Abstract

Background and Aims:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are used in the treatment of multiple advanced-stage cancers but can induce immune-mediated colitis necessitating treatment with immunosuppressive medications. Diagnostic colonoscopy is often performed but requires bowel preparation and may delay diagnosis and treatment. Sigmoidoscopy can be performed rapidly without oral bowel preparation or sedation. Therefore, we aimed to characterize the colonic distribution of this disease to determine the most efficient endoscopic approach.

Methods:

A systematic review of checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis case reports and series was conducted in both PubMed and Embase through 3/1/2017. A single center retrospective chart review of patients who underwent endoscopic evaluation for diarrhea after treatment with a checkpoint inhibitor (Ipilimumab, Nivolumab, or Pembrolizumab) between 1/1/2011 to 3/1/2017 was performed. Clinical, endoscopic, and histologic data were collected.

Results:

A detailed systematic review resulted in 61 studies, in which 226 cases of colitis were diagnosed by lower endoscopy (125 colonoscopy, 101 sigmoidoscopy). Only 4 patients had isolated findings proximal to the left colon. In our center, 31 patients had histologic features of checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis, for which 29 patients had complete data. The left colon was involved in all cases. Sigmoidoscopy would be sufficient to diagnose >98% of reported cases of checkpoint-inhibitor mediated colitis diagnosed by lower endoscopy.

Conclusions:

Moderate to severe checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis involves the left colon in the majority of cases (>98%). Sigmoidoscopy should be the initial endoscopic procedure in the evaluation of this condition.

Keywords: Checkpoint Inhibitor, Enterocolitis, Colitis, Ipilimumab

Introduction:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are a novel class of biologic therapies that enhance T lymphocyte-mediated anti-tumor activity through inhibition of negative costimulatory molecules such as cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)1. Ipilimumab (a monoclonal antibody against CTLA-4), Nivolumab (a monoclonal antibody against PD-1), and Pembrolizumab (a monoclonal antibody against PD-1) were first approved for the treatment of advanced melanoma, where they have been shown to have a significant survival benefit. Emerging data has led to expansion of FDA approved indications to include renal cell carcinoma, urothelial carcinoma, non-small cell lung cancer, and classical Hodgkin lymphoma for Nivolumab and non-small cell lung cancer and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma for Pembrolizumab. While the therapeutic intent is to enhance T-lymphocyte-mediated anti-tumor activity in the tumor microenvironment, these agents often lead to more global T lymphocyte dysregulation that can result in inflammatory adverse events known as immune-related adverse events (IRAE)1.

Gastrointestinal IRAEs are common with anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 therapy and primarily manifest as diarrhea or colitis characterized by the presence of abdominal pain, fevers, or blood in stool as classified by NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events criteria (CTCAE)2. Incidence rates vary depending on the therapy and dose, with the highest rates reported in trials of Ipilimumab at 10mg/kg and combination Ipilimumab/Nivolumab therapy3,4. In trials of Ipilimumab, any grade diarrhea has been reported in 30–46% of patients with severe (CTCAE grade 3–5) diarrhea or colitis reported in 5–16%3,5. With Ipilimumab therapy, symptoms of colitis typically occur after 2–3 doses6–8. Symptomatic colitis after anti-PD-1 therapy is less predictable with onset after 3–14 doses in published studies9–11.

Recently published guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) have outlined a practical approach to the management of checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis5. It is suggested that mild diarrhea (Grade 1) be managed with anti-diarrheal agents with consideration of temporarily holding checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Moderate to severe (Grade 2–4) or persistent diarrhea is managed with systemic high dose corticosteroids (1mg/kg/day prednisone) followed by Infliximab or Vedolizumab for refractory disease. Diagnostic colonoscopy with possible upper endoscopy has been recommended in cases of grade 2 or higher diarrhea. Repeat colonoscopy has been suggested for refractory symptoms if concern for infection that can be associated with immunosuppressive therapy (cytomegalovirus).

Gastroenterologists are often consulted to perform lower gastrointestinal endoscopic evaluation of patients with suspected severe or persistent colitis. Macroscopic findings on endoscopy are variable but often include erythema, friability, ulceration, granularity, though normal appearing mucosa is possible6. Microscopic findings are even more variable, with the most common histologic findings including intraepithelial lymphocytes, cryptitis, and crypt abscesses6. While multiple case series have reported the predominant distribution patterns as pan-colonic or left sided colonic, the optimal endoscopic approach to this condition has not been determined6–8. We reviewed cases of checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis at the University of Michigan Health System and performed a systematic review of published studies to characterize the lower gastrointestinal distribution pattern of this condition to determine the diagnostic yield of flexible sigmoidoscopy alone compared to complete colonoscopy.

Methods

Patient Selection

A written waiver of consent was provided by the local institutional review board to conduct a retrospective search of the electronic medical record database at the University of Michigan Health System. We used an electronic medical record information retrieval tool (EMERSE) to identify all patients that had any exposure to Ipilimumab, Nivolumab, or Pembrolizumab12. The medical records of these patients were manually searched to identify patients that had been clinically diagnosed with checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis. The medical records of these patients were then manually searched to identify patients that had undergone either colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy. Patients that underwent endoscopic evaluation for diarrhea after exposure to a checkpoint inhibitor were selected for further chart review. In all patients undergoing endoscopy for suspected colitis, clostridium difficile and other gastrointestinal infection had been excluded by stool testing.

Patient Clinical and Endoscopic Characteristics

Key patient characteristics including age (at time of endoscopic procedure), gender, type of malignancy, and checkpoint inhibitor regimen were recorded. The number of checkpoint inhibitor infusions prior to first report of diarrhea and time to onset of diarrhea from therapy initiation were recorded. The severity of diarrhea at time of endoscopy was graded using the common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE, version 4.0) based on data from the medical record. Therapeutic data including use and timing of corticosteroids and infliximab for colitis management was recorded. Clinical data regarding hospitalizations related to colitis, bowel perforation, and need for bowel resection were recorded.

Endoscopy type (full colonoscopy, incomplete colonoscopy, and flexible sigmoidoscopy) and timing relative to symptom onset were recorded. Endoscopic reports and images were manually reviewed to determine the disease distribution pattern of any gross inflammatory changes. The segments were categorized as rectum, sigmoid, descending colon, transverse colon, ascending colon/cecum, and terminal ileum. Macroscopic inflammatory changes included any of the following: loss of vascularity, erythema, friability, granularity, edema, exudates, erosions, or ulceration. The lower gastrointestinal tract was categorized into 3 segments for histological assessment including terminal ileum, right colon, and left colon. This additional categorization was used as practitioners frequently performed right colon and left colon rather than true segmental colonic biopsies.

Systematic Review Search Strategy:

With the assistance of a medical librarian, a systematic literature search of Pubmed (through March 1, 2017) and Embase (through March 1, 2017) was conducted for all relevant articles reporting colitis associated with use of the checkpoint inhibitor class of medications. Keywords used in the search included “Checkpoint inhibitor”, “CTLA-4 inhibitor”, “PD-1 inhibitor”, “Ipilimumab”, “Nivolumab”, “Pembrolizumab”, or “Tremelimumab” combined with “diarrhea”, “colitis”, “enterocolitis”, “toxicity”, “clinical trial”, or “adverse event”. The title and abstract of studies identified in the search were reviewed by 2 investigators independently (A.P.W and M.S.P) to exclude studies that did not pertain to the research question. The full text of the remaining articles was examined to determine whether they met study selection criteria. Any discrepancies between investigators were addressed with a joint re-evaluation of the article. If agreement between investigators could not be reached, a third investigator (R.W.S) adjudicated the discrepancy.

Selection Criteria:

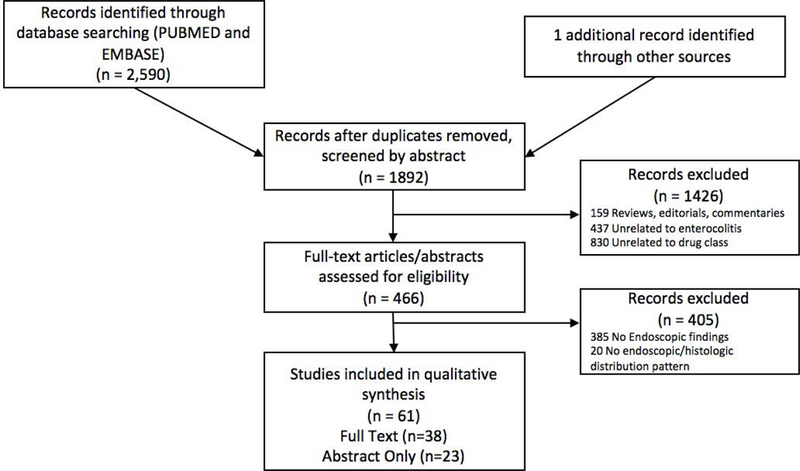

Studies considered in this systematic review included those with experimental design (clinical trials) and observational design (case series, case reports) that met the following inclusion criteria: (1) clearly defined exposure to a medication identified as an immune checkpoint inhibitor, (2) reported occurrence of diarrhea as a complication related to immune checkpoint inhibitor exposure, (3) performance of lower gastrointestinal endoscopy for evaluation of diarrhea, and (4) sufficient description of endoscopic and histologic findings to determine distribution of lower gastrointestinal involvement by inflammatory changes attributed immune checkpoint inhibitor-mediated colitis. Inclusion was otherwise not restricted by study size or publication type. Meeting abstracts were included if the above criteria were met. When multiple studies reported on the same patient cohort, only the most comprehensive study was included. Studies were excluded if patients had previous documented inflammatory bowel disease. A quality assessment was not performed as this was a systematic review that mostly consisted of case series and case reports (i.e., low quality). Figure 1 summarizes the study identification and selection process.

Figure 1.

Systematic review flow chart.

Data Abstraction

Data were independently abstracted onto a standardized form by 2 investigators (A.P.W and M.S.P). The following data were collected from each study: study design, year of publication, number of study patients, type of immune checkpoint inhibitor exposure, grade of diarrhea experienced by study patients, type of lower gastrointestinal endoscopic examination performed, and pattern of distribution of endoscopic and histologic findings. In two studies the type of lower endoscopic exam (flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy) could not be distinguished13,14. These studies reported left sided colonic findings in 100% of cases. As only left sided findings were reported, these studies were included for analysis along with cases of flexible sigmoidoscopy. We characterized the clinical severity as either mild (grade 1–2 diarrhea) or moderate-severe (grade 3–4 diarrhea and/or use of systemic corticosteroids or Infliximab) based on available data. The distribution of endoscopic and/or histologic findings was categorized as “any left sided colonic involvement”, “any right sided colonic or terminal ileum involvement”, “isolated right sided colonic or terminal ileum involvement”, “isolated transverse segmental colonic involvement” based on available reported data. These categories were chosen to determine the type of endoscopic procedure necessary to obtain a diagnosis of checkpoint inhibitor-mediated colitis.

Statistical Analysis:

Our primary analysis focused on assessing endoscopic and histologic distribution of checkpoint inhibitor-mediated colitis identified on lower gastrointestinal endoscopy. The pattern of involvement of the gastrointestinal tract was used to determine the diagnostic yield of flexible sigmoidoscopy as compared to full colonoscopy in diagnosing checkpoint inhibitor-mediated colitis. Flexible sigmoidoscopy allows for evaluation of the entire left colon alone, whereas colonoscopy allows for evaluation of the entire colon and terminal ileum. Data was collected and summarized with proportions, means, and medians as noted. The diagnostic yield of flexible sigmoidoscopy was calculated as the proportion of cases with any left sided colonic findings. All data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Office 2016, Microsoft, Redmond, WA).

Results

Single Center Patient Characteristics

Between 7/1/2011 and 2/1/2017, a total of 1135 patients were treated with checkpoint inhibitor therapy at our institution or had been treated elsewhere with subsequent care provided at our institution. Physician-reported checkpoint inhibitor colitis occurred in 8.5% (97/1135 patients) of patients. There were 25 cases of colitis out of 384 (6.5%) patients treated with pembrolizumab, 31 cases out of 469 (6.6%) patients treated with ipilimumab, 11 cases out of 447 (2.4%) patients treated with nivolumab, and 30 cases out of 118 (25.4%) patients treated with ipilimumab/nivolumab combination therapy. A total of 36 patients underwent lower gastrointestinal endoscopic exam for suspected checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis. Thirty-one patients were diagnosed with checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis by lower gastrointestinal endoscopy. Of the patients without features of colitis on lower endoscopy (4 flexible sigmoidoscopy, 1 colonoscopy), one patient was diagnosed with mycophenolate mofetil induced colitis, two patients were found to have isolated features of enteritis on subsequent upper endoscopy, one patient underwent empiric treatment for colitis with clinical improvement, and one patient was clinically diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of the 31 patients with checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis diagnosed by lower endoscopy are presented in table 1. All patients were being treated for advanced melanoma. No patients had a history of inflammatory bowel disease. All patients presented with diarrhea characterized by increased frequency and/or loose consistency of bowel movements. In addition, 29% of patients reported blood in stools, 38.7% reported abdominal pain, and 16.1% reported nausea. Most patients had been started on systemic immunosuppression prior to lower gastrointestinal endoscopy, with 19 (61.3%) patients receiving corticosteroids for a mean 11 days prior to endoscopy. Three patients (9.6%) had received at least 1 dose of Infliximab prior endoscopy.

Table 1.

Case series patient characteristics

| Age, y mean (SD) | 64.9 (8.5) |

| Male, n (%) | 26 (83.8%) |

| Melanoma, n (%) | 31 (100%) |

| Checkpoint Inhibitor Regimen | |

| Ipilimumab, n (%) | 13 (41.9%) |

| Ipilimumab + Nivolumab, n (%) | 12 (38.7%) |

| Pembrolizumab, n (%) | 6 (19.3%) |

| Doses prior to onset of diarrhea, median (range) | 2 (1–20) |

| Time to onset of diarrhea, days median (range) | 39 (11–460) |

| Diarrhea Grade, median (range) | 3 (1–4) |

| Corticosteroid use prior to endoscopy, n (%) | 19 (61.30%) |

| Corticosteroid duration prior to endoscopy, days mean (SD) | 11 (2–53) |

| Infliximab prior to endoscopy, n (%) | 3 (9.60%) |

Endoscopic and Histologic Characteristics

A total of 17 (54.8%) patients with checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis underwent oral purgative bowel preparation with the intention of performing diagnostic colonoscopy. Ultimately, 5 (29.4%) patients underwent an incomplete colonoscopy due to the severity of inflammation encountered in left colon in all cases. Flexible sigmoidoscopy was performed in 14 (45.2%) patients with a standard bowel preparation consisting of 2 tap water or fleet enemas. The most common endoscopic findings were erythema (93.5%), friability (58.6%), congestion (48.2%), and ulcers (37.9%). Consistent with prior studies, the histological findings were variable with the most common reported findings of acute inflammation (58.0%), chronic inflammation (41.9%), lymphocyte infiltration (19.3%), and plasma cell infiltration (16.1%).

The endoscopic and histologic distribution patterns are presented in table 2. The left colon was macroscopically abnormal in 13 (92.8%), 5 (100.0%), and 11 (91.7%) of those undergoing flexible sigmoidoscopy, incomplete colonoscopy, and complete colonoscopy, respectively; in total 29 (93.5%) patients had macroscopic evidence of left sided disease. No patients had macroscopic abnormalities isolated to the right colon. Two patients had normal endoscopic examinations with typical features microscopically only. Microscopically, all patients exhibited left sided colonic features consistent with checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis where segmental biopsies were performed (29/29). In two patients undergoing colonoscopy, random colon biopsies only were performed and the exact disease distribution could not be confirmed.

Table 2.

Case series endoscopic findings

| Macroscopic (Endoscopy) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Flexible sigmoidoscopy | Incomplete Colonoscopy | Full Colonoscopy |

|

| Rectum | 13/14 | 4/5 | 9/12 |

| Sigmoid | 11/14 | 5/5 | 11/12 |

| Descending | 4/7 | 4/4 | 10/12 |

| Left | 13/14 | 5/5 | 11/12 |

| Transverse | 1/1 | . | 11/12 |

| Ascending/Cecum | . | . | 10/12 |

| Ileum | . | . | 6/9 |

| Right | 1/1 | . | 11/12 |

| Microscopic (Histology) | |||

| Left | 14/14 | 5/5 | 10/10* |

| Right | . | . | 10/10* |

| TI | . | . | 4/6 |

Data presented as proportion of patients with abnormal findings over number of patients with evaluation of specific lower gastrointestinal segment (n/n). Left side includes rectum, sigmoid, and descending colon. Right side includes transverse colon, ascending colon, cecum, and terminal ileum (TI).

2 patients in the full colonoscopy group had random colon biopsies only, therefore cannot determine histologic distribution

Management of Checkpoint Inhibitor-Induced Colitis:

Most patients with endoscopically diagnosed colitis (67.7%) were hospitalized at the time of endoscopic evaluation and 87.1% of patients received systemic corticosteroids for a median 77 days (range 1–279) for treatment of colitis. A total of 19 (61.3%) patients required at least one dose (median 1, range 1–3) of Infliximab for treatment of corticosteroid-refractory colitis. Among patients clinically diagnosed with colitis that had not undergone endoscopic evaluation, 98.3% (60/61) were treated with corticosteroids and 39.3% patients received at least one dose of infliximab. The management of checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis was directed by the treating oncologists. There were 2 intestinal perforations and 2 bowel resections, which were likely related to checkpoint inhibitor induced colitis, among patients who did not undergo endoscopic evaluation, similar to the group that had undergone endoscopy (2/36 with perforation and bowel resection).

Systematic Review Search Results

Of the 1892 unique studies identified using our search criteria, 61 studies fulfilled our inclusion criteria and were included in the qualitative analysis (38 full text articles, 23 in abstract form)8,10,14–72. Results of our search strategy our depicted in figure 1. Of these studies, 18 were case series and 43 were individual case reports.

Systematic Review Patient Characteristics

The included studies described the lower gastrointestinal distribution of 226 cases of checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis. Abbreviated study findings are presented in Table 3 with comprehensive study findings reported in Supplementary Table 1. 125 patients underwent colonoscopy and 101 patients underwent flexible sigmoidoscopy. Clinical severity was mild in only 2.6% of cases, moderate-severe in 84.1%, and not able to be determined in 13.3%. By far the most commonly reported treatment regimen was Ipilimumab monotherapy (213/226 cases). There were 3 cases with Ipilimumab/Nivolumab combination therapy, 5 cases with Tremelimumab, 2 cases with Nivolumab, and 3 cases with either Pembrolizumab or Nivolumab.

Table 3.

Systematic review enterocolitis distribution.

| Author, y | Medication (n) | Clinical Severity |

LC (any) | RC/TI (Any) |

RC/TI (Isolated) |

Transverse (Isolated) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild | Moderate- Severe |

ND | n | ||||||

| Colonoscopy | |||||||||

| Agarwal, 2016* | IPI | . | . | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 0 | 0 |

| Bamias, 2017 | IPI | . | 5 | . | 5 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| De Felice, 2015 | IPI | . | 4 | . | 4 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Jain, 2014* | IPI | . | 7 | . | 7 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Klair, 2016 | IPI | . | 2 | . | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Marthey, 2016 | IPI | . | 33 | . | 33 | 32 | 27 | ≤1 | 0 |

| Rastogi, 2014 | IPI | . | 3 | . | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Satoh, 2017 | IPI | . | 2 | . | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Sidhu, 2015* | IPI | . | 3 | . | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Tondon, 2016* | IPI | . | 6 | . | 6 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Verschuren, 2016 | IPI | . | 8 | . | 8 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Single Case Reports | IPI (25), NIV (2), IPI/NIV (2), TRE (1) | 2 | 27 | 1 | 30 | 29 | 22 | 1 | 0 |

| Totals | 2 | 100 | 23 | 125 | 122 | 108 | 3 | 0 | |

| Flexible Sigmoidoscopy | |||||||||

| Bamias, 2017 | IPI | . | . | 3 | 3 | 3 | . | . | . |

| Hillock, 2016 | IPI | . | 12 | . | 12 | 12 | . | . | . |

| Jain, 2014* | IPI | . | 4 | . | 4 | 4 | . | . | . |

| Johnston, 2009 | IPI (1), TRE (4) | . | 5 | . | 5 | 5 | . | . | . |

| Lord, 2010 | IPI | 2 | 7 | . | 9 | 9 | . | . | . |

| Maker, 2005 | IPI | 2 | 2 | 2 | . | . | . | ||

| Marthey, 2016 | IPI | . | 2 | 4 | 6 | 6 | . | . | . |

| O’Connor, 2016 | IPI | . | 7 | . | 7 | 6 | . | . | 1 |

| Sidhu, 2015* | IPI (11), PEM or NIV (3) | . | 14 | . | 14 | 14 | . | . | . |

| Verschuren, 2016 | IPI | 1 | 18 | . | 19 | 19 | . | . | . |

| Single Case Reports | IPI (19), IPI/NIV (1) | 1 | 19 | 20 | 20 | . | . | . | |

| Totals | 4 | 90 | 7 | 101 | 100 | . | . | 1 | |

| Overall Totals | 6 | 190 | 30 | 226 | 222 | 108 | 3 | 1 | |

Indicates abstract only

IPI: Ipilimumab, TRE: Tremelimumab, NIV: Nivolumab, PEM: Pembrolizumab

ND: Not Determined

LC: Left Colon, RC: Right Colon, TI: Terminal Ileum

Any: indicates any involvement, Isolated: Indicates isolated involvement of designated region

Lower Gastrointestinal Distribution of Colitis

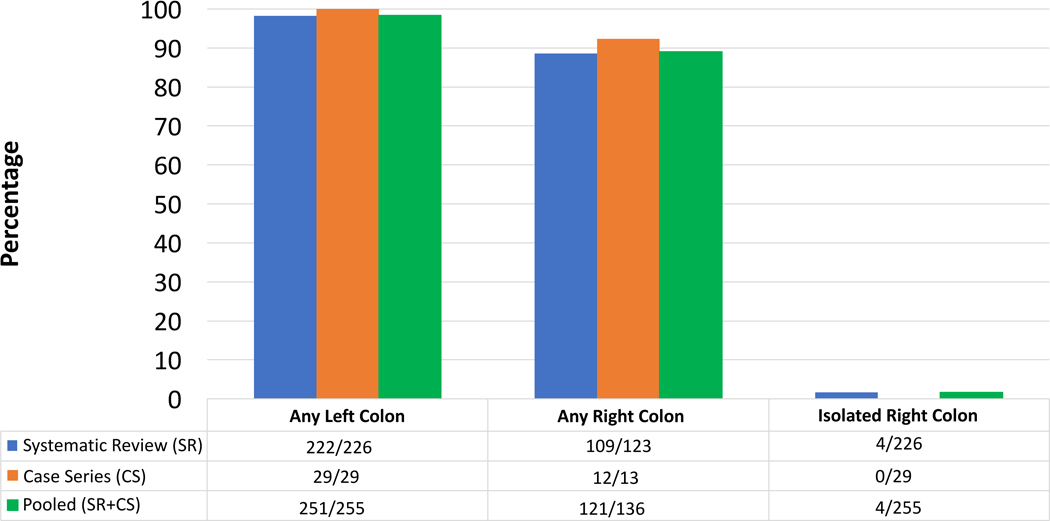

Among the 125 patients with colitis that underwent colonoscopy, 97.6% had left sided involvement, 86.4% had any right sided or terminal ileal involvement, and 2.4% had isolated right sided colonic or terminal ileal involvement based on reported macroscopic and microscopic findings. Among the 101 patients with colitis that underwent flexible sigmoidoscopy, 99.0% had left sided involvement and 1.0% had isolated segmental transverse colonic involvement based on reported macroscopic and microscopic findings. Taken together, left sided colonic involvement was seen in 98.2% of patients with colitis undergoing endoscopy.

Microscopic Inflammation in the Setting of a Normal Endoscopy

We identified 4 studies that described cases of colitis with microscopic evidence of inflammation but normal endoscopic appearance of the lower gastrointestinal tract 42,63,73,74. In one series of 36 patients, 36% had microscopic abnormalities alone with normal endoscopy74. All patients in this series had grade 3–4 disease. A separate series of 35 patients identified 22.8% of patients with microscopic abnormalities but no macroscopic findings73. In our cohort there were 2 patients with microscopic findings consistent with colitis but normal endoscopy. Both individuals had undergone outpatient endoscopy and had grade 1–2 diarrhea. One patient had received Ipilimumab and the other Pembrolizumab. Neither patient had been treated with corticosteroids or Infliximab prior to endoscopy.

Isolated Upper GI Tract Disease

While not a primary study outcome, we identified 4 reports describing 5 patients with checkpoint inhibitor-induced isolated upper gastrointestinal tract inflammation 74–77. All patients reported symptomatic diarrhea; one patient with esophageal involvement also reported dysphagia. Predominant histologic features reported included lymphocytes and plasma cell infiltration. All patients underwent concomitant macroscopic and microscopic lower GI evaluation with endoscopy or ileocolectomy in one case. At our center we identified 2 patients presenting with diarrhea after checkpoint inhibitor exposure with isolated upper GI inflammation (duodenum in both cases) with unremarkable lower gastrointestinal evaluation with biopsy that were determined to have checkpoint inhibitor-induced enteritis.

Discussion

Checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis is a common clinical entity often occurring shortly after initiation of therapy in patients with advanced cancer. The optimal diagnostic evaluation sequence has not been determined. Following exclusion of alternative causes or infections, endoscopy is often pursued for a diagnosis. The type of initial endoscopic procedure pursued has relevant clinical implications. Flexible sigmoidoscopy can be performed rapidly with minimal or no bowel preparation or procedural sedation. Colonoscopy requires an oral bowel preparation, often taking 24 hours to coordinate, and typically is performed with sedation to address patient discomfort. Furthermore, colonoscopy has been associated with higher risk of colonic perforation than flexible sigmoidoscopy in several studies.78,79 Severe colonic inflammation may further heighten this risk80. For ill hospitalized patients or on an outpatient basis, sigmoidoscopy can often be performed quickly, more comfortably, at lower financial cost, and likely lower risk of complication relative to colonoscopy.

We report a series of 31 patients at our institution with moderate to severe checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis diagnosed by lower gastrointestinal endoscopy. In 93.5% of patients (29/31) there was macroscopic evidence of left sided disease. No patients (0/31) had macroscopic abnormalities isolated to the right colon. All patients who underwent segmental colonic biopsies had microscopic evidence of disease in the left colon (29/29). A systematic review of the literature identified 226 cases of checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis. Left sided colonic involvement was present in 98.2% of patients. Pooling our single center experience with the reviewed case series, flexible sigmoidoscopy with biopsy would be sufficient to diagnose >98% of patients with checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Colonic Distribution of Checkpoint Inhibitor Colitis

The use and timing of endoscopic evaluation of suspected checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis is not uniform. At our institution, we identified 24 patients with suspected colitis on clinical grounds alone that were empirically treated with corticosteroids and subsequently received Infliximab without undergoing endoscopy. In a recent retrospective study comparing endoscopy and Computerized Tomography (CT) in checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis, investigators suggested that CT may be a suitable diagnostic tool for this condition based on concordance of abnormal findings on exams 81. We argue that endoscopic evaluation is important for several reasons in these patients. First, flexible sigmoidoscopy is a quick, safe, relatively low-cost procedure that can definitively confirm the diagnosis in most patients. Second, endoscopy can evaluate for cytomegalovirus infection, which can present similarly and has been reported in patients treated with checkpoint inhibitors who have received additional immunosuppression for other iRAE31. Third, endoscopy can evaluate for other conditions such as metastasis, and other drug induced colitis that could present similarly. At our institution, endoscopy identified one patient with mycophenolate mofetil colitis who had previously been managed as checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis. Fourth, two recent studies have identified the presence of colonic ulcers on endoscopy as a predictor for need for infliximab therapy, demonstrating a possible role for endoscopy in guiding initial immunosuppressive therapy82,83. Finally, moderate to severe colitis often leads to treatment with prolonged immunosuppression and withdrawal of immunotherapy, necessitating an accurate diagnosis.

Our study has several limitations. Most patients in our cohort and systematic review had severe disease with grade 3 to 4 gastrointestinal toxicity and were hospitalized at the time of endoscopy. The distribution pattern and endoscopic findings may not be reflective of patients with milder disease. There may be selection bias as only 37% of patients with suspected colitis in our cohort underwent endoscopic evaluation. Many patients undergo flexible sigmoidoscopy rather than full colonoscopy to evaluate this condition. Because of this, some patients with checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis with isolated right sided findings could have been missed and therefore not reported in the literature. As there was data available on 125 patients that underwent full colonoscopy with only 2.4% of cases with isolated right sided involvement we believe that this is rare. Also, studies often did not report immunosuppression exposure (either to treat colitis or other IRAE) prior to endoscopic exams, which may have affected macroscopic and microscopic findings.

In conclusion, moderate to severe checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis predominantly involves the left colon. Patients are often treated with prolonged courses of corticosteroids and infliximab for refractory disease. Given the implications of diagnosis (checkpoint inhibitor treatment cessation, need for high intensity immunosuppression, potential immunosuppression related complications), confidently identifying or excluding moderate to severe checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis is essential. Flexible sigmoidoscopy with biopsy is sufficient to identify >98% of cases of moderate to severe colitis with lower gastrointestinal involvement and should be considered as the primary diagnostic test after gastrointestinal infections are excluded. Mucosal biopsies should be obtained regardless of macroscopic findings. If sigmoidoscopy with biopsy is normal, then combined upper endoscopy and ileocolonoscopy with biopsy can be performed to optimize diagnostic yield.

Supplementary Material

Comprehensive systematic review enterocolitis distribution

* Indicates abstract only

IPI: Ipilimumab, TRE: Tremelimumab, NIV: Nivolumab, PEM: Pembrolizumab

ND: Not Determined

LC: Left Colon, RC: Right Colon, TI: Terminal Ileum

Any: indicates any involvement, Isolated: Indicates isolated involvement of designated region

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: National Institutes of Health K23-DK101687(Stidham)

Abbreviations:

- CTLA-4

Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte-associated antigen-4

- PD-1

Programmed cell death protein-1

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this manuscript to declare

References:

- 1.Postow MA, Callahan MK, Wolchok JD. Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Cancer Therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(17):1974–1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta A, De Felice KM, Loftus EV, et al. Systematic review: colitis associated with anti-CTLA-4 therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42(4):406–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eggermont AMM, Chiarion-Sileni V, Grob J-J, et al. Prolonged Survival in Stage III Melanoma with Ipilimumab Adjuvant Therapy. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1845–1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab or Monotherapy in Untreated Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(1):23–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brahmer JR, Lacchetti C, Schneider BJ, et al. Management of Immune-Related Adverse Events in Patients Treated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2018;36(17):1714–1768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verschuren EC, van den Eertwegh AJ, Wonders J, et al. Clinical, Endoscopic, and Histologic Characteristics of Ipilimumab-Associated Colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(6):836–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marthey L, Mateus C, Mussini C, et al. Cancer Immunotherapy with Anti-CTLA-4 Monoclonal Antibodies Induces an Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10(4):395–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hillock NT, Heard S, Kichenadasse G, et al. Infliximab for ipilimumab-induced colitis: A series of 13 patients. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. December 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yanai S, Nakamura S, Matsumoto T. Nivolumab-Induced Colitis Treated by Infliximab. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. September 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gondal B, Patel P, Gallan A, et al. Gastrointestinal adverse effects of immunomodulation: Acute colitis with immune check point inhibitor nivolumab. Inflammatory Bowel Dis. 2016;22:S12–S13. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baroudjian B, Lourenco N, Pagès C, et al. Anti-PD1-induced collagenous colitis in a melanoma patient. Melanoma Res. 2016;26(3):308–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanauer DA, Mei Q, Law J, et al. Supporting information retrieval from electronic health records: A report of University of Michigan’s nine-year experience in developing and using the Electronic Medical Record Search Engine (EMERSE). J Biomed Inform. 2015;55:290–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lord JD, Hackman RC, Moklebust A, et al. Refractory colitis following anti-CTLA4 antibody therapy: analysis of mucosal FOXP3+ T cells. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(5):1396–1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sidhu M, Mersaides T, Liniker E, et al. Infliximab for the treatment of Ipilimumab (anti CTLA-4) and Nivolumab/Pembrolizumab (anti PD-1) associated colitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:139.25040896 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agarwal A, Maru D. Histologpic spectrum of ipilimumab associated colitis is narrow and resembles inflammatory bowel disease. Lab Invest. 2016;96:158A–159A.26813171 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bakeri H, Olson E, Ihunnah C, et al. A melancholy colitis with a curious REMI-DY. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2016;111:S662–S663. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bamias G, Delladetsima I, Perdiki M, et al. Immunological Characteristics of Colitis Associated with Anti-CTLA-4 Antibody Therapy. Cancer Investigation. 2017;3:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balaphas A, ResteIlini S, Robert-Yap J, et al. A Case of Ipilimumab-induced Anorectal Fistula. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10(4):501–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barina AR, Bashir MR, Howard BA, et al. Isolated recto-sigmoid colitis: a new imaging pattern of ipilimumab-associated colitis. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2016;41(2):207–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beniwal-Patel P, Matkowskyj K, Caldera F. Infliximab Therapy for Corticosteroid-Resistant Ipilimumab-Induced Colitis. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2015;24(3):274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng R, Cooper A, Kench J, et al. Ipilimumab-induced toxicities and the gastroenterologist. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30(4):657–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Felice K, Raffals L. High dose budesonide in steroid refractory ipilimumab-induced colitis. Inflammatory Bowel Dis. 2013;19:S26. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao J, He Q, Subudhi S, et al. Review of immune-related adverse events in prostate cancer patients treated with ipilimumab: MD Anderson experience. Oncogene. 2015;34(43):5411–5417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao Y, Sharma S, Boparai R. Dire diarrhea: Ipilimumab induced colitis and its management. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:S345. [Google Scholar]

- 25.García-Varona A, Odze RD, Makrauer F. Lymphocytic colitis secondary to ipilimumab treatment. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(2):E15–E16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gupta A, Khanna S. Ipilimumab-associated colitis or refractory Clostridium difficile infection? BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hinds A, Ahmad D, Muenster J, et al. Ipilimumab-induced colitis: A rare but serious side effect. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2013;108:S374–S375. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jain A, Lipson EJ, Sharfman W, et al. Clinical features and treatment of immune mediated colitis in metastatic melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab: Retrospective review of a single-center experience. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(5):S–352. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klair JS, Girotra M, Hutchins LF, et al. Ipilimumab-Induced Gastrointestinal Toxicities: A Management Algorithm. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61(7):2132–2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koch C, Paetzold S, Trojan J. Enterocolitis in a patient being treated with ipilimumab for metastatic melanoma. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(2):298+504–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lankes K, Hundorfean G, Harrer T, et al. Anti-TNF-refractory colitis after checkpoint inhibitor therapy: Possible role of CMV-mediated immunopathogenesis. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5(6):e1128611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maker AV, Phan GQ, Attia P, et al. Tumor Regression and Autoimmunity in Patients Treated With Cytotoxic T Lymphocyte–Associated Antigen 4 Blockade and Interleukin 2: A Phase I/II Study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12(12):1005–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marthey L, Mateus C, Mussini C, et al. Cancer Immunotherapy with Anti-CTLA-4 Monoclonal Antibodies Induces an Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10(4):395–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCutcheon. Infectious Colitis Associated With Ipilimumab Therapy. Gastroenterology Research. 2014:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Minor DR, Puzanov I, Callahan MK, et al. Severe gastrointestinal toxicity with administration of trametinib in combination with dabrafenib and ipilimumab. Pigment Cell & Melanoma Research. 2015;28(5):611–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muhammad A, Reed J, Vidyarthi G, et al. Drug induced colon injury (DICI): A case of ipilimumab induced immune related colitis. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2012;107:S456. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nancey S, Boschetti G, Cotte E, et al. Blockade of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 by ipilimumab is associated with a profound long-lasting depletion of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells: A mechanistic explanation for ipilimumab-induced severe enterocolitis? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(8):E1598–E1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Penumetsa K, Ponugoti S, Reynolds G. Ipilimumab-induced colitis with concomitant clostridium difficile infection. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2013;108:S392. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pocha C, Roat J, Viskocil K. Immune-mediated colitis: Important to recognize and treat. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8(2):181–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rastogi P, Sultan M, Charabaty AJ, et al. Ipilimumab associated colitis: An IpiColitis case series at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(14):4373–4378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rini BI, Stein M, Shannon P, et al. Phase 1 dose-escalation trial of tremelimumab plus sunitinib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2010;117(4):758–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Romain PES, Salama AKS, Lynn Ferguson N, et al. Ipilimumab-Associated lymphocytic colitis: A case report. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;5(1):44–46. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sampath AM. A Rare Presentation of Severe Colitis with Ipilimumab Therapy. American Journal Of Gastroenterology. 2013;108:S399. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanderson K, Scotland R, Lee P, et al. Autoimmunity in a Phase I Trial of a Fully Human Anti-Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Antigen-4 Monoclonal Antibody With Multiple Melanoma Peptides and Montanide ISA 51 for Patients With Resected Stages III and IV Melanoma. JCO. 2005;23(4):741–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Slangen RM, Van Den Eertwegh AJ. Diarrhoea in a patient with metastatic melanoma: Ipilimumab ileocolitis treated with infliximab. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2013;4(3):80–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Satoh T, Ohno K, Kurokami T. Endoscopic Findings of Ipilimumab-Induced Colitis. Dig Endosc. January 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sprung B, Sathyamurthy A, Lewis J, et al. A case of perforating ipilimumab-induced autoimmune colitis. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2014;109:S409. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sreepati G, Kalra M, Aggarwal A. Abdominal Imaging Is Insensitive in Diagnosis of Ipilimumab-Induced Colitis. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2014;109:S428. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tondon R, Shroff SG, Furth EE, et al. Ipilimumab induced perforating colitis: Severe cases mimic crohn disease and ulcerative colitis. Lab Invest. 2016;96:203A. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Uslu U, Agaimy A, Hundorfean G, et al. Autoimmune colitis and subsequent CMV-induced hepatitis after treatment with ipilimumab. J Immunother. 2015;38(5):212–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Venditti O, De Lisi D, Caricato M, et al. Ipilimumab and immune-mediated adverse events: A case report of anti-CTLA4 induced ileitis. BMC Cancer. 2015;15(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Verschuren EC, Van Den Eertwegh AJ, Wonders J, et al. Clinical, Endoscopic, and Histologic Characteristics of Ipilimumab-Associated Colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(6):836–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yanai S, Nakamura S, Matsumoto T. Nivolumab-Induced Colitis Treated by Infliximab. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(4):e80–e81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Amer S, Horsley-Silva JL, Noelting J, et al. Ipilimumab-Induced Colitis. American Journal Of Gastroenterology. 2015;110:S282. [Google Scholar]

- 55.De Felice KM, Gupta A, Rakshit S, et al. Ipilimumab-induced colitis in patients with metastatic melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2015;25(4):321–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Haider A, O’Riordan K. Ipilimumab-induced colonic perforation. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2014;109:S421–S422. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Koya HH, Varghese D, John S. A case of severe enterocolitis secondary to a novel biological agent. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2013;108:S406–S407. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hodi FS, Butler M, Oble DA, et al. Immunologic and clinical effects of antibody blockade of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 in previously vaccinated cancer patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(8):3005–3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hsieh AHC, Ferman M, Brown MP, et al. Vedolizumab: A novel treatment for ipilimumab-induced colitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Johnston RL, Lutzky J, Chodhry A, et al. Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 antibody-induced colitis and its management with infliximab. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54(11):2538–2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Khanijow V, Chablaney S, Bashir S, et al. Ipilimumab enterocolitis: An unusual case of colonic perforation and death. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2015;110:S147. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Leggett C, Hart P, Mounajjed T, et al. I pilimumab Induced Enterocolitis - A Novel Cause of Diarrhea. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2011;106:S319. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lord JD, Hackman RC, Moklebust A, et al. Refractory colitis following anti-CTLA4 antibody therapy: Analysis of mucosal FOXP3+ T cells. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(5):1396–1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Martinez-Balzano C Management of ipilimumab-induced colitis with concurrent clostridium difficile infection. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2012;107:S468. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mitchell KA, Kluger H, Sznol M, et al. Ipilimumab-induced perforating colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47(9):781–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Murakami T, Pugh J, Ozden N, et al. Mimicking inflammatory bowel disease during treatment of metastatic melanoma: Immune mediated ipilimumab-induced colitis. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2013;108:S386–S387. [Google Scholar]

- 67.O’Connor A, Marples M, Mulatero C, et al. Ipilimumab-induced colitis: experience from a tertiary referral center. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2016;9(4):457–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pagès C, Gornet JM, Monsel G, et al. Ipilimumab-induced acute severe colitis treated by infliximab. Melanoma Res. 2013;23(3):227–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ryan D, Pasupuleti C, Butnariu M. Endoscopic remission after infliximab treatment in a patient with ipilimumab-induced colitis. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2016;111:S812. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Spain L, Walls G, Messiou C, et al. Efficacy and toxicity of rechallenge with combination immune checkpoint blockade in metastatic melanoma: a case series. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2017;66(1):113–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tsiaras A Case of the month. Autoimmune colitis secondary to CTLA-4 blockade. JAAPA. 2011;24(8):68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yarze J, Stoutenburg J. Ipilimumab-associated Colitis. American Journal Of Gastroenterology. 108(Supplement 1):S357. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Spain L, Diem S, Khabra K, et al. Patterns of steroid use in diarrhoea and/or colitis (D/C) from immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICPI). Ann Oncol. 2016;27. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Beck KE, Blansfield JA, Tran KQ, et al. Enterocolitis in patients with cancer after antibody blockade of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4. JCO. 2006;24(15):2283–2289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Messmer M, Upreti S, Tarabishy Y, et al. Ipilimumab-induced enteritis without colitis: A new challenge. Case Rep Oncol. 2016;9(3):705–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Venditti O, De Lisi D, Caricato M, et al. Ipilimumab and immune-mediated adverse events: a case report of anti-CTLA4 induced ileitis. BMC Cancer. 2015;15(1):87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Boike J, Dejulio T. Severe Esophagitis and Gastritis from Nivolumab Therapy. ACG Case Rep J. 2017;4:e57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gatto NM, Frucht H, Sundararajan V. Risk of perforation after colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy: a population-based study. J Natl Cancer Institute. 2003;95(3):230–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lüning TH, Keemers-Gels ME, Barendregt WB, et al. Colonoscopic perforations: a review of 30,366 patients. Surg Endosc. 2007;21(6):994–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Navaneethan U, Kochhar G, Phull H. Severe disease on endoscopy and steroid use increase the risk for bowel perforation during colonoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Journal of Crohn’s Colitis. 2012;6(4):470–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Garcia-Neuer M, Marmarelis ME, Jangi SR, et al. Diagnostic Comparison of CT Scans and Colonoscopy for Immune-Related Colitis in Ipilimumab-Treated Advanced Melanoma Patients. Cancer Immunol Res. 2017;5(4):286–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Abu-Sbieh H, Ali FS, Luo W, et al. Importance of endoscopic and histological evaluation in the management of immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6(95):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Geukes Foppen MH, Rozeman EA, Van Wilpe S, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibition-related colitis: symptoms, endoscopic features, histology and response to management. ESMO Open. 2018;3(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Comprehensive systematic review enterocolitis distribution

* Indicates abstract only

IPI: Ipilimumab, TRE: Tremelimumab, NIV: Nivolumab, PEM: Pembrolizumab

ND: Not Determined

LC: Left Colon, RC: Right Colon, TI: Terminal Ileum

Any: indicates any involvement, Isolated: Indicates isolated involvement of designated region