is not recommended in pregnancy.

Patients with proven or suspected coinfection of LF and onchocerciasis without ocular involvement should undergo treatment of onchocerciasis first. LF pre-treatment in the form of ivermectin 150 μg/kg in a single dose should be given to reduce the microfilarial load 124 125 126 127 128 129 . Ivermectin can be followed by the abovementioned standard treatment for LF, DEC after one month or later 130 131 . Doxycycline (200 mg orally once daily for four to six weeks) followed by ivermectin (150 μg/kg orally single dose) can be used as an alternative to the standard treatment 132 . It is macrofilaricidal, i. e. it kills the adult worms and constitutes a curative therapy.

Albendazole shows at least partial macrofilaricidal activity against adult worms and has been effective and safe in patients with concomitant loiasis or onchocerciasis 133 134 . Complex lymphatic decongestive physiotherapy should accompany drug treatment.

Surgical drainage of hydroceles may give immediate relief but recurrence may occur 19 .

The reproductive lifespan of adult parasites has been estimated to be 4–6 years, explaining the effectiveness of mass treatment programs (Global Program for the Elimination of LF) 121 135 136 137 138 . Such programs have suppressed transmission to<1 percent. W. bancrofti has no animal hosts and might be the best target for elimination. Other filariases, e. g., Brugian, have a domestic and wild animal reservoir and elimination does not seem feasible. Triple-drug single dose treatment with ivermectin, diethylcarbamazine, and albendazole has been successful in endemic areas 139 140 .

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Dietrich C F, Lorentzen T, Appelbaum L, Buscarini E, Cantisani V, Correas J M, Cui X W et al. EFSUMB Guidelines on Interventional Ultrasound (INVUS), Part III - Abdominal Treatment Procedures (Long Version) Ultraschall Med. 2016;37:E1–E32.. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1553917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dietrich C F, Lorentzen T, Appelbaum L, Buscarini E, Cantisani V, Correas J M, Cui X W et al. EFSUMB Guidelines on Interventional Ultrasound (INVUS), Part III - Abdominal Treatment Procedures (Short Version) Ultraschall Med. 2016;37:27–45. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1553965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dietrich C F, Mueller G, Beyer-Enke S. Cysts in the cyst pattern. Z Gastroenterol. 2009;47:1203–1207. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1109385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rhomberg F. [Therapy of filariasis] Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1969;94:1457. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1110281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brunetti E, Tamarozzi F, Macpherson C, Filice C, Piontek M S, Kabaalioglu A, Dong Y et al. Ultrasound and cystic echinococcosis. Ultrasound Int Open. 2018;4:E70–E78. doi: 10.1055/a-0650-3807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richter J, Azoulay D, Dong Y, Holtfreter M C, Akpata R, Calderaro J, El-Scheich T et al. Ultrasonography of gallbladder abnormalities due to schistosomiasis. Parasitol Res. 2016;115:2917–2924. doi: 10.1007/s00436-016-5116-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richter J, Botelho M C, Holtfreter M C, Akpata R, El Scheich T, Neumayr A, Brunetti E et al. Ultrasound assessment of schistosomiasis. Z Gastroenterol. 2016;54:653–660. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-107359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dietrich C F, Kabaalioglu A, Brunetti E, Richter J. Fasciolosis. Z Gastroenterol. 2015;53:285–290. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1385728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dietrich C F, Sharma M, Chaubal N, Dong Y, Cui X W, Schindler-Piontek M, Richter J et al. Ascariasis imaging: Pictorial essay. Z Gastroenterol. 2017;55:479–489. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-104781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christmann M, Henrich R, Mayer G, Ell C. [Infection with fasciola hepatica causing elevated liver-enzyme results and eosinophilia – serologic and endoscopic diagnosis and therapy] Z Gastroenterol. 2002;40:801–806. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-33877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dietrich C F, Lembcke B, Jenssen C, Hocke M, Ignee A, Hollerweger A. Intestinal ultrasound in rare gastrointestinal diseases, update, part 1. Ultraschall Med. 2014;35:400–421. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1385154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dietrich C F, Lembcke B, Jenssen C, Hocke M, Ignee A, Hollerweger A. Intestinal ultrasound in rare gastrointestinal diseases, Update, Part 2. Ultraschall Med. 2015;36:428–456. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1399730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramaiah K D, Ottesen E A. Progress and impact of 13 years of the global programme to eliminate lymphatic filariasis on reducing the burden of filarial disease. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e3319. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Witt C, Ottesen E A. Lymphatic filariasis: An infection of childhood. Trop Med Int Health. 2001;6:582–606. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2001.00765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malhotra I, Mungai P L, Wamachi A N, Tisch D, Kioko J M, Ouma J H, Muchiri E et al. Prenatal T cell immunity to Wuchereria bancrofti and its effect on filarial immunity and infection susceptibility during childhood. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:1005–1013. doi: 10.1086/500472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ottesen E A.The Wellcome Trust Lecture. Infection and disease in lymphatic filariasis: An immunological perspective Parasitology 1992104SupplS71–S79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bennuru S, Nutman T B. Lymphatics in human lymphatic filariasis: In vitro models of parasite-induced lymphatic remodeling. Lymphat Res Biol. 2009;7:215–219. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2009.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grobusch M P, Kombila M, Autenrieth I, Mehlhorn H, Kremsner P G. No evidence of Wolbachia endosymbiosis with Loa loa and Mansonella perstans. Parasitol Res. 2003;90:405–408. doi: 10.1007/s00436-003-0872-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor M J, Hoerauf A. Wolbachia bacteria of filarial nematodes. Parasitol Today. 1999;15:437–442. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(99)01533-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Punkosdy G A, Addiss D G, Lammie P J. Characterization of antibody responses to Wolbachia surface protein in humans with lymphatic filariasis. Infect Immun. 2003;71:5104–5114. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.9.5104-5114.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor M J. Wolbachia in the inflammatory pathogenesis of human filariasis. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2003;990:444–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor M J, Cross H F, Ford L, Makunde W H, Prasad G B, Bilo K. Wolbachia bacteria in filarial immunity and disease. Parasite Immunol. 2001;23:401–409. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.2001.00400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor M J. A new insight into the pathogenesis of filarial disease. Curr Mol Med. 2002;2:299–302. doi: 10.2174/1566524024605662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lammie P J, Cuenco K T, Punkosdy G A.The pathogenesis of filarial lymphedema: Is it the worm or is it the host? Ann NY Acad Sci 2002979131–142.discussion 188-196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nutman T B, Kazura J, Guerrant R, Walker D H, Weller P F.Lymphatic FilariasisInedsTropical Infectious Diseases: Principles, Pathogens and Practice3rd edPhiladelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ottesen E A, Weller P F. Eosinophilia following treatment of patients with schistosomiasis mansoni and Bancroft’s filariasis. J Infect Dis. 1979;139:343–347. doi: 10.1093/infdis/139.3.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pani S P, Srividya A. Clinical manifestations of bancroftian filariasis with special reference to lymphoedema grading. Indian J Med Res. 1995;102:114–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pani S P, Yuvaraj J, Vanamail P, Dhanda V, Michael E, Grenfell B T, Bundy D A. Episodic adenolymphangitis and lymphoedema in patients with bancroftian filariasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1995;89:72–74. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(95)90666-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dreyer G, Medeiros Z, Netto M J, Leal N C, de Castro L G, Piessens W F. Acute attacks in the extremities of persons living in an area endemic for bancroftian filariasis: Differentiation of two syndromes. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1999;93:413–417. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(99)90140-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McPherson T, Persaud S, Singh S, Fay M P, Addiss D, Nutman T B, Hay R. Interdigital lesions and frequency of acute dermatolymphangioadenitis in lymphoedema in a filariasis-endemic area. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:933–941. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.07081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mand S, Debrah A Y, Klarmann U, Batsa L, Marfo-Debrekyei Y, Kwarteng A, Specht S et al. Doxycycline improves filarial lymphedema independent of active filarial infection: A randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:621–630. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Supali T, Wibowo H, Ruckert P, Fischer K, Ismid I S, Djuardi Y.Purnomoet al. High prevalence of Brugia timori infection in the highland of Alor Island, Indonesia Am J Trop Med Hyg 200266560–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freedman D O, de Almeida Filho P J, Besh S, Maia e Silva M C, Braga C, Maciel A. Lymphoscintigraphic analysis of lymphatic abnormalities in symptomatic and asymptomatic human filariasis. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:927–933. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.4.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dreyer G, Ottesen E A, Galdino E, Andrade L, Rocha A, Medeiros Z, Moura I et al. Renal abnormalities in microfilaremic patients with Bancroftian filariasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;46:745–751. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.46.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Franco-Paredes C, Hidron A, Steinberg J. A woman from British Guyana with recurrent back pain and fever. Chyluria associated with infection due to Wuchereria bancrofti. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:1340–1291. doi: 10.1086/503263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sethi S, Misra K, Singh U R, Kumar D. Lymphatic filariasis of the ovary and mesosalpinx. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2001;27:285–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2001.tb01271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chandrasena T G, Premaratna R, Abeyewickrema W, de Silva N R. Evaluation of the ICT whole-blood antigen card test to detect infection due to Wuchereria bancrofti in Sri Lanka. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2002;96:60–63. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(02)90241-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chanteau S, Moulia-Pelat J P, Glaziou P, Nguyen N L, Luquiaud P, Plichart C, Martin P M et al. Og4C3 circulating antigen: A marker of infection and adult worm burden in Wuchereria bancrofti filariasis. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:247–250. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.1.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chesnais C B, Missamou F, Pion S D, Bopda J, Louya F, Majewski A C, Weil G J et al. Semi-quantitative scoring of an immunochromatographic test for circulating filarial antigen. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89:916–918. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rocha A, Addiss D, Ribeiro M E, Noroes J, Baliza M, Medeiros Z, Dreyer G. Evaluation of the Og4C3 ELISA in Wuchereria bancrofti infection: Infected persons with undetectable or ultra-low microfilarial densities. Trop Med Int Health. 1996;1:859–864. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.1996.tb00123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turner P, Copeman B, Gerisi D, Speare R. A comparison of the Og4C3 antigen capture ELISA, the Knott test, an IgG4 assay and clinical signs, in the diagnosis of Bancroftian filariasis. Trop Med Parasitol. 1993;44:45–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weil G J, Curtis K C, Fakoli L, Fischer K, Gankpala L, Lammie P J, Majewski A C et al. Laboratory and field evaluation of a new rapid test for detecting Wuchereria bancrofti antigen in human blood. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89:11–15. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weil G J, Ramzy R M. Diagnostic tools for filariasis elimination programs. Trends Parasitol. 2007;23:78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumar B, Karki S, Yadava S K. Role of fine needle aspiration cytology in diagnosis of filarial infestation. Diagn Cytopathol. 2011;39:8–12. doi: 10.1002/dc.21314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weil G J, Jain D C, Santhanam S, Malhotra A, Kumar H, Sethumadhavan K V, Liftis F et al. A monoclonal antibody-based enzyme immunoassay for detecting parasite antigenemia in bancroftian filariasis. J Infect Dis. 1987;156:350–355. doi: 10.1093/infdis/156.2.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nicolas L, Plichart C, Nguyen L N, Moulia-Pelat J P. Reduction of Wuchereria bancrofti adult worm circulating antigen after annual treatments of diethylcarbamazine combined with ivermectin in French Polynesia. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:489–492. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.2.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bakajika D K, Nigo M M, Lotsima J P, Masikini G A, Fischer K, Lloyd M M, Weil G J et al. Filarial antigenemia and Loa loa night blood microfilaremia in an area without bancroftian filariasis in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;91:1142–1148. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pion S D, Montavon C, Chesnais C B, Kamgno J, Wanji S, Klion A D, Nutman T B et al. Positivity of antigen tests used for diagnosis of lymphatic filariasis in individuals without wuchereria bancrofti infection but with high loa loa microfilaremia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;95:1417–1423. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McCarthy J S, Guinea A, Weil G J, Ottesen E A. Clearance of circulating filarial antigen as a measure of the macrofilaricidal activity of diethylcarbamazine in Wuchereria bancrofti infection. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:521–526. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.2.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weil G J, Lammie P J, Richards F O, Jr., Eberhard M L. Changes in circulating parasite antigen levels after treatment of bancroftian filariasis with diethylcarbamazine and ivermectin. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:814–816. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.4.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Steel C, Golden A, Kubofcik J, LaRue N, de Los Santos T, Domingo G J, Nutman T B. Rapid Wuchereria bancrofti-specific antigen Wb123-based IgG4 immunoassays as tools for surveillance following mass drug administration programs on lymphatic filariasis. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2013;20:1155–1161. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00252-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lammie P J, Weil G, Noordin R, Kaliraj P, Steel C, Goodman D, Lakshmikanthan V B et al. Recombinant antigen-based antibody assays for the diagnosis and surveillance of lymphatic filariasis – A multicenter trial. Filaria J. 2004;3:9. doi: 10.1186/1475-2883-3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kubofcik J, Fink D L, Nutman T B. Identification of Wb123 as an early and specific marker of Wuchereria bancrofti infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1930. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lucena W A, Dhalia R, Abath F G, Nicolas L, Regis L N, Furtado A F. Diagnosis of Wuchereria bancrofti infection by the polymerase chain reaction using urine and day blood samples from amicrofilaraemic patients. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1998;92:290–293. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(98)91016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ramzy R M, Farid H A, Kamal I H, Ibrahim G H, Morsy Z S, Faris R, Weil G J et al. A polymerase chain reaction-based assay for detection of Wuchereria bancrofti in human blood and Culex pipiens. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997;91:156–160. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(97)90205-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dissanayake S, Rocha A, Noroes J, Medeiros Z, Dreyer G, Piessens W F. Evaluation of PCR-based methods for the diagnosis of infection in bancroftian filariasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000;94:526–530. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(00)90075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weller P F, Ottesen E A, Heck L, Tere T, Neva F A. Endemic filariasis on a Pacific island. I. Clinical, epidemiologic, and parasitologic aspects. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1982;31:942–952. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1982.31.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mak J W, Cheong W H, Yen P K, Lim P K, Chan W C. Studies on the epidemiology of subperiodic Brugia malayi in Malaysia: Problems in its control. Acta Trop. 1982;39:237–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dreyer G, Figueredo-Silva J, Carvalho K, Amaral F, Ottesen E A. Lymphatic filariasis in children: Adenopathy and its evolution in two young girls. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;65:204–207. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.65.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Estran C, Marty P, Blanc V, Faure O, Leccia M T, Pelloux H, Diebolt E et al. [Human dirofilariasis: 3 cases in the south of France] Presse Med. 2007;36:799–803. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2006.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Aguiar-Santos A M, Leal-Cruz M, Netto M J, Carrera A, Lima G, Rocha A. Lymph scrotum: An unusual urological presentation of lymphatic filariasis. A case series study. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2009;51:179–183. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652009000400001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rocha A, Braga C, Belem M, Carrera A, Aguiar-Santos A, Oliveira P, Texeira M J et al. Comparison of tests for the detection of circulating filarial antigen (Og4C3-ELISA and AD12-ICT) and ultrasound in diagnosis of lymphatic filariasis in individuals with microfilariae. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104:621–625. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762009000400015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ilyasov B, Kartashev V, Bastrikov N, Madjugina L, Gonzalez-Miguel J, Morchon R, Simon F. Thirty cases of human subcutaneous dirofilariasis reported in Rostov-on-Don (Southwestern Russian Federation) Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2015;33:233–237. doi: 10.1016/j.eimc.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cohen L B, Nelson G, Wood A M, Manson-Bahr P E, Bowen R. Lymphangiography in filarial lymphoedema and elephantiasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1961;10:843–848. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1961.10.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gandhi G M. Role of lymphography in management of filarial chyluria. Lymphology. 1976;9:11–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dustmann H O. [Diagnosis, differential diagnosis and therapy of lymphedema] Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1982;120:76–82. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1051580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lymphatic filariasis: Siagnosis and pathogenesis . WHO expert committee on filariasis. Bull World Health Organ. 1993;71:135–141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shelley S, Manokaran G, Indirani M, Gokhale S, Anirudhan N. Lymphoscintigraphy as a diagnostic tool in patients with lymphedema of filarial origin–an Indian study. Lymphology. 2006;39:69–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Amaral F, Dreyer G, Figueredo-Silva J, Noroes J, Cavalcanti A, Samico S C, Santos A et al. Live adult worms detected by ultrasonography in human Bancroftian filariasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;50:753–757. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.50.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Noroes J, Addiss D, Amaral F, Coutinho A, Medeiros Z, Dreyer G. Occurrence of living adult Wuchereria bancrofti in the scrotal area of men with microfilaraemia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1996;90:55–56. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(96)90478-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dreyer G, Noroes J, Addiss D, Santos A, Medeiros Z, Figueredo-Silva J. Bancroftian filariasis in a paediatric population: An ultrasonographic study. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1999;93:633–636. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(99)90078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Simonsen P E, Bernhard P, Jaoko W G, Meyrowitsch D W, Malecela-Lazaro M N, Magnussen P, Michael E. Filaria dance sign and subclinical hydrocoele in two east African communities with bancroftian filariasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2002;96:649–653. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(02)90342-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chaubal N G, Pradhan G M, Chaubal J N, Ramani S K.Dance of live adult filarial worms is a reliable sign of scrotal filarial infection J Ultrasound Med 200322765–769.quiz 770-762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shetty G S, Solanki R S, Prabhu S M, Jawa A. Filarial dance–sonographic sign of filarial infection. Pediatr Radiol. 2012;42:486–487. doi: 10.1007/s00247-011-2190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bayramoglu Z, Yilmaz R, Gocmez A, Salmaslioglu A, Acunas G. Filarial dance in the axillary lymph node. Breast J. 2017;23:474–475. doi: 10.1111/tbj.12768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dreyer G, Noroes J, Amaral F, Nen A, Medeiros Z, Coutinho A, Addiss D. Direct assessment of the adulticidal efficacy of a single dose of ivermectin in bancroftian filariasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1995;89:441–443. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(95)90049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Noroes J, Dreyer G, Santos A, Mendes V G, Medeiros Z, Addiss D. Assessment of the efficacy of diethylcarbamazine on adult Wuchereria bancrofti in vivo. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997;91:78–81. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(97)90405-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mand S, Debrah A, Batsa L, Adjei O, Hoerauf A. Reliable and frequent detection of adult Wuchereria bancrofti in Ghanaian women by ultrasonography. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9:1111–1114. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shenoy R K, Suma T K, Kumaraswami V, Padma S, Rahmah N, Abhilash G, Ramesh C. Doppler ultrasonography reveals adult-worm nests in the lymph vessels of children with brugian filariasis. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2007;101:173–180. doi: 10.1179/136485907X154566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shenoy R K, Suma T K, Kumaraswami V, Rahmah N, Dhananjayan G, Padma S, Abhilash G et al. Preliminary findings from a cross-sectional study on lymphatic filariasis in children, in an area of India endemic for Brugia malayi infection. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2007;101:205–213. doi: 10.1179/136485907X154548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mand S, Marfo-Debrekyei Y, Dittrich M, Fischer K, Adjei O, Hoerauf A. Animated documentation of the filaria dance sign (FDS) in bancroftian filariasis. Filaria J. 2003;2:3. doi: 10.1186/1475-2883-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shenoy R K, John A, Hameed S, Suma T K, Kumaraswami V. Apparent failure of ultrasonography to detect adult worms of Brugia malayi. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2000;94:77–82. doi: 10.1080/00034980057635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Reddy G S, Das L K, Pani S P. The preferential site of adult Wuchereria bancrofti: An ultrasound study of male asymptomatic microfilaria carriers in Pondicherry, India. Natl Med J India. 2004;17:195–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mand S, Debrah A Y, Klarmann U, Mante S, Kwarteng A, Batsa L, Marfo-Debrekyei Yet al. The role of ultrasonography in the differentiation of the various types of filaricele due to bancroftian filariasis Acta Trop 2011120Suppl 1S23–S32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dreyer G, Brandao A C, Amaral F, Medeiros Z, Addiss D. Detection by ultrasound of living adult Wuchereria bancrofti in the female breast. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1996;91:95–96. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761996000100016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Patil J A, Patil A D, Ramani S K. Filarial “dance” in breast mass. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:1157–1158. doi: 10.2214/ajr.181.4.1811157a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hocke M, Ignee A, Dietrich C. Role of contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound in lymph nodes. Endosc Ultrasound. 2017;6:4–11. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.190929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chiorean L, Cui X W, Klein S A, Budjan J, Sparchez Z, Radzina M, Jenssen C et al. Clinical value of imaging for lymph nodes evaluation with particular emphasis on ultrasonography. Z Gastroenterol. 2016;54:774–790. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-108656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dietrich C F. Contrast-enhanced endobronchial ultrasound: Potential value of a new method. Endosc Ultrasound. 2017;6:43–48. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.200215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ignee A, Atkinson N S, Schuessler G, Dietrich C F. Ultrasound contrast agents. Endosc Ultrasound. 2016;5:355–362. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.193594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jenssen C, Annema J T, Clementsen P. Ultrasound techniques in the evaluation of the mediastinum, part 2: Mediastinal lymph node anatomy and diagnostic reach of ultrasound techniques, clinical work up of neoplastic and inflammatory mediastinal lymphadenopathy using ultrasound techniques and how to learn mediastinal endosonography. J Thorac Dis. 2016;7:E439. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.10.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dietrich C F, Jenssen C, Herth F J. Endobronchial ultrasound elastography. Endosc Ultrasound. 2016;5:233–238. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.187866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dietrich C F, Annema J T, Clementsen P, Cui X W, Borst M M, Jenssen C. Ultrasound techniques in the evaluation of the mediastinum, part I: Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) and transcutaneous mediastinal ultrasound (TMUS), introduction into ultrasound techniques. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7:E311–E325. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.09.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Schreiber-Dietrich D, Pohl M, Cui X W, Braden B, Dietrich C F, Chiorean L. Perihepatic lymphadenopathy in children with chronic viral hepatitis. J Ultrason. 2015;15:137–150. doi: 10.15557/JoU.2015.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cui X W, Hocke M, Jenssen C, Ignee A, Klein S, Schreiber-Dietrich D, Dietrich C F. Conventional ultrasound for lymph node evaluation, update 2013. Z Gastroenterol. 2014;52:212–221. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1356153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dietrich C F, Averkiou M, Nielsen M B, Barr R G, Burns P N, Calliada F, Cantisani V et al. How to perform Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound (CEUS) Ultrasound Int Open. 2018;4:E2–E15. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-123931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sidhu P S, Cantisani V, Deganello A, Dietrich C F, Duran C, Franke D, Harkanyi Z et al. Role of Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound (CEUS) in Paediatric Practice: An EFSUMB Position Statement. Ultraschall Med. 2017;38:33–43. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-110394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Trimboli P, Dietrich C F, David E, Mastroeni G, Ventura Spagnolo O, Sidhu P S, Letizia C et al. Ultrasound and ultrasound-related techniques in endocrine diseases. Minerva Endocrinol. 2018;43:333–340. doi: 10.23736/S0391-1977.17.02728-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Dietrich C F, Rudd L, Saftiou A, Gilja O H. The EFSUMB website, a great source for ultrasound information and education. Med Ultrason. 2017;19:102–110. doi: 10.11152/mu-938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Dong Y, D’Onofrio M, Hocke M, Jenssen C, Potthoff A, Atkinson N, Ignee A et al. Autoimmune pancreatitis: Imaging features. Endosc Ultrasound. 2018;7:196–203. doi: 10.4103/eus.eus_23_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Dong Y, Jurgensen C, Puri R, D’Onofrio M, Hocke M, Wang W P, Atkinson N et al. Ultrasound imaging features of isolated pancreatic tuberculosis. Endosc Ultrasound. 2017;7:119–127. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.210901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Dietrich C F, Greis C. [How to perform contrast enhanced ultrasound] Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2016;141:1019–1024. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-107959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Barr R G, Cosgrove D, Brock M, Cantisani V, Correas J M, Postema A W, Salomon G et al. WFUMB guidelines and recommendations on the clinical use of ultrasound elastography: Part 5. Prostate. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2017;43:27–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2016.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cosgrove D, Barr R, Bojunga J, Cantisani V, Chammas M C, Dighe M, Vinayak S et al. WFUMB guidelines and recommendations on the clinical use of ultrasound elastography: Part 4. Thyroid. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2017;43:4–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2016.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hocke M, Braden B, Jenssen C, Dietrich C F. Present status and perspectives of endosonography 2017 in gastroenterology. Korean J Intern Med. 2018;33:36–63. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2017.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Berzigotti A, Ferraioli G, Bota S, Gilja O H, Dietrich C F. Novel ultrasound-based methods to assess liver disease: The game has just begun. Dig Liver Dis. 2018;50:107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2017.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Dietrich C F, Ponnudurai R, Bachmann Nielsen M. [Is there a need for new imaging methods for lymph node evaluation?] Ultraschall Med. 2012;33:411–414. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1325384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Cui X W, Ignee A, Bachmann Nielsen M, Schreiber-Dietrich D, Demolo C, Pirri C, Jedrejczyk M et al. Contrast enhanced ultrasound of sentinel lymph nodes. Journal of Ultrasonography. 2013;13:73–81. doi: 10.15557/JoU.2013.0006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Jung J, Chang J, Oh S, Yoon J, Choi M. Computed tomography angiography for evaluation of pulmonary embolism in an experimental model and heartworm infested dogs. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2010;51:288–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2009.01659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Takahashi A, Yamada K, Kishimoto M, Shimizu J, Maeda R. Computed tomography (CT) observation of pulmonary emboli caused by long-term administration of ivermectin in dogs experimentally infected with heartworms. Vet Parasitol. 2008;155:242–248. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Oshiro Y, Murayama S, Sunagawa U, Nakamoto A, Owan I, Kuba M, Uehara T et al. Pulmonary dirofilariasis: Computed tomography findings and correlation with pathologic features. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2004;28:796–800. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200411000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Martin T N, Weir R A, Dargie H J. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of endomyocardial fibrosis secondary to Bancroftian filariasis. Heart. 2008;94:1116. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.140392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Shukla-Dave A, Degaonkar M, Roy R, Murthy P K, Murthy P S, Raghunathan P, Chatterjee R K. Metabolite mapping of human filarial parasite, Brugia malayi with nuclear magnetic resonance. Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;17:1503–1509. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(99)00091-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Blacksin M F, Lin S S, Trofa A F. Filariasis of the ankle: Magnetic resonance imaging. Foot Ankle Int. 1999;20:738–740. doi: 10.1177/107110079902001111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Shukla-Dave A, Fatma N, Roy R, Srivastava S, Chatterjee R K, Govindaraju V, Viswanathan A K et al. 1H magnetic resonance imaging and 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy in experimental filariasis. Magn Reson Imaging. 1997;15:1193–1198. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(97)00180-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Tekola Ayele F, Adeyemo A, Finan C, Hailu E, Sinnott P, Burlinson N D, Aseffa A et al. HLA class II locus and susceptibility to podoconiosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1200–1208. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wanji S, Amvongo-Adjia N, Koudou B, Njouendou A J, Chounna Ndongmo P W, Kengne-Ouafo J A, Datchoua-Poutcheu F R et al. Cross-reactivity of filariais ICT Cards in areas of contrasting endemicity of loa loa and mansonella perstans in cameroon: Implications for Shrinking of the lymphatic filariasis map in the central african region. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0004184. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wanji S, Amvongo-Adjia N, Njouendou A J, Kengne-Ouafo J A, Ndongmo W P, Fombad F F, Koudou B et al. Further evidence of the cross-reactivity of the Binax NOW(R) Filariasis ICT cards to non-Wuchereria bancrofti filariae: Experimental studies with Loa loa and Onchocerca ochengi. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:267. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1556-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Hoerauf A. Filariasis: New drugs and new opportunities for lymphatic filariasis and onchocerciasis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2008;21:673–681. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328315cde7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Moore T A, Reynolds J C, Kenney R T, Johnston W, Nutman T B. Diethylcarbamazine-induced reversal of early lymphatic dysfunction in a patient with bancroftian filariasis: Assessment with use of lymphoscintigraphy. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:1007–1011. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.5.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Tisch D J, Michael E, Kazura J W. Mass chemotherapy options to control lymphatic filariasis: A systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:514–523. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70192-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Frayha G J, Smyth J D, Gobert J G, Savel J. The mechanisms of action of antiprotozoal and anthelmintic drugs in man. Gen Pharmacol. 1997;28:273–299. doi: 10.1016/s0306-3623(96)00149-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Maizels R M, Bundy D A, Selkirk M E, Smith D F, Anderson R M. Immunological modulation and evasion by helminth parasites in human populations. Nature. 1993;365:797–805. doi: 10.1038/365797a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Klion A D, Ottesen E A, Nutman T B. Effectiveness of diethylcarbamazine in treating loiasis acquired by expatriate visitors to endemic regions: Long-term follow-up. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:604–610. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.3.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Addiss D G, Beach M J, Streit T G, Lutwick S, LeConte F H, Lafontant J G, Hightower A W et al. Randomised placebo-controlled comparison of ivermectin and albendazole alone and in combination for Wuchereria bancrofti microfilaraemia in Haitian children. Lancet. 1997;350:480–484. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)02231-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Cao W C, Van der Ploeg C P, Plaisier A P, van der Sluijs I J, Habbema J D. Ivermectin for the chemotherapy of bancroftian filariasis: A meta-analysis of the effect of single treatment. Trop Med Int Health. 1997;2:393–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.1997.tb00157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Chodakewitz J. Ivermectin and Lymphatic Filariasis: A clinical update. Parasitol Today. 1995;11:233. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Gardon J, Gardon-Wendel N, Demanga N, Kamgno J, Chippaux J P, Boussinesq M. Serious reactions after mass treatment of onchocerciasis with ivermectin in an area endemic for Loa loa infection. Lancet. 1997;350:18–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)11094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Ottesen E A, Vijayasekaran V, Kumaraswami V, Perumal Pillai S V, Sadanandam A, Frederick S, Prabhakar R et al. A controlled trial of ivermectin and diethylcarbamazine in lymphatic filariasis. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1113–1117. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199004193221604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Greene B M, Taylor H R, Cupp E W, Murphy R P, White A T, Aziz M A, Schulz-Key H et al. Comparison of ivermectin and diethylcarbamazine in the treatment of onchocerciasis. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:133–138. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198507183130301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Lariviere M, Vingtain P, Aziz M, Beauvais B, Weimann D, Derouin F, Ginoux J et al. Double-blind study of ivermectin and diethylcarbamazine in African onchocerciasis patients with ocular involvement. Lancet. 1985;2:174–177. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)91496-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Taylor M J, Hoerauf A, Bockarie M. Lymphatic filariasis and onchocerciasis. Lancet. 2010;376:1175–1185. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60586-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Dreyer G, Addiss D, Williamson J, Noroes J. Efficacy of co-administered diethylcarbamazine and albendazole against adult Wuchereria bancrofti. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2006;100:1118–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Gayen P, Nayak A, Saini P, Mukherjee N, Maitra S, Sarkar P, Sinha Babu S P. A double-blind controlled field trial of doxycycline and albendazole in combination for the treatment of bancroftian filariasis in India. Acta Trop. 2013;125:150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Hopkins D R. Disease eradication. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:54–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1200391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Kroidl I, Saathof E, Maganga L, Clowes P, Maboko L, Hoerauf A, Makunde W H et al. Prevalence of Lymphatic filariasis and treatment effectiveness of albendazole/ivermectin in individuals with HIV co-infection in Southwest-Tanzania. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004618. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Ottesen E A. Major progress toward eliminating lymphatic filariasis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1885–1886. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe020136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Thomas G, Richards F O, Jr., Eigege A, Dakum N K, Azzuwut M P, Sarki J, Gontor I et al. A pilot program of mass surgery weeks for treatment of hydrocele due to lymphatic filariasis in central Nigeria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80:447–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.489 Global programme to eliminate lymphatic filariasis: Progress report . 2014. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2015;90:489–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Thomsen E K, Sanuku N, Baea M, Satofan S, Maki E, Lombore B, Schmidt M S et al. Efficacy, Safety, and pharmacokinetics of coadministered diethylcarbamazine, albendazole, and ivermectin for treatment of bancroftian filariasis. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:334–341. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]