Abstract

Objective

This study examined variability in autism symptom trajectories in toddlers referred for possible autism spectrum disorder (ASD) who had frequent observations from 14 to 36 months of age.

Method

In total, 912 observations of the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) were obtained from 149 children (103 with ASD) followed from 14 to 36 months of age. As a follow-up to a previous analysis of ADOS algorithm scores, a different analytic approach (Proc Traj) was implemented to identify several courses of symptom trajectories using ADOS Calibrated Severity Scores in a larger sample. Proc Traj is a statistical method that clusters individuals into separate groups based on different growth trajectories. Changes in symptom severity based on individual ADOS items also were examined.

Results

Trajectory analysis of overall symptom severity identified 4 clusters (non-spectrum ~25%; worsening ~27%; moderately-improving ~25%; severe-persistent ~23%). Trajectory clusters varied significantly in the proportions of confirmatory ASD diagnosis, level of baseline and final verbal and nonverbal abilities, and symptom severity. For the moderately-improving group, social communication improved, whereas restricted and repetitive behaviors were stable over time. Language and verbal and nonverbal communication improved for many children, but several social affect and restricted and repetitive behavior symptoms remained stable or worsened.

Conclusion

Significant variability in symptom trajectories was observed among toddlers referred for possible ASD. Changes in social and restricted and repetitive behavior domain scores did not always co-occur. Similarly, item-level trajectories did not always align with trajectories of overall severity scores. These findings highlight the importance of monitoring individual symptoms within broader symptom domains when conducting repeated assessments for young children with suspected ASD.

Keywords: autism spectrum disorder, symptom trajectories, toddlers, Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule

Behavioral studies have consistently shown that symptoms of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) can emerge by the second year of life1–6 and that the diagnosis of ASD at or before 3 years of age is stable over time.3,7–9 Despite this knowledge, studies examining trajectories of overall symptom severity during the early years are limited. A few studies have reported variability in patterns of onset and trajectories of core autism symptoms and for other nonverbal and verbal abilities.1,2,4 For example, studies from the Baby Siblings Research Consortium1,2,4,10 found that core symptoms of ASD began to manifest at 18 to 24 months of age in up to half the children later diagnosed with ASD (often characterized as the “early-onset” group), whereas other children did not show sufficient symptoms to receive a diagnosis of ASD until 3 years of age (often characterized as the “late-onset” or “worsening [in symptom severity]” group). Another study reported that approximately 20% of clinic-referred toddlers later diagnosed with ASD showed subthreshold levels of ASD symptoms before 3 years of age. However, by 3 years of age, children exhibiting late onset of symptoms and children whose symptoms were apparent before 2 years showed comparable symptom severity.3 Studies found that children showing the late-onset patterns were more likely to have higher verbal and nonverbal abilities and/or better adaptive skills early in life,1,3,5,11 which could indicate that the onset patterns and symptom trajectories are linked to specific developmental profiles.

Despite increased recognition of the importance of longitudinal, prospective studies of young children with ASD to examine the course of symptoms over development,12,13 studies have been limited to infrequent observations of symptom severity in children with ASD over the course of the first 3 years of life (observations occurring every 6–12 months).1–4,9,10 Frequent observations allow us to identify changes in symptom trajectory during developmental periods when behavioral changes are occurring rapidly. Recognizing this need, Lord et al.14 examined the trajectory of overall autism symptom severity based on algorithm scores from the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS)15 in 78 infants and toddlers assessed approximately every 2 months at 18 to 36 months of age. This study identified 4 different classes of children showing distinct trajectories over time: severe-persistent (21%), worsening (21%), improving (19%), and non-spectrum (40%). Another larger study of toddlers and preschoolers 1 to 4 years old (N = 203) with less frequent observations (3 observations at intervals of 9–36 months) implemented a similar analytic approach with ADOS algorithm totals and found 5 subsets of children showing different symptom trajectories, with 3 stable and 2 improving groups.16 These findings highlight that although most children with ASD demonstrate high stability in symptoms at different severity levels, a significant minority of children might show worsening or improvements in symptom severity over time.

Most of these studies examining changes in core symptoms of ASD used total scores from the ADOS diagnostic algorithms.1,3,5,14–16 Use of the raw algorithm totals from the ADOS in those studies did not take into account the fact that children move from lower to higher modules on the ADOS as their language skills improve over time. An exception was 1 study that statistically controlled for the module change.14 Thus, interpretations of these studies warrant caution because ADOS raw algorithm totals across different modules might not be directly comparable.17 In addition, notable effects of age and language level on the ADOS algorithm totals have been reported.17–20 To allow for valid comparison of scores across different modules, Calibrated Severity Scores (CSSs) based on the ADOS algorithm totals were developed.17 More recently, separate CSSs were created for the Social Affect (SA) and Restricted and Repetitive Behaviors (RRB) domains.21,22 The CSSs were created to show more uniform distributions across different age- and language-based developmental groups23 and were less influenced by participant characteristics than the algorithm totals.17,21 Therefore, to take into account that some children move from lower to higher modules on the ADOS as they develop more language, the present study used the ADOS-CSS to examine symptom trajectories in young children with ASD from the first to third year of life.

Studies have found that some children with ASD show improvements in language and adaptive communication skills from the first to third year of life, despite high stability in overall autism symptom severity.3,24 It also has been reported that specific skills and symptoms (eg, eye contact, social smiling, play, and language) can worsen during the first year of life in a subset of at-risk siblings later diagnosed with ASD, potentially showing a pattern of regression.25,26 Another study of younger siblings of children with ASD also found different trajectories of severity for initiation of join attention and shared positive affect at 1 to 3 years of age.2 Within children showing earlier versus later onset of overall ASD symptoms, distinct trajectories and onset patterns for these symptoms emerged, although the level of shared affect was not distinguishable at the younger ages between those 2 groups. This suggests that although children might show similar trajectories for broad symptom domains, patterns of changes in individual symptoms can vary, which highlights the need to examine changes in severity at the individual symptom level in more depth.

The present study aimed to identify clusters of toddlers referred for possible ASD who showed different patterns of overall symptom trajectories. Lord et al.14 reported on trajectories of overall symptoms using ADOS algorithm totals in a subset of the present sample. The present study used the ADOS-CSS and individual items in a larger sample using a different analytic technique, thereby allowing examination of changes in symptom severity over time while minimizing the effects of developmental factors such as age and language levels. This study also explored whether developmental characteristics differentiate these clusters and examined the variability in individual item trajectories within each cluster.

METHOD

Participants and Procedure

In total, 912 observations were obtained from 149 children (119 boys) referred for possible ASD beginning at a mean age of 18 months (SD 3.8; range 14–30) and followed to a mean age of 31 months (SD 5.7; range 15–36). All children were referred for evaluation to the University of Michigan Autism and the Communication Disorders Center or the Center for Autism and the Developing Brain at Weill Cornell Medicine because of concerns for ASD. As presented in Table 1, 34% of these children had an older sibling diagnosed with ASD. Of 149 children, 104 children received a confirmatory diagnosis of ASD at approximately 3 years of age (see Best-Estimate Diagnosis). Six other children received a diagnosis of ASD during at least 1 of their assessments at 1 to 3 years but not at their final evaluation. All children were seen at least twice (mean 6 times, SD 4.0; range 2–21). On average, participants were administered the ADOS every 2.5 months (SD 1.9). All children received the Toddler Module at baseline. Most children who were minimally verbal at follow-up were assessed using the ADOS Toddler Module (if <31 months old; n = 46) or Module 1 (if >31 months old; n = 45); as their language skills advanced, 39% of children (n = 58) transitioned to Module 2 at an average age of 30 months (SD 3.5). Sixty-one children (41%) had been included in the previous trajectory analysis of ADOS algorithm totals.14 The non-spectrum group had the largest proportion of younger siblings with ASD who tended to be referred at slightly younger ages than those who did not have older siblings with ASD. Additional sample descriptions are presented in Table 1; maternal education (n = 9), sibling status (n = 7), and race (n = 5) were not available for a small number of children. Seventy-eight percent of children were identified as white, 12% as mixed race, 4% as African American, and 2% as Asian.

TABLE 1.

Sample Characteristics for 4 Trajectory Groups

| Group 1 Non-spectrum (n = 37) | Group 2 Worsening (n = 40) | Group 3 Moderately-Improving (n = 38) | Group 4 Severe-Persistent (n = 34) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys, % | 70 | 88 | 74 | 88 |

| Race, % | ||||

| White | 88 | 75 | 82 | 78 |

| African American | 6 | 5 | 8 | 16 |

| Others | 6 | 20 | 10 | 6 |

| Younger sibling of child with ASD, % | 54 | 31 | 28 | 31 |

| Final diagnosis, %* | ||||

| ASD | 8 | 75 | 97 | 100 |

| Non-spectrum | 32 | 20 | 3 | 0 |

| TD | 60 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Maternal education, % | ||||

| College or professional/graduate degree | 77 | 77 | 53 | 61 |

| High school degree or some college | 23 | 23 | 47 | 39 |

| Intervention, %* | ||||

| >10 h/wk | 65 | 75 | 82 | 91 |

| ≤10 h | 35 | 25 | 18 | 6 |

| Module change* | ||||

| Transitioned to Module 2 | 51 | 55 | 24 | 18 |

| Remained at Toddler/Module 1 | 49 | 45 | 76 | 82 |

| Baseline chronologic age* | 16.8 (3.3)a | 18.1 (3.4)a,d | 20.1 (4.0)b,d | 20.1 (3.6)b,c |

| Final chronologic age* | 28.0 (6.8)a | 32.0 (4.7)b | 32.1 (5.1)b,c,d | 32.6 (4.5)b,d |

| Baseline cognitive evaluation (MSEL) | ||||

| Verbal IQ* | 83.8 (24.3)a | 75.3 (19.1)a,d | 62.8 (20.5)b,d | 52.4 (27.0)c |

| Nonverbal IQ* | 106.4 (17.0)a | 101.1 (16.6)a | 90.3 (17.4)b,d | 83.1 (19.7)c,d |

| Final cognitive evaluation (MSEL) | ||||

| Verbal IQ* | 105.0 (21.6)a | 92.1 (23.4)a | 74.5 (27.6)b | 48.7 (22.9)c |

| Nonverbal IQ* | 110.4 (19.5)a | 98.4 (22.1)a,b | 87.4 (23.2)b | 74.7 (16.9)c |

| Baseline ADOS evaluation | ||||

| CSS-SA subtotal* | 3.5 (1.7)a | 5.3 (1.9)b | 7.6 (1.8)c | 8.6 (1.7)c,d |

| CSS-RRB subtotal* | 4.7 (1.6)a | 5.5 (2.1)a,b | 6.1 (1.5)b | 7.6 (1.5)c |

| Final ADOS evaluation | ||||

| CSS-SA subtotal* | 2.9 (1.4)a | 5.8 (2.1)b | 6.6 (1.4)c,b | 8.6 (1.2)d |

| CSS-RRB subtotal* | 4.3 (2.0)a | 6.4 (2.1)b | 7.0 (1.9)c,b | 8.6 (1.4)d |

| Baseline adaptive functioning (VABS-2) | ||||

| Socialization | 86.6 (7.3)a | 84.9 (11.4)a,c | 83.7 (9.0)a,d | 78.6 (10.2)b,c,d |

| Communication* | 83.5 (11.2)a | 81.8 (14.6)a | 74.3 (11.3)a’c | 69.2 (17.7)b,c |

| Daily Living* | 90.1 (11.4)a | 86.1 (10.5)a,c | 88.4 (11.6)a | 78.7 (13.8)b,c |

| Final adaptive functioning (VABS-2) | ||||

| Socialization* | 96.4 (11.5)a | 80.7 (12.4)b | 87.6 (10.7)a,b | 72.3 (10.1)b,c |

| Communication* | 100.2 (11.4)a | 93.0 (11.6)a,b | 91.7 (17.6)a,b | 69.4 (8.9)b |

| Daily Living* | 95.8 (17.5)a | 91.0 (10.1)a | 91.9 (12.2)a | 75.2 (7.4)b |

Note: ADOS = Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule; ASD = autism spectrum disorder; CSS = Calibrated Severity Score; MSEL = Mullen Scales of Early Learning; RRB = Restricted and Repetitive Behaviors; SA = Social Affect; TD = typically developing; VABS-2 = Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale, 2nd edition.

Cells that have different superscript letters denote that those are significantly different from each other based on post hoc analyses with Bonferroni corrections.

Significant differences emerged among groups (p < .05).

Measures

Autism Symptom Severity

Symptom severity was quantified using the ADOS-CSS for the overall total and SA (CSS-SA) and RRB (CSS-RRB) domains. CSSs range from 1 to 10, with higher scores indicating greater severity. Because the RRB domain algorithm score on the ADOS is limited to a range of 9 points (0–8), it was not possible to use all 10 points in the severity metric for this domain. Therefore, the CSS-RRB metric was mapped from 1 to 10, with no intermediate scores from 1 to 5. Severity for specific symptoms was quantified using ADOS item scores. Item scores ranged from 0 (absence of abnormality specified) to 3 (abnormality clearly present). The full range of 0 to 3 was maintained to capture changes at the highest severity levels. Analyses using collapsed scores of 2 and 3 (as is the convention when computing the algorithm) yielded similar patterns of changes (data available on request). Rather than examining all individual items on the ADOS Toddler Module and Modules 1 and 2, analyses focused on algorithm items, reflecting symptoms found to best differentiate children with ASD from non-ASD comparison groups.20 When codes for individual items varied by ADOS module, items were recoded to allow comparison across different modules (eg, overall level of language, frequency of vocalizations, gestures; additional information available on request). ASD versus non-ASD groups showed statistically significant differences on all recoded items (p < .05), suggesting score transformations maintained the discriminant validity of each item. For items available only in the Toddler Module and/or Module 1 (ie, frequency of vocalizations, integration of gaze, ignore, requesting, amount of social overtures to caregivers), analyses were limited to the scores available on those modules.

Cognitive and Developmental Skills

Cognitive and developmental skills were measured by the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL) administered at baseline and at the final assessment.27 If the child’s baseline or final ADOS assessment was not accompanied by an MSEL score, then scores from the closest assessment (within 6 months) were used. Averaged Visual Reception and Fine Motor domain scores and Expressive Language and Receptive Language domain scores were used to derive nonverbal and verbal ratio IQ, respectively.

Adaptive Functioning

Adaptive functioning in areas of communication, daily living skills, and socialization was examined using standard scores from the parent interview of the second edition of the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale.28

Best-Estimate Diagnosis

Each child’s baseline evaluation included the toddler version of the Autism Diagnostic Interview–Revised (ADI-R),29 the ADOS, and the MSEL; a preliminary best-estimate diagnosis was given based on all available information. The ADOS was readministered as closely as possible on a monthly basis. The ADOS and MSEL were readministered every 6 months by an assessor blind to the child’s previous assessment results. Children were seen by the same clinician for most of their monthly visits because of the potential stress on parents coming in frequently to see a different clinician at every visit. Every 6 months each child was evaluated by an independent clinician who had not met the child before and who had no knowledge of the child’s previous performance and earlier diagnoses. Two clinicians, including one who had not carried out ongoing work with the child, made a consensus diagnosis. Because of scheduling issues or clinical needs, some children’s diagnostic assessment occurred after their 36-month ADOS visit; to ensure accuracy of diagnostic data, the most recent diagnosis available was used (mean age at diagnosis 39.5 months [SD 18]). The final diagnostic decision was based on clinician observation (eg, ADOS), parent-reported developmental history and current symptoms (eg, ADI-R), previous summary reports, recent monthly diagnoses, certainty ratings, psychometric and diagnostic algorithm scores, and videotaped observations of the child. Non-spectrum participants did not meet the DSM-5 criteria of ASD30 but had a range of diagnoses, including language disorders, general developmental delays, and intellectual disability. Typically developing children did not meet any diagnostic criteria for ASD or other disorders. All examiners achieved standard research reliability before administering the ADOS and ADI-R; ADOS reliability was maintained through regular (≥1 in 5 administrations) consensus coding with a second rater (exact item agreement range 70–100%, mean 85 for ADOS, all intraclass correlation coefficients > 0.91).

Analyses

Proc Traj31 was used to identify trajectory clusters of CCSs. Lord et al.14 reported on trajectories of overall symptoms using ADOS algorithm totals in a subset of the present sample based on the generalized linear latent and mixed model. Similar to the generalized linear latent and mixed model, Proc Traj is based on latent class growth analysis, which allows for different groups of individual growth trajectories to vary around different means using latent trajectory classes (ie, categorical latent variables). Latent class growth analysis assumes that variance and covariance estimates for the growth factors within each class are fixed to 0 such that all individual growth trajectories within a class are homogeneous.32 Latent class growth analysis was performed on a larger sample (n = 149; including 61 participants from the previous study14) with more observations to identify different trajectory classes based on overall CSSs. In contrast to the previous study,14 which used raw algorithm totals, this approach decreases the effects of developmental factors on changes in scores over time. Proc Traj uses a maximum likelihood method to estimate parameters, including group sizes and shapes of trajectories33; therefore, subjects with missing data were included in the analysis, but only available data for each subject were used. Based on visual inspection of the distribution of CSSs and preliminary analyses, the model was based on an assumption of a normal distribution. The trajectories were allowed to vary in their intercept (level at the mean age of the sample) and linear and quadratic slopes with respect to time. In accord with standard guidelines, the Bayesian information criterion was used to determine the ideal number of clusters and the slope.34,35 The posterior group probabilities were calculated for each subject based on the estimated parameters, and the subject was assigned to a group based on the subject’s highest posterior group probability. The average group probability was 80% (SD 18%, range 50–100%). Analyses of variance and χ2 analyses were performed to examine significant differences in baseline and/or final demographic and developmental factors among the overall trajectory clusters and post hoc contrasts among the 4 groups were performed for the 6 pairwise comparisons for each variable. For comparison with previous studies, trajectories of raw algorithm totals were examined for the clusters identified based on CSSs.17,21 Then, we examined how CSS-SA and CSS-RRB trajectories and trajectories of individual ADOS items varied across the 4 overall symptom severity clusters. For these analyses, scores from the ADOS diagnostic algorithm items were visualized and examined using R ggplot with a spline function to minimize noise in the data.36 Linear mixed models were used to evaluate changes in CSSs and item scores.

RESULTS

Overall CSS Trajectories and Cluster Characteristics

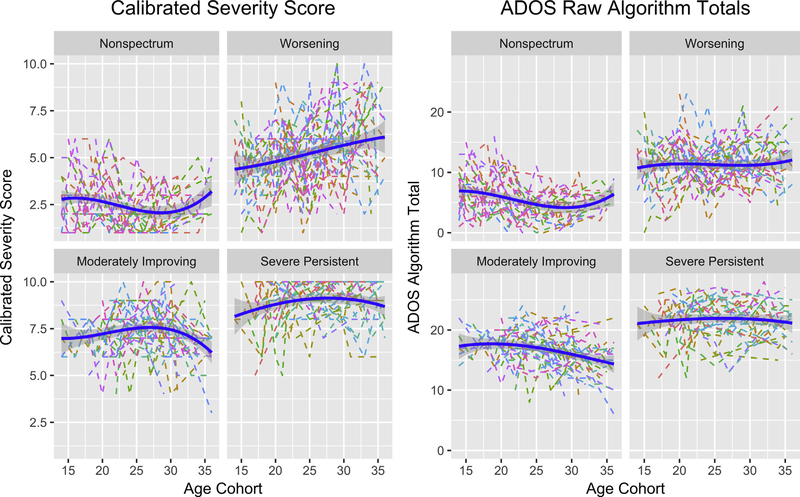

The trajectory analysis identified 4 clusters with a quadratic slope model; the Bayesian information criterion decreased from −2,066, −1,879, −1,796, and −1,793 from 1 to 4 clusters and increased from −1,793 to −1,790 from the quadratic to linear slope model. Participants were fairly equally distributed across the 4r clusters (non-spectrum ~25%; worsening ~27%; moderately-improving ~25%; severe-persistent ~23%; Figure 1). As expected, the trajectory groups showed significant differences in baseline and final ADOS-CSS (p < .001; Table 1). The non-spectrum and worsening groups initially showed less severe symptoms. The non-spectrum group maintained low CSSs over time, whereas the worsening group demonstrated a significant increase in overall CSSs (p < .01). The moderately-improving group exhibited a marginal decrease in overall symptom levels from 28 to 36 months (p = .08). For the severe-persistent group, symptoms emerged early and remained high over time (p not significant).

FIGURE 1. Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) Calibrated Severity Score and Algorithm Trajectories for 4 Empirically Derived Groups at 12 to 36 Months of Age Identified Based on Overall Calibrated Severity Score.

Note: Group 1 = non-spectrum; group 2 = worsening; group 3 = moderately-improving; group 4 = severe-persistent. Blue lines indicate fitted mean trends and gray areas indicate CIs. Trajectories for individual children are indicated by dotted lines. Please note color figures are available online.

Children with confirmatory ASD diagnoses were more likely to belong to the worsening, moderately-improving, and severe-persistent clusters (71%, 97%, and 97%, respectively) than the non-spectrum cluster (8%; χ23 = 68.458, p < .001). Children who developed phrase speech by 3 years (and thus moved from the Toddler Module to ADOS Module 2) were more likely to belong to the non-spectrum and worsening clusters (50% for both) than the other 2 clusters (17–28%; χ23 = 17.052, p < .01). At baseline and final evaluations, the 4 clusters varied significantly in nonverbal and verbal IQ scores (p < .001). Nonverbal IQ scores were stable for all groups (p not significant). In contrast, a group-by-age interaction emerged for verbal IQ scores (p < .05); verbal IQ scores improved for the non-spectrum, worsening, and moderately-improving groups but remained stable for the severe-persistent group. Children whose most recent full-scale IQ score was in the below-average range (<84; compared with those with average to above-average full-scale IQ > 85) also were more likely to belong to the moderately-improving and severe-persistent clusters (88–93%) than the non-spectrum and worsening groups (42–50%; χ23 = 198.251, p < .001). Clusters did not differ in proportions of boys, at-risk status (ie, sibling of an older child with ASD), or level of maternal education (with the lowest p value at .07 for maternal education). Moderately-improving, severe-persistent, and worsening clusters were more likely to receive more intensive intervention (>10 hours/week; 29–30%) than the non-spectrum cluster (12%; χ23 = 33.887, p < .001).

Raw Domain Score Trajectories within Overall CSS Clusters

Because many previous studies examining trajectories in symptom severity used the ADOS algorithm raw totals, we also examined the trajectories of these clusters using the raw algorithm totals. As shown in Figure 1, the patterns of trajectories based on raw algorithm totals replicate, with a larger sample, previous results reported with a subset (n = 61) of these participants.14 However, the trajectories of the ADOS algorithm raw totals did not align completely with the trajectories of the ADOS-CSS. Notably, the worsening cluster showed rather stable symptom severity on the ADOS algorithm totals (p = .268).

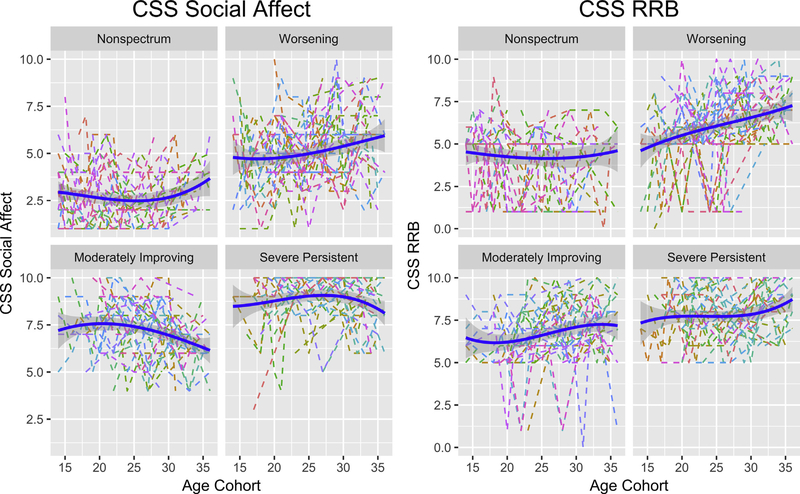

Trajectories of CSS-SA and CSS-RRB within Overall CSS Clusters

As shown in Figure 2, domain trajectories based on the CSS-SA and CSS-RRB varied across the 4 clusters identified using the overall ADOS-CSS. The moderately-improving group showed a statistically significant decrease (improvement) in SA symptoms (p < .0001), whereas scores for the RRB domain were stable over time for this group (p not significant). The worsening group showed statistically significant increases in scores (worsening symptoms) for the CSS-SA (p = .004) and CSS-RRB (p = .003).

FIGURE 2. Trajectories of Calibrated Severity Score (CSS) for the Social Affect and Repetitive and Restrictive Behaviors (RRB) Domains for the 4 Clusters Identified Based on Overall CSS.

Note: Please note color figures are available online.

Individual Symptom Trajectories within Overall CSS Clusters

Trajectories of ADOS algorithm items were examined across the 4 trajectory clusters and divided into 4 patterns: items that improved over time across most clusters, items that were stable over time for children with ASD, items that improved only for the moderately-improving group, and items that worsened only for the worsening group (but not always for the other groups).

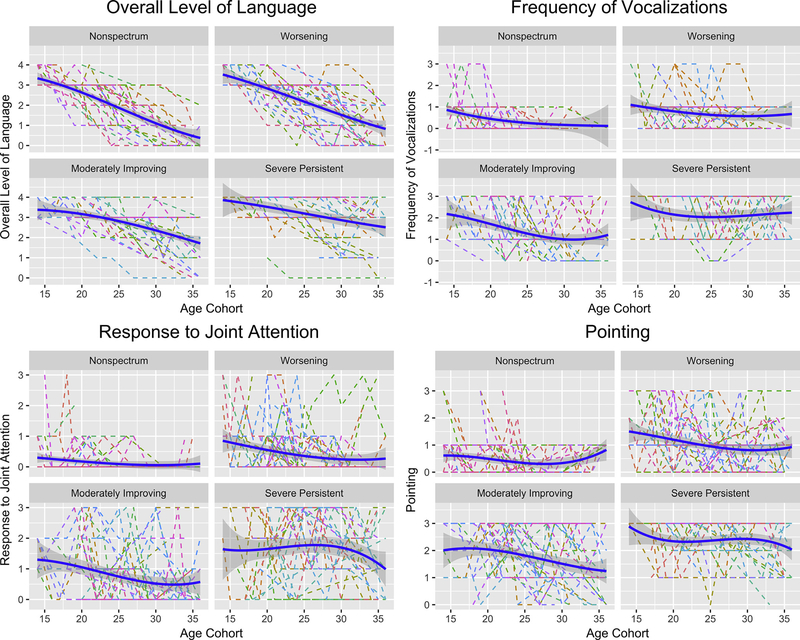

Items That Improved over Time across Most Clusters

As shown in Figure 3, across all 4 groups, overall level of language exhibited the most dramatic improvement over time. Other items such as frequency of vocalization, pointing, and response to joint attention also showed improvements of 0.3 to 1.5 points over time for all trajectory clusters; improvements were significant for all clusters (p < .05), with only a few exceptions (ie, the worsening group [pointing] and non-spectrum and severe-persistent groups [response to joint attention] did not show improvements for these items, potentially because of the floor effect for the non-spectrum group).

FIGURE 3. Items That Improved Over Time Across All Clusters.

Note: Please note color figures are available online.

Items That Were Stable over Time for Children with ASD

Impairments in many social communication behaviors (eg, quality of social overtures, unusual eye contact, and facial expressions) and some RRBs (eg, hand and finger and other complex mannerisms) emerged early on for the 3 clusters of children with ASD (Figure S1, available online), and trajectories indicated fairly stable symptom levels across groups over time.

Items That Improved over Time for the Moderately-Improving Group

Several items (ie, showing, ignore, response to name) showed significant decreases in symptom level for the moderately-improving group (p < .05). Quality of rapport also showed marginally significant decreases in symptom levels (p = .07). In contrast, greater variability in symptom trajectories was observed for the other groups. See Figure S2, available online, for the trajectories of these items.

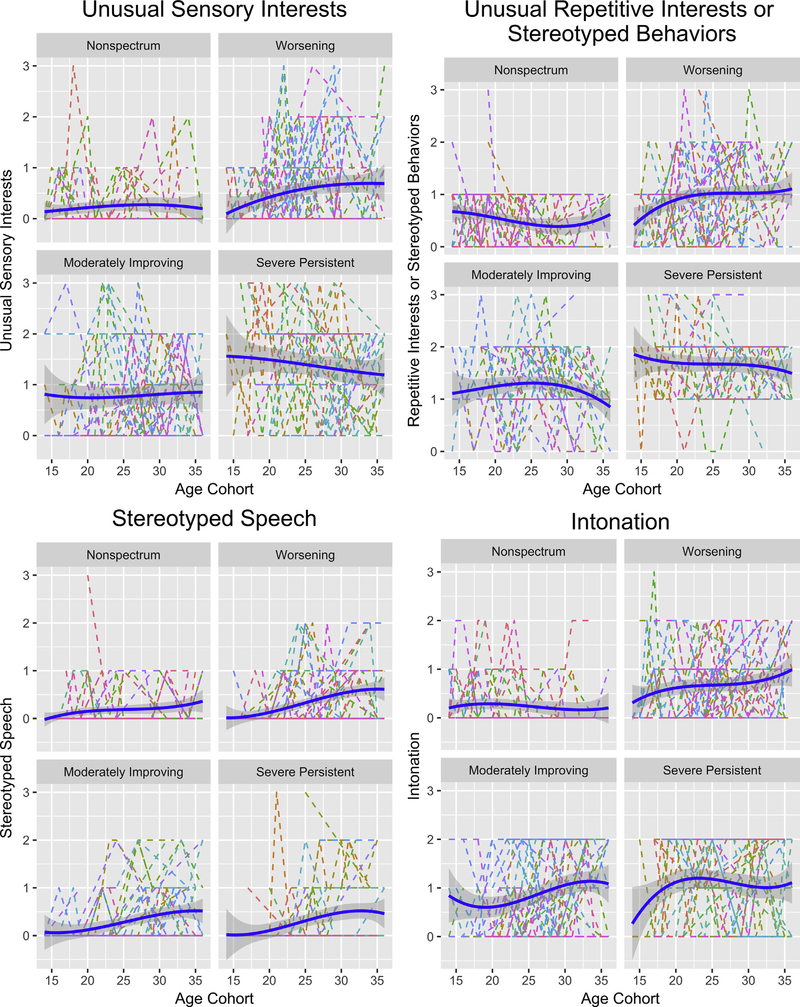

Items That Worsened Over Time for the Worsening Group

As shown in Figure 4, children in the worsening group showed trends for increases in symptom levels beginning as young as 15 months (but varying in duration), potentially because of smaller samples up to 15 months of age (5 and 7 children were evaluated at 13 and 14 months), for some RRB items, including repetitive interests and stereotyped behaviors (15–20 months; p < .05) and stereotyped speech (gradually over 15–35 months; p = .08). Other items (eg, unusual sensory interests and intonation) also showed possible trends toward worsening in symptoms that were less clear.

FIGURE 4. Items That Worsened Over Time for the Worsening Group.

Note: Please note color figures are available online.

DISCUSSION

In accordance with past studies,1,2,4 significant variability in the trajectories of ASD symptom severity was observed in the present sample of 149 infants and toddlers referred for possible ASD. Based on frequent observations of ASD symptom severity quantified by the ADOS-CSS, we identified 4 clusters of children who showed different patterns of overall symptom trajectories from 1 to 3 years of age. Twenty-three percent of the sample was classified as exhibiting a relatively stable, severe level of symptoms, whereas 25% exhibited moderate symptom levels that showed modest improvements during the early preschool years. Overall ASD symptoms for children in these 2 clusters emerged early on, before their second birthday, similar to children who were characterized as showing early-onset patterns in past studies.1,2,4,10 In contrast, another cluster included children whose scores consistently remained below the ADOS cutoff for ASD classification (non-spectrum trajectory; 25% of sample). As expected, most of these children never received an ASD diagnosis, but instead were characterized as having language delays or global developmental delays (47%) or no clinical diagnosis (53%). A fourth cluster (27% of sample) exhibited mild symptom levels at baseline that worsened over time (worsening trajectory). Symptom levels for the worsening group remained lower than those for the severe-persistent group at 3 years of age.

The 4 clusters varied significantly on verbal and cognitive abilities at baseline and final evaluations. The non-spectrum cluster had significantly higher verbal and nonverbal IQs compared to the 3 ASD groups, whereas the worsening group exhibited higher verbal and nonverbal IQs than the moderately-improving and severe-persistent clusters. Up to 30% of children in each of the 3 ASD clusters received relatively intensive intervention (>10 hours/week), although there was no significant difference in the intensity of intervention across groups.

Similar to previous findings that described children with late onset,1,2,4,10,11 children showing the worsening trajectory for overall ADOS-CSS tended to be “more able,” with average to above-average verbal and cognitive skills at baseline. For children in this worsening cluster, ASD symptoms gradually emerged during the second and third year of life. By 3 years, they exhibited moderately severe symptoms, although their symptoms remained somewhat milder than those in the severe-persistent group. Despite worsening ASD symptoms, these children exhibited marked improvements in language and other communication skills over time and were more likely to acquire functional phrase speech by 3 years (as evidenced by their transition to ADOS Module 2) than the moderately-improving or severe-persistent group. Furthermore, these children showed a worsening pattern for a few RRB item scores such as into-nation and stereotyped language, but not for the items in the SA domain. The combination of less clear ASD symptoms, especially in the social communication domain before 2 years and improvements in language and cognition over time, likely contributed to the delay of a more accurate diagnosis of ASD in these children.1,4,37 In the present study, all but 2 children with ASD in the worsening group had received preliminary best-estimate diagnoses of ASD at baseline, whereas the remaining 2 children received an ASD diagnosis by 2 years of age. It is important to note that best-estimate diagnoses for the present study were made by highly trained clinicians who considered multiple sources of information (eg, ADI-R, ADOS, and MSEL) and did not solely rely on cutoffs for any single instrument. Furthermore, the sample of this study included children referred by parents and professionals who were concerned about the children’s development. Thus, findings suggest a need for training of clinicians to conduct comprehensive early assessments to monitor development of at-risk or ASD-referred children, particularly abler toddlers who do not meet full criteria for ASD at the initial visit, to maximize ongoing monitoring efforts to promote earlier, more accurate diagnoses.38

It is encouraging that when trajectories of symptoms were examined at the item level, we found that most children showed notable improvements on a number of specific behaviors measured in the ADOS over time. These changes reflected improvements in communication skills such as overall level of language, amount of vocalizations, and pointing. Improvement in these items was observed even for children in the worsening cluster for whom the severity of core ASD features increased over time. Improvement in developmental skills also has been reported in studies that have examined longer-term trajectories in children with ASD, including those who showed worsening in symptoms from early childhood to adolescence.39 Together, findings suggest that general developmental skills, especially in the area of nonverbal and verbal communication, continue to improve in most children with ASD, irrespective of their worsening or stable trajectories of core autism symptoms.

A closer look at the moderately-improving group highlights 3 important findings. First, this group’s CSS-SA improved over time, whereas their CSS-RRB remained relatively stable, demonstrating that these subdomains manifest distinct trajectories. Second, although the children exhibited improvements in showing response to name, amount of social overtures, initiation of joint attention, and making overtures during the ignore task during the ADOS, other core features of ASD were fairly stable over time (eg, poor shared enjoyment, eye contact, and integration of gaze with other modes of communication). This highlights that symptom domains encompass a broad range of skills and behaviors that might respond differently to intervention and/or general maturation. Third, the patterns of improvement and stability observed in the moderately-improving group were not always observed in the other groups of children. The 3 clusters support the presence of subgroups of ASD who show different patterns of trajectories over time. These results have important implications for clinicians and researchers attempting to measure behavioral changes in ASD, especially in evaluating treatment effectiveness. Studies using overall totals encompassing the SA and RRB domains might fail to demonstrate change in one domain owing to stability or worsening in the other. Moreover, because many intervention programs target specific skills, such as pointing or vocalizations, it is important to note that broadly defined domain scores might fail to reflect treatment-related gains because improvements in individual skills might be masked by worsening of other symptoms. In contrast, improvements in specific skills might reflect general developmental gains that might not have parallels in decreases in ASD symptoms. Even within trajectory clusters, large individual variability in symptom severity was observed, suggesting a need for the use of statistical methods to take into account the intraindividual heterogeneity in relation to time.40

The present analyses focused on identification of trajectory clusters based on the ADOS-CSS, whereas most previous studies based trajectory analyses on the ADOS raw algorithm totals. The CSSs were explicitly designed to allow more valid comparisons of scores across different modules and decrease associations with age and cognitive abilities. Thus, CSS trajectories are deemed a better reflection of changes in ASD symptom severity than raw score trajectories.18–20 Indeed, in the present study, the worsening cluster identified based on the CSS showed stability in raw algorithm totals, although their symptom severity based on CSS worsened over time. This could be due to the effects of maturation and module changes on the algorithm totals; the worsening cluster included many children who moved from the Toddler Module to Module 2. As these children mature and develop language, the CSSs, unlike raw algorithm totals, adjust the comparison group (older preschoolers with flexible phrases) to which these children who are moving to Module 2 are compared. Thus, caution is warranted when using raw ADOS algorithm totals as a measure of change in symptom severity without statistically correcting for module changes.

The present study used frequent observations from a relatively large number of children 1 to 3 years old with ASD to identify distinct symptom trajectories during a developmental period marked by rapid change. However, our observations are limited to the first 3 years of life. In addition, because children were referred at different ages and assessed at different intervals, availability of data varied for any given time point. As a result, the youngest and oldest ages for some clusters had fewer participants (resulting in larger CIs), which could have influenced the “shape” of the trajectory. Interpretation of increases or decreases in CSSs at approximately 3 years of age requires replication in longitudinal samples followed into the preschool or school-age years. In addition, although a subset of children exhibited notable changes in ADOS-CSS, several studies have suggested that the ADOS might not be the most sensitive measure of symptom changes in children with ASD.41 Thus, the present study might underestimate the proportion of toddlers who showed improvements or worsening of symptoms at 1 to 3 years of age. We also modified several codes to compare across different modules. Although we still found statistically significant differences between ASD and non-ASD groups on all recoded items, the interpretation of item-level comparisons across different modules should take into account the potential impact that the context and level of task demands in the ADOS Toddler Module versus Module 2 can have on the individual symptom trajectories.

Significant variability in symptom trajectories was observed among toddlers referred for possible ASD. Although symptom levels for most children with ASD (55%) were relatively stable at 1 to 3 years of age, a subset (20%) exhibited initially mild symptoms that worsened over time, whereas another significant minority (25%) showed improvements in social communication skills. Changes in social communication and RRB domain scores did not always co-occur; for some children, social communication skills improved, whereas RRB worsened or were stable. Similarly, item trajectories did not always align with overall symptom trajectories; although many core ASD symptoms were relatively stable over time, general developmental or communication skills often showed notable improvements for many toddlers. These results highlight the importance of continued monitoring and standardized assessment of toddlers at risk of or referred for ASD, with particular attention to individual symptom trajectories when assessing response to treatment or general maturation. Considering the variability in symptom trajectories observed during a period known to be marked by rapid developmental change, children who receive a diagnosis of ASD or who are at risk of or referred for possible ASD but exhibit “unclear” or “subthreshold” symptom patterns should be re-evaluated within 3 to 6 months to assess ongoing development and emerging challenges that could have diagnostic and treatment implications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the Department of Education (H324 C030112), the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH066496), and a gift from the Simons Foundation.

Andrew Pickles, PhD, served as the statistical expert for this research.

The authors thank the children and families who participated in the study. The authors also thank Andrew Pickles, PhD, of the University of London, and Bethany Vibert, PsyD, and Shanping Qiu, MA, of Weill Cornell Medicine, for their help with analyses and manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Dr. Lord has received royalties from Western Psychological Services for publication of the Autism Diagnostic Interview–Revised (ADI-R) and the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS). Drs. Kim, Bal, Guthrie, Colombi and Mss. Benrey and Choi report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

So Hyun Kim, Center for Autism and the Developing Brain, Weill Cornell Medicine, White Plains, NY..

Vanessa H. Bal, Weill Institute for Neurosciences, University of California, San Francisco..

Nurit Benrey, Center for Autism and the Developing Brain, Weill Cornell Medicine, White Plains, NY..

Yeo Bi Choi, Center for Autism and the Developing Brain, Weill Cornell Medicine, White Plains, NY..

Whitney Guthrie, Center for Autism Research, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, PA..

Costanza Colombi, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor..

Catherine Lord, Center for Autism and the Developing Brain, Weill Cornell Medicine, White Plains, NY..

REFERENCES

- 1.Chawarska K, Shic F, Macari S, et al. 18-Month predictors of later outcomes in younger siblings of children with autism spectrum disorder: a baby siblings research consortium study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53:1317–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landa RJ, Gross AL, Stuart EA, Faherty A. Developmental trajectories in children with and without autism spectrum disorders: the first 3 years. Child Dev. 2013;84: 429–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim SH, Macari S, Koller J, Chawarska K. Examining the phenotypic heterogeneity of early autism spectrum disorder: subtypes and short-term outcomes. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2016;57:93–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ozonoff S, Young GS, Landa RJ, et al. Diagnostic stability in young children at risk for autism spectrum disorder: a baby siblings research consortium study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015;56:988–998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ozonoff S, Heung K, Byrd R, Hansen R, Heitz-Picciotto I. The onset of autism: patterns of symptom emergence in the first years of life. Autism Res. 2008;1:320–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macari SL, Campbell D, Gengoux GW, Saulnier CA, Klin AJ, Chawarska K. Predicting developmental status from 12 to 24 months in infants at risk for autism spectrum disorder: a preliminary report. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42:2636–2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chawarska K, Klin A, Paul R, Volkmar F. Autism spectrum disorder in the second year: stability and change in syndrome expression. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48:128–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chawarska K, Klin A, Paul R, Macari S, Volkmar F. A prospective study of toddlers with ASD: short-term diagnostic and cognitive outcomes. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009; 50:1235–1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guthrie W, Swineford LB, Nottke C, Wetherby AM. Early diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder: stability and change in clinical diagnosis and symptom presentation. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013;54:582–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bryson SE, Zwaigenbaum L, Brian J, et al. A prospective case series of high-risk infants who developed autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37:12–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brian J, Bryson SE, Smith IM, et al. Stability and change in autism spectrum disorder diagnosis from age 3 to middle childhood in a high-risk sibling cohort. Autism Int J Res Pract. 2016;20:888–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soke GN, Philofsky A, Diguiseppi C, Lezotte D, Rogers S, Hepburn S. Longitudinal changes in scores on the Autism Diagnostic Interview–Revised (ADI-R) in pre-school children with autism: implications for diagnostic classification and symptom stability. Autism. 2011;15:545–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lord C, Bishop S, Anderson D. Developmental trajectories as autism phenotypes. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2015;169:198–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lord C, Luyster R, Guthrie W, Pickles A. Patterns of developmental trajectories in toddlers with autism spectrum disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80:477–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lord C, Rutter M, Dilavore PC, et al. ADOS: Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Vol 1 Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Visser JC, Rommelse NNJ, Lappenschaar M, Servatius-Oosterling IJ, Greven CU, Buitelaar JK. Variation in the early trajectories of autism symptoms is related to the development of language, cognition, and behavior problems. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56:659–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gotham K, Pickles A, Lord C. Standardizing ADOS scores for a measure of severity in autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2009;39:693–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joseph RM, Tager-Flusberg H, Lord C. Cognitive profiles and social-communicative functioning in children with autism spectrum disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2002;43:807–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Bildt A, Sytema S, Ketelaars C, et al. Interrelationship between Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule–Generic (ADOS-G), Autism Diagnostic Interview–Revised (ADI-R), and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) classification in children and adolescents with mental retardation. J Autism Dev Disord. 2004;34:129–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gotham K, Risi S, Pickles A, Lord C. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule: revised algorithms for improved diagnostic validity. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37:613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hus V, Gotham K, Lord C. Standardizing ADOS domain scores: separating severity of social affect and restricted and repetitive behaviors. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44: 2400–2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esler AN, Bal VH, Guthrie W, Wetherby A, Ellis Weismer S, Lord C. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Toddler Module: standardized severity scores. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45:2704–2720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zwaigenbaum L, Bryson S, Rogers T, Roberts W, Brian J, Szatmari P. Behavioral manifestations of autism in the first year of life. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2005;23:143–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szatmari P, Georgiades S, Duku E, et al. Developmental trajectories of symptom severity and adaptive functioning in an inception cohort of preschool children with autism spectrum disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:276–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ozonoff S, Iosif A-M, Young GS, et al. Onset patterns in autism: correspondence between home video and parent report. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50: 796–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baird G, Charman T, Pickles A, et al. Regression, developmental trajectory and associated problems in disorders in the autism spectrum: the SNAP study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008;38:1827–1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mullen EM. Mullen Scales of Early Learning. Circle Pines, MN: AGS; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sparrow SS, Balla DA, Cicchetti DV. Vineland-II Adaptive Behavior Scales. Circle Pines, MN: AGS; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rutter M, LeCouteur A, Lord C. The Autism Diagnostic Interview–Revised (ADI-R). Western Los Angeles, CA: Psychological Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 30.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones BL, Nagin DS. Advances in group-based trajectory modeling and an SAS procedure for estimating them. Sociol Methods Res. 2007;35:542–571. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagin DS, Land KC. Age, criminal careers, and population heterogeneity: specification and estimation of a nonparametric, mixed Poisson model. Criminology. 1993;31: 327–362. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Niyonkuru C, Wagner AK, Ozawa H, Amin K, Goyal A, Fabio A. Group-based trajectory analysis applications for prognostic biomarker model development in severe TBI: a practical example. J Neurotrauma. 2013;30:938–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nagin D Group-Based Modeling of Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones BL, Nagin DS, Roeder K. A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Sociol Methods Res. 2001;29:374–393. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wickham H Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. New York: Springer; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bedford R, Gliga T, Shephard E, et al. Neurocognitive and observational markers: prediction of autism spectrum disorder from infancy to mid-childhood. Mol Autism. 2017;8:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dawson G Why it’s important to continue universal autism screening while research fully examines its impact. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170:527–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gotham K, Pickles A, Lord C. Trajectories of autism severity in children using standardized ADOS scores. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e1278–e1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Georgiades S, Bishop SL, Frazier T. Editorial perspective: longitudinal research in autism–introducing the concept of “chronogeneity.” J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2017; 58:634–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grzadzinski R, Carr T, Colombi C, et al. Measuring changes in social communication behaviors: preliminary development of the Brief Observation of Social Communication Change (BOSCC). J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46:2464–2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.