Summary

Purpose Sorafenib is a small molecule inhibitor of multiple signaling kinases thought to contribute to the pathogenesis of many tumors including brain tumors. Clinical trials with sorafenib in primary and metastatic brain tumors are ongoing. We evaluated the plasma and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pharmacokinetics (PK) of sorafenib after an intravenous (IV) dose in a non-human primate (NHP) model. Methods 7.3 mg/kg of sorafenib free base equivalent solubilized in 20% cyclodextrin was administered IV over 1 h to three adult rhesus monkeys. Serial paired plasma and CSF samples were collected over 24 h. Sorafenib was quantified with a validated HPLC/tandem mass spectrometry assay. PK parameters were estimated using non-compartmental methods. CSF penetration was calculated from the AUCcsf : AUCplasma. Results Peak plasma concentrations after IV dosing ranged from 3.4 to 7.6 μg/mL. The mean±standard deviation (SD) area under the plasma concentration from 0 to 24 h was 28±4.3 μg•h/mL, which is comparable to the exposure observed in humans at recommended doses. The mean±SD clearance was 1.7±0.5 mL/min/kg. The peak CSF concentrations ranged from 0.00045 to 0.00058 μg/mL. The mean±SD area under the CSF concentration from 0 to 24h was 0.0048 ±0.0016 μg•h/mL. The mean CSF penetration of sorafenib was 0.02% and 3.4% after correcting for plasma protein binding. Conclusion Sorafenib is well tolerated in NHP and measurable in CSF after an IV dose. The CSF penetration of sorafenib is limited relative to total and free drug exposure in plasma.

Keywords: Sorafenib, Pharmacokinetics, Cerebrospinal fluid, Non-human primate model

Introduction

Sorafenib (Nexavar®; Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals, Wayne, NJ and Onyx Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Emeryville, CA) is an orally bioavailable, small molecule inhibitor of multiple protein kinases that are components of signaling pathways that control tumor growth and angiogenesis. Sorafenib was initially identified as an inhibitor of Raf serine/threonine kinase isoforms, which are in the Ras signaling pathway, and also inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR)-1 and VEGFR-2, platelet derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR)-β, Flt-3 and c-Kit [1].

Activating ras mutations occur in approximately 30% of human cancers [2–4]. The Ras signaling pathway may also be upregulated in the absence of Ras mutations [5]. Activated Ras initiates several signaling cascades, and is best characterized by the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK cascade [6]. Raf mutations and/or over expression have been demonstrated in gliomas [7, 8] and activation and over expression of MEK and ERK have been demonstrated in gliomas and other brain tumors [8–10]. In addition, angiogenesis is essential for growth of primary and metastatic brain tumors [11], and VEGF is expressed in a wide spectrum of brain tumors [12]. Sorafenib has demonstrated inhibition of cell proliferation and growth in pre-clinical malignant glioma [13] and medulloblastoma [14] models.

Sorafenib is FDA approved for the treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma and unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. It is currently being studied in the clinical setting as a single agent and in combination with other agents and/or radiation for primary and metastatic brain tumors. We evaluated the plasma and cerebrospinal (CSF) pharmacokinetics of sorafenib after an intravenous dose in our non-human primate model (NHP), which is predictive of CSF pharmacokinetics in a variety of anticancer drugs in humans [15].

Materials and methods

Drug

Sorafenib Tosylate (BAY 43–9006 tosylate; molecular weight (MW) 637 g/mole) was provided through the Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program (CTEP) supplied by Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals (Wayne, NJ) and Onyx Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Emeryville, CA) in powder form. A dose of 7.3 mg/kg of sorafenib freebase equivalent (MW 464 g/mole) (10 mg/kg of sorafenib tosylate) was solubilized in 20% Captisol® (sulfobutylether-β -cyclodextrin, CyDex Inc., Lenexa, KS) in normal saline. The solution was clear and no particles were observed. The solution was filtered through a 22-micron filter prior to administration. The pre- and post-filtered concentrations demonstrated no differences. The dose selected was an approximate equivalent conversion [16] from the recommended dose for adults with refractory cancers. Sorafenib was administered as a 1 h intravenous (IV) infusion.

Animals

Three adult male rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) were used for this study. The experimental protocol was approved by National Cancer Institute’s Animal Care and Use Committee. The NHP were housed in accordance with the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and fed NIH Open Formula Extruded Non-Human Primate diet. The NHP were pretreated with ondansetron for nausea precaution. The NHP received sorafenib as an IV infusion through a jugular venous port (n=2) or left saphenous vein (n =1) and blood samples were drawn from a saphenous venous catheter on the contra-lateral side to the site of drug administration. CSF samples were obtained from a chronic indwelling fourth ventricular Pudenz silicon catheter attached to a subcutaneously implanted Ommaya reservoir.

Experiments

Blood was collected (1 mL per sample) in heparinized tubes at time 0, 15, 30, and 60 min (end of infusion) and then post infusion at 5, 15, and 30 min, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 24 h. Plasma was immediately separated by centrifugation, placed in polypropylene tubes, and frozen at −70°C until analysis. CSF samples (0.3 mL per sample) were collected in polypropylene tubes at time 0, 30, 60 min (end of infusion) and then post infusion at 30 min, 1, 2, 3, 4 6, 8, 10, 24 h and frozen immediately at −70°C until analysis.

Sample analysis

Samples were prepared and quantified using HPLC/MS/MS method adapted from an assay developed by Jain et al. [17]. Sorafenib was extracted by protein precipitation adding 0.5 mL of acetonitrile containing 50 ng/mL of internal standard ([2H3, 15N] sorafenib) to 50 μL of plasma. Samples were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min and the supernatant was transferred to a glass injection vial for same day analysis on the HPLC/MS/MS. CSF samples were thawed at room temperature, vortexed for 30 s, and transferred to a glass injection vial for same day analysis on the HPLC/MS/MS.

Sorafenib was quantified with an Applied Biosystems MDS Sciex API 5000 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Foster City, CA, USA). The HPLC system included Shimadzu LC-20 AD pumps and Shimadzu SIL 20 AC autosampler and column heater (Columbia, MD, USA). Chromatographic separation was performed using a Waters Symmetry Shield RP8 (2.1 mm×50 mm, 3.5 μm) column (Milford, MA, USA) with an injection volume of 10 μL. Samples were eluted using an isocratic mixture of acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid in water: 55/45 (v/v) at the flow rate of 0.25 mL/minute with a retention time of 3.1 min and total run time of 5 min. The autosampler temperature was set to 4°C, and the column chamber to 40°C. Mass spectrometer conditions for this assay were optimized in the positive electrospray ionization, multiple reaction monitoring mode measuring the transition of sorafenib precursor to product ion, 465–252 amu, and sorafenib internal standard precursor to product ion, 469–256 amu. The collision gas was set at 6 psi, curtain gas 25 psi, and ion source gas 1 at 60 psi. Ion spray voltage was 5,500 V, declustering potential 166 V, entrance potential 10 V, and collision energy 49 V. Ion source temperature was set at 650°C. Analyst® software 1.4.2 (Foster City, CA, USA) was used for data analysis.

Validation of the HPLC/MS/MS assay for sorafenib quantification was conducted according to the FDA bioanalytical method validation guidelines [18]. Sorafenib and internal standard [2H3, 15N] sorafenib were provided by CTEP through Bayer Health Care (New Haven, CT, USA). Stock solutions and internal standards were prepared as previously described [17], and the final concentrations of the plasma quality controls were 8, 160, and 400 ng/mL. The plasma calibration curve samples were prepared in batch, by the addition of pooled human plasma (NIH Clinical Center Blood Bank, Bethesda, MD, USA) to the required amount of working solution in a volumetric flask to obtain concentrations of 5, 10, 50, 100, 250, and 500 ng/mL. Each concentration was stored at −20°C as 50 μL aliquots. Plasma calibration curves were linear in the concentration range of 5–500 ng/mL. The assay was found to be precise and accurate. Intra-day precision of quality controls ranged from 2.2–4.1% and accuracy ranged from 99–103%. The lower limit of quantification was 5 ng/mL. The inter-day coefficient of variation was < 4% and accuracy ranged from 96–98%.

The aqueous calibration curve at concentrations of 0.025, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 5, 10, and 50 ng/mL and quality controls at concentrations of 0.04, 4, and 20 ng/mL were prepared the same day of analysis. The intra-day precision of quality controls ranged from 2.3–4.0% and accuracy ranged from 97–102%. The lower limit of quantification was 0.025 ng/mL. The interday coefficient of variation was < 5% and accuracy ranged from 98–102%.

Pharmacokinetic analysis

The plasma and CSF pharmacokinetics of sorafenib were analyzed by non-compartmental methods. The peak sorafenib concentration (Cmax) and time to peak concentration (Tmax) were determined from the time-concentration data for each NHP. Area under the concentration curve (AUC0−24h) was calculated using the linear trapezoidal method and extrapolated to infinity (AUC0−∞). The terminal half-life was calculated by dividing 0.693 by the terminal rate constant. Clearance (CL) was calculated by dividing the sorafenib dose by the AUC0−∞. The CSF penetration was calculated from the AUCCSF 0−24h: AUCplasma 0−24h ratio. The in Vitro binding of sorafenib to human plasma proteins is 99.5% [19]. This value was used to calculate the AUC of free sorafenib in plasma.

Results

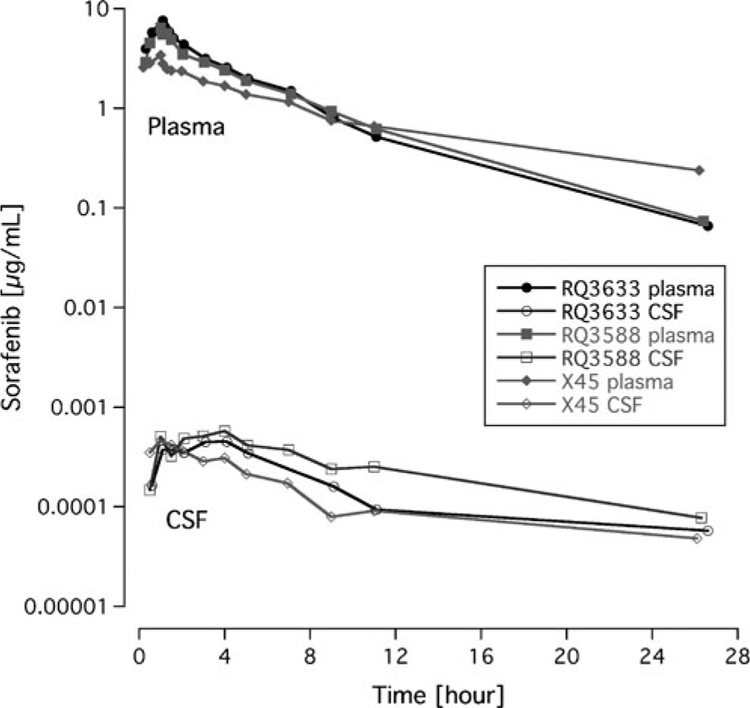

The PK parameters of sorafenib in the NHP for plasma and CSF are described in Table 1. There was little variability for the PK parameters following a single IV dose. Peak plasma concentrations after IV dosing ranged from 3.4 to 7.6 μg/mL. The peak plasma sorafenib concentration occurred in all monkeys at the end of infusion (1 h). The mean±standard deviation (SD) area under the plasma concentration from 0 to 24 h was 28±4.3 μg•h/mL. The mean±SD clearance was 1.7±0.5 mL/min/kg. The peak CSF concentrations ranged from 0.00045 to 0.00058 μg/mL. The mean±SD area under the CSF concentration from 0 to 24 h was 0.0048 to 0.0016 μg•h/mL. Comparing the AUC0−∞ to the AUC0−24h, approximately 57% and 14% of the drug exposure was extrapolated in the plasma and CSF respectively. The plasma and CSF concentration-time profile for each NHP is shown in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid pharmacokinetic parameters for sorafeniba

| NHP | Wt (kg) | Plasma | T1/2 [h] | CSF | CSF: Plasma [%] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmax [μg/mL] |

AUC0–24h [μg•h/mL] |

AUC0–∞ [μg•h/mL] |

Clearance [mL/min/kg] | Cmax [μg/mL] |

AUC0–24h [μg•h/mL] |

AUC0–∞ [μg•h/mL] |

Tl/2 [h] |

||||

| RQ3633 | 11.4 | 7.6 | 31.2 | 56.0 | 2.2 | 3.8 | 0.00045 | 0.0042 | 0.0049 | 7.7 | 0.013 |

| RQ3588 | 11.2 | 6.4 | 29.6 | 61.0 | 2.0 | 4.1 | 0.00058 | 0.0066 | 0.0076 | 8.9 | 0.022 |

| X45 | 14.0 | 3.4 | 23.2 | 93.7 | 1.3 | 7.2 | 0.00046 | 0.0034 | 0.0041 | 9.4 | 0.015 |

| Mean | 12.2 | 5.8 | 28.0 | 70.2 | 1.7 | 5.0 | 0.00050 | 0.0048 | 0.0055 | 8.7 | 0.017 |

| SD | 1.6 | 2.1 | 4.3 | 20.5 | 0.5 | 1.9 | 0.00007 | 0.0016 | 0.0016 | 0.9 | 0.005 |

All animals received 7.3 mg/kg of sorafenib free base equivalent

CSF Cerebrospinal Fluid, NHP Non-human primate, Wt weight, Cmax maximum concentration, AUC0−24h area under the concentration-time curve from 0 to 24 h, T1/2 half life, CSF: Plasma, ratio of AUC 0−24h in CSF to AUC0−24h in plasma

Fig. 1.

Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid concentration-time curves of sorafenib in non-human primates (n=3)

The mean CSF penetration was 0.02% using the ratio of CSF AUC 0−24h to plasma AUC0−24h. After correcting for plasma protein binding, the mean CSF penetration was 3.4%.

Discussion

We used our NHP model to determine the plasma and CSF PK of sorafenib after a single IV dose of sorafenib. Sorafenib is an oral agent, but was readily solubilized in 20% cyclodextrin in normal saline for intravenous use in our model. An IV formulation was utilized due to the technical difficulty giving oral compounds to the NHP. IV in comparison to oral administration provides additional advantages such as limiting variability due to absorption and bioavailability, essentially providing an optimal setting in determining CSF penetration. The dose selected for the NHP was an approximately equivalent dose recommended to humans. The NHP tolerated this formulation well without any clinical toxicity or sequelae. The mean Cmax observed in the NHP in this study was 5.8 ± 2.1 μg/mL, while the day 1 Cmax in adult phase I studies of oral sorafenib for refractory solid tumors ranged from 2.3 to 3.0 μg/mL at the recommended dose of 400 mg twice daily [20]. At the MTD of 200 mg/m2/dose in a phase I trial of refractory solid tumors in children, the mean single day plasma AUC0−24h was 28± 17 μg•h/mL [21], which is similar to the mean plasma AUC0−24h of 28±4.3 μg•h/mL in the NHP. Thus, the dose used in the NHP achieved sorafenib concentrations and exposure similar to those observed in both adults and children with refractory cancers at their respective recommended doses.

Plasma concentrations of sorafenib after oral administration in adult and pediatric phase I trials were highly variable across patients [21–25]. Some of the variability after oral dosing could be due to factors relating to absorption such as the potential slow dissolution of the tablets in the gastrointestinal tract [22]. The mean AUC and Cmax increases less than proportionally beyond the recommend adult dose of 400 mg orally twice daily [22–25], which could be due to saturable absorption. Sorafenib tablets have a mean relative bioavailability of 38–49% compared with oral solution [19]. Preclinical data also indicate that sorafenib is subjected to enterohepatic circulation, the extent of which may vary between patients [22]. In contrast, the variability in the NHP was minimal after the IV dose, although the subject numbers were small.

The plasma terminal half-life of sorafenib in the NHP (T1/2=5.0 h) was much less than the half-life of sorafenib reported in the literature, which ranges from 19.7–39 h [23–25]. The terminal half-life may be underestimated in the NHP as a result of the limited sampling duration of 24 h as 57% of the AUC0−∞ was extrapolated. Given that we administered sorafenib IV, clearance could be calculated, but no known comparison data are available due to only oral administration in clinical use.

The concentrations achieved in the CSF were low, but measureable using a sensitive validated HPLC/MS/MS assay with a lower limit of quantification of 0.025 ng/mL. The CSF penetration of sorafenib was only 0.02% relative to total (free and protein bound) plasma drug exposure. Sorafenib is highly protein bound, and thus CSF penetration was calculated using an estimated free drug exposure. However, correcting for protein binding only minimally increased the CSF penetration to 3.4%.

The drug exposure of sorafenib in the CSF relative to total and free drug plasma exposure in NHP is limited. The NHP model has been highly predictive of CNS pharmacology in humans [15]. Previous experiments have also demonstrated CSF penetration of drugs was comparable to brain extracellular fluid penetration in the NHP model, and CSF penetration appears to be a surrogate for brain extracellular free drug exposure [26, 27]. In healthy tissues, the tight junctions between endothelial cells, which form the blood brain barrier (BBB), prevent hydrophilic molecules over 500 kDa from passively entering the brain parenchyma. Sorafenib is approximately 465 Da, but is 99.5% plasma protein bound, which likely prevents most of it from penetrating brain tissue in a healthy subject. Brain tumors, however, disrupt the brain vasculature leading to the loss of the BBB integrity, as well as marked angiogenesis with endothelial proliferation, severe hypoxia, and tumor necrosis [11]. Delivery of agents to tumors within the CNS may be influenced by this disruption, and sorafenib may penetrate abnormal brain tissue of primary and metastatic brain tumors. There is a case report of durable complete resolution (> 9 months) of brain metastases in a patient with renal cell carcinoma treated with sorafenib [28].

There also may be a role of sorafenib in preventing the occurrence of brain metastases, which was described in a retrospective study, which evaluated the incidence of brain metastases in a subgroup of patients enrolled on the randomized phase III Treatment Approaches in Renal Cancer Global Evaluation Trial (TARGET) [29]. The overall incidence of brain metastases in patients receiving sorafenib was statistically significantly lower than those receiving placebo (3% compared to 12%; p<0.05). The authors concluded that the anti-metastatic effect may be due to either action on the primary tumor to prevent formation of metastases versus directly penetrating the brain to target the metastatic site directly, by potentially acting on brain micrometastases. Based on our findings of limited CSF penetration, sorafenib may act in limiting metastatic spread by controlling the primary disease [30]. Sorafenib is being evaluated in multiple clinical trials in primary and metastatic brain tumors as a single agent and in combination with other agents and/or radiation therapy and the clinical outcomes are pending.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research. The views expressed do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institutes of Health or the US government.

References

- 1.Wilhelm SM et al. (2004) BAY 43–9006 exhibits broad spectrum oral antitumor activity and targets the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway and receptor tyrosine kinases involved in tumor progression and angiogenesis. Cancer Res 64(19):7099–7109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lowy DR, Willumsen BM (1993) Function and regulation of ras. Annu Rev Biochem 62:851–891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodenhuis S (1992) Ras and human tumors. Semin Cancer Biol 3 (4):241–247 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Satoh T, Kaziro Y (1992) Ras in signal transduction. Semin Cancer Biol 3(4):169–177 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reuter CW, Morgan MA, Bergmann L (2000) Targeting the Ras signaling pathway: a rational, mechanism-based treatment for hematologic malignancies? Blood 96(5):1655–1669 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mercer KE, Pritchard CA (2003) Raf proteins and cancer: B-Raf is identified as a mutational target. Biochim Biophys Acta 1653(1):25–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minniti G et al. (2009) Chemotherapy for glioblastoma: current treatment and future perspectives for cytotoxic and targeted agents. Anticancer Res 29(12):5171–5184 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Newton HB (2007) Small-molecule and antibody approaches to molecular chemotherapy of primary brain tumors. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 8(12):1009–1021 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forshew T et al. (2009) Activation of the ERK/MAPK pathway: a signature genetic defect in posterior fossa pilocytic astrocytomas. J Pathol 218(2):172–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tatevossian RG et al. (2010) MAPK pathway activation and the origins of pediatric low-grade astrocytomas. J Cell Physiol 222(3):509–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jain RK et al. (2007) Angiogenesis in brain tumours. Nat Rev Neurosci 8(8):610–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Machein MR, Plate KH (2000) VEGF in brain tumors. J Neurooncol 50(1–2):109–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jane EP, Premkumar DR, Pollack IF (2006) Coadministration of sorafenib with rottlerin potently inhibits cell proliferation and migration in human malignant glioma cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 319(3):1070–1080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang F et al. (2008) Sorafenib inhibits signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 signaling associated with growth arrest and apoptosis of medulloblastomas. Mol Cancer Ther 7(11):3519–3526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCully CL et al. (1990) A rhesus monkey model for continuous infusion of drugs into cerebrospinal fluid. Lab Anim Sci 40 (5):520–525 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freireich EJ et al. (1966) Quantitative comparison of toxicity of anticancer agents in mouse, rat, hamster, dog, monkey, and man. Cancer Chemother Rep 50(4):219–244 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jain L et al. (2008) Development of a rapid and sensitive LC-MS/MS assay for the determination of sorafenib in human plasma. J Pharm Biomed Anal 46(2):362–367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Administration, U.D.o.H.a.H.S.F.a.D., Guidance for Industry, Bioanalytical Method Validation. May 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nexavar Healthcare B. (sorafenib) package insert. 2005: West Haven, CT [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strumberg D et al. (2007) Safety, pharmacokinetics, and preliminary antitumor activity of sorafenib: a review of four phase I trials in patients with advanced refractory solid tumors. Oncologist 12 (4):426–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Widemann B et al. (2009) Phase I study of sorafenib in children with refractory solid tumors: a children’s oncology group phase I consortium trial. J Clin Oncol 27(15s): p. Suppl; abstr 10012 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strumberg D et al. (2005) Phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of the Novel Raf kinase and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitor BAY 43–9006 in patients with advanced refractory solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 23(5):965–972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Awada A et al. (2005) Phase I safety and pharmacokinetics of BAY 43–9006 administered for 21 days on/7 days off in patients with advanced, refractory solid tumours. Br J Cancer 92 (10):1855–1861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore M et al. (2005) Phase I study to determine the safety and pharmacokinetics of the novel Raf kinase and VEGFR inhibitor BAY 43–9006, administered for 28 days on/7 days off in patients with advanced, refractory solid tumors. Ann Oncol 16(10):1688–1694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clark JW et al. (2005) Safety and pharmacokinetics of the dual action Raf kinase and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitor, BAY 43–9006, in patients with advanced, refractory solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 11(15):5472–5480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobs S et al. Extracellular fluid concentrations of cisplatin, carboplatin, and oxaliplatin in brain, muscle, and blood measured using microdialysis in nonhuman primates. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 65(5): 817–824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fox E et al. (2002) Zidovudine concentration in brain extracellular fluid measured by microdialysis: steady-state and transient results in rhesus monkey. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 301(3):1003–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valcamonico F et al. (2009) Long-lasting successful cerebral response with sorafenib in advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Neurooncol 91(1):47–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Massard C et al. (2010) Incidence of brain metastases in renal cell carcinoma treated with sorafenib. Ann Oncol 21(5):1247–1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Escudier B et al. (2007) Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 356(2):125–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]