Abstract

Introduction:

Prevalence of hypertension (HTN) is increasing in the developing countries like Iran. Various stud-ies have reported different rates of HTN in Iran. The purpose of this study was to estimate an overall prevalence of HTN in Iran.

Methodology:

Using the English and Persian key derived from Mesh, the databases including MagIran, Iran Medex, SID, Web of Sciences, PubMed, Science Direct and Google Scholar as a searching engine were reviewed: from 2004 to 2018. The overall prevalence of MA was estimated using Random effect model. The I2 test was used to assess the heterogeneity of the studies. Additionally, the quality of studies was evaluated using a standard tool. Publication bias was conducted with the Egger test. Meta-regression and analysis of subgroups were analyzed based on variables such as age, marital status, region and tools. Data were analyzed using STATA 12 software.

Results:

Analysis of 58 primary articles with a sample size of 902580 showed that the prevalence of HTN in Iran was 25% (with 95% CI of 22-28). The highest prevalence of HTN was related to elderly (42%). The prevalence of HTN was 25% (95% CI: 19-31) in women and 24% (95% CI: 20-28) in men with no significant difference (p = 0.758). The results also in-dicated that the prevalence of HTN was not related to the year of studies (p = 0.708) or sample size (p = 769).

Conclusion:

Despite the advancements in science and technology, along with health and prevention of diseases, the overall prevalence of HTN raised in Iran. Since HTN is a silent disease with significant health consequences and economic burden, programs designed to better HTN control seem vital to enhance community health.

Keywords: Prevalence, HTN, systematic review and meta-analysis, Iran, age, region

1. INTRODUCTION

There is convincing evidence that the world is faced with an increased prevalence of hypertension (HTN) [1]. 31% of the world’s adults had HTN in 2010 [2] (Mills, et al. 2015). HTN is a worldwide health problem and the most important factor in increasing the burden of disease in the world [3, 4]. Among the 25 factors leading to disability, HTN (HTN) was ranked fourth in 1990 and then ranked as the first factor in 2010 [5].

HTN is associated with a high incidence of debilitating complications, such as stroke, heart attacks, and renal failure, which impose a large economic burden on society. For example, estimates indicate that 54-6.64% of stroke and 47% of coronary heart disease worldwide are due to HTN [6, 7]. Findings revealed that HTN increases the risk of dementia [8, 9] and depression [10] in the elderly. Worldwide, costs to treat HTN and its consequences are substantial. For instance, it is predicted that the future cost of cardiovascular complications caused by HTN in the United States would be raised 238% from 2010 to 2030 [11].

The prevalence of HTN varies across the world considerably. Its prevalence was 39.1% in Latin America, 26.9% in the Middle East and North Africa, 29.4% in South Asia, 31.5% in European and Central Asia countries, 31.1% in Sub-Saharan Africa, and 35.7% in East China and the pacific [12]. The results of a meta-analysis study in 2012 indicated that the prevalence of HTN in China was 21.5% [13]. In Iran, two meta-analyses have been conducted related to the prevalence of HTN in 2008 and 2012. According to the first study, the prevalence of HTN in the 30-55 age group and older than 55 years, were 23% and 50%, respectively [14]. In 2012, the prevalence of HTN in adults was 22% [15]. In addition, various studies have been carried out on the prevalence of HTN in different parts of Iran which reported different rates [16-18]. Evidence suggests that in developing countries such as Iran, better care and more effective disease treatment has increased life expectancy that followed by increasing of elderly population; consequently raising of the elderly population leads to an increase in the prevalence of HTN [19, 20].

The prevalence of HTN can be affected by demographic factors, such as age, race, gender, and socio-economic status [21]. Iran is a large country in the eastern half of the Middle East with approximately 70 million people with different ethnicities. Ethnic diversity in Iran results in very different cultures, lifestyles, and socioeconomic status that may affect individuals’ blood pressure. This study aimed to estimate an overall prevalence of HTN in Iran and provide more current estimates.

2. METHODOLOGY

The protocol of this review has been registered in the International prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO) with the number of CRD42017068574.

2.1. Search Strategy

This systematic and meta-analysis of HTN in Iranian society was reviewed based on studies published in national and international journals between 2004 and 2018. We used the following databases: Magiran, Iran Medex, the Iranian Archive for Scientific Documents Center (IASD), the Iranian National Library (INL), Medline (PubMed, Ovid), Scopus, Web of Science Embase. Google Scholar and Google were used as a search engine. Also, grey literature was examined for related articles. The keywords including “systolic”, “diastolic”, “blood pressure”, ” hypertension”, “white coat HTN”, “Iran”, “prevalence”, and combinations of these using Boolean operators and “*” were used to search for primary studies. Given the definition of blood pressure by the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7), which determined HTN as BP ≥ 140/90 [22]; so our criteria of HTN in analyzed studies were SBP ≥140 mm Hg and DBP ≥90 mm Hg. The screening and selection process was conducted according to PRISMA guidelines [23].

2.2. Selection of Studies and Data Extraction

All observational (non-interventional) studies that referred to the frequency or prevalence of HTN in Iranian society were included in the study. Exclusion criteria were related to the interventional studies, letters to the editor, studies on pregnant women and children, and studies with poor methodological quality. Also, studies without keywords of blood pressure, HTN, Iran, systolic, diastolic, and prevalence were excluded. For some articles which were published in both Persian and English language, we analyzed the one with more detailed data. For data extraction, the form we used included the variables of the first author of the studies, year of publication, setting, total sample size, sample size in men and women, number of patients with HTN in general and by sex. According to inclusion and exclusion criteria, titles and abstracts of primary studies were independently assessed by two researchers and for related articles, the full texts were extracted and assessed. In case of disagreement between the two researchers, the article was assessed by the third author who was an expert in the meta-analysis.

2.3. Evaluation and Review Articles

To assess the quality of the primary studies, we used a standard tool which has been applied in various internal and external studies [24-27]. The quality assessment form of the studies included 5 items including research design, sampling method, comparison group, sample size, instrumental psychometric properties. Each item was ranked from 0 to 3 and its overall score ranged from (0 to 15). Accordingly, the studies were divided into three groups: weak (0 to 5), moderate (5-10) and strong (10 up) [26]. The quality of the studies was investigated by two researchers (M.J. and R.G.) and the differences were resolved by the third author (F.M). All studies had moderate to high quality, then all of them were entered to the analysis.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Regarding the prevalence rate with a binomial distribution, the variance of each research was calculated through binomial distribution variance. The weighted average was used to combine the prevalence rates of the studies. The weight assigned to each study was the inverse of its variance. The I2 index was used to examine the heterogeneity of data. Heterogeneity of data was divided into three classes of less than 25% (low heterogeneity), 25% to 75% (moderate heterogeneity) and over 75% (high heterogeneity). Given the high heterogeneity of the data, the random effects model was used. Subgroup analysis was performed based on gender, age, type of study and population. To assess trends of prevalence of HTN from 2004 to 2017, we categorized primary studies based on the study conducted time into four period time of 2004-2006, 2007-2009, 2010-2012, and 2013-2017. The increase in the period of 2013-2017 was due to the low number of primary articles. Meta-regression method was used to investigate the correlation between the prevalence of HTN and the year of study, and the number of samples. Publication bias was assessed with the Egger test. Data analysis was done with STATA 12 software.

3. RESULTS

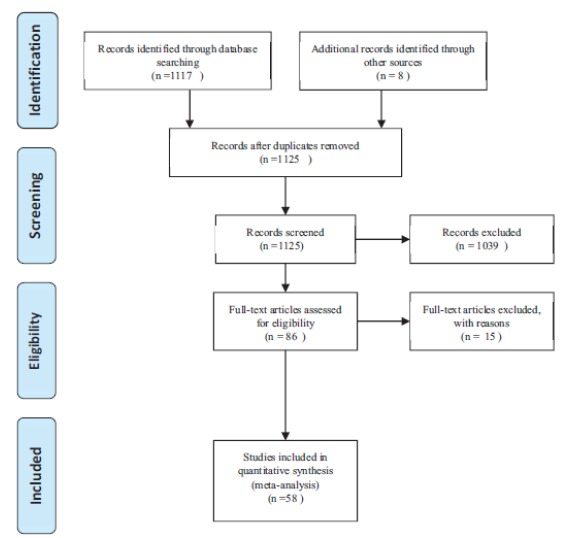

In this study, all studies related to the prevalence of blood pressure in Iranian society from 2004 to 2017, were systematically assessed according to the PRISMA guidelines (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The process of selecting articles based on PRISMA.

In the initial search, 1123 papers were identified, which eventually led to 58 eligible studies entered to the final analysis. The total sample size was 902,580 subjects with an average of 15743 per study. The lowest and highest sample sizes were related to Akbarzadeh (2009) [28] and Faramarzi (2009) [29] respectively. 52 of the studies were cross-sectional, and five were cohort studies. The characteristics of the articles are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the final papers entered in the analysis.

| Row | First Authour | Study Design | Year |

Sample

Size |

Setting | Target Population | Prevalence (%) | Language |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ghanbariyan et al. | Cross-sectional | 2004 | 8491 | Tehran | Adults | 22 | Persian |

| 2 | Taraghi et al. | Cross -sectional | 2004 | 122 | Sari | Adult drivers | 36.9 | Persian |

| 3 | Godarzi et al. | Cross -sectional | 2005 | 1530 | Zabul | Adults | 13.9 | Persian |

| 4 | Delavari et al. | Cross- sectional | 2005 | 24525 | national project | Adults | 30.5 | Persian |

| 5 | Delavari et al. | Cross -sectional | 2005 | 13033 | national project | Adults | 29.2 | Persian |

| 6 | Yousefinejad et al. | Cross-sectional | 2006 | 1854 | Sanandaj | Adults with blood transfering | 3.4 | Persian |

| 7 | Sharifi rad et al. | Cross- sectional | 2007 | 255 | Esfahan | elderly | 46.7 | Persian |

| 8 | Delavari et al. | Cross- sectional | 2007 | 75112 | national project | Adults | 30.2 | Persian |

| 9 | Rafiee et al. | Cross -sectional | 2007 | 458 | Arak | Postmenopausal women | 65.5 | Persian |

| 10 | Dabbaghmanesh et al. | Cross-sectional | 2008 | 3245 | Shiraz | Adults | 27.5 | Persian |

| 11 | Esteghamati et al. | Cross -sectional | 2008 | 68250 | national project | Adults | 32 | English |

| 12 | Esteghamati et al. | Cross -sectional | 2009 | 5287 | national project | Adults | 26.6 | English |

| 13 | Mardani et al. | Cross -sectional | 2009 | 340 | Arak | Adults | 13.5 | Persian |

| 14 | Akbarzadeh et al. | Cross-sectional | 2009 | 107 | Shiraz | Adult women | 12.15 | Persian |

| 15 | Akbarzdseh et al. | Cross-sectional | 2009 | 107 | Shiraz | Adult women | 3.7 | Persian |

| 16 | Amirkizi et al. | Cross-sectional | 2009 | 370 | Kerman | Women with reproductive age | 14.3 | Persian |

| 17 | Faramarzi et al. | Cross -sectional | 2009 | 447251 | Shiraz | Adults | 21 | Persian |

| 18 | Ramazani et al. | Cross sectional | 2009 | 3670 | Esfahan | Adults | 20.7 | English |

| 19 | Neghab et al. | Cohort | 2009 | 140 | Shiraz | Petrochemical personnel | 20 | English |

| 20 | Neghab et al. | Cohort | 2009 | 140 | Shiraz | Petrochemical personnel | 12.8 | English |

| 21 | Veghari et al. | Cross -sectional | 2010 | 2497 | Golestan | Adults | 23.9 | Persian |

| 22 | Sahebi et al. | Cross-sectional | 2010 | 1027 | Shiraz | Hospital staff | 37 | English |

| 23 | Kasai et al. | Cross -sectional | 2010 | 1000 | Zanjan | Adults | 27.8 | English |

| 24 | Ebrahimi et al. | Cross -sectional | 2010 | 30000 | National project | Adults | 17.3 | English |

| 25 | Sharifi et al. | Cross- sectional | 2010 | 266 | Tehran | Elderly | 61 | English |

| 26 | Damrchi et al. | Cross -sectional | 2010 | 1218 | Tehran | Drivers | 35.4 | Persian |

| 27 | Kalani et al. | Cross -sectional | 2011 | 1130 | Yazd | Adults | 38.1 | Persian |

| 28 | Ghazanfari et al. | Cross- sectional | 2011 | 400 | Kerman | Adults | 23.8 | Persian |

| 29 | Saharki et al. | Cross-sectional | 2011 | 2300 | Zahedan | Adults | 27 | English |

| 30 | Abtahi et al. | Cross-sectional | 2011 | 3115 | Shiraz | Teachers | 18.2 | English |

| 31 | Namayandeh et al. | Cross-sectional | 2011 | 2000 | Yazd | Adults | 42.5 | English |

| 32 | Khosh andam et al. | Cross-sectional | 2011 | 400 | Mazandaran | Drivers | 20 | Persian |

| 33 | Peyman et al. | Cross-sectional | 2012 | 121 | Ilam | Elderly | 36.8 | Persian |

| 34 | Moeni et al. | Cross-sectional | 2012 | 2063 | Esfahan | Elderly with heart disease | 4 | English |

| 35 | Ghari poor et al. | Cross sectional | 2012 | 975 | Esfahan | Adults | 18.9 | English |

| 36 | Barikani et al. | Cross-sectional | 2012 | 328 | Ghazvin | women Adults | 32 | English |

| 37 | Maracy et al. | Cross sectional | 2012 | 3000 | Esfahan | Adults | 22.2 | English |

| 38 | Rezaiean et al. | Cross-sectional | 2012 | 445 | Hamadan | Kidney patients | 22.2 | English |

| 39 | Mahram et al. | Cross-sectional | 2013 | 5231 | Ghazvin | Water-containing arsenic consumer | 7 | English |

| 40 | Mahram et al. | Cross-sectional | 2013 | 9838 | Ghazvin | Above control group | 3.7 | English |

| 41 | Malek Zadeh et al. | Cross-sectional | 2013 | 50045 | Gholston | Adults | 42.7 | English |

| 42 | Ahmadi et al. | Cohort | 2014 | 2570 | Tehran | Patient with rectum cancer | 13.4 | English |

| 43 | Safari Moradabadi et al. | Cross sectional | 2014 | 1531 | Bandar abas | Adults | 35.3 | Persian |

| 44 | Chraghian et al. | Cross sectional | 2014 | 69173 | Tehran | Adults | 5.3 | English |

| 45 | Najafi poor et al. | Cross sectional | 2014 | 5900 | Adults | 18.4 | English | |

| 46 | Talayi et al. | Cohort | 2014 | 3283 | Esfahan | Adults | 25.4 | English |

| 47 | Kalani et al. | Cross-sectional | 2015 | 1130 | Yazd | Adults | 38.1 | English |

| 48 | Yazdan panah et al. | Cross -sectional | 2015 | 944 | Ahvaz | Adults | 17.6 | English |

| 49 | Poorolajal et al. | Cross -sectional | 2015 | 7611 | Tehran | Clinical patients | 9.1 | English |

| 50 | Chraghi et al. | Cross- sectional | 2016 | 476 | Bahar | elderly | 25 | Persian |

| 51 | Gerayloo et al. | Cross-sectional | 2016 | 227 | Moraveh tapeh | Employees | 8.3 | Persian |

| 52 | Mojahedi et al. | Cross-sectional | 2016 | 3608 | Mashad | youngs | 1.4 | Persian |

| 53 | Esteghamati et al. | Cross- sectional | 2016 | 8218 | national project | Adults | 25.6 | English |

| 54 | Ghaffari et al. | Cross -sectional | 2016 | 1071 | Tabriz | elderly | 68 | English |

| 55 | Jamshidi et al. | Cross -sectional | 2017 | 321 | Hamadan | elderly | 16.2 | English |

| 56 | Ebrahimi et al. | Cross-sectional | 2014 | 9762 | Mashhad | Adults | 23 | English |

| 57 | Khajedaluee et al. | Cross-sectional | 2016 | 2974 | Mashhad | Adults | 22 | English |

| 58 | Khosravi et al. | Cohort | 2013 | 5190 | Shahroud | Adults | 38.2 | English |

Table 1. Selected articles for meta-analysis of hypertension in Iran 2004-2017.

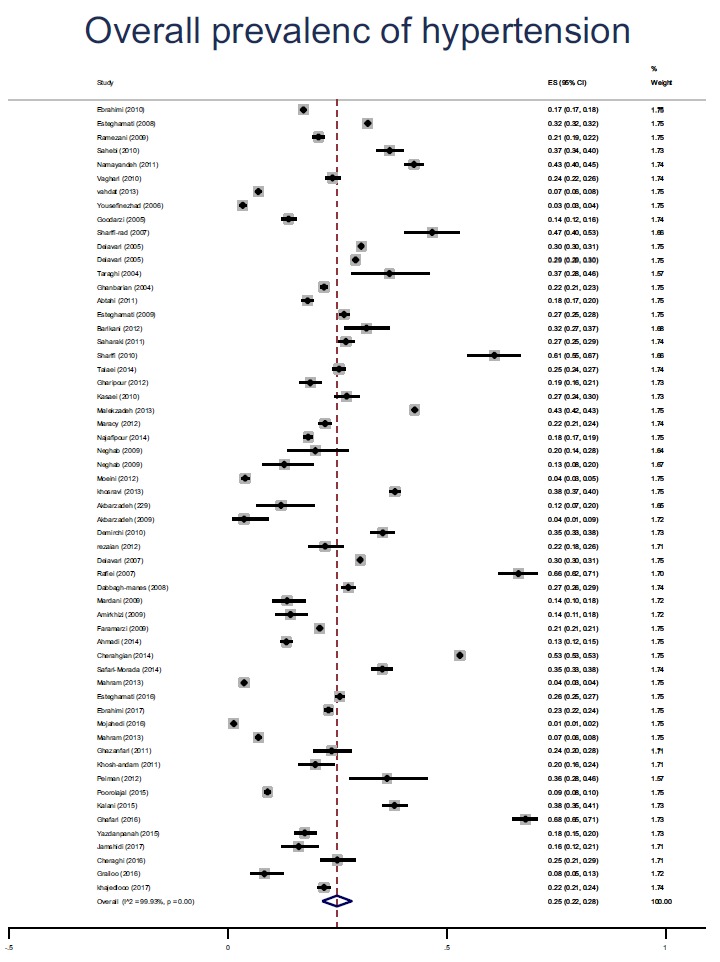

The findings showed that the overall prevalence of HTN in Iranian society was 25% (95% CI: 22 - 28%). The prevalence of HTN in cross-sectional studies (27% with a 95% CI of 23-30) was more than cohort studies (22% with 95% CI of 11 - 33). The findings also showed that the prevalence of HTN in older adults was higher than other age groups (42% with 95% CI: 22-62), the prevalence of HTN was 25% (95% CI: 19-31) in women and 24% (95% CI: 20-28) in men, with no significant difference (p = 0.758). The findings showed that the highest and the lowest prevalence of HTN were in Region 3 (East Azarbaijan, West Azarbaijan, Ardebil, Zanjan, Guilan and Kurdistan provinces) and region 2 (Isfahan, Fars, Bushehr, Chaharmahal Bakhtiari, Hormozgan and Kohkiloyeh and Boyerahmad provinces) (33% versus 22%), respectively. Further details of the prevalence of HTN in the subgroups are presented in Table 2. The pooled prevalence of HTN is shown in Fig. 2.

Table 2. Prevalence of HTN based on subgroup.

| Variable | Categories | Number of Studies | Sample Size | Prevalence (%) | Confidence Interval 95% | Hetrogenicity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 | P | ||||||

| Type of study | Cross sectional | 52 | 898598 | 26 | 23-30 | 99.9 | 0.0001 |

| Cohort | 5 | 6374 | 22 | 7-21 | 97.6 | 0.0001 | |

| Language of study | English | 28 | 3510 | 25 | 19-29 | 99.9 | 0.0001 |

| Persian | 21 | 362495 | 24 | 21-31 | 99.9 | 0.0001 | |

| Population | Drivers | 3 | 1740 | 31 | 19-42 | 95.3 | 0.0001 |

| Patients | 4 | 15081 | 12 | -4)-60) | 100 | 0.0001 | |

| Women | 5 | 1370 | 26 | 3-47 | 99.2 | 0.0001 | |

| Elderly | 6 | 2510 | 42 | 22-62 | 99.2 | 0.0001 | |

| Adults | 40 | 904972 | 24 | 18-26 | 99.9 | 0.0001 | |

| Gender | Male | 23 | 404580 | 24 | 20-28 | 99.9 | 0.0001 |

| Female | 23 | 383542 | 25 | 19-31 | 99.9 | 0.0001 | |

| Region | Region1 | 15 | 200736 | 24 | 14-30 | 100 | 0.0001 |

| Region2 | 15 | 472301 | 22 | 16-36 | 99.9 | 0.0001 | |

| Region3 | 3 | 3925 | 33 | (-5)-72 | 99.9 | 0.0001 | |

| Region4 | 7 | 3105 | 28 | 15-40 | 98.9 | 0.0001 | |

| Region5 | 11 | 31104 | 24 | 14-33 | 99.8 | 0.0001 | |

| Unknown | 7 | 162995 | 27 | 23-31 | 99.9 | 0.0001 |

Region 1: Provinces of Tehran, Alborz, Qazvin, Mazandaran, Semnan, Golestan and Qom; Region 2: Isfahan, Fars, Bushehr, Chaharmahal Bakhtiari, Hormozgan and Kohkiloyeh and Boyerahmad provinces; Region 3: East Azarbaijan, West Azarbaijan, Ardebil, Zanjan, Gilan and Kurdistan; District 4: Kermanshah, Ilam, Lorestan, Hamedan, Central and Khuzestan provinces; District 5: Khorasan Razavi, Southern Khorasan, Northern Khorasan, Kerman, Yazd and Sistan and Baluchestan provinces.

Fig. (2).

The pooled Prevalence of hypertension based on the studies in Iran. The 95% confidence range for each study is in the form of horizontal lines around the original average. The dotted line in the middle represents the overall prevalence estimates. Diamond shape represents the overall prevalence is assured.

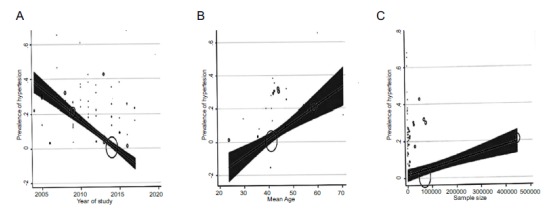

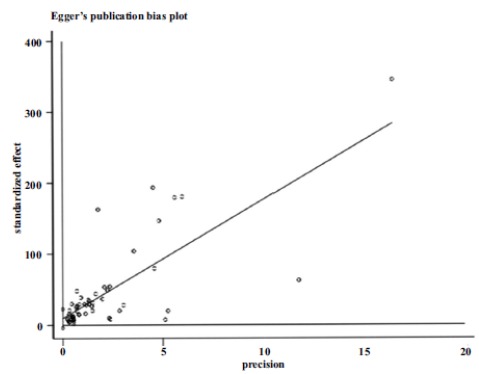

The trend of prevalence of HTN in Iran, from 2004 to 2017 is shown in Table 3. The prevalence of HTN in Iran was not significantly correlated with the year (p = 0.708), and sample size (p = 769), but In relation to the mean age of the samples, showed a significant correlation (p = 0.003) (Fig. 3). According to Fig. 4, the results of the Egger test showed that the bias of publication of the preliminary studies is not significant (p = 0.172).

Table 3. Trend of prevalence of hypertension from 2004 to 2017 in Iran.

| Years | Number of Studies | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 2004-2006 | 14 | 26 |

| 2007-2009 | 25 | 26 |

| 2010-2012 | 11 | 22 |

| 2013-2017 | 8 | 26 |

Fig. (3).

Meta-regression prevalence of hypertension based on years of study (A), age of individuals (B), and sample size of studies (C).

Fig. (4).

Bias of publication of the preliminary studies.

4. DISCUSSION

In our systematic and meta-analytical review, 58 primary articles were investigated to estimate the overall prevalence of HTN in Iran. This study covers all areas of Iran with 31 provinces. All data were collected from 2004 to 2017. A systematic study related to the prevalence of HTN in Iran has not been conducted recently, and the latest related study was done around 5 years ago [15]. Because the findings of the present study are based on a large number of primary studies, our study can be fitted to the needs of health providers.

The overall prevalence of HTN in Iran was 25%, which was different in cross-sectional and cohort studies, with a prevalence of 26% and 22%, respectively. Among the 51 European countries in 2014, the minimum and maximum prevalence of HTN were related to the United Kingdom (15.2%) and Estonia (31.7%) [30]. Analyzing studies until 2015 in low- and middle-income countries, have shownthat the overall prevalence of HTN was 32.3% [12].

Comparison of the results shows the prevalence of HTN in different countries varies, however, remains approximately near to each other. Variations in the reported prevalence in several countries can be due to genetic and environmental factors (like exercising), also it can be due to the heterogeneity of research methods and the rate of controlling of variables like age and sex in studies.

To study more accurately of the prevalence of HTN in Iran, the trend of prevalence of HTN was assessed from 2004 to 2017. The finding showed nearly a similar trend of prevalence of HTN during periods of 2004-2006, 2007 to 2009, and 2013 to 2017. Through the period from 2010 to 2012, the prevalence of HTN was lower than others. The major source of the low prevalence of HTN in this period of time could be related to the three primary studies [31, 32] that with a very low prevalence of HTN (below th 0.07) which has had a descending impact on the total prevalence of HTN over this period. Two of these three studies were conducted by Mahram et al. [31]{Mahram, 2013 #2724}, with population age of 30-60 years-old and the third one conducted by Mojahid et al. [32], with young people with the age of 20-29. It seems that the most important factor in reducing the prevalence of HTN in these three studies and subsequently in the period time of 2010 to 2012 was ages of subjects. Because the prevalence of HTN is directly related to age and all the samples studied in these three studies were young and adult. While other studies, in addition to low age groups, included elderly population too. By excluding of these three studies and re-analyzing, the prevalence of HTN was equal to other periods. Assessing the trend of prevalence of HTN shows that, the prevalence of HTN has not diminished versus progress and development in people's lives, and its rate has been roughly the same throughout 2004-2017. in Iran, comparing the results of previous same studies with the result of our study showed that the overall prevalence of HTN is increasing (25% versus 23% and 21%) [14, 15]. the prevalence of HTN in the United States and China was 28% [33] and 27% [34] in 2009 and 2007 which are lower than the recently reported prevalence of 29% [1] and 35/7% [12], respectively.

Considering the trend of prevalence of HTN over periods of years from 2004 to 2017 and increasing of overall prevalence of HTN in recent studies comparing to the past ones, it can found that with the advancement of technology, treatment, care and disease prevention, over the time, decreasing of the prevalence of HTN has not happened. A possible explanation of this trend of HTN may be related to economic development, urbanization, aging of population, lifestyle changes, bad diet and environmental degradation. In addition, an increase in obesity and overweight, lipid disorders, high salt intake, smoking, sedentary and inadequate lifestyle can also are exacerbating factors [13].

Because of the high heterogeneity in the primary studies, the prevalence of HTN was estimated based on sub-group analysis.

Subgroup analysis results showed that the elderly group has the highest prevalence of HTN (42%) compared to other groups, which is consistent with other studies like the United States with 63.1% [1], previous meta-analysis in Iran with 50% [14], and low- and middle-income countries with 65.6% [12]. The high prevalence of HTN in the elderly can be attributed to various factors such as atherosclerosis and their underlying conditions [35].

After the elderly group, drivers had the most prevalence of HTN. In this case, we can say that half of the drivers are at the pre-hypertensive stage and most of them were overweight and obese in Iran [36]. The lack of attention to health issues in this group has led them to suffer from HTN. The cause of overweight in the drivers may be because of the use of restaurant fatty foods and the lack of information on their diet and inactivity with being in more sitting position.

In the present study, the prevalence of HTN in men was slightly higher than women. However, this difference was not statistically significant and is consistent with other studies [12, 30, 33, 37, 38]. The reason for this difference may be that that middle-aged men are prone to cardiovascular disease [12]. Also, in Iran, Men are more likely to work outside the home with a stressful situation compared women and they are less concerned about their self-care, taking anti-hypertensive medications, and doing exercise, which could lead to an increased prevalence of HTN in them [39]. However, in the United States and the Netherlands, HTN was reported more frequently in women than men [34]. In Yemen, as a low-income country, HTN was slightly higher in women than in men (14.8% versus 14.2%) [40]. Nonetheless, the high prevalence of HTN in women, as compared to men, may be due to a higher BMI, lifestyle and menopause period [41].

The findings showed that the third region (provinces of East Azarbaijan, West Azarbaijan, Ardebil, Zanjan, Gilan and Kurdistan) and the second region (provinces of Tehran, Alborz, Qazvin, Mazandaran, Semnan, Golestan and Qom) have the highest and lowest incidence of HTN, respectively. Results of related studies with regard to the area of residence and size of cities and its relation to the prevalence of HTN indicated that cities with the average size compared to small size, had the highest prevalence of HTN (24.6% versus 20.6%) and large cities also had the lowest prevalence of HTN (18.9%) [42]. A study by Adeloye et al. showed that the prevalence of HTN in rural areas was lower than in urban areas (31% versus 26%) [43]. Also in African countries, the prevalence of HTN was even more among urban residents [43]. The higher prevalence of HTN among the third region populations may be due to their different lifestyle patterns. Factors such as lack of mobility, air pollution, industrial stress, fast food and high fat and high-fat diet could increase the prevalence of HTN in industrial cities compared to semi-industrial cities and rural areas [44]. However, the results of some studies also indicated an increased prevalence of HTN in marginal and rural areas [45]. The possible reason for this could be that, although the rural areas are a stress-free environment for living, a low level of health literacy, less access to health centers, and educational facilities could lead to increased prevalence of HTN. In addition of environmental and lifestyle characteristics which are different in five regions of Iran and could effect on HTN prevalence ratio, also the study characteristics, such as the type of sampling, the age of the population studied, the amount of knowledge and experience of the researchers in the correct guidance of the study could also influence the difference of the prevalence in the different regions.

According to our meta-regression results, the prevalence of HTN in Iran was not significantly different based on year of study and sample size, except age. A study in China showed that, the prevalence of HTN in the years 2011-2007 was nearly similar in the years of 2006-2002 (20.6% vs. 21.9%) (13). Also, our meta-regression result indicated that with aging, the prevalence of HTN is increasing significantly, which is in line with previous studies [1, 12, 30].

CONCLUSION

The current prevalence of HTN is high and its trend over time, has been fixed without a reduction in Iran. There were differences in the prevalence of HTN and variables such as age, gender, population. Older adults as compared to other population groups have the highest rate of prevalence. The reasons for not reducing the prevalence of HTN should be investigated and strategies for controlling and reducing it should be planned.

One of the most important limitations of this study was the lack of adequate information reported by some studies. However, the study has strengths of covering more databases and comprehensive reviews made it possible to access the majority of related primary studies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fryar C.D., Ostchega Y., Hales C.M., Zhang G., Kruszon-Moran D. Hypertension prevalence and control among adults: United States, 2015-2016. NCHS Data Brief. 2017;289:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mills K.T., Bundy J.D., Kelly T.N., et al. Global disparities of hypertension prevalence and control. Circulation. 2016;134(6):441–450. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim S., Vos T., Flaxman A., Danaei G., Shibuya K., Adair-Rohani H. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990-2010: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2224–2260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baillie I. Insight: Non-destructive testing and condition monitoring. Bindt. 2018;60(2):62. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray C.J.L., Lopez A.D. Measuring the global burden of disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369(5):448–457. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1201534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forouzanfar M.H., Liu P., Roth G.A., et al. Global burden of hypertension and systolic blood pressure of at least 110 to 115mmHg, 1990-2015. JAMA. 2017;317(2):165–182. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.19043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheeran P., Gollwitzer P.M., Bargh J.A. Nonconscious processes and health. Health Psychol. 2013;32(5):460–473. doi: 10.1037/a0029203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ninomiya T., Ohara T., Hirakawa Y., et al. Midlife and late-life blood pressure and dementia in japanese elderly: The hisayama study. Hypertension. 2011;58(1):22–28. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.163055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wysocki M., Luo X., Schmeidler J., et al. Hypertension is associated with cognitive decline in elderly people at high risk for dementia. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2012;20(2):179–187. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31820ee833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tel H. Anger and depression among the elderly people with hypertension. Neurol. Psychiatry Brain Res. 2013;19(3):109–113. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heidenreich P.A., Trogdon J.G., Khavjou O.A., et al. Forecasting the future of cardiovascular disease in the United States: A policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123(8):933–944. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31820a55f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarki A.M., Nduka C.U., Stranges S., Kandala N.B., Uthman O.A. Prevalence of hypertension in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (United States) 2015;94(50):e1959. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma Y.Q., Mei W.H., Yin P., Yang X.H., Rastegar S.K., Yan J.D. Prevalence of hypertension in Chinese cities: A meta-analysis of published studies. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e58302. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haghdoost A.A., Sadeghirad B., Rezazadehkermani M. Epidemiology and heterogeneity of hypertension in Iran: A systematic review. Arch. Iran Med. 2008;1:444–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mirzaei M., Moayedallaie S., Jabbari L., Mohammadi M. Prevalence of hypertension in Iran 1980-2012: A systematic review. J. Tehran Univ. Heart Cent. 2016;11(4):159–167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Basiratnia M., Derakhshan D., Ajdari S., Saki F. Prevalence of childhood obesity and hypertension in south of Iran. Iran. J. Kidney Dis. 2013;1:282–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rafraf M., Pourghassem Gargari B., Safaiyan A. Prevalence of prehypertension and hypertension among adolescent high school girls in Tabriz, Iran. Food Nutr. Bull. 2010;31(3):461–465. doi: 10.1177/156482651003100308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yazdanpanah L., Shahbazian H., Shahbazian H., Latifi S-M. Prevalence, awareness and risk factors of hypertension in southwest of Iran. J. Renal Inj. Prev. 2015;4(2):51–56. doi: 10.12861/jrip.2015.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma W.J., Tang J.L., Zhang Y.H., et al. Hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, control, and associated factors in adults in Southern China. Am. J. Hypertens. 2012;25(5):590–596. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2012.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fezeu L., Kengne A.P., Balkau B., Awah P.K., Mbanya J.C. Ten-year change in blood pressure levels and prevalence of hypertension in urban and rural Cameroon. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2010;64(4):360–365. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.086355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lloyd-Jones D., Adams R., Carnethon M., et al. Hypertension: A Companion to Braunwald’s Heart Disease. 2nd ed. Elsevier Inc.; 2012. Epidemiology of hypertension. p. 488. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chobanian A.V., Bakris G.L., Black H.R., et al. Seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206–1252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liberati A., Altman D.G., Tetzlaff J., et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–e34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghanei Gheshlagh R., Nazari M., Baghi V., Dalvand S., Dalvandi A., Sayehmiri K. Underreporting of needlestick injuries among healthcare providers in iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hayat (Tihran) 2017;23(3):201–213. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghanei Gheshlagh R., Sayehmiri K., Ebadi A., Dalvandi A., Dalvand S., Nourozi Tabrizi K. Resilience of patients with chronic physical diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Iran. Red Crescent Med. J. 2016;18(7):e38562. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.38562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsimicalis A., Stinson J., Stevens B. Quality of life of children following bone marrow transplantation: Critical review of the research literature. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2005;9(3):218–238. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoodin F., Weber S. A systematic review of psychosocial factors affecting survival after bone marrow transplantation. Psychosomatics. 2003;44(3):181–195. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.44.3.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akbarzadeh M., Moradi F., Dabbaghmaneh M.H., Jafari P., Parsaneshad M.A. A survey of hypertension and hyperandrogenemia in the first degree relatives of women with polycystic ovarian syndrome referring to gynecology clinics of Shiraz Medical University. Pars J Med Sci. 2011;9(2):26–32. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Faramarzi H., Bagheri P., Bahrampour A., Halimi L., Rahimi N., Ebrahimi M. The comparison of prevalence of diabete and hypertension between rural areas of fars and rural area of EMRO region. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011;13(2):157–164. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilkins E., Wilson L., Wickramasinghe K., et al. European cardiovascular disease statistics 2017. European Heart Network, Publisher; AISBL, Rue Montoyer 31, B-1000 Brussels, Belgium: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahram M., Shahsavari D., Oveisi S., Jalilolghadr S. Comparison of hypertension and diabetes mellitus prevalence in areas with and without water arsenic contamination. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2013;18(5):408–412. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mojahedi M.J., Hami M., Shakeri M.T., Mohammad Hossein Hassani M.A. Prevalence of high blood pressure in young people and its related risk factors in Mashhad. Med J Mashhad Univ Med Sci. 2015;58(2):252–257. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pereira M., Lunet N., Azevedo A., Barros H. Differences in prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension between developing and developed countries. J. Hypertens. 2009;27(5):963–975. doi: 10.1097/hjh.0b013e3283282f65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang J., Lu F., Zhang C., et al. Prevalence of prehypertension and hypertension in a Chinese rural area from 1991 to 2007. Hypertens. Res. 2010;33(4):331–337. doi: 10.1038/hr.2009.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun Z. Aging, arterial stiffness, and hypertension. Hypertension. 2015;65(2):252–256. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taraghi Z., Hali E. Hypertension screening in truck drivers. Hayat (Tihran) 2004;10(21):95. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Addo J., Smeeth L., Leon D.A. Hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. Hypertension. 2007;50(6):1012–1018. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.093336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cooper R.S., Amoah A.G.B., Mensah G.A. High blood pressure: The foundation for epidemic cardiovascular disease in African populations. Ethn. Dis. 2003;13(2) Suppl. 2:S2–S52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bello M. Nigerians wake up to high blood pressure. Bull. World Health Organ. 2013;91(4):242–243. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.020413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Delavari A.R., Horri N., Alikhani S., et al. Prevalence of hypertension in Iranian urban and rural populations aged over 20 years in 2004. Majallah-i Danishgah-i Ulum-i Pizishki-i Mazandaran. 2007;17(58):79–86. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Efstratopoulos A.D., Voyaki S.M., Baltas A.A., et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in Hellas, Greece: The hypertension study in general practice in Hellas (HYPERTENSHELL) national study. Am. J. Hypertens. 2006;19(1):53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van de Poel E., O’Donnell O., Van Doorslaer E. Urbanization and the spread of diseases of affluence in China. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2009;7(2):200–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adeloye D., Basquill C., Aderemi A.V., Thompson J.Y., Obi F.A. An estimate of the prevalence of hypertension in Nigeria: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Hypertens. 2015;33(2):230–242. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mezue K. The increasing burden of hypertension in Nigeria - Can a dietary salt reduction strategy change the trend? Perspect. Public Health. 2014;134(6):346–352. doi: 10.1177/1757913913499658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mainous A.G., King D.E., Garr D.R., Pearson W.S. Race, rural residence, and control of diabetes and hypertension. Ann. Fam. Med. 2004;2(6):563–568. doi: 10.1370/afm.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]