Abstract

Menopausal symptoms and quality of life (QOL) of pre- and postmenopausal women in Sri Lanka have not been studied adequately. This study aimed to evaluate the prevalence and severity of menopausal symptoms and the QOL of pre- and postmenopausal women in Galle District, Sri Lanka. A cross-sectional study was conducted with a randomly selected sample of premenopausal (n=184) and postmenopausal (n=166) community-dwelling healthy women aged 30-60 years. The mean (SD) ages of pre- and postmenopausal women, respectively, were 46.1(3.7) and 55.8(3.8) years. Menopausal symptoms were evaluated using the menopause rating scale under three subscales: psychological symptoms, somatovegetative symptoms, and urogenital symptoms. The QOL was evaluated using the short form 36 survey under eight domains. Further, sociodemographic status, gynaecologic factors, physical activity pattern (walking, moderate, and vigorous), body mass index, and waist to hip ratio were also evaluated. The prevalence and severity of all the menopausal symptoms were higher among postmenopausal women. In premenopausal women, the most frequently reported menopausal symptoms were mental exhaustion (49.5%), joint and muscular discomforts (48.5%), and irritability (41.3%). Physical and mental exhaustion (53%), irritability (48.2%), depressive mood (43.4%), and hot flushes (42.2%) were the most frequently reported menopausal symptoms in postmenopausal women. The QOL was significantly impaired among postmenopausal women [mean (SD); 57.47(18.83)] compared to premenopausal women [mean (SD); 66.82(17.93)] (p<0.001). Psychological symptoms score and somatovegetative symptoms score were associated with the QOL of premenopausal women (adjusted R2; 0.35). Somatovegetative symptoms score, psychological symptoms score, moderate and vigorous physical activity scores, and monthly income were associated with the QOL in postmenopausal women (adjusted R2; 0.38). The current study showed that the prevalence and severity of menopausal symptoms and impaired QOL were significantly higher among postmenopausal women, compared to premenopausal women. Menopausal symptoms mostly contributed to the poorer QOL in both pre- and postmenopausal women.

1. Introduction

Menopause is a natural process that every woman experiences due to the age-related gradual decline of primordial ovarian follicles. It is the permanent cessation of menstruation and is defined as 12-month amenorrhea after the final menstruation [1] with no other attributable cause. Menopause and associated biological changes have a negative impact on the general health and quality of life (QOL) as well as the wellbeing of middle-aged women [2–4].

Menopausal symptoms and their severity vary from person to person due to the effects of confounding factors [5] such as lifestyle, social status, body composition, and psychological status [6]. Menopausal symptoms, especially the vasomotor and sexual symptoms, are associated with impaired QOL in women [2, 7]. QOL is “an individual's perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns” [8]. It is an imperative outcome measure of overall health. Therefore, understanding the impact of menopause on the QOL in middle-aged women is critically important in the contemporary health care system [9].

The life expectancy of women is increasing worldwide due to the scientific and technological advances. The average age of a Sri Lankan woman attaining menopause is between 49 and 51 years [2, 10]. Considering the female life expectancy of 78 years, a woman has to spend approximately three decades of her life in the postmenopausal period. Therefore, overall health and wellbeing of middle-aged women have become a major global public health concern. However, there is a paucity of studies [2, 10] related to the menopausal symptoms and the QOL in pre- and postmenopausal women in Sri Lanka. Therefore, this study was designed to evaluate the prevalence and severity of menopausal symptoms, the QOL, and the factors that determine the QOL in a group of pre- and postmenopausal women selected from Galle District, Sri Lanka.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Subjects, and Setting

This descriptive cross-sectional study included 184 premenopausal and 166 postmenopausal community-dwelling healthy women aged 30-60 years, selected from the Bope-Poddala Medical Officer of Health (MOH) area, Galle District in Southern Province of Sri Lanka. The study was conducted from June 2015 to January 2017 as a part of a study project titled “Effects of menopause on bodily structure, functions and physical health” carried out at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Ruhuna, Sri Lanka. The sample size for the main study was calculated based on the BMI (means and SD) between pre- and postmenopausal women in a previous Chinese study [11], using the formula N = (Zα/2+Zβ)2∗ (σ12 + σ22)/ (μ1 – μ2)2, where Zα/2= 95% confidence interval = 1.96, Zβ= 80% power = 0.84, σ1, σ2 = standard deviations, μ1 – μ2 = effects size/ difference between two means. Minimum recommended number of premenopausal and postmenopausal women in each category was 155.

The cluster sampling method was used to achieve the required study sample from 5 out of 18 public health midwives' (PHM) areas that are under the administration of Bope-Poddala MOH office. Cluster sizes for pre- and postmenopausal women were considered based on the total number of pre- and postmenopausal women resident in the specific areas. Support of the Public Health Midwife (primary health care provider) and the Grama Niladari (primary administrative officer) of the specific areas were obtained to select the sample.

Women who were pregnant or lactating or suffering from noncommunicable diseases (NCD), acute or chronic surgical conditions, and polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) were excluded. Women who could not understand the questionnaire, refused to participate in the study, and were illiterate as well as women on hormone replacement therapy (HRT) or hormonal contraceptives were excluded from the study. Menopausal status was considered on the self-stated menstrual history based on the classification of Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW) [12]. Women with the cessation of menstruation within the previous 12 months after last menstruation were considered as postmenopausal women.

2.2. Data Collection

A background questionnaire that was self-developed and pretested was used to evaluate the sociodemographic, gynaecologic, and obstetric characteristics. The presence and severity of menopausal symptoms were evaluated using the Menopause Rating Scale (MRS) [13, 14], a culturally adopted version used in a previous Sri Lankan study [2]. It includes eleven symptoms under three subscales of symptoms, namely, psychological symptoms (disturbances of women's psychological status such as depressive mood, irritability, anxiety, and physical and mental exhaustion), somatovegetative symptoms (disturbances of women's physical and functional status such as hot flushes/sweating, heart discomfort, sleep problems, and joint and muscular discomforts), and urogenital symptoms (disturbances of women's urinary and sexual status such as sexual problems, bladder problems, and dryness of vagina). These were evaluated in a five-point severity scale by way of none, mild, moderate, severe, and very severe. Overall MRS score was generated by summing up the scores given for eleven symptoms. The subscales' scores were also generated by summing up the relevant scores for each symptom that were given in five-point Likert scale as none = 0, mild = 1, moderate = 2, severe = 3, and very severe = 4 [15].

The QOL was evaluated using the Short Form (SF) 36 survey [16], a validated tool for Sri Lankan context [17]. It includes eight domains of QOL, namely, physical functioning (limitations of day to day activities in a typical day), role performance due to physical health (problems associated with work or other regular daily activities as a result of physical health), role performance due to emotional problems (problems associated with work or other regular daily activities as a result of any emotional problems such as feeling depressed or anxious), social functioning (extent of physical health or emotional problems that interfered with normal social activities with family, friends, neighbours, or groups), emotional wellbeing (feelings and reactions), comfort/perception of pain (extent of bodily pain felt and its interference on physical and psychological status), vitality/perception of energy or fatigue (extent of interference with routine physical and emotional problems), and general health (feelings regarding the general health). Further, the physical and psychological dimension scores are formulated by summing up the respective domain scores [16]. In this questionnaire, each domain was given a score ranging from 0 to 100 using the original coding algorithm [16]. The higher scores indicate the higher level of QOL in each domain and overall QOL.

The physical activity level was estimated with the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ), short version which was forward-backward translated into the Sinhala language and pretested. Participants were asked to report the time they were involved in walking, moderate intensity activity, and vigorous intensity activity during the last week prior to the interview. The physical activity data were converted to minutes per week and expressed as a metabolic equivalent (MET-min/week) according to the IPAQ guidelines for data processing [18].

MRS and SF 36 survey questionnaires were self-administered and background questionnaire and IPAQ were interviewer-administered in nature. Women who were unable to provide accurate answers on their own, especially those who had poor understanding and visual impairments, were supported by the principal investigator without suggesting what to include or directing them to come up with answers. Each questionnaire was rechecked by the principal investigator for any missing data in order to ensure its completeness before they left.

Body weight was measured while fasting, with empty bladder, to the nearest 0.1 kg with women dressed in light cloths while height was determined without shoes to the nearest 0.1 cm using a stadiometer with a beam balance (NAGATA, Tainan, Taiwan). Circumferences (cm) of waist (WC) and hip (HC) were measured with a plastic nonstretchable tape. All anthropometry indices were obtained adhering to standard protocols [19] by the principal investigator to ensure the consistency of each measurement. Circumferences were read three times with 1 mm measurement consistency among each measurement and an average of three measurements was obtained. Body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) and waist to hip ratio (WHR) were calculated.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

Continuous variables were presented as mean (SD) and categorical variables were presented as frequencies (%). Chi square test of independence was performed to analyze the association of menopausal status with prevalence and severity of menopausal symptoms. Presence or absence of menopausal symptoms was separately calculated and the women who presented with menopausal symptoms were further categorized into two severity groups as mild to moderate and severe to very severe. Menopausal symptoms scores and the QOL scores were calculated and independent sample t-test was applied to detect the differences between pre- and postmenopausal women.

Independent sample t-test and one way ANOVA with Tukey's test were used to determine the associations between the QOL and categorical (sociodemographic and gynecologic or obstetric) variables. Pearson (r) or Spearman (rho) or point biserial correlation coefficient verified the associations or correlations between the overall QOL score and evaluated variables in both pre- and postmenopausal women. The variables which showed significant correlations with the QOL were further analyzed by multiple regression analysis to ensure the factors affecting the QOL. Hierarchical multiple regression was performed again while controlling the effect of confounders for the QOL: age in both groups and age at menopause and time since menopause in postmenopausal women.

SPSS 20.0 version was used in the data analyses process and P value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

2.4. Ethical Clearance

The Ethics Review Committee, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ruhuna, Sri Lanka, granted the ethical clearance for this study (reference number: 24.09.2014:3.2). Each participant signed the written informed consent before answering the questionnaire.

3. Results

3.1. Basic Characteristics of Pre- and Postmenopausal Women

The mean (SD) ages of pre- and postmenopausal women were 46.1(3.7) and 55.8(3.8) years, respectively (p<0.001). The majority of women were Sinhalese, married, and living with their families in both pre- and postmenopausal groups (Table 1). The mean (SD) ages of menopause and time since menopause of postmenopausal women were 48.3(3.9) and 7.4(5.0) years, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups except the height (postmenopausal women were shorter than premenopausal women) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of pre and postmenopausal women (n=350).

| Characteristics | Sub category | Premenopausal women (n=184) Mean (SD) or Frequency (%) |

Postmenopausal women (n=166) Mean (SD) or Frequency (%) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||

|

| ||||

| Age (years) | 46.1(3.74) | 55.8(3.80) | <0.001∗ | |

|

| ||||

| Ethnicity | Sinhala | 171 (92.9) | 160(96.4) | 0.11 |

| Non Sinhala | 13 (7.1) | 6(3.6) | ||

|

| ||||

| Employment status | Employed | 58(31.5) | 49(29.3) | 0.38 |

| Non employed | 126(68.5) | 118(70.7) | ||

|

| ||||

| Civil status | Married | 169(91.8) | 125(74.9) | <0.001 |

| Single or widowed or divorced | 15(8.2) | 42(25.1) | ||

|

| ||||

| Living companion | With husband and children | 134(72.8) | 103(61.6) | 0.003 |

| With Husband or Children | 16(8.6) | 35(21.0) | ||

| Alone or Others | 34(18.5) | 29(17.4) | ||

|

| ||||

| Education status | Primary education | 37(20.1) | 46(27.6) | 0.12 |

| Secondary education | 68(37.0) | 64(38.3) | ||

| Upper secondary education, degree or diploma | 79(42.9) | 57(34.1) | ||

|

| ||||

| Monthly income | Below 20000 LKR | 92(50.0) | 125(74.8) | <0.001 |

| Above 20000 LKR | 92(50.0) | 42(25.2) | ||

|

| ||||

| Gynecologic factors | ||||

|

| ||||

| Age at menopause (years) | - | 48.3(3.98) | - | |

|

| ||||

| Time since menopause (years) | - | 7.4(5.04) | - | |

|

| ||||

| Parity | Nulliparous | 12(6.5) | 23(13.9) | 0.02 |

| 1-3 children | 152(82.6) | 97(58.4) | ||

| 4-7 children | 20(10.9) | 46(27.7) | ||

|

| ||||

| Modes of deliveries | None | 12(6.5) | 23(13.9) | 0.006 |

| NVD | 109(59.2) | 110(66.3) | ||

| LSCS | 40(21.7) | 23(13.9) | ||

| NVD and LSCS | 23(12.5) | 10(6.0) | ||

|

| ||||

| Other evaluated variables | ||||

|

| ||||

| Weight (kg) | 58.0(9.8) | 57.0(11.9) | 0.44∗ | |

|

| ||||

| Height (m) | 1.5(0.1) | 1.49(0.1) | <0.001∗ | |

|

| ||||

| WC (cm) | 82.5(9.8) | 83.3(12.3) | 0.50∗ | |

|

| ||||

| HC (cm) | 97.0(8.5) | 98.7(10.1) | 0.09∗ | |

|

| ||||

| WHR | 0.84(0.1) | 0.84(0.1) | 0.47∗ | |

|

| ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.98(4.02) | 25.98(4.56) | 0.37∗ | |

|

| ||||

| Walking score (MET/min/week) | 829.21(186.74) | 580.28(156.89) | 0.01∗ | |

|

| ||||

| Moderate physical activities score (MET/min/week) | 4868.04(574.20) | 4770.12(857.01) | 0.20∗ | |

|

| ||||

| Vigorous physical activities score (MET/min/week) | 1785.21(1784.93) | 2297.59(1917.41) | 0.01∗ | |

|

| ||||

| Total physical activity score (MET/min/week) | 7482.51(2400.03) | 7648.03(2534.65) | 0.53∗ | |

SD=standard deviation, NVD=normal vaginal deliveries, LSCS=lower segment caesarian section, BMI=body mass index, WC=waist circumference, HC=hip circumference, WHR=waist to hip ratio

150 LKR = 1 USD (LKR=Sri Lankan rupees)

Primary education= grade 1-10, secondary education=GCE ordinary level

Differences between two groups were compared with independent sample t test∗ and chi square test.

3.2. Prevalence and Severity of Menopausal Symptoms in Pre- and Postmenopausal Women

The prevalence of at least one menopausal symptom among pre- and postmenopausal women was 90.8% (167) and 96.4% (160), respectively (p<0.001). Prevalence and severity of symptoms were higher among postmenopausal women (Table 2). The frequently reported menopausal symptoms among premenopausal women were physical and mental exhaustion (49.5%), joint and muscular discomforts (48.5%), and irritability (41.3%) of mild to moderate severity. In postmenopausal women, physical and mental exhaustion (53%), irritability (48.2%), depressive mood (43.4%), and hot flushes (42.2%) of mild to moderate severity were observed. Severe symptoms were more prevalent among postmenopausal women compared to premenopausal women. Further, 47.6% of postmenopausal women reported joints and muscular discomforts of severe to very severe intensity. Presence of hot flushes (p<0.001), sleep disturbances (p<0.001), anxiety (p=0.03), physical and mental exhaustion (p<0.001), sexual problems (p=0.03), bladder problems (p<0.001), dryness of vagina (p<0.001), and joint and muscular discomforts (p<0.001) were more frequent among postmenopausal women compared to premenopausal women (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence and severity of menopausal symptoms in pre and postmenopausal women (n=350).

| Menopausal symptom | Premenopausal women (n=184) | Postmenopausal women (n=166) |

P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None n(%) | M-M n(%) |

S-VS n(%) | None n(%) | M-M n(%) |

S-VS n(%) |

||

| Hot flushes, sweating | 113 (61.4) | 65 (35.3) | 6 (3.3) |

75 (45.2) |

70 (42.2) |

21 (12.7) |

<0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| Heart discomfort | 132 (71.7) | 47 (25.5) |

5 (2.7) |

104 (62.1) |

53 (15.9) |

9 (5.4) |

0.14 |

|

| |||||||

| Sleep problems | 129 (70.1) | 46 (25) |

9 (4.9) |

69 (41.6) |

65 (39.2) |

32 (19.3) |

<0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| Depressive mood | 104 (56.5) | 69 (37.5) |

11 (6.0) |

80 (48.2) |

72 (43.4) |

14 (8.4) |

0.26 |

|

| |||||||

| Irritability | 101 (54.9) |

76 (41.3) |

7 (3.8) |

77 (46.4) |

80 (48.2) |

9 (5.4) |

0.26 |

|

| |||||||

| Anxiety | 114 (62) |

61 (33.2) |

9 (4.9) |

80 (48.2) |

74 (44.6) |

12 (7.2) |

0.03 |

|

| |||||||

| Physical and mental exhaustion | 82 (44.6) |

91 (49.5) |

11 (6.0) |

45 (27.1) |

88 (53.0) |

33 (19.9) |

<0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| Sexual problems | 149 (81.0) |

31 (16.8) |

4 (2.2) |

115 (32.9) |

43 (25.9) |

8 (4.8) |

0.03 |

|

| |||||||

| Bladder problems | 151 (82.1) |

27 (14.7) |

6 (3.3) |

97 (58.4) |

56 (33.7) |

13 (7.8) |

<0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| Dryness of vagina | 144 (78.3) |

36 (19.6) |

4 (2.2) |

111 (66.9) |

45 (27.1) |

10 (6.0) |

<0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| Joint and muscular discomfort | 40 (21.7) |

89 (48.4) |

55 (29.9) |

20 (12.0) |

67 (40.4) |

79 (47.6) |

<0.001 |

M-M = mild to moderate, S-VS = severe to very severe

Associations were compared with chi square test of independence.

The mean (SD) overall and subscales of symptoms scores were higher among postmenopausal women compared to premenopausal women (p<0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Menopausal symptoms scores and QOL scores of pre and postmenopausal women (n=350).

| Characteristics |

Premenopausal women (n=184) Mean (SD) |

Postmenopausal women (n=166) Mean (SD) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Menopausal symptoms scores | |||

|

| |||

| Psychological symptoms score | 2.78(3.10) | 4.03(3.22) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Somato-vegetative symptoms | 3.14(2.68) | 5.16(3.01 | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Uro-genital symptoms | 0.96(1.72) | 1.77(2.21) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Overall MRS score | 6.90(6.20) | 10.98(6.90) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Quality of life scores | |||

|

| |||

| Physical functioning | 81.68(20.49) | 65.35(24.46) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Role performance due to physical health | 62.09(42.14) | 36.60(42.96) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Role performance due to emotional problems | 61.24(43.59) | 47.61(45.86) | 0.005 |

|

| |||

| Vitality (perception of energy/fatigue) | 62.23(18.44) | 58.43(20.41) | 0.06 |

|

| |||

| Emotional wellbeing | 71.57(17.71) | 70.99(18.53) | 0.76 |

|

| |||

| Social function | 73.17(23.68) | 68.37(24.17) | 0.06 |

|

| |||

| Comfort (perception of pain) | 66.68(23.11) | 58.50(23.62) | 0.001 |

|

| |||

| General health | 55.95(17.18) | 53.92(17.43) | 0.27 |

|

| |||

| Physical health dimension | 65.48(18.31) | 53.57(19.45) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Psychological health dimension | 68.16(19.78) | 61.36(21.16) | 0.002 |

|

| |||

| Overall QOL | 66.82(17.93) | 57.47(18.83) | <0.001 |

MRS=menopause rating scale, QOL=quality of life

Differences between two groups were compared with independent sample t test.

Higher scores indicate higher level of QOL in each domain and overall QOL.

3.3. Quality of Life and Associated Factors of Pre- and Postmenopausal Women

The mean (SD) overall QOL and domains of QOL scores were lower among postmenopausal women (p<0.001). Significantly lower QOL was observed in few domains, namely, physical functioning (p<0.001), role performance due to physical health (p<0.001), role performance due to emotional problems (p=0.005), and comfort (perception of pain) (p=0.001) domains in postmenopausal women (Table 3).

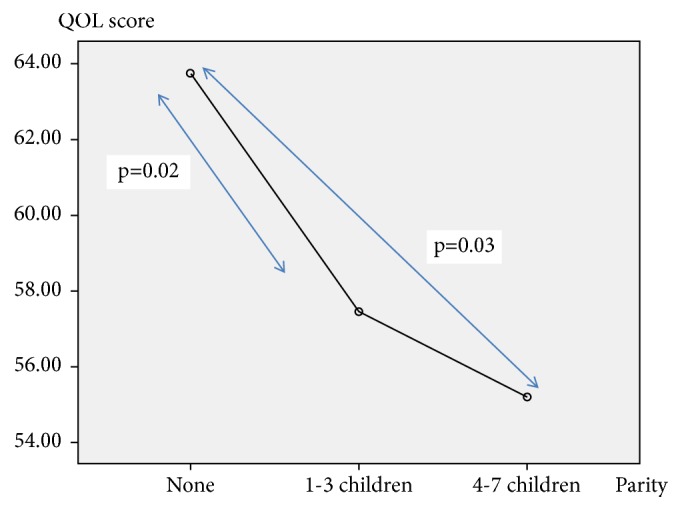

When the associations between QOL and sociodemographic and gynecologic variables were evaluated, there were no significant associations found in premenopausal women. Only monthly income and parity showed significant associations with the QOL in postmenopausal women (Table 4). High monthly income associated with higher QOL while high parity (>4 children) (Figure 1) associated with lower QOL in postmenopausal women (monthly income: rho; 0.24, p=0.006 and parity: rho; -0.21, p=0.03) (Table 5).

Table 4.

Association between QOL and evaluated categorical (sociodemographic and gynecologic) variables of pre- and postmenopausal women (n=350).

| Variable | Premenopausal women (n=184) | Postmenopausal women (n=166) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subcategory | QOL Mean (SD) |

P value |

QOL Mean (SD) |

P value |

|

| Sociodemographic status | |||||

|

| |||||

| Ethnicity | Sinhala | 66.81(17.80) | 0.98∗ | 57.41(18.37) | 0.91∗ |

| Non-Sinhala | 66.95(20.37) | 58.90(31.08) | |||

|

| |||||

| Educational status | Primary education | 64.32(19.69) | 0.20∗∗ | 53.79(20.84) | 0.21∗∗ |

| Secondary education | 65.06(19.53) | 57.60(17.83) | |||

| Upper secondary education, degree, or diploma | 69.51(15.34) | 60.33(18.02) | |||

|

| |||||

| Employment status | Nonemployed | 67.07(18.29) | 0.78∗ | 57.40(18.54) | 0.94∗ |

| Employed | 66.28(17.27) | 57.63(19.70) | |||

|

| |||||

| Civil status | Married | 67.34(17.90) | 0.18∗ | 58.59(18.50) | 0.18∗ |

| Others | 60.96(17.82) | 54.13(19.64) | |||

|

| |||||

| Monthly income | < 20000.00LKR | 64.76(19.15) | 0.12∗ | 55.17(18.64) | 0.007∗ |

| > 20000.00LKR | 68.88(16.48) | 64.23(17.95) | |||

|

| |||||

| Living companion | Husband and Children | 66.13(17.35) | 0.16∗∗ | 58.13(18.19) | 0.81∗∗ |

| Husband or Children | 62.32(23.25) | 55.81(18.04) | |||

| Alone or Others | 71.65(16.99) | 57.22(22.28) | |||

|

| |||||

| Gynecological and reproductive factors | |||||

|

| |||||

| Parity | None | 76.71(15.68) | 0.05∗∗ | 60.83(19.88) | 0.04∗∗# |

| 1-3 children | 66.84(17.60) | 59.43(17.75) | |||

| 4-7 children | 60.78(19.81) | 51.65(19.66) | |||

|

| |||||

| Mode of delivery | None | 76.71(15.68) | 0.23∗∗ | 60.83(19.88) | 0.39∗∗ |

| NVD | 66.56(17.65) | 55.80(18.74) | |||

| LSCS | 66.17(18.05) | 62.07(16.78) | |||

| Both NVD and LSCS | 64.05(19.58) | 57.51(21.83) | |||

QOL: health related quality of life; NVD: normal vaginal delivery; LSCS: lower segment cesarean section.

∗ QOL among the groups was compared with independent sample t-test in the variables with two categories.

∗∗ QOL among the groups was compared with one-way ANOVA test in the variables with three or more categories.

#Post hoc analysis with Tukey's test; the difference was observed between the following groups.

None – 4-7 children; p=0.03

1-3 children – 4-7 children; p=0.02

Figure 1.

Mean plot for the association between parity and QOL in postmenopausal women (one way ANOVA tukey's test).

Table 5.

Correlation between QOL and evaluated variables of pre- and postmenopausal women (n=350).

| Variable | Premenopausal women (n=184) | Postmenopausal women (n=166) |

|---|---|---|

| Correlation coefficient | Correlation coefficient | |

| Ethnicity a | -0.004 (ns) | 0.01 (ns) |

|

| ||

| Educational statusb | 0.11 (ns) | 0.14 (ns) |

|

| ||

| Employment statusa | -0.02 (ns) | 0.14 (ns) |

|

| ||

| Civil statusa | -0.10 (ns) | -0.08 (ns) |

|

| ||

| Monthly incomea | 0.10 (ns) | 0.24 ∗∗ |

|

| ||

| Living companionb | 0.13 (ns) | 0.03 (ns) |

|

| ||

| Parityb | 0.08 (ns) | -0.21 ∗ |

|

| ||

| Mode of deliveryb | -0.10 (ns) | 0.01 (ns) |

|

| ||

| Psychological symptoms score c | -0.56∗∗∗ | -0.47∗∗∗ |

|

| ||

| Somatovegetative symptoms score c | -0.50∗∗∗ | -0.49∗∗∗ |

|

| ||

| Urogenital symptoms score c | -0.22∗∗ | -0.27∗∗∗ |

|

| ||

| Overall MRS score c | -0.56∗∗∗ | -0.52∗∗∗ |

|

| ||

| Age (years)c | -0.04 (ns) | -0.09 (ns) |

|

| ||

| BMI (kg/m2)c | -0.06 (ns) | -0.05 (ns) |

|

| ||

| WHR c | 0.02 (ns) | -0.08 (ns) |

|

| ||

| Walking score (MET/min/week)c | 0.03 (ns) | 0.14 (ns) |

|

| ||

| Moderate physical activities score (MET/min/week)c | 0.14 (ns) | 0.26∗∗ |

|

| ||

| Vigorous physical activities score (MET/min/week)c | 0.05 (ns) | 0.19∗ |

|

| ||

| Total physical activity score (MET/min/week)c | 0.09 (ns) | 0.27∗∗∗ |

MRS=menopause rating scale, BMI=body mass index, WHR=waist to hip ratio, ns=not significant.

Correlations were Pearson correlation (c) or Spearman rank order correlation (b) or point biserial correlation (a).

Correlations were significant at ∗∗∗∗<0.001, ∗∗∗<0.01 and ∗<0.05.

All the individual scores of menopausal symptoms except dryness of vagina and symptom subscale scores showed negative correlations with the QOL in both pre- and postmenopausal women. Moderate, vigorous, and total physical activity scores showed positive correlations with the QOL of postmenopausal women (Table 5). Adjusting the above associations for current age in both groups and age at menopause and time since menopause in postmenopausal women did not change the strength of associations materially.

In multiple regression analysis, psychological symptoms score and somatovegetative symptoms score remained as main two factors associated with the QOL of premenopausal women accounting for 35% of variance (adjusted R2=0.35). Among the postmenopausal women, somatovegetative symptoms score, psychological symptoms score, moderate and vigorous physical activity scores, and monthly income showed significant associations with the QOL accounting for 38% of variance (adjusted R2=0.38). Psychological symptoms score was the strongest factor associated with the QOL in premenopausal women (R:-0.56, R2=0.31) while somatovegetative symptoms score emerged as the strongest factor in postmenopausal women (R:-0.49, R2=0.24). The above variances remained unchanged even after controlling for possible confounders (age in all and age at menopause and time since menopause in postmenopausal women) in hierarchical multiple regression.

4. Discussion

This community-based cross-sectional survey revealed a high prevalence and severity of menopausal symptoms in postmenopausal women leading to impairment of QOL compared to premenopausal women in Galle District, Sri Lanka. The most frequently annoying menopausal symptoms among pre- and postmenopausal women were psychological and somatovegetative in nature. Joint and muscular discomforts with “severe” to “very severe” intensity and depressive mood in “mild” to “moderate” severity were more prevalent among postmenopausal women. Hot flushes and urogenital complaints, however, were infrequent among them. This led to impairment of overall QOL in postmenopausal women. In postmenopausal women, the QOL was associated with menopausal symptoms, physical activity, and monthly income. In premenopausal women, only the menopausal symptoms were associated with the QOL.

Similar findings of prevalence of menopausal symptoms have been reported in previous studies carried out in Sri Lanka [2, 10] as well as in other different communities [20, 21] including many Asian countries [3, 7, 22–24]. However, studies from the Western countries have reported [4, 9, 20, 25–27] higher occurrence of hot flushes, night sweats, decreased interest in sex, and urogenital problems that were less common in our study.

Several studies [2, 26, 28] have reported that impairment of QOL can be mainly limited to few domains. The women in current study, however, reported impaired QOL in several domains. The negative correlations between menopausal symptoms scores and overall QOL score have been seen earlier [2, 5, 7, 29, 30]. Marital status, educational level, and social and economic level have been observed to positively affect QOL while advanced age and the number of children who live with the family have been observed as negatively affecting factors on the QOL of postmenopausal women [5, 7, 31, 32].

The prevalence of menopausal symptoms may show a geographical variation. In tropical countries such as Sri Lanka, women may not distinguish hot flushes from hot weather spells. Further, the sensitivity of women to menopausal symptoms may be affected by ethnic backgrounds, religious beliefs, geographical variations, cultural variations, and lifestyle factors [28]. Further, as urogenital and sexual issues are not discussed openly in the Asian culture, they might get translated to somatic and psychological symptoms. Also, they might believe those symptoms are a part of ageing.

The impairment of QOL in multiple domains which has been observed could partly be explained with the usage of self-administered survey tools. Participants may have answered many items to express their feelings. Previous studies in Sri Lanka [2, 10] have used interviewer based discussions for data collection and probably did not allow overlap of responses.

Positive association of higher monthly income and negative association of higher number of children in family with the QOL in postmenopausal women are explainable. Higher monthly income would provide better economic background, coping abilities, and positive perceptions and in turn better QOL. More children in the family would add more worries and responsibilities resulting in poor QOL [32]. Further, high level of physical activity is likely to enhance the QOL as physical activity is associated with positive attributes in life. Physical activity has been shown to be a predictor of QOL [33] of postmenopausal women as the postmenopausal women gained weight during this period which again has a negative impact on the QOL [21].

Central and intra-abdominal fat accumulation is relatively higher among postmenopausal women. Higher BMI has shown a negative impact on physical domain of QOL among postmenopausal women [34] while better QOL was seen among thin women [35]. However, in this study, BMI and WHR were not associated with QOL of postmenopausal women.

This study provided valuable information on the enhancement of QOL of middle-aged women in Sri Lanka. We identified that the QOL is mainly impaired by menopausal symptoms such as psychological symptoms, namely, irritability, physical and mental exhaustion, etc. The impact of symptoms that are directly related to the estrogen depletion such as hot flushes (vasomotor symptoms) and urogenital symptoms on the QOL is less. Further, lifestyle factors such as physical activity are vital to enhance the QOL. Therefore, the interventions focused on enhancement of the QOL of middle-aged women should be targeted towards lifestyle changes and behavioral modifications. These lifestyle changes should also include psychological adjustments to menopause and strategies to cope with menopause rather than treating women with HRT or other medications.

We identified several strengths and limitations of this study. We evaluated women aged 30-60 years who were apparently healthy. This approach minimizes the confounding effects of ageing and comorbidities towards the QOL. Further, generalizability of the findings is limited to other areas of the country due to the geographical variations in socioeconomic status among women in Sri Lanka.

5. Conclusions

This study revealed that prevalence of menopausal symptoms and their severity were significantly higher among postmenopausal women compared to premenopausal women. The overall QOL and scores of some domains, namely, physical functioning, role performance due to emotional and physical problems, and comfort (perception of pain), were significantly impaired in postmenopausal women compared to premenopausal women. The psychological symptoms score and somatovegetative symptoms score were associated with the QOL of premenopausal women. In postmenopausal women, somatovegetative symptoms score, psychological symptoms score, moderate and vigorous physical activity scores, and monthly income were significantly associated with the QOL.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express sincere gratitude to funding sources of the study, National Research Council (Grant no – 15-023), Sri Lanka, and Faculty Research Committee, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ruhuna, and all the participants of the study. Further, Mrs. Chithra Ranasinghe, Retired WHO staff member, is also acknowledged for her support in English language editing.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Ethical Approval

The ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethical Review Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Ruhuna, Sri Lanka.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from each study participant before the administration of questionnaire.

Disclosure

This manuscript was derived from the corresponding author's Ph.D. study at University of Ruhuna, Sri Lanka.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Research on the Menopause in the 1990s: Report of a WHO Scientific Group. 1996. http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/41841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waidyasekera H., Wijewardena K., Lindmark G., Naessen T. Menopausal symptoms and quality of life during the menopausal transition in Sri Lankan women. Menopause. 2009;16(1):164–170. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31817a8abd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma S., Mahajan N. Menopausal symptoms and its effect on quality of life in urban versus rural women: a cross-sectional study. Journal of Mid-life Health. 2015;6(1):16–20. doi: 10.4103/0976-7800.153606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenblum C. A., Rowe M. A., Neff D. F., Greenblum J. S. Midlife women: symptoms associated with menopausal transition and early postmenopause and quality of life. Menopause. 2013;20(1):22–27. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31825a2a91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elsabagh E. E. M., Abd Allah E. S. Menopausal symptoms and the quality of life among pre/post-menopausal women from rural area in Zagazig city. Life Science Journal. 2017;9(2):283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kothiyal P., Sharma M. Post menopausal quality of life and associated factors—a review. American Journal of Pharm Research. 2017;3(9):7175–7183. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ibrahim Z. M., Sayed Ahmed W. A., El-Hamid S. A. Prevalence of menopausal related symptoms and their impact on quality of life among Egyptian women. Clinical and Experimental Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2015;42(2):161–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. WHOQOL-BREF: Introduction, Administration, Scoring and Generic Version of The Assessment: Field Trial Version. December 1996. https://www.who.int/mental_health/media/en/76.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greendale G. A., Gold E. B. Lifestyle factors: are they related to vasomotor symptoms and do they modify the effectiveness or side effects of hormone therapy? American Journal of Medicine. 2005;118(2):148–154. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goonaratna C., Fonseka P., Wijeywardene K. Perimenopausal symptoms in Sri Lankan women. Ceylon Medical Journal. 1999;44(2):63–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin W.-Y., Yang W.-S., Lee L.-T., et al. Insulin resistance, obesity, and metabolic syndrome among non-diabetic pre-and post-menopausal women in North Taiwan. International Journal of Obesity. 2006;30(6) 912 doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harlow S. D., Gass M., Hall J. E., et al. Executive summary of the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop + 10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive aging. Menopause. 2012;19(4):387–395. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31824d8f40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hauser G. A., Huber I. C., Keller P. J., Lauritzen C., Schneider H. P. Evaluation of climacteric symptoms (menopause rating scale) Zentralblatt fur Gynakologie. 1994;116(1):16–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneider H. P. G., Heinemann L. A. J., Rosemeier H. P., Potthoff P. Behre HM: the menopause rating scale (MRS): reliability of scores of menopausal complaints. Climacteric. 2000;3(1):59–64. doi: 10.3109/13697130009167600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneider H., Heinemann L., Thiele K. The menopause rating scale (MRS): cultural and linguistic translation into English. Life and Medical Science Online. 2002;3 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ware Jr J. E., Sherbourne C. D. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical care. 1992;30(6):473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gunawardena N. S., Seneviratne R. D. A., Athauda T. Functional outcomes of unilateral lower limb amputee soldiers in two districts of Sri Lanka. Military Medicine. 2006;171(4):p. 283. doi: 10.7205/milmed.171.4.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.IPAQ Research Committee. Guidelines for Data Processing and Analysis of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)–Short And Long Forms. 2005;17 file:///C:/Users/HP/Downloads/GuidelinesforDataProcessingandAnalysisoftheInternationalPhysicalActivityQuestionnaireIPAQShortandLongForms%20(2).pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lohman T. J., Roache A. F., Martorell R. Anthropometric standardization reference manual. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 1992;24(8):p. 952. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jokinen K., Rautava P., Mäkinen J., Ojanlatva A., Sundell J., Helenius H. Experience of climacteric symptoms among 42–46 and 52–56-year-old women. Maturitas. 2003;46(3):199–205. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5122(03)00216-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dennerstein L., Lehert P., Guthrie J. The effects of the menopausal transition and biopsychosocial factors on well-being. Archives of Women's Mental Health. 2002;5(1):15–22. doi: 10.1007/s007370200018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Punyahotra S., Dennerstein L., Lehert P. Menopausal experiences of Thai women. Part 1: symptoms and their correlates. Maturitas. 1997;26(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5122(96)01058-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sagdeo M., Arora D. Menopausal Symptoms: A Comparative Study in Rural and Urban Women. 2011. https://www.jkscience.org/archive/volume131/Menopausal%20Symptoms%20A%20Comparative%20Study%20in%20Rural%20and%20Urban%20Women.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ashrafi M., Kazemi A. S., Malekzadeh F., et al. Symptoms of Natural Menopause among Iranian Women Living in Tehran, Iran. 2010. http://journals.ssu.ac.ir/ijrmnew/article-1-164-en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whiteley J., DiBonaventura M. d., Wagner J.-S., Alvir J., Shah S. The impact of menopausal symptoms on quality of life, productivity, and economic outcomes. Journal of Women's Health. 2013;22(11):983–990. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.3719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blumel J. E., Castelo-Branco C., Binfa L., et al. Quality of life after the menopause: a population study. Maturitas. 2000;34(1):17–23. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5122(99)00081-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dennerstein L., Dudley E. C., Hopper J. L., Guthrie J. R., Burger H. G. A prospective population-based study of menopausal symptoms. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2000;96(3):351–358. doi: 10.1097/00006250-200009000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fu S. Y., Anderson D., Courtney M. Cross-cultural menopausal experience: comparison of australian and taiwanese women. Nursing & Health Sciences. 2003;5(1):77–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2018.2003.00139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Özkan S., Alataş E. S., Zencir M. Women’s quality of life in the premenopausal and postmenopausal periods. Quality of Life Research. 2005;14(8):1795–1801. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-5692-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moustafa M., Ali R., Taha S. M. Impact of menopausal symptoms on quality of life among women's in Qena City. Egyptian Journal of Nursing. 2015;10(1) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daley A., MacArthur C., Stokes-Lampard H., McManus R., Wilson S., Mutrie N. Exercise participation, body mass index, and health-related quality of life in women of menopausal age. British Journal of General Practice. 2007;57(535):130–135. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuh D., Hardy R. Women's health in midlife: findings from a British birth cohort study. British Menopause Society Journal. 2003;9(2):55–60. doi: 10.1258/136218003100322206.12844426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elavsky S. Physical activity, menopause, and quality of life: the role of affect and self-worth across time. Menopause. 2009;16(2):265–271. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31818c0284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lynch C. P., McTigue K. M., Bost J. E., et al. Excess weight and physical health-related quality of life in postmenopausal women of diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds. Journal of Women's Health. 2010;19(8):1449–1458. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laferrère B., Zhu S., Clarkson J. R., et al. Race, menopause, health-related quality of life, and psychological well-being in obese women. Obesity Research. 2002;10(12):1270–1275. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.