Abstract

Endocannabinoids (eCBs) function as retrograde signaling molecules at synapses throughout the brain, regulate axonal growth and guidance during development, and drive adult neurogenesis. There remains a lack of genetic evidence as to the identity of the enzyme(s) responsible for the synthesis of eCBs in the brain. Diacylglycerol lipase-α (DAGLα) and -β (DAGLβ) synthesize 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol (2-AG), the most abundant eCB in the brain. However, their respective contribution to this and to eCB signaling has not been tested. In the present study, we show ∼80% reductions in 2-AG levels in the brain and spinal cord in DAGLα−/− mice and a 50% reduction in the brain in DAGLβ−/− mice. In contrast, DAGLβ plays a more important role than DAGLα in regulating 2-AG levels in the liver, with a 90% reduction seen in DAGLβ−/− mice. Levels of arachidonic acid decrease in parallel with 2-AG, suggesting that DAGL activity controls the steady-state levels of both lipids. In the hippocampus, the postsynaptic release of an eCB results in the transient suppression of GABA-mediated transmission at inhibitory synapses; we now show that this form of synaptic plasticity is completely lost in DAGLα−/− animals and relatively unaffected in DAGLβ−/− animals. Finally, we show that the control of adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus and subventricular zone is compromised in the DAGLα−/− and/or DAGLβ−/− mice. These findings provide the first evidence that DAGLα is the major biosynthetic enzyme for 2-AG in the nervous system and reveal an essential role for this enzyme in regulating retrograde synaptic plasticity and adult neurogenesis.

Introduction

Cannabis sativa has been used for thousands of years for both recreational and therapeutic purposes, with studies on the psychoactive component leading to the identification of two cannabinoid receptors (CB1 and CB2) that are currently being pursued as therapeutic targets (Mackie, 2006). Anandamide [N-arachidonoylethanolamine (AEA)] (Devane et al., 1992) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) (Sugiura et al., 2006) are the best characterized endogenous ligands for these receptors. Increasing anandamide levels by genetic ablation of the fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH), the enzyme that is responsible for hydrolyzing this lipid, is associated with activation of a number of CB1-dependent responses (Cravatt et al., 2001). Likewise, 2-AG is primarily hydrolyzed by monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL) (Dinh et al., 2002), and increasing 2-AG levels by use of a selective MAGL inhibitor also results in a broad array of CB1-dependent responses including analgesia and hypomotility (Long et al., 2009). Thus, both lipids can function as endocannabinoids (eCBs), at least in a pharmacological context. However, the physiological significance of these lipids as eCBs remains mostly correlative and, in the case of 2-AG, depends to a large extent on the use of pharmacological agents 1,6-bis(cyclohexyloximinocarbonylamino)hexane (RHC80267) and tetrahydrolipstatin that inhibit a number of brain hydrolases in addition to diacylglycerol lipase-α/β (DAGLα/β) (Hoover et al., 2008).

A full understanding of eCB signaling is important given its role in a wide range of processes including axonal growth and guidance during development (Williams et al., 2003; Berghuis et al., 2007; Watson et al., 2008), adult neurogenesis (Goncalves et al., 2008), and the many behavioral responses that are regulated by eCB retrograde signaling at synapses throughout the nervous system (Katona and Freund, 2008). Our knowledge of the mechanisms of synthesis of the eCBs, and the factors that govern whether the molecules primarily serve as direct signaling molecules as opposed to metabolic precursors for other lipids is incomplete. In the case of 2-AG, the primary route of synthesis is likely to be via hydrolysis of diacylglycerol (DAG) by one or other of two highly related sn-1-specific DAG lipases (DAGLα and DAGLβ) (Bisogno et al., 2003). These enzymes make a releasable pool of 2-AG in response to stimuli that activate eCB signaling (Bisogno et al., 2003; Jung et al., 2007) and are expressed at the right time and place to serve as a source of 2-AG to drive CB1-dependent axonal growth and guidance, adult neurogenesis, and synthesis of a retrograde synaptic messenger at CB1-positive synapses throughout the brain (Harkany et al., 2008). Nonetheless, the extent to which the enzymes make 2-AG and their individual involvement in eCB signaling remains to be tested. In the present study, we address these questions using a gene knock-out strategy for each enzyme.

Materials and Methods

Generation of DAGLα knock-out mice.

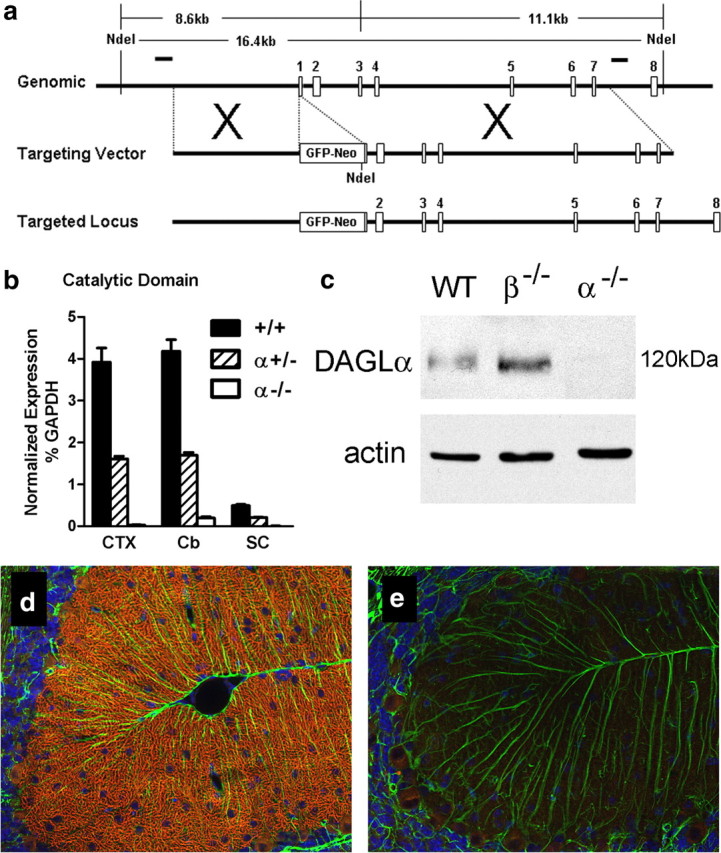

A targeting vector that deleted sequences of exon 1 and contained 4 kb of mouse genomic DNA 5′ of DAGLα (accession number NC_000011.8) exon 1 and 9.5 kb 3′ was constructed using the RedET recombineering system (Gene Bridges) following the manufacturer's protocol. This construct was electroporated into C57BL/6 embryonic stem (ES) cells and homologously targeted clones were selected and identified using standard procedures. Probes external to the targeting vector used to identify appropriately targeted clones were derived by PCR from mouse genomic DNA using the following primers: 5′ external probe; 5′-GAGCTCTGTTCAGGTGGTTCG; 5′-CTGGGCACCTTCTTTGATCC; 3′ external probe; 5′-GGAAATCACAGCTGGTAGCC; 5′-CTGCTCTTCAGGAACTCAGG. Both probes detect an endogenous band of 16.4 kb in NdeI cut ES cell genomic DNA and bands of 8.6 and 11.1 kb in targeted clones when probed with 5′ or 3′ external probes, respectively. Mouse lines were derived from targeted clones using standard procedures and maintained on a C57BL/6 background.

Generation of DAGLβ knock-out mice.

DAGLβ knock-out mice were generated from a Lexicon OmniBank ES cell clone OST195261 (Zambrowicz et al., 1998), which contains a gene trap cassette insertion in the first exon of DAGLβ (accession number NM_144915.2). Mice originally derived on a 129/SvEv background were backcrossed to C57BL/6 for six generations. Marker analysis was performed at the last generation and detected that >98% of 129 loci had been replaced in the mice.

TaqMan reverse transcription-PCR.

Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR was performed to detect both mouse DAGLα and DAGLβ mRNA on RNA samples extracted from multiple mouse tissues. Mouse total RNAs from Swiss Webster mice were acquired from Zyagen or isolated in house. All RNA samples were treated with DNase I to remove genomic DNA contamination. Integrity and quantity of RNA samples were assessed using microfluidics station 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis SuperMix kit (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer's protocol. Purified cDNA was quantified with Quant-iT OliGreen ssDNA reagent (Invitrogen) to ensure equal loading of cDNA per reaction. Quantitative PCRs were performed in an ABI Prism 7000 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). RNA from mouse tissues was isolated using RNeasy Fibrous Tissue mini-kit (QIAGEN), and cDNA synthesis was performed using WT-Ovation RNA Amplification System V2 (NuGEN Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Mouse DAGLα (NM_198114.2) gene-specific TaqMan assay (Applied Biosystems) was custom made targeting exons 14–15, which encode the catalytic domain. Predesigned TaqMan endogenous control glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was also purchased from Applied Biosystems. The TaqMan gene expression IDs for DAGLβ, MAGL, FAAH, CB1, and CB2 are Mm01201462_m1, Mm00449274_m1, Mm00515684_m1, Mm01212171_ s1, and Mm00438286_m1 (Applied Biosystems). Results were expressed as percentage of GAPDH mRNA.

Biochemical analysis.

For determining DAGL levels in wild-type (wt), DAGLα−/−, and DAGLβ−/− mice, cerebellum extracts were loaded onto a 12% NuPAGE Bis-Tris polyacrylamide gel (Invitrogen) under reducing condition, transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane, and probed with a rabbit anti-DAGLα (a gift from Prof. Masahiko Watanabe, Hokkaido University, Sapporo, Japan) or rabbit anti-DAGLβ antibodies (Bisogno et al., 2003) as previously described (Yoshida et al., 2006). Results were confirmed using at least two independent antibodies raised against different epitopes on each enzyme and, in the case of DAGLα, also by immunocytochemistry.

Measurement of 2-AG, arachidonic acid, and AEA.

Tissues were dissected from mice, immediately placed onto dry ice, and stored at −80°C. Frozen tissue was weighed and homogenized in same volume of 0.02% trifluoroacetic acid, pH 3.0, in a glass tissue grinder on ice. Four volumes of acetonitrile, 50 ng/ml [2H8]2-AG, and/or 5 ng/ml [2H8]AEA were added to the homogenate. Homogenization and extraction were further performed on ice. The homogenate was transferred to a siliconized glass tube and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was transferred to a fresh siliconized glass tube and evaporated to dryness under nitrogen. The dried extracts were reconstituted in acetonitrile by vortexing and stored at −80°C before use. On-line liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) analysis was conducted using a Waters Quatro Micro tandem quadruple mass spectrometer (Waters) with an Agilent high-performance liquid chromatograph (HP 1100; Hewlett Packard). Chromatographic separations were performed using a Chromolith RP-18E column (3.0 mm inner diameter, 100 mm length; Merck KGaA) at 40°C. The mobile phase consisted of solvent A [0.2% acetic acid in water–methanol (95:5, v/v)] and solvent B [0.2% acetic acid in water–methanol (5:95, v/v)]. The HPLC analysis was performed at a flow rate of ∼0.5 ml/min with a rapid gradient (40–90%) of solvent B for 2 min, and then held at 100% B for 7.5 min, 40% B for 0.5 min, and finally at 40% B for 4.5 min. The 0.5 ml/min effluent from the LC column was split before the MS and ∼0.2 ml/min effluent was directed into the mass spectrometer, which was operated in positive electrospray ionization mode and detected by multiple reactions monitoring scan mode. The concentrations of 2-AG and arachidonic acid (AA) were determined using [2H8]2-AG, and AEA using [2H8]AEA as internal standard, respectively.

Slice preparation and electrophysiology.

Two- to 3-week-old C57BL/6 mice were deeply anesthetized with halothane before decapitation. In all cases, the experimenter was blind to genotype. All procedures were performed in strict accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Wyeth Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Coronal 400 μm slices were cut using Leica VT 1200S vibratome in a sucrose-based ice-cold solution, transferred to carbogen-bubbled artificial CSF (ACSF) (in mm: 119 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 3 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.3 MgSO4, 10 glucose, bubbled with carbogen), and left to recover for at least for 1 h at room temperature until they were used. All recordings were made from CA1 pyramidal neurons in whole-cell voltage-clamp configuration at room temperature (23°C).The extracellular solution was ACSF supplemented with 1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-6-nitro-2,3-dioxo-benzo[f]quinoxaline-7-sulfonamide (NBQX) (5 μm)and 3-((R)-2-carboxypiperazine-4-yl)-propyl-1-phosphonic acid [(R)-CPP] (2 μm)to block AMPA and NMDA conductances. Brain slices were positioned at the bottom of the RC-26G chamber (Warner Instruments) and perfused with the extracellular solution at 1 ml/min. Pipette resistance was 2–4 MΩwhen filled with the intracellular solution [in mm: 80 CsCH3SO3, 60 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 1 Mg-ATP, 0.5 Na3-GTP, 0.2 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 5 N-(2,6-dimethylphenylcarbamoylmethyl)triethylammonium bromide (QX314), pH 7.3 with CsOH]. Junction potential was not compensated. IPSCs were evoked by 1 ms voltage pulses delivered through a 5- to 10-μm-diameter glass microelectrode (second electrode was the bath ground) filled with ACSF and positioned on the border of the striatum radiatum and the striatum pyramidale proximal to the voltage-clamped neuron. Recordings with >25% series resistance change were excluded from the analysis. Depolarization-induced suppression of inhibition (DSI)protocol was adopted from Wilson and Nicoll (2001): IPSCs were evoked at 0.33 Hz; DSI was performed every 120 s, was preceded by 20 control stimuli at Vh= −70 mV, was evoked by a 5 s depolarization from −70 to 0 mV, and was followed by 20 stimuli at Vh= −70 mV. DSI protocol was repeated four to five times for each neuron to obtain the mean values of evoked IPSC (eIPSC)amplitudes at the respective time points. DSI peak magnitude was calculated for each neuron using the mean value of eIPSC amplitude just before depolarization (n = −5 repeats) and the mean amplitude of the second eIPSC (n = −5 repeats) just after depolarization: DSI (%) = 100(1 − (Atest/Abaseline)). It is thus possible to obtain small negative values for DSI as a result, for example, of statistical noise (Wilson et al., 2001). Synaptic currents were filtered at 1–2 kHz while collected by a MultiClamp 700A amplifier and digitized at 5 kHz using DigiData 1322A and pClamp9 software (all from Molecular Devices). Baclofen was bath-applied after dilution into the external solution from 30 mmstock solution. NBQX, (R)-CPP, (RS)-baclofen, and QX314 were obtained from Tocris Bioscience. All other chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich.

Measurements of cell proliferation and immunohistochemistry.

Four intraperitoneal 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU) (100 mg/kg) (Sigma-Aldrich) injections were performed every 2 h in age-matched adult mice. Mice were killed 24 h after the last BrdU injection. BrdU-positive cells were counted in dissociated tissue or within sections. For the former, blocks of brain tissue containing subventricular zone (SVZ) and hippocampus were obtained, and SVZ and hippocampus regions dissected and processed for the quantification of cell proliferation by flow cytometry (Bilsland et al., 2006). In brief, tissues were minced with fine bowspring scissors and incubated in an enzymatic solution comprising 10 mg/ml l-cysteine (Sigma-Aldrich), 10% of papain (Roche), and 250 U/ml DNase (Roche) for 30 min at 37°C. Dissociated cells were then fixed, permeabilized, and labeled for BrdU following the instructions from the FITC BrdU flow kit (BD Biosciences). The cells were then stained with fluorescent nuclear dye 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) before analysis using the FACSVantage flow cytometry analysis system (BD Biosciences). Ten thousand 7-AAD-positive cells were collected, and the number of these cells expressing BrdU was examined. Data were collected from 10 wt, 5 DAGLα−/−, and 5 DAGLβ−/− mice. The second method involved standard counting of cells in tissue sections as previously described (Goncalves et al., 2008). In brief, sagittal sections (6 μm) containing the SVZ or the hippocampus were cut from formalin-fixed, paraffin wax-embedded tissues at similar bregma points in wt and DAGLα−/− animals. They were immunostained as above using antibodies to Ki-67 (SP6; Lab Vision Neomarkers; 1:100), BrdU (Dako; 1:100), or doublecortin (DCX) (Abcam; 1:100). Cell counts were obtained blindly from at least four sections per animal. Cells were counted under high power (40×) using an Apotome Zeiss microscope. The average number of labeled cells per section was determined for four wt animals and three knock-out animals. Immunohistochemistry for DAGLα expression in the cerebellum was performed on 6 μm sections of formalin-fixed, paraffin wax-embedded tissues as previously described (Bisogno et al., 2003). In brief, sections were dewaxed in xylene, then heated in citric acid (10 mm), pH 6, until boiling, and then washed under running tap for 5 min. Sections were then blocked with 1% BSA for 15 min, followed by overnight incubation at 4°C with the primary antibody, before incubation with the corresponding fluorescent secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa Flour 594; 1:1000; Invitrogen) and Hoechst 33342 to highlight nuclei (Sigma-Aldrich; 1:10,000). Primary antibodies used on paraffin wax sections were against DAGLα (Bisogno et al., 2003) and GFAP (a mouse monoclonal antibody from Sigma-Aldrich; G-3893).

Results

Generation of DAGL knock-out mice

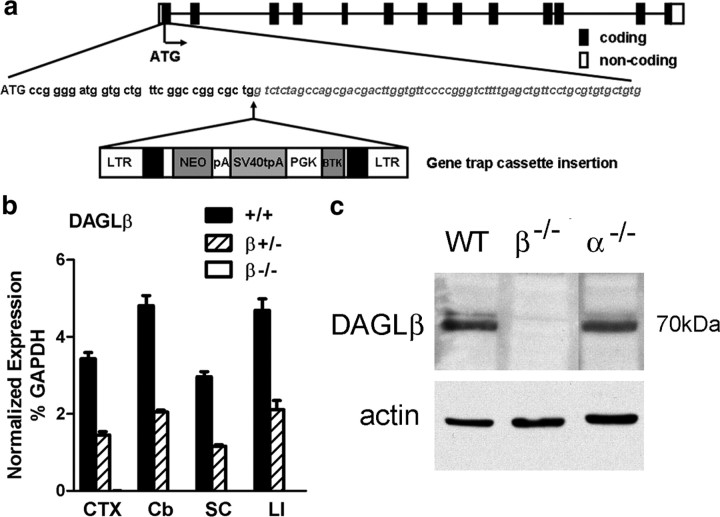

Mice lacking DAGLα were generated through standard gene targeting (see Materials and Methods) (Fig. 1a). Loss of DAGLα transcripts was confirmed by TaqMan assay using probes against exons 14–15, which encode the catalytic domain (Fig. 1b), and probes against exon 19, which encodes the C-terminal part of the enzyme (data not shown). Loss of DAGLα protein expression was confirmed initially by Western blotting against adult cerebellum (Fig. 1c), with similar loss of expression confirmed by Western blotting against whole adult brain and hippocampus (data not shown). Within the whole brain, DAGLα expression is perhaps most obvious in Purkinje cells dendrites (Bisogno et al., 2003), with this staining lost in the DAGLα−/− mice (Fig. 1d,e). Likewise, staining is also lost from the dendritic fields of the hippocampus and all other brain areas including the SVZ (data not shown). Mice lacking DAGLβ were obtained from a library generated using a random gene trapping strategy in ES cells (Zambrowicz et al., 1998) (Lexicon Omnibank clone OST195261) (Fig. 2a). Again, we could not detect DAGLβ transcripts or protein in the DAGLβ−/− mice (Fig. 2b,c). Thus, we have clearly generated a mouse line that no longer expresses DAGLα and identified a mouse line that no longer expresses DAGLβ.

Figure 1.

Generation and validation of DAGLα−/− mice. a, Targeting strategy for DAGLα: genomic structure of the mouse DAGLα gene up to exon 8. Targeting vector replaces a portion of exon 1 with a selection cassette. Homologous integration is detected by Southern blotting using probes external to the targeting vector on both the 5′ and 3′ sides. Probes are indicated as solid lines above the genomic locus. Both probes detect an endogenous band of 16.4 kb in NdeI-cut genomic DNA. Homologous targeting creates bands of 8.6 and 11.1 kb when probed with 5′ or 3′ external probes, respectively. b, TaqMan analysis for DAGLα mRNA levels in cortex (CTX), cerebellum (Cb), and spinal cord (SC) from wt (+/+), DAGLα+/− (+/−), and DAGLα−/− (−/−) mice (n = 3–5/genotype). DAGLα expression is normalized as the percentage of GAPDH levels. Error bars indicate SEM. c, Western blot analysis of cerebellum tissues from wt (WT), DAGLα−/− (α−/−), and DAGLβ−/− (β−/−) mice demonstrates the absence of DAGLα protein in DAGLα−/− mice. Expression of actin in each sample is used as a loading control. In d, DAGLα expression is restricted to Purkinje cell dendrites in the cerebellum of adult wt mice (the red staining), with this staining lost in DAGLα−/− mice (e). Normal staining of GFAP, to highlight Bergman glial cells, was found in the wt and DAGLα−/− mice (the green staining in d and e). The sections were counterstained to show cell nuclei (in blue).

Figure 2.

Generation and validation of DAGLβ−/− mice. a, DAGLβ knock-out mice were generated from a Lexicon OmniBank ES cell clone OST195261, which contains a gene trap cassette insertion in the first exon of the mouse DAGLβ gene. LTR, Long terminal repeat; NEO, neomycin gene; pA, polyadenylation sequence; SV40tpA, SV40 triple polyadenylation sequence; PGK, phosphoglycerate kinase-1 promoter; BTK, Bruton tyrosine kinase. b, TaqMan analysis for DAGLβ mRNA levels in the cortex (CTX), cerebellum (Cb), spinal cord (SC), and liver (LI) from wt (+/+), DAGLβ+/− (+/−), and DAGLβ−/− (−/−) mice (n = 4/genotype). DAGLβ expression is normalized as the percentage of GAPDH levels. Error bars indicate SEM. c, Western blot analysis of cerebellum tissues from wt (WT), DAGLα−/− (α−/−), and DAGLβ−/− (β−/−) mice demonstrates the absence of DAGLβ protein in DAGLβ−/− mice.

DAGLα−/− and DAGLβ−/− mice are viable, fertile, and mostly indistinguishable from wt littermates. They showed no deficits in tests monitoring locomotion, ataxia, catalepsy, and acute thermal nociception compared with wt mice (data not shown). However, for 9- to 11-week-old animals, the mean body weights of male and female DAGLα−/− mice are 23.4 and 12.7% less than their wt littermates (both values of p < 0.01), and future studies will address whether this is attributable to a decrease in appetite and food intake or an increase in energy consumption. DAGLβ−/− mice showed only a slight and insignificant decrease (<10%) in body weight.

DAGLα mRNA expression was not significantly altered in the DAGLβ−/− mice and vice versa, and transcript levels of other genes associated with the eCB system such as MAGL, FAAH, and the CB1 and CB2 receptors remained mostly unchanged in the DAGLα and DAGLβ knock-out mice (supplemental Fig. 1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). Likewise, DAGLα protein levels in the cerebellum were not obviously different in the DAGLβ−/− mice and vice versa (Figs. 1c, 2c), and we also found no difference in MAGL protein levels, or in the density and presynaptic location of CB1 receptors in the cerebellum in any of the knock-out mice (data not shown).

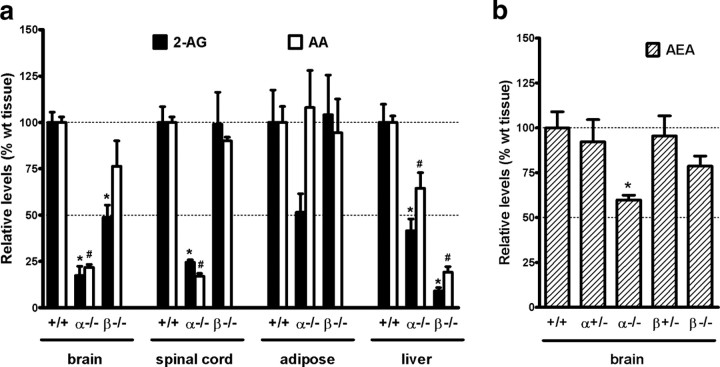

2-AG and AA levels are reduced by up to 80% in brain and spinal cord of DAGLα−/− mice

DAGLα is known to be particularly enriched in the adult brain and spinal cord (Bisogno et al., 2003), and here we find up to an 80% reduction in 2-AG levels in mice lacking this enzyme (Fig. 3a). In contrast, there was a 50% reduction in 2-AG levels in the brain and no significant difference in 2-AG levels in the spinal cord in the DAGLβ−/− mice, suggesting that this enzyme also plays a major, but perhaps secondary, role in 2-AG synthesis in the CNS and/or loss of its function is compensated by DAGLα. DAGLα is also expressed in adipose tissue and in liver but is not enriched over DAGLβ in these tissues (supplemental Fig. 2, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). In these tissues, loss of DAGLα is associated with a ∼60% reduction in 2-AG in the liver, and a ∼50% reduction in adipose tissue, but the latter did not reach significance (Fig. 3a). Loss of DAGLβ had no impact on 2-AG levels in adipose tissue, but there was a ∼90% reduction in 2-AG levels in the liver of DAGLβ−/− mice (Fig. 3a). Thus, the DAGLs are responsible for maintaining steady-state levels of 2-AG in various tissues, and importantly their individual contribution is different depending on the tissue.

Figure 3.

2-AG, AA, and AEA levels in wt, DAGLα−/−, and DAGLβ−/− tissues. a, Levels of 2-AG and AA in brain, spinal cord, adipose, and liver from wt (+/+), DAGLα−/− (α−/−), and DAGLβ−/− (β−/−) mice (n = 4–13/genotype). Results are expressed as relative levels normalized to the same type of wt tissue. *,#p < 0.01, 2-AG, AA levels to the same type of wt tissue, t test. The levels of 2-AG (in nanomoles per gram) in wt tissues are 11.3 ± 1.0 in brain, 6.6 ± 1.0 in spinal cord, 0.5 ± 0.1 in adipose, and 4.6 ± 0.5 in liver. The levels of AA (in nanomoles per gram) in wt tissues are 93.3 ± 4.7 in brain, 57.7 ± 1.8 in spinal cord, 8.6 ± 0.7 in adipose, and 25.3 ± 2.2 in liver. b, Levels of AEA in the brain of wt (+/+) mice compared with mice with one (+/−) or zero (−/−) copies of the normal DAGLα/β locus (n = 3–8/genotype). Results are expressed as relative levels normalized to wt brain. *p < 0.01, to wt brain, t test. The levels of AEA (in picomoles per gram) in wt brain are 22.0 ± 2.1. Error bars indicate SEM.

We found a 40% decrease of AEA, the other major eCB in the brain, in the DAGLα−/− brain compared with wt, and a 20% reduction in the DAGLβ−/− mice that did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 3b). 2-AG and AEA can be hydrolyzed to AA by MAGL and FAAH, respectively. Interestingly, levels of AA change in parallel with the changes in 2-AG in the brain, spinal cord, and liver (Fig. 3a). Notably, there were ∼80% reductions in AA levels in the brain and spinal cord in the DAGLα−/− mice, with a ∼90% reduction in the liver in the DAGLβ−/− mice.

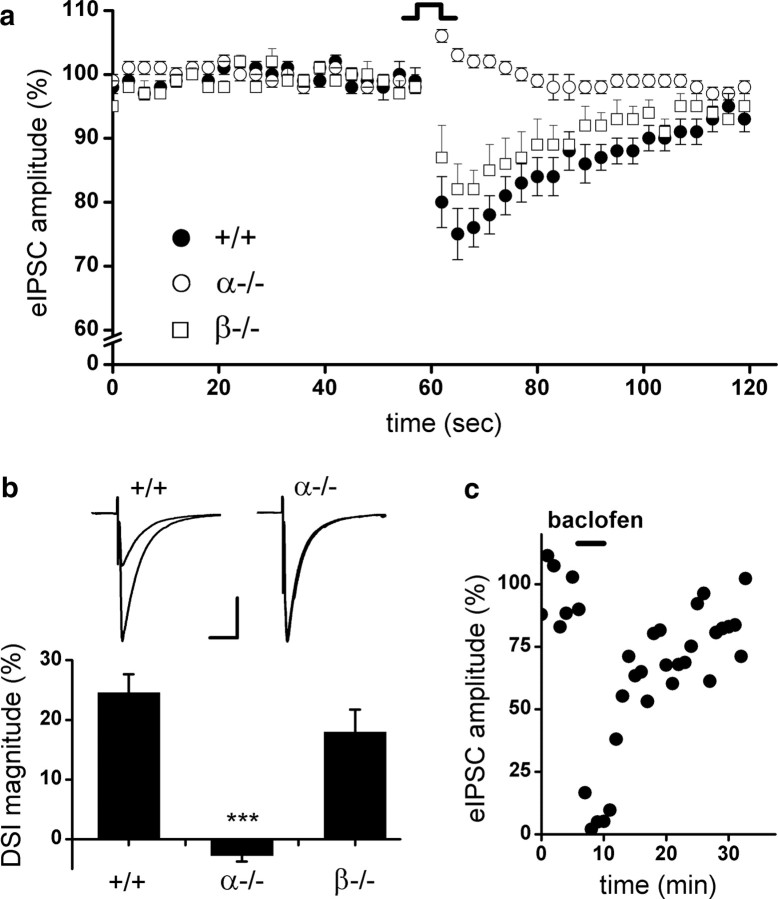

Retrograde eCB signaling in the hippocampus is lost in mice lacking DAGLα

DAGLα and DAGLβ transcripts are readily detectable in the adult hippocampus (supplemental Fig. 2, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material), with DAGLα expression localized to dendritic spines (Yoshida et al., 2006). DSI is one of the best characterized forms of short-term synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus (Wilson and Nicoll, 2001). In the present study, we monitored eIPSCs by whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings from hippocampal slices. We assessed DSI by recording four to nine CA1 pyramidal neurons per mouse and averaging four to five DSI protocol repeats per cell. Figure 4a shows the transient depression of eIPSCs caused by a 5 s depolarizing step of CA1 pyramidal neurons from wt animals (35 neurons from six mice) in a 2 min time course. Consistent with literature that only a subpopulation of interneurons expresses CB1 and ∼60% of cells are susceptible to DSI in the CA1 area (Wilson et al., 2001), we found that 21 of 35 (60%) wt neurons elicited depression of eIPSCs in response to depolarization. In contrast, DSI is entirely absent in CA1 neurons (21 neurons from three mice) from mice lacking DAGLα, with no cells exhibiting suppression of eIPSCs after depolarization (Fig. 4a). The magnitudes of DSI are also expressed as a percentage of depression in eIPSC amplitude comparing the baseline eIPSCs before depolarization and the respective eIPSCs after depolarization. Average peak DSI magnitude in wt mice is 24.6 ± 3.1% (including both DSI-positive and DSI-negative neurons), whereas a slight increase of eIPSC amplitude post depolarization was observed in DAGLα−/− showing an average DSI magnitude of −2.3 ± 1.0% (Fig. 4b). In contrast to the results obtained with the DAGLα knock-out animals, 57% of DAGLβ−/− neurons (21 neurons from three mice) are susceptible to DSI, and loss of DAGLβ resulted in only a small and insignificant reduction in the DSI response (Fig. 4a,b). In addition, baclofen, a GABAB receptor agonist could still induce depression of eIPSCs in DAGLα−/− neurons (mean ± SEM, 88 ± 7%; n = 3) (Fig. 4c), indicating that other components of presynaptic inhibition, such as presynaptic inhibition by GABAB receptor, are intact in these animals.

Figure 4.

DSI in the hippocampus of wt, DAGLα−/−, and DAGLβ−/− mice. a, DSI is absent in DAGLα−/− mice. Average time course for eIPSC amplitudes after depolarization in wt (+/+), DAGLα−/− (α−/−), and DAGLβ−/− (β−/−) mice. DSI for each genotype is averaged across all cells sampled, four to five DSI protocol repeats per sampled cell (+/+, n = 35; α−/−, n = 21; β−/−, n = 21). b, Peak DSI value is expressed as a percentage of depression in eIPSC amplitude after depolarization. Insets are representative recordings from a single CA1 neuron in wt (+/+), DAGLα−/− (α−/−), and DAGLβ−/− (β−/−) mice: the average of eIPSC traces (n = 4–5) just before DSI versus the average of eIPSC traces at the peak of DSI (second trace after 5 s depolarization; n = 4–5). Scale bar, 50 ms, 400 pA. *** p < .001, one-way ANOVA. Error bars indicate SEM. c, (RS)-Baclofen (10 μm) displays a robust inhibition of eIPSC in DAGLα−/− mice, as indicating here the eIPSC recordings of a single CA1 neuron in a representative experiment; each point represents the average of six eIPSCs.

Adult neurogenesis is compromised in the SVZ in mice lacking DAGLα

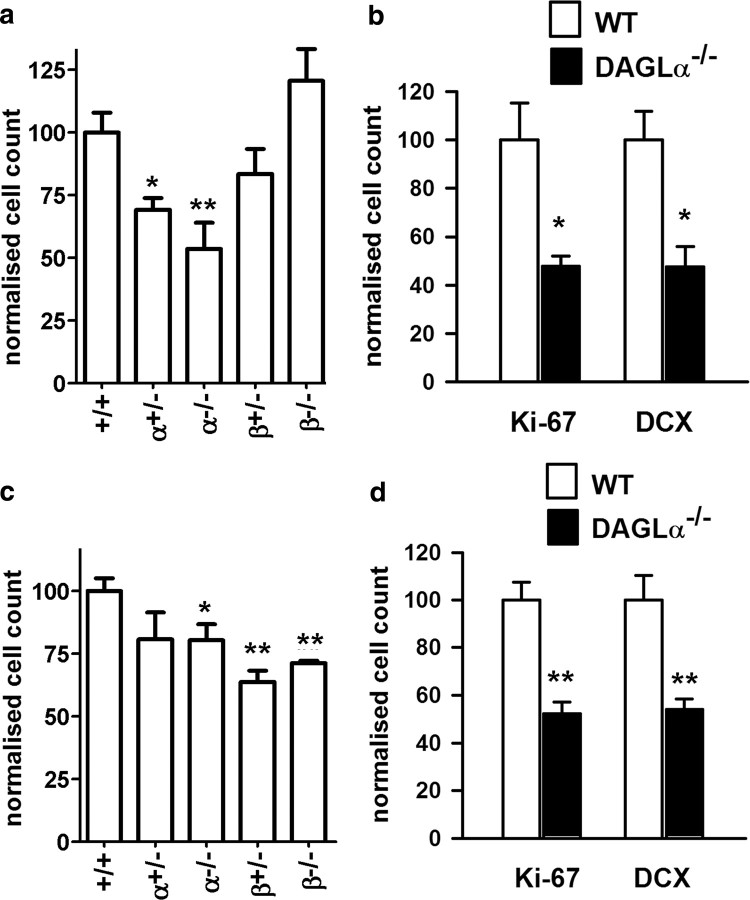

Adult neurogenesis is restricted to the lateral wall of the SVZ (Alvarez-Buylla and Garcia-Verdugo, 2002) and the granule cell layer in the dentate gyrus (DG) in the hippocampus (van Praag et al., 2002). Pharmacological evidence supports a role for a DAGL in neurogenesis (Goncalves et al., 2008), but the drugs are not specific and cannot discriminate between DAGLα and DAGLβ. BrdU can be used to label proliferating cells within the lateral ventricle, and the SVZ can subsequently be dissected out and BrdU cells counted by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis as a percentage of the total population (for details, see Materials and Methods). Analysis of samples obtained from young adult mice (7–10 weeks of age) showed significant reductions in proliferation in mice that lacked a single or both copies of the DAGLα gene, with this reaching a ∼50% reduction in the latter (Fig. 5a). In contrast, cell proliferation in the SVZ was not significantly altered in mice lacking DAGLβ (Fig. 5a).

Figure 5.

DAGLα regulates neurogenesis in the hippocampus and SVZ. The relative levels of cell proliferation as indexed by the number of BrdU-positive cells present in the SVZ (a) or hippocampus (c) is shown for wt (+/+) mice compared with mice with one (+/−) or zero (−/−) copies of the normal DAGLα/β locus. Counts of Ki-67 and DCX in the SVZ (b) and DG in the hippocampus (d) in wt and DAGLα−/− mice. Results are normalized to control, and bars show SEM. **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 (two-sided Student's t test). Mice are 7–10 weeks of age.

We also determined the degree of neurogenesis in wt and DAGL knock-out mice by staining representative sagittal sections sampled throughout the SVZ from independent cohorts of mice. These studies confirmed the significant reductions in the number of BrdU-positive cell in the DAGLα mice, with no changes seen in the DAGLβ mice (data not shown). We repeated the studies using the Ki-67 antigen as an independent marker for proliferating cells (Kee et al., 2002). Using this marker, we found a 52% reduction (p = 0.03) in cell proliferation in the DAGLα−/− mice (Fig. 5b). Again, there was no effect in DAGLβ−/− mice (data not shown). Previous studies have shown that approximately one-half of the proliferating cells in the SVZ express DCX, a marker for neuroblasts (Goncalves et al., 2008). In the present study, we also found a 50% reduction (p < 0.02) in DCX-positive cells in the SVZ of the DAGLα−/− mice (Fig. 5b).

Adult neurogenesis is compromised in the hippocampus in mice lacking DAGLα or DAGLβ

The second neurogenic niche in the adult brain is within the DG in the hippocampus. The role of the DAGLs in hippocampal neurogenesis has not as yet been explored. Using BrdU labeling, and analyzing the whole hippocampus by FACS analysis, we find a significant (p < 0.05) 20% reduction in cell proliferation in the DAGLα−/− mice (Fig. 5c). Interestingly, and in contrast to the SVZ, we also find significant decreases in cell proliferation in the DAGLβ+/− and DAGLβ−/− mice (Fig. 5c). Given the fact that DAGLα is required for proliferation in the SVZ and hippocampus, we conducted additional studies in the hippocampus of the DAGLα−/− mice. Cell counts within the DG in representative sagittal sections sampled throughout the hippocampus revealed a highly significant reduction in Ki-67-positive cells to ∼50% of the value seen in wt animals (Fig. 5c). Likewise, there was a highly significant ∼50% reduction in the number of DCX-positive cells in the sagittal sections (Fig. 5d). Thus, it is clear that DAGLα is required for neurogenesis in both the adult SVZ and hippocampus.

Discussion

We have generated the first mouse lines with targeted disruptions in the gene loci encoding DAGLα or DAGLβ. In both cases, a null phenotype was confirmed by TaqMan analysis of transcripts and by Western blotting. In the case of DAGLα, antibodies that intensely label dendritic layers in the brain fail to label the same structures in the DAGLα−/− mice, confirming the specificity of the antibodies. In the case of DAGLβ, we have tested four independent antibodies raised against different epitopes; however, although some of these can specifically pick up DAGLβ on Western blots, we have been unable to validate any of them for use in immunohistochemistry (data not shown).

Importantly, we find no major changes in the transcript levels for MAGL, FAAH, and CB1 or CB2 receptor in the DAGLα−/− or DAGLβ−/− mice. Where tested, this was confirmed at the protein level (MAGL and CB1). Also, we found no evidence for loss of DAGLα affecting the levels of DAGLβ transcripts or protein and vice versa. Overall, the data suggest that any phenotype will be directly attributable to the loss of DAGLα or DAGLβ, and not deregulated expression of another eCB pathway molecule.

DAGLα and DAGLβ both contribute substantially to the regulation of steady-state levels of 2-AG in the brain and other tissues. The most surprising finding is the magnitude of loss of 2-AG in mice lacking a single DAGL. For example, 2-AG levels are reduced by up to 80% in the brain and spinal cord of the DAGLα−/− and by up to 50% in the brain in the DAGLβ−/− mice. There is an emerging hypothesis that a second essential lipid, AA, might also be highly regulated by DAGL activity. In this context, AA is highly enriched in the brain and is the substrate for a number of enzymes that generate a range of eicosanoids that play an essential role in both health and disease. Cytosolic phospolipase A2 releases AA from the sn-2 position of phospholipids, and this is thought by many to be the primary pathway for regulating AA levels (Rapoport, 2008). However, pharmacological inhibition of MAGL is associated with substantial decreases in AA levels in the brain (Long et al., 2009). The results of the present study show highly correlated decreases in 2-AG and AA levels in the DAGL knock-out mice. These data clearly support the hypothesis that a DAGL–MAGL signaling axis is responsible for maintaining steady-state levels of AA in the brain and other tissues. Reductions in 2-AG levels and/or AA might also impact on a number of other signaling lipids. For example, in the case of 2-AG, lipoxygenase enzymes have been shown to oxygenate 2-AG to provide the precursor for leukotrienes (Sugiura et al., 2002) and cyclooxygenase-2 can convert 2-AG to glycerol prostaglandins (Kozak et al., 2000). 2-AG, AA, and AEA are substrates or products for the same or related enzymes, and on this basis it is perhaps not surprising that major changes in 2-AG and AA levels can impact on the level of AEA, which is reduced ∼40% in the brain of the DAGLα−/− mice.

Having generated the DAGL knock-out mice, it becomes possible to ask specific questions regarding the requirement of each enzyme for well established or emerging eCB functions. DSI in the hippocampus is a well established eCB function and one of the best characterized forms of short-term synaptic plasticity. Here, postsynaptic depolarization leads to release of an eCB that activates presynaptic CB1 receptors and transiently suppresses the release of GABA (Ohno-Shosaku et al., 2001; Wilson and Nicoll, 2001). The same eCB feedback mechanism operates at both inhibitory and excitatory synapses, with a depolarization-induced suppression of excitation (DSE) seen at the latter (Kreitzer and Regehr, 2001). Pharmacological studies support the view that DAGL activity is required for DSI/DSE, but the same results are not always found with tetrahydrolipstatin and RHC80267 (Hashimotodani et al., 2008), and these are not selective inhibitors (Hoover et al., 2008). Our results show that DSI is completely absent from DAGLα−/− mice and relatively unaffected in DAGLβ−/− mice. Thus, we have provided the first genetic evidence in support of DAGLα regulating hippocampal DSI and demonstrated the first unequivocal difference in the function of DAGLα and DAGLβ.

There is an emerging role for eCB signaling in the regulation of neurogenesis (Aguado et al., 2005; Jiang et al., 2005; Palazuelos et al., 2006; Molina-Holgado et al., 2007). In the adult brain, this is restricted to the lateral wall of the SVZ (Alvarez-Buylla and Garcia-Verdugo, 2002) and the granule cell layer in the DG in the hippocampus (van Praag et al., 2002). SVZ neuroblasts migrate along the rostral migratory stream to populate the olfactory bulb with new neurons, whereas in the hippocampus the neuroblasts show limited migration and differentiate into mature neurons within the DG. Adult neurogenesis is of additional interest in that it is also modulated in psychiatric disorders and neurodegenerative disease states and can act as a source of new neurons that can migrate to sites of injury (Curtis et al., 2007).

A role for DAGLα in SVZ neurogenesis was postulated based on its restricted expression to ependymal cells and proliferating cells in the lateral wall of the ventricle, and this was supported by the observation that tetrahydrolipstatin and/or RHC80267 can reduce cell proliferation in the SVZ, and the appearance of new neurons in the olfactory bulb of young adult animals (Goncalves et al., 2008). In the present study, we report a very similar ∼50% reduction in neurogenesis (as determined by BrdU labeling, expression of the Ki-67 antigen, or expression of the neuroblast marker DCX) in the SVZ in DAGLα−/− mice. Interestingly, loss of a single copy of DAGLα had a significant impact on neurogenesis, supporting the suggestion that a rundown of eCB tone might underlie the age-dependent decline in adult neurogenesis (Goncalves et al., 2008). Importantly, loss of DAGLβ had no impact on neurogenesis in this region of the brain. Similar responses are seen with CB2, but not CB1 antagonists (Goncalves et al., 2008). Overall, these data support the emerging hypothesis that the eCB system maintains adult neurogenesis in the SVZ and provide the first evidence that DAGLα, and not DAGLβ, is regulating the eCB levels driving this response.

The second neurogenic niche in the adult brain is within the DG in the hippocampus, and here neurogenesis might be important for some hippocampal-dependent learning tasks, such as spatial learning in the Morris water maze test (Zhang et al., 2008). It has been estimated that as many as 250,000 newborn neurons are produced in the DG of young adult rodents each month, constituting some 6% of the total cell volume (Cameron and McKay, 2001). Inhibiting or activating CB1 receptors results in 20–30% changes in proliferation rates (Jiang et al., 2005). The present study is the first to address the test whether DAGL activity is required for hippocampal neurogenesis. Our results show up to a 50% reduction in Ki-67 and DCX-positive cells in the DG of the hippocampus in DAGLα−/− mice, providing direct evidence that this enzyme is required for adult neurogenesis throughout the brain. Interestingly, and in contrast to the situation in the SVZ, DAGLβ is also required for cell proliferation in the hippocampus with a ∼30–40% reduction in BrdU-positive cells found in the hippocampus of mice lacking one or two functional gene loci for this enzyme.

In summary, we have generated DAGLα−/− and DAGLβ−/− mice. Animals lacking one of these enzymes are viable, fertile, and display normal physiological behaviors in tests measuring locomotion, ataxia, catalepsy, and thermal nociception. Levels of 2-AG are reduced by up to 80% in the brain and spinal cord, and by ∼90% in the liver in mice lacking DAGLα and DAGLβ, respectively. Interestingly, the reductions in 2-AG levels were accompanied by similar percentage reductions in AA levels, supporting an emerging viewpoint that a DAGL/MAGL pathway might be responsible for the synthesis of a large fraction of AA in the brain. In the hippocampus, the postsynaptic release of an eCB induced by depolarization results in the transient suppression of GABA-mediated transmission at inhibitory synapses; we now show that this form of DSI is completely lost in DAGLα knock-out animals. Finally, we show that adult neurogenesis is compromised in both the hippocampus and SVZ in DAGLα knock-out mice, but only in the hippocampus in DAGLβ knock-out mice.

Footnotes

The work in the Doherty Laboratory was supported by a research grant from Wyeth Research and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council. We thank Shannon O'Brien and Dr. Theodore Simon for breeding of the DAGL mice, Dr. Edward Kaftan for assistance in conducting the blind electrophysiology experiments, and Andrew Randall and Ben Cravatt for critical comments on this manuscript. We thank Dr. Watanabe for guinea pig, rabbit, and goat antibodies to DAGLα.

References

- Aguado T, Monory K, Palazuelos J, Stella N, Cravatt B, Lutz B, Marsicano G, Kokaia Z, Guzmán M, Galve-Roperh I. The endocannabinoid system drives neural progenitor proliferation. FASEB J. 2005;19:1704–1706. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3995fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Buylla A, Garcia-Verdugo JM. Neurogenesis in adult subventricular zone. J Neurosci. 2002;22:629–634. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-00629.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berghuis P, Rajnicek AM, Morozov YM, Ross RA, Mulder J, Urbán GM, Monory K, Marsicano G, Matteoli M, Canty A, Irving AJ, Katona I, Yanagawa Y, Rakic P, Lutz B, Mackie K, Harkany T. Hardwiring the brain: endocannabinoids shape neuronal connectivity. Science. 2007;316:1212–1216. doi: 10.1126/science.1137406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilsland JG, Haldon C, Goddard J, Oliver K, Murray F, Wheeldon A, Cumberbatch J, McAllister G, Munoz-Sanjuan I. A rapid method for the quantification of mouse hippocampal neurogenesis in vivo by flow cytometry. Validation with conventional and enhanced immunohistochemical methods. J Neurosci Methods. 2006;157:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisogno T, Howell F, Williams G, Minassi A, Cascio MG, Ligresti A, Matias I, Schiano-Moriello A, Paul P, Williams EJ, Gangadharan U, Hobbs C, Di Marzo V, Doherty P. Cloning of the first sn1-DAG lipases points to the spatial and temporal regulation of endocannabinoid signaling in the brain. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:463–468. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200305129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron HA, McKay RD. Adult neurogenesis produces a large pool of new granule cells in the dentate gyrus. J Comp Neurol. 2001;435:406–417. doi: 10.1002/cne.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cravatt BF, Demarest K, Patricelli MP, Bracey MH, Giang DK, Martin BR, Lichtman AH. Supersensitivity to anandamide and enhanced endogenous cannabinoid signaling in mice lacking fatty acid amide hydrolase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:9371–9376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161191698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MA, Faull RL, Eriksson PS. The effect of neurodegenerative diseases on the subventricular zone. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:712–723. doi: 10.1038/nrn2216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devane WA, Hanus L, Breuer A, Pertwee RG, Stevenson LA, Griffin G, Gibson D, Mandelbaum A, Etinger A, Mechoulam R. Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor. Science. 1992;258:1946–1949. doi: 10.1126/science.1470919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinh TP, Carpenter D, Leslie FM, Freund TF, Katona I, Sensi SL, Kathuria S, Piomelli D. Brain monoglyceride lipase participating in endocannabinoid inactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:10819–10824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152334899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves MB, Suetterlin P, Yip P, Molina-Holgado F, Walker DJ, Oudin MJ, Zentar MP, Pollard S, Yáñez-Muñoz RJ, Williams G, Walsh FS, Pangalos MN, Doherty P. A diacylglycerol lipase-CB2 cannabinoid pathway regulates adult subventricular zone neurogenesis in an age-dependent manner. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2008;38:526–536. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkany T, Mackie K, Doherty P. Wiring and firing neuronal networks: endocannabinoids take center stage. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2008;18:338–345. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimotodani Y, Ohno-Shosaku T, Maejima T, Fukami K, Kano M. Pharmacological evidence for the involvement of diacylglycerol lipase in depolarization-induced endocanabinoid release. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54:58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover HS, Blankman JL, Niessen S, Cravatt BF. Selectivity of inhibitors of endocannabinoid biosynthesis evaluated by activity-based protein profiling. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:5838–5841. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.06.091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W, Zhang Y, Xiao L, Van Cleemput J, Ji SP, Bai G, Zhang X. Cannabinoids promote embryonic and adult hippocampus neurogenesis and produce anxiolytic- and antidepressant-like effects. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3104–3116. doi: 10.1172/JCI25509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung KM, Astarita G, Zhu C, Wallace M, Mackie K, Piomelli D. A key role for diacylglycerol lipase-alpha in metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent endocannabinoid mobilization. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:612–621. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.037796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katona I, Freund TF. Endocannabinoid signaling as a synaptic circuit breaker in neurological disease. Nat Med. 2008;14:923–930. doi: 10.1038/nm.f.1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kee N, Sivalingam S, Boonstra R, Wojtowicz JM. The utility of Ki-67 and BrdU as proliferative markers of adult neurogenesis. J Neurosci Methods. 2002;115:97–105. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak KR, Rowlinson SW, Marnett LJ. Oxygenation of the endocannabinoid, 2-arachidonylglycerol, to glyceryl prostaglandins by cyclooxygenase-2. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33744–33749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007088200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreitzer AC, Regehr WG. Retrograde inhibition of presynaptic calcium influx by endogenous cannabinoids at excitatory synapses onto Purkinje cells. Neuron. 2001;29:717–727. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00246-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long JZ, Li W, Booker L, Burston JJ, Kinsey SG, Schlosburg JE, Pavón FJ, Serrano AM, Selley DE, Parsons LH, Lichtman AH, Cravatt BF. Selective blockade of 2-arachidonoylglycerol hydrolysis produces cannabinoid behavioral effects. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:37–44. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie K. Cannabinoid receptors as therapeutic targets. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2006;46:101–122. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.46.120604.141254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Holgado F, Rubio-Araiz A, García-Ovejero D, Williams RJ, Moore JD, Arévalo-Martín A, Gómez-Torres O, Molina-Holgado E. CB2 cannabinoid receptors promote mouse neural stem cell proliferation. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:629–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno-Shosaku T, Maejima T, Kano M. Endogenous cannabinoids mediate retrograde signals from depolarized postsynaptic neurons to presynaptic terminals. Neuron. 2001;29:729–738. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00247-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palazuelos J, Aguado T, Egia A, Mechoulam R, Guzmán M, Galve-Roperh I. Non-psychoactive CB2 cannabinoid agonists stimulate neural progenitor proliferation. FASEB J. 2006;20:2405–2407. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6164fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport SI. Arachidonic acid and the brain. J Nutr. 2008;138:2515–2520. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.12.2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura T, Kobayashi Y, Oka S, Waku K. Biosynthesis and degradation of anandamide and 2-arachidonoylglycerol and their possible physiological significance. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2002;66:173–192. doi: 10.1054/plef.2001.0356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura T, Kishimoto S, Oka S, Gokoh M. Biochemistry, pharmacology and physiology of 2-arachidonoylglycerol, an endogenous cannabinoid receptor ligand. Prog Lipid Res. 2006;45:405–446. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Praag H, Schinder AF, Christie BR, Toni N, Palmer TD, Gage FH. Functional neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus. Nature. 2002;415:1030–1034. doi: 10.1038/4151030a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson S, Chambers D, Hobbs C, Doherty P, Graham A. The endocannabinoid receptor, CB1, is required for normal axonal growth and fasciculation. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2008;38:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams EJ, Walsh FS, Doherty P. The FGF receptor uses the endocannabinoid signaling system to couple to an axonal growth response. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:481–486. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200210164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RI, Nicoll RA. Endogenous cannabinoids mediate retrograde signalling at hippocampal synapses. Nature. 2001;410:588–592. doi: 10.1038/35069076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RI, Kunos G, Nicoll RA. Presynaptic specificity of endocannabinoid signaling in the hippocampus. Neuron. 2001;31:453–462. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00372-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T, Fukaya M, Uchigashima M, Miura E, Kamiya H, Kano M, Watanabe M. Localization of diacylglycerol lipase-α around postsynaptic spine suggests close proximity between production site of an endocannabinoid, 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol, and presynaptic cannabinoid CB1 receptor. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4740–4751. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0054-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zambrowicz BP, Friedrich GA, Buxton EC, Lilleberg SL, Person C, Sands AT. Disruption and sequence identification of 2,000 genes in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nature. 1998;392:608–611. doi: 10.1038/33423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang CL, Zou Y, He W, Gage FH, Evans RM. A role for adult TLX-positive neural stem cells in learning and behaviour. Nature. 2008;451:1004–1007. doi: 10.1038/nature06562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]