Abstract

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of anti-PD1 therapy (nivolumab) in advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) in a clinical setting. Between March 2013 and January 2018, 33 patients with RCC (27 men and 6 women) were treated with nivolumab. Before anti-PD1 treatment, 12, 9 and 12 patients received one, two, and three or more therapies, respectively. Objective response, survival rate, and clinical adverse events were evaluated by the revised RECIST criteria (version 1.1). The median patient age was 68 years (range: 37–79). In total, 14 (42%) patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) of 0 while 17 (52%) and two (6%) had an ECOG PS of 1 and 2 or higher, respectively. One (3%), 24 (73%) and eight (24%) were classified as having favorable, intermediate, and poor risk, respectively. The median follow-up duration after nivolumab initiation was 26 months (range: 1–131). The median progression-free and overall survival were 10.3 months and 45.9 months, respectively. Nivolumab was associated with a disease control rate of 58%, with an objective response of 24% (complete response, 1; partial response, 7; stable disease, 11; progressive disease, 10; not assessed, 4). A total of 15 (46%) patients experienced adverse events, of which six were severe (grade 3 or more) and 10 were immunotherapy-related. This study examined the initial experience of nivolumab administration in Japanese patients with advanced RCC. Our results suggest that nivolumab can achieve acceptable outcomes in a real clinical setting, with outcomes that are comparable to those of clinical trials.

Keywords: renal cell carcinoma, nivolumab, prognosis, adverse events, initial case

Introduction

An estimated 20–30% of all patients with renal cell carcinoma (RCC) have metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis. Although multiple guidelines, including those of The National Comprehensive Cancer Network and the European Association of Urology, recommend first-line vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-targeted therapy for patients with clear cell metastatic RCC (mRCC) (1,2), the response to first-line VEGF-targeted therapy is generally not durable, and most patients require additional therapy (3). The role of immune checkpoint inhibitors is increasingly of interest in cancer immunotherapeutics, and nivolumab, a novel anti-PD1 antibody, has been increasingly used in patients with several types of cancer. Although nivolumab has been most frequently used for melanoma, it is currently under evaluation for a number of other cancers. In terms of overall survival (OS), nivolumab has been shown to be superior to everolimus in a phase III randomized trial, and thus offers promising potential for use in patients with mRCC after treatment failure. However, unfamiliar toxicities have also been recognized with nivolumab use, such as immune-related adverse events (irAEs) (4). There has been no initial report about mRCC treated by nivolumab in the Japanese population yet.

The present study aimed to analyze the clinical outcomes and toxicities related to nivolumab in Japanese patients with mRCC in a real-world setting.

Patients and methods

Eligibility criteria

The present study included patients who were diagnosed with advanced RCC and treated with nivolumab from two institutes between March 2013 and January 2018. All patients with histologically-proven mRCC, regardless of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS), were eligible for inclusion. All patients received at least two cycles of nivolumab and were assessed for treatment efficacy and toxicity. This study was approved by both institutional review boards, The Research Ethics board of Akita University Hospital (approval no. 1993) and Japanese Red Cross Akita Hospital, and all procedures were performed in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Treatment and follow-up examinations

Complete medical history, physical examination, ECOG PS, CBC with differential and platelet count, biochemical profile (including electrolytes, renal and hepatic function, coagulation, pancreatic amylase, and lipase), urinalyses, and chest radiography were recorded for all patients before treatment was started; these tests were repeated during therapy according to the attending physician's decision. Toxicity was graded using the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria version 2.0. Tumors were measured by computed tomography scans within 4 weeks prior to starting nivolumab. After starting the drug, the assessment interval was scheduled for individual patients by attending physicians. We defined that patients experienced tumor enlargement or appearance of a new lesion after initiating nivolumab and intolerable adverse event (AE)as ‘nivolumab failure’. Tumor response was evaluated using the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) guidelines v.1.1.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total 33 patients who were diagnosed with advanced RCC and eligible for the present study were enrolled. Patients' baseline characteristics are summarized in Table I. All patients were Japanese, and the cohort included 27 (81.8%) men and six (18.2%) women. The median patient age was 68 (range: 37–79) years. Thirty-two (97.0%) patients underwent radical nephrectomy before starting systemic therapies. Twenty-nine (87.9%) patients had clear cell histology, two (6.1%) patients had Xp11.2 translocation, and one patient each (3.0%) had papillary, chromophobe, and sarcomatoid histology. Twelve (36.4%) patients were administered nivolumab as second-line systemic therapy, nine (27.3%) as third-line therapy, and 12 (36.4%) as fourth-line or later therapy. Fourteen (42.4%) patients had an ECOG PS of 0, 17 (51.5%) patients had an ECOG PS of 1, and two (6.1%) patients had an ECOG PS of 2 or higher. Using the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) risk classification system, one (3.0%) patient was classified as being at favorable risk, 24 (72.7%) patients were classified as being at intermediate risk, and eight (24.2%) patients were classified as being at poor risk. Twelve (36.4%) patients had one metastatic site, 11 (33%) patients had two, and 10 (30%) patients had three or more.

Table I.

Patient characteristics.

| Characteristic | Result |

|---|---|

| Total patient number | 33 |

| Age, median year (range) | 68 (37–79) |

| Sex, male:Female | 27:6 |

| Nephrectomy, yes:No | 32:1 |

| Histology | |

| Clear cell | 29 |

| Xp11.2 translocation | 2 |

| Papillary | 1 |

| Chromophobe | 1 |

| Sarcomatoid | 1 |

| MSKCC risk classification, Favorable:Intermediate:Poor | |

| At the beginning of systemic therapy | 4:22:7 |

| At the starting of nivolumab | 1:24:8 |

| Metastatic site, 1:2:≥3 | 12:11:10 |

| ECOG PS, 0:1:≥2 | |

| At the beginning of systemic therapy | 24:8:1 |

| At the starting of nivolumab | 14:17:2 |

| Number of prior therapy, 1:2:≥3 | 12:9:12 |

MSKCC, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PS, performance status.

Antitumor effect

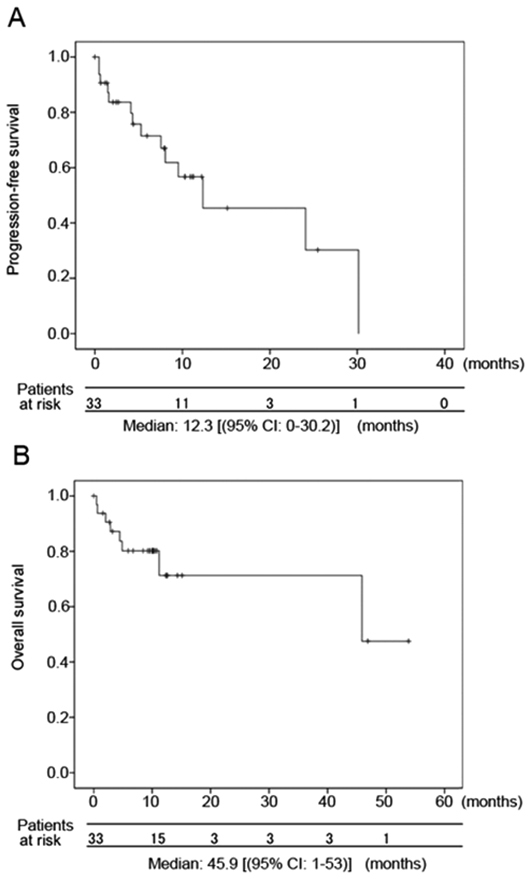

An objective response (OR) was found in eight (24.2%) patients (Table II). The median progression-free survival was 12.3 months (range: 0–30.2), and the OS was 45.9 months (range: 0–53.9) (Fig. 1). These survival rates might be equivalent to the median PFS 4.6 months and OS 25.0 months in CheckMate-025 trial (4). The median time to best response after starting nivolumab was 3.2 months (range: 0.5–5.7 months). The median duration after achieving best response was 2.3 months (range: 2.0–26.6 months) (Table II).

Table II.

Results of nivolumab management.

| Factor | Result |

|---|---|

| Dose, mg/kg | 3 |

| Median (range) | 11 (3–65) |

| Duration, median month (range) | 23 (1–131) |

| Current status | |

| Continue | 9 |

| Stop | 19 |

| Pending | 4 |

| Unknown | 1 |

| Best response | |

| CR | 1 |

| PR | 7 |

| SD | 11 |

| PD | 10 |

| Not assessed | 4 |

| Objective response rate, % | 24.2 |

| Time to best response, median month (range) | 3.2 (0.5–5.7) |

| Duration of best response, median month (range) | 2.3 (2.0–26.6) |

CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves for progression-free survival and OS Kaplan-Meier curves for (A) progression-free survival and (B) OS. OS, overall survival.

Adverse events

At the data cutoff, 15 patients (45.5%) had experienced an AE (Table III). Six patients (18.2%) discontinued nivolumab treatment because of AEs. The most common AE was renal dysfunction (n=3). Grade 3 or higher AEs presented in six (18.2%) patients. IrAEs (any grade) included two cases each of interstitial pneumonia, myasthenia gravis, liver dysfunction, and hypothyroidism, and one case each of hypopituitarism and organizing pneumonia. Corticosteroid was administered as primary treatment for all irAEs, except for one patient with myasthenia gravis. Only one irAE, a case of hypopituitarism, was not resolved, and the patient has since required continuous steroid and thyroid hormone supplemental therapy. There was no relationship between irAE development and clinical response. Five patients died within 6 months after initiating nivolumab treatment. Of these five, three patients were already administered multiple therapies (at least four) and had advanced RCC before starting nivolumab treatment, and two patients had an ECOG PS of 2 or worse at the time of starting nivolumab.

Table III.

Treatment-related adverse events.

| Factor | Result |

|---|---|

| Patient number | 33 |

| Number of patients with AEs | 15 (45.5%) |

| Cause of discontinuation | |

| PD | 13 |

| AE | 6 |

| Detail of discontinuation | |

| G3 or more | 6 |

| Myasthenia gravis | 2 |

| Liver dysfunction | 1 |

| General edema | 1 |

| Hypopituitalism | 1 |

| Heart failure | 1 |

| General AE, any grade | |

| Renal dysfunction | 3 |

| Pleural effusion | 2 |

| Heart failure | 2 |

| General edema | 1 |

| General fatigue | 1 |

| Hyper Kalemia | 1 |

| Rash | 1 |

| irAE, any grade | |

| Myasthenia gravis | 2 |

| Interstitial pneumonia | 2 |

| Liver dysfunction | 2 |

| Hypothyroidism | 2 |

| Hypopituitarism | 1 |

| Organizing pneumonia | 1 |

PD, progressive disease; AE, adverse event; G, grade; ir, immune-related.

Treatments after nivolumab failure

Thirteen patients were administered further treatment after nivolumab failure during the period of this investigation. Of these, all patients received VEGF receptor inhibitor, with five receiving axitinib, four receiving sunitinib, three receiving pazopanib, and one receiving sorafenib (Table IV). Only three patients (OR rate: 20.8%) showed partial response (PR), but six patients achieved stable disease (SD) even after nivolumab failure, indicating some clinical benefit.

Table IV.

Treatment after nivolumab failure.

| Status | Patient number | Best response |

|---|---|---|

| Dead | 3 | |

| Axitinib | 5 | PR 2, SD 2, PD 1 |

| Sunitinib | 4 | PR 1, SD 1, PD 2 |

| Pazopanib | 3 | SD 2, PD1 |

| Sorafenib | 1 | SD 1 |

| Treatment pending | 4 | SD 2, PD 1, unknown 1 |

| Move to other hospital | 1 | Unknown 1 |

PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease.

Discussion

This study found that nivolumab was relatively effective and showed acceptable results in Japanese patients with mRCC. The OR rate and survival rate in our cohort were comparable to those of previous clinical trials (4), despite the fact that our cohort included patients with worse PS, MSKCC-determined poor risk, and non-clear cell histology. Nine patients had SD at the time of this study, and four patients showed durable responses for over 12 months; these findings indicate the potential utility of immune checkpoint blockade for the treatment of patients with mRCC (5). This relatively better outcome than we expected before nivolumab launched despite unfavorable patient clinical backgrounds could support the assertion that immune checkpoint inhibitors are a revolutionary therapy (6).

Research efforts to determine a predictive marker, such as PD-L1 positivity (4), mutation burden (7), and profile of immune-related genes (8), are currently ongoing. Most previous studies have focused on identifying exceptional responders to immune checkpoint inhibition; however, even patients with lower expression of PD-L1 showed an OR rate of over 20% in the CheckMate-025 trial (4). Therefore, immunohistological evaluation of PD-L1 expression, would not change our clinical decision, because a substantial number of patients without PD-L1 expression can still benefit from nivolumab therapy.

The timing of nivolumab administration may be another important consideration for appropriate clinical decisions. Although our sample size was small, and we could not assess statistical significance, we saw a trend between worse survival and both poor ECOG PS and multiple prior therapies in our cohort. This suggests that the maximum benefit from nivolumab is likely to occur early in the sequential course of multiple treatments and prior to cancer advancement or decline in a patient's general status. Early exposure to immune checkpoint inhibitors can be reinforced by the possibility of late immune response with anti-tumor effect (9). Although in this study there were no patients who met the criteria for ‘pseudo-progression’ (10) with subsequent response, one patient with SD did eventually develop PR. Determining the appropriate time to examine the ‘delayed response’ (11) of an immune-related anti-tumor effect can be difficult, which emphasizes the importance of earlier introduction and good PS in nivolumab treatment (10).

Although immune checkpoint-blocking antibodies are effective in many types of cancers, irAEs may be unavoidable (12). In addition to relatively common AEs, such as interstitial pneumonia, colitis, hepatitis, kidney insufficiency, and hypo-endocrinology, uncommon AEs have also been reported, such as cardiotoxicity (13), type 1 diabetes (14), and myasthenia gravis (15). In this study, several irAEs were observed in response to nivolumab despite the small size of the patient cohort. In the important phase III trial of nivolumab (4), grade 3–4 toxicities were reported at a rate of 21%. The rate of grade 3–4 toxicities observed in this study (18.2%) was similar, despite the short observation period. Importantly, all grade 3–4 irAEs that occurred in patients in this study, with the exception of hypopituitarism, resolved with prompt initiation of corticosteroid administration followed by a slow steroid taper. This is similar to what has been described in the management of irAEs in other cancers, and underscores the necessity for vigilance by the attending physician concerning these potential events (16). Our results indicate that nivolumab might be a relatively safe drug for the treatment of mRCC in real clinical practice.

The proper endpoint for nivolumab treatment has been controversial (17,18). In several patients in our study, no tumor progression was observed after cessation of nivolumab treatment. Based on these cases, we suggest that nivolumab treatment not be stopped prematurely, even after an initial therapeutic effect is achieved. However, it is not clear from our study whether prolongation of treatment would further improve clinical outcome. It has been reported that long-term application of anti-PD1 antibody can also cause drug resistance (19). Hence, the duration of nivolumab application for mRCC treatment needs to be further studied.

Several limitations of this study should be noted, including the retrospective nature and limited number of patients. However, our results show promising relevance for nivolumab in clinical practice and warrant further research of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in advanced RCC.

The present study demonstrated the safety and acceptable outcomes of anti-PD1 therapy with nivolumab in patients with advanced RCC. Although nivolumab precipitated unique AEs, these were treated promptly and all but one were reversible. Our findings suggest that nivolumab is a reasonable therapeutic option for patients with mRCC after multiple lines of treatment. Future prospective studies with larger sample sizes are required to better understand the appropriate indications of nivolumab for patients with RCC.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like thank Ms Yoko Mitobe (Akita University Graduate School of Medicine) for her assistance with the data collection.

Funding

The present study was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research, Japan (grant no. 17K11121).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

KN was involved in the project development, data collection and management, data analysis, and manuscript writing. YH collected the data and edited the manuscript. SK was involved in data collection. AK, TN, SK, MS, SN, TI, TO and SC collected the data. NS collected the data and edited the manuscript. TH was involved in the project development, data collection, and manuscript editing.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics board of Akita University Hospital (approval no. 1993) and Japanese Red Cross Akita Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from each patient for the publication of their data.

Competing interests

Dr Habuchi received honoraria from Novartis International AG, Pfizer, Inc., GlaxoSmithKline and Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Powles T, Staehler M, Ljungberg B, Bensalah K, Canfield SE, Dabestani S, Giles R, Hofmann F, Hora M, Kuczyk MA, et al. Updated EAU guidelines for clear cell renal cancer patients who fail VEGF targeted therapy. Eur Urol. 2016;69:4–6. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Motzer RJ, Jonasch E, Agarwal N, Bhayani S, Bro WP, Chang SS, Choueiri TK, Costello BA, Derweesh IH, Fishman M, et al. Kidney cancer, version 2.2017, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15:804–834. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vachhani P, George S. VEGF inhibitors in renal cell carcinoma. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2016;14:1016–1028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF, George S, Hammers HJ, Srinivas S, Tykodi SS, Sosman JA, Procopio G, Plimack ER, et al. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1803–1813. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomita Y, Fukasawa S, Shinohara N, Kitamura H, Oya M, Eto M, Tanabe K, Kimura G, Yonese J, Yao M, et al. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma: Japanese subgroup analysis from the CheckMate 025 study. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2017;47:639–646. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyx049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma P, Allison JP. The future of immune checkpoint therapy. Science. 2015;348:56–61. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa8172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riaz N, Havel JJ, Makarov V, Desrichard A, Urba WJ, Sims JS, Hodi FS, Martín-Algarra S, Mandal R, Sharfman WH, et al. Tumor and microenvironment evolution during immunotherapy with nivolumab. Cell. 2017;171:934–949. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.028. e916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boutsikou E, Domvri K, Hardavella G, Tsiouda D, Zarogoulidis K, Kontakiotis T. Tumour necrosis factor, interferon-gamma and interleukins as predictive markers of antiprogrammed cell-death protein-1 treatment in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: A pragmatic approach in clinical practice. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2018;10:1758835918768238. doi: 10.1177/1758835918768238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Remon J, Besse B. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in first-line therapy of advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 2017;29:97–104. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Escudier B, Motzer RJ, Sharma P, Wagstaff J, Plimack ER, Hammers HJ, Donskov F, Gurney H, Sosman JA, Zalewski PG, et al. Treatment beyond progression in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma treated with nivolumab in checkmate 025. Eur Urol. 2017;72:368–376. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.George S, Motzer RJ, Hammers HJ, Redman BG, Kuzel TM, Tykodi SS, Plimack ER, Jiang J, Waxman IM, Rini BI. Safety and efficacy of nivolumab in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated beyond progression: A subgroup analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:1179–1186. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedman CF, Proverbs-Singh TA, Postow MA. Treatment of the immune-related adverse effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors: A review. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:1346–1353. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarocchi M, Grossi F, Arboscello E, Bellodi A, Genova C, Dal Bello MG, Rijavec E, Barletta G, Rossi G, Biello F, et al. Serial troponin for early detection of nivolumab cardiotoxicity in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients. Oncologist. 2018;23:936–942. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gauci ML, Laly P, Vidal-Trecan T, Baroudjian B, Gottlieb J, Madjlessi-Ezra N, Da Meda L, Madelaine-Chambrin I, Bagot M, Basset-Seguin N, et al. Autoimmune diabetes induced by PD-1 inhibitor-retrospective analysis and pathogenesis: A case report and literature review. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2017;66:1399–1410. doi: 10.1007/s00262-017-2033-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Makarious D, Horwood K, Coward JIG. Myasthenia gravis: An emerging toxicity of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Eur J Cancer. 2017;82:128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spain L, Diem S, Larkin J. Management of toxicities of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016;44:51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lipson EJ, Sharfman WH, Drake CG, Wollner I, Taube JM, Anders RA, Xu H, Yao S, Pons A, Chen L, et al. Durable cancer regression off-treatment and effective reinduction therapy with an anti-PD-1 antibody. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:462–468. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martini DJ, Hamieh L, McKay RR, Harshman LC, Brandao R, Norton CK, Steinharter JA, Krajewski KM, Gao X, Schutz FA, et al. Durable clinical benefit in metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients who discontinue PD-1/PD-L1 therapy for immune-related adverse events. Cancer Immunol Res. 2018;6:402–408. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skoulidis F, Goldberg ME, Greenawalt DM, Hellmann MD, Awad MM, Gainor JF, Schrock AB, Hartmaier RJ, Trabucco SE, Gay L, et al. STK11/LKB1 mutations and PD-1 inhibitor resistance in KRAS-mutant lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:822–835. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.