Abstract

Background:

Limited data are available regarding causes and outcomes of heart failure as well as organization of care in the developing world.

Methods and Results:

We included consecutive patients diagnosed with heart failure from November 2014 to September 2016 in a university and private hospital of Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic Congo. Baseline data, including echocardiography, were analyzed to determine factors associated with mortality. Cost of hospitalization as well as challenges for care regarding follow-up were determined. A total of 231 patients (56 ± 17 years, 47% men, left ventricular ejection fraction 29 ± 15%, 20% atrial fibrillation) were diagnosed, more during heart failure hospitalizations (69%) than as outpatients (31%). Main risk factors for heart failure included hypertension (59%), chronic kidney disease (51%), alcohol abuse (38%), and obesity (32%). Dilated cardiomyopathy was the most prevalent etiology (48%), with ischemic cardiomyopathy being present in only 4%. In-hospital mortality rate was 19% and associated with an estimated glomerular filtration rate of <60 mL·min−1-1.73 m−2 (P < .01) and atrial fibrillation (P = .02). One hundred six patients (46%) were lost to follow-up, which was mainly related to lack of organization of care, poverty, and poor health literacy. Of the remaining 95 subjects, another 33 (35%) died within 1 year after presentation. The average cost of care for a 10-day hospitalization was higher in a private than in a university hospital (885 vs 409 USD).

Conclusions:

Patients admitted for heart failure in DRC have a high incidence of nonischemic cardiomyopathy and present late during their disease, with limited resources being available accounting for a high mortality rate and very high loss to follow-up.

Keywords: Heart failure, developing world, challenges to care

Recent estimates of the global burden of disease indicate that cardiovascular disease (CVD) is ranked among the leading causes of adult mortality in the developing world, notably in Africa.1–5 The high mortality of complications of CVD, such as heart failure (HF), is in part due to late diagnosis, poor adherence to treatment, limited resources, and poor infrastructure.6 Challenges to care are compounded by poor knowledge of risk factors and comorbidities, lack of medical insurance, and in some instances, cultural or religious beliefs that keep chronically ill patients from accessing care at modern health care facilities.7–9 We designed an observational study that sought to elucidate the causes of HF, risk factors for mortality, and challenges to care in Lubumbashi, a semiurban city of ~2 million people in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a retrospective analysis of information obtained by clinical history and examination from consecutive subjects diagnosed with HF by the first author (D.M.-L.), an experienced heart failure internist, at a university and a private hospital from November 2014 to September 2016 in Lubumbashi, DRC.

Data Collection

The first 2 authors (D.M.-L. and D.N.-N.) collected and analyzed the data and vouch for its completeness. Twelve-lead electrocardiograms were acquired with the use of a Cardiax PC system (Imed, Budapest, Hungary) and coded according to the Minnesota code classification.10 Detailed 2-dimensional echocardiography was performed with the use of a Vivid i ultraportable echo system (GE Medical Systems, Tirat Carmel, Israel) following international guidelines.11,12 The adapted Heart of Soweto criteria were used to assign a single diagnosis based on echocardiography findings.13 On the morning following the first visit, a blood specimen was collected for routine analysis with the use of an automated platform (Human Diagnostics, Wiesbaden, Germany). The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Lubumbashi (UNILU/CEM/044/2014) and patients’ consents were obtained.

Statistical Analysis

Pearson chi-square test and Student t test were used to compare proportions and means, respectively, across study groups of interest. All analyses were performed at a significance level of P < .05 with the use of Stata software version 12.1.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

A total of 231 patients were included of which most were diagnosed during a hospitalization for acute heart failure 69% (n = 159), and only 31% (n = 72) during an outpatient visit.

Patients were relatively young (56 ± 17 years) and had poor left ventricular ejection fraction (29 ± 15%) and elevated right ventricular systolic pressure (40 ± 17 mm Hg) on diagnosis. Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients With Heart Failure in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo

| Length of Stay† | In-Hospital | Follow-up | All Mortality | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOS≥10d | LOS<10d | Alive | Dead | Alive | Dead | Alive | Dead | ||||||

| Variable | All(n = 231) | (n = 71) | (n = 73) | P Value | (n = 129) | (n = 30) | P Value | (n = 62) | (n = 33) | P Value | (n = 62) | (n = 63) | P Value |

| Age, y | 56 ± 17 | 55 ± 18 | 54 ± 18 | .334 | 55 ± 18 | 56 ± 18 | .36 | 55 ± 16 | 55 ± 21 | .47 | 55 ± 16 | 55 ± 19 | .43 |

| Male | 108 (47) | 40 (56) | 23(31) | <.01* | 57 (44) | 15 (50) | .56 | 26 (42) | 15 (45) | .62 | 26 (42) | 30 (48) | .66 |

| No FS | 78 (34) | 24 (34) | 28 (38) | .57 | 41 (32) | 14 (47) | .12 | 19(31) | 12 (36) | .82 | 19(31) | 26 (41) | .33 |

| BMI ≥25 kg/m‡ | 73 (32) | 19 (27) | 24 (33) | .32 | 40(31) | 8(27) | .79 | 23 (37) | 7(21) | .22 | 23 (37) | 15 (24) | .29 |

| Alcohol abuse | 87 (38) | 31 (44) | 22 (30) | .18 | 47 (36) | 13 (43) | .48 | 23 (37) | 11(33) | .83 | 23 (37) | 24 (38) | .99 |

| eGFR <60 mL-min−1 1.73 m−2§ | 117(51) | 38 (54) | 36 (49) | .66 | 59 (46) | 22 (73) | <.01* | 35 (56) | 16 (48) | .33 | 35 (56) | 38 (60) | .10 |

| AF | 47 (20) | 18(25) | 14(19) | .43 | 25 (19) | 12 (40) | .02* | 8(13) | 6(18) | .17 | 8(13) | 18(29) | .09 |

| LBBB | 27 (12) | 14(20) | 3(4) | .01* | 15(12) | 4(13) | .79 | 7(11) | 7(21) | .17 | 7(11) | 11(17) | .21 |

| LVEF, % | 29 ± 15 | 28 ± 17 | 31 ± 17 | .09 | 29 ±16 | 28 ±19 | .39 | 27 ± 13 | 33 ±19 | .06 | 27 ± 13 | 31 ± 19 | .11 |

| RVSP, mm Hg | 40 ± 17 | 38 ± 16 | 43 ± 18 | .05 | 41 ± 18 | 39 ±15 | .27 | 41 ± 19 | 44 ± 19 | .25 | 41 ± 19 | 41 ± 17 | .43 |

| DCM | 110(48) | 36(51) | 31 (42) | .54 | 59 (46) | 14 (47) | .93 | 26 (42) | 15 (45) | .49 | 26 (42) | 29 (46) | .44 |

Values are presented as mean ± SD or n (%). FS, family support; BMI, body mass index; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate (Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula); AF, atrial fibrillation; LBBB, left bundle branch block; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; RVSP, right ventricular systolic pressure; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy.

Difference at a 2-tailed alpha level of .05.

The LOS was analyzed for 144 out of 159 patients hospitalized. The dates of release for 15 patients (9 male and 6 female) were not found in the records.

The BMI could not be determined for 18 patients, for whom there were missing data on weight or height owing to the bedridden status at admission. Five patients with BMI ≥25 kg/m2 had no date of release for determination of LOS.

The eGFR was not determined in 12 patients owing to missing values of creatinine.

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) was the main etiology of HF (48%; n = 110). Cor pulmonale, organic mitral valve disease (regurgitation or stenosis) mostly of rheumatic origin, and peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM) were seen in 12% (n = 28), 11% (n = 26), and 8% (n = 19) of 231 subjects, respectively. Ischemic cardiomyopathy was found in only in 9 patients (4%; Table 2).

Table 2.

Etiologies of Heart Failure in 231 Subjects in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo

| Etiology | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 110 | 47.6 |

| Cor pulmonale | 28 | 12.1 |

| Peripartum cardiomyopathy | 19 | 8.2 |

| Mitral regurgitation | 17 | 7.4 |

| Hypertensive cardiomyopathy | 10 | 4.3 |

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy | 9 | 3.9 |

| Mitral stenosis | 9 | 3.9 |

| Diastolic dysfunction/RCM | 8 | 3.5 |

| Aortic regurgitation | 7 | 3 |

| Pericarditis | 7 | 3 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 4 | 1.7 |

| Left ventricle noncompaction | 2 | 0.9 |

| Ebstein anomaly | 1 | 0.4 |

RCM, restrictive cardiomyopathy.

Patients with DCM were predominantly male (59%; n = 65; P < .01), were older than those without DCM (P < .01), and had a higher prevalence of alcohol abuse (P = .02) and over-weight/obesity (P = .02). The mean left ventricular ejection fraction was significantly lower in patients with DCM than in those with other etiologies (P < .01). Left bundle branch block was more common in patients with DCM (P < .01) and associated with a length of stay ≥ 10 days.

Commonly prescribed medications included furosemide, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker, beta-blocker, digoxin, isosorbide dinitrate, hydralazine, and spironolactone in 91% (n = 211), 66% (n = 105), 7% (n = 12), 60% (n = 96), 13% (n = 20), 8% (n = 13), 1% (n = 2), and 48% (n = 76) of 231 patients, respectively. Use of medication was similar between in- and outpatients.

Outcomes

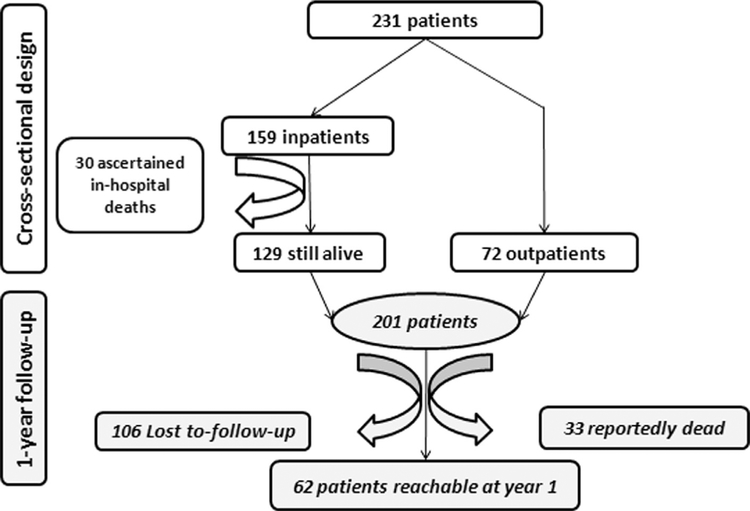

In-hospital mortality rate was 19%. Of the 231 study participants, 106 patients (46%) were lost to follow-up, which was mainly related to lack of organization of care as well as poverty (Fig. 1; Box 1). Of the remaining 95 subjects, 33 (35%) died within 1 year of presentation (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart depicting study enrollment, in- and outpatient distribution, and loss to follow-up due to either death or hospital discharge at patient request. Requests for discharge were often motivated by the patient’s inability to cover medical expenses and/or loss of trust in modern medicine, mostly for subjects who were chronically ill or with advanced disease.

Box 1. Challenges to Management of Heart Failure in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo.

Low economic status

Lack of insurance

No organized care by government

Poor health literacy

Lack of social support

High prevalence of alcohol abuse

Limited access to pharmacologic and nonpharmaco-logic therapies

Limited surgical options for valvular disease andother conditions

Inadequate health care infrastructure and poor communication infrastructure

Poor adherence to therapy and follow-up

Cultural and religious beliefs that reduce acceptance of modern therapies

In-hospital death (19%; n = 30) was significantly associated with an estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL·min−1 1.73 m−2 (P < .01) and atrial fibrillation (P = .02). No significant baseline differences in the aforementioned characteristics were found between those treated as inpatients (n = 159) or outpatients (n = 72) or between those lost to follow-up (n = 106) and those reachable at 1 year (n = 62).

Significant differences regarding cost of HF hospitalization existed between the private and university hospital, which mainly related to the cost of the room. However, the average cost of care for a 10-day hospitalization was well above the monthly income estimated by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) to be only 80 USD in DRC (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cost Estimates (USD) for a 10-Day Hospital Stay for Heart Failure in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo

| ITEMS | University Hospital | Private Clinic |

|---|---|---|

| Physician visits | 94 | 165 |

| Room | 125 | 500 |

| Prescription drugs | in | 10 |

| Electrocardiography* | 20 | 30 |

| Echocardiography* | 60 | 80 |

| Routine biochemical analysis* | 100 | 100 |

| Total | 409 | 885 |

Provided to our study patients free of charge.

Discussion

This study of consecutive HF patients in a private and a university hospital of Lubumbashi, DRC, yielded several key findings. First, nonischemic cardiomyopathy, often related to alcohol abuse, is the most prevalent etiology, with ischemic origin being rare. Second, patients with HF are relatively young and present late during their disease course, with high in-hospital and outpatient mortality. Third, there is a very high rate of loss to follow-up, which is related to the lack of organization of health care, limited resources, and poor health literacy.

The most common etiology of HF in Lubumbashi was dilated cardiomyopathy, followed by cor pulmonale, organic mitral valve disease primarily of rheumatic origin, and PPCM, but not ischemic heart disease. This profile is consistent with epidemiologic patterns previously reported in Africa.14−17 For example, our findings are consistent with that of the THESUS study,15 with similar prevalences of PPCM (8% vs 7.7% in THESUS) and rheumatic heart disease (14% vs 14.3%). Although the main cardiovascular risk factors are similar to those reported in the Western world, the high proportion of cor pulmonale and organic mitral disease in our patients suggests that other preventable diseases, such as acute rheumatic fever or any chronic pulmonary disease, including tuberculosis, may contribute to the burden of CVD in Lubumbashi. Risk factors for DCM and/or PPCM may include black race, alcohol abuse, over-weight, overconsumption of salty food and clay, nutritional deficiencies, psychologic stress, and environmental pollution, which is frequently seen in most parts of the developing world, including Lubumbashi.18−23 The high proportion of DCM among men in our study may be explained by a combination of several factors, such as alcohol abuse and perhaps greater exposure to yet-to-be-explored environmental factors (eg, heavy metals) prevalent in poorly regulated mining areas of Lubumbashi.19

Patients presented late during their disease course and were typically younger than reported in the Western world. Also, the mortality rates were considerably higher than those previously reported in the USA,24 China,25 Europe,26 and even in Africa.15 Aside from later presentation with more advanced disease, other challenges to improve prognosis of these patients in DRC are lack of medical coverage, limited access to surgical treatment of valvular disease, and unavailability of nonpharmacologic treatments, such as cardiac resynchronization and dialysis. The problem of limited resources is compounded by the cultural challenges of traditional or religious beliefs that drive chronically ill subjects away from modern therapies (Box 1).

The DRC ranks 176th among 187 countries in the poverty listing of the UNDP. The monthly income is 80 USD.27 Importantly, while the cost of HF hospitalization for 10 days was well below 1000 USD, there is no insurance covering the cost. It is therefore not a surprise to see that so many patients were lost to follow-up. Aside from financial constraints of the patients, many other reasons account for this.15 These include lack of universal health care coverage, lack of telephone contact or inaccuracy of the telephone number provided on admission, total lack of structured organization of care, poor health literacy among the population, consultation at another facility with the hope of better care, discouragement in the face of chronic illness, moving to another city, and the absence of social workers to track down patients. In addition, the vast majority of the population seeks help from traditional healers for worsening disease as their monetary resources shrink or because of cultural or religious beliefs causing them to distrust modern medicine.28 In a context of poverty, traditions are never far below the surface. Among the Bantu, beliefs such as breaking a taboo, witchcraft, sorcery, “poisoning,” and punishment by the ancestors are easily suggested as causes of illness.29 If patients or their relatives are convinced that hospital-prescribed treatment is futile, few things can persuade them to return for follow-up.7 Instead, they resort to the care of witch doctors, traditional healers, or pastors for deliverance or a miraculous cure.

In the DRC, as in many other African countries, HF is a critical public health concern. Given the preventable causes in some cases, such as acute rheumatic fever and tuberculosis, attention to prompt diagnosis and treatment is crucial to reducing at least some of the burden of CVD. Patient education should be provided to promote healthy lifestyles and increase awareness of readily available treatment options for cardiac disease. Health care benefits, including wider health care coverage, would also allow better access to care.

Poverty is a great barrier to access to care in Lubumbashi. In addition, the poverty of the country also limits the organization of health care and the availability of equipment, personnel, and expertise to treat heart failure. Therefore, mortality and loss to follow-up are very high.

Study Limitations

The main limitations of this study are its cross-sectional design and high rate of loss to follow-up. As a result, data on overall mortality and other outcomes are limited. Data regarding treatments following hospital discharge are also sparse, so the impact of specific therapies on clinical outcomes can not be determined. Finally, our study population was derived from a single city in DRC, and the findings may not be generalizable to other regions of the country.

Conclusion

Management of HF in DRC is challenged by factors related to socioeconomic conditions, environmental and behavioral issues, poor health literacy, and inadequate health care infrastructure. Attention to these factors will be necessary to reduce the burden of HF and improve outcomes for this condition in DRC.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Agnès Pasquet, Tatiana Kuznetsova, Pieter Vandervoort, David Verhaert, Patrick Noyens, Jean-Luc Vachiéry, Rozette Reyskens, Carlo van Nieuwkerke, Kathleen Cuyvers, Kristien Machiels, and Pieter Martens, who provided training opportunities to D.M.-L. The authors are also thankful to Stéphanie Frère and Chief Mulowayi for their contributions.

Funding: Vlaamse Interuniversitaire Raad (ZRDC2014MP081, CD2017TEA439A104) and University of Hasselt; supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant NIEHS/FIC R01ES019841 for capacity building.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Callender T, Woodward M, Roth G, Farzadfar F, Lemarie JC, Gicquel S, et al. Heart failure care in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendez GF, Cowie MR. The epidemiological features of heart failure in developing countries: a review of the literature. Int Cardiol J 2001;80:213–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mensah GA, Roth GA, Sampson UKA, Moran AE, Feigin VL, Forouzanfar MH. et al. Mortality from cardiovascular diseases in sub-Saharan Africa, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis of data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Cardiovasc Afr J 2015;26:S6–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kwan GF, Mayosi BM, Mocumbi AO, Miranda JJ, Ezzati M, Jain Y. et al. Endemic cardiovascular diseases of the poorest billion. Circulation 2016;133:2561–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vedanthan R, Fuster V. Cardiovascular disease in sub-Saharan Africa: a complex picture demanding a multifaceted response. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med 2008;5:516–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sliwa K The heart of Africa: succeeding against the odds. Lancet 2016;388:e28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nnko S, Bukenya D, Kavishe BB, Biraro S, Peck R, Kapiga S. et al. Chronic diseases in north-west Tanzania and southern Uganda. public perceptions of terminologies, aetiologies, symptoms and preferred management. PLoS One 2015;10: e0142194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Namukwaya E, Murray SA, Downing J, Leng M, Grant L. “I think my body has become addicted to those tablets.” Chronic heart failure patients’ understanding of and beliefs about their illness and its treatment: A qualitative longitudinal study from Uganda. PLoS One 2017;12(9):e0182876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albert NM, Levy P, Langlois E, Nutter B, Yang D, Kumar VA. et al. Heart failure beliefs and self-care adherence while being treated in an emergency department. Emerg J Med 2014;46:122–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prineas JR, Crow SR, Zhang Z-M. The Minnesota code manual of electrocardiographic findings: standards and procedures for measurement and classification. London, Dordrecht, Heidelberg: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagueh SF, Smiseth OA, Appleton CP, Byrd BF 3rd, Dokainish H, Edvardsen T. et al. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2016;17:1321–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L. et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2015;16:233–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stewart S, Wilkinson D, Hansen C, Vaghela V, Mvungi R, McMurray J. et al. Predominance of heart failure in the Heart of Soweto study cohort: emerging challenges for urban African communities. Circulation 2008;118:2360–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maharaj B Causes of congestive heart failure in black patients at King Edward VIII Hospital, Durban: Cardiovasc J S Afr; 1991;2:31–2. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Damasceno A, Mayosi BM, Sani M, Ogah OS, Mondo C, Ojji D. et al. The causes, treatment, and outcome of acute heart failure in 1006 Africans from 9 countries. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1386–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Damasceno A, Cotter G, Dzudie A, Sliwa K, Mayosi BM. Heart failure in sub-Saharan Africa: time for action. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:1688–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwan GF, Bukhman AK, Miller AC, Ngoga G, Mucumbitsi J, Bavuma C. et al. A simplified echocardiographic strategy for heart failure diagnosis and management within an integrated noncommunicable disease clinic at district hospital level for sub-Saharan Africa. JACC Heart Fail 2013;1:230–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Narendrula R, Nkongolo KK, Beckett P. Comparative soil metal analyses in Sudbury (Ontario, Canada) and Lubumbashi (Katanga, DR-Congo). Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 2012;88:187–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Banza CL, Nawrot TS, Haufroid V, Decree S, De Putter T, Smolders E. et al. High human exposure to cobalt and other metals in Katanga, a mining area of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Environ Res 2009;109:745–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheyns K, Banza Lubaba Nkulu C, Ngombe LK, Asosa JN, Haufroid V, De Putter T. et al. Pathways of human exposure to cobalt in Katanga, a mining area of the Congo DR. Sci Total Environ 2014;490:313–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mocumbi AOH, Ferreira MB. Neglected cardiovascular diseases in africa. challenges and opportunities. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:680–7. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bora BK, Ramos-Crawford AL, Sikorskii A, Boivin MJ, Lez DM, Ngoyi DM. et al. Concurrent exposure to heavy metals and cognition in school-age children in Congo-Kinshasa: a complex overdue research agenda. Brain Res Bull 2018. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2018.06.013. Published online June 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khan MF, Movahed MR. Obesity cardiomyopathy and systolic function: Obesity is not independently associated with dilated cardiomyopathy. Heart Fail Rev 2013;18:207–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adams KF Jr, Fonarow GC, Emerman CL, LeJemtel TH, Costanzo MR, Abraham WT. et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients hospitalized for heart failure in the United States: rationale, design, and preliminary observations from the first 100,000 cases in the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE). Am Heart J 2005;149:209–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y, Zhang J, Butler J, Yang X, Xie P, Guo D. et al. Contemporary epidemiology, management, and outcomes of patients hospitalized for heart failure in China: results from the China Heart Failure (China-HF) registry. J Card Fail 2017;23:868–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nieminen MS, Brutsaert D, Dickstein K, Drexler H, Follath F, Harjola VP. et al. EuroHeart Failure Survey II (EHFS II): a survey on hospitalized acute heart failure patients: description of population. Eur Heart J 2006;27:2725–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.United Nations Development Programme. Human development report 2016. 2016. http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2016_human_development_report.pdf

- 28.US Agency of International Development. Democratic Republic of the Congo, Health factsheet. 2018. Available at; https://www.usaid.gov/democratic-republic-congo/fact-sheets/usaiddrc-fact-sheet-health. Accessed July 14, 2018.

- 29.Sabuni LP. Dilemma with the local perception of causes of illnesses in central Africa: muted concept but prevalent in everyday life. Qual Health Res 2007;17:1280–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]