Abstract

Maturation of inhibitory postsynaptic transmission onto motoneurons in the rat occurs during the perinatal period, a time window during which pathways arising from the brainstem reach the lumbar enlargement of the spinal cord. There is a developmental switch in miniature IPSCs (mIPSCs) from predominantly long-duration GABAergic to short-duration glycinergic events. We investigated the effects of a complete neonatal [postnatal day 0 (P0)] spinal cord transection (SCT) on the expression of Glycine and GABAA receptor subunits (GlyR and GABAAR subunits) in lumbar motoneurons. In control rats, the density of GlyR increased from P1 to P7 to reach a plateau, whereas that of GABAAR subunits dropped during the same period. In P7 animals with neonatal SCT (SCT-P7), the GlyR densities were unchanged compared with controls of the same age, while the developmental downregulation of GABAAR was prevented. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings of mIPSCs performed in lumbar motoneurons at P7 revealed that the decay time constant of miniature IPSCs and the proportion of GABAergic events significantly increased after SCT. After daily injections of the 5-HT2R agonist DOI, GABAAR immunolabeling on SCT-P7 motoneurons dropped down to values reported in control-P7, while GlyR labeling remained stable. A SCT made at P5 significantly upregulated the expression of GABAAR 1 week later with little, if any, influence on GlyR. We conclude that the plasticity of GlyR is independent of supraspinal influences whereas that of GABAAR is markedly influenced by descending pathways, in particular serotoninergic projections.

Introduction

Glycine and GABA activate chloride-permeable ionotropic glycine and GABAA receptors (GlyRs and GABAARs) (Legendre, 2001; Fritschy and Brünig, 2003). In immature spinal neurons, GABA- and glycine-evoked potentials are depolarizing and often excitatory and may even trigger action potentials (Takahashi, 1984; Wu et al., 1992; Gao et al., 1998; Ziskind-Conhaim, 1998; Jean-Xavier et al., 2006), because of a high intracellular Cl− concentration, which favors Cl− efflux through GABAA- or glycine channels. Maturation of inhibition in the rat spinal cord occurs within the perinatal period (Gao and Ziskind-Conhaim, 1995), during which the effect of GABA and glycine shifts from excitatory to inhibitory (Jean-Xavier et al., 2007; Delpy et al., 2008). Concomitantly, the density of glycinergic currents increases whereas that of GABAergic currents decreases. During this period, serotoninergic projections arising from raphe nuclei are among the earliest axons to reach the lumbar segments (Rajaofetra et al., 1989) (for review, see Vinay et al., 2000). Neonatal removal of these supraspinal influences by spinal cord transection prevents the shift from depolarizing to hyperpolarizing IPSPs in lumbar motoneurons (Jean-Xavier et al., 2006), suggesting that the brain plays a pivotal role in the maturation of Cl− homeostasis and therefore of inhibitory synaptic transmission. However, consequences of such a spinal lesion on the expression of receptors to inhibitory amino acids remain unknown.

GABAARs form pentameric complexes assembled from a family of at least 21 subunits (α1-6, β1-4, γ1-4, δ, ρ1-3, θ, π). The α subunits determines the kinetics of deactivation and/or desensitization of the channel and its pharmacological properties (Sigel et al., 1990; Gingrich et al., 1995). In the mature CNS, the α1β2γ2 combination represents the largest population of GABAARs, followed by α2β3γ2 and α3β3γ2, which are preponderant in spinal cord (Fritschy et al., 2003). The postnatal switch from fetal to adult expression of GABAAR subtypes has been studied in the rat brain (Fritschy et al., 1994), but remains to be investigated in the spinal cord. The predominant adult isoform of the GlyR is composed of three α1 and two β subunits (Legendre, 2001). In spinal motoneurons, the coexistence of GABA and glycine in axon terminals (Ornung et al., 1994; Taal and Holstege, 1994), their corelease (Jonas et al., 1998) and the colocalization of postsynaptic GABAA and GlyR (Baer et al., 2003) have been established. Both postsynaptic GABAA and GlyR at inhibitory synapses are aggregated in clusters whose formation is regulated by gephyrin, a submembrane scaffolding protein (Pfeiffer et al., 1984, Triller et al., 1985). In this study we combine quantitative immunocytochemistry and patch-clamp recordings to examine the effects of a neonatal spinal cord transection (SCT) on the developmental expression, organization and function of GABAARs and GlyRs. We demonstrate a differential plasticity of these receptors in response to a spinal cord transection: the plasticity of GlyRs is independent from supraspinal influences whereas that of GABAARs is markedly influenced by descending pathways, in particular, serotoninergic projections.

Materials and Methods

The experiments were performed on Wistar rats from the day of birth (postnatal day 0, P0) to P12. All surgical and experimental procedures were made to minimize animal suffering and conformed to both the guidelines from the French Ministry for Agriculture and Fisheries, Division of Animal Rights and the European guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals (Council Directive 86/6009/EEC).

Spinal cord transection

The spinal cord was transected at P0 or P5 as described previously (Norreel et al., 2003; Jean-Xavier et al., 2006). Rats were deeply anesthetized by hypothermia. After laminectomy, the spinal cord was transected at the T8–T10 level, and one to two segments of the cord were removed. The lesion cavity was then filled with sterile absorbable local hemostat Surgicoll (Johnson and Johnson). Skin incisions were sutured using fine thread and covered by Steri-Strips (3M Health Care). The completeness of spinal cord transection (SCT) was verified by anatomical magnetic resonance imagery (aMRI) (see supplemental Fig. 1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material) and/or by postmortem visual inspection of the lack of continuity between the spinal stumps. All MRI studies were performed 2 h after the lesion by means of a Bruker PharmaScan spectrometer (7 tesla magnet and 16 cm horizontal bore size) and a dedicated transmit–receive rat body-coil (linear birdcage coil with 62 mm inner diameter). Sagittal T2*-weighted images were performed at both P0 and P5 (FLASH gradient-echo sequence with TR/TE = 300/3.7 ms, flip angle = 30°, slice thickness = 0.5 mm, FOV = 19 mm, matrix = 256 × 256, number of averages = 4).

Retrograde labeling of triceps surae motoneurons

All the analyses were performed on a homogeneous population of retrogradely identified lumbar spinal motoneurons. Fast blue (FB, 0.5% in NaCl 0.9%, F-5756, Sigma, 3 μl) was injected bilaterally in the triceps surae (TS; ankle extensors) muscles of anesthetized animals at either P0, P5 or P9 for observations performed at P1, P7 and P12, respectively. P0 and P5 animals were anesthetized by hypothermia whereas at P9, anesthesia was induced by isoflurane inhalation (AErrane, DDG9623, Baxter). After FB injection, the animals were warmed until normal breathing had recovered, and returned to their mother. FB-retrograde labeling was restricted to a lateral column of spinal motoneurons located in the L4 lumbar segment.

Pharmacological treatments

The activation of serotonergic 5-HT2 receptors (5-HT2-Rs) was performed by intraperitoneal administration of 2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine hydrochloride (DOI; Sigma) a 5-HT2-R agonist that crosses the blood-spinal cord barrier. From P4 to P7, transected (n = 6) animals received daily injections of 0.15 mg/kg DOI (Kim et al., 1999; Norreel et al., 2003) diluted in 50 μl of NaCl. A control group of 6 transected animals received daily intraperitoneal injections of 50 μl of NaCl.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistology was processed on a total of 78 Wistar rats at P1, P7 and P12. The first group (P1, n = 17 rats) was composed of control nonoperated animals. The second group of 7-d-old animals included pups whose spinal cord was transected on the day of birth (SCT-P7, n = 20) and controls (Control-P7, n = 13). Similarly, animals of the third age group (P12) were either intact (Control-P12, n = 11) or cord-transected (SCT-P12, n = 17) 1 week before (i.e., P5).

The animals were deeply anesthetized by hypothermia at P1 and P7, or by isoflurane inhalation (P12 rats) and killed by decapitation. The lumbar spinal cord [L1-L6] was rapidly excised, immersed for 1 h in 20% sucrose and then embedded in capsules containing Tissutech (Sakura) quickly frozen by immersion in 100% ethanol kept at − 80°C. Transverse spinal cord sections (20 μm-thick) were cut with a cryostat (Microm) and mounted onto gelatinized slides. They were immersed in freshly depolymerized 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.15 m phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) for 30 min and rinsed in PBS.

Antibodies and their dilutions

Antibodies against GABAARα1, α2, α3, and α5 subunit (respective dilutions: 1:20,000, 1:10,000, 1:4000, 1:4000) raised in rabbit were a kind gift from J. M. Fritschy (Institute of Pharmacology and Toxicology, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland) (Fritschy and Mohler, 1995; Fritschy et al., 1998; Sassoè-Pognetto et al., 2000). Immunocytochemical characterization of these antibodies has been described previously and their specificity demonstrated by means of mutant mice lacking the α1, α2, α3, or α5 subunit genes (Günther et al., 1995; Yee et al., 2005; Kralic et al., 2006). Immunocytochemistry showed a complete absence of immunolabeling of the GABAAR α1, α2, α3, and α5 subunit, in each respective mice (Kralic et al., 2006). The monoclonal mouse antibody bd-17 (US Biological, bovine, cat # G1016; 1:400) directed against both β2 and β3 subunits of GABAARs, recognize the major GABAAR subtypes in the CNS (McKernan and Whiting, 1996) expressed during postnatal development (Alvarez et al., 1996) and in adult spinal cord motoneurons (Fritschy et al., 1994; Bohlhalter et al., 1996). The mature form of the GlyR, GlyRα1, was detected with either the monoclonal antibody mAb2b (Connex, mouse, 1:80, catalog # 28 120 501-0 and Synaptic Systems (SySy), mouse 1:250, catalog # 146 111) or the polyclonal antibody pAb2b (Millipore Bioscience Research Reagents, rabbit, 1:100; catalog # AB5052), depending on the other primary antibodies used for double immunofluorescence staining (Pfeiffer et al., 1984; Schröder et al., 1991; Liu and Wong-Riley, 2002; Baer et al., 2003). Both monoclonal or the polyclonal antibodies against GlyRα1 displayed punctuate fluorescence outlining the cell bodies and dendrites of motoneurons, and a quantitative analysis showed 95% colocalization of the fluorescent clusters when using both antibodies (Lorenzo et al., 2007).

The expression of the α2 subunit, the embryonic form of GlyR, which rapidly decreases after birth in the rat spinal cord (Legendre, 2001) has not been considered. The presynaptic and postsynaptic sides of the GlyR were studied using antibodies against the neuronal glycine transporter GlyT2 and the postsynaptic anchoring protein Gephyrin (Pfeiffer et al., 1984; Kirsch et al., 1993), respectively. The antibody against GlyT2 (Millipore Bioscience Research Reagents, guinea pig antisera, 1:20,000), has been shown to be a reliable marker of glycinergic inputs (Poyatos et al., 1997; Spike et al., 1997). The antibody against gephyrin (mAb7a, 1:400; Synaptic Systems) raised against purified rat glycine receptors was highly specific for postsynaptic aggregates (Pfeiffer et al., 1984; Kirsch et al., 1993), and showed an absence of immunolabeling in gephyrin knock-out mice (Kneussel et al., 1999; Fischer et al., 2000).

For double immunofluorescence staining, sections were incubated overnight at 4°C in a mixture of primary antibodies raised in different hosts, diluted in PBS containing 2% normal donkey serum, 0.2% Triton X100. After being washed in PBS (3 × 10 min), the sections were immersed in a solution containing a mixture of fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibodies (Alexa 488, 1:800, Invitrogen; Cy3, 1:500, Jackson ImmunoResearch; with respective emission waves at 518, 575 nm) diluted in PBS containing 2% normal donkey serum for 1 h, at room temperature. Sections were then rinsed and coverslipped in immunomount medium (Vector Laboratories). All secondary antibodies were raised in donkey and affinity-purified to prevent species cross-reactivity. Control experiments consisted of omitting successively one of the primary antibodies in the double-staining combinations. They resulted in a complete absence of cross-reactivity between different immunoreactions.

Confocal microscopy and quantitative analysis

The patterns of immunolabeling were analyzed by means of a laser scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 510 META) at low (20×) or high magnification (Plan Apochromat 63× 1.4 (N.A.) oil-immersion objective). At high magnification, only FB-retrogradely labeled TS motoneurons with visible nuclei were scanned, and for each soma, a stack of 4–7 confocal images including the nucleus was collected (1024 × 1024 pixels spaced 1 μm apart). Dendrites clearly emerging from the cell body and that could be followed up to 200 μm from the soma were also analyzed. The optical sections were digitally zoomed to 2× or 2.4× (pixel size = 0.0049 μm2 or 0.0036 μm2, respectively). Triple fluorescent labelings were captured using frame-channel mode to avoid any cross talk between the channels. Each optical section resulted from two scanning averages. Excitation of the fluorochromes was performed with a diode laser set at 405 nm to detect FB, an argon ion laser set at 488 nm to detect Alexa Fluor 488, and a helium/neon laser set at 575 nm to detect Cy3.

As previously described (Lorenzo et al., 2006, 2007), GABAA and Glycine receptor subunits, GlyT2 and gephyrin clusters were defined based on size. They had to be composed of at least four adjacent pixels and did not exceed 12 pixels, which prevented double counting of the same clusters in adjacent images 1 μm apart. The receptor density of each type of clustered receptor was determined by dividing the total number of fluorescent clusters outlining the motoneuron by its perimeter, measured by using the overlay tracing function of the Zeiss software (version 4). When the membrane immunolabeling was more diffuse (use of bd-17 antibody), the surface of the immunolabeled motoneuronal membrane was delimited by overlay and the averaged pixel intensity within this surface was quantified using the FluoView software (version 5).

Electrophysiology

Slice preparation.

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were performed at P7 on control (Control-P7, n = 5) and cord-transected rats (SCT-P7, n = 4). Animals were anesthetized by hypothermia. Quickly after decapitation, the spinal cord was isolated in cold (4°C) and oxygenated (95% of O2 and 5% CO2)sucrose solution of the following composition (in mm): 232 sucrose, 3 KCl, 1.25 KH2PO4, 4 MgSO4, 0.2 CaCl2, 26 NaHCO3, 25 d-glucose (pH 7.4, 320 mOsm). After a section at the L3 level, the lumbar spinal cord was introduced into a 1% agar solution and quickly cooled. Transverse slices (350 μm) through the L4-L5 lumbar segments were obtained and transferred into the holding chamber filled with oxygenated ACSF (in mm: 120 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 1.3 MgSO4, 1.2 CaCl2, 25 NaHCO3, 40 d-glucose; 31°C ± 2°C; pH 7.4). One hour after dissection, slices were placed in the recording chamber filled with oxygenated ACSF and maintained at 30−32°C (2 ml/min).

Data acquisition.

Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings were performed from large motoneurons (Multiclamp 700B amplifier, Digidata 1322A, pClamp 9 software, Molecular Devices). Slices were submerged in a chamber mounted on a fixed-stage microscope (Eclipse E600FN, Nikon, 40× water-immersion lens). Cells were visualized using differential interference contrast (DIC) optics associated with an infrared-sensitive CCD camera and displayed on a video monitor. Patch pipettes were made from borosilicate capillaries (1.5 mm OD, 1.12 mm ID; World Precision Instruments) by means of a Sutter P-97 puller (Sutter Instruments Company). The resistance of electrodes was 2.5–4 MΩ when filled with an intracellular solution containing the following (in mm): 110 Cs Chloride, 30 K+-gluconate, 5 NaCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 0.5 EGTA, 2 ATP, 0.4 GTP, pH 7.3 (280–290 mOsm). The series resistances that exceed 12 MΩ were discarded. Holding potential was −70 mV. Signal was filtered at 4 kHz and acquired at 10 kHz. To isolate miniature spontaneous IPSCs (mIPSCs), recordings were performed in the presence of tetrodotoxin (TTX, 1 μm) and kynurenic acid (1.5 mm). GABAergic and glycinergic mIPSCs were subsequently isolated by adding either strychnine (1 μm) or bicuculline methiodide (20 μm) to the ACSF solution. All pharmacological tools were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich except TTX purchased from Tocris Bioscience.

Data analysis.

Data analysis was performed with the Minianalysis software (Synaptosoft). No difference in the background noise (∼3–4 pA) was observed between control animal and spinal cord transected group. Therefore, a threshold value (∼6–8 pA) was set for event detection at two-fold the baseline noise. Cells with unstable baseline noise were discarded. All events were considered for frequency measurements. For the two other analyses (amplitude and decay time constant), only events starting from baseline were considered (superimposed events were discarded). The decay phase of pharmacologically isolated GABAergic and glycinergic events were best fitted by a single mono-exponential curve whereas mixed GABAA and glycinergic events were best fitted by a biexponential decay. Therefore, in normal ACSF, those events that had a biexponential decay (as revealed by the software) were classified as mixed events. Those with a mono-exponential decay were either GABAergic or glycinergic. Benzodiazepines, which slow the decay of GABAAR-mediated mIPSCs, are sometimes used to improve the identification of GABAergic and glycinergic events on the basis of kinetic differences (Gao et al., 2001). These drugs were not used in the present study because their effects may be different in SCT animals compared with controls. Therefore we used the amplitude and the decay time constant (τ) to distinguish between GABAergic and glycinergic mIPSCs. Plotting τ against the current amplitude for pharmacologically isolated mIPSCs confirmed that GABA and glycinergic events had different characteristics: small amplitude/slow decay and large amplitude/fast decay, respectively (see Fig. 4A,B3). We determined a line that separates the two populations such that τ above or below this line would enable to identify the event as being GABAergic or glycinergic, respectively, with the smallest error (<5%). The line with the following equation was used in the analysis of mIPSCs in control animals:

Only 2.2% of GABAergic events and 4.8% of glycinergic events were below and above this line (errors). Because pharmacologically isolated mIPSCs had not exactly the same kinetics after SCT compared with controls (see Results), the line used for cord-transected animals had the following equation:

The percentages of errors in classifying GABAergic and glycinergic events based on the value of τ relative to this line were 2.6% and 3.0%, respectively. These two lines were used to classify as GABAergic or glycinergic the events characterized by a mono-exponential decay in ACSF.

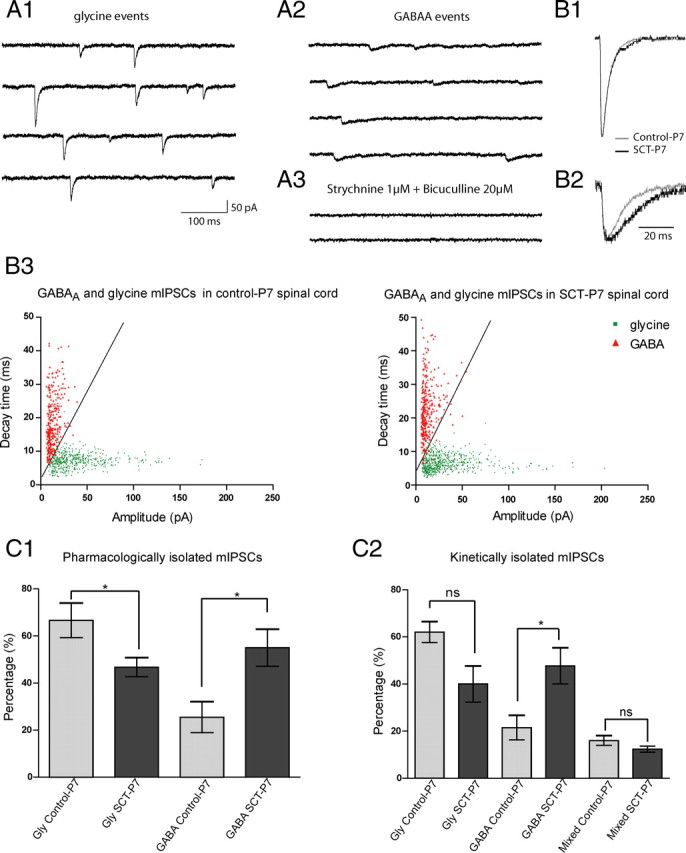

Figure 4.

Increase of the proportion of GABAergic but not glycinergic or mixed GABA/Gly events after SCT. A1, Miniature glycinergic events were recorded after 20 min of bicuculline methiodide superfusion (20 μm). A2, GABAergic events were recorded after superfusion of strychnine (1 μm) during 15 min. A3, All mIPSCs were blocked by cocktails of strychnine and bicuculline. B1, Means of glycine events from control-P7 (light gray trace, 134 events) and SCT-P7 (dark gray trace, 112 events) motoneurons were superimposed and normalized. B2, Means of GABA events from control-P7 (light gray trace, 53 events) and SCT-P7 (dark gray trace, 39 events) were superimposed and normalized. B3, Cloud point representation of GABA (red triangles) and glycine (green dots) events after application of strychnine or bicuculline as a function of the amplitude and decay time of each event from control-P7 and SCT-P7 (517 glycine events in control-P7 (n = 5) and 646 glycine events in SCT-P7 (n = 6); 308 GABA events in control-P7 (n = 5) and 329 in SCT-P7 (n = 4)). C1, Histogram showing the percentages of pharmacologically isolated glycine and GABA events, relative to the total number of mIPSCs recorded before drug application in the same motoneurons, in control-P7 (light gray bars) and in SCT-P7 (dark gray bars). C2, Histogram of percentage of glycine, GABA and mixed GABA/glycine events as function of kinetics, in control-P7 (light gray bars) and after SCT-P7 (dark gray bars).

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed as follows using the Sigmastat software (SPSS). The nonparametric one-way ANOVA (Kruskal–Wallis) was performed with a Dunn's post test for multiple comparisons between control animals and SCT and/or pharmacologically treated rats. Data were expressed as medians ± QD (quartile deviation; Kendall and Buckland, 1960). The Wilcoxon matched-pairs-signed-ranks test was used to test for differences between receptor densities on cell bodies and dendrites. Statistical significance was taken at p < 0.05. For electrophysiological data, all results are given as means ± SEM. The Mann–Whitney test was used to compare two groups of data that followed non-Gaussian distributions (Prism 5; GraphPad Software Inc.).

The analysis in immunohistochemistry was performed on 1623 motoneurons retrogradely labeled and scanned at high magnification (63×) in confocal microscopy. Every dual immunolabeling experiment was performed on histological sections from at least 3 transected and 3 age-matched control animals. The number of analyzed motoneurons is indicated in the bar histograms.

Results

Developmental expression of GlyRs and GABAARs on TS motoneurons

GlyRα1

The efficiency of glycinergic transmission depends on both (1) the proper alignment of presynaptic axon terminals and the postsynaptic receptor and (2) the anchoring of the membrane receptors to gephyrin (Schneider Gasser et al., 2006). Therefore, we analyzed the development of the glycinergic synapse at presynaptic and postsynaptic levels, by quantifying the association of the GlyRα1 subunits with the presynaptic transporter GlyT2, and their colocalization with the anchoring protein gephyrin. All three immunolabelings (GlyRα1, GlyT2 and gephyrin) resulted in bright punctuate fluorescence (Fig. 1) which enabled to quantify the density of GlyRα1 on the membrane of TS motoneurons, and the rate of colocalization with GlyT2 or gephyrin. Immunofluorescent clusters of GlyRα1 and GlyT2 were adjacent, in line with a localization of GlyT2 at some distance from the glycine-releasing active zones (Zafra et al., 1995; Poyatos et al., 1997; Spike et al., 1997; Mahendrasingam et al., 2000). In contrast the dual immunolabeling of GlyRα1 and gephyrin resulted in overlapped clusters suggesting the closeness of both antigens.

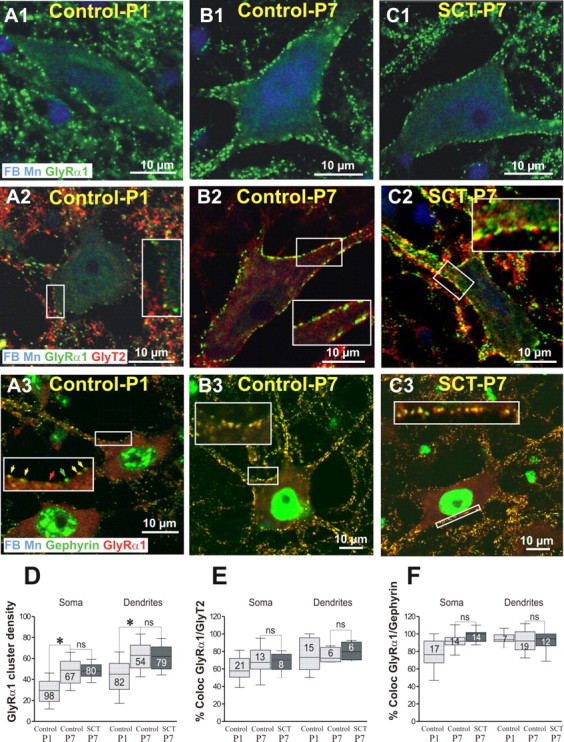

Figure 1.

The developmental upregulation of GlyR is not affected by a neonatal SCT. Dual or triple labeling of GlyRα1 with GlyT2 and gephyrin on fast blue (FB) retrogradely identified TS motoneurons. The experiments were performed on control rats at P1 (control-P1), P7 (control-P7), and 7 d after neonatal SCT (SCT-P7). Each panel corresponds to a single optical section. In each horizontal series, the antigens detected (and their color of detection) are indicated in the lower part of the left panels. In control-P1 (A1), the density of GlyRα1 reached 29.5 clusters per 100 μm on the cell bodies, 45 on the dendrites (Whiskers Box in D). At this stage, 60% of the clusters of GlyRα1 faced GlyT2-immunoreactive axon terminals on the cell bodies, 75.1% on the dendrites (A2, E), and >75% of the GlyRα1 clusters were colocalized with gephyrin on the cell bodies, 94.8% on the dendrites (A3, F). On motoneurons of control-P7 (B1), the rate of expression of the GlyRα1 significantly increased compared with control-P1 and their density reached 48.9 on the cell bodies, 62.9 on the dendrites (D; Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric test, P1 vs P7, *p < 0.05). At this stage, the association of GlyRα1 with GlyT2 reached 69.4% on the soma, 75.6% on the dendrites (B2, E), while the colocalization of GlyRα1 with gephyrin was almost total on both soma (91.8%) and dendrites (91.7%; B3, F). Seven days after neonatal SCT (SCT-P7), the density of GlyRα1-immunopositive clusters remained remarkably similar (C1) to those quantified on motoneurons of age matched-controls, on both cell bodies and dendrites (D; Control-P7 vs SCT-P7, p = 0.99 for both soma and dendrites). The neonatal SCT did not significantly affect the rate of association of GlyRα1 with GlyT2 on both cell bodies (68.1%) and dendrites (80.3%) compared with P7-control animals (C2, E; Control-P7 vs SCT-P7; p = 0.11 for soma and 0.8 for dendrites). Similarly, on SCT-P7 rats, the rate of colocalization of GlyRα1 with gephyrin (C3) did not significantly change compared with P7 animals on both soma (98.05%) and dendrites (91.04%; F; Control-P7 vs SCT-P7, p = 0.6 for soma and 0.88 for dendrites).

At P1 (Fig. 1A1), the membrane of TS motoneurons was already enriched with immunofluorescent clusters of GlyRα1. Their density was higher on the dendrites than on the cell bodies (Fig. 1D, histograms). At this stage, 60% and 75% of the clusters of GlyRα1 faced GlyT2-immunoreactive axon terminals on cell bodies and dendrites, respectively (Fig. 1A2,E), and >75% of the GlyRα1 clusters were colocalized with gephyrin on the cell bodies (94.8% on the dendrites; Fig. 1A3,F). At P7, the rate of expression of the GlyRα1 had significantly increased compared with P1 (Fig. 1B1,D). Their rates of association with GlyT2 increased compared with P1 (Fig. 1B2,E) and the large majority of GlyRα1 clusters were colocalized with gephyrin (Fig. 1B3,F).

GABAARα

Immunohistochemical experiments were performed using antibodies raised selectively against the α1, α2, α3, and α5 subunits of the GABAAR. Every GABAAR subunit was covisualized with GlyRα1, used as a membrane indicator. The immunolabeling for the α1, α2, and α3 subunits of the GABAAR resulted in a membrane punctuate fluorescence, associated with a homogeneous cytoplasmic labeling in agreement with previous observations (Fritschy et al., 1994; Bohlhalter et al., 1996; Geiman et al., 2002).

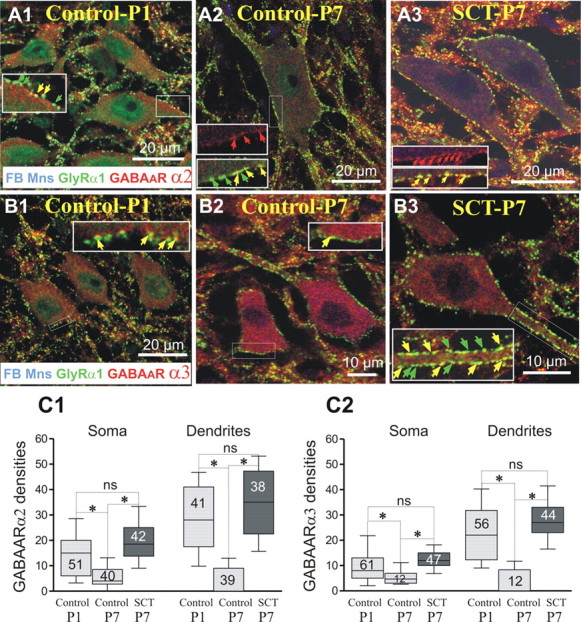

GABAARα2

In control-P1 pups, immunopositive clusters of GABAARα2 subunit were substantially expressed on the membrane of the motoneurons (Fig. 2A1) with median densities approximately twice higher on dendrites than on somata (28 vs 15 clusters per 100 μm; Fig. 2C1). Most of them were colocalized with GlyRα1 (84% and 82.6% on cell bodies and dendrites, respectively). In control-P7, only a few GABAARα2 clusters remained expressed on the motoneuronal cell bodies (Fig. 2A2), and they were almost absent on the dendrites (Fig. 2C1). Their rate of colocalization with GlyR clusters decreased compared with P1, to 46.7% on the cell bodies and 31.3% on the dendrites.

Figure 2.

Lack of a developmental downregulation of the expression of GABAARα2 and GABAARα3 after neonatal SCT. Triple fluorescent labeling of GlyRα1 and GABAARα2 or GABAARα3 on FB retrogradely identified TS motoneurons. Images are single optical plan sections. In each horizontal series, the antigens detected (and their color of detection) are indicated in the lower part of the left panels. In control-P1 pups, immunopositive clusters of GABAARα2 were expressed at the membrane of the motoneurons (A1) with densities of 15 clusters per 100 μm on the soma, 28 on the dendrites (C1, histograms). In control-P7, only a few GABAARα2 clusters were still expressed on the motoneuronal membrane (A2), and their density significantly dropped down on both cell bodies and dendrites (C1; 4 and 0.1 clusters per 100 μm, respectively; Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric test, control-P1 vs control-P7; *p < 0.05 in both soma and dendrites). After neonatal SCT, the expression of the GABAARα2 did follow on a normal developmental decrease. Indeed, densities were significantly higher than in control-P7 (18.5 on the somata, 35 on the dendrites; control-P7 vs SCT-P7: p < 0.05 for both compartments) and very similar to the values measured in control-P1 (A3, C2; P1 vs SCT-P7; p > 0.05, on both somata and dendrites). A similar scenario was observed concerning GABAARα3: In control-P1 the median density of GABAARα3 reached 8 on the soma, 22 on the dendrites (B1, C2). In control-P7, GABAARα3 densities significantly decreased (B2) to 4 ± 17 on the soma, and 0.5 ± 4 on the dendrites (p < 0.05). After neonatal SCT the expression of the GABAARα3 did not follow a normal developmental decrease (B3) and their densities (12 on soma, 27 on the dendrites) were significantly higher than in control-P7 (C2; control-P7 vs SCT-P7, p < 0.05, on both soma and dendrites). Whiskers above and below the box indicate the 90th and 10th percentiles; the number of motoneurons analyzed is indicated in each box.

GABAARα3

In control-P1, the density of GABAARα3 was ∼8 and 22 on cell bodies and dendrites, respectively (Fig. 2B1). The large majority of the GABAARα3 (82% on both somata and dendrites) were colocalized with GlyRα1. At P7, these densities significantly decreased (Fig. 2B2,C2; p < 0.05).

GABAARα1 and GABAARα5 subunits were not expressed on the membrane of TS motoneurons in control-P1 and -P7 animals (supplemental Fig. 2A1,2; B1,2). The lack of GABAARα1 on spinal motoneurons corroborates data obtained in adults (Bohlhalter et al., 1996) in line with a preferential expression of this subunit on specific brainstem motoneurons (Lorenzo et al., 2006), whereas the absence of GABAARα5, which are classically described as extrasynaptic (Crestani et al., 2002; Fritschy and Brünig, 2003; Walker, 2008), suggest a weak contribution of a tonic inhibitory transmission in TS motoneurons of adult rats.

Differential effects of a neonatal SCT on developmental expression of glycine and GABAA receptors

GlyαR1

In SCT-P7 rats (Fig. 1C1,D), the densities of GlyRα1-immunopositive clusters on both cell bodies and dendrites remained remarkably close to those quantified in control-P7 motoneurons. In addition, the neonatal SCT affected neither the rate of association of GlyRα1 with GlyT2 (Fig. 1C2,E) nor the rate of colocalization of GlyRα1 with gephyrin (Fig. 1C3,F).

We further determined the average GlyRα1 cluster size on the membrane of TS motoneurons of Control-P7 versus SCT-P7 (analysis of 484 clusters from 6 motoneurons in each series). The averaged GlyRα1 cluster size was not significantly different in control-P7 (0.36 μm2) and SCT-P7 animals (0.38 μm2, p = 0.71; Mann–Whitney rank sum test, data not shown).

GABAARα2

After neonatal SCT, the expression of the GABAARα2 did not undergo the normal developmental decrease. Indeed, median densities were significantly higher than at P7 (Fig. 2A3,C1; p > 0.05) on both somata and dendrites and very similar to the values measured at P1. In addition, as observed in control-P1, a majority of GABAARα2 clusters colocalized with GlyRα1 (90.8% on the cell bodies and 81.4% on the dendrites).

GABAARα3

Similarly to the GABAARα2, the age-related downregulation of the GABAARα3 was prevented by the neonatal SCT (Fig. 2B3) such that median densities in SCT-P7 animals were significantly larger than in controls of the same age (Fig. 2C2; p < 0.05 in both compartments), close to those in control-P1 (Fig. 2C2; p > 0.05). The majority of GABAARα3 clusters remained colocalized with GlyRα1 (86.7% on the cell bodies and 68.6% on the dendrites).

GABAARα1 and GABAARα5

Similarly to P1- and P7-control animals, an absence of membrane motoneuronal immunolabeling for both GABAARα1 and GABAARα5 subunits was evidenced 7 d after neonatal SCT (supplemental Fig. 2C1,2). However, in transected animals, GABAARα1-immunopositive fibers were detected within the motoneuronal area most likely originating from an increased number of GABAARα1-immunopositive interneurons observed medially to this area.

A neonatal SCT induces significant changes in GABAergic mIPSCs but not in glycinergic mIPSCs

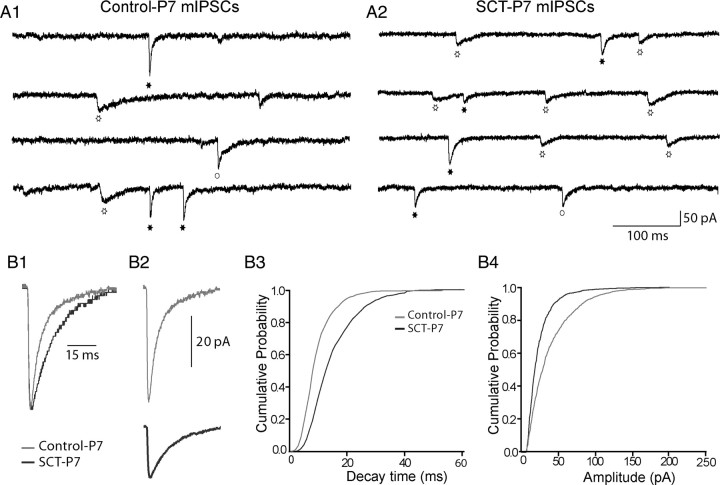

Electrophysiological experiments were performed to investigate the functional correlate of these observations. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were performed from motoneurons in the L4-L5 lumbar segments isolated from control-P7 and SCT-P7 animals. The frequency of mIPSCs in our conditions (32°C) was 11.88 ± 2.4 Hz (Table 1) and did not change significantly after neonatal SCT (8.86 ± 2.39; p > 0.05; Table 1). A global analysis of all mIPSCs revealed an increase (∼50%) of the decay time constant [τ: mean = 10.16 ± 0.86 ms vs 15.61 ± 1.25 ms in control (n = 8) and SCT group (n = 9), respectively; p < 0.01, U = 8.00, Mann–Whitney test; Fig. 3B1,3; Table 1] and a nonsignificant trend toward a reduction of the amplitude of mIPSCs after SCT (mean = 36.33 ± 5.38 pA vs 25.03 ± 3.94 pA in control and SCT group, respectively; p > 0.05, U = 18.00, Mann–Whitney test; Fig. 3B2,4; Table 1). Cumulative distribution of mIPSCs decay times shifted to the right after SCT, indicating slower decay kinetics (Fig. 3B3), whereas the cumulative curve of amplitudes after SCT was slightly shifted to the left showing an overall decrease of event sizes (Fig. 3B4).

Table 1.

A neonatal spinal cord transection differentially changes the GABAergic and glycinergic mIPSC properties of motoneurons recorded at P7

| Type of inhibition | Control lumbar MNs |

Transected lumbar MNs |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| τ (ms) | Ampl (pA) | Freq (Hz) | n | τ (ms) | Ampl (pA) | Freq (Hz) | n | |

| Control | 10.16 ± 0.86 | 36.33 ± 5.38 | 11.88 ± 2.4 | 8 | 15.61 ± 1.25** | 25.03 ± 3.94 | 8.86 ± 2.39 | 9 |

| GABA | 17.03 ± 1.22 | 15.27 ± 2.31 | 3.618 ± 0.51 | 5 | 21.92 ± 0.58* | 11.9 ± 1.9 | 4.157 ± 1.08 | 4 |

| Glycine | 7.164 ± 0.527 | 43.91 ± 7.58 | 5.073 ± 0.63 | 5 | 6.356 ± 0.65 | 40.02 ± 7.56 | 7.818 ± 2.28 | 6 |

Statistical significance was assessed by a Mann–Whitney test.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. n = number of motoneurons.

Figure 3.

Deactivation decay time of global mIPSCs increase after SCT. A1, Example of mIPSCs from a motoneuron of control-P7 with glycine events (filled star), GABAA events (open star), and mixed GABA/glycine events (open circle). A2, Example of mIPSCs from SCT-P7 motoneuron. B1, Normalized mean of mIPSCs from the control-P7 motoneuron illustrated in A1 (light gray trace, mean of 124 events) and from the SCT-P7 motoneuron illustrated in A2 (dark gray trace, mean of 114 events). B2, Mean of mIPSCs from the control-P7 motoneuron illustrated in A1 and from the SCT-P7 motoneuron illustrated in A2. B3, B4, Cumulative probability function of decay times and amplitudes for the individual events from control-P7 group (light gray traces; n = 2051 events from 8 motoneurons) and from SCT-P7 group (dark gray traces; n = 2099 events from 9 motoneurons). The mean decay time increased significantly after SCT [10.16 ± 0.86 ms in control group (n = 8) and 15.61 ± 1.25 ms in SCT group (n = 9); p < 0.01], whereas a nonsignificant trend toward a reduction of the amplitude of mIPSCs was observed after SCT (36.33 ± 5.38 pA vs 25.03 ± 3.94 pA in control and SCT group, respectively; p > 0.05).

GABAergic and glycinergic events were isolated pharmacologically by adding strychnine or bicuculline, respectively (Fig. 4A1–3), and the kinetics of these events were analyzed. Our findings showed that τ of GABAAR-mediated mIPSCs was increased after SCT (17.03 ± 1.22 ms, n = 5 and 21.92 ± 0.58 ms, n = 4 in control-P7 and SCT-P7 animals, respectively; p < 0.05, U = 0.5, Mann–Whitney test; Fig. 4B2; Table 1). The amplitude of GABA events decreased slightly after SCT (15.27 ± 2.31 pA vs 11.9 ± 1.9 pA; p > 0.05, U = 7.00; Table 1). For glycine events, both τ and the amplitude were unaffected by neonatal SCT (Fig. 4B1; Table 1).

To determine whether the respective proportions of GABAergic and glycinergic events were changed after SCT, we first calculated the percentage of pharmacologically isolated events, relative to the total number of mIPSCs recorded before drug application in the same motoneurons. The proportion of glycinergic events decreased (66.66 ± 7.37% vs 45.43 ± 3.59%; p < 0.05, U = 2.00, Mann–Whitney test) whereas that of GABAAR-mediated mIPSCs increased in animals with neonatal SCT (25.48 ± 6.61% vs 55.03 ± 7.87%; p < 0.05, U = 0.00, Mann–Whitney test) (Fig. 4C1). We performed a second analysis based on the kinetics of mIPSCs recorded in ACSF (see Materials and Methods for the discrimination between the three types of currents). This method confirmed the >100% increase in the proportion of GABAergic events (21.53 ± 5.247% vs 47.68 ± 7.674% p < 0.05; U = 11.00; Fig. 4C2) and the ∼30% reduction in the percentage of glycinergic events (though not significant because of a large variability among cells) in SCT-P7 animals, compared with control-P7. Note that the proportion of pharmacologically isolated mIPSCs was larger than those calculated from the kinetics because they included both pure GABA or glycine events and mixed GABA/glycine events. The proportion of the latter events was not affected by SCT (Fig. 4C2). To summarize, these electrophysiological experiments are supporting the immunohistological results showing that GABAARs are upregulated after neonatal spinal cord transection, compared with controls of the same age.

A SCT performed at P5 upregulates GABAARs

We next addressed the question of suppressing descending afferences several days after birth, when the levels of GABAARs are already low in the lumbar cord, and when the reversal potential of IPSPs is significantly more negative than at birth (Stil et al., 2009). Four rats were transected at P5 and the spinal cords were processed for immunohistochemistry 7 d later (SCT-P12) together with tissues from 3 control-P12 animals. For both groups, GlyRα1 was covisualized with either GABAARα2 or GABAARα3.

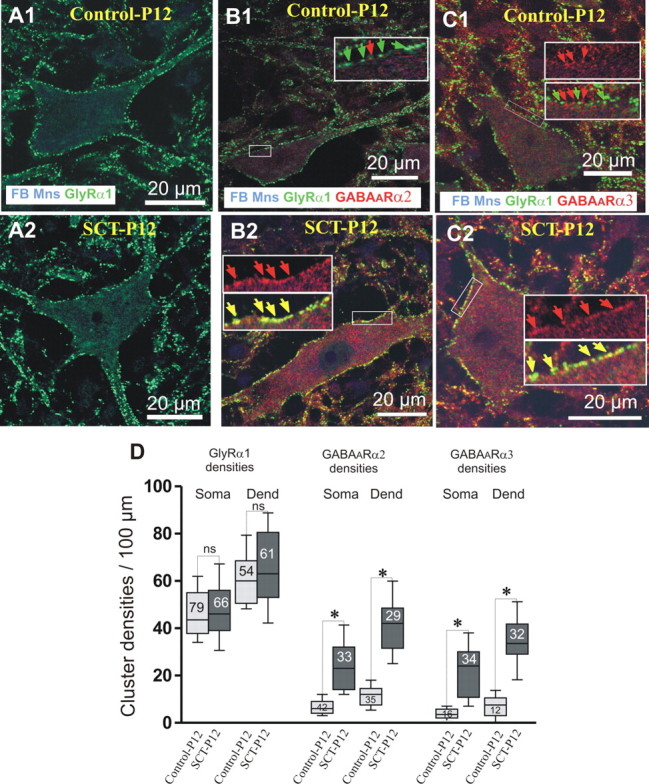

GlyRα1

In control-P12, the densities of GlyRα1 (47 ± 9.52 on cell bodies, 60.7 ± 8 on the dendrites, Fig. 5A1) were similar to those observed in control-P7 (compare Figs. 1D, 5D; p = 0.99 for both somata and dendrites), in line with a glycinergic transmission being already mature at P7. In SCT-P12 animals, these densities remained unchanged (Fig. 5A2) in both compartments (Fig. 5D; p = 1 and 0.99 for somata and dendrites, respectively).

Figure 5.

Effects of an SCT made on P5, on the expression of GABAAR and GlyR. To differentiate maturational and reactional postlesional effects, SCT was made at P5, when the levels of GABAARs are already low in the lumbar cord. The effects of the lesion on the motoneuronal immunoexpression of GlyRα1 (green), GABAARα2, and GABAARα3 (red) were compared on fast blue-labeled motoneurons of control-P12 and on transected SCT-P12 animals. For each column, the combination of antibodies used is mentioned in the lower part of the upper picture. A1, A2, The membrane densities of GlyRα1s observed on TS motoneurons of SCT-P12 animals remained unchanged compared with control-P12 rats (D: control-P12 vs SCT-P12: p = 1 and p = 0.9 for soma and dendrites, respectively). B1, B2, On SCT-P12 rats, the cluster densities of GABAARα2 significantly increased compared with control-P12. C1, C2, Similarly, the GABAARα3 densities were significantly higher on motoneurons of SCT-P12 rats than in control-P12 (D: control-P12 vs SCT-P12: p < 0.05 for both somata and dendrites). Whiskers above and below the box indicate the 90th and 10th percentiles; the number of motoneurons analyzed is indicated in each box. (Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric test, *p < 0.05; ns, nonsignificant).

GABAARα2

The density of GABAARα2 on TS motoneurons was, in control-P12 (Fig. 6B1), as low as in control-P7 (compare Figs. 2C1, 5D; p = 0.97 and 0.52 on somata and dendrites, respectively). In SCT-P12 rats, the densities significantly increased, compared with P12 (Fig. 5B2,D; p < 0.05 on both compartments). These cluster densities on SCT-P12 motoneurons were significantly higher than those in control-P1 (p < 0.05, somata and dendrites).

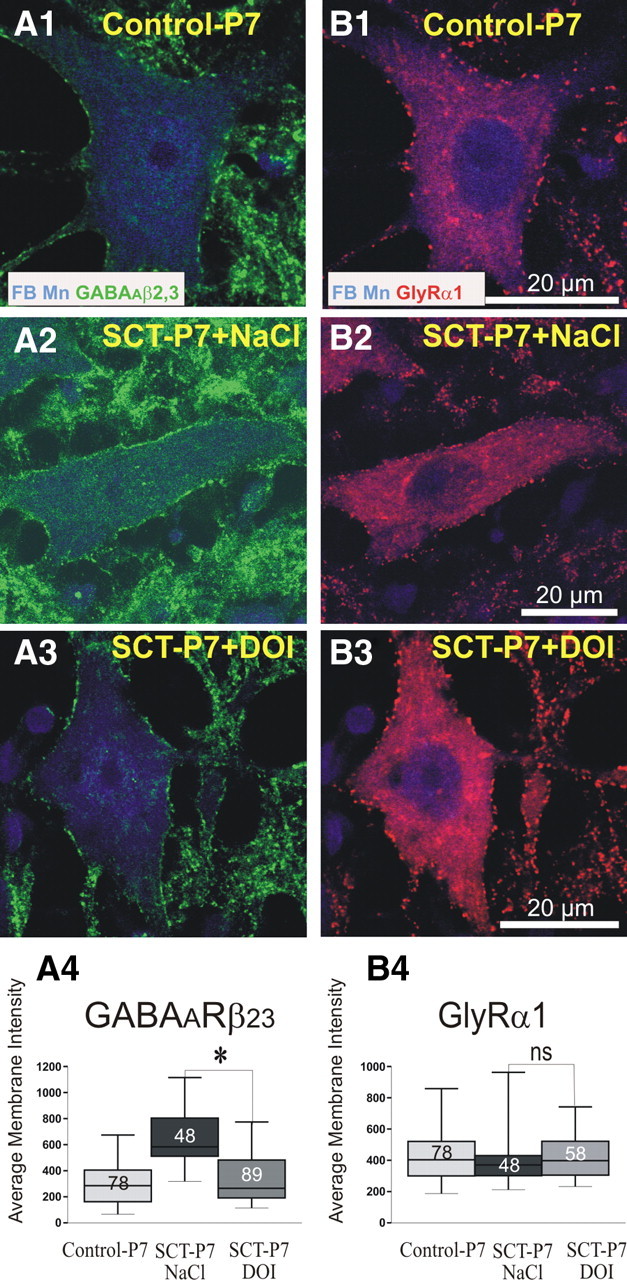

Figure 6.

Effects of the activation of 5-HT2Rs on the maturational expression of GABAAR subunits and GlyR. Dual immunofluorescent labeling of GABAARβ2,3 subunits (left, Alexa 488, green) and GlyRα1 (right, Cy3, red) on FB retrogradely labeled TS motoneurons of control-P7 rats (A1, B1), transected SCT-P7 rats treated with NaCl (A2, B2, SCT-P7 + NaCl), and SCT-P7 rats treated with DOI (A3, B3, SCT-P7 + DOI). Images are single optical plan sections. The antigens labeled are indicated in the lower part of the top. The average membrane fluorescence intensity of GABAARβ2,3, which increased on motoneurons of SCT-P7-NaCl rats compared with control-P7, significantly dropped down on motoneurons of SCT-P7 + DOI animals (see histograms in A4; p < 0.05) to reach values observed in control-P7. In contrast, the average membrane fluorescence intensity of GlyRα1, which did not significantly change after SCT (compare histograms for control-P7 vs SCT-P7 rats treated with NaCl in B4) was not affected by the treatment with DOI (histograms in B4; p = 0.35). Whiskers above and below the box indicate the 90th and 10th percentiles; the number of motoneurons analyzed is indicated in each box. (Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric test, *p < 0.05; ns, nonsignificant).

GABAARα3

The results for GABAARα3 were similar to those for GABAARα2. In control-P12 (Fig. 5C1), the densities of GABAARα3s were close to values observed in control-P7 (Figs. 2C2, 5D; p = 0.43 and 0.98 on cell bodies and dendrites, respectively). In SCT-P12 animals, the densities of GABAARα3 significantly increased compared with both control-P12 and -P1 (p < 0.05 for both comparisons).

In SCT-P12 rats, the rates of colocalization of GlyRα1 with GABAARα2 (cell bodies: 88.64%; dendrites: 90.28%) and GABAARα3 (86.47% and 84.24% on somata and dendrites, respectively) were not significantly different from those calculated in control-P1. These results lead to the conclusion that 7 d after a complete SCT made at P5, GABAARα2 and GABAARα3 are considerably upregulated at the surface of TS motoneurons. Their densities reached values significantly higher than those observed at birth, when the developmental downregulation of GABAAR is not completed. In contrast, a transection made at P5 did not alter the expression of GlyRα1, thereby confirming that the developmental upregulation of this subunit is completed at the end of the first postnatal week.

Activation of 5-HT2R compensatesthe effect of SCT on the expression of GABAAR

A neonatal SCT suppresses the action of pathways descending from the brainstem, in particular serotoninergic (5-HT) projections, on the lumbar enlargement. Since 5-HT2Rs play a key role in the modulation, development and recovery of motor function after spinal cord injury (Barbeau and Rossignol, 1990; Miller et al., 1996; Kim et al., 1999; Vinay et al., 2002; Norreel et al., 2003; Boulenguez and Vinay, 2009), we investigated whether the activation of 5-HT2Rs would reduce the abnormal expression of GABAAR subunits observed in TS motoneurons of SCT-P7 animals. Four rats with neonatal SCT received repeated intraperitoneal injection of DOI, a 5-HT2 agonist, from P4 to P7. They were compared with three SCT-P7 rats which received equivalent volumes of NaCl 0.9% and with control P7 rats. To get an overall view of the effects of DOI on the GABAAR, bd-17 antibody, which is directed against both β2 and β3 subunits and therefore recognize the major GABAAR subtypes in the CNS (Fritschy et al., 1994; Alvarez et al., 1996; McKernan and Whiting, 1996) was use and covisualized with the GlyRα1 on FB-labeled motoneurons (Fig. 6). In NaCl-treated SCT-P7 rats, the median membrane fluorescence intensity of GABAAβ2,3 was 583 ± 146 (Fig. 6A1,D1). In DOI-treated animals, this density significantly dropped down to values (Fig. 6A2–4; 265 ± 143; p < 0.05) that were not significantly different from those measured on control-P7 animals (Fig. 6A1; 285 ± 120, p = 0.13). In contrast, the membrane fluorescence intensity of GlyRα1 did not significantly change after DOI treatment (Fig. 6B1–4; SCT-P7-NaCl, 370 ± 64; SCT-P7-DOI, 497 ± 105, p = 0.35) and remained similar to that measured in control-P7 (Fig. 6B1). These results show that activation of 5-HT2Rs with DOI enables the reversal of the upregulation of the expression of GABAARs in ankle extensor motoneurons after SCT.

Discussion

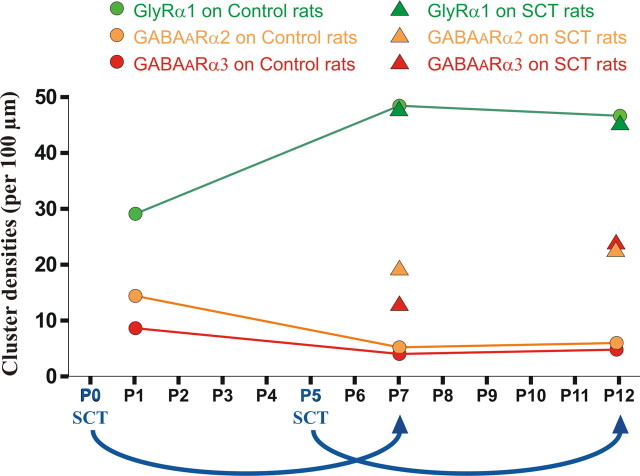

Our results demonstrate that the removal of supraspinal influences on lumbar sensorimotor networks affects differentially the GABAergic and glycinergic synaptic transmission to triceps surae motoneurons. A neonatal SCT prevents the downregulation of GABAA receptors that normally occurs during the first postnatal week and a SCT performed at a later stage upregulates this system (Fig. 7). In contrast, the glycinergic system appears to be relatively insensitive to SCT. A downregulation of GABAA receptors, similar to what is observed during normal development was induced after SCT, by activating 5-HT2Rs. These data provide new perspectives on the role of descending pathways in the plasticity of GABAergic and glycinergic systems.

Figure 7.

Summary of the analysis of cluster densities of GlyRα1 (green), GABAARα2 (orange), and GABAARα3 (red) on the membrane of the cell bodies of TS motoneurons. Circles indicate membrane densities quantified in control rats at P1, P7, and P12, whereas triangles show the densities observed 7 d after a neonatal SCT or a SCT performed at P5. The glycinergic system appears to be relatively insensitive to SCT. In contrast, a neonatal SCT prevents the downregulation of GABAA receptors that normally occurs during the first postnatal week and a SCT performed at a later stage (P5), when the expression of these receptors is low, upregulates this system.

Postnatal development of GlyR and GABAAR in TS motoneurons

A transition from GABAergic to glycinergic synaptic transmission occurs at the level of lumbar motoneurons during perinatal development (Gao et al., 2001). Our results show that this maturation continues during the first postnatal week. At P1 the rate of expression of the α1-containing adult form of the GlyR reaches 70% of its maximal rate (P7), which is consistent with the early (P0) presence of GlyRα1 mRNA in rat spinal cord (Malosio et al., 1991). Both GlyT2 and gephyrin, shown to be critical for the functional clustering of the GlyR (Kneussel et al., 1999; Gomeza et al., 2003; Lévi et al., 2004), are highly associated with GlyRα1 at P1.

GABAARs are expressed early during ontogeny (E13), and α1, α2, α3 and α5 mRNAs are detected in the embryonic spinal cord (Ma et al., 1993). We show that at P1, only the GABAARα2 and GABAARα3 remain expressed on the surface of TS motoneurons. During the first postnatal week, the expression of both subunits decreases but they are still observed at P12, in agreement with in situ hybridization in adult rat lumbar spinal cord (Wisden et al., 1991). At P7, mixed GABA/glycine events represented 18% of the miniature IPSCs. This is close from observations made at P1-P3 (21%; Gao et al., 2001) but smaller than those reported by Jonas et al. (1998) at P5–P10 (44%). The discrepancy may result from the use of benzodiazepines (Chéry and de Koninck, 1999; Keller et al., 2001).

During the first postnatal week, we observed higher rates of expression of GlyRα1 and GABAAR on proximal dendrites than on somata. Axo-dendritic inhibitory synapses evoke local shunt of the synaptic currents (Rall, 1959), which, on proximal dendrites, play pivotal roles by either blocking the back-propagation of the action potentials in the dendrites or controlling the weight of the excitatory inputs flowing along dendrites (Skydsgaard and Hounsgaard, 1994; Bras et al., 2003).

Differential effect of a complete thoracic SCT on the glycinergic and GABAergic systems

In the rat, the first projections from the brainstem reach the lumbar cord before birth (E17) (Vinay et al., 2000) when inhibitory synaptic transmission is predominantly GABAergic. The number of descending axons reaching the lumbar cord then gradually increases until the second postnatal week (Lakke, 1997), when mature inhibitory synaptic transmission relies essentially on glycine (Gao et al., 2001). This overlap of the time windows raises the question of a possible causal link between the development of supraspinal control and inhibitory synaptic transmission. We therefore hypothesized that a neonatal SCT would maintain a P1-like pattern of expression of GlyR and GABAAR. This hypothesis was not confirmed for GlyR since after neonatal SCT, the densities of GlyRα1 and their rate of association with GlyT2 or gephyrin were not affected. Functionally, our electrophysiological data confirmed that the decay time, frequency and amplitude of glycinergic mIPSCs were unchanged after SCT. Although an over expression of the immature GlyRα2 cannot be ruled out, this hypothesis seems unlikely because the presence of this subunits would have lengthened the decay time of glycinergic events (Takahashi et al., 1992).

In contrast, the neonatal SCT resulted in a significant increase in the proportion of GABAergic events in SCT-P7 motoneurons. Immunohistochemistry strongly suggests that these changes result from a blockade or, at least a delay, of maturation. Indeed, on SCT-P7 motoneurons, the exclusive expression of GABAARα2 and GABAARα3, their density and rates of colocalization with both GlyRα1 and gephyrin were similar to those observed at P1. In SCT-P7 motoneurons, we also report that the decay time of GABA mIPSCs was longer than those measured in control-P7 motoneurons. This is also consistent with a blockade of maturation after SCT since a developmental decrease in the decay time constant of GABA events has been reported in lumbar or hypoglossal motoneurons (Gao et al., 2001; Muller et al., 2006) and in cortical neurons (Dunning et al., 1999). Furthermore, an increased intracellular concentration of Cl− ions slows down the kinetic of GABAA receptors (Houston et al., 2009). As a neonatal SCT prevents the hyperpolarizing shift of the chloride equilibrium potential that normally occur during the first postnatal week (Jean-Xavier et al., 2006), the resulting higher intracellular chloride concentration in SCT animals may also account for the slower GABAA kinetics. However, although glycine receptors are also sensitive to the intracellular Cl− concentration (Pitt et al., 2008), at this stage of the development, we did not observe any change in the kinetics of these receptors.

After neonatal transection, a left-right alternating locomotor pattern is observed in P1–P3 rats. It is gradually lost during the first postnatal week but reappears after activating 5-HT2Rs with DOI (Norreel et al., 2003). This reversibility suggested that the synchrony resulted more from a disorganization of the alternating pattern than from the emergence of new pattern (Norreel et al., 2003). However, our data show that structural changes are not exclusively attributed to motoneurons, since an increased density of GABAARα1-immunopositive fibers within the motoneuronal area (see supplemental Fig. 2, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material) is observed after SCT. In addition, an increase in the GABAAγ2 subunits has been reported in astrocytes after neonatal SCT (Khristy et al., 2009). However, the effects of these changes on the network activity remain unknown. Interestingly, 24 h after spinal cord contusion made at P14, a significant decrease in the AMPA and NMDA receptor subunits has been reported (Brown et al., 2004), whereas the excitability of lumbar spinal networks is increased (Norreel et al., 2003). This seems inconsistent with the increased expression of GABAAR observed in our study. However, IPSPs remain depolarizing from rest after neonatal SCT (Jean-Xavier et al., 2006). Depolarizing IPSPs have a reduced inhibitory strength, compared with hyperpolarizing IPSPs and can even exert facilitation on excitatory inputs (Jean-Xavier et al., 2007). The increased expression of GABAAR can therefore lead to a higher excitability of neurons and networks.

Because activity-dependent mechanisms are important in the maturation of neurons and networks, the increased expression of GABAAR in SCT animals can be due either to the lack of supraspinal influences or the resulting increased network activity. However, we showed that repeated activation of 5-HT2R by DOI enabled to restore this downregulation. This strongly suggests a contribution of the serotonergic system to the maturation of the GABAergic system. Although the mechanisms underlying this interaction are unknown, several observations support a role of 5-HT in the modulation of the GABAergic system. (1) 5-HT descending inputs exert a negative control on the GABAergic phenotype during embryonic development (Allain et al., 2005). (2) The number of cells expressing glutamate decarboxylase mRNA (a marker of GABA synthesis) is increased below a lesion compared with intact animals and transplantation of embryonic raphe cells restores this number to control levels (Dumoulin et al., 2000). (3) Activation of 5-HT2CRs produces a long-lasting inhibition of GABAAR in Xenopus oocytes (Huidobro-Toro et al., 1996). A striking observation in the present study was the absence of effect of SCT on GlyR, suggesting that the development of this system relies neither on supraspinal influences nor on activity-dependent mechanisms.

One week after a transection performed at P5, i.e., when inhibitory synaptic transmission is more mature, compared with P0, an over expression of the GABAAR was observed, with rates of expression significantly higher than those in control-P1, whereas the densities of GlyRs remained unchanged. This dual effect of SCT on the glycinergic and GABAergic systems is consistent with results by Diaz-Ruiz et al. (2007) showing that the concentration of GABA increases shortly after spinal cord contusion in adult rats whereas that of glycine remains unchanged. Note, however that the glycinergic system may be affected at longer delays postinjury, as reported by Edgerton et al. (2001) 12 weeks after a SCT at P5 in rats. Furthermore, differential effects of transection on different neuronal populations, such as for instance flexor versus extensor motor pools (Khristy et al., 2009) cannot be ruled out.

To conclude, the present results provide additional evidence that postsynaptic inhibition is altered in the lumbar spinal cord after SCT (for review, see Vinay and Jean-Xavier, 2008; Boulenguez and Vinay, 2009). Chronic treatment with 5-HT2R agonists partially restores locomotion in adult spinal rats (Antri et al., 2002). An intriguing hypothesis which will be tested further is that the activation of 5-HT2R restores postsynaptic inhibition to control levels, in a way similar to training (Tillakaratne et al., 2002; Khristy et al., 2009).

Footnotes

This work was supported by The Dana and Christopher Reeve Foundation Grants VB1-0502- and VB2-0801-2 (to L.V.) and the French Institut pour la Recherche sur la Moelle épinière et l'Encéphale (to L.V.). K.S. received a grant from the Association Française contre les Myopathies (Grant 13912). S.T. received a grant from Fondation pour le Recherche Médicale (Grant FDT20081213783). We thank J. M. Fritschy for kindly providing primary antibodies against GABAARα1, α2, α3, and α5 subunits; Claude Moretti and Pascal Weber, at the Imagery Service at the Institut de Biologie du Développement de Marseille Luminy, Marseille, France, for their assistance with confocal microscopy; and Nathalie Baril, UMR6149, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, 6149 Marseille, France, for anatomical MRI experiments. We are indebted to Dr. Henri Burnet for the statistical analysis.

References

- Allain AE, Meyrand P, Branchereau P. Ontogenic changes of the spinal GABAergic cell population are controlled by the serotonin (5-HT) system: implication of 5-HT1 receptor family. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8714–8724. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2398-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez FJ, Taylor-Blake B, Fyffe RE, De Blas AL, Light AR. Distribution of immunoreactivity for the beta 2 and beta 3 subunits of the GABAA receptor in the mammalian spinal cord. J Comp Neurol. 1996;365:392–412. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960212)365:3<392::AID-CNE5>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antri M, Orsal D, Barthe JY. Locomotor recovery in the chronic spinal rat: effects of long-term treatment with a 5-HT2 agonist. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:467–476. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer K, Waldvogel HJ, During MJ, Snell RG, Faull RL, Rees MI. Association of gephyrin and glycine receptors in the human brainstem and spinal cord: an immunohistochemical analysis. Neuroscience. 2003;122:773–784. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00543-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbeau H, Rossignol S. The effects of serotonergic drugs on the locomotor pattern and on cutaneous reflexes of the adult chronic spinal cat. Brain Res. 1990;514:55–67. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90435-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlhalter S, Weinmann O, Mohler H, Fritschy JM. Laminar compartmentalization of GABAA-receptor subtypes in the spinal cord: an immunohistochemical study. J Neurosci. 1996;16:283–297. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-01-00283.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulenguez P, Vinay L. Strategies to restore motor functions after spinal cord injury. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009;19:587–600. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bras H, Lahjouji F, Korogod SM, Kulagina IB, Barbe A. Heterogeneous synaptic covering and differential charge transfer sensitivity among the dendrites of a reconstructed abducens motor neurone: correlations between electron microscopic and computer simulation data. J Neurocytol. 2003;32:5–24. doi: 10.1023/a:1027307714085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KM, Wrathall JR, Yasuda RP, Wolfe BB. Glutamate receptor subunit expression after spinal cord injury in young rats. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2004;152:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chéry N, de Koninck Y. Junctional versus extrajunctional glycine and GABA(A) receptor-mediated IPSCs in identified lamina I neurons of the adult rat spinal cord. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7342–7355. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07342.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crestani F, Assandri R, Täuber M, Martin JR, Rudolph U. Contribution of the alpha1-GABA(A) receptor subtype to the pharmacological actions of benzodiazepine site inverse agonists. Neuropharmacology. 2002;43:679–684. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delpy A, Allain AE, Meyrand P, Branchereau P. NKCC1 cotransporter inactivation underlies embryonic development of chloride-mediated inhibition in mouse spinal motoneuron. J Physiol. 2008;586:1059–1075. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.146993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Ruiz A, Salgado-Ceballos H, Montes S, Maldonado V, Tristan L, Alcaraz-Zubeldia M, Rios C. Acute alterations of glutamate, glutamine, GABA, and other amino acids after spinal cord contusion in rats. Neurochem Res. 2007;32:57–63. doi: 10.1007/s11064-006-9225-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumoulin A, Privat A, Giménez y Ribotta M. Transplantation of embryonic Raphe cells regulates the modifications of the gabaergic phenotype occurring in the injured spinal cord. Neuroscience. 2000;95:173–182. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00412-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning DD, Hoover CL, Soltesz I, Smith MA, O'Dowd DK. GABA(A) receptor-mediated miniature postsynaptic currents and alpha-subunit expression in developing cortical neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:3286–3297. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.6.3286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgerton VR, Leon RD, Harkema SJ, Hodgson JA, London N, Reinkensmeyer DJ, Roy RR, Talmadge RJ, Tillakaratne NJ, Timoszyk W, Tobin A. Retraining the injured spinal cord. J Physiol. 2001;533:15–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0015b.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer F, Kneussel M, Tintrup H, Haverkamp S, Rauen T, Betz H, Wässle H. Reduced synaptic clustering of GABA and glycine receptors in the retina of the gephyrin null mutant mouse. J Comp Neurol. 2000;427:634–648. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001127)427:4<634::aid-cne10>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritschy JM, Brünig I. Formation and plasticity of GABAergic synapses: physiological mechanisms and pathophysiological implications. Pharmacol Ther. 2003;98:299–323. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(03)00037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritschy JM, Mohler H. GABAA-receptor heterogeneity in the adult rat brain: differential regional and cellular distribution of seven major subunits. J Comp Neurol. 1995;359:154–194. doi: 10.1002/cne.903590111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritschy JM, Paysan J, Enna A, Mohler H. Switch in the expression of rat GABAA-receptor subtypes during postnatal development: an immunohistochemical study. J Neurosci. 1994;14:5302–5324. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-09-05302.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritschy JM, Johnson DK, Mohler H, Rudolph U. Independent assembly and subcellular targeting of GABA(A)-receptor subtypes demonstrated in mouse hippocampal and olfactory neurons in vivo. Neurosci Lett. 1998;249:99–102. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00397-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritschy JM, Schweizer C, Brünig I, Lüscher B. Pre- and post-synaptic mechanisms regulating the clustering of type A gamma-aminobutyric acid receptors (GABAA receptors) Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31:889–892. doi: 10.1042/bst0310889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao BX, Ziskind-Conhaim L. Development of glycine- and GABA-gated currents in rat spinal motoneurons. J Neurophysiol. 1995;74:113–121. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao BX, Cheng G, Ziskind-Conhaim L. Development of spontaneous synaptic transmission in the rat spinal cord. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:2277–2287. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.5.2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao BX, Stricker C, Ziskind-Conhaim L. Transition from GABAergic to glycinergic synaptic transmission in newly formed spinal networks. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:492–502. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.1.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiman EJ, Zheng W, Fritschy JM, Alvarez FJ. Glycine and GABA(A) receptor subunits on Renshaw cells: relationship with presynaptic neurotransmitters and postsynaptic gephyrin clusters. J Comp Neurol. 2002;444:275–289. doi: 10.1002/cne.10148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingrich KJ, Roberts WA, Kass RS. Dependence of the GABAA receptor gating kinetics on the alpha-subunit isoform: implications for structure-function relations and synaptic transmission. J Physiol. 1995;489:529–543. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomeza J, Ohno K, Hülsmann S, Armsen W, Eulenburg V, Richter DW, Laube B, Betz H. Deletion of the mouse glycine transporter 2 results in a hyperekplexia phenotype and postnatal lethality. Neuron. 2003;40:797–806. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00673-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Günther U, Benson J, Benke D, Fritschy JM, Reyes G, Knoflach F, Crestani F, Aguzzi A, Arigoni M, Lang Y. Benzodiazepine-insensitive mice generated by targeted disruption of the gamma 2 subunit gene of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:7749–7753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston CM, Bright DP, Sivilotti LG, Beato M, Smart TG. Intracellular chloride ions regulate the time course of GABA-mediated inhibitory synaptic transmission. J Neurosci. 2009;29:10416–10423. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1670-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huidobro-Toro JP, Valenzuela CF, Harris RA. Modulation of GABAA receptor function by G protein-coupled 5-HT2C receptors. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35:1355–1363. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(96)00084-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jean-Xavier C, Pflieger JF, Liabeuf S, Vinay L. Inhibitory postsynaptic potentials in lumbar motoneurons remain depolarizing after neonatal spinal cord transection in the rat. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96:2274–2281. doi: 10.1152/jn.00328.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jean-Xavier C, Mentis GZ, O'Donovan MJ, Cattaert D, Vinay L. Dual personality of GABA/glycine-mediated depolarizations in immature spinal cord. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11477–11482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704832104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas P, Bischofberger J, Sandkühler J. Corelease of two fast neurotransmitters at a central synapse. Science. 1998;281:419–424. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5375.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller AF, Coull JA, Chery N, Poisbeau P, De KY. Region-specific developmental specialization of GABA-glycine cosynapses in laminas I–II of the rat spinal dorsal horn. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7871–7880. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-20-07871.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall MG, Buckland WR. A dictionary of statistical terms. Ed 2. New York: Hafner; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Khristy W, Ali NJ, Bravo AB, de Leon R, Roy RR, Zhong H, London NJ, Edgerton VR, Tillakaratne NJ. Changes in GABA(A) receptor subunit gamma 2 in extensor and flexor motoneurons and astrocytes after spinal cord transection and motor training. Brain Res. 2009;1273:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.03.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Adipudi V, Shibayama M, Giszter S, Tessler A, Murray M, Simansky KJ. Direct agonists for serotonin receptors enhance locomotor function in rats that received neural transplants after neonatal spinal transection. J Neurosci. 1999;19:6213–6224. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-06213.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch J, Malosio ML, Wolters I, Betz H. Distribution of gephyrin transcripts in the adult and developing rat brain. Eur J Neurosci. 1993;5:1109–1117. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1993.tb00965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzman P. VGLUT1 and GLYT2 labeling of sacrocaudal motoneurons in the spinal cord injured spastic rat. Exp Neurol. 2007;204:195–204. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kneussel M, Brandstätter JH, Laube B, Stahl S, Müller U, Betz H. Loss of postsynaptic GABA(A) receptor clustering in gephyrin-deficient mice. J Neurosci. 1999;19:9289–9297. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-21-09289.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kralic JE, Sidler C, Parpan F, Homanics GE, Morrow AL, Fritschy JM. Compensatory alteration of inhibitory synaptic circuits in cerebellum and thalamus of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor alpha1 subunit knockout mice. J Comp Neurol. 2006;495:408–421. doi: 10.1002/cne.20866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakke EA. The projections to the spinal cord of the rat during development: a timetable of descent. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol. 1997;135:I–XIV. 1–143. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-60601-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legendre P. The glycinergic inhibitory synapse. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58:760–793. doi: 10.1007/PL00000899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lévi S, Logan SM, Tovar KR, Craig AM. Gephyrin is critical for glycine receptor clustering but not for the formation of functional GABAergic synapses in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:207–217. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1661-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Wong-Riley MT. Postnatal expression of neurotransmitters, receptors, and cytochrome oxidase in the rat pre-Botzinger complex. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92:923–934. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00977.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo LE, Barbe A, Portalier P, Fritschy JM, Bras H. Differential expression of GABAA and glycine receptors in ALS-resistant vs. ALS-vulnerable motoneurons: possible implications for selective vulnerability of motoneurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:3161–3170. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo LE, Russier M, Barbe A, Fritschy JM, Bras H. Differential organization of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A and glycine receptors in the somatic and dendritic compartments of rat abducens motoneurons. J Comp Neurol. 2007;504:112–126. doi: 10.1002/cne.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma W, Saunders PA, Somogyi R, Poulter MO, Barker JL. Ontogeny of GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs in rat spinal cord and dorsal root ganglia. J Comp Neurol. 1993;338:337–359. doi: 10.1002/cne.903380303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahendrasingam S, Wallam CA, Hackney CM. An immunogold investigation of the relationship between the amino acids GABA and glycine and their transporters in terminals in the guinea-pig anteroventral cochlear nucleus. Brain Res. 2000;887:477–481. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03054-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malosio ML, Marquèze-Pouey B, Kuhse J, Betz H. Widespread expression of glycine receptor subunit mRNAs in the adult and developing rat brain. EMBO J. 1991;10:2401–2409. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07779.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKernan RM, Whiting PJ. Which GABAA-receptor subtypes really occur in the brain? Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:139–143. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)80023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JF, Paul KD, Lee RH, Rymer WZ, Heckman CJ. Restoration of extensor excitability in the acute spinal cat by the 5-HT2 agonist DOI. J Neurophysiol. 1996;75:620–628. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.2.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller E, Le Corronc H, Triller A, Legendre P. Developmental dissociation of presynaptic inhibitory neurotransmitter and postsynaptic receptor clustering in the hypoglossal nucleus. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2006;32:254–273. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norreel JC, Pflieger JF, Pearlstein E, Simeoni-Alias J, Clarac F, Vinay L. Reversible disorganization of the locomotor pattern after neonatal spinal cord transection in the rat. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1924–1932. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-05-01924.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ornung G, Shupliakov O, Ottersen OP, Storm-Mathisen J, Cullheim S. Immunohistochemical evidence for coexistence of glycine and GABA in nerve terminals on cat spinal motoneurones: an ultrastructural study. Neuroreport. 1994;5:889–892. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199404000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer F, Simler R, Grenningloh G, Betz H. Monoclonal antibodies and peptide mapping reveal structural similarities between the subunits of the glycine receptor of rat spinal cord. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:7224–7227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.22.7224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt SJ, Sivilotti LG, Beato M. High intracellular chloride slows the decay of glycinergic currents. J Neurosci. 2008;28:11454–11467. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3890-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poyatos I, Ponce J, Aragón C, Giménez C, Zafra F. The glycine transporter GLYT2 is a reliable marker for glycine-immunoreactive neurons. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1997;49:63–70. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajaofetra N, Sandillon F, Geffard M, Privat A. Pre- and post-natal ontogeny of serotonergic projections to the rat spinal cord. J Neurosci Res. 1989;22:305–321. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490220311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rall W. Branching dendritic trees and motoneuron membrane resistivity. Exp Neurol. 1959;1:491–527. 491–527. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(59)90046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassoè-Pognetto M, Fritschy JM. Mini-review: gephyrin, a major postsynaptic protein of GABAergic synapses. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:2205–2210. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider Gasser EM, Straub CJ, Panzanelli P, Weinmann O, Sassoè-Pognetto M, Fritschy JM. Immunofluorescence in brain sections: simultaneous detection of presynaptic and postsynaptic proteins in identified neurons. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1887–1897. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder S, Hoch W, Becker CM, Grenningloh G, Betz H. Mapping of antigenic epitopes on the alpha 1 subunit of the inhibitory glycine receptor. Biochemistry. 1991;30:42–47. doi: 10.1021/bi00215a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigel E, Baur R, Trube G, Möhler H, Malherbe P. The effect of subunit composition of rat brain GABAA receptors on channel function. Neuron. 1990;5:703–711. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90224-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skydsgaard M, Hounsgaard J. Spatial integration of local transmitter responses in motoneurones of the turtle spinal cord in vitro. J Physiol. 1994;479:233–246. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spike RC, Watt C, Zafra F, Todd AJ. An ultrastructural study of the glycine transporter GLYT2 and its association with glycine in the superficial laminae of the rat spinal dorsal horn. Neuroscience. 1997;77:543–551. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00501-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stil A, Liabeuf S, Jean-Xavier C, Brocard C, Viemari JC, Vinay L. Developmental up-regulation of the potassium-chloride cotransporter type 2 in the rat lumbar spinal cord. Neuroscience. 2009;164:809–821. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taal W, Holstege JC. GABA and glycine frequently colocalize in terminals on cat spinal motoneurons. Neuroreport. 1994;5:2225–2228. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199411000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K. [Development of excitable membrane in an early embryo] Tanpakushitsu Kakusan Koso. 1984;29:1889–1898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Momiyama A, Hirai K, Hishinuma F, Akagi H. Functional correlation of fetal and adult forms of glycine receptors with developmental changes in inhibitory synaptic receptor channels. Neuron. 1992;9:1155–1161. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90073-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taketo M, Yoshioka T. Developmental change of GABA(A) receptor-mediated current in rat hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2000;96:507–514. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00574-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillakaratne NJ, de Leon RD, Hoang TX, Roy RR, Edgerton VR, Tobin AJ. Use-dependent modulation of inhibitory capacity in the feline lumbar spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3130–3143. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-08-03130.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triller A, Cluzeaud F, Pfeiffer F, Betz H, Korn H. Distribution of glycine receptors at central synapses: an immunoelectron microscopy study. J Cell Biol. 1985;101:683–688. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.2.683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinay L, Jean-Xavier C. Plasticity of spinal cord locomotor networks and contribution of cation-chloride cotransporters. Brain Res Rev. 2008;57:103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinay L, Brocard F, Clarac F. Differential maturation of motoneurons innervating ankle flexor and extensor muscles in the neonatal rat. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:4562–4566. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2000.01321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinay L, Brocard F, Clarac F, Norreel JC, Pearlstein E, Pflieger JF. Development of posture and locomotion: an interplay of endogenously generated activities and neurotrophic actions by descending pathways. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2002;40:118–129. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00195-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker MC. GABAA receptor subunit specificity: a tonic for the excited brain. J Physiol. 2008;586:921–922. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.150581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisden W, Gundlach AL, Barnard EA, Seeburg PH, Hunt SP. Distribution of GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs in rat lumbar spinal cord. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1991;10:179–183. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(91)90109-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu WL, Ziskind-Conhaim L, Sweet MA. Early development of glycine- and GABA-mediated synapses in rat spinal cord. J Neurosci. 1992;12:3935–3945. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-10-03935.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee BK, Keist R, von Boehmer L, Studer R, Benke D, Hagenbuch N, Dong Y, Malenka RC, Fritschy JM, Bluethmann H, Feldon J, Möhler H, Rudolph U. A schizophrenia-related sensorimotor deficit links alpha 3-containing GABAA receptors to a dopamine hyperfunction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17154–17159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508752102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zafra F, Gomeza J, Olivares L, Aragón C, Giménez C. Regional distribution and developmental variation of the glycine transporters GLYT1 and GLYT2 in the rat CNS. Eur J Neurosci. 1995;7:1342–1352. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb01125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziskind-Conhaim L. Physiological functions of GABA-induced depolarizations in the developing rat spinal cord. Perspect Dev Neurobiol. 1998;5:279–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]