Abstract

Background

Coercive measures such as seclusion and restraint encroach on the patient’s human rights and can have serious adverse effects ranging from emotional trauma to physical injury and even death. At the same time, they may be the only way to avert acute danger for the patient and/or the hospital staff. In this article, we provide an overview of the efficacy of the measures that have been studied to date for the avoidance of coercion in psychiatry.

Methods

This review is based on publications retrieved by a systematic search in the Medline and Cinahl databases, supplemented by a search in the reference lists of these publications. We provide a narrative synthesis in which we categorize the interventions by content.

Results

Of the 84 studies included in this review, 16 had a control group; 6 of these 16 were randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The interventions were categorized by seven different types of content: organization, staff training, risk assessment, environment, psychotherapy, debriefings, and advance directives. Most interventions in each category were found to be effective in the respective studies. 38 studies investigated complex treatment programs that incorporated elements from more than one category; 37 of these (including one RCT) revealed effective reduction of the frequency of coercion. Two RCTs on the use of rating instruments to assess the risk of aggressive behavior revealed a relative reduction of the number of seclusion measures by 27% and a reduction of the cumulative duration of seclusion by 45%.

Conclusion

Complex intervention programs to avoid coercive measures, incorporating elements of more than one of the above categories, seem to be particularly effective. In future, cluster-randomized trials to investigate the individual categories of intervention would be desirable.

For the purposes of this article, the term “coercion” refers in particular to seclusion and restraint. This means tying down or physically restraining a patient. Seclusion means isolating a patient in a locked room (1). Rates of coercive measures vary between different countries, hospitals, and wards. Complete data on coercive measures were collected in Baden-Württemberg. In the first year in which data were collected (2016), 6.7% of patients treated in psychiatric hospitals were subject to coercion (e1). According to the Federal State Laws on the Care and Protection of the mentally ill (similar to the Mental Health Acts), psychiatric hospitals in Germany have sovereign duties. They are obliged to admit and keep patients with impaired decision-making capacity (for example, as a result of psychosis or intoxication) who constitute a danger to themselves or others against their will and treat them. The intention is to protect the patients themselves as well as external parties. A patient can be admitted to a psychiatric hospital as an inpatient only once this decision has been passed by a judge. The Federal Constitutional Court in its judgment of 24 July 2018 furthermore stipulated a requirement of judicial authority for restraining measures lasting 30 minutes or longer.

Coercion is a controversial subject. A conflict exists between maintaining the patient’s autonomy and the safety of those in charge of their care, their fellow patients, and the patients themselves. In some cases, coercive measures are the only way by which acute danger can be averted. But they can have severe consequences that range from mental trauma and physical injuries to death. The exact prevalence of complications of coercion is not known. After a young man had died in restraints in the US in the 1990s, a comprehensive investigation took place that identified a total of 142 deaths in restraint or seclusion over 10 years (2).

Coercion constitutes a violation of patients’ human rights and is experienced as such by patients (3). Patients who have experienced mechanical coercive measures have perceived these as antitherapeutic, punishing, humiliating, or traumatizing (3– 6). A study of the effects of coercive measures on patients showed that 47% of patients under study developed symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (e2). Self harm is also common in seclusion. Two recent case reports described patients who completed suicide during their seclusion (7). Two case series in older or physically weak patients reported a total of 13 cases of strangulation, suffocation, and sudden cardiac death during periods of restraint (8, 9). Similarly, a study that retrospectively investigated 110 cases of sudden cardiac death particularly in young adults described 34 cases in association with restraints. This study included cases of restraint by security staff, the police, or laypersons; nine of the deaths actually did have an association with restraint by psychiatric specialist personnel (10). Immobilization as a result of restraint is accompanied by risks of venous thromboembolism and infection, much in the same way as other forms of immobilization. An autopsy study that included three patients who had died while being restrained found pulmonary artery embolisms in all three; in all cases the restraint was maintained for as long as three to five days (11).

Methods

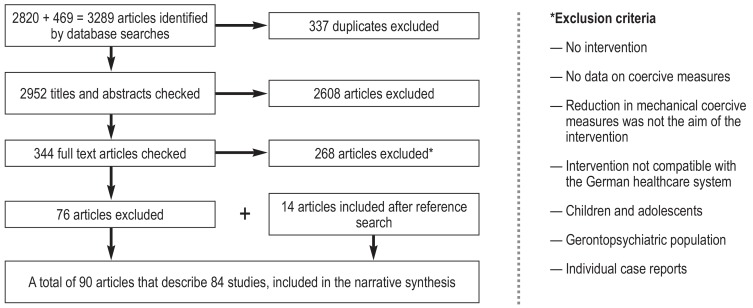

The databases Medline and Cinahl were searched up to April 2018. We included studies that investigated interventions to reduce coercive measures (seclusion and restraint [SR]) in adult patients with severe psychiatric disorders. Figure 1 shows the literature search and selection. This review was undertaken as part of the German clinical practice guidelines for the prevention of coercion and the prevention and treatment of aggressive behavior in the adult psychiatric setting (12, 13) and updated for this article. SH and EF screened the literature independently. Where disagreements arose, they jointly reviewed the article in question. The guideline report online includes a detailed description of the study methods (14).

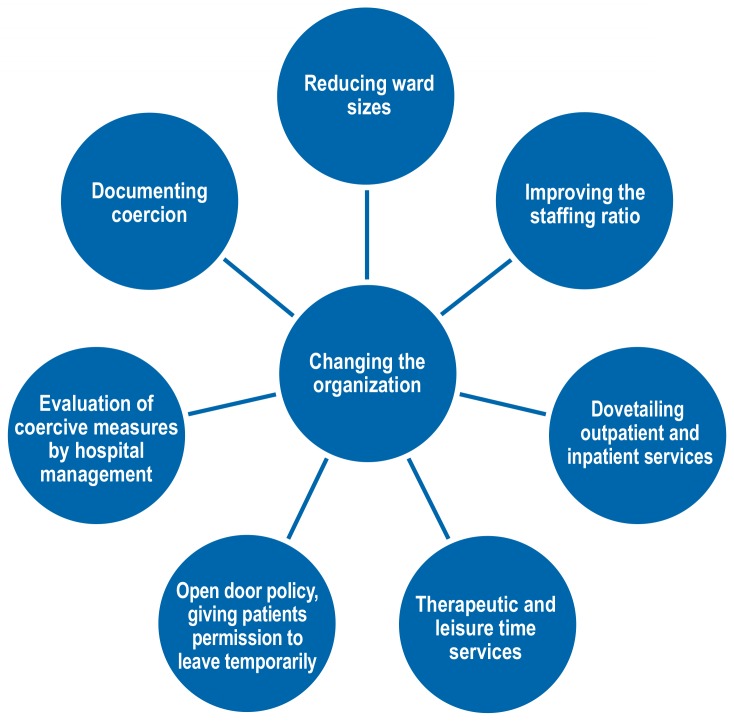

eFigure 1.

Improving the organizational framework in the psychiatric care system, especially on admission wards, as a contribution to reducing coercion

Results

A total of 90 articles (84 studies) were included (15– 33, e2– e72). Of the 84 included studies, 16 had a control group. Of these, only six studies were randomized (15– 19, e3). The controlled studies also had methodological weaknesses (Table 1, eTable).

Table 1. Controlled studies of reducing coercive measures and resultant guideline recommendations.

| Study | Randomized | Quality assessment*1 |

Evidence level*2 |

Efficacy | Intervention |

Recommendation in German clinical practice guideline (12) |

| Boumans et al. (e7) | – | Internal validity 2/9 points low quality |

2 | Number of episodes of SR *3 and cumulative duration were reduced | Complex*4 | Complex, structured treatment programs for reducing coercive measures should be undertaken and explicitly supported by the hospital management. |

| Øhlenschlæger et al. (18) | + | 3/9 low |

– | Complex | ||

| Putkonen et al. (19) | + | 4/9 low |

Number of episodes of SR and cumulative duration were reduced | Complex | ||

| Wieman et al. (29) | – | 3/9 low |

Cumulative duration of SR was reduced, number of episodes was not reduced | Complex | ||

| Phillips et al. (e3) | + | 6/9 acceptable |

2 | Number of episodes of SR was reduced | Staff training | In the context of aggression management training, all staff should be schooled and trained in de-escalation techniques and strategies to deal with aggressive behavior. |

| Bowers et al. (e9, e10) | – | 2/9 low |

3 | – | Staff training | |

| Whitecross et al. (e2) | – | 4/9 low |

3 | Cumulative duration of SR was reduced, number of episodes was not reduced | Debriefings | To reduce restraining measures, debriefings should be offered after coercive measures and documented. |

| Abderhalden et al. (16) | + | 8/9 high |

2 | Number of episodes of SR was reduced | Risk assessment |

Instruments for structured risk assessment and instruments for early intervention in case of escalation should be used in psychiatric hospitals to reduce coercion and force. |

| van de Sande et al. (17) | + | 4/9 low |

Cumulative duration of SR was reduced, numbers of episodes and proportion of patients affected by SR were not reduced | Risk assessment |

||

| Cummings et al. (e5) | – | 1/9 very low |

3 | – | Sensory modulation*5 |

As alternatives to seclusion, patients should be offered appropriate rooms/ refuges to withdraw to, with the opportunity to calm down/relax and occupy themselves. |

| Teitelbaum et al. (21) | – | 1/9 very low |

Number of episodes of SR was reduced | Sensory modulation |

||

| Lloyd et al. (22) | – | 1/9 very low |

Number of episodes of SR was reduced, cumulative and mean duration of measures was not reduced | Sensory modulation |

*1 Quality assessment according to the checklists of the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (e73)

*2 Evidence levels following the recommendations of the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (e74)

1 = Systematic review, which includes several randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

2 = Randomized controlled trial or observational study with dramatic effect

3 = Non-randomized controlled trial

4 = Before and after comparisons, case–control studies, case series

5 = Theoretical deductions, expert opinion

*3 SR: seclusion and restraint

*4 Complex intervention programs combine interventions from different areas (eg, psychotherapy, staff training, use of data)

*5 Using comforting sensory stimuli (eg, music, aromatherapy oils) to reduce tension

eTable. Controlled trials of reducing coercive measures and resultant guideline recommendations.

| Study | Randomized | Quality assessment*1 |

Evidence level*2 |

Efficacy | Intervention |

Recommendation in German clinical practice guideline (12) |

| Boumans et al. (e7) | – | Internal validity 2/9 points Low quality Not randomized, not blinded, intervention and control groups very different in terms of sex, marital status, duration of stay, treatment setting and diagnosis, synthetic control group was calculated, data on SR*3 electronically documented in a standardized way |

2 | Number of episodes of SR*3 and cumulative duration were reduced | Complex*4 | Complex, structured treatment programs for reducing coercive measures should be undertaken and explicitly supported by hospital management. |

| Øhlenschlæger et al. (18) | + | 3/9 Low Patients, treating staff not blinded, differences in treatment intensity between groups, data on SR electronically documented in a standardized way |

– | Complex | ||

| Putkonen et al. (19) | + | 4/9 Low Patients, treating staff not blinded, different sized wards in control and intervention groups, no information about whether patients were transferred between wards, data on SR electronically documented in a standardized way |

Number of episodes of SR*3 and cumulative duration were reduced | Complex | ||

| Wieman et al. (29) | – | 3/9 Low No information on comparability of different centers, the use of validated instruments, or independent raters |

Cumulative duration of SR was reduced, number of episodes was not reduced | Complex | ||

| Phillips et al. (e3) | + | 6/9 Acceptable Subjects were blinded at least to the intervention that the other participants received, use of validated instruments |

2 | Number of episodes of SR was reduced | Staff training | In the context of aggression management training, all staff members should be schooled and trained in de-escalation techniques and strategies for dealing with aggressive behavior. |

| Bowers et al. (e9, e10) | – | 2/9 Low Not blinded, comparability of wards not clear, dropout rate 20% (1 of 5 wards), SR only two components of the outcome score |

3 | – | Staff training | |

| Whitecross et al. (e2) | – | 4/9 Low Not blinded, only 20% of secluded patients participated voluntarily in the study (risk of selection bias), standardized collection of SR data prescribed by the government, use of ‧validated instruments |

3 | Cumulative duration of SR was reduced, number of episodes was not reduced | Debriefings | To reduce coercive measures, debriefings should be offered, undertaken, and documented after restrictive measures. |

| Abderhalden et al. (16) | + | 8/9 High Computer aided randomization process, control and intervention wards comparable, significant differences only compared to non-randomized “preferential” wards, use of validated instruments and external raters |

2 | Number of episodes of SR was reduced | Risk prediction | Instruments for structured risk assessment and instruments for early intervention in case of escalation should be used in psychiatric hospitals to reduce coercion and force. |

| van de Sande et al. (17) | + | 4/9 Low Not blinded, control and intervention wards differ in terms of proportions of involuntarily admitted patients and patients with personality disorders |

Cumulative duration of SR was reduced, number of episodes and rate of patients affected by SR was not reduced | Risk prediction | ||

| Cummings et al. (e5) | – | 1/9 Very low Not blinded, no information on comparability of wards and possibly other ongoing treatment programs, no data on documentation of SR |

3 | – | Sensory ‧modulation*5 | As alternatives to seclusion, patients should be offered appropriate rooms/ refuges to withdraw to, with the opportunity to calm down/relax and occupy themselves. |

| Teitelbaum et al. (21) | – | 1/9 Very low Not blinded, male ward compared with female ward, no information on diagnoses, psychopathology, or treatment, large increase in restraint rates on the control ward and great variance in the control ward not clear |

Number of episodes of SR was reduced | Sensory modulation | ||

| Lloyd et al. (22) | – | 1/9 Very low Not blinded, wards differed at the beginning in rates of restraint and numbers of restrained women, only part of the data from a standardized registry, part from patient data |

Number of episodes of SR was reduced, cumulative and mean duration of measures were not reduced | Sensory modulation |

*1 Quality assessment according to the checklists of the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (e73)

*2 Evidence levels following the recommendations of the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (e74)

1 = Systematic review, which includes several randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

2 = Randomized controlled trial or observational study with dramatic effect

3 = Non-randomized controlled trial

4 = Before and after comparisons, case-control studies, case series

5 = Theoretical deductions, expert opinion

*3 SR: seclusion and restraint

*4 Complex intervention programs combine interventions of different categories (e.g., psychotherapy, staff training, use of data)

*5 Using comforting sensory stimuli (eg, music, aromatherapy oils) to reduce tension

In principle, complex treatment programs that included several interventions were distinguished from simple interventions. We identified 38 studies that investigated complex programs.

46 studies dealt with a simple, clearly defined intervention. Seven intervention categories were identified:

Staff training

Organization

Risk assessment

Environment

Debriefings

Psychotherapy

Advance directives.

In 42 studies, staff training to improve handling of aggression and violence, as well as de-escalating counseling techniques, were evaluated. In 13 cases, this was a single individual intervention, and in 29 cases, it took the shape of complex intervention programs that included staff training as a partial intervention. Staff training as an individual/single intervention was studied only in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) from 1995, which had an observation/follow-up interval of only two weeks. The others were mainly before-and-after comparisons. In the RCT, rates of coercion were lowest in the group in which staff had received theoretical training and done practical exercises to de-escalate the situation (five episodes of restraint in two weeks versus eight or ten restraining episodes, respectively, in the groups without or with exclusively theory-based training); attacks on staff and injuries were also rarer (e3). Altogether, eight of twelve of the simple interventions for staff training and all 29 complex interventions that included staff training were accompanied by a reduction in coercion rates.

35 studies included interventions at the organizational level. Eleven studies described individual interventions and 24 studies described complex intervention programs. The interventions entailed, for example, a more detailed investigation and documentation of coercive measures, open ward doors, more staff, smaller ward sizes, and closer dovetailing of inpatient and outpatient treatment services. Overall, six out of 11 of the simple organizational interventions and 23 out of the 24 complex interventions that included organizational components were associated with a reduction in coercive measures (efigure 1). In a randomized controlled and a further non-randomized comparison trial, programs in which patients themselves were allowed to decide whether they wanted to be admitted as inpatients were found not to be effective in reducing coercive measures (15, 20). In a controlled trial, the reduction in ward size was associated with a reduction in coercive measures (e4). For the remaining simple organizational interventions, only before-and-after comparisons or retrospective studies were available.

We also studied interventions for identifying at-risk patients for aggressive behavior. The Brøset Violence Checklist as a standardized instrument to predict risk was effective in reducing seclusion rates in two RCTs. In one study, the relative risk for coercion in the intervention group was reduced by 27% (146 instances of seclusion/6074 treatment days before the intervention versus 135 instances of seclusion/7727 treatment days after the intervention), whereas in the control group, it increased by 10% (92 instances of seclusion/8449 treatment days before the intervention versus 126 instances of seclusion/10 485 treatment days after the intervention; p<0.001 [16]). In the other study the cumulative duration of the seclusion incidents was reduced by 45% (the risk of being secluded at a particular point in time on the intervention wards before the intervention was 1.12 times the risk in the control wards (95% confidence interval 1.01 to 1.19); after the intervention it was 0.62 times the risk (0.58 to 0.66, p<0.05 [17]). In the identified studies, individual crisis plans were deployed in addition to standardized risk prediction instruments, which included patient specific early warning symptoms and interventions that had been experienced as helpful. All these interventions were associated with a reduction in coercive measures.

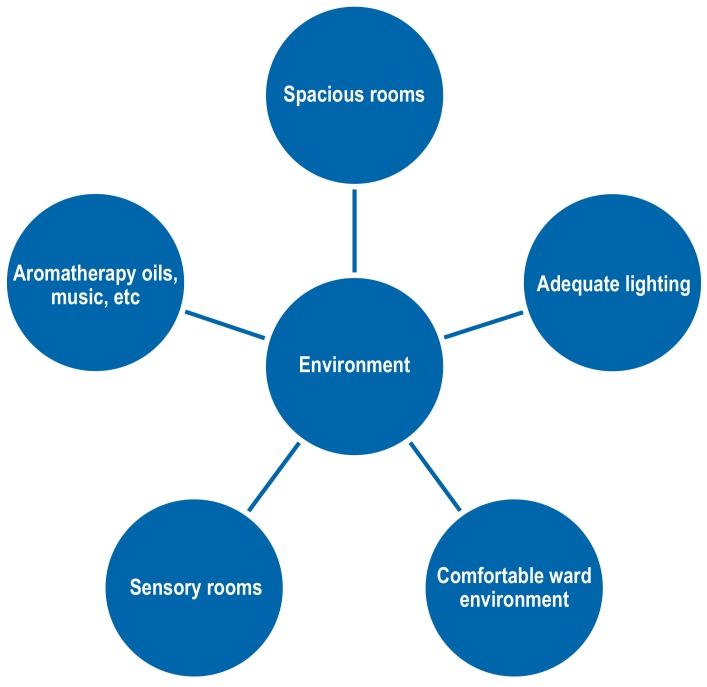

Nine studies investigated interventions to improve the therapeutic environment as an individual/single intervention, and an additional 13 studies investigated these as a part-intervention of a complex program. A total of eight studies investigated the architecture and design/layout of psychiatric wards. 16 studies investigated the therapeutic use of sensory stimuli. The latter subcategory included the provision of special rooms (“sensory rooms”) and giving patients the option to remove themselves voluntarily from stress or stimulus overload and to expose themselves instead to positive stimuli (weighted blankets, aromatherapy oils, music) (efigure 2). A total of four controlled non-randomized trials were available that had studied this approach (21, 22, e5, e6). The measures were associated with a reduction in coercive measures, as long as continuous nursing care and therapeutic instruction were given (21, 22). In these studies, coercive measures were reduced on the intervention wards, but they also increased on the control ward. For example, in one study, seclusion incidents were reduced from 157 to 53 episodes on the intervention ward, whereas on the control ward they rose from 46 to 81 (22).

eFigure 2.

Ward atmosphere and the targeted therapeutic use of sensory stimuli to reduce coercive measures on psychiatric wards (from [13])

Follow-up discussions of the coercive measure with patients took place in 13 studies. In nine studies, the behavior of the patients and staff, and their interactions, were discussed and suggestions for improvement were developed. In four studies, a trauma therapeutic debriefing took place. Only one controlled trial studied debriefings as a single/individual intervention. The seclusion intervals in the intervention group were shorter and the repeated seclusions in the intervention group were rarer. The total number of seclusions was not significantly reduced, however (e2).

Psychotherapeutic treatment programs were evaluated in 15 studies. In addition to programs that used behavioral therapeutic approaches (such as operant conditioning and social learning), some disorder specific programs for persons with personality disorders included elements of psychodynamic psychology. The studies of family therapy or those that involved relatives included elements of systemic therapy. In addition to these three large psychotherapeutic approaches/schools, individual treatment planning and life skills training were also counted among the psychotherapeutic programs. Only for one intervention did we include a controlled study that achieved by means of structured treatment planning for each patient, in combination with the systematic involvement of relatives, a reduction in seclusion measures and the time patients spent in seclusion on the intervention ward (e7). Overall, indications of the efficacy of such programs were seen in longer term treatment settings, such as in rehabilitation wards or in forensic wards/hospitals, from before-and-after comparisons. For example, in one forensic unit, instances of seclusion per patient were reduced from 4.8 to 2.3 and the average duration of such incidents fell from 11.2 hours to 5.8 hours after a program of social learning had been introduced (e8).

In studies from England, joint crisis plans reduced in part compulsory admissions/institutionalizations and the duration of inpatient stays. The results were inconsistent, however. There still isn’t any proof that coercive measures can also be reduced in this way (23). Controlled trials are lacking.

An RCT from Denmark studied the effect of integrated treatment programs in patients with an initial manifestation of schizophrenic psychosis on coercive measures. 167 outpatients and inpatients in the intervention group received assertive community treatment as well as social competence training and group psychoeducation, together with their families. 161 patients received standard treatment. Differences between the groups did not reach significance as regards the rates of inpatient seclusion and restraint (18). Of the complex treatment programs for reducing coercive measures, the Six Core Strategies, the Engagement Model, and the Safewards concept have been scientifically evaluated, in addition to the described integrated treatment program. The Six Core Strategies (box) has been studied in several countries and settings and has overall been found to be effective. Seven studies evaluating the Six Core Strategies were included in the present study (19, 24– 29), among them an RCT (19). In the RCT, the intervention was introduced in the first six months of 2009 and continued until the end of the year. Treatment days when coercive measures were used and the duration of these measures were reduced significantly, and no increase in violent assaults was noted. On the intervention wards, the proportion of days in which coercion was used fell from 30% in July of the intervention year to 15% in December (on control wards from 25% to 19%); the cumulative duration of restraint and seclusion fell from 110 hours to 56 hours (control wards: increase from 133 hours to 150 hours) (19). The cornerstones of the Engagement Model are primarily the strengthening of the therapeutic community and improvement of the atmosphere on the ward, as well as of therapeutic and leisure-time services. In a US hospital, coercion as well as injuries to staff were notably reduced over the long term (30, 31). In Europe, however, this program has thus far not been systematically used or studied. Safewards reduced seclusion and restraint according to a controlled study that included 44 psychiatric wards in Australia. After the intervention had been introduced, instances of seclusion in the wards fell by 36%, whereas rates of seclusion on wards without Safewards did not fall (32) (table 2).

BOX. Scientifically evaluated treatment programs to reduce coercion.

-

Safewards

(UK, free of charge, http://www.safewards.net)

Improving communication on the wards (appreciation, de-escalation)

Strengthening the therapeutic community

Getting to know each other for staff and patients

Calming methods—for example, sensory modulation

Dealing with good/bad news, discharge news

-

Six Core Strategies

(USA, subject to a charge)

Staff training

Senior management included

Documentation and use of data

Debriefings

Involving peers in the care of people with mental health problems

Instruments for avoiding coercive measures—for example, the Brøset Violence Checklist

-

Engagement Model

(USA, not used in the German healthcare system)

Strengthening the therapeutic community

Improving the atmosphere on the ward

Improving therapeutic and leisure time services

Table 2. Numbers of included studies that investigated different interventions.

| Intervention | No of studies (of which RCTs) |

Number of studies that reported a reduction in coercive measures |

| Environment | 9 (0) | 7 (0) |

| Organization | 11 (1) | 6 (0) |

| Staff training | 13 (1) | 9 (1) |

| Psychotherapy | 5 (0) | 5 (0) |

| Risk assessment | 5 (2) | 5 (2) |

| Debriefing | 2 (0) | 2 (0) |

| Advance directive | 1 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Complex interventions* | 38 (2) | 37 (1) |

*Complex intervention programs combine interventions from different categories (eg, psychotherapy, staff training, use of data)

RCTs, randomized controlled trials

Discussion

For our article, we intentionally chose broad inclusion criteria, which includes the methodological perspective. We accepted that the results of individual studies were in some cases probably subject to substantial biases and from a scientific/academic perspective not terribly robust. Restricting ourselves to randomized or at least controlled trials would certainly have improved things, but would have led to a great loss of data because only six or 16 studies, respectively, met these criteria. However, what applies for the RCTs as well as for the total number of studies, is that programs that begin in the wards/hospitals are effective, whereas programs that begin before inpatient admission have thus far (in the very few available studies) not shown any effect. For safety relevant endpoints, randomization is often not possible, for practical and ethical reasons. Often, if randomization of individual persons is not possible, cluster randomization at the ward level is an option (for example, half of the wards apply a certain intervention, the other half doesn’t). In contrast to pharmacological studies, blinding of the treating professionals and patients/subjects is not possible in milieu-therapeutic, psychotherapeutic, or social interventions; it isn’t possible either if institutional parameters or legal specifications change.

A further problem lies in the fact that many people who are subjected to restraining measures or seclusion are not able to give legally valid consent to study participation. In particular, prospective cohort studies without randomization should be undertaken, to which patients consent retrospectively and can then, for example, either participate in a survey on the intervention that took place, or refuse participation, in which case they would be excluded from the analysis (34). Furthermore, the individual elements of the intervention programs should be evaluated in controlled and—wherever possible—cluster randomized and at least rater-blinded studies. For example, study data on staff trainings are not consistent. One reason may be that primarily those staff members will participate in voluntary staff training who are interested in reducing force and coercion anyway. This would mean selection bias and ceiling effects. In this setting it would be necessary to study compulsory training in randomized designs in order to clarify whether empathy and motivation to reduce coercion are immutable characteristics of the staff members or whether they could be improved by further training in staff members with a greater potential for improvement.

Conclusion and outlook

Most of the interventions that formed the basis of the studies we evaluated for this review were effective. Measures should be implemented at various levels in an organization—for example, programs for the standardized documentation of violent assaults and coercive measures in the entire hospital and programs for standardized documentation and multidisciplinary debriefings after violent assaults and coercive measures on individual wards.

Almost all programs in the included studies are designed for use in psychiatric hospitals. For the systematic reduction of force and coercion, programs should also be conducted outside hospitals, in order to improve the living conditions of people with mental illness and outpatient treatment options, so as to primarily avoid crisis situations. Adequate staffing levels and financial funding for the social psychiatric support system are required, as are appropriate attitudes on the part of the staff (also emergency ambulance and police staff) and within the population.

Figure.

Flow chart showing systematic literature search and study selection

Key Messages.

Complex intervention programs have been found to be effective in randomized controlled trials. According to what is currently known, different interventions with positive effects on seclusion and restraint should be used in combination in order to optimize the effects.

In at-risk populations, risk assessment instruments (checklists) should be used in order to avoid coercion.

Staff in all professional groups that work in patient care should be trained in de-escalation techniques.

Coercive measures such as seclusion and restraint should be discussed with patients in a debriefing session.

The hospital management should take responsibility for reducing coercive measures.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Birte Twisselmann, PhD.

Acknowledgment

We thank Erich Flammer (EF) for his help in the literature selection.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Gaebel W, Falkai P. Therapeutische Maßnahmen bei aggressivem Verhalten Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie, Psychotherapie und Nervenheilkunde, eds.: S2 Praxisleitlinien in Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie. Heidelberg: Steinkopff: (1) 2010;2 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Rules and regulations: Medicare and Medicaid programs, hospital conditions of participation: patients’ rights; interim final rule. Fed Register. 1999;64:36069–36089. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brophy LM, Roper CE, Hamilton BE, Tellez JJ, McSherry BM. Consumers and their supporters’ perspectives on poor practice and the use of seclusion and restraint in mental health settings: results from Australian focus groups. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2016;10 doi: 10.1186/s13033-016-0038-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sequeira H, Halstead S. Control and restraint in the UK: service user perspectives. British Journal of Forensic Practice. 2002;4:9–18. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergk J, Flammer E, Steinert T. „Coercion Experience Scale“ (CES)—validation of a questionnaire on coercive measures. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:5.1–510. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kontio R, Joffe G, Putkonen H, et al. Seclusion and restraint in psychiatry: patients‘ experiences and practical suggestions on how to improve practices and use alternatives. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2012;48:16–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2010.00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grassi S, Mandarelli G, Polacco M, Vetrugno G, Spagnolo AG, De-Giorgio F. Suicide of isolated inmates suffering from psychiatric disorders: when a preventive measure becomes punitive. Int J Legal Med. 2018;132:1225–1230. doi: 10.1007/s00414-017-1704-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohsenian C, Verhoff MA, Riße M, Heinemann A, Püschel K. Todesfälle im Zusammenhang mit mechanischer Fixierung in Pflegeinstitutionen. Z Gerontol Geriat. 2003;36:266–273. doi: 10.1007/s00391-003-0112-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karger B, Fracasso T, Pfeiffer H. Fatalities related to medical restraint devices—asphyxia is a common finding. Forensic Sci Int. 2008;178:178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krexi L, Georgiou R, Krexi D, Sheppard MN. Sudden cardiac death with stress and restraint: the association with sudden adult death syndrome, cardiomyopathy and coronary artery disease. Med Sci Law. 2016;56:85–90. doi: 10.1177/0025802414568483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dickson BC, Pollanen MS. Fatal thromboembolic disease: a risk in physically restrained psychiatric patients. J Forensic Leg Med. 2009;16:284–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik und Nervenheilkunde e. V. (DGPPN) Verhinderung von Zwang: Prävention und Therapie aggressiven Verhaltens bei Erwachsenen. S3-Leitlinie 2018. www.dgppn.de/_Resources/Persistent/154528053e2d1464d9788c0b2d298ee4a9d1cca3/S3%20LL%20Verhinderung%20von%20Zwang%20LANG%2BLITERATUR%20FINAL%2010.9.2018.pdf (last accessed on 25 March 2019) 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirsch S. Evidenzbasierte nicht-pharmakologische Interventionen zur Reduktion von mechanischen Zwangsmaßnahmen bei Erwachsenen in psychiatrischen Kliniken - ein systematisches Review Dissertation. https://oparu.uni-ulm.de/xmlui/handle/123456789/8372 (last accessed on 25 March 2019) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik und Nervenheilkunde e. V. (DGPPN) Leitlinienreport zu Verhinderung von Zwang: Prävention und Therapie aggressiven Verhaltens bei Erwachsenen. S3-Leitlinie 2018. www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/038-022m_S3_Verhinderung-von-Zwang-Praevention-Therapie-aggressiven-Verhaltens_2018-09.pdf (last accessed on 25 March 2019) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sigrunarson V, Moljord IE, Steinsbekk A, Eriksen L, Morken G. A randomized controlled trial comparing self-referral to inpatient treatment and treatment as usual in patients with severe mental disorders. Nord J Psychiatry. 2017;71:120–125. doi: 10.1080/08039488.2016.1240231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abderhalden C, Needham I, Dassen T, Halfens R, Haug HJ, Fischer JE. Structured risk assessment and violence in acute psychiatric wards: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193:44–50. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.045534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van de Sande R, Nijman HL, Noorthoorn EO, et al. Aggression and seclusion on acute psychiatric wards: effect of short-term risk assessment. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199:473–478. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.095141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohlenschlæger J, Nordentoft M, Thorup A, et al. Effect of integrated treatment on the use of coercive measures in first-episode schizophrenia-spectrum disorder A randomized clinical trial. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2008;31:72–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Putkonen A, Kuivalainen S, Louheranta O, et al. Cluster-randomized controlled trial of reducing seclusion and restraint in secured care of men with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64:850–855. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomsen CT, Benros ME, Maltesen T, et al. Patient-controlled hospital admission for patients with severe mental disorders: a nationwide prospective multicentre study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;137:355–363. doi: 10.1111/acps.12868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teitelbaum A, Volpo S, Paran R, et al. Multisensory environmental intervention (snoezelen) as a preventive alternative to seclusion and restraint in closed psychiatric wards. Harefuah. 2007;146:11–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lloyd C, King R, Machingura T. An investigation into the effectiveness of sensory modulation in reducing seclusion within an acute mental health unit. Advances in Mental Health. 2014;12:93–100. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khazaal Y, Chatton A, Pasandin N, Zullino D, Preisig M. Advance directives based on cognitive therapy: a way to overcome coercion related problems. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74:35–38. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fisher WA. Elements of successful restraint and seclusion reduction programs and their application in a large, urban, state psychiatric hospital. J Psychiatr Pract. 2003;9:7–15. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200301000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guzman-Parra J, Aguilera Serrano C, Garcia-Sanchez JA, et al. Effectiveness of a multimodal intervention program for restraint prevention in an acute Spanish psychiatric ward. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2016;22:233–241. doi: 10.1177/1078390316644767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maguire T, Young R, Martin T. Seclusion reduction in a forensic mental health setting. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2012;19:97–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riahi S, Dawe IC, Stuckey MI, Klassen PE. Implementation of the six core strategies for restraint minimization in a specialized mental health organization. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2016;54:32–39. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20160920-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wale JB, Belkin GS, Moon R. Reducing the use of seclusion and restraint in psychiatric emergency and adult inpatient ervices—improving patient-centered care. Perm J. 2011;15:57–62. doi: 10.7812/tpp/10-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wieman DA, Camacho-Gonsalves T, Huckshorn KA, Leff S. Multisite study of an evidence-based practice to reduce seclusion and restraint in psychiatric inpatient facilities. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65:345–351. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murphy TM, Bennington-Davis M. Restraint and seclusion: the model for eliminating their use in healthcare. Hcpro Incorporated, Oregon. 2005:107–112. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blair M, Moulton-Adelman F. The engagement model for reducing seclusion and restraint: 13 years later. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2015;53:39–45. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20150211-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fletcher J, Spittal M, Brophy L, et al. Outcomes of the Victorian Safewards trial in 13 wards: impact on seclusion rates and fidelity measurement. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2017;26:461–471. doi: 10.1111/inm.12380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geoffrion S, Goncalves J, Giguère CÉ, Guay S. Impact of a program for the management of aggressive behaviors on seclusion and restraint use in two high-risk units of a mental health institute. Psychiatr Q. 2018;89:95–102. doi: 10.1007/s11126-017-9519-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bergk J, Einsiedler B, Steinert T. Feasibility of randomized controlled trials on seclusion and mechanical restraint. Clin Trials. 2008;5:356–363. doi: 10.1177/1740774508094405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Flammer E, Steinert T. Das Fallregister für Zwangsmaßnahmen nach dem baden-württembergischen Psychisch-Kranken-Hilfe-Gesetz: Konzeption und erste Auswertungen. Psychiat Prax. 2019;46:82–89. doi: 10.1055/a-0665-6728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Whitecross F, Seeary A, Lee S. Measuring the impacts of seclusion on psychiatry inpatients and the effectiveness of a pilot single-session post-seclusion counselling intervention. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2013;22:512–521. doi: 10.1111/inm.12023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.Phillips D, Rudestam, KE. Effect of nonviolent self-defense training on male psychiatric staff members‘ aggression and fear. Psychiatr Serv. 1995;46:164–168. doi: 10.1176/ps.46.2.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.O’Malley J, Frampton C, Wijnveld AM, Porter R. Factors influencing seclusion rates in an adult psychiatric intensive care unit. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care. 2007;3:93–100. [Google Scholar]

- E5.Cummings KS, Grandfield SA, Coldwell CM. Caring with comfort rooms Reducing seclusion and restraint use in psychiatric facilities. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2010;48:26–30. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20100303-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E6.Bakov S, Birur B, Bearden MF, Aguilar B, Ghelani KJ, Fargason RE. Sensory reduction on the general milieu of a high-acuity inpatient psychiatric unit to prevent use of physical restraints: a successful open quality improvement trial. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2018;24:133–144. doi: 10.1177/1078390317736136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.Boumans CE, Egger JI, Souren PM, Hutschemaekers GJ. Reduction in the use of seclusion by the methodical work approach. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2014;23:161–170. doi: 10.1111/inm.12037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E8.Goodness KR, Renfro NS. Changing a culture: a brief program analysis of a social learning program on a maximum-security forensic unit. Behav Sci Law. 2002;20:495–506. doi: 10.1002/bsl.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Bowers L, Brennan G, Flood C, Lipang M, Oladapo P. Preliminary outcomes of a trial to reduce conflict and containment on acute psychiatric wards: city nurses. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2006;13:165–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2006.00931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E10.Bowers L, Flood C, Brennan G, Allan T. A replication study of the city nurse intervention: reducing conflict and containment on three acute psychiatric wards. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2008;15:737–742. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2008.01294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E11.Ala-Aho S, Hakko H, Saarento O. Reduction of involuntary seclusions in a psychiatric ward. Duodecim. 2003;119:1969–1975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E12.Ash D, Suetani S, Nair J, Halpin M. Recovery-based services in a psychiatric intensive care unit—the consumer perspective. Australas Psychiatry. 2015;23:524–527. doi: 10.1177/1039856215593397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E13.Belanger S. The ‚S&R challenge‘: reducing the use of seclusion and restraint in a state psychiatric hospital. J Healthc Qual. 2001;23:19–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2001.tb00319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E14.Bell A, Gallacher N. Succeeding in sustained reduction in the use of restraint using the improvement model. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2016;5 doi: 10.1136/bmjquality.u211050.w4430. pii: u211050.w4430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E15.Blair EW, Woolley S, Szarek BL, et al. Reduction of seclusion and restraint in an inpatient psychiatric setting: a pilot study. Psychiatr Q. 2017;88:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s11126-016-9428-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E16.Hardesty S, Borckardt JJ, Hanson R, et al. Evaluating initiatives to reduce seclusion and restraint. J Healthc Qual. 2007;29:46–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2007.tb00205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E17.Borckardt JJ, Madan A, Grubaugh AL, et al. Systematic investigation of initiatives to reduce seclusion and restraint in a state psychiatric hospital. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62:477–483. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.5.pss6205_0477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E18.Borckardt JJ, Grubaugh AL, Pelic CG, Danielson CK, Hardesty SJ, Frueh BC. Enhancing patient safety in psychiatric settings. J Psychiatr Pract. 2007;13:355–361. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000300121.99193.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E19.Madan A, Borckardt JJ, Grubaugh AL, et al. Efforts to reduce seclusion and restraint use in a state psychiatric hospital: a ten-year perspective. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65:1273–1276. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E20.Cibis ML, Wackerhagen C, Müller S, Lang UE, Schmidt Y, Heinz A. Comparison of aggressive behavior, compulsory medication and absconding behavior between open and closed door policy in an acute psychiatric ward. Psychiatr Prax. 2017;44:141–147. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-105181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E21.Clarke DE, Brown AM, Griffith P. The Brøset Violence Checklist: clinical utility in a secure psychiatric intensive care setting. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2010;17:614–620. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2010.01558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E22.Donat DC. Impact of a mandatory behavioral consultation on seclusion/restraint utilization in a psychiatric hospital. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1998;29:13–19. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7916(97)00039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E23.Donat DC. Employing behavioral methods to improve the context of care in a public psychiatric hospital: reducing hospital reliance on seclusion/restraint and psychotropic PRN medication. Cogn Behav Pract. 2002;9:28–37. [Google Scholar]

- E24.Donat DC. Impact of improved staffing on seclusion/restraint reliance in a public psychiatric hospital. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2002;25:413–416. doi: 10.1037/h0094994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E25.Donat DC. An analysis of successful efforts to reduce the use of seclusion and restraint at a public psychiatric hospital. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:1119–1123. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.8.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E26.D‘Orio BM, Purselle D, Stevens D, Garlow SJ. Reduction of episodes of seclusion and restraint in a psychiatric emergency service. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:581–583. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.5.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E27.Espinosa L, Harris B, Frank J, et al. Milieu improvement in psychiatry using evidence-based practices: the long and winding road of culture change. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2015;29:202–207. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E28.Fluttert FA, van Meijel B, Nijman H, Bjørkly S, Grypdonck M. Preventing aggressive incidents and seclusions in forensic care by means of the ‚Early Recognition Method‘. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19:1529–1537. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E29.Forster PL, Cavness C, Phelps MA. Staff training decreases use of seclusion and restraint in an acute psychiatric hospital. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 1999;13:269–271. doi: 10.1016/s0883-9417(99)80037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E30.Godfrey JL, McGill AC, Joness NT, Oxley SL, Carr RM. Anatomy of a transformation: a systematic effort to reduce mechanical restraints at a state psychiatric hospital. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65:1277–1280. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E31.Gonzalez-Torres MA, Fernandez-Rivas A, Bustamante S, et al. Impact of the creation and implementation of a clinical management guideline for personality disorders in reducing use of mechanical restraints in a psychiatric inpatient unit. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;16 doi: 10.4088/PCC.14m01675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E32.Guzman-Parra J, Garcia-Sanchez JA, Pino-Benitez I, Alba-Vallejo M, Mayoral-Cleries F. Effects of a regulatory protocol for mechanical restraint and coercion in a Spanish psychiatric ward. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2015;51:260–267. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E33.Hamilton B, Love A. Reducing reliance on seclusion in acute psychiatry. Aust Nurs J. 2010;18 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E34.Hellerstein DJ, Staub AB, Lequesne E. Decreasing the use of restraint and seclusion among psychiatric inpatients. J Psychiatr Pract. 2007;13:308–317. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000290669.10107.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E35.Hoch JS, O‘Reilly RL, Carscadden J. Relationship management therapy for patients with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:179–181. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E36.Jones DW. Pennsylvania hospital continues to reduce seclusion and restraints. Jt Comm Perspect. 1997;17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E37.Jonikas JA, Cook JA, Rosen C, Laris A, Kim JB. A program to reduce use of physical restraint in psychiatric inpatient facilities. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:818–820. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.7.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E38.Jungfer HA, Schneeberger AR, Borgwardt S, et al. Reduction of seclusion on a hospital-wide level: successful implementation of a less restrictive policy. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;54:94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E39.Khadivi AN, Patel RC, Atkinson AR, Levine JM. Association between seclusion and restraint and patient-related violence. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:1311–1312. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.11.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E40.Laker C, Gray R, Flach C. Case study evaluating the impact of de-escalation and physical intervention training. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2010;17:222–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2009.01496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E41.Lewis M, Taylor K, Parks J. Crisis prevention management: a program to reduce the use of seclusion and restraint in an inpatient mental health setting. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2009;30:159–164. doi: 10.1080/01612840802694171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E42.Lorenzo RD, Miani F, Formicola V, Ferri P. Clinical and organizational factors related to the reduction of mechanical restraint application in an acute ward: an 8-year retrospective analysis. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2014;10:94–102. doi: 10.2174/1745017901410010094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E43.Lykke J, Austin SF, Mørch MM. Cognitive milieu therapy and restraint within dual diagnosis populations. Ugeskrift for laeger. 2008;170:339–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E44.MacDonald A. Reducing seclusion in a psychiatric hospital. Nurs Times. 1989;85:58–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E45.McCue RE, Urcuyo L, Lilu Y, Tobias T, Chambers MJ. Reducing restraint use in a public psychiatric inpatient service. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2004;31:217–224. doi: 10.1007/BF02287384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E46.Needham I, Abderhalden C, Meer R, et al. The effectiveness of two interventions in the management of patient violence in acute mental inpatient settings: report on a pilot study. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2004;11:595–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2004.00767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E47.Novak T, Scanlan J, McCaul D, MacDonald N, Clarke T. Pilot study of a sensory room in an acute inpatient psychiatric unit. Australas Psychiatry. 2012;20:401–406. doi: 10.1177/1039856212459585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E48.Olver J, Love M, Daniel J, Norman T, Nicholls D. The impact of a changed environment on arousal levels of patients in a secure extended rehabilitation facility. Australas Psychiatry. 2009;17:207–211. doi: 10.1080/10398560902839473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E49.Petrakis M, Penno S, Oxley J, Bloom H, Castle D. Early psychosis treatment in an integrated model within an adult mental health service. Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27:483–488. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E50.Prescott DL, Madden LM, Dennis M, Tisher P, Wingate C. Reducing mechanical restraints in acute psychiatric care settings using rapid response teams. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2007;34:96–105. doi: 10.1007/s11414-006-9036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E51.Richmond I, Trujillo D, Schmelzer J, Phillips S, Davis D. Least restrictive alternatives: do they really work? J Nurs Care Qual. 1996;11:29–37. doi: 10.1097/00001786-199610000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E52.Rohe T, Dresler T, Stuhlinger M, Weber M, Strittmatter T, Fallgatter AJ. Architectural modernization of psychiatric hospitals influences the use of coercive measures. Nervenarzt. 2017;88:70–77. doi: 10.1007/s00115-015-0054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E53.Smith S, Jones J. Use of a sensory room on an intensive care unit. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2014;52:22–30. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20131126-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E54.Stead K, Kumar S, Schultz TJ, et al. Teams communicating through STEPPS. Med J Aust. 2009;190:128–132. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E55.Sullivan AM, Bezmen J, Barron CT, Rivera J, Curley-Casey L, Marino D. Reducing restraints: alternatives to restraints on an inpatient psychiatric service—utilizing safe and effective methods to evaluate and treat the violent patient. Psychiatr Q. 2005;76:51–65. doi: 10.1007/s11089-005-5581-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E56.Sullivan D, Wallis M, Lloyd C. Effects of patient-focused care on seclusion in a psychiatric intensive care unit. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2004;11:503–508. [Google Scholar]

- E57.Taxis JC. Ethics and praxis: alternative strategies to physical restraint and seclusion in a psychiatric setting. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2002;23:157–170. doi: 10.1080/016128402753542785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E58.Templeton L, Gray S, Topping J. Seclusion: changes in policy and practice on an acute psychiatric unit. J Ment Health. 1998;7:199–202. [Google Scholar]

- E59.Yang CP, Hargreaves WA, Bostrom A. Association of empathy of nursing staff with reduction of seclusion and restraint in psychiatric inpatient care. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65:251–254. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E60.Ashcraft L, Anthony W. Eliminating seclusion and restraint in recovery-oriented crisis services. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:1198–1202. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.10.1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E61.Corrigan P, Holmes PE, Luchins D, Basit A, Buican B. The effects of interactive staff training on staff programing and patient aggression in a psychiatric inpatient ward. Behavioral Interventions. 1995;10:17–32. [Google Scholar]

- E62.Craig C, Ray F, Hix C. Seclusion and restraint: decreasing the discomfort. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1989;27:17–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E63.Morales E, Duphorne PL. Least restrictive measures: alternatives to four-point restraints and seclusion. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1995;33:13–16. doi: 10.3928/0279-3695-19951001-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E64.Steinert T, Eisele F, Göser U, Tschöke S, Solmaz S, Falk S. Quality of process and results in psychiatry: decreasing coercive interventions and violence among patients with personality disorder by implementation of a crisis intervention ward. Gesundh ökon Qual manag. 2009;14:44–48. [Google Scholar]

- E65.Andersen C, Kolmos A, Andersen K, Sippel V, Stenager E. Applying sensory modulation to mental health inpatient care to reduce seclusion and restraint: a case control study. Nord J Psychiatry. 2017;71:525–528. doi: 10.1080/08039488.2017.1346142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E66.Goulet MH, Larue C, Lemieux AJ. A pilot study of “post-seclusion and/or restraint review“ intervention with patients and staff in a mental health setting. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2018;54:212–220. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E67.Hernandez A, Riahi S, Stuckey MI, Mildon BA, Klassen PE. Multidimensional approach to restraint minimization: the journey of a specialized mental health organization. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2017;26:482–490. doi: 10.1111/inm.12379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E68.Hochstrasser L, Fröhlich D, Schneeberger AR, et al. Long-term reduction of seclusion and forced medication on a hospital-wide level: implementation of an open-door policy over 6 years. Eur psychiatry. 2018;48:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E69.Mann-Poll PS, Smit A, Noorthoorn EO, et al. Long-term impact of a tailored seclusion reduction program: evidence for change? Psychiatr Q. 2018;89:733–746. doi: 10.1007/s11126-018-9571-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E70.Newman J, Paun O, Fogg L. Effects of a staff training intervention on seclusion rates on an adult inpatient psychiatric unit. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2018;56:23–30. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20180212-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E71.Steinauer R, Huber CG, Petitjean S, et al. Effect of door-locking policy on inpatient treatment of substance use and dual disorders. Eur Addict Res. 2017;23:87–96. doi: 10.1159/000458757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E72.Wullschleger A, Berg J, Bermpohl F, Montag C. Can „Model Projects of Need-Adapted Care“ reduce involuntary hospital treatment and the use of coercive measures? Front Psychiatry. 2018;9 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E73.ScottishIntercollegiate Guidelines Network. Critical appraisal notes and checklists. www.sign.ac.uk/checklists-and-notes.html (last access on 9 March 2019) [Google Scholar]

- E74.Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. Levels of evidence. www.cebm.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/CEBM-Levels-of-Evidence-2.1.pdf (last accessed on 9 March 2019) [Google Scholar]