Abstract

Seed bezoars are a distinct subcategory of phytobezoars, caused by indigestible vegetable or fruit seeds. The aim of our study was to present a comprehensive review on seed bezoars, focusing on epidemiology, symptomatology, diagnosis and treatment options.

A systematic review of the English literature (1980-2018) was conducted, using PubMed, Embase and Google Scholar databases. Fifty-two studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria, with a total of 153 patients, the majority of whom (72%) came from countries around the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East.

Patients complained primarily about constipation (63%), abdominal/rectal pain (19%) or intestinal obstruction (17%). Most seed bezoars were found in the rectum (78%) and the terminal ileum (16%). Risk factors were recognised in 12% of cases. Manual disimpaction under general anaesthesia was the procedure of choice in 69%, while surgery was required in 22% of cases.

Seed bezoars appear to represent a different pathophysiological process compared to fibre bezoars. Seeds usually pass through the pylorus and ileocaecal valve, due to their small size, and accumulate gradually in the colon. Seed bezoars are usually found in the rectum of patients without predisposing factors, causing constipation and pain. History and digital rectal examination are the mainstay of diagnosis, with manual extraction under general anaesthesia being the procedure of choice.

Keywords: bezoar, phytobezoar

Introduction and background

Bezoars are retained aggregates of indigestible material that accumulate and conglomerate in the gastrointestinal tract. They can occur anywhere from the oesophagus to the rectum, however, they are most commonly found in the stomach. Recognised risk factors are prior gastric surgery, neuropsychiatric disease, endocrinopathies impairing gastrointestinal motility and poor mastication [1, 2].

Based on their component, they are classified into four main types: phytobezoar (fruit and vegetable fibres), trichobezoar (hair), lactobezoar (undigested milk concretions) and pharmacobezoar (medications) [1, 2]. Seed bezoars are a distinct subtype of phytobezoars, caused by undigested vegetable seeds or fruit pits. In contrast to other bezoar categories, the majority is found in the rectum of patients with no predisposing factors, a fact suggesting a different pathophysiological process [3, 4].

We hereby present a systematic, up-to-date review of case reports and case series of gastrointestinal seed bezoars, with emphasis on epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment options.

Review

Methods

We performed a systematic review of the literature, following the Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines, in order to identify all studies of patients with gastrointestinal seed bezoars [5]. Literature searches were conducted in PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE and Google Scholar bibliographic databases, spanning years 1980 to 2018. The keywords “bezoar”, “phytobezoar”, “seed”, “grain” and “pit” were used in all possible combinations. Moreover, the reference lists of all eligible studies were assessed for additional articles.

All study designs (case series and case reports) were eligible for inclusion in the final analysis. Patient age was not an exclusion criterion, and both adult and paediatric cases were included in the review. Articles without full text availability were excluded.

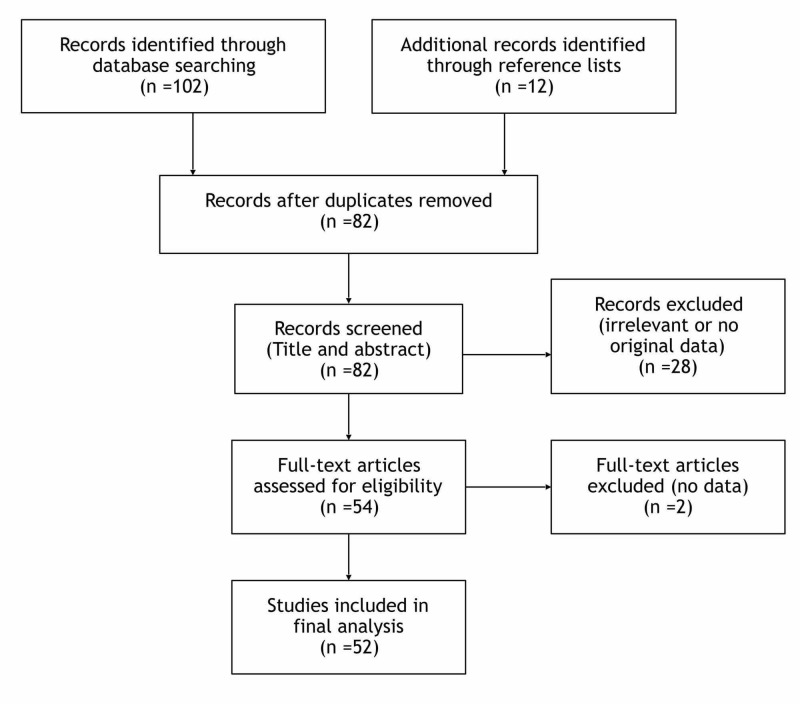

Titles and abstracts of all articles from the initial search were independently screened by two authors, to determine those articles for full text review. Any discrepancies concerning the evaluation of the studies were arbitrated by all authors. A flow chart of study selection is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flowchart of literature search.

For each eligible study, data were extracted about demographic (number of patients, age, sex, and country of origin) and clinical characteristics (seed type, predisposing factors, bezoar location, clinical presentation, diagnostic and therapeutic management).

Statistical analysis was performed on SPSS, version 20.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). All data were tabulated and outcomes were cumulatively analysed. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, while categorical variables were expressed as frequencies or percentages. Additionally, adult and paediatric subgroups were compared, using Student’s t-test for continuous variables and chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Statistical significance was set to p < 0.05.

Results

Fifty-two studies were included in the final analysis (two retrospective case series and 50 case reports), with a total of 153 patients (Appendix). Demographic characteristics of patients are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of seed bezoar cases.

| N | 153 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 90 |

| Female | 63 |

| Age range | 2 – 80 years |

| Paediatric cases | 2 – 16 years (median 10 years) |

| Adult cases | 18 – 80 years (median 44 years) |

| Country of origin | |

| Eastern Mediterranean basin - Middle East | 110 (71.9%) |

| Western Europe - America | 29 (19.0%) |

| Asia-Oceania | 14 (9.1%) |

The vast majority of cases (110/153, 71.9%) came from countries of the eastern Mediterranean basin and the Middle East, whereas 29 patients (19.0%) came from Western countries and 14 (9.1%) from Asia.

As far as the type of seed is concerned, most patients (55/153, 36.0%) consumed watermelon seeds (45 children, 10 adults), followed by sunflower seeds (30/153, 19.6%, 18 children, 12 adults) and prickly pears (28/153, 18.3%, six children, 22 adults). Other cases involved wild banana seeds (11/153, 7.2%), pumpkin seeds (5/153, 3.3%), pomegranate seeds (4/153, 2.6%), date seeds (2/153, 1.3%), tangerine pits (2/153, 1.3%), olive pits (2/153, 1.3%), lupin seeds (2/153, 1.3%), pop corn kernels (2/153, 1.3%), freekeh grains, sesame seeds, Baccaurea macrocarpa seeds, jaboticaba seeds, peanuts, lentil seeds, cherry pits, box myrtle seeds, mango seeds and granadilla seeds (one case each, 0.65%).

The majority of patients presented at the emergency department complained of constipation (96/153, 62.7%, 57 children, 39 adults). Twenty-nine patients (19.0%, 17 children, 12 adults) reported atypical abdominal or rectal pain accompanied by tenesmus or blood-tinged stools. The diagnostic workup revealed intestinal obstruction in 26 cases (17.0%, nine children, 17 adults). One elderly patient was diagnosed with acute abdomen due to rectal perforation, while in one case the seed bezoar was an incidental intraoperative finding. Risk factors for bezoar formation were recognised in 18 cases (11.7%, one child, 17 adults) and included gastrointestinal strictures (10/153, 6.5%), diabetes (4/153, 2.6%) and neuropsychiatric disease (4/153, 2.6%).

A thorough history and digital rectal examination at the emergency room usually hinted at the diagnosis. Endoscopy was employed in 20 patients (13.1%) and radiology (X-rays or abdominal CT scans) in 20 patients (13.1%). Rectal bezoars were found in 119 cases (77.8%, 70 children, 49 adults), followed by bezoars in the terminal ileum in 25 cases (16.3%, 11 children, 14 adults). In three cases (1.9%) bezoars were located in the sigmoid colon, in two cases each (1.3%) in the stomach and jejunum, whereas in one case each (0.66%), in the duodenum and caecum. Treatment options included manual disimpaction (106/153, 69.3%, 65 children, 41 adults), surgery (33/153, 21.5%, 12 children, 21 adults), endoscopy (5/153, 3.3%, five adults) or conservative measures (9/153, 5.9%, six children, three adults) (Table 2).

Table 2. Clinical characteristics of seed bezoar cases.

| N | % | |

| Clinical presentation | ||

| Constipation | 96 | 62.7 |

| Abdominal/rectal pain | 29 | 19.0 |

| Intestinal obstruction | 26 | 17.0 |

| Rectal perforation | 1 | 0.65 |

| Asymptomatic finding | 1 | 0.65 |

| Diagnostic workup | ||

| Endoscopy | 20 | 13.1 |

| Radiology (X-rays, CT scans) | 20 | 13.1 |

| Treatment | ||

| Manual disimpaction | 106 | 69.3 |

| Surgery | 33 | 21.5 |

| Endoscopy | 5 | 3.3 |

| Conservative measures | 9 | 5.9 |

Comparison of paediatric and adult populations (Table 3) showed that gender did not differ significantly between the two groups (p = 0.09), whereas consumption of watermelon seeds was more popular among children and of prickly pears among adults (p < 0.0001).

Table 3. Comparison of paediatric versus adult cases.

| Children | % | Adults | % | p-value | |

| N | 83 | 70 | |||

| Age (years) | 2-16 (median 10) | 18-80 (median 44) | |||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 54 | 65.1 | 36 | 51.4 | |

| Female | 29 | 34.9 | 34 | 48.6 | 0.09 |

| Seed type | |||||

| Watermelon | 45 | 54.2 | 10 | 14.3 | |

| Sunflower | 18 | 21.7 | 12 | 17.1 | |

| Prickly pear | 6 | 7.2 | 22 | 31.4 | <0.0001 |

| Localisation | |||||

| Rectum | 70 | 84.3 | 49 | 70 | |

| Terminal ileum | 11 | 13.3 | 14 | 20 | 0.17 |

| Symptoms | |||||

| Constipation | 57 | 68.7 | 39 | 55.7 | |

| Abdominal/rectal pain | 16 | 19.3 | 12 | 17.1 | |

| Intestinal obstruction | 9 | 10.8 | 17 | 24.3 | 0.07 |

| Treatment | |||||

| Manual disimpaction | 65 | 78.3 | 41 | 58.6 | |

| Surgery | 12 | 14.5 | 21 | 30 | |

| Conservative/endoscopy | 6 | 7.2 | 8 | 11.4 | 0.03 |

| Risk factors | 1 | 1.2 | 17 | 24.3 | <0.0001 |

In both groups, the rectum was the most common location of the seed bezoar and constipation was the prevailing symptom. Intestinal obstruction was more frequent in adults than in children (24.3% vs 10.8%), however it marginally did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.07). Manual disimpaction was the procedure of choice in the majority of both children (78.3%) and adults (58.6%). Surgical exploration was required more commonly in adults (30% vs 14.5%, p = 0.03). Finally, predisposing factors were more frequently reported in adult than in paediatric cases (24.3% vs 1.2%, p < 0.0001).

Discussion

The word “bezoar” derives its etymology from the Persian word “padzahr” or the Arabic “badizahr”, which both mean “antidote” [1]. Indeed, bezoars had been ascribed mystical powers and were popular through the Middle Ages as remedies against a variety of poisons [1, 6]. It was not until the 19th century that they were recognised as potentially serious medical conditions, being the cause of 3-7% of small intestinal obstructions [7, 8].

Seed bezoars are a distinct subgroup of phytobezoars, caused by the accumulation of indigestible vegetable or fruit seeds in the intestinal lumen. Grains and seeds usually pass through the pylorus and the ileocaecal valve, due to their small size, and accumulate gradually in the colon [3, 4, 9]. Reaching the rectum, the faecal mass is further dehydrated and forms a hard bezoar, commonly presenting as faecal impaction. This pathophysiological process of seed bezoars appears to be different from fibre bezoars, which are usually found in the stomach. Fibres contained in fruits and vegetables (cellulose, lignin, tannins) polymerise and agglutinate in the acidic environment of the stomach, and form a glue-like coagulum which affixes to other material and only rarely overcomes the pyloric sphincter [8, 10].

This hypothesis of different pathophysiology is further supported by the fact that seed bezoars seem to arise in patients without predisposing factors [3, 4]. In our review, previous gastric surgery, neuropsychiatric disease and endocrinopathies (diabetes, hypothyroidism) were recognised only in 12% of cases. On the contrary, retrospective series of gastric and intestinal fibre bezoar cases reported rates of risk factors exceeding 85% [7, 8, 11]. As expected, we observed these predisposing conditions significantly more frequently in adult patients compared to children (24.3% vs 1.2%, p < 0.0001).

Another interesting observation is the geographical distribution of cases, which may reflect the dietary habits across the Mediterranean basin and the Middle East, a diet still including fresh fruits and vegetables, as opposed to the “typical” western diet, based on processed carbohydrates and saturated fats [7]. Watermelons and prickly pears are common delicacies consumed during summer months, while dried sunflower and pumpkin seeds are a favourite snack among all ages and seasons.

As far as the clinical presentation is concerned, the pooled analysis found that seed bezoars occurred most frequently in the rectum, in both children and adults (84% and 70%, respectively). The primary complain was therefore constipation (69% of children, 56% of adults), followed by non-specific abdominal or rectal pain (19% of children, 17% of adults). Intestinal obstruction was relatively rare (17%) and mainly affected those patients with seed bezoars in the terminal ileum. While bowel perforation is the most feared complication, peritonitis was reported only in one case. On the contrary, fibre bezoars in the stomach may run asymptomatic for years or present with vague, non-specific symptoms including epigastric discomfort, abdominal bloating, nausea and vomiting, early satiety, post-prandial fullness, halitosis and weight loss [1].

Diagnosis of seed bezoars should be fairly straightforward, suggested by a careful history. Digital per rectum examination is the sine-qua-non of the diagnostic workup, aided by rectoscopy in selected cases. A full colonoscopy may be advisable in adult patients, to exclude malignant pathology, following bezoar extraction.

On the other hand, seed bezoars in the small intestine and colon are trickier to diagnose and require further investigations. Plain abdominal radiographs may show a solid stool mass, but generally they are within normal limits. Computerised tomography scans are considered the gold standard of diagnosis, offering information about the type, location and degree of obstruction, as well as potential bowel wall ischemia [12, 13]. Of the 20 patients who required supplementary imaging studies, 70% had bezoars proximal to the rectum.

In children with ambiguous right lower quadrant or hypogastric pain, negative imaging studies and suspicion of acute appendicitis, a digital rectal examination should not be omitted. Of 83 children diagnosed with seed bezoars, five had been admitted in hospital with an initial working diagnosis of appendicitis and in three of them a rectal bezoar was revealed, thus eliminating the need for surgery.

Manual evacuation under general anaesthesia is the procedure of choice for rectal seed bezoars, to minimise patient discomfort, while surgery is practically inevitable for small bowel seed bezoars presenting as intestinal obstruction [7]. Indeed, among the 33 cases of operative management in this review, 31 cases concerned seed bezoars of the stomach, duodenum, small and large bowel, proximal to the rectum. Depending on the intraoperative findings, the surgeon may choose between enterotomy and removal of the obstructing bezoar, fragmentation and milking of the bezoar through the ileocaecal valve, and segmental enterectomy.

Only 2/119 (1.7%) rectal seed bezoars required surgical intervention, while only 3/34 (8.8%) gastrointestinal seed bezoars were managed non-operatively with success. Furthermore, whereas manual disimpaction was the most commonly performed therapeutic procedure in both children and adults (78% and 59%, respectively), surgery was more frequently needed in adult patients (30% vs 14.5%, p = 0.03).

Although conservative treatment (endoscopy or chemical dissolution) works well for fibre bezoars, it does not appear to be efficient in patients with seed bezoars [7, 14, 15]. Our review showed that only 6% of seed bezoars were amenable to conservative measures (fleet enemas, stool softeners). Moreover, endoscopy alone usually failed to extract the bezoar, since the endoscope could not pass beyond the seed mass without risking perforation of the rectum, being successful only in 3% of cases.

Conclusions

In conclusion, seed bezoars should be considered as a distinct subgroup of phytobezoars, with different pathophysiology compared to bezoars caused by fibre accumulation. They are usually found in the rectum of children and adults without predisposing factors, causing constipation and pain. History and digital rectal examination are the cornerstones of diagnosis. In most patients rectal seed bezoars can be manually extracted under general anaesthesia, whereas intestinal seed bezoars are usually found in the terminal ileum causing intestinal obstruction and therefore mandate operative intervention.

Appendices

Table 4. Articles included in the final analysis.

| 1st Author | Year | Country | Journal | Article Data | Title | N |

| Melchreit | 1984 | USA | N Engl J Med | 310:1748-9 | ‘Colonic crunch’ sign in sunflower-seed bezoar | 1 |

| Cloonan | 1988 | USA | Ann Emerg Med | 17:873-4 | Rectal bezoar from sunflower seeds | 1 |

| Roberge | 1988 | USA | Ann Emerg Med | 17:131-3 | Popcorn Primary Colonic Phytobezoar | 1 |

| Dent | 1989 | USA | Am J Dis Child | 143:643-4 | Sunflower seed bezoar presenting as diarrhea | 1 |

| Meeroff | 1989 | USA | Am J Gastroenterol | 84:650-2 | Gastric lupinoma: a new variety of phytobezoar | 1 |

| Shah | 1990 | USA | Pediatr Emerg Care | 6:127-8 | Polyethylene glycol-electrolyte solution for rectal sunflower seed bezoar | 1 |

| Philips | 1991 | USA | Ann Emerg Med | 20:171-2 | Sunflower Seed Syndrome: A prickly proctological problem | 1 |

| Tsin | 1994 | Israel | Harefuah | 127:227-8 | Intestinal obstruction due to lupin phytobezoar in a child | 1 |

| Purcell | 1995 | USA | South Med J | 88:87-8 | Sunflower seed bezoar leading to fecal impaction | 2 |

| Efrati | 1997 | Israel | J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr | 25:214-6 | Phytobezoar-induced ileal and colonic obstruction in childhood | 3 |

| Tsou | 1997 | USA | Pediatrics | 99:896-7 | Colonic sunflower seed bezoar | 2 |

| Burstein | 2000 | Israel | Israel Med Assoc J | 2:129-31 | Small Bowel Obstruction and Covered Perforation in Childhood Caused by Bizarre Bezoars and Foreign Bodies | 1 |

| Moons | 2000 | Netherlands | Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd | 144:1878-8 | Severe obstipation due to eating unshelled sunflower seeds | 2 |

| Lowry | 2001 | USA | Gastrointest Endosc | 53:388-9 | Sunflower seed rectal bezoar in an adult | 1 |

| Pitiakoudis | 2003 | Greece | Acta Chir Iugosl | 50:131-3 | Phytobezoars as a cause of small bowel obstruction associated with a carcinoid tumor of the ileocecal area | 1 |

| Sawnani | 2003 | USA | J La State Med Soc | 155:163-4 | Proctological crunch: sunflower-seed bezoar | 1 |

| Steinberg | 2003 | Israel | Int J Colorectal Dis | 18:365-7 | Prickly pear fruit bezoar presenting as rectal perforation in an elderly patient | 1 |

| Schoffl | 2004 | Laos | Asian J Surg | 27:348-51 | Intestinal obstruction due to phytobezoars of banana seeds: A case report | 4 |

| Alexander | 2005 | India | Indian J Gastroenterol | 24:273-4 | Cherry pip bezoars causing acute small intestinal obstruction presenting as diabetic ketoacidosis | 1 |

| Bakr | 2006 | UAE | Acta Paediatr | 95:886-7 | Rectal sunflower seed bezoar | 1 |

| Eitan | 2006 | Israel | Dis Colon Rectum | 49:1768-71 | Fecal impaction in children: report of 53 cases of rectal seed bezoars | 30 |

| Shaw | 2007 | UK | J Med Case Rep | 1:1-4 | Large bowel obstruction due to sesame seed bezoar: a case report | 1 |

| Singh | 2007 | Oman | Australas Radiol | 51:126-9 | Duodenal date seed bezoar: A very unusual cause of partial gastric outlet obstruction | 1 |

| Eitan | 2007 | Israel | J Pediatr Surg | 42:1114-7 | Fecal impaction in children: report of 53 cases of rectal seed bezoars | 53 |

| Bedioui | 2008 | Tunisia | Gastroenterol Clin Biol | 32:596-600 | A report of 15 cases of small-bowel obstruction secondary to phytobezoars: Predisposing factors and diagnostic difficulties | 8 |

| Kok | 2009 | Turkey | J Emerg Med | 41:537-8 | Pumpkin seed bezoar initially suspected as child abuse | 1 |

| Mirza | 2009 | Oman | Trop Doct | 39:54-5 | Rectal bezoars due to pumpkin seeds | 1 |

| Schucany | 2009 | USA | Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) | 22:164-5 | Abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting in a 10-year-old girl | 1 |

| Kavlakoglu | 2010 | Turkey | Turkish J Gastroenterol | 22:442-3 | Very rare coincidence: Perforated duodenal ulcer and olive seed phytobezoar | 1 |

| Lane | 2010 | USA | Pediatr Emerg Care | 26:662-4 | Sunflower rectal bezoar presenting with an acute abdomen in a 3-year old child | 1 |

| Minty | 2010 | Canada | Can Med Assoc J | 182:91991 | Rectal bezoars in children | 1 |

| Thing | 2010 | Denmark | Ugeskr Laeger | 172:2905-6 | Rectal bezoar caused by sunflower seeds | 1 |

| Britton | 2011 | Australia (Iraqi) | J Paediatr Child Health | 47:68-9 | A case of impacted watermelon seed rectal bezoar in a 12-year-old girl | 1 |

| Chauhan | 2011 | India | Indian J Radiol Imaging | 21:21-3 | Case report: Colonic bezoar due to Box Myrtle seeds: A very rare occurrence | 1 |

| Slesak | 2011 | Laos | Trop Doct | 41:85-90 | Bowel obstruction from wild bananas: a neglected health problem in Laos | 6 |

| Luporini | 2012 | Brasil | J Coloproctol | 32:308-11 | Intestinal obstruction caused by phytobezoar composed of jaboticaba seeds: case report and literature review | 1 |

| Manne | 2012 | USA | Clin Med Res | 10:75-7 | A Crunching colon: Rectal bezoar caused by pumpkin seed consumption | 1 |

| Martinez-Pasqual | 2012 | Spain | Rev Esp Enferm Dig | 104:266-7 | Rectal ulcer secondary to a fecal impaction due to pomegranate seed bezoar | 1 |

| Al-Rashid | 2013 | Saudi Arabia | BMJ Case Rep | 2013:1-2 | Beware of what you eat: small bowel obstruction caused by freekeh bezoars | 1 |

| Lim | 2013 | USA | Endoscopy | 45:65212 | Unusual cause of constipation: Sunflower seeds bezoar | 1 |

| El-Majzoub | 2014 | Lebanon | Ann Saudi Med | 104:2014 | Rectal impaction by pomegranate seeds | 1 |

| Kia | 2014 | Iran | West J Emerg Med | 15:385-6 | Intestinal Obstruction Caused by Phytobezoars | 1 |

| Metussin | 2014 | Brunei | Turkish J Gastroenterol | 25:270-1 | Rectal bleeding from seeds impaction | 1 |

| Plataras | 2014 | Greece | BMJ Case Rep | 2014:1-3 | An unusual cause of small bowel obstruction in children: lentil soup bezoar | 1 |

| Mahmood | 2015 | USA | ACG Case Rep J | 2:200-1 | Rectal Pain and the Colonic Crunch Sign | 1 |

| Marchese | 2015 | Italy | J Biol Regul Homeost Agents | 29:707-11 | Rectal impaction due to prickly pear seeds bezoar: a case report | 1 |

| Akrami | 2016 | Iran | Iran J Public Health | 45:1080-2 | Dietary Habits Affect Quality of Life: Bowel Obstruction Caused by Phytobezoar | 1 |

| Chai | 2016 | Malaysia | Indian J Surg | 78:326-8 | Wild Banana Seed Phytobezoar Rectal Impaction Causing Intestinal Obstruction | 1 |

| Nehme | 2017 | USA | ACG Case Rep J | 4:e49 | Pumpkin Seed Bezoar Causing Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding | 1 |

| Alexandre | 2018 | Portugal | BMJ Case Rep | 2018 | Giant granadilla’s seeds phytobezoar rectal impactation: a very unusual case of intestinal obstruction | 1 |

| Islam | 2018 | Trinidad and Tobago | Int J Surg Case Rep | 51:125-9 | Mango seed causing acute large bowel obstruction in descending colon-world’s first reported case | 1 |

| Manatakis | 2018 | Greece | Pan Afr Med J | 31:157 | Rectal seed bezoar due to sunflower seed: a case report and review of the literature | 1 |

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.Bezoars: from mystical charms to medical and nutritional management. Sanders MK. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285766469_Bezoars_From_Mystical_Charms_to_Medical_and_Nutritional_Management Pract Gastroenterol. 2004;28:37–50. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gastrointestinal bezoars: history and current treatment paradigms. Eng K, Kay M. http://www.gastroenterologyandhepatology.net/archives/november-2012/gastrointestinal-bezoars-history-and-current-treatment-paradigms/ Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;8:776–778. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fecal impaction in adults: report of 30 cases of seed bezoars in the rectum. Eitan A, Bickel A, Katz IM. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1768–1771. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0713-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fecal impaction in children: report of 53 cases of rectal seed bezoars. Eitan A, Katz IM, Sweed Y, Bickel A. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:1114–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/192614. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The bezoar stone: a princely antidote, the Távora Sequeira Pinto Collection-Oporto. Do Sameiro Barroso M. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25310610. Acta Med Hist Adriat. 2014;12:77–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Review of the diagnosis and management of gastrointestinal bezoars. Iwamuro M, Okada H, Matsueda K, Inaba T, Kusumoto C, Imagawa A, Yamamoto K. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;7:336–345. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v7.i4.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Synergistic effect of multiple predisposing risk factors on the development of bezoars. Kement M, Ozlem N, Colak E, et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:960–964. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i9.960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rectal seed bezoar due to sunflower seed: a case report and review of the literature. Manatakis D, Sioula M, Passas I, Zerbinis H, Dervenis C. Pan Afr Med J. 2018;31:157. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2018.31.157.12539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diospyrobezoar as a cause of small bowel obstruction. Padilha De Toledo A, Hurtado Rodrigues F, Rocha Rodrigues M, Tiemi Sato D, Nonose R, Nascimento EF, Martinez CAR. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2012;6:596–603. doi: 10.1159/000343161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gastrointestinal bezoars: a retrospective analysis of 34 cases. Erzurumlu K, Malazgirt Z, Bektas A, et al. http://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/11/1813.asp. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:1813–1817. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i12.1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imaging differentiation of phytobezoar and small-bowel faeces: CT characteristics with quantitative analysis in patients with small-bowel obstruction. Chen YC, Liu CH, Hsu HH, et al. Eur Radiol. 2015;25:922–931. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3486-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ultrasonographic differentiation of bezoar from feces in small bowel obstruction. Lee KH, Han HY, Kim HJ, Kim HK, Lee MS. Ultrasonography. 2015;34:211–216. doi: 10.14366/usg.14070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Systematic review: Coca-Cola can effectively dissolve gastric phytobezoars as a first-line treatment. Ladas SD, Kamberoglou D, Karamanolis G, Vlachogiannakos J, Zouboulis-Vafiadis I. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:169–173. doi: 10.1111/apt.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.In vitro analysis of gastric phytobezoar dissolubility by Coca-Cola, Coca-Cola Zero, cellulase, and papain. Iwamuro M, Kawai Y, Shiraha H, Takaki A, Okada H, Yamamoto K. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48:190–191. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182a39116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]