Abstract

The Baby‐Friendly Community Initiative (BFCI) is an extension of the 10th step of the Ten Steps of Successful Breastfeeding and the Baby‐Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) and provides continued breastfeeding support to communities upon facility discharge after birth. BFCI creates a comprehensive support system at the community level through the establishment of mother‐to‐mother and community support groups to improve breastfeeding. The Government of Kenya has prioritized community‐based programming in the country, including the development of the first national BFCI guidelines, which inform national and subnational level implementation. This paper describes the process of BFCI implementation within the Kenyan health system, as well as successes, challenges, and opportunities for integration of BFCI into health and other sectors. In Maternal and Child Survival Program (MCSP) and UNICEF areas, 685 community leaders were oriented to BFCI, 475 health providers trained, 249 support groups established, and 3,065 children 0–12 months of age reached (MCSP only). Though difficult to attribute to our programme, improvements in infant and young child feeding practices were observed from routine health data following the programme, with dramatic declines in prelacteal feeding (19% to 11%) in Kisumu County and (37.6% to 5.1%) in Migori County from 2016 to 2017. Improvements in initiation and exclusive breastfeeding in Migori were also noted—from 85.9% to 89.3% and 75.2% to 92.3%, respectively. Large gains in consumption of iron‐rich complementary foods were also seen (69.6% to 90.0% in Migori, 78% to 90.9% in Kisumu) as well as introduction of complementary foods (42.0–83.3% in Migori). Coverage for BFCI activities varied across counties, from 20% to 60% throughout programme implementation and were largely sustained 3 months postimplementation in Migori, whereas coverage declined in Kisumu. BFCI is a promising platform to integrate into other sectors, such as early child development, agriculture, and water, sanitation, and hygiene.

Keywords: baby friendly, breastfeeding, infant and young child feeding, multisectoral, process documentation, programme implementation

Key messages.

Routine contacts with mothers through home visits, mother and community member engagement via support groups, and linkages between community and health facility services are critical components of BFCI.

BFCI provides a platform to not only improve breastfeeding but also to accelerate improvements in maternal nutrition and complementary feeding practices

BFCI provides a platform to integrate nutrition‐sensitive interventions, such as early childhood development, agriculture initiatives, and water, sanitation, and hygiene.

1. INTRODUCTION

Improving breastfeeding rates globally can prevent over 800,000 deaths in children under 5 years of age annually (Rollins et al., 2016). An increasing body of evidence shows the myriad benefits of breastfeeding for mother and child. These include reducing neonatal and child morbidity and mortality and preventing noncommunicable diseases, such as overweight, diabetes, and some cancers (Hansen, 2016; Rollins et al., 2016; Victora et al., 2016). Despite these benefits, improvements in exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) rates have been uneven. According to the 2017 Global Nutrition Report, only marginal improvements in EBF among infants 0–5 months of age have been demonstrated—with a 2% increase in global EBF rates over the past 10 years (baseline since 2008, postbaseline since 2012; Development Initiatives, 2017). Of countries with available data, at least 27 low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs) have achieved some progress towards achieving World Health Assembly targets of attaining 50% EBF rates by 2025 (World Health Organization [WHO] & UNICEF, 2014), whereas 16 countries have made no progress, or worse, are regressing. To date, either no data or insufficient trend EBF data exists for 150 countries to monitor progress towards global targets (Development Initiatives, 2017). Current international efforts on breastfeeding promotion and support builds on the Innocenti Declarations, in an effort to improve how countries track, monitor, advocate for, and increase investments in breastfeeding through the WHO‐ and UNICEF‐led Global Breastfeeding Collective (Global Breastfeeding Collective, UNICEF, & WHO, 2017). Recent global updates to the Baby‐Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) and the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding (WHO & UNICEF, 1989) provide countries with an evidence‐based package of interventions recommended to support optimal breastfeeding practices (WHO & UNICEF, 2009; UNICEF & WHO, 2018). BFHI aspires to establish early and uninterrupted skin‐to‐skin contact immediately after birth, early initiation of breastfeeding, EBF for the first 6 months of life, rooming‐in day/night for mother and infant in health facilities and the support to address common breastfeeding challenges, and within facility‐based maternal and newborn health services as critical practices as part of a global strategy (WHO & UNICEF, 2009; UNICEF & WHO, 2018). The guidance emphasizes that “sufficient breastfeeding‐support structures” at the community level are vital to ensure that mothers sustain EBF beyond the initial hours or day(s) in maternities at the health facility level (UNICEF & WHO, 2018).

Kenya has made significant gains in EBF practices over the course of the last 20 years—from 15% in 1998 to 61% in 2014—and experienced reductions in under‐five child mortality rates—from 105.2 (per 1,000 live births) to 53.5—(World Bank, 2018; UN Inter‐agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation, UNICEF, World Bank, & UN DESA Population Division, 2018) during the same time period (Kenya National Council for Population and Development, 1999; Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, Kenya Ministry of Health, National AIDS Control Council/Kenya, Kenya Medical Research Institute, National Council for Population and Development/Kenya, 2014). Similarly, the latest estimate of early initiation of breastfeeding (within 1 hour of birth) rate of 62.2% indicates a positive trend since 2003 (49.6%; UNICEF & WHO, 2018). The country provided an enabling environment to support breastfeeding, inclusive of free maternity services and local regulations on breastmilk substitutes. Although 70% of hospitals were designated as baby friendly (1994–2008), signalling facility‐based support for breastfeeding, through the implementation of the BFHI from 1994 to 2008, structural changes in the government across ministries, formation of new subnational administrative units, the deployment of new staff not trained in BFHI (UNICEF & WHO, 2017), and issues around communication on infant and young child feeding (IYCF) within the context of HIV, contributed to few health facilities (11%) being designated baby friendly by 2010 (UNICEF & WHO, 2017).

The government of Kenya has prioritized community‐level support for breastfeeding through the Baby‐Friendly Community Initiative (BFCI). Based on the BFHI's Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding (WHO & UNICEF, 2017), following facility discharge after birth, BFCI builds upon the 10th step of BFHI, by creating a comprehensive support system at the community level through the establishment of mother‐to‐mother and community support groups to improve maternal, newborn, and infant health and nutrition outcomes (WHO & UNICEF, 2009). BFCI is a multisectoral approach to improve IYCF practices, provide lactation support for addressing breastfeeding challenges, and integrate maternal nutrition and nutrition‐sensitive interventions, such as community gardens; water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH); and early childhood development (ECD).

Kenya's efforts to improve breastfeeding rates at the community level through BFCI builds upon the BFCI experience of other countries, such as Cambodia. Cambodia experienced a significant reduction in child mortality, attributed in part by breastfeeding promotion efforts through BFCI. BFCI was implemented from 2004 to 2013 in nearly 7,000 villages, which showed a 49‐point increase in the rate of EBF for 6 months over the course of 5 years (2000–2005), as well as a nearly two‐fold increase in initiation of breastfeeding within the first hour, 35% to 65% from 2005 to 2010 (National Institute of Public Health/Cambodia, National Institute of Statistics/Cambodia, & ORC Macro, 2006; National Institute of Statistics/Cambodia, Directorate General for Health/Cambodia, & ICF International, 2011). In addition, although few countries, such as Italy and Gambia, have documented successes with BFCI, there is a dearth of information on the process of implementation (Africa Population and Health Research Center, 2014; Bettinelli, Chapin, & Cattaneo, 2012). Yet, to our knowledge, the process of BFCI implementation, as part of nutrition and health integrated programming, has not been well described in the peer‐reviewed literature.

1.1. Objectives

To describe the process of implementation of BFCI within the health system in Kenya

To discuss successes, challenges, and lessons learned on BFCI in the country

To discuss opportunities for integration of BFCI into other health areas and sectors

To discuss the future and next steps for BFCI in Kenya

2. METHODS

The Maternal and Child Survival Program (MCSP) is a global United States Agency for International Development (USAID)‐funded programme with a focus on supporting reproductive, maternal, newborn, child health, and nutrition interventions to prevent maternal and child mortality, in 25 low‐ and middle‐income priority countries (MCSP, 2018). In Kenya, MCSP supported the Government of Kenya, Ministry of Health (MOH), from October 2014 to December 2017 in the development of national BFCI guidelines and the subnational roll‐out of BFCI to strengthen service delivery of nutrition interventions provided in public health facilities (i.e., iron folic‐acid supplementation during pregnancy, growth monitoring and promotion and counselling on IYCF, mentoring and supportive supervision of health providers and community‐based workers). The implementation of BFCI, which is designed to promote breastfeeding, complementary feeding, and maternal nutrition was carried out in five counties—Kisumu, Migori, Kericho, Turkana, and Kitui —by the MOH with technical assistance from MCSP and UNICEF (Kenya MOH, 2016). In addition, BFCI was carried out in other areas of the country (i.e., 17 other counties), by the MOH with other implementing nongovernmental organizations. Throughout the implementation of BFCI, ongoing documentation of BFCI activities via MCSP progress reports and collection of MOH routine monitoring data (BFCI monitoring tool; see Table 2) was carried out throughout the duration of the MCSP programme from October 2014 to December 2017. Some documentation (i.e., progress and annual reports) during MCSP's predecessor, the Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program (MCHIP) from July 2009 to September 2014 was also conducted.

Table 2.

Key terms and definitions for BFCI implementation (Kenya MOH, 2007, 2016)

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Orientation | 1 day introductory training for national and county level multi‐sectoral stakeholders, including s village chiefs on the Eight‐Point plan to garner support for BFCI implementation. |

| Training | Capacity building of all partners, health facility and community level staff on BFCI Eight‐Point plan and key messages for MIYCN |

| BFCI monitoring tool |

Data collected as part of the MOH BFCI monitoring and evaluation package on five IYCF indicators: 1. Proportion of infants who are put to the breast within 1 hr of delivery (early initiation of breastfeeding; 0 to 12 months of age) 2. Proportion of infants who are exclusively breastfed in the first 6 months of life (0 to below 6 months of age) 3. Proportion of infants who receive any prelacteal feeds within the first 3 days of life 4. Proportion of infants aged 6 to 8 months who receive complementary foods (semisolid or solid) in addition to breastmilk 5. Proportion of children aged 6 to 11 months who ate any animal‐source, iron‐rich foods in the last 24 hr |

| Community units | Percentage of communities reached through BFCI. Approximately 1,000 households or 5,000 people who reside in the same geographical area and are routinely visited by community health volunteers (1 CHV serves roughly 20 households). |

In December 2017, MCSP led a 3‐day writing workshop in Nairobi, Kenya, with county representatives from the MOH and UNICEF Kenya. These stakeholders were part of the introduction and roll out of BFCI in Kenya, which aided in compilation of lessons learnt. The team conducted extraction of 23 documents, including key government, UN, MCSP, and MCHIP programme documents, and research studies describing BFCI guidelines, implementation, monitoring (i.e., MOH BFCI monitoring and evaluation package), and evaluation and/or external assessment procedures (Table 1). Key terms and definitions for BFCI are described in Table 2.

Table 1.

List of documents reviewed in documentation of BFCI, Kenya, December 2017

| Document type | Documents |

|---|---|

| World Health Organization documents | BFHI guidelines (WHO & UNICEF, 2009) |

| Kenya Ministry of Health documents | Kenya Ministry of Health BFCI implementation guidelines and external assessment protocols (Kenya MOH, 2016) |

| Key national policies, strategies, and plans of action related to maternal, infant and young child nutrition (MIYCN) and community health (Kenya MOH, 2005, 2013) | |

| National Strategy for Maternal Infant and Young Child Nutrition 2012–2017 (Kenya MOH, 2012c) | |

| National Food and Nutrition Security Policy (Kenya MOH, 2011) | |

| National Nutrition Action Plan (Kenya MOH, 2012b) | |

| Strategy for Community Health 2014–2019 (Kenya MOH, 2014) | |

| Breast Milk Substitutes (Regulation and Control) Act No. 34 of 2012 (Ministry for Public Health and Sanitation, 2012) | |

| National Guide to Complementary Feeding 6–23 months (Kenya MOH, 2018a) | |

| Published descriptions and preliminary findings from research studies on BFCI | |

| Baby Friendly Community Initiative: Monitoring Tool and Assessment Protocol ‐ Orientation Package for Health Workers and Community Health Workers (Kenya MOH, 2012a) | |

| National BFCI training materials | BFCI implementation guidelines |

| BFCI trainers guide | |

| National MIYCN counselling cards | |

| Documentation of BFCI implementation, with actual programme coverage | |

| MOH BFCI monitoring tools program monitoring data on five infant and young child feeding (IYCF) indicators from | |

| MCSP and MCHIP documents | MCSP and MCHIP quarterly and annual reports |

| Data | DHIS2 data |

| Systematic tracking of breastfeeding problems via a MCSP breastfeeding checklist tool |

3. RESULTS

Implementation of BFCI in Kenya utilized an integrated, multilevelled approach. First, we describe the process of government buy‐in for BFCI, followed by the experience of implementation through key routine health contact points and sectors.

3.1. What was the process for gaining government support for BFCI?

In 2003, Kenya Demographic and Health Survey data revealed more than half (59%) of mothers deliver at home (Kenya Central Bureau of Statistics, Kenya Ministry of Health, & ORC Macro, 2004). Realizing the importance of service delivery interventions at the community level, the Kenya MOH launched the “Essential Package for Health at the Community Level” strategy, which mandates roll out of key interventions, including maternal infant and young child nutrition (MIYCN; Kenya National Bureau of Statistics et al., 2003). Subsequently, in 2010, the MOH Division of Nutrition engaged the USAID‐funded MCHIP, a global integrated health project, to carry out community‐based MIYCN nutrition activities (Kenya MOH, 2005), inclusive of strengthening IYCF. BFCI was proposed to the MOH by MCHIP as a strategy to ensure the continuity of care and support for breastfeeding, following either home or facility deliveries.

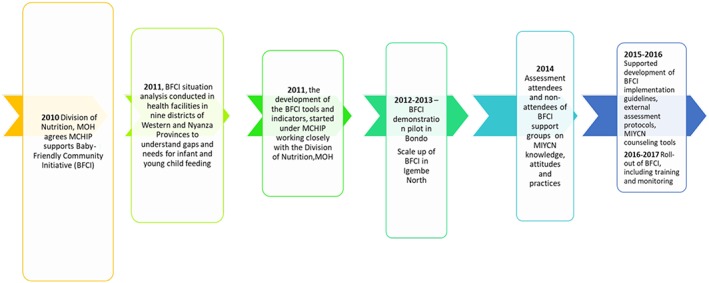

From 2010 to 2016, MCHIP and MCSP supported MOH in several key BFCI activities described in Figure 1, which included a demonstration pilot of BFCI in Bondo and Igembe North subcounties, which showed that attendees of BFCI community support groups were more likely than nonattendees to attend antenatal (ANC) > 3 times, deliver in health facilities, initiate breastfeeding within 1 hr of birth, not use prelacteal feeds, and resolve breastfeeding problems (Kimiywe, Mulindi, & Matiri, 2011; Thungu, Mulindi, Murage, & Israel‐Ballard, 2011). Subsequently, in 2012, the Government of Kenya included BFCI in the National Nutrition Action Plan and prioritized BFCI as a “high impact nutrition intervention” to reduce child malnutrition and mortality (Kenya MOH, 2012b). In 2014, the Kenya MOH and the Nutrition and Dietetics Unit in collaboration with Africa Population Health Research Center conducted a “case study” learning exchange visit between Kenya and Cambodia to understand the successes of the Cambodia BFCI programme, which informed on BFCI implementation in Kenya (Kenya MOH, 2014). In 2015–2016, MCSP supported the MOH in collaboration with UNICEF in the development of the first National BFCI Guidelines, which guided implementation for the entire country and harmonized monitoring of IYCF indicators through the BFCI monitoring tools. A BFCI training package, advocacy package, and tools for external assessment (i.e., for ascertaining whether a community is certified as baby friendly) were also developed.

Figure 1.

Timeline of BFCI implementation

In Kenya, subnational government teams (i.e., county and subcounty health management teams CHMT and SCHMT) were engaged in establishing community units, capacity building of health workers, and community health volunteers (CHVs), conducting supportive supervision, monitoring IYCF practices, and conducting self/internal assessments of communities as baby friendly.

3.2. BFCI Eight‐Point plan

The BFCI Eight‐Point plan is based on the principles of The Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding and is applied to all BFCI health services (Table 3). The Eight‐Point plan serves as the foundation of all BFCI training for county and subcounty managers and nutritionists, facility and community‐based health workers, agriculture/education officers, and community members.

Table 3.

BFCI Eight‐Point plan, Kenya

| 1. Have a written MIYCN policy summary statement that is routinely communicated to all health providers, community health volunteers, and the community members. |

| 2. Train all healthcare providers and community health volunteers, to equip them with the knowledge and skills necessary to implement the MIYCN policy. |

| 3. Promote optimal maternal nutrition among women and their families. |

| 4. Inform all pregnant women and lactating women and their families about the benefits of breastfeeding and risks of artificial feeding. |

| 5. Support mothers to initiate breastfeeding within 1 hr of birth and establish and maintain exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months. Address any breastfeeding problems. |

| 6. Encourage sustained breastfeeding beyond 6 months to 2 years or more, alongside the timely introduction of appropriate, adequate, and safe complementary foods while providing holistic care (physical, psychological, spiritual, and social) and stimulation of the child. |

| 7. Provide a welcoming and supportive environment for breastfeeding families. |

| 8. Promote collaboration between healthcare staff, CMSG, M2MSG, and the local community. Content has been developed for each step to guide the CHVs in counselling. |

3.3. Implementation experience of BFCI: Key findings

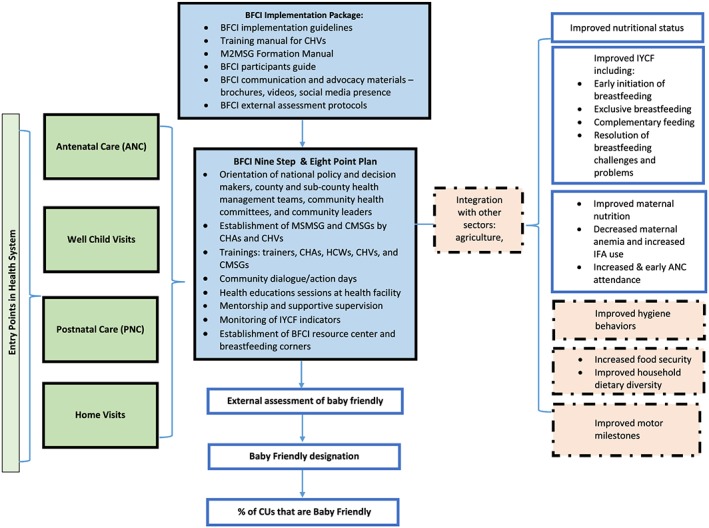

The implementation of BFCI was guided by the national BFCI guidelines, which includes the Eight‐Point plan and the Nine Steps (see Table 5). BFCI consists of several entry points in the health system (Figure 2), through routine contacts with mothers, community mothers support groups (CMSGs), and mother‐to‐mother support groups (M2MSGs). BFCI implementation built upon the MOH's Community Health Strategy and the country's health workforce, which included CHVs, selected by their communities who are trained to address health issues, and government‐employed community health agents (CHAs) and county and subcounty nutritionists, which are already part of the health system. (Table 4; Kenya MOH, 2014). CMSGs meetings were conducted every 2 months, led by CHAs, which discussed community needs around health and nutrition promotion, as well as conducting cooking demonstrations, hygiene education, and early child stimulation. The CHAs, CHVs, and county and subcounty nutritionists aided to identify members of the CMSG. Nutritionists are employed by the MOH and deployed to each county and subcounty. These nutritionists are tasked with implementation of nutrition interventions, including BFCI.

Table 5.

Nine steps for BFCI implementation

| Description of steps for BFCI | Results achieved in Kisumu, Migori, Turkana, Kitui, and Kericho counties |

|---|---|

| Step 1—National level policy and decision makers were oriented on BFCI | Conducted with 44 stakeholders (national level) |

| Step 2—Orientation of county and subcounty health management teams and key stakeholders (like ministries such as Ministry of Agriculture and Education) on BFCI | 151 county personnel oriented |

|

Step 3—Training of a cadre of master BFCI trainers (TOTs) on BFCI The MOH, with support from UNICEF, NHP Plus and Nutrition International (NI) organized five TOTs trainings from MOH, Ministry of Agriculture and partner organizations (such as MCSP, APHIA Plus, NHP Plus), at the national level (with 1–2 from each county). Master trainers were defined as national‐ and country‐level MOH personnel who had been actively training and implementing MIYCN activities. |

150 master trainers (nation‐wide), 11 master trainers for Kisumu/Migori |

|

Step 4—Training health workers and community health agents (CHAs) on BFCI BFCI was a 5‐day training of county and subcounty level CHAs and facility‐based health providers (maternal and child health nurse, nutritionist). Topics included maternal nutrition, exclusive breastfeeding, complementary feeding, BMS act, child growth and development, steps for establishing BFCI, and M&E. Ministry of Agriculture, Ministry of Education (i.e., early childhood development) officers also participated in the training. |

475 health workers and community health agents trained |

|

Step 5—Orientation of community health committee, primary health care facility committee, and other community leaders on BFCI Community influencers, such as community leaders, village chiefs and community health committees, play a crucial role in BFCI activities. Community members were oriented to the value of BFCI and identified participants for the community mother support group (CMSG) meetings. |

686 community members oriented |

|

Step 6—Mapping of households Most communities have community units and are mapped. In other communities that do not have community units, mapping is used to identify households with pregnant women and children less 1 year of age for targeting BFCI activities, in CHV catchment areas. In Kericho, Kitui, and Turkana counties, household mapping was needed, as CUs were not established. |

10 CUs mapped (Kericho, Kitui and Turkana counties only) |

|

Step 7—Establishment of community mother support groups Each community unit had a CMSG, which is a group of community members including a CHA, nutritionist, representatives from community health committees and CHVs, local village chiefs, lead mother, religious leaders, opinion leaders, and/or birth companions, who participate in BFCI activities. |

49 CMSGs established |

|

Step 8—Training of CHVs and community mother support group members A 5‐day training that focuses on the Eight‐Point plan (a summary of eight key points on MIYCN), which involves training CHVs and CMSGs on how to use national MOH MIYCN counselling cards. The CMSG then developed action plans that outlined the next plans and activities for implementation in BFCI. |

776 people trained: 550 community members and 226 CHVs |

|

Step 9—Establishment of mother‐to‐mother support groups (M2MSG) M2MSGs are comprised of small groups of 9 to 15 pregnant and lactating women, who meet monthly to learn about and discuss any maternal infant and young child nutrition issues, including addressing any breastfeeding problems, ways to resolve these problems, and how to maintain exclusive breastfeeding for the full 6 months, maternal nutrition (during prepregnancy, pregnancy, and lactation) and complementary feeding. Grandmothers as caregivers were also included in the groups if they had grandchildren below 2 years of age. |

200 M2MSG groups established |

Figure 2.

Baby‐Friendly Community Initiative (BFCI) conceptual framework

Table 4.

Definitions of health provider cadres who support BFCI, Kenya

|

• Community unit (CU): Lowest level of health care in the Kenyan health system providing PHC to a local population of 5,000 people. Comprises approximately 1,000 households and 5,000 people who live in the same geographical areas sharing resources and challenges. • Community health volunteer (CHV): Person in the community charged with facilitating formation of mother‐to‐mother support groups and participating in monthly targeted home visits. The home visits conducted by CHVs include counselling on MIYCN, care and stimulation, community mobilization on MIYCN, and facility referral for case of acute malnutrition. • Community health agents (CHA): Community health workers with certification in nursing or public health and employed by the MOH. They act as facilitators of dialogue at the community level and provide support to CHVs. The CHA acts as a direct supervisor and mentor for CHVs; establishes and supervises community mother support groups (CMSG) and functioning; acts as the point of contract between facilities and CMSGs; as well as coordinates self‐assessment for BFCI. • Nutritionist: One trained by education and experience in the science and practice of nutrition. |

CHVs conducted home visits and identified and invited pregnant and lactating mothers to participate in M2MSGs, usually spending about 30 min per household visit. M2MSGs provide a safe space where mothers discuss specific breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices, issues, and ways to resolve any challenges with their peers (Step 9).

Although drop out and turnover rates of CHVs could be an issue, only few CHVs left MCSP‐supported areas. Although no incentive was provided, per MOH BFCI guidelines, CHVs formed M2MSGs, and as fellow members of these support groups, CHVs were often held accountable at the community level. In addition, some CHVs started or were part of income generation activities within M2MSGs they had formed, which motivated their participation in BFCI activities. CHVs visited households on a monthly basis, according to the government community strategy. Households visited are estimated to equate the number of children less than 1 year of age in their designated catchment area, since mapping of households was already conducted (see Table 5).

Health workers also established breastfeeding corners, which are safe, private, and designated places where mothers can breastfeed in health facilities and include information on breastfeeding and provision of counselling and support, if needed.

Key achievements are the orientation of 44 national stakeholders and from MCSP and UNICEF areas, BFCI orientation for 685 community leaders, BFCI training for 475 health providers and 776 community members/volunteers, establishment of 249 mother to mother/community support groups, and the establishment of 11 breastfeeding corners in five counties. In MCSP‐supported areas, the project reached 3,065 children, where data were collected on children 0–12 months of age.

3.4. How were IYCF practices monitored in baby‐friendly communities and how were these data used for decision making?

CHVs collected IYCF indicator data (i.e., five BFCI monitoring indicators) on a monthly basis (from October 2016 to December 2017) in Kisumu (330 CHVs, 33 community units) and Migori (200 CHVs, 20 community units). CHVs conducted routine household visits from birth until 11 months on a monthly basis for a total of 12 contact points with the mother. One individual IYCF growth monitoring record was used per child to track the child from birth to 1 year of age. CHVs used the monthly data for decision making, as the data revealed which IYCF feeding practices were weak, if any, and provided the CHV with information to counsel the mother.

Each month following data collection on IYCF indicators, CHVs held a meeting with CHAs and subcounty nutritionist(s) to review data quality, discuss any concerns/questions, and consolidate data reports. During these meetings, the nutritionist and CHA were present to give guidance and mentor the CHVs, which improved quality of data and the CHVs capacity in collection and understanding of the IYCF indicators. CHAs and nutritionists verified collected data and aided in collating the data. The individual child monitoring forms were summarized into village reports by the CHA and MCH nurse or nutritionist. These village reports were compiled into a “facility report,” inclusive of all villages within the health facility catchment area by the CHA or facility nurse. All health facility reports were then summarized into subcounty reports by the subcounty nutritionist and the subcounty reports then consolidated by the county nutritionist.

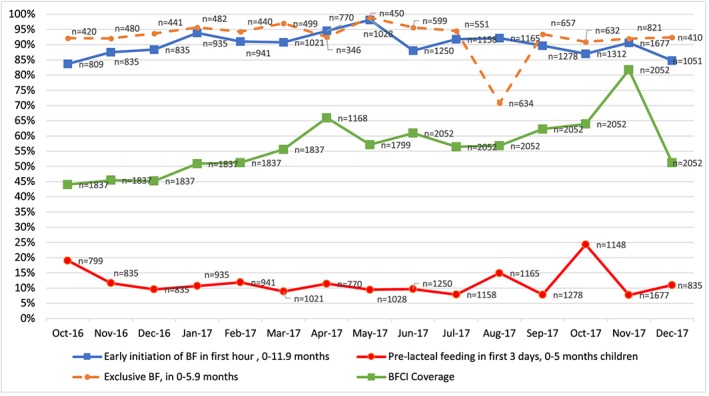

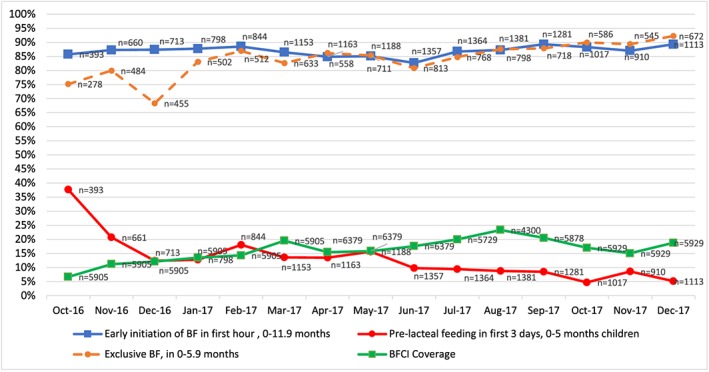

In Kisumu, BFCI coverage among children under one in implementing CUs was 60% in September 2017 (as MCSP ended implementation by the end of September); BFCI coverage declined to 50% by the end of December 2017, at 3 months postimplementation (Figure 3). In Migori, BFCI coverage sustained at approximately 20% throughout programme implementation (Figure 4). Countywide, >20% of all community units had BFCI activities in Kisumu, and in Migori, 10–20% of counties had BFCI activities, according to District Health Information Software 2 (DHIS2) compiled data (Figures 3 and 4).

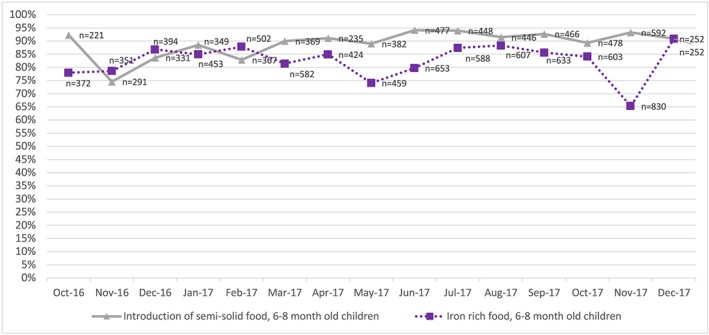

Figure 3.

Progress in breastfeeding indicators and BFCI coverage, by month, Kisumu County, October 2016 to December 2017, source: MOH BFCI monitoring data. Monthly sample sizes varied and children reached for BFCI monitoring were dependent on case load of CHVs, number of households visited, and amount of time spent per household according to number of health issues/challenges discussed. For Kisumu, additional CUs (8) were added in 2017, as BFCI was rolled out (see text for detail).

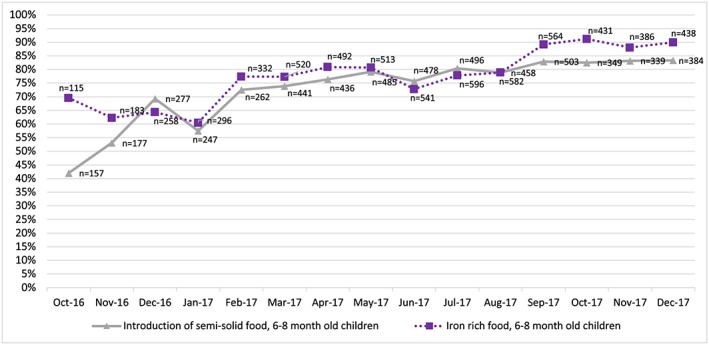

Figure 4.

Progress in breastfeeding indicators and BFCI coverage by month, Migori County, October 2016 to December 2017, source: MOH BFCI monitoring data

Regarding IYCF practices, early initiation and EBF slightly improved, with a dramatic decrease in prelacteal feeding from 19% to 11%, over the course of the programme in Kisumu (Figure 5). In Migori, early initiation (85.8% to 89.3%) and EBF increased (75.2% to 92.3%), with a large decline in prelacteal feeding (37.6% to 5.1%; Figure 6). Complementary feeding practices also improved markedly for consumption of iron rich complementary foods (69.6% to 90.0% in Migori, and 78% to 90.9% in Kisumu) and introduction of semisolid foods (42.0–83.3%—Migori). Performance of the five key BFCI indicators against their targets set for reaching children less than 1 year of age was assessed on a monthly basis, and key actions were taken following data review with CHAs and nutritionists. To minimize any provider bias in reporting these routine data, health providers understood data were not tied to performance review, and data could not be linked to individual CHVs (i.e., names), as data were anonymously rolled up.

Figure 5.

Progress in complementary feeding indicators by month, Kisumu County (October 2016–December 2017) source: MOH BFCI monitoring data

Figure 6.

Progress in complementary feeding indicators by month, Migori County (October 2016–December 2017) source: MOH BFCI monitoring data

With regards to BFCI coverage data, in Figure 3, large spikes in data in May 2017 reflected the additional CUs implementing BFCI during these time points (four at each time point), as BFCI expanded in Kisumu county with continued roll out of the intervention. In Figure 3, BFCI coverage experienced a decline in December 2017, as support from MCSP withdrew with project closure.

In addition to IYCF data, CHVs also used a breastfeeding checklist during household visits and M2MSG meetings to document and counsel on breastfeeding challenges women faced. Compilation of these data during integrated review meetings were reviewed, and CHVs counselled mothers on these challenges through routine health visits and via breastfeeding corners.

The common challenges to breastfeeding noted from CHVs, which were addressed through BFCI, were as follows:

Prelacteal feeding where infants were given herbal concoctions, glucose water, boiled water, and/or lemon water prior to establishing breastfeeding.

“Evil eye”—belief that when a child is observed breastfeeding, it can cause illness.

Incorrect positioning and attachment

Sustaining EBF for adolescents who return to school through breastmilk expression and proper storage

Belief that mothers' diet is not adequate to support breastfeeding

3.5. How did MCSP integrate nutrition and health contact points for BFCI?

During ANC, nurses counsel mothers in groups and also one‐to‐one at the health facility on maternal nutrition, EBF, expressing breastmilk, complementary feeding, and maternal anaemia (i.e., benefits of iron folic acid [IFA] supplementation, when to take IFA supplements, and how to manage temporary management of side effects), as part of the focused ANC package.

In addition, during home visits and M2MSGs, CHVs identified pregnant women in BFCI communities and urged them to start attending ANC early and continue follow‐up throughout pregnancy and postpartum. At childbirth, mothers who delivered in the facility initiated breastfeeding within 1 hr of delivery. Upon discharge from the maternity ward, mothers were instructed to take infants to the maternal and child health clinic (MCH) for child immunizations. Here, mothers were counselled on maintaining EBF, invited to participate in the M2MSG in her area, and introduced to the CHV covering her village who would conduct follow‐up home visits. During home visits, CHVs also reinforced messaging given during ANC for pregnant women, including starting ANC early, attendance of four ANC visits, maternal nutrition, malaria in pregnancy, the benefits of IFA and managing side effects, and the importance delivering in a health facility. The CHVs also taught mothers with children less 2 years of age about the importance of having kitchen gardens. Through their M2MSGs, cooking demonstrations were carried out to show mothers how to cook green leafy vegetables (i.e., not overcook), how to prepare and modify the consistency of animal source foods for children based on age, and the correct consistency for porridge.

3.6. How did BFCI integrate nutrition‐sensitive interventions, such as agriculture (kitchen gardens), WASH, and ECD?

BFCI provided a platform for integration of nutrition‐sensitive agriculture interventions. Agricultural extension workers were trained on food insecurity, food availability, and dietary diversity (i.e., increasing number of food groups consumed) through use of locally available, easy‐to‐grow crops (i.e., orange‐fleshed sweet potato) and green leafy vegetables, and fruits (i.e., passion fruit) from community gardens. Following this orientation, agricultural extension workers employed by the Ministry of Agriculture built the capacity of mothers and CHVs to plant, maintain and cultivate kitchen gardens, in addition to crops, protect/fence crops from animals, and care for crops in harsh climatic conditions.

Families were encouraged to sell surplus fruits and vegetables harvested from kitchen gardens and use these funds to purchase iron‐rich, animal source foods (i.e., eggs and chickens), to increase dietary diversity of both mother and child. Every member of the M2MSGs had a backyard “kitchen” garden in her household. This totalled the establishment of 2,000 backyard gardens and 26 community gardens in Kisumu and Migori. Education on preservation of vegetables through drying techniques and how to cook and reconstitute the dried vegetables was carried out and incorporated into cooking demonstrations (Kisumu only).

3.7. Early childhood development

Through BFCI, ECD teachers were engaged in provision of infant and young child nutrition and health messages through ECD centres (i.e., centres that provide preprimary school education for children 4–5 years of age, in every community unit) and community M2MSG meetings. ECD teachers were trained to screen for acute malnutrition while teaching parents how to play with their children using local toys. ECD teachers and CHVs worked together to create these local toys, such as a toy shaker (i.e., made from medicine bottle, pebbles, and stick) or dolls made from clothes or paper, which were part of the BFCI resource centres in community units.

3.8. Water, sanitation, and hygiene

BFCI also provided an opportunity to discuss key WASH messages from MIYCN counselling cards, including handwashing at critical times (i.e., after changing the baby's diapers, before eating or breast feeding, and before cooking), use of latrines and proper disposal of faeces, clean play areas away from animals, and food safety and hygiene (Kenya MOH, 2018b). Key messages on complementary feeding and good hygiene behaviours were reinforced at the health facility, through M2MSG and via home visits. BFCI leveraged other projects (i.e., Kenya Integrated Water and Sanitation KIWASH, AMREF) to promote key WASH practices and hygiene behaviours in the context of infrastructure (i.e., water treatment, latrine availability, and handwashing facilities [i.e., tippy taps]), which included linkages to community‐led total sanitation to reduce open defecation.

3.9. How was the baby‐friendly community certification process?

MCSP maintained regular follow‐ups, mentorship, supportive supervision, and continuous medical education at facility and community level. Of the CUs in Kisumu, 12 were ready for assessment as baby friendly. The community and subcounty teams conducted their own self‐assessments of the 12 CUs in Kisumu, and five CUs achieved a score of greater than 80%. The county MOH team then assessed the five CUs proposed by the subcounty, and three CUs were then evaluated by external assessors from national‐level MOH and UNICEF.

The external assessment team interviewed health workers in the health facility, CHVs, and sampled mothers within the communities randomly. Some health workers were unavailable for assessment due to the health workers' strike. None of the CUs externally assessed were certified as baby friendly and instead were given certificates of commitment to baby friendly. Because Migori and Kisumu were the first counties trained on BFCI and these national tools were applied for the first time, revisions to the tool were recommended by external evaluators prior to carrying out future external assessments. (e.g., the questions for mothers were similar to questions for health workers and required simplification). It was agreed that the tool would be revised to address identified gap(s) and the revised tool would be applied to a second round of external assessments of these BFCI CUs in 2019. In the future, these harmonized criteria will be applied to all CUs within the country.

4. DISCUSSION

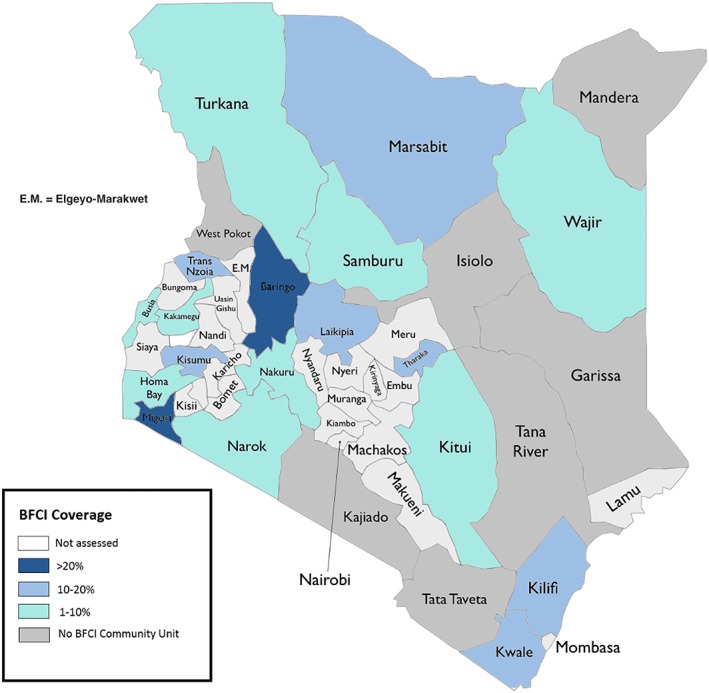

In this paper, we sought to document the process of BFCI implementation in selected implementing areas in Kenya, within the context of a USAID‐funded integrated health project and in collaboration with the MOH and UNICEF. Our findings reveal that coverage of BFCI was high and it surpassed the government target that 28% of all “community units (CUs) implementing BFCI” by 2016/2017 (Kenya MOH, 2012b) and most areas of Kenya (Figure 7). We observed improved early initiation of breastfeeding and EBF, with dramatic improvements in EBF in Migori, although not directly attributed to the programme, were notable during and after implementation for a 3‐month period. BFCI can be an effective platform to address breastfeeding challenges, such as prelacteal feeding, while also improving the introduction and quality of complementary foods given. BFCI successfully worked through active engagement of communities through multiple channels: 151 county personnel and 686 community were oriented on BFCI, 475 trained health workers provided counselling messages, 776 trained community members/volunteers aided with engagement and establishment of 249 support groups, which reached 3,065 children less than 12 months of age in MCSP‐supported areas. BFCI is also a unique platform for integration of IYCF messages into other health areas and associated activities, offering opportunities for counselling families around ECD and optimal hygiene behaviours as well as linkages to agriculture (i.e., community and household gardens).

Figure 7.

Coverage of BFCI, Kenya, January 2018, source: DHIS2

Recent evidence from Kenya and elsewhere reinforces the importance of the continuity of care for breastfeeding at the community level and corroborates/supports our findings. A recent cluster‐randomized pilot study in Baringo County, Kenya, to determine the feasibility and effectiveness of BFCI in 13 community units showed that 88% of children in the BFCI intervention group were exclusively breastfed for 6 months, whereas less than half (44%) were reported to exclusively breastfeed in the control group (P < 0.05; Kimiywe et al., 2017). Data also revealed significant improvements in early initiation of breastfeeding (89.5% intervention vs. 80.9% control), minimum dietary diversity, and significant reductions in suboptimal nutritional status among children, specifically underweight (both <6 months and >6 months of age) and wasting (children >6 months of age; Kimani‐Murage et al., 2015; Kimiywe et al., 2017). The study also revealed that the likelihood of attaining minimum dietary diversity (OR: 4.95, 95% CI [2.44, 10.03], P ≤ 0.001), minimum meal frequency (OR: 14.84, 95% CI [2.75, 79.9]), and minimum acceptable diet OR: 4.61, 95% CI [2.17, 9.78]) was statistically significantly higher for children in the intervention (BFCI group) compared with the control group (non‐BFCI group; Maingi, Kimiywe, & Iron‐Segev, 2018). Counselling of mothers by health workers, CHVs, and support groups (CMSGs and M2MSGs) was reported to enhance the women's skills and competencies in infant feeding, which are reflected in the study data. In addition, a cluster randomized controlled trial in Nairobi, Kenya, reported a large increases in EBF from 2% to 55% in 1,110 mother–infant pairs in urban slums in both intervention and control groups, which showed that nonblinded community health workers are instrumental for providing home‐based MIYCN counselling and breastfeeding support (Kimani‐Murage et al., 2017).

Several studies have also demonstrated that strong breastfeeding promotion and support at the community level through training of health providers who conduct group/home visits or home‐based peer counselling have shown gains in EBF (Kramer et al., 2008; Taddei, Westphal, Venancio, Bogus, & Souza, 2000), which corroborate our findings. Findings from a systematic review support these findings—as peer support for breastfeeding significantly decreased the risk of discontinuing EBF in comparison with the normal standard of care with no home visits (RR: 0.71, 95% CI [0.61, 0.82]; Sudfeld, Fawzi, & Lahariya, 2012). Evidence also points to a lack of benefits when community‐level implementation is weak, as demonstrated in a study on breastfeeding promotion efforts in hospitals, whereas 70% EBF was achieved in the maternity ward, by 10 days postdelivery, only 30% of newborn infants were exclusively breastfed (Coutinho, Cabral de Lira, Lima, & Ashworth, 2005). A recent systematic review (2016) on the BFHI and the Ten Steps of Successful Breastfeeding demonstrated that breastfeeding rates are higher when mothers and newborns have contact and experience with more of the Ten Steps of Successful Breastfeeding (Pérez‐Escamilla, Martinez, & Segura‐Pérez, 2016; WHO & UNICEF, 2009). In addition, a 2018 systematic review of randomized controlled trials examining EBF promotion relayed findings that BFHI has the greatest effect on EBF at 6 months, when community‐based postnatal visits were linked to facility‐based care and antenatal care (OR: 3.32; Kim, Park, Oh, Kim, & Ahn, 2018). This stresses the importance of early postpartum intervention for mothers, at the community level, who may experience challenges in the first week and are more likely to cease EBF prior to 6 months (Kim, Park, Oh, Kim, & Ahn, 2018; Kavle, LaCroix, Dau, & Engmann, 2017; Babakazo, Donnen, Akilimali, Ali, & Okitolonda, 2015). This underscores the need for steadfast breastfeeding support at the community level to maintain any gains in early initiation and EBF achieved in the initial hours or day following childbirth in facility‐based births (Pérez‐Escamilla et al., 2016).

Large declines in prelacteal feeding in both MCSP implementing areas were observed through routine monitoring data. Given the possibility that these data were impacted by social desirability bias, as the individuals providing the baby‐friendly services in the community also collected these data, we are unable to assert that these effects seen were directly due to the programme. However, these improvements in feeding practices were noted to occur during the same timeframe as roll out of programme interventions, as counselling and support were provided on breastfeeding challenges. Evidence from other country experiences reveals that breastfeeding promotion via expanded community support can be useful in resolving breastfeeding challenges. A randomized‐controlled trial in Belarus, Promotion of Breastfeeding Intervention Trial (PROBIT), rolled out an expanded BFHI with postnatal community support on maintaining lactation, promotion of EBF, and resolution of common breastfeeding problems, with intensive training for physicians, nurses, and midwives, to strengthen maternity ward services with well‐child visits up to 12 months postdelivery (Kramer et al., 2001). This expanded baby‐friendly model had a positive impact on EBF, with a significant decrease in the incidence of gastrointestinal infections at 1 year of age, a positive effect on children's IQ and academic performance at 6.5 years postpartum follow‐up (Kramer et al., 2001, 2008), and greater likelihood of mothers breastfeeding the subsequent infant for at least a 3‐month duration (Kramer et al., 2008), in intervention versus control hospitals.

In Kenya, community‐based breastfeeding counselling via BFCI was reinforced at the health facility level, through breastfeeding corners and baby‐friendly resource centres that provided additional information on breastfeeding for mothers. The link between health facility and local community for supporting MIYCN practices have demonstrated success in the past, through training of first‐line, primary health care providers.

Observational data from several studies revealed that training of primary health care providers on guiding mothers on breastfeeding positioning and breastfeeding concerns and problems at health facility level and through community group sessions/home visits with breastfeeding is impactful on EBF practices (Coutinho, de Lima, Lima, Ashworth, & Lira, 2005; da Silva, Albernaz, Mascarenhas, & Silveira, 2008; de Oliveira, Camacho, & Tedstone, 2003; Lutter et al., 1997). In Brazil, breastfeeding promotion in intervention hospitals that included receipt of information on breastfeeding between discharge and 30 days postpartum (after delivery), as well as between first and second visits, reported that EBF duration was 2 months longer in median duration (75 vs. 22 days, intervention vs. control group), with increased probability of breastfeeding (0.64 vs. 0.39 in the control group; Lutter et al., 1997). The success of the intervention likely was due to comprehensive support in most hospitals on the following topics: including lack of separation of mother and baby at childbirth, no prelacteal feeding, as well as information provided on handling of breastfeeding problems, including engorgement and sore nipples, and where mothers can “get help on breastfeeding,” which was higher in the intervention versus the control group.

4.1. Challenges and limitations

As shown in Table 6, one identified need is ensuring sufficient master trainers are available to meet the demand, alongside training and social and behaviour change counselling materials, to build nutrition competencies of health providers (De Lorme et al., 2018; Wainaina, Wanjohi, Wekesah, Woolhead, & Kimani‐Murage, 2018).

Table 6.

BFCI: Successes and challenges by national and subnational level

| National level | County level | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Successes | Challenges | Resolutions | Successes | Challenges | Resolutions |

|

• BFCI implementation by a large number of partners (NGOs and UNICEF) implementing MIYCN in Kenya • Brought attention to the need to revitalize BFHI—as mothers can also be referred from the BFCI communities to the hospitals for delivery • Built on existing community structures (i.e. community units) as a platform for BFCI implementation |

Insufficient links between community level efforts on breastfeeding (BFCI) and facility level (hospital‐ BFHI) due to inadequate implementation, knowledge gap and follow up | • There are efforts to revitalize BFHI once the new global guidelines are in place. In areas where BFCI is implemented, the link health facilities that qualify for BFHI also benefit in the additional support. Hospitals will also need to implement BFHI to ensure that regardless of the facility that the mother visits (in cases of referral), it is baby‐friendly | • Identification of BFCI champions in community units | Lack of community units[Link]: Establishing and training community units in semiarid and arid areas, where no community structures exist, can be expensive (need to budget for additional 5‐day training for CHVs on the community module then budget for another 6 days for the BFCI training) since a 5‐day training has to be done for the CHVs on the basic CU module before training on BFCI | When BFCI is implemented where there are no CUs, the first criteria are forming and training the CU on the basic CHV module. This would add to costs of BFCI implementation. Therefore, BFCI training started among CUs that were already established, trained, and functional apart from the arid and semiarid areas where mapping had first to be done. |

|

Development of national guidance and materials: • Development of national policies, strategies and guidelines which support BFCI – National nutrition action plan, MIYCN strategy, MIYCN policy •Development and roll‐out of a national MOH BFCI implementation package, inclusive of guidelines for implementation, advocacy tools, training modules and protocol for external assessment and certification of communities as “baby friendly,” with support from MCSP and UNICEF and partners • Development and roll‐out of MIYCN counselling cards for use by health workers and CHVs which included guidance for counselling for both nutrition specific and sensitive interventions, including WASH, kitchen garden and child stimulation) for first 1,000 days and up to 5 years of age |

No national MOH BFCI training curriculum tailored for community‐based providers (CHVs) | • A BFCI training manual for CHVs is under development and will be finalized by 2018. A simplified training package based on the 8‐point plan is being piloted, the results of which will inform on the training package for CHVs. MIYCN counselling card have been used to date, for the training of CHVs, while the package is under development. | • Support for BFCI by political administration and politicians at county level who mobilized the community for implementation |

Lack of allocation of funds for BFCI in county government health budget hindered sustainability of BFCI. |

Advocacy is ongoing to have budget allocated to the nutrition department. There has been political commitment in some community units at county level with the local administration and members of county assembly. This would result in allocation of budget for nutrition and specifically BFCI |

|

Integration with other sectors • ECD: Linkages with Ministry of Education ‐ECD section enabled incorporation of child stimulation • Agriculture: Linkages with agriculture offered an opportunity to improve complementary feeding practices, through increasing variety through establishment of demonstration gardens and development of recipes for complementary feeding • Income generation: The M2MSGs identified income generating activities on their own that increased cohesiveness and improved their livelihoods and variety of food |

Insufficient number of BFCI master trainers to meet the demand from counties for BFCI roll out, due to funding challenges | • The MOH with support from implementing partners will continue to build capacity in all 47 counties to build a pool of trainers. Prioritization in funding for training and follow‐up to ensure implementation and offer support need to be considered. | • Continued implementation through training, mentorship, supportive supervision and follow up with documentation and reporting of BFCI activities |

Lack of motivation of CHVs, who are unpaid workers within the ministry of health |

• Advocacy with the county government to provide monthly stipends supported by implementing partners and the health management teams at county level. Kitui is one of the counties where the advocacy efforts have borne fruit and the CHVs are paid monthly stipend by the county government. Others have committed but yet to start,e.g., Migori • CHVs supported by MCSP to register with the Ministry of Social Services, which is needed to be legally recognized as a group, to apply for and have access to loans and grants. Income‐generating activities are important for CHVs since they do not have any formal salary as volunteers. |

| Community ownership was critical to implementation to ensure that the community took lead in the process and would also ensure sustainability | Inadequate BFCI coverage for entire country | Both MOH and partners are scaling up implementation of BFCI. |

• Improvement in infant and young child feeding indicators through monitoring of five key BFCI indicators • Real‐time documentation is now available at community level for complementary feeding since CHVs capture data on the individual infant child and growth monitoring form, previously it was only available via survey data |

Insufficient number of MOH MIYCN counselling cards or counselling during M2MSG meetings and household visits by CHVs | The available MIYCN cards were distributed among the CHVs based on the proximity of their households to allow ease of sharing of counselling materials. |

| Engagement and use of community own resource personsb | — | — | • Utilized BFCI as platform encouraging early and frequent ANC attendance and hospital deliveries. | Government transfer of BFCI‐trained facility‐based health workers to other health facilities following training, which led to a gap in provider capacity to implement BFCI in a few facilities. Transfers continued throughout the course of implementation leading to a gap in BFCI capacity in some subcounties. | The newly replaced staff were mentored by subcounty teams to build their capacity on BFCI. |

| A mechanism to improve and monitor IYCF at community level | — | — | • Engagement of adolescent mothers through BFCI to improve EBF. The adolescents were recruited when pregnant and reached in their homes. They were supported to attend ANC through to the postpartum period. Their mothers were also reached to teach them on how to support their adolescents who were now mothers. They supported them to practice exclusive breastfeeding and would give the expressed breastmilk to the child when the adolescent was still in school and she would then continue with breastfeeding in the evening. |

Integration of agriculture with BFCI. Inadequate physical space around some health facilities for setting up “kitchen gardens.” A number of health facilities had kitchen gardens within the health facility while those without space identified and set up kitchen gardens in the community. Virtually each community unit had a demonstration garden while mothers had gardens in the community and individual gardens at home. |

The CHVs identified spaces within the community and started demonstration gardens that were used to teach mothers. |

| — | — | — | • Mothers enrolled in the M2MSGs were supported to start IGAs the IGAs improved attendance of the mothers during their meetings and also ensured sustainability of the groups |

Difficulty in follow‐up of mothers in M2MSGs/home visits due to, migration of mothers, residing in urban informal settlements and in arid/semiarid areas |

Some of the mothers ended up joining other BFCI groups in the areas where they had migrated to (if the areas were implementing BFCI). However, others were lost to follow up if they moved to non‐BFCI implementing areas |

| — | — | — | — | IGA groups are not linked to other support systems (i.e. government organizations that support start‐up of small businesses and gives funds to women groups. The only funds accessible is what is contributed by group members, which may be a small amount | The M2MSGs were encouraged to formally register with the Ministry of Social services ‐ to be recognized by the government so these M2MSGs would be able to write and apply for loans and grants to support start‐up of the IGA. Group members therefore set amounts that they would be contributing on a monthly basis. IGAs enhance cohesiveness and sustainability |

| — | — | — | — | Health workers strikes (*affected almost half the implementation year). Community activities proceeded without effect, yet public sector health facility activities were affected as health talks on the various BFCI scheduled topics could not be done, staff offering services at the health facility could not be assessed in terms of progress on BFCI, BFCI trainings in various counties were halted until after the strike | Continued mentoring and coaching of CHVs and referral of mothers to deliver in the private and faith‐based health facilities that were operational during the strike were conducted, as a temporary measure |

| — | — | — | — | Political unrest and instability affected attendance to community support group and mother to mother support group meetings, due to restriction in movement. | Meetings and activities continued in remote/rural areas which were little affected and follow up and meetings resumed in all other areas once stability was restored. |

The “community unit” as defined in this context comprises approximately 1,000 households or 5,000 people who live in the same geographical area, sharing resources and challenges. In most rural areas, such a unit would be a sublocation, the lowest administrative unit. The number of households in a community unit will determine the number of community health workers to be selected, so that 1 CHW serves approximately 20 household (MOH, 2007).

A CORP is … …….

In addition, although BFCI has experienced much success, key challenges remain for tracking implementation within the Kenya health information system. Regarding BFCI routine monitoring data, social desirability bias may be an issue. Although CHVs document these indicators and counsel women during monthly home visits using the data in the BFCI monitoring tools, CHVs also discuss a number of other health issues, such as WASH, family planning, whose data could also be affected. This raises the issue of the use of these community data for decision making, and in the future, the limitations of community data should be explored, as plans are underway to subsume BFCI monitoring tool indicators into DHIS2 in the future. Regarding providers providing counselling and documenting IYCF indicators at the same time, mothers are exposed to breastfeeding information from CHAs, facility‐based health providers, and in support groups, not only CHVs. To minimize bias, the CHA and nutritionist primarily rolled up the data and worked with CHVs on any data issues, and CHVs built relationships with mothers who view CHVs as “safe” to openly discuss issues and concerns regarding nutrition and health practices. Mothers were not under pressure from CHVs to provide a certain response.

4.2. Sustainability

In addition, regarding sustainability and declines in indicators and BFCI coverage with the close of MCSP (December 2017), the county government has not committed funds towards supporting BFCI activities, and therefore, some CHVs were not motivated to continue with BFCI implementation. Whereas CUs continued implementation, coverage waned due to inadequate support. In the future, there are several ways BFCI can be better sustained. First, BFCI reporting should be integrated in the DHIS2 and CHV routine reporting tools and registers to be further institutionalized. Second, CHVs could be provided small incentives to stimulate motivation. Third, identification of key champions, that is, health workers, CHAs, and nutritionists that have a passion/commitment for BFCI, has been a part of the success experienced to date.

4.3. Strengthening links between health facilities and communities through BFCI and BFHI

A key weakness is the link between hospitals and communities to protect, promote, and support breastfeeding, which require strengthening (UNICEF & WHO, 2018). Whereas BFCI has been key for implementing the 10th step with linkages both to community and primary health care, BFHI has stalled for several years in the country (UNICEF & WHO, 2017).

In 2017, the MOH through Nutrition and Dietetics Unit revitalized BFHI by conducting a training for 25 participants as trainers and the development of centres of excellence for BFHI, which are health facilities that have been assessed and certified as baby friendly. The MOH with UNICEF is working to build the capacity and coordination of BFHI from the national to the hospital level, and the government is committing resources for BFHI, which include budgeting for BFHI, resource mobilization, and revising and putting BFHI back on the agenda. In addition, to maintain sustainability for BFCI, preservice training through universities and colleges, including medical schools and nursing schools, with continuous medical education, is crucial for baby‐friendly efforts for BFCI and BFHI. This can aid with building capacity of newly employed staff and human resource challenges, including turnover/transfer from BFCI‐trained facilities to other health facilities (UNICEF & WHO, 2017). Finally, tracking and monitoring the International Code of Breastmilk Substitutes is critically important, with the roll out of Network for Global Monitoring and Support for Implementation of the International Code of Marketing of Breast‐milk Substitutes (NetCode) and NetCode Toolkit for periodic monitoring of the Code (WHO, 1981; UNICEF & WHO, 2018; WHO & UNICEF, 2017). Kenya is one of the UN member states that is currently implementing the NetCode package (WHO & UNICEF, 2017).

5. CONCLUSION

5.1. What were programmatic implications and main lessons learned on BFCI?

Important lessons were learned during the BCFI implementation process within the Kenya health system. First, systematic capacity building of implementers, with buy‐in at the national level, at the beginning, as well as identifying, motivating, and working with champions were instrumental in keeping BFCI on the agenda. Second, mentorship of health providers and CHVs by trainers played a key role in the initial steps of BFCI. Third, implementation of BFCI as an integrated model, through working with other programs/sectors, can motivate early and frequent attendance at ANC, encourage attendance to health facility for childbirth and may improve immunization.

Fourth, social mobilization efforts through identifying, sensitizing, and engaging existing members of community support systems to promote BFCI endeavours and establish community support groups (i.e., ECD teachers, traditional birth companions, agricultural extension workers, local community, and religious leaders) were key. Fifth, supportive supervision and continuous mentorship by the county and subcounty health management teams is necessary to ensure implementation of BFCI is carried out with the quality, frequency, and intensity needed to achieve adequate coverage.

5.2. What should be considered in scaling up BFCI?

Advocacy for additional government resources is needed to support scale‐up of BFCI, alongside an assessment of the scaling‐up environment for BFCI in the context of BFHI, using the Becoming Baby Friendly Index at subnational levels (Perez‐Escamilla et al., 2017; Aryeetey & Dykes, 2018). For BFCI scale‐up to be successful, stipends for CHVs, distribution of key materials and tools (i.e., MIYCN counselling cards, and BFCI monitoring tools) as well as development of a formal training curriculum for community‐based providers (CHVs) are needed. Since its inception, BFCI reporting has been parallel to other routine community reporting. With increased coverage and implementation of BFCI across Kenya, in the future, BFCI indicators should be integrated into the routine community reporting tools and DHIS2 for sustainability. Future efforts should link implementation of BFCI and BFHI, per recently released WHO Guidelines (WHO, 2018), to ensure the continuum of care from facility to community level for breastfeeding counselling and support.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. USAID provided review of the manuscript, and authors had intellectual freedom to include feedback, as needed.

CONTRIBUTIONS

JAK and BA conceptualized and jointly led the writing of the paper. LK, RM, FO, SS, and CG were involved in writing of the paper. All authors were involved in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

FUNDING

This publication is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the US Agency for International Development (USAID), under the terms of cooperative agreement number AID‐OAA‐A‐14‐00028. The contents are the responsibility of the MCSP and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge Evelyn Matiri for her support on the BFCI implementation process during two USAID‐funded projects, inclusive of Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program (MCHIP) and the initial start‐up of USAID's Maternal and Child Survival Program (MCSP).

Kavle JA, Ahoya B, Kiige L, et al. Baby‐Friendly Community Initiative—From national guidelines to implementation: A multisectoral platform for improving infant and young child feeding practices and integrated health services. Matern Child Nutr. 2019;15(S1):e12747 10.1111/mcn.12747

Footnotes

In Kisumu county, MCSP supported BFCI implementation in Nyatike, Suna East, Suna West, Kuria West, Rongo, Nyakatch, Seme, Muhoroni, Nyando, Kisumu West (KW), and Kisumu East (KE) subcounties (KW and KE commenced in April–May 2017), whereas UNICEF also supported Kisumu East and West subcounties.

In Migori county, MCSP supported BFCI implementation in Nyatike, Suna East, Suna West, Kuria West, Rongo, Nyakatch, Seme, Muhoroni, Nyando, Kisumu West (KW), and Kisumu East (KE) subcounties (KW and KE commenced in April–May 2017), whereas UNICEF also supported Kisumu East and West subcounties.

BFCI was implemented in Ainamoi, Kipkelion East, and Belgut subcounties.

BFCI was implemented in Turkana South, Turkana East, Turkana North, Turkana West, Turkana Central, Loima, Kibish.

BFCI was implemented in Mwingi central and Mwingi North subcounties.

Formerly known as Community Health Extension Workers.

District Health Information Software 2 (DHIS2) is an open source, web‐based health management information system platform, which is used to aggregate health information system data at the subnational and the national level

Teachers had Form 4 education with 1‐year training in ECD.

REFERENCES

- African Population and Health Research Center (2014). Baby Friendly Community Initiative: A desk review of existing practices. Nairobi: African Population and Health Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Aryeetey, R. , & Dykes, F. (2018). Global implications of the new WHO and UNICEF implementation guidance on the revised Baby‐Friendly Hospital Initiative. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 14(3), e12637 10.1111/mcn.12637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babakazo, P. , Donnen, P. , Akilimali, P. , Ali, N. , & Okitolonda, E. (2015). Predictors of discontinuing exclusive breastfeeding before six months among mothers in Kinshasa: A prospective study. International Breastfeeding Journal, 10(19). 10.1186/s13006-015-0044-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettinelli, M. , Chapin, E. , & Cattaneo, A. (2012). Establishing the Baby‐Friendly Community Initiative in Italy: Development, strategy, and implementation. Journal of Human Lactation, 28(3), 297–303. 10.1177/0890334412447994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho, S. , Cabral de Lira, P. , Lima, M. , & Ashworth, A. (2005). Comparison of the effect of two systems for the promotion of exclusive breastfeeding. Lancet, 366(9491), 1094–1100. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67421-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho, S. , de Lima, M. , Lima, C. , Ashworth, A. , & Lira, P. (2005). The impact of training based on the Baby‐Friendly Hospital Initiative on breastfeeding practices in the Northeast of Brazil. Jornal de Pediatria, 81(6), 471–477. 10.2223/JPED.1422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, M. , Albernaz, E. , Mascarenhas, M. , & da Silveira, R. (2008). Influence of breastfeeding support on the exclusive breastfeeding of babies in the first month of life and born in the city of Pelotas, State of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Saude Materno Infantil, 8(3), 275–284, 10.1590/S1519-38292008000300006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Lorme, A. , Gavenus, E. R. , Salmen, C. , Benard, G. , Mattah, B. , Bukusi, E. , & Fiorella, K. (2018, 197). Nourishing networks: A social ecological analysis of a network intervention for improving household nutrition in western Kenya. Social Science & Medicine, 95–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira, M. , Camacho, L. , & Tedstone, A. (2003). A method for the evaluation of primary health care units' practice in the promotion, protection, and support of breastfeeding: Results from the state of Rio de Janeiro. Journal of Human Lactation, 19(4), 365–373. 10.1177/0890334403258138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Development Initiatives (2017). Global nutrition report 2017: Nourishing the SDGs. Bristol: Development Initiatives. [Google Scholar]

- Global Breastfeeding Collective, UNICEF, & WHO (2017). Global Breastfeeding Scorecard, 2017: Tracking progress for breastfeeding policies and programmes. New York: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, K. (2016). Breastfeeding: A smart investment in people and in economies. Lancet, 387(10017), 416 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00012-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavle, J. , LaCroix, E. , Dau, H. , & Engmann, C. (2017). Addressing barriers to exclusive breast‐feeding in low‐ and middle‐income countries: A systematic review and programmatic implications. Public Health Nutrition, 20(17), 3120–3134. 10.1017/S1368980017002531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenya Central Bureau of Statistics, Kenya Ministry of Health, & ORC Macro . (2004). Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2003. Calverton: CBS, MOH, and ORC Macro. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya MOH (2005). Reversing the trends: The second National Health Sector Strategic Plan of Kenya—NHSSP 2005–2010. Nairobi: Kenya Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya MOH (2011). National Food and Security Policy. Nairobi: Kenya Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya MOH (2012a). Baby Friendly Community Initiative: Monitoring tool and assessment protocol—Orientation package for health workers and community health workers. Nairobi: Kenya Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya MOH (2012b). National Nutrition Action Plan 2012–2017. Nairobi: Kenya Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya MOH (2012c). National Strategy For Maternal, Infant and Young Child Nutrition 2012–2017. Nairobi: Kenya Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya MOH (2013). National Maternal, Infant and Young Child Nutrition: Policy Guidelines. Nairobi: Kenya Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya MOH (2014). Strategy for Community Health 2014–2019. Nairobi: Kenya Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya MOH (2016). Baby Friendly Community Initiative Implementation Guidelines. 72. Nairobi: Kenya Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya MOH (2018a). A guide to complementary feeding 6 to 23 months. Nairobi: Kenya Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya MOH (2018b). Kenya National Maternal, Infant and Young Child Nutrition Counselling Cards. Nairobi: Kenya Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS), & ICF Macro (2010). Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2008–09. Calverton: KNBS and ICF Macro. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, Kenya Ministry of Health, National AIDS Control Council/Kenya, Kenya Medical Research Institute, National Council for Population and Development/Kenya, a . (2014). Kenya Demographic and Health Survey Key Indicators 2014. Calverton: Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of Health/Kenya, National AIDS Control Council/Kenya, Kenya Medical Research Institute, National Council for Population and Development/Kenya, and ICF International. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya National Council for Population and Development Central Bureau of Statistics (Office of the Vice President and Ministry of Planning and National Development) [Kenya], A . (1999). Kenya demographic and health survey 1998. Calverton: NDPD, CBS, and MI. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. , Park, S. , Oh, J. , Kim, J. , & Ahn, S. (2018). Interventions promoting exclusive breastfeeding up to six months after birth: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 80, 94–105. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimani‐Murage, E. W. , Griffiths, P. L. , Wekesah, F. M. , Wanjohi, M. , Muhia, N. , Muriuki, P. , … Madise, N. J. (2017). Effectiveness of home‐based nutritional counselling and support on exclusive breastfeeding in urban poor settings in Nairobi: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Globalization and Health, 13(1), 1–16. 10.1186/s12992-017-0314-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimani‐Murage, E. W. , Kimiywe, J. , Kabue, M. , Wekesah, F. , Matiri, E. , Muhia, N. , … McGarvey, S. T. (2015). Feasibility and effectiveness of the baby friendly community initiative in rural Kenya: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 16(1), 1–13. 10.1186/s13063-015-0935-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimiywe, J. , Kimani‐Murage, E. , Wekesah, F. , Muriuki, P. , Samburu, B. , Wanjohi, M. , … McGarvey, S. (2017). The Baby Friendly Community Initiative—A pilot study in Koibatek, Baringo County, Kenya. Nairobi: African Population Health Research Center and Ministry of Health, Kenya, and Kenyatta University. [Google Scholar]

- Kimiywe, J. , Mulindi, R. , & Matiri, E . (2011). Baby Friendly Community Initiative: Understanding the role of the community in promoting maternal, infant and young child nutrition among caregivers in Bondo District. Nairobi: Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, M. , Aboud, F. , Mironova, E. , Vanilovich, I. , Platt, R. , Matush, L. , … Promotion of Breastfeeding Intervention Trial (PROBIT) Study Group (2008). Breastfeeding and child cognitive development: New evidence from a large randomized Trial for the Promotion of Breastfeeding Intervention Trial (PROBIT) study group. Archives of General Psychiatry, 65(5), 578–584. 10.1001/archpsyc.65.5.578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, M. , Chalmers, B. , Hodnett, E. , Sevkovskaya, Z. , Dzikovich, I. , Shapiro, S. , … PROBIT Study Group (Promotion of Breastfeeding Intervention Trial) (2001). Promotion of Breastfeeding Intervention Trial (PROBIT): A randomized trial in the Republic of Belarus. Journal of the American Medical Association, 285, 413–420. 10.1001/jama.285.4.413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, M. , Fombonne, E. , Igumnov, S. , Vanilovich, I. , Matush, L. , Mironova, E. , … Platt, R. (2008). Effects of prolonged and exclusive breastfeeding on child behavior and maternal adjustment: Evidence from a large, Randomized Trial. American Academy of Pediatrics, 121(3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutter, C. , Perez‐Escamilla, R. , Segall, A. , Sanghvi, T. , Teruya, K. , & Wickham, C. (1997). The effectiveness of a hospital‐based program to promote exclusive breast‐feeding among low‐income women in Brazil. American Journal of Public Health, 87(4), 659–663. 10.2105/AJPH.87.4.659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maingi, M. , Kimiywe, J. , & Iron‐Segev, S. (2018). Effectiveness of Baby Friendly Community Initiative (BFCI) on complementary feeding in Koibatek, Kenya: A randomized control study. BMC Public Health, 18 10.1186/s12889-018-5519-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCSP . (2018). USAID's Flagship Maternal and Child Survival Program. Retrieved from https://www.mcsprogram.org/

- Ministry for Public Health and Sanitation (2012). The Breast Milk Substitutes (Regulation and Control) Act No. 34 of 2012. Nairobi: Kenya Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]