Abstract

This study describes trends in the number and percentage of children who entered the US foster care system between 2000 and 2017 because of parental drug use, compared with all other causes.

After more than a decade of declines in the foster care caseload in the United States, cases have risen steadily since 2012.1 Between 2012 and 2017, the number of children living in foster care and entering care increased by 12% and 8%, respectively.1 One proposed explanation for this recent growth is the opioid epidemic, but supporting evidence is scarce.2,3 In this exploratory study, we examine trends in the number of children entering foster care because of parental drug use and describe changes in their characteristics over time.

Methods

We analyzed data from the Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System, a federally mandated data collection system that receives case-level information on all children in foster care in the United States. The database includes information on child demographic characteristics, health status, geographic area, and home removal reason (ie, physical/sexual abuse, neglect, child disability/behavior problems, child alcohol/drug use, parental alcohol/drug use, death, incarceration, inability to cope, abandonment, relinquishment, or inadequate housing). Data were deidentified, and this study did not meet Weill Cornell Medicine institutional review board’s definition of human subjects research.

We identified entries of children in foster care during fiscal years 2000 to 2017 and stratified the sample based on home removals attributable to parental drug use, defined as the principal caretaker’s recurrent and lasting use of drugs. The number of entries is not synonymous with the number of children because children may enter foster care more than once. We calculated national trends of the number and proportion of foster care entries because of parental drug use and reported children characteristics at different time intervals for this population. Characteristics of children entering care for other reasons were reported for comparison. Analyses were conducted using Stata version 15 (StataCorp).

Results

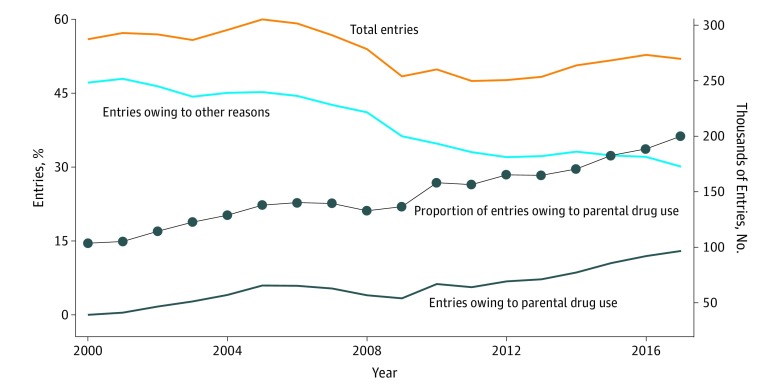

There were 4 972 911 foster care entries between fiscal years 2000 and 2017 (October 1, 1999, to September 30, 2017), 1 162 668 (23.38%) of which were home removals attributable to parental drug use. The number and proportion of entries attributable to parental drug use rose dramatically and steadily during this period, from 39 130 of 269 382 removals (14.53%) in 2000 to 96 672 of 266 583 removals (36.26%) in 2017 (Figure).

Figure. National Trends in Foster Care Entries Attributable to Parental Drug Use, 2000 to 2017.

Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System data for fiscal years 2000 to 2017. Fiscal years are from October 1 to September 30. Parental drug use was missing for 3.5% of the sample. Total foster care entries were stratified into removals for parental drug use (n = 1 162 668) and other reasons (n = 3 636 177). Logistic regression was performed to estimate a linear trend in the proportion of entries for parental drug use during the study period (coefficient, 1.07; P < .001).

Compared with children entering care for other reasons, children entering because of parental drug use were more likely to be 5 years or younger (1 441 741 of 3 635 362 removals [39.65%] vs 699 340 of 1 162 448 removals [60.16%]), white (1 597 066 of 3 524 011 removals [45.32%] vs 616 153 of 1 131 294 removals [54.46%]), and from the southern region of the United States (1 119 679 of 3 636 177 removals [30.79%] vs 519 988 of 1 162 668 removals [44.72%]) (Table). The characteristics of children entering care because of parental drug use changed over time. Notably, between fiscal years 2000 to 2005 and 2012 to 2017, the proportion of children who were white (2000-2005, 148 780 of 291 017 removals [51.12%] vs 2012-2017, 276 296 of 480 012 removals [57.56%]), from the Midwest (2000-2005, 56 734 of 300 633 removals [18.87%] vs 2012-2017, 124 535 of 492 209 removals [25.30%]), and in nonmetropolitan areas (2000-2005, 30 971 of 169 132 removals [18.31%] vs 2012-2017, 120 984 of 492 195 removals [24.58%]) increased. These patterns were not observed among children entering care for other reasons.

Table. Characteristics of Children Entering Foster Care Because of Parental Drug Use Removal vs Other Reasons, 2000 to 2017a.

| Characteristic of Removed Children | Removals, No. (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attributable to Parental Drug Usea | Attributable to Other Reasonsb | |||||||

| 2000-2005 | 2006-2011 | 2012-2017 | Total | 2000-2005 | 2006-2011 | 2012-2017 | Total | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 150 488 (50.08) | 187 050 (50.59) | 250 908 (50.99) | 588 446 (50.63) | 702 088 (51.38) | 621 955 (51.80) | 553 571 (51.85) | 1 877 614 (51.66) |

| Female | 149 991 (49.92) | 182 695 (49.41) | 241 192 (49.01) | 573 878 (49.37) | 664 494 (48.62) | 578 635 (48.20) | 514 111 (48.15) | 1 757 240 (48.34) |

| Age at entry | ||||||||

| Neonatal (≤1 mo) | 38 836 (12.92) | 47 388 (12.82) | 59 686 (12.13) | 145 910 (12.55) | 63 001 (4.61) | 60 395 (5.03) | 57 760 (5.41) | 181 156 (4.98) |

| Postneonatal (>1 mo-<1 y) | 31 721 (10.56) | 45 010 (12.17) | 60 980 (12.39) | 137 711 (11.85) | 104 330 (7.63) | 105 337 (8.77) | 94 753 (8.87) | 304 420 (8.37) |

| 1-5 y | 100 054 (33.29) | 134 750 (36.44) | 180 915 (36.76) | 415 719 (35.76) | 336 296 (24.60) | 321 605 (26.78) | 298 264 (27.93) | 956 165 (26.3) |

| 6-10 y | 66 642 (22.18) | 74 429 (20.13) | 110 560 (22.46) | 251 631 (21.65) | 268 703 (19.66) | 218 918 (18.23) | 216 436 (20.27) | 704 057 (19.37) |

| ≥11 y | 63 267 (21.05) | 68 195 (18.44) | 80 015 (16.26) | 211 477 (18.19) | 594 535 (43.5) | 494 458 (41.18) | 400 571 (37.51) | 1 489 564 (40.97) |

| Race/ethnicityc | ||||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 148 780 (51.12) | 191 077 (53.04) | 276 296 (57.56) | 616 153 (54.46) | 638 264 (48.63) | 520 361 (44.34) | 438 441 (42.24) | 1 597 066 (45.32) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 79 886 (27.45) | 73 711 (20.46) | 68 687 (14.31) | 222 284 (19.65) | 363 585 (27.7) | 316 655 (26.98) | 268 741 (25.89) | 948 981 (26.93) |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 21 908 (7.53) | 30 110 (8.36) | 49 028 (10.21) | 101 046 (8.93) | 87 823 (6.69) | 95 069 (8.10) | 97 929 (9.43) | 280 821 (7.97) |

| Hispanic | 40 443 (13.90) | 65 367 (18.14) | 86 001 (17.92) | 191 811 (16.96) | 222 732 (16.97) | 241 451 (20.57) | 232 960 (22.44) | 697 143 (19.78) |

| Geographic region | ||||||||

| Northeast | 42 004 (13.97) | 49 981 (13.51) | 60 402 (12.27) | 152 387 (13.11) | 156 069 (11.41) | 156 321 (13.02) | 140 964 (13.20) | 453 354 (12.47) |

| Midwest | 56 734 (18.87) | 70 260 (19.00) | 124 535 (25.30) | 251 529 (21.63) | 381 035 (27.86) | 308 709 (25.71) | 253 988 (23.78) | 943 732 (25.95) |

| South | 136 419 (45.38) | 169 510 (45.84) | 214 059 (43.49) | 519 988 (44.72) | 415 147 (30.36) | 367 197 (30.58) | 337 335 (31.59) | 1 119 679 (30.79) |

| West | 65 476 (21.78) | 80 075 (21.65) | 93 213 (18.94) | 238 764 (20.54) | 415 187 (30.36) | 368 629 (30.70) | 335 596 (31.43) | 1 119 412 (30.79) |

| Geographic area | ||||||||

| Metropolitan | 138 161 (81.69) | 296 535 (80.18) | 371 211 (75.42) | 80 5907 (78.16) | 554 814 (81.47) | 980 463 (81.65) | 874 690 (81.91) | 2 409 967 (81.7) |

| Nonmetropolitan, urban | 27 864 (16.47) | 66 175 (17.89) | 108 557 (22.06) | 202 596 (19.65) | 112 479 (16.52) | 196 781 (16.39) | 173 337 (16.23) | 482 597 (16.36) |

| Nonmetropolitan, rural | 3107 (1.84) | 7115 (1.92) | 12 427 (2.52) | 22 649 (2.20) | 13 739 (2.02) | 23 526 (1.96) | 19 777 (1.85) | 57 042 (1.93) |

| Diagnosed physical/mental health condition | 42 584 (14.16) | 49 276 (13.32) | 56 928 (11.57) | 148 788 (12.80) | 232 460 (17.00) | 230 909 (19.23) | 207 456 (19.43) | 670 825 (18.45) |

Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System data for fiscal years 2000 to 2017. Fiscal years are from October 1 to September 30. Parental drug use was missing for 3.5% of the sample. Total foster care entries were stratified into removals for parental drug use (n = 1 162 668) and other reasons (n = 3 636 177).

Pearson χ2 tests were used to compare the characteristics of children who experienced parental drug use removals and those of children who experienced removal for other reasons during the study period and compare the characteristics of children across time intervals separately among those who experienced parental drug use and other removal reasons. Given the large sample, P values were all <.001.

Race/ethnicity was self-identified. In the case of young children, parents identified the race/ethnicity of the child.

Discussion

The number of foster care entries attributable to parental drug use increased substantially from 2000 to 2017 (from 39 130 to 96 672 removals, an increase of 57 542 removals [147.05%]), even when entries for other removal reasons mostly declined. These findings suggest that greater parental drug use has contributed to increases in foster care caseloads and coincide with increasing trends in opioid use and overdose deaths nationwide during this period.

Foster care placement generally implies that a child has faced abuse or neglect. Adverse childhood experiences, such as abuse, neglect, or having a parent who uses drugs, increase the risk of chronic health conditions and other poor outcomes across the lifespan.4 Additionally, when children enter foster care because of parental drug use, episode duration is longer and less likely to result in reunification with the parent.5 This is of special concern because of the large proportion of children experiencing entry before age 5 years, a critical period for forming stable attachments.

Limitations of this study include potential reporting inconsistencies in parental drug use. Moreover, it is possible that factors other than drug use influenced entries for parental drug use.

Policy makers must ensure that the needs of this new wave of children entering foster care because of parental drug use are being met though high-quality foster care interventions. These have been shown to mitigate some of the adverse effects of early childhood deprivation and disruptions in attachment.6

References

- 1.Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau Trends in foster care and adoption: FY 2008. –FY 2017. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/trends_fostercare_adoption_08thru17.pdf. Accessed January 29, 2019.

- 2.Ghertner R, Waters A, Radel L, Crouse G. The role of substance use in child welfare caseloads. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2018;90:83-93. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.05.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quast T. State-level variation in the relationship between child removals and opioid prescriptions. Child Abuse Negl. 2018;86:306-313. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245-258. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lloyd MH, Akin BA, Brook J. Parental drug use and permanency for young children in foster care: a competing risks analysis of reunification, guardianship, and adoption. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2017;77(C):177-187. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.04.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Humphreys KL, Nelson CA, Fox NA, Zeanah CH. Signs of reactive attachment disorder and disinhibited social engagement disorder at age 12 years: effects of institutional care history and high-quality foster care. Dev Psychopathol. 2017;29(2):675-684. doi: 10.1017/S0954579417000256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]