Abstract

BACKGROUND

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) is a neurodegenerative disease that has been associated with a history of repetitive head impacts. The neuropathological diagnosis is based on a specific pattern of tau deposition with minimal amyloid-beta deposition that differs from other disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease. The feasibility of detecting tau and amyloid deposition in the brains of living persons at risk for CTE has not been well studied.

METHODS

We used flortaucipir positron-emission tomography (PET) and florbetapir PET to measure deposition of tau and amyloid-beta, respectively, in the brains of former National Football League (NFL) players with cognitive and neuropsychiatric symptoms and in asymptomatic men with no history of traumatic brain injury. Automated image-analysis algorithms were used to compare the regional tau standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR, the ratio of radioactivity in a cerebral region to that in the cerebellum as a reference) between the two groups and to explore the associations of SUVR with symptom severity and with years of football play in the former-player group.

RESULTS

A total of 26 former players and 31 controls were included in the analysis. The mean flortaucipir SUVR was higher among former players than among controls in three regions of the brain: bilateral superior frontal (1.09 vs. 0.98; adjusted mean difference, 0.13; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.06 to 0.20; P<0.001), bilateral medial temporal (1.23 vs. 1.12; adjusted mean difference, 0.13; 95% CI, 0.05 to 0.21; P<0.001), and left parietal (1.12 vs. 1.01; adjusted mean difference, 0.12; 95% CI, 0.05 to 0.20; P= 0.002). In exploratory analyses, the correlation coefficients in these three regions between the SUVRs and years of play were 0.58 (95% CI, 0.25 to 0.79), 0.45 (95% CI, 0.07 to 0.71), and 0.50 (95% CI, 0.14 to 0.74), respectively. There was no association between tau deposition and scores on cognitive and neuropsychiatric tests. Only one former player had levels of amyloid-beta deposition similar to those in persons with Alzheimer’s disease.

CONCLUSIONS

A group of living former NFL players with cognitive and neuropsychiatric symptoms had higher tau levels measured by PET than controls in brain regions that are affected by CTE and did not have elevated amyloid-beta levels. Further studies are needed to determine whether elevated CTE-associated tau can be detected in individual persons. (Funded by Avid Radiopharmaceuticals and others.)

CHRONIC TRAUMATIC ENCEPHALOPATHY (CTE) is a neurodegenerative disease associated with exposure to repetitive head impacts, such as those incurred in contact or collision sports.1–4 The disease is defined neuropathologically by the deposition of paired helical filament tau aggregates in neurons, astrocytes, and cell processes in an irregular pattern around small blood vessels at the depths of cortical sulci. The tau aggregates are initially observed in the frontal, temporal, and parietal cortices5 and in later stages of disease are more extensively distributed throughout the cerebral cortex, medial temporal lobe, diencephalon, and brain stem.1,2 This pattern distinguishes CTE from other neurodegenerative diseases, including other tauopathies, such as Alzheimer’s disease and certain forms of frontotemporal neurodegeneration.5 Unlike Alzheimer’s disease, CTE typically involves neuritic amyloid-beta plaque deposition only in advanced stages of disease.2

Although persons with the neuropathologic features of CTE have been reported to have cognitive impairment, mood disturbance, and behavioral dyscontrol,2,6,7 it is unclear whether these features are associated with regional tau deposition, tau-related neuronal degeneration, or other consequences of brain trauma. In neuropathological studies involving convenience samples of former American football players, the number of years of tackle football experience has been associated with the severity of tau deposition.8 Because CTE can be diagnosed only through postmortem neuropathological examination, detection of the disease during life could be used to assess its epidemiology, risk factors, and course and could be used in treatment and prevention trials.9

Positron-emission tomography (PET) with the selective radioligand 18F-flortaucipir has been studied to detect paired helical filament tau deposition in persons with Alzheimer’s disease,10 but its ability to detect tau deposition in other neurodegenerative diseases is uncertain.11 Elevated flortaucipir PET measurements have been reported in a 39-year-old former National Football League (NFL) player with symptoms of CTE,12 but confirmatory studies are needed.

We used flortaucipir PET measurement of paired helical filament tau deposition and 18F-florbetapir PET measurement of amyloid-beta deposition to compare the brains of living former NFL players who had cognitive, mood, and behavioral symptoms with the brains of asymptomatic men who did not have a history of traumatic brain injury.

METHODS

PARTICIPANTS

The participants were 26 former NFL players who reported cognitive, mood, and behavioral dyscontrol symptoms and 31 asymptomatic control participants who reported no history of traumatic brain injury (Table 1). The inclusion criteria for the former players were male sex, age 40 to 69 years, a minimum of 2 years playing football in the NFL, a minimum of 12 years of total tackle football experience, and cognitive, behavioral, and mood symptoms reported by the participant through telephone screening. Quarterbacks, kickers, and special-teams players were excluded, as were former players with a reported concussion or traumatic brain injury within 1 year before study entry. The inclusion criteria for the controls were male sex, age 40 to 69 years, no cognitive symptoms, and no history of traumatic brain injury. Descriptions of the exclusion criteria and information on the enrollment of participants, including those specific to the use of the flortaucipir PET radioligand, are provided in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org. The study builds on a phase 2a pilot study (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT02079766), the details of which are provided in the Supplementary Appendix.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Participants.*

| Characteristic | Former Players (N = 26) |

Controls (N = 31) |

|---|---|---|

| Age — yr | 57.0±8.4 | 60.3±6.0 |

| Black race — no. (%)† | 14 (54) | 6 (19) |

| Education — yr | 16.3±0.7 | 15.8±2.2 |

| MMSE score | 27.23±1.73 | 29.06±0.81 |

| Positive amyloid-beta scan — no. (%)‡ | 1 (4) | 2 (6)§ |

| Florbetapir SUVR | 0.96±0.07 | 0.97±0.09¶ |

| Years played in NFL | 9.1±3.0 | — |

| Total years played tackle football | 18.8±4.6 | — |

Plus–minus values are means ±SD. There was a significantly higher proportion of black participants in the former-player group than in the control group (P = 0.007). The former-player group had a significantly lower mean score on the Mini–Mental State Examination (MMSE; scores range from 0 to 30, with lower scores indicating greater cognitive impairment) than the control group (P<0.001). There were no other significant differences between the groups. NFL denotes National Football League.

Race was reported by the participant.

A positive scan was defined by a mean cerebral:cerebellar florbetapir standard uptake value ratio (SUVR) of at least 1.10, which corresponds to postmortem evidence of moderate-to-frequent amyloid-beta plaques.

Among the 10 controls from studies of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), 1 (10%) had a positive scan.

Among the 10 controls from studies of CTE, the mean SUVR was 0.94±0.07.

The 26 former NFL players were recruited through word of mouth, social media posts, and e-mail notifications. A total of 18 of the former players were participants in an investigator-initiated CTE study that was supported by Avid Radio-pharmaceuticals and the National Institutes of Health13,14 and was conducted at Boston University and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. The other 8 former players were consecutively enrolled in an associated investigator-initiated CTE study that used similar enrollment criteria, assessments, and imaging protocols, supported by Avid Radiopharmaceuticals and the State of Arizona, and was conducted at Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, and at Banner Alzheimer’s Institute, Phoenix.

The control group included 31 asymptomatic male research volunteers from four clinical research studies (details are provided in the Supplementary Appendix). Nine were consecutively enrolled control participants in the CTE study conducted in Boston, and 1 was in the associated CTE study conducted in Arizona. Data were also acquired from 21 additional controls, including 18 participants who were enrolled in previous Avid-sponsored Alzheimer’s disease case–control studies15 and 3 participants from Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative studies (ClinicalTrials.gov numbers, NCT01231971 and NCT01687153; http://adni.loni.usc.edu/data-samples/adni-data-inventory/). This group of additional controls included every participant from the four other studies who was male, was in the same age range as the former-player group, had a score of 29 or higher on the Mini–Mental State Examination (MMSE; scores range from 0 to 30, with lower scores indicating greater cognitive impairment),16 reported no history of traumatic brain injury, and, at the time of our image analysis, had available flortaucipir and florbetapir PET and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans obtained with the use of the same imaging protocols as those used for the former-player group. These participants were not asked about their participation in collision or contact sports. Participants in all control groups were selected without our knowledge of their flortaucipir PET findings.

The study procedures were approved by the relevant institutional review board at each study site, and participants provided written informed consent for participation in this study or, if they participated in one of the other studies, for their data to be shared and combined with data in other studies. Imaging studies and other assessments were performed for research purposes and at no cost to the research participants, who were not informed of the tau or amyloid-beta PET scan results. Avid Radiopharmaceuticals provided funding for the study and provided the PET ligands, and Avid investigators were involved in study design, data analysis, and preparation of the manuscript. There were no confidentiality agreements between the authors and Avid, any other commercial entity, or the NFL. The authors vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data and adverse-events reporting.

CLINICAL MEASURES

All participants were administered the MMSE16 as a measure of cognitive status and, in the case of the controls, as one of the screening criteria for inclusion in the studies from which they were drawn. The former NFL players were also administered neuropsychological tests and neuropsychiatric assessments as reported in a previous study.17 A subset of six tests of executive functioning (Trail Making Test Part B, Category [Animal] Fluency), episodic memory (Neuropsychological Assessment Battery List Learning Test), mood (Beck Depression Inventory II and Beck Hopelessness Scale), and behavioral regulation (Barratt Impulsiveness Scale) was used for the analyses, since these tests assess functions affected by CTE.6,7 (Detailed explanations of the scores are provided in Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix.)

BRAIN IMAGING

Each participant underwent flortaucipir PET (for the detection of tau), florbetapir PET (for the detection of amyloid-beta), and T1-weighted volumetric MRI of the head. Flortaucipir PET was performed on PET–computed tomography (CT) systems with an intravenous bolus of 370 MBq (10 mCi [±10%]) of flortaucipir and a CT scan to correct the PET scan for radiation attenuation and scatter. Dynamic emission PET data collected over a 20-minute period beginning 80 minutes after radiotracer administration were used for analysis in this study. Florbetapir PET was performed on the same systems with an intravenous injection of approximately 370 MBq (10 mCi) of florbetapir, a 50-minute radiotracer uptake period, a 10-minute dynamic emission scan, and a CT scan to correct the PET scan for radiation attenuation and scatter. As part of site qualification for participation in the study, a priori procedures were used to adjust scanner parameters to harmonize images across investigative sites. (Details are provided in the Supplementary Appendix.) All PET images were smoothed with an 8-mm gaussian kernel as a filter to harmonize images acquired on different PET–CT systems and to mitigate noise.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Between-group comparisons of age, years of education, and MMSE scores were analyzed with Mann–Whitney U tests. Group differences in race were analyzed with the use of chi-square tests. For between-group comparisons of amyloid-beta plaque burden, chi-square tests were used to compare the proportion of participants with a positive florbetapir PET, and t-tests were used to compare the mean cortical:cerebellar florbetapir standard uptake value ratio (SUVR, the ratio of radioactivity in a cerebral region to that in the cerebellum as a reference) between the groups. Because several of the controls from previous studies had negative florbetapir PET findings, these group comparison analyses for florbetapir were also conducted with the subset of 10 control participants enrolled in the CTE study, for whom the availability of florbetapir results was not an entry criterion.

For the initial analysis of flortaucipir PET images, automated brain-mapping algorithm software (Statistical Parametric Mapping, version 12 [SPM12] [www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/]) was used to coregister each participant’s flortaucipir PET image to his MRI, transform the coregistered images into the coordinates of a standard brain atlas, control for age, and generate statistical parametric maps of the between-group differences at each voxel in regional cerebral:cerebellar gray-matter flortaucipir SUVRs, with the use of a prespecified threshold of a P value less than 0.005, uncorrected for multiple comparisons, to select regions that differed between groups. Early analyses in this study used a qualitative ordinal scale and visual interpretation of scans. This method was replaced by the automated analysis. (Details are provided in the Supplementary Appendix.)

To address possible type I error in the examination of group differences in an entire voxel-based PET image, a post hoc Monte Carlo simulation procedure (see the Supplementary Appendix) was performed with 1000 iterations, testing the hypothesis that the number of flortaucipir SUVR differences observed in the postulated direction (i.e., SUVR higher in the former-player group than in the control group at P<0.005) was significantly greater than the number of voxels with elevations in the opposite direction (i.e., SUVR higher in the control group than in the former-player group).

The initial exploratory analysis was of voxel-based flortaucipir SUVR, which was used to create regional SUVR values for individual participants. These data were used to select voxels that had higher SUVR values in the former-player group than in the control group (with P<0.005 for the between-group difference) in clusters of at least 100 contiguous voxels and to characterize these regions as having either elevated or not-elevated values in order to identify regions of interest. Between-group differences in each of the resulting regional flortaucipir uptake values were examined by analysis of covariance, with age as the covariate.

Multivariate mixed-effect models were used to examine associations between the regional flortaucipir SUVRs and the six neuropsychological and neuropsychiatric measures. To reduce type I error and to account for possible nonnormality due to the small sample size, 95% confidence intervals and P values were calculated with the use of bias-corrected bootstrapping from 1000 resamples.

In post hoc analyses, partial correlations, controlling for age, were used to explore the extent to which regional flortaucipir SUVRs in the former-player group were associated with total years playing tackle football. In addition, to account for possible effects of outliers, post hoc Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated from the age-adjusted residuals.

Flortaucipir has off-target binding to melanocytes in the choroid plexus, such that flortaucipir PET measurements in the adjacent hippocampi are higher in black than in white research participants as a result of the effects of partial-volume averaging.18–21 Since there was a higher percentage of black participants in the former-player group than in the control group, a post hoc analysis with t-tests as well as nonparametric Mann–Whitney U tests was performed to examine racial differences in the regional flortaucipir SUVRs and determine whether these measurements were confounded by race.

For the analysis of florbetapir PET images, the mean cortical:cerebellar florbetapir SUVRs were generated from each participant’s florbetapir image with the use of SPM12 software and the above-described cerebral and whole cerebellar regions of interest. A positive amyloid-beta PET scan, corresponding to postmortem evidence of moderate-to-frequent neuritic plaques (consistent with a neuropathological diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease), was defined as an SUVR greater than or equal to 1.10, in accordance with previous prospective cohort studies.22

RESULTS

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE PARTICIPANTS

The former-player and control groups had similar mean ages and years of education (Table 1). There was a higher percentage of black participants and a lower mean MMSE score in the former-player group than in the control group (P<0.001 for both comparisons). The neuropsychological and neuropsychiatric test scores in the former-player group are shown in Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix.

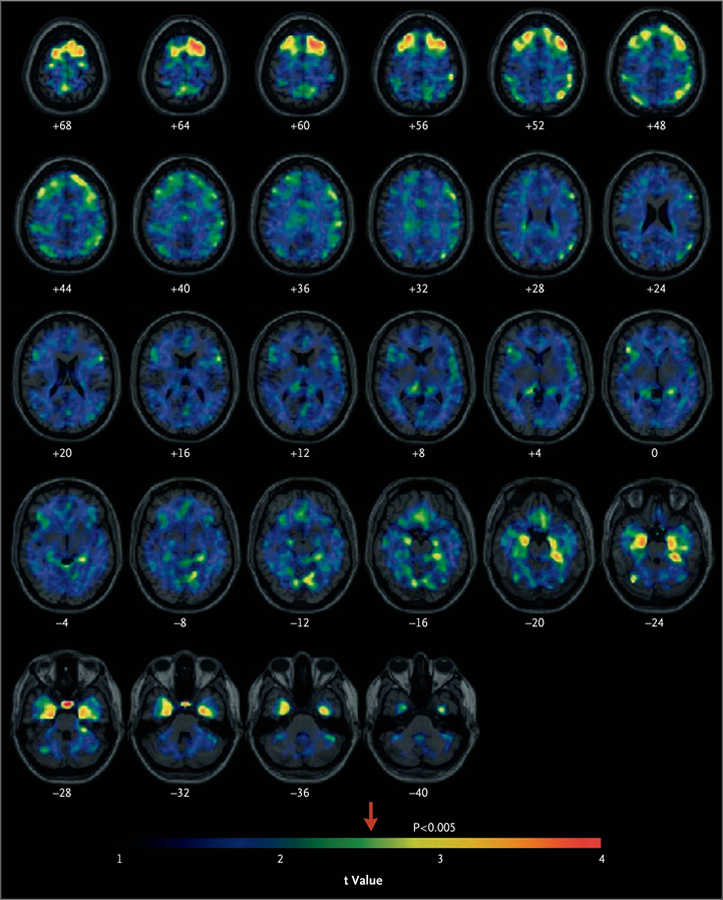

FLORTAUCIPIR PET MEASUREMENTS OF PAIRED HELICAL FILAMENT TAU BURDEN

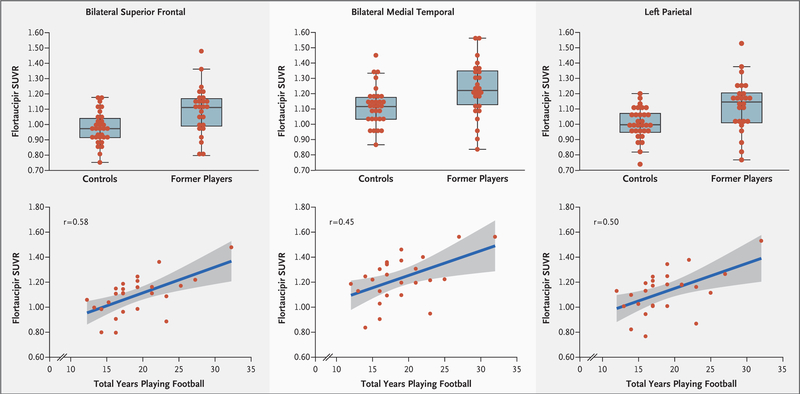

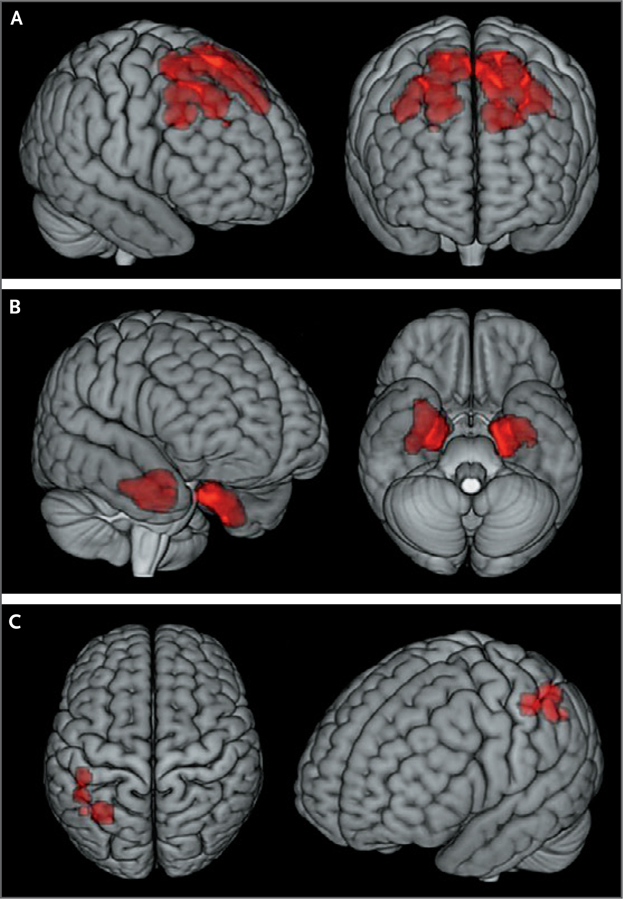

In the initial image analysis of differences at each voxel, the age-adjusted flortaucipir SUVRs indicated significantly higher uptake (P<0.005 for all comparisons in each region, uncorrected for multiple comparisons) in the former-player group than in the control group, primarily in the bilateral superior frontal, bilateral medial temporal, and left parietal regions (Fig. 1). The Monte Carlo simulation procedure resulted in corrected P values of less than 0.001 (see the Supplementary Appendix). Significantly higher flortaucipir SUVR values in clusters of greater than 100 contiguous voxels in the former-player group than in the control group were also found in the bilateral superior frontal, bilateral medial temporal, and left parietal regions (P<0.005 for all comparisons in each region). Table 2 summarizes the group differences in these regional SUVRs, and these results are shown in the surface projection maps in Figure 2, and in Figure S1 in the Supplementary Appendix. Box plots of the distributions of the regional flortaucipir SUVRs show that the overall group mean differences were significant, but individual measurements in the two groups were overlapping (Fig. 3, top). The flortaucipir SUVRs from the bilateral superior frontal, medial temporal, and left parietal regions did not differ significantly between the 14 self-identified black former players and the 11 self-identified white former players (P>0.05) (Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Figure 1. Statistical Parametric Maps of Flortaucipir Positron-Emission Tomography (PET).

The maps show voxels with higher regional:cerebellar gray-matter flortaucipir standard uptake value ratios (SUVRs) among former National Football League (NFL) players than among controls. The arrow indicates the point along the color gradient above which the differences between the groups, indicated by the t value, are significant (P<0.005, uncorrected for multiple regional comparisons). The numbers below each spatially standardized horizontal brain section correspond to the distance in millimeters above (positive numbers) or below (negative numbers) a plane through the anterior and posterior commissures. The left hemisphere is on the right.

Table 2.

Group Differences in Statistically Derived Regional Flortaucipir SUVRs.*

| Region | SUVR | Adjusted Mean Difference (95% CI) |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Former Players (N = 26) |

Controls (N = 31) |

|||

| Bilateral superior frontal | 1.090.16 | 0.980.10 | 0.13 (0.06–0.20) | <0.001 |

| Bilateral medial temporal | 1.230.18 | 1.120.13 | 0.13 (0.05–0.21) | <0.001 |

| Left parietal | 1.120.17 | 1.010.10 | 0.12 (0.05–0.20) | 0.002 |

Plus–minus values are means ±SD. SUVRs are based on individual analyses of covariance with age as covariate.

Figure 2. Three-Dimensional Stereotactic Surface Projection Maps of Flortaucipir PET.

Higher flortaucipir SUVRs in the former-player group than in the control group were found in the bilateral superior frontal (Panel A), bilateral medial temporal (Panel B), and left parietal (Panel C) regions of the brain. The regions shown in red in these surface projection images correspond to the statistical parametric maps after restriction of the map to those clusters of at least 100 contiguous voxels associated with higher regional:cerebellar gray-matter flortaucipir SUVRs in the former-player group than in the control group (P<0.005, uncorrected for multiple regional comparisons).

Figure 3. Statistical Evaluation of Regional Flortaucipir SUVRs.

The box plots in the top row show the distributions of statistically characterized regional SUVRs in 26 former NFL players and 31 controls in the bilateral superior frontal, bilateral medial temporal, and left parietal regions of the brain. The horizontal line in each box represents the median, the lower and upper boundaries of the boxes the interquartile range, and the ends of the I bars 1.5 times the interquartile range. The scatterplots in the bottom row show the relationship between regional flortaucipir SUVRs and total years playing tackle football. The gray-shaded areas in the bottom row represent the standard error of the regression line (blue). The r values are based on Spearman correlations of the residuals from age-adjusted partial correlations.

There were no significant associations of neuropsychological or neuropsychiatric test results with flortaucipir SUVRs in the three brain regions (Table S4 in Supplementary Appendix). In post hoc analyses of the former players’ total years of tackle football (including youth, high school, college, and professional levels of play), the correlation coefficients with flortaucipir SUVRs were 0.58 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.25 to 0.79), 0.45 (95% CI, 0.07 to 0.71), and 0.50 (95% CI, 0.14 to 0.74) for the bilateral superior frontal, bilateral medial temporal, and left parietal regions, respectively (Fig. 3, bottom).

FLORBETAPIR PET MEASUREMENTS OF AMYLOID-BETA PLAQUE BURDEN

The former-player and control groups did not differ significantly with respect to their mean cortical:cerebellar florbetapir SUVRs (former-player group mean, 0.96; control group mean, 0.97; mean difference, 0.01; 95% CI, −0.03 to 0.06). One symptomatic former player and two asymptomatic control participants had a positive amyloid-beta PET scan (Table 1), as defined by an SUVR score of 1.10 or greater (centiloid values, >24.3). When the analyses were restricted to the subset of 10 control participants who were enrolled in the CTE study, for whom there was no florbetapir-based entry criterion, the findings were similar (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

This descriptive study shows regional deposition of paired helical filament tau and a paucity of neuritic amyloid-beta plaque in living former NFL players who reported cognitive, mood, and behavioral symptoms, measured with the use of PET imaging of the brain. In comparison with asymptomatic control participants without a history of traumatic brain injury, symptomatic former NFL players had elevations in flortaucipir PET measurements of tau in the bilateral superior frontal, bilateral medial temporal, and left parietal regions, which have been shown to be affected in postmortem cases of neuropathologically diagnosed CTE.1,2

Although all the former NFL players in the study reported cognitive symptoms, and more than 35% had impaired delayed-recall scores on an objective memory test (Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix), they did not have a higher proportion of positive florbetapir PET scans or higher amounts of amyloid-beta deposition as measured by the florbetapir SUVR than the controls. These findings suggest that the cognitive difficulties reported by the former players were not related to Alzheimer’s disease amyloid-beta deposition. Although our study included a higher percentage of black participants in the former-player group than in the control group, the former players did not have higher flortaucipir SUVRs in the implicated medial temporal region.18–21

Previous reports have suggested an association between football-related exposure to repetitive head impacts and later-life neurologic consequences23 and between years of play and postmortem tau burden.8,13,14,24 In a post hoc analysis, we found correlation coefficients between 0.45 and 0.58 for the number of total years playing tackle football and the amount of tau deposition. However, there were no significant associations between regional flortaucipir uptake and neuropsychological and neuropsychiatric test scores. Because of the small sample size in our study and the patchy, focal distribution of tau deposition observed in postmortem studies of CTE,1,5 it is possible that our study had insufficient power to detect associations between flortaucipir uptake and the clinical measures. The exclusion of asymptomatic former NFL players from the study may have reduced the ability to detect a relationship between flortaucipir uptake and clinical features of CTE. It is also possible that paired helical filament tau pathology alone is not associated with the neuropsychiatric symptoms and cognitive impairment found in our sample of former NFL players.

Our study has limitations. Some of the analyses were post hoc. The comparisons were between groups, and the results do not inform the use of testing in individual patients to determine CTE pathology during life. The inclusion of a relatively homogeneous sample of former professional football players means that our findings may not be generalizable to amateur football players, other contact sport athletes, and nonathletes with a history of exposure to repetitive head impacts. The control group included participants from other studies with different recruitment criteria and without assessment of detailed history about previous involvement in contact or collision sports; it was known only that there was no history of traumatic brain injury. The cross-sectional design of our study precludes the ability to examine any changes in flortaucipir uptake over time. Replication studies with larger samples, with persons with a wider range of ages and degrees of cognitive and neuropsychiatric symptom severity, a control group with no history of exposure to repetitive head impacts, and a longitudinal design are required in order to clarify the value of flortaucipir PET in detecting tau in CTE. Validation of flortaucipir PET for the detection of CTE tau pathology will require postmortem neuropathological confirmation of in vivo PET findings. Although flortaucipir PET has been found to be a sensitive and specific tracer for tau species in Alzheimer’s disease,25,26 newer tracers that may have greater sensitivity, less nonspecific binding, more specificity to the molecular conformers that are unique to CTE,27 and an improved contrast:noise ratio are being developed and might help to improve our ability to detect and to track tau abnormalities in CTE.28

In conclusion, the group of living former NFL players with cognitive, mood, and behavioral symptoms who were examined in this study had elevated flortaucipir PET measurements in regions of the brain that were consistent with the distribution of tau in persons with CTE confirmed by postmortem examination.1,2 The former players did not have elevated amyloid-beta plaque deposition detected by florbetapir PET. Although this study showed between-group differences in flortaucipir PET measurements, our analyses do not pertain to detection of tau pathology in individual participants.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by an investigator-initiated grant from Avid Radiopharmaceuticals (a wholly owned subsidiary of Eli Lilly) to Boston University and by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01NS078337, U19AG024904, 1UL1TR001430, U01NS093334, P30AG19610, and P30AG13846), the State of Arizona, and the Department of Defense (W81XWH-13-2-0063, W81XWH-13-2-0064, and W81XWH-14-1-0462). All flortaucipir and florbetapir PET radiotracers were provided by Avid Radiopharmaceuticals.

We thank the participants and investigators who participated in this study; Robert Bauer, Yinghua Chen, and Vivek Devadas for their assistance in the analysis of PET data; Amy Duffy for participant recruitment and assessments at Mayo Clinic Arizona; Alicia Chua for assistance with data analysis and the production of the figures; and Gustavo Mercier for acquisition of PET data at the Boston University Medical Campus.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.McKee AC, Stern RA, Nowinski CJ, et al. The spectrum of disease in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Brain 2013; 136:43–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mez J, Daneshvar DH, Kiernan PT, et al. Clinicopathological evaluation of chronic traumatic encephalopathy in players of American football. JAMA 2017; 318:360–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bieniek KF, Ross OA, Cormier KA, et al. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy pathology in a neurodegenerative disorders brain bank. Acta Neuropathol 2015;130: 877–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ling H, Morris HR, Neal JW, et al. Mixed pathologies including chronic traumatic encephalopathy account for dementia in retired association football (soccer) players. Acta Neuropathol 2017; 133:337–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKee AC, Cairns NJ, Dickson DW, et al. The first NINDS/NIBIB consensus meeting to define neuropathological criteria for the diagnosis of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Acta Neuropathol 2016;131:75–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stern RA, Daneshvar DH, Baugh CM, et al. Clinical presentation of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Neurology 2013; 81:1122–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montenigro PH, Baugh CM, Daneshvar DH, et al. Clinical subtypes of chronic traumatic encephalopathy: literature review and proposed research diagnostic criteria for traumatic encephalopathy syndrome. Alzheimers Res Ther 2014;6:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alosco ML, Mez J, Tripodis Y, et al. Age of first exposure to tackle football and chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Ann Neurol 2018;83:886–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Congdon EE, Sigurdsson EM. Tau-targeting therapies for Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol 2018;14:399–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Villemagne VL, Doré V, Burnham SC, Masters CL, Rowe CC. Imaging tau and amyloid-β proteinopathies in Alzheimer disease and other conditions. Nat Rev Neurol 2018;14:225–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marquié M, Normandin MD, Meltzer AC, et al. Pathological correlations of [F-18]-AV-1451 imaging in non-Alzheimer tauopathies. Ann Neurol 2017;81:117–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dickstein DL, Pullman MY, Fernandez C, et al. Cerebral [18F]T807/AV1451 retention pattern in clinically probable CTE resembles pathognomonic distribution of CTE tauopathy. Transl Psychiatry 2016;6(9):e900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alosco ML, Tripodis Y, Fritts NG, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid tau, Aβ, and sTREM2 in former National Football League players: modeling the relationship between repetitive head impacts, microglial activation, and neurodegeneration. Alzheimers Dement 2018;14:1159–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alosco ML, Tripodis Y, Jarnagin J, et al. Repetitive head impact exposure and laterlife plasma total tau in former National Football League players. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2016;7:33–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pontecorvo MJ, Devous MD Sr, Navitsky M, et al. Relationships between flortaucipir PET tau binding and amyloid burden, clinical diagnosis, age and cognition. Brain 2017;140:748–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12: 189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alosco ML, Jarnagin J, Tripodis Y, et al. Olfactory function and associated clinical correlates in former National Football League players. J Neurotrauma 2017;34: 772–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee CM, Jacobs HIL, Marquié M, et al. 18F-flortaucipir binding in choroid plexus: related to race and hippocampus signal. J Alzheimers Dis 2018;62:1691–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lyoo CH, Cho H, Choi JY, Ryu YH, Lee MS. Tau positron emission tomography imaging in degenerative parkinsonisms. J Mov Disord 2018;11:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips JS, Das SR, McMillan CT, et al. Tau PET imaging predicts cognition in atypical variants of Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Brain Mapp 2018;39:691–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schonhaut DR, McMillan CT, Spina S, et al. 18F-flortaucipir tau positron emission tomography distinguishes established progressive supranuclear palsy from controls and Parkinson disease: a multicenter study. Ann Neurol 2017;82:622–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clark CM, Pontecorvo MJ, Beach TG, et al. Cerebral PET with florbetapir compared with neuropathology at autopsy for detection of neuritic amyloid-β plaques: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol 2012;11:669–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montenigro PH, Alosco ML, Martin BM, et al. Cumulative head impact exposure predicts later-life depression, apathy, executive dysfunction, and cognitive impairment in former high school and college football players. J Neurotrauma 2017; 34:328–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cherry JD, Tripodis Y, Alvarez VE, et al. Microglial neuroinflammation contributes to tau accumulation in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2016;4:112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith R, Wibom M, Pawlik D, Englund E, Hansson O. Correlation of in vivo [18F]flortaucipir with postmortem Alzheimer disease tau pathology. JAMA Neurol 2018. December 3 (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Ossenkoppele R, Rabinovici GD, Smith R, et al. Discriminative accuracy of [18F]flortaucipir positron emission tomography for Alzheimer disease vs other neurodegenerative disorders. JAMA 2018;320: 1151–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Falcon B, Zivanov J, Zhang W, et al. Novel tau filament fold in chronic traumatic encephalopathy encloses hydrophobic molecules. Nature 2019. March 20 (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Laforce R Jr, Soucy JP, Sellami L, et al. Molecular imaging in dementia: past, present, and future. Alzheimers Dement 2018;14:1522–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.