Abstract

Background

Current paradigms of detecting acute kidney injury (AKI) are insensitive and non-specific. Klotho is a pleiotropic protein that is predominantly expressed in renal tubules. In this study, we evaluated the diagnostic and prognostic roles of urine Klotho for AKI following cardiac surgery.

Methods

We conducted a prospective study involving 91 patients undergoing cardiac surgery. AKI was defined according to the AKIN definition. The renal outcomes within 7 days after operation were evaluated. Perioperative levels of urine Klotho and urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) were measured by using ELISA.

Results

Of 91 participants, 33 patients (36.26%) developed AKI. Of these AKI patients, 21 (63.64%), 8 (24.24%), and 4 (12.12%) were staged 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Serum creatinine in AKI patients began to slightly increase at first postoperative time and reached the AKI diagnostic value 1 day after operation.

Postoperative urine Klotho peaked at the first postoperative time (0 h after admission to the intensive care unit (ICU)) in patients with AKI, and was higher than that in non-AKI patients up to day 3. The AUC of detecting AKI for urine Klotho was higher than urine NGAL at the first postoperative time and 4 h after admission to the ICU. In a multivariate model, increased first postoperative urine Klotho may be an independent predictor for AKI occurrence following cardiac surgery. The concentrations of first postoperative urine Klotho were higher in AKI stage 2 and 3 than those in stage 1 (p < 0.05), and were higher in patients with incomplete recovery of renal function than those with complete recovery (p < 0.05).

Conclusions

Urine Klotho may serve as an early biomarker for AKI and subsequent poor short-term renal outcome in patients undergoing cardiac surgery.

Keywords: Acute kidney injury, Cardiac surgery, Klotho, NGAL, Early biomarker

Background

Acute kidney injury (AKI) remains a highly prevalent and serious complication of cardiac surgery. AKI develops in up to 40% of patients who undergo cardiac surgery [1, 2]. Despite decades of research, the mortality of cardiac surgery-associated AKI (CSA-AKI) remains high, even for those patients whose renal function has completely recovered [3]. A major reason for the disappointing outcome is the scarcity of early biomarkers. Current diagnosis of AKI is made based on the changes of serum creatinine (SCr) and urine output, which lack sensitivity and reliability [4]. First, SCr reflects the loss of glomerular filtration function rather than the renal tubular lesions. Second, SCr is vulnerable to several nonrenal factors such as sex, muscle mass, diet and hemodynamic alterations.

Klotho is a multifunctional protein that includes transmembrane and soluble forms [5]. The latter is almost entirely derived from membrane-bound Klotho shedding and has been found in serum, cerebrospinal fluid and urine [6–9]. Soluble Klotho functions as a hormone and plays a role of anti-oxidative stress [10], anti-apoptosis [11], and anti-fibrosis [12]. The renal tubular epithelial cells are the principal cells that contribute to Klotho synthesis and excretion [13, 14]. Klotho regulates transporters and ion channels through autocrine or paracrine to the urinary luminal side [9, 14]. Klotho in the urine can be derived from plasma and interstitium through transcytosis, and can also originate from the tubule through secretion rather than filtered across the glomerular barrier [9, 14].

To date, few studies have focused on the urine Klotho in prediction of AKI. In the present study, we firstly assessed the diagnostic and prognostic performance of urine Klotho in patients undergoing cardiac surgery.

Methods

Patients and samples

Patients who underwent cardiac surgery at the Cardiology Division of the Renji Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiaotong University between 1st October 2012 and 30th June 2013 were enrolled. Patients with chronic kidney disease were excluded [15]. Further exclusion criteria included thyroid disease, preoperative usage of high-dose corticosteroids, pre-existing urinary intact infection, and missing clinical data.

The urine specimens were collected at before surgery and at 0 h, 2 h, 4 h, 1 d, 3 d, and 7 d after admission to the ICU. The blood specimens were collected preoperatively, as well as at 0 h, 1 d, 2 d, 3 d, and 7 d after arrival to the ICU. The first postoperative samples were collected at 0 h after arrival to the ICU within 4 h after surgery. Samples were quickly collected (stayed less than 4 h at 4 °C) and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min. The supernatants were aliquoted and frozen at − 80 °C.

Variable definitions

Data including preoperative characteristics, surgical details, and postoperative complications were collected. Diagnosis and staging of postoperative AKI were according to AKIN criteria [16]. AKI was defined as an increase in SCr of at least 50% or more than 0.3 mg/dl from baseline within 48 h. The short-term renal outcome of AKI patients was evaluated according to changes in renal function on day 7 after operation. Complete recovery was defined as reduction of serum creatinine from the peak to less than 0.3 mg/dl [17]. The eGFR was calculated using Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation [18].

Biomarker assays

We measured urine Klotho using Klotho ELISA kits (Immuno-Biological Laboratories Co, Tokyo, Japan). We measured urine NGAL using NGAL ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA). Samples were used with one freeze/thaw cycle and were detected by a technician with a blind method. The intra- and inter-assay coefficient of variation for Klotho were both< 15% and for NGAL were both< 10%. The results were corrected for urine creatinine excretion.

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and were compared using t test or one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey multiple comparison tests when they were normally distributed. Non-normally distributed continuous data were expressed as medians with interquartile range, and were analyzed using Wilcoxon rank sum test. Categorical variables were analyzed with Pearson χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. We plotted the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve to measure the sensitivity and specificity of urine Klotho and urine NGAL for AKI prediction at different time cutoffs. The area under the ROC (AUC) was calculated to assess the ability of each biomarker to discriminate between patients developing and those not developing AKI after cardiac surgery. We conducted a univariate analysis for the predictors of AKI. Then, those variables with p < 0.05 were candidates for multivariate logistic regression models, including operation time and the first postoperative urine Klotho. In the multivariate analysis, we also adjusted for important covariates that predict AKI in the cardiac surgery setting [19, 20], including baseline SCr.

SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill., USA) and MedCalc version 18.5 (Ostend, Belgium) for windows software were used for analyses. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 103 patients were screened and 91 patients were included in the study. 12 patients were excluded for pre-existing urinary intact infection (n = 2), pre-existing CKD (n = 3), and missing clinical data (n = 7). The mean preoperative estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was 86.89 ± 15.55 ml/min/1.73m2. The average age was 61.79 ± 9.37 years. 33 patients (36.26%) developed AKI at a median time of 24 h post-surgery. 21 (63.64%), 8 (24.24%) and 4 (12.12%) AKI patients were staged into 1, 2 and 3, respectively. No patient required acute dialysis and 2 died before discharge. The baseline characteristics were showed in Table 1. No difference between AKI and non-AKI individuals was found in demographics and the types of operation. Patients who developed AKI had longer operation times than those who did not (5.5 (4.5, 6.25) h vs. 4.5 (4.00, 5.50) h, p < 0.05).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of studied population undergoing cardiac surgery

| All (n = 91) | AKI (n = 33) | Non-AKI (n = 58) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative condition | ||||

| Male, n (%) | 58 (63.7%) | 23 (69.7%) | 35 (63.7%) | 0.372 |

| Age (year)a | 61.79 ± 9.37 | 64.15 ± 9.37 | 60.45 ± 9.18 | 0.070 |

| Weight (kg)a | 62.11 ± 10.29 | 63.36 ± 10.06 | 61.38 ± 10.45 | 0.384 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 33 (36.3%) | 13 (39.4%) | 20 (34.5%) | 0.639 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 14 (15.4%) | 6 (18.2%) | 8 (13.8%) | 0.577 |

| Hyperuricemia, n (%) | 15 (16.5%) | 6 (18.2%) | 9 (15.5%) | 0.742 |

| Cerebrovascular disease, n (%) | 4 (4.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (6.9%) | 0.312 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 6 (6.6%) | 1 (3.0%) | 5 (8.6%) | 0.553 |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 3 (3.3%) | 2 (6.1%) | 1 (1.7%) | 0.615 |

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 13 (14.3%) | 7 (21.2%) | 6 (10.3%) | 0.266 |

| Contrast medium, n (%) | 14 (15.4%) | 7 (21.2%) | 7 (12.1%) | 0.245 |

| Use of ACE inhibitors/ARBs, n (%) | 25 (27.5%) | 9 (27.3%) | 16 (27.6%) | 0.974 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L)b |

129.00 (116.00, 141.00) |

124.00 (113.00, 141.00) |

133.00 (120.00, 141.50) |

0.219 |

| Scr (umol/L)a | 73.77 ± 13.88 | 76.09 ± 15.60 | 72.44 ± 12.76 | 0.230 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73m2)a | 86.89 ± 15.55 | 88.38 ± 14.35 | 84.27 ± 17.37 | 0.228 |

| Intraoperative condition | ||||

| Type of surgery | ||||

| CABG, n (%) | 32 (35.2%) | 10 (30.3%) | 22 (37.9%) | 0.464 |

| Single valve, n (%) | 20 (22.0%) | 6 (18.2%) | 14 (24.1%) | 0.509 |

| Double valve, n (%) | 19 (20.0%) | 9 (27.3%) | 10 (17.2%) | 0.258 |

| CABG plus valve surgery, n (%) | 10 (11.0%) | 4 (12.1%) | 6 (10.3%) | 1.000 |

| CHD, n (%) | 5 (5.5%) | 2 (6.1%) | 3 (5.2%) | 1.000 |

| Aortic aneurysm surgery, n (%) | 5 (5.5%) | 2 (6.1%) | 3 (5.2%) | 1.000 |

| CPB, n (%) | 67 (73.6%) | 27 (81.8%) | 40 (70.2%) | 0.222 |

| Operation time, hb* | 5.00 (4.00, 6.00) | 5.50 (4.50, 6.25) | 4.50 (4.00, 5.50) | 0.002 |

| CPB time (min)b | 84.00 (0.00, 115.00) | 94.00 (56.00, 134.00) | 76.50 (0.00, 112.25) | 0.223 |

| AXC time (min)b | 46.00 (0.00, 69.00) | 55.00 (11.50, 73.50) | 46.00 (0.00, 66.50) | 0.537 |

| Cardiac arrest time (min)b | 48.00 (0.00, 74.00) | 60.00 (13.00, 75.00) | 46.50 (0.00, 70.00) | 0.526 |

| Transfusion > 400 ml, n (%) | 10 (11.0%) | 4 (12.1%) | 6 (10.3%) | 1.000 |

aData were presented as means ± standard deviation (SD) and the difference were calculated using t test. bData were presented as medians (IOR, interquartile range) and were analyzed using non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were presented as number (percentage of the column total) and were analyzed using Pearson χ2 test. *p < 0.05

ACE Angiotensin-converting enzyme, ARB Angiotensin receptor blockers, SCr Serum creatinine, eGFR Estimated glomerular filtration rate, CABG Coronary artery bypass grafting, CHD Congenital heart disease, CPB Cardiopulmonary bypass, AXC Aortic cross clamp

Perioperative biomarkers concentrations

There was no difference in preoperative levels of Scr, urine Klotho (uKlotho) and urine NAGL (uNGAL) between patients with and without AKI. Serum creatinine in AKI patients began to slightly increase at first postoperative time (88.00 (78.35, 111.30) umol/L vs. preoperative: 76.80 (64.20, 90.45) umol/L, p < 0.01) and reached the AKI diagnostic value 1 day after arrival to the ICU (Fig. 1a). The levels of urine Klotho peaked at first postoperative time in patients with AKI and were 3 times higher than that before surgery (1.69 (1.02, 2.68) ng/umol vs. 0.41 (0.30, 0.65) ng/umol, p < 0.001, Fig. 1b). Further, urine Klotho levels in AKI patients were strikingly higher than those in non-AKI patients at the first postoperative time (1.69 (1.02, 2.68) ng/umol vs. 0.52 (0.23, 0.84) ng/umol, p < 0.01), and remained significantly higher up to day 3 postoperatively. The levels of urine NGAL in patients who developed AKI peaked at 2 h after admission to the ICU, but recovered at 4 h. Urine NGAL in patients who developed AKI was significantly higher than those who did not at 2 h (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

Perioperative levels of biomarkers in AKI and non-AKI patients. Concentrations of (a) serum creatinine, (b) urine Klotho, and (c) urine NGAL at indicated time points after cardiac surgery. The urine biomarkers were corrected for urine creatinine excretion. Data were presented as median with interquartile range. #P-value < 0.05, ##p-value < 0.01, and ###p-value < 0.001 vs. non-AKI patients. *P-value < 0.05, **p-value < 0.01, and ***p-value < 0.001 vs. the preoperative levels

AUC analyses for cardiac surgery-associated AKI

We evaluated the AUCs for biomarkers in predicting AKI at indicated time points. As shown in Table 2, the AUC for uKlotho at the first postoperative time was 0.86 with the cutoff 0.86 ng/umol (sensitivity 93.9%, specificity 75.9%). Urine Klotho had higher AUCs than uNGAL at the first postoperative time and 4 h after arrival to the ICU (p < 0.001).

Table 2.

AUC of biomarkers to predict AKI after cardiac surgery

| AUC (95% CI) | Cut-off (Sensitivity, Specificity) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urine Klotho (ng/umol) | |||

| The first postoperative | 0.86*** (0.78, 0.94) | 0.86 (93.9, 75.9%) | < 0.001 |

| 2 h admission to the ICU | 0.85 (0.76, 0.94) | 0.82 (87.5, 77.6%) | < 0.001 |

| 4 h admission to the ICU | 0.78*** (0.76, 0.94) | 0.70 (90.6, 62.1%) | < 0.001 |

| Urine NGAL (ng/umol) | |||

| The first postoperative | 0.59 (0.46, 0.71) | 4.39 (72.7, 56.6%) | 0.177 |

| 2 h admission to the ICU | 0.78 (0.68, 0.88) | 4.49 (87.9, 71.7%) | < 0.001 |

| 4 h admission to the ICU | 0.57 (0.44, 0.70) | 4.64 (57.6, 64.2%) | 0.285 |

AUC Area under the ROC, NGAL Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin

***P < 0.001 compared with the AUCs of urine NGAL at indicated time points

The first postoperative urine klotho was associated with the occurrence of AKI

As shown in Table 3, the first postoperative uKlotho was associated with AKI occurrence with unadjusted and adjusted odds ratio (OR) 3.36 (95% CI, 1.86 to 6.07) and 3.43 (95% CI, 1.87 to 6.28), respectively. The data also showed that the risk of AKI occurrence increased by 1.5 times for each additional hour of operation.

Table 3.

Association of first postoperative urine Klotho with AKI

| AKI (33/91) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted OR | Adjusted OR | |

|

Urine Klothoa (per 1 ng/umol increase) |

3.36 (1.86–6.07)*** | 3.43 (1.87–6.28)*** |

|

operation timeb (per 1 h increase) |

1.58 (1.14–2.20)** | 1.52 (1.03–2.24)* |

***p < 0.001

Urine Klotho (continuous), operation time (continuous)

aAdjusted for operation time, baseline SCr

bAdjusted for baseline SCr and the first postoperative urine Klotho

Perioperative levels of uKlotho among different stages of AKI

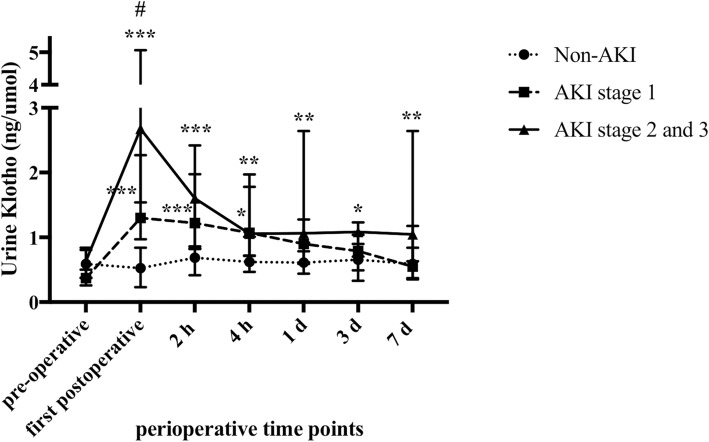

Compared with non-AKI patients, patients with AKI stage 1 had significantly higher levels of uKlotho at the first postoperative time (Fig. 2). Patients who experienced AKI stage 2 and 3 had higher levels of first postoperative uKlotho than patients with stage 1 (2.68 (1.54, 5.06) ng/umol vs. 1.30 (0.97, 2.27) ng/umol, P < 0.05). Levels of uKlotho in patients with AKI stage 2 and 3 were markedly higher than that in non-AKI patients at the first postoperative time and remained higher up to day 7 (P < 0.01).

Fig. 2.

Perioperative levels of uKlotho among different stages of AKI. Patients were grouped as non-AKI, AKI stage 1, and AKI stage 2 and 3. The levels of uKlotho were analyzed. Urine Klotho was corrected for urine creatinine excretion. Data were presented as median with interquartile range. #P-value < 0.05 vs. AKI stage 1 group. *P-value < 0.05, **p-value < 0.01, and ***p-value < 0.001 vs. non-AKI patients

Perioperative levels of uKlotho among non-AKI, AKI with complete recovery, and AKI with incomplete recovery

As shown in Fig. 3, 21 (63.63%) AKI patients had complete recovery of renal function on day 7. The levels of first postoperative uKlotho were 0.52 (0.23, 0.84) ng/umol, 1.3 (0.97, 2.34) ng/umol, and 2.58 (1.41, 3.60) ng/umol in patients with non-AKI, complete recovery AKI, and incomplete recovery AKI, respectively (p < 0.01).

Fig. 3.

Perioperative levels of uKlotho among non-AKI, AKI with complete recovery, and AKI with incomplete recovery. Levels of uKlotho among 3 groups were analyzed. Data were presented as median with interquartile range. #P-value < 0.05 vs. AKI with complete recovery. *P-value < 0.05, **p-value < 0.01, and ***p-value < 0.001 vs. non-AKI patients

Discussion

To our knowledge, we are the first to examine the time course of uKlotho among adults undergoing cardiac surgery. We found that the elevated first postoperative uKlotho may be an early predicator for the occurrence of CSA-AKI. Further, urine Klotho in patients with AKI stage 2 and 3 was higher than that in patients with AKI stage 1 at the first postoperative time. Urine Klotho in AKI patients with incomplete recovery of renal function was significantly higher than that in patients with complete recovery at the first postoperative time.

AKI following cardiac surgery is a world health issue. Serum creatinine and urine output remains the gold standard for clinical diagnosis of AKI, although both were believed as unspecific markers for kidney injury. Novel biomarkers including NGAL, KIM-1 and interleukin-18 (IL-18) were evaluated for early diagnosis of AKI. Unlike Klotho that mainly expressed in kidney tubule, NGAL and IL-18 are nonspecific for kidney and are expressed in variety of tissues [4, 21]. Moreover, large, prospective, multicenter trails failed to show troponin-like diagnostic performance of plasma NGAL, urine NGAL, urine Kim-1, and urine IL-18 for AKI detecting with AUCs of less than 0.77 [22, 23]. Thus, efforts to validate potential markers are needed.

In animal experiments, Klotho deficiency in kidney tissues has been observed in both acute and chronic kidney injuries [24, 25]. More recently, a small study with 35 patients observed reduced serum Klotho in adults who developed AKI after cardiac surgery [26]. However, no significant difference of serum Klotho was found between patients with and without AKI on 1 day postoperatively and thereafter. Moreover, their study did not evaluate the change of urine Klotho and did not comment on the severity or renal outcome of AKI.

We firstly showed that uKlotho quickly increased as early as transferred to the ICU in patients who developed AKI later. Urine Klotho kept significantly higher in AKI patients than non-AKI patients until day 3 after surgery. The elevation of uKlotho occurred earlier than that of uNGAL demonstrated in the present cohorts and our previous data [27]. However, there was no difference in preoperative levels of uKlotho between patients with and without AKI. The early performance of urine Klotho may allow earlier detection of AKI and thus increase the success of therapeutic interventions.

To date, only two studies had examined uKlotho levels in patients or rodents with AKI. Isidro and his colleagues [28] examined the levels of uKlotho at 12 h post-cardiac surgery and showed a similar elevation of that in AKI patients (n = 15) compared with the healthy volunteers (n = 10). When comparing to the non-AKI (n = 15) group, the uKlotho levels in AKI patients increased but without significance. However, our results conflict with the reports from Hu et al. [24]. They found that urine Klotho levels in 17 AKI patients were significantly lower than that in 14 healthy controls by using immunoblotting assay. There are several reasons for the conflicted results. First, Hu did not describe the methods of pretreatment and the collecting time of urine samples. Klotho is unstable in urine and any additional freeze-thaw cycle decreases Klotho concentrations [29]. In the present study, urine samples were frozen at − 80 °C and were thawed for the first time for measurement of Klotho. Furthermore, uKlotho in patients with AKI was comparable with that in patients without AKI on 7 days post-surgery. Thus, a delayed collecting time may lead to different results. Second, the different causes of AKI may also lead to the contrary results. In the study of Hu et al., the causes of AKI are heterogeneous including sepsis, hypertension, CKD, nephrontoxin, pre-renal and others. Different measuring assays and fewer patients may also contribute the difference. Further researches with large sample size, multi-center and extensive time course are needed to clarify the change pattern of uKlotho.

Histologically, proximal tubular epithelial cells lose their brush border membrane as well as the Klotho protein expressed in the apical brush border, which may result in an acute increase of uKlotho at early AKI. With the progression of AKI, renal tubular epithelial cells were necrotic and exfoliated, accompanied with shedding of Klotho protein. This may contribute to the continuous elevation of uKlotho during AKI. We have previously showed similar phenomenon in the mouse model of AKI induced by renal ischemic-reperfusion injury [30]. Under these circumstances, the increase of uKlotho may indicate the severity of tubule injury. In support of this, we found that uKlotho was strongly associated with the occurrence of CSA-AKI and was significantly higher in AKI stage 2 and 3 than in stage 1.

Our study has several limitations. First, The present study is a single center study with a relatively small number of patients and short follow-up. Second, we did not compare the performance of predicting AKI between Klotho and other biomarkers besides NGAL. Third, the time points of uNGAL detection are insufficient. Additionally, the use of creatinine as a reference standard for biomarker assessment is imperfect for the known insensitivity and non-specificity.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study implies that first postoperative uKlotho may be an early predictor for the occurrence of AKI among patients undergoing cardiac surgery. The first postoperative uKlotho may be associated with the severity and prognosis of AKI. This may help to early identify at-risk patients before the progression to overt kidney injury and implement early interventions.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ACE

Angiotensin-converting enzyme

- AKI

Acute kidney injury

- AKIN

Acute Kidney Injury Network

- ARB

Angiotensin receptor blockers

- AUC

Area under the ROC

- AXC

Aortic cross clamp

- CABG

Coronary artery bypass grafting

- CHD

Congenital heart disease

- CKD

Chronic kidney disease

- CKD-EPI

Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration

- CPB

Cardiopulmonary bypass

- CSA-AKI

Cardiac surgery-associated acute kidney injury

- eGFR

Estimated glomerular filtration rate;

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- K/DOQI

Kidney Disease Outcome Quality Initiative

- Kim-1

Kidney injury molecule-1

- NGAL

Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin

- OR

Odds rate

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- SCr

Serum creatinine

- UUO

Unilateral ureteral obstruction

Authors’ contributions

YQ analyzed and interpreted the patient data, and drafted the manuscript. LC performed data collection and biomarkers examination. YY conceived and designed the experiments and contributed reagents and materials. RL, MZ, and SX participated in data collection. ZN contributed reagents and materials. LG critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, and contributed reagents and materials. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The design of the study and ELISA kits were supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81170678, NO.81470918). Experimental consumables, data collection and analysis were supported by Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (No.15ZR1425900) and Shanghai science and technology commission (No.17695840500).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethical review board of Renji Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiaotong University. All of the patients were given and accepted written informed consent prior to enrollment.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yingying Qian and Lin Che contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Yingying Qian, Email: qyyconcer@126.com.

Lin Che, Email: zhenshuiwuxianga@126.com.

Yucheng Yan, Email: yucheng.yan@163.com.

Renhua Lu, Email: lurenhua1977@hotmail.com.

Mingli Zhu, Email: millionzhu525@126.com.

Song Xue, Email: xuesong64@163.com.

Zhaohui Ni, Email: profnizh@126.com.

Leyi Gu, Phone: +86-021-68383964, Email: guleyi@aliyun.com.

References

- 1.Tuttle KR, Worrall NK, Dahlstrom LR, Nandagopal R, Kausz AT, Davis CL. Predictors of ARF after cardiac surgical procedures. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41(1):76–83. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2003.50025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosner MH, Okusa MD. Acute kidney injury associated with cardiac surgery. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(1):19–32. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00240605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hobson CE, Yavas S, Segal MS, Schold JD, Tribble CG, Layon AJ, et al. Acute kidney injury is associated with increased long-term mortality after cardiothoracic surgery. Circulation. 2009;119(18):2444–2453. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.800011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Makris K, Kafkas N. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in acute kidney injury. Adv Clin Chem. 2012;58:141–191. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394383-5.00012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu Y, Sun Z. Molecular basis of klotho: from gene to function in aging. Endocr Rev. 2015;36(2):174–193. doi: 10.1210/er.2013-1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mencke R, Harms G, Moser J, van Meurs M, Diepstra A, Leuvenink HG, et al. Human alternative Klotho mRNA is a nonsense-mediated mRNA decay target inefficiently spliced in renal disease. JCI Insight. 2017;2(20). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Imura A, Iwano A, Tohyama O, Tsuji Y, Nozaki K, Hashimoto N, et al. Secreted klotho protein in sera and CSF: implication for post-translational cleavage in release of klotho protein from cell membrane. FEBS Lett. 2004;565(1–3):143–147. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.03.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barker SL, Pastor J, Carranza D, Quinones H, Griffith C, Goetz R, et al. The demonstration of alphaKlotho deficiency in human chronic kidney disease with a novel synthetic antibody. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30(2):223–233. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu MC, Shi M, Zhang J, Pastor J, Nakatani T, Lanske B, et al. Klotho: a novel phosphaturic substance acting as an autocrine enzyme in the renal proximal tubule. FASEB J. 2010;24(9):3438–3450. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-154765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Y, Kuro-o M, Sun Z. Klotho gene delivery suppresses Nox2 expression and attenuates oxidative stress in rat aortic smooth muscle cells via the cAMP-PKA pathway. Aging Cell. 2012;11(3):410–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00796.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin Y, Sun Z. Antiaging gene klotho attenuates pancreatic beta-cell apoptosis in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2015;64(12):4298–4311. doi: 10.2337/db15-0066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu MC, Shi M, Gillings N, Flores B, Takahashi M, Kuro OM, et al. Recombinant alpha-klotho may be prophylactic and therapeutic for acute to chronic kidney disease progression and uremic cardiomyopathy. Kidney Int. 2017;91(5):1104–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindberg K, Amin R, Moe OW, Hu MC, Erben RG, Ostman Wernerson A, et al. The kidney is the principal organ mediating klotho effects. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(10):2169–2175. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013111209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu MC, Shi M, Zhang J, Addo T, Cho HJ, Barker SL, et al. Renal production, uptake, and handling of circulating alphaKlotho. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(1):79–90. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014101030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National KF. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39(2 Suppl 1):S1–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, Warnock DG, et al. Acute kidney injury network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2007;11(2):R31. doi: 10.1186/cc5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xie Y, Wang Q, Wang C, Qi C, Ni Z, Mou S. High urinary excretion of kidney injury molecule-1 predicts adverse outcomes in acute kidney injury: a case control study. Crit Care. 2016;20:286. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1455-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, 3rd, Feldman HI, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Che M, Li Y, Liang X, Xie B, Xue S, Qian J, et al. Prevalence of acute kidney injury following cardiac surgery and related risk factors in Chinese patients. Nephron Clin Pract. 2011;117(4):c305–c311. doi: 10.1159/000321171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thakar CV, Arrigain S, Worley S, Yared JP, Paganini EP. A clinical score to predict acute renal failure after cardiac surgery. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(1):162–168. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004040331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siew ED, Ware LB, Ikizler TA. Biological markers of acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(5):810–820. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010080796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parikh CR, Coca SG, Thiessen-Philbrook H, Shlipak MG, Koyner JL, Wang Z, et al. Postoperative biomarkers predict acute kidney injury and poor outcomes after adult cardiac surgery. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(9):1748–1757. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010121302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parikh CR, Thiessen-Philbrook H, Garg AX, Kadiyala D, Shlipak MG, Koyner JL, et al. Performance of kidney injury molecule-1 and liver fatty acid-binding protein and combined biomarkers of AKI after cardiac surgery. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(7):1079–1088. doi: 10.2215/CJN.10971012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu MC, Shi M, Zhang J, Quinones H, Kuro-o M, Moe OW. Klotho deficiency is an early biomarker of renal ischemia-reperfusion injury and its replacement is protective. Kidney Int. 2010;78(12):1240–1251. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shimamura Y, Hamada K, Inoue K, Ogata K, Ishihara M, Kagawa T, et al. Serum levels of soluble secreted alpha-klotho are decreased in the early stages of chronic kidney disease, making it a probable novel biomarker for early diagnosis. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2012;16(5):722–729. doi: 10.1007/s10157-012-0621-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu YJ, Sun HD, Chen J, Chen MY, Ouyang B, Guan XD. Klotho: a novel and early biomarker of acute kidney injury after cardiac valve replacement surgery in adults. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(5):7351–7358. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Che M, Xie B, Xue S, Dai H, Qian J, Ni Z, et al. Clinical usefulness of novel biomarkers for the detection of acute kidney injury following elective cardiac surgery. Nephron Clin Pract. 2010;115(1):c66–c72. doi: 10.1159/000286352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Torregrosa I, Montoliu C, Urios A, Gimenez-Garzo C, Tomas P, Solis MA, et al. Urinary klotho measured by ELISA as an early biomarker of acute kidney injury in patients after cardiac surgery or coronary angiography. Nefrologia. 2015;35(2):172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.nefro.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adema AY, Vervloet MG, Blankenstein MA, Heijboer AC. Alpha-klotho is unstable in human urine. Kidney Int. 2015;88(6):1442–1444. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qian Y, Guo X, Che L, Guan X, Wu B, Lu R, et al. Klotho reduces necroptosis by targeting oxidative stress involved in renal ischemic-reperfusion injury. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;45(6):2268–2282. doi: 10.1159/000488172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.