Abstract

Cardiac remodeling is a self-regulatory response of the myocardium and vasculature under the stressful condition. Cardiomyocytes (CMs), vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), endothelial cells (ECs), and cardiac fibroblasts (CFs) are all involved in this process, characterized by change of morphological structures and mechanical/chemical activities as well as metabolic patterns. Despite current development of consciousness, the control of cardiac remodeling remains unsatisfactory, and to further explore the underlying mechanism and seek the optimal therapeutic targets is still the urgent need in clinical practice. It is now emerging that long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) play key regulatory roles in these adverse responses: lncRNA TUG1, AK098656, TRPV1, GAS5, Giver, and Lnc-Ang362 have been indicated in hypertension-related vascular remodeling, H19, TUG1, UCA1, MEG3, APPAT, and lincRNA-p21 in atherosclerosis (AS), and HIF1A-AS1 and Lnc-HLTF-5 in aortic aneurysm (AA). In addition, Neat1, AK139328, APF, CAIF, AK088388, CARL, MALAT1, HOTAIR, XIST, and NRF are involved in postischemia myocardial remodeling, while Mhrt, Chast, CHRF, ROR, H19, Plscr4, and MIAT are involved in myocardial hypertrophy, and MALAT1, wisper, MEG3, and H19 are involved in extracellular matrix (ECM) reconstitution. Signaling to specific miRNAs by acting as endogenous sponge (ceRNA) was the main form that regulates the target gene expression during cardiac remodeling. This review will underline the updates of lncRNAs and lncRNA-miRNA interactions in maladaptive remodeling and also cast light on their potential roles as therapeutic targets, hoping to provide supportive background for following research.

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases, especially coronary heart disease (CHD) and heart failure (HF), remain the leading cause of mortality worldwide, despite a dramatic reduction due to current therapeutic advances [1, 2]. Generally, acute ischemic events can be rapidly improved by timely revascularization, while progressive cardiac remodeling is becoming the new clinical puzzle. Cardiac remodeling, which mainly refers to rearrangement of normal structures, is a chronic maladaptive process characterized by vascular dysfunction, myocardial hypertrophy, apoptosis, necrosis, ventricular dilatation, and fibrosis [3]. Up to now, the underlying mechanism of this process has not been completely elucidated; several pathogeneses are involved: dysregulated neurohumoral stimulation, ischemia-related damage, increased hemodynamic overload, extracellular matrix (ECM) anomalies, immunological activation, accelerated cell apoptosis, and genetic mutations [4]. Agents targeting mitochondrial function/nerve-endocrine-immunity (NEI) network or utilization for ischemic conditioning/stem cell transplantation has been proved to partly alleviate adverse remodeling [5–7], but the role is still limited, thus exploring new biomarkers for diagnosis or as novel therapeutic targets for pathological remodeling needs further efforts. At this point, though, emerging data have suggested a fundamental role for noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) in remodeling-related cardiovascular diseases including atherosclerosis (AS), hypertension, aneurysm, postinfarct myocardial remodeling, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Long noncoding RNAs (LncRNAs), a kind of functional RNA molecules with the length of over 200 nucleotides, have once been regarded as the “noise” of genome transcription because of their deficiency in protein-coding process [8], but they now gained much attention in various fields like cancer and cardiocerebrovascular disease with the advancement of transcriptome program and chip technology. Plenty of evidence showed that lncRNAs are capable of regulating the occurrence and development of certain disorders. For instance, lncRNA H19 has been reported to be upregulated in atherosclerotic patients; by signaling to unique miRNAs or proteins, it may participate in multiple processes like vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) apoptosis, inflammation activation, and myocardial cell necrosis, thus deteriorating AS progression and ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury [9–13]. According to the update studies, lncRNAs not only served as diagnostic markers in cardiovascular disease, but also exhibited potentials for therapeutic applications [14]. Therefore, we provide a systematic perspective based on the regulatory roles of lncRNAs and discuss the challenges and possible applications of lncRNAs in cardiac remodeling.

2. LncRNAs: What Are They?

2.1. An Overview on Molecular and Biological Roles of LncRNAs

It is known that only 1.5% of the human genome is of protein-coding potential, and the remaining majority is illustrated to have no or very little protein-coding function [15]. LncRNAs, belonging to a class of ncRNAs with the length of more than 200 nucleotides, are now reported to have strong epigenetic regulation potentials. With the progress of high-throughput sequencing technology, thousands of eukaryotic lncRNAs are continually being found [16], and their expression profile seems to be cell-type specific and their subcellular localization in nucleus or cytoplasm is well-arranged [17, 18].

To understand the diverse species of lncRNAs more accurately, there are several convenient classification criteria. For example, according to genomic distribution, lncRNAs can be classified into 5 categories including sense lncRNAs, antisense lncRNAs, bidirectional lncRNAs, intronic lncRNAs, and intergenic lncRNAs, which were closely related to their stabilities [19]. In regard to biological functions, nuclear compartmentalization, genomic imprinting, X chromosome inactivation, cell fate specification, and RNA splicing were mainly involved. Here, we will summarize the current findings as follows.

2.1.1. Molecular Functions

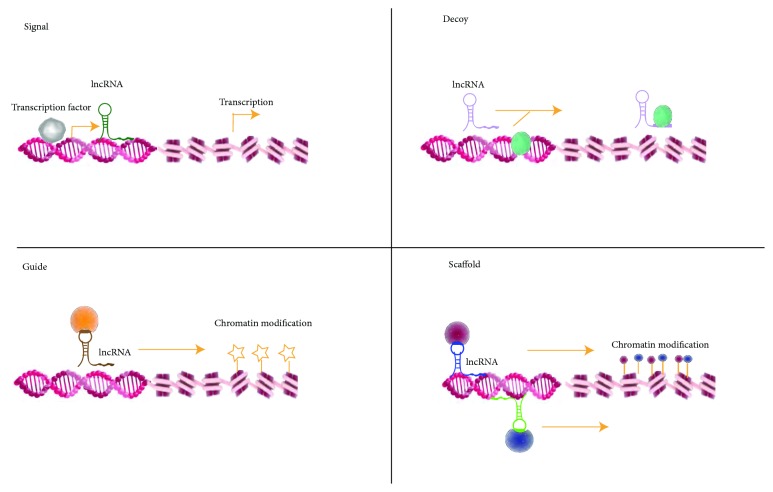

Similar to the protein-coding RNAs, lncRNAs have unique subcellular distribution that is crucial for functions, predominantly in nucleus and partially in the cytoplasm. The nuclear lncRNAs mainly perform transcriptional regulatory effects via guiding chromatin modifiers [20]. Others in cytoplasm were discovered to modulate mRNA translation or impact protein trafficking. According to the archetypes of molecular functions, lncRNAs were classified into 4 main categories: signals, decoys, guides, and scaffolds. As shown in Figure 1, briefly, among them are (1) signal lncRNAs, which could modulate gene expression in a time and space manner, (2) decoy lncRNAs, which could titrate transcription factors away from chromatin or titrate miRNAs away from their targets (acting as miRNA sponge), (3) guide lncRNAs, which serve as molecular chaperons, which can recruit chromatin-modifying enzymes to target genes, either in neighboring (cis) or distant location (trans), and (4) scaffold lncRNAs, which act as molecular scaffold, accumulating proteins to form ribonucleoprotein complexes and then promoting histone modification [21–23].

Figure 1.

Schematic Diagram of Basic LncRNA Mechanism.

Schematic diagram of basic LncRNA mechanism: nuclear-localized lncRNAs regulate gene expression basically in 4 modes including (1) signal, where lncRNAs expression can reflect actions of transcription factors (gray ovals), (2) decoy, where lncRNAs can sequester transcription factors/protein complex, and (3) guide, where lncRNAs can guide transcription factors/protein complex to specific target site and bring together multiprotein complexes as (4) scaffold.

2.1.2. Biological Functions

For biological functions, lncRNAs have been demonstrated to play multilayer roles such as the following: (1) nuclear compartmentalization: lncRNAs may contribute to regulating subnuclear structure such as paraspeckle formation; (2) chromatin modification: lncRNAs could participate in chromatin modification by interacting with epigenetic regulators and directing them into specific chromatin regions; lncRNA Kcnq1ot1, Air, and HOTAIR were all available examples [24, 25]; (3) RNA splicing: RNA splicing is a process that transforms the precursor messenger RNA (pre-mRNA) transcript into a mature messenger RNA (mRNA); (4) X chromosome inactivation: lncRNAs are also able to regulate X chromosome inactivation. For instance, X-inactive specific transcript (XIST) is known to silence hundreds of genes on the X chromosome in female somatic cells [26]. The other detailed functions will not be clarified here, but they also merit concern.

3. The Regulatory Role of LncRNA in Cardiac Remodeling

3.1. LncRNAs in Vascular Remodeling

The vessel wall is an integrated organ, containing endothelial cells (ECs), VSMCs, and also matrix components. Its function or structure is sensitive to variety of stimuli, many of which might drive physiopathologic changes. The dynamic adaptive process is defined as ‘vascular remodeling.' Vascular remodeling is accepted as the main pathological basis of hypertension and atherosclerosis as well as arterial aneurysm (AA), etc., which is usually characterized by increased vascular resistance, thickened intima, segmental stenosis, or aneurysmal dilatation. VSMC dysfunction serves as the foremost cellular basis for these adverse processes. Furthermore, the regulation of VSMCs is demonstrated to be quite involved with lncRNAs [27] (Table 1).

Table 1.

LncRNAs involved in vascular remodeling.

| Type | Cellular origin |

LncRNAs | Regulation | Target genes |

Related functions |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | VSMC | TUG1 | ↑ | miR-145-5p | promote migration and proliferation of VSMCs | Shi et al.[28] |

| VSMC | AK098656 | ↑ | myosin heavy chain-11/ fibronectin-1 | promote VSMC phenotypic switch | Jin et al. [29] | |

| VSMC | TRPV1 | ↓ | PI3K/Akt | inhibit VSMC phenotypic modulation |

Zhang et al. [30] | |

| VSMC/EC | GAS5 | ↓ | β-catenin | affect endothelial activation proliferation, andVSMC phenotypic conversion | Wang et al. [31] | |

| VSMC | Giver | ↑ | Nr4a3 | promote oxidative stress, VSMC proliferation and vascular inflammation | Das et al. [32] | |

| VSMC | Lnc-Ang362 | ↑ | miR221/222 | promote VSMC proliferation | Leung et al. [33] | |

|

| ||||||

| Atherosclerosis | VSMC | H19 | ↑ | ACP5 Wnt/β-catenin |

promote VSMC proliferation and inhibit apoptosis | Huang et al. [9] Zhang et al. [11] |

| VSMC/EC/ Macrophage |

TUG1 | ↑ | miR-21/PTEN miR-133a miR26a/FGF1 |

promote VSMC proliferation, facilitate EC/ macrophage apoptosis |

Li et al. [37] Chen et al. [38] Zhang et al. [39] |

|

| VSMC | UCA1 | ↓ | miR-26a/PTEN | suppress VSMC proliferation | Tian et al. [40] | |

| VSMC | MEG3 | ↓ | miR-26a/Smad1 | suppress VSMC proliferation | Bai et al. [41] | |

| VSMC | APPAT | ↓ | miR-647, miR-135b |

affect VSMC phenotype shift | Meng et al. [14] | |

| VSMC | lincRNA-p21 | ↓ | P53 | regulate neointima formation, VSMC proliferation and apoptosis | Wu et al. [42] | |

| VSMC | Neat1 | ↑ | SM-contractile gene | modulate VSMC phenotype conversion | Ahmed et al. [43] | |

|

| ||||||

| Arterial aneurysm | VSMC | HIF1A-AS1 | ↑ | caspase-3 | regulate VSMC apoptosis | He et al. [47] |

| VSMC | lincRNA-p21 | ↑ | TGF-β1 signaling | hinder proliferation and promote apoptosis of VSMCs | Hu et al. [48] | |

VSMC: vascular smooth muscle cell; EC: endothelial cell; TUG1: taurine upregulated 1; TRPV1: transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1; GAS5: growth block specificity 5; Giver: growth factor-and proinflammatory cytokine–induced vascular cell-expressed lncRNA; UCA1: urothelial carcinoma-associated; MEG3: maternally expressed gene 3; APPAT: atherosclerotic plaque pathogenesis associated transcript; lincRNA-p21: long intergenic noncoding RNA-p21; Neat1: nuclear paraspeckle assembly transcript 1; HIF1A-AS1: HIF1 alpha-antisense RNA1; ACP5: acid phosphatase 5; SM: smooth muscle.

3.1.1. Hypertension-Related Vascular Remodeling

LncRNAs such as taurine upregulated 1 (TUG1) [28], AK098656 [29], transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) [30], growth block specificity 5 (GAS5) [31], growth factor-and proinflammatory cytokine-induced vascular cell-expressed lncRNA (Giver) [32], and Lnc-Ang362 [33] are newly demonstrated participators in hypertension-related remodeling through regulating VSMC behaviors. Study shows that lncRNA TUG1 was highly concentrated in aorta of spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR). The overexpressed TUG1 is not just a biomaker, but an essential actor via sponging miR-145-5p to promote the migration and proliferation of SHR-VSMCs, subsequently causing Wnt/β-catenin pathway activation [28]. Similarly, Jin et al. revealed that lncRNA-AK098656 mainly of VSMC origin was markedly upregulated in the plasma of hypertension patients compared to healthy ones. AK098656-overexpressing transgenic rats would spontaneously progress to hypertension, presenting increased media thickness and narrowed arterial lumen. The promotion of VSMC phenotypic switch by directly binding to the SM-specific contractile proteins and inducing their degradation undertook the underlying mechanism [29]. LncRNA GAS5, mainly expressed in ECs/VSMCs, was also suggested to participate in hypertension via modulating multiple links such as EC proliferation, VSMC phenotype conversion, and EC-VSMC communication by β-catenin signaling; knockdown of GAS5 could aggravate microvascular dysfunction [31]. Giver, the nuclear enriched transcript, was found to dramatically be overexpressed in arteries from untreated hypertensive patients and identified as a novel regulator of AngII-induced VSMC dysfunction by microarray analysis. Mechanically, it might promote oxidative stress, VSMC proliferation, and vascular inflammation via altering the state of chromatin—negatively regulating its neighboring gene Nr4a3 expression [32].

3.1.2. Atherosclerotic Vascular Remodeling

Plenty of studies have been published on lncRNA-mediated atheromatous plaque development via regulating responses of vessel cells [34]. Through database retrieval, NONCODE, H19, ANRIL, and CDKN2B-AS1 were identified as AS-related lncRNAs [9]. Among them, LncRNA H19 is the hotspot in recent decades, which not only acts as the potential serum marker of CHD [35, 36], but also largely takes part in the progression of AS. Huang et al. demonstrated that lentivirus-mediated H19-forced expression promotes VSMC proliferation and inhibits its apoptosis in vitro, and if in the ischemic stroke mouse model, an increased plaque size was detected with H19 overexpression but dramatically diminished while silencing. Upregulating the expression of acid phosphatase 5(ACP5) at posttranscriptional level is the key mechanism by which H19 contributes to the harmful performance [9]. Zhang et al. have also reported the roles of H19 in AS previously. The interpretation still attributed to regulation of the imbalance of VSMC proliferation and apoptosis. Knockdown of H19 efficiently suppressed proliferation and facilitated apoptosis in ox-LDL-treated human aorta VSMCs by blocking Wnt/β-catenin pathway, thus alleviating intimal thickening [11]. Besides, elevated expression of H19 was as well detected in ox-LDL-stimulated Raw264.7 cells, which played roles in promoting lipid accumulation and proinflammatory factors release [12]. Thereby, the approach to silence H19 expression might turn into a promising application in preventing AS, although the deep mechanism is still imperative in vivo.

LncRNA TUG1, as mentioned above, is a vital regulator in modulation of VSMC behaviors. Recent studies have likewise explored its impacts on the advancement of AS. Results showed TUG1 was highly expressed in the serum of patients suffering from AS as well as in the plaque tissue of ApoE-/-mice. Knockdown of TUG1 led to suppressed inflammatory response and attenuated atherosclerotic lesion. The abnormal proliferation of VSMCs [37], together with excessive apoptosis of ECs [38] and macrophages [39] induced by TUG1-miRNA (miR-21/133a/26a) interactions, took the main responsibility.

Urothelial carcinoma-associated (UCA1) [40] and maternally expressed gene 3 (MEG3) [41] are regarded as two types of protective lncRNAs under the atherogenic conditions, both of which could perform as endogenous sponge of miR-26a, and induce a modified expression of the target proteins (e.g., PTEN and Smad1).

Atherosclerotic plaque pathogenesis associated transcript (APPAT), just as its name, is an important predictor of disease progression. Significant decrease of APPAT was detected in coronary artery samples with severe stenosis and high-risk individuals. The potential mechanism is partly attributed to the influence of VSMC phenotype shift via signaling to special miRNAs (e.g., miR-647/135b) [14].

Besides, long intergenic noncoding RNA-p21 (lincRNA-p21) had been identified as another beneficial regulator against AS. Levels of lincRNA-p21 were markedly downregulated in plaque lesions of ApoE-/-mice model as well as in coronary artery tissue of CHD patients, and lentivirus-si-lincRNA-P21 injected into the injury site induced dramatical neointimal hyperplasia [42].

Nuclear paraspeckle assembly transcript 1 (Neat1) was reported to promote intima thickening or even vascular occlusion by modulating the phenotype conversion of VSMCs. Neat1 knockout mice showed suppressed neointima formation after vascular injury, and the upregulation of SM-contractile gene was the main mechanism [43].

3.1.3. Aortic Aneurysm

Aortic aneurysm is a life-threatening pathological condition with the possibility to rupture when silently progressing to the advanced state, generally characterized by VSMC loss, medial degeneration, and bulging of the vessel wall. Currently, no specific pharmacological approaches exist that could slow down the progression and risk of aneurysm rupture, except for surgical intervention. With advances of molecular research, the participation of lncRNAs has been gradually concerned. LncRNA-related VSMC dysfunction and ECM degradation were suggested as potential mechanisms according to recent data. Microarray profile analysis revealed that hundreds and thousands of lncRNAs are involved in human thoracic aortic aneurysm (TAA) development, such as Lnc-HLTF-5 [44], HIF1A-AS1, RP11-465L10.10, and CTD-2184D3.5 [45], which might play roles in regulating the expression of MMP-9 in aortic tissue and then facilitate the expansionary remodeling. HIF1alpha-antisense RNA 1 (HIF1A-AS1) was the first reported lncRNA participating in TAA pathogenesis [46]. Increased expression of HIF1A-AS1 was usually found in plasma of TAA patients, knockdown of which led to attenuated apoptosis of VSMCs by suppressing caspase-3/8 expression [47]. LincRNA-p21 was another reported lncRNA associated with TAA. Upregulated expression of lincRNA-p21 is found both in aortic media and in blood samples in established TAA patients. LincRNA-p21 forced expression might hinder proliferation and promote apoptosis of VSMCs, thus thinning the media [48]. The discovery of the association between lncRNAs and TAAs might provide potential diagnostic biomarkers or therapeutic targets for this occult but dangerous disease.

3.2. LncRNAs in Myocardial Remodeling

Myocardial remodeling, which consists of morphological, behavioral, metabolic, or electrical alteration, is a maladaptive response that is common in ventricular remodeling after MI or various types of cardiomyopathy. Myocardial remodeling is mainly manifested as loss of cardiomyocytes, cardiac hypertrophy, metabolic abnormalities, defective autophagy, electrical remodeling, and so on. Ischemia injury would promote the release of reactive oxygen species (ROS), resulting in dysfunction of the energy metabolism, or even death of cardiomyocytes. Persistent loss of cardiomyocytes may ultimately induce cardiac remodeling. With regard to cardiac hypertrophy, it is a compensative response to volume or stress overload stimuli, aiming at lowering the increased wall tension and maintaining the cardiac output, while persistent exposure of enhanced load would also accelerate cardiomyocytes loss, interstitial fibrosis, or even cardiac failure (Table 2).

Table 2.

LncRNAs involved in myocardial remodeling.

| Type | Cellular behavior |

LncRNAs | Regulation | Target genes |

Related functions |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-ischemia/hypoxia myocardial remodelling | Autophagy | Neat1 | ↑ | Foxo1 | activate autophagy, aggravate CM injury | Ma et al. [49] |

| AK139328 | ↑ | miR-204-3p | activate autophagy, aggravate CM injury | Yu et al. [50] | ||

| APF | ↑ | miR-188-3p | induce autophagic cell death | Wang et al. [51] | ||

| CAIF | ↓ | p53 | inhibit autophagy | Liu et al. [52] | ||

| AK088388 | ↑ | miR-30a | induce autophagic injury | Wang et al. [53] | ||

|

| ||||||

| Post-ischemia/hypoxia myocardial remodelling | Apoptosis | CARL | ↓ | miR-539 | suppress mitochondrial fission and apoptosis | Wang et al. [54] |

| MALAT1 | ↑ | miR-203 | exacerbate inflammation and apoptosis | Wang et al. [55] | ||

| HOTAIR | ↓ | miR-125, miR-1 |

inhibit apoptosis | Li et al. [56] Gao et al. [57] |

||

| UCA1 | ↑ | unspecified | suppress ER-stress and apoptosis | Chen et al. [58] | ||

| XIST | ↑ | miR-130a-3p | facilitate apoptosis, inhibit proliferation | Zhou et al. [59] | ||

|

| ||||||

| Post-ischemia/hypoxia myocardial remodelling | Necrosis | NRF | ↑ | miR-873 | facilitate necrosis | Wang et al. [60] |

| H19 | ↑ | miR-103/107 | promote necrosis | Wang et al. [61] | ||

|

| ||||||

| Myocardial hypertrophy | Hypertrophy | Mhrt | ↓ | Brg1 | inhibit cardiac hypertrophy | Hang et al. [62] Han et al. [63] |

| Chast | ↑ | Plekhm1 | hinder autophagy and facilitate hypertrophy | Viereck et al. [64] | ||

| CHRF | ↓ | miR-489 | anti-hypertrophic | Wang et al. [65] | ||

| ROR | ↑ | miR-133 | promote hypertrophy | Jiang et al. [66] | ||

| H19 | ↓ | miR-675 | protect CMs from hypertrophy | Liu et al. [67] | ||

| Plscr4 | ↑ | miR-214 | attenuate cardiac hypertrophy |

Lv et al. [68] | ||

| MIAT | ↑ | miR-150 | promote hypertrophy | Zhu et al. [69] | ||

|

| ||||||

| Myocardial hypertrophy | Electrical remodeling | TCONS_00075467 | ↓ | miRNA-328 | affect the effective refractory period, increase the action potential duration in AF | Li et al. [70] |

| MALAT1 | ↑ | miR-200c | regulate transient outward potassium current | Zhu et al. [71] | ||

Neat1: nuclear-enriched abundant transcript1; APF: autophagy promoting factor; CAIF: cardiac autophagy inhibitory factor; CARL: cardiac apoptosis-related lncRNA; MALAT1:metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1; HOTAIR:HOX antisense intergenic RNA;UCA1:urothelial carcinoma-associated; XIST:X-inactive specific transcript; Mhrt: myosin heavy chain associated RNA transcripts; Chast: cardiac hypertrophy-associated transcript; Plekhm1:pleckstrin homology domain-containing protein family M member 1; CHRF: cardiac hypertrophy-related factor; MIAT: myocardial infarction–associated transcript; Foxo1:forkhead box protein O1;ER:endoplasmic reticulum; CM: cardiomyocyte; AF: atrial fibrillation.

3.2.1. LncRNAs in Postischemia/Hypoxia Myocardial Remodeling

Up to now, by using high-throughput RNA sequencing, numerous lncRNAs have been found involved in the modulation of cardiac remodeling. In I/R condition, lncRNAs are reported to largely participate in myocardial autophagy (e.g., Neat1, AK139328, APF, CAIF, and AK088388), apoptosis (e.g., CARL, MALAT1, HOTAIR, UCA1, and XIST) and necrosis (e.g., NRF and H19), and then regulating the remodeling process. Neat1 [49] and AK139328 [50] were both demonstrated to be overexpressed in I/R-treated diabetic rat myocardial tissue; upregulated Neat1 and AK139328 might aggravate I/R injury via activating autophagy of cardiomyocytes, while inhibiting their expression significantly alleviates the damage. Autophagy promoting factor (APF), a novel regulator in autophagy, can induce autophagic cell death via signaling to miR-188-3p, thus augmenting myocardial infarction size [51]. Another characterized lncRNA termed cardiac autophagy inhibitory factor (CAIF) was nevertheless found to show opposite effects. Enforced expression of CAIF significantly attenuated autophagic death and infarction size induced by I/R injury, with the mechanism that p53/myocardin-mediated harmful autophagy was blocked [52]. Besides, in a hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R) cardiomyocyte model, AK088388 was demonstrated to be highly expressed, which could competitively bind to miR-30a targeting beclin-1 and LC3-II expression, inducing autophagic injury; miR-30a mimics or siRNA-AK088388 however could maintain cardiomyocyte viability and reduce apoptosis [53].

Cardiac apoptosis-related lncRNA (CARL) was an early described apoptosis inhibitor of cardiomyocytes, which could suppress anoxia-induced mitochondrial fission and apoptosis by sponging miR-539 targeting prohibitin-2 (PHB2) [54]. Metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript1 (MALAT1) is another highly expressed lncRNA in cardiac tissue during I/R injury, which may exacerbate cardiomyocyte inflammation and apoptosis by sponging miR-203 [55]. HOX antisense intergenic RNA (HOTAIR) was reported as a protective lncRNA, usually downregulated by hypoxia exposure or acute myocardial ischemia. HOTAIR overexpression markedly limited hypoxia/ischemia-induced myocardial apoptosis, whereas knockdown of HOTAIR severely accelerated apoptosis. Mechanically, the cardioprotective effect is partly based on HOTAIR-miR-125 or HOTAIR-miR-1 interactions [56, 57]. LncRNA UCA1 could be triggered reactively during I/R injury; overexpression of UCA1 by adenovirus transfection conferred significant myocardial protection by suppressing endoplasmic reticulum stress and ROS-induced cell apoptosis [58]. XIST was found to overexpress in cardiomyocytes after infarction, and the highly expressed XIST might facilitate apoptosis and inhibit proliferation by targeting miR-130a-3p [59].

In terms of myocardial necrosis, the lncRNA named necrosis-related factor (NRF) is worth mentioning. NRF facilitated the programmed necrosis of myocardial cells under I/R condition by the mechanism of sponging miR-873 expression and promoting RIPK1/RIPK3-induced necrotic cell death; knockdown of NRF could effectively antagonize necrosis and confer cardioprotection [60]. Except for NRF, H19 was also a participator. It regulated RIPK1/RIPK3-dependent myocardial cell necrosis by directly binding to miR-103/107 and further modulating the expression of FADD (fas-associated protein with death domain), the target gene of miR-103/107 [61].

3.2.2. LncRNAs in Myocardial Hypertrophy

Myocardial hypertrophy is an adaptive morphological change to volume or stress overload stimuli, compensatory at the start but useless or harmful in the late stage. LncRNAs are emerging as new players in this pathophysiological process. Myosin heavy chain associated RNA transcript (Mhrt) is the first example of lncRNA which acts as chromatin remodelers and inhibits pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Mhrt has been confirmed to interact directly with Brg1 (the significant chromatin-remodeling factor in myocardial hypertrophy) and sequester Brg1 from its genomic DNA targets so as to maintain cardiac performance [62, 63]. According to cell fractionation experiment, cardiac hypertrophy-associated transcript (Chast) was indicated to be specifically upregulated in cardiomyocytes from transverse aortic constriction (TAC)-operated mice model and also in hypertrophic heart tissue from aortic stenosis patients. The mechanism by which it drives hypertrophy is involved in the negative regulation of pleckstrin homology domain-containing protein family M member 1(Plekhm1), the gene located on its opposite strand, thus hindering cardiomyocyte autophagy and facilitating hypertrophy [64].

Besides, unlike the chromatin- or gene-regulation effect of lncRNAs mentioned above, many other lncRNAs were reported to participate in cardiac hypertrophy by functioning as sponges of miRNAs, such as cardiac hypertrophy-related factor (CHRF) [65], ROR [66], H19 [67], Plscr4 [68], and myocardial infarction-associated transcript (MIAT) [69]. CHRF showed an antihypertrophic effect in vitro by suppressing miR-489/myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88) signaling as an endogenous sponge. According to Jiang's study, lncRNA ROR was demonstrated as an impeller of cardiac hypertrophy, the levels of which were dramatically increased in hypertrophic heart tissue and cardiomyocytes. Knockdown of ROR could effectively attenuate the prohypertrophic response via promotion of miR-133 expression (which acted as a ceRNA) and further decreasing the B type natriuretic peptide (BNP) level. LncRNA H19, another negative regulator, was found to protect cardiomyocytes from phenylephrine-stimulated hypertrophy via targeting miR-675. Overexpression of H19 can reduce the increase of cell size and prohypertrophic gene levels, while inhibition of miR-675 abolished the protective effect. In TAC-operated mice model, lncRNA Plscr4 forced expression was indicated to attenuate cardiac hypertrophy by sponging miR-214 and further upregulating mitofusin 2 (Mfn2) expression, a critical modulator of mitochondrial homeostasis. Furthermore, lncRNA MIAT was also verified to participate in the progression of AngII-induced H9C2 cell hypertrophy in vitro by serving as a ceRNA of miR-150.

3.2.3. LncRNAs in Myocardial Electrical Remodeling

Up to date, not many studies have been done on lncRNA-related myocardial electrical remodeling. Li et al. conducted a research by using RNA-seq technique in rabbit models with atrial fibrillation (AF), and the lncRNA expression profiles of right atria were investigated. They identified a total of 99,843 lncRNAs, among which TCONS_00075467 was the selected player. TCONS_00075467 could sponge miRNA-328 both in vitro and in vivo to regulate the gene CACNA1C expression, prolonging the effective refractory period and increasing the action potential duration [70]. MALAT1 was also indicated in regulation of electrical activity by signaling to miR-200c in cardiomyocytes from arrhythmic rats model, and it presented overexpression state. Knockdown of MALAT1 could markedly increase transient outward potassium current and Kv4.2/Kv4.3 channel proteins expression, affecting the outcome of arrhythmias [71].

3.3. LncRNAs in Cardiac ECM Remodeling

The cardiac ECM not only provides mechanical support for myocardium, but also transduces essential molecular signals to regulate myocardial function. Dynamic ECM changes happened during myocardial ischemia or chronic volume and pressure overload and ultimately progressed to HF. Cardiac fibroblasts largely drove these pathological processes. Meanwhile, lncRNAs are important regulators of cardiac fibroblasts (CFs) biology. So far, several lncRNAs have been confirmed in cardiac fibrosis and ECM remodeling. By RNA-seq analysis on cardiac samples from ischemic cardiomyopathy patients, Huang et al. found a series of 35 lncRNAs that exhibit strong positive correlation with ECM protein-coding genes. The 5 screened lncRNAs (e.g., n379599, n379519, n380433, n384640, and n410105) by loss- and gain-of-function studies modulated the ECM gene expression, mainly dependent on TGF-β pathway [72]. Additionally, in Qu et al.'s study, lncRNAs profile of peri-infarct tissue in mice was checked for bioinformatic analysis, and they found that 263 lncRNAs were significantly upregulated and 282 were downregulated. Among them, NONMMUT022554 was identified as the top-ranked lncRNA positively correlated with genes which were strongly involved in the ECM-receptor interactions [73]. Except for omics study, certain lncRNAs such as MALAT1, wisper, MEG3, H19, and GAS5 were also published to take part in fibrosis and remodeling. In the study performed both in vivo with MI mice model and in vitro with CFs isolated from newborn pups, Huang et al. found that MALAT1 was specifically upregulated in MI heart and in AngII-stimulated CFs; knockdown of MALAT1 could alleviate cardiac fibrosis post-MI and AngII-induced fibroblast proliferation and collagen synthesis by suppressing TGF-β1 activity [74]. Wisp2 super-enhancer–associated RNA (Wisper) was another CF-enriched lncRNA that aggravated cardiac fibrosis after injury. Loss-of-function approach in vitro suggested it largely took part in CF proliferation, migration, and survival. Silencing Wisper in vivo in accordance alleviated MI-induced fibrosis and cardiac dysfunction; the regulation of lysyl hydroxylase 2 expression and collagen cross-linking was the possible mechanism [75]. MEG3, mostly expressed by CFs, was found to promote matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) production both in vitro and in vivo, thus inducing increased cardiac fibrosis and impaired diastolic performance, silencing of which reversed the effects [76]. The functional validation study discovered that H19 knockdown enhanced the antifibrotic effect of miR-455, decreased the connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) expression, and further inhibited fibrosis-associated protein synthesis, thereby revealing a vital function of the H19/miR-455/CTGF axis in cardiac fibrosis [13]. Furthermore, a suppressive lncRNA in cardiac fibrosis termed GAS5 was also reported. GAS5 was lowly expressed in activated CFs, overexpression of which could inhibit CF proliferation by negatively regulating miR-21 targeting PTEN expression, as it also suggested a potential therapeutic target for fibrosis [77].

4. Therapeutic Targeting of LncRNA in Cardiac Remodeling

Cardiac remodeling is a chronic progressive process accompanied by abnormality of cell behaviors, remodeling of matrix components, and impairment of organ function. Certain pharmacological agents or applications of stem cell transplantation and cardiac/remote ischemic conditioning have been found as effective intervention strategies [6, 7], while the exact mechanisms and targets were not so clear. With the advanced knowledge of lncRNAs, the pathogenesis of cardiac remodeling was reinterpreted from the perspective of epigenetics. As mentioned above, numerous studies have confirmed the critical roles of lncRNAs in remodeling by loss- and gain-of-function experiments and have also presumed their potentials as therapeutic targets. According to current data, atorvastatin application has been demonstrated to protect cardiac progenitor cells (CPCs) from hypoxia-induced injury in vitro by inhibiting MEG3 expression, thus providing a clue for lncRNA-related mechanism behind the drug's benefits for MI/HF therapy [78]. Losartan could alleviate Ang II-induced cardiac fibrosis via reversing the downregulation of lncRNA-NR024118 and Cdkn1c in adult rats [79]. Beyond that, manipulating the expression of specific lncRNAs with genetic methods (specifically overexpressed or knockdown) has been largely carried out in animal models, being confirmed to regulate remodeling such as myocardial inflammation, apoptosis, and hypertrophy [55, 57, 67]. Although, theoretically, to modulate lncRNAs' expression specifically—elevating the profiles downregulated or decreasing the ones upregulated in different settings of disease—is an embodiment of precision therapy, a challenge is that the existing research mode can not be completely transformed into clinical trials. On the way to the goal, many questions persist. First, the lncRNAs are poor sequence conservation, and it might be crucial to identify the detailed single-cell or single-molecule profiling at different stages and backgrounds. Second, lncRNAs are usually short-life and damage-prone, and in order to achieve targeted delivery and long-term effectivity, some exogenous gene delivery vectors (e.g., exosomes, nanoparticles, and liposomes) or CRISPR–Cas9 genome editing technology might be required in in vivo experiments, and what followed is how to determine the delivery timing, pattern, concentration, etc.

Until now, there is no clinical trial which has been performed. In the whole noncoding RNA field, anti-miR-122 have finished a phase II clinical trial for treatment of hepatitis C virus infection, which suggested the potential therapeutic role of ncRNAs [80, 81]. Future work would focus on deeper understanding of lncRNA regulatory network, optimization of delivery techniques, and investigation of the interplay of lncRNAs with known beneficial/harmful signaling pathways so as to promote rapid clinical transformation of lncRNAs and their connections with cellular therapy or cardiac regeneration therapy.

5. Conclusions

LncRNAs have shown strong regulatory effects in pathological cardiovascular remodeling; therefore, to manipulate lncRNA expression specifically is of promising therapeutic potential. Up to date, most of the available data were in in vitro findings or in animal models, and no clinical trial has been published. In the future, with the development of RNA-seq and gene transfection technology, more lncRNAs linked with cardiac remodeling would be discovered. In addition, targeted delivery of lncRNAs by exosomes or other carriers into the infarcted heart or culprit vessel might promote more meaningful clinical translation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor Shixin Xu from Experimental Center and Professor Yaping Zhu from Cardiology Department of the First Teaching Hospital of Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine for their meaningful suggestions. This study has received funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81774232/81473634).

Data Availability

The materials in this manuscript are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no financial or other conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Junping Z conceived the review and analyzed the relevant literature. Huan Z collected literature and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Bin W, Ying-xi Y, Qiu-jin J, Ao Z, and Zhong-wen Q all critically revised the manuscript.

References

- 1.Benjamin E. J., Blaha M. J., Chiuve S. E., et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2017 update: a report from the american heart association. Circulation. 2017;135(10):e146–e603. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joseph P., Leong D., McKee M., et al. Reducing the global burden of cardiovascular disease, part 1: the epidemiology and risk factors. Circulation Research. 2017;121(6):677–694. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.308903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfeffer M. A., Braunwald E. Ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction: experimental observations and clinical implications. Circulation. 1990;81(4):1161–1172. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.81.4.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braunwald E. Heart failure. JACC: Heart Failure. 2013;1(1):1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campo G., Pavasini R., Morciano G., et al. Clinical benefit of drugs targeting mitochondrial function as an adjunct to reperfusion in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. International Journal of Cardiology. 2017;244:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gallet R., Dawkins J., Valle J., et al. Exosomes secreted by cardiosphere-derived cells reduce scarring, attenuate adverse remodelling, and improve function in acute and chronic porcine myocardial infarction. European Heart Journal. 2017;38(3):201–211. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamaguchi T., Izumi Y., Nakamura Y., et al. Repeated remote ischemic conditioning attenuates left ventricular remodeling via exosome-mediated intercellular communication on chronic heart failure after myocardial infarction. International Journal of Cardiology. 2015;178:239–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.10.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mattick J. S., Rinn J. L. Discovery and annotation of long noncoding RNAs. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 2015;22(1):5–7. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang Y., Wang L., Mao Y., Nan G. Long noncoding RNA-H19 contributes to atherosclerosis and induces ischemic stroke via the upregulation of acid phosphatase 5. Frontiers in Neurology. 2019;10:p. 32. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pan J.-X. LncRNA H19 promotes atherosclerosis by regulating MAPK and NF-kB signaling pathway. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 2017;21(2):322–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang L., Cheng H., Yue Y., Li S., Zhang D., He R. H19 knockdown suppresses proliferation and induces apoptosis by regulating miR-148b/WNT/β-catenin in ox-LDL -stimulated vascular smooth muscle cells. Journal of Biomedical Science. 2018;25(1):p. 11. doi: 10.1186/s12929-018-0418-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han Y., Ma J., Wang J., Wang L. Silencing of H19 inhibits the adipogenesis and inflammation response in ox-LDL-treated Raw264.7 cells by up-regulating miR-130b. Molecular Immunology. 2018;93:107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2017.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang Z.-W., Tian L.-H., Yang B., Guo R.-M. Long noncoding RNA H19 acts as a competing endogenous RNA to mediate CTGF Expression by sponging miR-455 in cardiac fibrosis. DNA and Cell Biology. 2017;36(9):759–766. doi: 10.1089/dna.2017.3799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meng F., Yan J., Ma Q., et al. Expression status and clinical significance of lncRNA APPAT in the progression of atherosclerosis. PeerJ. 2018;6 doi: 10.7717/peerj.4246.e4246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ENCODE Project Consortium. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489(7414):57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Volders P., Verheggen K., Menschaert G., et al. An update on LNCipedia: a database for annotated human lncRNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Research. 2015;43(D1):D174–D180. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guttman M., Rinn J. L. Modular regulatory principles of large non-coding RNAs. Nature. 2012;482(7385):339–346. doi: 10.1038/nature10887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Batista P. J., Chang H. Y. Cytotopic localization by long noncoding RNAs. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2013;25(2):195–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kopp F., Mendell J. T. Functional classification and experimental dissection of long noncoding RNAs. Cell. 2018;172(3):393–407. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fatica A., Bozzoni I. Long non-coding RNAs: new players in cell differentiation and development. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2014;15(1):7–21. doi: 10.1038/nrg3606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu G., Niu F., Humburg B. A., et al. Molecular mechanisms of long noncoding RNAs and their role in disease pathogenesis. Oncotarget. 2018;9(26):18648–18663. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.24307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akhade V. S., Pal D., Kanduri C. Long Noncoding RNA: Genome organization and mechanism of action. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2017;1008:47–74. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-5203-3_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen L. Linking Long Noncoding RNA Localization and Function. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2016;41(9):761–772. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Terranova R., Yokobayashi S., Stadler M. B., et al. Polycomb group proteins Ezh2 and Rnf2 direct genomic contraction and imprinted repression in early mouse embryos. Developmental Cell. 2008;15(5):668–679. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pandey R. R., Mondal T., Mohammad F., et al. Kcnq1ot1 antisense noncoding rna mediates lineage-specific transcriptional silencing through chromatin-level regulation. Molecular Cell. 2008;32(2):232–246. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wutz A., Gribnau J. X inactivation Xplained. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 2007;17(5):387–393. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Indolfi C., Iaconetti C., Gareri C., Polimeni A., De Rosa S. Non-coding RNAs in vascular remodeling and restenosis. Vascular Pharmacology. 2019;114:49–63. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2018.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shi L., Tian C., Sun L., Cao F., Meng Z. The lncRNA TUG1/miR-145-5p/FGF10 regulates proliferation and migration in VSMCs of hypertension. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2018;501(3):688–695. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jin L., Lin X., Yang L., et al. AK098656, a novel vascular smooth muscle cell–dominant long noncoding RNA, promotes hypertension. Hypertension. 2018;71(2):262–272. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.09651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang M., Liu Y., Hu Z., et al. TRPV1 attenuates intracranial arteriole remodeling through inhibiting VSMC phenotypic modulation in hypertension. Histochemistry and Cell Biology. 2017;147(4):511–521. doi: 10.1007/s00418-016-1512-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Y., Shan K., Yao M., et al. Long noncoding RNA-GAS5: a novel regulator of hypertension-induced vascular remodeling. Hypertension. 2016;68(3):736–748. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.07259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Das S., Zhang E., Senapati P., et al. A novel angiotensin II-induced long noncoding RNA giver regulates oxidative stress, inflammation, and proliferation in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circulation Research. 2018;123(12):1298–1312. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leung A., Trac C., Jin W., et al. Novel long noncoding RNAs are regulated by angiotensin II in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circulation Research. 2013;113(3):266–278. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.300849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li H., Zhu H., Ge J. Long noncoding RNA: recent updates in atherosclerosis. International Journal of Biological Sciences. 2016;12(7):898–910. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.14430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bitarafan S., Yari M., Broumand M. A., et al. Association of increased levels of lncRNA H19 in PBMCs with risk of coronary artery disease. Cell Journal. 2019;20(4):564–568. doi: 10.22074/cellj.2019.5544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Z., Gao W., Long Q.-Q., et al. Increased plasma levels of lncRNA H19 and LIPCAR are associated with increased risk of coronary artery disease in a Chinese population. Scientific Reports. 2017;7(1):p. 7491. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07611-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li F. P., Lin D. Q., Gao L. Y. LncRNA TUG1 promotes proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cell and atherosclerosis through regulating miRNA-21/PTEN axis. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 2018;22(21):7439–7447. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201811_16284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen C., Cheng G., Yang X., Li C., Shi R., Zhao N. Tanshinol suppresses endothelial cells apoptosis in mice with atherosclerosis via lncRNA TUG1 up-regulating the expression of miR-26a. American Journal of Translational Research. 2016;8(7):2981–2991. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang L., Cheng H., Yue Y., Li S., Zhang D., He R. TUG1 knockdown ameliorates atherosclerosis via up-regulating the expression of miR-133a target gene FGF1. Cardiovascular Pathology. 2018;33:6–15. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2017.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tian S., Yuan Y., Li Z., Gao M., Lu Y., Gao H. LncRNA UCA1 sponges miR-26a to regulate the migration and proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells. Gene. 2018;673:159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bai Y., Zhang Q., Su Y., Pu Z., Li K. Modulation of the proliferation/apoptosis balance of vascular smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis by lncRNA-MEG3 via regulation of miR-26a/Smad1 axis. International Heart Journal. 2019;60(2):444–450. doi: 10.1536/ihj.18-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu G., Cai J., Han Y., et al. LincRNA-p21 regulates neointima formation, vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation, apoptosis, and atherosclerosis by enhancing p53 activity. Circulation. 2014;130(17):1452–1465. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.114.011675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ahmed A. S. I., Dong K., Liu J., et al. Long noncoding RNA NEAT1 (nuclear paraspeckle assembly transcript 1) is critical for phenotypic switching of vascular smooth muscle cells. Proceedings of the National Acadamy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2018;115(37):E8660–E8667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1803725115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li Y., Liu Y., Liu S., et al. Differential expression profile of long non-coding RNAs in human thoracic aortic aneurysm. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2018;119(10):7991–7997. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li Y., Yang N. Microarray expression profile analysis of long non-coding RNAs in thoracic aortic aneurysm. Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences. 2018;34(1):34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2017.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang S., Zhang X., Yuan Y., et al. BRG1 expression is increased in thoracic aortic aneurysms and regulates proliferation and apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells through the long non-coding RNA HIF1A-AS1 in vitro. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. 2015;47(3):439–446. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezu215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.He Q., Tan J., Yu B., Shi W., Liang K. Long noncoding RNA HIF1A-AS1A reduces apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells: Implications for the pathogenesis of thoracoabdominal aorta aneurysm. Die Pharmazie. 2015;70(5):310–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hu W., Wang Z., Li Q., Wang J., Li L., Jiang G. Upregulation of lincRNA-p21 in thoracic aortic aneurysms is involved in the regulation of proliferation and apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells by activating TGF-β1 signaling pathway. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2019;120(3):4113–4120. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ma M., Hui J., Zhang Q., Zhu Y., He Y., Liu X. Long non-coding RNA nuclear-enriched abundant transcript 1 inhibition blunts myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury via autophagic flux arrest and apoptosis in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Atherosclerosis. 2018;277:113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yu S.-Y., Dong B., Fang Z.-F., Hu X.-Q., Tang L., Zhou S.-H. Knockdown of lncRNA AK139328 alleviates myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion injury in diabetic mice via modulating miR-204-3p and inhibiting autophagy. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2018;22(10):4886–4898. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang K., Liu C.-Y., Zhou L.-Y., et al. APF lncRNA regulates autophagy and myocardial infarction by targeting miR-188-3p. Nature Communications. 2015;6, article 6779 doi: 10.1038/ncomms7779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu C.-Y., Zhang Y.-H., Li R.-B., et al. LncRNA CAIF inhibits autophagy and attenuates myocardial infarction by blocking p53-mediated myocardin transcription. Nature Communications. 2018;9(1):p. 29. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02280-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang J., Bie Z., Sun C. Long noncoding RNA AK088388 regulates autophagy through miR-30a to affect cardiomyocyte injury. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2019;120(6):10155–10163. doi: 10.1002/jcb.28300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang K., Long B., Zhou L.-Y., et al. CARL lncRNA inhibits anoxia-induced mitochondrial fission and apoptosis in cardiomyocytes by impairing miR-539-dependent PHB2 downregulation. Nature Communications. 2014;5:p. 3596. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang S., Yu W., Chen J., Yao T., Deng F. LncRNA MALAT1 sponges miR-203 to promote inflammation in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. International Journal of Cardiology. 2018;268:p. 245. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.03.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li L., Zhang M., Chen W., et al. LncRNA-HOTAIR inhibition aggravates oxidative stress-induced H9c2 cells injury through suppression of MMP2 by miR-125. Acta Biochimica et Biophysica Sinica. 2018;50(10):996–1006. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmy102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gao L., Liu Y., Guo S., et al. Circulating long noncoding RNA HOTAIR is an essential mediator of acute myocardial infarction. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. 2017;44(4):1497–1508. doi: 10.1159/000485588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen J., Hu Q., Zhang B. F., Liu X. P., Yang S., Jiang H. Long noncoding RNA UCA1 inhibits ischaemia/reperfusion injury induced cardiomyocytes apoptosis via suppression of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Genes & Genomics. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s13258-019-00806-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhou T., Qin G., Yang L., Xiang D., Li S. LncRNA XIST regulates myocardial infarction by targeting miR-130a-3p. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2019;234(6):8659–8667. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang K., Liu F., Liu C.-Y., et al. The long noncoding RNA NRF regulates programmed necrosis and myocardial injury during ischemia and reperfusion by targeting miR-873. Cell Death & Differentiation. 2016;23(8):1394–1405. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2016.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang J.-X., Zhang X.-J., Li Q., et al. MicroRNA-103/107 regulate programmed necrosis and myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury through targeting FADD. Circulation Research. 2015;117(4):352–363. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.305781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hang C. T., Yang J., Han P., et al. Chromatin regulation by Brg1 underlies heart muscle development and disease. Nature. 2010;466(7302):62–67. doi: 10.1038/nature09130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Han P., Li W., Lin C. H., et al. A long noncoding RNA protects the heart from pathological hypertrophy. Nature. 2014;514(7520):102–106. doi: 10.1038/nature13596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Viereck J., Kumarswamy R., Foinquinos A., et al. Long noncoding RNA Chast promotes cardiac remodeling. Science Translational Medicine. 2016;8(326) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf1475.326ra22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang K., Liu F., Zhou L. Y., et al. The long noncoding RNA CHRF regulates cardiac hypertrophy by targeting miR-489. Circulation Research. 2014;114(9):1377–1388. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.114.302476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jiang F., Zhou X., Huang J. Long non-coding RNA-ROR mediates the reprogramming in cardiac hypertrophy. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152767.e0152767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu L., An X., Li Z., et al. The H19 long noncoding RNA is a novel negative regulator of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Cardiovascular Research. 2016;111(1):56–65. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvw078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lv L., Li T., Li X., et al. The lncRNA Plscr4 controls cardiac hypertrophy by regulating miR-214. Molecular Therapy - Nucleic Acids. 2018;10:387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2017.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhu X.-H., Yuan Y.-X., Rao S.-L., Wang P. LncRNA MIAT enhances cardiac hypertrophy partly through sponging miR-150. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 2016;20(17):3653–3660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li Z., Wang X., Wang W., et al. Altered long non-coding RNA expression profile in rabbit atria with atrial fibrillation: TCONS_00075467 modulates atrial electrical remodeling by sponging miR-328 to regulate CACNA1C. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2017;108:73–85. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhu P., Yang M., Ren H., et al. Long noncoding RNA MALAT1 downregulates cardiac transient outward potassium current by regulating miR-200c/HMGB1 pathway. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2018;119(12):10239–10249. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Huang Z., Ding Y., Chen J., et al. Long non-coding RNAs link extracellular matrix gene expression to ischemic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovascular Research. 2016;112(2):543–554. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvw201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Qu X., Song X., Yuan W., et al. Expression signature of lncRNAs and their potential roles in cardiac fibrosis of post-infarct mice. Bioscience Reports. 2016;36(3) doi: 10.1042/BSR20150278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Huang S., Zhang L., Song J., et al. Long noncoding RNA MALAT1 mediates cardiac fibrosis in experimental postinfarct myocardium mice model. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2019;234(3):2997–3006. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Micheletti R., Plaisance I., Abraham B. J., et al. The long noncoding RNA Wisper controls cardiac fibrosis and remodeling. Science Translational Medicine. 2017;9(395) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aai9118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Piccoli M., Gupta S. K., Viereck J., et al. Inhibition of the cardiac fibroblast–enriched lncRNA Meg3 prevents cardiac fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction. Circulation Research. 2017;121(5):575–583. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.310624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tao H., Zhang J., Qin R., et al. LncRNA GAS5 controls cardiac fibroblast activation and fibrosis by targeting miR-21 via PTEN/MMP-2 signaling pathway. Toxicology. 2017;386:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Su J., Fang M., Tian B., et al. Atorvastatin protects cardiac progenitor cells from hypoxia-induced cell growth inhibition via MEG3/miR-22/HMGB1 pathway. Acta Biochimica et Biophysica Sinica. 2018;50(12):1257–1265. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmy133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jiang X., Zhang F., Ning Q. Losartan reverses the down-expression of long noncoding rna-nr024118 and cdkn1c induced by angiotensin ii in adult rat cardiac fibroblasts. Pathologie Biologie. 2015;63(3):122–125. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bandiera S., Pfeffer S., Baumert T. F., Zeisel M. B. miR-122 – A key factor and therapeutic target in liver disease. Journal of Hepatology. 2015;62(2):448–457. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Song K., Han C., Dash S., Balart L. A., Wu T. MiR-122 in hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus dual infection. World Journal of Hepatology. 2015;7(3):498–506. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i3.498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The materials in this manuscript are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.