Abstract

Salmonella enterica Newport (S. Newport), with phylogenetic diversity feature, contributes to significant public health concerns. Our previous study suggested that S. Newport from multiple animal-borne routes, with distinct antibiotic resistant pattern, might transmit to human. However, their genetic information was lacking. As a complement to the earlier finding, we investigate the relationship between each other among the hosts, sources, genotype and antibiotic resistance in S. Newport. We used the multilocus sequence typing (MLST) in conjunction with minimum inhibitory concentration of 16 antibiotics of globally sampled 1842 S. Newport strains, including 282 newly contributed Chinese strains, to evaluate this association. Our analysis reveals that sequence types (STs) are significantly associated with different host sources, including livestock (ST45), birds (ST5), contaminated water and soil (ST118), reptiles (ST46) and seafood (ST31). Importantly, ST45 contained most of (344/553) the multi-drug resistance (MDR) strains, which were believed to be responsible for human MDR bacterial infections. Chinese isolates were detected to form two unique lineages of avian (ST808 group) and freshwater animal (ST2364 group) origin. Taken together, genotyping information of S. Newport could serve to improve Salmonella source-originated diagnostics and guide better selection of antibiotic therapy against Salmonella infections.

Keywords: antibiotic resistance, bovine, plant, Salmonella Newport, sequence type, sources

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Salmonella enterica is among the global leading causes of bacterial foodborne illnesses, which poses a significant health and economic burden. Among the top three S. enterica serovars for human infections, the incidence of S. Newport infections in the US has increased by 27% from 1996 to 2001, while serovar Typhimurium and Enteritidis have decreased by 16% and 1% respectively (Havelaar et al., 2015). In the European Union (EU), S. Newport infections has remained stable over the decades with about 750 confirmed cases every year (EFSA et al., 2016, 2017). However, the corresponding disease burden in China remains unknown.

The consumption of contaminated beef or milk is believed to be the primary source for S. Newport infections, yet recent outbreaks were more frequently attributed to other sources, such as fresh produces, seafood, irrigation water or soil (Bell et al., 2015). Moreover, S. Newport has the ability to survive long term in the environment and colonize particular plants (de Moraes et al., 2018; You et al., 2006; Zheng et al., 2013) these S. Newport niches can serve as persistent or recurring sources for human infections. However, unlike other developed countries, S. Newport epidemics in China are largely unknown (Kuang et al., 2015; Paudyal et al., 2018), and the distinction between the Chinese and the US isolates remains obscure. Being a polyphyletic serovar, we hypothesize that strains from different sources have varied genetic properties, and thus represent distinct transmission routines for human infections.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

We used the results of MLST and broth micro-dilution minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) assay of 282 Chinese isolates with additional 50 from previous studies, to investigate the relationship of S. Newport isolates from various sources. We compared this with the findings on 1,510 isolates of other countries, especially from the US and the EU (Supporting information Table S1). The 16 antimicrobial drugs used in our MIC assay were Gentamicin, Kanamycin, Streptomycin, Ampicillin, Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, Ceftriaxone, Cefoxitin, Ceftiofur, Ciprofloxacin, Nalidixic acid, Chloramphenicol, Sulfamethoxazole, Tetracycline, Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, Azithromycin and Colistin. The results of MIC assay were interpreted according to the CLSI 2017 guidelines.

We grouped the strains based on their origin as: (a) humans (clinical patients), (b) livestock and their food products (mammals and avians) and (c) other sources (designated as non-livestock), including mainly isolates from fresh produces (plants), seafood or freshwater animals (cold-blooded animals), water-and-soil (environment) to evaluate the significance of source of origin of the bacteria for human infections. Strains were also categorized into three antibiotic categories: (a) pan-susceptible, (b) single-drug-resistance (SDR) or (c) multi-drug-resistance (MDR), defined as resistance to drugs of at least two different antimicrobial classes (Pan, Paudyal, Li, Fang, & Yue, 2018; Sangal et al., 2010).

3 |. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

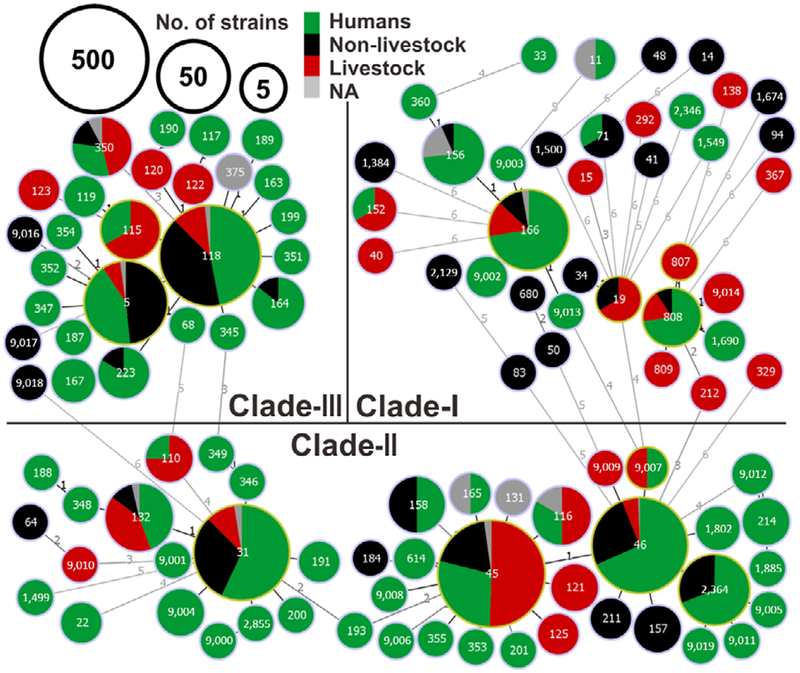

A total of 109 sequence types (STs) were identified in 1,842 isolates from 46 countries across seven continents. Five dominant STs, ST45 (31%), ST118 (20%), ST46 (13%), ST31 (12%) and ST5 (5%), represented 81% of the strains. A minimum spanning tree confirmed three lineages (Figure 1) as described previously (Sangal et al., 2010), and 34, 22 and four new STs were newly identified in Clade-I, -II and -III respectively.

FIGURE 1.

Global population structure based on MLST, of Salmonella Newport from 1,842 strains. The minimum spanning tree suggests three major clades; the number on each branch represents the number of polymorphic SNPs; the colours represent strain sources (humans in green, livestock in red, non-livestock source in black and unavailable or NA in grey). Circle sizes represents the number of strains studied for each ST and the identity of the STs is indicated by the number in each circle [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

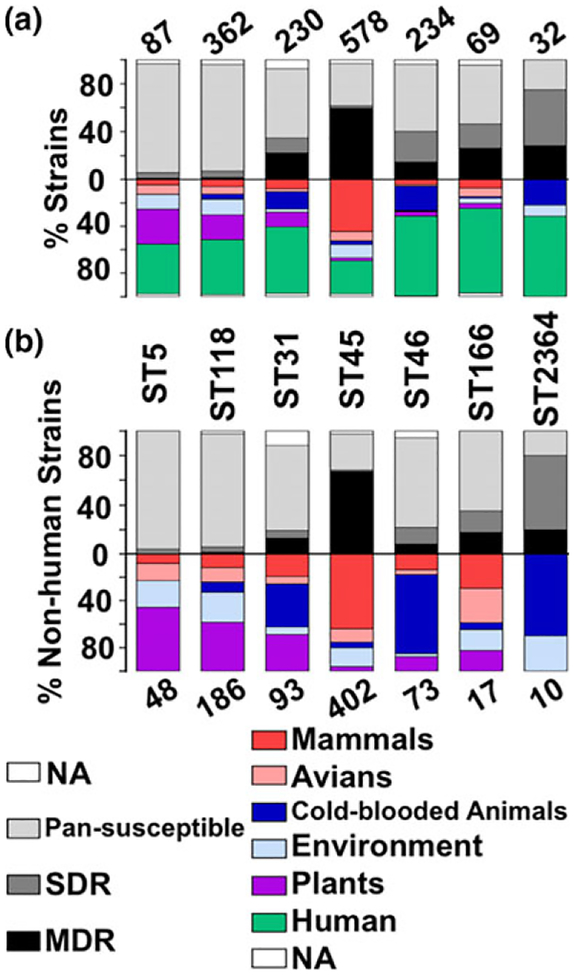

We found that non-human S. Newport isolates of Clade-III consisted mainly of non-livestock strains, including wild birds and freshwater animals. ST118 and ST5 were significantly associated with strains of non-livestock origin (χ2 test, p < 0.0001), with nearly fourfold and sevenfold more strains isolated from livestock (Figure 1). Contaminated plants (54%), and environment samples (31%, mainly water-and-soil) were the other predominant sources for non-livestock strains in this clade (Figure 2a). Interestingly, four of the seven avian isolates in ST5 were from wild birds, including seagulls. Wild birds have previously been implicated as the source of recurrent S. Newport outbreaks by direct contamination of food plants such as tomatoes, soil or irrigation water (Bell et al., 2015). Antibiotic resistance prevalence was low in strains of ST118 and ST5 (4.60%–5.25% SDR, 1.15%–1.66% MDR), compared to ST115 strains (16.7% SDR) from the same clade (Figure 2a), that were all from livestock as non-human source.

FIGURE 2.

(a) The histogram shows the antibiotic resistance profiles and percentage of all isolates of the dominant sequence types (ST5, ST118, ST31, ST45, ST46, ST166, ST2364). The number of isolates for each ST is above the histogram. The sources of the strains are indicated by different colors (light blue for environment, purple for plant, dark blue for cold-blooded animals, pink for avian and red for mammalian animals). Resistance profiles of each ST are shown in black or shades of grey (multiple drug resistance or MDR in black, single-drug resistance or SDR in dark grey, pan-susceptible in light grey, and unavailable data or NA in white). (b) The histogram shows the antibiotic resistance profiles and percentage of non-human isolates of the seven dominant sequence types. The layout of this histogram is the same as in Figure 2a except that positions of ST and the number of isolates for each ST is exchanged. For ST5, 54% (26/48) of the non-human isolates were from plants and 57% (4/7) of the avian strains were from wild birds. For ST118, 41% (77/186) of the non-human isolates were from plants and 26% (48/186) were from the environment. For ST31, all 34 cold-blooded animal isolates (37% of all non-human isolates) were from aquatic sources (freshwater product or seafood), such as fish and shrimp, and 31% (29/93) of the non-human isolates were from plants. For ST45, 76% (195/257) of the mammalian isolates were from bovines. For ST46, 67% (49/73) of the non-human isolates were from cold-blooded animals (CBA). For ST166, 59% (10/17) of the non-human isolates were from mammalian animals and avian, and 35% (6/17) were from environment and plants. For ST2364, all seven cold-blooded animal isolates (70% of all non-human isolates) were from freshwater product and all three environmental isolates were from river water [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

In Clade-II, ST45, ST46 and ST31 occupied 88% of strains (Figure 1). Livestock were the major non-human source for ST45 (χ2 test, ρ < 0.0001), with approximately two-thirds of the strains being of bovine origin (Figure 2b). In contrast, the major source for the two other STs (ST31 and ST46) had a non-livestock origin, and most strains originated from cold-blooded animals (49% and 82%) (χ2 test, p < 0.0001), including 11 of 49 ST46 strains being from reptiles. Interestingly, the cold-blooded animal strains in ST31 were aquatic animals (fish and shrimp). Thus, Clade-II is mainly populated by certain distinct sources for human infections, such as bovine (ST45), reptile associated cold-blooded animals (ST46), a well-known source for pediatric Salmonella infections (Walters et al., 2016) and seafood animals (ST31), an emerging source for disease outbreaks (Brands et al., 2005). Additionally, the relative number of MDR strains correlated to the number of livestock strains for each Clade-II STs (Figure 2a), confirming that S. Newport MDR phenotype relates to antibiotics usage in livestock production and persistence of MDR strains in the farm-animal source (Havelaar et al., 2015). Although Clade-I is highly diverse, it consisted of only 140 isolates (Figure 1). Notably, 58% of the livestock isolates and only 12% of the non-livestock isolates of Clade-I were either MDR or SDR, further supporting the findings with the other clades that livestock isolates are more likely to be antibiotic resistant than other isolates.

To further assess the geographic diversity, we conducted and used three-way comparisons among isolates from 332 Chinese isolates (Supporting information Figure S1), 871 US isolates (Supporting information Figure S2) and 639 isolates from other countries (Supporting information Figure S3). Most of the clade-III strains were of plant origin from the US while China had few isolates from this clade. All three regional groups shared a robust Clade-II, with China having the most and US the least. China had a unique ST2364 non-livestock group, most being from freshwater animals (7/10) and SDR or MDR. In Clade-I, a group consisting mostly of ST808, with ST9014, ST807, ST809, ST1690 strains with 30% being MDR, was also unique to China, and the non-human strains included avian strains. The newly identified Chinese lineages were linked mainly to avian ST808 and freshwater animal ST2364 indicating emerging new sources for human infections.

Based on studies undertaken mainly with the US isolates, bovines have been considered the major source of S. Newport infections in humans (Pan et al., 2018). Currently accepted approaches to protect food safety use strategies that control Salmonella in the livestock source and focus on the reduction of Salmonella colonization in livestock. However, the diversified feature of S.Newport, revealed by various underappreciated lineage-specific sources in this study, challenges the traditional knowledge of livestock-orientation disease control strategies, particularly in China. For the first time, this investigation has identified S. Newport STs that are significantly associated with livestock (ST45) and non-livestock sources such as plants and wild birds (ST5), plants and contaminated water-soil (ST118), reptile associated cold-blooded animals (ST46) and seafood associated animals (ST31; Figure 2b). This preferential distribution of STs might show the adaptation of different S. Newport STs and strains to various niches, as a result of variations in genes involved in colonization and/or survival pathways as shown previously (De Masi et al., 2017; Yue & Schifferli, 2014; Yue, Schmieder, Edwards, Rankin, & Schifferli, 2012; Yue et al., 2015).

Multi-drug resistance was strongly associated with strains that originated from livestock and this was particularly linked to livestock-ST45 isolates from the US, China and EU, while only about10.9% of all the non-livestock isolates exhibited some antibiotic resistance. Most human isolates in Clade-III were susceptible to antibiotics, as were non-livestock isolates. In contrast, nearly half of the human isolates in Clade-II ST45 were MDR, as were most of farm-animal isolates of this ST. These results suggest that human infections caused by livestock strains of S. Newport are more likely to carry the MDR phenotype. Thus, livestock sources pose an increased risk of morbidity and mortality for human infections, with frequently worse and costly health outcomes (Campbell et al., 2018).

This study offers a shift from the previous paradigm that focused primarily on livestock source for Salmonella Newport to a broad investigation of Salmonella ecology. The current results also highlight multiple distinct genetic sources, including newly identified Chinese lineages that could serve as emerging sources for human infections.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all the contributors for sharing their Salmonella MLST data, genomic data and strains. This study makes use of data generated by the DECIPHER community. A full list of centres that contributed to the generation of the data is available from http://decipher.sanger.ac.uk and via email from decipher@sanger.ac.uk. Funding for the project was provided by the Wellcome Trust. M.Y. was funded by the National Program on Key Research Project of China (2017YFC1600103; 2018YFD0500501); Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LR19C180001); Zhejiang University “Hundred Talent Program” (2016111) and The Recruitment Program of Global Youth Experts and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2-2050205-18-237). D.M.S. was funded by USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture Grant (2013-67015-21285), NIH/NIAID (AI117135) and funds from the University of Pennsylvania Center for Host-Microbial Interactions.

Funding information

Zhejiang University “Hundred Talent Program”, Grant/Award Number: 2016111; Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, Grant/Award Number: 2-2050205-18-237; Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China, Grant/Award Number: LR19C180001; The Recruitment Program of Global Youth Experts, Grant/Award Number: 13–313; National Program on Key Research Project of China, Grant/Award Number: 2017YFC1600103, 2018YFD0500501; USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture Grant, Grant/Award Number: 2013–67015–21285; NIH/NIAID, Grant/Award Number: AI117135

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

NUCLEOTIDE SEQUENCE ACCESSION NUMBER

The sequences produced by this study are available the Genbank MK191076-MK191831 and Sequence Read Archive under accession numbers SRX1092964, SRX1129499 to SRX1129505.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article.

REFERENCES

- Bell RL, Zheng J, Burrows E, Allard S, Wang CY, Keys CE, … Brown EW (2015). Ecological prevalence, genetic diversity, and epidemiological aspects of Salmonella isolated from tomato agricultural regions of the Virginia Eastern Shore. Frontiers in Microbiology, 6, 415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brands DA, Inman AE, Gerba CP, Mare CJ, Billington SJ, Saif LA, … Joens LA (2005). Prevalence of Salmonella spp. in oysters in the United States. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 71, 893–897. 10.1128/AEM.71.2.893-897.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell D, Tagg K, Bicknese A, McCullough A, Chen J, Karp BE, & Folster JP (2018). Identification and characterization of Salmonella enterica serotype Newport isolates with decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin in the United States. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 62, e00653–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Masi L, Yue M, Hu C, Rakov AV, Rankin SC, & Schifferli DM (2017). Cooperation of adhesin alleles in Salmonella-host tropism. mSphere, 2, e00066–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) and ECDC (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control). (2016). The European Union summary report on trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and food-borne outbreaks in 2015. EFSA Journal, 14:4634, 1–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) and ECDC (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control). (2017). The European Union summary report on trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and food-borne outbreaks in 2016. EFSA Journal, 15:5077, 1–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havelaar AH, Kirk MD, Torgerson PR, Gibb HJ, Hald T, Lake RJ, … Devleesschauwer B (2015). World Health Organization global estimates and regional comparisons of the burden of foodborne disease in 2010. PLoS Medicine, 12, e1001923 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang D, Xu X, Meng J, Yang X, Jin H, Shi W, … Zhang J (2015).Antimicrobial susceptibility, virulence gene profiles and molecular subtypes of Salmonella Newport isolated from humans and other sources. Infection, Genetics and Evolution, 36, 294–299. 10.1016/j.meegid.2015.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Moraes MH, Soto EB, Salas Gonzalez I, Desai P, Chu W, Porwollik S, … Teplitski M (2018). Genome-wide comparative functional analyses reveal adaptations of Salmonella sv. Newport to a plant colonization lifestyle. Frontiers in Microbiology, 9, 877 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan H, Paudyal N, Li X, Fang W, & Yue M (2018). Multiple food-animal-borne route in transmission of antibiotic-resistant Salmonella Newport to humans. Frontiers in Microbiology, 9, 23 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paudyal N, Pan H, Liao X, Zhang X, Li X, Fang W, & Yue M(2018). A Meta-Analysis of major foodborne pathogens in Chinese food commodities between 2006 and 2016. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease, 15, 187–197. 10.1089/fpd.2017.2417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangal V, Harbottle H, Mazzoni CJ, Helmuth R, Guerra B, Didelot X, … Achtman M (2010). Evolution and population structure of Salmonella enterica serovar Newport. Journal of Bacteriology, 192, 6465–6476. 10.1128/JB.00969-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters MS, Simmons L, Anderson TC, DeMent J, Van Zile K,Matthias LP, … Behravesh CB (2016). Outbreaks of Salmonellosis from small turtles. Pediatrics, 137, e20151735 10.1542/peds.2015-1735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You Y, Rankin SC, Aceto HW, Benson CE, Toth JD, & Dou Z(2006). Survival of Salmonella enterica serovar Newport in manure and manure-amended soils. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 72, 5777–5783. 10.1128/AEM.00791-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue M, Han X, De Masi L, Zhu C, Ma X, Zhang J, … Schifferli DM(2015). Allelic variation contributes to bacterial host specificity. Nature Communications, 6, 8754 10.1038/ncomms9754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue M, & Schifferli DM (2014). Allelic variation in Salmonella: An underappreciated driver of adaptation and virulence. Frontiers in Microbiology, 4, 419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue M, Schmieder R, Edwards RA, Rankin SC, & Schifferli DM (2012). Microfluidic PCR combined with pyrosequencing for identification of allelic variants with phenotypic associations among targeted Salmonella genes. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 78, 7480–7482. 10.1128/AEM.01703-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Allard S, Reynolds S, Millner P, Arce G, Blodgett RJ, & Brown EW (2013). Colonization and internalization of Salmonella enterica in tomato plants. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 79, 2494–2502. 10.1128/AEM.03704-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.