Abstract

It is widely believed that hemiballismus and chorea are suggestive of a basal ganglia subthalamic nucleus lesion; however, this not a rule. We report the case of a 63-year-old male with complaints of slurred speech, increased movement of the left half of his body, and headache. He had diabetes, hypertension, and a past medical history of stroke with residual weakness over the right side of his body. The patient developed the sudden onset of irregular, large amplitude, increased involuntary movements of his left upper and lower limbs with a flinging pattern. His blood sugar and serum osmolality were normal. His magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed an acute right parietal lobe infarction. Patients can experience hemiballismus with lesions other than the subthalamic nucleus in the basal ganglia. This is contrary to the classic belief that hemiballismus is associated with, and only with, lesions in the subthalamic nucleus. This manuscript describes a case of hemiballismus occurring in a patient secondary to a parietal lobe infarction.

Keywords: stroke, hemiballismus, parietal lobe, subthalamic nucleus, basal ganglia, hemichorea, tetrabenazine, hemichorea-hemiballismus syndrome

Introduction

Hemiballismus is defined as irregular, involuntary, large amplitude flinging movements by the limbs confined to one side of the body [1]. Depending on the areas of the brain affected, patients can present with certain common clinical features as per the affected area. For example, if a patient has an infarction of the motor cortex, then they commonly present with hemiplegia or paralysis on one side of the body. Infarctions involving language areas of the brain will present with aphasia or impairment of language. This will affect the production or comprehension of speech and the ability to read and write.

Hemiballismus was first described in 1949 [2]. Dr. J.R. Whittier, who was studying the subthalamic nucleus of rhesus monkeys at the time, noted that when there was a minimum of 20% area damage, then hemiballismus would be induced in the contralateral limbs [2]. The traditional belief of hemiballismus being a direct result of subthalamic nucleus infarction originates from his work. The following report is one of the cases that disprove that traditional belief.

Case presentation

A 63-year-old male was admitted with complaints of acute onset, increased, involuntary, violent movements of his left upper and lower limbs. His past medical history included diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and an ischemic stroke 20 years prior with residual right spastic hemiplegia. He had a below-the-knee amputation done on the right lower limb three years earlier due to peripheral vascular disease and gangrene.

After the patient was admitted, a full history and physical examination were performed. With the exception of the amputated right lower limb, the examination of his vitals, head, neck, cardiovascular, pulmonary, and abdominal systems were without abnormalities.

On neurological examination, the patient was alert, awake, and oriented to time, place, and person. He was obeying vocal commands but had continuous, large amplitude, irregular, involuntary movements in his left upper and lower limbs. The movements had a flinging pattern suggestive of hemiballismus (see Video 1). His muscle power was decreased on the right side of his body with normal muscle power in both the left upper and lower limbs. No paralysis was noted over the left side of the body.

Video 1. Hemiballismus Seen in the Patient Secondary to Right-sided Parietal Lobe Infarction.

The patient was unable to prevent the large amplitude flinging movements suggestive of left-sided hemiballismus. The video was created within 48 hours of the patient's stroke.

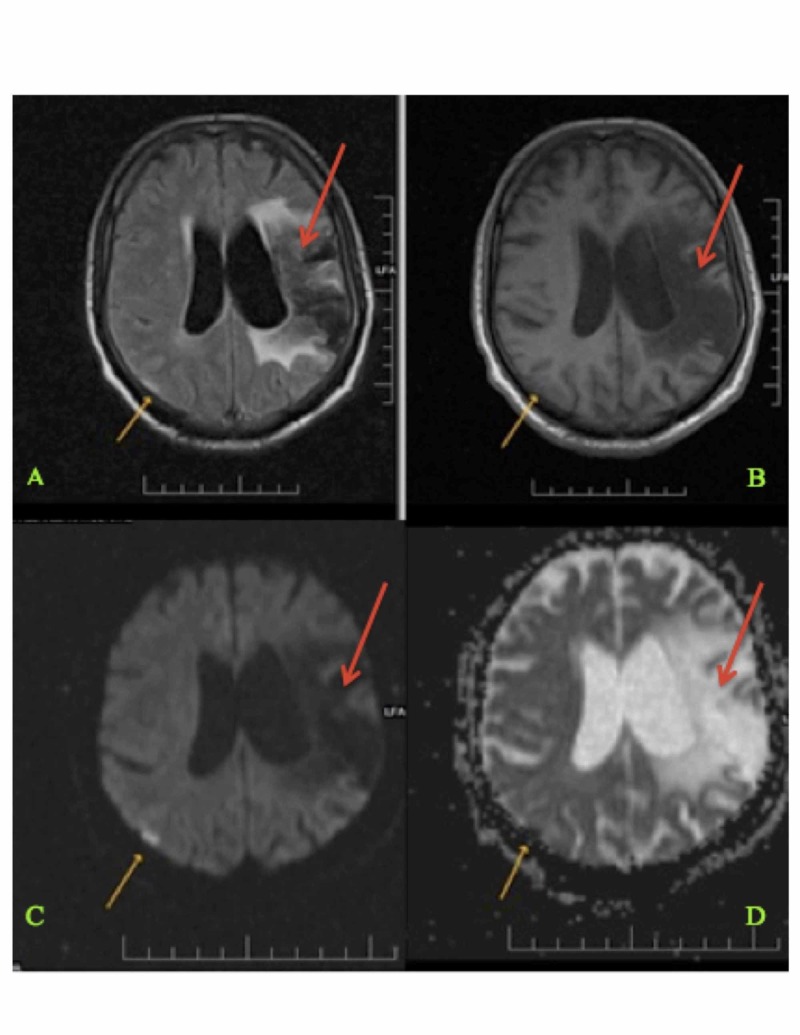

His blood sugar, serum electrolytes, and serum osmolality were within the normal range. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain revealed an acute right parietal lobe infarct with an old middle cerebral artery territory infarct (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the Brain Showing Current and Previous Infarction Sites (Panels A-D) .

Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showing an acute right-sided parietal lobe infarct (shown with yellow arrows) and an old left-sided middle cerebral artery territory infarct (shown with red arrows).

Discussion

Hemiballismus is a series of abnormal flinging movements that are involuntary and involve one-half of the body [1]. Depending on the side infarcted, there is hemiballismus of the contralateral side. Hemiballismus usually involves an arm or a leg, is proximal in most cases, and can have facial involvement in approximately half of the patient cases [3]. Another hyperkinetic movement disorder confined to one side of the body is hemichorea. It is an involuntary, occasional, rapid, non-patterned series of movements. Hemiballismus is considered to be a more severe expression of hemichorea [3]. Hemichorea-hemiballismus (HCHB) syndrome is a condition where patients have both of these movements in combination with one another [1]. The commonly described causes of HCHB syndrome include hemorrhagic or ischemic stroke, neoplasm, systemic lupus erythematosus, a hyperglycemic hyperosmolar non-ketotic (HONK) state, Wilson's disease, and thyrotoxicosis [4]. Even in these cases, MRI of the brain usually reveals T2 fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) hyperintense signals involving the basal ganglia, more specifically, the part that contains the subthalamic nucleus. One documented case had a cerebral cavernous angioma in the posterior limb of the left internal capsule and in the lateral part of the left thalamoganglionic region [5]. The common belief is that hemiballismus is associated with a subthalamic nucleus dysfunction. However, with the advent of MRI and its increased use in acute stroke care, an increasing number of hemiballismus cases are proven to have confirmed parietal lobe involvement.

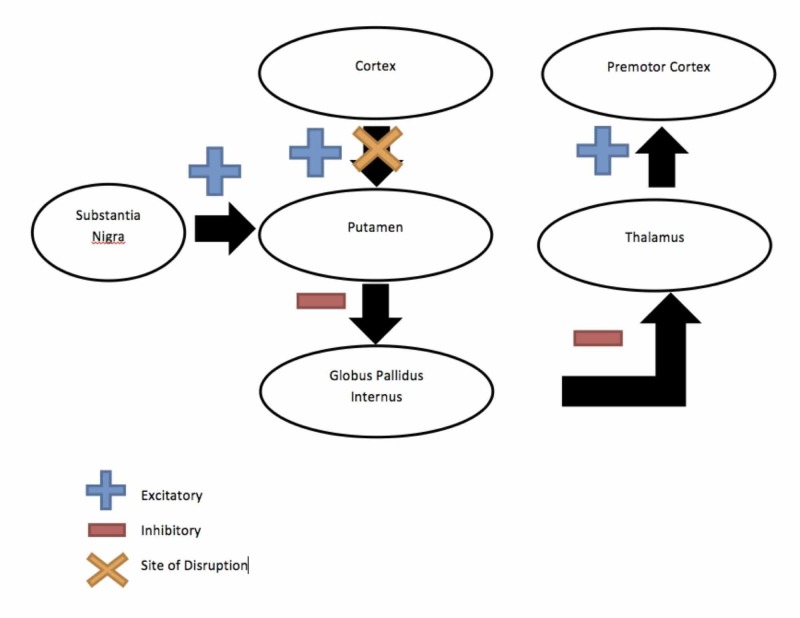

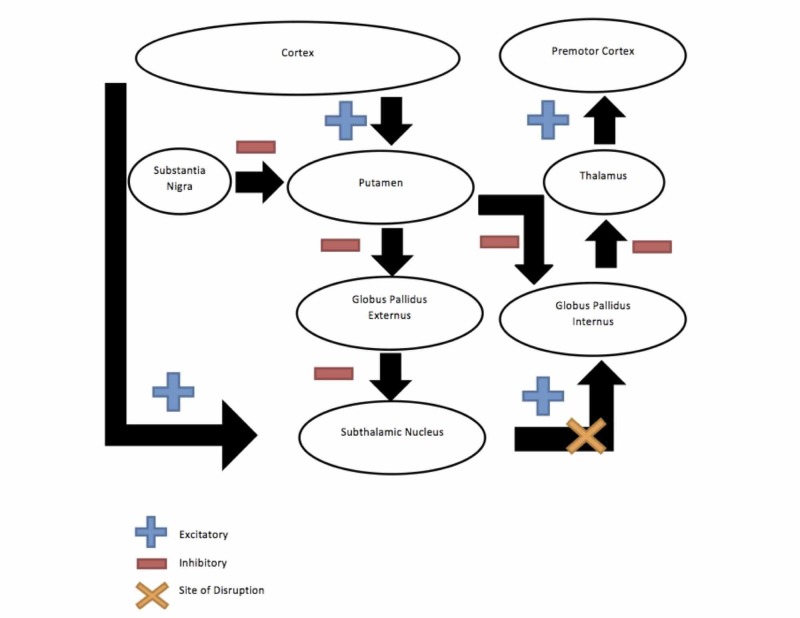

We describe a patient who had acute hemiballismus following an ischemic stroke involving the parietal lobe and not the basal ganglia or, more specifically, the subthalamic nucleus. A magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) of the intracranial vessels was also found to be normal. There have been previous cases of hemiballismus reported with parietal lobe infarct with the absence of basal ganglia infarction (Table 1). The earliest published case of hemiballismus with parietal infarct was in 1997 [6]. There exists a balance between the direct pathway (cortex-caudate-internal pallidum, accounting for the dyskinesias) and the indirect pathway (cortex-caudate-external pallidum-subthalamic nucleus-internal pallidum, accounting for the akinesia), which modulate the thalamocortical retroactive pathway for control of voluntary movements [7]. We generated diagrams of the direct pathway and an indirect pathway below for clarification (Figures 2-3). Classically, lesions of the subthalamic nucleus are said to disrupt this balance but that does not exclude lesions of the corticostriatal fibers. Under normal physiologic conditions, the cerebral cortex provides excitatory stimuli to the basal ganglia [8]. Thus, lesions involving corticostriatal fibers (in the parietal cortex) may disrupt the balance of basal ganglia circuits [9]. This is one possible hypothesis for the occurrence of hemiballismus in patients with parietal lesions. The other possible hypothesis could be associated hypoperfusion of the subthalamic region not picked up on the initial MRI in the hyperacute stage of the infarct. In 1989, Barinagarrementeria et al. described a case of parietal lobe infarct where perfusion studies revealed evidence of reduced perfusion to the radiologically unaffected striatum [6, 10-11]. They suggested that hypoperfusion of the subthalamic region undetected on the initial scan could be the underlying influence in “cortical” hemiballismus in their case. This is possible because the subthalamic nucleus is located at the arterial border zone position between the anterior and posterior circulation of which compromising carotid stenosis could lead to hypoperfusion [12]. In our patient, special imaging techniques for detection of hypoperfusion were not required because the first imaging itself was done more than 24 hours post-symptom onset and also angiography findings were normal; however, the possibility of subthalamic hypoperfusion cannot be entirely ruled out.

Table 1. Cases of Hemiballismus-Hemichorea Occurring with Parietal Infarction without Lesion to Basal Ganglia.

These are previous cases of hemiballismus-hemichorea occurring with parietal lobe infarction. In each case, there is an absence of infarction in the basal ganglia.

| Author and Year | Case Report Name | Age | Sex | Duration | Side of Infarct | Treatment | Outcome |

| 1997, Mizushima et al. [6] | A Case of Hemichorea-Hemiballism Associated with Parietal Lobe Infarction | 80 | Male | 13 days | Right-sided parietal lobe infarction was present. | Not specified | Symptoms subsided and the patient was discharged with slightly diminished deep sensation. |

| 2003, Rosetti et al. [9] | Neurogenic Pain and Abnormal Movements Contralateral to an Anterior Parietal Artery Stroke | 74 | Male | 3 weeks | Acute infarction of the right anterior parietal cortex, extending to the upper posterior temporal lobe and the adjacent white matter | Haloperidol and anticoagulants | Hemiballismus subsided |

| 2004, Al-Yacoub et al. [13] | Hemiballismus from a Parietal Stroke in a Parkinson Patient | 77 | Male | 4 days | Large right-sided parietal infarct was present. | Very low dose clozapine | Hemiballismus reduced |

| 2006, Sugiura A, Fujimoto M [14] | Facial Chorea and Hemichorea due to Cardiogenic Cerebral Embolism in the Cortex and Subcortical White matter | 62 | Male | 1 day | Acute cortical and subcortical infarctions at the right insula, frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes. | Tiapride hydrochloride | Chorea subsided |

| 2012, Umeh et al. [15] | Dual Treatment of Hemichorea Hemiballismus Syndrome with Tetrabenazine and Chemodenervation | 65 | Male | 9 months | Right posterior frontal lobe white matter and small cortical infarcts in the right temporal-frontal-parietal junction | Haloperidol, risperidone, valproic acid, tetrabenazine, onabotulinum toxin A | Moderate reduction of symptoms |

| 2013, Hwang et al. [16] | Cortical Hemichorea-Hemiballismus | 70 | Female | 2 months | Left parietal cortex | Haloperidol | Follow-up after four years confirmed no further episodes. |

| 2015, Shrestha et al. [1] | Hemiballism in a Patient with Parietal Lobe Infarction | 61 | Male | 2 days | Acute posterior left parietal lobe infarction | Aspirin, atorvastatin, warfarin | Movements resolved spontaneously. |

Figure 2. Direct Pathway (in the Case of Cortical Hemiballismus).

Demonstrating the direct pathway from the cortex to the caudate to the internal palladium, thus accounting for dyskinesias seen in cortical hemiballismus

Figure 3. Indirect Pathway (in the Case of Subthalamic Hemiballismus).

Demonstrating the indirect pathway, going from the cortex to the caudate nucleus to the external palladium to the subthalamic nucleus and finally to the internal palladium. This accounts for akinesia in the case of subthalamic hemiballismus.

The majority of the cases of hemiballismus have a favorable outcome by either spontaneous resolution or by the improvement of movements within weeks to months. During the early stages, hemiballismus can be injurious to the patient and would require prompt medical treatment. Medications used to treat hemiballismus include neuroleptics, valproic acid, topiramate, gabapentin, and dopamine-depleting drugs. Patients with chronic hemiballismus, refractory to medical treatment, may need a pallidotomy, a thalamotomy, or deep brain stimulation. We prescribed tetrabenazine in a dose of 12.5 mg given three times a day that was then titrated to 25 mg given three times a day during the course of a week, which led to a complete recovery of the hemiballismus in our patient. His treatment was continued for two additional weeks and was then stopped. Tetrabenazine has also been used in other cases of hemiballismus with a successful resolution of symptoms [17]. Other published cases of hemiballismus with parietal lesions have all had a good prognosis with some resolving spontaneously and others treated with neuroleptics, such as haloperidol or clozapine. None of the cases were refractory to medical treatment.

Conclusions

We describe a patient with a right-sided parietal lobe infarction presenting with left-sided hemiballismus that resolved after completing treatment with tetrabenazine. Our case highlights the fact that besides the subthalamic nucleus, any lesions to the cortex, to the subthalamic-pallidal fibers, to the striatopallidal connections, or to the corona radiata may induce hemiballismus in a patient.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained by all participants in this study. Institutional Ethics Committee, HM Patel Centre for Medical Care and Education Karamsad issued approval ECR/331/Inst/GJ/2013. Date: 10/17/2016 Subject: Approval of Your Research Proposal Submitted for Exempt Review Your research proposal "Acute Hemiballismus as the Presenting Feature of Parietal Lobe Infarction" was submitted for exempt review and was perused by the committee members for consideration towards approval. Being a data based research and declaration regarding maintenance of privacy and confidentiality, it qualified for Exempt from Full Committee Review. After perusal by committee members, the research proposal is approved by IEC to be conducted in its present form with waiver of consent for data collection. The Institutional Ethics committee functions as per the requirements of the ICH-GCP, ICMR, Revised Schedule Y and their SOP'd. The Registration Number of IEC is ECR/331/Inst/GJ/2013. The IEC expects to be informed about the progress of the study, any serious adverse event occurring in the course of the study, any changes in protocol and participant information sheet/informed consent document and asks to be provided a copy of the final report. Signed, Institutional Ethics Committee

References

- 1.Cortical hemiballism: a case of hemiballismus associated with parietal lobe infarct. Shrestha P, Adhikari J, Poudel D, Pathak R, Karmacharya P. N Am J Med Sci. 2015;7:572–574. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.172850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Studies on the subthalamus of the rhesus monkey; hyperkinesia and other physiologic effects of subthalamic lesions; with special reference to the subthalamic nucleus of Luys. Whittier JR, Mettler FA. J Comp Neurol. 1949;90:319–372. doi: 10.1002/cne.900900304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hemichorea/hemiballism associated with hyperglycemia: report of 20 cases. Cosentino C, Torres L, Nuñez Y, Suarez R, Velez M, Flores M. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 2016;6:402. doi: 10.7916/D8DN454P. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hemiballismus: current concepts and review. Hawley JS, Weiner WJ. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012;18:125–129. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.A case of hemichorea caused by cerebral cavernous angioma. Kongsakorn N, Maroongroge P. http://www.jmatonline.com/index.php/jmat/article/view/6804. J Med Assoc Thai. 2015;98:165–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.A case of hemichorea-hemiballism associated with parietal lobe infarction. Mizushima N, Park-Matsumoto YC, Amakawa T, Hayashi H. Eur Neurol. 1997;37:65–66. doi: 10.1159/000117408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Functional architecture of basal ganglia circuits: neural substrates of parallel processing. Alexander GE, Crutcher MD. Trends Neurosci. 1990;13:266–271. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90107-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neurochemical anatomy of movement disorders. Young AB, Penney JB. Neurol Clin. 1984;2:417–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neurogenic pain and abnormal movements contralateral to an anterior parietal artery stroke. Rossetti AO, Ghika JA, Vingerhoets F, Novy J, Bogousslavsky J. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1004–1006. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.7.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Acute hemichorea due to infarction in the corona radiata. Barinagarrementeria F, Vega F, DelBrutto OH. J Neurol. 1989;236:371–372. doi: 10.1007/BF00314386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hemichoreoathetosis following posterior parietal watershed infarction: was striatal hypoperfusion really to blame? Lee MS, Lyoo CH, Lee HJ, Kim YD. Mov Disord. 2000;15:178–179. doi: 10.1002/1531-8257(200001)15:1<178::aid-mds1034>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.A case of complete resolution of hemiballismus after carotid endarterectomy. Joseph JR, Delavari N, Wilkinson DA, Roark C, Thompson BG. World Neurosurg. 2016;95:624–620. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hemiballismus from a parietal stroke in a Parkinson patient. Al-Yacoub M, Friedman JH, Fernandez HH. Mov Disord. 2004;19:986–988. doi: 10.1002/mds.20204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Facial chorea and hemichorea due to cardiogenic cerebral embolism in the cortex and subcortical white matter (Article in Japanese) Sugiura A, Fujimoto M. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Facial+chorea+and+hemichorea+due+to+cardiogenic+cerebral+embolism+in+the+cortex+and+subcortical+white+matter. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2006;46:415–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dual treatment of hemichorea-hemiballismus syndrome with tetrabenazine and chemodenervation. Umeh CC, Nichols P, Rosenthal LS, Mari Z. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 2012;2:0–3. doi: 10.7916/D86Q1VZD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cortical hemichorea-hemiballism. Hwang KJ, Hong IK, Ahn TB, Yi SH, Lee D, Kim DY. J Neurol. 2013;260:2986–2992. doi: 10.1007/s00415-013-7096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tetrabenazine for hyperglycemic-induced hemichorea-hemiballismus. Sitburana O, Ondo WG. Mov Disord. 2006;21:2023–2025. doi: 10.1002/mds.21100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]