Abstract

Denmark has a large network of population-based medical databases, which routinely collect high-quality data as a by-product of health care provision. The Danish medical databases include administrative, health, and clinical quality databases. Understanding the full research potential of these data sources requires insight into the underlying health care system. This review describes key elements of the Danish health care system from planning and delivery to record generation. First, it presents the history of the health care system, its overall organization and financing. Second, it details delivery of primary, hospital, psychiatric, and elderly care. Third, the path from a health care contact to a database record is followed. Finally, an overview of the available data sources is presented. This review discusses the data quality of each type of medical database and describes the relative technical ease and cost-effectiveness of exact individual-level linkage among them. It is shown, from an epidemiological point of view, how Denmark’s population represents an open dynamic cohort with complete long-term follow-up, censored only at emigration or death. It is concluded that Denmark’s constellation of universal health care, long-standing routine registration of most health and life events, and the possibility of exact individual-level data linkage provides unlimited possibilities for epidemiological research.

Keywords: health care sector, political systems, population health, registries, epidemiology

Introduction

Denmark has a large network of population-based medical databases containing routinely collected data, covering many aspects of life and health.1 To fully grasp the potential of these data for research, and to properly interpret studies based on these resources, one must consider the underlying health care system and the pathway from the point of health service to a database record.

Three qualities make Denmark “an epidemiologist’s dream”:1 1) its universal tax-funded health care system with residency-based entitlement; 2) availability of government-maintained nationwide registries, providing longitudinal sources of routinely collected administrative, health, and clinical quality data; and 3) the unique personal identifier assigned to every Danish resident, enabling exact individual-level linkage of all records and lifelong follow-up. In epidemiological terms, the population of Denmark is an open cohort with known dates of entry and exit, and with various types of rich health data recorded between those dates.1

In this review (outlined in Table 1), we present the key elements of the Danish health care system – from planning and delivery to data registration. First, we present the history, the overall organization, and the financing of health care in Denmark. Second, we detail delivery of primary, hospital, psychiatric, and elderly care. Third, we follow the path from a health care contact to a database record and show how the Danish health care system provides a framework supporting the use of such records for epidemiological research and health care statistics.

Table 1.

The Danish health care system from health care planning and delivery to data registration: an outline of the present review

| Perspectives | Review sections |

|---|---|

| Health care planning (macro perspective) |

|

| Health care delivery (micro perspective) |

|

| Health care registration (research perspective) |

|

History of the Danish health care system

Denmark has a long tradition of public welfare, including provision of health services. Recent decades have brought about gradual changes in the structure of the Danish health care system, best subdivided into the periods before, between, and after the government reforms of 1970 and 2007.2 Before 1970, all Danish hospitals were owned by either Municipalities or Counties. Services provided by general practitioners (GPs) and specialists in private practice were funded by mandatory sickness funds, while hospital care was funded by local and federal taxes.2

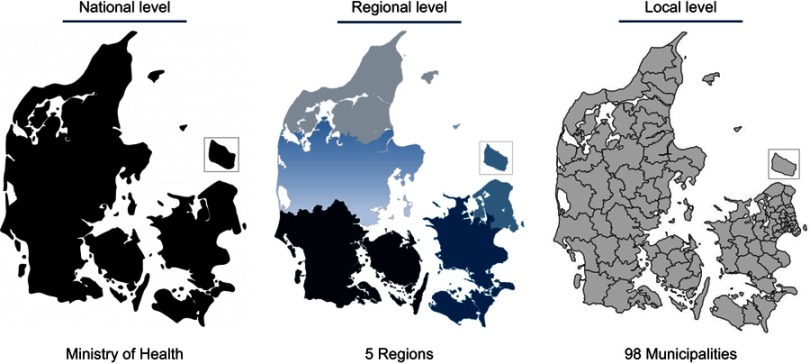

The local government reform of 1970 established the current organization of the Danish health care system.2 Counties became exclusive owners of hospitals, with attendant responsibilities; the health care system became almost entirely tax-funded; and the sickness fund system was abolished.3 In the 2007 reform of the Danish public sector,4 the number of Municipalities was substantially reduced, while five large Regions replaced the 14 Counties as the main administrative units (Figure 1). The Regions are defined geographically as the North Denmark Region (~0.6 million), the Central Denmark Region (~1.3 million), the Region of Southern Denmark (~1.2 million), the Region Zealand (~0.8 million), and the Capital Region of Denmark (population ~1.8 million). The five Regions have, since their establishment, had the primary responsibility for overseeing somatic and psychiatric hospitals, GPs, and specialists in private practice.

Figure 1.

The three administrative levels of the Danish health care system. Ministry of Health (modified).5

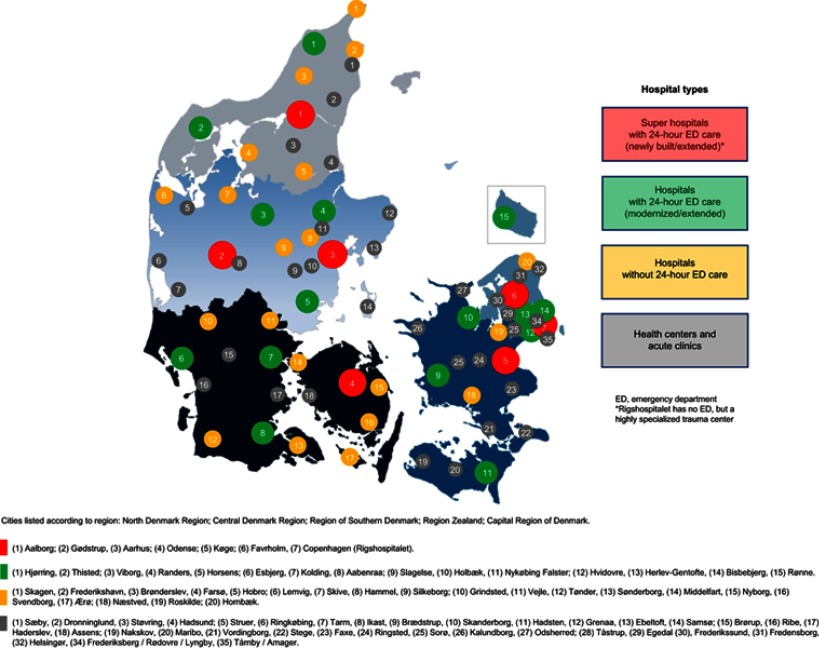

Following the 2007 reform, Denmark has invested substantially in its hospital system by extending and renovating existing hospitals and building new and larger facilities (Figure 2).4 There has been a simultaneous shift towards centralization, with fewer acute hospitals, closure of several small hospitals, and expansion of outpatient hospital care. Reforms have involved economic incentives to increase hospital productivity as measured by diagnosis-related groups, establishment of clinical programs to improve quality of care and patient safety, and implementation of electronic patient records. In addition, use of private hospital services has increased to adhere to government-mandated maximum waiting time guarantees.

Figure 2.

The hospital landscape in Denmark.

Organization of the Danish health care system

The Danish welfare model promotes society-wide health and social equity through tax-financed services, including universal health care, education, student aid, disability pensions, and unemployment insurance.3 The health care system is currently organized into three administrative levels (Figure 1): the national level (State), the regional level (5 Regions), and the local level (98 Municipalities). Elections are held separately for the national parliament at intervals of up to 4 years and for regional and municipal councils at exact 4-year intervals. In addition, Denmark also has a small private health care sector.

State

The government, headed by the Ministry of Health, is responsible for defining the framework of the Danish health care system. Thus, the Ministry of Health plays a steering role at the national level by passing health legislation, issuing national guidelines, protecting patients’ rights, conducting audits, and monitoring health care professionals, hospitals, and pharmacies. The Ministry of Health acts through various subordinate agencies, as described in Table 2.5

Table 2.

Danish health care authorities and their responsibilities

| Authority | Area of responsibility |

|---|---|

| Ministry of Health |

|

| Danish Health Authority |

|

| Danish Medicines Agency |

|

| Danish Patient Safety Authority |

|

| Danish Agency for Patient Complaints |

|

| Danish Health Data Authority |

|

| State Serum Institute |

|

| Danish Ethical Council |

|

| National Committee on Health Research Ethics |

|

Pharmacies are privately operated, but subject to state regulation. The Ministry of Health and the Danish Medicines Agency control the sector through a licensing system, which determines the number of pharmacies and their locations. The proprietor pharmacist owns his/her pharmacy and is economically responsible for its financing and operation, and may start up to seven branch pharmacies within 75 km from the main pharmacy. As of September 2017, the Danish community pharmacy sector consisted of 237 private community pharmacies. In addition, there were 202 branch pharmacies, 48 pharmacy outlets, and approximately 500 over-the-counter outlets and 350 medicine delivery facilities, all of which are affiliated with one of the pharmacies.6

Regions

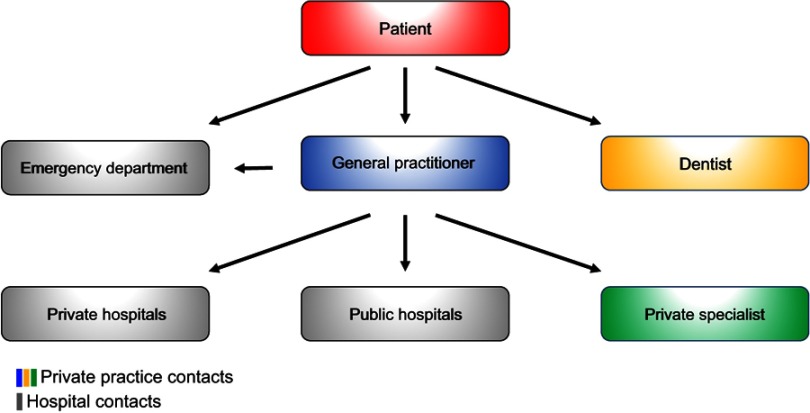

The Regions govern primary and secondary health care services, provided by GPs, hospitals, and specialists in private practice (Figure 3).5 The Regions also administer the drug reimbursement plan, based on data electronically collected by community pharmacies when prescriptions are dispensed. Although pharmacies operate privately, they are regulated by the government.

Figure 3.

Access structure of the Danish health care system. Except for emergency and dental care, general practitioners are the first point of contact for patients in the Danish health care system. General practitioners thereby act as gatekeepers to secondary care, including referrals to hospitals and office-based private specialists.

Public hospitals (somatic and psychiatric) and local community mental health centers are owned and operated by the Regions. Private hospitals have also provided certain services to the Regions since 2002, under the policy of “extended free choice of hospital”. According to this policy, residents in need of hospital care may choose, within certain limits, among all public or private hospitals. Thus, if a Region cannot ensure diagnostic examination within 30 days of referral, patients have the right to examination at a private hospital in Denmark or at a hospital abroad (the latter is subject to approval by the Danish Health Authority). If, for medical reasons, it is not possible to provide a diagnosis within 1 month, at a minimum, a patient must receive a detailed plan for further investigation of the presenting health problem. If, for lack of capacity, a Region is unable to provide a diagnostic assessment within 30 days, the “extended free choice of hospital” policy applies. Patients with life-threatening diseases may be referred by the Regions for experimental treatment in private hospitals in Denmark or abroad, if such treatment is not available in public hospitals. In accordance with European Union Regulations on the coordination of social security systems and cross-border health care, Danish residents have the right to be reimbursed for the costs of health care provided in other European Union/European Economic Area Member States.5

GPs practice privately and work according to a collective agreement, subject to periodic renegotiations between the government and the physicians’ union. Remuneration is based on a combination of capitation (based on patient lists) and fee-for-service. Specialists in private practice are also self-employed and are reimbursed for the mandated health services on a fee-for-service basis.5

Municipalities

A special national funding scheme (social financing agreement) ensures provision of certain health services for disadvantaged resident groups, such as recipients of welfare benefits and the elderly. Otherwise, implementation and delivery of health care services are largely decentralized on the regional or municipal levels. Municipalities are responsible for social and community care, including welfare allowances (eg, disability pensions), home care, elderly care, housing for the mentally disabled and homeless, care for mentally or physically disabled persons, as well as substance abuse and addiction treatment. Municipalities also provide a wide range of primary and preventive services, including prenatal and postnatal home visits, rehabilitation, school health services, and pediatric dental care.5

Although primary prevention programs at the local level are not mandated by law, Municipalities are responsible for ensuring that local communities provide healthy environments, activities, and facilities that promote well-being and prevent disease. Because Municipalities cofinance treatment provided by hospitals and GPs, they have an economic incentive to implement effective disease-prevention and health-promotion programs.5

Private health care

Private hospitals account for less than 1% of hospital beds in Denmark. Only a small percentage of health care services are delivered by private providers without a reimbursement contract with the National Health Service. Reasons for using private hospitals and clinics include faster access to diagnostic procedures or treatment and a desire for treatments not covered by public health insurance (eg, fertility treatment beyond the first child and most cosmetic surgery). The three ways to access private hospitals and clinics are self-payment, private health insurance, and via a public subsidy under the “extended free choice of hospital” scheme described above.5

Private health insurance typically covers services not covered or only partially covered by the national health care system. Also, many Danish employers offer private health insurance as an employment benefit. The non-profit organization “Health Insurance Denmark” (“Sygeforsikringen Danmark”) is a common source of private insurance policies. Although 40% of the population is covered by private health insurance, it accounts for less than 2% of total health care expenditures.7

Financing of the Danish health care system

Taxation

All residents contribute to the financing of the health care system through federal and local taxation, and may not opt out, though certain expenses are deductible. Tax revenue finances 84% of the total health care expenditure (approximately 8.9% of the gross domestic product).5 Out-of-pocket copayments are moderate compared with other European countries,8 amounting to 16% of health care expenditures (1.7% of the gross domestic product), mainly through contributions to the costs of medications (detailed below under “Medicines”), prescribed physiotherapy (60% copayment), glasses (for children <16 years and senior citizens), and dental care. Dental care is free until age 18, after which most treatment costs are self-covered. Still, public funding is provided to help defray the costs of dental examinations, preventive treatments, treatment of caries, periodontal disease, root decay, and tooth extractions.

In 2014, total health care expenditures in Denmark accounted for 10.6% of the gross domestic product, which is slightly higher than the average expenditure (9.0%) in the countries within the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.5 The expenditure for care of the elderly and disabled accounted in the same year for about 2.8% of the gross domestic product, and total per capita spending was $4,906.8

Administration

The economic framework for the Danish health care system is set at the national level and administered through block grants, reimbursements, and equalization schemes. As part of the annual national budget, a financial agreement is made between the national, regional, and municipal administrative levels. Each Region has the mandate to regulate and balance its services and needs. Regions and Municipalities are obliged to meet their budget with a 1.5% margin. Meeting budget targets has traditionally required productivity increases.5

The Regions are funded through a block grant (75%), as well as activity-based subsidies from both the national government and the Municipalities. Municipalities themselves are financed by a block grant from government and by local taxes. Government block grants take into account regional variation, including demographic differences. Similarly, the activity-based subsidies are based on hospital activity, accounting for patient numbers and characteristics (diagnoses, treatments, and demographics). The amount of the Municipal activity-based subsidy depends on the extent to which residents utilize regional health care services (eg, hospital and GP services). Successful disease prevention and health promotion provided by the Municipalities contribute to a decreased need for subsidies and, thus, to cost savings.5

Public health insurance

At the individual level, each Danish resident must choose between Group 1 and Group 2 membership in public health insurance. Group 1 members (>99% of the population) are registered with a specific GP, who provides primary care and referral to secondary care free of charge. Patients may self-refer to certain specialists, such as ophthalmologists, otolaryngologists, dentists, and chiropractors. Group 2 members may choose freely among GPs, dentists, chiropractors, and all private specialists without referral (except for physiotherapists, podiatrists, and psychologists), subject to copayment. For both Group 1 and Group 2 members, hospital treatment requires referral, but is free of charge.3

Medicines

Pharmaceutical companies are free to set official prices for their products. However, members of the Danish Association of the Pharmaceutical Industry are subject to a price-cap agreement between the Association, the Ministry of Health, and the Danish Regions. Procurement and pricing procedures differ between the primary and secondary health care sectors. At public hospitals, 99% of all medicines are purchased through the pharmaceutical procurement service Amgros, owned by the Regions.9 The Regions pay for all medicines used at hospitals, so that admitted patients receive them free of charge. In the primary health care sector, pricing of medicines varies among competing products, but for a given product prices are the same nationwide, ensuring price transparency.5

While medicines used during treatment at public hospitals are provided without cost to patients, patient copayments are required for prescriptions redeemed at community pharmacies.10 A central authority (Reimbursement Committee) decides whether costs of a particular medicine are partially reimbursable to patients. There are two different types of reimbursement schemes: general reimbursement, covering all residents automatically (although for some drugs reimbursement requires specification of an indication); and individual reimbursement, awarded on a case-by-case basis.10 All medicines under the general reimbursement scheme are tax-financed. According to this scheme, the percentage of costs reimbursed increases with an individual’s total expenditures for reimbursable medicines during the most recent 365 days. As of 2018, the first $150 is paid in full by the patient (except for children, whose parents immediately receive a 60% reimbursement).11 Subsequent reimbursements increase in steps of 50%, 75%, and 85%, until out-of-pocket expenditures are capped at about $600.11

Danish health care delivery systems

The different levels of health care at the point of delivery include primary, hospital, psychiatric, and elderly care, as described below.

Primary care

Primary health care services are provided by GPs, other health care professionals in private practice (eg, dentists, physiotherapists, and psychologists), and Danish Municipalities, as noted above. Primary health care providers contract with and are reimbursed by the National Health Service.12

General practitioners

GPs are generalists with the prerequisite skills to evaluate patients’ need for referral to specialists. GPs are assisted by hospital-based diagnostic support, including laboratory services and diagnostic imaging. All Danish residents have the right to be listed with a GP of their choice, and >99% are included in such lists (ie, Group 1 members). GPs are obligated to serve the patients who have registered with them, averaging 1,600 patients per GP. Although many GPs have a solo practice, an increasing proportion has been joining group practices.12

Except in emergencies, Denmark’s approximately 3,600 GPs (20% of the physician workforce) are the first point of contact for patients (Figure 3). GPs, thus, fill a key position in the Danish health care system, acting as gatekeepers to secondary (specialized) care, including referrals to office-based specialists and inpatient and outpatient hospital care. GPs also refer patients to municipal services for rehabilitation and home care. Primary care outside regular office hours is covered via a rotation system among GPs in a given geographical area. One exception is the Capital Region, which, since 2014, has had its own coverage system (“1813” pronounced: “eighteen-thirteen”, named after the emergency number), which is operated by nurses under the supervision of physicians.12

Home nursing

Home nurses provide care and treatment to patients who are acutely ill, chronically ill, or dying. Nurses are responsible for enabling patients to stay in their homes or close to home for as long as possible. All patients are entitled to home nursing free of charge, if prescribed by a physician. Also, the Municipalities are required to provide all necessary aids and appliances free of charge.

Some Municipalities have set up special residential units for short-term stays with intensive treatment by trained nurses for patients who do not require hospitalization but are temporarily unable to stay in their own homes. In addition, there are 19 adult hospices and one children’s hospice in Denmark, which care for incurably sick and dying patients.5

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation includes physical and cognitive training to restore the ability to carry out self-care and other activities of daily living. It includes patient education and training for re-employment. Rehabilitation efforts may start in the inpatient setting. At discharge, the hospital prepares a rehabilitation plan, describing the patient’s current functional level and rehabilitation needs. The hospital forwards the plan to both the Municipality and the patient’s GP, passing on responsibility for rehabilitation from the Region to the Municipality.5

Health checkups for children

All women who have given birth and their families receive regular home visits from a health visitor free of charge. Typically, health visitors are specially trained nurses. They track the child’s height and weight, provide parenting support and help with breastfeeding, and give general health advice. Health visitors work closely with midwives, nurses, and GPs.5

All children receive preventive health checkups at their GP’s office at ages 5 weeks, 5 months, 1 year, and annually thereafter until age 5. The examinations follow a set structure prescribed by the Danish Health Authority.13 The GP evaluates the child’s physical and mental health, growth, and general development, to identify or prevent health problems.

All Danish schoolchildren are entitled to school-based health checkups, conducted by health visitors and/or physicians. These regular checkups include assessment of height and weight, screening for vision and hearing abnormalities, physical and psychiatric symptoms, linguistic skills, sleeping/eating habits, social competencies, and general development. Upon reaching age 18 years, Danish men must appear before the Danish Draft Board to assess their fitness for military service. This assessment includes a detailed physical examination and a cognitive test.14

Vaccinations

The national childhood immunization program provides vaccines for children free of charge.

These include vaccines against pneumococcal disease (PCV 7), whooping cough, diphtheria, tetanus, polio, measles, German measles, mumps, Haemophilus influenzae type B, and human papilloma virus (currently Gardasil 9). Several other vaccines are available to high-risk groups, such as influenza vaccine for persons with certain chronic diseases or those older than 65 years. Routine vaccinations within the national immunization programs are paid for by the Regions, while vaccinations needed for, eg, vacations are not.5 For diphtheria, tetanus, and whooping cough, childhood immunization coverage is >90% in Denmark.

Hospital care

Each Region is responsible for providing hospital treatment to its residents, and emergency treatment to all persons in need. Of treatments provided in hospitals, 90% are considered standard and 10% are specialized. Standard treatments are usually provided at a hospital in the patient’s region of residence. Definitions of specialized treatments are based on the size of the affected patient group and the complexity and cost of needed services. Specialized treatments are categorized as regional functions (available in one to three hospitals per Region) or national (available only in one to three hospitals in the country).5

Between 2007 and 2020, highly specialized hospitals are expected to reduce the number of bed-days by 20% and to expand outpatient treatment by 50%.5 The emergency health care service is currently being restructured: 40 emergency departments have been merged into 21 larger units, staffed with specialists on a 24-hour basis (Figure 2). Pre-hospital emergency care is provided by paramedics, nurses, and doctors on the scene, in ambulances, or in especially equipped helicopters.5

Mental health care

Mental health care in Denmark has undergone considerable change during the last decades, marked by an increase in outpatient treatment and a reduction in the number of hospital beds. Community mental health centers provide outpatient treatment and extensive crisis support. While patients are not admitted, they may stay at a center until their condition improves or until a psychiatric diagnosis and treatment plan are available.5

In May 2015, the Danish Mental Health Act was amended with the aim of improving treatment for people with mental illness, including reduced use of coercive measures such as physical restraint. To ensure careful use of necessary coercive measures and limit the duration of restraint, the new rules stipulate a minimum frequency of medical supervision and continuous assessment of the ongoing need for restraint.5

Elderly care

Like many Western countries, Denmark has a growing elderly population, both in absolute numbers and relative to the total population. It is estimated that the number of persons older than 80 years will double by 2040.5 The age of eligibility for a state pension in Denmark has shifted upwards several times, in line with increased life expectancy. It is planned that the age of eligibility will increase again from the current 65 years to 67 years during 2019–2022, and to 68 years in 2030.5 To meet the challenges of an aging population, Danish policy aims to promote and extend the independence of elderly people, ensuring their continued self-sufficiency and well-being. The Municipalities achieve this goal through prevention and rehabilitation programs, and by providing free-of-charge home care services and nursing facilities. All Municipalities must establish Senior Citizens’ Councils to obtain client input. Council members must be above the age of 60 years and are elected for 4-year terms. Each Municipality must consult with its Senior Citizens Council regarding all issues relevant to its elderly population.5

Home care services are targeted at elderly people who live at home but are unable to manage everyday life on their own. Home care falls into two categories: practical help (eg, cleaning and laundering) and personal care (eg, bathing and shaving). In 2015, 12% of all persons over 65 years received home care services. While elderly people pay for food services, copayment cost may not exceed the average production cost. Self-reliance is a fundamental principle of home care services. Municipalities are required by law to assess whether a person in need of home care services could benefit from rehabilitation.5

Municipalities must provide preventive home visits to physically and socially vulnerable persons aged 65–79 years, whenever needed, and annual visits to all persons over 80 years. The purpose of these visits is to identify any need for individual assistance and to evaluate each elderly person’s well-being and current life situation.5 Municipalities are responsible for determining whether an elderly person should be offered the opportunity to move to a nursing home, providing extensive specialized care for those who no longer have full physical or mental faculties. In 2015, approximately 4% of persons over age 65 years lived in nursing homes in Denmark. Nursing home facilities are staffed around the clock by health care professionals. Residents pay individually for their room, food, and private expenses, while nursing and health care services are provided free of charge. The waiting time for a standard place in a nursing home must not exceed 2 months following referral.5

Danish health care data

Digital health

Denmark is an international pacesetter in digital health and ranks as number one regarding IT systems in hospitals and general practice, as well as digital communication among health care sectors.5 Increasing use of common IT standards facilitates electronic communication among all health care providers – including hospitals, GPs, specialists, laboratories, local authorities, and home care services. For example, all GPs maintain electronic health records and nearly all GPs use them to exchange records (98%), to order prescriptions at pharmacies (99%), to receive laboratory test results from hospitals (100%), and to send referrals to hospitals (97%), medical specialist clinics (100%), and psychologists (100%).5

Many Danish digital solutions have won international acclaim (Table 3).5 Denmark, thus, has a solid foundation for further digitization of the health care system. A new national strategy for “digital health” has been launched to advance sustainable development of the Danish health care system.15 The strategy includes 27 initiatives within five main areas: engaging citizens as active partners; ensuring timely knowledge exchange; developing the field of population health and prevention; providing excellent data security to win trust; and implementing a flexible digital health care infrastructure.15 Besides increasing the efficacy of health care delivery, the information recorded and collected during digitized workflows feeds on a daily basis into Danish population-based data sources.

Table 3.

Key IT solutions within the Danish health care system

| IT solution | Description |

|---|---|

| MedCom3 system | Digitizes much of the communication within the health system. |

| Health data network | Secures electronic communication among all health care providers. |

| National e-health portal | A National health web portal (sundhed.dk) that gives residents access to their own medical data from national health databases, electronic health records, and medication registries. These data can also be accessed by the patient’s GP and hospital physicians. |

| Electronic medical records | Provides a complete integrated IT workplace for hospital clinicians that integrates patient records, administrative data, medication use, bookings, and various test results (eg, laboratory, pathology, radiology, microbiology results). It improves the efficiency of clinical processes and workflows, treatment continuity, and patient safety. There are two types of systems: Systematic Columna Clinical Information System (MidtEPJ) used in the Central, North, and Southern Regions and Epic’s Healthcare Platform (Sundhedsplatformen) used in Region Zealand and the Capital Region. Records are automatically and instantly shared across Regions with similar systems. |

| Shared medication record | Provides citizens and health care professionals, in both the primary and secondary health care sector, access to a complete electronic record of each citizen’s current prescription medications. This system simplifies communication concerning medication among health care providers and reduces the risk of prescribing inappropriate medications. |

| Telemedicine | The 2012 National Telemedicine Action Plan operates five specific telemedicine initiatives, which form the basis for a telemedicine program to pioneer future telemedicine initiatives. A national infrastructure for telemedicine has been established as part of a planned large-scale implementation of telemedicine throughout the country. This infrastructure includes standards and relevant reference architectures spanning the entire health care system, covering data measurement, video, questionnaires, and images. |

Data regulation

As part of a reform entitled “visibility of results”, a Health Data Program was established in 2014 to create “better health care through better use of data”. Danish regulations make electronic health care data accessible for clinical trials and other research projects, if the following basic requirements are met: demonstrated importance to society; lawful, secure, and safe handling and use of data; and respect for individuals’ right to privacy. Approval from an Ethics Committee may be needed to conduct research. The Danish Data Protection Agency safeguards that legal requirements bearing on research are followed.

Data linkage and follow-up

A key feature facilitating use of Danish registries and databases for research is the possibility of technically simple, cost-effective, and exact individual-level record linkage among all data sources. Linkage is achieved using a unique 10-digit personal identifier [Central Personal Register (CPR) number],16 assigned at birth or upon immigration by the Danish Civil Registration System to all persons residing in Denmark. Use of the Danish Civil Registration System as a research tool has been described in detail previously;16 one of its major strengths is the possibility of lifelong follow-up with accurate censoring at emigration or death.16

Danish medical databases

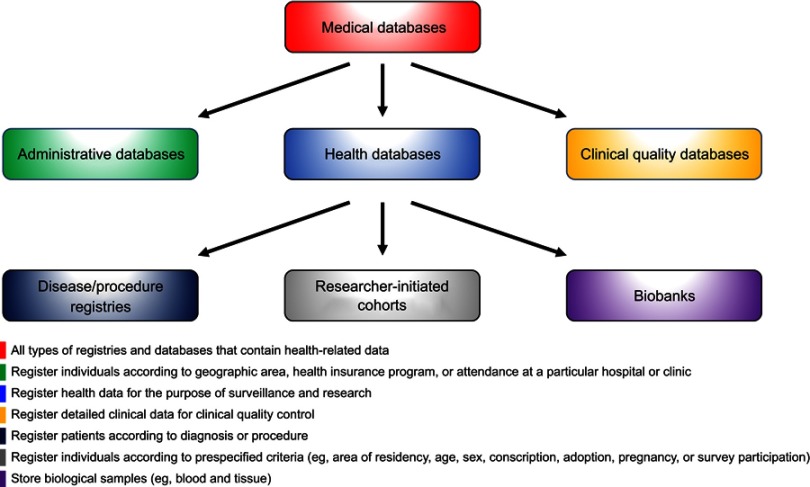

Denmark has a long tradition of routinely collecting data on many aspects of life and health in a multitude of registries and databases with population coverage. Examples of the types of data routinely generated during health care contacts are provided in Table 4. Each registry or database covers all residents in its geographical area (eg, Western Denmark17,18 or Denmark as a whole19) within a given time period. Total population registries, such as the Civil Registration System, contain data on all inhabitants in Denmark.20 Other registries cover all members of the Danish population with a given set of traits, exposures, or events, and hence are population-based registries.20 Medical database is the term used for all types of registries and databases that contain health-related data.21 There are three types of medical databases in Denmark: administrative databases, health databases, and clinical quality databases (Figure 4). While a historic overview of all Danish medical databases can be found in Supplementary Table S1, we will in the following detail the spectrum of the available data.

Table 4.

Health care contacts and main sources of routinely collected health data in Denmark

| Type of data source | Examples of key databases | Health care contacts | Selected variables* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Administrative databases | Danish Civil Registration System16 |

|

|

| Danish Registry of Causes of Death22 |

|

|

|

| Danish National Patient Registry19 |

|

|

|

| Danish National Psychiatric Central Research Registry83 |

|

|

|

| Danish National Prescription Registry31† |

|

|

|

| Laboratory Information Systems Database24 |

|

|

|

| Health databases | Danish Cancer Registry41 |

|

|

| Danish Medical Birth Registry84 |

|

|

|

| Danish National Pathology Registry58 |

|

|

|

| Clinical quality databases59,60 | ~100 databases of diseases or procedures |

|

|

Notes: *The unique 10-digit Central Personal Register (CPR) number is used to identify persons in all data sources.

†Similar variables registered in the Danish National Health Service Prescription Database.86

Abbreviations: ATC code, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical code; DDD, defined daily dose.

Figure 4.

Classification of medical databases.

Table S1.

Danish administrative, health, and clinical quality databases

| Decade | Type of registry | Coverage period (year) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| From | Nationwide | To | ||

| Administrative databases | ||||

| 1930s | Danish Road Traffic Accidents Registry1 | 1930 | 1930 | Ongoing |

| 1840s | Registry of Causes of Death2 | 1943* | 1943 | Ongoing |

| 1960s | Danish Civil Registration System3 | 1968* | 1968 | Ongoing |

| Danish Psychiatric Central Research Registry4 | 1969* | 1969 | Ongoing | |

| 1970s | Danish Registry of Suicide1,2 | 1970 | 1970 | 1998 |

| Danish Mortality and Occupation Database1 | 1970 | 1970 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Income Statistics Registry5 | 1970 | 1970 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Registry of Pension Statistics1 | 1970 | 1970 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Population Statistics Registry1 | 1971 | 1971 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Population Education Registry6,7 | 1973 | 1973 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Registry for Work-related Accidents and Diseases8 | 1973 | 1973 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Student Registry6 | 1974 | 1974 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Employment Classification Module (AKM)9 | 1976 | 1976 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Central Registry of Buildings and Dwellings (BBR)10 | 1976 | 1976 | Ongoing | |

| Danish National Patient Registry (DNPR)11 | 1977 | 1978 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Academic Achievement Registry6 | 1977 | 1978 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Unemployment Statistics Registry1 | 1979 | 1979 | Ongoing | |

| 1980s | Integrated Database for Labour Market Research (IDA)9 | 1980 | 1980 | Ongoing |

| Danish Registry-based Labour Force Statistics (RAS)9 | 1981 | 1981 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Authorisation Registry1 | 1982 | 1982 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Sickness Benefits Statistics Registry1 | 1983 | 1983 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Labour Force Survey9 | 1984 | 1984 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Coherent Social Statistics1 | 1984 | 1984 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Social Research Registry1 | 1989 | 1989 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Registry for Suicide Attempts12 | 1989 | 1989 | Ongoing | |

| 1990s | Danish Hospital Utilisation Registry1 | 1990 | 1990 | Ongoing |

| Danish National Health Insurance Service Registry13 | 1990 | 1990 | Ongoing | |

| Establishment-related Employment (ERE) Statistics9 | 1990 | 1990 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Database for Public Transfer Payments (DREAM)14 | 1991 | 1991 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Patient Compensation Association Database15 | 1992 | 1992 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Registry of Preventive Measures1 | 1994 | 1994 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Registry for Labour Market Policy Measures (AMFORA)1 | 1994 | 1994 | Ongoing | |

| Danish National Prescription Registry16 | 1995 | 1995 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Registry of Drug Abusers Receiving Treatment1 | 1996 | 1996 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Online Drug Use Statistics (MEDSTAT)17 | 1996 | 1996 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Social Pensions Registry1 | 1996 | 1996 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Adult Education and Continuing Training Registry6 | 1997 | 1997 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Children’s Database1 | 1997 | 1997 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Registry of Municipal Health Services1 | 1997 | 1997 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Clinical Laboratory Information System18 | 1997 | 2015 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Registry of Coercive Measures in Psychiatric Treatment1 | 1999 | 1999 | Ongoing | |

| Health databases | ||||

| Disease/procedure registries | ||||

| 1930s | Danish von Hippel-Lindau (vHL) Registry19 | 1930 | 1930 | 2010 |

| Danish Tuberculosis Registry20 | 1936 | 1936 | 1987 | |

| 1940s | Danish Huntington’s Disease Registry (DHR)19,21 | 1940 | 1940 | Ongoing |

| Danish Cancer Registry (DCR)22 | 1943 | 1943 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Multiple Sclerosis Registry23 | 1948 | 1948 | Ongoing | |

| 1950s | Danish National Cerebral Palsy Registry24 | 1950 | 1995 | 2007 |

| Danish Registry for Escherichia and Klebsiella Surveillance25 | 1959 | 1959 | Ongoing | |

| 1960s | Danish Cytogenetic Registry19 | 1960 | 1960 | Ongoing |

| Danish Registry of Congenital Heart Disease26 | 1963 | 1963 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Porphyria Registry19 | ~1969 | ~1969 | Ongoing | |

| 1970s | Danish Polyposis Registry27 | 1971 | 1971 | Ongoing |

| Danish Central Odontological Registry (SCOR)28 | 1972 | 1972 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Registry of Legally Induced Abortions29 | 1973 | 1973 | 1994 | |

| Danish Medical Birth Registry30 | 1973* | 1973 | Ongoing | |

| 1980s | Danish Fertility Database29 | 1980 | 1980 | Ongoing |

| Danish Cholecystolithiasis Survey31 | 1982 | — | Ongoing | |

| Danish Registry of Congenital Malformations32 | 1983 | 1983 | 1995 | |

| Danish Family Archive for Genetic Eye Diseases19 | 1985 | 1985 | Ongoing | |

| 1990s | Danish National Registry on Regular Dialysis and Transplantation (NRDT)33 | 1990 | 1990 | Ongoing |

| Danish Retinitis Pigmentosa Registry19 | 1990 | 1990 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colorectal Cancer (HNPCC) Registry19 | 1991 | 1995 | Ongoing | |

| Danish In Vitro Fertilisation Registry29 | 1994 | 1994 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Obstetric Registry34 | 1996 | — | Ongoing | |

| Danish HIV Cohort Study35 | 1998 | 1998 | Ongoing | |

| Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer (HBOC) Registry19 | 1999 | 1999 | Ongoing | |

| Western Denmark Heart Registry36,37 | 1999 | — | Ongoing | |

| 2000s | Danish Collaborative Bacteraemia Network (DACOBAN) database38 | 2000 | — | 2011 |

| Danish Cystic Fibrosis Patient Registry19 | 2001 | 2001 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Cancer in Primary Care (CaP) cohort39 | 2004 | — | 2010 | |

| Danish Heart Statistics40 | 2006 | 2006 | Ongoing | |

| Danish National Diabetes Registry41 | 2006 | 2006 | Ongoing | |

| 2010s | Danish National Type 2 Diabetes (DD2) Cohort42 | 2010 | 2010 | Ongoing |

| Danish Hereditary Angioedema Registry19 | 2011 | 2011 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Clinical Registry of People with Chronic Back Pain (SpineData)43 | 2011 | — | Ongoing | |

| Researcher-initiated cohorts | ||||

| 1870s | Danish Twin Registry44 | 1870 | 1870 | Ongoing |

| 1920s | Danish Adoption Registry45,46 | 1924 | 1924 | 1947 |

| 1930s | Copenhagen School Health Records Registry47 | 1936 | — | 2005 |

| 1950s | Danish Multi-Generation Registry (MGR)3,48 | 1953 | 1953 | Ongoing |

| Danish Conscription Registry Data (DCRD)49 | 1957† | 1957† | 2015† | |

| Copenhagen Perinatal Cohort50 | 1959 | — | 1961 | |

| Copenhagen Infant Health Visitor Records (IHVR)51 | 1959 | — | 1967 | |

| 1960s | Glostrup Population Studies52 | 1964 | — | Ongoing |

| Danish Longitudinal Survey of Youth53 | 1968 | 1968‡ | Ongoing | |

| Health Information System for the Central Denmark Region54 | 1968 | — | Ongoing | |

| 1970s | Copenhagen City Heart Study (Osterbro Study)55,56 | 1976 | — | 2003§ |

| 1980s | Health Habits for Two (HHf2)57 | 1984 | — | 1987 |

| Aarhus University Prescription Database58 | 1989 | — | 2016 | |

| Aarhus Birth Cohort (ABC)59 | 1989 | — | Ongoing | |

| 1990s | Odense Pharmacoepidemiological Database (OPED)60 | 1990 | — | Ongoing |

| Copenhagen Puberty Study61 | 1991 | — | 2008 | |

| Diet, Cancer, and Health Study62 | 1993 | — | Ongoing | |

| Danish Longitudinal Survey of Children (DALSC)63 | 1996 | 1996‡ | Ongoing | |

| Danish National Birth Cohort (DNBC or Better health in generations)64 | 1996 | 1999‡ | Ongoing | |

| Copenhagen Male Reproductive Health Study65 | 1996 | — | 2010 | |

| Danish Longitudinal Study on Ageing66 | 1997 | 1997‡ | Ongoing | |

| 2000s | Copenhagen Prospective Studies on Asthma in Childhood (COPSAC)67 | 1998 | — | Ongoing |

| Copenhagen County Child Cohort (CCCC2000)68 | 2000 | — | 2000 | |

| Copenhagen Primary Care Differential Count (CopDiff) database69 | 2000 | — | 2010 | |

| ”How are you” survey70 | 2001 | 2010‡ | Ongoing | |

| General Practice Patient List Database71 | 2002 | 2002 | Ongoing | |

| Copenhagen General Population Study (CGPS) (Herlev/Osterbro Study)72 | 2003 | — | Ongoing | |

| Danish National Health Service Prescription Database73 | 2004 | 2004 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Health Examination Survey (DANHES)74,75 | 2007 | 2010‡ | Ongoing | |

| Danish Web-based Pregnancy Planning Study (Soon-Pregnant)76 | 2007 | — | Ongoing | |

| 2010s | Danish Blood Donor Study (DBDS)77 | 2010 | 2010 | Ongoing |

| Odense Child Cohort (OCC)78 | 2010 | — | 2012 | |

| Danish General Suburban Population Study (GESUS)72 | 2010 | — | Ongoing | |

| Danish Functional Disorders (DanFunD) cohort79 | 2011 | — | 2015 | |

| Copenhagen Baby Heart80 | 2016 | — | 2018 | |

| Copenhagen Mini-puberty Cohort | 2016 | — | 2019 | |

| Lolland-Falster Health Study (LOFUS)81 | 2016 | — | Ongoing | |

| Biobanks | ||||

| 1990s | Danish National Pathology Registry82 | 1968 | 1997 | Ongoing |

| 2000s | Danish Cancer Biobank83 | 2009 | 2009 | Ongoing |

| 2010s | Danish National Biobank Registry84|| | 2012 | 2012 | Ongoing |

| Danish Rheuma Biobank83 | 2014 | 2014 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Blood Donor Biobank83 | 2017 | 2017 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Genetic Biobank83 | ~2019¶ | ~2019¶ | Ongoing | |

| Danish Diabetes Biobank83 | ~2019¶ | ~2019¶ | Ongoing | |

| Clinical quality databases | ||||

| 1960s | Danish Head and Neck Cancer Database (DaHanCaData)85 | ~1960 | 1971 | Ongoing |

| Danish Nephrology Registry (DNSL)86 | 1964 | 1990 | Ongoing | |

| 1970s | Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group (DBCG)87 | 1977 | 1977 | Ongoing |

| 1980s | Danish Pacemaker and ICD Registry88 | 1982 | 1982 | Ongoing |

| Danish National Lymphoma Registry89** | 1982 | 2000 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Testicular Cancer Database (DaTeCaData)90 | 1984 | 1984†† | Ongoing | |

| Danish Childhood Cancer Registry91 | 1985 | 1985 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Melanoma Database92 | 1985 | 1985 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Vascular Registry (Karbase)93 | 1989 | 1989 | Ongoing | |

| 1990s | Danish Colorectal Cancer Group Database (DCCG)94 | 1994 | 2001 | Ongoing |

| Danish Hip Arthroplasty Registry95 | 1995 | 1995 | Ongoing | |

| Danish HIV Cohort Study (DANHIV)35 | 1995 | 1995 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Multiple Sclerosis Treatment Registry96 | 1996 | 1996 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Registry for Childhood and Adolescent Diabetes (DanDiabKids)97‡‡ | 1996 | 2015 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Knee Arthroplasty Registry98§§ | 1997 | 2006 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Transfusion Database (DTDB)99 | 1997 | 2007 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Inguinal Hernia database100 | 1998 | 1998 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Heart Registry101 | 1998 | 2000 | Ongoing | |

| Danish National Database for Geriatrics102 | 1998 | 2005 | Ongoing | |

| 2000s | Danish National Acute Leukemia Registry103** | 2000 | 2000 | Ongoing |

| Danish Lung Cancer Registry (DLCR)104 | 2000 | 2000 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Rheumatology Database (DANBIO)105 | 2000 | 2006 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Database for Hepatitis B and C106 | 2002 | 2002 | Ongoing | |

| Danish National Database for Contact Allergy88 | 2002 | 2002 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Multidisciplinary Hip Fracture Registry (DMHFR)88§§ | 2003 | 2003 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Stroke Registry107 | 2003 | 2003 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Schizophrenia Registry108 | 2003 | 2003 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Hysterectomy and Hysteroscopy Database (DHHD)109 | 2003 | 2003 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Esophagus, Cardia and Stomach Neoplasm Database (DECV)110 | 2003 | 2003 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Heart Failure Registry111 | 2003 | 2005 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Registry of Diabetic Retinopathy (DiaBase)112‡‡ | 2003 | 2010 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Cerebral Palsy Follow-up Program113 | 2003 | 2017 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Database for Emergency Surgery114 | 2004 | 2004 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Anesthesia Database115 | 2004 | 2004 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Head Trauma Database88 | 2004 | 2004 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Shoulder Arthroplasty Registry116§§ | 2004 | 2006 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Adult Diabetes Registry117‡‡ | 2004 | 2006 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Knee Ligament Reconstruction Registry118§§ | 2005 | 2005 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Gynecological Cancer Database (DGCD)119 | 2005 | 2005 | Ongoing | |

| Danish National Multiple Myeloma Registry (DaMyDa)120** | 2005 | 2005 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Myelodysplastic Syndrome Database103** | 2005 | 2005 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Intensive Care Database (DID)121 | 2005 | 2005 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Early Pregnancy and Abortion Database (TiGrAb)88 | 2006 | 2006 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Cholecystectomy Database (DCD)122 | 2006 | 2006 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Urogynaecological Database (DugaBase)123 | 2006 | 2007 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Quality Database for Mammography Screening124 | 2007 | 2007 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Biological Treatment in Danish Dermatology (DermBIO)88 | 2007 | 2009 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Stoma Database125 | 2007 | — | Ongoing | |

| Nordic Database for Rare Disease (RareDis)19 | 2006 | 2007 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Registry of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (DRKOL)126 | 2008 | 2008 | Ongoing | |

| Danish National Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Registry127** | 2008 | 2008 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Ablation Database (Ablation.dk)88 | 2008 | 2008 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer Dermatology Database128 | 2008 | 2011 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Depression Database (DDD)129 | 2008 | 2011 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Fetal Medicine Database (FØTO)130 | 2008 | 2011 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Quality Database for Cervical Cancer Screening131 | 2009 | 2009 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Sarcoma Database132 | 2009 | 2009 | Ongoing | |

| Danish National Database for Obstructive Sleep Apnea (NDOSA)133 | 2009 | 2009 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Neuro-Oncology Database (DNOR)134 | 2009 | 2009 | Ongoing | |

| 2010s | Danish National Quality Database for Births135 | 2010 | 2010 | Ongoing |

| Danish Prostate Cancer Database (DaProCaData)136 | 2010 | 2010 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Bariatric Surgery Registry (DFR)88 | 2010 | 2010 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Renal Cancer Group Database (DaRenCaData)137 | 2010 | 2010 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Organ Donation Database88 | 2010 | 2010 | Ongoing | |

| Danish National Chronic Myeloid Neoplasia Registry138** | 2010 | 2010 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Palliative Care Database (DPD)139 | 2010 | 2010 | Ongoing | |

| Danish National Quality Registration for Visual Impairment (Websyn)88 | 2010 | 2010 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Penile Cancer Database (DaPeCaData)140 | 2011 | 2011 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Diabetes Database112 | 2011 | 2011 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Ocular Oncology Database (DOOG)88 | 2011 | 2011 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Pancreatic Cancer Database (DPCD)141 | 2011 | 2011 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Fracture Database142 | ~2011 | 2015 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Bladder Cancer Database (DaBlaCaData)143 | 2012 | 2012 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Database for Acute and Emergency Hospital Contacts (DDAEHC)144 | 2013 | 2013 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Liver and Bile Duct Cancer Database88 | 2013 | 2013 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Back Pain Registry (COP-Spine)88 | 2013 | 2013 | Ongoing | |

| Danish ADHD Database88 | 2013 | 2013 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Cardiac Rehabilitation Database145 | 2013 | 2015 | Ongoing | |

| Danish In-hospital Cardiac Arrest Registry (DANARREST)146 | 2013 | 2017 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Colorectal Cancer Screening Database147 | 2014 | 2014 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Prehospital Emergency Medical Service Registry148 | 2014 | 2014 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Rapid Response System (RRS) Database149 | 2014 | — | Ongoing | |

| Danish Registry for Biological Therapy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (BioIBD)150 | 2015 | 2015 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Trauma Registry88 | 2015 | 2015 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Asthma Database151 | 2015 | 2015 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Registry for Adolescents with Acquired Brain Injury (DRUE)88 | 2015 | 2015 | Ongoing | |

| Danish National Quality Database for Spinal Cord Injury88 | 2015 | 2015 | Ongoing | |

| Danish National Quality Database for Newborns88 | 2016 | 2016 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Quality Database for Dementia (DanDem)88 | 2016 | 2016 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Atrial Fibrillation Database88 | 2016 | 2016 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Back Database88 | 2017 | 2017 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Registry for Acute Coronary Syndrome (DanAKS)88 | 2019 | 2019 | Ongoing | |

| Danish Forensic Psychiatric Quality Database88 | ~2019¶ | ~2019¶ | Ongoing | |

| Danish Familial Hypercholesterolaemia Database88 | ~2019¶ | ~2019¶ | Ongoing | |

Notes: The authors have made every effort to maximize completeness of this list of medical databases; however, it is likely that some databases were inadvertently omitted. Should this be the case, the authors will be grateful for any suggestions for adding such databases to the list. *Electronic datasets are available in the coverage periods shown, but manual registered data supplement the Registry of Causes of Death on causes of death since 1875,2 the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Registry on psychiatric diagnoses since 1906 (nationwide since 1938),4 the Danish Civil Registration System on population registration since 1924,3 and the Danish Medical Birth Registry since 1968.29 †The Danish Conscription Registry Data (birth year: 1929–1998/examination year: 1957–2015) consists of four subregistries with different birth year/examination periods: Danish Conscription Database (1929–60/1957–84), National Archives Database (1940–97/1987–2011), Danish Defence Personnel Organisation Database (1950–88/1995–2005), and Danish Conscription Registry (1973–98/2006–15).49 ‡Nationally representative (and not necessarily nationwide) from this year onwards. §After 2003, the Copenhagen City Heart Study (Osterbro Study)51,52 continued as part of the larger Copenhagen General Population Study (Herlev/Osterbro Study).72 ||As of January 2019, the registry stores >25.3 million samples from 5.7 million people and includes the following biobanks: Danish National Biobank (including 1 million samples each year, phenylketonuria blood spot cards from all newborn Danes since 1982 (>2 million samples), and the State Serum Institute legacy collections (>4 million samples); the Danish National Birth Cohort (>600,000 samples from pregnant mothers and their children); the Copenhagen Hospital (Rigshospitalet) biobank (50,000 samples each year); the Diet, Cancer and Health Study (samples from >57,000 participants); Patobank (17 million samples from hospitals); Danish Cancer Biobank (blood and tissue samples from Danish cancer patients); Region Zealand biobank (samples from LOFUS); Danish Twin Registry (samples from >86,000 twin pairs); Odense Patient data Explorative Network’s research samples from the Region of Southern Denmark); and samples from COPSAC, DD2, and DBDS. ¶Under establishment. **Subregistry of the Combined Danish Hematology Database. ††Nationwide health database between 1984–2007 and nationwide clinical quality database since 2013. ‡‡Subregistry of the Danish Diabetes Database. §§Subregistry of the Combined Danish Orthopaedic Database.

Administrative databases

Most health care data used for research originate from administrative databases, which register individuals according to their residency in a specified geographic area, membership in a health insurance program, or attendance at a particular hospital or clinic – irrespective of the patients’ diseases and the procedures used to treat them.21 Demographic, migration, and vital statistics data have been registered electronically on a daily basis since 1968 in the Danish Civil Registration System.16 Non-electronic population registrations date further back to 1924.16 Specific causes of death have been recorded in the Danish Registry of Causes of Deaths since 1943.22 Suicide and suicide attempts are recorded separately in the Danish Registry of Suicide (since 1970)22 and Registry for Suicide Attempts (since 1989).23 Hospital encounters (with admission type and dates, discharge diagnoses, and procedures) have been registered in the Danish National Patient Registry since 1977.19 Laboratory results are tracked by the Danish Clinical Laboratory Information System, with coverage of selected Regions since 1990 and nationwide since 2015.24 The Danish National Health Service Registry contains data from health contractors in the primary health sector, including information about patients, providers, and referral to health services.25 These data enable epidemiologists to control for health care-seeking behavior in their research.26 However, while this Registry includes such information as vaccination, it has minimal clinical information.25 Since 1957, conscription registries have collected data on height, weight, cognitive ability (as measured by the Børge Prien’s test), and chronic diseases that could preclude military service (eg, asthma, epilepsy, or spinal osteochondrosis).14 This database, thereby, enables studies of life-long outcomes associated with BMI and cognition in young adulthood.27–30

The Danish National Prescription Registry contains detailed individual-level data on prescriber, patient, and products for all outpatient prescriptions dispensed since 1995.31 Aggregate data on sales of drugs and number of users in the primary sector are freely available online.32 Due to the opportunity for partial cost reimbursement to patients and frequent prescription together with other drugs, a sizeable proportion of over-the-counter drugs, such as low-dose aspirin and ibuprofen, are obtained by prescription and, therefore, also generate records in the Danish National Prescription Registry.33 Treatments dispensed during hospital stays do not generate records in this Registry, however. Such treatments include all cancer medicines, which are dispensed nearly exclusively at hospitals to free patients from copayments. Use of some cancer treatments, especially if they are expensive, may be recorded in the Danish National Patient Registry.19

Labor market and socioeconomic data are used increasingly in epidemiological research, either as exposures, for control of confounding, or as study endpoints. Denmark has numerous individual databases on education,34 income,35 employment,36 and housing37 (Table S1). Most information essential for research has been combined in the Integrated Database for Labour Market Research,38 which includes detailed data on individuals (eg, family, marital status, education, work experience, unemployment, and income), employment type (eg, position title, full-time/part-time, hourly pay, seniority, and changes in employment), and workplaces and companies (eg, date of establishment, industry, and location). Another data source, the DREAM database,39 allows weekly follow-up of individuals receiving any public transfer payment, and, therefore, allows for follow-up of social and economic consequences of diseases. An example is return to the workforce after cardiac arrest.40

Health databases

Health databases collect health data for the purpose of surveillance and research. The spectrum of health databases is wide and covers disease/procedure registries, researcher-initiated cohorts, and biobanks.

Disease registries capture patients at the time of disease detection (typically first-time diagnosis or initiation of disease-defining treatment).21 Procedure registries capture patients undergoing a particular procedure in a defined population.21 Examples of disease or procedure registries include the Danish Cancer Registry41 (incident primary malignancies) and the Western Denmark Heart Registry (cardiac interventions).17,18 Danish disease/procedure registries also cover genetic tests (eg, the Cytogenetic Registry42), fertility treatments (the Danish Fertility Database43 and the In Vitro Fertilisation Registry44), abortions (Registry of Legally Induced Abortions45), births (Medical Birth Registry46), and congenital diseases (eg, the Danish Cerebral Palsy Registry,47 the Danish Registry of Congenital Heart Disease,48 and the Danish Registry of Congenital Malformations49).

Researcher-initiated cohorts may include individuals according to prespecified criteria other than diseases and procedures, such as area of residency, age, sex, pregnancy planning, adoption, military conscription, prescription redemption in specified geographic area, or survey participation.

Thus, researcher-initiated cohorts may 1) be derived from existing administrative databases for the purpose of research (eg, the regional prescription databases) or other health databases (eg, the Danish Twin Registry50); 2) represent classic cohort studies with prospective enrollment and follow-up (eg, the Copenhagen City Heart Study, which has been following 23,891 women and men of 20 years or older since 1976;51,52 the Diet, Cancer and Health Study, which has been following 57,053 cancer-free participants aged 50–64 years since 1993;53 and the Danish National Birth Cohort, which has followed 100,000 pregnant women and their offspring since 1996);54 and 3) include participants of population surveys (eg, the ”How are you” survey, which commenced in 2006,55 and the Danish Health Examination Survey, which commenced in 2007).56 Population surveys provide detailed data on, eg, lifestyle factors and behaviors, which are not recorded in most other data sources. Surveys, cross-sectional by design, become longitudinal when follow-up questionnaires/examinations are carried out. Even in the absence of pre-planned follow-up, Danish survey participants are effectively cohorts with lifelong follow-up (containing baseline survey data) by virtue of linkage to any other data source for additional baseline data and outcomes.16,19

The renowned Danish biobanks play a key role in research seeking to advance precision medicine. The Danish National Biobank, established in 2012 at the State Serum Institute, has consolidated information on all biological specimens collected in the national health care system into a single registry – the Danish National Biobank Registry – permitting researchers to identify biological material available for each disease through an online search function (detailed in Table S1).57 In addition, the Danish Regions maintains the “Bio and Genome Bank Denmark”, the parent registry for individual biobanks dedicated to blood donation, genetics, diabetes, rheumatology, cancer, and pathology. Importantly, the Danish National Pathology Registry contains nationwide records for all pathology specimens analyzed in Denmark since 1997.58

Clinical quality databases

Clinical databases contain information regarding patients’ medical histories, laboratory and radiology findings, and treatment.21 The data are collected during the course of routine clinical care, but are also often used to assess the effectiveness of treatments and adverse effects and to address other research questions.21 A special group of clinical databases are the clinical quality databases, which collect detailed clinical data for clinical quality control.21 The Danish clinical quality databases are regulated by the government and funded by the Regions. There are close to 100 of these databases, and more are being established.59 Data on quality indicators and standards for good clinical practice are compiled and analyzed by health care professionals. A report containing analyses and recommendations for each database is published on a yearly basis to ensure continued quality improvement. The Danish clinical quality databases have been described in detail in a recent review series.60 A Danish Clinical Quality Databases agency oversees the databases, with the main focus of facilitating continuous improvement of the databases and their utilization from clinical, administrative, and research points of view.

Data not available

While the Danish data sources are rich and in many ways unique in an international context, there remains room for improvement. Clinical data from general practice are not routinely collected in Denmark, in contrast to several other European countries, eg, in the UK (CPRD, THIN, and QResearch),61–63 Norway (KUHR),64 Sweden (eg, SPCCD),65 Finland (AvoHILMO),66 Netherlands (PHARMO),67 or Spain (SIDIAP and BIFAP).68 The Danish National Patient Registry does not capture diagnoses made in general practice unless a patient has a hospital encounter with that disease. A database of diagnoses from general practice was established for a brief period in 2007,69 but was closed due to uncertainty about its legal foundation. In some cases, it is possible to identify diseases not leading to a hospital encounter from other databases, most commonly, by a treatment proxy from prescription data (eg, herpes zoster, diabetes, depression, or hypertension)26,70,71 or by means of laboratory results.24

In addition, lifestyle variables are generally missing from most databases containing routinely collected data. While data on lifestyle factors can be obtained from various population health surveys, these sources are not nationwide or continuously updated. As well, results of examinations and procedures are not available in the Danish National Patient Registry.19 Finally, services provided by some components of the Danish health care system, such as home nursing, home care service, and rehabilitation, are not registered systematically and, therefore, rarely used for research.

Data quality

Validity

Data quality is typically measured by validity and completeness. Validity, in the context of health research, refers to the extent to which a variable measures the intended health condition or event. The positive predictive value (PPV) of a health record is the most frequently reported validity measure, defined as the proportion of patients registered with a disease who truly have the disease. Medical record review is a common reference standard used in validation studies to confirm the presence or absence of a disease.19 Other types of reference standards include patient self-reports, physicians’ reports, autopsy reports, and alternative data sources with presumably higher data quality (such as clinical quality data, laboratory data, and pathology data).19

In general, data in health and clinical quality databases have high validity and completeness, because they are collected prospectively with the aim of quality control and clinical care. Consultants within each medical field register the data in clinical quality databases, further increasing the accuracy of the data. Although also registered prospectively, the validity of clinical data in the administrative databases may vary considerably among databases and within each database. On one hand, detailed data on education,34 income,35 social benefits,35 housing,37 blood tests,24 dispensed medications,31 ethnicity (country of birth of immigrants and descendants),72 and all-cause mortality16 are considered complete and valid. On the other hand, the validity of clinical data extracted from hospital records19 and death certificates22 depend on many factors, most importantly the individual variable registered, time period studied, and the level of specialization of the reporting department.19

Because the Danish National Patient Registry is among the most widely used administrative databases in epidemiological research, continuous efforts are made to validate its data. Three categories of validation studies have been performed:

Government-initiated systematic validation of personal demographic data, hospital admission data, and overall diagnoses within different clinical specialties.73–75 Such validation studies, performed by the Danish Health and Medicines Authority, have shown that data on admission/discharge dates, hospital/department codes, and CPR numbers are accurate, whereas the PPV of disease codes varies between specialties and depends on inclusion of primary or secondary diagnoses and whether validation was done at the three- or five-digit level of the International Classification of Diseases.

Investigator-driven systematic validation of individual diagnoses, examinations, procedures, and surgery codes within a specific clinical specialty. Only a few examples exist, within the fields of cardiology76,77 and gynecology/obstetrics.78

Investigator-driven ad hoc validation of study-specific variables, the most common type of validation study. A bibliography of the validation studies is freely available.19

To increase PPV, variables used for research may incorporate, in addition to diagnostic codes, data such as admission type (acute vs elective), patient contact type (inpatient vs outpatient), specialty department, diagnostic specification (primary vs secondary diagnoses), procedures, in-hospital medical treatment, or medication proxies (eg, antidiabetic and antihypertensive drugs). The PPVs of health events included in the Danish National Patient Registry range from below 15% to 100%. This fact underscores the need to validate the specific variables used in a study, rather than drawing conclusions about their expected accuracy from findings for other variables included in a given registry.19

Completeness

Completeness refers to the proportion of true health events in the population correctly captured by a data source.21 Completeness of diseases can be measured in relation to all individuals in the general population or all patients admitted/treated for a specific disease. Completeness is largely determined by the registry’s sensitivity and depends on the amount of missing data. Ascertainment of completeness relative to the general population is often difficult. Because of its nationwide coverage, the Danish National Patient Registry is most often used to study disease occurrence. However, data completeness in this registry depends on hospitalization patterns and diagnostic accuracy. Thus, conditions such as myocardial infarction, stroke, or hip fracture, which should always lead to a hospital encounter, are consistently registered. In contrast, lifestyle risk factors (overweight, smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, and physical inactivity) and conditions treated primarily in primary care, such as osteoporosis, hypertension, or uncomplicated diabetes, are not.

Linkage to other routine registries can sometimes compensate for the Danish National Patient Registry’s incomplete capture of certain conditions. For instance, diabetes can be identified from the presence of at least one redeemed outpatient prescription for insulin or an oral antidiabetic drug in the Danish National Prescription Registry31 and/or by an inpatient or outpatient hospital diagnosis of type 1 or type 2 diabetes.79 Recent studies have supplemented the diabetes algorithm by using data on glycosylated hemoglobin A1c measurements from the Laboratory Database,24 by increasing specificity through exclusion of patients treated with metformin for polycystic ovarian syndrome,80 and by differentiating type 1 and type 2 diabetes using information on age at diagnosis combined with the presence of insulin monotherapy.79

Danish health statistics

Danish population-based registries provide health statistics of immense value for researchers, as well as for politicians, administrators, the media, the pharmaceutical industry, and others. Aggregated data on drug use and selected disease trends are freely available online.32 Key statistics characterizing the Danish population and the health care system are provided in Tables 5 and 6.8,81

Table 5.

Danish population statistics, 2014

| Population growth | |

| Population size, n | 5,627,235 |

| Live births, n | 56,870 |

| Deaths, n | 51,340 |

| Immigrants, n | 87,563 |

| Emigrants, n | 59,226 |

| Longevity and mortality | |

| Persons aged 65 years or older, % | 18 |

| Life expectancy at birth for men, years | 78.6 |

| Life expectancy at birth for women, years | 82.5 |

| Life expectancy at 65 years for men, years | 18.1 |

| Life expectancy at 65 years for women, years | 20.8 |

| Annual number of deaths per 1,000 population | 9.1 |

| Infant deaths per 1,000 population, n | 4 |

| Fertility and childbirth | |

| Average number of births per woman | 1.7 |

| Mean maternal age at first delivery, years | 29.1 |

Notes: Data from the Ministry of Health (http://www.sum.dk),5 Statistics Denmark (http://Statistikbanken.dk),81 and Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (https://data.oecd.org).8

Table 6.

Danish health care statistics, 2014

| Preventive care | |

| Children age ~1 year receiving measles immunization, % | 90 |

| Children age ~1 year receiving diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis immunization, % | 94 |

| Influenza vaccination rates in the population ≥65 years, % | 43 |

| Health care access | |

| Capacity in primary sector, number of residents per health professional | |

| General practitioners, n | 1,599 |

| Medical specialists, n | 6,237 |

| Dentists and dental hygienists, n | 2,408 |

| Physiotherapists, n | 4,223 |

| Chiropractors, n | 20,944 |

| Podiatrists, n | 5,990 |

| Psychologists, n | 6,643 |

| Capacity in public hospitals, residents per full-time employee | |

| Physicians, n | 365 |

| Nurses, n | 157 |

| Other health care professionals, n | 418 |

| Assistants, n | 550 |

| Others, n | 174 |

| Hospital beds per 1,000 residents, n | 2.7 |

| Waiting time for elective hospital surgery, mean days | 49 |

| Doctors per 1,000 residents, n | 3.7 |

| Health care utilization | |

| Physician consultations per residents, n | 4.5 |

| Primary sector | |

| Patients per 1,000 residents, n | 893 |

| Contacts per patient, mean | 11.3 |

| General practice | |

| Physical consultations during daytime per 1,000 residents, n | 3,843 |

| Telephone and e-mail consultations during daytime per 1,000 residents, n | 2,893 |

| Consultations after daytime hours per 1,000 residents, n | 482 |

| Public hospitals | |

| Patients per 1,000 residents, n | 674 |

| Hospitalizations per 1,000 residents, n | 1,133 |

| Outpatient contacts per 1,000 residents, n | 12,606 |

| Private hospitals, publicly funded care | |

| Patients per 1,000 residents, n | 9 |

| Hospitalizations per 1,000 residents, n | 10 |

| Outpatient contacts per 1,000 residents, n | 256 |

| Private hospitals, privately funded care | |

| Patients per 1,000 residents, n | 10 |

| Hospitalizations per 1,000 residents, n | 11 |

| Outpatient contacts per 1,000 residents, n | 228 |

| Non-psychiatric hospital, publicly financed | |

| Patients with hospitalizations per 1,000 residents, n | 121 |

| Hospitalizations per 1,000 residents, n | 204 |

| Average length of stay, days | 3.5 |

| Patients with outpatient contacts per 1,000 residents, n | 466 |

| Outpatient contacts per 1,000 residents, n | 2,291 |

| Psychiatric hospitals | |

| Patients per 1,000 residents, n | 25 |

| Contacts per 1,000 residents, n | 219 |

| Patients with hospitalizations per 1,000 residents, n | 4.5 |

| Hospitalizations per 1,000 residents, n | 8.2 |

| Average length of stay, days | 15 |

| Patients with outpatient contacts per 1,000 residents, n | 25 |

| Outpatient contacts per 1,000 residents, n | 211 |

| Recipients of home care services (personal and/or practical help), % ≥65 years | 12.2 |

Notes: Data from the Ministry of Health (http://www.sum.dk),5 Statistics Denmark (Statistikbanken.dk),81 and Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (https://data.oecd.org).8

The Danish population grew from 5.1 million in 1980 to 5.8 million in 2018. This population growth is in the lower range compared with other European countries. Although births exceed deaths, the average number of births per woman is only 1.7. Among the Nordic countries, Denmark has the highest rate of in vitro fertilization treatments, amounting to nine treatments per 1,000 women aged 15–49 years compared with approximately five per 1,000 women in neighboring countries.82

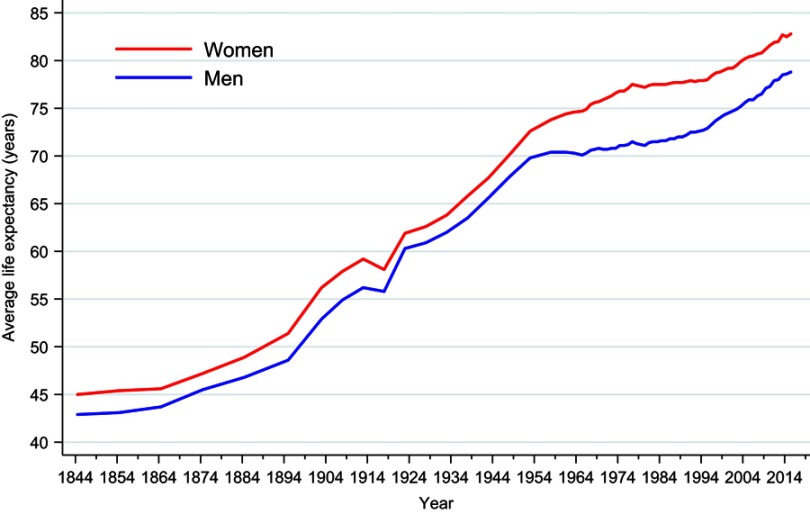

Longevity in Denmark has increased substantially over time, as shown in Figure 5. During 2014–2015, mean life expectancy was 78.6 years for men and 82.5 years for women. Almost 20% of the Danish population is currently above 65 years of age. However, the increase in life expectancy has been smaller than that in most other Western European countries. Mortality in Denmark is among the highest in the Nordic countries.82

Figure 5.

Sex-specific mean life expectancy at birth in Denmark, 1844–2014. StatBank Denmark.81

The annual number of physician consultations per resident in Denmark was 4.5 in 2014, comparable to other Nordic countries.8 Most persons (90%) have at least one contact with the primary health care system each year. The total number of primary care contacts, including those with GPs, medical specialists, dentists, and physiotherapists, was 58.1 million in 2014, corresponding to 11.3 contacts per person on average. Annually, approximately 13% of the population is hospitalized, and the average length of hospital stay is 3.5 days in non-psychiatric departments and 15 days in psychiatric departments. Danish health care data, thus, provide many important indicators of the health care system and characteristics of the underlying population.

Conclusions