Abstract

Background: Carboxylesterases (CES) play a critical role in catalyzing hydrolysis of esters, amides, carbamates and thioesters, as well as bioconverting prodrugs and soft drugs. The unique tissue distribution of CES enzymes provides great opportunities to design prodrugs or soft drugs for tissue targeting. Marked species differences in CES tissue distribution and catalytic activity are particularly challenging in human translation.

Methods: Review and summarization of CES fundamentals and applications in drug discovery and development.

Results: Human CES1 is one of the most highly expressed drug metabolizing enzymes in the liver, while human intestine only expresses CES2. CES enzymes have moderate to high inter-individual variability and exhibit low to no expression in the fetus, but increase substantially during the first few months of life. The CES genes are highly polymorphic and some CES ge-netic variants show significant influence on metabolism and clinical outcome of certain drugs. Monkeys appear to be more predictive of human pharmacokinetics for CES substrates than other species. Low risk of clinical drug-drug interaction is anticipated for CES, although they should not be overlooked, particularly interaction with alcohols. CES enzymes are moderately inducible through a number of transcription factors and can be repressed by inflammatory cy-tokines.

Conclusion: Although significant advances have been made in our understanding of CESs, in vitro - in vivo extrapolation of clearance is still in its infancy and further exploration is needed. In vitro and in vivo tools are continuously being developed to characterize CES substrates and inhibitors

Keywords: Carboxylesterases, CES1, CES2, prodrugs, soft drugs, tissue distribution, species differences, IVIVE, substrates, inhibitors, drug design

1. INTRODUCTION

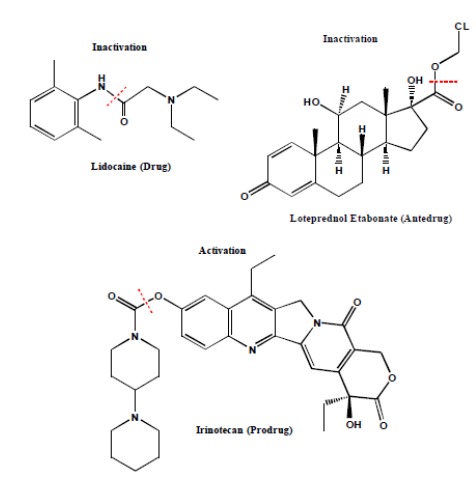

Carboxylesterases (CESs) are an important class of enzymes for biotransformation of drugs, endogenous substrates, and environmental chemicals that contain esters, amides, carbamates, or thioesters (Table 1). They play a central role in the bioactivation of prodrugs and bioinactivation of soft drugs (or antedrugs). It has been estimated that approximately 20% of drugs on the market undergo hydrolysis [1] and about 50% of the prodrug conversion involves hydrolases. CESs metabolize several clinically important classes of drugs such as anticoagulants, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, antihyperlipidemic agents, antivirals, chemotherapeutics, immunosuppressants, and psychoactive drugs [2]. CESs not only inactivate/metabolize drugs and soft drugs to form inactive metabolites (e.g., lidocaine and loteprednol etabonate, Fig. 1), but also activate prodrugs to generate the pharmacologically active moieties (e.g., irinotecan, Fig. 1) [3-5]. CESs belong to the serine hydrolase superfamily of enzymes with the characteristic α/β hydrolase-fold structure containing six α-helices and eight β-strands [2]. There are six CES isoforms, i.e., CES1 to CES6, according to the homology of the amino acid sequence. The two most significant forms of CESs in humans for drug metabolism are CES1 and CES2 [1, 2, 6-8]. Interestingly, CESs could serve as both drugs and drug targets [9]. CES1 is currently being developed by the US military for prophylactic use against chemical weapons of organophosphates (nerve agents such as sarin, soman, tabun and VX gas [9-13]). CES1 has also shown significant promise in the treatment of acute cocaine overdose [9]. Inhibitors of CESs could be used as co-drugs to improve pharmacokinetics, efficacy, and safety profiles of clinically approved drugs where CESs are involved in drug metabolism and clearance [14, 15]. Because of the critical role of CES1 in metabolizing cholesteryl esters [16], inhibitors of CES1 have the potential to treat hypertriglyceridemia, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and atherosclerosis.

Table 1. Examples of drugs and endogenous compounds metabolized by CES [6, 8, 40].

| Classes | Compounds |

|---|---|

| Drugs | Aspirin, capecitabin, cilazapril, clopidogrel, cocaine, dabigatran etexilate, enalapril, heroin, imidapril, irinotecan, meperidine, methylphenidate, olmesartan, orlistat, oseltamivir, quinapril, ramipril, temocapril, trandolapril |

| Endogenous compounds | Acyl-CoA, acylcarnitine, triacylglycerol, cholesterol ester |

| Environmental chemicals | Phthalates, benzoates, pyrethroids, pyrethrins, organophosphorous, pesticides, flame retardants |

Fig. (1).

Inactivation of Drug/Antedrug and Activation of Prodrug by CES [3-5].

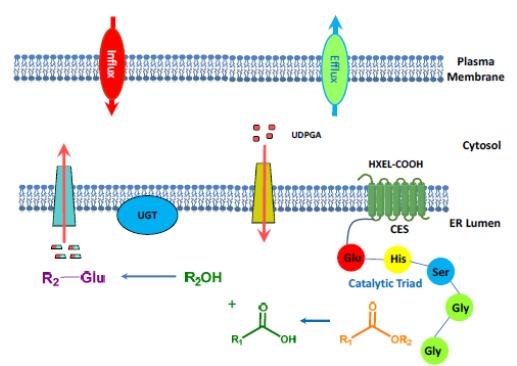

CES1 contains 567 amino acids with a molecular weight (MW) of 62521 Da, while CES2 consists of 559 amino acids and has an MW of 61807 Da [17]. These two enzymes share 48% amino acid sequence identity but exhibit distinct substrate and inhibitor specificity [7, 18]. CESs are mostly membrane-bound and reside on the luminal side of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), but they are also present in the cytosol with lower abundance for reasons not yet fully understood [19, 20]. All CESs contain an N-terminal signaling peptide of 17-22 amino acid residues, which is responsible for the ER localization of these enzymes [7]. The C-terminal sequence (HXEL) binds to the retention sequence of the ER receptor and prevents the secretion of these enzymes from the cells [14, 21, 22]. Several crystal structures of CES1 containing different ligands have been reported [13, 23-26]. CES1 has three binding sites: active site, side door, and Z-side [15]. CES1 active site consists of both a small and rigid pocket (provides selectivity), and a large and flexible domain (provides promiscuity) [1, 13]. The large CES1 active site (~ 1300 Å3) is covered predominately with hydrophobic amino acids, allowing the entry of numerous structurally diverse substrates [14]. CES1 is comprised of monomers, trimers, and hexamers in equilibrium [13, 24]. The distribution of the different forms is substrate-dependent and controlled by the surface binding site (Z-site) [13, 24]. In a substrate-free state, CES1 consists of approximately 10% monomer, 44% trimer, and 46% hexamer [13, 24]. The side door allows hydrolyzed products (acids and alcohols) to rapidly exit the active site, leading to the increasing rate of substrate turnover [27]. X-ray crystal structure of CES2 is currently unknown and CES2 exists as a monomer in the ER [17].

2. PHYSIOLOGICAL FUNCTIONS OF CES ENZYMES

CES1 plays a critical role in lipid metabolism and is responsible for hydrolysis of endogenous esters, such as triacylglycerol, 2-arachidonylglycerol, and cholesteryl esters [6]. Inhibition of CES1 may provide a potential treatment for certain diseases, such as obesity, diabetes, and atherosclerosis [6, 28, 29]. CESs are also important for lipid mobilization, insecticide detoxification, and protein trafficking [1]. The endogenous substrates of CES2 have not yet been identified. CESs are generally considered to be protective and detoxifying enzymes, promoting the elimination of ingested esters and metabolizing a wide variety of drugs and pesticides.

3. CELLULAR LOCATION OF CES ENZYMES

In the human liver, CES1 is located on the luminal side of the ER, where UGTs also reside (Fig. 2) [8, 30, 31]. CESs partner with Phase II enzymes to carry out secondary metabolism of the hydrolytic products (e.g., glucuronidation of acids and alcohols). Due to the presence of the HXEL (His-X-Glu-Leu) sequence at the C-terminal (i.e., HIEL for CES1 and HTEL for CES2), CESs bind to the KDEL (Lys-Asp-Glu-Leu) sequence of the retention protein receptor in the ER and are retained within cells in humans [8]. In hepatocellular carcinoma, however, CES1 can be secreted into the human blood in contrast to the healthy state [32]. In rats and mice, the HXEL sequence is absent in the Ces enzymes, as they have the HTEHK sequence instead, which cannot bind to the KDEL-receptor [8]. As a consequence, Ces enzymes in rodents are secreted into the blood, while human CESs are retained in the cells and are not present in the blood. β-Glucuronidase is known to form a complex with CES1 and be retained in the ER [33]. In the liver, CES1 and CES2 are present in both microsomal and cytosolic fractions [20]. The cytosolic CES1 was found to miss a putative 18 amino acid N-terminal signaling peptide [34]. It has been suggested that processing within the ER is necessary to retain activity [21]. The hepatic dual compartment localization (microsome and cytosol) of CESs is somewhat unique for clearance, although the mechanism controlling the dual location is not yet known [34-36].

Fig. (2).

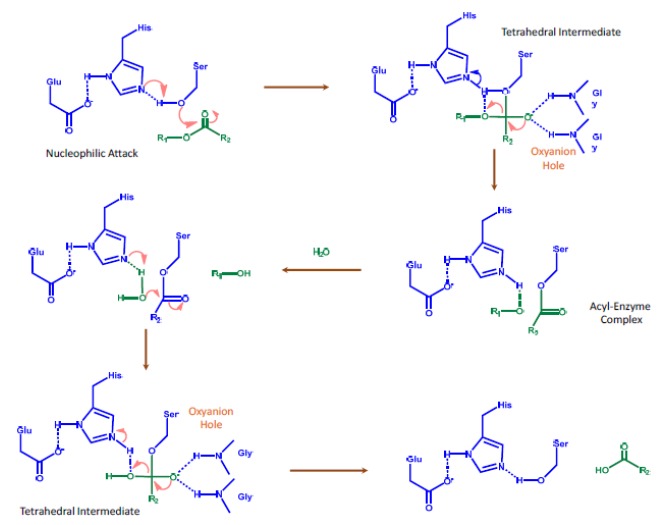

4. MECHANISM OF ACTION

The proposed mechanism of action for CES is shown in Fig. (3). Hydrolysis by CESs is catalyzed by a general acid-base mechanism via a charge-relay complex [29]. The CES1 active site contains a catalytic triad of three amino acids: an acid (glutamate), a base (histidine), and a nucleophile (serine) [8]. The triad (Ser-His-Glu) is inter-dependent and acts in concert to complete the nucleophilic catalysis. In CES-mediated hydrolysis, the oxygen from the alcohol group in the serine attacks the carbonyl carbon of the ester substrate to form a tetrahedral intermediate. In this transitional state, the deprotonated oxygen is stabilized through hydrogen bonding of the two glycine amino acids, resulting in a pocket at the active site called the oxyanion hole. The next step is the formation of the alcohol product and acyl-enzyme complex. This will be followed by nucleophilic attack of the carbonyl carbon of the acetyl group, formation of the tetrahedral intermediate and the oxyanion hole, leaving of the carboxylic acid, and recovery of the CES enzyme. The catalytic triad and the oxyanion hole are believed to stabilize the enzyme-substrate intermediates and, therefore, are essential for CES functions [37]. The catalytic processes by CESs are NADPH independent and require no other cofactors. Certain CESs are also known to catalyze transesterification, which is important for cholesterol homeostasis [1].

Fig. (3).

Proposed Mechanism of Action for CES [8].

5. TISSUE DISTRIBUTION AND SPECIES Difference

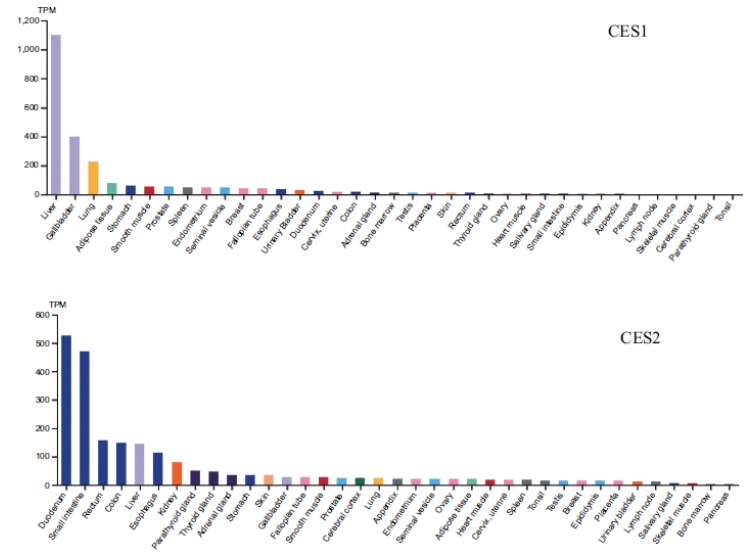

In human, CES1 is predominately expressed in the human liver and is not present in the intestine (Tables 2 and 3, Fig. 4) [20, 30, 38].

Table 2. Protein Expression of CES1 and CES2 in Human Liver and Intestine by Proteomic Approaches [20, 39, 40].

|

Tissue

Preparations |

CES1

(pmol/mg protein) |

CES2

(pmol/mg protein) |

|---|---|---|

| HLM | 402 [20], 1664 [40], 176 [39] | 29.8 [20], 174 [40] |

| HLC | 54.5 [20], 557 [40] | 2.76 [20], ND [40] |

| HIM | ND [20] | ~ 30 [20] |

ND = not detected.

Table 3. Species Difference in Tissue Expression of CES1 and CES2 [30].

| Species | Isozyme | Liver | Small Intestine | Kidney | Lung |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse | CES1 | +++ | - | +++ | +++ |

| CES2 | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | |

| Rat | CES1 | +++ | - | +++ | +++ |

| CES2 | - | +++ | - | - | |

| Beagle Dog | CES1 | +++ | - | NT | +++ |

| CES2 | ++ | - | NT | + | |

| Monkey | CES1 | +++ | ++ | - | NT |

| CES2 | + | +++ | + | NT | |

| Human | CES1 | +++ | - | + | +++ |

| CES2 | + | +++ | +++ | - |

- undetectable, + weak, ++ moderate, +++ strong, NT not tested.

Fig. (4).

Human Tissue Distribution of CES1 and CES2 Based on mRNA Level [38].

Human CES2 is mainly found in the small intestine, but also present in the liver, colon, and kidney. Protein quantification of CES using a proteomic approach shows that CES1 expression in human liver microsomes (HLM) is 176, 402 and 1664 pmol/mg protein, respectively, based on data from three different labs (Table 2) [20, 39, 40]. The high inter-lab variability is consistent with what has been previously reported due to differences in sample preparations and quantification methods [41]. CES1 ranks the tenth most abundant protein expressed in the human liver out of more than 6,000 proteins [29, 42] and is one of most highly expressed drug metabolizing enzymes in the liver. As a comparison, CYP3A4 (the most abundant CYP enzyme in the liver) expression in the liver is 137 pmol/mg protein (SIMCYP database [43]). The protein level of CES2 in HLM is 30-174 pmol/mg protein, which is 10-15 times lower than CES1, suggesting CES1 plays a major role in the liver metabolism of CES substrates. Both CES1 and CES2 are also found in Human Liver Cytosol (HLC), but to a much lesser degree (approximately 3-10 fold higher in HLM). It is not yet understood why CES1 and CES2 are present in HLC as they are generally considered to be membrane bound proteins. In human intestinal microsomes, CES1 is not detected but CES2 is similar in abundance to HLM, ~ 30 pmol/mg protein [20]. This is comparable to CYP3A [4] expression in the intestine (22 pmol/mg protein, SIMCYP database [43]), thus making CES2 one of the most highly expressed drug metabolizing enzymes in the intestine. CES2 hydrolytic activity is relatively constant throughout the small intestine from jejunum to ileum (Fig. 5) [2]. The protein quantification data is used for the development of PBPK models to assess CES mediated clearance and drug-drug interaction potential.

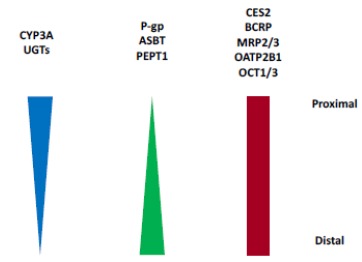

Fig. (5).

Distribution of CES2 and Other Enzymes and Transporters in Human Small Intestine [2, 77, 99-105].

Dog is devoid of Ces activity in the small intestine (Table 4) [44]. Monkey liver Ces expression is similar to human, suggesting a monkey could be a reasonable animal model of CES substrates for human, although monkeys express Ces1 in the intestine while humans do not. Rodents have a much higher number of Ces genes and multiple isoforms compared to humans and monkeys, making them more effective and highly efficient in hydrolyzing their substrates (Table 4) [44, 45]. For example, rats have five isoforms of Ces1 and seven isoforms of Ces2, while mice have eight isoforms of Ces1 and eight isoforms of Ces2 [45]. The redundancy of Ces genes in rodents suggests multiple gene duplication events occurred during evolutionary processes [29].

Table 4. CES Tissue Distribution and Multiple Isoforms of Ces1 and Ces2 in Rodents [45].

| Species | Liver | Small Intestine | Kidney | Lung | Plasma | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | CES1 | CES2 | - | CES2 | - | CES2 | CES1 | - | None |

| Monkey | Ces1 | Ces2 | Ces1 | Ces2 | Ces1 | Ces2 | - | - | None |

| Dog | Ces1 | Ces2 | None | - | Ces1 | Ces2 | Ces1 | Ces2 | None |

| Rat | Ces1c | Ces1d | Ces1e | Ces1f | Ces1e | Ces1f | Ces1d | - | Ces1c |

| - | Ces1e | Ces1f | Ces2a | Ces2c | Ces2g | - | - | - | - |

| - | Ces2a | Ces2c | Ces2h | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| - | Ces2e | Ces2g | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Mouse | Ces1c | Ces1d | Ces1d | Ces1e | Ces1d | Ces1e | Ces1d | - | Ces1c |

| - | Ces1e | Ces1f | Ces1f | Ces1g | Ces1f | Ces1g | - | - | - |

| - | Ces1g | Ces2a | Ces2a | Ces2b | Ces2c | - | - | - | - |

| - | Ces2c | Ces2e | Ces2c | Ces2e | - | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | Ces2g | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Human, monkey, dog, and minipig do not have Ces enzymes in the plasma due to the consensus sequence (HXEL) at the C-terminal that binds to the retention sequence of the receptor in the ER to be retained in cells [46]. Mouse, rat, and rabbit, however, have a high abundance of plasma Ces and the HXEL sequence is absent in these species, resulting in secretion of Ces into the blood [47]. Mouse strains that lack plasma esterase activity are available, i.e., Es1e and Es1e/scid [48, 49]. Plasma esterase-deficient mice are useful to evaluate the impact of plasma esterases on PK. Although humans do not have CESs in plasma, other hydrolases can perform analogous function as Ces enzymes found in other species, such as butyrylcholinesterase (BChE), paraoxonase (PON1), acetylcholinesterase (AchE, negligible amount), and albumin (HSA) [47]. Red blood cells contain additional esterases that are not found in plasma [50].

6. GENETIC POLYMORPHISM AND REGULATION

The CES genes are highly polymorphic and new SNPs are increasingly being identified [1, 6, 51-57]. The minor allele frequencies of CESs can vary greatly among different ethnic groups [56]. Several SNPs are found to be rare in Caucasians, while having much higher frequencies in other populations. Some CES genetic variants have a significant influence on drug metabolism and clinical outcomes [6]. For instance, CES1 genetic polymorphisms have been shown to affect the metabolism of dabigatran etexilate, methylphenidate, oseltamivir, imidapril, and clopidogrel, whereas generic variants of CES2 have been demonstrated to impact the metabolism of aspirin and irinotecan [6]. Although significant progress has been made between CES genetic polymorphism and inter-individual variability of drugs, further research is needed to truly understand its role, including large-scale pharmacogenetic studies to assess drug-gene interactions in the clinic [6, 56].

CES expression is regulated by many factors, including age, hormones, disease state, nutritional status, drugs, and exposure to environmental chemicals1 [58-60]. The expression of CESs is controlled directly or indirectly by activation of transcriptional factors, such as the PXR, CAR, PPARα, HNF4α, GR and Nrf2, although future research is needed to further understand CES regulation [58, 61-65]. Dexamethasone and phenobarbital were found to moderately induce both CES1 and CES2 in human hepatocytes [6]. Inflammatory cytokines (e.g., interleukin [6]), on the other hand, have been shown to repress CES1 and CES2 expression [59]. At the protein level, CES1 and CES2 have a strong correlation, indicating that they are co-regulated [40], and are either induced or suppressed by similar unknown mechanisms. The close chromosomal proximity of the two genes may be conducive to co-regulation [40]. Induction of CESs by endogenous and exogenous compounds has been low to moderate and they appear to be more inducible during developmental stage (e.g., infants) [1, 58].

7. IMPACT OF AGE, GENDER, ETHNICITY, DISEASE STATE AND INDIVIDUAL Variability

CES1 and CES2 expressions are developmentally regulated and have shown an age-dependent maturation based upon strong association among age and mRNA level, protein abundance, and activity [36, 40, 60, 66-68]. Neonates and infants have markedly lower CES1 and CES2 levels compared to older children and adults, but levels increase rapidly after birth. CES1 expression in infants reaches half of the adult level by about 7 months, whilst CES2 expression achieves the same level as adults much earlier, at approximately 3 weeks [40]. Both CES1 and CES2 belong to the most common Class III group of drug-metabolizing enzymes based on developmental trajectories [36, 69]. They exhibit low to no expression in the fetus, but increase substantially during the first months to two years of life [36, 69]. The age differences in CES expression can impact metabolic rate, leading to juvenile sensitivity to adverse effects of certain CES substrates [36, 70]. Both gender and ethnicity show no association with protein abundance of CES1 and CES2 when age is considered [36, 40, 60], although some reports show CES1 to have higher protein expression and hydrolytic efficiency in females than males [2, 71-73]. Liver diseases, such as hepatitis and cirrhosis, have been reported to have decreased CES activities due to suppression by cytokines (e.g., IL-6) produced in these conditions [1, 59].

Moderate to high inter-individual variability of CES1 and CES2 has been reported from 5- to 160-fold for CES1, and 4- to 34-fold for CES2 based on protein abundance, 430-fold based on mRNA level, and 127-fold based on hydrolytic activity [20, 36, 40, 66]. This may be due to genetic polymorphism and physiological and environmental factors. CES inter-individual variation can lead to the differences in PK of CES substrates and the ability to detoxify environmental chemicals in the population [29].

8. SUBSTRATE SPECIFICITY AND DESIGN STRATEGIES FOR TISSUE TARGETING

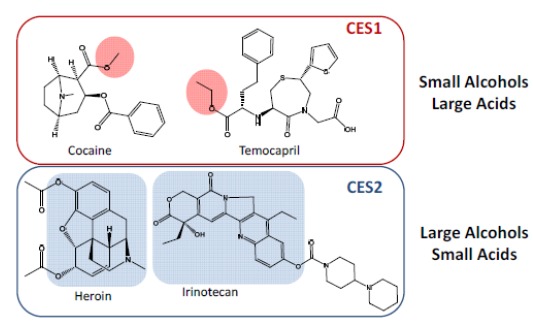

Due to the high catalytic efficiency and specific tissue distribution, CES enzymes are broadly incorporated into the design strategies of prodrugs and soft drugs to increase oral bioavailability, reduce toxicity, or prolong half-life. Although substrates of CES1 and CES2 significantly overlap, they exhibit distinct substrate specificity. CES1 tends to hydrolyze esters with small alcohols and large acids, while CES2 prefers large alcohols and small acids (Fig. 6) [1, 8]. For examples, cocaine (methyl ester) and temocapril (ethyl ester) are CES1 substrates, whereas cocaine (benzoyl ester), heroin, and irinotecan (large alcohol) are CES2 substrates (Fig. 6) [64]. In addition, CES1 prefers smaller and planar substrates (e.g., oseltamivir, clopidogrel), consistent with the structure of the active site, i.e., the physical constraints from the two loops of amino acids [27]. CES2 can hydrolyze very large complex molecules due to the enhanced flexibility of the active site [27]. The selectivity based on the relative size of alcohol/acyl has been demonstrated for a number of CES1 and CES2 substrates with some exceptions [1].

Fig. (6).

Substrate Specificity of CES1 and CES2.

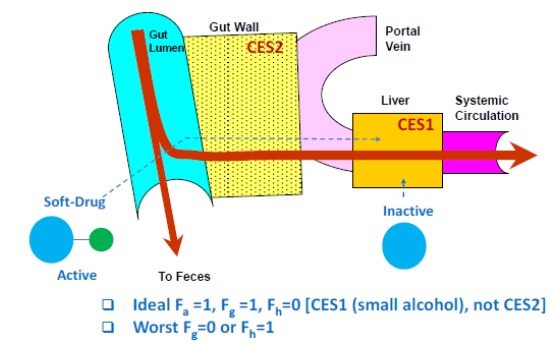

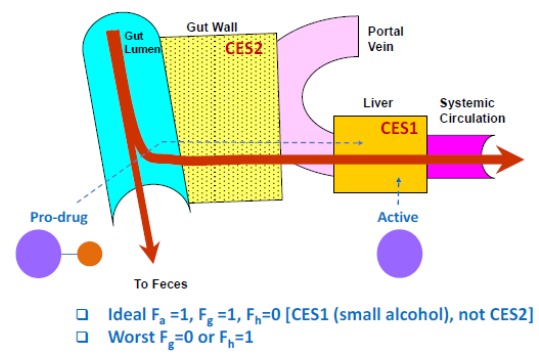

8.1. Gut Targeting with Soft Drugs

Soft drugs are those that act locally to produce pharmacodynamic effects, but are inactivated once they leave the target tissue to minimize systemic exposure and toxicity [4]. If a disease target resides in the enterocytes within the GI tract, soft drug strategy can be applied to target the gut through oral dosing. Soft drugs are absorbed from the small intestine into the enterocytes and exert pharmacological effects. Once they leave the intestine, they will enter into the liver through the portal vein, where they will be inactivated to reduce systemic exposure and side-effects. For gut targeting, CES1 substrates are preferable over CES2 substrates, as CES2 is expressed predominately in the intestine while CES1 is mostly in the liver (Fig. 7). The desirable profile for a gut-targeting soft drug includes high oral absorption (i.e., high Fa, compounds with good solubility and permeability), low first pass gut metabolism (i.e., high Fg), and high extraction by the liver (i.e., low Fh). It would be undesirable for the soft drug to have a high conversion in the intestine (i.e., low Fg) or not be inactivated within the liver (i.e., high Fh). In practice, compounds designed for gut targeting typically have properties somewhere in between these two profiles, with some conversion of the soft drug in the gut and incomplete conversion in the liver. One example of applying the soft drug strategy for gut-targeting is the gut-selective inhibitor of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (Gut-MTP) for treating obesity [74].

Fig. (7).

Antedrug Strategy for Gut Targeting.

8.2. Liver Targeting with Prodrugs

Prodrug strategies can be used for liver targeting to maximize drug exposure in the liver, where the target resides, and minimize systemic exposure and toxicity. For liver targeting, a CES1 prodrug is preferable over a CES2 substrate (Fig. 8). A prodrug intended for liver targeting would ideally have high oral absorption, low intestinal first pass extraction, and high conversion to active moiety in the liver. It would be undesirable for the prodrug to hydrolyze in the gut prematurely or not convert to the action in the liver. In reality, drug discovery compounds typically have properties somewhere in between these two profiles. One example of using a prodrug strategy for liver targeting is the inhibitor of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 synthesis [75].

9. IN VITRO TOOLS TO ASSESS CES

Many standard DMPK assays can be used to evaluate and profile CES substrates, and assay conditions are less stringent than those used for CYPs. For example, organic solvents ≤2%, including DMSO, ethanol, methanol, acetonitrile and acetone, are well tolerated by CESs [76]. Buffer components less than 100 mM, including PBS, HEPES, potassium phosphate, sodium phosphate and Tris [76], have minimal effect on CES activity.

9.1. Absorption -Fa

Standard assays, such as PAMPA, MDCK and Caco-2, can be used to measure permeability. However, MDCK and Caco-2 contain CESs, which can hydrolyze labile substrates. Hydrolase inhibitors, such as BNPP (200 uM) [77], can be added to the system to stabilize compounds for permeability measurement while having minimal effect upon permeation. Even though Caco-2 is derived from human colon carcinoma cells, it actually expresses the liver CES1 rather than the intestinal CES2 [77]. Therefore, using Caco-2 as a surrogate for intestinal stability studies can be misleading, as CES1 is more prevalent in the liver than in the intestine. For solubility measurement, pH buffers, FaSSIF, and FeSSIF can be used to estimate solubility in the GI tract. Various models are available to estimate intestinal absorption using both permeability and solubility values.

9.2. Gut Stability- Fg

For evaluation of gut stability of CES substrates, simulated gastric fluid (SGF, pH1.2 with pepsin), simulated intestinal fluid (SIF, pH 6.8 with pancreatin), and intestinal S9 (no PMSF) can be used. Most commercially available intestinal S9 contains PMSF (CES inhibitor), so it is important to have intestinal S9 custom made without PMSF to avoid inhibiting CES activity. The intestinal stability data can then be used along with permeability values to model Fg [78-84].

9.3. Liver Stability - Fh

Hepatocytes, liver S9, and microsomes are typically used to study liver conversion or stability of CES substrates, so it is important to use liver preparations without PMSF to avoid inhibition of CES.

9.4. Blood and Plasma Stability

Blood, plasma, and serum are the typical matrices utilized when determining the stability or conversion rate of CES substrates. The stability of compounds in blood and plasma is particularly crucial when analyzing CES substrates in PK/TK/PD studies since compounds need to be stable during sample preparation and LC-MS analysis. Compounds can continue to hydrolyze during sample preparation and analysis if they are not stabilized leading to unreliable data. To stabilize CES substrate samples, temperature and pH may be lowered, and inhibitors may be added to minimize enzymatic reactions. The commonly used protocols include collecting blood samples into tubes on wet ice and acidifying blood samples to pH 5 using 2% of 1 M citric acid (cause minimal hemolysis) [85, 86]. Inhibitors may stabilize CES substrates (typical inhibitors are summarized in Table 4 [85, 86]). Ideally, various inhibitors are tested in blood of multiple species to identify optimal inhibitors. Some inhibitors are toxic and may only be suitable for preclinical studies. Fortunately, compounds are usually more stable in human blood than in preclinical species, especially rodents, so that identifying acceptable inhibitors for clinical samples is usually less challenging.

9.5. Stability in Extrahepatic Tissues

Stability of CES substrates in extrahepatic tissues can also be evaluated by using various tissue preparations, e.g., kidney S9 (no PMSF), but it crucial to ensure sure that the tissue preparations do not contain PMSF.

10. IN VIVO ANIMAL MODELS TO ASSESS CES

Animal models are frequently used to evaluate ADME properties of CES substrates. In vivo models have both benefits and limitations in comparison to in vitro systems, as they provide more holistic drug disposition profiles under physiological conditions with the caveat of species differences. In vitro data from both human and preclinical species should be in conjunction with in vivo data to better understand the human translation.

10.1. Rodents

Rodent Ces enzymes have high catalytic capacity and efficiency compared to human CESs, with sequence homologies of about 67-77% to that of humans [30, 87]. There are a large number of Ces isoforms expressed in the rodent liver, intestine and other tissues, i.e., 12 for rat and 16 for mouse [45]. Ces enzymes in rodents are also present in plasma, in contrast to humans. Plasma esterase-deficient mice are available [48] and may be a more appropriate animal model to predict human disposition for CES drugs in certain cases. Rodents tend to have much higher clearance and lower systemic exposure than humans. Due to species differences, rodents are not broadly applicable to predict human PK and metabolic profiles of CES substrates.

10.2. Dogs

Dogs have no intestinal Ces and, therefore, are not good models to evaluate GI stability of CES substrates and first-pass gut metabolism. Similar to humans, dogs lack Ces in the blood. The sequence homologies of dog Ces enzymes are about 80% that of human [30, 87].

10.3. Cynomolgus Monkey

Monkeys have the greatest sequence similarity to humans (86-97%) [30, 77, 87] and, they are lack Ces in the blood as humans. However, unlike humans, monkeys have Ces1 in the intestine and human intestine only has CES2. Based upon limited data, monkey appears to provide a reasonable prediction of human PK for CES substrates using single species scaling.

10.4. PVC Animals

PVC (Portal Vein Cannulated) animals (e.g., rat, dog, monkey) can be used to study absorption and gut first pass metabolism of CES substrates [78, 88-90]. For compounds with good permeability, portal exposure is more of a measurement of gut metabolism. Species differences should be considered in data interpretation. For example, rodents have much greater gut metabolism of Ces substrates; dog does not have Ces in the intestine; monkey intestine has both Ces1 and Ces2; and human intestine only has CES2. The species differences in intestinal Ces expression can lead to differences in Fg.

10.5. BDC Animals

BDC (bile duct cannulated) animals (e.g., rat, dog, monkey) can be used to estimate biliary excretion of CES substrates. However, species differences need to be considered to understand human translation. Rats tend to significantly over-predict human biliary clearance (at least 10-fold) using single species scaling, but dogs and monkeys provide more a reasonable human prediction [91, 92].

11. IVIVE OF CES SUBSTRATES

IVIVE of CES substrates has not been widely investigated. A study using eight CES1 substrates with human data showed that human hepatocytes or liver S9 resulted in a reasonable prediction of human in vivo hepatic intrinsic clearance with half of the compounds within three fold of observed data [93]. Extrahepatic contribution was not considered due to the stability of compounds in those tissues. Under-prediction was observed for compounds with high intrinsic clearance. S9 was found to perform better than hepatocytes in predicting clearance. Future studies with substrates of both CES1 and CES2, and incorporation of extrahepatic contribution, will further increase confidence in human translation.

IVIVE of intestinal availability (FaFg) was evaluated for a set of CES prodrugs using PVC monkey, monkey intestinal S9 stability, and permeability from both PAMPA and MDCK [78]. Strong IVIVE was observed with r2 of 0.71-0.93 using a number of modeling approaches, including a PBPK model and a simplified competitive-rate analytical solution [78]. The study showed that in vitro intestinal S9 stability and permeability assays can be confidently used to predict in vivo FaFg for CES substrates.

12. DRUG-DRUG INTERACTION POTENTIAL OF CES

In vitro DDI (Drug-drug Interaction) of CES has been observed, however, there is no known CES-mediated DDI in the clinic so far, although several interactions with ethanol have been reported2. CES has low potential risk for clinical DDI, but it should not be overlooked. In vitro assays are in place to evaluate victim and perpetrator DDI potentials for CESs.

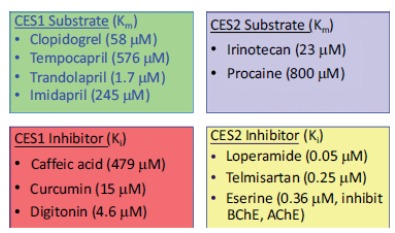

12.1. Evaluation of Victim DDI Potential

Human recombinant enzymes of CES1 and CES2 (hr-CES1 and hr-CES2) are commercially available from various vendors. RAF and ISEF values can be established to estimate the fraction metabolized by CES enzymes using hr-CES1 and hr-CES2. Chemical inhibitors can also be applied with more physiologically relevant systems, such as human hepatocyte suspensions, human liver microsomes, or S9 [94, 95]. Hepatocytes with pan-CYP inhibitor (1 mM ABT with 15 µM tienilic acid) will provide the relative contribution of CYP vs. non-CYP [96]. Selective CES inhibitors may provide individual contributions of CES1 and CES2. Selective CES1 and CES2 inhibitors and substrates are shown in Table 6 [94, 95, 97, 98].

Table 6. Selective Inhibitors and Substrates of CES1 and CES2 [94, 95, 97, 98].

12.2. Evaluation of Perpetrator DDI Potential

Test compounds can be evaluated for CES inhibition potential by using CES substrates (Table 6) in human hepatocytes, human liver microsomes, or hr-CES enzymes. Translation from in vitro CES inhibition to in vivo DDI can be evaluated using static or PBPK modeling, but further validation is needed. A study with hr-CES enzymes showed that many pharmaceutical excipients inhibit CES1 and CES2. However, the in vivo relevance of this finding is unknown as many of the excipients have low cell membrane permeation, which is a prerequisite for in vivo CES inhibition. CESs are moderately inducible (e.g., by dexamethasone and phenobarbital in human hepatocytes [6]) and repressed by inflammatory cytokines through a number of transcription factors (see Section on “Genetic Polymorphism and Regulation”).

CONCLUSION

Significant advances have been made to understand the role of CES enzymes in drug metabolism and disposition, including tissue distribution, species differences, age, disease state, genetic polymorphism, IVIVE, and DDI potential. A number of in vitro and in vivo tools are available to evaluate CES substrates and inhibitors, and new approaches are being developed to further the understanding of this class of important enzymes.

Fig. (8).

Prodrug Strategy for Liver Targeting.

Table 5. Hydrolase Inhibitors to Enhance Blood/Plasma Stability for Bioanalysis [85, 86].

| Enzymes | Inhibitors |

|---|---|

| Carboxylesterases | TTFA, BNPP, Dichlorvos, DFP, PMSF, Paraoxon |

| Acetylcholinesterases | Dichlorvos, Eserine, Paraoxon, Acetylcholine (competitive) |

| Cholinesterases | Eserine |

| Serine Esterases | PMSF, Paraoxon, DFP |

| Phosphodiesterases | BNPP |

| Nonspecific Esterases | NaF |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to thank Karen Atkinson for editing the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- ABT

1-Aminobenzotriazole

- AchE

Acetylcholinesterase

- ADME

Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion

- BChE

Butyrylcholinesterase

- BDC

Bile Duct Cannulated

- BNPP

bis-p-nitrophenyl Phosphate

- Caco-2

Human Epithelial Colorectal Adenocarcinoma Cells

- CAR

Constitutive Androstane Receptor

- CES

Carboxylesterase

- CYP

Cytochrome P450

- DDI

Drug-Drug Interaction

- DMPK

Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics

- DMSO

Dimethyl Sulfoxide

- ER

Endoplasmic Reticulum

- Fa

Fraction Absorbed

- Fg

Fraction Escaping Gut Wall First-pass Extraction

- Fh

Fraction Escaping Liver Extraction

- GR

Glucocorticoid Receptor

- HEPES

4-(2-Hydroxyethyl)-1-Piperazineethanesulfonic Acid

- HLC

Human Liver Cytosol

- HLM

Human Liver Microsomes

- HNF4α

Hepatic Nuclear Factor 4α

- hr-CES

Human Recombinant Carboxylesterase

- HSA

Human Serum Albumin

- ISEF

Intersystem Extrapolation Factor

- IVIVE

In vitro-In vivo extrapolation

- LC-MS

Liquid Chromatography-mass Spectrometry

- MDCK

Madin-Darby Canine Kidney Cells

- MTP

Microsomal Triglyceride Transfer Protein

- mRNA

Messenger Ribonucleic Acid

- NADPH

Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate Hydrogen

- Nrf2

Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-related Factor 2

- PBPK

Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetics

- PAMPA

Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeability Assay

- PBS

Phosphate-buffered Saline

- PD

Pharmacodynamics

- PK

Pharmacokinetics

- PMSF

Phenylmethylsulfonyl Fluoride

- PON1

Paraoxonase

- PPARα

Peroxisome Proliferator-activated Receptor α

- PVC

Portal Vein Cannulated

- PXR

Pregnane X Receptor

- RAF

Relative Activity Factor

- SGF

Simulated Gastric Fluid

- SIF

Simulated Intestine Fluid

- SNP

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism

- Tis

Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane

- TK

Toxicokinetics

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yan B. Carboxylesterases. Encycl. Drug Metab. Interact. 2012;1:423–456. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laizure S.C., Herring V., Hu Z., Witbrodt K., Parker R.B. The role of human carboxylesterases in drug metabolism: Have we overlooked their importance? Pharmacotherapy. 2013;33:210–222. doi: 10.1002/phar.1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hatfield M.J., Potter P.M. Carboxylesterase inhibitors. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2011;21:1159–1171. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2011.586339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di L., Kerns E.H. Drug-Like Properties: Concepts, Structure Design, and Methods. London, UK: Elevier; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ettmayer P., Amidon G.L., Clement B., Testa B. Lessons learned from marketed and investigational prodrugs. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:2393–2404. doi: 10.1021/jm0303812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merali Z., Ross S., Pare G. The pharmacogenetics of carboxylesterases: CES1 and CES2 genetic variants and their clinical effect. Drug Metabol. Drug Interact. 2014;29:143–151. doi: 10.1515/dmdi-2014-0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Satoh T., Hosokawa M. Structure, function and regulation of carboxylesterases. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2006;162:195–211. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Satoh T., Hosokawa M. Carboxylesterases: Structure, function and polymorphism. Biomol. Ther. (Seoul) 2009;17:335–347. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Redinbo M.R., Bencharit S., Potter P.M. Human carboxylesterase 1: From drug metabolism to drug discovery. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2003;31:620–624. doi: 10.1042/bst0310620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sweeney R.E., Maxwell D.M. A theoretical model of the competition between hydrolase and carboxylesterase in protection against organophosphorus poisoning. Math. Biosci. 1999;160:175–190. doi: 10.1016/s0025-5564(99)00028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Broomfield C.A., Kirby S.D. Progress on the road to new nerve agent treatments. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2001;21:S43–S46. doi: 10.1002/jat.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maxwell D.M., Brecht K.M. Carboxylesterase: specificity and spontaneous reactivation of an endogenous scavenger for organophosphorus compounds. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2001;21:S103–S107. doi: 10.1002/jat.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bencharit S., Morton C.L., Xue Y., Potter P.M., Redinbo M.R. Structural basis of heroin and cocaine metabolism by a promiscuous human drug-processing enzyme. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2003;10:349–356. doi: 10.1038/nsb919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang D-D., Zou L-W., Jin Q., Hou J., Ge G-B., Yang L. Recent progress in the discovery of natural inhibitors against human carboxylesterases. Fitoterapia. 2017;117:84–95. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2017.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Redinbo M.R., Potter P.M. Keynote review: Mammalian carboxylesterases: From drug targets to protein therapeutics. Drug Discov. Today. 2005;10:313–325. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03383-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zou L-W., Jin Q., Wang D-D., Qian Q-K., Ge G-B., Yang L., Hao D-C. Carboxylesterase inhibitors: An update. Curr. Med. Chem. 2018;25(14):1627–1649. doi: 10.2174/0929867325666171204155558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. GeneCards®: The Human Gene Database http://www.genecards.org/

- 18.Parker R.B., Hu Z-Y., Meibohm B., Laizure S.C. Effects of alcohol on human carboxylesterase drug metabolism. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2015;54:627–638. doi: 10.1007/s40262-014-0226-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ross M.K., Crow J.A. Human carboxylesterases and their role in xenobiotic and endobiotic metabolism. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2007;21:187–196. doi: 10.1002/jbt.20178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sato Y., Miyashita A., Iwatsubo T., Usui T. Simultaneous absolute protein quantification of carboxylesterases 1 and 2 in human liver tissue fractions using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2012;40:1389–1396. doi: 10.1124/dmd.112.045054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Potter P.M., Wolverton J.S., Morton C.L., Wierdl M., Danks M.K. Cellular localization domains of a rabbit and a human carboxylesterase: Influence on irinotecan (CPT-11) metabolism by the rabbit enzyme. Cancer Res. 1998;58:3627–3632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robbi M., Beaufay H. The COOH terminus of several liver carboxylesterases targets these enzymes to the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:20498–20503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bencharit S., Morton C.L., Howard-Williams E.L., Danks M.K., Potter P.M., Redinbo M.R. Structural insights into CPT-11 activation by mammalian carboxylesterases. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2002;9:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nsb790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bencharit S., Morton C.L., Xue Y., Potter P.M., Redinbo M.R. Structural basis of heroin and cocaine metabolism by a promiscuous human drug-processing enzyme. [Erratum to document cited in CA139:65362]. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2003;10:577. doi: 10.1038/nsb919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bencharit S., Morton C.L., Hyatt J.L., Kuhn P., Danks M.K., Potter P.M., Redinbo M.R. Crystal structure of human carboxylesterase 1 complexed with the alzheimer’s drug tacrine: From binding promiscuity to selective inhibition. Chem. Biol. 2003;10:341–349. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(03)00071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fleming C.D., Edwards C.C., Kirby S.D., Maxwell D.M., Potter P.M., Cerasoli D.M., Redinbo M.R. Crystal structures of human carboxylesterase 1 in covalent complexes with the chemical warfare Agents Soman and Tabun. Biochemistry. 2007;46:5063–5071. doi: 10.1021/bi700246n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Argikar U.A., Potter P.M., Hutzler J.M., Marathe P.H. Challenges and opportunities with non-CYP enzymes aldehyde oxidase, carboxylesterase, and UDP-glucuronosyltransferase: Focus on reaction phenotyping and prediction of human clearance. AAPS J. 2016;18:1391–1405. doi: 10.1208/s12248-016-9962-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu J., Xu Y., Xu Y., Yin L., Zhang Y., Xu J. Global inactivation of carboxylesterase 1 (Ces1/Ces1g) protects against atherosclerosis in Ldlr (-/-) mice. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:17845. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18232-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ross M.K., Streit T.M., Herring K.L. Carboxylesterases: Dual roles in lipid and pesticide metabolism. J. Pestic. Sci. 2010;35:257–264. doi: 10.1584/jpestics.R10-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hosokawa M. Structure and catalytic properties of carboxylesterase isozymes involved in metabolic activation of prodrugs. Molecules. 2008;13:412–431. doi: 10.3390/molecules13020412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Di L. The role of drug metabolizing enzymes in clearance. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2014;10:379–393. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2014.876006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Na K., Lee E-Y., Lee H-J., Kim K-Y., Lee H., Jeong S-K., Jeong A-S., Cho S.Y., Kim S.A., Song S.Y., Kim K.S., Cho S.W., Kim H., Paik Y-K. Human plasma carboxylesterase 1, a novel serologic biomarker candidate for hepatocellular carcinoma. Proteomics. 2009;9:3989–3999. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhen L., Rusiniak M.E., Swank R.T. The β-glucuronidase propeptide contains a serpin-related octamer necessary for complex formation with egasyn esterase and for retention within the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:11912–11920. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.20.11912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tabata T., Katoh M., Tokudome S., Nakajima M., Yokoi T. Identification of the cytosolic carboxylesterase catalyzing the 5′-deoxy-5-fluorocytidine formation from capecitabine in human liver. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2004;32:1103–1110. doi: 10.1124/dmd.104.000554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu G., Zhang W., Ma M.K., McLeod H.L. Human carboxylesterase 2 is commonly expressed in tumor tissue and is correlated with activation of irinotecan. Clin. Cancer Res. 2002;8:2605–2611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hines R.N., Simpson P.M., McCarver D.G. Age-dependent human hepatic carboxylesterase 1 (CES1) and carboxylesterase 2 (CES2) postnatal ontogeny. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2016;44:959–966. doi: 10.1124/dmd.115.068957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fleming C.D., Bencharit S., Edwards C.C., Hyatt J.L., Tsurkan L., Bai F., Fraga C., Morton C.L., Howard-Williams E.L., Potter P.M., Redinbo M.R. Structural insights into drug processing by human carboxylesterase 1: Tamoxifen, mevastatin, and inhibition by benzil. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;352:165–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Human Protein Atlas; https://www.proteinatlas.org/ (Accessed April 3, 2019).

- 39.Wang X., Liang Y., Liu L., Shi J., Zhu H-J. Targeted absolute quantitative proteomics with SILAC internal standards and unlabeled full-length protein calibrators (TAQSI). Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2016;30:553–561. doi: 10.1002/rcm.7482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boberg M., Vrana M., Mehrotra A., Pearce R.E., Gaedigk A., Bhatt D.K., Leeder J.S., Prasad B. Age-dependent absolute abundance of hepatic carboxylesterases (CES1 and CES2) by LC-MS/MS proteomics: application to PBPK modeling of oseltamivir in vivo pharmacokinetics in infants. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2017;45:216–223. doi: 10.1124/dmd.116.072652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wegler C., Gaugaz F.Z., Andersson T.B., Wisniewski J.R., Busch D., Groeer C., Oswald S., Noren A., Weiss F., Hammer H.S., Joos T.O., Poetz O., Achour B., Rostami-Hodjegan A., Van De Steeg E., Wortelboer H.M., Artursson P. Variability in mass spectrometry-based quantification of clinically relevant drug transporters and drug metabolizing enzymes. Mol. Pharm. 2017;14:3142–3151. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.7b00364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun A., Jiang Y., Wang X., Liu Q., Zhong F., He Q., Guan W., Li H., Sun Y., Shi L., Yu H., Yang D., Xu Y., Song Y., Tong W., Li D., Lin C., Hao Y., Geng C., Yun D., Zhang X., Yuan X., Chen P., Zhu Y., Li Y., Liang S., Zhao X., Liu S., He F. Liverbase: A comprehensive view of human liver biology. J. Proteome Res. 2010;9:50–58. doi: 10.1021/pr900191p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. SIMCYP, Certara, Sheffield, United Kingdom; https://www. certara.com/ (Accessed April 3, 2019).

- 44.Williams E.T., Bacon J.A., Bender D.M., Lowinger J.J., Guo W-K., Ehsani M.E., Wang X., Wang H., Qian Y-W., Ruterbories K.J., Wrighton S.A., Perkins E.J. Characterization of the expression and activity of carboxylesterases 1 and 2 from the beagle dog, cynomolgus monkey, and human. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2011;39:2305–2313. doi: 10.1124/dmd.111.041335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oda S., Fukami T., Yokoi T., Nakajima M. A comprehensive review of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase and esterases for drug development. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2015;30:30–51. doi: 10.1016/j.dmpk.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bahar F.G., Ohura K., Ogihara T., Imai T. Species difference of esterase expression and hydrolase activity in plasma. J. Pharm. Sci. 2012;101:3979–3988. doi: 10.1002/jps.23258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li B., Sedlacek M., Manoharan I., Boopathy R., Duysen E.G., Masson P., Lockridge O. Butyrylcholinesterase, paraoxonase, and albumin esterase, but not carboxylesterase, are present in human plasma. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2005;70:1673–1684. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morton C.L., Iacono L., Hyatt J.L., Taylor K.R., Cheshire P.J., Houghton P.J., Danks M.K., Stewart C.F., Potter P.M. Activation and antitumor activity of CPT-11 in plasma esterase-deficient mice. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2005;56:629–636. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-1027-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Soares E.R. Identification of a new allele of Es-I segregating in an inbred strain of mice. Biochem. Genet. 1979;17:577–583. doi: 10.1007/BF00502119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williams F.M. Clinical significance of esterases in man. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1985;10:392–403. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198510050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhu H-J., Patrick K.S., Yuan H-J., Wang J-S., Donovan J.L., DeVane C.L., Malcolm R., Johnson J.A., Youngblood G.L., Sweet D.H., Langaee T.Y., Markowitz J.S. Two CES1 gene mutations lead to dysfunctional carboxylesterase 1 activity in man: Clinical significance and molecular basis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008;82:1241–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ribelles N., Lopez-Siles J., Sanchez A., Gonzalez E., Sanchez M.J., Carbantes F., Sanchez-Rovira P., Marquez A., Duenas R., Sevilla I., Alba E. A carboxylesterase 2 gene polymorphism as predictor of capecitabine on response and time to progression. Curr. Drug Metab. 2008;9:336–343. doi: 10.2174/138920008784220646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kubo T., Kim S-R., Sai K., Saito Y., Nakajima T., Matsumoto K., Saito H., Shirao K., Yamamoto N., Minami H., Ohtsu A., Yoshida T., Saijo N., Ohno Y., Ozawa S., Sawada J-I. Functional characterization of three naturally occurring single nucleotide polymorphisms in the CES2 gene encoding carboxylesterase 2 (HCE-2). Drug Metab. Dispos. 2005;33:1482–1487. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.005587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Geshi E., Kimura T., Yoshimura M., Suzuki H., Koba S., Sakai T., Saito T., Koga A., Muramatsu M., Katagiri T. A single nucleotide polymorphism in the carboxylesterase gene is associated with the responsiveness to imidapril medication and the promoter activity. Hypertens. Res. 2005;28:719–725. doi: 10.1291/hypres.28.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sanghani S.P., Sanghani P.C., Schiel M.A., Bosron W.F. Human carboxylesterases: an update on CES1, CES2 and CES3. Protein Pept. Lett. 2009;16:1207–1214. doi: 10.2174/092986609789071324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang X., Rida N., Shi J., Wu Audrey H., Bleske Barry E., Zhu H.J. A comprehensive functional assessment of carboxylesterase 1 nonsynonymous polymorphisms. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2017;45:1149–1155. doi: 10.1124/dmd.117.077669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Charasson V., Bellott R., Meynard D., Longy M., Gorry P., Robert J. Pharmacogenetics of human carboxylesterase 2, an enzyme involved in the activation of irinotecan into SN-38. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004;76:528–535. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhu W., Song L., Zhang H., Matoney L., Lecluyse E., Yan B. Dexamethasone differentially regulates expression of carboxylesterase genes in humans and rats. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2000;28:186–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang J., Shi D., Yang D., Song X., Yan B. Interleukin-6 alters the cellular responsiveness to clopidogrel, irinotecan, and oseltamivir by suppressing the expression of carboxylesterases HCE1 and HCE2. Mol. Pharmacol. 2007;72:686–694. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.036889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhu H-J., Appel D.I., Jiang Y., Markowitz J.S. Age- and sex-related expression and activity of carboxylesterase 1 and 2 in mouse and human liver. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2009;37:1819–1825. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.028209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yang J., Yan B. Photochemotherapeutic agent 8-methoxypsoralen induces cytochrome P450 3A4 and carboxylesterase HCE2: Evidence on an involvement of the pregnane X receptor. Toxicol. Sci. 2007;95:13–22. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Staudinger J.L., Xu C., Cui Y.J., Klaassen C.D. Nuclear receptor-mediated regulation of carboxylesterase expression and activity. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2010;6:261–271. doi: 10.1517/17425250903483215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Furihata T., Hosokawa M., Masuda M., Satoh T., Chiba K. Hepatocyte nuclear factor-4α plays pivotal roles in the regulation of mouse carboxylesterase 2 gene transcription in mouse liver. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2006;447:107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cui J.Y., Li C.Y. McQueen, C.A. Comprehensive Toxicology. 3rd ed. Amsterdam: Elservier; 2018. Regulation of Xenobiotic Metabolism in the Liver. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maruichi T., Fukami T., Nakajima M., Yokoi T. Transcriptional regulation of human carboxylesterase 1A1 by nuclear factor-erythroid 2 related factor 2 (Nrf2). Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010;79:288–295. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yang D., Pearce R.E., Wang X., Gaedigk R., Wan Y-J.Y., Yan B. Human carboxylesterases HCE1 and HCE2: Ontogenic expression, inter-individual variability and differential hydrolysis of oseltamivir, aspirin, deltamethrin and permethrin. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2009;77:238–247. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shi D., Yang D., Prinssen E.P., Davies B.E., Yan B. Surge in expression of carboxylesterase 1 during the post-neonatal stage enables a rapid gain of the capacity to activate the anti-influenza prodrug oseltamivir. J. Infect. Dis. 2011;203:937–942. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen Y-T., Trzoss L., Yang D., Yan B. Ontogenic expression of human carboxylesterase-2 and cytochrome P450 3A4 in liver and duodenum: Postnatal surge and organ-dependent regulation. Toxicology. 2015;330:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hines R.N. Age-dependent expression of human drug-metabolizing enzymes. In: Lyubimov A.V., Rodrigues A.D., Sinz M.A., editors. Encyclopedia of Drug Metabolism and Interactions. Vol. 4. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2012. pp. 451–483. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dalvi Prashant S., Singh A., Trivedi Hiren R., Mistry Suresh D., Vyas Bhadresh R. Adverse drug reaction profile of oseltamivir in children. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2011;2:100–103. doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.81901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vree T.B., Dammers E., Ulc I., Horkovics-Kovats S., Ryska M., Merkx I. Differences between lovastatin and simvastatin hydrolysis in healthy male and female volunteers: Gut hydrolysis of lovastatin is twice that of simvastatin. ScientificWorldJournal. 2003;3:1332–1343. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2003.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Patrick K.S., Straughn A.B., Minhinnett R.R., Yeatts S.D., Herrin A.E., DeVane C.L., Malcolm R., Janis G.C., Markowitz J.S. Influence of ethanol and gender on methylphenidate pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007;81:346–353. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shi J., Wang X., Eyler R.F., Liang Y., Liu L., Mueller B.A., Zhu H-J. Association of Oseltamivir Activation with Gender and Carboxylesterase 1 Genetic Polymorphisms. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2016;119:555–561. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.12625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Robinson R.P., Bartlett J.A., Bertinato P., Bessire A.J., Cosgrove J., Foley P.M., Manion T.B., Minich M.L., Ramos B., Reese M.R., Schmahai T.J., Swick A.G., Tess D.A., Vaz A., Wolford A. Discovery of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTP) inhibitors with potential for decreased active metabolite load compared to dirlotapide. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;21:4150–4154. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.05.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McClure K.F., Piotrowski D.W., Petersen D., Wei L., Xiao J., Londregan A.T., Kamlet A.S., Dechert-Schmitt A-M., Raymer B., Ruggeri R.B., Canterbury D., Limberakis C., Liras S., DaSilva-Jardine P., Dullea R.G., Loria P.M., Reidich B., Salatto C.T., Eng H., Kimoto E., Atkinson K., King-Ahmad A., Scott D., Beaumont K., Chabot J.R., Bolt M.W., Maresca K., Dahl K., Arakawa R., Takano A., Halldin C. Liver-targeted small-molecule inhibitors of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 Synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2017;56:16218–16222. doi: 10.1002/anie.201708744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Williams E.T., Ehsani M.E., Wang X., Wang H., Qian Y-W., Wrighton S.A., Perkins E.J. Effect of buffer components and carrier solvents on in vitro activity of recombinant human carboxylesterases. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods. 2008;57:138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Imai T., Ohura K. The role of intestinal carboxylesterase in the oral absorption of prodrugs. Curr. Drug Metab. 2010;11:793–805. doi: 10.2174/138920010794328904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Trapa P.E., Beaumont K., Atkinson K., Eng H., King-Ahmad A., Scott D.O., Maurer T.S., Di L. In vitro -In vivo extrapolation of intestinal availability for carboxylesterase substrates using portal vein-cannulated monkey. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017;106:898–905. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dokoumetzidis A., Kalantzi L., Fotaki N. Predictive models for oral drug absorption: From in silico methods to integrated dynamical models. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2007;3:491–505. doi: 10.1517/17425225.3.4.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yang J., Jamei M., Yeo K.R., Tucker G.T., Rostami-Hodjegan A. Prediction of intestinal first-pass drug metabolism. Curr. Drug Metab. 2007;8:676–684. doi: 10.2174/138920007782109733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Benet L.Z., Izumi T., Zhang Y., Silverman J.A., Wacher V.J. Intestinal MDR transport proteins and P-450 enzymes as barriers to oral drug delivery. J. Control. Release. 1999;62:25–31. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Karlsson F.H., Bouchene S., Hilgendorf C., Dolgos H., Peters S.A. Utility of in vitro systems and preclinical data for the prediction of human intestinal first-pass metabolism during drug discovery and preclinical development. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2013;41:2033–2046. doi: 10.1124/dmd.113.051664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nishimuta H., Sato K., Yabuki M., Komuro S. Prediction of the intestinal first-pass metabolism of CYP3A and UGT substrates in humans from in vitro data. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2011;26:592–601. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.DMPK-11-RG-034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gertz M., Harrison A., Houston J.B., Galetin A. Prediction of human intestinal first-pass metabolism of 25 CYP3A substrates from in vitro clearance and permeability data. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2010;38:1147–1158. doi: 10.1124/dmd.110.032649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fung E.N., Zheng N., Arnold M.E., Zeng J. Effective screening approach to select esterase inhibitors used for stabilizing ester-containing prodrugs analyzed by LC-MS/MS. Bioanalysis. 2010;2:733–743. doi: 10.4155/bio.10.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zheng N., Fung E.N., Buzescu A., Arnold M.E., Zeng J. Esterase inhibitors as ester-containing drug stabilizers and their hydrolytic products: Potential contributors to the matrix effects on bioanalysis by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2012;26:1291–1304. doi: 10.1002/rcm.6230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Taketani M., Shii M., Ohura K., Ninomiya S., Imai T. Carboxylesterase in the liver and small intestine of experimental animals and human. Life Sci. 2007;81:924–932. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Holenarsipur V.K., Gaud N., Sinha J., Sivaprasad S., Bhutani P., Subramanian M., Singh S.P., Arla R., Paruchury S., Sharma T., Marathe P., Mandlekar S. Absorption and cleavage of enalapril, a carboxyl ester prodrug, in the rat intestine: In vitro, in situ intestinal perfusion and portal vein cannulation models. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 2015;36(6):385–397. doi: 10.1002/bdd.1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Babusis D., Phan T.K., Lee W.A., Watkins W.J., Ray A.S. Mechanism for effective lymphoid cell and tissue loading following oral administration of nucleotide prodrug GS-7340. Mol. Pharm. 2013;10:459–466. doi: 10.1021/mp3002045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pan-Zhou X-R., Mayes B.A., Rashidzadeh H., Gasparac R., Smith S., Bhadresa S., Gupta K., Cohen M.L., Bu C., Good S.S., Moussa A., Rush R. Pharmacokinetics of IDX184, a liver-targeted oral prodrug of 2′-methylguanosine-5′-monophosphate, in the monkey and formulation optimization for human exposure. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2016;41(5):567–574. doi: 10.1007/s13318-015-0267-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Grime K., Paine S.W. Species differences in biliary clearance and possible relevance of hepatic uptake and efflux transporters involvement. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2013;41:372–378. doi: 10.1124/dmd.112.049312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kimoto E., Bi Y-A., Kosa R.E., Tremaine L.M., Varma M.V.S. Hepatobiliary clearance prediction: species scaling from monkey, dog, and rat, and in vitro -in vivo extrapolation of sandwich-cultured human hepatocytes using 17 drugs. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017;106:2795–2804. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2017.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nishimuta H., Houston J.B., Galetin A. Hepatic, intestinal, renal, and plasma hydrolysis of prodrugs in human, cynomolgus monkey, dog, and rat: Implications for in vitro -in vivo extrapolation of clearance of prodrugs. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2014;42:1522–1531. doi: 10.1124/dmd.114.057372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Umehara K-I., Zollinger M., Kigondu E., Witschi M., Juif C., Huth F., Schiller H., Chibale K., Camenisch G. Esterase phenotyping in human liver in vitro: Specificity of carboxylesterase inhibitors. Xenobiotica. 2016;46:862–867. doi: 10.3109/00498254.2015.1133867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bohnert T., Patel A., Templeton I., Chen Y., Lu C., Lai G., Leung L., Tse S., Einolf H.J., Wang Y-H., Sinz M., Stearns R., Walsky R., Geng W., Sudsakorn S., Moore D., He L., Wahlstrom J., Keirns J., Narayanan R., Lang D., Yang X. Evaluation of a new molecular entity as a victim of metabolic drug-drug interactions-an industry perspective. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2016;44:1399–1423. doi: 10.1124/dmd.115.069096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yang X., Atkinson K., Di L. Novel cytochrome p450 reaction phenotyping for low-clearance compounds using the hepatocyte relay method. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2016;44:460–465. doi: 10.1124/dmd.115.067876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Fukami T., Kariya M., Kurokawa T., Iida A., Nakajima M. Comparison of substrate specificity among human arylacetamide deacetylase and carboxylesterases. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015;78:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shimizu M., Fukami T., Nakajima M., Yokoi T. Screening of specific inhibitors for human carboxylesterases or arylacetamide deacetylase. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2014;42:1103–1109. doi: 10.1124/dmd.114.056994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bruckmueller H., Martin P., Kaehler M., Haenisch S., Ostrowski M., Drozdzik M., Siegmund W., Cascorbi I., Oswald S. Clinically relevant multidrug transporters are regulated by microRNAs along the human intestine. Mol. Pharm. 2017;14:2245–2253. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.7b00076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mueller J., Keiser M., Drozdzik M., Oswald S. Expression, regulation and function of intestinal drug transporters: An update. Biol. Chem. 2017;398:175–192. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2016-0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Berggren S., Gall C., Wollnitz N., Ekelund M., Karlbom U., Hoogstraate J., Schrenk D., Lennernaes H. Gene and protein expression of P-Glycoprotein, MRP1, MRP2, and CYP3A4 in the small and large human intestine. Mol. Pharm. 2007;4:252–257. doi: 10.1021/mp0600687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Peters S.A., Jones C.R., Ungell A-L., Hatley O.J.D. Predicting drug extraction in the human gut wall: Assessing contributions from drug metabolizing enzymes and transporter proteins using preclinical models. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2016;55:673–696. doi: 10.1007/s40262-015-0351-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Strassburg C.P., Kneip S., Topp J., Obermayer-Straub P., Barut A., Tukey R.H., Manns M.P. Polymorphic gene regulation and interindividual variation of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase activity in human small intestine. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:36164–36171. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002180200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhang Q-Y., Dunbar D., Ostrowska A., Zeisloft S., Yang J., Kaminsky L.S. Characterization of human small intestinal cytochromes P-450. Drug Metab. Dispos. 1999;27:804–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Harwood M.D., Neuhoff S., Carlson G.L., Warhurst G., Rostami-Hodjegan A. Absolute abundance and function of intestinal drug transporters: A prerequisite for fully mechanistic in vitro -in vivo extrapolation of oral drug absorption. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 2013;34:2–28. doi: 10.1002/bdd.1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]