Abstract

The etiology of Alzheimer's disease (AD) remains elusive. The “amyloid” hypothesis states that toxic action of accumulated β-amyloid peptide (Aβ) on synaptic function causes AD cognitive decline. This hypothesis is supported by analysis of familial AD (FAD)-based transgenic mouse models, where altered amyloid precursor protein (APP) processing leads to Aβ accumulation correlating with hippocampal-dependent memory deficits. Some studies report prominent dentate gyrus (DG) glutamatergic plasticity alterations in these mice, while CA1 plasticity remains relatively unaffected. The “neurotrophic unbalance” hypothesis, on the other hand, states that AD-related loss of cholinergic signaling and altered APP processing are due to alterations in nerve growth factor (NGF) trophic support. This hypothesis is supported by analysis of the AD11 mouse, which exhibits chronic NGF deprivation during adulthood and displays AD-like pathology, including Aβ accumulation and hippocampal-dependent memory deficits. In this study, we analyzed CA1 and DG glutamatergic plasticity in AD11 mice to evaluate whether these mice also share with FAD models a common phenotype in hippocampal synaptic dysfunction. We report that AD11 mice display age-dependent short- and long-term DG plasticity deficits, while CA1 plasticity remains relatively spared. We also report that both structures exhibit enhanced glutamatergic transmission under lower, yet physiological, neurotransmitter release conditions, a defect that should be considered when further evaluating hippocampal synaptic deficits underlying AD pathology. We conclude that severe deficits in DG plasticity represent another common denominator between these two etiologically different types of AD mouse models, independent of the initial insult (overexpression of FAD mutation or NGF deprivation).

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is characterized by progressive accumulation of β-amyloid peptide (Aβ) and hyperphosphorylated tau tangles in the hippocampus and neocortex, loss of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons (BFCNs) projecting to these two memory-encoding areas, and synaptic degeneration (Blennow et al., 2006). How these alterations relate to each other and which of them drive memory loss characteristic of AD is a matter of debate. Mutations in the amyloid precursor protein (APP) and presenilin genes occur in early-onset familial AD (FAD), resulting in altered APP processing and accumulation of Aβ into oligomers and then into plaques (Tanzi and Bertram, 2005). The “amyloid” hypothesis states that the toxic action of Aβ on synaptic function is responsible for memory loss (LaFerla and Oddo, 2005; Bell and Cuello, 2006). This hypothesis is supported by analysis of transgenic mice overexpressing human FAD mutations, which display Aβ accumulation and plaque formation correlating with hippocampal-dependent memory deficits (Duyckaerts et al., 2008). Although the extent of hippocampal synaptic deficits of FAD mouse models is still under debate, comparative studies in these mice suggest that dentate gyrus (DG) glutamatergic plasticity might be more severely compromised than CA1 plasticity (Chapman et al., 1999; Palop et al., 2007) (but see Fitzjohn et al., 2001).

Other studies led to the “neurotrophic deficit” hypothesis, more recently refined as “neurotrophic unbalance,” which states that loss of BFCNs and altered APP processing are triggered by reduced mature NGF availability and thus a lower NGF/proNGF ratio, leading to AD pathology including Aβ accumulation and cognitive impairments (Cuello and Bruno, 2007; Cattaneo et al., 2008; Capsoni et al., 2010b). This hypothesis is supported by analysis of AD11 transgenic mice, where anti-NGF antibodies, neutralizing NGF versus proNGF, are expressed both peripherally and within the CNS from postnatal day 45, thus reducing mature NGF availability (50% NGF bound) throughout adulthood (Ruberti et al., 2000). This mouse model provided evidence correlating NGF deprivation and Aβ accumulation, a molecular link further confirmed by other recent studies (Matrone et al., 2008; Nikolaev et al., 2009). Beside Aβ accumulation, AD11 mice display a comprehensive AD-like pathology including Aβ plaques, loss of BFCNs, hyperphosphorylated tau tangles, and hippocampal-dependent memory deficits (Cattaneo et al., 2008). Six-month-old AD11 mice exhibited normal CA1 glutamatergic transmission and long-term potentiation (LTP), but abnormal nicotine-dependent synaptic plasticity modulation and abnormal GABA excitatory activity (Rosato-Siri et al., 2006; Sola et al., 2006; Lagostena et al., 2010).

Common denominators to these two etiologically different types of AD models, supporting alternative hypotheses, are Αβ accumulation and hippocampal-dependent memory deficits. To evaluate whether these two types of models also share common phenotypes of hippocampal synaptic dysfunction, we further investigated CA1 and DG synaptic transmission and plasticity in AD11 mice. We demonstrate that, like FAD mice, fully symptomatic AD11 mice display severe DG, but mild CA1 plasticity deficits, thus identifying DG plasticity defects as another shared phenotype between these models. We also report enhanced glutamatergic transmission under low neurotransmitter release conditions in both structures, a new synaptic alteration to consider when evaluating the contribution of hippocampal synaptic deficits in AD.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

AD11 mice express a recombinant monoclonal antibody αD11 that specifically neutralizes NGF. AD11 mice were produced as described previously (Ruberti et al., 2000). Wild-type (WT) mice displayed an identical genetic background, but did not express the antibody.

Electrophysiology.

Experimental days on AD11 and WT mice were interleaved whenever possible. Four-hundred-micrometer transverse hippocampal slices were prepared for electrophysiology using standard procedures (Marchetti et al., 2010). Slices were incubated in ACSF containing the following (in mm): 119 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, 2.5 KCl, 1 NaH2PO4, 1.3 MgSO4, 2.5 CaCl2, 11 glucose, gassed with 95% O2/5% CO2, pH 7.4, and recorded at 32 ± 1°C.

All recordings were performed in ACSF+100 μm picrotoxin (Sigma-Aldrich) to block inhibitory GABAergic transmission. Stimulating electrodes (ACSF-filled monopolar glass pipettes) were placed in the middle molecular layer of DG to stimulate granule cell synapses contacting the medial perforant pathway (MPP–DG) or in the CA1 stratum radiatum to stimulate CA1 pyramidal synapses contacting the Schaffer collateral pathway (SC–CA1). Recording electrodes (filled with 1 mm NaCl+10 mm HEPES, pH 7.4) were placed in the proximal molecular layer of DG or in the middle of the CA1 stratum radiatum. Field EPSPs (fEPSPs) were evoked at 0.1 Hz. For DG recordings, stimulation of the MPP was systematically checked by verifying that stimulated fibers displayed paired-pulse depression at 100 ms interstimulus interval (ISI) (Colino and Malenka, 1993).

Input/output curves were generated by calculating the fEPSP initial slope (to avoid population spike contamination) corresponding to a given fiber volley (FV) amplitude (100 to 300 μV in increments of 50 μV, 10 sweeps average). For paired-pulse ratios (PPRs), an fEPSP of ∼50% of the maximum was obtained and two stimuli were delivered from 50 to 400 ms ISI. PPRs were calculated as fEPSP2slope/fEPSP1slope (10 sweeps average per ISI). The synaptic repetitive stimulation protocol was induced by trains of stimulation (15 pulses at 40 Hz) in presence of 100 μm dl-APV (Tocris Bioscience) to block NMDA receptors. Slopes of all fEPSPs were normalized to the slope of the first EPSP of the train.

LTP field recordings were induced after 15 min of stable EPSP slope set at ∼50% of maximum. LTP was induced using theta burst stimulation (TBS): 10 bursts at 5 Hz repeated 10 times in 15 s intervals. Each burst consisted of four pulses of 100 Hz (Palop et al., 2007). SC–CA1 LTP was also tested with high-frequency stimulation (100 Hz for 1 s).

For recordings under low release probability conditions, the ACSF calcium/magnesium ratio was changed from 2.5/1.3 to 1/2 mm. Magnesium concentration was increased to keep adequate membrane surface potential.

Spine density analysis.

Spine density and shape analysis was performed on 6- to 7-month-old AD11 and WT mice using the Golgi–Cox impregnation method as described by Restivo et al. (2005).

Data analysis and statistics.

Data are shown as mean ± SEM. “n” = number of fields and “N” = number of animals examined for each experiment. Prism (GraphPad) was used for statistical analysis using the Student's t test. Results were considered significantly different if p < 0.05.

Results

AD11 mice display DG and CA1 glutamatergic short-term plasticity deficits

Our previous analysis using 6-month-old AD11 mice demonstrated normal basic synaptic transmission [analyzed by fEPSP input/output (I/O) curves], presynaptic release (analyzed by fEPSP PPR), and LTP at the Schaffer collateral to CA1 pyramidal synapse (SC–CA1), suggesting that synaptic function was still normal at this age (Rosato-Siri et al., 2006). We therefore analyzed SC–CA1 glutamatergic synaptic function at 11–13 months, when AD11 mice display strong AD-like neurodegeneration (see supplemental Table S1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material, for summary of AD pathology). Basic synaptic transmission, which is mainly mediated by the AMPA receptors (AMPARs), was evaluated by obtaining I/O curves. I/O curves were generated by plotting fEPSP slopes against FV amplitude, which is a measure of presynaptic fiber activation. This I/O relationship did not differ between AD11 and WT mice (Fig. 1A), suggesting no major alteration in basic glutamatergic synaptic transmission.

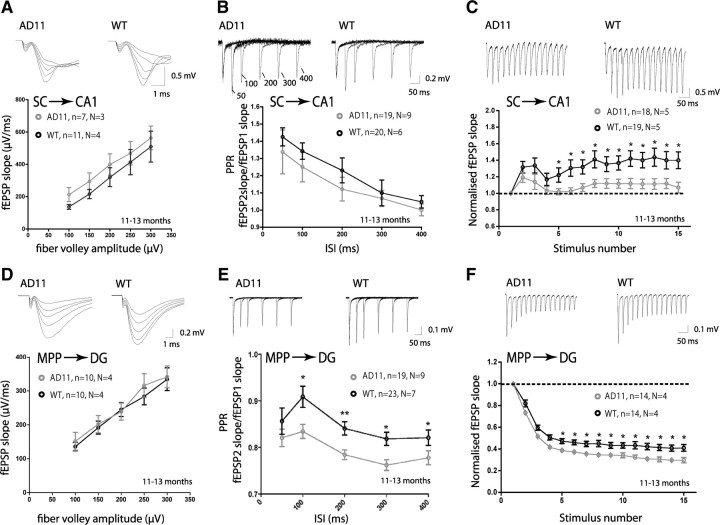

Figure 1.

Short-term plasticity deficits at the SC–CA1 and MPP–DG synapses of fully symptomatic (11–13 months) AD11 mice. A, SC–CA1 synapse input–output curves (fEPSP slopes versus increasing afferent FV amplitudes) were similar in aged-matched WT and AD11 mice (n = slices, N= mice). B, SC–CA1 synapse PPRs (fEPSP2 slope/fEPSP1 slope) were similar in WT and AD11 mice at all ISIs examined. C, Synaptic facilitation during repeated stimulation (15 pulses at 40 Hz) was significantly reduced at the SC–CA1 synapse from the fifth stimulus onwards in AD11 compared to WT mice (normalized to first response of train). D, MPP–DG synapse input–output curves were similar in WT and AD11 mice. E, PPR was altered, displaying increased depression, at the MPP–DG synapse of AD11 compared to WT mice. F, Synaptic depression during repeated stimulation (15 pulses at 40 Hz) was increased at the MPP–DG synapse from the fifth stimulus onwards in AD11 compared to WT mice (normalized to first response of train). Representative traces of fEPSP recordings of responses at FV intensities 100–300 μV (A, D), of PPR (all ISIs) (B, E), and of the train of fEPSPs (C, F) are shown above graphs for WT and AD11 mice. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

We next investigated short-term regulation of neurotransmitter release by measuring PPRs. AD11 and WT mice displayed similar facilitation, typical of this synapse, as reported by an increase in the second synaptic response relative to the first response (fEPSP2slope/fEPSP1slope) at all ISIs examined (Fig. 1B). We also analyzed the behavior of this synapse during a train of stimuli at moderate frequency (15 pulses at 40 Hz), which produced sustained facilitation for the entire duration of the train in WT mice (Fig. 1C). Conversely, synaptic transmission in AD11 mice could not sustain this facilitation beyond the fourth stimulus (Fig. 1C) (p > 0.05 up to fourth stimulus, p < 0.05 beyond fourth stimulus), suggesting a defect in the dynamics of glutamate transmission during moderate stimulation frequency. To ensure that this defect was not due to an early developmental abnormality resulting from transgene expression, but correlated with aging, we repeated this experiment in 1-month-old AD11 and WT mice. At this nonsymptomatic age (supplemental Table S1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material), synaptic facilitation was sustained throughout the train in both genotypes (p > 0.05) (supplemental Fig. S1A, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material), suggesting an age-dependent defect, although we cannot exclude developmental alterations beyond 1 month of age.

We performed identical experiments while stimulating the medial perforant pathway to DG granule cell synapse (MPP–DG). Basic synaptic transmission appeared normal at this synapse as demonstrated by the I/O curve (Fig. 1D). Paired-pulse depression (PPD), which is typical of this synapse, was, however, increased in AD11 mice, as revealed by PPR analysis (Fig. 1E). This presynaptic plasticity defect became apparent during aging as PPD was normal at 1 month but increased at 3–4 months of age (supplemental Fig. S2A,B, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material), correlating with early AD-like neurodegeneration (supplemental Table S1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). The MPP–DG synapse also displayed more pronounced depression during a moderate train of stimuli (15 pulses at 40 Hz) compared to WT from the fifth stimulus onwards in 11- to 13-month-old mice (Fig. 1F) (p > 0.05 up to fourth stimulus, p < 0.05 beyond fourth stimulus). Again, this defect was probably not due to a developmental abnormality, since nonsymptomatic 1-month-old AD11 mice displayed normal synaptic depression during this train (p > 0.05) (supplemental Fig. S1B, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material).

AD11 mice display normal SC–CA1 LTP but severe deficits in MPP–DG LTP

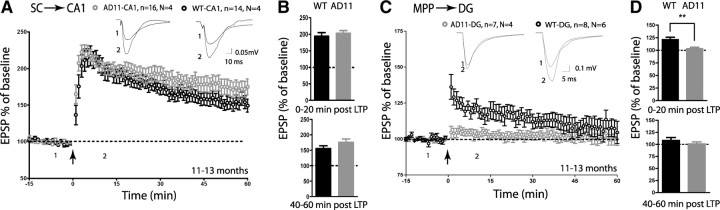

We also investigated LTP of the AMPAR response at these two synapses in 11- to 13-month-old mice. We used a TBS protocol previously used to reveal defects in DG plasticity in a FAD model (Palop et al., 2007). LTP at the SC–CA1 synapse was normal when compared to aged-matched WT controls (Fig. 2A,B) (0–20 min after LTP: WT: 194.8 ± 10.47%; AD11: 203.8 ± 7.23%, p > 0.05), suggesting presence of an intact molecular machinery both for induction and expression of TBS-LTP at this synapse. Eleven- to thirteen-month-old AD11 also displayed normal high-frequency stimulation-induced LTP at the SC–CA1 synapse (supplemental Fig. S3, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). In contrast, TBS-LTP at the MPP–DG synapse was severely impaired in AD11 mice compared to WT (Fig. 2C,D) (0–20 min after LTP: WT: 121.3 ± 4.56%; AD11: 103.6 ± 2.38%, p < 0.05). Our data suggest that induction of LTP is particularly impaired at this synapse, as a notable difference was detected within the first minutes after induction. This defect became apparent during aging as MPP–DG LTP was normal in 3–4 months, but already defective in 6- to 7-month-old AD11 mice (supplemental Fig. S4A,B, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). Defective LTP correlated with a small, but significant and specific, reduction in the density of thin spines in AD11 mice compared to WT mice (WT: 2.3 ± 0.3% spines/10 μm; AD11: 1.4 ± 0.2 spines/10 μm, p < 0.05; 12 neurons/4 animals analyzed per genotype) on the proximal dendrites of the DG granule cell (see supplemental Fig. S5, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material, for full morphological analysis). These thin spines are sometimes referred to as candidate “learning spines” as they are highly dynamic, especially during LTP, and are likely to participate in stabilization of new experience-dependent synaptic contacts (Bourne and Harris, 2007).

Figure 2.

LTP was normal at the SC–CA1 synapse, but defective at the MPP–DG synapse in fully symptomatic (11–13 months) AD11 mice. A, Summary graphs of TBS-LTP (arrow) elicited at the SC–CA1 synapse of AD11 and WT mice (n = slices, N= mice). B, Summary of fEPSP magnitude 0–20 min and 40–60 min after LTP induction (time 0) at the SC–CA1 synapse as percentage of baseline. C, Summary graphs of TBS-LTP (arrow) elicited at the MPP–DG synapse of AD11 and WT mice. D, Summary of fEPSP magnitude 0–20 min and 40–60 min after LTP induction (time 0) at the MPP–DG synapse as percentage of baseline. Traces in A and C show sample fEPSPs before LTP induction (1) and after LTP induction (2; 10–20 min after induction). **p < 0.01.

We therefore conclude that the SC–CA1 synapse is only mildly affected by NGF deprivation displaying reduced short-term facilitation during moderate simulation frequency, even in the presence of several markers of AD-like neurodegeneration within the hippocampus. In contrast, the MPP–DG synapse is more severely affected by chronic NGF deprivation as it displays a progressive age-dependent increase of short-term depression during both paired and trains of stimuli and it loses the ability to display LTP.

AD11 mice display enhanced synaptic transmission at both synapses under conditions of low release probability

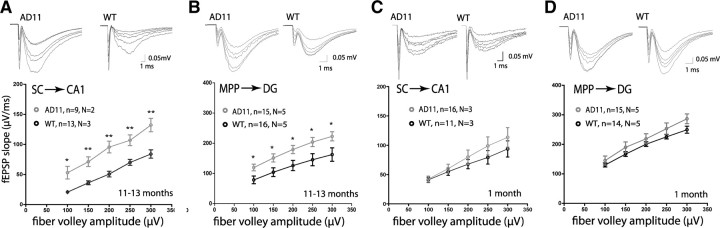

Both the decrease in facilitation at the SC–CA1 synapse and the increase in depression at the MPP–DG synapse displayed at 40 Hz (Fig. 1C,F) could be due to an increase in initial transmitter release probability (Zucker and Regehr, 2002). We, however, did not detect an increase in synaptic transmission in our I/O curves measurements (Fig. 1A,D). Interestingly, a recent paper reported that endogenously released Αβ positively regulates release probability only under low release conditions (low extracellular calcium) (Abramov et al., 2009). To further explore this possibility, we assayed the I/O relationship under conditions of lower release probability by decreasing the extracellular calcium concentration [Ca2+]o (from the standard 2.5 mm to 1 mm). Under these conditions, we observed a significant difference in the I/O curves at both synapses (Fig. 3A,B) (p < 0.05 at all FV amplitudes). This phenotype was probably not due to a developmental abnormality since 1-month-old AD11 mice displayed normal I/O relationship at both synapses under identical conditions (Fig. 3C,D). We therefore demonstrate that these synapses display an increase in initial neurotransmitter release that only becomes apparent under a lower, yet physiological, [Ca2+]o (Jones and Keep, 1988).

Figure 3.

AD11 mice display enhanced synaptic transmission at both synapses under conditions of low release probability. Recordings of hippocampal slices were performed in [Ca2+]o of 1 mm (n = slices, N= mice), leading to conditions of low release probability. A, The input–output curve was significantly altered, displaying enhanced transmission, at the SC–CA1 synapse of 11- to 13-month-old AD11 compared to WT mice. B, The input–output curve was significantly altered, displaying enhanced transmission, at the MPP–DG synapse of 11- to 13-month-old AD11 compared to WT mice. C, The input–output curve at the SC–CA1 synapse of AD11 was similar to WT mice at 1 month of age. D, The input–output curve at the MPP–DG synapse of AD11 was similar to WT mice at 1 month of age. Representative fEPSP recordings are shown with each graph for FV intensities 100–300 μV.

Discussion

Our data demonstrate that chronic NGF deprivation and consequent age-dependent appearance of AD-like neurodegeneration affect synaptic transmission and short-term plasticity of both the SC–CA1 and the MPP–DG synapses. In fully symptomatic AD11 mice, both synapses display normal I/O relationships in standard recording conditions, but enhanced transmission in conditions of lower release probability. These data suggest that, at this age, both synapses harbor a defect in the mechanism of presynaptic glutamate release, which is sensitive to [Ca2+]o and only revealed under conditions of low release probability. In addition, lowering calcium may have enabled us to examine only a subset of synapses with high release probability, which might be particularly affected in our mouse model. Also, both synapses differ from their WT controls when responding to moderate stimulation frequency (40 Hz), as the SC–CA1 synapse cannot sustain facilitation and the MPP–DG synapse displays enhanced depression. These data suggest a defect in the presynaptic short-term plasticity mechanisms, although alterations in postsynaptic function cannot be excluded at that frequency (e.g., altered AMPAR desensitization).

The SC–CA1 synapse displays normal PPR facilitation and normal LTP, suggesting that these two types of SC–CA1 plasticities are resistant to chronic NGF deprivation and ongoing AD-like neurodegeneration. In contrast, the MPP–DG synapse displays age-dependent defects in both PPR and LTP, with enhanced depression during pairs of stimuli being observed from 3 to 4 months onwards, and deficits in LTP induction being observed from 6 to 7 months onwards. These data suggest that short and long-term synaptic plasticities at the MPP–DG synapse are more strongly affected by chronic CNS NGF deprivation and ongoing AD-like neurodegeneration than at the SC–CA1 synapse. During human AD progression, it is likely that defective CNS NGF signaling at different levels (defective receptor expression, transport, processing, or degradation) could result in this symptomatology (Counts and Mufson, 2005; Bruno et al., 2009), although we cannot exclude some systemic effect of NGF deprivation on this phenotype (Capsoni et al., 2010a).

Are the alterations in hippocampal function observed in AD11 mice comparable to data obtained in FAD mouse models? Identifying a common hippocampal functional deficit in these two types of AD models, which support etiologically different hypotheses (the “neurotrophic unbalance” hypothesis for AD11 mice and the “amyloid” hypothesis for FAD mice), will provide important information on the functional alterations underlying AD cognitive decline and help unite these two hypotheses. Using the AD11 mouse, we reach a similar conclusion to the recent analysis of a FAD-derived mouse model (Palop et al., 2007), arguing for defects in PPR and LTP paradigms in DG, but not in CA1. We have therefore identified severe deficits in DG plasticity as another common denominator between the two types of models. Collectively, these findings further define the common consequences (Aβ accumulation, DG plasticity deficits, and hippocampal-dependent memory deficits) associated with AD pathology in etiologically divergent mouse models independent of the initial insult (overexpression of human FAD mutation or NGF deprivation). We can only speculate as to the molecular mechanism that might explain the similarities discovered between the two types of models. It is possible that glutamatergic synaptic activity and plasticity of the DG granule cells are particularly sensitive to Aβ accumulation. Since the DG is necessary for mnemonic processing of spatial information (Kesner, 2007), a defect in its function could significantly influence hippocampal-dependent memory. Furthermore, we detect enhanced glutamatergic transmission in CA1 and DG under conditions of low release probability, and we recently reported a major change in hippocampal GABAergic transmission in AD11 mice, with a shift from inhibition to excitation (Lagostena et al., 2010). These findings suggest an increase in excitatory drive in these mice. They corroborate and strengthen a recent and novel concept reached using FAD mice, which argue that AD neurodegeneration triggers aberrant excitatory network activity and remodeling of inhibitory circuits (Palop et al., 2006, 2007) and indicate that further research on hippocampal network dynamics in AD mouse models is warranted.

The enhanced synaptic transmission observed at both the SC–CA1 and MPP–DG synapses under lower [Ca2+]o (1 mm), but not under release conditions routinely used for in vitro electrophysiology (2.5 mm [Ca2+]o), is particularly intriguing. This conclusion is similar to the recent study reporting that endogenous released Aβ enhances synaptic release only under similar low release conditions (Abramov et al., 2009). In this study, the authors correlated this enhancement to the acute action of endogenously released Aβ. As we observe a similar result after Aβ accumulation via chronic NGF deprivation, we can also speculate that chronic Aβ accumulation positively influences glutamate release under low release conditions. Importantly, it is worth noting that [Ca2+]o in the CSF in vivo ranges between 1 and 2 mm, decreasing with age (Jones and Keep, 1988). Most studies assessing glutamatergic synaptic function and plasticity in FAD mouse models have used standard artificial CSF containing [Ca2+]o in the 2–2.5 mm range and would not have appreciated these particular synaptic defects (e.g., Chapman et al., 1999; Hsia et al., 1999; Fitzjohn et al., 2001; Oddo et al., 2003; Palop et al., 2007). Our data in combination with the other recent observation (Abramov et al., 2009) suggest a potentially overlooked Aβ-linked alteration of transmission during AD pathology that might uniquely occur in the aging brain in the context of decreasing CSF calcium levels.

We conclude that chronic NGF deprivation, which leads to NGF versus proNGF unbalance and AD-like pathology, severely affects DG glutamatergic plasticity, thus identifying this deficit as another phenotype shared by etiologically different AD mouse models. Studies will be required to understand why the DG is selectively impaired. Furthermore, the enhanced glutamatergic transmission only occurring under low release probability conditions in AD11 mice represents another parameter that should be considered when evaluating AD-related synaptic deficits. These defects probably underlie hippocampal-dependent memory deficits that contribute to cognitive decline during AD.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the American Alzheimer Association (NIRG-08-91170 to H.M.; supporting A.R.), the European Commission Coordination Action ENINET (contract number LSHM-CT-2005-19063) (H.M.), EU FP6-STREP-Memories Grant 037831 to A.C. (supporting G.H.), and the Italian Institute of Technology. We greatly appreciated critical review of this manuscript by Alberto Bacci (European Brain Research Institute, Italy), Enrico Cherubini (International School for Advanced Studies, Italy), Corinne Beurrier (Development Biology Institute of Marseille Luminy, France), and Nicole Calakos (Duke University). G.H., H.M., and C.M. performed and analyzed the electrophysiology recordings. A.R. performed the spine analysis and helped with analysis of recordings. G.A. performed anti-NGF ELISA assays. S.C. bred and genotyped the mice and provided advice. A.C. provided the input to the project and advice throughout. H.M. supervised design, analysis, and interpretation of all experiments and wrote the manuscript.

References

- Abramov E, Dolev I, Fogel H, Ciccotosto GD, Ruff E, Slutsky I. Amyloid-beta as a positive endogenous regulator of release probability at hippocampal synapses. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1567–1576. doi: 10.1038/nn.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell KF, Cuello AC. Altered synaptic function in Alzheimer's disease. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;545:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blennow K, de Leon MJ, Zetterberg H. Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 2006;368:387–403. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne J, Harris KM. Do thin spines learn to be mushroom spines that remember? Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:381–386. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno MA, Mufson EJ, Wuu J, Cuello AC. Increased matrix metalloproteinase 9 activity in mild cognitive impairment. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68:1309–1318. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181c22569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capsoni S, Tiveron C, Amato G, Vignone D, Cattaneo A. Peripheral neutralization of nerve growth factor induces immunosympathectomy and central neurodegeneration in transgenic mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010a;20:527–546. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-091357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capsoni S, Tiveron C, Vignone D, Amato G, Cattaneo A. Dissecting the involvement of tropomyosin-related kinase A and p75 neurotrophin receptor signaling in NGF deficit-induced neurodegeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010b;107:12299–12304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007181107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattaneo A, Capsoni S, Paoletti F. Towards non invasive nerve growth factor therapies for Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008;15:255–283. doi: 10.3233/jad-2008-15210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman PF, White GL, Jones MW, Cooper-Blacketer D, Marshall VJ, Irizarry M, Younkin L, Good MA, Bliss TV, Hyman BT, Younkin SG, Hsiao KK. Impaired synaptic plasticity and learning in aged amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:271–276. doi: 10.1038/6374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colino A, Malenka RC. Mechanisms underlying induction of long-term potentiation in rat medial and lateral perforant paths in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 1993;69:1150–1159. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.4.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Counts SE, Mufson EJ. The role of nerve growth factor receptors in cholinergic basal forebrain degeneration in prodromal Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2005;64:263–272. doi: 10.1093/jnen/64.4.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuello AC, Bruno MA. The failure in NGF maturation and its increased degradation as the probable cause for the vulnerability of cholinergic neurons in Alzheimer's disease. Neurochem Res. 2007;32:1041–1045. doi: 10.1007/s11064-006-9270-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duyckaerts C, Potier MC, Delatour B. Alzheimer disease models and human neuropathology: similarities and differences. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;115:5–38. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0312-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzjohn SM, Morton RA, Kuenzi F, Rosahl TW, Shearman M, Lewis H, Smith D, Reynolds DS, Davies CH, Collingridge GL, Seabrook GR. Age-related impairment of synaptic transmission but normal long-term potentiation in transgenic mice that overexpress the human APP695SWE mutant form of amyloid precursor protein. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4691–4698. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-13-04691.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsia AY, Masliah E, McConlogue L, Yu GQ, Tatsuno G, Hu K, Kholodenko D, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA, Mucke L. Plaque-independent disruption of neural circuits in Alzheimer's disease mouse models. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:3228–3233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones HC, Keep RF. Brain fluid calcium concentration and response to acute hypercalcaemia during development in the rat. J Physiol. 1988;402:579–593. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesner RP. A behavioral analysis of dentate gyrus function. Prog Brain Res. 2007;163:567–576. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)63030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFerla FM, Oddo S. Alzheimer's disease: Abeta, tau and synaptic dysfunction. Trends Mol Med. 2005;11:170–176. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagostena L, Rosato-Siri M, D'Onofrio M, Brandi R, Arisi I, Capsoni S, Franzot J, Cattaneo A, Cherubini E. In the adult hippocampus, chronic nerve growth factor deprivation shifts GABAergic signaling from the hyperpolarizing to the depolarizing direction. J Neurosci. 2010;30:885–893. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3326-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti C, Tafi E, Middei S, Rubinacci MA, Restivo L, Ammassari-Teule M, Marie H. Synaptic adaptations of CA1 pyramidal neurons induced by a highly effective combinational antidepressant therapy. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matrone C, Ciotti MT, Mercanti D, Marolda R, Calissano P. NGF and BDNF signaling control amyloidogenic route and Abeta production in hippocampal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13139–13144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806133105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaev A, McLaughlin T, O'Leary DD, Tessier-Lavigne M. APP binds DR6 to trigger axon pruning and neuron death via distinct caspases. Nature. 2009;457:981–989. doi: 10.1038/nature07767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Oddo S, Caccamo A, Shepherd JD, Murphy MP, Golde TE, Kayed R, Metherate R, Mattson MP, Akbari Y, LaFerla FM. Triple-transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease with plaques and tangles: intracellular Abeta and synaptic dysfunction. Neuron. 2003;39:409–421. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palop JJ, Chin J, Mucke L. A network dysfunction perspective on neurodegenerative diseases. Nature. 2006;443:768–773. doi: 10.1038/nature05289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palop JJ, Chin J, Roberson ED, Wang J, Thwin MT, Bien-Ly N, Yoo J, Ho KO, Yu GQ, Kreitzer A, Finkbeiner S, Noebels JL, Mucke L. Aberrant excitatory neuronal activity and compensatory remodeling of inhibitory hippocampal circuits in mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 2007;55:697–711. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restivo L, Ferrari F, Passino E, Sgobio C, Bock J, Oostra BA, Bagni C, Ammassari-Teule M. Enriched environment promotes behavioral and morphological recovery in a mouse model for the fragile X syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:11557–11562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504984102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosato-Siri M, Cattaneo A, Cherubini E. Nicotine-induced enhancement of synaptic plasticity at CA3-CA1 synapses requires GABAergic interneurons in adult anti-NGF mice. J Physiol. 2006;576:361–377. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.114587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruberti F, Capsoni S, Comparini A, Di Daniel E, Franzot J, Gonfloni S, Rossi G, Berardi N, Cattaneo A. Phenotypic knockout of nerve growth factor in adult transgenic mice reveals severe deficits in basal forebrain cholinergic neurons, cell death in the spleen, and skeletal muscle dystrophy. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2589–2601. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-07-02589.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sola E, Capsoni S, Rosato-Siri M, Cattaneo A, Cherubini E. Failure of nicotine-dependent enhancement of synaptic efficacy at Schaffer-collateral CA1 synapses of AD11 anti-nerve growth factor transgenic mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24:1252–1264. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanzi RE, Bertram L. Twenty years of the Alzheimer's disease amyloid hypothesis: a genetic perspective. Cell. 2005;120:545–555. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RS, Regehr WG. Short-term synaptic plasticity. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002;64:355–405. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.092501.114547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]