Abstract

Background:

The association of body mass index (BMI) with survival after lung transplantation remains controversial, owing to conflicting evidence in the literature. Previous reports have used traditional BMI categories, included patients who underwent transplantation before implementation of the lung allocation score (LAS), or were limited by single-center experiences. Here we evaluated the association of individual BMI units with short-term and long-term mortality in a large national database following implementation of the LAS.

Methods:

The Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients database was used to collect data for 17,233 adult lung transplantations performed between May 2005 and June 2016. The primary outcome was all-cause mortality at 90 days and 1 year posttransplantation. Logistic regression modeling was used to independently predict mortality per BMI unit, adjusting for donor and recipient factors.

Results:

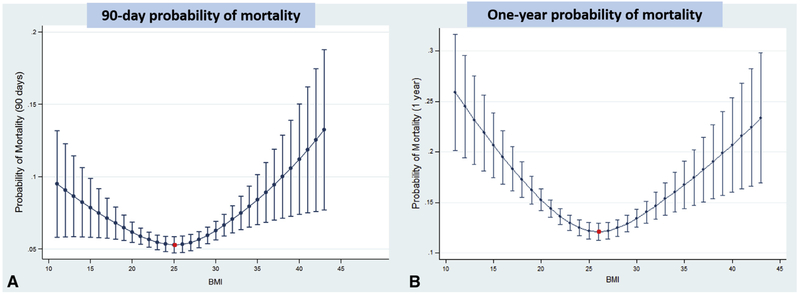

BMI was an independent predictor of mortality at both 90 days and 1 year. At 90 days, a BMI of 25 was associated with the lowest predicted probability of death (0.053; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.047-0.049), with increased odds of mortality at BMI ≤20 and ≥28. At 1 year, a BMI of 26 was associated with the lowest predicted probability of death (0.12; 95% CI, 0.110.13), with increased odds of mortality at BMI ≤24 and ≥28.

Conclusions:

Each individual BMI unit has a quantifiable effect on posttransplantation survival, and the patterns of effect do not fit into the predefined BMI categories. The mortality risk associated with BMI should be considered by transplant centers when making listing decisions and by regulatory bodies for estimating expected outcomes. (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2018;155:1871-9)

Keywords: lung transplantation, body mass index, posttransplant survival

Lung transplantation is a life-saving therapy for patients with end-stage lung disease. Expansion of clinical indications combined with improvements in perioperative recipient management and donor utilization have resulted in rapid growth, with a 44.3% increase in lung transplantations between 2006 and 2015.1 Nevertheless, lung recipients continue to suffer from poor long-term survival, with only approximately 50% alive at 5 years.2,3 Several recipient risk factors associated with poor outcomes following lung transplantation have been identified, including primary lung disease, age, kidney dysfunction, and severity of pretransplantation lung dysfunction.4 Unfortunately, most of these risk factors cannot be mitigated to improve survival after lung transplantation.

Recipient nutritional status also has been evaluated as a predictor of post-lung transplantation outcomes. Although several measures of nutritional status, including leptin concentration and body composition, have been studied, recipient body mass index (BMI) remains the most practical and widely used measure at medical centers worldwide.5,6 Studies have correlated higher BMI with poor outcomes6 and have indicated that preoperative reduction in recipient BMI improves survival after lung transplantation.7 Similarly, poor nutritional status, reflected by low BMI, is associated with higher mortality following lung transplantation.8, 9 Intriguingly, however, these findings have been refuted by other studies reporting no effect of recipient BMI status on survival following lung transplantation.10,11 The conflicting evidence in these studies results from the inconsistent use of the broad World Health Organization-defined BMI categories, small study size, and single-institution experience. As such, the impact of BMI in lung allograft recipients remains debatable.

Because recipient BMI can be modified before transplantation, determining the impact of BMI on lung transplantation outcomes is important. To address the limitations of the previous studies, we evaluated all lung transplant recipients in the United States following the implementation of lung allocation score (LAS) using the national Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) database. Furthermore, instead of using the broad BMI categories, we analyzed the impact of individual BMI units on both short-term and long-term lung transplantation-related mortality.

METHODS

Data Collection

This study used data from the SRTR. The SRTR data system includes data on all donor, wait-listed candidates, and transplant recipients in the United States, submitted by the members of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. The Health Resources and Services Administration of the US Department of Health and Human Services provides oversight to the activities of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and SRTR contractors. We included subjects who underwent lung transplantation after the introduction of the LAS between May 2005 and June 2016. We included both single and bilateral lung recipients age ≥18 years at the time of listing with lung donors of at least 12 years of age. We excluded subjects with missing data on LAS, BMI, and donor characteristics. The primary outcome was all-cause mortality at 90 days and 1 year posttransplantation.

The variables collected for these analyses included donor and recipient factors. The included donor variables were age, race, sex, cytomegalovirus (CMV) serostatus, smoking history >20 pack-years, blood type, cause of death, diabetes, and serum creatinine concentration. For recipients, we included age, race, sex, CMV status, underlying lung disease, BMI, blood type, presence of pulmonary hypertension, 6-minute walk test results, cardiac output, preoperative extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) use, LAS, serum creatinine level, and lung ischemia time. For bilateral lung transplant recipients, we used the ischemic time of either the right or left lung, whichever was longer.

Data Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata/MP14 (StataCorp, College Station, Tex). Univariate analysis of donor and recipient characteristics was performed using the Student t test for continuous variables and the ×2 test for categorical variables. Significance was set at P < .05. Restricted cubic splines with 3 knots, placed at the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles, were used to assess the nonlinear association between BMI and mortality. The optimal number of knots was selected using the Akaike information criterion, with knot placement using a standard approach.12 We then performed traditional logistic regression modeling with a stepwise backward approach. Independent variables with a P value of ≤ .20 were retained in the model. Based on that criterion, for 90-day mortality, the following factors remained in the model: recipient age at listing, recipient sex, primary lung disease, diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension, 6-minute walk test distance, preoperative ECMO use, LAS, ischemic time, and serum creatinine level (Table 4). At 1 year, the following factors remained in the model: donor race, donor sex, donor smoking history, donor diabetes, recipient age at listing, recipient sex, primary lung disease, 6-minute walk test distance, LAS, ischemic time, and recipient serum creatinine level (Table 5).

TABLE 4.

Independent predictors of 90-day mortality on logistic regression analysis

| Recipient characteristic | OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| BMI | ||

| Spline 1 | 0.95 (0.91-0.99) | .008 |

| Spline 2 | 1.07 (1.03-1.11) | <.001 |

| Age | 1.01 (1.001-1.02) | .02 |

| Male sex | 1.26 (1.08-1.47) | .003 |

| Primary lung disease | ||

| COPD | 1 | - |

| PF | 1.14 (0.91-1.43) | .27 |

| CF | 0.89 (0.61-1.31) | .57 |

| Other | 1.52 (1.21-1.90) | <.001 |

| Pulmonary HTN | 1.28 (0.87-1.89) | .22 |

| 6-min walk test | 0.9997 (0.9995-0.9998) | <.001 |

| Preoperative ECMO | 1.97 (1.37-2.82) | <.001 |

| LAS | 1.01 (1.003-1.01) | .001 |

| Serum creatinine | 1.22 (1.1-1.35) | <.001 |

| Ischemic time | 1.001 (1.00-1.001) | .1 |

OR, Odds ratio; Cl, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PF, pulmonary fibrosis; CF, cystic fibrosis; HTN, hypertension; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; LAS, lung allocation score.

TABLE 5.

Independent predictors of 1-year mortality on logistic regression analysis

| Characteristic | OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Donor characteristics | ||

| BMI | ||

| Spline 1 | 0.93 (0.90-0.95) | <.001 |

| Spline 2 | 1.07 (1.05-1.10) | <.001 |

| Race | ||

| Black | 1 | - |

| Asian | 0.84 (0.6-1.12) | .3 |

| White | 0.80 (0.71-0.9) | <.001 |

| Other | 0.55 (0.29-1.05) | .1 |

| Male sex | 0.88 (0.79-0.98) | .02 |

| Smoking history >20 pack-y | 1.25 (1.07-1.46) | .001 |

| Diabetes | 1.34 (1.12-1.6) | .002 |

| Recipient characteristics | ||

| Age | 1.02 (1.01-1.02) | <.001 |

| Male sex | 1.29 (1.15-1.44) | <.001 |

| Primary lung disease | ||

| COPD | 1 | - |

| PF | 1.12 (0.96-1.3) | .16 |

| CF | 1.03 (0.79-1.34) | .83 |

| Other | 1.43 (1.23-1.67) | <.001 |

| 6-min walk test | 0.9997 (0.9996-0.9998) | <.001 |

| LAS | 1.01 (1.006-1.012) | <.001 |

| Serum creatinine | 1.26 (1.14-1.38) | <.001 |

| Ischemic time | 1 (0.99-1.00) | .1 |

OR, Odds ratio; Cl, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PF, pulmonary fibrosis; CF, cystic fibrosis; LAS, lung allocation score.

We calculated the predicted probability of mortality per BMI unit using the logistic regression model, establishing the individual BMI unit with the lowest predicted probability of death at both 90 days and 1 year. We subsequently compared all BMI units to this baseline to calculate the odds ratio (OR) for mortality at each individual BMI unit relative to the baseline BMI. In a similar fashion, we performed subanalyses by lung transplant type (single vs bilateral) and by primary lung disease category.

RESULTS

Study Population

A total of 17,854 lung transplantations performed between May 2005 and June 2016 are included in the SRTR database. We excluded 550 transplantations for failing to meet age criteria for the donor (≤ 12 years) and/or recipient (≥18 years). We excluded an additional 71 patients for missing key data, such as recipient BMI, LAS, and donor characteristics. Therefore, our final analysis included 17,233 lung transplant recipients (Figure 1). The demographic and clinical characteristics of the entire study population are summarized in Table 1. All-cause mortality was 6.3% at 90 days and 13.8% at 1 year.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart for subjects included in the study. LAS, Lung allocation score; BMI, body mass index.

TABLE 1.

Donor and recipient demographic and clinical characteristics for the entire study population (n = 17,233)

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Donor | |

| Age, y, mean ± SD | 34.6 ± 14.1 |

| Race, n (%) | |

| Asian | 463 (2.7) |

| Black | 3393 (19.7) |

| White | 13,235 (76.8) |

| Other | 142 (0.8) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 10,398 (60.3) |

| Female | 6835 (39.7) |

| CMV positive, n (%) | 10,870 (63.1) |

| Smoking >20 pack-y, n (%) | 1677 (9.7) |

| Blood type, n (%) | |

| A | 6145 (35.7) |

| B | 1834 (10.6) |

| AB | 380 (2.2) |

| O | 8874 (51.5) |

| Cause of death, n (%) | |

| Stroke | 5928 (34.4) |

| Anoxia | 2837 (16.5) |

| Trauma | 7941 (46.1) |

| Other | 526 (3.0) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 1168 (6.8) |

| Creatinine, mg/dL, mean ± SD | 1.33 ± 1.37 |

| Recipient | |

| Age, y, mean ± SD | 54.9 ± 13.1 |

| Race, n (%) | |

| Asian | 248 (1.4) |

| Black | 1475 (8.6) |

| White | 15,392 (89.3) |

| Other | 118 (0.7) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 10,386 (60.1) |

| Female | 6847 (39.7) |

| CMV positive, n (%) | 7937 (55.2) |

| Lung disease, n (%) | |

| COPD | 4099 (23.8) |

| CF | 1917 (11.1) |

| PF | 6106 (35.4) |

| Others | 5111 (29.7) |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 25.3 ± 4.7 |

| Blood type, n (%) | |

| A | 6877 (39.9) |

| B | 1893 (11) |

| AB | 672 (3.9) |

| O | 7791 (45.2) |

| Pulmonary hypertension, n (%) | 461 (2.7) |

| ECMO, n (%) | 478 (2.8) |

| LAS, mean ± SD | 47.4 ± 17.7 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL, mean ± SD | 0.86 ± 0.5 |

| 6-min walk test, ft, mean ± SD | 796.8 ± 459.6 |

| Cardiac output, L/min, mean ± SD | 5.4 ± 1.5 |

| Ischemic time, min, mean ± SD | 307.2 ± 105.0 |

SD, Standard deviation; CMV, cytomegalovirus; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CF, cystic fibrosis; PF, pulmonary fibrosis; BMI, body mass index; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; LAS, lung allocation score.

Donor Factors and Mortality

We first assessed the impact of donor demographic and clinical factors on posttransplantation mortality (Table 2). There were no significant differences in donor characteristics between the recipients who were alive or dead at 90 days posttransplantation; however, at 1 year, recipient mortality was associated with donors who were older (mean, 35.5 ± 14.6 years vs 34.4 ± 14.0 years; P < .001), were CMV seropositive (67% vs 62.5%; P < .001), and had a >20 pack-year smoking history (12% vs 9%; P = .004). There was also a larger fraction of female donors (42% vs 39%; P = .03), African-American donors (P = .01), and stroke as the donor cause of death (P = .01) in the deceased group at 1 year.

TABLE 2.

Donor demographic and clinical characteristics

| 90 d |

1 y |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Deceased (n = 1089) | Alive (n = 16,144) | P value | Deceased (n = 2386) | Alive (n = 14,847) | P value |

| Age, y, mean ± SD | 35 ± 14.7 | 34.5 ± 14.1 | .3 | 35.5 ± 14.6 | 34.4 ± 14 | <.001 |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||

| Asian | 28 (2.6) | 435 (2.7) | .98 | 61 (2.6) | 402 (2.7) | .003 |

| Black | 233 (20.5) | 3170 (19.6) | 535 (22.4) | 2858 (19.3) | ||

| White | 831 (76.3) | 12,404 (76.8) | 1775 (74.4) | 11,460 (77.2) | ||

| Other | 7 (0.76) | 135 (0.8) | 15 (0.6) | 127 (0.8) | ||

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||

| Male | 630 (58) | 9768 (60.5) | .1 | 1392 (58) | 9006 (61) | .03 |

| Female | 459 (42) | 6376 (39.5) | 994 (42) | 5841 (39) | ||

| CMV positive, n (%) | 703 (64.6) | 10,167 (63) | .3 | 1599 (67) | 9271 (62.5) | <.001 |

| Smoking >20 pack-y, n (%) | 116 (10.7) | 1561 (9.7) | .5 | 276 (12) | 1401 (9) | .004 |

| Blood type, n (%) | ||||||

| A | 373 (34.3) | 5772 (35.8) | .6 | 828 (34.7) | 5317 (35.8) | .5 |

| B | 109 (10) | 1725 (10.7) | 243 (10.2) | 1591 (10.7) | ||

| AB | 24 (2.2) | 536 (2.2) | 55 (2.3) | 325 (2.2) | ||

| O | 583 (53.5) | 8291 (51.4) | 1260 (52.8) | 7614 (51.3) | ||

| Cause of death, n (%) | ||||||

| Stroke | 398 (36.6) | 5530 (34.3) | .1 | 891 (37.3) | 5037 (34) | .01 |

| Anoxia | 152 (14) | 2685 (16.6) | 351 (14.7) | 2486 (16.6) | ||

| Trauma | 512 (47) | 7429 (46) | 1076 (45.1) | 6865 (46.2) | ||

| Other | 27 (2.4) | 499 (3.1) | 468 (2.9) | 458 (3.1) | ||

| Diabetes, n (%) | 70 (6.5) | 1098 (6.8) | .6 | 196 (8) | 972 (7) | .003 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL, mean ± SD | 1.31 ± 1.37 | 1.33 ± 1.37 | .5 | 1.34 ± 1.34 | 1.33 ± 1.37 | .7 |

SD, Standard deviation; CMV, cytomegalovirus.

Recipient Factors and Mortality

We next evaluated the impact of recipient demographic and clinical characteristics on posttransplantation mortality (Table 3). At 90 days posttransplantation, older mean recipient age (55.9 ± 12.5 years vs 54.8 ± 13.2 years; P = .01), male sex (65.8% vs 59.9%; P < .001), primary lung disease (P < .001), higher mean BMI (25.90 ± 4.99 kg/m2 vs 25.25 ± 4.72 kg/m2; P < .001), presence of pulmonary hypertension (4% vs 3%; P = .02), preoperative ECMO use (7% vs 2.5%; P < .001), higher mean LAS (52.0 ± 20.0 vs 47.4 ± 17.5; P < .001), higher mean serum creatinine level (0.96 ± 0.51 mg/dL vs 0.86 ± 0.45 mg/dL; P < .001), longer mean ischemic time (315.1 ± 114.5 minutes vs 306.7 ± 104.3 minutes; P = .01), and shorter mean distance on the 6-minute walk test (700.1 ± 452.4 feet vs 803.6 ± 459.4 feet; P < .001) were associated with increased mortality. Factors associated with increased mortality at 1 year included older mean age (56.4 ± 13.1 years vs 54.7 ± 13.1 years; P < .001), male sex (65% vs 59.5%; P < .001), primary lung disease (P < .001), higher mean BMI (25.50 ± 5.00 kg/m2 vs 25.20 ± 4.70 kg/m2; P = .004), preoperative ECMO use (5% vs 2.4%; P < .001), higher mean LAS (51.0 ± 19.6 vs 47.2 ± 17.3; P < .001), higher mean serum creatinine level (0.93 ± 0.45 mg/dL vs 0.85 ± 0.46 mg/dL; P < .001), longer mean ischemic time (311.8 ± 110.9 minutes vs 306.4 ± 104.0 minutes; P = .02), and shorter mean distance on the 6-minute walk test (721.0 ± 463.9 feet vs 809.8 ± 457.6 feet; P < .001).

TABLE 3.

Recipient demographic and clinical characteristics

| 90 d |

1 y |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Deceased (n = 1089) | Alive (n = 16,144) | P value | Deceased (n = 2386) | Alive (n = 14,847) | P value |

| Age, y, mean ± SD | 55.9 ± 12.5 | 54.8 ± 13.2 | .01 | 56.4 ± 13.1 | 54.7 ± 13.1 | <.001 |

| Race, n (%) | .23 | .9 | ||||

| Asian | 19 (1.7) | 229 (1.4) | 31 (1.3) | 217 (1.5) | ||

| Black | 105 (9.6) | 1370 (8.5) | 200 (8.4) | 1275 (8.6) | ||

| White | 955 (87.7) | 14,437 (89.4) | 2140 (89.7) | 13,252 (89.3) | ||

| Other | 10 (1) | 108 (0.7) | 15 (0.6) | 103 (0.7) | ||

| Sex, n (%) | <.001 | <.001 | ||||

| Male | 717 (65.8) | 9669 (59.9) | 1560 (65) | 8826 (59.5) | ||

| Female | 372 (34.2) | 6475 (40.1) | 826 (35) | 6021 (40.5) | ||

| CMV positive, n (%) | 551 (56.9) | 7386 (55.1) | .1 | 1191 (54.9) | 6746 (55.3) | .6 |

| Lung disease, n (%) | <.001 | <.001 | ||||

| COPD | 198 (18.2) | 3901 (24.2) | 476 (20) | 3623 (24.4) | ||

| CF | 72 (6.6) | 1845 (11.4) | 190 (8) | 1727 (11.6) | ||

| PF | 413 (37.9) | 5693 (35.3) | 918 (38.4) | 5188 (35) | ||

| Others | 406 (37.3) | 4705 (29.1) | 802 (33.6) | 4309 (29) | ||

| BMI, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 25.9 ± 5.0 | 25.3 ± 4.7 | <.001 | 25.5 ± 5.0 | 25.2 ± 4.7 | .004 |

| Blood type, n (%) | .8 | |||||

| A | 425 (39) | 6452 (40) | .8 | 944 (39.6) | 5933 (40) | |

| B | 114 (10.5) | 1779 (11) | 253 (11) | 1640 (11.1) | ||

| AB | 48 (4.2) | 626 (3.9) | 100 (4) | 572 (3.9) | ||

| O | 504 (46.3) | 7287 (45.1) | 1089 (45.6) | 6702 (45) | ||

| Pulmonary HTN, n (%) | 41 (4) | 420 (3) | .02 | 72 (3) | 389 (3) | .3 |

| ECMO, n (%) | 76 (7) | 402 (2.5) | <.001 | 117 (5) | 361 (2.4) | <.001 |

| LAS, mean ± SD | 52.0 ± 20.0 | 47.4 ± 17.5 | <.001 | 51.0 ± 19.6 | 47.2 ± 17.3 | <.001 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL, mean ± SD | 0.96 ± 0.51 | 0.86 ± 0.45 | <.001 | 0.93 ± 0.45 | 0.85 ± 0.46 | <.001 |

| 6-min walk test, ft, mean ± SD | 700.1 ± 452.4 | 803.6 ± 459.4 | <.001 | 721.0 ± 463.9 | 809.8 ± 457.6 | <.001 |

| Cardiac output, L/min, mean ± SD | 5.4 ± 1.6 | 5.4 ± 1.5 | .9 | 5.4 ± 1.5 | 5.4 ± 1.5 | .2 |

| Ischemic time, min, mean ± SD | 315.1 ± 114.5 | 306.7 ± 104.3 | .01 | 311.8 ± 110.9 | 306.5 ± 104.0 | .02 |

SD, Standard deviation; CMV, cytomegalovirus; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CF, cystic fibrosis; PF, pulmonary fibrosis; BMI, body mass index; HTN, hypertension; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; LAS, lung allocation score.

Mortality Risk per BMI Unit

Using our logistic regression model, we identified BMI as an independent predictor of mortality at both 90 days and 1 year posttransplantation (Tables 4 and 5). We calculated the probability of mortality per individual BMI unit to identify the BMI associated with the lowest risk of death (Figure 2). At 90 days, a BMI of 25 had the lowest predicted probability of death of 0.0530 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.0475-0.0586). The predicted probability of death was 0.0535 (95% CI, 0.048-0.059) for a BMI of 24 and 0.0533 (95% CI, 0.048-0.059) for a BMI of 26. Similarly, at 1 year a BMI of 26 had the lowest predicted probability of death, at 0.121 (95% CI, 0.112-0.129). The predicted probability of death was 0.122 (95% CI, 0114-0.130) for a BMI of 25 and 0.122 (95% CI, 0.114-0.130) for a BMI of 27. A complete list of predicted probabilities of death per BMI unit is provided in Table E1.

FIGURE 2.

Predicted probability of death per body mass index (BMI) unit. Adjusted logistic regression model used in the analyses. A BMI of 25 at listing was associated with the lowest predicted probability of death at 90 days (A), whereas at 1 year, a BMI of 26 was associated with the lowest predictedprobability of death (B). Bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

TABLE E1.

Predicted probability of death per BMI unit

| BMI | 90-d mortality predicted probability (95% CI) | 1-y mortality predicted probability (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| 11 | 0.09505 (0.0582626-0.131838) | 0.258996 (0.2015714-0.31642) |

| 12 | 0.090671 (0.0584896-0.1228524) | 0.245127 (0.1946398-0.2956149) |

| 13 | 0.086474 (0.0585741-0.1143745) | 0.231769 (0.1878537-0.2756851) |

| 14 | 0.082454 (0.058519-0.1063895) | 0.218928 (0.1811943-0.2566621) |

| 15 | 0.078605 (0.058325-0.0988849) | 0.206607 (0.1746417-0.2385727) |

| 16 | 0.074921 (0.0579892-0.0918522) | 0.194807 (0.1681721-0.2214412) |

| 17 | 0.071396 (0.0575022-0.0852893) | 0.183524 (0.1617529-0.2052954) |

| 18 | 0.068025 (0.056842-0.079207) | 0.172755 (0.1553338-0.190176) |

| 19 | 0.064801 (0.0559628-0.0736398) | 0.162492 (0.1488271-0.1761566) |

| 20 | 0.061747 (0.054793-0.0687014) | 0.152791 (0.1421272-0.1634537) |

| 21 | 0.05898 (0.0532976-0.0646629) | 0.143937 (0.1352728-0.1526014) |

| 22 | 0.056623 (0.0515254-0.06172) | 0.136217 (0.12845-0.1439838) |

| 23 | 0.054779 (0.0497158-0.0598422) | 0.129859 (0.1221447-0.137573) |

| 24 | 0.053546 (0.0482485-0.0588437) | 0.125058 (0.1170267-0.1330895) |

| 25 | 0.053025 (0.0474704-0.0585793) | 0.122003 (0.113667-0.130339) |

| 26 | 0.053335 (0.0476454-0.0590236) | 0.120907 (0.1124843-0.1293289) |

| 27 | 0.054574 (0.0489114-0.0602361) | 0.121916 (0.1136596-0.1301724) |

| 28 | 0.056657 (0.0510645-0.0622488) | 0.12475 (0.1167007-.1327987) |

| 29 | 0.059456 (0.0537473-0.0651648) | 0.129045 (0.1208795-0.1372103) |

| 30 | 0.062836 (0.0565493-0.0691228) | 0.134437 (0.1254457-0.143428) |

| 31 | 0.066633 (0.0591463-0.0741204) | 0.140523 (0.129836-0.1512095) |

| 32 | 0.070685 (0.0614179-0.0799522) | 0.146925 (0.1338087-0.1600412) |

| 33 | 0.074963 (0.0634356-0.0864908) | 0.153567 (0.1374694-0.1696638) |

| 34 | 0.079478 (0.0652746-0.0936818) | 0.160452 (0.1409378-0.1799664) |

| 35 | 0.08424 (0.0669788-0.1015019) | 0.167585 (0.1442844-0.1908858) |

| 36 | 0.08926 (0.0685716-0.1099487) | 0.174969 (0.1475509-0.2023875) |

| 37 | 0.094548 (0.0700651-0.1190313) | 0.182607 (0.1507627-0.21445180) |

| 38 | 0.100115 (0.0714646-0.1287657) | 0.190502 (0.1539366-0.22706690) |

| 39 | 0.105972 (0.0727714-0.1391715) | 0.198655 (0.1570845-0.2402246) |

| 40 | 0.112128 (0.0739852-0.1502701) | 0.207067 (0.1602158-0.2539183) |

| 41 | 0.118594 (0.0751044-0.1620837) | 0.21574 (0.1633383-0.2681415) |

| 42 | 0.125381 (0.0761273-0.1746342) | 0.224673 (0.1664596-0.2828866) |

| 43 | 0.132497 (0.0770522-0.1879426) | 0.233866 (0.169587-0.2981447) |

BMI, Body mass index; CI, confidence interval.

Odds of Mortality per Individual BMI Compared With Baseline

Using the adjusted logistic regression model, we found that for every individual BMI unit increase or decrease from the baseline BMI with lowest probability of death, there was an incremental increase in the OR of mortality at both 90 days and 1 year (Figure 3). At 90 days, compared with the baseline BMI of 25, the OR for mortality became significant for a BMI of 20 (OR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.36) and a BMI of 28 (OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.13). For 1-year mortality, a BMI of 24 on the low end (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.01-1.07) and a BMI of 28 on the high end were associated with significantly higher odds of mortality (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.01-1.07) compared with the baseline BMI of 26. The complete range of ORs for mortality per BMI unit for both 90-day and 1-year mortality is provided in Table E2. The hierarchical logistic regression model generated similar results (Table E3).

FIGURE 3.

Mortality odds ratios (ORs) compared with baseline body mass index (BMI). A, At 90 days, there was a significant increase in mortality OR with BMI ≤20 and ≥28 at listing, compared with the baseline BMI of 25. B, At 1 year, compared with a BMI of 26, there was a significant increase in mortality OR with BMI ≤24 and ≥28. The shaded regions depict significant ORs; the bars, the 95% confidence intervals.

TABLE E2.

Mortality OR for individual BMI units compared with baseline BMI 25 at 90-day and BMI 26 at 1-year

| BMI | 90-d mortality OR (95% CI) |

1-y mortality OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| 11 | 1.88 (1.15-3.06) | 2.54 (1.79-3.61) |

| 12 | 1.78 (1.13-2.79) | 2.36 (1.71-3.26) |

| 13 | 1.69 (1.12-2.55) | 2.19 (1.63-2.95) |

| 14 | 1.6 (1.10-2.33) | 2.04 (1.56-2.67) |

| 15 | 1.52 (1.09-2.13) | 1.89 (1.49-2.41) |

| 16 | 1.45 (1.07-1.95) | 1.76 (1.42-2.18) |

| 17 | 1.37 (1.06-1.78) | 1.63 (1.35-1.97) |

| 18 | 1.3 (1.05-1.62) | 1.52 (1.29-1.79) |

| 19 | 1.24 (1.03-1.48) | 1.41 (1.23-1.62) |

| 20 | 1.18 (1.02-1.36) | 1.31 (1.18-1.46) |

| 21 | 1.12 (1.00-1.25) | 1.22 (1.12-1.33) |

| 22 | 1.07 (1.00-1.15) | 1.15 (1.08-1.22) |

| 23 | 1.03 (0.99-1.08) | 1.09 (1.04-1.13) |

| 24 | 1.01 (0.99-1.03) | 1.04 (1.01-1.07) |

| 25 | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) |

| 26 | 1.01 (0.99-1.02) | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) |

| 27 | 1.03 (1.00-1.07) | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) |

| 28 | 1.07 (1.02-1.13) | 1.04 (1.01-1.07) |

| 29 | 1.13 (1.04-1.22) | 1.08 (1.02-1.13) |

| 30 | 1.2 (1.07-1.34) | 1.13 (1.05-1.22) |

| 31 | 1.27 (1.11-1.47) | 1.19 (1.08-1.31) |

| 32 | 1.36 (1.14-1.62) | 1.25 (1.11-1.42) |

| 33 | 1.45 (1.18-1.78) | 1.32 (1.14-1.53) |

| 34 | 1.54 (1.21-1.96) | 1.39 (1.17-1.65) |

| 35 | 1.64 (1.25-2.16) | 1.46 (1.20-1.78) |

| 36 | 1.75 (1.28-2.38) | 1.54 (1.23-1.93) |

| 37 | 1.86 (1.32-2.63) | 1.62 (1.27-2.08) |

| 38 | 1.99 (1.36-2.90) | 1.71 (1.30-2.25) |

| 39 | 2.12 (1.40-3.19) | 1.8 (1.34-2.43) |

| 40 | 2.26 (1.45-3.52) | 1.19 (1.37-2.62) |

| 41 | 2.4 (1.49-3.88) | 2.00 (1.41-2.83) |

| 42 | 2.56 (1.53-4.28) | 2.11 (1.45-3.06) |

| 43 | 2.73 (1.58-4.71) | 2.22 (1.49-3.31) |

BMI, Body mass index; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

TABLE E3.

Summary of subgroup analyses

| 90 d |

1 y |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline BMI |

Low BMI (OR; 95% CI) |

High BMI (OR; 95% CI) |

Baseline BMI |

Low BMI (OR; 95% CI) |

High BMI (OR; 95% CI) |

|

| Analysis type | ||||||

| Hierarchical | ||||||

| All | 25 | 19 (1.22; 1.01-1.46) | 30 (1.13; 1.01-1.27) | 26 | 24 (1.04; 1.02-1.07) | 30 (1.09; 1.02-1.18) |

| SLT | 26 | NS | NS | 27 | 24 (1.07; 1.01-1.14) | 32 (1.21; 1.01-1.46) |

| BLT | 25 | NS | 30 (1.16; 1.02-1.34) | 26 | 23 (1.07; 1.02-1.13) | 31 (1.15; 1.01-1.31) |

| Primary disease | ||||||

| Obstructive | 24 | NS | 29 (1.28; 1.02-1.62) | NS | - | - |

| Pulmonary vascular | NS | - | - | 27 | 24 (1.17; 1.01-1.35) | NS |

| Cystic fibrosis | NS | - | - | NS | - | - |

| Restrictive | 25 | NS | 29 (1.11; 1.01-1.22) | 26 | 20 (1.23; 1.02-1.48) | 29 (1.08; 1.01-1.14) |

BMI, Body mass index; OR, odds ratio, CI, confidence interval; SLT, single lung transplant; NS, not significant; BLT, bilateral lung transplant.

Subgroup Analysis of Mortality Odds Using BMI Range as Baseline

Because BMIs of 24 to 26 were associated with similar probabilities of mortality at 90 days, we grouped them to define a baseline BMI range with the lowest probability of mortality. We then calculated the OR of mortality for the remaining BMI ranges (11-23 and 27-43) compared with the group with BMIs of 24 to 26. OR for mortality remained significant for BMI ≤20 (BMI 20: OR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.01-1.35) and ≥28 (BMI 28: OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.02-1.12). These values were no different than those obtained in the main analysis using BMI 25 as the baseline.

Similar to the 90-day data, at 1 year patients with a BMI of 25 to 27 had similarly low probabilities of death and thus were grouped together. We compared all other BMIs with this group. On the low end, OR remained significant at BMI ≤24 (BMI 24: OR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.01-1.06); however, on the high end, BMI ≥29 became significant (BMI 29: OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.02-1.12), which was 1 unit higher than was found in the analysis using BMI 26 as the baseline value.

Subgroup Analysis by Primary Lung Disease and Single Versus Bilateral Lung Transplantation

Previous studies have reported that the effect of BMI on recipient outcomes differs according to the type of primary lung disease.13,14 .Although we found BMI to be an independent predictor of recipient mortality regardless of primary lung disease as described above, we sought to apply our approach of analyzing BMI as individual units to each of the lung disease categories as defined by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS)3 to better characterize the effect of BMI on the disparate lung transplant recipient cohorts.

We found that of the 4 disease categories, only in the restrictive lung disease cohort did BMI emerge as an independent predictor of mortality at both 90 days and 1 year, with BMIs of 25 and 26 associated with the lowest predicted probabilities of death at 90 days and 1 year, respectively. On the low end, a BMI ≤20 was associated with an increased risk of mortality at 1 year (BMI 20: OR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.02-1.48). For 90-day and 1-year mortality, a BMI ≥29 had significantly increased odds of mortality (BMI 29: 90-day OR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.01-1.22; 1-year OR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.01-1.14) (Table E3). Similarly, in the obstructive lung disease cohort, a BMI ≥29 was associated with an increased risk of mortality compared with the baseline BMI of 24 (BMI 29: OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.62) for 90-day mortality. In the pulmonary vascular disease cohort, a BMI ≤24 was associated with an increased risk of mortality at 1 year compared with a baseline BMI of 27 (BMI 24: OR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.01-1.35). BMI was not a predictor of mortality for obstructive lung disease at 1 year or for pulmonary vascular disease at 90 days. Interestingly, BMI also was not a significant predictor of mortality in the cystic fibrosis cohort at any time point (Table E3).

Subanalysis of the single lung transplantation cohort was notable for failure to reach statistical significance for mortality OR at 90 days. The bilateral lung transplantation cohort also failed to reach statistical significance on the low end for 90-day survival. Otherwise, findings were similar to those for the entire study group (Table E3).

DISCUSSION

The impact of BMI on outcomes of lung transplantation has been an active area of investigation; however, the effect on lung recipient survival remains controversial owing to the conflicting evidence in the literature. The body of literature consists mainly of retrospective single-center studies limited by small sample size and inherent selection bias.5,11,15,16 The first study to report the association between transplant recipient BMI and survival using a large national database was published by Lederer and colleagues in 2009.14 In a series comprising more than 5900 patients in the UNOS database, being underweight, overweight, or obese was associated with an independently increased risk of mortality.14 However, in a study reported by Singer and colleagues6 using the same UNOS database, overweight patients and patients with class I obesity were found to have a similar risk of mortality as normal-weight individuals, but underweight patients and those with class II to III obesity had an elevated 1-year mortality. In contrast,Chaikriangkrai and colleagues5 found lower mortality in overweight recipients compared with normal-weight recipients. The impact of being underweight on survival after lung transplantation also lacks uniformity in the literature.9,17,18 Additional limitations of the literature on BMI and lung transplantation–related mortality are the inclusion of subjects from the pre-LAS era and adherence to the predefined broad BMI categories.

In this study, we evaluated the impact of individual BMI units on post–lung transplantation mortality following implementation of the LAS and determined the BMI cutoffs predictive of increased short-term and long-term mortality. Our study demonstrates that each BMI unit carries a distinct risk for posttransplantation mortality. We found that BMIs of 25 and 26 at time of listing were associated with the lowest probability of death at 90 days and 1 year, respectively. Interestingly, both of these BMI units lie within the traditional “overweight” BMI category. Previous studies have assumed the lowest mortality in patients within the normal BMI category and thus have compared all other BMI classes with the normal group for drawing their conclusions. Our study does not support that assumption. We also found that a BMI ≥28 was independently associated with increased odds of mortality at both early and late time points. It was indeed surprising to find that the lowest probability of mortality and the threshold above which mortality significantly increases were both within the overweight BMI class. This indicates that patients within any BMI category represent a heterogeneous group in terms of posttransplantation mortality risk. However, previous studies assumed that all patients within a BMI class have the same risk. This might have been a limitation of the previously published studies and explains the conflicting nature of the data regarding the impact of BMI on survival outcomes in lung transplant recipients.

It is widely known that lung transplantation continues to be associated with the worst graft survival of all solid organs.2 Although the causes of graft loss and patient mortality are multifactorial, with many potential points of intervention across the care continuum, preoperative candidate optimization and selection continue to be of paramount importance. The implementation of the LAS in 2005 sought to improve lung allocation in the United States and has resulted in reduced wait-list mortality in certain patient groups19; however, its impact on posttransplantation survival is still being evaluated.19,20 Intriguingly, the LAS incorporates recipient BMI in predicting wait-list mortality, but not in predicting posttransplantation survival.21 Based on our findings, we propose that BMI should be included in the estimation of posttransplantation mortality in the LAS. Furthermore, posttransplantation outcomes should factor in a correction for BMI-based risk, to avoid unfairly penalizing transplantation centers for performing transplantations in sicker patients with higher or lower BMI. Although BMI is a potentially modifiable factor, weight loss in patients needing a lung transplant is not always feasible, owing to the inability to implement a weight-loss exercise regimen in severely incapacitated patients with end-stage lung disease. In addition, these patients often require steroids to stabilize the chronic lung disease, further limiting their ability to lose weight. Finally, transplantation urgency might preclude a safe weight loss program.

The consensus statement from the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation recommends that a BMI ≥30 be considered a relative contraindication to lung transplantation.22 In response to the reported impact of recipient BMI on lung transplantation outcomes, transplantation centers across the country have developed stringent BMI thresholds for lung transplantation candidacy. Our findings suggest that for potential lung transplantation candidates starting out in an overweight or obese category, aggressive weight loss regimens with BMI targets in the normal range as a listing requirement might not be necessary, given that BMIs in the upper normal weight to overweight categories were associated with the lowest probability of death. In addition, BMI up to 28 was not associated with increased odds of mortality. Our analyses also generated notable findings at lower end of the BMI range, with BMI ≤20 associated with significantly increased odds of mortality at 90 days. The findings for 1-year mortality were more surprising, with a BMI ≤24 imparting an increased odds of death compared with the baseline BMI. It is generally accepted that patients can lose up to one-third of their body weight following lung transplantation. Thus, a plausible explanation for why normal-weight individuals may be at increased risk of death could be the peritransplantation weight loss leading to a malnourished state after transplantation. Nevertheless, it is important to understand that although the mortality associated with lower BMI achieved statistical significance, it was only marginally higher than the nadir. Thus, the urgency of transplantation, overall patient status, and practice preferences at the individual center should be considered along with BMI considerations before making a final decision about listing the patient.

A weakness of our study is the retrospective nature of the analysis. Nevertheless, by including all recipients undergoing transplantation in the country, we minimized potential selection bias. We acknowledge that the LAS formula has been adjusted since its debut in 2005, potentially introducing a confounding factor that may have remained unaccounted for. We concede that BMI might not always accurately reflect body composition. Other parameters, such as percent body fat, visceral fat area, and waist-to-hip ratio, may be more accurate; however, the performance of these parameters as risk factors for survival in lung transplant recipients is unknown, because they have not been well studied. Furthermore, these parameters are not routinely obtained as part of the lung transplantation workup in most centers, and thus are not available in the SRTR database. Despite the shortcomings of BMI as a measure of body composition, it is the simplest and most widely used system that has been well studied and can be derived anywhere across the globe, even in resource-limited settings. We also recognize that BMI is not a static measure and can fluctuate depending on any number of clinical factors. Nevertheless, by analyzing the BMI at the time of listing, we created a baseline that can be applied uniformly by all transplantation centers when listing decisions are made. We propose that our findings should not be used to conclude that heavier or thinner patients should not be undergo transplantation. Rather, the risk determined by individual BMI units should be used to make educated decision about each patient’s risk by each individual center. Furthermore, the risk associated with BMI should be used to adjust the expected outcomes for lung transplant recipients accordingly.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, BMI is an independent predictor of mortality in lung transplant recipients at both 90 days and 1 year posttransplantation in the contemporary LAS era. Recipient BMI ≤20 and ≥28 at the time of listing are associated with independently increased risks of both short-term and long-term mortality. The BMI relationships in our study demonstrate the heterogeneity in patients within the traditional BMI classes and caution against the use of traditional BMI classes to determine posttransplantation outcomes. Nevertheless, recipient BMI should be considered in estimating posttransplantation survival when listing patients for lung transplantation.

Central Message.

BMI is an independent predictor of both shortterm and long-term mortality following lung transplantation, with a quantifiable mortality risk per BMI unit.

Perspective.

Here we estimated the independent risk of short-term and long-term lung transplantation mortality associated with recipient BMI. Given the findings in this report, we propose that the mortality risk associated with each BMI unit be considered by transplant centers when making listing decisions and by regulatory bodies when estimating expected posttransplantation outcomes.

Acknowledgments

R.F. is supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant T32 DK077662, and A.B. is supported by NIH Grant HL125940.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- BMI

body mass index

- CI

confidence interval

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

- ECMO

extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- LAS

lung allocation score

- OR

odds ratio

- SRTR

Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients

- UNOS

United Network for Organ Sharing

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

Authors have nothing to disclose with regard to commercial support.

The data reported here have been supplied by the Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation as a contractor for the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and should not be viewed as an official policy of or interpretation by the SRTR or the US Government. We thank Ms Elena Susan for formatting and submitting this manuscript.

Read at the 97th Annual Meeting of The American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Boston, Massachusetts, April 29-May 3, 2017.

References

- 1.OPTN/SRTR 2015 Annual data report: introduction. Am J Transplant. 2017; 17(Suppl 1):11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lodhi SA, Lamb KE, Meier-Kriesche HU. Solid organ allograft survival improvement in the United States: the long-term does not mirror the dramatic short-term success. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:1226–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valapour M, Skeans MA, Smith JM, Edwards LB, Cherikh WS, Uccellini K, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2015 Annual data report: lung. Am J Transplant. 2017; 17(Suppl 1):357–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Russo MJ, Davies RR, Hong KN, Iribarne A, Kawut S, Bacchetta M, et al. Who is the high-risk recipient? Predicting mortality after lung transplantation using pretransplant risk factors. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138:1234–8.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaikriangkrai K, Jhun HY, Graviss EA, Jyothula S. Overweight-mortality paradox and impact of six-minute walk distance in lung transplantation. Ann Thorac Med. 2015;10:169–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singer JP, Peterson ER, Snyder ME, Katz PP, Golden JA, D’Ovidio F, et al. Body composition and mortality after adult lung transplantation in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:1012–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chandrashekaran S, Keller CA, Kremers WK, Peters SG, Hathcock MA, Kennedy CC. Weight loss prior to lung transplantation is associated with improved survival. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015;34:651–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Komatsu T, Chen-Yoshikawa TF, Oshima A, Harashima SI, Aoyama A, Inagaki N, et al. Severe underweight decreases the survival rate in adult lung transplantation. Surg Today. 2017; 10.1007/s00595-017-1508-8 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Upala S, Panichsillapakit T, Wijarnpreecha K, Jaruvongvanich V, Sanguankeo A. Underweight and obesity increase the risk of mortality after lung transplantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transpl Int. 2016;29:285–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de la Torre MM, Delgado M, Paradela M, Gonzalez D, Fernandez R, Garcia JA, et al. Influence of body mass index in the postoperative evolution after lung transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:3026–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Culver DA, Mazzone PJ, Khandwala F, Blazey HC, Decamp MM, Chapman JT. Discordant utility of ideal body weight and body mass index as predictors of mortality in lung transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24: 137–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harrell FE Jr. Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic Regression, and Survival Analysis. New York: Springer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allen JG, Arnaoutakis GJ, Weiss ES, Merlo CA, Conte JV, Shah AS. The impact of recipient body mass index on survival after lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29:1026–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lederer DJ, Wilt JS, D’Ovidio F, Bacchetta MD, Shah L, Ravichandran S, et al. Obesity and underweight are associated with an increased risk of death after lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:887–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madill J, Gutierrez C, Grossman J, Allard J, Chan C, Hutcheon M, et al. Nutritional assessment of the lung transplant patient: body mass index as a predictor of 90-day mortality following transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2001;20:288–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanasky WF Jr, Anton SD, Rodrigue JR, Perri MG, Szwed T, Baz MA. Impact of body weight on long-term survival after lung transplantation.Chest.2002;121:401–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bozso SJ, Nagendran J, Gill RS, Freed DH, Nagendran J. Impact of obesity on heart and lung transplantation: does pre-transplant obesity affect outcomes? Transplant Proc. 2017;49:344–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruttens D, Verleden SE, Vandermeulen E, Vos R, van Raemdonck DE, Vanaudenaerde BM, et al. Body mass index in lung transplant candidates: a contra-indication to transplant or not? Transplant Proc. 2014;46:1506–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Egan TM, Edwards LB. Effect of the lung allocation score on lung transplantation in the United States. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2016;35:433–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maxwell BG, Levitt JE, Goldstein BA, Mooney JJ, Nicolls MR, Zamora M,et al. Impact of the lung allocation score on survival beyond 1 year. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:2288–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Egan TM, Murray S, Bustami RT, Shearon TH, McCullough KP, Edwards LB, et al. Development of the new lung allocation system in the United States. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(5 Pt 2):1212–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weill D, Benden C, Corris PA, Dark JH, Davis RD, Keshavjee S, et al. A consensus document for the selection of lung transplant candidates: 2014–an update from the Pulmonary Transplantation Council of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015;34:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]