Abstract

Objective. To evaluate the impact of a six-week yoga and meditation intervention on college students’ stress perception, anxiety levels, and mindfulness skills.

Methods. College students participated in a six-week pilot program that consisted of a 60-minute vinyasa flow yoga class once weekly, followed by guided meditation delivered by trained faculty members at the University of Rhode Island College of Pharmacy. Students completed pre- and post-intervention questionnaires to evaluate changes in the following outcomes: stress levels, anxiety levels, and mindfulness skills. The questionnaire consisted of three self-reporting tools: the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), and the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ). Students’ scores on each were assessed to detect any changes from baseline using the numerical and categorical scales (low, medium, and high) for each instrument.

Results. Seventeen participants, aged 19 to 23 years, completed the study. Thirteen participants were female and four were male. Nine of the students were enrolled in the Doctor of Pharmacy program and eight were enrolled in other academic programs. Students’ anxiety and stress scores decreased significantly while their total mindfulness increased significantly. Changes in categorical data from pre- to post-intervention on the BAI and PSS were significant, with no students scoring in the “high” category for stress or anxiety on the post-intervention questionnaire.

Conclusion. Students experienced a reduction in stress and anxiety levels after completing a six-week yoga and meditation program preceding final examinations. Results suggest that adopting a mindfulness practice for as little as once per week may reduce stress and anxiety in college students. Administrators should consider including instruction in nonpharmacologic stress and anxiety reduction methods, within curricula in order to support student self-care.

Keywords: yoga, meditation, stress, anxiety, mindfulness, student

INTRODUCTION

Stress is defined as “a state of mental or emotional strain or tension resulting from adverse or very demanding circumstances.”1 Students enrolled in health professions programs have high levels of stress.2 Pharmacy students, specifically, have demonstrated an increased level of stress and decreased quality of life throughout their curricular programs.3-8 Nationally, stress among Americans is increasing. Stress may negatively affect health and wellness, leading to detrimental physical and emotional symptoms such as headaches, anxiety, and depression. In 2017, college-aged Americans reported higher levels of stress than older generations and often did not adequately address their stress through positive coping mechanisms.9 One positive modality that has demonstrated a reduction in pharmacy student stress is physical exercise.2

The word “yoga,” derived from the Sanskrit word yuj, translates to “yoking” or “union” in English. The practice is a union of the eight limbs of yoga, described by the scholar Patanjali, including pranayama (breathing), asana (movement), and dhyana (meditation).10 Yoga and meditation have become widely accepted as nonpharmacologic modalities for stress and anxiety reduction as well as general health.11-16 Meditation has been shown to improve attention and self-awareness in many populations, including college-aged students.11 Yoga’s effect on depression and anxiety has been studied repeatedly with medical and nursing students. Further, the majority of research on stress reduction and mindfulness with health care-related majors has been conducted on medical and nursing students.11,14,17 Most recently, a systematic review of the literature evaluated incorporating mindfulness-based interventions for medical, nursing, and psychology undergraduate students to reduce stress.18 However, research is lacking on the effects of a dual yoga and mindfulness practice for pharmacy students. The investigation described here was termed “SAMYAMA,” which stands for “Stress, Anxiety, and Mindfulness, a Yoga and Meditation Assessment.” Samyama is a Sanskrit word that describes a state in which the mind and body are unified in focus on the present moment, ie, mindfulness.

Yoga and meditative practices may provide a skillset to assist college students in their coping mechanisms, both in and out of the classroom. The objective of this pilot project was to evaluate the efficacy of a six-week yoga and meditation intervention on college students’ stress perception, anxiety levels, and mindfulness skills. The information gathered from our research assisted in designing curricular opportunities within a PharmD program to support students with coping mechanisms to navigate their academic and life stressors. We hypothesized that the dual intervention of yoga and meditation would demonstrate more benefit to students in a shorter timeframe than either practice separately.

METHODS

We conducted a 90-minute yoga and meditation intervention at the University of Rhode Island (URI) College of Pharmacy in spring 2017 during the last six weeks of the semester, immediately preceding final examinations, which is a period of time often associated with increased stress and anxiety among college students. The project was limited to no more than 20 students (10 pharmacy and 10 non-pharmacy) to ensure an appropriate teacher to student ratio, accommodate space issues, and assess for any baseline differences in stress, anxiety, and mindfulness between students enrolled in a highly structured doctorate program vs students enrolled in college majors with less rigorous demands. Recruitment was conducted via an electronic flyer posted on URI student social media pages and paper flyers posted throughout the campus library. Enrollment was on a first-come, first served basis for students ages 18 to 23 years with moderate levels of perceived stress and limited exposure to yoga and meditation, as assessed in the enrollment survey. Students were excluded from the program if they had completed a 200-hour yoga teacher training program (Registered Yoga Teacher or RYT 200, Yoga Alliance, Arlington, VA), prior certification in meditation instruction, or were pregnant. Participants did not receive any financial incentive. The first 20 applicable respondents were accepted into the program.

The intervention consisted of a once weekly, 60-minute vinyasa yoga class, followed by a 30-minute guided meditation practice. The yoga and meditation practices were held in a private classroom in the URI College of Pharmacy building and led by two pharmacy faculty members, one trained as an RYT 200 and the other certified as a Shambhala Path Meditation Instructor. Students were encouraged to bring their own yoga mats; however, the research team provided mats if needed. Using Google Forms, students completed the pre-intervention questionnaire on the first day of class and a post-intervention questionnaire on the last day of class to evaluate potential changes in stress levels, anxiety levels, and mindfulness skills. The intervention occurred during the last six weeks of the spring semester with the post-questionnaire delivered during the week of final examinations. The quantity of time devoted to meditation increased each week, beginning with 10 minutes and gradually increasing to 30 minutes by week six. A variety of meditative practices were presented, such as walking meditation and Shamatha (peaceful abiding).

The questionnaire was comprised of three validated, self-reporting inventories: the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), and the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ). The BAI self-reporting tool assesses the severity of generalized anxiety symptoms. This tool focuses on somatic symptoms of anxiety and has 21 items. Responses are based on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (severely) with a maximum total score of 63 points. Scores ranging from 0-21 indicated low anxiety, 22-35 indicated moderate anxiety, and 36 or higher indicated high anxiety. The BAI demonstrates internal consistency and convergence with other anxiety measurements, and has been tested in many populations, including college students.19-21 The PSS reports an individual’s experience of stress. The tool measures psychological manifestations of stress and is designed to assess “the degree to which individuals appraise situations in their lives as stressful.” Responses are collected using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 5 (very often). Scores ranging from 0-13 indicated low stress, 14-26 indicated moderate stress, and 27-40 indicated high stress. This research used the 10-item inventory, also known as the PSS-10.22,23 Last, the FFMQ, was used to assess student mindfulness, which included observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-judging of inner experience, and nonreactivity to inner experience.24 Responses were collected using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never or very rarely true) to 5 (very often or always true). The three self-reporting inventories were administered electronically via Google Forms to all participants pre- and post-intervention.

In our analyses, time-invariant confounding is subtracted out by the individual level differencing and each person serves as their own control. In this short follow-up period, secular trends are less of a concern. Because of the small sample size and paired outcomes for each participant, Wilcoxon signed rank tests and McNemar exact tests were performed to assess statistical differences between students’ pre- and post-intervention scores. All data analyses were performed using RStudio, Version 0.99.903, 2009-2016 (RStudio, Inc, Boston, MA)

The results for McNemar exact test were generated using SAS software, 2018 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). This project was approved by the University of Rhode Island Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Seventeen (85%) of the 20 students who volunteered to participate were retained for the duration of the study. The other three students were not able to attend every session because of scheduling issues, so they were not included in the analysis. The mean age of the participants was 20.7 years, with a range of 19 to 23 years. Thirteen participants were female (76%). The majority were third-year (35%) with nine of the students enrolled in the Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) program (53%) and eight enrolled in other programs at URI. Other programs represented included engineering, arts and sciences, environment and life sciences, education, business, and health studies. The majority of participants reported some level of previous yoga (88%) and meditation experience (77%). Pharmacy and nonpharmacy students were well matched, with pharmacy students reporting higher levels of stress and anxiety at baseline, though these numbers failed to reach significance (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants in a Study to Assess the Effect of Yoga and Meditation Sessions on College Students’ Stress, Anxiety, and Mindfulness

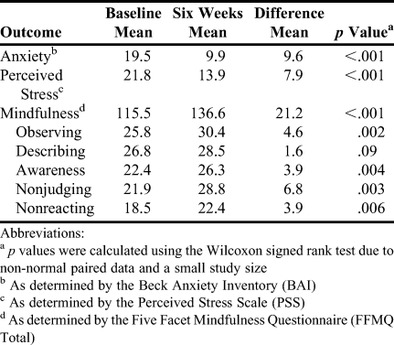

During the six-week study period, students’ anxiety and stress scores decreased while their total mindfulness scores increased (Tables 2 and 3). Students’ BAI scores dropped an average 9.6 points (Median = -9; 95% confidence interval (CI): -13.8, -5.3). Students’ PSS scores dropped an average 7.9 points (Median = -8; 95% CI: -11.8, -4.0). As for FFMQ scores, observing increased an average of 4.6 points (Median = 4.0; 95% CI = 2.0, 7.2;). The FFMQ scores for both acting with awareness and nonreactivity to inner experience increased 3.9 points (FFMQ-AwA: Median = 3.0; 95% CI = 1.7-6.1/FFMQ-NR: Median=4.0; 95% CI=1.8-6.1). The largest increase was seen in the score for non-judging of inner experience, with a mean increase of 6.8 points (Median=8.0; 95% CI=3.5-10.2). Categorical changes in pre- and post-intervention data from BAI and PSS were also significant (p=.008 and p=.03, respectively). No students were found to be in the high category for either stress and anxiety post intervention.

Table 2.

Mean Outcomes of Participants in a Study to Assess the Effect of Yoga and Meditation Sessions on College Students’ Stress, Anxiety, and Mindfulness as Determined by Standardized Measures (N=17)

Table 3.

Categorical Outcomes from Baseline to Post-Baseline Among Participants in a Study to Assess the Effect of Yoga and Meditation Sessions on College Students’ Stress, Anxiety, and Mindfulness

DISCUSSION

The objective of our pilot project was to evaluate the efficacy of a 6-week yoga and meditation intervention on college students’ stress perception, anxiety levels, and mindfulness skills. Given the high prevalence of stress among college-aged students, this project was implemented to assist our students in developing positive coping mechanisms or skillsets to navigate their academic and life stressors. Long term, students may be able to use these mindfulness skills to reduce their anxiety and stress, yielding improved academic success, reduced burnout, and increased empathy toward patients.11,17-19 The SAMYAMA project began six weeks before final examinations, which is historically a time of increased stress and anxiety among college students. The researchers sought to arm the students with mindfulness skills in preparation for this potential time of crisis. At the beginning of the project, approximately one-third of the students reported a high level of stress and anxiety; however, by the end, none reported high stress or anxiety. The post-intervention questionnaire was administered during the week of final examinations, several days after regular classes had ended, suggesting these findings withstand even with the rigorous demands on the students at that time.

Several studies have demonstrated the benefits of students using yoga or meditation to manage the stress of academic life, predominantly among medical, psychology, and nursing students. However, none incorporated a dual intervention with pharmacy students. O’Driscoll and colleagues conducted a systematic review on the benefits of mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for undergraduate health and social care college students. Eleven studies met the inclusion criteria demonstrating benefits in student stress, anxiety, and mindfulness. Limitations of these studies included lack of long-term follow-up, potential risk of bias, and failure to cite the qualifications of those delivering the mindfulness intervention.18 Another study demonstrating a reduction in stress and increase in self-compassion was conducted by Erogul and colleagues on 59 first-year medical students in Brooklyn, New York, using an 8-week dual intervention of classroom instruction with a home meditation requirement. A major limitation was poor adherence with the home meditation component, resulting in students spending an average of only 14.6 minutes per meditation session.11 In contrast, our study incorporated the meditative practice within our intervention sessions, ensuring that students spent a higher minimum number of minutes meditating (ie, 30 minutes). Though our study did not require a home meditation component, practice was encouraged. Last, Warnecke and colleagues conducted a multicenter, single-blinded, randomized control trial consisting of sole, home-based guided meditation practice using a 30-minute audio compact disc for final-year medical students in Australia. Students documented adherence to the daily, eight-week intervention in a written diary. Results demonstrated a reduction in the students’ levels of stress and anxiety. Similar to our study, the PSS was used as the outcome measure. A reduction from baseline of -3.4 points was observed as compared to our findings of a -7.9 points reduction, demonstrating that a face-to-face, dual yoga and meditation practice, as opposed to home study, may yield a greater reduction in student stress.17

As compared to previously reported studies in this area, our pilot possessed many strengths, including a high quality, dual yoga and meditation intervention in addition to well-qualified, experienced practitioners leading the sessions. Limitations included a small sample size and short duration of follow up. Our study was also limited by potential self-reported outcomes which may have led to reporting bias by participants. Further study limitations included a lack of randomization and a control group. Future studies may be designed as a two arm evaluation with a control group. Strategies that could be used to ensure students sustain their yoga and meditative practice long term include, but are not limited to, weekly yoga and meditation sessions within the college or university, lectures on yoga and meditation within required courses, involvement in the program by student organizations, and “buy in” and/or participation by faculty members.25 Home-based practices using mindfulness apps may also facilitate long-term inclusion in daily practice and lend a more realistic evaluation of student practice time. Additionally, app use may reduce recall bias. As a result of our research project, the University of Rhode Island College of Pharmacy has implemented a consistent yoga and meditation program for all students and staff and faculty members that includes once weekly drop-in, guided meditation sessions throughout the academic year. Additional meditation sessions are offered during the week of final examinations to provide increased student support. Consistent with the research project, yoga is offered within the college once weekly for the six weeks preceding finals. Pharmacy schools may be limited in offering mindfulness practices because of a lack of trained practitioners and space; however, both may be overcome by including faculty support for training and potentially holding sessions in an offsite location. At a minimum, incorporation of home-based practice should be encouraged and supported for all students.

CONCLUSION

In this study, PharmD and other college students demonstrated a reduction in stress and anxiety levels after completing a six-week yoga and meditation program. These results suggest that adopting a mindfulness practice for as little as once per week for six weeks may reduce stress and anxiety in college students. Future studies that include a larger number of students and long-term follow-up are needed to ensure a sustained beneficial effect. Institutions of higher education, including pharmacy schools, should consider the inclusion of holistic methods, such as yoga and meditation, to support student self-care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We sincerely thank our collaborators, Erica Estus, Katherine Corsi, Annaliese Clancy, Alissa Margraf, Miranda Monk, and Margaret Smith for their assistance with study design, clinical input, and logistic support.

REFERENCES

- 1. “Stress.” Merriam-Webster.com. 2018. https://www.merriam-webster.com. January 30, 2018.

- 2.Garber M. Exercise as a stress coping mechanism in a pharmacy student population. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(3):Article 50. doi: 10.5688/ajpe81350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beall JW, DeHart RM, Riggs RM, Hensley J. Perceived stress, stressors, and coping mechanisms among Doctor of Pharmacy students. Pharmacy. 2015;3(4):344–354. doi: 10.3390/pharmacy3040344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frick LJ, Frick JL, Coffman RE, Dey S. Student stress in a three-year Doctor of Pharmacy program using a mastery learning educational model. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(4):Article 64. doi: 10.5688/ajpe75464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marshall LL, Allison A, Nykamp D, Lanke S. Perceived stress and quality of life among Doctor of Pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(6):Article 137. doi: 10.5688/aj7206137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noor HS, Maisharah SGS, Hafzan MHN. Perceived stress level assessment among final year pharmacy students during pharmacy based clerkship. Int J Pharm Teach Pract. 2010;1(2):20–23. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirsch JD, Do AH, Hollenbach KA, Manoguerra AS, Adler DS. Students’ health-related quality of life across the preclinical pharmacy curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(8):Article 147. doi: 10.5688/aj7308147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maynor LM, Carbonara G. Perceived stress, academic self concept, and coping strategies of pharmacy students. Int J Pharm Educ Pract. 2012;9(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Psychological Association. Stress in America Survey; 2017. Stress in America: coping with change. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarbacker S, Kimple K. The Eight Limbs of Yoga. 1st ed. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erogul M, Singer G, McIntyre T, Stefanov DG. Abridged mindfulness intervention to support wellness in first-year medical students. Teach Learn Med. 2014;26(4):350–356. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2014.945025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ross A, Williams L, Pappas-Sandonas M, Touchton-Leonard K, Fogel D. Incorporating yoga therapy into primary care: The Casey Health Institute. Int J Yoga Therap. 2015;25(1):43–49. doi: 10.17761/1531-2054-25.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nemati A. The effect of pranayama on test anxiety and test performance. Int J Yoga. 2013;6(1):55–60. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.105947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Falsafi N. A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness versus yoga: effects on depression and/or anxiety in college students. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2016;22(6):483–497. doi: 10.1177/1078390316663307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim S. Effects of yogic eye exercises on eye fatigue in undergraduate nursing students. J Phys Ther Sci. 2016;28(6):1813–1815. doi: 10.1589/jpts.28.1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oman D, Shapiro SL, Thoresen CE, Plante TG, Flinders T. Meditation lowers stress and supports forgiveness among college students: a randomized control trial. J Am Coll Health. 2008;56(5):569–578. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.5.569-578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warnecke E, Quinn S, Ogden K, Towle N, Nelson MR. A randomised controlled trial of the effects of mindfulness practice on medical student stress levels. Medical Education. 2011;45:381–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Driscoll M, Byrne S, McGillicuddy A, Lambert S, Sahm LJ. The effects of mindfulness-based interventions for health and social care undergraduate students - a systematic review of the literature. Psychol Health Med. 2017;22(7):851–865. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2017.1280178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Julian LJ. Measures of anxiety. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(0 11) doi: 10.1002/acr.20561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muntingh AD, van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, van Marwijk HW, Spinhoven P, Penninx BW, van Balkom AJ.Is the beck anxiety inventory a good tool to assess the severity of anxiety? A primary care study in the Netherlands study of depression and anxiety (NESDA) BMC Fam Pract 2011 4. Jul1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cohen S, Williamson G. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In S. Spacapam & S. Oskamp (Eds.), The Social Psychology of Health: Claremont Symposium on Applied Social Psychology (pp 31-32). Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1988.

- 23.Lee EH. Review of the psychometric evidence of the perceived stress scale. Asian Nursing Research. 2012;6(4):121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, Krietemeyer J, Toney L. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment. 2006;13(1):27–45. doi: 10.1177/1073191105283504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kinser P, Braun S, Deeb G, Carrico C, Dow A. Awareness is the first step: an interprofessional course on mindfulness & mindful-movement for health care professionals and students. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2016;25:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]