Abstract

Latin America is a conglomerate of adjacent countries that share a Latin extraction and language (Spanish or Portuguese) and exhibit extreme variations in socioeconomic status. End-stage renal disease prevalence and incidence rates have been growing steadily, probably as a result of the increase in life expectancy, aging of the population, a growing epidemic of type 2 diabetes, and a fast epidemiologic transition across the region. Chronic noncommunicable diseases impose an enormous cost, barely supported at present and unlikely afforded by Latin America in the future. National health surveys in Chile, Mexico, and Argentina showed a high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors. A total of 21% of the Chilean population had a creatinine clearance <80 ml/min. Among the surveyed people, 8.6% of Argentines, 14.2% of Chileans, and 9.2% of Mexicans had proteinuria. There are ongoing national chronic kidney disease detection programs in Brazil, Cuba, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela; Argentina, Colombia, Bolivia, Dominican Republic, Guatemala, and Paraguay are still developing them. The prevalence of cardiovascular and renal risk factors is high in Latin America. Data about chronic kidney disease are scarce, but public health awareness is high, evidenced by ongoing or developing chronic kidney disease detection programs. High-risk patients (e.g., those with hypertension or diabetes, elderly) must be studied, using simple determinations such as creatinine and proteinuria. For these programs to succeed, lifestyle changes must be encouraged, and public awareness must be increased through teaching and media-oriented activities.

Latin America (LA) is a conglomerate of neighboring countries that share a common Latin ancestry and the Spanish or Portuguese language. It includes Central and South American countries, the Caribbean Hispanic Islands, and Mexico. The territory has an area of 21,069,501 km2. Brazil, with 8,514,877 km2, is the fifth-largest country in the world.

The estimated population is 561,211 million (half of whom live in Brazil and Mexico) (1). Although largely of white origin, it is an amalgam of ancestries and ethnic groups. The composition varies from country to country. Native Americans comprise 8% of the population but prevail in Bolivia and constitute sizable minorities in Ecuador, Guatemala, and Peru. In Argentina, Uruguay, and Puerto Rico, white people predominate. In the remaining countries there is a high proportion of Mulatto, Native American, mixed-race, and black people, all ethnic groups being highly mixed (2). The annual population growth is 1.3%, and, according to estimates, it will increase to 661,454 million in 2020 (1).

The ESRD prevalence has been growing by 6.8% annually during the past 5 yr. The incidence rate increased from 33.3 patients per million people (pmp) in 1993 to 167.8 pmp in 2005 (3). This increment derives from many concurrent causes:

Life expectancy at birth increased by 5 yr in the past 15 (from 67 to 72 yr in 2004) (4,5), determining a growth in the population older than 65, representing a 6% of LA population in 2005 (1)

A type 2 diabetes epidemic, with a constantly increasing prevalence in most countries of the region

Fast lifestyle changes, associated with the population’s moving from rural areas to big cities, which in time promotes sedentary behavior and overweight (currently 78% of the population is urban [1])

Chronic noncommunicable diseases, including chronic kidney disease (CKD), are the first cause of death in developed countries. They also impose an enormous cost to countries with a small or medium income (6), such as in LA. In many countries in LA, the heavy burden of noncommunicable diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, arterial hypertension, and CKD is not sustainable now and will be unlikely afforded in the future. This reality urges us to develop early detection and prevention programs for cardiovascular and renal risk factors as well as to make the early diagnosis of CKD available, with the aim of putting an end to its progression rate. We first describe ESRD treatment in LA and then summarize the present situation of risk factors and preventive policies in the various countries.

ESRD Treatment: Present Situation in LA

The available information comes from the Latin American Dialysis and Kidney Transplant Registry (LADKTR), a committee of the Latin American Society of Nephrology and Hypertension (SLANH). This registry, in operation since 1991, collects data on ESRD from the 20 SLANH member countries,a currently comprising 97% of the region’s population. The data collection methods have been reported elsewhere (2,3). Although not always universal, the data collected over the years have improved our knowledge on renal replacement therapy (RRT) in LA, promoted the organization of new renal registries in the region, and allowed comparisons with other regions in the world and the analysis of regional trends in ESRD epidemiology and its treatment.

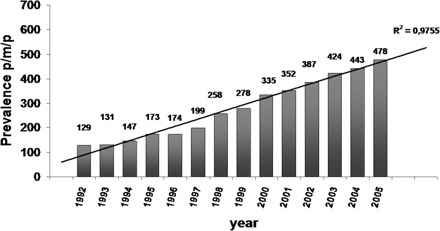

As mentioned, the ESRD therapy prevalence has been steadily increasing on a yearly basis, mounting to 478.2 pmp according to the last LADKTR survey (Figure 1). On December 31, 2005, in the 20 SLANH countries, 147,158 patients were undergoing long-term hemodialysis (44% in Brazil), 50,251 were on chronic peritoneal dialysis (65% in Mexico), and >52,000 were living with a functioning kidney graft (3).

Figure 1.

ESRD prevalence rate progression (all modalities) in Latin America.

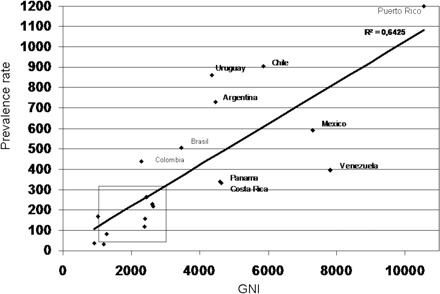

The prevalence rate varies enormously among countries; this is basically associated with the different health coverage and gross national income (GNI). Thus, the prevalence rate is >600 pmp in Puerto Rico, Chile, Uruguay, and Argentina; between 300 and 600 pmp in Colombia, Brazil, Mexico, Panama, and Venezuela; and significantly smaller in the rest of the countries, as low as <50 pmp. Figure 2 shows the relation between the prevalence rate and GNI (3).

Figure 2.

Linear correlation between gross national income (GNI; per capita in US dollars) (7) and prevalence of renal replacement therapy in 2005 (all modalities).

A simultaneous rise in the incidence rate, from 33.3 pmp in 1993 to 167.5 pmp in 2005, has occurred. This growth in prevalence and incidence is present in all countries in LA; the only one tending to an incidence rate stabilization is Puerto Rico (310 pmp in 2005).

Diabetes has remained the leading cause of ESRD (30.3% of incident population). The highest incidence is reported in Puerto Rico (65%), Mexico (51%), Venezuela (42%), and Colombia (35%) (3).

Regarding renal transplantation, active programs are running in the 20 SLANH countries, where 7968 kidney transplants were performed during 2005. The cumulative number is 98,541, since the first one made in Argentina in 1957; Brazil and Mexico performed 63% of them (43,405 and 18,444, respectively) (3). There are also active double-transplantation programs in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Uruguay (3).

The transplantation rate has increased from 3.7 pmp in 1987 to 15 pmp in 2005; the proportion of deceased donors has remained stable, approximately 50%, during the past few years but predominated widely in some countries (≥70% in Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Peru, and Uruguay). In contrast, all renal transplants come from living donors in El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Dominican Republic (3).

ESRD Therapy Coverage in LA

LA is a region of deep inequities. This can be easily esteemed when different socioeconomic indexes are analyzed. For example, LA’s mean GNI is US $4045, but it ranges between $910 in Nicaragua and $10,560 in Puerto Rico; the life expectancy at birth ranges from 64.5 yr in Bolivia to 78.7 yr in Costa Rica (average of 72 yr); the human development index (a composite index that measures a country’s average achievements on the basis of life expectancy, literacy, education, and standard of living) varies from 0.663 in Guatemala to 0.863 in Argentina with an average of 0.797 for LA (5–7). The imbalance is also present in the access to ESRD therapy. Coverage of 100% of patients who receive a diagnosis of ESRD is available in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Uruguay, and Venezuela. In the remaining countries, the coverage percentage varies from 56% in Colombia to only 25% in Peru and Paraguay (3).

Predictably, in the countries with 100% coverage, prevalence rates are higher, with a mean of 553 pmp for dialysis therapy and 18.2 pmp for kidney transplants; however, when the remaining countries are analyzed, prevalence rates in the population with health insurance are as high as or even higher than those observed in nations with full coverage. For instance, in 2000, the ESRD therapy prevalence rate in Mexico was 376 pmp, but among the population covered by the Health Security System in Jalisco State, it was 939 pmp (8). In Peru, the country’s prevalence rate was 196 pmp but increased to 789 pmp in the insured group in 2003 (9). These data confirm that LA’s ESRD prevalence is not lower than that in developed regions worldwide. The lower RRT prevalence probably reflects an underdiagnosis of the disease, even in countries with full ESRD treatment coverage.

Prevalence of CKD Progression Risk Factors in LA

This information regarding prevalence of CKD progression risk factors is scarce, even nonexistent in several countries; in addition, the available studies about prevalence of cardiovascular and renal disease risk factors are insufficient and have not always been performed with the same methods. Moreover, during the past few years, LA has been experiencing a fast epidemiologic transition (characterized by a long-term shift in mortality and disease patterns whereby infection pandemics are replaced by chronic noncommunicable diseases) (10), which nowadays is going through different phases in different countries. All these facts make it difficult to establish the real prevalence of CKD progression risk factors.

To develop public health policies and programs, we need to know the prevalence and distribution of risk factors in the population, as well as the trends that are developing in different groups. Thus, national health surveys are highly desirable; however, most of the countries in LA conduct them only sporadically, mainly focusing on infections and on child and mother mortality. Argentina, Chile, and Mexico recently finished national health surveys, which have revealed a high prevalence of risk factors (Table 1). Some facts are prominent and emphasize the magnitude of the epidemiologic change, such as the tobacco-smoking habit increasing in teenagers; the increment in obesity and central obesity affecting all age groups, including children and teenagers, and prevailing in women; the same incidence of risk factors in rural and urban population; and the increase of metabolic syndrome (reaching 48% among people older than 65 yr in the Chilean survey) (11–13).

Table 1.

Results of national health surveys from Chile, Mexico, and Argentina: Prevalence of cardiovascular and renal risk factorsa

| Parameter | Chileb | Mexico | Argentinac |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2003 | 2006 | 2005 |

| Age | >17 | >19 | >18 |

| Hypertension (%) | 33.70 | 30.80 | 30.90 |

| Hypercholesterolemia (%) | 35.00 | 26.50 | 27.90 |

| Overweight (%) | 38.00 | 39.50 | 34.50 |

| Obese (%) | 22.00 | 31.10 | 14.60 |

| Abdominal obesity (ATP III; %) | 29.50 | 47.80 | NA |

| Diabetes | 4.20 | 7.00 | 8.50 |

| Current smoking (%) | 42.00 | 21.50d | 33.40 |

| Past and current smoking | 57.00 | 34.80d | NA |

| Sedentary lifestyle (%) | 89.40 | NA | 46.20 |

| Metabolic syndrome (%) | 23.00 | NA | NA |

| Ccr <80 ml/min (%) | 20.97 | NA | NA |

| Ccr <30 ml/min (%) | 0.18 | NA | NA |

| Proteinuria (%)e | 14.20 | 9.20d | NA |

| Hematuria (%)e | 36.40 | NA | NA |

ATP III, Adult Treatment Panel III; Ccr, creatinine clearance; NA, not available

The sample had an excess of participants who were older than 65 yr (10.9% in general population versus 25.4% in the surveyed population).

Data were collected only as self-reporting.

Data were taken from the Health National Survey Year 2000 (ENSA 2000). Subjects included in the analysis of proteinuria were between 20 and 69 yr of age (mean 44.6 13.6) (31).

Measured by dipstick, in only one recently voided urine sample. Proteinuria was considered positive at 30 mg.

In Uruguay, the prevalence of hypertension ranges between 33 and 39% (14–17), and the prevalence of diabetes was 8% in a survey of adults for whom a fasting serum glucose was conducted (18). Although there has been an established RRT program for all ESRD-diagnosed patients since 1981, there has been no study on the prevalence of CKD. With the aim of finding out about the prevalence of cardiovascular and renal disease risk factors, a national survey will begin in 2008.

In Brazil, several population-based studies found a high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors (Table 2) (19–26). The prevalence of hypertension was directly correlated to age, overweight/obesity, abdominal obesity, diabetes, alcohol consumption, and relatives with hypertension (20–26).

Table 2.

Population-based studies performed in urban adult populations in Brazil

| Authors | Place | Subjects Surveyed (n) | Hypertension | Overweight + Obese | Current Smoker | Obese | Sedentary | Diabetes | High Cholesterol | Central Obesity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freitas et al. (19) | Catanduva | 688 | 31.5 | 55.5 | NA | 18.6 | 71.4 | 6.7 | NA | NA |

| Gus et al. (20) | Rio Grande do Sul | 1066 | 31.6 | 54.7 | 33.9 | 21.0 | 71.3 | 7.0 | 25.7 | NA |

| Lessa et al. (21) | Salvador | 1439 | 29.9 | 44.8 | 21.7 | 13.6 | 60.2 | 8.3 | 31.3 | 35.5 |

| Veiga Jardim et al. (22) | Goiania | 1739 | 36.4 | 43.6 | 20.1 | 13.6 | 62.3 | NA | NA | 38.5b |

| Pereira et al. (23) | Tubarao | 707 | 40.5 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Araujo de Castro et al. (24) | Formiga | 285 | 32.7 | NA | 22.8 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 31.2 women, 9.2 mena |

| Araujo de Souza et al. (25) | Campo Grande | 892 | 41.4 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Dias Da Costa et al. (26) | Pelotas | 1968 | 37.2a | 53.1 | 30.4 | NA | 80.6 | 5.6 | NA | NA |

| Atlas Corações do Brazil (29) | Whole country | 2500 | 28.5 | 57.9 | 24.2 | 22.5 | 83.5 | 9.0 | 21.6 | 25.7,a 37.1b women 9.6,a 24.5b men |

The Brazilian Society of Cardiology conducted a nationwide survey of cardiovascular risk factors: 2500 people filled out a questionnaire with lifestyle information, and 1500 consented to a physical examination and blood testing. This survey showed also a high prevalence of risk factors (Table 2). Unfortunately, results about increased creatinine have not been published yet, although they will be available in the future, because serum samples were kept for future determinations (29). In Peru, a cross-sectional survey that included 14,256 adults showed a 23.7% prevalence of hypertension, with no difference between people living 3000 m above or below sea level (30). Clearly, there is a high prevalence of cardiovascular and renal risk factors in LA: hypertension, diabetes, and obesity, among others. Their prevention and treatment may strongly contribute to diminish cardiovascular mortality and ESRD progression.

What we do not have are data concerning the prevalence of CKD in LA or about who will progress to ESRD. So far, the Mexican and Chilean health surveys are the only ones providing national data; small studies performed in Brazilian and Argentine cities supply some more partial data. In the 2000 Mexican Health Survey, 9.2% of participants had proteinuria, which was strongly associated with hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and age (31). The Chilean survey found 14.2% prevalence of proteinuria and 21% with a creatinine clearance (Ccr) <80 ml/min (12).

The first LA population-based study to detect the prevalence of elevated serum creatinine was conducted in 1997 in Bambuóı, a small Brazilian town. Only 0.5% of the adults (18 to 59 yr of age) and 5.1% of the senior citizens (>60 yr of age) were found to have high creatinine (>1.3 mg/dl for men and 1.1 mg/dl for women). These figures may be underestimated, however, because they may be the result of a lower survival of patients with renal dysfunction, related to a lack of medical attention, or to a selective migration of those with a more advanced disease to larger cities looking for available, complex medical procedures (32). In Argentina, screening programs in adults from several regions showed an 8.3 to 8.6% prevalence of proteinuria (which exceeded 14% in people older than 60) and 4.1% prevalence of microalbuminuria (33–35).

In Mexico, a population-based cross-sectional survey in the city of Morelia was conducted on a sample of 3961 adults. Extrapolating the results to the whole country, the prevalence of Ccr <60 ml/min was 80,788 pmp and <15 ml/min was 1142 pmp, similar to those found in industrialized countries. Hypertension was present in 25% of the patients with a Ccr <60 ml/min and in 58% of those with a Ccr <15 ml/min. Proteinuria was detectable in 8.7% of those with Ccr <60 ml/min but increased to 12.5% in those with diabetes and hypertension (36).

If we extrapolate the values published in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) (37) for the population of LA in comparable age groups, there may be 47,000,000 patients with CKD in the region (Table 3). These figures might not be valid in LA, but we have shown that renal disease risk factor prevalence is high in countries in LA, and the use of this extrapolation may constitute a powerful tool to increase public health awareness about the burden of renal and cardiovascular disease and to point out the need to obtain data in each country. Meanwhile, the establishment of programs meant to detect early patients who are at risk for developing CKD and prevent its progression is of the utmost importance; however, a detection program cannot be based on screening the whole population. We need simple programs directed to highrisk groups, such as the elderly; those with diabetes, hypertension, and obesity; and relatives of patients with ESRD. These programs may include simple actions, such as BP control, microalbuminuria or proteinuria and creatinine measurements (using simple formulas to calculate GFR), and glycemic control in patients with diabetics and metabolic syndrome. Besides performing an adequate diagnosis and treatment, we must train primary care physicians, and the population must be alerted about their probable belonging to groups at risk for having CKD so that detection can be made earlier to facilitate consultations and follow-up by specialized health teams.

Table 3.

Patients with CKD in LA (extrapolated from NHANES III)a

| Patients with CKD | Population |

|---|---|

| Total | 46,989,171 |

| stage 1 | 19,081,977 |

| stage 2 | 14,588,763 |

| stage 3 | 12,214,676 |

| stage 4/5 | 996,832 |

CKD, chronic kidney disease; LA, Latin America; NHANES III, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

It is also necessary to load the information in a database in a way that will let us identify patients at highest risk for adverse outcomes and with a higher lifetime risk for ESRD, as well as the prevalence of such individuals in target groups. We know that lower income, diabetes, hypertension, hematuria, proteinuria, and an elevated serum creatinine all are independent ESRD risk factors in the general community. Other variables, such as a family history of CKD, may also be useful for risk stratification. The combination of an elevated creatinine and proteinuria may be particularly useful in identifying a group at higher risk for progression. The use of these measurements in target groups sorted by older age, diabetes, and hypertension increases the probability of finding abnormalities through screening and improves the screening effectiveness itself.

Status of Detection Programs in LA

This year, the LADKTR Committee collected data in a simple survey, designed with the intention of finding out both whether the prevalence of risk factors was known in each country and whether national health policies for CKD detection and prevention existed. The survey, answered by 14 countries, showed that there is public health awareness about the burden of CKD, as revealed by the implementation or development of national CKD detection programs in 11 of the 14 surveyed countries. In 11, cardiovascular disease risk factors prevalence is already known, although the data are frequently partial. Smoking is forbidden in public places in most of the countries (Table 4). Moreover, partially supported by the International Society of Nephrology, there are ongoing screening and prevention programs in La Paz (Bolivia) and Isle of Youth (Cuba). Projects in Guadalajara (Mexico), Guayaquil (Ecuador), Tarija/La Paz (Bolivia), and Uruguay are about to start. As a result, a lot of information will be available in the next few years.

Table 4.

Results of LADKTR survey about CKD detection and cardiovascular and renal risk factorsa

| LADKTR Items Survey | Argentina | Bolivia | Brazil | Chile | Cuba | Costa Rica | Colombia | Guatemala | Mexico | Paraguay | Peru | Dominican Republic | Uruguay | Venezuela |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National CKD detection Program | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| stage (project/ongoing) | Project | Project | Ongoing | Ongoing | Project | Project | Project | Ongoing | Project | Ongoing | Ongoing | |||

| includes creatinine measurement | ND | Yes | Yes | – | Yes | – | Yes | No | – | ND | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| proteinuria measurement | ND | Yes | Yes | – | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – | ND | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| arterial tension measurement | ND | Yes | Yes | – | Yes | – | Yes | No | – | ND | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Prevalence of known risk factors arterial hypertension | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yesb | No |

| diabetes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yesb | No |

| smoking | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yesb | No |

| obesity | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yesb | No |

| dyslipidemia | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yesb | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yesb | No |

| low birth weight | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| proteinuria | Yesb | No | No | Yes | Yesb | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| microalbuminuria | Yesb | No | No | No | Yesb | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yesb | No |

| smoking forbidden in public places | Yesb | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No |

LADKTR, Latin American Dialysis and Kidney Transplant Registry; ND, not determined yet.

Only regional.

During the past decade, the SLANH has been developing multiple activities to improve CKD detection and renal health in the region. In 2005, a consensus emerged, establishing that it is time to collect data, to recognize and evaluate risk factors, to implement primary prevention policies, to reduce the shortage of physicians and nurses, to implement educational programs on CKD, to promote public awareness programs on CKD, and to standardize GFR measurements (38).

Conclusions

Although scarce, available data seem to confirm that the prevalence of cardiovascular and renal risk factors is high in LA. Data about CKD prevalence are even more limited, although the prevalence of proteinuria seems to be high (>8% whenever tested). Some national and several small population survey studies have been done or are ongoing in various cities or regions in LA; their results are available or will be in the near future.

There is public health awareness regarding CKD detection, as shown by the implementation or development of national CKD detection programs in 11 countries. These programs must focus their attention on high-risk patients, such as those with hypertension, diabetes, and obesity, and include simple actions, such as BP and glucose control and microalbuminuria or proteinuria and serum creatinine measurements. For them to succeed, we need to reach primary care physicians and the general population through teaching and media-oriented activities to improve awareness at all levels, a task in which nephrologists must be heavily involved. Finally, the patients who receive a diagnosis of CKD and their follow-up must be included in a database, to identify those who are at risk for the worst outcomes.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

F. Inserra (Argentina), S. Maury Fernandez (Bolivia), J. Lugon (Brazil), R. Gomez (Colombia), H. Poblete Badal (Chile), M. Cerdas Calderon (Costa Rica), M. Almaguer (Cuba), J.V. Sanchez Polo (Guatemala), G. Garcia Garcia (Mexico), V. Franco Acosta (Paraguay), A. Saavedra Lopez (Peru), E. Mena (Dominican Republic), N. Mazzuchi (Uruguay), and R. Carlini (Venezuela) answered the LADKTR survey.

Footnotes

Countries grouped in SLANH are Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Ecuador, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Puerto Rico, Uruguay, and Venezuela.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (CEPAL): Statistical Yearbook for Latin America and the Caribbean, 2005. Social Statistics, 2006. [in Spanish]. Available at: http://www.eclac.org/publicaciones/xml/ 0/26530/LCG2311B_1.pdf. Accessed August 4, 2007

- 2.Cusumano A, Di Gioia C, Hermida O, Lavorato C: Latin American Registry of Dialysis and Renal Transplantation: The Latin American Dialysis and Renal Transplantation Report 2002. Kidney Int 68 [Suppl 97]: S1–S7, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cusumano A, Garcia Garcia G, Gonzaólez Bedat MC: Latin American Dialysis and Transplantation Registry, report 2006. Ethn Dis 2008, in press [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.United Nations Development Program: Human Development Report 1990, 1990. Available at: http://hdr.undp.org/en/media/hdr_1990_en.pdf. Accessed August 3, 2007

- 5.United Nations Development Program: Human Development Report 2006, 2006. Available at: http://hdr.undp.org/en/media/hdr06-complete.pdf. Accessed August 3, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization: The World Health Report 2003: Shaping the Future, Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. Available at: http://www.who.int/whr/2003/en/whr03_en.pdf. Accessed August 3, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 7.World development indicators 2005, World Bank database. Available at: http://devdata.worldbank.org/data-query. Accessed July 26, 2007

- 8.Garcia-Garcia G, Monteon-Ramos JF, Garcia-Bejarano H, Gomez-Navarro B, Reyes IH, Lomeli AM, Palomeque M, Cortes-Sanabria L, Breien-Alcaraz H, Ruiz-Morales NM: Renal replacement therapy among disadvantaged populations in Mexico: A report from the Jalisco Dialysis and Transplant Registry (REDTJAL). Kidney Int 68[Suppl 97]: S58–S61, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hurtado A: End stage renal failure and risk factors in Peru. Available at: http://www.minsa.gob.pe/portal/ 03Estrategias–Nacionles/06ESN-Notransmisibles/Archivos/ENDSTAGERENALFAILUREANDRISKFACTORSIN PERU.pdf. Accessed July 31, 2007

- 10.Omran AR: The epidemiologic transition: A theory of the epidemiology of population change. Milbank Mem Fund Q 49: 509–538, 1971 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olaiz-Fernaóndez G, Rivera-Dommarco J, Shamah-Levy T, Rojas R, Villalpando-Hernaóndez S, Hernaóndez-Avila M, Sepuólveda-Amor J: National Health and Nutrition Survey 2006. [in Spanish]. Cuernavaca, Mexico, National Institute of Public Health, 2006. Available at: http://www.insp.mx/ensanut/. Accessed August 2, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 12. National Health Survey 2003 (ENS 2003) [in Spanish]. Available at: http://www.emol.com/noticias/documentos/ informe_salud.pdf. Accessed August 2, 2007.

- 13.First National Risk Factors Survey [in Spanish], 1st Ed., Buenos Aires, National Health Minister, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bianchi MJ, Fernaóndez Cean JM, Carbonell ME, Bermuódez C, Manfredi JA, Folle LE: Arterial Hypertension Epidemiologic Survey in Montevideo: prevalence, risk factors, and follow-up plan [in Spanish]. Rev Med Uruguay 10: 113–120, 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 15.2° Uruguayan Consensus on Arterial Hypertension [in Spanish]. Rev Hipertens Art Montevideo 7: 3–78, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bianchi M, Nieto F, Sandoya E, Senra H: Hypertension prevalence, treatment and degree of control in an adult Uruguayan population [Abstract]. Hypertension 33: 1262, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schettini C, Bianchi M, Nieto F, Sandoya E, Senra H: Ambulatory blood pressure: Normality and comparison with other measurements. Hypertension Working Group. Hypertension 34: 818–825, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferrero R, Garcóıa MV: Diabetes prevalence survey in Uruguay - First Phase: Montevideo, 2004 [in Spanish]. Arch Med Int 27: 7–12, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freitas OC, Carvalho FR, Neves JM, Veludo PK, Parreira RS, Gonçalves RM, Lima SA, Bulgarelli S: Prevalence of hypertension in the urban population of Catanduva, in the State of Sao Paulo, Brasil. Arq Bras Cardiol 77: 16–21, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gus I, Harzheim E, Zaslavsky C, Medina C, Gus M: Prevalence, awareness and control of systemic arterial hypertension in the State of Rio Grande Do Sul. Arq Bras Cardiol 83: 429–433, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lessa I, Magalhaes L, Araóujo M, Almeida Filho N, Aquino E, Moónica M: Arterial hypertension in the adult population of Salvador (BA)-Brazil. Arq Bras Cardiol 87: 683–692, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Veiga Jardim P, Peixoto MR, Monego ET, Humberto Graner Moreira HG, Oliveira PV, Barroso Souza WK, Scala LC: High blood pressure and some risk factors in a Brazilian Capital. Arq Bras Cardiol 88: 398–403, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pereira M, Soares de Azevedo Coutinho M, Freitas P, D’Orsi E, Bernardi A, Hass R: Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in the adult urban population of Tubarao, Santa Catarina, Brazil, 2003 [in Portuguese]. Cad Saude Publica 23: 2363–2374, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arauójo de Castro R, Cajado Monzau J, Marcopito F: Hypertension prevalence in the city of Formiga, MG (Brazil). Arq Bras Cardiol 88: 301–306, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Araóujo de Souza A, Costa A, Nakamura D, Mocheti L, Stevanato Filho P, Ovando L: A study on systemic hypertension in the city of Campo Grande MS, Brazil. Arq Bras Cardiol 88: 388–392, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dias da Costa J, Correa Barcellos F, Sclowitz M, Sclowitz IK, Castanheira M, Olinto MA, Menezes AM, Petrucci D, Macedo S, Costa Fuchs S: Hypertension prevalence and its associated risk factors in adults: A population-based study in Pelotas. Arq Bras Cardiol 88: 54–59, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults: Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA 285: 2486–2497, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.International Diabetes Federation: The IDF consensus worldwide definition of the metabolic syndrome, 2005. Available at: http://www.idf.org/webdata/docs/Metac_ syndrome_def.pdf. Accessed November 9, 2007

- 29.Atlas Hearts of Brazil [in Portuguese], 2005. Available at: http://educacao.cardiol.br/coracoesdobrasil/default.asp. Accessed October 20, 2007

- 30.Regulo Agusti C: Epidemiology of arterial hypertension in Peru [in Spanish]. Acta meód peruana 23: 69–75, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosas M, Attie F, Pastelin G, Lara A, Velazquez O, TapiaConyer R, Martinez-Reding J, Mendez A, Lorenzo-Negrete A, Herrera-Acosta J: Prevalence of proteinuria in Mexico: A conjunctive consolidation approach with other cardiovascular risk factors—The Mexican Health Survey 2000. Kidney Int 68[Suppl 97]: S112–S119, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pasos V, Barreto S, Lima-Costa M, the Bambuí Health and Ageing Study Group: Detection of renal dysfunction based on serum creatinine levels in a Brazilian community. The Bambuóı Health and Ageing Study. Braz J Med Biol Res 36: 393–401, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Sereday MS, Gonzalez C, Giorgini D, De Loredo L, Braguinsky J, Cobeñas C, Libman C, Tesone C: Prevalence of diabetes, obesity, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia in the central area of Argentina. Diabetes Metab 30: 335–339, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inserra F, Cornelio C, Daverio S, Diehl S, Samarelli N, Dóıaz A: Relative frequencies of diabetes, high creatininemia and proteinuria in laboratory determinations in Buenos Aires city. [Abstract; in Spanish]. Nefrologia Argentina 1: 53, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Altobelli V, Elbert A, Pastore R, Gianzanti C, Galli B, Samson R, Cornelio C, Marelli C, Inserra F: Risk factors for chronic kidney and cardiovascular diseases in Salta Province (Argentina) [Abstract; in Spanish]. Nefrologia Argentina 3: 150, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amato D, Alvarez-Aguilar C, Castañeda-Limones R, Rodriguez E, Avila-Diaz M, Arreola F, Gomez A, Ballesteros H, Becerril R, Paniagua R: Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in an urban Mexican population. Kidney Int 68[Suppl 97]: S11–S17, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and associated risk factors—United States, 1999–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 56: 161–165, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dirks JH, Robinson S, Burdmann E, Correa-Rotter R, Mezzano S, Rodriguez-Iturbe B: Prevention strategies for chronic kidney disease in Latin America: A strategy for the next decade—A report on the Villarica Conference. Ren Fail 28: 611–615, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]