Abstract

Alpha-synuclein (SNCA) is a major risk gene for Parkinson's disease (PD), and increased SNCA gene dosage results in a parkinsonian syndrome in affected families. We found that methylation of human SNCA intron 1 decreased gene expression, while inhibition of DNA methylation activated SNCA expression. Methylation of SNCA intron 1 was reduced in DNA from sporadic PD patients' substantia nigra, putamen, and cortex, pointing toward a yet unappreciated epigenetic regulation of SNCA expression in PD.

Introduction

Alpha-synuclein (SNCA) is a key component of Lewy bodies found in Parkinson's disease (PD) patients (Spillantini et al., 1997; Braak et al., 2003). Point mutations and multiplications of SNCA cause familial parkinsonian syndromes with high penetrance (Singleton et al., 2003). Several studies suggest that the SNCA gene harbors significant risk haplotypes for sporadic PD too (Mizuta et al., 2006). Comprehensive promoter analyses and recent studies of SNCA mRNA levels in dopaminergic neurons strengthened the hypothesis that genotype-dependent regulatory mechanisms and increased expression of SNCA could contribute to the risk of sporadic PD (Maraganore et al., 2006; Gründemann et al., 2008).

Beyond the actual code of a regulatory DNA sequence, several additional levels of epigenetic transcriptional control have become apparent recently (Suzuki and Bird, 2008). Methylation of CpG dinucleotides is a prime epigenetic mechanism and a frequent biochemical modification of DNA in the human genome. Hypermethylation of CpG-rich regions [or CpG “islands” (CGIs)] is often found in regulatory 5′ regions, and methylation-dependent silencing of tumor suppressor genes is a widely acknowledged mechanism in the pathogenesis of cancer (Feinberg, 2007; Suzuki and Bird, 2008). Aberrant DNA methylation has also been associated with psychiatric conditions and might constitute a pathogenic mechanism for other diseases as well (Feinberg, 2007).

We investigated whether aberrant methylation might contribute to a presumed dysregulation of SNCA expression in sporadic PD.

Materials and Methods

WEBGENE was used for the prediction of CGIs, and the TESS (Transcription Element Search Software, http://www.cbil.upenn.edu/tess) program for identification of putative transcription factor (TF) binding sites and proscan (version 1.7, http://www-bimas.cit.nih.gov/molbio/proscan/) were used for prediction of putative promoter regions.

SK-N-SH cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (PAA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS Gold, PAA), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (PAA) at 37°C and 5% CO2. For treatment with 5-aza-2′ deoxycytidine (Aza; A3656, Sigma), 5 × 106 cells were seeded in 10 cm plates, cultured overnight, and treated with 10 μm Aza (dissolved in DMSO) or with DMSO as control. The treatment was repeated (including medium replacement) every 8 h for 24 or 48 h. Cells were harvested into three portions for isolation of DNA, RNA, and proteins.

DNA isolation and bisulfate treatment was performed as previously described (Pieper et al., 2008). Bisulfite-treated DNA was amplified using SYN-PromF AAAATTTTGAAGATATTTGAATTAAAG/SYN-PromR-CTAATCCTCCTCCTTCTCCTTCTC and SYN-IntF-GGAGTTTAAGGAAAGAGATTTGATT/SYN-IntR-CAAACAACAAACCCAAATATAATAA, specifically designed for the bisulfite-treated DNA. PCR products (SNCA(−2079/−1507) and SNCA(−926/−483)) (Fig. 1b) were cloned into pCR 2.1 TOPO vector (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's instructions. Plasmid DNA was isolated from at least 10 clones per region (Wizard Plus SV Minipreps, Promega), sequenced using vector-specific primers and the Big Dye Terminator v1.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems), and analyzed on an ABI PRISM 310 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Quality control for DNA methylation data was performed using BiQ (software tool for DNA methylation analysis; http://biq-analyzer.bioinf.mpi-inf.mpg.de/).

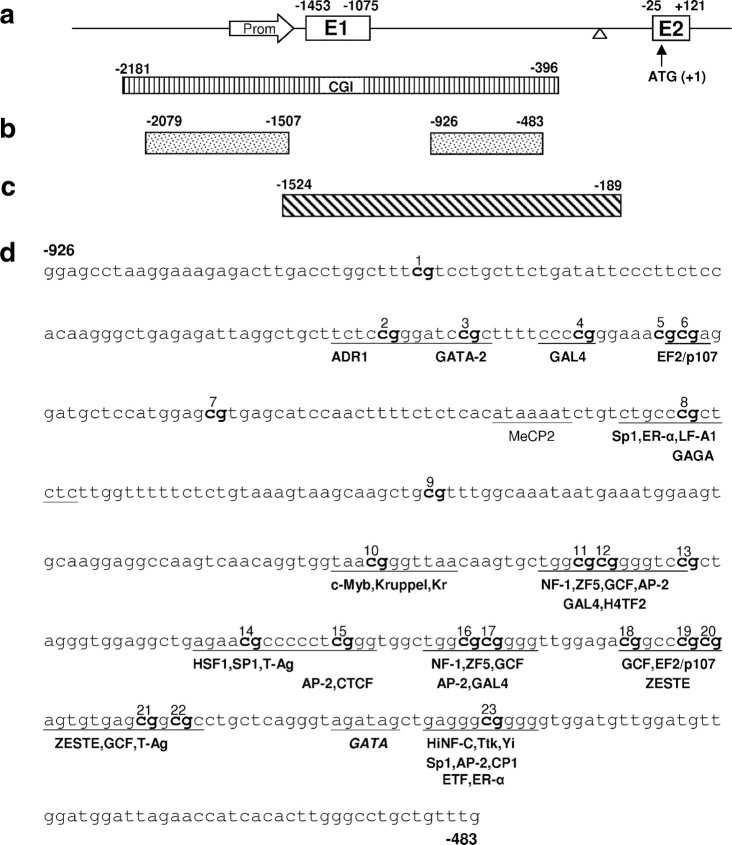

Figure 1.

The SNCA region of interest. a, Schematic drawing of the 5′ region of SNCA with exons 1 and 2 (boxes) and the 5′ UTR and intron 1 (line). The arrow indicates the position of the putative core promoter; the triangle indicates the position of a rudimentary TATA box. Dimension of the CGI is depicted by the stripped box. Numbers are relative to the translation start site (ATG + 1). b, Fragments SNCA(−2079/−1507) (promoter) and SNCA(−926/−483) (intron) were used for bisulfite sequencing. c, Fragment SNCA(−1524/−189) was used for reporter assays. d, Predicted transcription factor binding sites within SNCA(−926/−483) (intron) adjacent to CpG dinucleotides.

RNA was isolated with the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For reverse transcription, 1 μg of total RNA and m-MLV Reverse Transcriptase, RNase H Minus (Promega) was used with oligo dT and random hexamer primers according to the manufacturer's instruction. Quantitative PCR was performed in triplicate with SYBR Green JumpStart Taq ReadyMix (Sigma) and SNCA-primers (SNCA-F_GGACCAGTTGGGCAAGAATG and SNCA-R_GGGCACATTGGAACTGAGCAC) on an Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System using 2 μl of 1:10 diluted cDNA for each reaction.

Protein extracts were prepared by resuspending the cells in lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 120 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, 0.5% NP-40, 20 μg/ml aprotinin, 20 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 mm PMSF, 1× protein inhibitor mix Complete Mini (Roche Diagnostics). After centrifugation, 50 μg of protein per lane was separated by SDS-PAGE, and detection was performed with the ECL Western blotting detection system (GE Healthcare) using secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase. We used antibodies at the following dilutions: anti-Synuclein (1:2000; catalog #610786, BD Bioscience) and goat anti-mouse (1:2000; catalog #115-035-003, Jackson ImmunoResearch).

Genomic DNA from control lymphocytes was used as a template for PCR (LYMF-GAGAAGGAGGAGGACTAGGAGG and LYMR-AGCATCTCCCATCTTGG), and the PCR product was inserted into pGL4.23(luc/min P) vector (Promega). The resulting construct (SNCA(−1524/−189)) expressed the Firefly luciferase under the control of the SNCA exon 1/intron 1 fragment (Fig. 1c). The reverse insertion of the fragment into pGL4.23(luc/min P) served as a control. The luciferase experiment was performed in triplicate and repeated at least four times.

For in vitro methylation, 15 μg of the reporter constructs was incubated with 32 U of SssI (CpG) methylase (New England Biolabs), supplemented with 32 mm S-adenosylmethionine (SAM, New England Biolabs), and incubated overnight at 37°C. The reaction was purified using Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System (Promega) following the manufacturer's instructions.

HeLa cells were cultured as SK-N-SH cells (see above). A total of 1 × 106 cells per well were seeded on 24 well plates and transfected with the indicated luciferase reporter constructs with/without in vitro methylation using Lipofectamine 2000 Reagent (Invitrogen) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Renilla luciferase (pRL-CMV, Promega) was cotransfected to normalize for transfection efficiency. Cells were harvested 24 h after transfection and luciferase activities were measured by the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) in a Centro LB 960 luminometer (Berthold Technologies).

DNA from substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) and cortex from six PD patients (three males, three females; mean age, 79.3 ± 5.6 years) and six neurologically healthy control individuals (four males, two females; mean age, 75.8 ± 6.2 years) (provided by the GermanBrainNet), and DNA from putamen from an additional 14 individuals (PD: 3 males, 3 females; mean age 77.0 ± 5.7 years; controls: 2 males, 6 females; mean age 78.0 ± 4.1 years) (provided by Prof. P. Riederer, University of Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany) was used for analysis. The reported concomitant diseases and the causes of death revealed no systematic differences between the control group and the PD patients (comprehensive clinical information is provided in supplemental Table 1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). DNA was extracted from frozen tissue using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer's instructions. Bisulfite sequencing of SNCA(−926/−483) was performed as described above. Plasmid DNA was isolated from at least 10 clones per individual per region. Independent replication experiments were performed on cortex-derived DNA from an additional 10 clones per individual.

Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA.

Results

Methylation status of SNCA intron 1 affects SNCA expression

The human SNCA gene contains a CpG island extending from −2181 to −396 upstream from the translation start site (Fig. 1a), enclosing the canonical promoter and a putative concealed promoter in intron 1 (−1074 to −26), which has been linked to NGF/basic FGF-mediated Snca expression in rodents (Xia et al., 2001; Clough and Stefanis, 2007). Further supporting the significance of intron 1 in Snca expression, GATA TF binding in intron 1 has been shown to regulate Snca transcription (Scherzer et al., 2008).

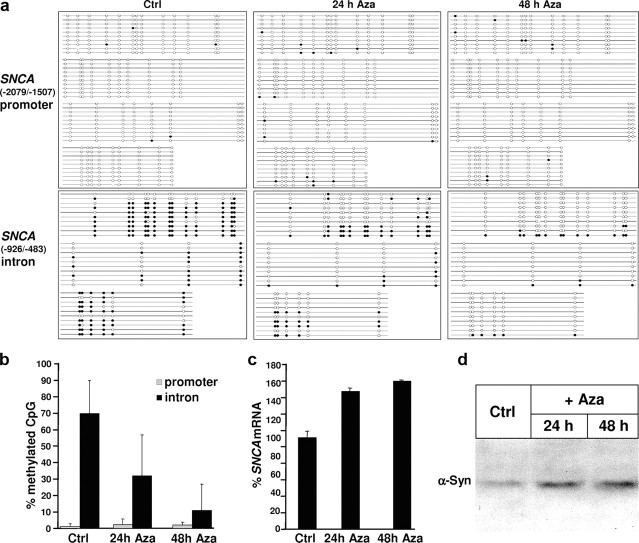

We therefore analyzed the methylation state of SNCA in a promoter region fragment and in an intronic sequence stretch of SK-N-SH cells. Bisulfite sequencing of SNCA(−2079/−1507) (core promoter) and SNCA(−926/−483) (intron 1) (Fig. 1b), revealed that only 1.4 ± 1.5% of the 40 CpG sites in SNCA(−2079/−1507) were methylated, in contrast to 70 ± 20.3% of the 23 CpG sites in SNCA(−936/−483) (Fig. 2a,b; supplemental Table 2, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). To investigate the functional significance of intron 1 methylation, we used the U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved DNA methylation inhibitor Aza. Aza treatment for 24 and 48 h reduced the methylation state of SNCA(−926/−483), while no effect on the marginal methylation of SNCA(−2079/−1507) became apparent (Fig. 2a,b). The Aza-induced decreased methylation of SNCA(−926/−483) resulted in increased amounts of SNCA mRNA and increased SNCA protein expression (Fig. 2c,d).

Figure 2.

Status of SNCA methylation in SK-N-SH cells and impact on expression. a, SK-N-SH cells were incubated with DMSO [control (Ctrl)] or 10 μm Aza for 24 and 48 h, respectively, and isolated DNA was used for bisulfite sequencing of SNCA(−2079/−1507) (promoter) and SNCA(−926/−483) (intron); 10 independent clones for each condition were analyzed by bisulfite sequencing. The lollipop diagram with unmethylated CpG sites (open circles) and methylated CpG sites (closed circles) illustrates the higher degree of methylation in SNCA(−926/−483) (intron) compared with SNCA(−2079/−1507) (promoter) and the decrease of methylated CpG in SNCA(−926/−483) (intron) after addition of Aza. b, After 48 h of Aza treatment, the fraction of methylated CpGs is reduced by ∼60% in SNCA(−926/−483) (intron). c, Treatment with Aza induced a time-dependent increase of SNCA expression exceeding 50% of Ctrl. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed in triplicate and presented as the mean ± SD. d, Representative Western blot with anti-synuclein antibody demonstrates an increase of synuclein protein after addition of Aza too.

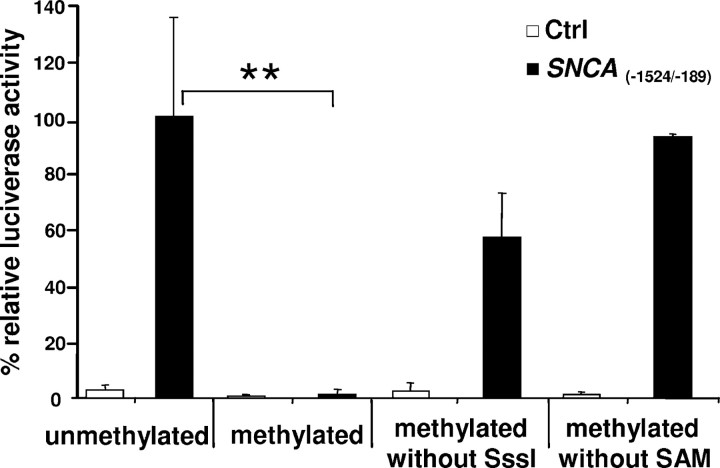

Promoter activity of intron 1 is influenced by methylation

Next, we analyzed the impact of methylation on gene expression activity in luciferase reporter experiments. SNCA(−1530/−193), a reporter construct chosen to comprise intron 1 (containing 71 CpG dinucleotides), displayed significant promoter activity (>30-fold higher activity compared with the construct with the inverted insert SNCA(−193/−1530), which served as control) (Fig. 3). After treatment with SssI CpG-methyl transferase, which selectively adds a methyl group to all cytosine residues within CpG dinucleotides, the activity of the methylated construct was decreased to control levels (Fig. 3). When SssI or SAM as the methyl group donor was omitted, the promoter activity was not altered significantly.

Figure 3.

Promoter activity of SNCA(−1524/−189) in HeLa cells. In vitro methylation of the reporter construct SNCA(−1524/−189) reduced relative luciferase activity by 98.5% (**p ≤ 0.01, one-way ANOVA). Absence of SssI or SAM from the in vitro methylation reaction minimized reduction. Ctrl, Construct with the inverted insert.

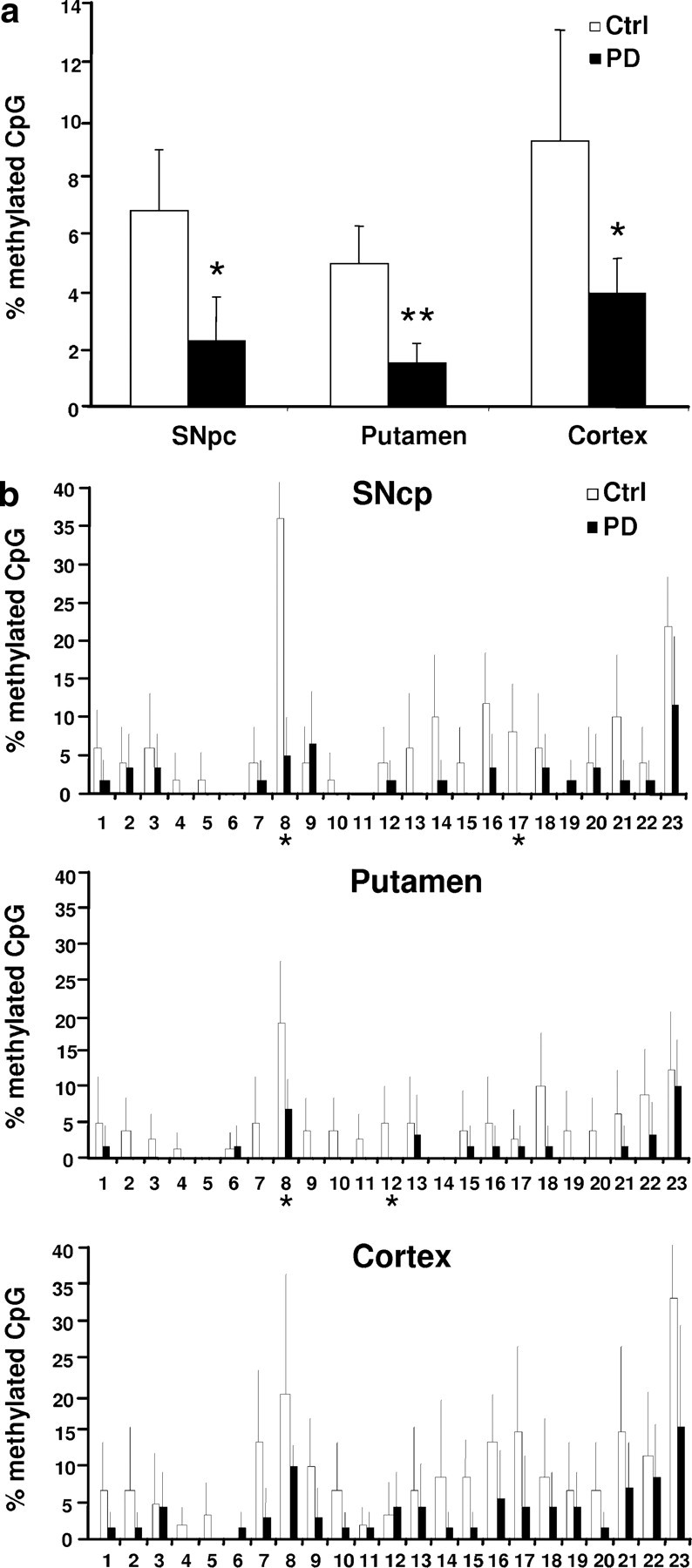

Methylation of SNCA intron 1 is reduced in DNA from PD patients

To investigate whether epigenetic changes might contribute to a presumed dysregulation of SNCA expression in sporadic PD, we analyzed DNA from three different regions (SNpc, putamen, and cortex) in 37 tissue samples from 12 PD patients and 14 controls. We found significantly fewer methylated CpG sites in PD patients' DNA (Fig. 4a; supplemental Table 3, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). The mean methylation rate of SNCA(−926/−483) (intron 1) in human brain was 10-fold lower compared with SK-N-SH cells (7 vs 70%), yet, similar to SK-N-SH cells, SNCA(−2079/−1507) (promoter) displayed only sparse methylation (∼1.5%; data not shown). The SNCA intron 1 methylation pattern varied considerably between tissues and individuals (Fig. 4b). Despite this variability, differences between PD and control were found not only in the group comparison (Fig. 4a) but also in SNpc and putamen DNA at specific positions (8, 12, and 17) within intron 1, located within predicted consensus binding sites of TFs (Figs. 1d, 4b). Except for positions 1, 5, 7, and 9, all CpG sites were located within predicted TF binding sites (Fig. 1d), suggesting that SNCA intron 1-mediated transcriptional regulation may depend on the binding of specific TFs.

Figure 4.

Status of SNCA(−926/−483) methylation in human brain. a, Mean percentages (±SD) of methylated CpG sites summed up over all 23 CpG sites analyzed. PD patients' DNA was hypomethylated compared with the neurologically healthy individuals in all analyzed brain regions. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01. b, Detailed comparison of the methylation of SNCA(−926/−483) in DNA from SNpc, putamen, and cortex of PD and neurologically healthy individuals. Percentage of methylated CpG at the particular position in the three different brain regions. Asterisks indicate significant (p ≤ 0.05, one-way ANOVA) hypomethylation in PD patients compared with control (mean ± SD of at least 10 clones per individual per CpG position analyzed by bisulfite sequencing).

Discussion

We identified SNCA(−1524/−189) in intron 1 as a methylation-dependent, transcriptionally active region of the human SNCA gene and found that SNCA(−926/−483) is hypomethylated in sporadic PD patients' brains. A yet unappreciated epigenetic control of SNCA expression might contribute to the presumed dysregulation of SNCA expression in PD.

The finding that the methylation of intron 1 modulates human SNCA transcriptional activity expands recent studies, which independently identified expression-relevant GATA binding sites and NGF response elements, respectively, in intron 1 of rodent Snca (Clough and Stefanis, 2007; Scherzer et al., 2008). In addition, promoter prediction software identified a rudimentary TATA box and several TF binding sites immediately upstream from the ATG (+1) in human SNCA intron 1 (Fig. 1a,d). In contrast to exon 1/intron 1 of the rat Snca gene, which harbors only 19 CpG sites, the human SNCA exon 1/intron 1 carries 66 CpG sites; thus, changes in SNCA methylation may have more pronounced regulatory effects in humans compared with rodents. The possibility that intron 1 serves to generate a relevant fraction of SNCA transcripts is further supported by the original work by Uéda et al. (1993), who identified a principal SNCA transcript in human brain ∼1.500 bp in size, which corresponds well to the size of exons 2 to 6 (1.522 bp). Inclusion of the canonical exon 1, though, would extend the predicted mRNA length up to 1.902 bp. Thus, the canonical exon 1 and intron 1 may serve regulatory, perhaps methylation-sensitive, functions.

This is particularly intriguing in the light of the second principal finding, i.e., that intron 1 SNCA(−926/−483) was found to be hypomethylated in sporadic PD patients' brains. Hypomethylation was consistently observed across the analyzed CpG sites in all three brain regions investigated, although the SNCA methylation patterns varied considerably between tissues and individuals. Regional variation of methylation within the brain has also been found previously for the tumor necrosis factor-α promoter (Pieper et al., 2008), and tissue-specific variation in DNA methylation levels was found along human chromosome 1 (De Bustos et al., 2009).

The differentially methylated CpG sites are associated with predicted TF binding sites, suggesting that reduced methylation could promote SNCA expression in PD brain. We propose that less methylated SNCA is more likely to be actively transcribed in response to particular stimuli. Whether SNCA mRNA levels are indeed increased in PD patients' brains has been addressed in several previous studies, and although some studies failed to detect differences in SNCA mRNA levels, others indicated that at least SNpc tissue in PD contained more SNCA mRNA (Chiba-Falek et al., 2006). This was confirmed in a recent study using laser dissecting microscopy of PD SNpc neurons (Gründemann et al., 2008).

DNA methylation turns out to be a highly dynamic process (Feinberg, 2007). Major age-dependent changes of gene methylation have been reported not only in neonatal development but also in the adult CNS, where distinct age-dependent changes became apparent in subsets of cortical neurons (Siegmund et al., 2007). In addition to classic monogenetic epigenetic disease, i.e., Beckwith–Wiedeman and Prader–Willi syndromes, recent data point to an epigenetic component also of other neuropsychiatric disorders, notably in Rett syndrome (Chahrour and Zoghbi, 2007). The decreased methylation of SNCA intron 1(−926/−483) could contribute to increased expression of SNCA in PD patients' brains, as SNCA(−1524/−189) acted as a methylation-dependent, hitherto unappreciated, transcriptionally active region of the human SNCA gene.

At present, we can only speculate about the cause of this hypomethylation. An inherited damage of the methylation machinery appears rather unlikely in the light of recent whole-genome association studies that identified only SNCA and the MAPT regions as major denominators of PD risk (Simón-Sánchez et al., 2009; Edwards et al., 2010). Consequently, in the adult PD brain we did not find an overt loss of the maintenance methylase DNMT1 (Kaut et al., 2009). Whether a disturbance of the de novo methyltransferases DNMT 3a and 3b early in the development of the CNS could contribute to the observed changes remains unknown.

One might presume that methylation could be affected by environmental factors. Nutrition, i.e., famine, has profound effects on DNA methylation, and deficiency in folate and methionine, which are necessary for the biosynthesis of methyl donors for methylcytosin, can lead to aberrant imprinting of IGF2 (Waterland et al., 2006). Although we have shown previously that a methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) genotype, which affects methionine 1-carbon metabolism, modulates age of onset in PD (Wüllner et al., 2005), we found no difference in the methylation of the imprinted IGF2 gene in PD (Kaut et al., unpublished observations). Other lines of evidence suggest that critical psychosocial events (e.g., early life stress) and environmental exposures may induce lasting epigenetic marks (Christensen et al., 2009; Murgatroyd et al., 2009). The methylation state of SNCA intron 1 might constitute such a mark, adding an additional level of complexity to a graded (epi-)genetic risk for PD.

Footnotes

This study was supported in part by the intramural Bonfor research program of the Universitätsklinikum Bonn (A.J. and U.W.), the Hans-Tauber Stiftung of the Deutsche Parkinson Vereinigung, and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Wu184/9-1). A.J. is a scholar at the University of Aleppo, Aleppo, Syrian Arab Republic. We thank the German Brain Bank and Peter Riederer at University of Würzburg for providing tissue samples, Drs. H. Pieper and A. Waha for helpful discussions, and Hassan Khazneh, Sabine Proske-Schmitz, and Anne Hanke for technical support.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rüb U, de Vos RA, Jansen Steur EN, Braak E. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:197–211. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chahrour M, Zoghbi HY. The story of Rett syndrome: from clinic to neurobiology. Neuron. 2007;56:422–437. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba-Falek O, Lopez GJ, Nussbaum RL. Levels of alpha-synuclein mRNA in sporadic Parkinson disease patients. Mov Disord. 2006;21:1703–1708. doi: 10.1002/mds.21007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen BC, Houseman EA, Marsit CJ, Zheng S, Wrensch MR, Wiemels JL, Nelson HH, Karagas MR, Padbury JF, Bueno R, Sugarbaker DJ, Yeh RF, Wiencke JK, Kelsey KT. Aging and environmental exposures alter tissue-specific DNA methylation dependent upon CpG island context. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000602. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough RL, Stefanis L. A novel pathway for transcriptional regulation of alpha-synuclein. FASEB J. 2007;21:596–607. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7111com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bustos C, Ramos E, Young JM, Tran RK, Menzel U, Langford CF, Eichler EE, Hsu L, Henikoff S, Dumanski JP, Trask BJ. Tissue-specific variation in DNA methylation levels along human chromosome 1. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2009;2:7. doi: 10.1186/1756-8935-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards TL, Scott WK, Almonte C, Burt A, Powell EH, Beecham GW, Wang L, Züchner S, Konidari I, Wang G, Singer C, Nahab F, Scott B, Stajich JM, Pericak-Vance M, Haines J, Vance JM, Martin ER. Genome-wide association study confirms SNPs in SNCA and the MAPT region as common risk factors for Parkinson disease. Ann Hum Genet. 2010;74:97–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2009.00560.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg AP. Phenotypic plasticity and the epigenetics of human disease. Nature. 2007;447:433–440. doi: 10.1038/nature05919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gründemann J, Schlaudraff F, Haeckel O, Liss B. Elevated α-synuclein mRNA levels in individual UV-laser-microdissected dopaminergic substantia nigra neurons in idiopathic Parkinson's disease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:e38. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaut O, Majores M, Wuellner U. DNMT1 is expressed in neurons of Parkinson's disease patients' brains. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 2009;35 532.23. [Google Scholar]

- Maraganore DM, de Andrade M, Elbaz A, Farrer MJ, Ioannidis JP, Krüger R, Rocca WA, Schneider NK, Lesnick TG, Lincoln SJ, Hulihan MM, Aasly JO, Ashizawa T, Chartier-Harlin MC, Checkoway H, Ferrarese C, Hadjigeorgiou G, Hattori N, Kawakami H, Lambert JC, et al. Collaborative analysis of alpha-synuclein gene promoter variability and Parkinson disease. JAMA. 2006;296:661–670. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.6.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuta I, Satake W, Nakabayashi Y, Ito C, Suzuki S, Momose Y, Nagai Y, Oka A, Inoko H, Fukae J, Saito Y, Sawabe M, Murayama S, Yamamoto M, Hattori N, Murata M, Toda T. Multiple candidate gene analysis identifies alpha-synuclein as a susceptibility gene for sporadic Parkinson's disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:1151–1158. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murgatroyd C, Patchev AV, Wu Y, Micale V, Bockmühl Y, Fischer D, Holsboer F, Wotjak CT, Almeida OF, Spengler D. Dynamic DNA methylation programs persistent adverse effects of early-life stress. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1559–1566. doi: 10.1038/nn.2436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieper HC, Evert BO, Kaut O, Riederer PF, Waha A, Wüllner U. Different methylation of the TNF-alpha promoter in cortex and substantia nigra: implications for selective neuronal vulnerability. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;32:521–527. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherzer CR, Grass JA, Liao Z, Pepivani I, Zheng B, Eklund AC, Ney PA, Ng J, McGoldrick M, Mollenhauer B, Bresnick EH, Schlossmacher MG. GATA transcription factors directly regulate the Parkinson's disease-linked gene alpha-synuclein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:10907–10912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802437105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegmund KD, Connor CM, Campan M, Long TI, Weisenberger DJ, Biniszkiewicz D, Jaenisch R, Laird PW, Akbarian S. DNA methylation in the human cerebral cortex is dynamically regulated throughout the life span and involves differentiated neurons. PLoS One. 2007;2:e895. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simón-Sánchez J, Schulte C, Bras JM, Sharma M, Gibbs JR, Berg D, Paisan-Ruiz C, Lichtner P, Scholz SW, Hernandez DG, Krüger R, Federoff M, Klein C, Goate A, Perlmutter J, Bonin M, Nalls MA, Illig T, Gieger C, Houlden H, et al. Genome-wide association study reveals genetic risk underlying Parkinson's disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1308–1312. doi: 10.1038/ng.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton AB, Farrer M, Johnson J, Singleton A, Hague S, Kachergus J, Hulihan M, Peuralinna T, Dutra A, Nussbaum R, Lincoln S, Crawley A, Hanson M, Maraganore D, Adler C, Cookson MR, Muenter M, Baptista M, Miller D, Blancato J, et al. Alpha-Synuclein locus triplication causes Parkinson's disease. Science. 2003;302:841. doi: 10.1126/science.1090278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillantini MG, Schmidt ML, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Jakes R, Goedert M. Alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature. 1997;388:839–840. doi: 10.1038/42166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki MM, Bird A. DNA methylation landscapes: provocative insights from epigenomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:465–476. doi: 10.1038/nrg2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uéda K, Fukushima H, Masliah E, Xia Y, Iwai A, Yoshimoto M, Otero DA, Kondo J, Ihara Y, Saitoh T. Molecular cloning of cDNA encoding an unrecognized component of amyloid in Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:11282–11286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterland RA, Lin JR, Smith CA, Jirtle RL. Post-weaning diet affects genomic imprinting at the insulin-like growth factor 2 (Igf2) locus. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:705–716. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wüllner U, Kölsch H, Linnebank M. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase in Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:972–973. doi: 10.1002/ana.20696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y, Saitoh T, Uéda K, Tanaka S, Chen X, Hashimoto M, Hsu L, Conrad C, Sundsmo M, Yoshimoto M, Thal L, Katzman R, Masliah E. Characterization of the human alpha-synuclein gene: genomic structure, transcription start site, promoter region and polymorphisms. J Alzheimers Dis. 2001;3:485–494. doi: 10.3233/jad-2001-3508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]