Abstract

Genomic discovery efforts in patients with cancer have been critical in identifying a recurrent theme of mutations in epigenetic modifiers. A number of novel and exciting basic biological findings have come from this work including the discovery of an enzymatic pathway for DNA cytosine demethylation, a link between cancer metabolism and epigenetics, and the critical importance of post-translational modifications at specific histone residues in malignant transformation. Identification of cancer cell dependency on a number of these mutations has quickly resulted in the development of therapies targeting several of these genetic alterations. This includes, the development of mutant-selective IDH1 and IDH2 inhibitors, DOT1L inhibitors for MLL rearranged leukemias, EZH2 inhibitors for several cancer types, and the development of bromodomain inhibitors for many cancer types—all of which are in early phase clinical trials. In many cases, however, specific genetic targets linked to malignant transformation following mutations in individual epigenetic modifiers are not yet known. In this review we present functional evidence of how alterations in frequently mutated epigenetic modifiers promote malignant transformation and how these alterations are being targeted for cancer therapeutics.

Keywords: ASXL1, BAP1, CREBBP, DNMT3A, EP300, EZH2

1. Introduction

Recent progress in systematic sequencing of human malignancies has identified recurrent mutations in epigenetic modifiers as a consistent theme throughout human cancer. Several of these mutated genes, or classes of genetic alterations, appear to be distinctly associated with specific disease phenotypes which have shed light on new mechanisms of malignant transformation. Moreover, many mutations in epigenetic regulatory genes result in a gain-of-function which is potentially directly targetable. Thus, identification of mutations in epigenetic regulatory genes has provided important information about disease pathogenesis as well as potential new avenues of therapy.

In this review we discuss novel classes of mutated disease alleles in genes encoding epigenetic modifying proteins. These include somatic point mutations and/or translocations in genes directly involved in DNA cytosine methylation modification (TET2, IDH1/2), genes encoding enzymes which modify histone proteins (EZH2, BAP1, MLL1–3, CREBBP, EP300), as well as those required for histone enzyme complexes to function (EED, SUZ12, and ASXL1), and genes encoding histone H3 proteins themselves. This review focuses on the epigenetic aberrations thought to be attributable to these mutations and how these epigenetic alterations might contribute to malignant transformation. In addition, we highlight the potential clinical value of understanding these mutations, as they may be therapeutically targetable in some instances.

2. Mutations in genes affecting DNA methylation

2.1. DNMT3A

The mammalian family of methyltransferases comprises three active DNA methyltransferases that enzymatically add a methyl group to cytosine in CpG dinucleotides in DNA. DNMT1 is a maintenance methyltransferase that methylates the newly synthesized CpG dinucleotides on the hemimethylated DNA during DNA replication. DNMT3A and DNMT3B are primarily responsible for de novo DNA methylation, with a high expression level during embryogenesis. The catalytically inactive member of the family, DNMT3L, contributes to the regulation of DNMT3A oligomerization and enhances its methyltransferase activity.

Somatic mutations of DNMT3A were first identified in adult AML patients [1,2]. Recurrence studies found DNMT3A mutations in ~30% of normal karyotype AML cases, making it one of the most frequently mutated genes in AML [3]. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that mutations in DNMT3A confer poor prognosis and decreased overall survival in AML [4]. The rate of DNMT3A mutations varies by AML subtype, with the highest rate (20%) seen among cases with monocytic lineage (M4, M5) [5,6]. Mutations occur as a nonsense or frameshift alternation, or missense mutations.

More than 50% of DNMT3A mutations in AML are heterozygous missense mutations at the R882 residue within the catalytic domain, most commonly resulting in an Arginine to Histidine amino acid exchange. A murine BMT model with hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells transduced by DNMT3A R882H acquired a chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML)-like disease phenotype, with clinical features reminiscent of human AML with DNMT3A mutation [7]. The findings of this study suggest that this mutation alone is capable of initiating leukemia. However, in AML cells, R882 mutations always occur with retention of the wild-type allele, suggesting that the R882 mutant may serve as a dominant-negative regulator of wild-type DNMT3A. To establish this assumption, it has been shown that when exogenously expressed in murine embryonic stem (ES) cells, mouse DNMT3A R878H (corresponding to human R882H) proteins fail to mediate DNA methylation, but interact with wildtype proteins. When the wildtype and mutant forms were coexpressed in the murine ES cells, the wildtype DNA methylation ability was inhibited [8]. Furthermore, in a recent study of this mutation’s mechanism, size-exclusion chromatography analysis demonstrated that the mutant enzyme inhibits the ability of the wildtype enzyme to form functional tetramers, which are required for maximal de novo methylation activity [9]. This may explain the protein intrinsic mechanism through which R882H DNMT3A function as a dominant-negative inhibitor of de novo DNA methylation. Nevertheless, ~40% of DNMT3A mutations occur outside of the R882 missense mutation. Many of these alterations are predicted to cause haploinsufficiency of DNMT3A, with potentially no significant alterations in DNA methylation. The mechanisms of these mutations’ contribution to leukemogenesis remain to be elucidated.

2.2. TET2

The Ten-Eleven Translocation (TET) family, consisting of three proteins (TET 1–3), is named after the rare t(10;11)(q22;q23) translocation that was demonstrated in a subset of AML patients harboring TET1 translocated with MLL1 [10]. TET proteins are mammalian DNA hydroxylases which catalyze the conversion of the methyl group at the 5-position of cytosine of DNA (5-methylcytosine (5mC)) to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), in a reaction which requires Fe(II) and α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) as substrates [11]. The TET family of enzymes then perform iterative oxidation of 5hmc to produce 5-formylcytosine (5fC) followed by 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC). These derivatives of 5mC oxidation are likely to be intermediates in the DNA demethylation process, through an active and passive manner. Moreover, they may affect the activity of different Methyl-CpG Binding Domain (MBD) proteins and thus alter the recruitment of chromatin regulation, or have direct effects on transcription. Genome-wide mapping of 5hmC in ES cells has identified that 5hmC is distinctly distributed at transcription start sites and within gene bodies [12,13]. It is also more commonly present in gene exons than introns.

In parallel with studies that initially described the catalytic activity of the TET family of enzymes, mutations in TET2 were found in 8–23% patients with myeloid hematopoietic malignancies [14–16]. Mutations in TET2 are especially enriched in CMML where they occur in ~50% of such patients and in cytogenetically normal AML (CN AML) where the frequency of TET2 mutations is 18–23% [17]. Given the frequency and clinical importance of TET2 mutations in myeloid malignancies, the global and site-specific levels of 5hmC in patients bearing these mutations have been studied. Although several studies have reported a decrease in global 5hmC levels in patients with myeloid malignancies with mutations in TET2 [18,19], there is no conclusive evidence regarding the 5mC site-specific levels. The effect of TET2 mutations on 5mC, 5hmC, and the relationship of these modified bases to gene transcription at specific gene targets are an area of active investigation.

In order to understand the role of TET2 in hematopoiesis, multiple Tet2 knockout mouse models have been created. Through analysis of 5 different murine models, it is clear that Tet2 knockout mice develop progressive expansion of the hematopoietic stem progenitor compartment, increased hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) self-renewal, and finally a proliferative myeloid malignancy, reminiscent of human CMML [20–22]. Deletion of Tet2 alone does not seem to result in AML in mice.

3. Mutations in genes affecting both DNA methylation and histone modifications

3.1. IDH 1/2

Isocitrate Dehydrogenase 1 and 2 (IDH 1/2) are NADP-dependent enzymes that catalyze the oxidative decarboxylation of Isocitrate to α-Ketoglutarate (α-KG) while reducing NADP+ to NADPH. IDH1/2 are mutated in a range of myeloid malignancies, specifically in AML, where IDH1 and IDH2 mutations occur in up to 16–19% of adult CN-AML patients, respectively [14,23,24]. Mutations in IDH1/2 are also present in ~70% of secondary glioblastoma mutiforme patients, as well as in colorectal cancer, cholangiocarcinoma, thyroid cancer and other solid tumors. These mutations are always heterozygous, and occur at 3 specific residues: R132 in IDH1, and either R140 (Arginine to Glutamine substitution) or R172 in IDH2. The mutant form of IDH1/2 enzymes result in a neomorphic activity resulting in the ability to convert α-KG into 2-Hydroxyglutarate (2HG) through oxidation of NADP [25,26]. This, in turn, results in abnormal accumulation of 2HG in cells. Due to the similarity of 2HG to α-KG, 2HG, when present in high levels, competes with α-KG and inhibits α-KG-dependent reactions. α-KG-dependent reactions include the oxidation of 5mC and its derivatives by the Tet family of enzymes. Accordingly, the biological implication of 2-HG exposure is impaired myeloid differentiation and cytokine-independent growth in TF-1 cells which normally depend on granulocyte macrophage–colony-stimulating factor for growth. A conditional IDH1 (R132H) knockin (KI) mouse model has since been reported to display an age-dependent blockade of hematopoietic differentiation, similar to the phenotype of Tet2 null mice. Nevertheless, expression of this IDH1 mutant form in the hematopoietic system solely did not result in AML in vivo. Among other α-KG-dependent enzymatic reactions that are inhibited by accumulation of 2HG, noteworthy are the Jumonji-C domain-containing (JMJC) family of histone lysine demethylases, specifically those demethylating lysines 9 and 36 of histone H3 (H3K9, H3K36) [27].

Prognostic relevance of mutations in IDH1/2 have been examined in multiple large cohorts of AML patients. IDH2 mutations at the R140 residue were specifically associated with a favorable outcome in AML patients from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) E1900 cohort, both in the entire cohort without regard to the cytogenetic subset as well as in CN AML patients [14]. Moreover, the subset of patients with both IDH1/2 and NPM1 mutations, showed to significantly co-occur in multiple clinical correlative studies, had a particularly favorable outcome, superior to that of the cytogenetically favorable subset of AML patients.

Based on progress in understanding the altered metabolic function of the mutant IDH1/2 enzymes, studies targeting these enzymes with specific drugs have emerged. Rohle et al. [28] used a selective R132H-IDH1 inhibitor to block the ability of the mutant enzyme to produce R-2HG in multiple in vitro and in vivo models of gliomas with IDH1 mutations. The R-2HG inhibition resulted in H3K9 demethylation and expression of gliogenic-differentiation-associated genes that were suppressed with the presence of the active mutant enzyme. Moreover, the R132-IDH1 inhibitor impaired IDH1-mutant glioma cell growth without an effect on IDH1 wildtype cell growth. Surprisingly, there were no significant DNA-methylation changes genome wide in the presence of the mutant-enzyme inhibitor. This finding raises the need of further investigations of the pathway in which glioma growth is promoted by mutant IDH1.

In parallel to the work on R132-IDH1 inhibition, Wang et al. [29] developed a selective inhibitor of the mutant R140Q-IDH2 enzyme. In vitro treatment of TF-1 erythroleukemia and primary human AML cells with this molecule resulted in induction of cell differentiation, supporting the relevance of the mutant enzyme as a therapeutic drug target. To enhance the understanding of mutant IDH1/2’s role in AML progression, Kats et al. [30]. generated a transgenic IDH2-R140Q KI mouse model in an on/off- and tissue-specific manner using a tetracycline-inducible system. They examined the oncogenic potential of mutant IDH2 concurrent with FLT3 mutations and other transformation related over-expressed proteins. They found that the IDH2-R140Q mutation could cooperate with other mutations to initiate AML. Furthermore, the growth of the leukemic cells in these mice was highly affected by genetic deinduction of the IDH2 mutation, suggesting this mutant enzyme to be an excellent potential therapeutic target in AML.

At the 2014 American Association of Cancer Research (AACR) annual meeting, early phase clinical trials results of the first IDH inhibitor to enter clinical trials, AG-221, were presented [31]. Early results of the phase I dose escalation study of AG-221 treatment for patients with IDH2-mutant hematologic malignancies revealed initial clinical and pharmacodynamic activity of the drug, which also appeared to be well tolerated. Six of seven evaluable patients had objective responses which are ongoing, including three who had a complete remission (CR) and two who had a CR with incomplete platelet recovery. Moreover, there was >90% reduction in the levels of 2-HG, providing proof-of-principle for the drug’s mechanism of action at doses in this phase I trial. Further results of this ongoing study are anticipated in the near future.

4. Mutations in genes affecting histone modifications

4.1. UTX

The methylation and demethylation of histone proteins at specific residues is essential for maintenance of active and silent states of gene expression in developmental processes. KDM6A, also named UTX (Ubiquitously Transcribed Tetratricopeptide Repeat on Chromosome X), is a member of the JMJ family of histone lysine demethylases. These are Fe(II)- and α-KG-dependent oxygenases which constitute important components of regulatory transcriptional chromatin complexes [32,33]. UTX, located on Xp11.2, encoding a protein which demethylates di- and trimethyl groups on lysine 27 of histone encodes a (H3K27me2/3) [34,35] (See Fig. 1). UTX plays essential roles in normal development, as it is critically required for correct reprogramming, embryonic development and tissue-specific differentiation [36]. Constitutional inactivation of UTX causes a specific hereditary disorder, Kabuki syndrome [37].

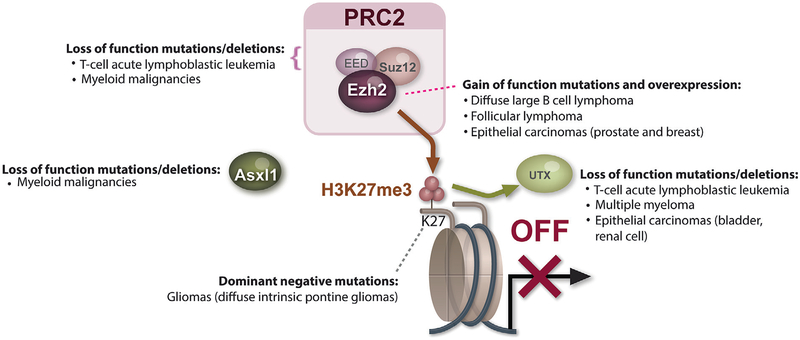

Fig. 1.

Cancer associated changes regulating histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27) methylation. In order to illustrate the wide variety of epigenetic alterations converging on a single epigenetic mechanism in cancer, the genetic alterations associated with alterations in H3K27 methylation are illustrated. Each of the genes portrayed are mutated in cancer and encode proteins which directly or indirectly affect H3K27me3 (in addition to possible additional effects in the cell). For instance, EZH2 is affected by both loss-of-function mutations and deletions in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) as well as in myeloid malignancies. In contrast, somatic point mutations which confer increased enzymatic activity to EZH2 are found in diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and follicular lymphoma (FL). SUZ12 and EED, which form an enzymatic complex with EZH2, known as the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) are also occasionally deleted and/or affected by loss-of-function mutations in myeloid malignancies. The Polycomb associated protein ASXL1 has been found to be associated with global abundance of H3K27 methylation and is frequently deleted and/or affected by loss-of-function mutations in myeloid malignancies as well. UTX, which encodes an enzyme which demethylates di- and trimethyl groups on H3K27 (H3K27me2/3), is frequently deleted and/or affected by loss-of-function mutations in multiple myeloma, T-ALL, and several epithelial carcinomas including renal cell carcinoma and bladder urothelial carcinoma. Finally, as evidence of the importance of H3K27 methylation, this exact residue of histone H3.3 is occasionally mutated in cancer. Histone H3.3 mutations are most enriched in a specific subtype of pediatric gliomas known as diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas.

Exome- and genome-wide sequencing strategies identified recurrent inactivating UTX mutations and deletions in multiple cancer types including multiple myeloma (MM), leukemias, as well as multiple solid tumor types including esophageal and renal cancer [38–46] Noteworthy is the high frequency of UTX mutations in bladder carcinoma, as reported by Gui et al. [41] and Ross et al.[47], most commonly consisting of truncating mutations in the functional JmjC domain coding region.

Due to its high association with disease and well-defined catalytic mechanism, UTX is an attractive target for drug development. The use of structure-guided design has led to the first highly potent and selective inhibitor of JmjC-domain containing enzymes including UTX and JMJD3 (also known as KDM6B) [48]. This study provided proof of concept for generating specific JmjC-domain inhibitors. As research progresses, the role of UTX as bona fide tumor suppressor is anticipated to be confirmed, and the potential of JmjC-domain small molecule inhibitors as a therapeutic option for cancers will be investigated.

4.2. The Polycomb Repressive Complex 2

The Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) is one of the classes of Polycomb-group proteins (PcG) which are transcriptional repressors with a crucial function in the maintenance of cell identity and regulation of differentiation in different cellular contexts. This complex is evolutionarily conserved throughout vertebrates, and consists of four core members: Embryonic Ectoderm Development (EED), Supressor of Zeste 12 Homologue (SUZ12), RbAp48 (also named RBBP4), and Enhancer of Zeste Homolog 1 or 2 (EZH1/EZH2) [49] (See Fig. 1). PRC2 plays an essential role in the initiation and maintenance of transcriptional silencing of specific histones through methylation of H3K27 [49,50] by the catalytic component EZH1 or EZH2. Whereas EZH1 abnormalities are not known to have a role in human malignancies, alterations in EZH2 have been implicated in transformation of human malignancies. The identification of somatic mutations in EZH2 was first established through exome sequencing in follicular and diffuse large B-cell lymphomas of germinal-center origin (follicular lymphoma (FL) and germinal center B-cell like diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCL)) by Morin et al. [51], followed by additional descriptions of somatic heterozygous mutations in the SET domain of EZH2. These studies identified missense alterations at Tyrosine 641, Alanine 687 or Alanine 677 in lymphoid malignancies. Sneeringer et al., Yap et al. and Majer et al. demonstrated that the catalytic efficiency and the enzyme turnover number of the Y641 or Y687 mutant EZH2 increases with the H3K27 methylation status [52–54]. This suggests that alterations of Y641 in EZH2 are gain-of-function mutations, as the mutant enzyme has increased enzymatic activity to methylate mono- and dimethylated H3K27. Given that the mutation is consistently heterozygous, co-existence of mutant and wildtype EZH2 results in increased H3K27me3. The A677 mutant of EZH2 was shown to enhance EZH2 enzymatic methylation regardless of H3K27 methylation state [55]. In order to understand the biological consequence and transcriptional targets of this gain-of-function mutation in EZH2, a transgenic conditional KI model of Ezh2 Y641F has been studied [56]. Conditional expression of mutant EZH2 in this model was found to suppress the expression of germinal center exit genes, resulting in germinal center hyperplasia. Moreover, expression of EZH2 Y641F accelerated lymphomagenesis in cooperation with BCL2.

Interestingly, while EZH2 is affected by gain-of-function mutations in lymphomas, somatic missense, nonsense and frameshift mutations predicted to result in loss of function were found throughout the open reading frame of EZH2 in patients with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) and chronic myeloid malignancies [57–60]. Among myeloid malignancies patients, mutations in EZH2 are most commonly found in myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) [61], myelofibrosis [62,63] and MDS/myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) overlap syndrome patients [63], and rarely found in primary acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [14]. In MDS and myelofibrosis patients, EZH2 mutations confer adverse prognosis [61,64]. Recent work by Muto et al. identified the potential contribution of Ezh2 loss to myeloid malignancy pathogenesis [65]. The authors studied mice with conditional homozygous deletion of Ezh2 in the hematopoietic compartment alone and in combination with Tet2 deletion. Ezh2 and Ezh2/Tet2 double knockout mice developed MDS/MPN like disease. Gene expression profiling and H3K27me3 ChIP-Seq analysis of progenitor cells from these mice identified prominent upregulation of Myc and associated genes with Ezh2 loss as well as upregulation of many direct PcG targets which are potential oncogenes, including Hmga2, Pbx3, and Lmo1. This work suggests that derepression of PcG-targeted oncogenes in conjunction with the up-regulation of the Myc module could function as the major drivers of EZH2-mutant MDS/MPN disease.

In contrast to myeloid malignancies, NOTCH1 is established as a key oncogene driving T-ALL, and oncogenic NOTCH1 appears to oppose PRC2-mediated gene silencing when activated in the pathogenesis of T-ALL [58]. EZH2 among other PRC2 members are displaced from the promoters of some NOTCH1 known target genes. Furthermore, increased tumorogenic potential was demonstrated in T-ALL xenografted cell lines with loss of EZH2 [58].

The explanation for differences between loss of function mutations in EZH2 in some malignancies and gain-of-function and over-expression in others remains unclear. However, these data do suggest that EZH2 can serve as either a tumor suppressor or an oncogene depending on tissue context.

Similar to mutations in EZH2, loss-of-function mutations and deletions in EED and SUZ12 have also been in myeloid malignancies [66,67] and in T-ALL [58,59]. These mutations are typically heterozygous and loss-of-function in nature, suggesting that they function as haploinsufficient tumor suppressors.

4.3. ASXL1

Additional sex combs (Asx) gene encodes a chromatin-binding protein required for normal determination of segment identity in the developing embryo in Drosophila. The human homolog of this gene, ASXL1 (Asx-like), functions in a dense network of physical interactions, interacts with the PRC2 complex in myeloid hematopoietic cells, and is associated with global abundance of H3K27 methylation [68].

Gelsi-Boyer et al. [69] were the first to report somatic deletion and mutations in ASXL1 in MDS and CMML patients. ASXL1 somatic mutations are also observed in myelofibrosis, MDS/MPN overlap disorders, and AML transformed from MDS [63]. Multiple studies found these mutations to confer adverse overall survival in AML and MDS [14,70,71]. Due to the high prevalence of ASXL1 mutations (occurring in 15–20% of MDS and 40–60% MDS/MPN overlap syndrome patients [69,72,73]), and clinical importance of these mutations, we [68] investigated the mechanisms of transformation by ASXL1 mutations. Myeloid leukemia cells with endogenous ASXL1 mutations were associated with loss of ASXL1 expression. In addition, a positive correlation between ASXL1 expression and global H3K27 mono-, di- and trimethylation was observed (See Fig. 1). Finally, targets of ASXL1 repression were identified, notably including the posterior HOXA cluster, known to contribute to myeloid transformation.

The generation of a mouse model for conditional deletion of Asxl1 has allowed further understanding the in vivo effects of ASXL1 loss. Whereas constitutive loss of Asxl1 resulted in severe developmental abnormalities, hematopoietic-specific deletion of the gene resembled characteristic features of human MDS. Additionally, serial transplantation of Asxl1-null hematopoietic cells caused lethal myeloid disorder at a shorter latency than primary Asxl1 knockout (KO) mice. Interestingly, reduces hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal caused by Asxl1 deletion, was reversed by concomitant deletion of Tet2, that is commonly co-mutated with ASXL1 in MDS patients. Moreover, the phenotype of compound Asxl1/Tet2 deletion was MDS with hastened death in comparison to single-gene KO mice [74].

In addition to interactions with PRC2, ASXL1 is also an essential cofactor for the nuclear deubiquitinase enzyme BAP1. BAP1 and ASXL1 function together to deubiquitinate the transcriptional regulator HCF-1 and the O-GlcNAc transferase enzyme OGT. Conditional deletion of Bap1 from the hematopoietic compartment of mice results in an MDS/MPN overlap syndrome [75]. Loss of HCF-1 and OGT is seen in BAP1 deficient cells, suggesting that ASXL1–BAP1 play an essential role in regulation of HCF-1 and OGT expression. Further work to understand the effects of ASXL1/BAP1 loss may yield therapeutic insight for myeloid malignancies.

5. Mutations in genes encoding histone proteins

Mutations in genes encoding histone proteins in cancer were first discovered in colon cancer (HIST1H1B, 4%) and Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL; HIST1H1C, 7%) through exome sequencing, but frequencies were low and no recurrent mutations were identified [76,77]. However, Wu et al. [78] and Schwartzentruber et al. [79] recently identified a high frequency of heterozygous mutations in HIST1H3B and H3F3A in a subtype of pediatric glioma, diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG). H3F3A mutations were reported in 78% of DIPG and 22–31% of other pediatric glioblastoms (GBMs) whereas HIST1H3B mutations were almost solely reported in DIPG (18%). Interestingly, these mutations occur at amino acid residues K27M and G34 (G/R, G/V), a residue critical for post-translational modification through methylation and acetylation on H3K27 and H3K36. Several sporadic mutations at these residues were reported in osteosarcoma (G34W) and MDS (K27N) [80–82], but the vast majority of these mutations are found in pediatric high-grade gliomas, including central nervous system primitive neuroectodermal tumor (11%, G34R). H3F3A G34 mutations tend to co-occur with ATRX/DAXX, PDGFRA, and TP53 alterations, and are often exclusive with IDH1 Mutations [79,83].

Histone H3 K27 and G34 mutations are mutually exclusive, which implies a possible redundant function, as well as always heterozygous, which suggests that they might result in a gain-of-function. At the same time, K27M mutations predict worse overall survival in contrast to G34 and wildtype H3 patients, and are associated with younger patients [83–85]. Moreover, H3F3AK27-mutant GBMs occurs in midline of brain, whereas H3F3AG34 mutant GBMs tend to occur in the hemispheric area. In recent studies, K27 and G34 tumor samples exhibited separate methylation profiles associated with divergences in gene expression [79,83,86]. For example, H3F3AK27-mutant samples were associated with silencing of FOXG1 and MICA and elevated expression of PDGFRA, while H3F3AG34 – mutant samples were associated with silencing of OLIG1/2 [83,87]. Global DNA hypomethylation and globally reduced H3K27 di-/tri-methylation were seen at many loci in H3F3AK27M mutant patient samples and cell lines suggesting that these mutations functions in a dominant-negative manner [83,84,87,88]. In vitro overexpression of H3.3 K27M reduced H3K27me2/me3 levels by K27M mediated binding of EZH2 and SUZ12 and consequently inhibition of PRC2 [87,89], consistent with a dominant negative function of histone H3 mutations.

In contrast to studies of H3F3AK27 mutations, the mechanism behind H3F3A G34R/V induced tumorigenesis is less explored. G34R/V mutations appear to interfere with methylation at H3K36, and there are transcriptional differences between H3F3A G34 mutant and wildtype forms. Aberrant activation and repression of several known oncogenes is an important feature of H3.3 mutant tumors, and its understanding will help to identify additional subtypes and driver genes. An example of this is the recent identification of G34-induced MYCN activation in pediatric GBM cell line KNS42 [86]. Targeting this oncogene in H3F3AG34 mutated GBM patient could have vast therapeutic benefit.

5.1. MLL

The Mixed Lineage Leukemia (MLL) family of genes consists of 5 members (MLL1–5) which share a SET domain and plant homeodomain (PHD) which mediates interactions between specific proteins (See Fig. 2). While MLL5 is a distantly related member of the family, the SET domain of MLL1–4 encodes a specific H3K4 methyltransferase which positively regulates gene expression. MLL1–4 additionally share several structural characteristics, with MLL1–2 and MLL3–4 being highly related architecturally and functionally[90]. MLL1 (also named HRX, KMT2A or ALL1), located on 11q23, is implicated in over 50 translocation events which results in loss of the H3K4 methyltransferase domain. These translocations, found in ~10% of all human leukemia and most commonly in infant leukemia and therapy-related leukemia, identify a unique group of acute leukemia often associated with poor outcome [91]. Discoveries of missense and truncating MLL1 mutations in bladder, lung and breast carcinomas [41,92] suggest a tumor suppressive role for MLL1 in some solid tumors along with its dominant oncogene role in leukemias mentioned above [93].

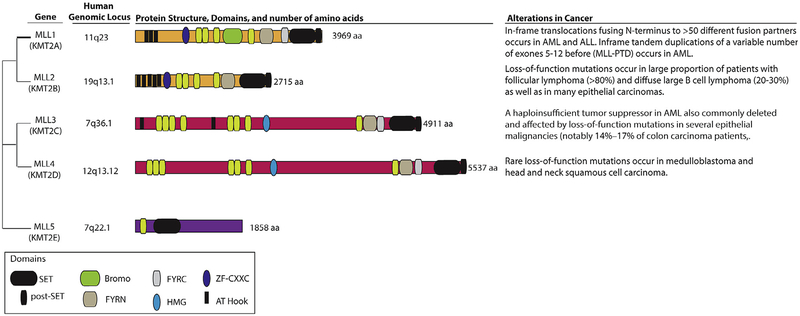

Fig. 2.

Shown above are the genomic loci of each MLL family member in humans. MLL1 and MLL2 (also known as KMT2A (gene ID: 4297) and KMT2B (gene ID: 9757), respectively) are highly homologous as are MLL3 and MLL4 (also known as KMT2C (gene ID: 58508) and KMT2D (gene ID: 8085), respectively). All four members (MLL1–4) share a common cluster of domains (PHD-FYRN-FYRC-SET-postSET domain), notably including a SET domain which imparts histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4) methyltransferase activity. In contrast to MLL1–4, MLL5 is more distantly related and contains only a PHD and a SET domain. The founding member of the family, MLL1, undergoes a translocation event fusing the N-terminus of MLL to one of >50 fusion partners. This translocation event removes the PHD domain but results in recruitment of the H3K79 methyltransferase DOT1L to the C-terminus of the chimeric protein. In addition to translocations, MLL1 also undergoes internal inframe tandem duplications which results in hyperactive H3K4 methyltransferase activity and promotes leukemogenesis in vivo. Somatic mutations and copy number alterations of MLL2–4 are quite common in cancer, but as shown above, the genes encoding these proteins are quite large calling into question whether all of the somatic mutations describe impact a functional impact on gene function. Ongoing functional studies attempting to characterize how loss of MLL members MLL2–4 contributes to tumorigenesis will be very enlightening.

The most frequent MLL1 translocations are MLL-AF4, MLL-AF9, MLL-AF10, and MLL-ENL, which result in recruitment of the Disruptor of Telomeric silencing 1-Like (DOT1L) to the fusion protein. These translocations cause loss of MLL1’s H3K4 methyltransferase activity but result in recruitment of the H3K79 methyltransferase activity from DOT1L to the fusion protein. Multiple studies have linked H3K79 methylation to positive transcriptional activation and as a unique mark for leukemogenic transformation [94]. Accordingly, interest has arisen in targeting DOT1L’s enzymatic activity to therapeutically treat MLL fusion malignancies. EPZ004777 is a methyltransferase inhibitor that was designed as a competitive inhibitor of S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), the universal donor of the methyltransferase enzymatic reaction. Nevertheless, it has preferential selectivity for DOT1L over other histone methyltransferases, and results in selective inhibition of leukemia cell lines with specific MLL1 translocations compared with cell lines without MLL1 translocations [95]. There is currently an ongoing phase I study of the DOT1L inhibitor EPZ5676 ( NCT01684150) for patients with relapsed/refractory hematologic malignancies to establish maximum tolerated dose and safety. The study is currently in a restricted/expansion phase for patients with MLL rearrangements or with partial tandem duplications in MLL.

In addition to DOT1L, MLL1 is dependent on a large number of protein–protein interactions for transcriptional regulation as well as leukemogenesis. One example is the interaction between MLL1 and PAFc, which plays a critical role initiating, elongating and terminating mRNA transcription as well as in histone H2B monoubiquitination. Through its interactions with PAFc, MLL1 interact with BRD3 and BRD4 [96]. Multiple investigators have converged recently on the therapeutic efficacy of small molecular inhibitors of the acetyl lysine binding pocket of BRD4 [97–99]. These molecules have been found to be efficacious in a diverse array of human disorders including patients with BRD4-NUT trans-located midline carcinomas [100], multiple myeloma [97] and AML [101]. Bromodomain inhibition as a therapeutic strategy is an important proof-of-concept of the utility of targeting protein–protein interactions to reverse epigenetic alterations in malignancies.

The second member of the family, MLL2 (also named KMT2D), is mutated in the majority of patients with follicular lymphoma (FL) as well as in almost third of DLBCL patients. After translocation t(14;18)(q32;q21), MLL2 mutation is the most common genetic alteration in FL, present in 89% of patients [76,102]. MLL2 mutations also appear to cluster with the GCB-like subtype of DLBCLs, where they are present in 24–32% of patients [103]. MLL2 mutations are associated with loss of MLL2 expression, yet their mechanism of contribution to lymphomagenesis remains unclear [104]. Further investigation of these mutations using both in vitro and in vivo methods will hopefully give insights into their role in lymphomagenesis.

MLL3 (also known as HALR or KMT2C), has been implicated as a tumor suppressor due to its frequent mutations in multiple types of tumors including hepatocellular carcinoma, fluke-associated cholangiocarcinoma, gastric cancer, colon cancer, transitional carcinoma of the bladder, and others [41,105–109]. MLL3 mutations are frequently nonsense or frameshift, resulting in a truncated protein lacking the SET domain [93]. In colon cancer, MLL3 mutations are reported in 14–17% of the cases and appear to be associated with increased microsatellite instability (MSI) through an unknown mechanism [110]. Examination of the expression of MLL3 mRNA in breast tumors revealed reduced expression in cancer tissue in 40% of the samples [111]. Recently, Chen et al. utilized RNAi and CRISPR/Cas9 approaches to validate that MLL3 is a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor in myeloid malignancies involving 7q deletions [112]. Moreover, this work identified that MLL3-deleted AML may be responsive to BET inhibition, a possibility that should be pursued in clinical trials of BET inhibitors in early phase investigation in AML.

5.2. NSD2

The Nuclear receptor-binding SET Domain (NSD) family consists of three members (NSD1–3) which share a SET domain. NSD2 (also known as WHSC1 or MMSET) is a histone methyltransferase which catalyzes mono or dimethylation of unmodified H3K36. Alterations of NSD2 are implicated in different cancers. Aberrant upregulation of this protein results from the t(4;14)(p16.3;q32) translocation found in 15–20% of MM patients [113]. Global increase in H3K36me2 levels with concomitant decrease in H3K27me3, which results from this upregulation of NSD2, appears to be the dominant mechanism driving NSD2 – associated oncogenic reprogramming [114]. Recently, recurrent NSD2 E1099K mutations were identified in 7.5% of pediatric ALL patients [115]. In vitro examination of this mutation revealed global increases in H3K36me2 levels and decreases in H3K27me3, as seen in the overexpression of the enzyme in MM [116]. These discoveries suggest NSD2 as a potential target for development of targeted epigenetic therapy.

Another H3K36 methyltransferase that was implicated with ALL is the H3K36 trimethylase SETD2, which is also recurrently mutated in clear cell renal cell carcinoma, gliomas and breast cancer. The mutations recognized so far in this gene are truncation alterations resulted from frameshift or nonsense mutations [93]. In addition, Mar et al. [117] recently identified enrichment of SETD2 mutations in pediatric ALL at relapse. This suggests involvement of SETD2 mutations in chemotherapy resistance, and warrants further studies of this gene and its mutation in the context of ALL.

5.3. CREBPP and EP300

CREB-binding protein (CREBBP) and E1A binding protein p300 (EP300) are highly homologous transcriptional coactivators with multiple functions in development and heamatopoiesis. They interact with diverse range of transcription factors, acetylate his-tones and other proteins (such as P53, Rb, and E2F) and affect protein turnover [118,119]. Mutations in CREBPP and EP300, which are thought to result in their inactivation, are implicated in a variety of cancers. These mutations are mutually exclusive, and for the most part heterozygous which imply haploinsufficiency of these tumor suppressors. CREBBP mutations have been described in almost third of the patients in several lymphomas (FL, DLBCL, NHL), and in a lower, yet significant, percentage of patients with lymphoid leukemias and epithelial carcinomas. Mutations in EP300 were somewhat less frequent but also described in these same disease entities [41,46,76,120–122]. The oncogenic mechanism of these mutations is not yet clear, but as the most frequently mutated region in both proteins is the shared lysine acetyltransferase domain which catalyzes acetylation of histones and other essential proteins, aberrant acetyltransferase activity may be a key feature. In vitro studies demonstrated reduced H3K18 acetylation, as well as decreased ability to acetylate P53 and BCL6, in CREBBP/EP300-mutated cells [121,122]. Though both CREBPP and EP300, and their association to cancers, were identified long ago, the effect of these mutations on cancer biology is still being revealed. Due to their multiple functions and diverse interactions, many mechanisms may play a role in the different mutations’ effects, some may not be through epigenetic mechanisms.

6. Conclusion

In the last decade, recurrent mutations in nearly every chromatin regulatory complex have been identified in cancer patients. This includes loss- and gain-of-function mutations in genes encoding DNA methylating enzymes, the DNA demethylation machinery, enzymatic complexes which enzymatically modify chromatin, the histone proteins themselves, and proteins which bind to modifications in chromatin. In clear cases of gain-of-function mutations in enzymes, several clinical-grade mutant-selective inhibitors have already rapidly been developed and entered early phase clinical trials. Future efforts to integrate functional genetic studies with epigenomic and transcriptomic profiling may help to delineate genetic targets responsible for malignant transformation following perturbations in a large host of additional epigenetic modifiers.

References

- [1].Ley TJ, Ding L, Walter MJ, McLellan MD, Lamprecht T, Larson DE, Kandoth C, Payton JE, Baty J, Welch J, Harris CC, Lichti CF, Townsend RR, Fulton RS, Dooling DJ, Koboldt DC, Schmidt H, Zhang Q, Osborne JR, Lin L, O’Laughlin M, McMichael JF, Delehaunty KD, McGrath SD, Fulton LA,Magrini VJ, Vickery TL, Hundal J, Cook LL, Conyers JJ, Swift GW, Reed JP, Alldredge PA, Wylie T, Walker J, Kalicki J, Watson MA, Heath S, Shannon WD, Varghese N, Nagarajan R, Westervelt P, Tomasson MH, Link DC, Graubert TA, DiPersio JF, Mardis ER, Wilson RK, DNMT3A mutations in acute myeloid leukemia, N. Engl. J. Med 363 (2010) 2424–2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Yamashita Y, Yuan J, Suetake I, Suzuki H, Ishikawa Y, Choi YL, Ueno T, Soda M, Hamada T, Haruta H, Takada S, Miyazaki Y, Kiyoi H, Ito E, Naoe T, Tomonaga M, Toyota M, Tajima S, Iwama A, Mano H, Array-based genomic resequencing of human leukemia, Oncogene 29 (2010) 3723–3731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Marcucci G, Metzeler KH, Schwind S, Becker H, Maharry K, Mrozek K, Radmacher MD, Kohlschmidt J, Nicolet D, Whitman SP, Wu YZ, Powell BL, Carter TH, Kolitz JE, Wetzler M, Carroll AJ, Baer MR, Moore JO, Caligiuri MA, Larson RA, Bloomfield CD, Age-related prognostic impact of different types of DNMT3A mutations in adults with primary cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia, J. Clin. Oncol 30 (2012) 742–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Thiede C, Mutant DNMT3A: teaming up to transform, Blood 119 (2012) 5615–5617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Yan XJ, Xu J, Gu ZH, Pan CM, Lu G, Shen Y, Shi JY, Zhu YM, Tang L, Zhang XW, Liang WX, Mi JQ, Song HD, Li KQ, Chen Z, Chen SJ, Exome sequencing identifies somatic mutations of DNA methyltransferase gene DNMT3A in acute monocytic leukemia, Nat. Genet 43 (2011) 309–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Thol F, Damm F, Ludeking A, Winschel C, Wagner K, Morgan M, Yun H, Gohring G, Schlegelberger B, Hoelzer D, Lubbert M, Kanz L, Fiedler W, Kirchner H, Heil G, Krauter J, Ganser A, Heuser M, Incidence and prognostic influence of DNMT3A mutations in acute myeloid leukemia, J. Clin. Oncol 29 (2011) 2889–2896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Xu J, Wang YY, Dai YJ, Zhang W, Zhang WN, Xiong SM, Gu ZH, Wang KK, Zeng R, Chen Z, Chen SJ, DNMT3A Arg882 mutation drives chronic myelomonocytic leukemia through disturbing gene expression/DNA methylation in hematopoietic cells, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111 (2014) 2620–2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kim SJ, Zhao H, Hardikar S, Singh AK, Goodell MA, Chen T, A DNMT3A mutation common in AML exhibits dominant-negative effects in murine ES cells, Blood 122 (2013) 4086–4089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Russler-Germain DA, Spencer DH, Young MA, Lamprecht TL, Miller CA, Fulton R, Meyer MR, Erdmann-Gilmore P, Townsend RR, Wilson RK, Ley TJ, The R882H DNMT3A mutation associated with AML dominantly inhibits wild-type DNMT3A by blocking its ability to form active tetramers, Cancer Cell 25 (2014) 442–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ono R, Taki T, Taketani T, Taniwaki M, Kobayashi H, Hayashi Y, LCX, leukemia-associated protein with a CXXC domain, is fused to MLL in acute myeloid leukemia with trilineage dysplasia having t(10;11)(q22;q23), Cancer Res 62 (2002) 4075–4080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Tahiliani M, Koh KP, Shen Y, Pastor WA, Bandukwala H, Brudno Y, Agarwal S, Iyer LM, Liu DR, Aravind L, Rao A, Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1, Science 324 (2009) 930–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ficz G, Branco MR, Seisenberger S, Santos F, Krueger F, Hore TA, Marques CJ, Andrews S, Reik W, Dynamic regulation of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mouse ES cells and during differentiation, Nature 473 (2011) 398–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wu H, Zhang Y, Tet1 and 5-hydroxymethylation: a genome-wide view in mouse embryonic stem cells, Cell Cycle 10 (2011) 2428–2436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Patel JP, Gonen M, Figueroa ME, Fernandez H, Sun Z, Racevskis J, Van Vlierberghe P, Dolgalev I, Thomas S, Aminova O, Huberman K, Cheng J, Viale A, Socci ND, Heguy A, Cherry A, Vance G, Higgins RR, Ketterling RP, Gallagher RE, Litzow M, van den Brink MR, Lazarus HM, Rowe JM, Luger S, Ferrando A, Paietta E, Tallman MS, Melnick A, Abdel-Wahab O, Levine RL, Prognostic relevance of integrated genetic profiling in acute myeloid leukemia, N. Engl. J. Med 366 (2012) 1079–1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Shen Y, Zhu YM, Fan X, Shi JY, Wang QR, Yan XJ, Gu ZH, Wang YY, Chen B, Jiang CL, Yan H, Chen FF, Chen HM, Chen Z, Jin J, Chen SJ, Gene mutation patterns and their prognostic impact in a cohort of 1185 patients with acute myeloid leukemia, Blood 118 (2011) 5593–5603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Metzeler KH, Maharry K, Radmacher MD, Mrozek K, Margeson D, Becker H, Curfman J, Holland KB, Schwind S, Whitman SP, Wu YZ, Blum W, Powell BL, Carter TH, Wetzler M, Moore JO, Kolitz JE, Baer MR, Carroll AJ, Larson RA, Caligiuri MA, Marcucci G, Bloomfield CD, TET2 mutations improve the new European LeukemiaNet risk classification of acute myeloid leukemia: a Cancer and Leukemia Group B study, J. Clin. Oncol 29 (2011) 1373–1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Chou WC, Chou SC, Liu CY, Chen CY, Hou HA, Kuo YY, Lee MC, Ko BS, Tang JL, Yao M, Tsay W, Wu SJ, Huang SY, Hsu SC, Chen YC, Chang YC, Kuo YY, Kuo KT, Lee FY, Liu MC, Liu CW, Tseng MH, Huang CF, Tien HF, TET2 mutation is an unfavorable prognostic factor in acute myeloid leukemia patients with intermediate-risk cytogenetics, Blood 118 (2011) 3803–3810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ko M, Huang Y, Jankowska AM, Pape UJ, Tahiliani M, Bandukwala HS, An J, Lamperti ED, Koh KP, Ganetzky R, Liu XS, Aravind L, Agarwal S, Maciejewski JP, Rao A, Impaired hydroxylation of 5-methylcytosine in myeloid cancers with mutant TET2, Nature 468 (2010) 839–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Figueroa ME, Abdel-Wahab O, Lu C, Ward PS, Patel J, Shih A, Li Y, Bhagwat N, Vasanthakumar A, Fernandez HF, Tallman MS, Sun Z, Wolniak K, Peeters JK, Liu W, Choe SE, Fantin VR, Paietta E, Lowenberg B, Licht JD,Godley LA, Delwel R, Valk PJ, Thompson CB, Levine RL, Melnick A, Leukemic IDH1 and IDH2 mutations result in a hypermethylation phenotype, disrupt TET2 function, and impair hematopoietic differentiation, Cancer Cell 18 (2010) 553–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Moran-Crusio K, Reavie L, Shih A, Abdel-Wahab O, Ndiaye-Lobry D, Lobry C, Figueroa ME, Vasanthakumar A, Patel J, Zhao X, Perna F, Pandey S, Madzo J, Song C, Dai Q, He C, Ibrahim S, Beran M, Zavadil J, Nimer SD, Melnick A, Godley LA, Aifantis I, Levine RL, Tet2 loss leads to increased hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and myeloid transformation, Cancer Cell 20 (2011) 11–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ko M, Bandukwala HS, An J, Lamperti ED, Thompson EC, Hastie R, Tsangaratou A, Rajewsky K, Koralov SB, Rao A, Ten-Eleven-Translocation 2 (TET2) negatively regulates homeostasis and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells in mice, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108 (2011) 14566–14571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Quivoron C, Couronne L, Della Valle V., Lopez CK, Plo I, Wagner-Ballon O,Do Cruzeiro M, Delhommeau F, Arnulf B, Stern MH, Godley L, Opolon P, Tilly H, Solary E, Duffourd Y, Dessen P, Merle-Beral H, Nguyen-Khac F, Fontenay M, Vainchenker W, Bastard C, Mercher T, Bernard OA, TET2 inactivation results in pleiotropic hematopoietic abnormalities in mouse and is a recurrent event during human lymphomagenesis, Cancer Cell 20 (2011) 25–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Green CL, Evans CM, Hills RK, Burnett AK, Linch DC, Gale RE, The prognostic significance of IDH1 mutations in younger adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia is dependent on FLT3/ITD status, Blood 116 (2010) 2779–2782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Green CL, Evans CM, Zhao L, Hills RK, Burnett AK, Linch DC, Gale RE, The prognostic significance of IDH2 mutations in AML depends on the location of the mutation, Blood 118 (2011) 409–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Dang L, White DW, Gross S, Bennett BD, Bittinger MA, Driggers EM, Fantin VR, Jang HG, Jin S, Keenan MC, Marks KM, Prins RM, Ward PS, Yen KE, Liau LM, Rabinowitz JD, Cantley LC, Thompson CB, Vander Heiden M.G., Su SM, Cancer-associated IDH1 mutations produce 2-hydroxyglutarate, Nature 462 (2009) 739–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ward PS, Patel J, Wise DR, Abdel-Wahab O, Bennett BD, Coller HA, Cross JR, Fantin VR, Hedvat CV, Perl AE, Rabinowitz JD, Carroll M, Su SM, Sharp KA, Levine RL, Thompson CB, The common feature of leukemia-associated IDH1 and IDH2 mutations is a neomorphic enzyme activity converting alpha-ketoglutarate to 2-hydroxyglutarate, Cancer Cell 17 (2010) 225–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Chowdhury R, Yeoh KK, Tian YM, Hillringhaus L, Bagg EA, Rose NR, Leung IK, Li XS, Woon EC, Yang M, McDonough MA, King ON, Clifton IJ, Klose RJ, Claridge TD, Ratcliffe PJ, Schofield CJ, Kawamura A, The oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate inhibits histone lysine demethylases, EMBO Rep 12 (2011) 463–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Rohle D, Popovici-Muller J, Palaskas N, Turcan S, Grommes C, Campos C, Tsoi J, Clark O, Oldrini B, Komisopoulou E, Kunii K, Pedraza A, Schalm S, Silverman L, Miller A, Wang F, Yang H, Chen Y, Kernytsky A, Rosenblum MK,Liu W, Biller SA, Su SM, Brennan CW, Chan TA, Graeber TG, Yen KE, Mellinghoff IK, An inhibitor of mutant IDH1 delays growth and promotes differentiation of glioma cells, Science 340 (2013) 626–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Wang F, Travins J, DeLaBarre B, Penard-Lacronique V, Schalm S, Hansen E,Straley K, Kernytsky A, Liu W, Gliser C, Yang H, Gross S, Artin E, Saada V, Mylonas E, Quivoron C, Popovici-Muller J, Saunders JO, Salituro FG, Yan S, Murray S, Wei W, Gao Y, Dang L, Dorsch M, Agresta S, Schenkein DP, Biller SA, Su SM, de Botton S, Yen KE, Targeted inhibition of mutant IDH2 in leukemia cells induces cellular differentiation, Science 340 (2013) 622–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kats LM, Reschke M, Taulli R, Pozdnyakova O, Burgess K, Bhargava P, Straley K, Karnik R, Meissner A, Small D, Su SM, Yen K, Zhang J, Pandolfi PP, Proto-oncogenic role of mutant IDH2 in leukemia initiation and maintenance, Cell Stem Cell 14 (2014) 329–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Stein MTE, Pollyea DA, Flinn IW, Fathi AT, Stone RM, Levine RL, Agresta S, Schenkein D, Yang H, Fan B, Yen K, De Botton S, Clinical safety and activity in a phase I trial of AG-221, a first in class, potent inhibitor of the IDH2-mutant protein, in patients with IDH2 mutant positive advanced hematologic malignancies (2014) (Abstract CT103). [Google Scholar]

- [32].Klose RJ, Zhang Y, Regulation of histone methylation by demethylimination and demethylation, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 8 (2007) 307–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Trojer P, Reinberg D, Histone lysine demethylases and their impact on epigenetics, Cell 125 (2006) 213–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Agger K, Cloos PA, Christensen J, Pasini D, Rose S, Rappsilber J, Issaeva I, Canaani E, Salcini AE, Helin K, UTX and JMJD3 are histone H3K27 demethylases involved in HOX gene regulation and development, Nature 449 (2007) 731–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].De Santa F, Totaro MG, Prosperini E, Notarbartolo S, Testa G, Natoli G, The histone H3 lysine-27 demethylase Jmjd3 links inflammation to inhibition of polycomb-mediated gene silencing, Cell 130 (2007) 1083–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Van der Meulen J, Speleman F, Van Vlierberghe P, The H3K27me3 demethylase UTX in normal development and disease, Epigenetics 9 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Lederer D, Grisart B, Digilio MC, Benoit V, Crespin M, Ghariani SC, Maystadt I, Dallapiccola B, Verellen-Dumoulin C, Deletion of KDM6A, a histone demethylase interacting with MLL2, in three patients with Kabuki syndrome, Am. J. Hum. Genet 90 (2012) 119–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].van Haaften G, Dalgliesh GL, Davies H, Chen L, Bignell G, Greenman C, Edkins S, Hardy C, O’Meara S, Teague J, Butler A, Hinton J, Latimer C, Andrews J, Barthorpe S, Beare D, Buck G, Campbell PJ, Cole J, Forbes S, Jia M, Jones D, Kok CY, Leroy C, Lin ML, McBride DJ, Maddison M, Maquire S,McLay K, Menzies A, Mironenko T, Mulderrig L, Mudie L, Pleasance E, Shepherd R, Smith R, Stebbings L, Stephens P, Tang G, Tarpey PS, Turner R, Turrell K, Varian J, West S, Widaa S, Wray P, Collins VP, Ichimura K, Law S, Wong J, Yuen ST, Leung SY, Tonon G, DePinho RA, Tai YT, Anderson KC, Kahnoski RJ, Massie A, Khoo SK, Teh BT, Stratton MR, Futreal PA, Somatic mutations of the histone H3K27 demethylase gene UTX in human cancer, Nat. Genet 41 (2009) 521–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].De Keersmaecker K, Atak ZK, Li N, Vicente C, Patchett S, Girardi T, Gianfelici V, Geerdens E, Clappier E, Porcu M, Lahortiga I, Luca R, Yan J, Hulselmans G, Vranckx H, Vandepoel R, Sweron B, Jacobs K, Mentens N, Wlodarska I, Cauwelier B, Cloos J, Soulier J, Uyttebroeck A, Bagni C, Hassan BA, Vandenberghe P, Johnson AW, Aerts S, Cools J, Exome sequencing identifies mutation in CNOT3 and ribosomal genes RPL5 and RPL10 in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Nat. Genet 45 (2013) 186–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Chapman MA, Lawrence MS, Keats JJ, Cibulskis K, Sougnez C, Schinzel AC, Harview CL, Brunet JP, Ahmann GJ, Adli M, Anderson KC, Ardlie KG, Auclair D, Baker A, Bergsagel PL, Bernstein BE, Drier Y, Fonseca R, Gabriel SB, Hofmeister CC, Jagannath S, Jakubowiak AJ, Krishnan A, Levy J, Liefeld T, Lonial S, Mahan S, Mfuko B, Monti S, Perkins LM, Onofrio R, Pugh TJ, Rajkumar SV, Ramos AH, Siegel DS, Sivachenko A, Stewart AK, Trudel S, Vij R, Voet D, Winckler W, Zimmerman T, Carpten J, Trent J, Hahn WC, Garraway LA, Meyerson M, Lander ES, Getz G, Golub TR, Initial genome sequencing and analysis of multiple myeloma, Nature 471 (2011) 467–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Gui Y, Guo G, Huang Y, Hu X, Tang A, Gao S, Wu R, Chen C, Li X, Zhou L,He M, Li Z, Sun X, Jia W, Chen J, Yang S, Zhou F, Zhao X, Wan S, Ye R, Liang C, Liu Z, Huang P, Liu C, Jiang H, Wang Y, Zheng H, Sun L, Liu X, Jiang Z, Feng D, Chen J, Wu S, Zou J, Zhang Z, Yang R, Zhao J, Xu C, Yin W, Guan Z, Ye J, Zhang H, Li J, Kristiansen K, Nickerson ML, Theodorescu D, Li Y,Zhang X, Li S, Wang J, Yang H, Wang J, Cai Z, Frequent mutations of chromatin remodeling genes in transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder, Nat. Genet 43 (2011) 875–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Jones DT, Jager N, Kool M, Zichner T, Hutter B, Sultan M, Cho YJ, Pugh TJ,Hovestadt V, Stutz AM, Rausch T, Warnatz HJ, Ryzhova M, Bender S, Sturm D, Pleier S, Cin H, Pfaff E, Sieber L, Wittmann A, Remke M, Witt H, Hutter S, Tzaridis T, Weischenfeldt J, Raeder B, Avci M, Amstislavskiy V, Zapatka M, Weber UD, Wang Q, Lasitschka B, Bartholomae CC, Schmidt M, von Kalle C, Ast V, Lawerenz C, Eils J, Kabbe R, Benes V, van Sluis P, Koster J,Volckmann R, Shih D, Betts MJ, Russell RB, Coco S, Tonini GP, Schuller U,Hans V, Graf N, Kim YJ, Monoranu C, Roggendorf W, Unterberg A, Herold-Mende C, Milde T, Kulozik AE, von Deimling A, Witt O, Maass E, Rossler J, Ebinger M, Schuhmann MU, Fruhwald MC, Hasselblatt M, Jabado N, Rutkowski S, von Bueren AO, Williamson D, Clifford SC, McCabe MG, Collins VP, Wolf S, Wiemann S, Lehrach H, Brors B, Scheurlen W,Felsberg J, Reifenberger G, Northcott PA, Taylor MD, Meyerson M, Pomeroy SL, Yaspo ML, Korbel JO, Korshunov A, Eils R, Pfister SM, Lichter P, Dissecting the genomic complexity underlying medulloblastoma, Nature 488 (2012) 100–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Pugh TJ, Weeraratne SD, Archer TC, Pomeranz Krummel D.A., Auclair D, Bochicchio J, Carneiro MO, Carter SL, Cibulskis K, Erlich RL, Greulich H, Lawrence MS, Lennon NJ, McKenna A, Meldrim J, Ramos AH, Ross MG, Russ C, Shefler E, Sivachenko A, Sogoloff B, Stojanov P, Tamayo P, Mesirov JP, Amani V, Teider N, Sengupta S, Francois JP, Northcott PA, Taylor MD, Yu F, Crabtree GR, Kautzman AG, Gabriel SB, Getz G, Jager N, Jones DT, Lichter P, Pfister SM, Roberts TM, Meyerson M, Pomeroy SL, Cho YJ, Medulloblastoma exome sequencing uncovers subtype-specific somatic mutations, Nature 488 (2012) 106–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Dalgliesh GL, Furge K, Greenman C, Chen L, Bignell G, Butler A, Davies H, Edkins S, Hardy C, Latimer C, Teague J, Andrews J, Barthorpe S, Beare D, Buck G, Campbell PJ, Forbes S, Jia M, Jones D, Knott H, Kok CY, Lau KW, Leroy C, Lin ML, McBride DJ, Maddison M, Maguire S, McLay K, Menzies A,Mironenko T, Mulderrig L, Mudie L, O’Meara S, Pleasance E, Rajasingham A,Shepherd R, Smith R, Stebbings L, Stephens P, Tang G, Tarpey PS, Turrell K, Dykema KJ, Khoo SK, Petillo D, Wondergem B, Anema J, Kahnoski RJ, Teh BT, Stratton MR, Futreal PA, Systematic sequencing of renal carcinoma reveals inactivation of histone modifying genes, Nature 463 (2010) 360–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Grasso CS, Wu YM, Robinson DR, Cao X, Dhanasekaran SM, Khan AP, Quist MJ, Jing X, Lonigro RJ, Brenner JC, Asangani IA, Ateeq B, Chun SY, Siddiqui J, Sam L, Anstett M, Mehra R, Prensner JR, Palanisamy N, Ryslik GA, Vandin F, Raphael BJ, Kunju LP, Rhodes DR, Pienta KJ, Chinnaiyan AM, Tomlins SA, The mutational landscape of lethal castration-resistant prostate cancer, Nature 487 (2012) 239–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Ho AS, Kannan K, Roy DM, Morris LG, Ganly I, Katabi N, Ramaswami D, Walsh LA, Eng S, Huse JT, Zhang J, Dolgalev I, Huberman K, Heguy A, Viale A, Drobnjak M, Leversha MA, Rice CE, Singh B, Iyer NG, Leemans CR,Bloemena E, Ferris RL, Seethala RR, Gross BE, Liang Y, Sinha R, Peng L, Raphael BJ, Turcan S, Gong Y, Schultz N, Kim S, Chiosea S, Shah JP, Sander C, Lee W, Chan TA, The mutational landscape of adenoid cystic carcinoma, Nat. Genet 45 (2013) 791–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Ross JS, Wang K, Al-Rohil RN, Nazeer T, Sheehan CE, Otto GA, He J, Palmer G, Yelensky R, Lipson D, Ali S, Balasubramanian S, Curran JA, Garcia L, Mahoney K, Downing SR, Hawryluk M, Miller VA, Stephens PJ, Advanced urothelial carcinoma: next-generation sequencing reveals diverse genomic alterations and targets of therapy, Mod. Pathol 27 (2014) 271–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Kruidenier L, Chung CW, Cheng Z, Liddle J, Che K, Joberty G, Bantscheff M, Bountra C, Bridges A, Diallo H, Eberhard D, Hutchinson S, Jones E, Katso R, Leveridge M, Mander PK, Mosley J, Ramirez-Molina C, Rowland P, Schofield CJ, Sheppard RJ, Smith JE, Swales C, Tanner R, Thomas P, Tumber A, Drewes G, Oppermann U, Patel DJ, Lee K, Wilson DM, A selective jumonji H3K27 demethylase inhibitor modulates the proinflammatory macrophage response, Nature 488 (2012) 404–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Margueron R, Reinberg D, The Polycomb complex PRC2 and its mark in life, Nature 469 (2011) 343–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Lewis EB, A gene complex controlling segmentation in Drosophila, Nature 276 (1978) 565–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Morin RD, Johnson NA, Severson TM, Mungall AJ, An J, Goya R, Paul JE, Boyle M, Woolcock BW, Kuchenbauer F, Yap D, Humphries RK, Griffith OL, Shah S, Zhu H, Kimbara M, Shashkin P, Charlot JF, Tcherpakov M,Corbett R, Tam A, Varhol R, Smailus D, Moksa M, Zhao Y, Delaney A, Qian H, Birol I, Schein J, Moore R, Holt R, Horsman DE, Connors JM, Jones S, Aparicio S, Hirst M, Gascoyne RD, Marra MA, Somatic mutations altering EZH2 (Tyr641) in follicular and diffuse large B-cell lymphomas of germinal-center origin, Nat. Genet 42 (2010) 181–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Sneeringer CJ, Scott MP, Kuntz KW, Knutson SK, Pollock RM, Richon VM, Copeland RA, Coordinated activities of wild-type plus mutant EZH2 drive tumor-associated hypertrimethylation of lysine 27 on histone H3 (H3K27) in human B-cell lymphomas, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107 (2010) 20980–20985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Yap DB, Chu J, Berg T, Schapira M, Cheng SW, Moradian A, Morin RD, Mungall AJ, Meissner B, Boyle M, Marquez VE, Marra MA, Gascoyne RD, Humphries RK, Arrowsmith CH, Morin GB, Aparicio SA, Somatic mutations at EZH2 Y641 act dominantly through a mechanism of selectively altered PRC2 catalytic activity, to increase H3K27 trimethylation, Blood 117 (2011) 2451–2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Majer CR, Jin L, Scott MP, Knutson SK, Kuntz KW, Keilhack H, Smith JJ, Moyer MP, Richon VM, Copeland RA, Wigle TJ, A687V EZH2 is a gain-of-function mutation found in lymphoma patients, FEBS Lett 586 (2012) 3448–3451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].McCabe MT, Graves AP, Ganji G, Diaz E, Halsey WS, Jiang Y, Smitheman KN, Ott HM, Pappalardi MB, Allen KE, Chen SB, Della Pietra A. 3rd, Dul E 3rd, Hughes AM, Gilbert SA, Thrall SH, Tummino PJ, Kruger RG, Brandt M, Schwartz B, Creasy CL , Mutation of A677 in histone methyltransferase EZH2 in human B-cell lymphoma promotes hypertrimethylation of histone H3 on lysine 27 (H3K27), Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109 (2012) 2989–2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Beguelin W, Popovic R, Teater M, Jiang Y, Bunting KL, Rosen M, Shen H, Yang SN, Wang L, Ezponda T, Martinez-Garcia E, Zhang H, Zheng Y, Verma SK, McCabe MT, Ott HM, Van Aller GS, Kruger RG, Liu Y, McHugh CF, Scott DW, Chung YR, Kelleher N, Shaknovich R, Creasy CL, Gascoyne RD, Wong KK, Cerchietti L, Levine RL, Abdel-Wahab O, Licht JD, Elemento O, Melnick AM, EZH2 is required for germinal center formation and somatic EZH2 mutations promote lymphoid transformation, Cancer Cell 23 (2013) 677–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Ernst T, Chase AJ, Score J, Hidalgo-Curtis CE, Bryant C, Jones AV, Waghorn K, Zoi K, Ross FM, Reiter A, Hochhaus A, Drexler HG, Duncombe A, Cervantes F, Oscier D, Boultwood J, Grand FH, Cross NC, Inactivating mutations of the histone methyltransferase gene EZH2 in myeloid disorders, Nat. Genet 42 (2010) 722–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Ntziachristos P, Tsirigos A, Van Vlierberghe P, Nedjic J, Trimarchi T, Flaherty MS, Ferres-Marco D, da Ros V, Tang Z, Siegle J, Asp P, Hadler M, Rigo I, De Keersmaecker K, Patel J, Huynh T, Utro F, Poglio S, Samon JB, Paietta E, Racevskis J, Rowe JM, Rabadan R, Levine RL, Brown S, Pflumio F, Dominguez M, Ferrando A, Aifantis I, Genetic inactivation of the polycomb repressive complex 2 in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Nat. Med 18 (2012) 298–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Zhang J, Ding L, Holmfeldt L, Wu G, Heatley SL, Payne-Turner D, Easton J, Chen X, Wang J, Rusch M, Lu C, Chen SC, Wei L, Collins-Underwood JR, Ma J, Roberts KG, Pounds SB, Ulyanov A, Becksfort J, Gupta P, Huether R, Kriwacki RW, Parker M, McGoldrick DJ, Zhao D, Alford D, Espy S, Bobba KC, Song G, Pei D, Cheng C, Roberts S, Barbato MI, Campana D, Coustan-Smith E, Shurtleff SA, Raimondi SC, Kleppe M, Cools J, Shimano KA, Hermiston ML, Doulatov S, Eppert K, Laurenti E, Notta F, Dick JE, Basso G, Hunger SP, Loh ML, Devidas M, Wood B, Winter S, Dunsmore KP, Fulton RS, Fulton LL, Hong X, Harris CC, Dooling DJ, Ochoa K, Johnson KJ, Obenauer JC, Evans WE, Pui CH, Naeve CW, Ley TJ, Mardis ER, Wilson RK, Downing JR, Mullighan CG, The genetic basis of early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, Nature 481 (2012) 157–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Simon C, Chagraoui J, Krosl J, Gendron P, Wilhelm B, Lemieux S, Boucher G, Chagnon P, Drouin S, Lambert R, Rondeau C, Bilodeau A, Lavallee S, Sauvageau M, Hebert J, Sauvageau G, A key role for EZH2 and associated genes in mouse and human adult T-cell acute leukemia, Genes Dev 26 (2012) 651–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Bejar R, Stevenson K, Abdel-Wahab O, Galili N, Nilsson B, Garcia-Manero G, Kantarjian H, Raza A, Levine RL, Neuberg D, Ebert BL, Clinical effect of point mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes, N. Engl. J. Med 364 (2011) 2496–2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Guglielmelli P, Biamonte F, Score J, Hidalgo-Curtis C, Cervantes F, Maffioli M, Fanelli T, Ernst T, Winkelman N, Jones AV, Zoi K, Reiter A, Duncombe A, Villani L, Bosi A, Barosi G, Cross NC, Vannucchi AM, EZH2 mutational status predicts poor survival in myelofibrosis, Blood 118 (2011) 5227–5234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Abdel-Wahab O, Pardanani A, Patel J, Wadleigh M, Lasho T, Heguy A, Beran M, Gilliland DG, Levine RL, Tefferi A, Concomitant analysis of EZH2 and ASXL1 mutations in myelofibrosis, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia and blast-phase myeloproliferative neoplasms, Leukemia 25 (2011) 1200–1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Bejar R, Stevenson KE, Caughey BA, Abdel-Wahab O, Steensma DP, Galili N, Raza A, Kantarjian H, Levine RL, Neuberg D, Garcia-Manero G, Ebert BL, Validation of a prognostic model and the impact of mutations in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes, J. Clin. Oncol 30 (2012) 3376–3382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Muto T, Sashida G, Oshima M, Wendt GR, Mochizuki-Kashio M, Nagata Y, Sanada M, Miyagi S, Saraya A, Kamio A, Nagae G, Nakaseko C, Yokote K, Shimoda K, Koseki H, Suzuki Y, Sugano S, Aburatani H, Ogawa S, Iwama A, Concurrent loss of Ezh2 and Tet2 cooperates in the pathogenesis of myelodysplastic disorders, J. Exp. Med 210 (2013) 2627–2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Brecqueville M, Cervera N, Adelaide J, Rey J, Carbuccia N, Chaffanet M, Mozziconacci MJ, Vey N, Birnbaum D, Gelsi-Boyer V, Murati A, Mutations and deletions of the SUZ12 polycomb gene in myeloproliferative neoplasms, Blood Cancer J 1 (2011) e33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Score J, Hidalgo-Curtis C, Jones AV, Winkelmann N, Skinner A, Ward D, Zoi K, Ernst T, Stegelmann F, Dohner K, Chase A, Cross NC, Inactivation of polycomb repressive complex 2 components in myeloproliferative and myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms, Blood 119 (2012) 1208–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Abdel-Wahab O, Adli M, LaFave LM, Gao J, Hricik T, Shih AH, Pandey S, Patel JP, Chung YR, Koche R, Perna F, Zhao X, Taylor JE, Park CY, Carroll M, Melnick A, Nimer SD, Jaffe JD, Aifantis I, Bernstein BE, Levine RL, ASXL1 mutations promote myeloid transformation through loss of PRC2-mediated gene repression, Cancer Cell 22 (2012) 180–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Gelsi-Boyer V, Trouplin V, Adelaide J, Bonansea J, Cervera N, Carbuccia N, Lagarde A, Prebet T, Nezri M, Sainty D, Olschwang S, Xerri L, Chaffanet M, Mozziconacci MJ, Vey N, Birnbaum D, Mutations of polycomb-associated gene ASXL1 in myelodysplastic syndromes and chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia, Br. J. Haematol 145 (2009) 788–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Metzeler KH, Becker H, Maharry K, Radmacher MD, Kohlschmidt J, Mrozek K, Nicolet D, Whitman SP, Wu YZ, Schwind S, Powell BL, Carter TH, Wetzler M, Moore JO, Kolitz JE, Baer MR, Carroll AJ, Larson RA, Caligiuri MA, Marcucci G, Bloomfield CD, ASXL1 mutations identify a high-risk subgroup of older patients with primary cytogenetically normal AML within the ELN Favorable genetic category, Blood 118 (2011) 6920–6929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Thol F, Friesen I, Damm F, Yun H, Weissinger EM, Krauter J, Wagner K, Chaturvedi A, Sharma A, Wichmann M, Gohring G, Schumann C, Bug G, Ottmann O, Hofmann WK, Schlegelberger B, Heuser M, Ganser A, Prognostic significance of ASXL1 mutations in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes, J. Clin. Oncol 29 (2011) 2499–2506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Boultwood J, Perry J, Pellagatti A, Fernandez-Mercado M, Fernandez-Santamaria C, Calasanz MJ, Larrayoz MJ, Garcia-Delgado M, Giagounidis A, Malcovati L, Della Porta M.G., Jadersten M, Killick S, Hellstrom-Lindberg E, Cazzola M, Wainscoat JS, Frequent mutation of the polycomb-associated gene ASXL1 in the myelodysplastic syndromes and in acute myeloid leukemia, Leukemia 24 (2010) 1062–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Jankowska AM, Makishima H, Tiu RV, Szpurka H, Huang Y, Traina F, Visconte V, Sugimoto Y, Prince C, O’Keefe C, Hsi ED, List A, Sekeres MA, Rao A, McDevitt MA, Maciejewski JP, Mutational spectrum analysis of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia includes genes associated with epigenetic regulation: UTX, EZH2, and DNMT3A, Blood 118 (2011) 3932–3941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Abdel-Wahab O, Gao J, Adli M, Dey A, Trimarchi T, Chung YR, Kuscu C, Hricik T, Ndiaye-Lobry D, Lafave LM, Koche R, Shih AH, Guryanova OA, Kim E, Li S, Pandey S, Shin JY, Telis L, Liu J, Bhatt PK, Monette S, Zhao X, Mason CE, Park CY, Bernstein BE, Aifantis I, Levine RL, Deletion of Asxl1 results in myelodysplasia and severe developmental defects in vivo, J. Exp. Med 210 (2013) 2641–2659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Dey A, Seshasayee D, Noubade R, French DM, Liu J, Chaurushiya MS, Kirkpatrick DS, Pham VC, Lill JR, Bakalarski CE, Wu J, Phu L, Katavolos P, LaFave LM, Abdel-Wahab O, Modrusan Z, Seshagiri S, Dong K, Lin Z, Balazs M, Suriben R, Newton K, Hymowitz S, Garcia-Manero G, Martin F, Levine RL, Dixit VM, Loss of the tumor suppressor BAP1 causes myeloid transformation, Science 337 (2012) 1541–1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Morin RD, Mendez-Lago M, Mungall AJ, Goya R, Mungall KL, Corbett RD, Johnson NA, Severson TM, Chiu R, Field M, Jackman S, Krzywinski M, Scott DW, Trinh DL, Tamura-Wells J, Li S, Firme MR, Rogic S, Griffith M, Chan S, Yakovenko O, Meyer IM, Zhao EY, Smailus D, Moksa M, Chittaranjan S, Rimsza L, Brooks-Wilson A, Spinelli JJ, Ben-Neriah S, Meissner B, Woolcock B, Boyle M, McDonald H, Tam A, Zhao Y, Delaney A, Zeng T, Tse K, Butterfield Y, Birol I, Holt R, Schein J, Horsman DE, Moore R, Jones SJ, Connors JM, Hirst M, Gascoyne RD, Marra MA, Frequent mutation of histone-modifying genes in non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Nature 476 (2011) 298–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Sjoblom T, Jones S, Wood LD, Parsons DW, Lin J, Barber TD, Mandelker D, Leary RJ, Ptak J, Silliman N, Szabo S, Buckhaults P, Farrell C, Meeh P, Markowitz SD, Willis J, Dawson D, Willson JK, Gazdar AF, Hartigan J, Wu L, Liu C, Parmigiani G, Park BH, Bachman KE, Papadopoulos N, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW, Velculescu VE, The consensus coding sequences of human breast and colorectal cancers, Science 314 (2006) 268–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Wu G, Broniscer A, McEachron TA, Lu C, Paugh BS, Becksfort J, Qu C, Ding L, Huether R, Parker M, Zhang J, Gajjar A, Dyer MA, Mullighan CG, Gilbertson RJ, Mardis ER, Wilson RK, Downing JR, Ellison DW, Zhang J, Baker SJ, Somatic histone H3 alterations in pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas and non-brainstem glioblastomas, Nat. Genet 44 (2012) 251–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Schwartzentruber J, Korshunov A, Liu XY, Jones DT, Pfaff E, Jacob K, Sturm D, Fontebasso AM, Quang DA, Tonjes M, Hovestadt V, Albrecht S, Kool M, Nantel A, Konermann C, Lindroth A, Jager N, Rausch T, Ryzhova M, Korbel JO, Hielscher T, Hauser P, Garami M, Klekner A, Bognar L, Ebinger M, Schuhmann MU, Scheurlen W, Pekrun A, Fruhwald MC, Roggendorf W, Kramm C, Durken M, Atkinson J, Lepage P, Montpetit A, Zakrzewska M, Zakrzewski K, Liberski PP, Dong Z, Siegel P, Kulozik AE, Zapatka M, Guha A, Malkin D, Felsberg J, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Ichimura K, Collins VP, Witt H, Milde T, Witt O, Zhang C, Castelo-Branco P, Lichter P, Faury D, Tabori U, Plass C, Majewski J, Pfister SM, Jabado N, Driver mutations in histone H3.3 and chromatin remodelling genes in paediatric glioblastoma, Nature 482 (2012) 226–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Attieh Y, Geng QR, Dinardo CD, Zheng H, Jia Y, Fang ZH, Gañán-Gómez I,Yang H, Wei Y, Kantarjian H, Garcia-Manero G, Low frequency of H3.3 mutations and upregulated DAXX expression in MDS, Blood 121 (19) (2013) 4009–4011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Gessi M, Gielen GH, Hammes J, Dörner E, Mühlen AZ, Waha A, Pietsch T, H3.3 G34R mutations in pediatric primitive neuroectodermal tumors of central nervous system (CNS-PNET) and pediatric glioblastomas: possible diagnostic and therapeutic implications?, J Neurooncol 112 (1) (2013) 67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Joseph CG, Hwang H, Jiao Y, Wood LD, Kinde I, Wu J, Mandahl N, Luo J, Hruban RH, Diaz LA Jr., He TC, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW, Mertens F, Papadopoulos N, Exomic analysis of myxoid liposarcomas, synovial sarcomas, and osteosarcomas, Genes Chromosomes Cancer 53 (1) (2014) 15–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Sturm D, Witt H, Hovestadt V, Khuong-Quang DA, Jones DT, Konermann C, Pfaff E, Tonjes M, Sill M, Bender S, Kool M, Zapatka M, Becker N, Zucknick M, Hielscher T, Liu XY, Fontebasso AM, Ryzhova M, Albrecht S, Jacob K, Wolter M, Ebinger M, Schuhmann MU, van Meter T, Fruhwald MC, Hauch H, Pekrun A, Radlwimmer B, Niehues T, von Komorowski G, Durken M, Kulozik AE, Madden J, Donson A, Foreman NK,Drissi R, Fouladi M, Scheurlen W, von Deimling A, Monoranu C, Roggendorf W, Herold-Mende C, Unterberg A, Kramm CM, Felsberg J, Hartmann C, Wiestler B, Wick W, Milde T, Witt O, Lindroth AM, Schwartzentruber J, Faury D, Fleming A, Zakrzewska M, Liberski PP, Zakrzewski K, Hauser P, Garami M, Klekner A, Bognar L, Morrissy S, Cavalli F, Taylor MD, van Sluis P, Koster J, Versteeg R, Volckmann R, Mikkelsen T, Aldape K, Reifenberger G, Collins VP, Majewski J, Korshunov A, Lichter P, Plass C, Jabado N, Pfister SM, Hotspot mutations in H3F3A and IDH1 define distinct epigenetic and biological subgroups of glioblastoma, Cancer Cell 22 (2012) 425–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Chan KM, Fang D, Gan H, Hashizume R, Yu C, Schroeder M, Gupta N, Mueller S, James CD, Jenkins R, Sarkaria J, Zhang Z, The histone H3.3K27M mutation in pediatric glioma reprograms H3K27 methylation and gene expression, Genes Dev 27 (2013) 985–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Khuong-Quang DA, Buczkowicz P, Rakopoulos P, Liu XY, Fontebasso AM,Bouffet E, Bartels U, Albrecht S, Schwartzentruber J, Letourneau L, Bourgey M, Bourque G, Montpetit A, Bourret G, Lepage P, Fleming A, Lichter P, Kool M, von Deimling A, Sturm D, Korshunov A, Faury D, Jones DT,Majewski J, Pfister SM, Jabado N, Hawkins C, K27M mutation in histone H3.3 defines clinically and biologically distinct subgroups of pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas, Acta Neuropathol 124 (2012) 439–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Bjerke L, Mackay A, Nandhabalan M, Burford A, Jury A, Popov S, Bax DA, Carvalho D, Taylor KR, Vinci M, Bajrami I, McGonnell IM, Lord CJ, Reis RM, Hargrave D, Ashworth A, Workman P, Jones C, Histone H3.3 mutations drive pediatric glioblastoma through upregulation of MYCN, Cancer Discov 22 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Bender S, Tang Y, Lindroth AM, Hovestadt V, Jones DT, Kool M, Zapatka M, Northcott PA, Sturm D, Wang W, Radlwimmer B, Hojfeldt JW, Truffaux N, Castel D, Schubert S, Ryzhova M, Seker-Cin H, Gronych J, Johann PD, Stark S, Meyer J, Milde T, Schuhmann M, Ebinger M, Monoranu CM, Ponnuswami A, Chen S, Jones C, Witt O, Collins VP, von Deimling A, Jabado N, Puget S, Grill J, Helin K, Korshunov A, Lichter P, Monje M, Plass C, Cho YJ, Pfister SM, Reduced H3K27me3 and DNA hypomethylation are major drivers of gene expression in K27M mutant pediatric high-grade gliomas, Cancer Cell 24 (2013) 660–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Lewis PW, Muller MM, Koletsky MS, Cordero F, Lin S, Banaszynski LA, Garcia BA, Muir TW, Becher OJ, Allis CD, Inhibition of PRC2 activity by a gain-of-function H3 mutation found in pediatric glioblastoma, Science 340 (2013) 857–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Chan KM, Han J, Fang D, Gan H, Zhang Z, A lesson learned from the H3.3K27M mutation found in pediatric glioma: a new approach to the study of the function of histone modifications in vivo?, Cell Cycle 12 (2013) 2546–2552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Liu H, Westergard TD, Hsieh JJ, MLL5 governs hematopoiesis: a step closer, Blood 113 (2009) 1395–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Krivtsov AV, Armstrong SA, MLL translocations, histone modifications and leukaemia stem-cell development, Nat. Rev. Cancer 7 (2007) 823–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Kan Z, Jaiswal BS, Stinson J, Janakiraman V, Bhatt D, Stern HM, Yue P, Haverty PM, Bourgon R, Zheng J, Moorhead M, Chaudhuri S, Tomsho LP, Peters BA, Pujara K, Cordes S, Davis DP, Carlton VE, Yuan W, Li L, Wang W, Eigenbrot C, Kaminker JS, Eberhard DA, Waring P, Schuster SC, Modrusan Z,Zhang Z, Stokoe D, de Sauvage FJ, Faham M, Seshagiri S, Diverse somatic mutation patterns and pathway alterations in human cancers, Nature 466 (2010) 869–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Roy DM, Walsh LA, Chan TA, Driver mutations of cancer epigenomes, Protein Cell 5 (2014) 265–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Chung YR, Schatoff E, Abdel-Wahab O, Epigenetic alterations in hematopoietic malignancies, Int. J. Hematol 96 (2012) 413–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Daigle SR, Olhava EJ, Therkelsen CA, Majer CR, Sneeringer CJ, Song J, Johnston LD, Scott MP, Smith JJ, Xiao Y, Jin L, Kuntz KW, Chesworth R, Moyer MP, Bernt KM, Tseng JC, Kung AL, Armstrong SA, Copeland RA, Richon VM, Pollock RM, Selective killing of mixed lineage leukemia cells by a potent small-molecule DOT1L inhibitor, Cancer Cell 20 (2012) 53–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Smith E, Lin C, Shilatifard A, The super elongation complex (SEC) and MLL in development and disease, Genes Dev 25 (2011) 661–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]