Abstract

Breast cancer is one of the most common malignancies in females. It is an etiologically complex disease driven by a multitude of cellular pathways. The proliferation and spread of breast cancer is intimately linked to cellular glucose metabolism, given that glucose is an essential cellular metabolic substrate and that insulin signalling has mitogenic effects. Growing interest has focused on anti-diabetic agents in the management of breast cancer. Epidemiologic studies show that metformin reduces cancer incidence and mortality among type 2 diabetic patients. Preclinical in vitro and in vivo research provides intriguing insight into the cellular mechanisms behind the oncostatic effects of metformin. This article aims to provide an overview of the mechanisms in which metformin may elicit its anti-cancerous effects and discuss its potential role as an adjuvant in the management of breast cancer.

Keywords: Breast cancer, type 2 diabetes, metformin, insulin

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is one of the most frequently occurring cancers in females and represents a significant public health concern. The American Cancer Society estimates that one in eight females will develop BC at some point in their lives, with the incidence increasing with age.1 Significant geographic and ethnic-specific differences in both incidence and mortality rates are reported. This is in part attributed to sociodemographic factors which influence adherence to recommendations for early screening for BC, as well as the likelihood of seeking appropriate medical advice upon detection of a breast mass.2,3 The aetiology behind BC is equally complex and involves interactions between environmental, lifestyle and genetic factors that collectively determine cancer risk.

BC typically arises when cells lose the ability to halt the process of proliferation, coupled to resistance or reduction in the process of cell death by apoptosis. BC cells express high levels of phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signalling molecules, which impairs their ability to undergo apoptosis.4 Pathologically, BC is classified either as invasive or non-invasive type. The non-invasive subtypes include ductal and lobular carcinoma in situ, whereas, ductal and lobular carcinomas are considered as invasive subtypes. On average, ductal carcinoma accounts for 80% of reported cases in females, whereas lobular carcinoma accounts for only 5%–10% of the cases.5 Currently, BCs are treated either surgically or via chemoradiotherapy, in addition to the use of Trastuzumab (Herceptin®) for HER2+ tumours.6

Some cases of BC do not respond well to traditional treatment, particularly in diabetics. Recent studies have shown that metformin, a primary anti-diabetic agent, confers anti-tumorigenic effects on cancer cells and can be considered as a potential adjuvant in the management of BC.7 A number of population-based observational studies had initially suggested that metformin reduces cancer incidence and/or mortality among type 2 diabetic patients, however, no causal relationship can be established from epidemiologic data alone.8 Preclinical research using both BC cell lines and mouse models subsequently showed that metformin represses cancer cell and xenograft growth.9–11 These effects are achieved through various mechanisms, including cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activation and mTOR inhibition. In addition, metformin exerts in vitro chemo preventive effects through modulation of cytochrome P4501A1 (CYP1A1)/aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) pathways.12 The anti-tumour effects of oral anti-diabetic therapy are not restricted to metformin, as thiazolidinediones (synthetic ligands of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors γ – PPARγ) possess similar properties. Animal studies have shown that pioglitazone inhibits chemical carcinogenesis in rats.13 Human studies demonstrate that rosiglitazone reduces BC risk in females with type 2 diabetes, and that this effect is enhanced by metformin.14 The pleiotropic oncostatic effects of oral anti-diabetic drugs is reinforced by meta-analysis showing that thiazolidinediones are associated with a lower incidence of cancer, particularly colorectal and breast tumours.15

Furthermore, metformin also decreases the development of resistance in BC cells, thereby allowing current chemotherapy agents to work synergistically with metformin.16 It also blocks the two cellular pathways for nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) regeneration, which then results in a complete loss of cells’ NAD+ recycling capacity. The resulting depletion of NAD+, in turn, leads to cell death.17 This article aims to provide an overview of the pathomolecular mechanisms in which metformin may elicit its anti-cancerous effects and discuss its potential role as an adjuvant in the management of BC.

Pathophysiology of BC

Inflammation and neoplastic transformation in BC

The importance of the immune response in BC development and progression has been well documented. DeNardo and Coussens18 highlight a possible immunological connection between BC and Th2 inflammatory cells that results in the promotion of tumour development and disease progression, whereas acute anti-tumour responses involving cytolytic T lymphocytes appear to protect against tumour development. Physiologically, injured tissues or cells exposed to chemical irritants are eliminated by apoptosis. This is followed by enhanced cell proliferation to facilitate tissue regeneration and re-establish tissue function. Moreover, proliferation and inflammation may persist until the insulting agent is removed, allowing the tissue to heal completely. If the inflammation persists, cells may undergo dysplastic changes, which then increases the risk of neoplasia.19

The role of leukocytes, especially the cytotoxic T lymphocytes in tumorigenesis, has been explored extensively. These cells are believed to assist in the eradication process of neoplastic cells with the help of natural killer (NK) cells.20 Nevertheless, T-cell infiltration in invasive BC has been reported, especially the activated CD4+ Th1 polarised cells that secrete several inflammatory cytokines – including IFNγ, transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) and interleukin-2 (IL-2). These cytokines then interact with other cytotoxic T-cells and upregulate the MHC class I and II molecules, as well as other antigen display co-factors in neoplastic cells.18,20 This process is an essential part of immune-mediated anti-tumorigenic effects. Conversely, activation of Th2-polarised CD4+ T-helper cells results in expression of inflammatory cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, and IL-13), which then enhances humoral immunity and downregulates cell-mediated anti-tumour immunity; thereby, promoting the pro-tumour humoral response.18,21–24

Neoplastic transformation is a complex multistage event

BC originates in the undifferentiated lobules type 1, which are composed of three cell types: the highly proliferating cells (ER−), non-proliferating cells (ER+) and very few ER+ cells that proliferate. Endogenous 17 beta-oestradiol (E2), when metabolised by cytochrome P450 enzymes may also act as a carcinogen which ultimately leads to genomic changes and transformation phenotypes observed in spontaneously developing primary BCs. Endogenous E2 is metabolised by P450 cytochromes that also activate benzo[a]pyrene B[a] a carcinogen present in cigarette smoke.25 The genomic alterations induced by E2 and B[a]P in vitro are also observed in ductal hyperplasia DCIS and invasive ductal carcinoma.

Transcriptional repressors, such as Polycomb Group Protein (EZH2), which traditionally controls the cellular memory have been linked to cancer cell invasion and BC progression. Kleer et al.26 demonstrated that EZH2 protein levels were strongly associated with BC aggressiveness. Moreover, EZH2 overexpression promoted anchorage-independent growth and cell invasion through the SET domain and histone deacetylase activity. Dysregulated cellular memory, transcriptional repression and neoplastic transformation are interlinked, and EZH2 may be a marker for aggressive BC and neoplastic transformation. The actual neoplastic transformation process involved in BC is more complex than previously thought and warrants more long-term molecular studies to better understand the actual transformation process and ways to halt such process.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus and cancer

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a metabolic disorder which is associated with several cancers. It is characterised by hyperglycaemia, insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. These factors interact to promote cell proliferation through the mitogenic effect of the insulin receptor and insulin-like growth factors (IGFs), while hyperglycaemia provides the metabolic substrate for cell proliferation.27 Overexpression of the insulin growth factor receptor-1R (IGF-1R) or insulin receptors leads to mitogenic signalling, which increases activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3)-Akt-mTOR signalling pathways. Excess adiposity increases local production of oestrogen via the enhanced activity of aromatase, which augments oestrogen receptor alpha signalling (ER-α) in tumour cells. The inflammatory effect of hyperinsulinemia, in addition to increasing production of local cytokines, may lead to an increased susceptibility to cancer development in diabetes.28

A number of large-scale epidemiological studies and meta-analyses have reported an increase in the incidence of several cancers in T2DM.29,30 A population-based cohort study by Ballotari et al.31 showed a higher cancer incidence in subjects with diabetes. This relationship was only observed in those with T2DM, but not in Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) and was attributed to obesity. Notably, the risk was higher among insulin users. An increased risk of cancer at several tissues, including liver, pancreas, endometrium, colorectum, breast and bladder has been described in multiple similar studies. Notably, these observations could be either causal – driven by the metabolic disturbances in diabetes or else due to the confounding effects of the underlying excess adiposity in diabetes. Tsilidis et al.29 show that individual studies are, however, characterised by substantial heterogeneity, small study effects and excess significance, with 28% (135/474) of studies adjusting risk estimates either for age or gender. Despite the evidence from epidemiological studies linking diabetes to cancer incidence, the specific mechanisms driving this association are not fully understood.

T2DM and BC

Mechanisms behind T2DM and BC

Studies have shown that BC in women with diabetes is often diagnosed at an advanced stage compared with women without diabetes.32,33 Furthermore, the overall mortality following BC diagnosis is 30%–60% higher in women with diabetes compared with women without diabetes after adjusting for tumour stage.34,35 A cross-sectional study by Bronsveld et al.34 also showed no relation between diabetic status and tumour morphology and grade. However, premenopausal diabetic women tended to develop breast tumours that do not express progesterone receptor and HER2, which are typically associated with poor prognosis. No association between insulin therapy and clinicopathological subtypes was noted, even though insulin use in T2DM may induce oestrogen (ER) and progesterone receptors expression.36 Conversely, a systematic review of in vitro, animal and human studies found no evidence of increased BC risk with commercially available insulin analogues and human insulin.37 Conflicting findings were reported by other investigators. Tseng,38 showed that prolonged use of insulin carries a significantly higher BC risk. A recent study by Overbeek et al.39 showed that females with T2DM were at an increased risk of being diagnosed with a more aggressive type of BC than non-T2DM females. Interestingly, exogenous insulin administration was not associated with the development of more advanced BC tumours in this study. These findings suggest that insulin may not be involved directly in the development of BC. Instead, it may promote BC progression by upregulating mitogenic signalling pathways.37

The precise mechanisms linking T2DM to BC progression remains uncertain, but is believed to involve insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1). IGF-1 pathways are activated by a high concentration of insulin, which then goes on to promote cancer development via the insulin/IGF-1 hybrid receptors. These have a higher affinity for IGF-1 than for insulin and are overexpressed in BC tissues of T2DM patients.40–42 Nevertheless, due to insufficient evidence on the specific oncogenic pathways connecting hyperinsulinemia to BC, it is difficult to ascertain the role of insulin in the development of BC in premenopausal and postmenopausal diabetic females.

Oestrogen, diabetes and BC

Epidemiological and clinical studies have shown that T2DM is a risk factor for BC and is consequently associated with poor prognosis.43 Wairagu et al.44 investigated the effects of oestradiol on MCF-7 BC cells primed with and without insulin chronically. The study found that insulin priming was a prerequisite for oestradiol-induced growth in BC cells. The authors demonstrate that oestradiol exposure increases expression of cyclins A and B, which are both involved in cell cycle progression and leads to the activation of genes in the pentose phosphate and serine biosynthesis pathways. Oestradiol also increased anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL expression in the insulin-primed cells. In addition, metformin suppresses oestradiol-induced growth in the insulin-primed cells. Critically, this study showed that insulin priming dramatically sensitises BC growth to 100 pmol of oestradiol.

Conversely, other studies have shown that at least 10–100 nM of oestradiol concentration is required before maximum cell growth is attainable in BC cells.45,46 These findings suggest that insulin priming happens readily in diabetics as a result of the chronic hyperinsulinemic state even at physiological levels of oestradiol, thus exposing diabetics to an elevated risk of developing BC. Oestradiol modulates cell cycle and apoptotic processes in insulin-primed cells, which then further promotes cancer cell growth. Wairagu et al.44 also showed that both insulin-primed and unprimed MCF-7 cells exposed to dihydrotestosterone (DHT) exhibit no growth response, which further indicates that there is crosstalk between insulin priming and ER-induced BC cell growth.

In the insulin resistant state, suppression of sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) increases the bioavailability of free oestrogen, leading to elevated levels of serum oestrogen.47 Moreover, IGF-1 is known to increase the production of androgens, which may then subsequently displace oestrogen binding from SHBG.48,49 Furthermore, IGF-1 can interact with 17-beta-oestradiol leading to increased proliferation of BC cells.50 Therefore, altered levels of endogenous oestrogen may contribute to the proliferation of ER-positive BC in T2DM.42 Since the prevalence of obesity is high in T2DM, elevated levels of oestradiol and oestrone can result from increased adipose tissues aromatase activity.51 Also, hyperinsulinemia in T2DM may induce the expression and binding capacity of ER, which can subsequently enhance insulin mitogenic properties by promoting IRS-1 function, and through activation of PI3K and Ras/MAPK signalling.52 The production of inflammatory mediators in T2DM, mainly TNF-α and interleukin-6 (IL-6), which are both associated with insulin resistance in diabetics, secondarily enhances the oestrogen synthesis in normal and BC cells. This further potentiates BC development.53,54

Oxidative stress, diabetes mellitus and BC

Hyperglycaemia induces oxidative stress through direct or indirect pathways in BC cells by increasing levels of insulin/IGF-1 and inflammatory cytokines, particularly IL-6 and TNF-α.55 Together, they activate nuclear factor kappa (NFκB), signal transducer activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) and the hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF1α).56 These factors result in increased free radical production, leading to damage to DNA, lipids and further amplification of the inflammatory processes [27]. The reactive oxidative species derived may then initiate carcinogenesis by modifying the apoptotic responses, as well as disrupting cell anchoring sites and increasing angiogenesis.57,58 In addition, studies have shown that hyperglycaemia also indirectly activates endothelial growth factor receptor (EGFR) via the Rho family GTPase Rac1 and cell division control protein 42 homolog (Cdc42), which then stimulates the cell proliferation, thus providing another mechanistic link between hyperglycaemia and tumorigenesis.59

Hyperglycaemia leads to the modulation of various pathways that control cell proliferation, migration and invasion.60 Cancer cells demonstrate enhanced glucose uptake and metabolism, a process referred to as the ‘Warburg effect’. Hyperglycaemia thus provides the necessary fuel which the cancer cells require, and this then allows cancer cells to proliferate rapidly.61 Hyperglycaemia also stimulates upregulation of protein kinase C (PKC), PPARs and proliferation in MCF-7 BC cell lines.62

Hyperglycaemia also promotes BC cell migration via zinc and its transporters (ZRT/IRT-like protein 6, ZRT/IRT-like protein 10). High serum glucose leads to increased expression of zinc transporters (ZIP6 and ZIP10), which are essential for promoting cell migration and motility in BC cells.63,64 These findings emphasise the importance of stringent control of glucose levels in both T2DM and BC in order to reduce cancer cell proliferation.

The pharmacologic management of hyperglycaemia hinges on the use of sulphonylureas, metformin and insulin. Therapy that leads to hyperinsulinemia, such as sulphonylureas and exogenous insulin, are thought to increase the risk of cancer, while treatment that reduces insulin resistance, such as metformin, are thought to reduce the risk of cancer development. A meta-analysis investigating cancer risk associated with metformin and sulphonylureas in T2DM showed that use of metformin was associated with significantly decreased risk of all cancers. However, no evidence that use of metformin is associated with the risk of BC was derived.65 This meta-analysis was characterised by extensive between-study heterogeneity and evidence of publication bias with regard to metformin. Hence long-term randomised double-blinded clinical trials are required to substantiate the benefit and efficacy of using anti-diabetic agents in BC treatment.

Metformin and BC

Mechanisms of metformin action in normal cells

Metformin (1,1-dimethyl biguanide) is a biguanide which acts by reducing hepatic glucose output and increasing insulin sensitivity. This results in a reduction in serum glucose levels without the risks of either hypoglycaemia or weight gain. Metformin also modulates multiple components of incretin pathways. It increases the plasma levels of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) and induces islet incretin receptor gene expression via PPAR-α.66 Metformin is taken up by hepatocytes via the organic cation transporter 1 (OCT1) and inhibits hepatic gluconeogenesis by modulating enzymes and substrate which are involved in the gluconeogenic pathways.67–70 The decrease in hepatic glucose production results in the activation of AMPK, which is a cellular metabolic sensor responsible for protecting cellular functions under low energy conditions.71,72 AMPK is normally activated by an increase in the intracellular AMP: ratio, which results from an imbalance between the ATP production and consumption.71

Upon activation, phosphorylation of AMPK by tumour suppressor serine/threonine kinase 11 (STK11/LKB1) and calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase-2 (caMKK-2) causes AMPK to switch cells from an anabolic to the catabolic state. In doing so, it shuts down the ATP-consuming pathways by inhibiting glucose, lipid, protein synthesis and cellular growth, whereas fatty acid oxidation, as well as glucose uptake, is stimulated to restore the AMP:ATP ratio.71 Metformin primarily acts on the mitochondria by inducing mild and specific inhibition of mitochondrial respiratory-chain complex 1 (MRCC1), which is present in hepatocytes, skeletal muscles, endothelial cells, pancreatic beta-cells and neurons.73–79 In addition, metformin also reduces mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) production by selectively inhibiting reverse electron flow through MRCC1.80,81

ROS are important mediators of cell and genomic damage and play essential roles in the pathophysiology of both T2DM and BC. Inhibition of ROS generation through metformin may thus have benefits that extend beyond its traditional use as an oral hypoglycaemic agent. In this context, several studies have shown that metformin exhibits anti-cancer effects in BC patients with diabetes. Conversely, the efficacy of metformin and its use in non-diabetic BC patients is not widely studied, with conflicting effects being reported. A summary of the findings from studies involving metformin therapy in BC patients without DM is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

A summary of the salient findings from studies investigating metformin administration in non-diabetic females with breast cancer.

| Title | Study | Study population | Study findings | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metformin may protect non-diabetic breast cancer women from metastasis | El-Haggar et al.82 | Non-diabetics newly diagnosed with BC | A total of 102 women newly diagnosed with BC were divided into the control group and metformin group. All women were treated with adjuvant therapy and the metformin-treated group received 850 mg of metformin twice daily. The metformin group demonstrated lower IGF-1, IGF1: IGFBP-3 ratio, insulin, FBG and HOMA-IR. Metformin had potential anti-tumour and anti-metastatic effects that require further exploration | Follow-up for 12 months only. and study did not indicate whether metformin use had affected different stages of the BC |

| Metformin anti-proliferative effects on a cohort of non-diabetic breast cancer patients | Sadighi et al.83 | Non-diabetics with BC on metformin versus non-diabetics with BC not on metformin | A prospective randomised controlled study about metformin efficacy in the window time between biopsy and definite surgery were carried out. Primary endpoint was changes in Ki67 expression. The intervention group was prescribed 1500 mg/day metformin from biopsy to night before surgery. A significant reduction in Ki67 was noted. Study concluded that metformin prescription for short period exhibits an inhibitory effect on BC cell growth | The population size for the study was small (50 patients) and the time frame between metformin use and the obtained results was relatively short. Further long-term trials are needed |

| Insulin-lowering effects of metformin in women with early breast cancer | Goodwin et al.84 | Early BC patients | 22 non-diabetic females with BC treated with metformin (500 mg tid × 6 months) showed lower insulin levels, and it improves insulin resistance in non-diabetic females with BC. More long-term trials are recommended | |

| Evidence for biological effects of metformin in operable breast cancer: a pre-operative, window-of-opportunity, randomised trial | Hadad et al.85 | Operable invasive BC | Trial examined effects of metformin on Ki67 and gene expression in primary BC in non-diabetic females. 47 patients were randomised to metformin 500 mg od for a week and increased to 1 g bd for a further week until surgery. Gene set analysis revealed p53, BRCA1 and cell cycle pathways showed reduced expression following metformin administration | Population size was small and not age-matched |

| Evidence for biological effects of metformin in operable breast cancer: biomarker analysis in a pre-operative window of opportunity randomised trial | Hadad et al.86 | Operable invasive BC in non-diabetics | Non-diabetic females with operable invasive BC randomised received pre-operative metformin (500 mg daily for 1 week and then 1 g bd for a further week) and control receiving no metformin. Level of Ki67 and cleaved caspase-3 fell significantly in metformin-treated cohorts but not in control | Metformin acts on BC cells via pAMPK upregulation and downregulation of pAkt and insulin suppression through cytostatic mechanisms |

| Dual effect of metformin on breast cancer proliferation in a randomised pre-surgical trial | Bonanni et al.87 | Operable BC | A total of 200 non-diabetic females with operable BC administered with 850 mg bd metformin (n = 100) and placebo (n = 100). Metformin prior to surgery did not affect Ki67 levels but did affect the insulin resistance in tumour cells | |

| The effect of metformin on apoptosis in a breast cancer presurgical trial | Cazzangia et al.88 | Operable BC | A total of 87 females (45 on metformin, 42 on placebo) assessed for 4 weeks before surgery. No modulation of apoptosis by metformin was found but it did affect the insulin resistance status and the Ki67 levels | |

| Differential effects of metformin on breast cancer proliferation according to markers of insulin resistance and tumor subtype in a randomised pre-surgical trial | DeCensi et al.89 | Operable BC | A total of 200 non-diabetic females randomly allocated to metformin (850 mg bd) or placebo for 4 weeks prior to BC surgery. Compared to placebo, metformin reduced Ki67 in women with HOMA-IR > 2.8 and HER2 positive tumours. No trend was noted in women with HOMA-IR < 2.8 | Study showed that at conventional anti-diabetic dosage, the effect of metformin on Ki67 depends on the tumour characteristics and insulin resistance |

| Presurgical trial of Metformin in overweight and obese patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer | Kalinsky et al.90 | Invasive BC or DCIS | A total of 1500 mg of metformin was administered to 35 non-diabetics with stages 0–III BC and BMI of >25 kg/m2. No reduction in Ki67 was noted after metformin administration compared to controls, but there was significant reduction in BMI, cholesterol and leptin levels | Trial registration NCT00930579 |

| Effect of metformin vs placebo on and metabolic factors in NCIC CTG MA.32 | Goodwin et al.91 | Early BC | The NCIC Clinical trial group MA.32 investigated effects of metformin vs placebo on invasive disease-free survival and other outcomes in early BC. 492 females were randomly assigned treatment for 6 months. Study concluded that metformin significantly improved weight, insulin, glucose, leptin and hsCRP at 6 months | |

| Metformin in early breast cancer: a prospective window of opportunity neoadjuvant study | Niraula et al.92 | Operable BC | A total of 39 patients with newly diagnosed, untreated, non-diabetic BC patients were treated with 500 mg tid metformin after diagnostic core biopsy until definitive surgery. Study concluded that short-term use of metformin resulted in beneficial clinical and cellular changes (reduced BMI, weight, HOMA, reduced Ki67 staining in invasive tumour) consistent with beneficial anti-cancer effect | |

| Changes in insulin receptor signalling underlie neoadjuvant metformin administration in breast cancer: a prospective window of opportunity neoadjuvant study | Dowling et al.93 | Operable BC in non-diabetics | Neoadjuvant, single-arm trial conducted to determine the clinical and biological effects of metformin on patients with BC. Females with untreated BC were administered 500 mg of metformin tid for over 2 weeks from after diagnostic biopsy until surgery. Results showed a reduction in PKB/Akt and ERK 1/2 phosphorylation with decreased insulin and IR levels | Clinical trial NCT00897884 |

| Metformin intervention in obese non-diabetic patients with Breast Cancer: phase II randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | Ko et al.94 | Obese females with BC | The randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial performed to evaluate the efficacy of metformin for controlling physical and metabolic profile in non-diabetic BC patients. 105 females with BC at 6 months post-mastectomy with BMI of >25 kg/m2 and/or pre-diabetes were assigned into three groups (placebo, metformin 500 mg and metformin 1000 mg) stratified by tamoxifen use. Study found that metformin 1000 mg had favourable effects on controlling glucose and HbA1C levels in obese non-diabetic BC patients |

AMPK: AMP-activated protein kinase; BC: breast cancer; IGF: insulin-like growth factors; DCIS: ductal carcinoma in situ; BMI: body mass index.

Mechanism of metformin action in BC

Insight into the anti-tumour role of metformin in BC has been provided by Dowling et al.93 in a clinical trial (NCT00897884). Non-diabetic females with untreated BC were trialled on neoadjuvant metformin from biopsy till surgery for BC. Immunohistochemical analysis of tumour specimens showed a significant reduction in expression of insulin receptors, phosphorylation of protein kinase B (PKB)/Akt, AMPK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase1/2 and acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase. These insulin-dependent effects are consistent with the beneficial anti-cancer effects of metformin.

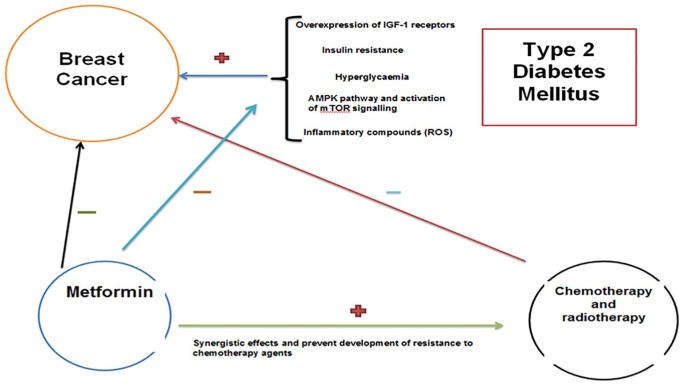

Metformin indirectly activates AMPK, leading to the inhibition of protein synthesis and gluconeogenesis. Thus, it may act to limit the availability of nutritional substrates that are mandatory for cancer cell proliferation.95 An overview of these effects is provided in Figure 1. Furthermore, AMPK also inhibits mTOR, which is a downstream activator of growth factors in malignant cells and is associated with resistance to anti-cancer drugs.95 The role of metformin is not limited to AMPK pathways. It induces cell cycle arrest, thereby inducing sub-G1 populations and activating apoptotic pathways through downregulation of p53 and differentiated embryo chondrocyte 1 (DEC1) proteins.96 Metformin administration also leads to an increase in intracellular ROS by disrupting the mitochondrial electron transport chain and collapsing the mitochondrial membrane potential. Queiroz et al.97 showed that metformin has time- and concentration-dependent anti-proliferative properties on MCF-7 cells. Metformin exhibits pro-apoptotic effects and promotes cell cycle arrest via increased oxidative stress, as well as AMPK and FOXO3a activation.

Figure 1.

Metformin inhibits the inflammatory pathways which are induced by hyperglycaemia and insulin resistance. This indirectly acts by deactivating AMPK pathways, thereby allowing the anti-cancer effects of metformin to be exhibited. Metformin also works synergistically with chemotherapy agents and reduces the development of resistance of BC to these agents, thereby maximising their effects on BC cells.

The proliferation and migration of BC cells is suppressed by metformin via the dysregulation of the matrix metalloproteinases MMP-2 and MMP-9, in addition to downregulation of oncogenic microRNAs miR-21 and miR-155.98 Giles et al.99 demonstrated that metformin can decrease the size of mammary tumours and inhibit tumour formation in ovariectomised rats with 1-methyl-1-nitrosourea (MNU)-induced mammary tumours. Furthermore, metformin promotes a decrease in the number of aromatase-positive, CD68-positive macrophages within the tumour microenvironment, as well as decreased lipid accumulation in the livers of treated rats. This study showed that metformin targets both whole-body metabolism and the tumour microenvironment and that the perimenopausal period may represent a window of opportunity where metformin may be highly effective in women at risk for or with established BC. Other investigators have produced similar findings, demonstrating decreased tumour volumes and reduced proliferation in in vivo animal models of BC.100,101 Recently, Bojkova et al. showed that administration of metformin in a rat model with MNU-induced mammary tumours resulted in an increased proportion of low-grade tumours.102 A significant positive correlation between histological grade and Ki67 expression was noted. However, no differences in tumour incidence and frequency were observed. The improved tumour histopathological profile was accompanied by a reduction in serum IGF-1 levels.

Metformin also exhibits cytostatic effects analogous to antifolate chemotherapeutic agents. In vitro metabolomic studies have shown that metformin has mitochondrial-independent AMPK-activating effects that cause defects in de novo purine/pyrimidine biosynthesis and homocysteine accumulation.103

Metformin also exerts anti-inflammatory effects in cell models by inhibiting the NFκB pathways necessary for transformation and cancer stem cell formation. It inhibits nuclear translocation of NFκB and phosphorylation of STAT3 in cancer stem cells compared with non-stem cancer cells in the same population, thus suppressing the early stages of the inflammatory pathway that is associated with cancer.104–106

In light of these findings from cell and animal models, it is natural to question whether metformin is a suitable adjuvant and if it should be implemented in current clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of BC. Clinical data extracted from drug trials have shown that metformin does show synergistic apoptotic effects when used with chemotherapeutic agents in BC.50,107 Furthermore, when metformin is used as a single-agent, it may trigger cell cycle arrest in both oestrogen receptor positive (ER+) and ER-negative (ER–) BCs cells.108,109 Metformin also elicits toxic effects on cancer stem cells, but not on normal stem cells. This property of metformin is valuable since cancer stem cells play a critical role in cancer recurrence.104,110 A number of systematic reviews and meta-analyses highlighting metformin’s role in BC and their limitations are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of systematic reviews and meta-analysis available on metformin’s role in breast cancer.

| Title | Authors and date of publication | Summary of the study | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| The effect of metformin on biomarkers and survival for breast cancer – a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials | Zhang et al.111 | Ten studies comprising 1520 BC patients. Metformin reduces levels of insulin, HOMA-IR, sex hormones, SHBG, Ki67, caspase-3, p-Akt, obesity, hs-CRP, blood glucose and lipid profile. Overall survival was non-significantly better in metformin arm than control arm. The authors concluded that further large-scale trials are needed | The authors suggested that observational studies used for the systematic review and meta-analysis had residual confounding, selection biases and warranted data from more randomised clinical trials. They concluded that current data regarding metformin in BC is lacking and inconsistent |

| Association of Metformin with Breast Cancer Incidence and Mortality in Patients with Type II diabetes: A GRADE-Assessed Systematic Review and Meta-analysis | Tang et al.112 | Twelve observational studies were included for BC incidence and 11 studies for all-cause mortality. No significant association was found between metformin exposure and incidence of BC. A 45% risk reduction was observed for all-cause mortality. The use of metformin may improve overall survival in patient with T2D and BC | |

| Metformin as an adjuvant therapy for cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis | Coyle et al.113 | A meta-analysis of 27 observational studies with 24,178 subjects. No significant beneficial outcome was observed with regard to BC in metformin users compared with non-users. Significant benefit was, however, observed for early-stage colorectal and prostate cancer | This meta-analysis was not specifically exploring BC incidences, instead it was evaluating the effect of metformin on recurrence-free survival, overall survival and cancer-specific survival. Data were not available to conduct analyses on the impact of metformin dose and duration |

| Diabetes mellitus is associated with breast cancer: a systematic review, meta-analysis and in silico reproduction | Zhou et al.114 | Twenty studies were used for this meta-analysis to explore the association between DM and BC survival outcome. Pre-existing diabetes was associated with 37% increase in all-cause mortality risk in females with BC | Cohorts used by the selected studies were not age-matched, nor was the dose of metformin used in each study specified |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy for early female breast cancer: a systematic review of the evidence for the 2014 Cancer Care Ontario systemic therapy guideline | Gandhi et al.115 | The Program in Evidence-Based Care (PEBC) of Cancer Care Ontario complied a guideline on the systematic treatment of early BC. The Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group meta-analyses included RCTs. Chemotherapy was divided into three classes: anti-metabolite-based regimens, anthracyclines and taxane-based regimens. In terms of metformin use in early BC, the review specified that this drug is still in the early investigation phase | |

| Metformin and cancer risk and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis taking into account biases and confounders | Gandini et al.116 | A meta-analysis was carried out using 71 articles related to metformin and cancer incidence or mortality. Results showed that metformin may reduce cancer incidence and mortality in diabetics, but the reduction is modest and does not affect all populations equally | The limitations of the study included heterogeneity of study design and treatment comparators. Approximately 2/3 of the studies were prone to source of bias as they were retrospective. The comparator group included treatment with insulin and insulin secretagogues. These drugs increase levels of insulin and have been associated with increased cancer risk. Allocation bias was also reported, with metformin users being at different stage of diabetes than comparators |

| The prognostic value of metformin for cancer patients with concurrent diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis | Zhang and Li117 | Twenty-eight studies were used for this meta-analysis. The authors showed that metformin lowers the risk of all-cause mortality in cancer patients with concurrent diabetes, particularly in BC. The findings from the study supported the notion that metformin improves the survival for cancer patients with concurrent diabetes, particularly breast, colorectal, ovarian and endometrial cancers, but warrants further investigation in relation to the efficacy | Limitation of the meta-analysis include the high heterogeneity across the studies. The information on cancer treatment was not described clearly by each of the studies that were used, thus creating a bias effect on the survival rate. Moreover, the dose of metformin and cancer stage were not reported |

| Metformin therapy and risk of cancer in patients with type 2 diabetes: systematic review | Franciosi et al.118 | Twelve randomised controlled trials (21,595 patients) and 41 observational studies (1,029, 389 patients) were used for this analysis. Metformin use was associated with significantly reduced risk of some cancers (liver, colorectal, pancreas, stomach and oesophagus) and cancer-related mortality. No effect on the risk of BC was reported | The authors concluded that the results derived from the observational studies were prone to bias and confounding inherent due to their design. In addition, some studies were retrospective, and suffered from interviewer and recall bias. The data on dose, duration of therapy and variation over time for treatment, as well as full information on risk factors and potential confounders were incomplete |

| Metformin and breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis and critical literature review | Col et al.119 | Seven independent observational studies were included in this systematic review. The authors showed that metformin has a protective effect on BC risk among postmenopausal females with diabetes | Results obtained were limited by the observational nature of the reports and different comparison groups that were not age-, race- or stage-matched |

| Metformin and cancer risk in diabetic patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis | Decensi et al.120 | Eleven studies reporting 4042 cancer events and 529 cancer deaths were selected for this meta-analysis. A 31% reduction in overall relative risk of pancreatic and hepatocellular cancer in subjects taking metformin compared with other anti-diabetic drugs was reported. No significant findings for breast, colon and prostate cancer were reported |

BC: breast cancer; SHBG: sex hormone binding globulin; hs-CRP: high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; DM: diabetes mellitus; RCT: randomised controlled trial.

Triple-negative BC (TNBC) carries the poorest prognosis of all BC subtypes. In vitro studies have shown that metformin administration enhances the sensitivity of TNBC cell lines to TRAIL receptor agonists.121 TRAIL agonists (TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) are tumour-specific inducers of apoptosis that have strong anti-tumour effects in preclinical models.122 Metformin reduces the levels of XIAP, a negative regulator of TRAIL-induced apoptosis, and provides evidence supporting the combined administration of these drugs. Other in vitro studies have demonstrated that metformin reduces the percentage of TNBC stem cells through mechanisms that downregulate Krüppel-like factor 5 (KLF5) and target its degradation.123 The downregulation of KLF5 is mediated by glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK3β) and inhibition of protein kinase A activity in TNBC cells. KLF5 is a crucial stem cell transcription factor in basal-type TNBC cells, and it promotes TNBC cell proliferation, survival, migration, invasiveness and stemness.124–126 The reduced TNBC stem cell viability observed in vitro has significant consequences which need to be evaluated further in in vivo animal models. Metformin also has been shown to downregulate fatty acid synthase (FASN) levels via miR-193b in TNBC cells. FASN is an essential component of de novo fatty acid synthesis and is thus necessary for the survival of TNBC cells.127

Despite the beneficial anti-tumour potential of metformin in TNBC, other studies have suggested that this effect is reduced by higher glucose concentrations.128–130 Recently, Varghese et al. show that TNBC cell lines exposed to glucose levels in the diabetic range significantly abolished the effect of metformin on cell proliferation, cell death and cell cycle arrest. This study also showed that metformin was most effective and inhibited the mTOR pathway under glucose starvation conditions; suggesting that it should be combined with inhibitors of the glycolytic pathway for more beneficial treatment of TNBC in diabetic patients.129 In view of the mechanistic evidence linking the anti-proliferative effect of metformin to glucose concentration in TNBC, it is natural to advocate stringent glucose level monitoring in BC patients with diabetes, particularly as the hyperglycaemic state may further fuel malignant cell proliferation. The anti-cancer effects of metformin are not limited to triple-negative and ER+ BC subtypes. Metformin is also effective against HER2+ BC since it confers anti-proliferative effects in females with HER2+ BC co-expressed with ER+ with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS).131 Nonetheless, the molecular mechanisms behind these findings are inadequately explained.

Clearly, the use of metformin in the management of BC requires further evaluation. Preliminary population-based studies have shown that metformin does not affect BC staging in older women with long-standing diabetes.132 These findings contrast with both the short-term window of opportunity studies and with functional research highlighted earlier that show an effect of metformin on tumour growth characteristics.

Non-specific effects and limitations of metformin in BC

Like many other chemotherapy agents currently in use, the development of multidrug resistance by cancer cells proves to be a considerable challenge for clinicians. Interestingly, some studies have suggested that metformin may prevent multiple drug resistance (MDR) and may even re-sensitise cancer cells to standard chemotherapy agents to which they were once sensitive. In vitro and in vivo animal studies show that metformin reduces the expression of several proteins that cause MDR.133 Metformin also has MDR reversing properties in BC cell lines and re-sensitises cells to 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), adriamycin and paclitaxel through the activation of AMPL and mTOR pathways.134,135 In addition, it has been shown to modulate the metabolic and miRNA profile of chemoresistant cells, rendering them similar to chemosensitive BC cell populations.136 Other investigators have demonstrated that co-treatment of BC cells with metformin and flavone inhibits cell viability and increases apoptosis of cancer cells more effectively compared with metformin or flavone alone.137 This potentiation of apoptosis is achieved by the modulation of MDMX/p53 proteins through PI3K/AKT pathways.

Conversely, chronic exposure to metformin has been shown to lead to the development of resistance in BC cell lines. Acquired resistance to metformin is accompanied by transcriptomic changes that generate a metastatic stem-cell like phenotype.138 In addition, it has been shown that long-term treatment with metformin can lead to the development of cross-resistance to both metformin and tamoxifen in MCF-7 cells.139 Scherbakov et al.117 show that the acquired resistance to both drugs is based on the constitutive activation of Akt/Snail1/E-cadherin signalling pathways.

Why metformin confers anti-tumour effects in some, but not all BC cases is not clear. The AMPK-activating ability of metformin is central to its metabolic function in cells. Buac et al.104 show that breast cancer-associated gene 2 (BCA2) is an endogenous inhibitor of AMPK activation in BC cells. BCA2 encodes a RING-finger-containing ubiquitin E3 ligase that is expressed in about 50% of breast tumours. This gene has been associated with both in vitro BC cell proliferation and clinical outcome.140 Inhibition of BCA2 enhances the growth inhibitory effect of metformin in cell models, thus suggesting that metformin co-administration with a BCA2 inhibitor can be a more powerful strategy than metformin therapy in isolation.141

The dose of metformin required to achieve a therapeutic effect is similarly controversial. Several doses have been used in studies with varying clinical effects. In fact, Schexnayder et al.142 showed that metformin at pharmacologically achievable concentrations does not significantly improve the viability of BC cells. Instead, it inhibits inflammatory signalling and metastatic progression of the disease through reduced ICAM1, COX2, PGE2 and ROS levels. Cell cycle arrest and decreased cell viability were only reported at higher concentrations of metformin.

The mechanistic findings from preclinical in vitro research are not directly translatable to clinical practice. A recent meta-analysis of observational studies on the effect of metformin on the incidence and all-cause mortality of BC in patients with type 2 diabetes failed to identify a significant association between metformin exposure and incidence of BC, while a 45% risk reduction for all-cause mortality was observed.112 The uncertainty regarding the optimal dosage, duration of therapy and whether additional drugs should be co-administered with metformin to achieve synergistic effect further limits its clinical use. An ongoing phase II randomised clinical trial (NCT01589367) aims to investigate the effect of the aromatase inhibitor letrozole with metformin in postmenopausal patients with ER + BC.143 Further such studies are required in order to formulate guidelines to advise clinicians on the possible therapeutic implementation of metformin in BC.

This review on metformin therapy in BC has several limitations. Primarily, it does not aim to provide a systematic review of all mechanistic and epidemiologic evidence on the subject. Several authors have compiled evidence from individual studies in an attempt to resolve discrepancies and inconsistencies between different investigations, and selected key publications are summarised in Tables 1 and 2. The extent of heterogeneity and discordant findings among individual studies is significant and serves to highlight the complexity of the subject. Second, the link between metformin exposure and BC is unlikely to be a simple cause–effect relation. BC, glucose metabolism and the pharmacodynamics of metformin represent cellular events that are intrinsically heterogeneous and multidimensional and that are not fully elucidated. The interplay between each element of this complex interaction depends on various genetic, epigenetic and lifestyle factors that cannot be fully quantified and might not be faithfully reproduced in invitro preclinical studies. In the era of precision medicine and single-cell tumour biology, it is essential for researchers to acknowledge disease heterogeneity and functional diversity within solid tumours as this can significantly impact on clinical outcomes.

Conclusion and future directions

BC is an etiologically complex devastating disease driven by a combination of genetic, reproductive, hormonal and environmental factors. The epidemiologic link between BC and disordered glucose metabolism is mechanistically interesting, given that glucose is an essential cellular metabolic substrate and that insulin signalling has mitogenic effects. The common underlying mechanism uniting T2DM and BC involves hyperinsulinemia, which activates several molecular pathways driving cell proliferation.144 BC has been traditionally treated with a combination of chemotherapy, surgery and targeted hormonal therapy; however, growing interest lies in the use of metformin. Metformin activates AMP-activated protein kinase and inhibits mTOR pathways, thereby decreasing insulin levels in the circulation. In addition, it also inhibits the proliferation and invasion of cancer cells, which could limit metastatic spread. Studies have also demonstrated that metformin may enable cancer cells to overcome the development of resistance to chemotherapy, hormone therapy and trastuzumab treatment.

The use of metformin in the management of both T2DM and BC may seem practical considering that metformin is one of the most commonly prescribed oral anti-diabetic agents. It accounts for 40% of all anti-diabetic drugs dispensed in England over the past few decades, but only 7% of the costs.145 The recent ALTTO trial on metformin use in HER2+ BC showed that metformin may improve the worse prognosis that is associated with diabetes and insulin treatment in patients with HER2+ and hormone receptor positive BC.146 Furthermore, promising in vivo studies suggest that metformin can have beneficial synergistic effects with natural anti-tumour compounds such as curcumin.147 Meta-analysis of large cohorts have demonstrated that metformin use is associated with improved survival and decreased all-cause mortality in diabetic patients with BC.148,149 Conversely, conflicting clinical findings with regard to the efficacy and anti-tumour role of metformin have been reported in the literature, thus strengthening the need for further research.132,150

The potential for therapeutic benefits of metformin in diabetics with BC is rapidly becoming an area of interest in both clinical oncology and endocrinology. However, more long-term double blinded-randomised trials are needed to explore the precise role which metformin may play and its possible use as an adjuvant in clinical practice. Most current studies that examine metformin’s use in BC have reported a mixed picture on its efficacy, which could be due to the different doses of metformin as well as varying periods of follow-up used in these studies. It is clear that metformin holds considerable promise with regard to a potential anti-tumour role.

Footnotes

Author contribution: All the authors contributed equally to this work.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Mohsin HK Roshan  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4555-8596

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4555-8596

Nikolai P Pace  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7332-874X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7332-874X

References

- 1. Tao Z, Shi A, Lu C, et al. Breast cancer: epidemiology and etiology. Cell Biochem Biophys 2015; 72: 333–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Svendsen RP, Paulsen MS, Larsen PV, et al. Associations between reporting of cancer alarm symptoms and socioeconomic and demographic determinants: a population-based, cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2012; 12: 686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vernon SW, Vogel VG, Halabi S, et al. Factors associated with perceived risk of breast cancer among women attending a screening program. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1993; 28(2): 137–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Porta C, Paglino C, Mosca A. Targeting PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling in cancer. Front Oncol 2014; 4: 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Verkooijen HM, Fioretta G, Vlastos G, et al. Important increase of invasive lobular breast cancer incidence in Geneva, Switzerland. Int J Cancer 2003; 104(6): 778–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maher M. Current and emerging treatment regimens for HER2-positive breast cancer. P T Peer-Rev J Formul Manag 2014; 39(3): 206–212. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kasznicki J, Sliwinska A, Drzewoski J. Metformin in cancer prevention and therapy. Ann Transl Med 2014; 2: 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Aljada A, Mousa SA. Metformin and neoplasia: implications and indications. Pharmacol Ther 2012; 133(1): 108–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alimova IN, Liu B, Fan Z, et al. Metformin inhibits breast cancer cell growth, colony formation and induces cell cycle arrest in vitro. Cell Cycle 2009; 8(6): 909–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ben Sahra I, Laurent K, Loubat A, et al. The antidiabetic drug metformin exerts an antitumoral effect in vitro and in vivo through a decrease of cyclin D1 level. Oncogene 2008; 27(25): 3576–3586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hosono K, Endo H, Takahashi H, et al. Metformin suppresses azoxymethane-induced colorectal aberrant crypt foci by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Mol Carcinog 2010; 49(7): 662–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maayah ZH, Ghebeh H, Alhaider AA, et al. Metformin inhibits 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene-induced breast carcinogenesis and adduct formation in human breast cells by inhibiting the cytochrome P4501A1/aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling pathway. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2015; 284(2): 217–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bojková B, Garajová M, Kajo K, et al. Pioglitazone in chemically induced mammary carcinogenesis in rats. Eur J Cancer Prev 2010; 19: 379–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tseng C-H. Rosiglitazone reduces breast cancer risk in Taiwanese female patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Oncotarget 2016; 8: 3042–3048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Monami M, Dicembrini I, Mannucci E. Thiazolidinediones and cancer: results of a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Acta Diabetol 2014; 51(1): 91–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zi F, Zi H, Li Y, et al. Metformin and cancer: an existing drug for cancer prevention and therapy. Oncol Lett 2018; 15(1): 683–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Benjamin D, Robay D, Hindupur SK, et al. Dual inhibition of the lactate transporters MCT1 and MCT4 is synthetic lethal with metformin due to NAD+ depletion in cancer cells. Cell Rep 2018; 25(11): 3047–3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. DeNardo DG, Coussens LM. Inflammation and breast cancer. Balancing immune response: crosstalk between adaptive and innate immune cells during breast cancer progression. Breast Cancer Res 2007; 9(4): 212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature 2002; 420: 860–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Romagnani S. The Th1/Th2 paradigm. Immunol Today 1997; 18: 263–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hu HM, Urba WJ, Fox BA. Gene-modified tumor vaccine with therapeutic potential shifts tumor-specific T cell response from a type 2 to a type 1 cytokine profile. J Immunol 1998; 161(6): 3033–3041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Grusby MJ, Clements VK. Cutting edge: STAT6-deficient mice have enhanced tumor immunity to primary and metastatic mammary carcinoma. J Immunol 2000; 165(11): 6015–6019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pellegrini P, Berghella AM, Del Beato T, et al. Disregulation in TH1 and TH2 subsets of CD4+ T cells in peripheral blood of colorectal cancer patients and involvement in cancer establishment and progression. Cancer Immunol Immunother 1996; 42(1): 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tsung K, Meko JB, Peplinski GR, et al. IL-12 induces T helper 1-directed antitumor response. J Immunol 1997; 158(7): 3359–3365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Russo J, Tahin Q, Lareef MH, et al. Neoplastic transformation of human breast epithelial cells by estrogens and chemical carcinogens. Environ Mol Mutagen 2002; 39(2–3): 254–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kleer CG, Cao Q, Varambally S, et al. EZH2 is a marker of aggressive breast cancer and promotes neoplastic transformation of breast epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003; 100(20): 11606–11611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cannata D, Fierz Y, Vijayakumar A, et al. Type 2 diabetes and cancer: what is the connection? Mt Sinai J Med 2010; 77: 197–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shlomai G, Neel B, LeRoith D, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and cancer: the role of pharmacotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34(35): 4261–4269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tsilidis KK, Kasimis JC, Lopez DS, et al. Type 2 diabetes and cancer: umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies. BMJ 2015; 350: g7607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Giovannucci E, Harlan DM, Archer MC, et al. Diabetes and cancer: a consensus report. Diabetes Care 2010; 33: 1674–1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ballotari P, Vicentini M, Manicardi V, et al. Diabetes and risk of cancer incidence: results from a population-based cohort study in northern Italy. BMC Cancer 2017; 17(1): 703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hou G, Zhang S, Zhang X, et al. Clinical pathological characteristics and prognostic analysis of 1,013 breast cancer patients with diabetes. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2013; 137(3): 807–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Renehan AG, Yeh H-C, Johnson JA, et al. Diabetes and cancer (2): evaluating the impact of diabetes on mortality in patients with cancer. Diabetologia 2012; 55(6): 1619–1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bronsveld HK, Jensen V, Vahl P, et al. Diabetes and breast cancer subtypes. PLoS ONE 2017; 12: e0170084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schrauder MG, Fasching PA, Haberle L, et al. Diabetes and prognosis in a breast cancer cohort. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2011; 137(6): 975–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Panno ML, Salerno M, Pezzi V, et al. Effect of oestradiol and insulin on the proliferative pattern and on oestrogen and progesterone receptor contents in MCF-7 cells. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 1996; 122(12): 745–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bronsveld HK, ter Braak B, Karlstad O, et al. Treatment with insulin (analogues) and breast cancer risk in diabetics; a systematic review and meta-analysis of in vitro, animal and human evidence. Breast Cancer Res 2015; 17: 100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tseng C-H. Prolonged use of human insulin increases breast cancer risk in Taiwanese women with type 2 diabetes. BMC Cancer 2015; 15: 846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Overbeek JA, van Herk-Sukel MPP, Vissers PAJ, et al. Type 2 diabetes, but not insulin (analog) treatment, is associated with more advanced stages of breast cancer: a national linkage of cancer and pharmacy registries. Diabetes Care 2019; 42: 434–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Federici M, Porzio O, Zucaro L, et al. Increased abundance of insulin/IGF-I hybrid receptors in adipose tissue from NIDDM patients. Mol Cell Endocrinol 1997; 135(1): 41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pandini G, Vigneri R, Costantino A, et al. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) receptor overexpression in breast cancers leads to insulin/IGF-I hybrid receptor overexpression: evidence for a second mechanism of IGF-I signaling. Clin Cancer Res 1999; 5(7): 1935–1944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Xue F, Michels KB. Diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and breast cancer: a review of the current evidence. Am J Clin Nutr 2007; 86(3): 823–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shao S, Gill AA, Zahm SH, et al. Diabetes and overall survival among breast cancer patients in the U.S. Military Health System. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2018; 27(1): 50–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wairagu PM, Phan ANH, Kim M-K, et al. Insulin priming effect on estradiol-induced breast cancer metabolism and growth. Cancer Biol Ther 2015; 16(3): 484–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Madak-Erdogan Z, Lupien M, Stossi F, et al. Genomic collaboration of estrogen receptor alpha and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 in regulating gene and proliferation programs. Mol Cell Biol 2011; 31(1): 226–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Marquez DC, Pietras RJ. Membrane-associated binding sites for estrogen contribute to growth regulation of human breast cancer cells. Oncogene 2001; 20(39): 5420–5430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Haffner SM. Sex hormone-binding protein, hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance and noninsulin-dependent diabetes. Horm Res 1996; 45(3–5): 233–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fan W, Yanase T, Morinaga H, et al. Insulin-like growth factor 1/insulin signaling activates androgen signaling through direct interactions of Foxo1 with androgen receptor. J Biol Chem 2007; 282(10): 7329–7338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lipworth L, Adami HO, Trichopoulos D, et al. Serum steroid hormone levels, sex hormone-binding globulin, and body mass index in the etiology of postmenopausal breast cancer. Epidemiology 1996; 7(1): 96–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lin C-W, Yang L-Y, Shen S-C, et al. IGF-I plus E2 induces proliferation via activation of ROS-dependent ERKs and JNKs in human breast carcinoma cells. J Cell Physiol 2007; 212(3): 666–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cleary MP, Grossmann ME. Obesity and breast cancer: the estrogen connection. Endocrinology 2009; 150(6): 2537–2542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mauro L, Salerno M, Panno ML, et al. Estradiol increases IRS-1 gene expression and insulin signaling in breast cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2001; 288(3): 685–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Joung KH, Jeong J-W, Ku BJ. The association between type 2 diabetes mellitus and women cancer: the epidemiological evidences and putative mechanisms. Biomed Res Int 2015; 2015: 920618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Purohit A, Newman SP, Reed MJ. The role of cytokines in regulating estrogen synthesis: implications for the etiology of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 2002; 4(2): 65–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Godsland IF. Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinaemia in the development and progression of cancer. Clin Sci 2009; 118(5): 315–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wisastra R, Dekker FJ. Inflammation, cancer and oxidative lipoxygenase activity are intimately linked. Cancers 2014; 6(3): 1500–1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ferroni P, Riondino S, Buonomo O, et al. Type 2 diabetes and breast cancer: the interplay between impaired glucose metabolism and oxidant stress. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2015; 2015: 183928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Parri M, Chiarugi P. Redox molecular machines involved in tumor progression. Antioxid Redox Signal 2012; 19: 1828–1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hou Y, Zhou M, Xie J, et al. High glucose levels promote the proliferation of breast cancer cells through GTPases. Breast Cancer 2017; 9: 429–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Duan W, Shen X, Lei J, et al. Hyperglycemia, a neglected factor during cancer progression. Biomed Res Int 2014; 2014: 461917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ryu TY, Park J, Scherer PE. Hyperglycemia as a risk factor for cancer progression. Diabetes Metab J 2014; 38(5): 330–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Okumura M, Yamamoto M, Sakuma H, et al. Leptin and high glucose stimulate cell proliferation in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells: reciprocal involvement of PKC-alpha and PPAR expression. Biochim Biophys Acta 2002; 1592(2): 107–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lopez V, Kelleher SL. Zip6-attenuation promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in ductal breast tumor (T47D) cells. Exp Cell Res 2010; 316(3): 366–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Takatani-Nakase T, Matsui C, Maeda S, et al. High glucose level promotes migration behavior of breast cancer cells through zinc and its transporters. PLoS ONE 2014; 9(2): e90136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Soranna D, Scotti L, Zambon A, et al. Cancer risk associated with use of metformin and sulfonylurea in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Oncologist 2012; 17(6): 813–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Maida A, Lamont BJ, Cao X, et al. Metformin regulates the incretin receptor axis via a pathway dependent on peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α in mice. Diabetologia 2011; 54: 339–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Argaud D, Roth H, Wiernsperger N, et al. Metformin decreases gluconeogenesis by enhancing the pyruvate kinase flux in isolated rat hepatocytes. Eur J Biochem 1993; 213(3): 1341–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Mithieux G, Guignot L, Bordet J-C, et al. Intrahepatic mechanisms underlying the effect of metformin in decreasing basal glucose production in rats fed a high-fat diet. Diabetes 2002; 51(1): 139–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Radziuk J, Zhang Z, Wiernsperger N, et al. Effects of metformin on lactate uptake and gluconeogenesis in the perfused rat liver. Diabetes 1997; 46(9): 1406–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Shu Y, Sheardown SA, Brown C, et al. Effect of genetic variation in the organic cation transporter 1 (OCT1) on metformin action. J Clin Invest 2007; 117(5): 1422–1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Viollet B, Guigas B, Leclerc J, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase in the regulation of hepatic energy metabolism: from physiology to therapeutic perspectives. Acta Physiol 2009; 196(1): 81–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Zhou G, Myers R, Li Y, et al. Role of AMP-activated protein kinase in mechanism of metformin action. J Clin Invest 2001; 108(8): 1167–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Viollet B, Guigas B, Sanz Garcia N, et al. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of metformin: an overview. Clin Sci 2012; 122(6): 253–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Brunmair B, Staniek K, Gras F, et al. Thiazolidinediones, like metformin, inhibit respiratory complex I: a common mechanism contributing to their antidiabetic actions? Diabetes 2004; 53(4): 1052–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Detaille D, Guigas B, Chauvin C, et al. Metformin prevents high-glucose-induced endothelial cell death through a mitochondrial permeability transition-dependent process. Diabetes 2005; 54(7): 2179–2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. El-Mir M-Y, Detaille D, R-Villanueva G, et al. Neuroprotective role of antidiabetic drug metformin against apoptotic cell death in primary cortical neurons. J Mol Neurosci 2008; 34(1): 77–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. El-Mir MY, Nogueira V, Fontaine E, et al. Dimethylbiguanide inhibits cell respiration via an indirect effect targeted on the respiratory chain complex I. J Biol Chem 2000; 275(1): 223–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Hinke SA, Martens GA, Cai Y, et al. Methyl succinate antagonises biguanide-induced AMPK-activation and death of pancreatic beta-cells through restoration of mitochondrial electron transfer. Br J Pharmacol 2007; 150(8): 1031–1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Owen MR, Doran E, Halestrap AP. Evidence that metformin exerts its anti-diabetic effects through inhibition of complex 1 of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Biochem J 2000; 348(Pt. 3): 607–614. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Batandier C, Guigas B, Detaille D, et al. The ROS production induced by a reverse-electron flux at respiratory-chain complex 1 is hampered by metformin. J Bioenerg Biomembr 2006; 38(1): 33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Kane DA, Anderson EJ, Price JW, 3rd, et al. Metformin selectively attenuates mitochondrial H2O2 emission without affecting respiratory capacity in skeletal muscle of obese rats. Free Radic Biol Med 2010; 49(6): 1082–1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. El-Haggar SM, El-Shitany NA, Mostafa MF, et al. Metformin may protect nondiabetic breast cancer women from metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis 2016; 33(4): 339–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Sadighi S, Saberian M, Nagafi M, et al. Metformin anti-proliferative effect on a cohort of non-diabetic breast cancer patients. Ann Oncol 2016; 27: 200.26483048 [Google Scholar]

- 84. Goodwin PJ, Pritchard KI, Ennis M, et al. Insulin-lowering effects of metformin in women with early breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer 2008; 8(6): 501–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Hadad S, Iwamoto T, Jordan L, et al. Evidence for biological effects of metformin in operable breast cancer: a pre-operative, window-of-opportunity, randomized trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011; 128: 783–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Hadad SM, Coates P, Jordan LB, et al. Evidence for biological effects of metformin in operable breast cancer: biomarker analysis in a pre-operative window of opportunity randomized trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2015; 150(1): 149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Bonanni B, Puntoni M, Cazzaniga M, et al. Dual effect of metformin on breast cancer proliferation in a randomized presurgical trial. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30(21): 2593–2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Cazzaniga M, DeCensi A, Pruneri G, et al. The effect of metformin on apoptosis in a breast cancer presurgical trial. Br J Cancer 2013; 109(11): 2792–2797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. DeCensi A, Puntoni M, Gandini S, et al. Differential effects of metformin on breast cancer proliferation according to markers of insulin resistance and tumor subtype in a randomized presurgical trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2014; 148(1): 81–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Kalinsky K, Crew KD, Refice S, et al. Presurgical trial of metformin in overweight and obese patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Cancer Invest 2014; 32(4): 150–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Goodwin PJ, Parulekar WR, Gelmon KA, et al. Effect of metformin vs placebo on and metabolic factors in NCIC CTG MA.32. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015; 107(3): djv006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Niraula S, Dowling RJO, Ennis M, et al. Metformin in early breast cancer: a prospective window of opportunity neoadjuvant study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012; 135(3): 821–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Dowling RJO, Niraula S, Chang MC, et al. Changes in insulin receptor signaling underlie neoadjuvant metformin administration in breast cancer: a prospective window of opportunity neoadjuvant study. Breast Cancer Res 2015; 17: 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Ko K-P, Ma SH, Yang J-J, et al. Metformin intervention in obese non-diabetic patients with breast cancer: phase II randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2015; 153(2): 361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Jalving M, Gietema JA, Lefrandt JD, et al. Metformin: taking away the candy for cancer. Eur J Cancer 2010; 46(13): 2369–2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. HsiehLi SM, Liu ST, Chang YL, et al. Metformin causes cancer cell death through downregulation of p53-dependent differentiated embryo chondrocyte 1. J Biomed Sci 2018; 25(1): 81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Queiroz EA, Puukila S, Eichler R, et al. Metformin induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest mediated by oxidative stress, AMPK and FOXO3a in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. PLoS ONE 2014; 9(5): e98207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Sharma P, Kumar S. Metformin inhibits human breast cancer cell growth by promoting apoptosis via a. Cell Oncol 2018; 41(6): 637–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Giles ED, Jindal S, Wellberg EA, et al. Metformin inhibits stromal aromatase expression and tumor progression in a rodent model of postmenopausal breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 2018; 20(1): 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Zhu Z, Jiang W, Thompson MD, et al. Metformin as an energy restriction mimetic agent for breast cancer prevention. J Carcinog 2011; 10: 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Checkley LA, Rudolph MC, Wellberg EA, et al. Metformin accumulation correlates with organic cation transporter 2 protein expression and predicts mammary tumor regression in vivo. Cancer Prev Res 2017; 10(3): 198–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Bojkova B, Kajo K, Kubatka P, et al. Metformin and melatonin improve histopathological outcome of NMU-induced mammary tumors in rats. Pathol Res Pract 2019; 215(4): 722–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Corominas-Faja B, Quirantes-Pine R, Oliveras-Ferraros C, et al. Metabolomic fingerprint reveals that metformin impairs one-carbon metabolism in a manner similar to the antifolate class of chemotherapy drugs. Aging 2012; 4(7): 480–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Hirsch HA, Iliopoulos D, Struhl K. Metformin inhibits the inflammatory response associated with cellular transformation and cancer stem cell growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013; 110(3): 972–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Iliopoulos D, Hirsch HA, Struhl K. An epigenetic switch involving NF-kappaB, Lin28, Let-7 MicroRNA, and IL6 links inflammation to cell transformation. Cell 2009; 139(4): 693–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Iliopoulos D, Jaeger SA, Hirsch HA, et al. STAT3 activation of miR-21 and miR-181b-1 via PTEN and CYLD are part of the epigenetic switch linking inflammation to cancer. Mol Cell 2010; 39(4): 493–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Ma J, Guo Y, Chen S, et al. Metformin enhances tamoxifen-mediated tumor growth inhibition in ER-positive breast carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2014; 14: 172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Hadad SM, Hardie DG, Appleyard V, et al. Effects of metformin on breast cancer cell proliferation, the AMPK pathway and the cell cycle. Clin Transl Oncol 2014; 16(8): 746–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Liu H, Scholz C, Zang C, et al. Metformin and the mTOR inhibitor everolimus (RAD001) sensitize breast cancer cells to the cytotoxic effect of chemotherapeutic drugs in vitro. Anticancer Res 2012; 32(5): 1627–1637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Lee H, Park HJ, Park C-S, et al. Response of breast cancer cells and cancer stem cells to metformin and hyperthermia alone or combined. PLoS ONE 2014; 9: e87979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Zhang Z-J, Yuan J, Bi Y, et al. The effect of metformin on biomarkers and survivals for breast cancer- a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Pharmacol Res 2019; 141: 551–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Tang GH, Satkunam M, Pond GR, et al. Association of metformin with breast cancer incidence and mortality in patients with type II diabetes: a GRADE-assessed systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2018; 27(6): 627–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Coyle C, Cafferty FH, Vale C, et al. Metformin as an adjuvant treatment for cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol off J Eur Soc Med Oncol 2016; 27: 2184–2195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Zhou Y, Zhang X, Gu C, et al. Diabetes mellitus is associated with breast cancer: systematic review, meta-analysis, and in silico reproduction. Panminerva Med 2015; 57(3): 101–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Gandhi S, Fletcher GG, Eisen A, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for early female breast cancer: a systematic review of the evidence for the 2014 Cancer Care Ontario systemic therapy guideline. Curr Oncol 2015; 22(Suppl. 1): S82–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Gandini S, Puntoni M, Heckman-Stoddard BM, et al. Metformin and cancer risk and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis taking into account biases and confounders. Cancer Prev Res 2014; 7(9): 867–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]