Abstract

Syncytin-A and -B are envelope genes of retroviral origin that have been captured in evolution for a role in placentation. They trigger cell-cell fusion and were shown to be essential for the formation of the syncytiotrophoblast layer during mouse placenta formation. Syncytin-A and -B expression has been described in other tissues and their highly fusogenic properties suggested that they might be involved in the fusion of other cell types. Here, taking advantage of mice knocked out for syncytin-B, SynB−/− mice, we investigated the potential role of syncytin-B in the fusion of cells from the monocyte/macrophage lineage into multinucleated osteoclasts (OCs) -in bone- or multinucleated giant cells -in soft tissues. In ex vivo experiments, a significant reduction in fusion index and in the number of multinucleated OCs and giant cells was observed as soon as Day3 in SynB−/− as compared to wild-type cell cultures. Interestingly, the number of nuclei per multinucleated OC or giant cell remained unchanged. These results, together with the demonstration that syncytin-B expression is maximal in the first 2 days of OC differentiation, argue for syncytin-B playing a role in the fusion of OC and giant cell mononucleated precursors, at initial stages. Finally, ex vivo, the observed reduction in multinucleated OC number had no impact on the expression of OC differentiation markers, and a dentin resorption assay did not evidence any difference in the osteoclastic resorption activity, suggesting that syncytin-B is not required for OC activity. In vivo, syncytin-B was found to be expressed in the periosteum of embryos at embryonic day 16.5, where TRAP-positive cells were observed. Yet, in adults, no significant reduction in OC number or alteration in bone phenotype was observed in SynB−/− mice. In addition, SynB−/− mice did not show any change in the number of foreign body giant cells (FBGCs) that formed in response to implantation of foreign material, as compared to wild-type mice. Altogether the results suggest that in addition to its essential role in placenta formation, syncytin-B plays a role in OCs and macrophage fusion; yet it is not essential in vivo for OC and FBGC formation, or maintenance of bone homeostasis, at least under the conditions tested.

Keywords: Endogenous retrovirus, Envelope gene, Syncytin, Cell-cell fusion, Osteoclast, Giant cell

Highlights

-

•

Syncytin-A and syncytin-B, captured retroviral envelope genes, are expressed during murine osteoclast differentiation.

-

•

Syncytin-B is involved in fusion processes driving both osteoclast and giant cell formation.

-

•

Invalidation of syncytin-B decreases ex vivo fusion indexes of both osteoclast and giant cell precursors.

-

•

Invalidation of syncytin-B does not impair ex vivo and in vivo osteoclast function.

-

•

Invalidation of syncytin-B does not impair in vivo FBGC formation

1. Introduction

Syncytins are genes originating from endogenous retroviruses (ERVs). ERVs are the remnants of ancient infections by retroviruses that integrated their genomes into the germline of their host, and now represent up to 10% of vertebrate genomes (Stoye, 2012). Whereas the great majority of ERV genes are defective and/or transcriptionally repressed, a few examples exist of single copy retroviral genes which were conserved and have remained functional for millions of years of evolution, suggesting an important physiological role. This is the case of the syncytin genes, encoding the envelope (Env) proteins of ERVs that have been independently captured in diverse mammalian species for a key physiological role in placenta formation. Two syncytin genes were first identified in humans (syncytin-1 and -2) (Blond et al., 2000; Mi et al., 2000; Blaise et al., 2003) and then in the mouse (syncytin-A and -B) (Dupressoir et al., 2005; Vernochet et al., 2014), and additional syncytin genes were thereafter found in all the mammalian lineages where they have been searched for, as well as in marsupials (reviewed in Ref (Lavialle et al., 2013)). Syncytin genes are clearly not orthologous genes, originating from distinct retroviruses involved in independent integration events in the course of evolution. Syncytin proteins have fusogenic properties, inherited from the Env protein of their retroviral ancestors, and are able to induce cell-cell fusion by interacting with their receptors at the surface of target cells. They have been shown to be responsible for the formation of the placental syncytiotrophoblast, a multinucleated cell layer formed by the fusion of mononucleated cytotrophoblasts at the feto-maternal interface. Mice knocked out for either of the two syncytin genes displayed impaired placental trophoblast fusion. Yet, whereas loss of syncytin-A had dramatic effects leading to in utero lethality at mid gestation (Dupressoir et al., 2009), syncytin-B deletion resulted in only mild effects, with syncytin-B KO (SynB−/−) mice being viable and showing limited in utero growth retardation (Dupressoir et al., 2011). Although syncytins are mainly expressed in placental trophoblast cells, low levels of expression can be detected in other tissues, suggesting that these genes could be involved in other cell fusion processes. In higher organisms, besides placental trophoblast fusion, cell-cell fusion processes are also involved in myoblast fusion for muscle fiber formation and repair, egg-sperm fusion for fertilization, and fusion of macrophage/monocyte-derived precursors for the formation of multinucleated osteoclasts (OCs) in bone and of multinucleated giant cells in soft tissues (reviewed in Ref (Shinn-Thomas and Mohler, 2011); see also (Herrtwich et al., 2016) for an alternative explanation of giant cell formation). Recent data obtained from the analysis of SynB−/− mice demonstrated the implication of murine syncytins in myoblast fusion, with an unexpected sex-dependent effect (Redelsperger et al., 2016). Moreover, it was recently reported that human syncytin-1 is involved in human OC fusion ex vivo (Søe et al., 2011; Søe et al., 2015; Møller et al., 2017), but the biological relevance of these data to the in vivo situation in humans is difficult to assess. This led us to take advantage of the murine syncytin KO models to explore in vivo the role of syncytins in the OC and giant cell multinucleation processes. In higher organisms, precursors of the macrophage/monocyte lineage differentiate in vivo into either bone-resorbing OCs - which cooperate with bone-forming osteoblasts for bone remodeling and homeostasis -, or multinucleated giant cells that form in response to inflammation, infection or implantation of foreign materials (called in the latter case foreign body giant cells or FBGCs). Both processes can be induced in ex vivo culture systems by using M-CSF and RANKL for OC differentiation, and GM-CSF plus IL-4 for FBGC formation (Sheikh et al., 2015). These processes are the result of complex, multistep events involving cell recruitment, proliferation, attachment, fusion of mononuclear precursors and finally differentiation into mature, multinucleated bone-resorbing or inflammatory cells. Here, using the SynB−/− mouse model, we explored the role of syncytin-B in OC and FBGC differentiation, using both ex vivo and in vivo experiments performed as early as embryonic day 16.5 (E 16.5) up to 24 weeks of age in wild-type and SynB−/− mice. The results presented here demonstrate that syncytin-B is mostly expressed in the first stages of osteoclastic differentiation and plays a role in OC and giant cell formation ex vivo. Yet, SynB−/− mice do not display any altered bone phenotype at either 6, 12 or 24 weeks of age, nor any defect in FBGC formation.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Animals

Targeted mutagenesis of the syncytin-B gene was described previously (Dupressoir et al., 2011). Briefly, the mouse syncytin-B ORF (carried by a single 1.8-kb exon) was deleted by homologous recombination using a strategy based on the Cre/LoxP recombination system for generating KO mice. Male and female mice were on a mixed 129/Sv C57BL/6 background. The heterozygous mice are viable and fertile, and were mated to generate the wild type (WT) and KO mice (SynB−/−) used in the study. Both males and females were used to carry out the study. Experiments were performed on same-sex and same-litter WT and SynB−/− individuals in order to minimize possible lineage effects and compare genetically related individuals. The mice were housed under controlled conditions at 24 °C with a 12-h light/dark cycle, and were allowed free access to food and water in full compliance with the French government animal welfare policy. All the experiments were approved by the Ethics committee of the Paris Diderot University and Integrated Research Cancer Institute in Villejuif (IRCIV).

2.2. Measurement of bone mineral density by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) analysis was carried out under anesthesia. Total body, whole femur, and caudal vertebral bone mineral densities (BMD) (mg/cm2) were measured using a PIXImus Instrument (Lunar; software version 1.44) under ultra–high resolution mode (resolution 0.18 × 0.18 mm). The precision and reproducibility of the instrument had previously been evaluated by calculating the coefficient of variation of repeated DXA measurements. The coefficient of variation was <2% for all of the parameters evaluated. A phantom was scanned daily to monitor the stability of the measurements.

2.3. Histomorphometry

The animals were killed by exsanguination under anesthesia. The left femur was excised, and the surrounding soft tissue was cleaned off. After fixation in 70% ethanol at 4 °C, femurs were trimmed and the bone distal halves were post-fixed in 70% ethanol, dehydrated in xylene at 4 °C, and embedded without demineralization in methyl methacrylate. Histomorphometric parameters were measured as recommended by the Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research (Dempster et al., 2013; Parfitt et al., 1987) on 5-mm thick sections using a Nikon microscope interfaced with a software package from Microvision Instruments. For tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) detection, sections were stained with 50 mM sodium tartrate and naphthol AS-TR phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich). Measurements of the trabecular bone were performed in a region of the secondary spongiosa. OC number and bone surface were measured according to Parfitt's nomenclature. We also counted the number of nuclei per OC.

2.4. Microcomputed tomography

Femurs obtained from 6 weeks old mice were dissected free of soft tissue and analyzed by X-ray microcomputed tomography (μCT) with a SkyScan 1072 scanner and subsequently reconstructed and analyzed with the associated analysis software NRecon and CTAn (Bruker, Antwerp, Belgium). Briefly, the X-ray source operated at 60 kV and 100 μA with a 0.5 mm Al filter. Image acquisition was performed at a 6 μm resolution with a 0.5° rotation between frames. During scanning, the samples were enclosed in a tightly fitting foam wrap to prevent movement and dehydration. Thresholding was applied to the images to segment the bone from the background. Scans were reconstructed with 20% beam hardening and a ring correction factor of 5.

2.5. Resorption marker measurements

Accurate deoxypyridinoline (DPD) measurement requires overnight fasting before urine collection. DPD was measured with IMMULITE Pyrilinks-D in vitro diagnostic reagent (Diagnostic Products). To correct for flow variations, the DPD results were normalized to the urinary creatinine concentration (ADVIA System; Siemens).

2.6. In situ hybridization

Freshly collected hindlimbs of mouse embryos (E16.5) were fixed in 4% (weight/volume) paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Serial sections (7 μm) were either stained for TRAP activity or used for in situ hybridization. For the syncytin-B gene, three PCR-amplified fragments of 414, 511, and 370 bp, designed in the regions the least conserved between the syncytin-A and -B genes were cloned into pGEM-T Easy (Promega) (Vernochet et al., 2014). In vitro synthesis of the antisense and sense riboprobes was performed with SP6 or T7 RNA polymerase and digoxigenin 11-UTP (Roche Applied Science) after cDNA template amplification. Sections were processed, hybridized at 42 °C overnight with the pooled riboprobes (1 μg/mL of each riboprobe), and incubated further overnight at 4 °C with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-digoxigenin antibody Fab fragments (Roche Applied Science). Staining was achieved with the nitroblue tetrazolium and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate phosphatase alkaline substrates as indicated by the manufacturer (Roche Applied Science). To assess the specificity of the syncytin-B probes, they were tested on placenta sections prepared from SynB−/− mice. No staining was observed, indicating that the syncytin-B probe does not cross react with syncytin-A transcripts (data not shown).

2.7. Osteoclast culture from splenocytes and bone marrow cells

In vitro osteoclastogenesis from splenocytes was performed according to Chabbi-Achengli et al., with modifications (Chabbi-Achengli et al., 2012). Briefly, spleen cells were isolated from 6 weeks old WT and SynB−/− mice from the same litter and a cell suspension was obtained using a 70 μm nylon mesh cell strainer (Becton. Dickinson). After a red blood cell lysis step, cells were washed twice with αMEM, and seeded in αMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penincillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin and 1% l-Glutamine in 1- or 8-chamber Labtek at 0.6 × 106 cells/cm2. After being allowed to attach overnight, cultures were fed every 3 days for 14 days, with fresh medium supplemented with M-CSF (25 ng/mL; Preprotech) in the presence or absence of RANKL (30 ng/mL; Preprotech). In this system, splenocytes proliferate, differentiate into mononuclear TRAP-positive cells, and fuse to form OC-like cells after 2 weeks. For resorption assays, spleen cells (0.32 × 106 cells/cm2) were plated on dentin slices as previously described (Chabbi-Achengli et al., 2012). Briefly, the slices (Immunodiagnostic Systems, France) were cleaned in ethanol and each slice was then placed into 96-well plates. Splenocytes were added into each well, cultured in complete αMEM with M-CSF (25 ng/mL) and RANKL (100 ng/mL) and maintained for 14 days at 37 °C under 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator. The last 24 h of culture were carried out in the presence of 10% CO2. The slices were then recovered, cleaned by ultrasonication and stained with toluidine blue. The number TRAP-positive cells and the mean resorption area on each slice were counted under a light microscope. Three-dimensional images of resorption pits were yielded using a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope equipped with a Plan Neofluoar 40×/1.3 numerical aperture objective. The depth of the resorption pit was determined using Zeiss LSM Image Browser Version 4.2 (Biosse Duplan et al., 2014).

Murine OC precursor cells were also obtained from the bone marrow of 8 weeks old WT and SynB−/− mice from the same litter. In brief, tibias and femurs were flushed and CD11b + cells were isolated by negative selection using immuno-magnetic separation (CD49b, CD45R, CD3ε, Anti-Ter-119, MACS Miltenyi Biotec). The purity degree of the cellular preparation, evaluated by FACS using CD11b + antibody (Myltenyi Biotec), was always higher than 90%. Cells were seeded in cell culture plates at a density of 5.105 cells/mL in RPMI1640 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FCS, 100 U/mL penincillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin, in the presence of 25 ng/mL M-CSF and 25 ng/mL RANKL (Myltenyi Biotec). Cells were cultivated at 37 °C under 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator during 7 days.

2.8. TRAP activity staining

After 3, 7 and 14 days of culture, cells were washed with PBS, fixed with 4% PFA (Sigma-Aldrich, France) for 10 min at RT, then tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) activity was detected by enzyme histochemistry to assess OC differentiation. Briefly, cells were stained for acid phosphatase, using naphthol ASTR phosphate (Sigma) as a substrate in the presence of 50 mM tartrate and hexazotized pararosaniline (Sigma), and counterstained with methyl green (Sigma). TRAP positive cells were counted under microscope.

2.9. In vivo and ex vivo giant cell formation

25-mm2 Millipore filters (0.45 μm) were implanted subcutaneously in 6 weeks old male and female SynB−/− mice. WT littermates of the same sex, obtained from independent heterozygous matings were used as control. Each mouse received two implants that were placed on each side of their backs. After 4 weeks, implants were excised en bloc, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin and processed for histological analysis by hematoxylin eosin saffron (HES) staining. For each implanted mouse, nuclei of all cells that adhere to the two implants were counted (at least 2000 nuclei per implant were counted). The distribution of these nuclei in cells containing one, two, 3 to 5, 6 to 10, 11 to 20 or >20 nuclei was scored. Multinuclear cells containing >3 nuclei were considered as FBGCs.

Bone marrow mononuclear cells were isolated from tibias and femurs of 8 weeks old WT and SynB−/− mice from the same litter and of the same sex. After red blood cells lysis step, 5 × 105 cells were seeded in 10-cm sterile Petri dishes and cultured in RPMI1640 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FCS, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin, and 50 ng/ml M-CSF (Miltenyi) to generate M-CSF-dependent bone marrow-derived macrophage (BMDM) cells. After 7 days, cells were counted and the percentage of cells expressing CD11b + was evaluated by FACS using an FITC-conjugated CD11b + antibody (Myltenyi Biotec). All samples were accompanied by matched isotype control. To induce giant cell formation, BMDM cells were plated at 1.5 × 105 cells/well in 96-well culture plates, in the presence of either GM-CSF (25 ng/mL) alone, or GM-CSF (25 ng/mL) and IL-4 (25 ng/mL) during 3 or 7 days, and then stained with May-Grünwald and Giemsa.

2.10. Fusion indexes

In order to assess OC precursor cell fusion in vitro, we counted the mono-, bi- and multi-nucleated (three or more nuclei) TRAP-positive cells separately. The number of nuclei contained in the TRAP-positive cells was also counted. We defined the fusion index according to the formula: Fusion index (%) = (number of nuclei in multinucleated cells) × 100 / (total number of nuclei in TRAP-positive cells), where multinucleated cells were defined as TRAP-positive cells containing three or more nuclei as previously described (Brazier et al., 2006). For each genotype, WT and SynB−/−, the fusion indexes were determined in 10 microscopic fields of 1 mm2, by counting a total of at least 2500 nuclei.

Giant cell precursor fusion index was calculated as the number of nuclei within multinucleated giant cells × 100 / (total number of nuclei counted). In each experiment, at least 2500 nuclei were counted from random fields.

2.11. RNA extraction and RT-qPCR

Long bones obtained from E16.5 and 6, 12, and 24 weeks old mice were dissected free of soft tissue. The adult epiphyses were cut off, and the bone marrow was flushed out with PBS and bones marrow-less were conserved in RNA later (Ambion). To extract RNA from these samples, bones were removed from RNA later and ground to powder in Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) using a Polytron homogenizer. Bone marrow was centrifuged and the pellet was conserved in Trizol. Thigh muscles were dissected out from 6 weeks old mice, and ground to powder in Trizol. Total RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer's instructions. For mRNA extraction from cell cultures, we used an RNeasy Lipid Tissue Mini Kit (Qiagen). RNA concentration was measured using a NanoDrop® spectrophotometer. For each sample, 1 μg of total RNA was retrotranscribed into cDNA using a cDNA Verso kit (Abgene) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Real-time quantitative PCR assays were performed following MIQE guidelines (Bustin et al., 2009; Vandesompele et al., 2002), using the Absolute SYBR Green Capillary Mix (Abgene) in a Light Cycler 480 (Roche Diagnostics). PCR conditions were 95 °C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min. At the end of the amplification reaction, melting curve analyses were performed to confirm the specificity as well as the integrity of the PCR products by the presence of a single peak. Primers were designed from the online mouse library probes of Roche Diagnostics for the bone resorption markers, and the reference gene primers were designed by R. Olaso (Centre National de Génotypage, Evry, France). Primers sequences of all genes analyzed are provided in Supplemental Table 1. Standard curves were generated from assays made with serial dilutions of reference cDNA to calculate PCR efficiencies (efficiencies were considered as correct when lying in a range of 100% ± 15%, with r2 ≥ 0.996 according to the MIQE guidelines) (Supplemental Table 1). The sample Cq values were transformed into quantity values using the formula (1 + Efficiency)−Cq. Only means of triplicates with a variability coefficient of <10% were analyzed. Inter-plate variation was below 10%. Values were normalized to the geometric mean of the 5 Normalization Factors (NF) found to be the most stable in all the samples using the geNorm approach (Vandesompele et al., 2002). The 5 NFs used were TBP, HPRT, Aldolase, GAPDH and SDHA.

2.12. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± S.E.M. Statistical comparisons were made using Student's t-test, or ANOVA when required with p < 0.05 being considered significant. The statistical analyses were carried out using the Prism GraphPad 7 software.

3. Results

3.1. Knockout of syncytin-B decreases the number of multinucleated osteoclasts ex vivo

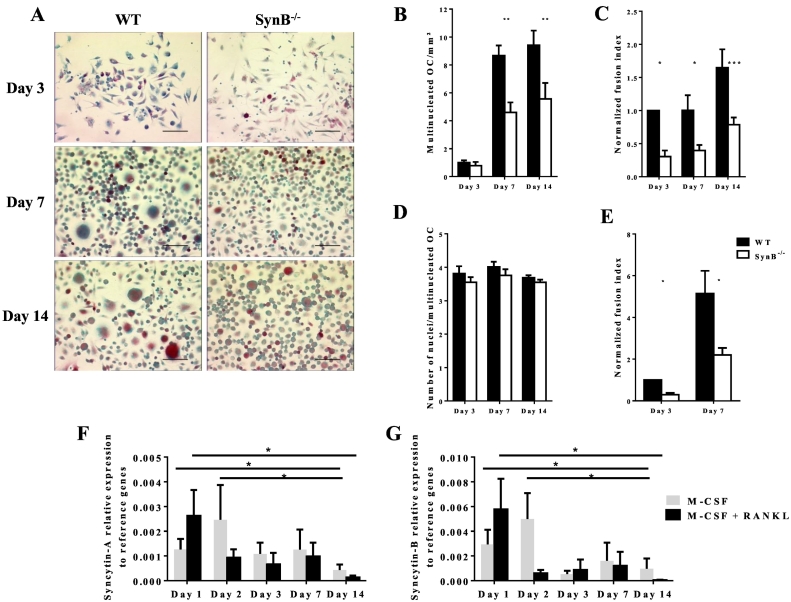

In order to analyze the impact of syncytin-B on osteoclastic fusion, splenocytes from 6 weeks old wild-type (WT) and syncytin-B KO (SynB−/−) mice were cultured in the presence of M-CSF and RANKL for up to 14 days. After 3, 7 and 14 days of culture, cells were fixed, stained for TRAP activity (Fig. 1A), and the number of mono-, bi- and multinucleated TRAP-positive OCs was counted. Interestingly, a few multinucleated OCs could already be observed as early as at day 3 and their number significantly increased from day 3 to day 7 in both the WT and SynB−/− cultures (Fig. 1B). At day 3, no statistical difference was observed between WT and SynB−/− multinucleated OCs. In contrast, the number of multinucleated OCs was significantly lower in the SynB−/− as compared to the WT cultures at day 7 (47%) and day 14 (41%) (p < 0.01) (Fig. 1B). Accordingly, the number of mononucleated TRAP positive cells in the SynB−/− cultures was significantly increased at day 3, 7 and 14 in comparison to the WT cultures (Supplemental Fig. 1A), while the number of binucleated TRAP positive cells was not significantly modified in the SynB−/− cultures (Supplemental Fig. 1B). Of note, the total number of TRAP positive cells was comparable in the WT and SynB−/− cultures (Supplemental Fig. 1C), indicating that inhibition of multinucleation is not caused by reduced precursor cell differentiation in SynB−/− cultures. Overall, the fusion efficiency of TRAP positive OCs, assessed by the fusion index (see Material and Methods) was found to be significantly decreased in the SynB−/− OC cultures at day 3 (70%), 7 (61%) and 14 (55%) in comparison to WT (Fig. 1C). We finally performed a detailed analysis of nuclei distribution in OCs that showed no reduction in the average number of nuclei per multinucleated OCs at day 3, 7 or 14 when comparing SynB−/− to WT cells (Fig. 1D). Of note, in cultures of female origin, the invalidation of syncytin-B decreases the number of multinucleated OCs and the fusion index as in male, although to a lesser extent and with a slightly different time course (Supplemental Table 2). Thus, it appears from splenocyte cultures, that syncytin-B deletion has a deleterious effect on OC fusion, which affects the initial steps of OC formation (before Day 3), without increasing the number of nuclei per OC. The formation of OCs by fusion of bone marrow precursors was also analyzed. Bone marrow CD11b-positive cells from WT and SynB−/− mice were cultured in the presence of RANKL and M-CSF for up to 7 days. Multinucleated OCs were also visible as early as on day 3 of culture and we observed the same effects as in the SynB−/− splenocyte cell culture described above, i.e. a reduction of the fusion index at days 3 (71%) and 7 (57%) in comparison to WT cultures (Fig. 1E). We then asked whether syncytin expression could be regulated in the course of OC multinucleation. We thus quantified by qPCR the level of syncytin-B and syncytin-A expression at days 1, 2, 3, 7 and 14 of WT cultures. The splenocyte cultures were carried out in the presence of M-CSF with or without RANKL, in order to evaluate the potential RANKL-dependence of syncytin-A and -B expression. We showed that neither syncytin-A (Fig. 1F) nor syncytin-B (Fig. 1G) expression is dependent on RANKL. We also showed that both syncytin-A and -B transcript levels are maximal in the first 2 days of culture (day 1 and 2 vs day 14 when cultured with M-CSF with or without RANKL, p = 0.05) and then decrease during cell culture (Fig. 1F and G), consistent with a role of SynB in the initial OC fusion events. Finally, syncytin-A and -B expressions were found to be independent from each other since knockout of syncytin-B did not modify the syncytin-A expression profile (Supplemental Fig. 2A) in the absence or presence of RANK-L (Supplemental Fig. 2B). As the SynB deficiency induced a decrease in fusion index, we analyzed the expression of two main actors of the fusion of both OCs and macrophages: DC-STAMP (Dendritic cell–specific transmembrane protein) and MFR (Macrophage Fusion Receptor). The expression of both DC-STAMP and MFR are not modified in the absence of SynB (Supplemental Fig. 3A,B), suggesting that they are not able to compensate the absence of SynB and that they may be responsible for the residual fusion observed.

Fig. 1.

Lack of syncytin-B leads to defect in osteoclast precursor cell fusion ex vivo.

A–D, F, G. Splenocytes from WT and SynB−/− male mice were differentiated into OCs for up to 14 days in the presence of M-CSF and RANKL. Data are shown as the means of 4 independent experiments involving 10 SynB−/− and 9 WT male mice. A. TRAP activity staining at 3, 7 and 14 days of culture of WT and SynB−/− cells. Multinucleated cells were more numerous in WT cell cultures (bar scale 50 μm). B. Multinucleated (>3 nuclei) TRAP positive cells were counted at 3, 7 and 14 days of culture. Significantly less multinucleated TRAP positive cells were observed in SynB−/− than in WT cultures at day 7 and 14. C. The fusion index was evaluated in both WT and SynB−/− OC cultures at day 3, 7 and 14. This fusion index, expressed relative to day 3 WT values arbitrarily set at 1, was significantly decreased in SynB−/− cell cultures at day 3, 7 and 14 in comparison to WT cell cultures. D. The number of nuclei in multinucleated TRAP positive cells was counted. No difference was observed between the WT and SynB−/− TRAP positive cells. E. OCs were also differentiated from bone marrow cells from WT and SynB−/−mice in the presence of M-CSF and RANKL for up to 7 days (three experiments including 6 individuals). The fusion index was evaluated and showed significant decrease for SynB−/− cells in comparison to WT cells. F, G. RT-qPCR time course analysis of syncytin-A (F) and syncytin-B (G) expression during differentiation of WT splenocytes in the presence of M-CSF (grey bars), or M-CSF and RANKL (black bars). Higher levels of syncytin-A and syncytin-B transcripts were observed at days 1 and 2 relative to day 14 of culture in the presence of M-CSF plus RANKL. Neither syncytin-A nor syncytin-B expression is regulated by RANKL. Values were normalized to the geometric mean of 5 normalization factors (see Material and Methods). Black bars represent WT mice; white bars represent SynB−/− mice and results are shown as means ± S.E.M (*p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01).

3.2. Knockout of syncytin-B does not impact osteoclastic function

In order to evaluate the impact of syncytin-B deficiency on OC function, we performed a pit resorption assay on dentin slices (Fig. 2A). Splenocyte cultures from WT or SynB−/− mice were carried out as described above. TRAP staining of the cultured cells did not reveal any difference in the total number of TRAP positive cells (Fig. 2B), as what was observed in the previously described culture (Supplemental Fig. 1). In addition, we could not find any significant difference in the resorption pit area between the WT and SynB−/− assays (Fig. 2C). We also measured the maximal depth of the resorption pit. Ten random pits from each culture were analyzed by confocal microscopy (Fig. 2D). The maximal pit depth was unchanged in SynB−/− compared to WT OC cultures (Fig. 2E). These results are in accordance with the quantification by RT-qPCR of the transcripts of OC gene markers (TRAP, NFATc1, Cathepsin K and RANK) that remain similar in WT and SynB−/− OC cultures (Fig. 2F), suggesting that there is no difference in terms of differentiation and activity between WT and SynB−/− OC. In conclusion, syncytin-B plays a role in the early steps of OC fusion but its inactivation does not impair OC activity. Taken together, these results also suggest that the activity and function of OC cells is not solely dependent on OC multinucleation.

Fig. 2.

Lack of syncytin-B does not affect bone resorption nor expression of osteoclastic marker genes.

OCs from WT and SynB−/− mice were differentiated on dentin slices for 14 days in the presence of M-CSF and RANKL. A. Representative images of (upper) resorption pits stained with toluidine blue and (lower) OCs stained for TRAP activity (bar scale 500 μm). B. TRAP positive cells were counted. C. the mean resorption area was measured from WT and SynB−/− cultures. No significant difference was observed between WT and SynB−/−. D. Pits seen under phase contrast (upper panels) and color-coded pit depth (lower panels) imaged by confocal microscopy from WT and SynB−/− cultures. Pit depth value increases progressively from blue to red according to the color scale of the bottom lines in the lower panels (scale bar: 50 μm). E. Maximal pit depth value was assessed. No significant difference was observed between WT and SynB−/−. F. Expression time course of osteoclastic marker genes (TRAP, NFATc1, Cathepsin K, RANK) was evaluated during OC differentiation at day 1, 2, 3, 7 and 14. No significant difference between WT and SynB−/−cells was observed. Black bars refer to WT mice; white bars refer to SynB−/− mice and results are shown as means ± S.E.M.

3.3. Syncytin-A and -B are expressed as early as at E16.5 in the bones

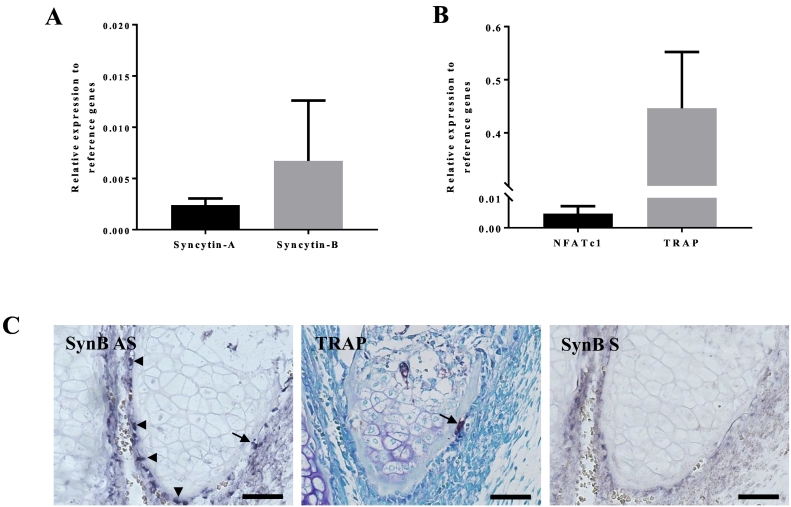

The first sign of OC activity during embryonic development was reported to be detectable as early as at E16.5 in the forming long bones (Dodds et al., 1998). In order to validate the results described above suggesting the involvement of syncytin-B in the early steps of OC differentiation, we carried out a qPCR analysis on RNA extracted from E16.5 femurs, and showed that syncytin-B -as well as syncytin-A- (Fig. 3A) are expressed at this developmental stage. Of note, OC gene markers TRAP and NFATc1 were also expressed, as expected (Fig. 3B). To confirm and localize syncytin-B expression in bone at E16.5, we performed in situ hybridization experiments on paraffin-embedded E16.5 femur sections (Fig. 3C). Specific digoxigenin-labeled antisense probes were synthetized for detection of syncytin-B and the corresponding sense probes were used as negative controls. As shown in Fig. 3C, an intense labeling was only observed with the antisense probe, and was localized in the periosteum, in both mono and multinucleated cells. TRAP staining on serial sections revealed a multinucleated TRAP-positive cell in the periosteum (Fig. 3C) also labeled with the SynB antisense probe. This observation supports the notion that the signal observed with the SynB antisense probe could correspond to macrophages/precursors of OC cells or even directly to OC cells. Conclusively, the syncytin-B expression pattern obtained by qPCR or ISH is consistent with a role of syncytin-B in triggering fusion of the OC cells.

Fig. 3.

In vivo expression of syncytin-B in E16.5 femurs.

A. Analysis of syncytin-A and -B expression in E16.5 femurs by RT-qPCR. Values were normalized to the geometric mean of 5 normalization factors (see Material and Methods) (n = 4). B. Analysis of NFATc1 and TRAP (OC marker genes) expression in E 16.5 femurs by RT-qPCR. Values were normalized to the geometric mean of 5 normalization factors (see Material and Methods) (n = 4). Black bars represent WT mice; white bars represent SynB−/− mice and results are shown as means ± S.E.M. C. In situ hybridization to localize syncytin-B transcripts and TRAP staining was carried out on serial paraffin sections of E 16.5 hind limbs. A stronger syncytin-B signal was observed mainly in the periosteum of the E16.5 femurs (SynB AS) in cells that seem to be both mono- (arrow heads) and multi-nucleated (arrow), whereas a very weak signal was observed when the control probe was used (SynB S). The syncytin-B signal could coincide with the TRAP signal observed in the periosteum of the adjacent section (arrow) (scale bare: 100 μm).

3.4. Knockout of syncytin-B does not alter bone resorption in vivo

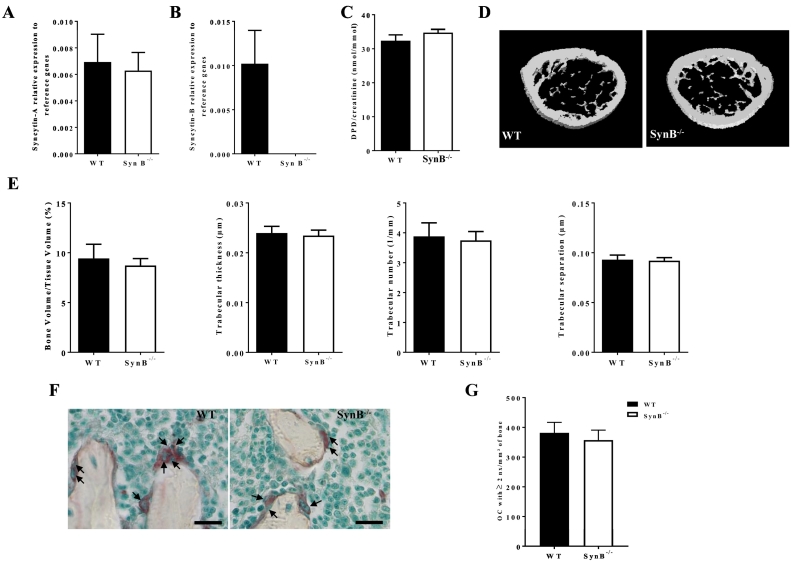

We first carried out qPCR analyses on whole femurs without bone marrow of WT and SynB−/− in order to assess the level of expression of both syncytin-A and -B in adult mice. In WT animals, we could successfully detect transcripts of both syncytins (Fig. 4A and B), although they are present at a much lower level compared to those found in the placenta (Supplemental Fig. 4A and B). Interestingly, although it did not reach significance (probably because of low sample size), expression of both syncytins is clearly higher in bones than in muscles (Supplemental Fig. 4A and B), a tissue in which Syncytins have been shown to contribute to myoblast fusion and muscle formation (Redelsperger et al., 2016). As expected, no expression of syncytin-B is detected in the femur of SynB−/− mice (Fig. 4B). Finally, as demonstrated ex vivo, we showed that syncytin-A expression was independent of syncytin-B, since syncytin-B deficiency does not impact on syncytin-A expression (Fig. 4A). Taking advantage of the available SynB−/− mouse model, we analyzed the implication of this protein in bone resorption. The bone phenotype in adult mice was analyzed at different ages, namely at 6, 12 and 24 weeks. We analyzed bone density by DEXA, which showed no significant difference between WT and SynB−/− mice aged 6, 12 and 24 weeks (Supplemental Table 3). To directly assess the activity of OCs in vivo, we measured the urinary deoxypyridinoline (DPD)/creatinine ratio that reflects bone resorption. No significant difference was observed between WT and SynB−/− mice (Fig. 4C). This observation was in accordance with the quantification by RT-qPCR of osteoclastic markers (TRAP, NFATc1, Cathepsin K and RANK) that remained equivalent in the SynB−/− femurs in comparison to WT (Supplemental Fig. 5A–D). These results were in agreement with the previous results obtained ex vivo and confirmed that syncytin-B deficiency does not impair OC differentiation or activity. We finally carried out a μCT analysis of the trabecular bone microarchitecture at 6 (Fig. 4 D and E) and 24 weeks (Supplemental Table 4), which again disclosed no significant difference between WT and SynB−/− mice when calculating the Bone Volume over Tissue Volume (BV/TV), Trabecular Thickness (Tb.Th), Trabecular Number (Tb.N) and Trabecular Separation (TB.Sp). Taken altogether, these results show that syncytin-B deficiency does not impair bone resorption. Of note, the same phenotype was observed when comparing WT vs SynB−/− male or female animals (Supplemental Table 5, 6). We finally analyzed the OC number and multinucleation on TRAP-stained undecalcified sections of femurs from 6 weeks old mice (Figs. 4F and G). We counted the OC number (Supplemental Fig. 6A), the number of multinucleated OC (2 and more nuclei) (Fig. 4G), and finally the number of nuclei/per multinucleated OC per mm2 of bone (Supplemental Fig. 6B). For all these parameters, we did not find any significant difference between WT and SynB−/− mice.

Fig. 4.

Lack of syncytin-B does not impact on bone phenotype at 6 weeks of age.

RT-qPCR analysis of syncytin-A (A) and syncytin-B (B) transcript levels in WT and SynB−/−male mice femurs at 6 weeks of age. Values were normalized to the geometric mean of 5 normalization factors (see Material and Methods). Syncytin-A expression displays no difference between the 2 genotypes, whereas as expected syncytin-B expression was only detected in WT mice. C. The amount of urinary deoxypyridinoline (DPD) crosslinks normalized by the amount of creatinine presented no difference between WT and SynB−/− mice. D. Representative images of WT and Syn B−/− femurs analyzed by μCT. E. Trabecular microarchitecture was assessed by μCT on femurs from 6 weeks old WT and SynB−/− mice. No difference was observed when measuring the bone volume/tissue volume, or the trabecular thickness, number and separation. F. Representative pictures of TRAP positive OCs (arrows) on undecalcified femur sections from WT and SynB−/− mice (Scale bar 50 μm). G. TRAP-positive multinucleated (2 nuclei and more) OCs were counted on undecalcified femur sections from WT and SynB−/− mice and showed no difference. Black bars represent WT male mice, n = 9; white bars represent SynB−/− male mice, n = 10. Results are shown as means ± S.E.M.

3.5. Knockout of syncytin-B decreases the number of multinucleated giant cells ex vivo, but not in vivo

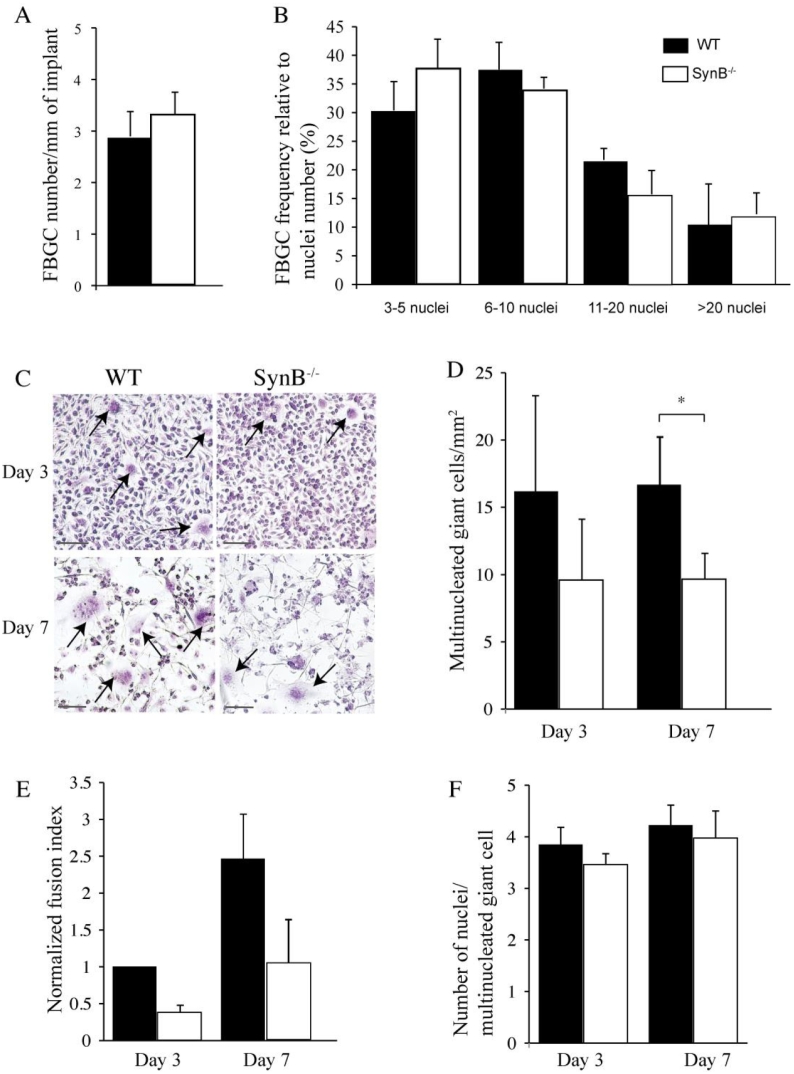

Finally, we considered the possibility that syncytin-B might be required to form other monocyte-derived multinucleated giant cells, such as FBGCs. FBGCs are induced by fusion of monocyte/macrophage lineage cells in response to foreign bodies at the site of implantation (Sheikh et al., 2015). Filters were implanted s.c. in WT and SynB−/− male and female littermates for 4 weeks, and then processed for histochemical analysis by HES staining (see Material and Methods) (Supplemental Fig. 7A). The total number of nuclei in mono-, bi- or multinucleated cells (>3-nuclei, considered as FBGCs) that adhere to the implants were counted. As shown in Fig. 5A, the total number of FBGCs per mm of implant does not vary significantly between WT and SynB−/− animals. Moreover, a detailed analysis of the size distribution of FBGCs showed no variation in the number of nuclei per multinucleated FBGC when comparing WT to SynB−/− animals (Fig. 5B). Of note, no difference was found when comparing either male or female animals (Supplemental Fig. 7B, C).

Fig. 5.

Syncytin-B deficiency results in reduced giant cell formation ex vivo but not in vivo.

A–B Millipore filters were implanted subcutaneously into WT (n = 4) and SynB−/− (n = 5) male mice for 4 weeks. A. Quantification of the number of multinucleated FBGCs per mm of implant perimeter. B. Frequency of FBGCs according to their nuclei number. Shown are means ± SEM. No difference was observed between the two genotypes. C–F. M-CSF-dependent bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDM) were cultured in the presence of GM-CSF and IL-4 for 3 or 7 days. C. May Gruwald and Giemsa staining of BMDM at 3 and 7 days of culture. Multinuclated giant cells (arrows) are more numerous in the WT cell cultures (scale bar 100 μm). D. Quantification of the number of multinucleated giant cells per mm2. Significantly less multinucleated giant cells were observed in SynB−/− than in WT cultures at day 7. E. Fusion index of giant cells from SynB−/− and WT mice counted at day 3 and 7, with day 3 WT value arbitrarily set at 1. The fusion index was significantly different between WT and SynB−/− cell cultures at both day 3 and 7. F. Quantification of the number of nuclei per giant cell. No significant difference was observed between WT and SynB−/− mice. Shown are means ± SEM of at least eight measurements combined from 5 independent experiments. *P < 0.05 (t-test, two-tailed); Black bars represent WT mice; white bars SynB−/− mice.

We then compared the capacity of bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) obtained from WT and SynB−/− mice to differentiate into giant cells in vitro. BMDMs obtained from 6 weeks old male and female WT and SynB−/− mice were cultured in the presence of M-CSF for up to 7 days. The percentage of CD11b + macrophages, analyzed by flow cytometry showed no difference between WT and SynB−/− animals (>90%; Supplemental Fig. 7D), indicating that the absence of syncytin-B does not impair macrophage maturation. M-CSF-dependent BMDMs were then cultured in the presence of IL-4 and GM-CSF for up to 7 days and stained with May-Grunwald and Giemsa (see Material and Methods). Multinucleated (>3-nuclei) giant cells were observed as early as on day 3 (Fig. 5C, D). At this stage, a decrease in giant cell number was observed in SynB−/− macrophages, though it did not reach statistical significance. At day 7, the number of multinucleated giant cells was significantly decreased (42%) in the SynB−/− as compared to the WT cultures (p < 0.05) (Fig. 5C, D). Quantification of nuclei for mono-, bi-, and multinucleate cells further showed that the rate of macrophage fusion (fusion index) was reduced by >2.7 fold in the SynB−/− cultured cells at day 3 (63%) and 7 (60%) in comparison to the WT ones (Fig. 5E). Interestingly, a detailed analysis of the number of nuclei per multinucleated giant cells showed no variation when comparing WT to SynB−/− animals (Fig. 5F). Collectively, these data indicate that syncytin-B deletion affects the macrophage fusion process, without increasing the size of giant cells. This is in agreement with the data obtained from spleen and bone marrow OC cell cultures, and argues for a general role of syncytin-B in the cell-cell fusion processes of the monocyte/macrophage lineage cells. However, as observed upon in vivo examination of OC formation, syncytin-B inactivation does not impair FBGC formation in vivo.

4. Discussion

Multinucleated OCs and giant cells are formed by fusion of precursor cells that belong to the monocyte–macrophage lineage. Cell fusion is a complex and highly regulated process involving different factors in addition to the cell membrane itself (for reviews, see (Chen et al., 2007; Miyamoto, 2011)). Different sequential events are responsible for the fusion of OC precursors (Oursler, 2010). Indeed, for an efficient cell-cell fusion, the fusion competent cells need to get into close contact and recognize themselves as fusion partners. Then, the plasma membranes need to physically fuse. Fusion of competent mononuclear TRAP+ cell requires the presence of two essential factors, i.e. M-CSF and RANKL, and involves the NFATc1 signaling pathway as well as several proteins involved in the cell-cell recognition, migration and attachment processes, such as CD44 (Cui et al., 2006) or E cadherin (Oursler, 2010; Mbalaviele et al., 1995; Miyamoto, 2013). Interestingly, Recently, Verma et al. showed that the fusion of human OC depends on a multiprotein fusion machinery involving DC-STAMP, extracellular phosphatidylserine and annexins, their binding proteins, as well as the human Syncytin-1 protein, which displays characteristic of a true fusogen (see below) (Verma et al., 2017). In contrast to the clearly defined stimuli involved in osteoclastogenesis, the fusion of macrophages into FBGCs is induced by a variety of different cytokines and endogenous as well as exogenous stimuli (IL-4 and IL-13, GM-CSF, IL-17A, IFNγ and lectins), in a manner probably dependent on the pathological conditions. Yet, partly common mechanisms seem to be shared by the two processes, such as the central role played by ADAM12, DC- and OC-STAMP (Miyamoto, 2013). Syncytin genes are captured retroviral envelope proteins that can mediate membrane fusion and are involved in the formation of a multinucleated syncytial layer, the syncytiotrophoblast, during placenta formation (Lavialle et al., 2013). It has already been reported that in ex vivo experiments human syncytin-1 is involved in human osteoclastic fusion (Søe et al., 2011) and more precisely in the fusion between two multinucleated OCs (Møller et al., 2017). We here took advantage of the knockout mouse models to tentatively further decipher the involvement of syncytins in vivo. As previously stated, there are two syncytin genes in the mouse, syncytin-A and -B. While the syncytin-A knockout is lethal in utero at E13.5 due to placental failure (Dupressoir et al., 2009), the syncytin-B knockout mouse line although showing mild intrauterine growth retardation, is viable and fertile (Dupressoir et al., 2011). We therefore focused our study on this mouse model to address the role of syncytin-B in OC and giant cell precursor fusion.

Here, we were able to detect by qRT-PCR syncytin-A and -B mRNAs in cultures of differentiating OCs derived from splenocytes, as well as in femurs at E16.5 and at 6 weeks of age. Although, as expected, syncytins display much lower levels of expression in the femurs as compared to the placenta, they are at least as expressed in femurs as in muscles, a tissue in which syncytins were shown to play a role in myoblast fusion (Redelsperger et al., 2016), suggesting that syncytin expression in differentiating OC/femurs might be of functional relevance. In differentiating OCs, we observed that both syncytins are more highly expressed in the early days than at the end of the cultures, suggesting that they could function in the early stages of OC differentiation. We found that expression of syncytin-A and -B is not induced by RANKL treatment, in contrast to other proteins involved in the OC precursor fusion process (e.g. OC-STAMP (Yang et al., 2008), DC-STAMP, NFATc1 (Yagi et al., 2005)). Interestingly, a lack of induction - and even a decrease - in expression by RANKL was also observed for the human syncytin-1 in an OC differentiation model (Søe et al., 2011), suggesting that syncytins in general would belong to RANKL-independent pathway(s), as already reported for other genes regulating fusion (reviewed in (Xing et al., 2012)). Finally, we observed that the absence of syncytin-B is not compensated by an increase in syncytin-A expression in the OC cultures or in the whole femur of SynB−/− mice. This could suggest that although both syncytin-A and -B are expressed in OCs, they do not share the same role and are not redundant. A distinct role for syncytin-A and -B in the placenta has previously been demonstrated, as revealed by their separate expression in two distinct syncytiotrophoblast layers and by the different placental phenotypes observed between the syncytin-A and syncytin-B KO mice (Dupressoir et al., 2009; Dupressoir et al., 2011). Yet, their role is likely to be complementary as suggested by the aggravated placental phenotype observed in the syncytin-A and -B double KO mice as compared with the syncytin-A single KO mice (Dupressoir et al., 2011).

In this study, we demonstrated that cell cultures established from SynB−/− and WT mice and derived from two independent sources, i.e. bone marrow and spleen precursors, displayed a significant decrease in fusion index at 3, 7 and 14 days of culture (up to 83%) in the absence of syncytin-B. The number of multinucleated OCs was decreased and, as expected, that of mononucleated TRAP+ cells was increased. Interestingly, this decrease did not affect the number of nuclei per multinucleated OCs. This could indicate that syncytin-B is relatively more involved in fusion at the initial stage of OC fusion -involving mononucleated precursor cells- rather than in the later fusion events, involving multinucleated OCs. This hypothesis is also supported by other observations: i) syncytin-B expression is maximal in the first 2 days of OC cell differentiation, ii) syncytin-B expression is detected in mononucleated cells rather than in multinucleated OCs at E16.5, as assessed by ISH experiments, and iii) the fusion index was reduced in OC precursor cells derived from SynB−/− mice as early as after 3 days of culture. Yet, further investigations are needed to cast more light on this hypothesis. In any case, Syncytin-B is clearly not the essential protein responsible for the fusion process generating OCs and giant cells, as fusion is not abolished in SynB−/− cultures. In order to gain insight in the residual fusion process observed in the case of the SynB deficiency, the expression of the so called “master fusogen” for OCs (Oursler, 2010; Yagi et al., 2005) and MFR (Vignery, 2005) were analyzed without revealing any difference. They might not be able to compensate for the SynB deficiency but might be responsible for the ability of the SynB deficient OC precursor to still fuse. It might be of interest to analyze without a priori -by RNAseq- the numerous molecules (see for example Ref (Oursler, 2010)) involved in the fusion process to identify the one(s) that might be modified and compensate for the absence of SynB.

Interestingly, in bone marrow cell cultures of SynB−/− mice stimulated with IL4 and GM-CSF and analyzed at days 3 and 7, we also obtained evidence for a reduction of >2.7 fold in the efficiency of the fusion process that leads to the formation of giant cells from precursors of the same monocyte-macrophage lineage. As observed for the OCs, the number of nuclei per giant cell was not modified. All these data argue for a general role of syncytin-B in the fusion processes involving the monocyte/macrophage lineage cells. The fact that syncytin-B depletion affects in a similar manner the fusion processes generating OCs and giant cells strengthens the notion that although the triggers may vary, both processes depend on a common set of macrophage-expressed molecules, as already suggested (Miyamoto, 2013).

Previously, Søe and collaborators (Søe et al., 2011), studying human syncytin-1 in cultures of differentiating OCs, reported that a syncytin-1 inhibitory peptide reduced the number of nuclei per OC by 30%. This reduction was due to reduced formation of OCs with >4 nuclei, with even an overall increase in the number of multinucleated OCs. Time laps analysis of the fusion events by Moller and colleagues (Møller et al., 2017), further confirmed that syncytin-1 promotes fusion of multinucleated OCs between themselves, while reducing fusion of mononucleated precursor cells. The fact that syncytin-B and syncytin-1 would be implicated at different stages of OC formation, i.e. early and late fusion events, respectively, could be explained by differences in the time course of their expression profile during OC differentiation, or in the nature and/or expression profile of their specific receptor - still to be identified for Syncytin-B.

Syncytin-B is an early actor in the fusion process ex vivo; yet it is clearly not the essential protein responsible for the fusion process generating OCs and giant cells, as fusion is not abolished in SynB−/− cultures. This was also observed for human syncytin-1 (Søe et al., 2011). It is likely that OC and giant cell formation depends on more than one mechanism of fusion as already suggested (Oursler, 2010), and as described for the fusion of myoblasts for which it recently turned out that at least 2 components are required (Quinn et al., 2017). These other fusion processes might compensate for the loss of syncytin-B in KO mice, therefore accounting for the absence of a bone phenotype and of a reduction in giant cell number that we observed. A similar -and even more drastic- situation was observed for the OC-STAMP KO mice where OCs display profound defects in fusion both in vitro and in vivo, and even in resorption activity in vitro, but mice paradoxically, lacked a skeletal phenotype (Miyamoto et al., 2012). Note that syncytin-B, although displaying all the characteristics of a true fusogen, could also be one of the factors necessary for cell-cell recognition, contact and attachment, therefore playing a more crucial role under ex vivo conditions (in the absence of other actors of such processes, e.g. integrin, extracellular matrix, etc.) than in vivo.

Significantly fewer multinucleated OCs are detected in the SynB−/− cell cultures; yet the resorption assays performed with these cells on dentin revealed no significant difference in the extent of bone resorption. Assuming that cells cultured on plastic and cells cultured on dentin behave the same way, these results suggest that SynB−/− impaired fusion of OCs has no impact on their ex vivo resorbing activity. In addition, SynB−/− OCs showed no delay in their differentiation, as evidenced by the absence of alterations in the expression of various osteoclastic marker genes in SynB−/− compared to WT OCs.. This suggests that Syncytin-B is involved in OC precursor fusion but not in their differentiation, as previously demonstrated for OC-STAMP (Miyamoto et al., 2012). These ex vivo data could shed some light on our in vivo results showing no bone phenotype in the SynB−/− mice, at any level or age tested. Here we showed that knockout of syncytin-B impacts on OC precursor cell fusion ex vivo, yet without interfering with bone physiology in vivo. The fusion of macrophages into giant cells is similarly altered in ex vivo cell cultures, but not in vivo. These data support a role of syncytin-B critical to OC and giant cell precursor fusion ex vivo, but not essential to OC and FBGC formation in vivo, at least under the conditions tested.

The receptors of Syncytin-1 and Syncytin-2 have been identified, i.e. the ASCT-2 (Blond et al., 2000) and MFSD2a (Esnault et al., 2008) transporters, respectively, as well as that of Syncytin-A, Ly6e (Bacquin et al., 2017), but the receptor of Syncytin-B remains to be discovered. Its characterization could highlight the precise role of syncytin-B in the OC and FBGC precursor cell fusion processes. It might also be of interest to challenge SynB−/− mice by ovariectomy or in a bone fracture model for example, to analyze the effect of the knockout of syncytin-B on bone loss and healing normally following these conditions, as it was previously shown that syncytin-B contributes to the repair of muscle injury (Redelsperger et al., 2016). Our study demonstrated expression of syncytin-A during OC differentiation ex vivo, suggesting that syncytin-A could also be of importance for OC formation. Yet, we could not further study its involvement in OC precursor fusion in vivo because the syncytin-A KO model is embryonic lethal (Dupressoir et al., 2009). In the future, it might be of interest to study syncytin-A contribution to OC precursor fusion and bone phenotype, by generating a conditional KO mouse in which syncytin-A is specifically deleted in cells from the monocyte/macrophage lineage. Murine syncytins have been captured primarily as placental genes (Lavialle et al., 2013). Their expression is now also described in muscle (Redelsperger et al., 2016) and here in OC and FBGC precursors. This might suggest a “collateral” effect of the capture of such genes, thanks to their fusogenic property, that might be an asset contributing to osteoclastogenesis. Accordingly, it could be of interest to compare the regulatory processes and transcription factors shared by fusogenic cells involved in the development of placenta, muscle and OC/FBGC in order to identify new common fusion pathways.

5. Conclusion

In this study, we showed that the knockout of syncytin-B, a highly fusogenic protein, impacts on OC generation by fusion ex vivo, in accordance with the work of Søe et al., but without interfering with bone physiology in vivo. The fusion of macrophages into giant cells is similarly altered in ex vivo cell cultures, but not in vivo. These data support a role of syncytin-B critical to OC and giant cell precursor fusion, but not essential for OC and FBGC formation in vivo, at least under the conditions tested. Interestingly, these results demonstrated that Syncytin-B deficiency did not impair OC function ex vivo and in vivo, although it did impair OC fusion ex vivo. In conclusion, syncytin-B might have a much more important role in the placenta than in OCs (as suggested by its level of expression in placenta in comparison to bone – Supplemental Fig. 5); it is however involved in fusion processes driving the formation of OCs and giant cells. Syncytin-B presents characteristics consistent with the actual process of plasma membrane merging, yet it could also be part of the growing group of proteins involved in the recognition and/or attachment between cells destined to fuse, such as for instance MFR/SIRPα, CD44 or CD9 (Chen et al., 2007; Cui et al., 2006; Lundberg et al., 2007). Identification and characterization of the Syncytin-B receptor as well as further analysis of the syncytin-A KO mice should be highly informative in the future.

Author contributions

AEC, FR, TH, MC de V and AD designed research; AEC, FR, YCA, CV, CM, XD and AD performed research; AEC, FR, YCA, CV, CM, XD, TH, MC de V and AD analyzed and interpretated the data; and AEC, FR, AD, TH and MC de V wrote the final version of paper that was approved by all the authors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Pascale Chanterenne and Hugo Becque (BIOSCAR) and Pascal Cavoit (IGR) for maintaining the mouse colony; Mélanie Polrot for filter implantation and Olivia Bawa for contribution to the histological analyses. We thank Agnès Ostertag for the excellence of her technical assistance and our gratitude goes to Robert Olaso for designing the NF primers. We thank Christian Lavialle for critical reading of the manuscript.

Fundings

This work was supported by the INSERM and CNRS, and by grants from the Agence Nationale de la Recherche ((ANR)-07-e-RARE-010-01 OSTEOPETR to MC de V and RETROPLACENTA to TH), the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (to MC de V) and the Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer (to TH).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bonr.2019.100214.

Contributor Information

Amélie E. Coudert, Email: amelie.coudert@inserm.fr.

Anne Dupressoir, Email: anne.dupressoir@gustaveroussy.fr.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- Bacquin A., Bireau C., Tanguy M., Romanet C., Vernochet C., Dupressoir A., Heidmann T. A cell fusion-based screening method identifies glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein Ly6e as the receptor for mouse endogenous retroviral envelope syncytin-a. J. Virol. 2017;91 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00832-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biosse Duplan M., Zalli D., Stephens S., Zenger S., Neff L., Oelkers J.M., Lai F.P.L., Horne W., Rottner K., Baron R. Microtubule dynamic instability controls podosome patterning in osteoclasts through EB1, cortactin, and Src. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2014;34:16–29. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00578-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaise S., de Parseval N., Bénit L., Heidmann T. Genomewide screening for fusogenic human endogenous retrovirus envelopes identifies syncytin 2, a gene conserved on primate evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:13013–13018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2132646100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blond J.L., Lavillette D., Cheynet V., Bouton O., Oriol G., Chapel-Fernandes S., Mandrand B., Mallet F., Cosset F.L. An envelope glycoprotein of the human endogenous retrovirus HERV-W is expressed in the human placenta and fuses cells expressing the type D mammalian retrovirus receptor. J. Virol. 2000;74:3321–3329. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.7.3321-3329.2000. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10708449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazier H., Stephens S., Ory S., Fort P., Morrison N., Blangy A. Expression profile of RhoGTPases and RhoGEFs during RANKL-stimulated osteoclastogenesis: identification of essential genes in osteoclasts. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2006;21:1387–1398. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustin S.A., Benes V., Garson J.A., Hellemans J., Huggett J., Kubista M., Mueller R., Nolan T., Pfaffl M.W., Shipley G.L., Vandesompele J., Wittwer C.T. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin. Chem. 2009;55:611–622. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabbi-Achengli Y., Coudert A.E., Callebert J., Geoffroy V., Côté F., Collet C., de Vernejoul M.-C. Decreased osteoclastogenesis in serotonin-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:2567–2572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117792109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen E.H., Grote E., Mohler W., Vignery A. Cell-cell fusion. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:2181–2193. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui W., Ke J.Z., Zhang Q., Ke H.-Z., Chalouni C., Vignery A. The intracellular domain of CD44 promotes the fusion of macrophages. Blood. 2006;107:796–805. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempster D.W., Compston J.E., Drezner M.K., Glorieux F.H., Kanis J.A., Malluche H., Meunier P.J., Ott S.M., Recker R.R., Parfitt A.M. Standardized nomenclature, symbols, and units for bone histomorphometry: a 2012 update of the report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2013;28:2–17. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodds R.A., Connor J.R., Drake F., Feild J., Gowen M. Cathepsin K mRNA detection is restricted to osteoclasts during fetal mouse development. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1998;13:673–682. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.4.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupressoir A., Marceau G., Vernochet C., Benit L., Kanellopoulos C., Sapin V., Heidmann T. Syncytin-A and syncytin-B, two fusogenic placenta-specific murine envelope genes of retroviral origin conserved in Muridae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005;102:725–730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406509102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupressoir A., Vernochet C., Bawa O., Harper F., Pierron G., Opolon P., Heidmann T. Syncytin-A knockout mice demonstrate the critical role in placentation of a fusogenic, endogenous retrovirus-derived, envelope gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:12127–12132. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902925106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupressoir A., Vernochet C., Harper F., Guégan J., Dessen P., Pierron G., Heidmann T. A pair of co-opted retroviral envelope syncytin genes is required for formation of the two-layered murine placental syncytiotrophoblast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:E1164–E1173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112304108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esnault C., Priet S., Ribet D., Vernochet C., Bruls T., Lavialle C., Weissenbach J., Heidmann T. A placenta-specific receptor for the fusogenic, endogenous retrovirus-derived, human syncytin-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:17532–17537. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807413105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrtwich L., Nanda I., Diefenbach A., Henneke P., Triantafyllopoulou A. DNA damage signaling instructs polyploid macrophage fate in granulomas. Cell. 2016;167:1264–1280. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavialle C., Cornelis G., Dupressoir A., Esnault C., Heidmann O., Vernochet C., Heidmann T. Paleovirology of “syncytins”, retroviral env genes exapted for a role in placentation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2013;368 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg P., Koskinen C., Baldock P.A., Löthgren H., Stenberg A., Lerner U.H., Oldenborg P.-A. Osteoclast formation is strongly reduced both in vivo and in vitro in the absence of CD47/SIRPalpha-interaction. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;352:444–448. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbalaviele G., Chen H., Boyce B.F., Mundy G.R., Yoneda T. The role of cadherin in the generation of multinucleated osteoclasts from mononuclear precursors in murine marrow. J. Clin. Invest. 1995;95:2757–2765. doi: 10.1172/JCI117979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi S., Lee X., Li X., Veldman G.M., Finnerty H., Racie L., LaVallie E., Tang X.-Y., Edouard P., Howes S., Keith J.C., McCoy J.M. Syncytin is a captive retroviral envelope protein involved in human placental morphogenesis. Nature. 2000;403:785–789. doi: 10.1038/35001608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto H., Suzuki T., Miyauchi Y., Iwasaki R., Kobayashi T., Sato Y., Miyamoto K., Hoshi H., Hashimoto K., Yoshida S., Hao W., Mori T., Kanagawa H., Katsuyama E., Fujie A., Morioka H., Matsumoto M., Chiba K., Takeya M., Toyama Y., Miyamoto T. Osteoclast stimulatory transmembrane protein and dendritic cell–specific transmembrane protein cooperatively modulate cell–cell fusion to form osteoclasts and foreign body giant cells. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2012;27:1289–1297. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto T. Regulators of osteoclast differentiation and cell-cell fusion. Keio J. Med. 2011;60:101–105. doi: 10.2302/kjm.60.101. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22200633 (accessed November 20, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto T. STATs and macrophage fusion. JAK-STAT. 2013;2 doi: 10.4161/jkst.24777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møller A.M.J., Delaissé J.-M., Søe K. Osteoclast fusion: time-lapse reveals involvement of CD47 and syncytin-1 at different stages of nuclearity. J. Cell. Physiol. 2017;232:1396–1403. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oursler M.J. Recent advances in understanding the mechanisms of osteoclast precursor fusion. J. Cell. Biochem. 2010;110:1058–1062. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parfitt A.M., Drezner M.K., Glorieux F.H., Kanis J.A., Malluche H., Meunier P.J., Ott S.M., Recker R.R. Bone histomorphometry: standardization of nomenclature, symbols, and units. Report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1987;2:595–610. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650020617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn M.E., Goh Q., Kurosaka M., Gamage D.G., Petrany M.J., Prasad V., Millay D.P. Myomerger induces fusion of non-fusogenic cells and is required for skeletal muscle development. Nat. Commun. 2017;8 doi: 10.1038/ncomms15665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redelsperger F., Raddi N., Bacquin A., Vernochet C., Mariot V., Gache V., Blanchard-Gutton N., Charrin S., Tiret L., Dumonceaux J., Dupressoir A., Heidmann T. Genetic evidence that captured retroviral envelope syncytins contribute to myoblast fusion and muscle sexual dimorphism in mice. PLoS Genet. 2016;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh Z., Brooks P., Barzilay O., Fine N., Glogauer M. Macrophages, foreign body giant cells and their response to implantable biomaterials. Materials (Basel) 2015;8:5671–5701. doi: 10.3390/ma8095269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinn-Thomas J.H., Mohler W.A. New insights into the mechanisms and roles of cell–cell fusion. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2011:149–209. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-386039-2.00005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Søe K., Andersen T.L., Hobolt-Pedersen A.-S., Bjerregaard B., Larsson L.-I., Delaissé J.-M. Involvement of human endogenous retroviral syncytin-1 in human osteoclast fusion. Bone. 2011;48:837–846. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Søe K., Hobolt-Pedersen A.-S., Delaisse J.-M. The elementary fusion modalities of osteoclasts. Bone. 2015;73:181–189. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoye J.P. Studies of endogenous retroviruses reveal a continuing evolutionary saga. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012;10:395–406. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandesompele J., De Preter K., Pattyn F., Poppe B., Van Roy N., De Paepe A., Speleman F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002;3 doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12184808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma S.K., Leikina E., Melikov K., Gebert C., Kram V., Young M.F., Uygur B., Chernomordik L.V., Imprinting G., Kennedy E., Nichd S. Craniofacial, cell-surface phosphatidylserine regulates osteoclast precursor fusion from the sections on. Membr. Biol. 2017 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.809681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernochet C., Redelsperger F., Harper F., Souquere S., Catzeflis F., Pierron G., Nevo E., Heidmann T., Dupressoir A. The captured retroviral envelope syncytin-A and syncytin-B genes are conserved in the Spalacidae together with hemotrichorial placentation. Biol. Reprod. 2014;91:148. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.114.124818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignery A. vol. 202. 2005. Macrophage Fusion: The Making of Osteoclasts and Giant Cells; pp. 337–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing L., Xiu Y., Boyce B.F. Osteoclast fusion and regulation by RANKL-dependent and independent factors. World J. Orthop. 2012;3:212. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v3.i12.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi M., Miyamoto T., Sawatani Y., Iwamoto K., Hosogane N., Fujita N., Morita K., Ninomiya K., Suzuki T., Miyamoto K., Oike Y., Takeya M., Toyama Y., Suda T. DC-STAMP is essential for cell–cell fusion in osteoclasts and foreign body giant cells. J. Exp. Med. 2005;202:345–351. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M., Birnbaum M.J., MacKay C.A., Mason-Savas A., Thompson B., Odgren P.R. Osteoclast stimulatory transmembrane protein (OC-STAMP), a novel protein induced by RANKL that promotes osteoclast differentiation. J. Cell. Physiol. 2008;215:497–505. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material