Abstract

The periodic presentation of a sensory stimulus induces, at certain frequencies of stimulation, a sustained electroencephalographic response known as steady-state evoked potential (SS-EP). In the somatosensory, visual, and auditory modalities, SS-EPs are considered to constitute an electrophysiological correlate of cortical sensory networks resonating at the frequency of stimulation. In the present study, we describe and characterize, for the first time, SS-EPs elicited by the selective activation of skin nociceptors in humans. The stimulation consisted of 2.3-s-long trains of 16 identical infrared laser pulses (frequency, 7 Hz), applied to the dorsum of the left and right hand and foot. Two different stimulation energies were used. The low energy activated only C-nociceptors, whereas the high energy activated both Aδ- and C-nociceptors. Innocuous electrical stimulation of large-diameter Aβ-fibers involved in the perception of touch and vibration was used as control. The high-energy nociceptive stimulus elicited a consistent SS-EP, related to the activation of Aδ-nociceptors. Regardless of stimulus location, the scalp topography of this response was maximal at the vertex. This was noticeably different from the scalp topography of the SS-EPs elicited by innocuous vibrotactile stimulation, which displayed a clear maximum over the parietal region contralateral to the stimulated side. Therefore, we hypothesize that the SS-EPs elicited by the rapid periodic thermal activation of nociceptors may reflect the activation of a network that is preferentially involved in processing nociceptive input and may thus provide some important insight into the cortical processes generating painful percepts.

Introduction

In 1976, Carmon et al. showed that infrared lasers can be used to activate skin nociceptors selectively and synchronously enough to elicit measurable event-related brain potentials (ERPs) in the human electroencephalogram (EEG). After this seminal study, a large number of investigators have relied on the recording of laser-evoked potentials (LEPs) to study how the human brain processes nociceptive input, both in healthy individuals and disease (Treede et al., 1999; Garcia-Larrea et al., 2003; Bushnell and Apkarian, 2005). Source analysis studies have suggested that LEPs reflect activity originating from an extensive array of cortical structures, including bilateral operculo-insular and anterior cingulate cortices, a finding that has been corroborated by magnetoencephalography, intracerebral recordings, as well as functional magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography (Peyron et al., 1999; Frot and Mauguière, 2003; Garcia-Larrea et al., 2003; Kakigi et al., 2005).

A number of investigators have suggested that LEPs reflect at least partially the neural processes by which nociceptive inputs are specifically transformed in a painful percept (Treede et al., 1988; Baumgärtner et al., 2006). For this reason, it has been hypothesized that LEPs constitute a reliable approach to study how pain is “represented” in the brain (Treede et al., 2000). However, there is also growing evidence indicating that the largest part of LEPs could reflect cortical activity that is unspecific for nociception, and related to multimodal cognitive processes involved in the orientation of attention toward the occurrence of salient sensory events (for review, see Iannetti and Mouraux, 2010; Legrain et al., 2011). Hence, novel approaches are needed to identify brain responses that are more closely related to nociceptive processing (Stowell, 1984b).

In 1966, Regan described the recording of steady-state evoked potentials (SS-EPs) as an alternative approach to characterize stimulus-evoked activity in the EEG (Regan, 1966, 1989). Unlike conventional transient ERPs, which reflect a phasic cortical response triggered by the occurrence of a brief stimulus, SS-EPs reflect a sustained cortical response induced by the long-lasting periodic repetition of a sensory stimulus (Vialatte et al., 2010). These steady-state responses are thought to result from an entrainment or resonance of a population of neurons responding to the stimulus at the frequency of stimulation (Herrmann, 2001; Muller et al., 2001; Vialatte et al., 2010). A large number of studies have used this approach to explore the cortical activity involved in processing other sensory modalities and have shown that this technique is effective to capture neural activity related to sensory processing, originating mainly from primary sensory cortices (Snyder, 1992; Pantev et al., 1996; Kelly and Folger, 1999; Tobimatsu et al., 1999; Plourde, 2006; Srinivasan et al., 2006; Giabbiconi et al., 2007; Vialatte et al., 2010).

The aim of the present study was to identify, for the first time, SS-EPs elicited by the periodic stimulation of nociceptive afferents and, thereby, open a new window for studying the cortical processing related to pain perception in humans.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Eight healthy volunteers (five males and three females, seven right-handed; aged 22–35 years) took part in the study. They had no history of neurological, psychiatric, or chronic pain disorders, and no recent history of psychotropic or analgesic drug use. Before the experiment, they were familiarized with the experimental setup and exposed to a small number of test stimuli (three to five stimuli at each stimulus location). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was approved by the local ethics committee.

Steady-state thermal stimulation of Aδ- and C-nociceptors

At present, infrared laser stimulation of the skin constitutes the most reliable method to activate selectively and synchronously Aδ- and C-fiber skin nociceptors (Plaghki and Mouraux, 2003, 2005). The high-energy output of the laser allows heating the skin above the threshold of nociceptors in just a few milliseconds. However, the slow passive cooling of the skin implies that the temperature returns to baseline only after several seconds. Therefore, because a requirement for the recording of SS-EPs is the ability to deliver a large number of nociceptive stimuli at a high repetition rate, an experimental setup was devised to allow rapidly displacing the target of the laser beam, such that the repeated stimuli would not be delivered to the same skin spot and, thereby, avoid skin overheating, nociceptor sensitization, and/or nociceptor habituation.

Pulses of radiant heat (stimulus duration, 20 ms) were generated by a CO2 laser (wavelength, 10.6 μm) designed and built in the Department of Physics of the Université catholique de Louvain. At the energies used in the present study, this laser is able to generate laser pulses with a highly reproducible energy output (variance from trial to trial, <1%) (Plaghki et al., 1994). The irradiance profile of the laser beam has a Gaussian shape. At target site, beam radius was 2.5 mm (defined as the distance from the beam axis where the radiant energy is reduced to 13.5% of the maximum energy).

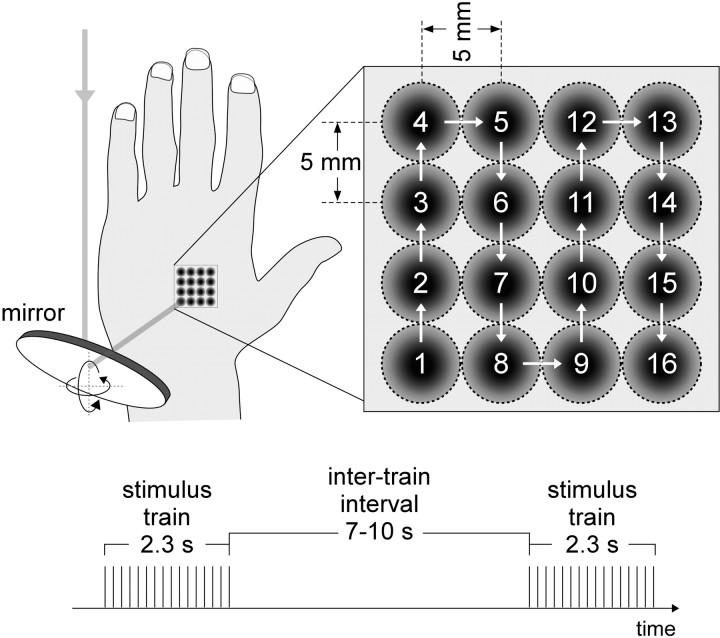

The laser stimuli were applied in trains of 16 consecutive laser pulses, using a repetition rate of 7 Hz (train duration, 2.3 s). The target of the laser was displaced immediately after each pulse, using a flat mirror set on a two-axis computer-controlled device powered by two high-speed servo-motors (HS-422; Hitec RCD; angular speed, 60°/160 ms) (Fig. 1, left panel). The displacement followed a 4 × 4 zigzag path, such that the same spot was stimulated only once in each train (Fig. 1, right panel). The distance between two consecutive stimuli was ∼5 mm. After each train, the position of the laser target (i.e., the position of the first stimulus of the following train) was displaced to a random position on the hand dorsum. The intertrain interval was varied between 7 and 10 s, using a rectangular distribution.

Figure 1.

Rapid periodic stimulation of Aδ- and C-fiber skin nociceptors. Thermal nociceptive CO2 laser stimuli were applied in trains to the left and right hand and foot dorsum (beam diameter at target site, 5 mm). Each train lasted 2.3 s and consisted of 16 consecutive laser pulses applied at a frequency of 7 Hz. The intertrain interval was 7–10 s. To avoid skin overheating, the target of the laser was displaced immediately after each pulse, using a flat mirror set on a two-axis computer-controlled device powered by two servomotors. The displacement followed a 4 × 4 zigzag path such that the same spot was stimulated only once within each train. The distance between two consecutive stimuli was ∼5 mm. The stimuli were applied using two different energies. The high energy activated both Aδ- and C-nociceptors (stimulus Aδ+C), whereas the low energy activated C-nociceptors selectively (stimulus C).

High-energy laser stimuli were used to concomitantly activate Aδ- and C-fiber skin nociceptors (“Aδ+C” stimulus), whereas low-energy laser stimuli were used to activate C-fiber free nerve endings selectively (“C” stimulus). Indeed, because the thermal activation threshold of C-fiber afferents is consistently lower than the thermal activation threshold of Aδ-fiber afferents (difference, 2.3–3°C) (Plaghki et al., 2010), reducing the energy density of the laser stimulus constitutes one of the previously validated methods to activate C-nociceptors selectively (for review, see Plaghki and Mouraux, 2002, 2005; Plaghki, 2007), and this approach has been already used successfully in several previous studies (Treede et al., 1995; Towell et al., 1996; Magerl et al., 1999; Agostino et al., 2000; Tran et al., 2002; Cruccu et al., 2003; Iannetti et al., 2003; Mouraux et al., 2003; Qiu et al., 2006; Mouraux and Plaghki, 2007).

Before the experimental session, for each participant and for each stimulation site, the energies of the Aδ+C and C laser stimuli were defined individually, as follows. Reaction times (RTs) were used as criterion to estimate the thermal detection threshold of the sensations mediated by Aδ- and C-fibers, respectively. Threshold estimates were obtained by the means of two interleaved staircases, using a validated method described by Plaghki (2007), as well as by Mouraux and Plaghki (2007). The first staircase converged toward the threshold (50% detection rate) for detecting any sensation. Because (1) the thermal activation threshold of C-fibers is lower than that of myelinated Aδ-fibers and (2) the conduction velocity of unmyelinated C-fibers is much lower than that of myelinated Aδ-fibers (Bromm and Treede, 1984; Bjerring and Arendt-Nielsen, 1988; Mouraux et al., 2003; Nahra and Plaghki, 2003; Mouraux and Plaghki, 2007), the threshold estimated using this first staircase can be assumed to reflect the detection threshold of C-fiber mediated sensations (i.e., “second pain”). The second staircase converged toward the threshold (50% detection rate) for detecting the stimulus with a RT <650 ms. Taking into account the peripheral conduction distance, such RT latencies are only compatible with the greater conduction velocity of myelinated Aδ-fibers. Hence, the threshold estimated using this second staircase may be assumed to reflect the detection threshold of Aδ-fiber mediated sensations (i.e., “first pain”). For each of the two staircases, the energy of the first stimulus was 500 mJ, and the initial step size was 50 mJ. After the first staircase reversal, the step size was reduced to 25 mJ.

The energy of the Aδ+C stimulus was then set to ∼50 mJ above the estimated threshold of Aδ-nociceptors, whereas the energy of the C stimulus was set to ∼50 mJ above the estimated threshold of C-nociceptors. Importantly, for each participant and stimulation site, it was ensured that the energy of the Aδ+C stimulus elicited only detections with RT <650 ms, and that the energy of the C stimulus elicited only detections with RT >650 ms, by recording reaction times to three to five additional single laser pulses.

Calibration of the stimulus energy was performed at the end of each experiment using an optical energy meter (13PEM001; Melles Griot). Measurement of the baseline skin temperature at target site was also performed, at the beginning and end of each experiment using an infrared thermometer (Tempet; Somedic).

Experimental design

Stimuli were applied in blocks at one of four stimulation sites (left hand dorsum, right hand dorsum, left foot dorsum, right foot dorsum), using one of two different energies (referred to as Aδ+C and C). This resulted in a total of eight stimulation blocks (4 stimulation sites × 2 stimulation energies). Each block consisted of 10 trains of laser pulses. The order of the blocks was pseudorandomized across participants, such that the same site was never stimulated twice in a row. The entire procedure lasted ∼1 h.

Electrophysiological measures

The EEG was recorded using 64 Ag–AgCl electrodes placed on the scalp according to the International 10/10 system (Waveguard64 cap; Cephalon), using a common average reference. Ground electrode was positioned on the forehead. Ocular movements and eyeblinks were recorded using two additional surface electrodes placed at the upper-left and lower-right sides of the left eye. Signals were amplified and digitized using a sampling rate of 1000 Hz (64-channel high-speed amplifier; Advanced Neuro Technology).

Data analysis

All EEG processing steps were performed using Analyzer 1.05 (Brain Products), Letswave (http://nocions.webnode.com/letswave) (Mouraux and Iannetti, 2008), Matlab (The MathWorks), and EEGLAB (http://sccn.ucsd.edu).

Continuous EEG recordings were filtered using a 1 Hz high-pass Butterworth zero-phase filter, to remove slow drifts in the recorded signals. Nonoverlapping EEG epochs were obtained by segmenting the recordings from 0 to 2000 ms (stimulation epochs) and from −2000 to 0 ms (stimulation-free epochs serving as control) relative to the onset of each stimulation train, thus yielding a total of 10 stimulation epochs and 10 stimulation-free epochs per stimulation block. Epochs containing artifacts exceeding 250 μV were rejected from additional analyses. Based on this criterion, the rejection rate of epochs was 6 ± 5% (group-level mean ± SD).

For each subject, stimulation site, and stimulation energy, artifact-free EEG epochs were averaged such as to attenuate the contribution of activities non phase-locked to the stimulation train. The obtained average waveforms were then transformed in the frequency domain using a discrete Fourier transform (FFTW) (Frigo and Johnson, 1998), yielding a power spectrum (in square microvolts) ranging from 0 to 500 Hz with a frequency resolution of 0.25 Hz (Bach and Meigen, 1999).

Within the obtained power spectrums, the power at the frequency of 7 Hz (i.e., the frequency of stimulation) was measured. That measure of signal power may be expected to correspond to the sum of (1) the stimulus-evoked steady-state response and (2) unrelated residual background “noise” attributable, for example, to spontaneous EEG activity, muscle activity, and eye movements. Therefore, to obtain valid estimates of the magnitude of the recorded SS-EPs, the contribution of this residual noise was removed by subtracting, at each electrode, the average power measured at neighboring frequencies (i.e., the four frequency bins ranging from 6.0 to 6.5 Hz and from 7.5 to 8 Hz) (Srinivasan et al., 1999). For each subject, stimulation site, and stimulation energy, it was then examined whether the magnitude of the subtracted signal power was significantly greater than zero, using a Wilcoxon signed rank test. Indeed, in the absence of a steady-state response, the average of the subtracted signal power may be expected to tend toward zero. Significance level was set at p < 0.05.

To estimate the latency, scalp topography, and sources of the elicited nociceptive SS-EPs, additional average waveforms were computed as follows. First, continuous EEG recordings were filtered using a narrow 6–8 Hz bandpass Butterworth zero-phase filter, such as to filter out signal changes unrelated to the steady-state response. Nonoverlapping EEG epochs were then obtained by segmenting the recordings from 0 to 140 ms relative to the onset of each of the 16 pulses of the train. For each stimulation block, this resulted in a total of 160 epochs (10 trains × 16 pulses). EEG epochs were then averaged across trials. Within these bandpass-filtered average waveforms, the SS-EP appeared, at electrode Cz, as a negative peak followed by a positive peak.

Analysis of response latency.

To examine the effect of peripheral conduction distance and peripheral conduction velocity of the afferents mediating nociceptive SS-EPs, the latency of the SS-EPs elicited by lower and upper limb stimulation (left hand vs left foot; right hand vs right foot) were estimated by measuring the latency of the negative peak after stimulation of the left hand, right hand, left foot, and right foot, measured at electrode Cz. Obtained latencies were compared using a two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with “stimulation side” (left or right) and “limb extremity” (hand or foot) as experimental factors. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were performed using paired-sample t tests. Significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Scalp topography and source analysis.

Grand-average topographical maps were computed by spherical interpolation, using the amplitude of the negative peak of the steady-state response. Source locations were modeled by fitting a single equivalent dipole to the obtained topographical maps, using an algorithm based on a nonlinear optimization technique, and a standardized boundary element head model (dipfit2) (Woody, 1967; Fuchs et al., 2002). Dipole locations outside the head, and dipole models with a residual variance exceeding 40% were excluded.

Control experiment

Innocuous somatosensory SS-EPs were recorded in three healthy volunteers (two males and one female; all right-handed; aged 24–32 years). Such as in the main experiment, subjects were at first familiarized with the experimental setup and exposed to a small number of test stimuli (three to five stimuli at each stimulus location).

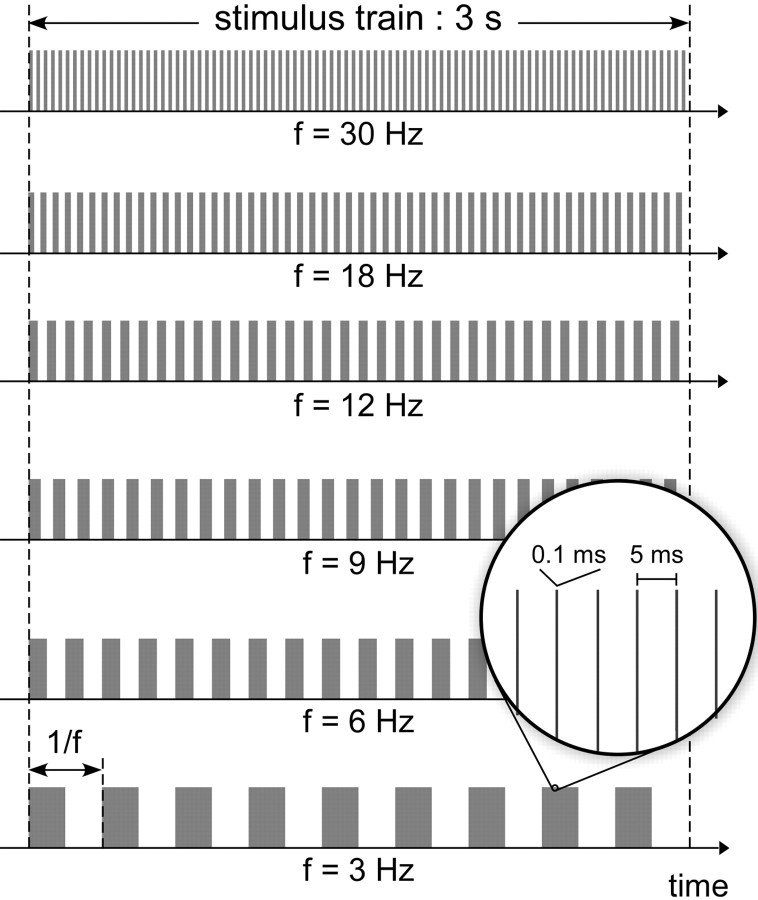

Steady-state innocuous somatosensory stimuli were delivered in 3-s-long trains of rapidly repeated low-intensity transcutaneous electrical pulses, applied to the left or right nervus radialis superficialis at the level of the wrist (“Aβ” stimulus) (Fig. 2). Intertrain interval was 5 s. Each individual electrical pulse consisted of a constant-current square wave lasting 0.1 ms, separated by a 5 ms interpulse interval. The intensity of the electrical pulse was individually adjusted, such that a single pulse elicited a mild nonpainful paraesthesia in the skin area innervated by the stimulated nerve (1.7 ± 0.4 mA). The trains of stimulation were modulated by a repeating boxcar function, such that, within each train, periods of stimulation were alternated with periods without stimulation of equal duration, with a periodicity of 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 30 Hz. A total of 144 trains were delivered at each stimulation site (24 trains × 6 frequencies of stimulation, delivered in pseudorandom order, such that the same site was never stimulated twice in a row). The entire acquisition lasted ∼1 h.

Figure 2.

Rapid periodic stimulation of non-nociceptive Aβ-fibers. Innocuous transcutaneous electrical pulses were delivered in 3-s-long trains of rapidly repeated low-intensity transcutaneous electrical pulses, applied to the left and right superficial radial nerve. Each individual pulse consisted of a constant-current square wave lasting 0.1 ms, separated by a 5 ms interpulse interval. The trains of stimulation were modulated by a repeating boxcar function, such that within each train, periods of stimulation were alternated with periods without stimulation of equal duration, with a periodicity of 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 30 Hz.

Electrophysiological measures and analyses were performed using the same procedures as described above for the main experiment.

Results

Thermal activation thresholds

When a single laser stimulus was applied, the thermal activation threshold of C-nociceptors was 5.8 ± 1.0 mJ/mm2 at the left hand, 6.2 ± 0.9 mJ/mm2 at the right hand, 6.1 ± 1.1 mJ/mm2 at the left foot, and 6.3 ± 0.8 mJ/mm2 at the right foot (group-level average ± SD). The thermal activation threshold of Aδ-nociceptors was 9.8 ± 0.9 mJ/mm2 at the left hand, 8.6 ± 1.4 mJ/mm2 at the right hand, 10.2 ± 1.5 mJ/mm2 at the left foot, and 9.3 ± 1.3 mJ/mm2 at the right foot.

Whatever the stimulation site, applying a single Aδ+C laser pulse elicited a clear pricking sensation that was detected with a reaction time compatible with the conduction velocity of Aδ-fibers (left hand, 353 ± 55 ms; right hand, 336 ± 88 ms; left foot, 354 ± 59 ms; right foot, 360 ± 81 ms), whereas applying a single C laser pulse elicited a long-lasting warm sensation that was detected with a reaction time compatible with the conduction velocity of C-fibers (left hand, 954 ± 115 ms; right hand, 1032 ± 126 ms; left foot, 1283 ± 280 ms; right foot, 1354 ± 164 ms).

Trains of Aδ+C stimuli elicited a continuous painful pricking and burning sensation (similar to the sensation elicited by the contact with stinging nettles), whereas trains of C stimuli elicited a continuous warm and sometimes burning sensation. For both the Aδ+C and the C stimulus, subjects did not perceive the individual stimuli within the train, nor did they perceive a movement of the stimulus across the skin.

At each stimulation site, the skin temperatures measured at the beginning (left hand, 32.0 ± 1.3°C; right hand, 31.8 ± 1.1°C; left foot, 31.5 ± 0.9°C; right foot, 31.3 ± 1.1°C) and end (left hand, 31.8 ± 0.9°C; right hand, 31.4 ± 1.5°C; left foot, 31.5 ± 1.1°C; right foot, 31.6 ± 0.7°C) of the experiment were not significantly different.

SS-EPs elicited by the coactivation of Aδ- and C-nociceptors

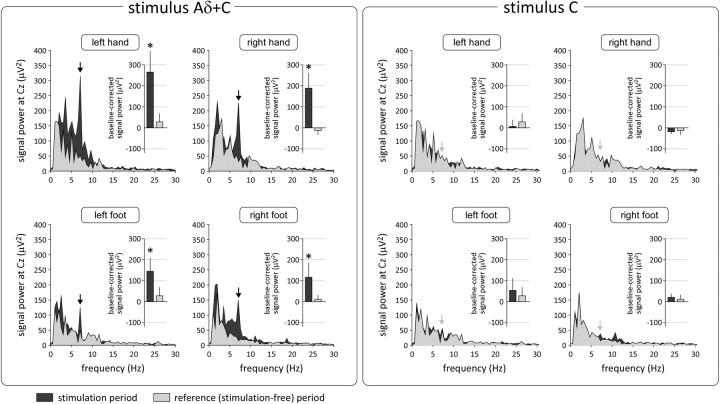

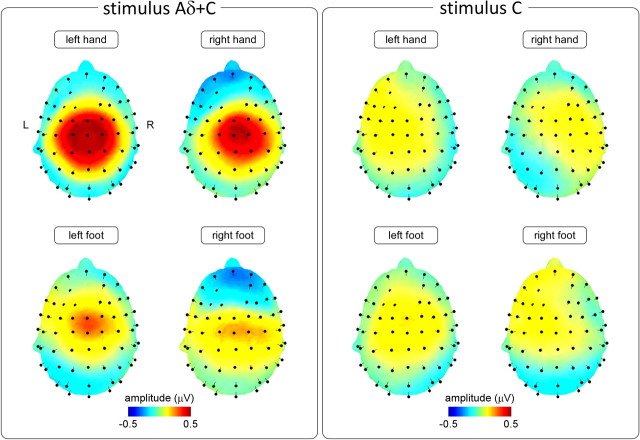

For all stimulus locations, the Aδ+C stimulus elicited a marked increase of signal power centered at 7 Hz (i.e., at the frequency of stimulation) (Fig. 3, left panel). No significant increase of signal power was observed at the harmonics of this fundamental frequency. Independently of the stimulation site, the scalp topography of the elicited response was maximal at the vertex (electrode Cz) and was symmetrically distributed over both hemispheres (Fig. 4, left panel).

Figure 3.

Group-level average of the frequency spectrum of the EEG signals recorded at electrode Cz during the 7 Hz periodic stimulation of Aδ- and C-nociceptors (Aδ+C stimulus, left panel), and during the 7 Hz periodic stimulation of C-nociceptors (C stimulus, right panel). The EEG spectra obtained during stimulation are shown in dark gray, whereas the spectra obtained during the reference stimulation-free period are shown in light gray (x-axis, frequency in Hz; y-axis, signal power in square microvolts). The bar graphs represent the average power of the EEG signal at 7 Hz (group-level average ± SD) after subtraction of the surrounding background noise (see Materials and Methods). Note that, for all stimulus locations, the Aδ+C stimulus elicited a significant SS-EP (marked by the vertical black arrows; *p < 0.05). In contrast, the C stimulus did not elicit a significant increase of power in the EEG signal.

Figure 4.

Scalp topography of the nociceptive SS-EPs elicited by 7 Hz periodic stimulation of Aδ- and C-nociceptors (Aδ+C stimulus, left panel), and during the 7 Hz periodic stimulation of C-nociceptors (C stimulus, right panel). The scalp maps represent the topographical distribution of the stimulus-induced increase in EEG signal power at the frequency of stimulation, after stimulation of the left and right hand and foot dorsum (group-level average) (see Materials and Methods). Note that, for all stimulus locations, the Aδ+C stimulus elicited a consistent SS-EP whose scalp topography was maximal at the vertex (electrode Cz). Also note that the C stimulus did not elicit a consistent SS-EP.

After subtraction of the surrounding frequency bins to account for residual background noise, the magnitude of the steady-state response was, at electrode Cz, 264 ± 105 μV2 after stimulation of the left hand, 188 ± 78 μV2 after stimulation of the right hand, 141 ± 65 μV2 after stimulation of the left foot, and 115 ± 72 μV2 after stimulation of the right foot (Fig. 3, left panel). At all stimulus locations, this increase of signal power was significantly greater than zero (left hand, p = 0.03; right hand, p = 0.01; left foot, p = 0.04; right foot, p = 0.02). No corresponding increase of signal power was observed within the stimulation-free EEG epochs serving as controls (left hand: 28 ± 41 μV2, p = 0.74; right hand: −13 ± 21 μV2, p = 0.84; left foot: 19 ± 13 μV2, p = 0.11; right foot: −15 ± 6 μV2, p = 0.38).

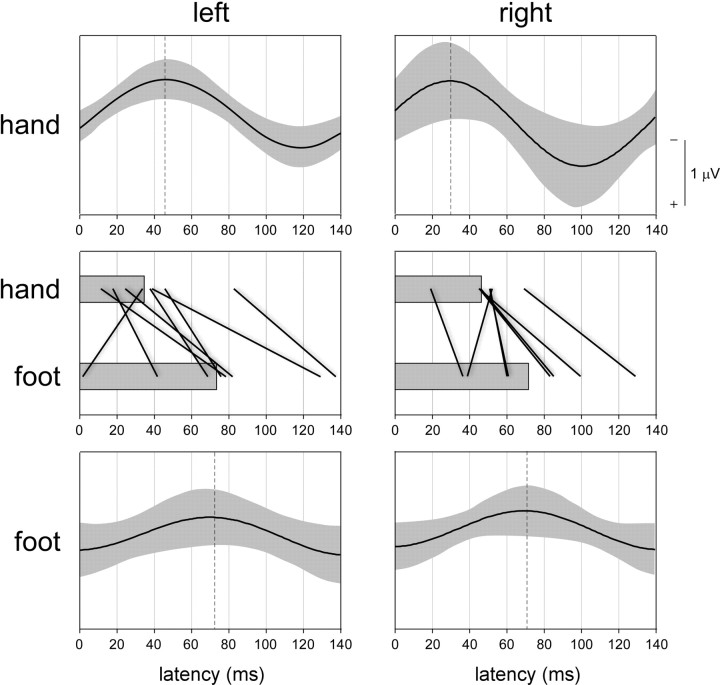

The latency of the Aδ+C SS-EPs elicited by stimulation of the lower limb extremities was significantly different from the latency of the SS-EPs elicited by stimulation of the upper limb extremities (Fig. 5). Indeed, the repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of the factor limb extremity (F = 14.8, p = 0.006; left foot − left hand: Δt = 41 ± 13 ms, p = 0.02; right foot − right hand: Δt = 27 ± 9 ms, p = 0.02). In contrast, there was no significant main effect of the factor stimulation side (F = 0.2, p = 0.67; right hand − left hand: Δt = 11 ± 7 ms; right foot − left foot: Δt = −2 ± 17 ms), and no significant interaction between the two factors (F = 1.0; p = 0.35). This observation suggests that the SS-EPs elicited by stimulation of the lower limb extremities was slightly but significantly delayed compared with the SS-EPs elicited by stimulation of the upper limb extremities.

Figure 5.

The top and bottom panels show the group-level average (±SD; shown in light gray) of the time course of the SS-EPs induced by periodic 7 Hz nociceptive stimulation of Aδ- and C-nociceptors, applied to the left and right hand dorsum (top graphs) and the left and right foot dorsum (bottom graphs). Electrode Cz versus average reference, x-axis: time in milliseconds relative to stimulus onset, y-axis: amplitude in microvolts. The middle panel shows the estimated latency of the nociceptive SS-EPs obtained at each of the four stimulation sites (for details, see Materials and Methods). Single-subject latencies are represented as connecting straight lines, whereas group-level averages are shown using horizontal bars. Note that, regardless of the stimulated side, the time courses of the lower-limb SS-EPs are consistently delayed compared with the time courses of the upper-limb SS-EPs.

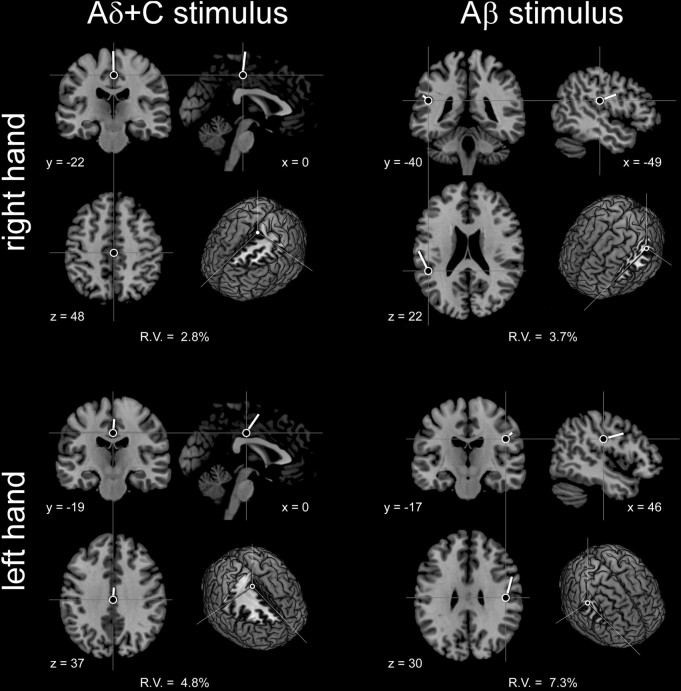

Source analysis of the SS-EPs elicited by Aδ+C stimuli applied to either the left hand or the right hand could be modeled with a very low residual variance (left hand, 4.8%; right hand, 2.8%) using a single radial dipole located in anterior midline brain structures (left hand: x = 0, y = −19, z = 37; right hand: x = 0, y = −22, z = 48; Montreal Neurological Institute coordinates), possibly within the posterior part of the anterior cingulate cortex (Fig. 6, left graphs). SS-EPs elicited by Aδ+C stimuli applied to the left or right foot were also best modeled by a single equivalent dipole located in midline brain structures (left foot: x = 13, y = 50, z = 48; right foot: x = 6, y = 9, z = 39), but the residual variance of the obtained models was relatively more important (left foot, 23.2%; right foot, 14.7%).

Figure 6.

Source analysis of the nociceptive SS-EPs elicited by 7 Hz thermal nociceptive stimulation of Aδ- and C-nociceptors (left graphs), and the SS-EPs elicited by 6 Hz non-nociceptive stimulation of Aβ-fibers (right graphs). Results obtained after stimulation of the left and right hands are shown in the top and bottom graphs, respectively. Source locations were modeled by fitting a single equivalent dipole to the group-level topographical maps of the corresponding nociceptive and non-nociceptive SS-EPs (see Materials and Methods). Note that, whereas the nociceptive SS-EPs were best modeled as a single radial dipole consistently located near the midline, the non-nociceptive SS-EPs were best modeled as a single tangential dipole, lateralized in the parietal lobe contralateral to the stimulated side.

SS-EPs elicited by the selective activation of C-nociceptors

Although the C stimulus applied at a frequency of 7 Hz generated a clear percept in all participants and at all stimulation sites, it did not elicit a significant increase of EEG signal power (Figs. 3, 4, right panel). Indeed, at electrode Cz (but also at other electrodes), the magnitude of the remaining EEG power was not significantly different from zero after subtraction of the surrounding background noise (left hand: −7 ± 36 μV2, p = 0.94; right hand: −18 ± 12 μV2, p = 0.31; left foot: 54 ± 59 μV2, p = 0.64; right foot: 21 ± 19 μV2, p = 0.19). In other words, the C stimulus did not appear to elicit a measurable SS-EP.

SS-EPs elicited by the activation of Aβ-fibers

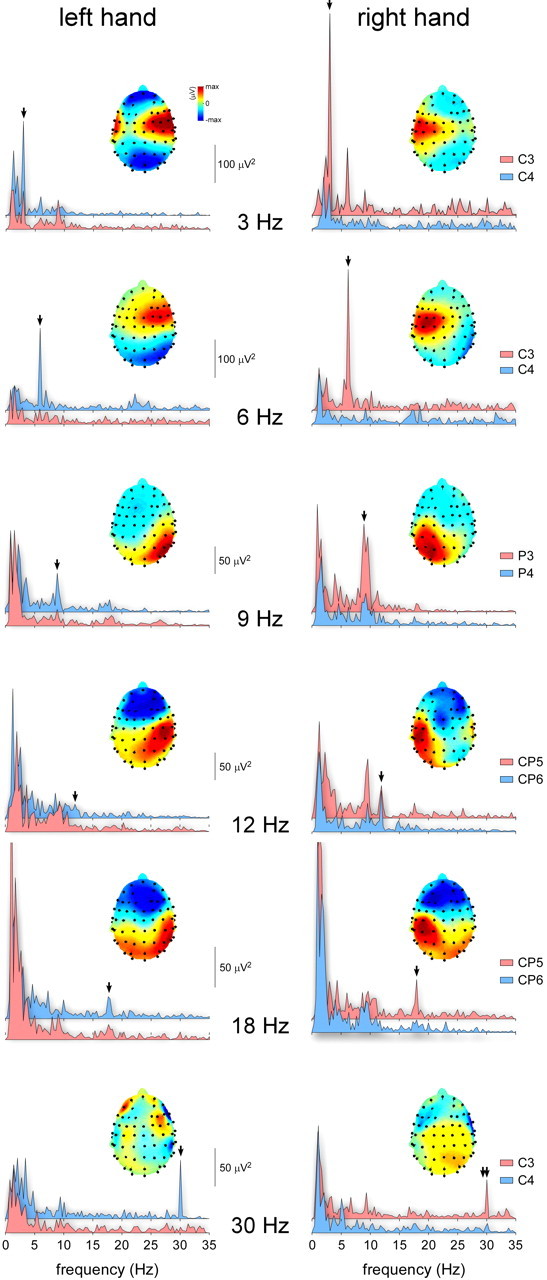

For all stimulus locations (left and right hand), and for all stimulation frequencies (3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 30 Hz), the periodic electrical activation of innocuous Aβ-fibers produced a strong but nonpainful vibrotactile sensation in the sensory territory of the stimulated nerve, and elicited a marked increase of EEG signal power centered at the frequency corresponding to the frequency of stimulation (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Group-level average of the non-nociceptive somatosensory SS-EPs elicited by 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 30 Hz periodic electrical stimulation of Aβ-fibers. Left panel, SS-EPs elicited by stimulation of the left hand. Right panel, SS-EPs elicited by stimulation of the right hand. The spectra represent the EEG signal power (x-axis: frequency in hertz; y-axis, signal power in square microvolts) obtained at two symmetrical parietal electrodes (light red: electrode positioned over the left hemisphere; light blue: electrode positioned over the right hemisphere). The scalp maps represent the topographical distribution of the SS-EPs elicited using the different frequencies of stimulation. Note that, at all frequencies, the stimulus elicited a consistent SS-EP whose scalp topography was markedly lateralized over the hemisphere contralateral to the stimulated side.

The scalp topography of the elicited SS-EPs was noticeably asymmetrical and dependent on the stimulated side. Indeed, at most frequencies of stimulation, the scalp topography was clearly maximal over the posterior parietal region contralateral to the stimulated side (Fig. 7).

Whatever the frequency of stimulation, the sources of the SS-EPs elicited by Aβ stimuli applied to the left hand could be modeled effectively using a single equivalent dipole located in the right parietal lobe, whereas the sources of the SS-EPs elicited by Aβ stimuli applied to the right hand could be modeled effectively using a single equivalent dipole located in the left parietal lobe. In particular, at the frequency of stimulation closest to the frequency of stimulation used to elicit nociceptive SS-EPs (i.e., 6 Hz), the SS-EPs elicited by Aβ stimuli were modeled as a single tangential dipole located in the parietal lobe contralateral to the stimulated side, near the hand area of the primary somatosensory cortex (left hand: x = 46, y = −17, z = 30; right hand: x = −49, y = −40, z = 22), with a very low residual variance (left hand, 7.3%; right hand, 3.7%) (Fig. 6, right graphs).

Discussion

The present study shows, for the first time, that it is possible to record nociceptive steady-state evoked potentials in response to the rapid periodic thermal activation of cutaneous nociceptors in humans. Indeed, at 7 Hz, the periodic coactivation of Aδ- and C-nociceptors elicited a clear SS-EP, which was maximal at the vertex and symmetrically distributed over both hemispheres. This scalp topography was best modeled as a radial source originating from the posterior part of the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). It contrasted strongly with the lateralized scalp topography of the SS-EPs elicited by the activation of non-nociceptive Aβ-fibers, which displayed a clear maximum over the parietal region contralateral to the stimulated side, and was best modeled as a tangential source originating from the contralateral primary somatosensory cortex (S1). Hence, because the pattern of cortical activity elicited by nociceptive stimulation was markedly different from the pattern elicited by non-nociceptive somatosensory stimulation, we hypothesize that nociceptive SS-EPs reflect the activity of a cortical network preferentially involved in the processing of nociceptive input, distinct from the somatotopically organized cortical network underlying tactile SS-EPs.

Functional significance of SS-EPs

SS-EPs are often considered to be the consequence of a stimulus-driven entrainment of neurons responding to the eliciting periodic sensory stimulus (Herrmann, 2001; Muller et al., 2001; Vialatte et al., 2010). Supporting this interpretation, it has been shown that the magnitude of the SS-EP elicited by a flickering visual stimulus is markedly greater for particular frequencies of stimulation than for adjacent frequencies of stimulation, indicating a preference of the underlying neuronal oscillators for given frequencies of stimulation and its harmonics (Herrmann, 2001). Similar findings have been made concerning the SS-EPs elicited by auditory and somatosensory stimulation (Kelly et al., 1997; Kelly and Folger, 1999; Tobimatsu et al., 1999; Plourde, 2006). The preferred response frequencies of SS-EPs could be related to the temporal characteristics of the axonal connections constituting the resonating network of interconnected neurons (Herrmann, 2001).

What is the functional significance of the neural activity underlying these responses? SS-EPs elicited by visual, auditory, and vibrotactile stimuli have been shown to originate mainly from the corresponding primary sensory cortices (Snyder, 1992; Pantev et al., 1996; Kelly et al., 1997; Kelly and Folger, 1999; Srinivasan et al., 2006; Giabbiconi et al., 2007). Hence, it may be hypothesized that nociceptive SS-EPs reflect the entrainment of neurons that are at least partly involved in early, modality-specific, nociceptive processing.

SS-EPs related to the coactivation of Aδ- and C-nociceptors

Although thermal laser stimuli applied to the skin activate Aδ- and C-nociceptors selectively (Treede et al., 1995), the morphology and scalp topography of LEPs are strikingly similar to the morphology and scalp topography of the late “vertex potentials” that can be elicited by stimuli belonging to any other sensory modality (Kunde and Treede, 1993; Mouraux and Iannetti, 2009). For this reason, some investigators have proposed that nociceptive ERPs reflect cortical activity that, for the greater part, is unspecific for nociception (Chapman et al., 1981; Stowell, 1984a; Andersson and Rydenhag, 1985; Mouraux and Iannetti, 2009), and related mainly to attentional orientation triggered by the transient nociceptive stimulus (Lorenz and Garcia-Larrea, 2003; Iannetti et al., 2008; Legrain et al., 2011). In contrast, when a 7 Hz periodic train of nociceptive stimuli is applied such as to elicit an SS-EP, the different stimuli of the train are not perceived as distinct events (Lee et al., 2009). Hence, compared with transient nociceptive ERPs, nociceptive SS-EPs are likely to be less imprinted by stimulus-driven attentional processes, and are thus more likely to reflect activity more specifically related to nociception.

Another important characteristic of SS-EPs is that they usually exhibit a high signal-to-noise ratio (Regan, 1966). Although the power of the SS-EP is concentrated almost exclusively at the frequency of the stimulus (and its harmonics), the power of the ongoing EEG, as well as that of noncerebral artifacts (e.g., eye blinks, muscular activity), are spread over a wide range of frequencies. Therefore, the contribution of non-stimulus-related signals to the power measured at the specific frequency of the SS-EP is comparatively very small. Furthermore, the entrainment induced by the periodic stimulation could enhance the magnitude of the recorded responses. For these reasons, nociceptive SS-EPs could reflect stimulus-triggered electrocortical activity that is not captured consistently by conventional transient nociceptive ERPs and, hence, may constitute a unique means to isolate and tag the activity of neurons responding to nociceptive stimulation.

In agreement with this view, the scalp topography of the nociceptive SS-EPs elicited by the coactivation of Aδ- and C-nociceptors was markedly different from the scalp topography of the tactile SS-EPs elicited by the activation of non-nociceptive Aβ-fibers, thus indicating that nociceptive and non-nociceptive somatosensory SS-EPs reflect activity originating from spatially distinct cortical networks.

As in previous studies, we show that innocuous vibrotactile stimulation of the lemniscal somatosensory pathway elicits an SS-EP whose scalp topography is maximal over the parietal region contralateral to the stimulated side (Snyder, 1992; Tobimatsu et al., 1999; Muller et al., 2001; Giabbiconi et al., 2004, 2007) and whose sources may be modeled as activity originating from the contralateral S1 (Snyder, 1992; Giabbiconi et al., 2007). In support of this interpretation, single-cell recordings performed in animals have shown that rapidly adapting afferent units encoding vibrotactile somatosensory input have strong projections to areas 3b and area 1 of the contralateral S1 cortex (Mountcastle et al., 1990).

Most interestingly, we show that nociceptive somatosensory stimulation does not elicit a similarly lateralized SS-EP, thus indicating that the contralateral S1 cortex does not contribute in a similar way to the nociceptive SS-EP. One possible interpretation of this finding is that S1 is less consistently activated by the periodic stimulation of Aδ- and C-nociceptors. Another interpretation is that, whereas innocuous vibrotactile input projects predominantly to area 3b and area 1 of S1, nociceptive input may project predominantly to a different area of S1, whose activation may not translate into a measurable SS-EP. In support of this second interpretation, a recent study has shown that, whereas area 3b and area 1 contain very few nociceptive neurons, area 3a is densely populated by neurons responding vigorously to nociceptive stimulation (Whitsel et al., 2009). However, one should then explain why stimulus-triggered neuronal activity originating from a different area of S1 does not generate a scalp SS-EP. This could be attributable to the spatial location and/or orientation of these different neurons, or to the temporal characteristics of their response to repeated nociceptive stimulation, which may be not sufficiently phasic to generate, at 7 Hz, a measurable deflection in the EEG.

The scalp topographies and source analyses performed in the present study suggest that the identified nociceptive SS-EPs reflect activity originating mainly from anterior midline brain structures, possibly within the posterior part of the ACC. Evidently, given the low spatial resolution of EEG, especially when considering deep midline and/or bilateral cortical generators, a possible contribution from other brain structures such as the left and right operculo-insular cortices cannot be excluded. Nevertheless, the cortical activity giving rise to nociceptive SS-EPs does not appear to contribute significantly to the non-nociceptive somatosensory SS-EP. Therefore, we hypothesize that nociceptive SS-EPs reflect the activation of a cortical network preferentially involved in the processing of nociceptive input. Interestingly, this proposal is supported by recent experimental evidence obtained using anterograde neuronal tracing in monkeys, showing that one of the main cortical targets of the spinothalamic system is the cingulate cortex, in particular, motor areas located on the medial wall of both cerebral hemispheres (Dum et al., 2009).

SS-EPs related to the selective activation of C-nociceptors

The selective activation of C-nociceptors did not elicit a consistent SS-EP. This indicates that the cortical network underlying the nociceptive SS-EPs elicited by the coactivation of Aδ- and C-nociceptors is not similarly engaged by stimuli activating C-nociceptors selectively. Hence, we postulate that the SS-EPs elicited by the Aδ+C stimulus were primarily related to the periodic activation of Aδ-nociceptors.

It is important to recall that the magnitude of the SS-EP response is not only determined by the average amplitude of the response but also by the consistency of its phase over the large number of repeated cycles. Therefore, differences in the response properties of Aδ- and C-nociceptors could explain why thermal nociceptive stimuli applied at a frequency of 7 Hz are able to elicit a rhythmic nociceptive afferent volley in Aδ-fibers (leading to the appearance of an SS-EP), but not in C-fibers. Furthermore, assuming that the response properties of C-nociceptors would allow the generation of a periodic nociceptive afferent volley at the distal end of peripheral nociceptors, this periodicity could be blurred out by the important variability in C-fiber nerve conduction velocity (Torebjörk and Hallin, 1974), or by the response properties of higher-order neurons relaying C-fiber input to the cortex. In other words, at present, it is not known whether the periodic thermal activation of C-nociceptors generates, at 7 Hz, a truly periodic C-fiber input at the level of the CNS, nor is it known whether C-fiber input may elicit a measurable SS-EP using different stimulation frequencies.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Pain Research European Federation of Chapters of the International Association for the Study of Pain–Grünenthal Grant 2008, the International Association for the Study of Pain Early Career Research Grant, and a Marie Curie European Reintegration Grant (A.M.). S.N. is a fellow of the Fund for Scientific Research of the French-speaking community of Belgium (Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique–Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique). V.L. is a fellow of the Research Foundation Flanders, Belgium (Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek). G.D.I. is a University Research Fellow of The Royal Society and acknowledges the support of the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council.

References

- Agostino R, Cruccu G, Iannetti G, Romaniello A, Truini A, Manfredi M. Topographical distribution of pinprick and warmth thresholds to CO2 laser stimulation on the human skin. Neurosci Lett. 2000;285:115–118. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson SA, Rydenhag B. Cortical nociceptive systems. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1985;308:347–359. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1985.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach M, Meigen T. Do's and don'ts in Fourier analysis of steady-state potentials. Doc Ophthalmol. 1999;99:69–82. doi: 10.1023/a:1002648202420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgärtner U, Tiede W, Treede RD, Craig AD. Laser-evoked potentials are graded and somatotopically organized anteroposteriorly in the operculoinsular cortex of anesthetized monkeys. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96:2802–2808. doi: 10.1152/jn.00512.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjerring P, Arendt-Nielsen L. Argon laser induced single cortical responses: a new method to quantify pre-pain and pain perceptions. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1988;51:43–49. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.51.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromm B, Treede RD. Nerve fibre discharges, cerebral potentials and sensations induced by CO2 laser stimulation. Hum Neurobiol. 1984;3:33–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushnell MC, Apkarian AV. Representation of pain in the brain. In: McMahon S, Koltzenburg M, editors. Textbook of pain. Ed 5. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2005. pp. 267–289. [Google Scholar]

- Carmon A, Mor J, Goldberg J. Evoked cerebral responses to noxious thermal stimuli in humans. Exp Brain Res. 1976;25:103–107. doi: 10.1007/BF00237330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman CR, Colpitts YH, Mayeno JK, Gagliardi GJ. Rate of stimulus repetition changes evoked potential amplitude: dental and auditory modalities compared. Exp Brain Res. 1981;43:246–252. doi: 10.1007/BF00238365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruccu G, Pennisi E, Truini A, Iannetti GD, Romaniello A, Le Pera D, De Armas L, Leandri M, Manfredi M, Valeriani M. Unmyelinated trigeminal pathways as assessed by laser stimuli in humans. Brain. 2003;126:2246–2256. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dum RP, Levinthal DJ, Strick PL. The spinothalamic system targets motor and sensory areas in the cerebral cortex of monkeys. J Neurosci. 2009;29:14223–14235. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3398-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frigo M, Johnson SG. FFTW: an adaptive software architecture for the FFT. Proceedings of the 1998 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing; Seattle: IEEE; 1998. pp. 1381–1383. [Google Scholar]

- Frot M, Mauguière F. Dual representation of pain in the operculo-insular cortex in humans. Brain. 2003;126:438–450. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs M, Kastner J, Wagner M, Hawes S, Ebersole JS. A standardized boundary element method volume conductor model. Clin Neurophysiol. 2002;113:702–712. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(02)00030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Larrea L, Frot M, Valeriani M. Brain generators of laser-evoked potentials: from dipoles to functional significance. Neurophysiol Clin. 2003;33:279–292. doi: 10.1016/j.neucli.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giabbiconi CM, Dancer C, Zopf R, Gruber T, Müller MM. Selective spatial attention to left or right hand flutter sensation modulates the steady-state somatosensory evoked potential. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res. 2004;20:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giabbiconi CM, Trujillo-Barreto NJ, Gruber T, Müller MM. Sustained spatial attention to vibration is mediated in primary somatosensory cortex. Neuroimage. 2007;35:255–262. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann CS. Human EEG responses to 1–100 Hz flicker: resonance phenomena in visual cortex and their potential correlation to cognitive phenomena. Exp Brain Res. 2001;137:346–353. doi: 10.1007/s002210100682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannetti GD, Mouraux A. From the neuromatrix to the pain matrix (and back) Exp Brain Res. 2010;205:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00221-010-2340-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannetti GD, Truini A, Romaniello A, Galeotti F, Rizzo C, Manfredi M, Cruccu G. Evidence of a specific spinal pathway for the sense of warmth in humans. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:562–570. doi: 10.1152/jn.00393.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannetti GD, Hughes NP, Lee MC, Mouraux A. Determinants of laser-evoked EEG responses: pain perception or stimulus saliency? J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:815–828. doi: 10.1152/jn.00097.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakigi R, Inui K, Tamura Y. Electrophysiological studies on human pain perception. Clin Neurophysiol. 2005;116:743–763. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2004.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly EF, Folger SE. EEG evidence of stimulus-directed response dynamics in human somatosensory cortex. Brain Res. 1999;815:326–336. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01087-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly EF, Trulsson M, Folger SE. Periodic microstimulation of single mechanoreceptive afferents produces frequency-following responses in human EEG. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:137–144. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunde V, Treede RD. Topography of middle-latency somatosensory evoked potentials following painful laser stimuli and non-painful electrical stimuli. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1993;88:280–289. doi: 10.1016/0168-5597(93)90052-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MC, Mouraux A, Iannetti GD. Characterizing the cortical activity through which pain emerges from nociception. J Neurosci. 2009;29:7909–7916. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0014-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legrain V, Iannetti GD, Plaghki L, Mouraux A. The pain matrix reloaded. A salience detection system. Prog Neurobiol. 2011;93:111–124. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz J, Garcia-Larrea L. Contribution of attentional and cognitive factors to laser evoked brain potentials. Neurophysiol Clin. 2003;33:293–301. doi: 10.1016/j.neucli.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magerl W, Ali Z, Ellrich J, Meyer RA, Treede RD. C- and A delta-fiber components of heat-evoked cerebral potentials in healthy human subjects. Pain. 1999;82:127–137. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mountcastle VB, Steinmetz MA, Romo R. Frequency discrimination in the sense of flutter: psychophysical measurements correlated with postcentral events in behaving monkeys. J Neurosci. 1990;10:3032–3044. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-09-03032.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouraux A, Iannetti GD. Across-trial averaging of event-related EEG responses and beyond. Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;26:1041–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouraux A, Iannetti GD. Nociceptive laser-evoked brain potentials do not reflect nociceptive-specific neural activity. J Neurophysiol. 2009;101:3258–3269. doi: 10.1152/jn.91181.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouraux A, Plaghki L. Cortical interactions and integration of nociceptive and non-nociceptive somatosensory inputs in humans. Neuroscience. 2007;150:72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouraux A, Guérit JM, Plaghki L. Non-phase locked electroencephalogram (EEG) responses to CO2 laser skin stimulations may reflect central interactions between Aδ- and C-fibre afferent volleys. Clin Neurophysiol. 2003;114:710–722. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(03)00027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller GR, Neuper C, Pfurtscheller G. “Resonance-like” frequencies of sensorimotor areas evoked by repetitive tactile stimulation. Biomed Tech (Berl) 2001;46:186–190. doi: 10.1515/bmte.2001.46.7-8.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahra H, Plaghki L. The effects of A-fiber pressure block on perception and neurophysiological correlates of brief non-painful and painful CO2 laser stimuli in humans. Eur J Pain. 2003;7:189–199. doi: 10.1016/S1090-3801(02)00099-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantev C, Roberts LE, Elbert T, Ross B, Wienbruch C. Tonotopic organization of the sources of human auditory steady-state responses. Hear Res. 1996;101:62–74. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(96)00133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyron R, García-Larrea L, Grégoire MC, Costes N, Convers P, Lavenne F, Mauguière F, Michel D, Laurent B. Haemodynamic brain responses to acute pain in humans. Sensory and attentional networks. Brain. 1999;122:1765–1780. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.9.1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaghki L. Pain evaluation, psychophysical methods. In: Schmidt RF, Willis WD, editors. Encyclopedia of pain. Berlin: Springer; 2007. pp. 1659–1664. [Google Scholar]

- Plaghki L, Mouraux A. Brain responses to signals ascending through C-fibers. In: Hirata K, editor. International Congress Series. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2002. pp. 181–192. [Google Scholar]

- Plaghki L, Mouraux A. How do we selectively activate skin nociceptors with a high power infrared laser? Physiology and biophysics of laser stimulation. Neurophysiol Clin. 2003;33:269–277. doi: 10.1016/j.neucli.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaghki L, Mouraux A. EEG and laser stimulation as tools for pain research. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2005;6:58–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaghki L, Delisle D, Godfraind JM. Heterotopic nociceptive conditioning stimuli and mental task modulate differently the perception and physiological correlates of short CO2 laser stimuli. Pain. 1994;57:181–192. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)90222-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaghki L, Decruynaere C, Van Dooren P, Le Bars D. The fine tuning of pain thresholds: a sophisticated double alarm system. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plourde G. Auditory evoked potentials. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2006;20:129–139. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Y, Noguchi Y, Honda M, Nakata H, Tamura Y, Tanaka S, Sadato N, Wang X, Inui K, Kakigi R. Brain processing of the signals ascending through unmyelinated C fibers in humans: an event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16:1289–1295. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan D. Some characteristics of average steady-state and transient responses evoked by modulated light. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1966;20:238–248. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(66)90088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan D. Evoked potentials and evoked magnetic fields in science and medicine. New York: Elsevier; 1989. Human brain electrophysiology. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder AZ. Steady-state vibration evoked potentials: descriptions of technique and characterization of responses. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1992;84:257–268. doi: 10.1016/0168-5597(92)90007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan R, Russell DP, Edelman GM, Tononi G. Increased synchronization of neuromagnetic responses during conscious perception. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5435–5448. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-13-05435.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan R, Bibi FA, Nunez PL. Steady-state visual evoked potentials: distributed local sources and wave-like dynamics are sensitive to flicker frequency. Brain Topogr. 2006;18:167–187. doi: 10.1007/s10548-006-0267-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowell H. Event related brain potentials and human pain: a first objective overview. Int J Psychophysiol. 1984a;1:137–151. doi: 10.1016/0167-8760(84)90034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowell H. Nociceptive evoked potentials revisited in the frequency domain. Int J Neurosci. 1984b;23:287–299. doi: 10.3109/00207458408985580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobimatsu S, Zhang YM, Kato M. Steady-state vibration somatosensory evoked potentials: physiological characteristics and tuning function. Clin Neurophysiol. 1999;110:1953–1958. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(99)00146-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torebjörk HE, Hallin RG. Identification of afferent C units in intact human skin nerves. Brain Res. 1974;67:387–403. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90489-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towell AD, Purves AM, Boyd SG. CO2 laser activation of nociceptive and non-nociceptive thermal afferents from hairy and glabrous skin. Pain. 1996;66:79–86. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(96)03016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran TD, Inui K, Hoshiyama M, Lam K, Kakigi R. Conduction velocity of the spinothalamic tract following CO2 laser stimulation of C-fibers in humans. Pain. 2002;95:125–131. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(01)00386-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treede RD, Kief S, Hölzer T, Bromm B. Late somatosensory evoked cerebral potentials in response to cutaneous heat stimuli. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1988;70:429–441. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(88)90020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treede RD, Meyer RA, Raja SN, Campbell JN. Evidence for two different heat transduction mechanisms in nociceptive primary afferents innervating monkey skin. J Physiol. 1995;483:747–758. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treede RD, Kenshalo DR, Gracely RH, Jones AK. The cortical representation of pain. Pain. 1999;79:105–111. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00184-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treede RD, Apkarian AV, Bromm B, Greenspan JD, Lenz FA. Cortical representation of pain: functional characterization of nociceptive areas near the lateral sulcus. Pain. 2000;87:113–119. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00350-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vialatte FB, Maurice M, Dauwels J, Cichocki A. Steady-state visually evoked potentials: focus on essential paradigms and future perspectives. Prog Neurobiol. 2010;90:418–438. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitsel BL, Favorov OV, Li Y, Quibrera M, Tommerdahl M. Area 3a neuron response to skin nociceptor afferent drive. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:349–366. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woody C. Characterization of an adaptive filter for the analysis of variable latency neuroelectric signals. Med Biol Eng. 1967;5:539–553. [Google Scholar]