Abstract

A 57‐year‐old man with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF‐1) and intrathoracic meningoceles was admitted to hospital after presenting with neck pain and progressive dyspnoea. On admission, a chest computed tomography scan demonstrated right pleural effusion, neck tumour, intrathoracic meningoceles, and rib metastasis. The myelography showed no transportation between the intrathoracic meningoceles and pleural cavity. As a result, these radiological finding indicated the potential for malignant transformation. The appearance of the right pleural effusion was bloody and had no malignant cells. We biopsied the neck tumour, and the tissue showed glass‐like materials but no malignant cells. At 1 month after admission, he developed bladder–rectal disorder, syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone, and paralysis of both legs and later died. An autopsy demonstrated glass‐like material in the neck tumour, which was surrounded by malignant cells. NF‐1 appears to have progressed to a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour in this patient.

Keywords: Giant intrathoracic meningoceles, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour, malignant transformation, neurofibromatosis type 1 (von Recklinghausen disease)

Introduction

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF‐1) was previously referred to as von Recklinghausen disease. NF‐1 is characterized by neurofibroma of the skin, brain, spinal cord, and nervous system; café au lait spots; and bone lesions, among other findings. NF‐1 is an autosomal‐dominant neurocutaneous disorder, affecting 1 in 3000 persons among all ethnic groups. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour (MPNST), which accounts for up 5% of soft‐tissue sarcomas, can arise from benign peripheral nerve sheath tumours, and 32% of MPNSTs are associated with NF‐1 1. Thoracic meningoceles associated with NF‐1 was first described by Phol in 1933. We report a rare autopsy case of NF‐1–associated MPNST carcinomatous pleurisy with giant intrathoracic meningoceles.

Case Report

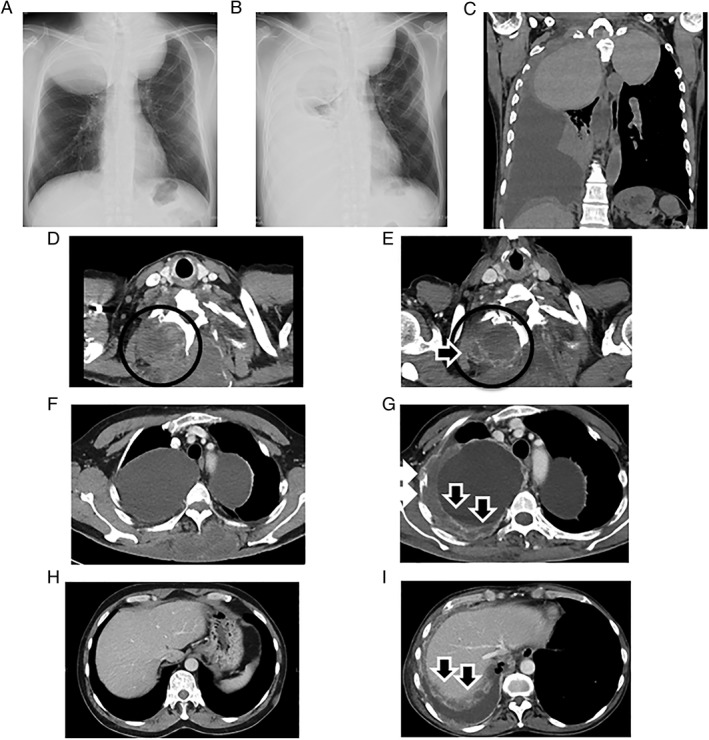

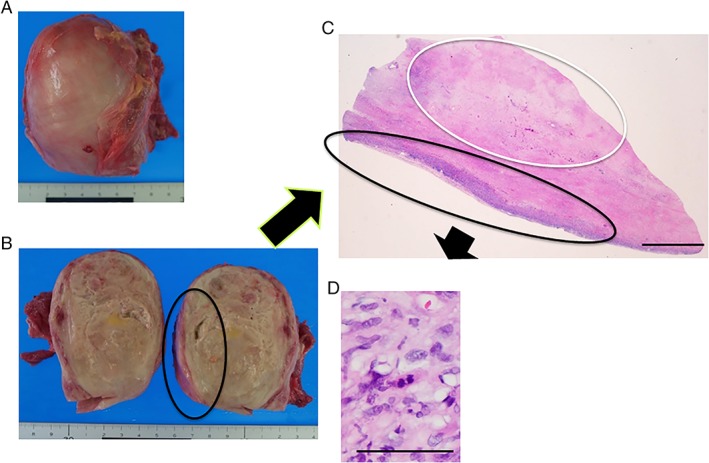

A 57‐year‐old man with NF‐1 diagnosed at 21 years of age was admitted to our hospital for evaluation of neck pain and progressive dyspnoea on exertion. Annual medical check‐ups had showed no change in the lesions until 53 years of age. At 53 years old, he had developed intrathoracic meningoceles, and increased accumulation uptake was observed in the neck (maximum standardized uptake value (SUV max), 3.7–5.3) on positron‐emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT). Physical examination demonstrated findings typical of neurofibromatosis, including multiple (>6) café au lait spots on his back (1–3 cm in diameter) and multiple 0.5–1‐cm cutaneous nodules over the entire trunk. Auscultation showed decreased but coarse breathing sounds over the right lower chest. Chest radiography indicated intrathoracic meningoceles in both lungs, no air in the right lower lung, and slight mediastinal deviation to the left (Fig. 1A,B). A chest CT scan after spinal cord myelography showed no connection between the meningoceles and pleural cavity (Fig. 1C). Chest CT images show both intrathoracic meningoceles, a tumour over the back of neck on the right side (black circles), right pleural thickness with multiple contrast unevenness (black arrows), and rib destructions (white arrows) (Fig. 1D–I). These radiological findings suggested the possibility of malignant transformation. The right pleural effusion included bloody exudate, total protein (TP) 4.2 g/dL, lactate dehydrogenase 468 U/L, and lymphocyte 87%, without malignant cells. Analysis of a biopsy specimen of the neck tumour demonstrated glass‐like materials but no malignant cells. His performance status was poor. He received only palliative care. One month later, he died of complications of vesicorectal disturbance and paralysis of both legs. On autopsy, glass‐like material was found inside the neck tumour, which was surrounded by malignant cells (Fig. 2A–D). We suspected that metastasis to the pleura and diaphragm caused carcinomatous pleurisy based on CT findings. S‐100 nuclear‐ and cytoplasmic‐negative spindle cells were consistent with MPNST on immunohistochemistry. On the basis of clinical and histopathological findings, the tumour was diagnosed as MPNST associated with NF‐1.

Figure 1.

(A) Chest radiograph in December 2012. (B) Chest radiograph in April 2015 shows absence of air in the right lower lung, right pleural effusion, and slight mediastinal deviation to the left. (C) A chest computed tomography scan after spinal cord myelography shows no connection between meningoceles and pleural cavity. Computed tomography images from December 2012 (D, F, H) and April 2015 (E, G, I). Chest computed tomography images show both intrathoracic meningoceles, neck tumour (black circles), right pleural thickness with multiple contrast unevenness (black arrows), and rib destructions (white arrows), indicating clinically malignant metastases.

Figure 2.

Pathological findings at autopsy. (A, B) Macroscopic appearance. (C, D) Histological analysis demonstrated glass‐like material inside the neck tumour (necrosis; white circle), which was surrounded by malignant cells (black circle). Haematoxylin and eosin staining, (C) scale bar = 5 mm, (D) scale bar = 100 μm.

Discussion

In this case, we presume that the meningoceles and the MPNST, although both were manifestations of NF‐1, were not directly related to each other.

In NF‐1, lateral meningoceles are more frequent in the thorax because the paravertebral muscles are relatively weak, and the pressure gradient is greater between the cerebrospinal fluid space and pleural space 2. Initially, we thought that the right meningocele might cause rupture, but spinal cord myelography and chest CT showed no connection between the meningoceles and pleural cavity. A malignant nerve sheath tumour can arise from a peripheral nerve, from a pre‐existing benign nerve sheath tumour (usually neurofibroma), or in a patient with NF‐1. In the absence of definitive findings, diagnosis is based on a constellation of histological, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural features suggesting Schwann cell differentiation 3. Patients with NF‐1, particularly those with plexiform neurofibromas, have the highest rate of malignancy. Rarely, MPSNT arises from schwannoma, ganglioneuroblastoma/ganglioneuroma, or pheochromocytoma. The most common sites for MPNST are the extremities (45%), trunk (34%), and head/neck region (19%) 1. MPNST has a tan‐white, fleshy, cut surface, with areas of haemorrhage and necrosis 3. Thus, it is difficult to diagnose MPNST by needle biopsy or other cytological tests. Metastasis to the pleura and diaphragm could have caused the carcinomatous pleurisy seen in the present patient.

S‐100 nuclear‐ and cytoplasmic‐negative spindle cells were consistent with MPNST on immunohistochemistry in this case. Positive S‐100 expression was reported in 84.8% of MPNST samples. S‐100 is considered a marker of neural crest differentiation and is widely used to differentiate nerve sheath tumours from other soft‐tissue neoplasms. Some MPNST patients have no evidence of S‐100 expression, which was attributed to the differentiation of Schwann cells. Furthermore, the absence of S‐100 expression was reported to be an independent prognostic factor and was associated with a 3.24‐fold risk of recurrence or metastasis and a 5.62‐fold risk of mortality compared with positive S‐100 4.

In our patient, PET‐CT was performed because there were clinicoradiological findings to suggest that malignant transformation had taken place. A systematic review found a significant difference in mean SUV max between benign and malignant lesions (1.93 vs. 7.48, respectively) and noted that 18F‐fluoro‐2‐deoxyglucose PET/CT was a useful, non‐invasive test for discriminating benign and malignant lesions 5.

Here, we report an autopsy case of NF‐1–associated MPNST carcinomatous pleurisy with giant intrathoracic meningoceles. The presence of bilateral giant intrathoracic meningoceles can make the diagnosis of MPNST through chest radiograph alone difficult. Examination by PET/CT as appropriate is important for making an early diagnosis for such rare malignant cases. Needle biopsy and other cytological tests were insufficient for the diagnosis of MPNST during the patient's life. Because of the high risk of malignancy, NF‐1 patients must be followed carefully.

Disclosure Statement

Appropriate written informed consent was obtained for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Acknowledgements

This study was partially supported by a grant from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, awarded to the Study Group on Diffuse Pulmonary Disorders, Scientific Research/Research on Intractable Diseases.

Furukawa, M , Ota, H , Nakamura, Y , Nihonyanagi, Y , Tochigi, N , Homma, S . (2019) Neurofibromatosis type 1‐associated malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour carcinomatous pleurisy: an autopsy case. Respirology Case Reports, 7(7), ;e00463. 10.1002/rcr2.463

Associate Editor: Wai‐Cho Yu

References

- 1. Stucky CCH, Johnson KN, Gray RJ, et al. 2012. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNST): the Mayo Clinic experience. Am. Surg. Oncol. 19:878–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jeong JW, Park KY, Yoon SM, et al. 2010. A large intrathoracic meningocele in a patient with neurofibromatosis‐1. Korean J. Intern. Med. 25:221–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fletcher CDM, Hogendoorn PC, Mertens F, et al. 2013. Pp. 187–189 in WHO classification of tumors of soft tissue and bone. Lyon, France, IARC Press. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yuan Z, Xu L, Zhao Z, et al. 2017. Clinicopathological features and prognosis of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor: a retrospective study of 159 cases from 1999 to 2016. Oncotarget 8:104785–104795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hyung Yoon J, Lee H‐S, In Chun J, et al. 2014. Huge intrathoracic malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor in an adolescent with neurofibromatosis type 1. Case Rep. Pediatr.:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]