Abstract

Background

Apelin has recently been considered as an adipokine secreted from visceral fat. Apelin and its receptor exist in many tissues including lung and play significant roles in many physiological and pathological activities. However, serum level of apelin-12 is unknown in smokers and in various types of lung malignancies. Therefore, the amount of this hormone in non-patient smokers and the correlation of apelin serum level with the types of lung cancer in smokers afflicted with lung cancer are evaluated in this study.

Methods

The amount of serum apelin-12 was measured in 63 patients (59 smokers and 4 non-smokers) with the variety of lung cancer and 61 age- and sex-matched controls (30 smokers and 31 non-smokers) using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit.

Findings

The amount of serum apelin-12 in non-patient smokers (2142.20 ± 843.61 ng/l) was significantly higher than healthy non-smokers (800.39 ± 336.01 ng/l, P < 0.05), and in the variety of lung malignancies, the amount of serum apelin-12 was 2205.54 ± 187.31 ng/l in patients with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) which was a significant increase compared to 1088.00 ± 136.52 ng/l in adenocarcinoma, 797.25 ± 88.69 ng/l in small cell carcinoma, and 1000.37 ± 62.87 ng/l in other malignancies of lung.

Conclusion

The meaningful increase in apelin-12 levels of non-patient smokers can be considered as a risk factor for outbreaking of lung SCC in these people. Therefore, apelin-12 may be considered as a target in controlling lung SCC.

Keywords: Smoking, Apelin, Squamous cell carcinoma

Introduction

Adipose tissue known as an endocrine and immune organ was until recently thought to affect only lipid metabolism and glucose homeostasis. It is now identified as the secretion source of more than 20 types of different hormones and molecules called adipocytokine or adipokine.1 Adipose tissue plays significant biological roles in the vascular system, glucose homeostasis and energy metabolism, reproduction, bone metabolism, immune system, and cancer.2

As one of the adipokines, apelin was first isolated as a new peptide from the cow's stomach extract. In mammals, the apelin gene encodes a precursor protein with 77 amino acids which produces peptides with lengths of 36, 17, 13, and 12 amino acids.3 These peptides are from the C-terminal regions of apelin precursor protein. The apelin types of 12, 13, and 36 are the most important ones of these peptides and the types 12 and 13 have a great deal affinity with the apelin receptor.4

The apelin receptor (APJ) is a component of the receptors coupled to the G protein and firstly was detected in endothelial cells during the embryonic period when large vessels were formed.5 Apelin and its receptor (APJ) exist in many tissues such as the brain,6 fat,7 lungs, breast, and heart8 and regulate various physiological activities such as energy metabolism, hemostasis, and immunity.9 Apelin plays a role in the formation and maturation of vessels during the physiological stages as well as the pathogenicity of some diseases in which angiogenesis is of great importance.10 Apelin plasma levels have also been shown to be higher in the obese subjects than in normal people.8

Apelin and its receptor are involved in the pathogenesis of some cancers, and their amounts change in tumor tissues and cancer cell lines. Recent studies have shown that apelin has angiogenesis properties and contributes to the pathogenesis of cancer patients, so that the amount of apelin increases in patients with gastroesophageal cancer, breast cancer, and prostate cancer.11,12

As a pulmonary disease, lung cancer results from the uncontrolled growth of the lung epithelial cells and its prevalence is higher in smokers than in non-smokers.13 Lung cancer is the most common cancer in the world in terms of outbreak and death. In 2008, 1.61 million new items (12.7% of all people with all types of cancers diagnosed in this year) and 1.38 million deaths from lung cancer were reported.14 It is one of the five major cancers in Iran, being still on the rise.15 Lung cancer is mainly divided into two groups: non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) which represents 85% of cases of lung cancer and small cell lung cancer (SCLC) that represents 14% to 15% of all lung cancers. NSCLC is further sub-categorized as adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and large cell carcinoma (LCC).16

Since lung tissue is considered as an apelin expressor tissue, the present study aims to investigate (a) the amount of this hormone in non-patient smokers and (b) the correlation of apelin serum level with the types of lung cancer in smokers afflicted with lung cancer.

Methods

The subjects in this study as the patient group were the male patients (63 people: 4 non-smokers and 59 smokers) going to the pulmonary clinic of Imam Khomeini Hospital in Urmia, Iran, between October 2016 and April 2018. The control group consisted of 61 men (30 smokers and 31 non-smokers) with no history of illness, who were matched for age and body mass index (BMI). People who smoked 10 or more than 10 cigarettes per day and had the history of more than 3 months of smoking were considered to be smokers and people who never smoked were selected as non-smokers. The protocol of the study followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki having all the subjects sign the consent form, and this study was carried out with the approval of the Ethics Committee of Urmia University of Medical Sciences (No.: IR.umsu.rec.1395.284. meeting date: 9/27/2016). Initially, careful lung examinations were conducted and then the tissue biopsy specimens were sent to the histopathology laboratory for more accurate diagnosis. The blood and urine parameters for all the individuals in both groups were within normal ranges.

Before starting any type of therapeutic treatment in patients, peripheral blood was drawn from subjects after measuring their height and weight to calculate BMI. Subjects were fasting for 12 hours. After separating serum of samples, it was placed in a cooling centrifuge and spun at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes; the biochemical parameters such as fasting blood sugar (FBS), triglyceride (TG), and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) were detected via the standard protocols by a clinical chemistry autoanalyzer (BT 3000, Italy) in the laboratory of Imam Khomeini Hospital in the sampling day. Then serum was frozen at -80 ºC until the analysis of apelin. The serum apelin-12 was measured using commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Bioassay Technology Laboratory, China) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The sensitivity of the assay was 4.47 ng/l (assay range: 10-4000 ng/l). The intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variance were < 8% and < 10%, respectively.

The data were analyzed with the SPSS software (version 16, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The results were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Analyses of normally-distributed variables (age and BMI and biochemical analysis) were conducted using independent samples t-test and to determine and compare the serum level of apelin in different types of lung malignancies, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used and finally, Scheffe post-hoc test was used as well. Analyses of abnormally-distributed variables were conducted with the Mann-Whitney U test and comparisons with P-value < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

The basic characteristics of subjects are summarized in table 1. The sample included both smokers (71.8%) and non-smokers (28.2%) with a total number of 124 which was made up of 61 healthy people (49.2%) and 63 lung patients (50.8%). The age of the subjects ranged from 42 to 85 years with a mean of 61.51 ± 9.59 and the mean of BMI for the subjects was 24.49 ± 3.61. The values of other biochemical analyses (FBS, TG, LDL-C) are given in table 1.

Table 1.

The baseline characteristics of subjects

| Subjects’ characteristics | Control |

Patient |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-smoker | Smoker | Smoker | Non-smoker | |

| Number (men) | 31 | 30 | 59 | 4 |

| Age (year) | 58.87 ± 7.19 | 58.65 ± 7.82 | 60.13 ± 9.32 | 55.00 ± 6.37 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.58 ± 2.93 | 24.10 ± 2.93 | 23.82 ± 4.28 | 26.50 ± 1.73 |

| FBS (mg/dl) | 81.35 ± 9.98 | 82.16 ± 9.45 | 82.32 ± 10.44 | 81.00 ± 9.59 |

| TG (mg/dl) | 95.83 ± 7.91 | 94.30 ± 8.94 | 95.86 ± 8.97 | 93.75 ± 7.36 |

| LDL-C (mg/dl) | 79.19 ± 7.73 | 79.26 ± 9.31 | 80.13 ± 11.27 | 85.25 ± 9.63 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

BMI: Body mass index; FBS: Fasting blood sugar; TG: Triglyceride; LDL-C: Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

Number of patients with a variety of pulmonary malignancies (smoker patients): adenocarcinoma = 12, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) = 22, small cell carcinoma = 8, and others = 17

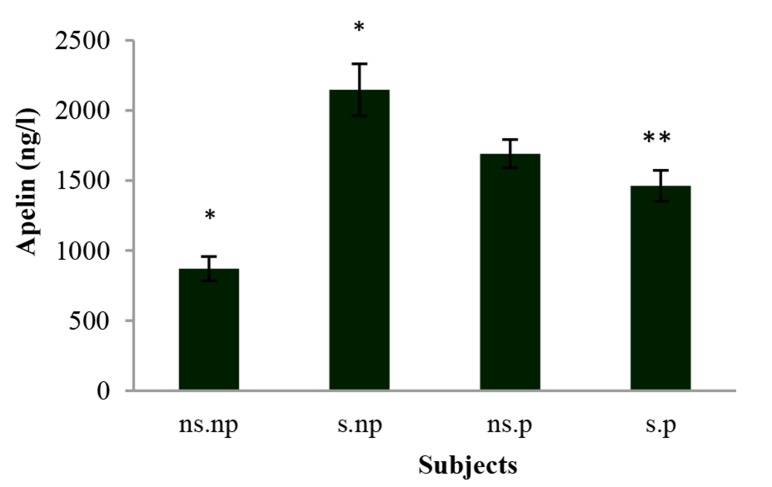

According to figure 1, the amount of apelin-12 hormone in the serum of non-patient smokers (2142.20 ± 843.61 ng/l) was higher than that of healthy non-smokers (800.39 ± 336.01 ng/l) (P < 0.05). Also, the serum level of this hormone was 1691.03 ± 101.03 ng/l in the group of non-smoker patients and 1461.92 ± 109.92 ng/l in the group of smoker patients.

Figure 1.

The levels of apelin-12 in serum of subjects ns.np: Non-smoker non-patient; s.np: Smoker non-patient; ns.p: Non-smoker patient; s.p: Smoker patient Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) *A statistically significant difference vs. ns.np; **A statistically significant difference vs. s.np

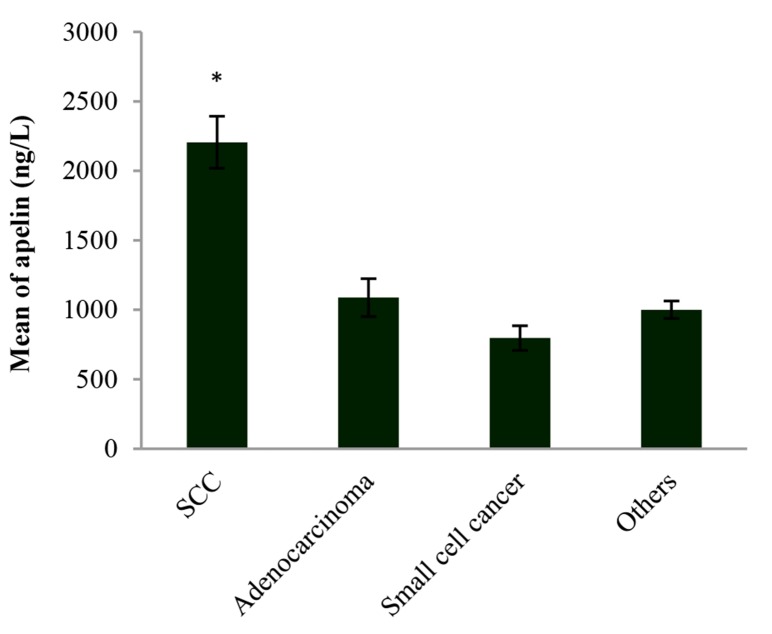

The amount of serum apelin-12 was different in a variety of pulmonary malignancies. It was 2205.54 ± 187.31 ng/l in SCC, 1088.00 ± 136.52 ng/l in adenocacinoma, 797.25 ± 88.69 ng/l in small cell carcinoma, and 1000.37 ± 62.84 ng/l in other types of lung diseases (e.g., poorly differentiated carcinoma) according to figure 2.

Figure 2.

Serum level of apelin-12 in the variety of lung malignancies Increasing plasma apelin in patients with squamous cell carcinoma (SSC) shows a significant increase compared with other patients. Data are expressed as mean. *A statistically significant difference relative to the other patients (P < 0.05) [squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) vs. adenocarcinoma, SCC vs. small cell cancer, and SCC vs. others]

Discussion

This study shows an increase in the amount of serum apelin in non-patient smokers in comparison with healthy non-smokers. Being the most harmful compound in cigarette, carbon monoxide (CO) binds to hemoglobin and forms carboxyhemoglobin (COHb), a process which leads to hypoxia.17 In vitro, hypoxia increases not only the amount of apelin gene expression in cells but also apelin protein in cell culture media.18,19 Hypoxia also increases the expression of the apelin gene, in vivo.20 Hypoxia upregulates the expression of apelin gene via hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha (HIF-1α) that binds to a hypoxia-responsive element (HRE) located within the first intron of the apelin gene.17 In children with asthma, the amount of plasma apelin increases independently of their weight.21 In addition, hypoxia increases the expression of the receptor of apelin and increases the release of apelin from the lung adenocarcinoma cells.22

The messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) of apelin receptor (APJ) is greatly expressed in the rat's lungs.23 The mortality rate was higher in patients with lung cancer whose apelin expression was upregulated as compared to that of patients with downregulated apelin expression. As a result, the high expression of apelin can be considered as an independent predicting factor in poor prognosis of cancer.24

Apelin is considered as an important proangiogenic factor in cancers.7 Apelin also increases the density of small veins in lung cancer.22 The apelin receptor is expressed in human lung adenocarcinoma tissue and the amount of this expression is higher compared to the adjacent tissues of lung cancer and is closely related to the development of tumor.25 Apelin gene expression increases in about one third of human tumors, at first apelin boosts angiogenesis and neoangiogenesis in the tumor and then it causes tumor growth.5,26 Apelin also increases metastasis in cancer cells so that apelin attenuates the effects of doxorubicin and razoxane in inhibition of metastasis of adenocarcinoma cells.22

Apelin and its receptor are expressed in gastrointestinal (GI) cells and intestinal inflammation increases the expression of HIF; apelin also causes the proliferation of cells27 and also stimulates the proliferation of cells in vitro.28,29 It is noted that apelin and APJ are expressed in human osteoblasts and cause the proliferation of osteoblasts via APJ/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathways30 and the decrease of the apoptosis in the cells.31 Moreover, apelin provokes the proliferation of cells by stimulating the cell cycle in phase S and reducing the phase G0/G1.32 It is proven that apelin stimulates cell proliferation through expression of cyclin D1 and matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1)29,33 and phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs) 1/2.30,32 ERK 1/2, a key molecule to cell proliferation, stimulates the expression of cyclin protein and promotes cell cycle progress. Among all known cyclin proteins, cyclin D1 is shown to be the most important in regulating G1 to S check-point.25

About 85% of the total lung cancer cases were NSCLC which mainly included SCC34 and adenocarcinoma, and these contain approximately 400000 deaths each year in the world.34,35 Smoking is the main cause (85%-90%) of lung cancer36 and histopathologically, outbreak of SCC is more than adenocarcinoma in smokers.35 Metastasis and recurrence are very common in SCC35 which includes the most invasive types of tumor with rapid initial growth.37 As shown in this study, the amount of serum apelin-12 in patients with SCC increases more significantly than in patients afflicted with other lung malignancies. The result can be supported by the results of some previous studies where patients with esophageal SCC had a high plasma apelin compared to patients with gastric adenocarcinoma.12 Thus, an increase in the amount of apelin in this type of tumor is associated with angiogenesis37 and the increase of apelin in patients with SCC can increase the angiogenesis and cell proliferation, followed by metastasis.

The level of serum apelin-12 increases in non-smoker patients compared to healthy subjects and it is significant but due to the small number of non-smoker patients in this study, it requires an extensive future study.

Conclusion

The significant increase in the serum level of apelin-12 in non-patient smokers may be considered as an important factor in the prognosis of SCC lung cancer in these individuals. Thus, apelin-12 may be considered as a target in the treatment and control of SCC, which can be confirmed with further future studies.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by Urmia University of Medical Sciences and Health Services under grant number of 2381-62-01-1395. We would like to thank Dr. Farhad Nemati and his colleagues in medical laboratory for their assistance in diagnosis of lung cancer in patients.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ntikoudi E, Kiagia M, Boura P, Syrigos KN. Hormones of adipose tissue and their biologic role in lung cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40(1):22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ouchi N, Ohashi K, Shibata R, Murohara T. Adipocytokines and obesity-linked disorders. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2012;74(1-2):19–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhen EY, Higgs RE, Gutierrez JA. Pyroglutamyl apelin-13 identified as the major apelin isoform in human plasma. Anal Biochem. 2013;442(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalin RE, Kretz MP, Meyer AM, Kispert A, Heppner FL, Brandli AW. Paracrine and autocrine mechanisms of apelin signaling govern embryonic and tumor angiogenesis. Dev Biol. 2007;305(2):599–614. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sorli SC, van den Berghe L, Masri B, Knibiehler B, Audigier Y. Therapeutic potential of interfering with apelin signalling. Drug Discov Today. 2006;11(23-24):1100–6. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Dowd BF, Heiber M, Chan A, Heng HH, Tsui LC, Kennedy JL, et al. A human gene that shows identity with the gene encoding the angiotensin receptor is located on chromosome 11. Gene. 1993;136(1-2):355–60. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90495-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kleinz MJ, Davenport AP. Emerging roles of apelin in biology and medicine. Pharmacol Ther. 2005;107(2):198–211. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heinonen MV, Purhonen AK, Miettinen P, Paakkonen M, Pirinen E, Alhava E, et al. Apelin, orexin-A and leptin plasma levels in morbid obesity and effect of gastric banding. Regul Pept. 2005;130(1-2):7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bertrand C, Valet P, Castan-Laurell I. Apelin and energy metabolism. Front Physiol. 2015;6:115. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kidoya H, Takakura N. Biology of the apelin-APJ axis in vascular formation. J Biochem. 2012;152(2):125–31. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvs071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang Y, Lv SY, Ye W, Zhang L. Apelin/APJ system and cancer. Clin Chim Acta. 2016;457:112–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diakowska D, Markocka-Maczka K, Szelachowski P, Grabowski K. Serum levels of resistin, adiponectin, and apelin in gastroesophageal cancer patients. Dis Markers. 2014;2014:619649. doi: 10.1155/2014/619649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furrukh M. Tobacco Smoking and Lung Cancer: Perception-changing facts. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2013;13(3):345–58. doi: 10.12816/0003255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(12):2893–917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hosseini M, Naghan PA, Karimi S, SeyedAlinaghi S, Bahadori M, Khodadad K, et al. Environmental risk factors for lung cancer in Iran: A case-control study. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38(4):989–96. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eggert JA, Palavanzadeh M, Blanton A. Screening and early detection of lung cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2017;33(2):129–40. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vellappally S, Fiala Z, Smejkalova J, Jacob V, Somanathan R. Smoking related systemic and oral diseases. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove) 2007;50(3):161–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heo K, Kim YH, Sung HJ, Li HY, Yoo CW, Kim JY, et al. Hypoxia-induced up-regulation of apelin is associated with a poor prognosis in oral squamous cell carcinoma patients. Oral Oncol. 2012;48(6):500–6. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cox CM, D'Agostino SL, Miller MK, Heimark RL, Krieg PA. Apelin, the ligand for the endothelial G-protein-coupled receptor, APJ, is a potent angiogenic factor required for normal vascular development of the frog embryo. Dev Biol. 2006;296(1):177–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.04.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eyries M, Siegfried G, Ciumas M, Montagne K, Agrapart M, Lebrin F, et al. Hypoxia-induced apelin expression regulates endothelial cell proliferation and regenerative angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2008;103(4):432–40. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.179333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Machura E, Ziora K, Ziora D, Swietochowska E, Krakowczyk H, Halkiewicz F, et al. Serum apelin-12 level is elevated in schoolchildren with atopic asthma. Respir Med. 2013;107(2):196–201. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lv D, Li L, Lu Q, Li Y, Xie F, Li H, et al. PAK1-cofilin phosphorylation mediates human lung adenocarcinoma cells migration induced by apelin-13. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2016;43(5):569–79. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawamata Y, Habata Y, Fukusumi S, Hosoya M, Fujii R, Hinuma S, et al. Molecular properties of apelin: tissue distribution and receptor binding. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1538(2-3):162–71. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(00)00143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berta J, Kenessey I, Dobos J, Tovari J, Klepetko W, Jan AH, et al. Apelin expression in human non-small cell lung cancer: role in angiogenesis and prognosis. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5(8):1120–9. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181e2c1ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang L, Su T, Lv D, Xie F, Liu W, Cao J, et al. ERK1/2 mediates lung adenocarcinoma cell proliferation and autophagy induced by apelin-13. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2014;46(2):100–11. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmt140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sorli SC, Le GS, Knibiehler B, Audigier Y. Apelin is a potent activator of tumour neoangiogenesis. Oncogene. 2007;26(55):7692–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han S, Wang G, Qi X, Lee HM, Englander EW, Greeley GH. A possible role for hypoxia-induced apelin expression in enteric cell proliferation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294(6):R1832–R1839. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00083.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang G, Anini Y, Wei W, Qi X, OCarroll AM, Mochizuki T, et al. Apelin, a new enteric peptide: localization in the gastrointestinal tract, ontogeny, and stimulation of gastric cell proliferation and of cholecystokinin secretion. Endocrinology. 2004;145(3):1342–8. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peng X, Li F, Wang P, Jia S, Sun L, Huo H. Apelin-13 induces MCF-7 cell proliferation and invasion via phosphorylation of ERK1/2. Int J Mol Med. 2015;36(3):733–8. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2015.2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xie H, Tang SY, Cui RR, Huang J, Ren XH, Yuan LQ, et al. Apelin and its receptor are expressed in human osteoblasts. Regul Pept. 2006;134(2-3):118–25. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang SY, Xie H, Yuan LQ, Luo XH, Huang J, Cui RR, et al. Apelin stimulates proliferation and suppresses apoptosis of mouse osteoblastic cell line MC3T3-E1 via JNK and PI3-K/Akt signaling pathways. Peptides. 2007;28(3):708–18. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Masri B, Morin N, Cornu M, Knibiehler B, Audigier Y. Apelin (65-77) activates p70 S6 kinase and is mitogenic for umbilical endothelial cells. FASEB J. 2004;18(15):1909–11. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1930fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li F, Li L, Qin X, Pan W, Feng F, Chen F, et al. Apelin-induced vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation: the regulation of cyclin D1. Front Biosci. 2008;13:3786–92. doi: 10.2741/2967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li B, Chen P, Wang JH, Li L, Gong JL, Yao H. Ferrerol overcomes the invasiveness of lung squamous cell carcinoma cells by regulating the expression of inducers of Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition. Microb Pathog. 2017;112:171–5. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park SK, Cho LY, Yang JJ, Park B, Chang SH, Lee KS, et al. Lung cancer risk and cigarette smoking, lung tuberculosis according to histologic type and gender in a population based case-control study. Lung Cancer. 2010;68(1):20–6. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ermin S, Cok G, Veral A, Kose T. The role of apelin in the assessment of response to chemotherapyand prognosis in stage 4 nonsmall cell lung cancer. Turk J Med Sci. 2016;46(5):1353–9. doi: 10.3906/sag-1411-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goldenberg A, Ortiz A, Kim SS, Jiang SB. Squamous cell carcinoma with aggressive subclinical extension: 5-year retrospective review of diagnostic predictors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(1):120–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]