Abstract

Women with psychiatric disorders during pregnancy and the postpartum period (i.e., perinatal period) are at increased risk for adverse maternal and child outcomes. Effective treatment of psychiatric disorders during the perinatal period is imperative. This review summarizes the outcomes of 78 studies focused on the treatment of depression, anxiety, and trauma-related disorders during the perinatal period. The majority of studies focused on perinatal depression (n = 73). Of the five studies focused on anxiety or trauma-related disorders, only one was a randomized controlled trial (RCT). The most studied treatment was cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT; n = 22), followed by interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT; n = 13). Other interventions reviewed include other talk therapies (n = 5), collaborative care models (n = 2), complementary and alternative medicine approaches (n = 18), light therapy (n = 3), brain stimulation (n = 2), and psychopharmacological interventions (n = 13). Eleven studies focused specifically on treatment for low-income and/or minority women. Both CBT and IPT demonstrated a significant benefit over control conditions. However, findings were mixed when these interventions were examined in low-income and/or minority samples. There is some support for complementary and alternative medicine approaches (e.g., exercise). Although scarce, SSRIs demonstrated good efficacy when compared to a placebo. However, SSRIs did not outperform another active treatment condition (e.g., CBT). There is a tremendous need for more studies focused on treatment of perinatal anxiety and trauma-related disorders, as well as psychopharmacological effectiveness studies. Limitations and future directions of perinatal treatment research, particularly among low-income and/or minority populations, are discussed.

Keywords: Anxiety, Depression, Posttraumatic stress disorder, Treatment, Pregnancy, Postpartum

1. Introduction

For individuals with psychiatric disorders, pregnancy and the postpartum period (hereinafter referred to as the perinatal period) constitute times of increased risk. Epidemiological data find that the prevalence of minor and major depression is 18% during pregnancy and 19% during the first 3 postpartum months (Gavin et al., 2005) with higher rates among low-income women (27% and 23%, respectively; Hobfoll, Ritter, Lavin, Hulsizer, & Cameron, 1995). The prevalence of any anxiety disorder during pregnancy and the postpartum period is 13% (Vesga-López, Blanco, & Keyes, 2008) and the prevalence of PTSD during pregnancy is 8% (Seng, 2009). Additionally, suicide is a leading cause of maternal death in the postpartum period among women with psychiatric disorders (Lindahl, Pearson, & Colpe, 2005). Of note, prevalence rates of psychiatric disorders during the perinatal period are similar to prevalence rates in non-pregnant women (Vesga-López et al., 2008) and relapse of psychiatric illness during the perinatal period is common, particularly among women who discontinue psychiatric treatment (Cohen et al., 2006), contradicting a long held misconception that pregnancy is protective against relapses of psychiatric disorders.

Women with depression, anxiety, and PTSD during pregnancy are at increased risk for experiencing postpartum psychiatric disorders (Muzik et al., 2016; Robertson, Grace, Wallington, & Stewart, 2004; Sutter-Dallay, Giaconne-Marcesche, Glatigny-Dallay, & Verdoux, 2004) and impaired maternal-infant bonding (Muzik et al., 2016). Women with psychiatric disorders during the perinatal period are also at greater risk of experiencing negative physical health outcomes and negative birth outcomes. For example, pregnant women with anxiety and/or depressive symptoms report more nausea and vomiting, take more sick days, and visit their obstetrician more often during their pregnancy than women without anxiety and/or depression (Alder, Fink, Bitzer, Hosli, & Holzgreve, 2007). Women with psychiatric conditions are also significantly more likely to experience preterm birth (i.e., birth prior to 37 weeks gestation), lower than average birth weight infants (i.e., < 2500 g), an increased rate of cesarean delivery, and an increased likelihood that their infant will be admitted to the neonatal care unit (Chung, Lau, Yip, Chiu, & Lee, 2001; Grote et al., 2010; Yonkers et al., 2014). These data suggest that women with psychiatric conditions during pregnancy experience compounded mental, physical, and obstetric problems during and following childbirth. The psychological, medical, and economic burden of obstetric complications such as preterm birth is substantial. For example, preterm infants are at increased risk for neurodevelopmental impairments (e.g., cognitive deficits), neuropsychiatric impairments (e.g., executive function deficits, psychopathology), and medical complications (e.g., chronic health disorders) that persist well into adulthood (Saigal & Doyle, 2008). Furthermore, maternal psychiatric conditions during the postpartum period adversely affect children’s cognitive, emotional, and behavioral development (Grace, Evindar, & Stewart, 2003).

Given the substantial impact of perinatal psychiatric conditions on both the mother and child, effective treatment during this period is imperative. Therefore, the aims of the current study were to: a) review the existing literature on the treatment of depression, anxiety, and trauma-related disorders during the perinatal period; b) review interventions specifically for perinatal low-income and/or minority women, given that they are less likely to receive adequate care (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], 2001) and are more likely to dropout of treatment, (Arnow et al., 2007) despite being more likely to be diagnosed with perinatal psychiatric disorders (Hobfoll et al., 1995); and c) highlight gaps and areas of future treatment research in this area. The current review is more inclusive as compared to past reviews on this topic in order to provide a comprehensive review of potential treatment options for women suffering from the most common mood and anxiety disorders (i.e., depression, anxiety, and trauma-related disorders) during the perinatal period. First, included studies did not require participants to have a diagnosed psychiatric disorder at baseline, although presence of clinically elevated symptoms was required. The definition of clinically elevated symptoms varied based on the study and measure used; however, most typically it included a predetermined cut off score based on a self-report measure (see Appendices A and B for detailed inclusion criteria by individual study). Additionally, open label trials with no control condition were included in this review given that these early studies provide extremely important information regarding potential innovative treatments for this population. Finally, all types of treatments were included in this review, including psychosocial, psychopharmacological, complementary and alternative medicine approaches, and collaborative care models.

2. Method

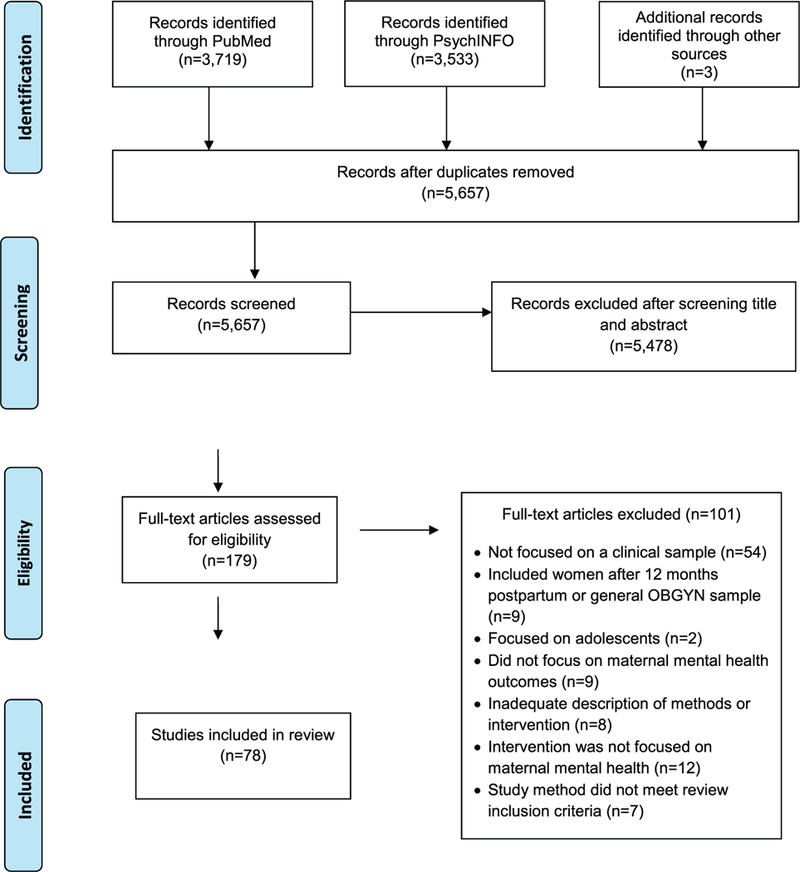

Guidelines outlined by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & Group, 2009) were followed for this review. The PRISMA statement was developed to provide guidelines for reporting the results of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. It includes a 27-item checklist, which outlines the sections/topics to be included in a systematic review, and a four-phase flow diagram, which describes the phases of the systematic review. Additionally, methodological quality of the studies were assessed based on guidelines recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins, Altman, Gotzsche, Juni, & Moher, 2011).

2.1. Search criteria

Studies were identified by searching all fields in PubMed and PsychINFO electronic databases. The following search terms were combined: (((((((((((((((postpartum posttraumatic stress disorder) OR (pregnancy AND posttraumatic stress disorder)) OR postpartum depress*) OR (pregnancy AND depress*)) OR postpartum mood disorder) OR (pregnancy AND mood disorder)) OR postpartum anxiety) OR (pregnancy AND anxiety)) OR postpartum panic disorder) OR (pregnancy AND panic disorder)) OR postpartum social anxiety disorder) OR (pregnancy AND social anxiety disorder)) OR postpartum generalized anxiety disorder) OR (pregnancy AND generalized anxiety disorder)) OR postpartum obsessive compulsive disorder) OR (pregnancy AND obsessive compulsive disorder) AND ((((((((therap*) OR cognitive behavior* therapy) OR interpersonal psychotherapy) OR treatment) OR evidence based treatment) OR (acceptance and commitment therapy)) OR pharmacotherapy) OR medication) OR medicine). See Table 1 for search strategy. The search was conducted on April 6, 2017 and studies of adult human subjects published through April 6, 2017 were included. Additional studies were retrieved from reference lists of relevant articles.

Table 1.

Search strategy.

| Set | Search term |

|---|---|

| 1 | postpartum posttraumatic stress disorder |

| 2 | pregnancy AND posttraumatic stress disorder |

| 3 | postpartum depress* |

| 4 | pregnancy AND depress* |

| 5 | postpartum mood disorder |

| 6 | pregnancy AND mood disorder |

| 7 | postpartum anxiety |

| 8 | pregnancy AND anxiety |

| 9 | postpartum panic disorder |

| 10 | pregnancy AND panic disorder |

| 11 | postpartum social anxiety disorder |

| 12 | pregnancy AND social anxiety disorder |

| 13 | postpartum generalized anxiety disorder |

| 14 | pregnancy AND generalized anxiety disorder |

| 15 | postpartum obsessive compulsive disorder |

| 16 | pregnancy AND obsessive compulsive disorder |

| 17 | Sets 1–16 were combined with OR |

| 18 | therap* |

| 19 | cognitive behavior* therapy |

| 20 | interpersonal psychotherapy |

| 21 | treatment |

| 22 | evidence based treatment |

| 23 | acceptance and commitment therapy |

| 24 | pharmacotherapy |

| 25 | medication |

| 26 | Medicine |

| 27 | Sets 18–26 were combined with OR |

| 28 | Sets 17 and 27 were combined with AND |

| 29 | Set 28 was limited to Humans and Adults (18+) |

2.2. Selection criteria

In order to be included in the review, studies were required to: 1) be available in English; 2) focus on adults (ages 18 or over); 3) include individuals with a diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), major depressive disorder (MDD), panic disorder (PD), social anxiety disorder (SAD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), specific phobia (SP), or obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) based on a diagnostic interview or clinically elevated levels of psychological symptoms on clinician-administered or self-report measures. We chose to focus on depression, anxiety, and trauma-related disorders only, given that treatment for these disorders, particularly psychopharmacological treatment, is similar; 4) include pregnant or postpartum (i.e., up to 12 months) women; 5) include an intervention which targeted maternal mental health symptoms; 6) describe pre- to post-treatment psychological symptom outcomes; and 7) employ a randomized controlled trial (RCT) or open trial (OT) design, including pilot studies. The following studies were excluded from this review: 1) treatment of mood disorders with the exception of depression (e.g., bipolar disorder); 2) interventions focused on improving infant outcomes or the mother-infant relationship; 3) interventions focused on prevention of maternal psychopathology in an at-risk, but not currently symptomatic, population; and 4) case-series and case reports. See Fig. 1 for flow chart of studies included in the systematic review.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of studies included in systematic review.

3. Results

3.1. Available treatments

The search strategy revealed a total of 5657 articles after removal of duplicates. Following an initial review of titles and abstracts, 179 articles were assessed for eligibility, and 78 articles met the inclusion criteria. A total of 73 studies were focused on treatment of depression, 3 on treatment of an anxiety disorder (i.e., specific phobia, social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and panic disorder), and 2 on treatment of PTSD. There were no studies that focused on treatment of PD or OCD. Among the small number of studies that focused on perinatal anxiety and PTSD, 80% (n = 4) of them were OT studies. Among the studies that focused on perinatal depression, 25% (n = 18) were OT and 75% (n = 55) were RCTs. Intervention strategies included: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT), other talk therapies (i.e., peer support, listening visits, and psycho-education), collaborative care models, exercise, yoga, massage, acupuncture, light therapy, food supplements (i.e., omega-3 fatty acids), brain stimulation, and psychopharmacological therapies. Control conditions used in the RCTs included treatment as usual, waitlist control, placebo, psycho-education, or an enhanced usual care condition. A total of 11 studies specifically focused on perinatal interventions for low-income and/or minority women.

Studies employed a wide range of self-report and clinician administered measures to assess diagnosis and treatment outcome. However, the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS; Cox, Holden, & Sagovsky, 1987) was the most commonly used self-report symptom measure and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (Hamilton, 1960) was the most commonly used clinician-rated measure. The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale is frequently abbreviated multiple ways (i.e., HRSD, HDRS, HAM-D); therefore, to aid in clarity we refer to any use of this measure as HRSD within the manuscript and tables.

A risk bias assessment revealed that, in general, OT studies and pilot studies had greater risk of bias than RCTs. For example, open trial studies were by design non-randomized and, therefore, subject to selection bias. Additionally, the majority of non-pharmacological interventions were unable to blind participants and personnel to the treatment condition they were assigned, given that the intervention being delivered was obvious (e.g., CBT, exercise, yoga). Therefore, the inability to blind both the participants and personnel to the treatment condition could potentially contribute to an increase in performance bias. The majority of the non-pharmacological studies utilized a formal protocol to standardize treatment delivery, and a little more than half of the reviewed studies used an intent to treat (ITT) data analytic strategy to control for attrition bias. The majority of the studies reviewed relied on a self-report measure to determine intervention effectiveness, which could lead to a high risk of bias if the participant was not blind to the study condition. Appendix A and B summarize the key elements of all included non-pharmacological and psychopharmacological treatment studies, respectively. Appendix C summarizes the risk of bias for all studies.

3.2. Anxiety and trauma- and stress-related disorders

3.2.1. Cognitive behavioral therapy

Three OT studies have been conducted to examine treatment for an anxiety disorder during the perinatal period using a CBT intervention. In one trial (N = 76), pregnant women, who met criteria for blood and injection phobia, received prolonged exposure to needles, syringes, blood draws, and IVs during two group sessions. The women who received prolonged exposure (N = 30) experienced a greater reduction in anxiety and avoidance symptoms as compared to women who were not treated (Lilliecreutz, Josefsson, & Sydsjo, 2010). Goodman et al. (2014) tested a group mindfulness based cognitive therapy intervention among pregnant women (N = 24) with clinical levels of anxiety and worry and found that women reported clinically significant reductions in anxiety, worry, and depressive symptoms pre- to post-treatment. Finally, Green, Haber, Frey, and McCabe (2015) tested a group CBT intervention among pregnant and postpartum women (N = 10), who met criteria for either generalized anxiety disorder or social anxiety disorder, and found that women experienced a significant reduction in both anxiety and depressive symptoms pre- to post-treatment.

Shaw and colleagues (2013, 2013) are the only group to test an intervention for traumatic stress in the perinatal period. Specifically, they examined the effectiveness of a 6-session CBT intervention conducted in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, starting in the immediate postpartum period (1–2 weeks after delivery) among women who had a pre-term delivery (i.e., born between 26 and 34 weeks) and reported clinical levels of depression, anxiety, or PTSD. The intervention focused on psycho-education around caring for their premature infant, cognitive restructuring, progressive muscle relaxation, construction of a trauma narrative, and working on her perceptions of her infant and parenting (i.e., infant redefinition). The preliminary OT study demonstrated promising results (Shaw, Sweester, et al., 2013), and the follow-up RCT (N = 105), which randomized women to either the CBT intervention or usual care plus a parent mentor program (i.e., support and coping strategies), found that women in the CBT condition reported significantly greater reduction of PTSD and depressive symptoms (but not anxiety symptoms) as compared to the women in the control condition pre- to post-treatment (Shaw, St. John, et al., 2013).

3.3. Major depressive disorder

3.3.1. Cognitive behavioral therapy

There were a total of 3 OT studies, 12 RCTs, and 2 cluster RCTs that used CBT for depression. A total of 8 studies focused on treatment during pregnancy and 9 focused on treatment during the postpartum period. A total of 10 studies enrolled women if they had clinical levels of depressive symptoms on self-report depression measures such as the EPDS, and 8 studies only enrolled women who met DSM-IV or ICD-10 criteria for depression based on clinician-administered interviews such as the SCID.

3.3.1.1. In-person CBT.

One OT, 6 RCTs, and 1 cluster RCT examined individual or group in-person CBT for pregnant (N = 4) and postpartum (N = 4) women. The OT intervention for postpartum women included modules related to psycho-education, assertiveness, self-esteem, and cognitive restructuring, as well as “baby and me” sessions (i.e., baby massage and playtime). This trial found significant decreases in both depressive and anxiety symptoms pre- to post-treatment (Marrs, 2013). There have been several RCTs for pregnant (N = 4) and postpartum (N =1) women that have incorporated modules related to increasing interpersonal support and/or improving communication along with more traditional CBT modules (e.g., cognitive restructuring, behavioral activation). In all four of these trials, women in the active CBT treatment condition reported significantly less depressive symptoms at post-treatment as compared to women in the control conditions (Burns et al., 2013; Cho, Kwon, & Lee, 2008; Dimidjian et al., 2017; Muresan-Madar & Baban, 2015). Milgrom, Negri, Gemmill, McNeil, and Martin (2005) conducted an RCT to examine the efficacy of group CBT vs. group counseling (i.e., supportive listening and problem solving) vs. individual counseling vs. routine care for postpartum women. The CBT and counseling interventions were conducted by therapists in the clinic. Results from this trial revealed that women in the CBT and counseling interventions reported a significantly greater reduction in depressive and anxiety symptoms at post-treatment as compared to women in routine primary care, but were not significantly different from each other. Milgrom et al. (2011) conducted another RCT for postpartum women executed within primary care, which compared general practitioner depression management alone vs. general practitioner depression management + CBT informed counseling delivered by a postnatal nurse vs. general practitioner depression management + CBT informed counseling delivered by a psychologist. Results of this trial revealed that although women in all three treatment conditions experienced a significant decrease in depressive symptoms across treatment, there were no significant differences between the three conditions. In a cluster RCT, McGregor, Coghlan, and Dennis (2014) examined brief CBT for pregnant women delivered by the physician providing prenatal care via six 10-min individual sessions as compared to standard prenatal care. There were no significant differences between the conditions in depressive symptoms at post-treatment (i.e., 38 weeks gestational age); however, women who received the CBT intervention were significantly less likely to have an EPDS score > 9 as compared to women in usual care at 6 weeks postpartum (19% vs. 48%).

3.3.1.2. Online, computer-assisted and telephone CBT.

A total of 2 OTs and 5 RCTs using computer or telephone administered CBT have been conducted. All but one trial focused on postpartum depression. One large trial (N = 343) of postpartum women compared online behavioral activation to a wait list control group and found that women in the online behavioral activation condition were significantly less likely to be depressed at post-treatment as compared to women in the wait list control condition (63% vs. 44% with an EPDS score < 12; O’Mahen, Himle, et al., 2013). An online CBT intervention for postpartum women that also included weekly coaching calls to support the use of CBT strategies has been conducted in both Australia (i.e., RCT of MumMoodBooster) and the U.S. (i.e., OT of MomMoodBooster). MumMoodBooster demonstrated robust effects on depression. Specifically, women in the online intervention were less likely to meet criteria for MDD at post-treatment as compared to women in the treatment as usual group (79% vs. 18% no longer meeting criteria for MDD based on the SCID; Milgrom et al., 2016). MomMoodBooster, which was based on Milgrom’s MumMoodBooster program, also demonstrated promising effects in the OT. Specifically, women reported a significant decrease in depressive symptoms at post-treatment with 90% no longer meeting criteria for major or minor depression on the PHQ-9 (Danaher et al., 2013). A similar online CBT intervention, which also included weekly check-ins (via email) by a therapist to provide support and answer questions, found that women who completed the online intervention reported a significantly greater reduction in depressive symptoms at post-treatment as compared to women in the wait list control condition (Pugh, Hadjistavropoulos, & Dirkse, 2016). Ngai, Wong, Leung, Chau, and Chung (2015) are the only group to test a telephone-based CBT intervention conducted by midwives in the immediate postpartum period (i.e., within 1 week postpartum). Women in the telephone intervention reported significantly less depressive symptoms at post-treatment as compared to women in the treatment as usual condition (32% in the CBT group vs. 55% in the treatment as usual group continued to have an EPDS score ≥ 10). Finally, a small OT study (N = 10) examined the effect of a computer-assisted CBT intervention, which included individual sessions with the therapist followed by 25–35 min computer sessions that featured videos of individuals using different CBT skills. Women demonstrated significantly reduced depressive symptoms at post-treatment with 80% achieving a treatment response (i.e., HRSD score < 10 and a 50% reduction in symptoms from baseline to post-treatment; Kim, Hantsoo, Thase, Sammel, & Epperson, 2014).

3.3.1.3. CBT for low income and/or minority women.

Two RCTs and 1 cluster RCT have examined a CBT intervention specifically for low-income and/or minority (primarily African American) pregnant women. In a pilot RCT (N = 55) of low-income pregnant women, O’Mahen, Himle, Fedock, Henshaw, and Flynn (2013) found that women who participated in a modified CBT program (i.e., addition of an engagement session to assess treatment goals and address potential barriers to treatment) reported a significantly greater reduction of depressive symptoms at post-treatment and the 3-month follow-up as compared to women who received treatment as usual. Jesse et al. (2015) developed a program for rural low-income pregnant women that included: a) CBT delivered in the clinic and adapted for racial and ethnic minorities, b) resources to reduce barriers (e.g., childcare, food), and c) case management. When women enrolled in this intervention were compared to women enrolled in treatment as usual, only a trend difference emerged between the groups at post-treatment and follow-up. However, when African American women were examined separately, those enrolled in the CBT program reported a significantly greater reduction in depressive symptoms at post-treatment as compared to African American women in the treatment as usual condition. In a large cluster RCT (N = 903) conducted in rural Pakistan, a low-income and low-resourced setting, community health workers were trained in a CBT intervention, which they delivered to pregnant women at home from the last month of their pregnancy through the first 10 postpartum months (Rahman, Malik, Sikander, Roberts, & Creed, 2008). Women enrolled in the CBT intervention reported significantly lower depressive symptoms and were less likely to have a diagnosis of depression at 6 and 12 months postpartum as compared to women in the control condition (23% vs. 53% and 27% vs. 59% had a diagnosis of depression at 6 and 12 months, respectively).

3.3.2. Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT)

There were a total of 6 OT studies, 6 RCTs, and 1 cluster RCT that examined the use of IPT for depression. A total of 6 studies focused on treatment during pregnancy, 6 focused on treatment during the post-partum period, and 1 focused on treatment during either pregnancy or the postpartum period. A total of 3 studies enrolled women if they had clinical levels of depressive symptoms on self-report depression measures such as the EPDS, and 10 studies only enrolled women who met DSM-IV or ICD-10 criteria for depression based on clinician-administered interviews such as the SCID.

3.3.2.1. In-person IPT.

Five OT and 2 RCTs examined individual or group in-person IPT for pregnant (n = 2) and postpartum (n = 5) women. The 3 OT studies that examined IPT among pregnant (N = 1) and postpartum (N = 2) women found that women reported a significant decrease in depressive symptoms pre- to post-treatment (Klier, Muzik, Rosenblum, & Lenz, 2001; Reay, Fisher, Robertson, Adams, & Owen, 2006; Spinelli, 1997). Pessagno and Hunker (2013) examined a brief (8 sessions) IPT-informed group treatment within the context of an OT. The intervention consisted of unstructured group sessions with a focus on becoming more aware of thoughts and feelings and how they impact the individuals’ interactions with others, as well as using group interactions to inform relationship issues and role transitions. This trial revealed that depressive symptoms significantly decrease pre- to post-treatment and that this decrease was maintained at the 6-month follow-up visit. A small OT tested a partner-assisted IPT for pregnant or postpartum (i.e., within 12 weeks) women married or cohabiting with a partner, whereby IPT was combined with elements borrowed from emotionally focused couple therapy (Brandon et al., 2012). This trial found that women experienced a significant decrease in depressive symptoms pre- to post-treatment, which was maintained at the 6-week follow-up assessment. Two RCTs, which examined the effectiveness of IPT among postpartum women, found that women in the IPT condition reported a significantly greater decrease in depressive symptoms at post-treatment and were more likely to recover from depression as compared to women in the control conditions (Mulcahy, Reay, Wilkinson, & Owen, 2010; O’Hara, Stuart, Gorman, & Wenzel, 2000).

3.3.2.2. Telephone-delivered IPT.

One cluster RCT tested the efficacy of telephone-delivered IPT by certified nurse midwives as compared to treatment as usual for postpartum women. They found that women who received IPT reported a significantly greater reduction in depressive symptoms at post-treatment as compared to women in the treatment as usual condition on the HRSD (but not on the EPDS; Posmontier, Neugebauer, Stuart, Chittams, & Shaughnessy, 2016).

3.3.3. IPT for low income and/or minority women

One OT and 4 RCTs have examined IPT specifically for low income and/or minority (i.e., African American and Hispanic) women. In a small OT of low-income pregnant women, Grote, Bledsoe, Swartz, and Frank (2004) tested a culturally relevant enhanced brief IPT protocol (i.e., 8 sessions) followed by maintenance IPT for up to 6 months postpartum (i.e., biweekly for the first 3 months and then monthly until 6 month postpartum) delivered in either the OBGYN clinic in conjunction with prenatal visits or by phone. Modifications included a pre-treatment engagement session and ethnographic interview, psychoeducation, and flexibility in treatment delivery (i.e., phone sessions and flexible scheduling). In this trial, women experienced a significant reduction in depressive symptoms with no one meeting criteria for MDD at post-treatment, which persisted at the 6-month follow-up assessment. Two small RCTs have examined Grote et al.’s (2004) intervention as compared to enhanced usual care control conditions among low-income pregnant women with discrepant results. Specifically, Grote et al. (2009) found that women who received enhanced brief IPT were significantly more likely to no longer meet criteria for depression based on the SCID at 3 months post baseline as compared to women in the enhanced usual care condition (i.e., 95% vs. 58%), whereas Lenze and Potts (2017) found that women in both enhanced brief IPT and enhanced usual care experienced significant decreases in depressive symptoms at post-treatment but were not significantly different from each other. Spinelli and Endicott (2003, 2013) completed two RCTs for English and Spanish speaking pregnant women whereby IPT was compared to a parent education program (i.e., education about pregnancy, labor, the postpartum period, and child development). Although their earlier pilot RCT (Spinelli & Endicott, 2003) found that women in the IPT group reported a significantly greater reduction in depressive symptoms as compared to women in the control group, their larger RCT (Spinelli et al., 2013) failed to find significant differences between the two conditions.

3.3.4. Other talk therapies

There has been 1 OT and four RCTs examining the effectiveness of other types of talk therapies (i.e., social problem solving, listening visits, supportive therapy, and psycho-education) for the treatment of perinatal depression. Field, Diego, Delgado, and Medina (2013) compared a nondirective peer support group therapy to an established treatment (i.e., group IPT) for pregnant women and found no significant group differences on depressive symptoms at post-treatment, suggesting a benefit of peer support. Alternatively, individual supportive therapy provided by a mental health nurse via home visits during the first 4 postpartum months did not provide any benefit over treatment as usual (Tamaki, 2008). Honey, Bennett, and Morgan (2002) examined a psycho-educational group therapy to routine primary care for postpartum women and found that women in the psycho-educational group reported a significantly greater decrease in depressive symptoms at post-treatment as compared to women in the routine primary care condition.

There have been two trials focused specifically on low income and/or minority pregnant women. An OT examining the influence of a motivational interviewing session followed by brief social problem solving skills therapy delivered at home by case workers for women enrolled in the Healthy Start program (i.e., a program that provides support for low-income pregnant women) found that women reported a significant reduction in depressive symptoms pre- to post-treatment (Sampson, Villarreal, & Rubin, 2016). In a similar RCT, Segre, Brock, and O’Hara (2015) compared listening visits (i.e., reflective listening and collaborative problem solving) provided by either a home visitor or an OBGYN to a wait list control condition and found that women in the listening visit condition reported a greater reduction in depressive symptoms on the HRSD (but not the self-reported EPDS) at post-treatment as compared to women in the wait list control condition.

3.3.5. Collaborative care models

Gjerdingen, Crow, McGovern, Miner, & Center (2009) evaluated a pilot stepped collaborative care intervention versus treatment as usual for postpartum women. The stepped collaborative care approach included a referral to their primary care physician for treatment with antidepressants and/or a referral to psychotherapy, every other week phone contact with a care manager, referral to a mental health provider for more severe cases, and psycho-education about postpartum depression for 9 months or until remission of symptoms. Although women in the stepped care group reported increased awareness of their depression and were more likely to receive treatment, they did not experience a significant difference in depressive symptoms as compared to women in the treatment as usual condition at the 9-month postpartum assessment. Grote et al. (2015) evaluated an 18-month collaborative care intervention (i.e., MOMCare) for low-income pregnant women delivered by depression care specialists in collaboration with OBGYN as compared to intensive maternity support services (i.e., parenting and nutrition classes, case management, referral to mental health treatment). MOMCare included all the same intensive maternity support services with the addition of: 1) a pre-treatment engagement session and 2) a choice of culturally relevant brief IPT, antidepressants, or both. Partial responders (i.e., < 50% improvement on the PHQ-9 at 6–8 weeks) could augment with the alternative treatment. Although women in both conditions improved significantly over time, women enrolled in the MOMCare intervention reported significantly lower depressive symptoms on average across the 18 months and were more likely to achieve remission from their depression (48% vs. 29%) as compared to women in the control condition.

3.3.6. Complementary and alternative medicine

3.3.6.1. Exercise.

There have been 4 RCTs examining the effectiveness of exercise for postpartum women. The exercise interventions, which ranged from 12 to 24 weeks, included group walking, individual walking, a whole body gentle stretching exercise program, and individualized exercise prescriptions based on reaching their target heart rate zone. Three of the trials found that women in the exercise condition reported a significantly greater decrease in depressive symptoms at post-treatment as compared to women in the control condition (Armstrong & Edwards, 2003; Daley et al., 2015; Heh, Huang, Ho, Fu, & Wang, 2008). Alternatively, DaCosta et al. (2009) found that only women with higher depressive symptoms at baseline (EPDS > 13) experienced a significant reduction in depressive symptoms at post-treatment as compared to women in the control condition.

3.3.6.2. Yoga.

There have been 2 OTs and 4 RCTs that have examined yoga during pregnancy (N = 5) and the postpartum (N = 1) period. All trials used group-based yoga and ranged from 9 to 24 sessions. The two OTs demonstrated promising results with women reporting significantly less depressive symptoms following the yoga intervention (Battle, Uebelacker, Magee, Sutton, & Miller, 2015; Muzik, Hamilton, Rosenblum, Waxler, & Hadi, 2012). Mitchell et al. (2012) compared prenatal yoga to an education control condition and found that women in the yoga condition experienced a significant decrease in depressive symptoms pre- to post-treatment, while women in the control condition did not experience a significant decrease in depressive symptoms. Another RCT, which compared gentle vinyasa flow yoga for postpartum women to a wait list control condition, found that although depressive symptoms decreased significantly in both groups, women in the yoga condition experienced a faster decline in symptoms as compared to women in the wait list control condition (Buttner, Brock, O’Hara, & Stuart, 2015). Alternatively, both Davis, Goodman, Leiferman, Taylor, and Dimidjian (2015) and Uebelacker, Battle, Sutton, Magee, and Miller (2016) found no significant differences in depressive symptoms at post-treatment between women in the yoga group and the control conditions.

3.3.6.3. Massage.

Field et al. (2008, 2009) examined the effect of prenatal massage, delivered by the women’s partner, as compared to treatment as usual in a pilot (N = 47) and larger (N = 149) RCT. In both studies women in the massage condition reported a significantly greater decrease in depressive symptoms at post-treatment as compared to women in the treatment as usual condition.

3.3.6.4. Acupuncture.

Manber, Schnyer, Allen, Rush, and Blasey (2004); Manber et al. (2010) examined the effect of acupuncture specific for depression (Schnyer et al., 2001) vs. acupuncture not specific to depression vs. prenatal massage in a small (N = 61) and larger (N = 150) RCT of pregnant women. The smaller trial revealed that women in the acupuncture for depression group were more likely to respond (i.e., not meeting full criteria for MDD based on the SCID, 50% reduction from baseline on the HRSD, and an HRSD score < 14) as compared to women in the massage group (68.8% vs. 31.6%) at 10 weeks postpartum, but there were no significant differences between the acupuncture specific to depression group vs. acupuncture not specific to depression group (Manber, Schnyder, Allen, Rush, & Blasey, 2004). Alternatively, the larger trial revealed that women in the acupuncture for depression group reported a significantly greater reduction of depressive symptoms and a larger treatment response (63% vs. 44%) as compared to both control conditions at post-treatment (Manber et al., 2010). Alternatively, in another small RCT (N = 20), which compared electroacupuncture to sham acupuncture (i.e., placebo needles) for postpartum women, there were no significant differences between treatment conditions at post-treatment (Chung et al., 2012).

3.3.6.5. Omega-3 fatty acids.

There have been 3 RCTs examining the effectiveness of omega-3 fatty acids for depression during the perinatal period. Freeman et al. (2008) compared weekly supportive therapy + omega-3 fatty acids to weekly supportive therapy + placebo for pregnant or postpartum women and found that women in both conditions reported a decrease in depressive symptoms pre- to post-treatment with no differences between treatment conditions. Another RCT, which compared omega-3 fatty acids to a placebo also failed to find significant differences in depressive symptoms at post-treatment between the two groups (Rees, Austin, & Parker, 2008). Only one RCT found that treatment with omega-3 fatty acids was superior to a placebo among pregnant women. Specifically, Su et al. (2008) found that women in the omega-3 fatty acids condition reported a significantly greater reduction in depressive symptoms at post-treatment and were more likely to have a treatment response (i.e., ≥ 50% reduction in symptoms on the HRSD) as compared to women in the placebo condition (62% vs. 27%).

3.3.7. Light therapy

One OT and 2 RCTs have examined the use of light therapy for treatment of depression during pregnancy. In a promising OT, Oren et al. (2002) found that approximately 50% of the sample achieved at least a 50% decrease in depressive symptoms pre- to post-treatment. In a small pilot RCT (N = 10), which compared bright light to dim light for 5 weeks, there were no statistically significant differences between treatment conditions (Epperson et al., 2004). Alternatively, Wirz-Justice et al. (2011) found that women who received light therapy for 5 weeks reported a significantly greater reduction in depressive symptoms and were more likely to achieve remission as compared to women who received red light placebo (i.e., 68.6% of women in the bright light group had an HRSD ≤8 as compared to 36.4% in the placebo group).

3.3.8. Brain stimulation

There have been two OTs using brain stimulation procedures for treatment of perinatal depression. Among pregnant women who received transcranial magnetic stimulation daily for 20 weeks, 7 out of 10 women experienced a ≥ 50% reduction of symptoms on the HRSD from pre- to post-treatment and 30% experienced remission of their MDD (Kim et al., 2011). Garcia, Flynn, Pierce, and Caudle (2010) provided repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation to postpartum women 5 times/week for 4 weeks and found that 8 out of 9 women achieved remission of their MDD (i.e., HRSD score < 10) at post-treatment.

3.3.9. Psychopharmacological interventions

There have been 4 OTs and 9 RCTs examining the use of psycho-pharmacological interventions for postpartum depression. The OTs examined the use of daily doses of escitalopram, buproprion SR, fluvoxamine, and venlafaxine and found significant improvement in depressive symptoms and high remission rates (Cohen et al., 2001; Misri, Abizadeh, Albert, Carter, & Ryan, 2012; Nonacs et al., 2005; Suri, Burt, Altshuler, Zuckerbrow-Miller, & Fairbanks, 2001). In an RCT comparing sertraline to a placebo, Hantsoo et al. (2014) found that women in the sertraline condition experienced a significantly higher remission rate (i.e., HRSD score ≤ 7 and ≥ 50% reduction in symptoms from pre- to post-treatment) as compared to women in the placebo condition (53% vs. 21%). In an RCT comparing paroxetine to placebo, there were no significant differences in depressive symptoms at post-treatment between conditions; however, women in the paroxetine condition experienced a significantly higher rate of remission (i.e., HRSD score ≤ 8) as compared to women in the placebo condition (37% vs. 15%; Yonkers, Lin, Howell, Heath, & Cohen, 2008). No significant differences in depressive symptoms, response rate, or remission rate were found in an RCT comparing nortriptyline to sertraline (Wisner et al., 2006), suggesting comparable benefit of these two psychotropic medications.

There have been a series of RCTs comparing a psychopharmacological intervention to a non-pharmacological intervention or a combination intervention. Kashani et al. (2016) compared fluoxetine to saffron and found no significant differences between conditions at posttreatment. Bloch et al. (2012) compared sertraline + brief dynamic psychotherapy vs. placebo + brief dynamic psychotherapy and found no significant differences between treatment groups. An RCT compared treatment with an antidepressant (most typically an SSRI) vs. listening visits (i.e., non-directive counseling) for 4 weeks with an opportunity to receive the alternative treatment after 4 weeks until 18 weeks. Women in the antidepressant group reported significant improvement (i.e., EPDS score < 13) as compared to women in the listening visit group at 4 weeks (45% vs. 20%), but this difference was statistically insignificant at the 18-week assessment (Sharp et al., 2010). Appleby, Warner, Whitton, and Faragher (1997) examined the effectiveness of 4 different intervention options: fluoxetine + 1 session of cognitive behavioral counseling, fluoxetine + 6 sessions of cognitive behavioral counseling, placebo + 1 session of cognitive behavioral counseling, and placebo + 6 sessions of cognitive behavioral counseling. They found that women in all treatment conditions reported a significant improvement in depressive symptoms. Fluoxetine was found to be significantly more effective than placebo, and 6 sessions of cognitive behavioral counseling was found to be significantly more effective than 1 session of cognitive behavioral counseling; however, there was no significant interaction between fluoxetine and counseling. A 12-week small RCT (N = 35), which compared paroxetine only vs. paroxetine + CBT, found no significant differences in depressive symptoms or time to recovery between the two conditions (Misri, Reebye, Corral, & Milis, 2004). Milgrom et al. (2015) examined the effectiveness of sertraline alone vs. CBT alone vs. both sertraline and CBT, and found that although women in all groups evidenced a significant decrease in depressive symptoms, women in the CBT only group evidenced the greatest improvement as compared to women in the sertraline alone or combination groups.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of non-pharmacological interventions

This review identified a total of 65 non-pharmacological treatment studies for the treatment of depression, anxiety, and trauma-related disorders during the perinatal period. Preliminary OT studies, which examined treatments for perinatal anxiety, suggest a potential benefit of CBT interventions. The sole RCT focused on treatment of trauma-related disorders provides support for the effectiveness of a trauma-focused intervention delivered in the NICU among women who delivered a premature infant on reduction of depressive and PTSD symptoms (Shaw, St. John, et al., 2013).

There was a wide range of interventions studied for the treatment of perinatal depression. RCTs, which examined the effectiveness of CBT or IPT without a specific focus on treatment of low-income and/or minority women, demonstrated a significant benefit of CBT or IPT over the control condition regardless of modality (i.e., in-person, online, telephone) and duration (i.e., 6–12 sessions). IPT focuses on interpersonal issues, particularly role transitions, with the goal of improving interpersonal relationship functioning and increasing social support. Alternatively, the main components of CBT include behavioral activation and cognitive restructuring. The perinatal period is associated with a range of psychosocial changes, including sleep deprivation, time and financial constraints, and significant role transitions and changes to interpersonal relationships. It’s possible that the focus on interpersonal relationships and social support within the context of IPT may be especially beneficial for this population. To this end, an earlier meta-analysis on treatments for perinatal depression found that IPT was superior to CBT in the treatment of perinatal depression (Sockol, Epperson, & Barber, 2011). However, further research on this is needed given vast methodological variation between studies.

Trials examining physician delivered perinatal depression management (i.e., assessment, support, CBT strategies) as compared to an active psychosocial treatment by a psychologist, or postnatal nurse, or standard prenatal care revealed conflicting findings. However, these were small trials (Ns: 42–68). There is some evidence for the effectiveness of group peer support or psychoeducation; however, individual supportive therapy did not fare better than treatment as usual. A pilot stepped collaborative care intervention for postpartum women did not impact depressive symptoms at post-treatment; however, awareness of depression and receipt of treatment was higher among women in the intervention condition as compared to women in the control condition (Gjerdingen et al., 2009). It is possible that this study was underpowered (N = 34) and future research on stepped care models is important in order to improve efficiency of treatment.

Other non-pharmacological interventions such as complementary and alternative medicine approaches, light therapy, and brain stimulation for the treatment of perinatal depression, have seen an emergence of research. Four exercise-related RCTs suggest there is benefit in the use of exercise for the treatment of postpartum depression. Alternatively, treatment of perinatal depression using yoga has revealed mixed findings. Two RCTs found that yoga was associated with a decrease in depressive symptoms as compared to the control condition, while two other RCTs found no differences in depressive symptoms between yoga and control conditions. Prenatal massage conducted by the women’s partner was found to be superior to treatment as usual at decreasing depressive symptoms; however, this is based on only two trials. There is limited evidence for the effectiveness of acupuncture, omega-3 fatty acids, and light therapy for the treatment of perinatal depression. However, there were only a few trials within each of these intervention categories. Brain stimulation holds promise based on 2 OT studies, but further research is needed using control conditions.

4.2. Summary of psychopharmacological interventions

This review identified a total of 13 psychopharmacological intervention studies for the treatment of postpartum depression. Four OT studies examining escitalopram, bupropion, fluvoxamine, and venlafaxine found that a large proportion of the sample achieved remission. However, small sample sizes and lack of control groups indicate the need for more rigorous research of these interventions. Two RCTs compared an SSRI (i.e., sertraline, paroxetine) directly to a placebo group and found significant benefit in depression remission. The remaining RCTs reviewed (N = 7) compared an SSRI to another active treatment condition (i.e., saffron, a tricyclic antidepressant, CBT, brief dynamic psychotherapy, non-directive counseling) alone or in combination. In 6 out of 7 trials, there was no significant difference between the SSRI and the active treatment condition, suggesting equal benefit of other non-pharmacological treatments. In fact, one trial found that CBT alone was associated with superior improvement on depression remission rates as compared to sertraline alone or sertraline in combination with CBT (Milgrom et al., 2015). However, research in the area of the effectiveness of psychopharmacological interventions for treatment of perinatal psychiatric disorders is sparse and it is difficult to draw definite conclusions from the limited amount of studies available. While psychotherapy is an adequate treatment for some depressed women during pregnancy, others may prefer or require pharmacotherapy (Yonkers et al., 2009). Additionally, in low resourced communities there may not be any psychiatrists or therapists trained in evidence-based non-pharmacological treatments. In these situations, perinatal mental health conditions are managed primarily by a primary care or OBGYN physician. Therefore, it is imperative to study the effectiveness of psychotropic medication, particularly in underserved perinatal populations, to inform treatment decisions.

4.3. Summary of interventions for low-income and/or minority populations

Only CBT and IPT have been examined specifically for low-income and/or minority women with mixed results. One trial, which examined a modified CBT intervention for low-income pregnant women, revealed a positive influence on depressive symptoms as compared to treatment as usual, while another CBT intervention adapted for a diverse group of racial and ethnic women only exhibited significant positive effects on depressive symptoms for African American women in the trial. A cluster RCT in rural Pakistan, a low-income and low-resourced setting, found that a CBT program delivered by community health workers was superior to enhanced usual care at reducing depressive symptoms. Although preliminary RCTs examining culturally relevant enhanced brief IPT to enhanced usual care for low-income pregnant women, and IPT for English and Spanish speaking pregnant women to a parent education program revealed promising effects on depressive symptoms, these effects were not seen in larger replication RCTs with these two treatments. Differences in level of therapy engagement (Grote et al., 2009; Lenze & Potts, 2017) and racial makeup of the study population (Spinelli et al., 2013; Spinelli & Endicott, 2003) may have contributed to these differences. A reflective listening and collaborative problem solving intervention delivered by either a home visitor or an OBGYN for low-income pregnant women demonstrated better depression outcomes than women in a wait list control group. Finally, a culturally relevant collaborative care intervention for low-income pregnant women outperformed an intensive maternity support condition.

The emergence of trials focused on this population is exciting. Low-income women and women of ethnic or racial minority status are much more likely to be diagnosed with depression during the perinatal period (Hobfoll et al., 1995), yet they are less likely to receive adequate care (HHS, 2001) and are more likely to dropout of treatment (Arnow et al., 2007). Reasons for this are likely multifaceted and include barriers such as lack of money, childcare, transportation, mental health related stigma, and concerns that the therapist may not understand them (Alvidrez & Azocar, 1999; Poleshuck, Cerrito, Leshoure, Finocan-Kaag, & Kearney, 2013). For example, one study found that pregnant African American women were less likely to view counseling as an acceptable treatment for depression as compared to pregnant white women (Sleath et al., 2005). Studies reviewed modified treatment for this population in multiple ways, including addition of a pre-treatment engagement session, consideration of culture in treatment, reduction of practical barriers such as childcare and transportation costs, case management, flexibility of treatment modality (e.g., on the phone, within the OBGYN clinic), and engagement and integration with OBGYN. Further research aimed at engaging this population in treatment is needed.

4.4. Limitations of reviewed studies

The current review aims to extend the existing literature by being more inclusive with regards to the psychiatric disorders examined, the study populations that were targeted, the treatments that were tested, and the methodology that was used. Due to this, there was variability in the interventions reviewed. For example, 64% of the included studies recruited individuals with a diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder using DSM criteria, while 36% recruited individuals based on elevated psychiatric symptoms, most commonly via the HRSD or the EPDS, using a predetermined cut-off score. Cut-off scores used on measures to identify individuals with elevated psychiatric symptoms varied across studies. Therefore, variability in symptom severity at treatment start may have influenced treatment response. Additionally, OTs with no control condition were included in this review to provide clinical information regarding potential innovative treatments for this population. However, time was a strong effect of treatment response across all studies reviewed with individuals in all treatment conditions improving over time; therefore, OTs must be interpreted with caution, and further research, which compares an active treatment to a control condition, are needed. CBT and IPT were the most extensively studied interventions for perinatal depression, anxiety, and trauma-related disorders. However, these interventions included various modifications across studies, which is a potential threat to interpretation of study findings. Despite this variability, most of these studies found a positive benefit of these interventions over control conditions. Many of the reviewed studies did not include long-term follow-up assessments, which limits the ability to assess the long-term efficacy of these interventions. However, among RCTs, which included long-term follow-up data, the results are generally promising for some of the non-pharmacological interventions. Specifically, CBT, IPT, and psychoeducation interventions found lasting beneficial effects of the intervention as compared to the control condition at 3- and 6-month follow-up assessments. Alternatively, the long-term benefits of exercise were mixed. The data on long-term outcomes of psychopharmacological interventions is scarce. Given the impact of perinatal mental health problems on the developing fetus, infant, and child (Beijers, Jansen, Riksen-Walraven, & de Weerth, 2010; Grace et al., 2003; Grote et al., 2010), understanding the long-term benefits of these interventions is important. Of note, research suggests that poor maternal mental health during pregnancy affects fetal neurodevelopment and subsequently increases the risk for future child psychopathology (Suarez et al., 2018), while positive maternal mental health during pregnancy has long-term positive effects on child outcomes, particularly cognitive and language competencies (Phua, Kee, Koh, & Rifkin-Graboi, 2017). These studies suggest that treatment during the perinatal period may have long lasting positive effects on child outcomes. Finally, in contrast to the myriad of studies examining the influence of psychopharmacological treatment on newborn outcomes, there were a limited number of effectiveness trials on psychopharmacological treatments in the perinatal period (and none for the treatment of anxiety and trauma-related disorders). The concern regarding potential fetal and neonatal adverse effects of psychotropic medication has likely slowed progress in this area, making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions regarding the effectiveness of psycho-pharmacological treatments for this population.

4.5. Gaps in the literature and future directions

Of the 78 studies reviewed, only 5 focused on anxiety and/or trauma-related disorders with most of these studies utilizing an OT design. There is clearly an overwhelming need to conduct more research on treatment of anxiety and trauma-related disorders, particularly given that that the prevalence of these disorders is high in the perinatal period (Seng, 2009; Vesga-López et al., 2008). Additionally, emerging evidence suggests that women with perinatal anxiety and trauma-related disorders are at risk for similar negative outcomes as individuals with perinatal depression (Yonkers et al., 2014).

Even though there is a large literature demonstrating the efficacy of a variety of treatments for perinatal depression, a substantial number of women (up to 86%) do not receive psychiatric treatment at all during the perinatal period despite clinical symptom levels (Cox, Sowa, Meltzer-Brody, & Gaynes, 2016; Marcus, Flynn, Blow, & Barry, 2003). Of those that receive treatment, very few receive adequate treatment and/or achieve clinical remission (Cox et al., 2016). This is likely due to a variety of factors, including: a) a preference to receive care embedded in their outpatient OB clinic or through home visits, b) a preference for psychiatry or therapy appointments to be scheduled adjacent to their OB appointments and to be actively assisted in accessing care, c) lack of knowledge about psychiatric disorders and their treatment, d) mental health treatment stigma, e) low acceptability of psychotropic medication during the perinatal period, and f) lack of time and/or childcare (Dennis & Chung-Lee, 2006; Flynn, Henshaw, O’Mahen, & Forman, 2010; Kopelman et al., 2008; Sword, Busser, Gannon, McMillan, & Swinton, 2008). Addressing these barriers and increasing access to effective mental health treatment for women in the perinatal period is critical. One promising direction is the use of alternative treatment modalities. For example, using web-or telephone-based modalities may be particularly useful for this population and reach a greater proportion of women in need. The web- and telephone-based interventions included in this review show promising results as compared to wait list control and treatment as usual conditions. Determining the effectiveness of these modalities in comparison to in-person therapy would be an important next step. Another promising avenue for future research is the delivery of mental health interventions by non-mental health specialists. This review revealed initial evidence that CBT and IPT can be effectively delivered by non-mental health providers (e.g., nurses; Milgrom et al., 2011; Posmontier et al., 2016; Rahman et al., 2008). Given the scarcity of trained mental health specialists in rural and low-income settings, training non-mental health providers in effective perinatal mental health treatments would be a significant step towards increasing access to care for these populations. Finally, assessment of psychiatric symptoms and subsequent treatment within the OB clinic may also help women overcome some of the aforementioned barriers.

This review also highlights the scarcity of psychopharmacological treatment studies for this population, particularly during pregnancy. In contrast, there is a large literature examining the effects of psychotropic medication on infant outcomes. For example, some studies link maternal selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) use to infant major congenital malformations (Berard, Zhao, & Sheehy, 2017; Cole, Ephross, Cosmatos, & Walker, 2007; Källén & Olausson, 2007; Reefhuis, Devine, Friedman, Louik, & Honein, 2015). This is in contrast to studies with reassuring outcomes (Petersen, Evans, Gilbert, Marston, & Nazareth, 2016) and those highlighting the importance of maternal and newborn genetic variants as possible risk mediators (Nembhard et al., 2017). Moreover, other factors such as diabetes or substance abuse have been shown to be much stronger predictors of major congenital malformation than antidepressant use (Petersen et al., 2016). Psychotropic medication use has also been associated with adverse effects on the mother. The risk of preeclampsia and gestational hypertension was shown to be elevated among women who used serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) and TCAs (De Ocampo et al., 2016; Palmsten, Setoguchi, Margulis, Patrick, & Hernandez-Diaz, 2012), while SSRI exposure effects were modest, in particular after adjusting for the severity of maternal depression. Additionally, diabetes and obesity are well known preeclampsia risk factors (Duckitt & Harrington, 2005). Finally, it is often difficult to disentangle the effects of psychiatric symptoms and/or medication exposures on maternal and newborn outcomes due to ethical considerations regarding optimal control group choice (i.e. healthy moms and/or depressed moms without treatment access; Andrade, 2017). Equally challenging is the attempt to differentiate between the effects of maternal mood and/or medication exposure on the developing fetus and shared genetic neurodevelopmental risks (Oberlander & Zwaigenbaum, 2017). Therefore, the decision on whether to use medications during the perinatal period is a highly complex process that must take into account a variety of factors and potential consequences, as well as the individual circumstances of every patient, particularly given evidence documenting the detrimental effects of untreated psychiatric illness on both maternal and infant outcomes (Gentile, 2017; Jarde, Morais, & Kingston, 2016; Marcus, 2009). Although a substantial percentage of women choose to discontinue psychotropic medications during the perinatal period for fear of causing teratogenic effects, many do not. Discontinuation of antidepressant medications in pregnancy, particularly in the absence of alternative treatment, increases health care costs, as a consequence of maternal and newborn outcomes (O’Brien, Laporte, & Koren, 2009). Strikingly, lifetime cost associated with perinatal depression and anxiety are estimated at £75,728 and £34,811, respectively per affected woman (Bauer, Knapp, & Parsonage, 2016). In conclusion, perinatal psychiatric disorders have well documented effects on maternal and newborn clinical and health care costs outcomes, indicating need for designing RCT studies which take into account perinatal clinical phenotypes (Putnam et al., 2017) as well as potential genetic and epigenetic biomarkers (Brunst et al., 2017).

Despite the limited effectiveness research in this area, the use of psychotropic medications during pregnancy in the United States has increased rapidly in the past decade (Alexander, Gallagher, Mascola, Moloney, & Stafford, 2011), with SSRIs accounting for the majority of this increase (Andrade et al., 2008). See Table 2 for a summary of psychotropic medication typically used to treat depression, anxiety, and trauma-related disorders in the perinatal period. Specifically, sertraline and fluoxetine were among the most commonly prescribed SSRIs, while bupropion was the most commonly prescribed non-SSRI antidepressant (Alwan, Reefhuis, Rasmussen, & Friedman, 2011). Anxiolytics and sedative-hypnotics together have been found to be the most common class of drugs used by pregnant women (Leong et al., 2017) with diazepam being the most commonly used anxiolytic in pregnancy (Leppee, Culig, Eric, Sijanovic, 2010). For treatment resistant depression, second generation antipsychotics and mood stabilizers have been used as augmenting agents or as a replacement to typical agents such as anti-depressants. To this end, the use of antipsychotics, particularly second generation antipsychotics, during the perinatal period has increased dramatically both in the United States and worldwide, potentially due to the expansion of such off label uses (Park et al., 2017).

Table 2.

Classes of psychotropic medications used in the treatment of depression, anxiety, and trauma-related disorders.

| Antidepressants (SSRIs)-used in treatment of depression, anxiety, PTSD |

SSRIs: Paroxetine, fluoxetine, citalopram, sertraline, escitalopram, fluvoxamine SNRIs: desvenlafaxine, duloxetine, levomilnacipran, venlafaxine Dopamine Reuptake Inhibitors: Buproprion Tricyclic Antidepressants: amitriptyline, amoxapine, clomipramine, desipramine, doxepin, imipramine, nortriptyline, protriptyline, trimipramine. |

| Second Generation Antipsychotics (SGAs)-used in treatment-resistant | Risperidone, quetiapine, olanzapine, lurasidone, aripiprazole |

| depression and/or as augmenting agents | |

| Mood Stabilizers-used in treatment resistant depression and/or as augmenting agents | Lithium, lamotrigine |

| Anxiolytics (benzodiazepines) -used in anxiety and panic disorder | Alprazolam, bromazepam, chlordiazepoxide, clonazepam, clorazepate, diazepam, flurazepam, lorazepam, oxazepam, temazepam, triazolam |

Psychotropic medication use in these population-based prevalence studies varies based on demographic factors. Specifically, low-income women have been found to be more likely to use anxiolytics and sedative-hypnotics in pregnancy (Ban, Tata, West, Fiaschi, & Gibson, 2012). However, prevalence of antidepressant use is higher among older, educated, white women (Cooper, Willy, Pont, & Ray, 2007; Yamamoto, McCormick, & Burris, 2015). There may be various reasons why psychopharmacological use patterns differ among these subgroups. It is possible that higher education, higher socioeconomic status (SES), and/or increased social support could help bypass typical barriers to care. Low SES is, indeed, associated with poorer access to depression care (Lorant et al., 2003), as well as being less likely to seek or remain in treatment for depression (Grote, Zuckoff, Swartz, Beldsoe, & Geibel, 2007). Therefore, low-income perinatal women are less likely to receive specialized care and are instead treated by their OB and/or primary care providers, who may not be comfortable prescribing anti-depressants to their perinatal patients. Consequently, it is not surprising that low-income perinatal women tend to use more anxiolytics and sedatives as these medications may be more likely to be prescribed by OB and primary care providers for symptom management (e.g., sleep, anxiety). Given research that low-income and minority women are more likely to adhere to a course of psychopharmacological treatment than to a non-pharmacological intervention such as CBT (Miranda et al., 2003), understanding the effectiveness of psychotropic with this population specifically is important.

Studies reviewed included interventions conducted during pregnancy as well as interventions conducted during the postpartum period. It’s possible that adherence to these interventions may be impacted by unique barriers depending on whether women receive them during pregnancy vs. the postpartum period. For example, during pregnancy women have many appointments related to their prenatal care, which may influence how much additional time they have to devote to therapy. During the postpartum period, however, increased stressors such as sleep deprivation, time constraints, and financial constraints may also impact adherence to treatment. There is no current evidence that there is a differential treatment response during pregnancy vs. the postpartum period. Further research on the most effective time to intervene during the perinatal period is needed.

5. Conclusions

In summary, the majority of research for treatment of perinatal psychiatric disorders has focused on perinatal depression, and there is almost no knowledge on effective treatments for perinatal anxiety and trauma-related disorders. For perinatal depression, CBT, followed by IPT, are the most studied treatments and both have achieved a strong evidence base among this population. Other non-pharmacological interventions such as exercise, yoga, and prenatal massage have show some preliminary efficacy, but more and larger studies are needed. There is a paucity of effectiveness research on psychopharmacological interventions, particularly in the face of the increased prevalence of psychotropic medication use during the perinatal period. Finally, although interventions specifically for low-income and/or minority perinatal populations are emerging in the literature, more research on this vulnerable and difficult to engage population is needed.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Perinatal psychiatric disorders are associated with adverse outcomes.

78 studies for depression, anxiety, and trauma-related disorders are reviewed.

There is strong support for the use of CBT and IPT for perinatal depression.

Treatment studies for perinatal anxiety and trauma-related disorders are limited.

Psychopharmacological effectiveness trials are limited despite their increased use.

Acknowledgments

Role of funding sources

Funding for this study was provided by NICHD Grant 1K23HD087428–01A1 awarded to Yael Nillni and funding from the Department of Psychiatry at Boston University School of Medicine awarded to Snezana Milanovic. NICHD and Boston University School of Medicine had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Biography

Yael I. Nillni, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at Boston University School of Medicine and a Clinical Research Psychologist in the National Center for PTSD, Women’s Health Sciences Division at VA Boston Healthcare System. Her research focuses on the intersection between mental health and reproductive health with the ultimate goal of improving intervention efforts for women. For example, her research has aimed to identify psychological and neurobiological factors involved in the onset and maintenance of physical and mental health problems during reproductive transitions (e.g., menstrual cycle, pregnancy, postpartum), as well as to identify sex-specific mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder.

Aydan Mehralizade, MPH, is a graduate of Boston University School of Public Health. She is currently a senior Clinical Research Coordinator at the Institute for Genomic Medicine, Columbia University Medical Center.

Laura Mayer, M.D. is the Chief Resident at the Psychiatry Residency Program at Boston University Medical Center, and she will be completing a Women’s Mental Health fellowship at Brown University in the upcoming year. Her area of interest is in mental health during the perinatal period.

Snezana Milanovic, M.D., is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at Boston University School of Medicine and Director of the Mother-Child Wellness Clinical and Research Center. Her translational research focuses on perinatal psychiatry: effects of environmental stressors on fetal brain development, phenotypes in high-risk mothers and newborns and associated predictive biomarkers.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2018.06.004.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alder J, Fink N, Bitzer J, Hosli I, & Holzgreve W (2007). Depression and anxiety during pregnancy: A risk factor for obstetric, fetal and neonatal outcome? A critical review of the literature. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine, 20(3), 189–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GC, Gallagher SA, Mascola A, Moloney RM, & Stafford RS (2011). Increasing off-label use of antipsychotic medications in the United States, 1995–2008. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 20, 177–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvidrez J, & Azocar F (1999). Distressed women’s clinic patients: Preferences for mental health treatments and perceived obstacles. General Hospital Psychiatry, 21, 340–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alwan S, Reefhuis J, Rasmussen SA, & Friedman JM (2011). Patterns of anti-depressant medication use among pregnant women in a United States population. The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 51(2), 264–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade C (2017). Offspring outcomes in studies of antidepressant-treated pregnancies depend on the choice of control group. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 78(3), e294–e297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade SE, Raebel MA, Brown J, Lane K, Livingston J, Boudreau D, ... Platt R. (2008). Use of antidepressant medications during pregnancy: A multisite study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 198(2), 194.e191–194.e195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appleby L, Warner R, Whitton A, & Faragher B (1997). A controlled study of fluoxetine and cognitive-behavioural counselling in the treatment of postnatal depression. BMJ, 314, 932–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong K, & Edwards H (2003). The effects of exercise and social support on mothers reporting depressive symptoms: A pilot randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 12(2), 130–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnow BA, Blasey C, Manber R, Constantino MJ, Markowitz JC, Klein DN, ... Rush AJ (2007). Dropouts versus completers among chronically depressed outpatients. Journal of Affective Disorders, 97, 197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ban L, Tata LJ, West J, Fiaschi L, & Gibson JE (2012). Live and non-live pregnancy outcomes among women with depression and anxiety: A population-based study. PLoS One, 7(8), 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battle CL, Uebelacker LA, Magee SR, Sutton KA, & Miller IW (2015). Potential for prenatal yoga to serve as an intervention to treat depression during pregnancy. Women’s Health Issues, 25(2), 134–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer A, Knapp M, & Parsonage M (2016). Lifetime costs of perinatal anxiety and depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 192, 83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beijers R, Jansen J, Riksen-Walraven M, & de Weerth C (2010). Maternal prenatal anxiety and stress predict infant illnesses and health complaints. Pediatrics, 126(2), 401–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berard A, Zhao JP, & Sheehy O (2017). Antidepressant use during pregnancy and the risk of major congenital malformations in a cohort of depressed pregnant women: An updated analysis of the Quebec Pregnancy Cohort. BMJ Open, 7(1), 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch M, Meiboom H, Lorberblatt M, Bluvstein I, Aharonov I, & Schreiber S (2012). The effect of sertraline add-on to brief dynamic psychotherapy for the treatment of postpartum depression: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 73(2), 235–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon AR, Ceccotti N, Hynan LS, Shivakumar G, Johnson N, & Jarrett RB (2012) Proof of concept: Partner-Assisted Interpersonal Psychotherapy for perinatal depression. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 15, 469–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunst KJ, Guerra MS, Gennings C, Hacker M, Jara C, Enlow MB, ... Wright RJ (2017). Maternal lifetime stress and prenatal psychological functioning are associated with decreased placental mitochondrial DNA copy number in the PRISM study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 186(11), 1227–1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns A, O’Mahen H, Baxter H, Bennert K, Wiles N, Ramchandani P, ... Evans J (2013) A pilot randomised controlled trial of cognitive behavioural therapy for antenatal depression. BMC Psychiatry, 13(33), 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttner MM, Brock RL, O’Hara MW, & Stuart S (2015). Efficacy of yoga for depressed postpartum women: A randomized controlled trial. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 21, 94–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho HJ, Kwon JH, & Lee JJ (2008). Antenatal cognitive-behavioral therapy for prevention of postpartum depression: A pilot study. Yonsei Medical Journal, 49(4), 553–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung TKH, Lau TK, Yip ASK, Chiu HFK, & Lee DTS (2001). Antepartum depressive symptomatology is associated with adverse obstetric and neonatal outcomes. Psychosomatic Medicine, 63(5), 830–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung KF, Yeung WF, Zhang ZJ, Yung KP, Man SC, Lee CP, ... Wong VT (2012) . Randomized non-invasive sham-controlled pilot trial of electroacupuncture for postpartum depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 142, 115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LS, Altshuler LL, Harlow BL, Nonacs R, Newport DJ, Viguera AC, ... Stowe ZN (2006). Relapse of major depression during pregnancy in women who maintain or discontinue antidepressant treatment. Journal of the American Medical Association, 295(5), 499–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LS, Viguera AC, Bouffard SM, Nonacs RM, Morabito C, Collins MH, & Ablon JS (2001). Venlafaxine in the treatment of postpartum depression. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 62(8), 592–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole JA, Ephross SA, Cosmatos IS, & Walker AM (2007). Paroxetine in the first trimester and the prevalence of congenital malformations. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 16, 1075–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]