Abstract

Background

Cardiac stem cells (CSCs) exhibit age-dependent characteristics. Cited2 has been implicated in the regulation of heart development; however, there is little known about how Cited2 affects CSC aging.

Results

Cited2 mRNA and protein level was downregulated in aging heart tissue and CSCs. Old (O)-CSCs showed decreased differentiation and proliferation capacities as compared to Young (Y)-CSCs, the decrease in cell proliferation, increase in apoptosis, and cell cycle arrest in G0/G1 phase in CSCs are mediated by knocdown CITED2expression in (Y)-CSCs.

Conclusions

Cited2 plays an important role in cell cycle progression and in maintaining the balance between CSC proliferation and apoptosis in the process of aging without influencing cell fate decisions. These findings have important implications for cell-based therapies for heart repair.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12860-019-0207-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Cardiac stem cells, Cited2, Aging, Apoptosis, Proliferation

Background

Cyclic AMP response element binding protein(CREB) binding protein (CBP)/p300-interacting transactivator with ED-rich tail (CITED)2 is a transcriptional regulator that is critical for mice cardiac development and embryogenesis, loss of Cited2 during gestation is lethal [1, 2]. Cited2 deficiency in mice causes defects in arterial and ventricular septum and outflow tracts [1, 3, 4], while deletion of Cited2 in mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs) results in aberrant mitochondrial morphology, reduced glucose oxidation, increased glycolysis, and defective differentiation [5]. Cited2 was identified for the maintenance of stem cell function, indicated to the maintenance of self-renewal of mouse embryonic stem cells through the regulation of Nanog expression [6], and was shown to regulate quiescence and apoptosis in adult hematopoietic stem cells [7] and regulate hematopoiesis in the fetal and adult liver [8]. Cited2 was also found to play a critical role in cardiac development, the Cited2(−/−) mice developed laterality defects, including right isomerism, abnormal cardiac looping and hyposplenia [1, 2], and we have shown that Cited2 expression was reduced in aged tendon-derived stem/progenitor cells, which may also influence TSPC differentiation [9].Other reports indicated that the downregulation of Cited2 in aged TSPC contribute to TGFβ-mediated senescence [10]. We also reported significant changes in CSC stemness characteristics with advancing age [11]. However, whether Cited2 controls CSC multipotency, differentiation, and aging remains unclear.

To address this issue, the present study investigated the role of Cited2 in the maintenance of stemness and multipotency in aging murine CSCs using a gene targeting approach.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals and tissue collection

All procedures involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, Guangxi Normal University, Guilin, China. Young and old CSCs (Y- and CSCs, respectively) were prepared and cultured as previously described [11, 12].

Microarray gene expression data

Gene expression data were obtained by microarray using the Affymetrix Mouse Genome 2.0 Array (Santa Clara, CA, USA). After quality assessment, three Y-CSC and three O-CSC samples were processed and normalized with the Robust Multichip Average [13] method. Details regarding the samples, mRNA processing and hybridization, and data access are described in our other papers [11, 12].

A detailed description of the gene expression analysis of C57BL/6 J mouse heart tissues with aging (2–3 months, 4 months, and 18 months; also based on the Affymetrix Mouse Genome 2.0 Array) and sample inclusion and exclusion criteria have been previously published [13, 14]. Corresponding CEL files are publicly available on the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession numbers GSE43556, GSM1024592–94, and GSE7196).

In the present study, we used data from heart tissue samples at three ages (2–3, 4, and 18 months) and cardiac stem cell samples from mice at two ages (2–3 and 20–24 months). Raw data were subjected to quantile normalization and then analyzed in GeneSpring GX (zcomSilicon Genetics, Redwood City, CA, USA). Differentially expressed mRNAs were compared by analysis of variance and significance was evaluated with Fisher’s exact test, with a false discovery rate < 0.05 and fold change ≥1.5. To obtain gene expression profiles over the course of aging and identify the most probable clusters generating the observed aging series, the Series Test of Cluster (STC) algorithm was used [15] and STC-Gene Ontology (GO) analysis was performed. Data normalization and analyses were performed on the web (https://www.gcbi.com.cn/gclib/html/index).

Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR and droplet digital (dd)-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from heart tissues and CSCs using TRIzol reagent (invitrogen) according to standard protocols and reversed transcribed using the OneStep RT-PCR kit. Heart tissue and CSC cDNA served as the template for RT-PCR and dd-PCR, respectively, which were performed using the primers listed in Table 1. When the number of CSCs was small, we used dd-PCR to measure Cited2 expression. The reaction was carried out as previously described [16] in a 20-μl volume containing 10 μl of 2× EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), 8 μl diluted cDNA, and primer sets. Reactions were run in triplicate. Cited2 expression level was calculated relative to that of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Table 1.

Sequences of Cited2-shRNA and the primers

| Primer | Forward primer 5′ → 3′ | Reverse primer 5′ → 3′ |

|---|---|---|

| Cited2 (for dd PCR and RT-PCR) | AAATCGCAAAGACGGAAGGA | TGAACTGGGAGTTGTTAAACCT |

| Cited2-shRNA1 | TGGCAGACCATATGATGGCCATGAA | |

| Cited2-shRNA2 | CCCACAACCACTACATGCCGGATTT | |

| Cited2-shRNA3 | GTCAGCTGTTGACTCGGTTAA | |

| Cited2-cDNA | tatcgaattc(EcoRI)ATGGCAGACCATATGATGGCCATGAAC | tatcggatcc(BamHI)ACAGCTGACTCTGCTGGGCTGCT |

| GAPDH | GCTGCCCAGAACATCATCCCT | TGAAGTCGCAGGAGACAACC |

Immunoblotting

The cells were prepared using RIPA buffer (Cell Signaling Technology) supplemented with 1 mM PMSF and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (0.5 mM imidazole, 0.25 mM sodium fluoride, 0.3 mM sodium molybdate, 0.25 mM sodium orthovanadate, and 1.0 mM sodium tartrate). Protein concentrations were measured using a modified Lowry assay. 25–40 μg protein were separated by SDS-PAGE gel (10% acrylamide) and transferred onto PVDF membrane. Membranes were blocked in 5% non-fat dry milk (w/v) for 1 h then treated with primary antibody overnight at 4 °C. The antibody GAPDH (1:1000) and IgG (1:10000) from Cell Signaling Technology, antibody CITED2from Abcam (1:1000).

Lentivirus construction and infection

For knockdown experiments, oligonucleotides targeting Cited2 were used to clone short hairpin (sh)RNA-encoding sequences into the hU6-MCS-PGK-EGFP lentiviral RNAi vector (Hanbio, Shanghai, China). To generate the overexpression construct, Cited2 cDNA cloned by PCR using the primers listed in Table 1 was inserted into the CMV-MCS-IRES-EGFP lentiviral vector (Hanbio). Recombinant knockdown and overexpression lentiviral vectors were produced by co-transfection of 293 T cells with the pSPAX2, pMD2G, and pHBLV plasmids using LipoFiter reagent (Hanbio). Lentivirus-containing supernatant was collected 48 h after transfection and passed through a 0.45-μm cellulose acetate filter (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Recombinant lentiviruses were concentrated by ultracentrifugation for 2 h at 72,000×g.

For lentiviral infection, CSCs were cultured until they reached ~70% confluence, and the culture medium was removed before infection. The cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and treated with the virus-containing medium (multiplicity of infection ~ 50, combined with 5 μg/ml polybrene). After 24 h, the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium. Most of the CSCs (> 80%) expressed enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) 72 h after transduction. The empty vector encoding EGFP was used as a negative control. CSCs were harvested 3 days after viral infection and Cited2 expression level was evaluated with dd-PCR.

Stem cell differentiation and immunofluorescence analysis

After 3 days viral infection, lentivirus-infected and negative control CSCs were cultured in cardiomyocyte, smooth muscle cell, and endothelial differentiation induction medium for 14 days, then examined for the expression of cardiac lineage-specific markers by immunocytochemistry as previously described [11, 12].

Analysis of cell cycle, proliferation, and apoptosis

Y−/O-CSCs were transducted with Cited2-shRNA, Cited2-cDNA, and negative control lentiviral particles; 48 h later, cell apoptosis was detected by flow cytometry using an Annexin V-phycoerythrin (PE) Apoptosis Detection kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The percentage of apoptotic cells was counted as the sum of annexin V-PE single-positive and annexin V-PE/7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) double-positive cells. The 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) assay was performed to assess cell proliferation 48 h after lentiviral infection by incubating the cells in 10 μmol/l EdU solution (RiboBio, Guangzhou, China) for 2 h followed by flow cytometry analysis. Cells cycle analysis was performed with the 7-AAD Flow Cytometry Assay kit (Ebioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The methods have been described in detail elsewhere [11, 12].

Results

Cited2 mRNA expression during heart and CSC aging

We compared mRNA expression profiles in heart tissue at 2–3, 4, and 18 months. A total of 5506 differentially expressed genes were identified by pairwise comparisons among groups, with a false discovery rate < 0.05 and fold change ≥1.5 in at least one of the pairwise comparisons. Hierarchical clustering of genes that were differentially expressed during heart tissue aging was performed (Additional file 1: Figure S1). STC and STC-GO analyses of the most probable set of clusters generating the observed aging series revealed 16 clusters of differentially expressed genes (Additional file 1: Figure S2) with six significant cluster profiles (profiles 14, 15, 10, 11, 9, and 1); a striking observation was made in three significant cluster profiles (profiles 11, 9, and 1). Considering that the gap in age between 2 and 3 and 4 months is small, we assumed that the gene expression profiles between these two groups would be similar, and therefore focused on cluster profiles 14 and 15 (Additional file 1: Figure S3A). Genes that were downregulated with heart aging in profile 15 (0, 0, − 1) included those related to transport, regulation of transcription, and cell differentiation (Additional file 1: Figure S3-B). The differentially expressed genes with aging in STC profile15 were listed in Additional file 2 and Cited2 expression level was similar between 2 and 3 and 4 months mice, downregulation in 18 month mice heart (Additional file 2: Table S1).

The microarray analysis revealed that Cited2 expression was downregulated during aging in heart tissue and cardiac stem cells (CSCs) and may play as a core senescence and regulator in CSCs.

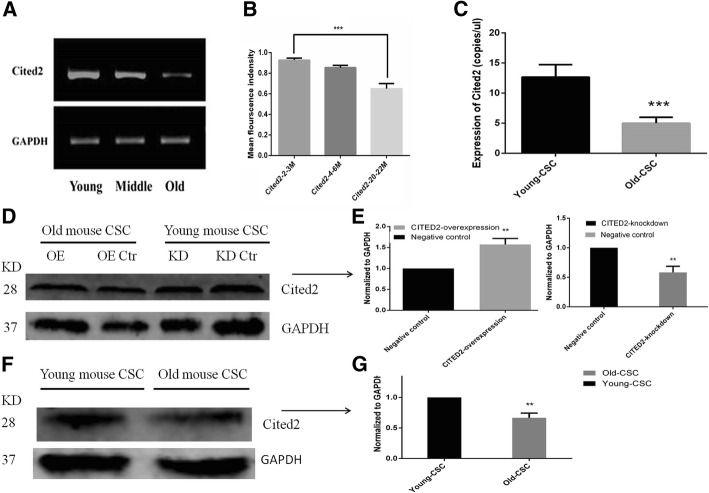

Cited2 is downregulated in O-CSCs as compared to Y-CSCs

We examined Cited2 gene expression level in 2–3, 4–6, and 20–22 month mouse heart tissues by RT-PCR and found that Cited2 level decreased with aging (Fig. 1a, b). Cited2 mRNA expression was also lower in O-CSCs than in Y-CSCs (P < 0.01; Fig. 1c).The CITED2 protein level was confirmed by western blotting, CITED2 protein was also lower in O-CSCs than in Y-CSCs (P < 0.01; Fig. 1f, g).

Fig. 1.

Age-dependent expression of Cited 2 in mice heart tissues and CSCs. a. RT-PCR for Cited2 mRNA expression in Young (2–3 months), Middle (4–6 months) and Old (20–22 months) mice heart tissues. b. The analysis of RT-PCR for Cited2 mRNA expression. c. DD-PCR for Cited2 mRNA expression in Young (2–3 months) and Old (20–22 months) CSCs. d-g. Immunoblotting of CITED2 protein levels in lentivector transduction groups and CSCs groups. OE represented Old CSCs transducted with lentiviral particles of Cited2-cDNA, KD represented Young CSCs transducted with lentiviral particles of Cited2-shRNA3, the control was transducted with empty lentivector. Data were from three independent experiments and presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was implemented by GraphPad Prism 5, *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001, Old-CSCs contrast to Young-CSCs

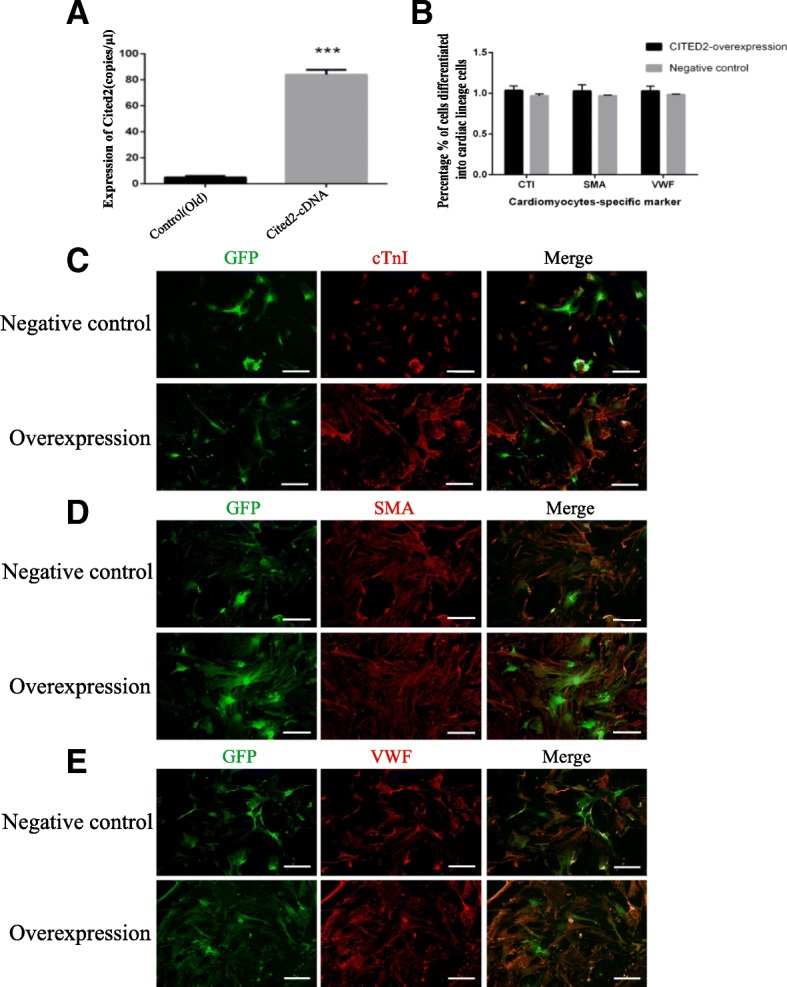

The differentiation characteristics of O-CSCs with CITED2overexpression

To examine the role of Cited2 in aging mouse CSCs, we used a lentiviral vector to stably express Cited2 in O- and Y-CSCs, with cells transducted with empty vector serving as a negative control. Transduction with the Cited2-cDNA vector for 48 h increased Cited2 mRNA and protein levels in O-CSCs as compared to the negative control group (Figs. 1d, e, 2a). We then assessed the potential of O-CSCs to differentiate into cardiomyocyte, smooth muscle, and endothelial lineages upon transduction with Cited2-cDNA or control vector. After 14 days of incubation in the induction medium, lineage-specific markers were analyzed with immunocytochemistry. We have quantified the number of cells differentiated Markers and GFP, calculated the percentage % of cells differentiated into cardiac lineage cells, over the cells expressing GFP. Cells positive for cardiac troponin (cTn)I, α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), and Von Willebrand factor (VWF) were detected in both groups, with no difference in expression levels between them (Fig. 2b). The morphology of the differentiated cells were not observed (Fig. 2c-e). These results suggest that Cited2 has no effect on the differentiation of O-CSCs.

Fig. 2.

The affect of Cited2 overexpression on differentiation in Old cardiac stem cells. a:DD-PCR of Cited2 mRNA expression for lentivector transduction. The control was transducted with empty lentivector. Overexpression represented Old CSCs transducted with lentiviral particles of Cited2-cDNA; Data were from three independent experiments and presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was implemented by GraphPad Prism 5, *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001. b: The differentiation efficiency of CSCs from Cited2 overexpression and negative control group. The percentage % of cells differentiated into cardiomyocytes was calculated cardiomyocytes marker cells among total GFP cells based on a mean of five independent experiments. Statistical analysis was implemented by GraphPad Prism 5, *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001, contrast to control. c-e: Immunofluorescence staining (red) of cardiomyocytes-specific marker-cTnI; smooth muscle marker-α-SMA and enodthelial cell marker-VWF; transduction CSCs [17] staining with GFP; then merged images. Overexpression represented Old CSCs transfected with lentiviral particles of Cited2-cDNA; The control was transducted with empty lentivector. GFP-green is represented lentivirus vector. Scale bars, 50 μm. Each experiment is repeated five times, and the picture represents a single result

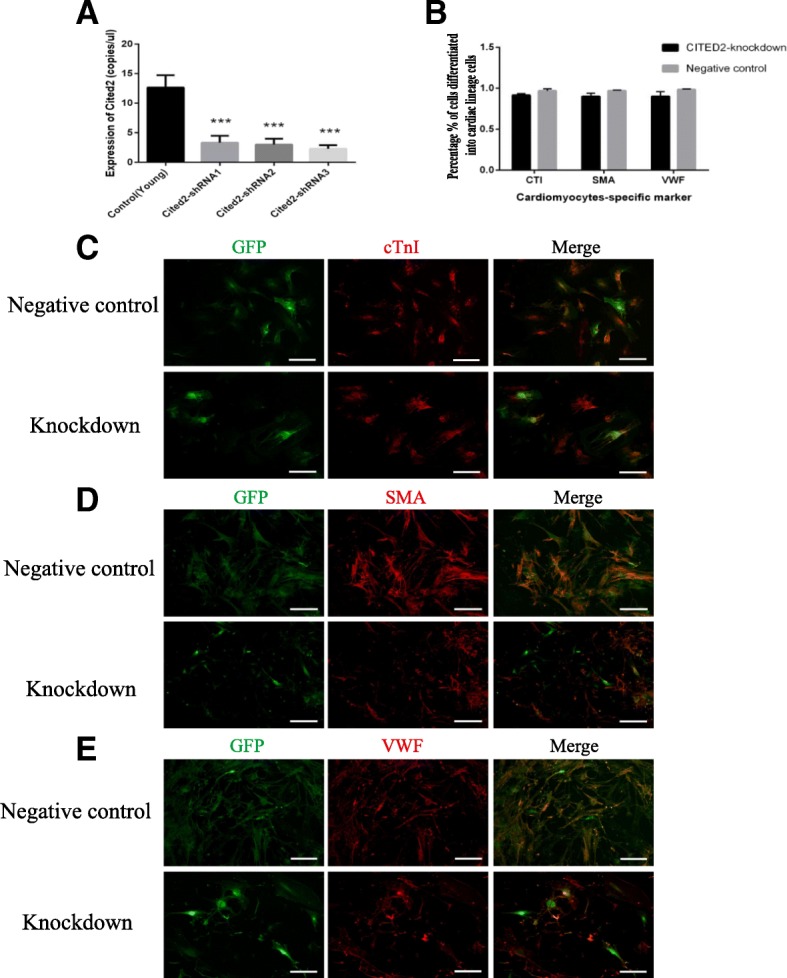

The differentiation characteristics of Y-CSCs with Cited2 knockdown

To further investigate the role of Cited2 in mouse CSC aging, we knocked down Cited2 expression in Y-CSCs using three different shRNAs (sequences are listed in Table 1). All three shRNA vectors decreased Cited2 mRNA level 48 h after transduction (Fig. 3a). Y-CSCs transducted with empty vector served as a negative control. The CITED2 protein level was confirmed by western blotting, CITED2 protein was also lower in lentivirus Cited2 -shRNA3-transduced Y-CSCs (P < 0.01; Fig. 1d, e). We then evaluated the potential for differentiation into cardiomyocyte, smooth muscle, and endothelial lineages in lentivirus Cited2-shRNA3-transduced Y-CSCs. After 14 days of incubation in the induction medium, lineage-specific markers were analyzed by immunocytochemistry. Cells positive for cTnI, α-SMA, and VWF were detected in both Cited2 knockdown and control groups in similar numbers (Fig. 3b), indicating that Cited2 does not influence the differentiation potential of Y-CSCs.

Fig. 3.

The affect of Cited2 knockdown on differentiation in Young cardiac stem cells. a: DD-PCR of Cited2 mRNA expression for lentivector transduction. The control was transducted with empty lentivector. Knockdown represented Young CSCs transducted with lentiviral particles of Cited2-shRNA1, Cited2-shRNA2 and Cited2-shRNA3; Data were from three independent experiments and presented as mean ± SD.Statistical analysis was implemented by GraphPad Prism 5, *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001, contrast to control. b: The differentiation efficiency of CSCs from Cited2 knockdown and negative control group. The percentage % of cells differentiated into cardiomyocytes was calculated cardiomyocytes marker cells among total GFP cells based on a mean of five independent experiments. Statistical analysis was implemented by GraphPad Prism 5, *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001, contrast to control. c-e: Immunofluorescence staining (red) of cardiomyocytes-specific marker-cTnI; smooth muscle marker-α-SMA and enodthelial cell marker-VWF; transfection CSCs staining with GFP; then merged images. Each experiment is repeated five times, and the picture represents a single result. Knockdown represented Young CSCs transfected with lentiviral particles of Cited2-shRNA3; The control was transducted with empty lentivector. GFP-green is represented lentivirus vector. Scale bars, 50 μm

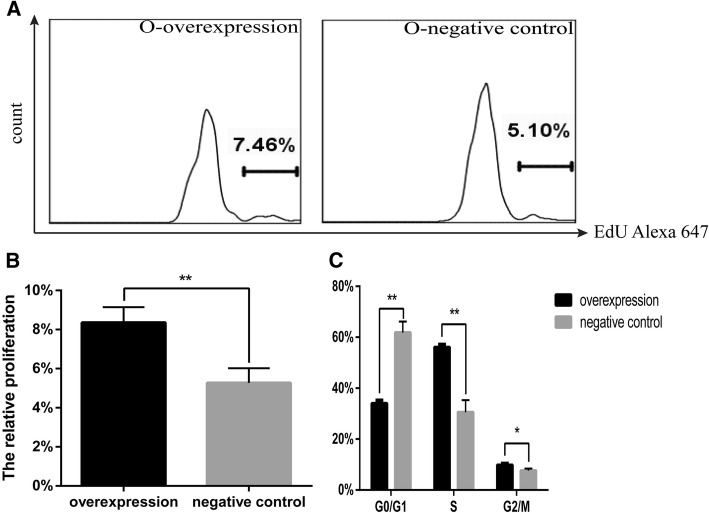

Cited2 is required for CSC proliferation and survival

Cited2 was previously found to play a role in cell proliferation [18]. In order to verify these findings, we transducted O-CSCs with lentivirus overexpressing Cited2 and then analyzed cell proliferation with the EdU assay. Upregulation of Cited2 in O-CSCs increased the proliferative fraction relative to the control group (Fig. 4a, b). To confirm that Cited2 promotes cell growth, we also evaluated the affects of Cited2 on cell cycle distribution by flow cytometry. Cited2 overexpression in O-CSCs reduced the G0/G1 fraction and increased the proportion of cells in S and G2/M phases of the cell cycle relative to the control group (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4.

Cited2 overexpression affects cell proliferation in Old CSCs. a The proliferation was tested by FCM with EdU assays. O-overexpression represented Old CSCs transducted with lentiviral particles of Cited2-cDNA. The control was transducted with empty lentivector. b Statistical analysis of proliferation rate was implemented by GraphPad Prism 5. c Cell cycle analysis was carried out by FCM, statistical analysis of apoptosis rate was implemented by GraphPad Prism 5, *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001, contrast to control. Data are based on three independent experiments, and the picture represents a single result

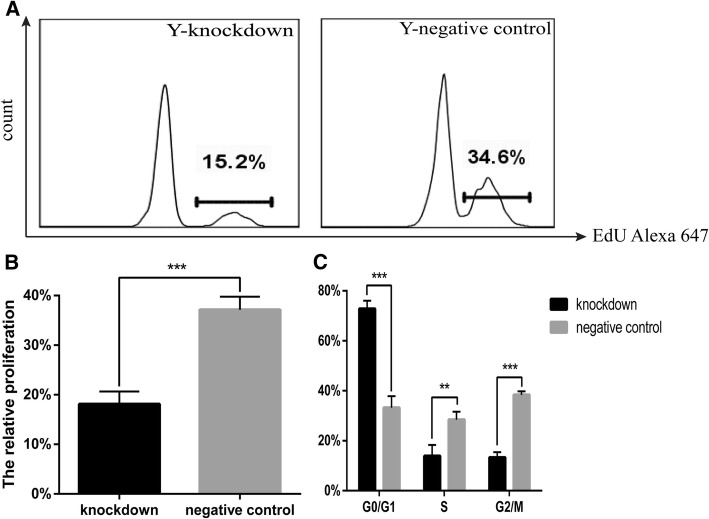

To clarify the role of Cited2 in mouse CSC proliferation, we transfected Y-CSCs with Cited2-shRNA vector and then evaluated EdU incorporation. Cited2 knockdown in Y-CSCs reduced cell proliferation as compared to control cells (Fig. 5a, b). To confirm that Cited2 promotes cell growth, the affects of Cited2 silencing on cell cycle distribution was evaluated by flow cytometry. Cell cycle analyses revealed that downregulation of Cited2 blocked Y-CSCs in G0/G1 phase and consequently reduced the sizes of the S- and G2/M-phase fractions relative to the control group (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5.

Cited2 knockdown affects cell proliferation in Young CSCs. a The proliferation was tested by FCM with EdU assays. Y-knockdown represented Young CSCs transducted with lentiviral particles of Cited2-shRNA3; The control was transducted with empty lentivector. b Statistical analysis of proliferation rate was implemented by GraphPad Prism 5. c Cell cycle analysis was carried out by FCM, statistical analysis of apoptosis rate was implemented by GraphPad Prism 5, *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001, contrast to control. Data are based on three independent experiments, and the picture represents a single result. Knockdown represented Young CSCs transducted with lentiviral particles of Cited2-shRNA3. The negative control was transducted with empty lentivector

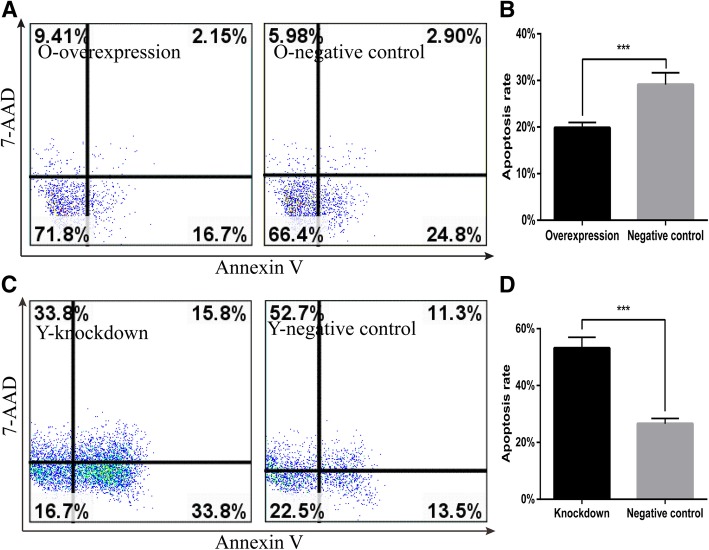

To gain further insight into the role of Cited2 in mouse CSC aging, we analyzed apoptosis in Y-CSCs transfected with vectors encoding Cited2 cDNA or shRNA. Cited2 overexpression inhibited apoptosis as compared to control- transducted cells (Fig. 6a, b), whereas Cited2 knockdown had the opposite effect (Fig. 6c, d). These results demonstrate that Cited2 promotes proliferation while inhibiting apoptosis in CSCs.

Fig. 6.

Cited2 affects cell apoptosis with CSCs aging. The apoptosis was tested by FCM with Annexin V-PE apoptosis detection kit and the PE-positive cells percentage stand for the ratio of apoptosis cells to all numbered cells. a The apoptosis rate in Old CSCs transducted with lentiviral particles of Cited2-cDNA (left panel) and empty lentivector (right panel). b Statistical analysis of apoptosis rate was implemented by GraphPad Prism 5. c The apoptosis rate in Young CSCs transducted with lentiviral particles of Cited2-shRNA3 (left panel) and empty lentivector(right panel). d Statistical analysis of apoptosis rate was implemented by GraphPad Prism 5. *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001, contrast to control. Data are based on three independent experiments and the picture represents a single result. Overexpression represented Old CSCs transducted with lentiviral particles of Cited2-cDNA. Knockdown represented Young CSCs transducted with lentiviral particles of Cited2-shRNA3.The negative control was transducted with empty lentivector

Discussion

Stem cell aging is critically important for organismal development and senescence. The therapeutic potential of CSCs is limited by the decline in their regenerative potential with donor age [11]. The molecular mechanism for stem cell regulation during aging is not well understood. Cited2, a transcription factor that is involved in the control of differentiation and self-renewal in several types of adult stem cell, is downregulated with advancing age [10]. Our results confirmed that Cited2 is downregulated in the heart and CSCs of aging mice. A bioinformatics analysis indicated that changes in Cited2 expression are associated intracellular transport, transcriptional regulation, cell differentiation, and heart development (Additional file 1: Figure S4). Cited2 deficiency was found to contribute to tendon aging and degeneration [10], and loss of Cited2 in mouse ESCs impaired cardiomyocyte differentiation [19] while its overexpression enhanced commitment to the cardiac lineage and differentiation [20]. Cited2 is also known to regulate trophoblast differentiation [21]. Down-regulation of Cited2 was associated with high glucose-induced apoptosis in cardiomyocytes in vitro and maternal diabetes-induced ventricular wall thinness genesis [16]. Cited2 mutations lead to heart disease in humans [22, 23]. Thus, Cited2 has important role in the development, stem cell differentiation, and functional maintenance of the heart. However, in our study, the differentiation potential of CSCs was not significantly altered by Cited2 knockdown or overexpression. We previously reported significant changes in CSCs with advancing age, including an increase in their numbers and a decrease in their stemness characteristics [11]. Others have reported that the fundamental properties of stem and progenitor cells such as quiescence, proliferation, self-renewal capacity, and lineage commitment change with age [24]. The proliferation of Cited2(−/−) mouse embryonic fibroblasts ceases prematurelythat is associated with a reduction in growth fraction, senescent cellular morphology, and increased expression of the cell proliferation inhibitors [25] .In our study, Cited2 promoted CSC proliferation and inhibited apoptosis (Figs. 4 and 5). The proliferative capacity of Y-CSCs was higher than that of O-CSCs. Although the results of apoptosis and proliferation in O-CSC indicate a statistically significant, but the differences between the cell populations and apoptosis are very marginal. With advancing age, the fundamental properties of O-CSCs were weaker than Y-CSCs [11]. Due to the different cellular microenvironments, the effects of Cited2 expression change are also different. With Cited2 -knockdown on Y-CSCs the cells highly affected by Cited2-depletion (Fig. 6) due to apoptotic events, we performed the differentiation tests the impact of Cited2-depletion earlier than 3 days (36 h) after transduction. The cell numbers were more than 3 days after transduction, whereas the cells differentiation was still poorly affected by Cited2 depletion (Additional file 1: Figure S5). Thus, with Cited2 -knocdown in Y-CSCs decreased proliferation and promoted apoptosis while having little affect on CSC differentiation potential. Cited2 overexpression promoted CSC escape from quiescence (G0 phase of the cell cycle) and entry into cell division; however, with increased aging, the cells were blocked in G0 phase.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the results presented here demonstrate that Cited2 plays an important role in cell cycle progression and in maintaining the balance between CSC proliferation and apoptosis in the process of aging without influencing cell fate decisions. These effects may result either from a direct effect of Cited2 or as a consequence of the spontaneous differentiation process induced by Cited2 with aging. Thus, CSCs in aging mice with reduced levels of Cited2 are compromised in their ability to remain undifferentiated under conditions supporting CSC proliferation and self-renewal. These results provide new insights into the biological role of Cited2 that may be useful for optimizing cell-based therapies using CSCs.

Additional files

Figure S1. Differentially expressed genes identified. Figure S2. STC (Series Test of Cluster) analysis of differentially expressed genes. Figure S3. Profile 15 and functional classification of the profile 15. Figure S4. The functional classification of Cited2. Figure S5. The differentiation tests the impact of Cited2-depletion 36 hours after transfection. Figure S6. DD-PCR for Cited2mRNA expression. (DOCX 1384 kb)

Table S1. The differentially expressed genes in profile15. (XLSX 89 kb)

Acknowledgments

We also thank Donglin Chen, Wenjing Zhao from Gene-Cloud Biotechnology Information Center for excellent data handling.

Abbreviations

- 7-AAD

7-aminoactinomycin D

- CITED2

Cyclic AMP response element binding protein (CREB) binding protein (CBP)/p300-interacting transactivator with ED-rich tail 2

- CSCs

Cardiac stem cells

- cTn I

Cardiac troponin I

- dd PCR

Droplet digital PCR

- EGFP

Enhanced green fluorescent protein

- ESCs

Embryonic stem cells

- O- CSCs

Old - CSCs

- RT-PCR

Reverse transcription PCR

- STC

Series test of cluster

- TSPC

Tendon-derived stem/progenitor cells

- VWF

Von Willebrand factor

- Y- CSCs

Young – CSCs

- α-SMA

α-smooth muscle actin

Authors’ contributions

QWu designed the experimental. QWu, QL and JZ carried out most of the experiments. QWa supplemented the western blots experiment. QWa and DZ participated in the design of the study and helped experimental development. QWu and ZZ drafted the manuscript. SH, SP and ZZ conceived, coordinated and provided financial support for the study. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (31660344, 31560319 and 31560248), Natural Science Foundation of Guangxi (2016GXNSFAA380169 to QiongWu) and Guangxi Bagui Scholars Program (to Zuping Zhou). These funding bodies coordinated and provided financial support for the study.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, Guangxi Normal University, Guilin, China.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Qiong Wu, Qin Liu and Jinxi Zhan contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Qiong Wu, Email: wubinbin02@163.com.

Qin Liu, Email: 1132562414@qq.com.

Jinxi Zhan, Email: zhanjinxi052@163.com.

Qian Wang, Email: 1985412764@qq.com.

Daxiu Zhang, Email: 773709585@qq.com.

Shuangli He, Email: 1459135441@qq.com.

Shiming Pu, Email: pushiming77@mailbox.gxnu.edu.cn.

Zuping Zhou, Email: zhouzuping@mailbox.gxnu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Bamforth SD, Braganca J, Eloranta JJ, Murdoch JN, Marques FI, Kranc KR, Farza H, Henderson DJ, Hurst HC, Bhattacharya S. Cardiac malformations, adrenal agenesis, neural crest defects and exencephaly in mice lacking Cited2, a new Tfap2 co-activator. Nat Genet. 2001;29(4):469–474. doi: 10.1038/ng768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bamforth SD, Braganca J, Farthing CR, Schneider JE, Broadbent C, Michell AC, Clarke K, Neubauer S, Norris D, Brown NA, et al. Cited2controls left-right patterning and heart development through a nodal-Pitx2c pathway. Nat Genet. 2004;36(11):1189–1196. doi: 10.1038/ng1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yin Z, Haynie J, Yang X, Han B, Kiatchoosakun S, Restivo J, Yuan S, Prabhakar NR, Herrup K, Conlon RA, et al. The essential role of Cited2, a negative regulator for HIF-1alpha, in heart development and neurulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(16):10488–10493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162371799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weninger WJ, Lopes Floro K, Bennett MB, Withington SL, Preis JI, Barbera JP, Mohun TJ, Dunwoodie SL. Cited2is required both for heart morphogenesis and establishment of the left-right axis in mouse development. Development (Cambridge, England) 2005;132(6):1337–1348. doi: 10.1242/dev.01696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Q, Hakimi P, Liu X, Yu WM, Ye F, Fujioka H, Raza S, Shankar E, Tang F, Dunwoodie SL, et al. Cited2, a transcriptional modulator protein, regulates metabolism in murine embryonic stem cells. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(1):251–263. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.497594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kranc KR, Oliveira DV, Armesilla-Diaz A, Pacheco-Leyva I, Catarina Matias A, Luisa Escapa A, Subramani C, Wheadon H, Trindade M, Nichols J, et al. Acute loss of Cited2impairs Nanog expression and decreases self-renewal of mouse embryonic stem cells. Stem cells (Dayton, Ohio) 2015;33(3):699–712. doi: 10.1002/stem.1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kranc KR, Schepers H, Rodrigues NP, Bamforth S, Villadsen E, Ferry H, Bouriez-Jones T, Sigvardsson M, Bhattacharya S, Jacobsen SE, et al. Cited2is an essential regulator of adult hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5(6):659–665. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du J, Yang YC. Cited2in hematopoietic stem cell function. Curr Opin Hematol. 2013;20(4):301–307. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3283606022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou Z, Akinbiyi T, Xu L, Ramcharan M, Leong DJ, Ros SJ, Colvin AC, Schaffler MB, Majeska RJ, Flatow EL, et al. Tendon-derived stem/progenitor cell aging: defective self-renewal and altered fate. Aging Cell. 2010;9(5):911–915. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00598.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu C, Zhang Y, Tang K, Luo Y, Liu Y, Chen W. Downregulation of CITED2contributes to TGFbeta-mediated senescence of tendon-derived stem cells. Cell Tissue Res. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Wu Q, Zhan J, Pu S, Qin L, Li Y, Zhou Z. Influence of aging on the activity of mice Sca-1+CD31- cardiac stem cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8(1):29–41. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu Q, Zhan J, Li Y, Wang X, Xu L, Yu J, Pu S, Zhou Z. Differentiation-associated MicroRNA alterations in mouse heart-derived Sca-1(+)CD31(−) and Sca-1(+)CD31(+) cells. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016:9586751. doi: 10.1155/2016/9586751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boon RA, Iekushi K, Lechner S, Seeger T, Fischer A, Heydt S, Kaluza D, Treguer K, Carmona G, Bonauer A, et al. MicroRNA-34a regulates cardiac ageing and function. Nature. 2013;495(7439):107–110. doi: 10.1038/nature11919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dufour CR, Wilson BJ, Huss JM, Kelly DP, Alaynick WA, Downes M, Evans RM, Blanchette M, Giguere V. Genome-wide orchestration of cardiac functions by the orphan nuclear receptors ERRalpha and gamma. Cell Metab. 2007;5(5):345–356. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiao S, Mo D, Wang Q, Jia J, Qin L, Yu X, Niu Y, Zhao X, Liu X, Chen Y. Aberrant host immune response induced by highly virulent PRRSV identified by digital gene expression tag profiling. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:544. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Su D, Song JX, Gao Q, Guan L, Li Q, Shi C, Ma X. Cited2participates in cardiomyocyte apoptosis and maternal diabetes-induced congenital heart abnormality. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;479(4):887–892. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.09.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee P, Bova R, Schofield L, Bryant W, Dieckmann W, Slattery A, Govendir MA, Emmett L, Greenfield JR. Brown adipose tissue exhibits a glucose-responsive thermogenic biorhythm in humans. Cell Metab. 2016;23(4):602–609. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chou YT, Hsieh CH, Chiou SH, Hsu CF, Kao YR, Lee CC, Chung CH, Wang YH, Hsu HS, Pang ST, et al. CITED2functions as a molecular switch of cytokine-induced proliferation and quiescence. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19(12):2015–2028. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Q, Ramirez-Bergeron DL, Dunwoodie SL, Yang YC. Cited2gene controls pluripotency and cardiomyocyte differentiation of murine embryonic stem cells through Oct4 gene. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(34):29088–29100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.378034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pacheco-Leyva I, Matias AC, Oliveira DV, Santos JM, Nascimento R, Guerreiro E, Michell AC, van De Vrugt AM, Machado-Oliveira G, Ferreira G, et al. CITED2Cooperates with ISL1 and promotes cardiac differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. Stem Cell Rep. 2016;7(6):1037–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Imakawa K, Dhakal P, Kubota K, Kusama K, Chakraborty D, Karim Rumi MA, Soares MJ. CITED2modulation of trophoblast cell differentiation: insights from global transcriptome analysis. Reproduction (Cambridge, England) 2016;151(5):509–516. doi: 10.1530/REP-15-0555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Q, Pan H, Guan L, Su D, Ma X. CITED2mutation links congenital heart defects to dysregulation of the cardiac gene VEGF and PITX2C expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;423(4):895–899. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.06.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li B, Pu T, Liu Y, Xu Y, Xu R. CITED2Mutations in conserved regions contribute to Conotruncal heart defects in Chinese children. DNA Cell Biol. 2017;36(7):589–595. doi: 10.1089/dna.2017.3701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hariharan N, Sussman MA. Cardiac aging - getting to the stem of the problem. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015;83:32–36. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kranc KR, Bamforth SD, Braganca J, Norbury C, van Lohuizen M, Bhattacharya S. Transcriptional coactivator Cited2induces Bmi1 and Mel18 and controls fibroblast proliferation via Ink4a/ARF. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(21):7658–7666. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.21.7658-7666.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Differentially expressed genes identified. Figure S2. STC (Series Test of Cluster) analysis of differentially expressed genes. Figure S3. Profile 15 and functional classification of the profile 15. Figure S4. The functional classification of Cited2. Figure S5. The differentiation tests the impact of Cited2-depletion 36 hours after transfection. Figure S6. DD-PCR for Cited2mRNA expression. (DOCX 1384 kb)

Table S1. The differentially expressed genes in profile15. (XLSX 89 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.