Abstract

Background

Several candidate genes and genome wide association studies have reported significant associations between vitamin D metabolism genes and 25-hydroxyvitamin D. Few studies have examined these relationships in pregnancy.

Objective

We evaluated the relationship between maternal allelic variants in three vitamin D metabolism genes and 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) concentration in pregnancy.

Study design

In two case-control studies, samples were drawn from women who delivered at Magee Womens Hospital in Pittsburgh, PA from 1999 to 2010 and twelve recruiting sites across the United States from 1959 to 65. For 882 Black and 1796 White pregnant women from these studies, 25(OH)D concentration was measured and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were genotyped 50 kilobases up- and down-stream in three genes (VDR, GC, and CYP27B1). Using multivariable linear regression, we estimated the associations between allelic variation of each locus and log-transformed 25(OH)D concentration separately by race and study group. Meta-analysis was used to estimate the association across the four groups for each SNP.

Results

Minor alleles of several variants in VDR, GC, and CYP27B1 were associated with differences in log-transformed 25(OH)D concentration compared to the corresponding major alleles [beta, 95% confidence intervals (CI)]. The meta-analysis confirmed the associations for differences in log-transformed 25(OH)D by allelic loci for one intron VDR variant [rs2853559 0.08 (0.02, 0.13), p < 0.01] and a variant in the GC flanking region [rs13150174: 0.04 (0.02, 0.07), p < 0.01], and a GC missense mutation [rs7041 0.05 (0.01, 0.09), p < 0.01]. The meta-analysis also revealed possible associations for SNPs in linkage disequilibrium with variants in the VDR 3-prime untranslated region, another GC missense variant (rs4588), and a variant of the 3-prime untranslated region of CYP27B1.

Conclusion

We observed associations between VDR, GC, and CYP27B1 variants and maternal 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration. Our results provide additional support for a possible role of genetic variation in vitamin D metabolism genes on vitamin D status during pregnancy.

Keywords: Vitamin D deficiency, 25-Hydroxy vitamin d, Vitamin d metabolic loci, Vitamin D binding protein gene, Vitamin D receptor gene, 1 alpha-hydroxylase gene, Genetic variation, Vitamin D, VDR, CYP27B1, GC

Introduction

One in four pregnant women in the U.S. has suboptimal vitamin D status [1–3], as defined by serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH) D) concentrations <50 nmol/L [4]. Non-Hispanic Black women are 3–5 times as likely as non-Hispanic White women to be deficient in vitamin [5,6]. The widespread deficiency and racial/ethnic gap in its prevalence is concerning because of the associations between low 25(OH)D and the increase risk of offspring rickets [7], preterm birth [8], preeclampsia [9], small-for-gestational age birth [10], childhood asthma [11], and type 1 diabetes mellitus [12]. Therefore, understanding factors that influence vitamin D status is of clinical and public health importance.

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in several genes in the vitamin D metabolic pathway contribute to circulating 25(OH)D concentration [13]. These genes include the vitamin D binding (GC), cytochrome p450 27B1 (CYP27B1), and the vitamin D receptor genes (VDR). While there have been many studies exploring the contribution of genetic variation in these genes to vitamin D status among non-pregnant adults [13–15], there is a paucity of data among pregnant women and particularly among racially/ethnically diverse women.

Pregnancy is accompanied by important alterations in vitamin D metabolism, including increasing circulation of DBP [16], enhanced hydroxylation of 25(OH)D to 1,25(OH)2D in kidneys and other cells and organs [17], and transportation of 25(OH)D into the placenta [18]. Therefore, determining whether genetic variation of key vitamin D metabolism genes is associated with 25(OH) D concentration in pregnancy is important. Thus, our objective was to evaluate the relationship between common SNPs in the GC, CYP27B1, and VDR genes and maternal serum 25(OH)D concentrations in two large pregnancy study groups of Black and White mothers.

Materials and methods

For this study, we used data and stored samples from two pregnancy case-control studies on vitamin D and adverse birth outcomes: Epidemiology of Vitamin D Study (EVITA) and Collaborative Perinatal Project (CPP). Both studies were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. Both studies have been described in detail elsewhere [19,20]. In brief, eligibility criteria for EVITA included singleton pregnancies with an available banked serum sample from aneuploidy screening at ≤20 weeks at the hospital’s Center for Medical Genetics and Genomics, and delivered at Magee-Womens Hospital of University of Pittsburgh Medical Center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (total of 12,861 eligible pregnancies). We selected a randomly-sampled set of controls of 2327 eligible women for 25(OH)D assessment in the case-control study, and from this group all term pregnancies without preeclampsia of non-Hispanic White (n = 1394) and non-Hispanic Black (n = 353) women were used in the current analysis.

In CPP, more than 55,000 women at 12 U.S medical centers in 1959–65 were enrolled. The cohort of eligible women for the parent study included women with singleton pregnancies, no preexisting conditions (pregestational diabetes, hypertension, or cardiovascular disease), and a banked serum sample at <26 week (n = 28,429). We then randomly selected a subcohort of 2986 eligible women. From this group, we selected 1076 White and 882 Black women with non-preeclamptic term deliveries for serum 25(OH)D assay. In both studies, racial/ethnic groups other than White and Black were excluded from genotyping because of small samples.

Maternal serum samples in CPP were collected at ≤26 weeks of gestation and stored for 40 years at −20 °C with no recorded thaws. EVITA samples were collected at ≤20 weeks of gestation and were stored at −80 °C for 2–12 years. 25(OH)D has been proven to be highly stable. No loss of 25(OH)D has been noted after leaving uncentrifuged blood up to 72 h at 24 °C, after storage of serum for years at 20 °C, after exposure to ultraviolet light, or after up to 11 freeze-thaw cycles [21]. A pilot study in the CPP samples compared 25(OH)D in these serum with serum frozen for ≤2 years and found that 25(OH)D is unlikely to show significant degradation [22].

Sera from both study groups were sent to the same Vitamin D External Quality Assessment Scheme certified laboratory. Samples were assayed for total 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) [25(OH) D2 + 25(OH)D3] using liquid-chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry based on National Institute of Standards and Technology standards [23]. Intra- and the inter-assay variations were ≤9.6% and ≤10.9%, respectively. Vitamin D deficiency was defined as 25 (OH)D <50 nmol/L.

Using the International HapMap database (Phase 3) [24], tagging SNPs with minor allele frequency of 10% or more were identified for a region spanning 50 kilobases up- and downstream of each candidate gene. The tagging SNPs were selected based on a reference population of the HapMap “Utah residents with Northern and Western European ancestry” (CEU), and then supplemented with additional SNPs from the HapMap “Americans of African Ancestry in Southwest USA” (ASW) population to adequately capture variation across the candidate genes within our diverse study samples. In total, 499 SNPs were selected: 39 for CYP27B1, 126 for GC, 206 for VDR. We also genotyped 128 ancestry informative markers (AIMs) in both Black and White women, which is a validated set of markers to identify common populations in America that can be determined using analysis in STRUCTURE 2.3.4 (Stanford, CA) [25–29].

Serum was thawed, and potential contaminants and inhibitors were removed using Qiagen kits (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). The resulting serum product was whole genome amplified using REPLi-g midi kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). The QuantStudio 12 K Flex platform (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) was used to genotype the selected SNPs. Genotypes were called using the TaqMan Genotyper software (Version 1.3.1, Grand Island, NY) and visual assessment of the data was used for confirmation.

Potential confounding variables came from the perinatal database in EVITA and in-person interviews for CPP. Both studies included data on pre-pregnancy body mass index (<18.5, 18.5–24.9, 25–29.9, ≥30), preexisting diabetes (yes, no), maternal education (<12 years, 12 years, and >12 years), marital status (single, married), maternal age (<20, 20–29, ≥30), parity, and season of blood draw (winter (December–February), spring (March–May), summer (June–August), or fall (September–November)). Season of sampling was considered a potential confounder due to the seasonal effects of UVB radiation on the vitamin D endocrine system [30]. Gestational age was based on best obstetric estimate comparing menstrual dating and ultrasound estimates in EVITA and on the mother’s report of the first day of her last menstrual period in CPP since ultrasound was not available in the 1960s. Data on provider type were available for women in EVITA. A composite socioeconomic status score was available for CPP, which combines education, occupation, and family income data [31].

Statistics

To minimize confounding due to population substructure, genetic ancestry and self-reported race were used to categorize mothers as Black or White [29]. First, individual ancestral proportions were calculated using an analysis of AIMs in STRUCTURE 2.3.4 (Stanford, CA) [25–28]. An ad hoc statistic based on the rate change in the log probability of data between clusters was used to identify two subgroups in each study [32]. Individuals who self-identified as White but had a >50% probability of belonging to ASW were reassigned to Black race. However, all self-reported Black mothers were assigned to Black race unless they had a 100% probability of being CEU.

Data-quality control steps were performed using PLINK software (Version 1.07; Boston, MA) [33,34]. Samples and markers with call rates <80% were omitted from further analyses. All SNPs included in the analysis had a call rate >80%, minor allele frequency >0.05 and were in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (P > 0.00001) (Supplementary Fig. 1). For SNPs that passed quality control, a test of variance was conducted to determine if genotype missingness was significantly different among the four study groups (White mothers in EVITA, Black mothers in EVITA, White mothers in CPP, White mothers in CPP) or by race, study, or chromosome.

Analyses were completed separately by study (CPP and EVITA) and race/ethnicity (Black or White) groups. For each race-study group, we calculated the geometric mean of 25(OH)D (nmol/L) by allele and tested for differences using nonparametric trend tests. Associations between minor allele and log-transformed 25(OH)D concentration (to reduce skewness of the data which resulted in normally distributed residuals) were further examined in univariable and multivariable linear regression models. We first modeled functional SNPs in parsimonious models by removing potential confounders from the model if their exclusion did not change the main exposure point estimate by ≥10%. Using these methods, we adjusted for batch number (in EVITA only), year drawn (in EVITA only), site (CPP), season of blood draw, sample age, and maternal age. All models for Black mothers were adjusted for percent African ancestry. Other variables did not change the estimate >10% (BMI, education, insurance, smoking status, diabetes status, and parity). The final model satisfied the ANOVA goodness of fit test compared to other models. For comparability, we used the same model for tagging SNPs. All associations were adjusted for multiple comparisons and linkage disequilibrium (LD) using ‘LD adjusted’ Bonferroni corrected p-value thresholds [35]. LD of two SNPs characterized dependent heritability which was measured using PLINK software. The resulting associations were weighted by the inverse of their variances to summarize across studies and race in a meta-analysis. Lastly, HaploReg software (version 4.1) was used to find if these studied SNPs were in LD with functional SNPs [36]. A sensitivity analysis on the ancestry informative markers was conducted by rerunning analysis on only self-reported race.

Results

Supplemental Fig. 1 flowchart summarizes the final sample sizes, and final number of SNPs for each candidate gene after data quality control. Missingness did not differ by chromosome (p > 0.05) or the two study samples (p > 0.05). However, SNPs for Black mothers were more likely to be missing than SNPs in White mothers (p < 0.05). More specifically, SNPs in Black mothers in CPP were more likely to be missing and SNPs in White mothers in EVITA were less likely to be missing compared to other race-study groups.

Compared with mothers from EVITA, mothers from CPP completed less education (83% vs. 48% with high school education or less), had a higher prevalence of smoking (66% vs. 12%), and lower prevalence of obesity (4% vs. 23% BMI ≥ 30). On average, women in CPP were younger (24 ± 5.6 years) than women in EVITA (29 ± 6.3 years). Blood samples in EVITA were collected earlier in gestation than CPP (15 weeks versus 19 weeks). Black mothers in CPP completed fewer years of education and were leaner, multiparous, and were more likely to smoke compared with Black mothers in EVITA. Similarly, White mothers in CPP also completed fewer years of education, were more likely to have normal BMI, multiparous, and smoke compared with White mothers in EVITA (Table 1).

Table 1.

Population characteristics for controls and cases in CPP and EVITA by race.

| CPP |

EVITA |

CPP |

EVITA |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black maternal race: n = 613 Number (%) | Black maternal race: n = 269 Number (%) | White maternal race: n = 606 Number (%) | White maternal race: n = 923 Number (%) | |

| 25(OH)D (nmol/L)* | ||||

| <25 | 147(22) | 33(12) | 33(5) | 6(1) |

| 25–50 | 303(46) | 109(41) | 199(33) | 75(8) |

| 50–75 | 126(19) | 93(34) | 219(36) | 368(40) |

| ≥75 | 84(13) | 34(13) | 155(26) | 474(51) |

| Seasona | ||||

| Winter | 148(22) | 56(21) | 145(24) | 194(21) |

| Spring | 165(25) | 78(29) | 158(26) | 267(29) |

| Summer | 178(27) | 65(24) | 139(23) | 231(25) |

| Fall | 169(26) | 70(26) | 164(27) | 231(25) |

| Mean sample age** | 20.2 ±0.17 weeks | 15.0 ±0.17 weeks | 18.9 ±0.22 weeks | 15.0 ±0.08 weeks |

| BMI* | ||||

| <18.5 | 73(11) | 13(5) | 55(09) | 18(2) |

| 18.5–24.9 | 442(67) | 100(37) | 466(77) | 462(50) |

| 25–29.9 | 112(17) | 65(24) | 67(11) | 258(28) |

| ≥30 | 33(5) | 91(34) | 18(3) | 185(20) |

| Education* | ||||

| Less than HS | 390(59) | 51(19) | 242(40) | 212(23) |

| 12 | 204(31) | 108(40) | 218(36) | 212(23) |

| >12 | 66(10) | 110(41) | 146(24) | 508(55) |

| Smoker* | ||||

| Yes | 455(69) | 49(13) | 339(56) | 92(10) |

| No | 205(31) | 329(87) | 267(44) | 514 (90) |

| <20* | 186(29) | 51(19) | 103 (17) | 28(3) |

| 20–29 | 380(57) | 156(58) | 406(0.67) | 341(37) |

| ≥30 | 94(14) | 62(23) | 97(16) | 554(60) |

| Nulliparity | ||||

| 0 | 201(30) | 132(49) | 218(36) | 443(48) |

| 1 or more | 459(70) | 137(51) | 388(64) | 480(52) |

Winter (December–February), spring (March–May), summer (June–August), and fall (September–November).

p-value <0.05 for chi-square tests across the four race-study groups.

p-value < 0.05 for test of homogeneity of means between the four race-study groups.

The prevalence of vitamin D deficiency was higher in Black mothers than White mothers in both study populations (68% in CPP and 53% in EVITA vs. 38% in CPP and 9% in EVITA, respectively). The geometric means and 95% confidence intervals of 25(OH)D were 36.6 nmol/L (35, 38 nmol/L) and 45 nmol/L (42, 48 nmol/L) among Black mothers in CPP and EVITA, respectively, and 54 nmol/L (52, 56 nmol/L) and 73 nmol/L (72, 74 nmol/L) among White mothers in CPP and EVITA, respectively.

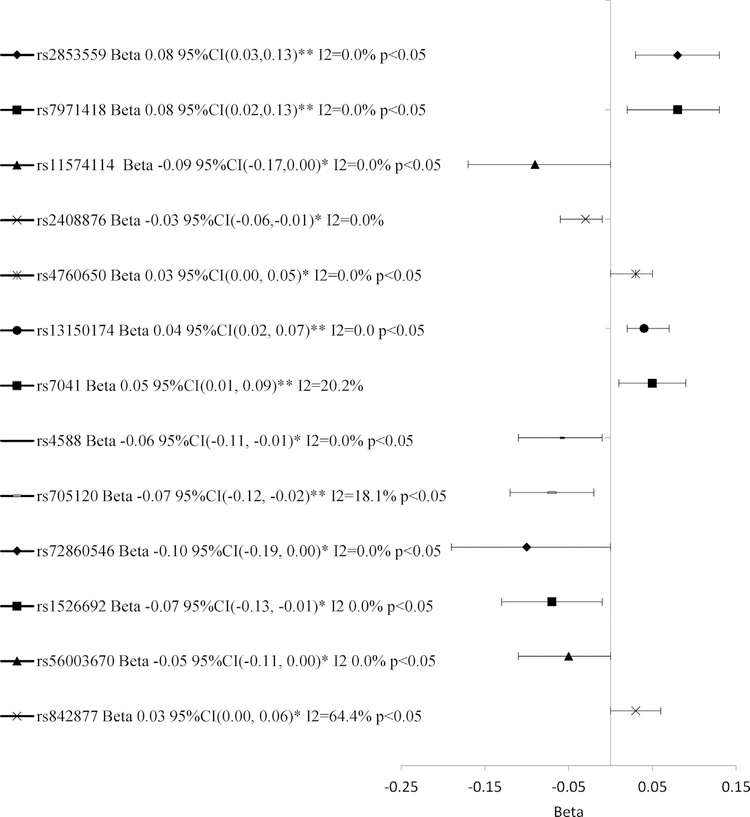

Several intron variants of VDR were associated with significant differences in log-25(OH)D concentrations in the univariate and multivariable analysis (Table 2; Data Brief article). An intron variant of the 5-prime untranslated region (rs11168293) was associated with increased log-25(OH)D compared with the major allele among Black mothers in EVITA (beta 0.22 95%CI 0.10, 0.35 p < 0.001). This association remained significant after Bonferroni adjustment. For other SNPs, the associations in the multivariable analyses attenuated in significance after adjustment for multiple comparisons. However, one variant (rs2853559) had a trend of increased log-25(OH)D concentration in the multivariable analysis and showed a significant difference in log-25(OH)D by allelic loci in the meta-analysis (Fig. 1). Although not significant in the multivariable analysis, the meta-analysis revealed associations for four intron variants (rs7971418, rs11574114, rs2408876 and rs4760650). Variants rs7971418 (rs2853562, rs9729, rs78783628, rs739837) and rs11574114 (rs11574139, rs2853563, rs3858733, rs11574119) had strong LD (R2 >0.90) with variants in the VDR 3-prime untranslated region.

Table 2.

Association between minor alleles of VDR variants and log-25(OH)D compared with major alleles by maternal race and study.a

| Variant | Race-study group | Allelic Count |

Mean 25(OH)D, nmol/L by allele |

Unadjusted Beta (95%CI) | Adjusted Beta (95%CI)b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major | Minor | Major | Minor | ||||

| rs11168293 | C., B. | G 983 | T 137 | 43.3 | 42.0 | −0.03(−0.14, 0.08) | −0.04(−0.13, 0.05) |

| C.,W. | G 756 | T 316 | 59.8 | 60.7 | 0.03(−0.04, −0.09) | 0.04(−0.02, 0.10) | |

| E., B. | G 425 | T 47 | 48.9 | 58.4* | 0.21(0.08, 0.34)*** | 0.22(0.10, 0.35)**** | |

| E., W. | G 1151 | T 443 | 76.9 | 75.3 | −0.02(0.06, 0.02) | −0.02(−0.05, 0.02) | |

| rs2853559 | C., W. | G 696 | A 388 | 59.4 | 61.8 | 0.07(0.00, 0.13)** | 0.08(0.02,0.14)*** |

| E., B. | G 384 | A 108 | 49.1 | 51.8 | 0.08(−0.03, 0.19) | 0.08(−0.02,0.18) | |

| rs7971418 | C., B. | A 575 | C 459 | 43.1 | 43.7 | 0.05(−0.03, 0.12) | 0.07(0.00,0.14) |

| E., B. | A 254 | C 202 | 47.2 | 54.2* | 0.13(0.03, 0.23)** | 0.10(0.01,0.19)** | |

| rs11574114 | C., B. | C 1017 | T 119 | 43.7 | 39.1* | −0.09(−0.20, 0.03) | −0.10(−0.21,0.01) |

| E., B. | C 442 | T 40 | 50.3 | 49.4 | 0.00(−0.15, 0.14) | −0.07(−0.20,0.06) | |

| rs2408876 | C., B. | T 562 | C 526 | 43.7 | 41.0 | −0.07(−0.14, 0.00) | −0.04(−0.10,0.03) |

| C., W. | T 641 | C 461 | 61.8 | 58.5* | −0.05(−0.11, 0.01) | −0.04(−0.09,0.02) | |

| E., B. | T 264 | C 234 | 51.2 | 47.2* | −0.08(−0.17, 0.02) | −0.07(−0.16,0.03) | |

| E., W. | T 1001 | C 709 | 76.7 | 75.5 | −0.02(−0.05, 0.01) | −0.02(−0.05,0.01) | |

| rs4760650 | C., B. | G 909 | T 199 | 43.4 | 42.4 | −0.03(−0.10, 0.05) | −0.01(−0.08,0.06) |

| C., W. | G 812 | T 250 | 60.0 | 59.8 | 0.00(−0.06, 0.06) | 0.03(−0.02,0.09) | |

| E., B. | G 423 | T 75 | 49.3 | 52.4 | 0.05(−0.07, 0.18) | 0.06(−0.06,0.17) | |

| E., W. | G 1234 | T 372 | 76.3 | 77.6 | 0.03(0.00, 0.06) | 0.03(0.00,0.06)** | |

Vitamin D receptor, VDR;25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; CI, confidence interval; C., B., CPP study, Black race; C., W., CPP study, White race; E., B., EVITA study, Black race; E., W., EVITA study, White race.

Groups not shown for each SNP did not pass quality control steps.

Adjusted for batch number (in EVITA only), year drawn (in EVITA only), site (CPP), season of blood draw, sample age, ancestry (for black race/ethnicity models only) and maternal age.

p < 0.05 based on a test for trend.

Betas and 95% CI that reach statistical significance at p < 0.05.

Betas and 95% CI that reach statistical significance at p < 0.01.

Betas and 95% CI that reach statistical significance at p < 0.001.

Fig. 1.

Meta-analysis for associations between minor alleles of SNPs in VDR, GC, and CYP27B1 and log-25(OH)D across CPP and EVITA studies and maternal race groups.

Several SNPs in the non-coding and flanking regions of GC were associated with significant differences in log-25(OH)D concentrations in the univariate and multivariable analysis (Table 3; Data Brief article). A minor allele of the flanking region (rs13150174) and a missense mutation (rs7041) were associated with increased log-25(OH)D compared with the major allele only among White mothers in EVITA (p <0.001), however significance of the associations attenuated after Bonferroni adjustment. The metaanalysis showed an overall significant trend of increased log-25 (OH)D concentration for the minor alleles of rs13150174 and rs7041 across the four study-race groups (Fig. 1). Additionally, several minor alleles in GC were associated with a difference in log-25(OH)D in the meta-analysis, including the following: a missense variant (rs4588), three intron variants (rs705120, rs72860546, and rs1526692) and two variants of the flanking region (rs56003670 and rs842877). Variants rs13150174, rs7041, rs4588, and rs72860546 were in LD with several intron variants of GC, while rs1526692 and rs56003670 were in LD with variants of the flanking regions, and rs705120 was in LD with a missense mutation (rs7041).

Table 3.

Association between minor alleles of GC variants and log-25(OH)D compared with major alleles by maternal race and study.a

| Variant | Race-study group | Allelic Count |

Mean 25(OH)D, nmol/L by allele |

Unadjusted Beta (95%CI) | Adjusted Beta (95%CI)b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major | Minor | Major | Minor | ||||

| rs11732451 | C., W. | A 912 | G 202 | 59.0 | 62.7 | 0.07(−0.01, 0.14) | 0.07(0.00, 0.14)** |

| rs13150174 | C., B. | A 866 | T 222 | 43.0 | 44.2 | 0.04(−0.04, 0.12) | 0.02(−0.06, 0.10) |

| C., W. | A 742 | T 360 | 58.5 | 63.4* | 0.07(0.01, 0.14)** | 0.05(0.00, 0.11) | |

| E., B. | A 376 | T 82 | 48.7 | 48.2 | 0.00(−0.12, 0.12) | 0.00(−0.11, 0.12) | |

| E., W. | A 1131 | T 471 | 74.7 | 78.4* | 0.04(0.01, 0.08)** | 0.04(0.01, 0.08)*** | |

| rs7041 | C., B. | A 1018 | C 68 | 42.1 | 51.7* | 0.20(0.04, 0.35)** | 0.16(0.02, 0.31)** |

| C., W. | A 705 | C 331 | 59.3 | 61.8 | 0.04(−0.02, 0.10) | 0.05(−0.01, 0.10) | |

| E., B. | A 457 | C 35 | 49.4 | 48.4 | −0.01(−0.17, 0.15) | −0.03(−0.17, 0.11) | |

| E., W. | A 1141 | C 449 | 75.0 | 79.4* | 0.05(0.02, 0.09)*** | 0.05(0.01, 0.08)*** | |

| rs4588 | C., B. | G 1029 | T 113 | 43.6 | 38.5* | −0.10(−0.21,0.00) | −0.08(−0.18, 0.01) |

| C., W. | G 816 | T 306 | 61.3 | 56.3* | —0.07(−0.14, −0.01)** | −0.06(−0.12, 0.00) | |

| E., B. | G 454 | T 58 | 50.0 | 49.1 | −0.04(−0.20, 0.13) | 0.00(−0.14, 0.14) | |

| rs705120 | C., B. | C 512 | A 494 | 43.4 | 41.3 | −0.03(−0.11, 0.05) | −0.04(−0.11, 0.03) |

| C., W. | C 622 | A 398 | 63.2 | 56.3* | −0.11(−0.18, −0.04)*** | −0.10(−0.16, −0.03)*** | |

| rs72860546 | C., B. | C 1043 | T 77 | 43.4 | 36.0* | −0.13(−0.25, −0.01)** | −0.13(−0.24, −0.01)** |

| E., B. | C 456 | T 40 | 50.1 | 49.1 | −0.05(−0.25, 0.14) | −0.03(−0.20, 0.15) | |

| rs1526692 | C., B. | A 575 | G 465 | 44.4 | 41.6 | −0.08(−0.16, 0.00)** | −0.06(−0.13, 0.01) |

| E., B. | A 262 | G 202 | 51.5 | 48.5 | —0.07(—0.18, 0.04) | −0.08(−0.18, 0.02) | |

| rs56003670 | C., B. | A 806 | C 244 | 43.5 | 41.1 | −0.09(−0.18, 0.01) | −0.05(−0.14, 0.03) |

| C., W. | A 751 | C 329 | 61.8 | 57.2* | −0.06(−0.13, 0.01) | −0.06(−0.12, 0.01) | |

| rs842877 | C., B. | C 993 | T 111 | 42.9 | 43.4 | −0.02(−0.14, 0.09) | −0.03(−0.13, 0.07) |

| C., W. | C 823 | T 267 | 60.0 | 61.4 | 0.01(−0.06, 0.09) | 0.02(−0.05, 0.09) | |

| E., B. | C 430 | T 60 | 49.3 | 52.6 | 0.07(−0.05, 0.20) | 0.08(−0.04, 0.20) | |

| E., W. | C 1213 | T 449 | 75.6 | 77.9* | 0.03(0.00, 0.07) | 0.04(0.01, 0.07)** | |

Vitamin D binding protein, GC; 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; CI, confidence interval; C., B., CPP study, Black race; C., W., CPP study, White race; E., B., EVITA study, Black race; E., W., EVITA study, White race.

Groups not shown for each SNP did not pass quality control steps.

Adjusted for batch number (in EVITA only), year drawn (in EVITA only), site (CPP), season of blood draw, sample age, ancestry (for black race/ethnicity models only) and maternal age.

p < 0.05 based on a test for trend.

Betas and 95% CI that reach statistical significance at p < 0.05.

Betas and 95% CI that reach statistical significance at p <0.01.

One intron variant in the flanking region of CYP27B1 (rs10877011) was associated with increased log-25(OH)D concentration among Black mothers in EVITA in the multivariable analysis but significance was lost after Bonferroni adjustment (beta 0.15 95%CI 0.04, 0.26 p <0.01) (Table 4; Data Brief article). The meta-analysis showed a variant of the 3-prime untranslated region (rsl2318065) and two intron variants (rsl2582311 and rs701007) were associated with differences in log-25(OH)D (Fig. 1). These variants were not in LD with functional variants in CYP27B1.

Table 4.

Mean 25(OH)D concentration by genetic variant for selected CYP27B1 by maternal race and study.a

| Variant | Race-study group | Allelic Count |

Mean 5(OH)D, nmol/L by allele |

Unadjusted Beta (95%CI) | Adjusted Beta (95%CI)b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major | Minor | Major | Minor | ||||

| rs10877011 | C., B. | T 1017 | G 135 | 43.3 | 42.7 | −0.04(−0.16, 0.09) | −0.06(−0.1, 0.06) |

| C., W. | T 741 | G 339 | 59.8 | 60.3 | 0.01(−0.06, 0.08) | 0.0(−0.06, 0.07) | |

| E., B. | T 425 | G 71 | 56.4 | 48.3* | 0.17(0.05, 0.30)*** | 0.15(0.04, 0.26)*** | |

| rs12318065 | C., B. | C 920 | A 144 | 42.6 | 44.8 | 0.08(−0.02, 0.17) | 0.07(−0.02, 0.15) |

| E., B. | C 345 | A 97 | 49.6 | 52.9 | 0.09(−0.02, 0.19) | 0.11(0.02, 0.21)** | |

| rs12582311 | C., W. | A 868 | G 244 | 59.3 | 62.4 | 0.05(−0.03,0.12) | 0.05(−0.03, 0.12) |

| E., B. | A 316 | G 154 | 49.7 | 52.2 | 0.10(0.00, 0.19)** | 0.09(0.00, 0.18)** | |

| rs701007 | C., B. | C 843 | A 259 | 42.9 | 41.9 | −0.05(−0.14, 0.03) | −0.04(−0.12, 0.04) |

| C., W. | C 650 | A 470 | 61.0 | 59.0 | −0.03(−0.10, 0.03) | −0.03(−0.09, 0.03) | |

| E., B. | C 363 | A 135 | 50.7 | 47.7 | −0.07(−0.18, 0.03) | −0.09(−0.18, 0.00)** | |

1 alpha-hydroxylase, CYP27B1; 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; CI, confidence interval; C., B., CPP study, Black race; C., W., CPP study, White race; E., B., EVITA study, Black race; E., W., EVITA study, White race.

Groups not shown for each SNP did not pass quality control steps.

Adjusted for batch number (in EVITA only), year drawn (in EVITA only), site (CPP), season of blood draw, sample age, ancestry (for black race/ethnicity models only) and maternal age.

p < 0.05 based on a test for trend.

Betas and 95% CI that reach statistical significance at p < 0.05.

Betas and 95% CI that reach statistical significance at p < 0.01.

The sensitivity analysis showed no differences in the results for VDR, GC, and CYP27B1 variants (data not shown) when using just self-reported maternal race.

Comment

Maternal genotype of seven SNPs in VDR, three SNPs in GC, and one SNP in the flanking region of CYP27B1 were associated with differences in log-25(OH)D concentration during pregnancy. Of these associations, one SNP in VDR remained significant after adjustment for LD and multiple comparisons (rs11168293). The meta-analytic approach confirmed the associations for one SNP in VDR (rs2853559) and two SNPs in GC (rs13150174 and rs7041). The meta-analytic approach also revealed possible relationships for each of the three genes. Variants in VDR were in LD with variants in the 3-prime untranslated region of VDR.

SNPs in VDR may influence serum 25(OH)D by changing the rate at which 25(OH)D is hydroxylated [37] either directly or via a negative feedback loop. In a study of 354 White pregnant women, maternal 25(OH)D did not vary by VDR genotype. However, this study included only four SNPs–three of which were included in our analysis [38]. These variants, rs7975232, rs1544410, and rs731236, were not associated with 25(OH)D concentration in our study. However, one SNP, rs7971418, had strong LD (R2 > 0.90) with 4 functional variants in the VDR 3-prime untranslated region in our study. Variants in this region may be regulating mRNA stability [39], thereby the variant may be modulating VDR expression. Additionally, our study measured associations between log-25 (OH)D and several minor alleles of intronic variants in VDR that are in LD with variants in the VDR 3-prime untranslated region. These findings support a possible role of VDR with 25(OH)D concentration in pregnancy.

We genotyped common SNPs across the GC region that encodes DBP which is a protein that controls the bioavailability of free 25 (OH)D [40], and therefore may be a surrogate marker for 25(OH)D status. The minor allele for rs7041 was associated with increased 25(OH)D and rs4588 was associated with decreased 25(OH)D in our study. We are not aware of published reports examining allelic variation within GC and serum 25(OH)D concentrations among pregnant women. Our results for rs7041 do contrast with literature that show 25(OH)D concentrations are reduced with the rs7041 minor allele among ethnically diverse samples of non-pregnant adults; while our finding on rs4588 is consistent with this literature [41–46]. It is possible that changes that occur in pregnancy, including increased circulation of DBP from 7% to 152% [16] and enhanced hydroxylation of 25(OH)D to 1,25(OH)2D [17], may explain these differences in study results. It is also possible that our results for rs7041 may be influenced by the heterogeneity measured between the race-study groups.

The CYP27B1 gene encodes an enzyme called 1-alpha-hydroxylase (1α-hydroxylase), which converts 25(OH)D from diet and sunlight to its active form, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Variations in this gene is shown to be associated with lower 25(OH)D [47], perhaps due to changes in enzymatic activity [48]. In a cohort of 222 White, diabetic pregnant women, the minor genotype of rs10877012 was more common in women with 25(OH)D > 50 nmol/L at 24 weeks of gestation compared to the major genotype (p = 0.01) [37]. Our study did not confirm their results in the univariable, multivariable, or meta-analysis.

By setting thresholds for missing data by SNP and by samples in the quality control steps, we reduced the likelihood of spurious data due to failed assays and poor-quality samples, respectively. If these quality control steps were avoided, differences in DNA quality could have biased towards one genotype or another [49]. After quality control steps, there were differences in missingness of SNP data by race and study-race group, but it did not differ by chromosome. Since samples were randomly distributed on each genotyping array the chances of systemic bias were minimized. The differences in missingness may indicate that there were differences in DNA quality between studies. It is possible that we may not have detected all associations due to the loss of some SNPs. However, it seems unlikely that SNP missingness yielded false-positive associations. Nonetheless, future genome wide association studies are needed to identify additional genes and alleles for 25(OH)D concentrations in pregnant women. Furthermore, since we only studied two ancestral groups, our findings may not be generalizable to other ancestral groups. Despite a proportion of women being recategorized into the Black ancestry group, our sensitivity analysis showed no significant difference in findings if we only used self-reported race in our study. There were non-genetic factors that may have also affected serum 25(OH)D concentration during pregnancy, such as supplement use, that were not measured and adjusted for in the analysis. If factors differed by vitamin D metabolic loci, it is possible the observed results could have been biased but this seems unlikely. Our study also has notable strengths including the large sample of Black and White pregnancies and utilization of ancestry informative markers rather than sole reliance on self-reported race. In comparison to previous studies, our approach of genotyping multiple tagging SNPs in two large and diverse samples had greater power to more comprehensively assess candidate gene variation.

If our results linking SNPs in VDR, GC, or CYP27B1 with 25(OH)D concentration among pregnant women are confirmed, then genotyping of common allelic variants may play an important role in vitamin D metabolism in pregnancy. This knowledge may ultimately help us to better understand how the vitamin D endocrine system may contribute to vitamin D deficiency in pregnancy by identifying functional variants.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

Supported by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention cooperative agreement U01 DP003177.

Abbreviations

- 25(OH)D

25-hydroxyvitamin D

- CYP27B1

1 alpha-hydroxylase

- GC

vitamin D binding protein

- VDR

vitamin D receptor

- chr

chromosome

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphisms

- 25(OH)D

25-hydroxyvitamin D

- BMI

body-mass index

- ICD-9

International Classification of Diseases

- OR

odds ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- ASW

Americans of African Ancestry in Southwest USA

- CEU

Utah residents with Northern and Western European ancestry

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2017.11.013.

References

- [1].Looker AC, Johnson CL, Lacher DA, Pfeiffer CM, Schleicher RL, Sempos CT. Vitamin D status: United States, 2001–2006. NCHS Data Brief 2011;59:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bodnar LM, Simhan HN, Powers RW, Frank MP, Cooperstein E, Roberts JM. High prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency in black and white pregnant women residing in the northern United States and their neonates. J Nutr 2007;137 (2):447–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Johnson DD, Wagner CL, Hulsey TC, McNeil RB, Ebeling M, Hollis BW. Vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency is common during pregnancy. Am J Perinatol 2011;28(1):7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Gordon CM, Hanley DA, Heaney RP, et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metabo 2011;96 (7):1911–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Forrest KY, Stuhldreher WL. Prevalence and correlates of vitamin D deficiency in US adults. Nutr Res (New York, NY) 2011;31(1):48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Taksler GB, Cutler DM, Giovannucci E, Keating NL. Vitamin D deficiency in minority populations. Public Health Nutr 2015;18(03):379–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Elder CJ, Bishop NJ. Rickets. Lancet 2014;383(9929):1665–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Wei SQ. Vitamin D and pregnancy outcomes. Curr Opin Obstetrics Gynecol 2014;26(6):438–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hypponen E, Cavadino A, Williams D, Fraser A, Vereczkey A, Fraser WD, et al. Vitamin D and pre-eclampsia: original data, systematic review and metaanalysis. Ann Nutrit Metab 2013;63(4):331–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wei SQ, Qi HP, Luo ZC, Fraser WD. Maternal vitamin D status and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Mater-Fetal Neonatal Med 2013;26(9):889–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Pojsupap S, Iliriani K, Sampaio TZ, O’Hearn K, Kovesi T, Menon K, et al. Efficacy of high-dose vitamin D in pediatric asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Asthma 2015;52(4):382–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Chakhtoura M, Azar ST. The role of vitamin D deficiency in the incidence, progression, and complications of type 1 diabetes mellitus. Int J Endocrinol 2013;2013:148673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wang TJ, Zhang F, Richards JB, Kestenbaum B, van Meurs JB, Berry D, et al. Common genetic determinants of vitamin D insufficiency: a genome-wide association study. Lancet 2010;376(9736):180–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ahn J, Yu K, Stolzenberg-Solomon R, Simon KC, McCullough ML, Gallicchio L, et al. Genome-wide association study of circulating vitamin D levels. Hum Mol Genet 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Signorello LB, Shi J, Cai Q, Zheng W, Williams SM, Long J, et al. Common variation in vitamin D pathway genes predicts circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels among African Americans. PLoS One 2011;6(12):e28623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Brannon PM, Picciano MF. Vitamin D in pregnancy and lactation in humans. Annu Rev Nutr 2011;31:89–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Evans KN, Bulmer JN, Kilby MD, Hewison M. Vitamin D and placental-decidual function. J Soc Gynecol Invest 2004;11(5):263–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Shin JS, Choi MY, Longtine MS, Nelson DM. Vitamin D effects on pregnancy and the placenta. Placenta 2010;31(12):1027–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bodnar LM, Platt RW, Simhan HN. Early-pregnancy vitamin D deficiency and risk of preterm birth subtypes. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125(2):439–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Bodnar LM, Simhan HN, Catov JM, Roberts JM, Platt RW, Diesel JC, et al. Maternal vitamin D status and the risk of mild and severe preeclampsia. Epidemiology 2014;25(2):207–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Zerwekh JE. The measurement of vitamin D: analytical aspects. Ann Clin Biochem 2004;41(Pt 4):272–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Bodnar LM, Catov JM, Wisner KL, Klebanoff MA. Racial and seasonal differences in 25-hydroxyvitamin D detected in maternal sera frozen for over 40 years. Br J Nutr 2009;101(2):278–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Holick M, Siris E, Binkley N, Beard M, Khan A, Katzer J, et al. Prevalence of vitamin D inadequacy among postmenopausal North American women receiving osteoporosis therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005;90:3215–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].The international HapMap project. Nature 2003;426(6968):789–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 2000;155(2):945–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Falush D, Stephens M, Pritchard JK. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: linked loci and correlated allele frequencies. Genetics 2003;164(4):1567–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Falush D, Stephens M, Pritchard JK. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: dominant markers and null alleles. Mol Ecol Notes 2007;7(4):574–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Hubisz MJ, Falush D, Stephens M, Pritchard JK. Inferring weak population structure with the assistance of sample group information. Mol Ecol Res 2009;9(5):1322–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kosoy R, Nassir R, Tian C, White PA, Butler LM, Silva G, et al. Ancestry informative marker sets for determining continental origin and admixture proportions in common populations in America. Hum Mutat 2009;30(1):69–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Hayes CE, Nashold FE, Spach KM, Pedersen LB. The immunological functions of the vitamin D endocrine system. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-Grand, France) 2003;49(2):277–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Niswander K, Gordon M. The Collaborative Perinatal Study of the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke: The Women and Their Pregnancies. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol Ecol 2005;14 (8):2611–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Anderson CA, Pettersson FH, Clarke GM, Cardon LR, Morris AP, Zondervan KT. Data quality control in genetic case-control association studies. Nat Protocols 2010;5(9):1564–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, et al. PLINK: a toolset for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analysis. Am J Hum Genet 2007;81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Duggal P, Gillanders EM, Holmes TN, Bailey-Wilson JE. Establishing an adjusted p-value threshold to control the family-wide type 1 error in genome wide association studies. BMC Genomics 20089: 516–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Ward LD, Kellis M. HaploReg: a resource for exploring chromatin states, conservation, and regulatory motif alterations within sets of genetically linked variants. Nucleic Acids Res 2011. 40(Database issue) D930–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Wu S, Ren S, Nguyen L, Adams JS, Hewison M. Splice variants of the CYP27b1 gene and the regulation of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 production. Endocrinology 2007;148(7):3410–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Morley R, Carlin JB, Pasco JA, Wark JD, Ponsonby AL. Maternal 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration and offspring birth size: effect modification by infant VDR genotype. Eur J Clin Nutr 2009;63(6):802–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Fang Y, van Meurs Joyce BJ, d’Alesio A, Jhamai M, Zhao H, Rivadeneira F, et al. Promoter and 3′-untranslated-region haplotypes in the vitamin D receptor gene predispose to osteoporotic fracture: the rotterdam study. Am J Hum Genet 2005;77(5):807–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Powe CE, Evans MK, Wenger J, Zonderman AB, Berg AH, Nalls M, et al. Vitamin D-binding protein and vitamin D status of black americans and white americans. New Engl J Med 2013;369(21):1991–2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Ahn J, Yu K, Stolzenberg-Solomon R, Simon KC, McCullough ML, Gallicchio L, et al. Genome-wide association study of circulating vitamin D levels. Hum Mol Genet 2010;19(13):2739–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Sinotte M, Diorio C, Bérubé S, Pollak M, Brisson J. Genetic polymorphisms of the vitamin D binding protein and plasma concentrations of 25-hydroxyvi- tamin D in premenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;89(2):634–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Engelman CD, Meyers KJ, Ziegler JT, Taylor KD, Palmer ND, Haffner SM, et al. Genome-wide association study of vitamin D concentrations in Hispanic Americans: the IRAS family study. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2010;122 (4):186–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Fu L, Yun F, Oczak M, Wong BY, Vieth R, Cole DE. Common genetic variants of the vitamin D binding protein (DBP) predict differences in response of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] to vitamin D supplementation. Clin Biochem 2009;42(10–11):1174–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Fang Y, van Meurs JB, Arp P, van Leeuwen JP, Hofman A, Pols HA, et al. Vitamin D binding protein genotype and osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int 2009;85(2):85–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Jorde RSH, Wilsgaard T, Joakimsen RM, Mathiesen EB, Njølstad I, Løchen ML, et al. Polymorphisms related to the serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level and risk of myocardial infarction, diabetes, cancer and mortality. The Tromsø Study. PLoS One 20127(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Orton SM, Morris AP, Herrera BM, Ramagopalan SV, Lincoln MR, Chao MJ, et al. Evidence for genetic regulation of vitamin D status in twins with multiple sclerosis. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;88(2):441–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Jacobs ET, Van Pelt C, Forster RE, Zaidi W, Hibler EA, Galligan MA, et al. CYP24A1 and CYP27B1 polymorphisms modulate vitamin D metabolism in colon cancer cells. Cancer Res 2013;73(8):2563–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Wellcome: genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature 2007;447(7145):661–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.