Abstract

The Origin Replication Complex (ORC), which is a multi-subunit protein complex composed of six proteins ORC1–6, is essential for initiating licensing at DNA replication origins. We have previously reported that ORC4 has an alternative function wherein it forms a cage surrounding the extruded chromatin in female meiosis and is required for polar body extrusion (PBE). As this is a highly unexpected finding for protein that normally binds DNA, we tested whether ORC4 can actually form larger, higher order structures, which would be necessary to form a cage-like structure. We generated two fluorescent constructs of mouse ORC4, mORC4-EGFP and mORC4-FlAsH, to examine its spatial dynamics during oocyte activation in live cells. We show that both constructs were primarily monomeric throughout the embryo but self-association into larger units was detected with both probes. However, mORC4-FlAsH clearly showed higher order self-association and unique spatial distribution while mORC4-EGFP failed to form large structures during Anaphase II. Interestingly, both variants were found in the pronuclei suggesting that its role in DNA licensing is still functional. Our results with both constructs support the prediction that ORC4 can form higher order structures in the cytoplasm, suggesting that it is possible to form a cage-like structure. The finding that FlAsH labeled ORC4 formed demonstrably larger higher order structures than ORC4-GFP suggests that ORC4 oligomerization is sensitive to the bulky addition of GFP at its carboxy terminus.

Keywords: ORC4, polar body extrusion, oocytes, embryos, fluorescence lifetime imaging, phasor analysis

Introduction

During division, cellular components must be produced and replicated to ensure cell identity within the daughter cell. DNA replication is facilitated by proteins that bind at specific locations within the chromosome termed origin sites [1–3]. The Origin Recognition Complex (ORC), which consist of six subunits, ORC1–6, serves a critical role during DNA replication as it identifies these replication origin sites, is the first to bind to DNA origin sites, and initiates formation of the licensing pre-replication complex (pre-RC) [4–6]. Licensing occurs at mitosis and G1 phase wherein the pre-RC recruits Mcm2–7 to the bound chromatin sites transitioning the origin site; the opening of the DNA double helix destabilizes and releases the ORC allowing for ORC binding to another origin site [7, 8].

The function of each individual ORC protein has been primarily linked to their involvement in DNA replication, however, non-DNA licensing activity has also been noted for the ORC proteins [9–13]. We have reported that ORC4, a 45 kDa protein that is predicted to contain a CDC6 superfamily domain, has a role outside of DNA licensing wherein the ORC4 protein forms a cage-like structure surrounding one set of chromosomes during meiotic divisions [5, 14]. DNA caged by ORC4 was observed to be expelled through polar body extrusion (PBE) and that disruption of the ORC4 self-association inhibited PBE [14]. To our knowledge, there have been no other reports of ORC4 forming a cytoplasmic cage than the two publications from our laboratory. Thus, we feel compelled to make every effort to rigorously test it. Interestingly, prevention of higher order self-association of the ORC4 complex did not prevent DNA replication suggesting it did not disrupt ORC4 DNA licensing [14]. This demonstrates that the two functions ascribed to ORC4 within embryos are not mutually exclusive and, thus, likely involve interactions within different regions of the protein. This non-DNA licensing activity reported for ORC4 and the other ORC proteins hints at the possibility that the ORC proteins may have critical, multifaceted roles within cells.

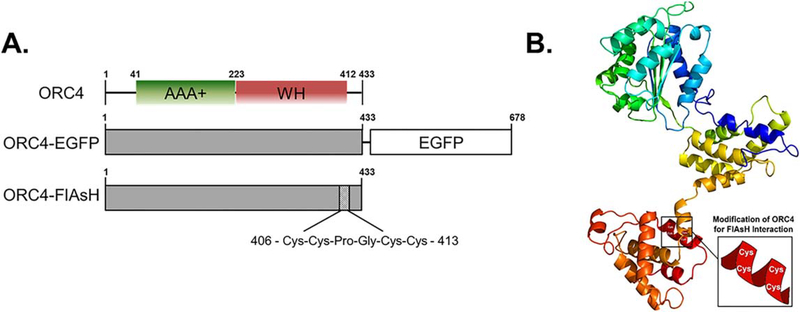

The formation of a cage-like structure would require that ORC4 forms oligomers, something that has never been reported before. We therefore tested whether ORC4 has the ability form higher order complexes at the molecular level using two different probes. We carried out advanced fluorescence microscopy on embryos expressing two newly generated mouse ORC4 (mORC4) fluorescent variants to visualize and quantify self-association during activation of embryos. The first was mORC4-EGFP which is a fusion protein containing enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) at the C-terminus of the mORC4 protein (figure 1). We chose this configuration because our previous studies suggested that the sites of mORC4 that were involved in higher order oligomerization were closer to the N-terminus. The second construct was mORC4 with a Fluorescein Arseninal Hairpin Binder (FlAsH) sequence (Cys-Cys-Pro-Gly-Cys-Cys) inserted into a C-terminal α-helix. The FlAsH sequence does not alter the three-dimensional structure of the protein but allows mORC4 to be selectively labeled with the fluorescent FlAsH compound [15, 16]. We provide compelling evidence that the mORC4-FlAsH variant can be recruited to the ORC4 cage during PBE and was consistently localized within polar bodies (PBs). Conversely, mORC4-EGFP emission was nearly homogenous throughout the embryo at all stages of activation, though evidence of higher order structures were still present. Our findings indicate that mORC4 protein has an intrinsic ability to self-associate, which is a requirement during PBE.

Figure 1.

Structural organization of mORC4 and fluorescent variants. (A) Schematic diagram showing the domain structure of mORC4 and predicated alterations associated with newly constructed fluorescent variants. (B) Predicted 3D structure of mORC4 containing the FlAsH sequence. Structure was predicted using Phyre2.

Materials and methods

Materials

All cell culture medium and buffers, along with mMESSAGE mMACHINE T7, were from Thermo-Fisher (Waltham, MA) unless otherwise stated. B6D2F1 (C57BL/6N X DBA/2) mice were from the National Cancer Institute (Raleigh, NC). Equine chorionic gonadotropin (eCG) and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) were from Millipore (Burlington, MA). Mouse ORC4 plasmid was from Geneocopiea (Rockville, MD). Primers used for the Gibson reaction were purchased from IDT (Coralville, IA). All restriction enzymes and Gibson Assembly Master Mix were purchased from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA). FlAsH-EDT2 was generously provided by Dr Nevin Lambert (Augusta University of Georgia, GA). Bovine testicular hyaluronidase and EDT were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Harvesting of oocytes

Mouse oocytes were collected as previously described [5]. Briefly, 8–10-week-old mice, were induced to superovulate by injections of 5 IU eCG and 5 IU hCG given 48 h apart. Oviducts were removed 14–15 h after the injections of hCG and placed in CZB free Ca+2. The oocyte-cumulus complex was released from the oviducts into 0.1% bovine testicular hyaluronidase/CZB medium for 10 min to disperse cumulus cells. The cumulus-free oocytes were washed and kept in CZB at 37 °C under 5% CO2 in air. Oocytes were activated for development via parthenogenesis activation by using CZB free calcium medium containing 10 mM of SrCl2 for two hours (AII) three hours (G1) when appropriate signal was observed. Animal care and experimental protocols for handling and treatment procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Hawai’i (UH Manoa IACUC 04–049-13 (WSW)).

Generating mORC4-EGFP and mORC4-FlAsH constructs

The essential regions required for higher order self-association of ORC4 for cage formation were identified at the N-terminus and within the middle domain (figure 1; [14]). The EGFP and FlAsH mORC4 were constructed using the Gibson method (Cat No. E2611S) with mouse ORC4 (mORC4) plasmid (Cat. No. EX-Mm19600-B31) and EGFP plasmid as templates. For ORC4-EGFP, primers used to amplify the EGFP sequence included homology arms at the beginning and at the end of the assembly vectors directed at the C-terminal region of our ORC4 plasmid (Forward: 5′- CCTCACTAAGCTGGCTGTACCATGGTGAG-CAAGGGCGA-3′; Reverse: 5′- GGTTATGCTAGT-TATTGCTCATTACTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATG-3′). For ORC4-FlAsH, primers were designed to create a construct containing the new amino acid sequence Cys-Cys-Pro-Gly-Cys-Cys within residues 407–412, which we had previously predicted to be within an alpha helix (1st Forward: 5′- TGCTGCCCAGGTTGCTGCAAA-TACTCCAACTGCCCTACAG-3′; 1st Reverse: 5′-TCCGGATATAGTTCCTCCTTTCA-3′; 2nd Forward: 5′- ATGCTATTGATGCTTGCTTTAAATC-3′; 2nd Reverse: 5′- GCAGCAACCTGGGCAGCATTGAG-TATTATCCAAAAGTAGTTTCACTA-3′). Correct insertion of each construct was confirmed by colony PCR and sequencing of plasmids.

mRNA synthesis and injection

Plasmids containing the mORC4-EGFP and mORC4-FlAsH constructs were linearized using the BlpI restriction enzyme (Cat. No. R0585S) downstream of the orc4 gene. mMESSAGE mMACHINE T7 transcription kit (Cat. No. AMB13455) was used to synthesize mRNA. Electrophoresis confirmed the production of the mRNA product, which was then isolated and stored at −20 °C prior to microinjection. Microinjection were performed on embryos at MII using a volume of 10 pl/oocyte for all experiments. Following microinjection, the embryos were incubated for at least 4 h and examined for EGFP signal under microscope or were treated with FlAsH-EDT2. To fluorescently label the mORC4 protein containing the C-terminal FlAsH sequence, embryos microinjected with mRNA-mORC4-FlAsH were incubated with FlAsH-EDT2 for 30 min. After 30 min, the embryos were washed three times with EDT + DMSO and PBS + glucose to remove unbound FlAsH.

Dynamics of fluorescent ORC4 in Oocytes

Confocal fluorescence measurements were recorded on an Alba fluorescence correlation spectrometer (ISS, Champaign, IL) connected to a Nikon TE2000-U inverted microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY) with a PlanApo VC 60 × 1.2 NA water objective [17, 18]. Embryos were imaged in a humidified enclosed chamber kept at 37 °C (Tokai Hit, Fujinomiya, Sizuoka, Japan). An objective heater wrapped round the neck of the objective was used to minimize temperature drifts (with a 20-min delay to equilibrate the temperature prior to imaging) and the collar of the objective was adjusted to compensate for temperature and thickness of the coverslip. Two-photon excitation of EGFP and FlAsH was provided by a Chameleon Ultra (Coherent, Santa Clara, CA) tuned to 920 nm with < 1 mM laser power. Fluorescence emission was collected through a bandpass filter (FF01–520/35; Semrock Rochester, NY) in front of a photo multiplier detector (H7422P-40, Hamamastu, Hamamastu City, Japan). Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM) measurements were recorded through an ISS A320 Fast FLIM box coupled to the Ti:Sapphire laser, which produces 80-fs pulses at a repetition rate of 80 MHz. Fluorescein, in 0.01 M NaOH, was used as the lifetime reference (4.0 ns). The fluorescent lifetime of mEGFP in solution, 0.01 HEPES, pH 7.5, was recorded for comparison to mORC4-EGFP [19]. Diffusion and concentration were determined for each mORC4 construct using Raster Imaging Correlation Spectroscopy (RICS) [20–22]. The beam waist (ω0) calibration was achieved by measuring the autocorrelation curve of fluorescein (~20 nM) in 0.01 M NaOH, and fitted with a diffusion rate of 430 μm2 s−1, which was performed before each day’s measurement. All microscopy data were analyzed using SimFCS 4.0 (E. Gratton, University of California Irvine, CA) with lifetimes being analyzed using phasor plots [23–25].

Results

mORC4-EGFP shows no spatial structural cage formation

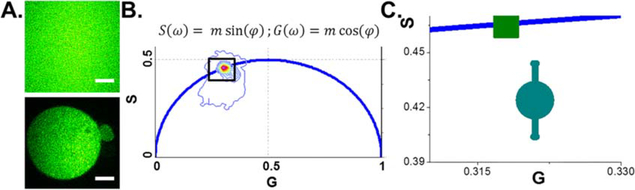

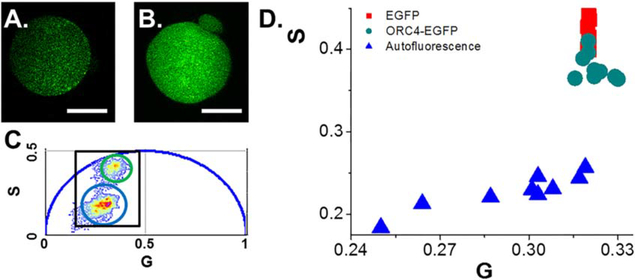

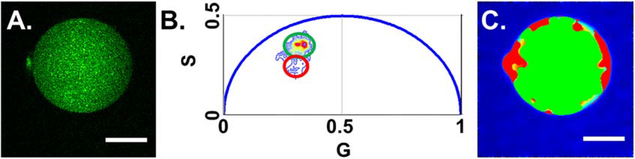

Embryos injected with mRNA-EGFP, which severed as our positive control for protein production, showed homogenous fluorescence throughout each region of imaged embryos (figure 2(A)). FLIM-phasor analysis of these samples produced points that coincide with phasor points from EGFP in solution indicating that the fluorescence recorded from our injected embryos is from EGFP (figures 2(B) and (C)). Comparison between intensity images of embryos injected with mRNA of mORC4-EGFP and EGFP revealed minimal differences (figures 3(A) and (B)). The distribution of phasor points for mORC4-EGFP were located near the EGFP points yet were slightly shifted further inside the universal circle, (figures 3(C) and (D)). This movement of phasor points indicates contribution of autofluorescence within our recorded fluorescence (~15%−20%), which is evident as nearly all mORC4-EGFP phasor plots contained pixels near the autofluorescence region (figures 3(C) and (D)). Interestingly, the phasor points highlighting PBs from mORC4-EGFP injected embryos were consistently (~60%) found within the autofluorescence region indicating minimal trafficking of mORC4-EGFP to the PBs (figure 4).

Figure 2.

Embryos injected with mRNA-EGFP show similar phasor points as EGFP in solution. (A) Intensity images of EGFP in solution (Top) and EGFP expressed in embryo (AII). Scale bar is 15 microns. (B) Phasor plot containing points associated with EGFP in solution and EGFP in embryos. The equations used to generate the phasor plot are shown above where ω is the frequency, m is the modulation, and φ is the phase angle. (C) Inset from (B) highlighting the similar phasor location between EGFP in solution (green) and EGFP (cyan) in embryos.

Figure 3.

mORC4-EGFP has similar phasor location as EGFP and minimal higher order self-association in embryos. Representative intensity images of non-injected embryos (A) and mORC4-EGFP mRNA injected embryos (B). Scale bar is 15 microns. (C). Phasor plot showing the location for autofluorescence (blue circle) and mORC4-EGFP (green). (D). Inset from (C) highlighting the average phasor location for autofluorescence (blue), EGFP in embryos (red), and mORC4-EGFP (green).

Figure 4.

FLIM-phasor demonstrates minimal amount of mORC4-EGFP entering the PB. (A) Intensity image of mORC4-EGFP expressed in embryo (AII). Scale bar is 15 microns. (B) Phasor plot from embryo injected with mORC4-EGFP mRNA (A). The green circle correlates with phasor points for mORC4-EGFP while the red points are nearly overlapping with phasor points associated with autofluorescence. (C) Spatial organization of the phasor points from (B) overlaid onto image (A). The mORC4-EGFP phasor points (green) are found located primarily within the cell body while the phasor points attributed to autofluorescence (red) are located within the areas near the PB. Scale bar is 15 microns.

Fluctuation analysis was used to characterize the dynamics of our labeled proteins throughout the embryo (table 1). The correlation traces and calculated diffusion values for mORC4-EGFP samples were similar to the estimated diffusion (~6.3 μm2 s−1) based on the mass of mORC4 and EGFP [26]. This implies that the majority of the protein is likely monomeric and untethered to slow moving structures. Visual inspection of the collected frames and correlation traces, however, indicated that the diffusion might be more complex as we observed some areas containing large fluorescent spots (figure 5). Analysis of regions containing these spots produced diffusion values that were ~10 × slower than regions containing no spots (table 1; figure 5). These data suggest that there are two populations of mORC4-EGFP in the cytoplasm, a rapidly moving, untethered population and another one that is self-associated and moving more slowly. However, we were unable to observe large self-association, like cage formation, from the fluorescence signal during PB formation and FLIM-phasor analysis did not identify spatially resolved structures for mORC4-EGFP. These experiments therefore suggested that while mORC4-EGFP is capable of self-aggregation, this fusion protein cannot form larger structures necessary to form a cage.

Table 1.

Fluctuation analysis of fluorescent variants of mORC4 in embryos.

| Injected RNAa | Ave. Diffusion (μm2 s−1)b | Diffusion 1 (μm2 s−1) | Diffusion 2 (μm2 s−1) | Concentration (nM)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGFP | 9.5 ± 1.0 | N/A | N/A | 120 ± 20 |

| mORC4-EGFP | 5.0 ± 0.5 | 7.5 ± 1.0 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 40 ± 10 |

| mORC4-FlAsH | 6.0 ± 1.0 | 7.0 ± 0.8 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 160 ± 50 |

For each condition, n = 10.

Values were calculated using SimFCS to fit correlation functions.

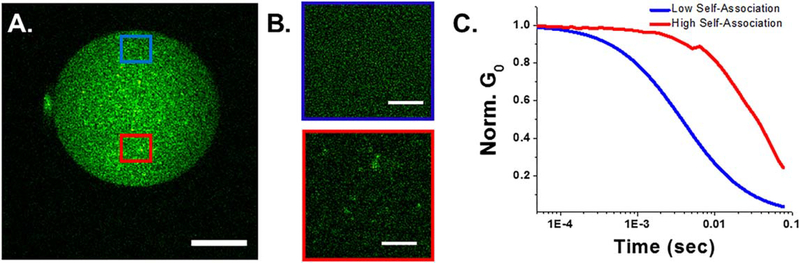

Figure 5.

Fluctuation analysis demonstrates mORC4-EGFP self-association in embryos. (A) Intensity image of mORC4-EGFP expressed in embryo (AII) (n = 10 cells). Scale bar is 15 microns. (B) Intensity images with the pixel size set to 50 nm for regions of A with minimal self-association (blue) and mORC4-EGFP self-association (red). Scale bar is 3 microns. (C) Autocorrelation functions for the fast (blue) and slow (red) diffusing species. G0 was normalized to demonstrate the shift between each region.

FlAsH labeled mORC4 shows distinct spatial clustering similar to cage formation

The lack of mORC4 cage appearance from our EGFP fusion construct suggests that this modification may have limited mORC4’s ability to self-associate. We therefore generated and characterized the properties of mORC4 labeled with FlAsH within embryos as an alternative to a fusion mORC4 protein (figure 1). Intensity images and FLIM-phasor analysis from embryos treated with FlAsH-EDT2, but not injected with mRNA, produced higher fluorescence than untreated embryos, and had a phasor distribution similar to unbound fluorophore (figure 6). This indicated that our washing protocol was not fully effective at removing non-specific bound FlAsH-EDT2; however, we were unable to modify the current protocol due to the sensitivity of the embryos to the wash conditions. Regardless of this possible contaminating signal, the embryos injected with mORC4-FlAsH were found to have greater fluorescence intensity than the controls and showed distinct emission patterns that were not observed under other conditions (figure 6(B)). Phasor analysis of these samples produced points that were shifted away from the non-specific bound phasor points. These results are in line with previous reports that observed modified fluorescent properties of this fluorophore when bound to the FlAsH sequence [15]. Therefore, the use of FLIM-phasor analysis allowed us to resolve non-specific versus specific binding of FlAsH-EDT2 within the embryos. We also note that phasor analysis of mORC4-FlAsH indicated a reduction in recorded autofluorescence compared to mORC4-EGFP.

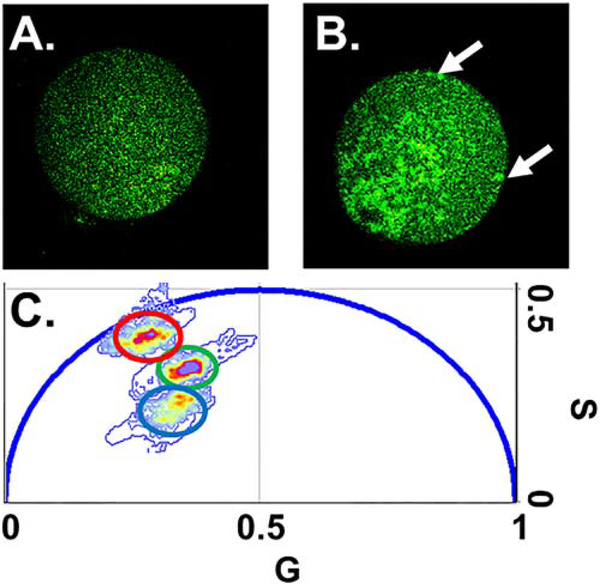

Figure 6.

mORC4-FlAsH images demonstrate unique structural organizations and pattering on the plasma membrane. Representative intensity images with FlAsH treated embryos (AII) with no mRNA injected (A) and mORC4-FlAsH mRNA injected (B). White arrows on (B) highlight unique clustering that was observed with mORC4-FlAsH injected embryos. Scale bar is 15 microns. (B). Phasor plot showing the location of a representative for autofluorescence (blue circle), FlAsH with no mRNA injected (red circle), and FlAsH in mORC4-FlAsH mRNA injected embryos (green circle).

Intensity images of mORC4-FlAsH (figure 6(B)) showed non-homogenous emission distribution throughout the embryo, unlike mORC4-EGFP, with intensity patterns also being observed in the PB. Images appeared to have bright decorations along the plasma membrane, distinct circular or cage like structures near the plasma membrane during PBE, and high number of FlAsH phasor pixels within the PB (figure 6). Fluctuation analysis produced nearly identical diffusion properties as our mORC4-EGFP construct yet the concentration of mORC4-FlAsH was found to be higher than the EGFP variant from our sampled embryos (table 1). This variation might be caused from alterations in the actual amount of mRNA injected into each oocyte or might indicate alterations in protein production/degradation for each construct.

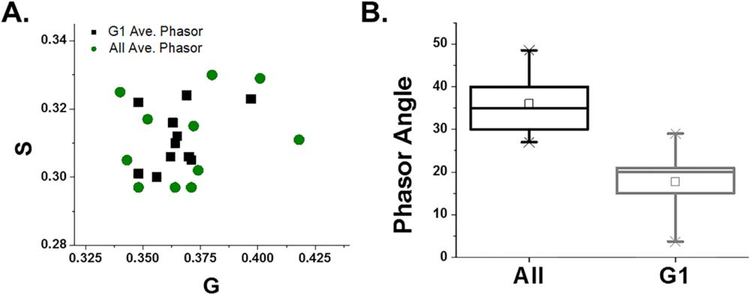

mORC4-EGFP and mORC4-FlAsH are both found within the pronuclei

Our goal is to accurately record the dynamics of mORC4, in a live cell system, during each assigned function. Therefore, we needed to ensure that a modified variant is still able to license DNA. FLIM imaging of embryos injected with mORC4-EGFP and mORC4-FlAsH were recorded at zygotic G1 stage to examine alterations in mORC4 distribution and if we could spatially resolve the mORC4 constructs within the pronucleus (PN). Analysis of the phasor points during G1 and Anaphase II (AII) yielded striking differences (table 2). The average phasor location, from both variants, was nearly identical and indicates no major changes in location at different stages of embryo activation (figure 7(A)). However, the angle of the phasor distribution at G1 was noted to be shifted by ~20–30 degrees compared to AII with both mORC4 constructs (table 2; figure 7(B)). The ratio of a/b was also found to be increased in these samples indicating an increase in the ellipse phasor area. Selection of the phasor points along this angle at G1, which had a trajectory towards the universal circle, highlighted pixels corresponding to the PN within the embryos (figure 8). Interestingly, within mORC4-FlAsH injected embryos selection of these points also highlighted regions around the plasma membrane (figure 8). These results are indicative that both constructs not being excluded from the PN and that licensing from both variants likely still occurs.

Table 2.

Phasor point distribution of fluorescent variants of mORC4 in embryos at different activation stages.

| Injected protein(s)a | Phasor angleb | Major axis (a)b | Minor axis (b)b | Ratio (a/b) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORC4-EGFP (AII) | 75 ± 5 | 0.47 ± 0.07 | 0.20 ± 0.02 | 2.3 ± 0.3 |

| ORC4-EGFP (G1) | 49 ± 4 | 1.00 ± 0.10 | 0.18 ± 0.03 | 5.6 ± 1.0c |

| ORC4-FlAsH (AII) | 18 ± 5 | 0.43 ± 0.10 | 0.17 ± 0.05 | 2.5 ± 0.4 |

| ORC4-FlAsH (G1) | 36 ± 8 | 0.73 ± 0.10 | 0.10 ± 0.04 | 7.3 ± 2.0c |

For each condition, n = 10.

Calculated using SimFCS as described previously [27].

p < 0.05 from a student t test where identical mRNA injections were compared between activation states.

Figure 7.

mORC4-FlAsH phasor point analysis reveals distinct differences between AII and G1 embryos. (A) Average phasor distribution of mORC4-FlAsH from embryos at AII (black) and G1 (Green). (B) Box and whisker plot of the phasor angle of mORC4-FlAsH at AII and G1.

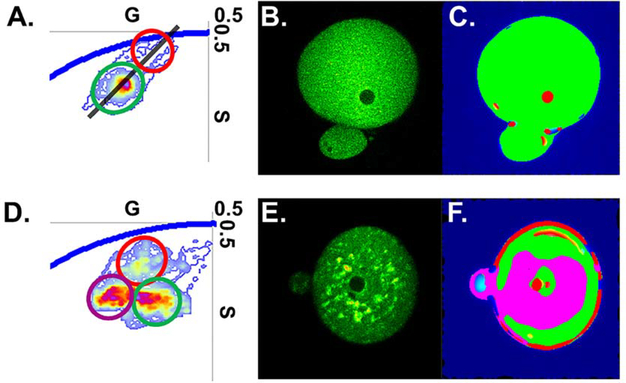

Figure 8.

mORC4 fluorescent variants demonstrate altered phasor point locations within the PN and when bound to the plasma membrane. (A) Representative phasor plot of mORC4-EGFP in G1 embryos. The black line highlights the calculated angle of phasor distribution. Peaks identified along the phasor angle were selected using green and red circles, respectively. (B) and (C) Representative intensity image of G1 embryos expressing mORC4-EGFP and an overlay of highlighted phasor points, from (A), onto G1 image (B). (D) Representative phasor plot of mORC4-FlAsH in G1 embryos. Peaks identified within the phasor distribution were selected using different colored circles. (E) and (F) Representative intensity image of G1 embryos expressing mORC4-FlAsH and an overlay of highlighted phasor points, from (D), onto G1 image (E).

Discussion

We quantitatively measured the distribution and dynamics of two mORC4 variants within activated oocytes using fluctuation and lifetime microscopy. The data strongly support the surprising predition from our earlier work [5, 14] that ORC4 can oligomerize in the cytoplasm, a necessary ability to form a cage like structure. Both fluorescent labeled forms of ORC4, the mORC4-EGFP and the mORC4-FlAsH, showed evidence of self-aggregation, but the mORC4-FlAsH was much more efficient and formed much larger structures. This suggests that the addition of EGFP to ORC4 significantly reduced the efficiency of oligomerization, which would not be surprising. The main focus of this work, however, was to use advanced fluorescent techniques to determine whether ORC4 could oligomerize, and we have now shown that it can. This supports the finding that the DNA binding protein can have a separate function under certain conditions.

Fluorescence methodologies have advanced significantly over the past decade with several new approaches that can allow for the examination of target molecules down to the single molecule level with low nanometer resolution [16, 28–30]. Researchers have also utilized advance fluorescence microscopy techniques as a means to capture and quantitatively describe molecular dynamics associated with live embryo development [31–34]. For example, Plachta’s group developed a fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) method, which they termed photo-activation with FCS (paFCS), which was used to track the diffusion of the transcription factor Oct4 during embryo differentiation [31]. The sensitivity of fluorescence methodologies therefore allows quantification of dynamics in live cells and tissues, including live embryos, without causing major perturbations to the system. We therefore sought to develop a biological active fluorescent variant of mORC4 as a means of reporting its trafficking during PBE aiming to address: (1) does modification of mORC4 at the C-terminus, with EGFP or the FlAsH sequence, alter its activity? and (2) could we observe cage formation and PBE with either of these constructs?

The distribution of mORC4 during embryo maturation has been previously examined by immunocytochemistry [14]. These data suggested that mORC4 polymerizes to form a cage around the chromosomes that will be expelled in PB during both meiotic AI and AII. Based on this model, we hypothesized that mORC4 should undergo a large redistribution to the nucleus during AI and AII which should be accompanied by a decrease in the diffusion and increased local concentration of mORC4 near DNA to be extruded. Consistent with this model, both mORC4-EGFP and mORC4-FlAsH were quantified as having diffusion rates indicative of a fast (likely monomer) and a slow (oligomerized) species (table 1; figure 5). This observation is an essential finding as it provides strong evidence for self-association as an intrinsic property for mORC4 protein. Images from mORC4-FlAsH embryos demonstrated distinct patterns of mORC4 were indicating that this variant could be segregated to unique areas of the embryo (figure 6). Rather unusual was the lack of spatial resolution of higher order self-associated mORC4-EGFP as previous data indicated no reduction in ORC activity with EGFP labeling [13, 35, 36]. Furthermore, mORC4-EGFP seemed to be excluded from within the PB as ~40% of cells examined contained phasor points from EGFP within the PB (figures 3 and 4). These results are in agreement and are indicative that this variant has minimal, if any, support for chromosome selection nor is involved in PBE. To explain this, we hypothesize that the addition of EGFP at the C-termini introduces steric hindrance on higher order mORC4 structure formation thus preventing this variant from being tightly associated for cage formation during chromosome selection or PBE. This model would also address the lack of significant modifications of the mORC4-FlAsH variant, which would cause minimal alterations in structure or energy of interaction, thereby allowing for it to be integrated with endogenous protein during activity.

The role of ORC4 during DNA replication has been well established by several laboratories [4,6–8]. We provided evidence that ORC4 with our previous data indicating that mORC4 moves from the cage surrounding the polar body nucleus after PBE into the polar nucleus just before DNA replication [5, 14]. Thus any fluorescent variant utilized for studying mORC4 dynamics must be recruited to PN for DNA licensing. We interrogated the spatial organization of our constructs, using FLIM-phasor analysis, at different points during embryo maturation to see if these modified mORC4 constructs could be found within the PN (figures 7 and 8). Phasor points corresponding to mORC4-EGFP and mORC4-FlAsH were spatially resolved within the PN demonstrating that both variants could be activated for DNA replication. However, the points from both variants were segregated away from the points found inside the embryo (figures 8(A) and (B)). Phasor point differences observed for both EGFP and FlAsH indicates that the environment around the fluorescent molecule, which can be inferred to mORC4 as well, is not identical when located between the PN and embryo. Also, the phasor points that spatially and temporally resolve for the PN was also found to highlight regions around the plasma membrane (PM) (figures 8(C) and (F)). FLIM-phasor analysis establishes that not only can both constructs enter the PN but the forces acting upon mORC4 within the embryo are not identical to when bound to the PM or within the PN. This indicates that the protein requirements for mORC4 binding to the plasma membrane or complex formation during licensing within the PN are likely different.

Conclusion

This work demonstrates that mORC4 intrinsically can self-associate but the addition of a large polypeptide to the C-termini negatively impacts higher order self-association of mORC4, specifically affecting structured organization required for cage formation, and mORC4 activity in PBE. Our ultimate goal is to use single particle tracking and nano-imaging to provide a detailed molecular mechanism of mORC4 dynamics beginning with activation of the oocyte up to cell division. Fluorescent tracking of mORC4 will, therefore, require the use of constructs that do not significantly alter the mass of the protein to ensure the dual functions assigned to mORC4, PBE and DNA licensing, are not altered during embryo maturation. Herein we describe a possible mORC4 construct, namely mORC4 with a FlAsH sequence Cys-Cys-Pro-Gly-Cys-Cys inserted into an α-helix (figure 1), which allows for site-specific labeling and minimal background signal from nonspecific binding within live embryos. This work also represents the first step towards establishing a transgenic mouse model expressing endogenous levels of a trackable variant ofmORC4.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by NIH GM123048–01A1 (W S W) Dr James was supported in part by NIH GM113134–01A1 (M G). We kindly thank Dr David M Jameson for the use of his confocal microscope and insightful discussion regarding experimental design and manuscript preparation. The authors would also like to thank Thien Nguyen and Brandon Nguyen for their assistance during data collection.

Footnotes

Competing financial interests

The authors note that there is no competing interest regarding this research.

Data availability

The authors will make available all data and materials. Interested parties should contact N G J (njames4@ hawaii.edu) to make requests.

References

- [1].Aoki E and Schultz RM 1999. DNA replication in the 1-cell mouse embryo: stimulatory effect of histone acetylation Zygote. 7 165–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Sonneville R, Querenet M, Craig A, Gartner A and Blow JJ 2012. The dynamics of replication licensing in live Caenorhabditis elegans embryos J Cell Biol 196 233–46 PMCID: 3265957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Yeeles JT, Deegan TD, Janska A, Early A and Diffley JF 2015. Regulated eukaryotic DNA replication origin firing with purified proteins Nature 519 431–5 PMCID: 4874468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ortega MA, Nguyen H and Ward WS 2016. ORC proteins in the mammalian zygote Cell Tissue Res. 363 195–200 PMCID: 4703507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Nguyen H, Ortega MA, Ko M, Marh J and Ward WS2015 ORC4 surrounds extruded chromatin in female meiosis J Cell Biochem. 116 778–86 PMCID: 4355034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].DePamphilis ML 2003. The ‘ORC cycle’: a novel pathway for regulating eukaryotic DNA replication Gene. 310 1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Barlow JH and Nussenzweig A 2014. Replication initiation and genome instability: a crossroads for DNA and RNA synthesis Cell Mol Life Sci. 71 4545–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Eward KL et al. 2004. DNA replication licensing in somatic and germ cells J Cell Sci. 117 5875–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bicknell LS et al. 2011. Mutations in ORC1, encoding the largest subunit of the origin recognition complex, cause microcephalic primordial dwarfism resembling Meier-Gorlin syndrome Nat. Genet 43 350–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Lee KY, Bang SW, Yoon SW, Lee SH, Yoon JB and Hwang DS 2012. Phosphorylation of ORC2 protein dissociates origin recognition complex from chromatin and replication origins J Biol Chem. 287 11891–8 PMCID: 3320937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Cappuccio I et al. 2010. The origin recognition complex subunit, ORC3, is developmentally regulated and supports the expression of biochemical markers of neuronal maturation in cultured cerebellar granule cells Brain Res. 1358 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Quintana DG, Hou Z, Thome KC, Hendricks M, Saha P and Dutta A 1997. Identification ofHsORC4, a member of the human origin of replication recognition complex J Biol Chem. 272 28247–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Balasov M, Huijbregts RP and Chesnokov I 2009. Functional analysis of an Orc6 mutant in Drosophila Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106 10672–7 PMCID: 2705598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Nguyen H et al. 2017. Higher order oligomerization of the licensing ORC4 protein is required for polar body extrusion in murine meiosis J Cell Biochem. 118 2941–9 PMCID: 5509474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Adams SR and Tsien RY 2008. Preparation of the membrane-permeant biarsenicals FlAsH-EDT2 and ReAsH-EDT2 for fluorescent labeling of tetracysteine-tagged proteins Nat Protoc. 3 1527–34 PMCID: 2843588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Jameson DM, James NG and Albanesi JP 2013. Fluorescence fluctuation spectroscopy approaches to the study of receptors in live cells Methods Enzymol 519 87–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Byers CE et al. 2015. Enhancement of dynamin polymerization and GTPase activity by Arc/Arg3.1 Biochim Biophys Acta. 1850 1310–8 PMCID: 4398645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Goo B, Sanstrum BJ, Holden DZY, Yu Y and James NG 2018. Arc/Arg3.1 has an activity-regulated interaction with PICK1 that results in altered spatial dynamics Sci. Rep 8 14675 PMCID: 6168463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Stringari C, Nourse JL, Flanagan LA and Gratton E 2012. Phasor fluorescence lifetime microscopy of free and protein-bound NADH reveals neural stem cell differentiation potential PLoS One. 7 e48014 PMCID: 3489895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].James NG et al. 2014. A mutation associated with centronuclear myopathy enhances the size and stability of dynamin 2 complexes in cells Biochim Biophys Acta. 1840 315–21 PMCID: 3859711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rossow MJ, Sasaki JM, Digman MA and Gratton E 2010. Raster image correlation spectroscopy in live cells Nat Protoc. 5 1761–74 PMCID: 3089972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Digman MA and Gratton E 2009. Analysis of diffusion and binding in cells using the RICS approach Microsc Res Tech. 72 323–32 PMCID:4364519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].James NG, Ross JA, Stefl M and Jameson DM2011 Applications of phasor plots to in vitro protein studies Anal Biochem. 410 70–6 PMCID: 3021620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Stefl M, James NG, Ross JA and Jameson DM2011 Applications of phasors to in vitro time-resolved fluorescence measurements Anal Biochem. 410 62–9 PMCID: 3065364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Digman MA, Caiolfa VR, Zamai M and Gratton E 2008. The phasor approach to fluorescence lifetime imaging analysis Biophys. J 94 L14–6 PMCID:2157251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Edward JT. Molecular volumes and the Stokes-Einstein equation. J. Chem. Educ. 1970;47:261. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ranjit S, Dvornikov A, Levi M, Furgeson S and Gratton E 2016. Characterizing fibrosis in UUO mice model using multiparametric analysis of phasor distribution from FLIM images Biomed Opt Express 7 3519–30 PMCID: 5030029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Cardarelli F and Gratton E 2016. Spatiotemporal fluorescence correlation spectroscopy of inert tracers: a journey within cells, one molecule at a time Perspectives on Fluorescence ed Jameson DM (Berlin: Springer; ) p 287–309 [Google Scholar]

- [29].di Rienzo C, Gratton E, Beltram F and Cardarelli F 2016. Super-Resolution in a standard microscope: from fast fluorescence imaging to molecular diffusion laws in live cells Super-Resolution Imaging in Biomedicine ed A Diaspro and M A M J van Zandvoort 1st edn (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; ) p19–A3 [Google Scholar]

- [30].Bag N and Wohland T 2014. Imaging fluorescence fluctuation spectroscopy: new tools for quantitative bioimaging Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem 65 225–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kaur G. et al. Probing transcription factor diffusion dynamics in the living mammalian embryo with photoactivatable fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1637. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].White MD et al. 2016. Long-lived binding of Sox2 to DNA predicts cell fate in the four-cell mouse embryo Cell 165 75–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Plachta N, Bollenbach T, Pease S, Fraser SE and Pantazis P 2011. Oct4 kinetics predict cell lineage patterning in the early mammalian embryo Nat. Cell Biol 13 117–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Xenopoulos P, Nowotschin S and Hadjantonakis AK 2012. Live imaging fluorescent proteins in early mouse embryos Methods Enzymol. 506 361–89 PMCID: 4955835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Baldinger T and Gossen M 2009. Binding of drosophila ORC proteins to anaphase chromosomes requires cessation of mitotic cyclin-dependent kinase activity Mol Cell Biol. 29 140–9 PMCID: 2612480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Duncker BP, Chesnokov IN and McConkey BJ 2009. The origin recognition complex protein family Genome Biol. 10 214 PMCID: 2690993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]