Abstract

Background

The National Lung Screening Trial showed that lung cancer (LC) screening by three annual rounds of low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) reduces LC mortality. We evaluated the benefit of prolonged LDCT screening beyond 5 years, and its impact on overall and LC specific mortality at 10 years.

Design

The Multicentric Italian Lung Detection (MILD) trial prospectively randomized 4099 participants, to a screening arm (n = 2376), with further randomization to annual (n = 1190) or biennial (n = 1186) LDCT for a median period of 6 years, or control arm (n = 1723) without intervention. Between 2005 and 2018, 39 293 person-years of follow-up were accumulated. The primary outcomes were 10-year overall and LC specific mortality. Landmark analysis was used to test the long-term effect of LC screening, beyond 5 years by exclusion of LCs and deaths that occurred in the first 5 years.

Results

The LDCT arm showed a 39% reduced risk of LC mortality at 10 years [hazard ratio (HR) 0.61; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.39–0.95], compared with control arm, and a 20% reduction of overall mortality (HR 0.80; 95% CI 0.62–1.03). LDCT benefit improved beyond the 5th year of screening, with a 58% reduced risk of LC mortality (HR 0.42; 95% CI 0.22–0.79), and 32% reduction of overall mortality (HR 0.68; 95% CI 0.49–0.94).

Conclusions

The MILD trial provides additional evidence that prolonged screening beyond 5 years can enhance the benefit of early detection and achieve a greater overall and LC mortality reduction compared with NLST trial.

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier

Keywords: low-dose computed tomography, screening, early detection, lung cancer, mortality, overdiagnosis

Key Message

MILD is the only randomized trial designed to assess the value of prolonged LC screening beyond 5 years. The 10 years results of MILD trial show a significant 39% reduction of LC mortality in the LDCT arm, providing new evidence that extended intervention enhances the benefit of screening, notwithstanding biennial rounds and active surveillance.

Introduction

Lung cancer (LC) screening by low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) achieved a 20% decrease in LC mortality in the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST), when compared with chest radiography [1], while European randomized clinical trials (RCT) testing LDCT versus observation showed no benefit at 5-year, possibly due to small number of participants and short follow-up [2–4].

The selection criteria were not homogeneous among RCTs [1–8], and most European RCTs enrolled younger populations, with lower LC risk than NLST [2–8]. The majority of RCTs offered annual LDCT rounds for ≤4 years, where the impact of screening duration and intensity was not evaluable.

The Multicentric Italian Lung Detection (MILD) study was designed to investigate the efficacy of prolonged LDCT screening beyond 4 years, including a further randomization between annual and biennial LDCT rounds [4]. Furthermore, MILD implemented positron emission tomography (PET) and active surveillance of subsolid lesions to minimize unnecessary surgery [9, 10]. Early evaluations of MILD trial showed no mortality reduction in the LDCT arm at 5 years [4], and a similar performance of annual versus biennial LDCT in terms of detection rates and interval cancers at 7 years [11]. We report here the 10-year results of MILD, with a focus on overall and LC mortality.

Methods

Study design

The MILD study is a prospective randomized controlled LC screening trial launched in 2005, and initially designed as a National program for multicenter recruitment of 10 000 volunteer smokers (≥20 pack-years, current or former from <10 years), aged from 49 to 75 years, without history of cancer in ≤5 years. However, MILD faced major management difficulties: indeed, the Ethics Committee initially approved only the annual versus biennial LDCT randomization, and final protocol was accepted in December 2005 (protocol ID: INT 53/05; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02837809), with a single center accrual. All eligible subjects provided written informed consent.

Details about Ethics Committee approval, LDCT technique, diagnostic workup, baseline and early outcome of the MILD study were published elsewhere [4].

Patients

A total of 4099 participants were randomized, to a screening arm (n = 2376), with further randomization to annual (n = 1190, LDCT every 12 months) or biennial (n = 1186, LDCT every 24 months) screening, or control arm (n = 1723) without intervention (Table 1). The size discrepancy between the two main arms is the effect of initial randomization to annual (n = 326) or biennial (n = 327) LDCT screening, started in September 2005 on 653 volunteers, with later activation of the final protocol in December 2005, that recruited 3446 additional participants, randomized to LDCT arm (n = 1 723 864 annual and 859 biennial) or control arm (n = 1723) (supplementary Appendix S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 4099 participants in the MILD population, by study arm

| Control arm (N = 1723) | Intervention arm (N = 2376) | P-values | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| <55 | 656 (38.1%) | 773 (32.5%) | 0.0065 | |

| 55–59 | 478 (27.7%) | 700 (29.5%) | ||

| 60–64 | 359 (20.8%) | 535 (22.5%) | ||

| 65–69 | 174 (10.1%) | 278 (11.7%) | ||

| ≥70 | 56 (3.3%) | 90 (3.8%) | ||

| Median age | 57 | 58 | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1090 (63.3%) | 1626 (68.4%) | 0.0005 | |

| Female | 633 (36.7%) | 750 (31.6%) | ||

| Smoking status (smokers) | ||||

| Former | 177 (10.3%) | 747 (31.4%) | <0.0001 | |

| Current | 1546 (89.7%) | 1629 (68.6%) | ||

| Pack-years of cigarette | ||||

| <30 | 485 (28.2%) | 521 (21.9%) | <0.0001 | |

| ≥30 | 1238 (71.9%) | 1855 (78.1%) | ||

| Median pack-years | 38 | 39 | ||

Data collection and follow-up

Socio-demographic data were collected at baseline, together with pulmonary function test and blood samples, for all the 4099 participants [6]. Clinical data were collected during follow-up of participants assigned to both intervention and control arm. Outcome information was implemented by phone calls, email and contacts with general practitioner or referring hospitals, and periodical enquiry to National Statistic and Cancer Registries (Associazione Italiana Registri Tumori, AIRTUM, Istituto Nazionale di Statistica, ISTAT, SIATEL 2.0 platform) to assess vital status, cause of death, LC occurrence and treatment. Participants accumulated person-years of follow-up from the date of randomization until death or date of last follow-up (June 2018).

End points

The main end point of MILD analysis was LC mortality at 10 years; secondary end points were overall mortality and LC diagnosis. The LC features and outcomes were compared in the two arms by the relative difference in cumulative LC incidence, LC stage and resectability, number needed to screen (NNS) and number of LDCT to prevent one LC death.

Statistics

Cumulative overall mortality, LC mortality, ‘other cause’ mortality (other than LC), and LC incidence were calculated by Kaplan–Meier estimation and compared using Log-rank test. Mortality analyses carried out on the 4099 participants granted a 25% power to detect 10% reduction of all-cause mortality and 45% power to detect 30% reduction of LC mortality. Cox proportional hazard regression was used to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for the association between exposure to screening intervention and time of end-points onset. Log-rank tests and HRs were adjusted for age, gender and pack-years to reduce the potential effect of different baseline characteristics (supplementary Appendix S4, available at Annals of Oncology online).

The effect of LC screening beyond 5 years was assessed by adjusted landmark analysis of cumulative overall and LC mortality at 10 years, restricted to the individuals who, in the first 5 years after randomization, were still alive and did not experience LC diagnosis [12]. Sensitivity analyses were carried out by excluding the first 653 randomized volunteers (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online), allowing 22% power to detect 10% reduction of overall mortality and 36% power to detect 30% reduction of LC mortality, and applied to the whole 10-year period, as well as to landmark analyses beyond 5 years.

Results

Descriptive analyses

The overall 10-year mortality was 5.9% (243/4099 subjects, 39 293 person-years; Table 2). The median duration of screening by LDCT was 6.2 years (interquartile range 5.5–6.4). Among the 3856 survivors, 93.5% (n = 3607) of participants reached the 9 years of follow-up and 71% (n = 2739) accumulated 10 years of follow-up. Only one subject was lost to follow-up.

Table 2.

Characteristics of lung cancers and study outcome by study arm, throughout the 10-year follow-up

| Total | Control arm | Intervention arm | P-values | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 4099) | (N = 1723) | (N = 2376) | |||

| Lung cancer incidence | 158 (3.9%) | 60 (3.5%) | 98 (4.1%) | 0.29 | |

| Lung cancer rate (per 100 000) | 407.0 | 372.6 | 431.5 | 0.37 | |

| Person-years (incidence) | 38 816 | 16 102 | 22 714 | ||

| Lung cancer stage | |||||

| I | 62 (39.2%) | 13 (21.7%) | 49 (50.0%) | 0.0004a | |

| II | 9 (5.7%) | 5 (8.3%) | 4 (4.1%) | ||

| III | 26 (16.5%) | 10 (16.7%) | 16 (16.3%) | ||

| IV | 61 (38.6%) | 32 (53.3%) | 29 (29.6%) | ||

| Lung resection | |||||

| None | 78 (49.4%) | 44 (73.3%) | 34 (34.7%) | <0.0001b | |

| Pneumonectomy | 1 (0.6%) | 0 | 1 (1.0%) | ||

| Lobectomy/segmentectomy | 79 (50.0%) | 16 (26.7%) | 63 (64.3%) | ||

| Lung cancer histology | |||||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 30 (24.4%) | 12 (30.0%) | 18 (21.7%) | 0.25c | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 78 (63.4%) | 23 (57.5%) | 55 (66.3%) | ||

| Small cell carcinoma | 10 (8.1%) | 4 (10.0%) | 6 (7.2%) | ||

| Large cell carcinoma | 5 (4.1%) | 1 (2.5%) | 4 (4.8%) | ||

| Carcinoma NOSd | 35 | 20 | 15 | ||

| Lung cancers not screen detected | 86 (54.4%) | 59 (98.3%) | 27 (27.6%) | <0.0001 | |

| Total deaths | 243 (5.9%) | 106 (6.2%) | 137 (5.8%) | 0.61 | |

| Overall mortality rate (per 100 000) | 618.4 | 653.9 | 593.5 | 0.45 | |

| Lung cancer deaths | 80 (2.0%) | 40 (2.3%) | 40 (1.7%) | 0.14 | |

| Lung cancer mortality rate (per 100 000) | 203.6 | 246.8 | 173.3 | 0.12 | |

| Person-years (mortality) | 39 293 | 16 210 | 23 083 | ||

Resection for benign histology was not accounted in the table, it is thereafter summarized: 3 cases in LDCT arm, rate of resection for benign histology 4.5% (3/67); 1 case in control arm, rate of resection for benign histology 5.9% (1/17).

Proportion of stage I.

Proportion of lung resection compared with no lung resection.

Carcinoma NOS excluded.

Carcinoma NOS: carcinoma not otherwise specified.

The overall mortality was 594/100 000 person-years (137 deaths) in intervention arm versus 654/100 000 person-years (106 deaths, P = 0.45) in the control arm. The cause of death was missing in 4.1% of participants (10/243, 3 in intervention and 7 in control arm). Contamination of control arm by LDCT was 1.2% (21/1723), including 1 LC diagnosis (stage I squamous cell carcinoma, alive at the time of data extraction) and 1 death (unknown cause).

LC detection

LC was diagnosed in 98 participants (431/100 000 person-years) in the intervention arm and 60 participants (373/100 000 person-years) in the control arm. The 10-year cumulative LC incidence curves showed a non-significant difference between intervention and control arm (P = 0.84; supplementary Appendix S3, available at Annals of Oncology online). One hundred and fifty-four LDCTs and 1.4 PETs were needed to diagnose one LC cancer. A significantly larger proportion of stage I LC was detected in intervention arm (49/98, 50%) compared with control arm (13/60, 21.7%; P = 0.0004; Table 2), and LC resection rate was 65.3% in intervention arm (64/98) versus 26.7% in control arm (16/60; P < 0.0001).

Three participants underwent minor lung resection for benign histology in the LDCT arm, and one in control arm. The resection rate for benign histology was 4.5% (3/67 resections) in intervention arm and 5.9% (1/17 resections) in control arm (P > 0.99).

Ten-year mortality analysis

Table 2 shows that LC mortality was 173/100 000 person-years (40 deaths) in intervention arm and 247/100 000 person-years in control arm (40 deaths, P = 0.12). LC accounted for 33% of all deaths: 29% in intervention and 38% in control arm. One LC death was prevented by 167 screened subjects (NNS), 733 LDCTs and 4.4 PETs.

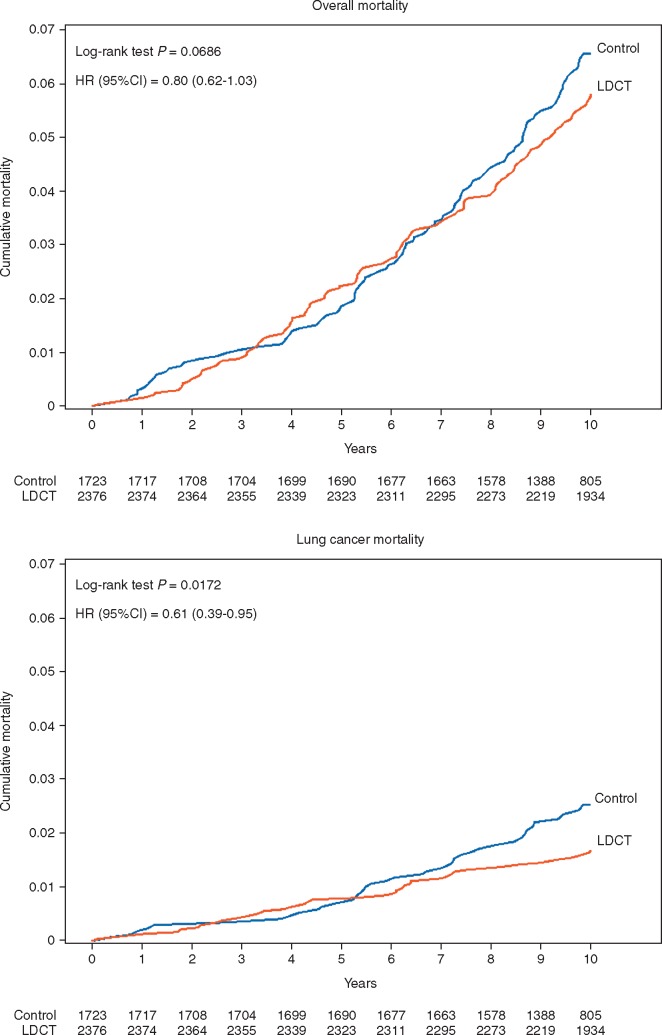

The cumulative risk of 10-year overall mortality was 5.8% in intervention arm and 6.5% in control arm (Figure 1A), with 20% (95% CI -3% to 38%) risk reduction by LDCT (HR 0.80; 95% CI 0.62–1.03; log-rank P = 0.07). The cumulative risk of 10-year LC mortality was 1.7% in intervention arm and 2.5% in control arm, with significant 39% (95% CI 5% to 61%) risk reduction by LDCT screening (HR 0.61; 95% CI 0.39–0.95; P = 0.02) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Cumulative overall mortality and lung cancer mortality, by arm over 10 years of follow-up.

Landmark and sensitivity analyses

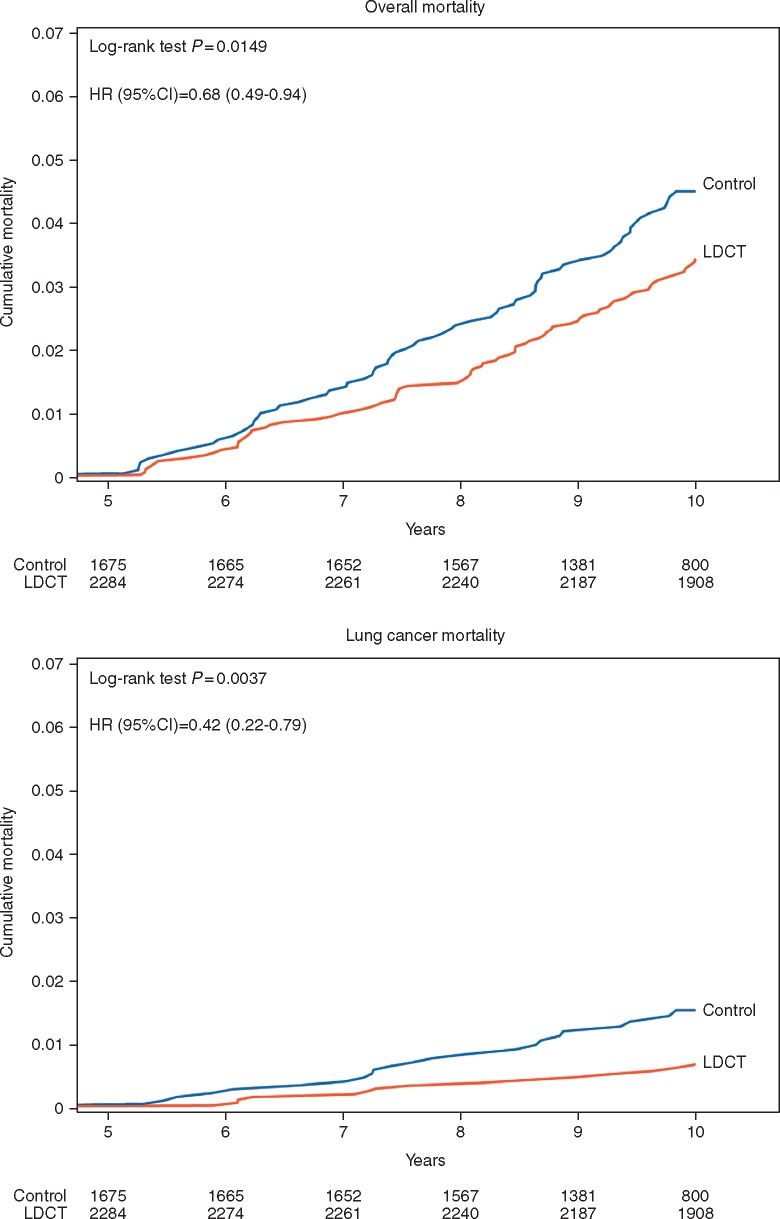

The landmark analysis beyond 5 years showed 3.4% cumulative risk of overall mortality in intervention arm and 4.5% in control arm, with significant 32% (95% CI 6% to 51%) risk reduction by LDCT (HR 0.68; 95% CI 0.49–0.94; P = 0.01) (Figure 2A). The difference was greater for LC mortality, with a cumulative risk of 0.7% in intervention arm versus 1.5% in control arm, corresponding to 58% (95% CI 21% to 78%) risk reduction by LDCT (HR 0.42, 95% CI 0.22–0.79; P = 0.0037) (Figure 2B). The cumulative risk of ‘other cause’ mortality was 2.6% in intervention and 2.5% in control arm (HR 0.91; 95% CI 0.61–1.37; P = 0.65).

Figure 2.

Landmark analysis of cumulative overall mortality and lung cancer mortality, by arm beyond 5 years.

The sensitivity analysis on 3446 participants replicated the estimates for overall mortality and LC mortality reduction, even though statistical significance was not reached (supplementary Appendix S5, available at Annals of Oncology online). A statistically significant 49% risk reduction of LC mortality by LDCT was maintained in the sensitivity landmark analysis (HR 0.51; 95% CI 0.26–1.01; P = 0.049; supplementary Figure S6, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Discussion

Principal findings

MILD is the only randomized LC screening trial designed to assess the value of prolonged intervention. As a secondary aim, MILD compared the efficacy of two different LDCT intervals. The long-term results of MILD trial show a statistically significant and clinically relevant 39% reduction of LC mortality at 10 years in the LDCT arm, along with a non-significant 20% decrease of overall mortality. With a median active LDCT screening period of 6.2 years, landmark analysis of MILD trial revealed that the benefit of screening could be kept beyond 5 years, with 58% LC mortality reduction and 32% overall mortality reduction (both statistically significant), and the sensitivity analyses on the more homogeneous cohort of 3446 subjects confirmed a significant 49% LC mortality reduction beyond 5 years, despite lower statistical power.

Comparison with previous studies

In 2011, the NLST reported a 20% LC mortality reduction after 2 years of annual LDCT screening, with chest radiography as control arm [3]. The negative outcome of MILD trial at 5 years [4] caused some controversy [13], even though our data mirrored the results of DLCST and DANTE trials [2, 3]. In the light of current LDCT screening knowledge, early failure of European RCTs can be attributed to relatively small populations, insufficient length of intervention and/or follow-up. As a matter of fact, pooled analysis of MILD and DANTE, with 6549 subjects and 52 637 person-years, detected a 17% LC mortality reduction at 8 years, quite close to NLST even if not statistically significant [14], and ITALUNG trial showed 30% mortality reduction at 9-year follow-up with only 3152 participants [6].

The 39% reduction of LC mortality obtained by MILD trial at 10 years represents a confirmation of the efficacy of LDCT screening since the NLST results in 2011 [3]. In fact, the LC death rate of 247/100 000 person-years in MILD controls versus 309/100 000 person-years in NLST chest radiography arm [3] can be explained by the different risk profile, as only 51% of MILD participants met the NLST eligibility criteria. Nonetheless, the decrease of 10-year LC mortality rate was more substantial in intervention arm of MILD when compared with NSLT (173 versus 247 per 100 000 person-years, respectively), as well as the relative LC mortality reduction (39% versus 20%, respectively).

The benefit of LDCT screening in MILD was specifically attributable to LC mortality reduction, driven by extended early LC diagnosis beyond five, without impact on mortality from other causes. Indeed, it appears reasonable that 10-year results of MILD were empowered by the continuous contribution of prolonged LDCT screening, which reversed the earlier negative 5-year figures [4].

Reducing screening intensity by extended LDCT intervals to optimize cost-effectiveness and limit radiation dose is a current matter of debate [15–17]. A low-intensity screening design was implemented by MILD and the Nederlands-Leuvens Longkanker Screenings ONderzoek (NELSON) trial, with different methodological approaches: MILD tested two different screening intervals through the whole duration of trial, by upfront randomization to either annual or biennial LDCT, whereas NELSON analyzed three consecutive rounds with different longitudinal intervals in the same subject [18]. The final 2.5-year round of NELSON found more than twice stage III/IV and five times interval cancer when compared with 1-year round [18]. The biennial arm of MILD randomly tested longer screening intervals after a negative baseline LDCT, with annual repeats only in case of indeterminate LDCT (<20% of participants in biennial arm). MILD algorithm granted a similar proportion of stage I, LC resections, and interval cancers between annual and biennial LDCT, with lower costs and radiation exposure [11]. In accordance with retrospective evaluations supporting lower intensity after negative baseline LDCT [19, 20], MILD results at 10 years provide indirect evidence that tailored biennial LDCT did not compromise the efficacy of prolonged screening duration [11], but this issue will require future confirmation by a multicentric randomized trial with adequate sample size. Individual risk stratification by LDCT and blood microRNAs [21] is currently being tested by the on-going prospective bioMILD trial, which schedules triennial rounds for subjects with negative baseline LDCT and microRNAs [22, 23].

Strengths and limitations

Early detection by screening carries the burden of overdiagnosis and overtreatment of benign or indolent disease, and the extent of phenomenon depends on the methodology used to estimate overdiagnosis: ranging from 18.5% in NLST [24] to 67.5% in DLCST [25]. With the aim of reducing unnecessary surgery, MILD protocol implemented active surveillance of subsolid lesions that ultimately proved to be a safe strategy for slow growing nodules [10], which represent the majority of over-diagnosed and over-treated lung adenocarcinomas [25]. Moreover, selective use of PET improved differential diagnosis [9], resulting in a 4.5% resection rate for benign histology, compared with 24.4% of NLST [1], 10.3% of UKLS [8] and the 15% threshold recommendation by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) [26].

The MILD study suffers from a few limitations. First, the sample size reduced the statistical power and may have contributed to the negative early results [4]. Secondly, the sequential randomization methodology, determined by ethical and administrative hurdles (e.g. opposition against an observational control arm) affected the accrual process and the final population balance. Hence, the assessment of screening effect on long-term LC cancer mortality required adjusted analysis, even if confirmed by unadjusted and sensitivity analyses. Finally, only 71% of participants completed the 10 years of follow-up, even though the 93.5% at 9 years allowed reasonable assessment of long-term outcome.

Conclusions

The MILD trial provides additional evidence that prolonged intervention beyond 5 years can enhance the benefit of screening. The incremental effect of prolonged LC screening achieved a significant mortality reduction at 10 years, notwithstanding biennial rounds and active surveillance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Associazione Italiana Registri Tumori (AIRTUM) for data retrieval, Elena Bertocchi for project management, Claudio Jacomelli for data management, Paola Suatoni for MILD biobanking, and the MILD staff (Chiara Banfi, Annamaria Calanca, and Carolina Ninni).

Funding

The MILD trial was supported by grants from the Italian Ministry of Health (RF 2004), the Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC 2004 IG 1227 and AIRC 5xmille IG 12162), Fondazione Cariplo (2004-1560) and the National Cancer Institute (EDRN UO1 CA166905). The sponsors had no role in conducting and interpreting the study.

Disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.National Lung Screening Trial Research Team, Aberle DR, Adams AM. et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 395–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Infante M, Cavuto S, Lutman FR. et al. Long-term follow-up results of the DANTE trial, a randomized study of lung cancer screening with spiral computed tomography. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015; 191(10): 1166–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wille MM, Dirksen A, Ashraf H. et al. Results of the randomized Danish lung cancer screening trial with focus on high-risk profiling. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016; 193(5): 542–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pastorino U, Rossi M, Rosato V. et al. Annual or biennial CT screening versus observation in heavy smokers: 5-year results of the MILD trial. Eur J Cancer Prev 2012; 21(3): 308–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Scholten ET, Horeweg N, de Koning HJ. et al. Computed tomographic characteristics of interval and post screen carcinomas in lung cancer screening. Eur Radiol 2015; 25(1): 81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Paci E, Puliti D, Lopes Pegna A. et al. Mortality, survival and incidence rates in the ITALUNG randomised lung cancer screening trial. Thorax 2017; 72(9): 825–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Becker N, Motsch E, Gross ML. et al. Randomized study on early detection of lung cancer with MSCT in Germany: results of the first 3 years of follow-up after randomization. J Thorac Oncol 2015; 10(6): 890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Field JK, Duffy SW, Baldwin DR. et al. UK Lung Cancer RCT Pilot Screening Trial: baseline findings from the screening arm provide evidence for the potential implementation of lung cancer screening. Thorax 2016; 71(2): 161–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pastorino U, Bellomi M, Landoni C. et al. Early lung-cancer detection with spiral CT and positron emission tomography in heavy smokers: 2-year results. Lancet 2003; 362(9384): 593–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Silva M, Prokop M, Jacobs C. et al. Long-term active surveillance of screening detected subsolid nodules is a safe strategy to reduce overtreatment. J Thorac Oncol 2018; 13(10): 1454–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sverzellati N, Silva M, Calareso G. et al. Low-dose computed tomography for lung cancer screening: comparison of performance between annual and biennial screen. Eur Radiol 2016; 26(11): 3821–3829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Anderson JR, Cain KC, Gelber RD.. Analysis of survival by tumor response. J Clin Oncol 1983; 1(11): 710–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tammemagi MC, Lam S.. Screening for lung cancer using low dose computed tomography. BMJ 2014; 348: g2253.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Infante M, Sestini S, Galeone C. et al. Lung cancer screening with low-dose spiral computed tomography: evidence from a pooled analysis of two Italian randomized trials. Eur J Cancer Prev 2017; 26(4): 324–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goffin JR, Flanagan WM, Miller AB. et al. Biennial lung cancer screening in Canada with smoking cessation-outcomes and cost-effectiveness. Lung Cancer 2016; 101: 98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Patz EF Jr, Greco E, Gatsonis C. et al. Lung cancer incidence and mortality in National Lung Screening Trial participants who underwent low-dose CT prevalence screening: a retrospective cohort analysis of a randomised, multicentre, diagnostic screening trial. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17(5): 590–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. van der Aalst CM, Ten Haaf K, de Koning HJ.. Lung cancer screening: latest developments and unanswered questions. Lancet Respir Med 2016; 4(9): 749–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yousaf-Khan U, van der Aalst C, de Jong PA. et al. Final screening round of the NELSON lung cancer screening trial: the effect of a 2.5-year screening interval. Thorax 2017; 72(1): 48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yousaf-Khan U, van der Aalst C, de Jong PA. et al. Risk stratification based on screening history: the NELSON lung cancer screening study. Thorax 2017; 72(9): 819–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schreuder A, Schaefer-Prokop CM, Scholten ET. et al. Lung cancer risk to personalise annual and biennial follow-up computed tomography screening. Thorax 2018; 73(7): 626–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sozzi G, Boeri M, Rossi M. et al. Clinical utility of a plasma-based miRNA signature classifier within computed tomography lung cancer screening: a correlative MILD trial study. JCO 2014; 32(8): 768–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pastorino U, Sestini S; https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT02247453 (13 March 2019, date last accessed).

- 23. Seijo LM, Peled N, Ajona D. et al. Biomarkers in lung cancer screening: achievements, promises, and challenges. J Thorac Oncol 2019; 14(3): 343–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Patz EF Jr, Pinsky P, Gatsonis C. et al. Overdiagnosis in low-dose computed tomography screening for lung cancer. JAMA Intern Med 2014; 174(2): 269–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Heleno B, Siersma V, Brodersen J.. Estimation of overdiagnosis of lung cancer in low-dose computed tomography screening: a secondary analysis of the Danish lung cancer screening trial. JAMA Intern Med 2018; 178(10): 1420–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wood DE. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Clinical Practice Guidelines for Lung Cancer Screening. Thorac Surg Clin 2015; 25(2): 185–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.