Summary

Tomato apex necrosis virus (ToANV, species Tomato marchitez virus, genus Torradovirus, family Secoviridae) causes a severe tomato disease in Mexico. One distinctive feature of torradoviruses compared with other members of the family Secoviridae is the presence of an additional open reading frame (ORF) in genomic RNA2 (denominated RNA2‐ORF1), located upstream of ORF2. RNA2‐ORF2 encodes a polyprotein that is processed into a putative movement protein and three capsid proteins (CPs). The RNA2‐ORF1 protein has homologues only amongst other torradoviruses and, so far, no function has been associated with it. We used recombinant and mutant ToANV clones to investigate the role of the RNA2‐ORF1 protein in various aspects of the virus infection cycle. The lack of a functional RNA2‐ORF1 resulted in an inability to systemically infect Nicotiana benthamiana and tomato plants, but both positive‐ and negative‐strand RNA1 and RNA2 accumulated locally in agroinfiltrated areas in N. benthamiana plants, indicating that the RNA2‐ORF1 mutants were replication competent. Furthermore, a mutant with a deletion in RNA2‐ORF1 was competent for virion formation and cell‐to‐cell movement in the cells immediately surrounding the initial infection site. However, immunological detection of the ToANV CPs in the agroinfiltrated areas showed that this mutant was not detected in the sieve elements even if the surrounding parenchymatic cells were ToANV positive, suggesting a role for the RNA2‐ORF1 protein in processes occurring prior to phloem uploading, including efficient spread in inoculated leaves.

Keywords: long distance, Secoviridae, tomato apex necrosis virus, Torradovirus

Introduction

Torradoviruses are plant viruses belonging to the genus Torradovirus, family Secoviridae (Sanfacon et al., 2009). This group of viruses was characterized only at the beginning of the 21st century on identification of the aetiological agents of at least three tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) diseases from Spain (Verbeek et al., 2007), Mexico (Turina et al., 2007; Verbeek et al., 2008) and Guatemala (Batuman et al., 2010; Verbeek et al., 2010). These viruses showed similar necrotic symptoms in a number of tomato varieties. The diseases were shown to be caused by distinct viruses: tomato torrado virus (ToTV), tomato apex necrosis virus (ToANV) and tomato marchitez virus (ToMarV), as well as tomato chocolate virus (ToChV) and tomato chocolate spot virus (ToChSV) (Thompson et al., 2017). Two distinct viruses are members of the species Tomato marchitez virus: ToMarV (Verbeek et al., 2007) and ToANV (Turina et al. 2007). An uncharacterized virus causing disease on tomato in the Imperial Valley of California since the early 1980s (Larsen et al., 1984) has recently been shown to be another torradovirus, possibly inside the Tomato marchitez virus species (Wintermantel and Hladky, 2013). The same virus is still present in southern California in common weeds (Wintermantel et al., 2016).

After the initial discovery of tomato‐infecting torradoviruses, a number of new torradovirus species were characterized and shown to cause diseases in lettuce in the Netherlands (Verbeek et al., 2014), in carrot crops in the UK (Adams et al., 2014), in motherwort in China (Seo et al., 2015), in cassava in Colombia (Carvajal‐Yepes et al., 2014) and, more recently, in various cucurbits in Sudan (Lecoq et al., 2016).

Tomato‐infecting torradoviruses are an increasing concern for tomato growers, and understanding their biology is fundamental for the development of effective and environmentally sound control strategies (including the deployment of available resistant varieties). A number of studies have examined the epidemiology of tomato‐infecting torradoviruses and have identified whiteflies of three distinct genera that are capable of transmitting these viruses (van der Vlugt et al., 2015). Torradoviruses have a bipartite positive‐strand RNA genome of c. 7 kb (RNA1) and 5 kb (RNA2). Genomic RNAs are encapsidated in isometric virions of c. 30 nm in diameter with a capsid composed of three distinct capsid proteins (CPs): VP35, VP26 and VP24. RNA1 contains a single open reading frame (ORF) which encodes a polyprotein that is processed by virus‐encoded proteases into an RNA‐dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), a helicase and, possibly, two proteases (3C‐like protease and a protease cofactor domain) (van der Vlugt et al., 2015). RNA2 is unique in the family Secoviridae, as it encodes two ORFs. RNA2‐ORF1 is predicted to encode a small protein of 20.4–26 kDa in the different torradovirus species. This predicted protein has homologues only in the torradoviruses, and the percentage identity of aligned proteins varies from 61.5% to 76.5% amongst the tomato‐infecting torradoviruses, and 21.8% to 54.7% amongst the other torradoviruses; nevertheless, a number of core domains based on identical residues are shared amongst all the sequenced torradoviruses (van der Vlugt et al., 2015). RNA2‐ORF2 encodes a polyprotein which is processed by virus‐encoded proteases, yielding a predicted movement protein (MP) and the three distinct CPs (Ferriol et al., 2016a). So far, there is no experimental evidence of the translational strategy to express RNA2‐ORF2 from the bicistronic torradovirus RNA2.

Infectious clones have been derived recently for two distinct torradoviruses. The first, assembled for ToTV (Wieczorek et al., 2015), has been used recently to show that a single amino acid substitution in the MP of ToTV is a necrosis‐inducing pathogenicity determinant during tomato infection (Wieczorek and Obrepalska‐Steplowska, 2016b). Moreover, the N‐terminal fragment of the ToTV RNA1‐encoded polyprotein induces a hypersensitive response (HR)‐like in Nicotiana benthamiana plants (Wieczorek and Obrepalska‐Steplowska, 2016a). Infectious clones have also been generated for ToANV, previously named tomato marchitez virus isolate M (Ferriol et al., 2016a, b), and have been shown to have the ability to initiate infection via agroinfiltration. This resulted in symptoms indistinguishable from those of wild‐type (WT) infection, and the progeny were whitefly transmissible (Ferriol et al., 2016a). A ToANV infectious construct expressing the green fluorescent protein (GFP) was also derived (Ferriol et al., 2016a) and was used to monitor ToANV movement in the inoculated leaf. Furthermore, the ToANV cDNA infectious clones were used to locate the cleavage sites of the ToANV RNA2‐encoded polyprotein (Ferriol et al., 2016b).

The purpose of this work was to determine the role of the RNA2‐ORF1 protein in the ToANV infection cycle. Our data show that RNA2‐ORF1 (and its encoded protein) is dispensable for replication, cell‐to‐cell movement and virion formation, but is required for systemic infection of both tomato and N. benthamiana plants. We show that the RNA2‐ORF1 protein has a role in processes occurring after initial cell‐to‐cell movement, but prior to phloem loading.

Results

The RNA2‐ORF1 protein is required for systemic infection of N. benthamiana and tomato plants

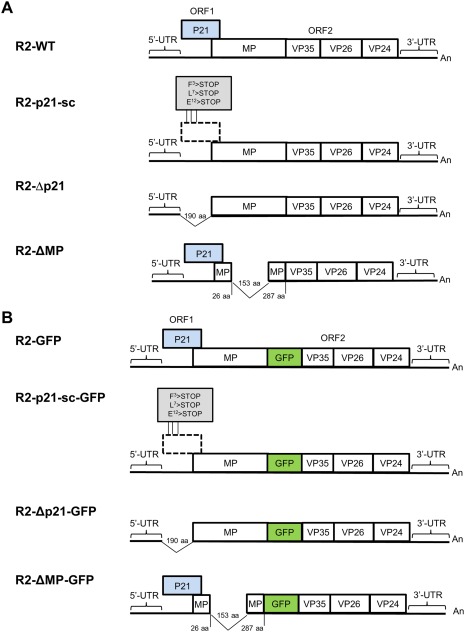

We have shown previously that an Agrobacterium tumefaciens‐mediated inoculation system for ToANV is useful for the study of the viral infection cycle (Ferriol et al., 2016a). Here, we generated two different RNA2‐ORF1 (referred to as p21 for the ToANV plasmid construct nomenclature used in this study) mutants: three stop codons were inserted downstream from the RNA2‐ORF1 start codon yielding mutant R2‐p21‐sc (Fig. 1A) and a deletion of most of RNA2‐ORF1 was made to yield mutant R2‐Δp21 (Fig. 1A). We inoculated each mutant construct in combination with the WT R1 construct and, as a control, we inoculated WT R1‐ and WT R2‐expressing plasmids together. We monitored local and systemic infection in plants by western blot or double antibody sandwich‐enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (DAS‐ELISA) at 4, 8 and 15 days post‐inoculation (dpi). All the N. benthamiana and tomato plants inoculated with WT ToANV clones were systemically infected by 8 dpi, whereas neither of the RNA2‐ORF1 mutants produced systemic infection in either type of plant host (Table 1). Even when plants were left for 60 days, no systemic infection was detected for the RNA2‐ORF1 mutants (data not shown). In addition, we confirmed that there was no reversion to the ToANV‐WT sequence in the leaves agroinfiltrated with the R2‐p21‐sc construct (data not shown). Overall, these results showed that the RNA2‐ORF1‐encoded protein is required for systemic infection in both N. benthamiana and tomato plants (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Constructs used in this study. Schematic representation of pJL89‐M‐R2 (R2‐WT, A), pJL89‐M‐R2‐GFP (R2‐GFP, B) (Ferriol et al., 2016a) and the series of RNA2 mutant constructs used in this study (A and B). The RNA genome is depicted with horizontal lines. Boxes indicate open reading frames (ORFs) and the relative positions of regions encoding the RNA2‐ORF1 protein (P21, represented with a blue box), and the regions encompassing a putative movement protein (MP) and the three capsid proteins (VP35, VP26, VP24). The 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) are shown as black lines highlighted by horizontal parentheses. The polyadenylated tail is shown at the 3′ end of the RNA (An). The positions of the stop codons introduced in R2‐p21‐sc and R2‐p21‐sc‐GFP are highlighted in a grey box. Further details of the tomato apex necrosis virus (ToANV) RNA2 deletion mutants are provided in the graphic representation. GFP, green fluorescent protein; aa, amino acid.

Table 1.

Number of Nicotiana benthamiana and tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) plants infected with tomato apex necrosis virus (ToANV) after agroinfiltration with ToANV wild‐type (WT) or RNA2‐ORF1 protein mutants.

| Host | Constructs * | Experiments † | Local 4 dpa ‡ | Systemic 15 dpa ‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nicotiana benthamiana | R1+R2 | 3 | 4/4 | 14/14 |

| R1+R2‐p21‐sc | 3 | 7/7 | 0/23 | |

| R1+R2‐Δp21 | 3 | 7/7 | 0/23 | |

| Solanum lycopersicum | R1+R2 | 2 | NT § | 11/11 |

| R1+R2‐p21‐sc | 2 | NT | 0/24 | |

| R1+R2‐Δp21 | 2 | NT | 0/24 |

*Constructs agroinfiltrated in N. benthamiana and S. lycopersicum plants: ToANV wild‐type virus (R1 and R2) and ToANV RNA2‐ORF1 protein mutants (R2‐p21‐sc and R2‐Δp21).

†Number of experiments.

‡Number of total plants infected divided by the number of total plants tested at different time points in three different experiments for N. benthamiana and two distinct experiments for S. lycopersicum. ToANV infection was detected by western blot or double antibody sandwich‐enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (DAS‐ELISA) in the agroinfiltrated (local) and upper non‐inoculated (systemic) leaves. dpa, days post‐agroinfiltration.

§NT, not tested as a result of a strong necrotic response in tomato agroinfiltrated leaves.

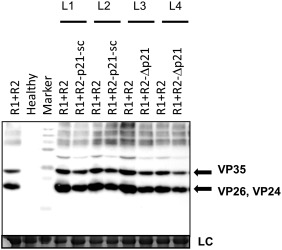

The RNA2‐ORF1 protein is not required for ToANV replication

Given the inability of the RNA2‐ORF1 mutants to infect plants systemically, we analysed the agroinfiltrated areas for ToANV replication and protein accumulation. We first tested the accumulation of positive‐ and negative‐strand RNAs in agroinfiltrated areas in N. benthamiana plants. Northern blot analysis (Fig. 2A,B) showed that both positive‐ and negative‐strand RNA1 and RNA2 accumulated in leaf areas agroinfiltrated with the WT or the RNA2‐ORF1 mutant constructs, demonstrating that the RNA2‐ORF1 protein is not necessary for ToANV replication. Western blot analysis confirmed the accumulation of ToANV CPs during infection with WT or the RNA2‐ORF1 mutants, indirectly demonstrating that translation of RNA2‐ORF2 and processing of its encoded polyprotein to give the three CPs does not require a full‐length RNA2‐ORF1 or the RNA2‐ORF1‐encoded protein (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Northern blot analysis of Nicotiana benthamiana plants locally agroinfiltrated with tomato apex necrosis virus (ToANV) wild‐type (WT) and RNA2‐ORF1 mutant. Total RNA from agroinfiltrated areas of leaves of N. benthamiana plants was analysed by northern hybridization. Samples represent biological replicates of ToANV WT infectious cDNA clones (R1+R2, A and B), ToANV RNA2‐Δp21 mutant (R1+R2‐Δp21, A) and ToANV RNA2‐p21‐sc mutant (R1+R2‐p21‐sc, B). Positions of RNA2 WT [4897 nucleotides (nt)], RNA2‐p21‐sc mutant (4897 nt) and RNA2‐Δp21 mutant (4365 nt) are shown with an arrow. RNA2 was absent in N. benthamiana healthy plants. Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) is indicated with an asterisk. Methylene blue‐stained rRNA loading control is indicated. L1–L4 represent four biological replicates, and each pair of WT and RNA2‐ORF1 mutants came from the same leaf (half leaf inoculated with the WT sample, and half leaf with the null mutant sample). Film exposure times are indicated in hours (h) next to each panel.

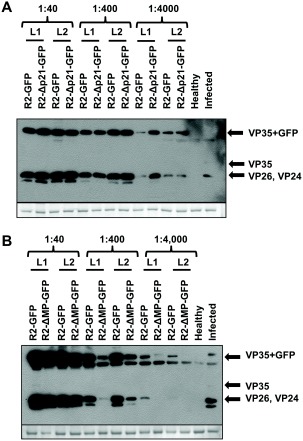

Figure 3.

Western blot analyses of Nicotiana benthamiana plants infected with tomato apex necrosis virus (ToANV) wild‐type (WT) and RNA2‐ORF1 mutant using anti‐ToANV capsid protein (CP) antibodies. The ToANV WT infectious cDNA clones (R1+R2‐WT) showed the presence of two distinct bands (highlighted by arrows) representing the three CPs of ToANV (VP35, VP26 and VP24). The RNA2‐ORF1 null mutants (R2‐p21‐sc and R2‐Δp21) showed the expression of the three CPs when agroinfiltrated in combination with the construct expressing ToANV RNA1 (R1). CPs were absent in N. benthamiana healthy plants. Coomassie blue staining of the loading controls is indicated with LC. Marker, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) ruler ladder (Thermo Scientific). L1–L4 represent four biological replicates, and each pair of WT and RNA2‐ORF1 null mutants came from the same leaf (half leaf inoculated with the WT sample, and half leaf with the null mutant sample).

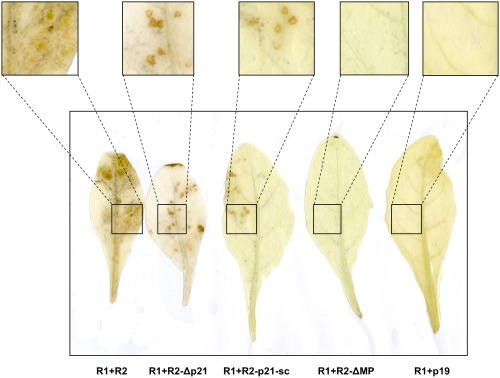

The RNA2‐ORF1 protein is not required for cell‐to‐cell movement or virion formation, but is required for efficient local spread in N. benthamiana

The inability of the replication‐competent ToANV RNA2‐ORF1 mutants to systemically infect plants could be the result of at least two different losses of function: in one case, if the RNA2‐ORF1 protein is required for cell‐to‐cell movement, viral replication would be restricted to initially infected cells following mechanical inoculation with no spread to surrounding cells. This would result in subliminal infections with no detectable amounts of viral RNA or viral protein accumulation in mechanically inoculated leaves, similar to that seen for a cell‐to‐cell movement‐deficient mutant (i.e. R2‐ΔMP, Fig. 1A). In contrast, if the RNA2‐ORF1 protein is not needed for cell‐to‐cell movement, but is required for systemic movement, greater amounts of viral RNAs and proteins would accumulate locally compared with R2‐ΔMP and viral RNAs, and proteins would be present within the inoculated and surrounding cells, but absent in distal leaves. In order to evaluate virus accumulation in leaves mechanically inoculated with WT virus or RNA2‐ORF1 mutants, we needed first to standardize the virus titre in the inocula: for this purpose, we verified virion formation through electron microscopy and estimated indirectly virion concentration by DAS‐ELISA for the CPs in sap extracted from agroinfiltrated areas of N. benthamiana plants (the same plants as would eventually be used as virus source for mechanical inoculation). We also included a ToANV MP deletion mutant (R2‐ΔMP) as a cell‐to‐cell movement‐defective control. In order to obtain movement‐independent local accumulation of virions in the agroinfiltrated leaves, we carried out the agroinfiltrations using saturating suspensions of A. tumefaciens sufficiently concentrated to produce a fairly uniform infection of most of the cells present in the agroinfiltrated areas (estimated through the co‐expression of GFP from a non‐replicative binary plasmid construct or indirectly using the same bacterial suspension concentration with the R1+R2‐GFP constructs); in these experimental conditions, each of the three mutants (R2‐p21‐sc, R2‐Δp21, R2‐ΔMP, Fig. 1) and the WT virus accumulated virions in the N. benthamiana agroinfiltrated leaves (Fig. S1, see Supporting Information). The virion concentration (estimated indirectly from CPs in DAS‐ELISA and from direct virion observation via electron microscopy) in the agroinfiltrated areas was not statistically different (data not shown), indicating that the sap from the agroinfiltrated leaves could be used as standardized inocula for mechanical inoculations.

After ensuring that the inoculum was standardized, we mechanically inoculated N. benthamiana and N. occidentalis plants using sap from agroinfiltrated N. benthamiana plants. RNA2‐ORF1 mutants accumulated to detectable levels in the mechanically inoculated leaves in N. benthamiana plants (Tables 2 and S1, see Supporting Information) and stimulated necrotic local lesion formation in N. occidentalis (Fig. 4). In mechanically inoculated N. benthamiana leaves, RNA2‐ORF1 mutant virus accumulation was lower than WT virus, showing evidence of impaired local spread (Table S1). In contrast, R2‐ΔMP, which is replication compentent, but cell‐to‐cell movement deficient, could not be detected locally in N. benthamiana or stimulate local lesion formation in N. occidentalis after mechanical inoculation [Tables 2 and S2 (see Supporting Information); Fig. 4]. For the RNA2‐ORF1 mutants, mechanical inoculation of N. occidentalis resulted in small and well‐defined local necrotic lesions, but virus accumulation was below our DAS‐ELISA detection limit (Fig. 4; Table S1). In the case of WT virus, local necrotic lesions expanded in the inoculated leaf through concentric necrotic rings and the virus was detected by DAS‐ELISA (Fig. 4; Table S1). To exclude the possibility that local accumulation of the RNA2‐ORF1 mutants in N. benthamiana plants was a result of contamination with WT ToANV, the possible presence of systemic infection (a hallmark of contamination with WT virus) was evaluated at 14 or 21 days post‐mechanical inoculation in the upper non‐inoculated leaves. All tested plants were negative for systemic infection (Tables 2, S1 and S2), demonstrating that the local accumulation observed for the RNA2‐ORF1 mutants was not a result of contamination with WT virus.

Table 2.

Detection of tomato apex necrosis virus (ToANV) wild‐type (WT) and ToANV RNA2‐ORF1 mutants in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves agroinfiltrated or mechanically inoculated with filtered sap from agroinfiltrated areas as source of inoculum.

| Agroinfiltration ‡ | Mechanical ‡ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constructs * | Experiments † | Local 5 dpa § | Systemic 12 dpa § | Local 6 dpi § | Systemic 14 or 21 dpi § |

| R1+R2 | 2 | 10/1 0 | 10/10 | 10/10 | 10/10 |

| R1+R2‐p21‐sc | 2 | 10/10 | 0/10 | 8/9 | 0/9 |

| R1+R2‐Δp21 | 2 | 10/10 | 0/10 | 4/4 | 0/4 |

| R1+R2‐ΔMP | 2 | 10/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 |

| R1 | 2 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/8 | 0/8 |

*Constructs: ToANV wild‐type virus (R1+R2), ToANV RNA2‐ORF1 (R2‐Δp21 and R2‐p21‐sc) and ToANV MP (R2‐ΔMP) mutants.

†Number of experiments.

‡Types of inoculation in N. benthamiana plants. Agroinfiltration: plants were agroinfiltrated with Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Mechanical: plants were inoculated mechanically using filtered sap from agroinfiltrated areas as source of inoculum.

§Number of total plants infected divided by the number of total plants tested in two distinct experiments. dpa, days post‐agroinfiltration; dpi, days post‐mechanical inoculation. As negative controls for cell‐to‐cell movement, ToANV R2‐ΔMP mutant and RNA1 (R1) only were used. ToANV infection was tested by double antibody sandwich‐enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (DAS‐ELISA) in the inoculated (local) and upper non‐inoculated (systemic) leaves. Only samples with a sample/healthy absorbance ratio above three were considered as positive.

Figure 4.

Local necrotic lesions in Nicotiana occidentalis plants inoculated with virions derived from tomato apex necrosis virus (ToANV) wild‐type (WT) and ToANV RNA2‐ORF1, but not with RNA2‐MP deletion mutants. Nicotiana occidentalis leaves were mechanically inoculated with filtered sap from agroinfiltrated N. benthamiana leaves collected at 7 days post‐agroinfiltration. Local lesions on N. occidentalis were observed at 14 days post‐mechanical inoculation. Necrotic local lesions were evident for WT ToANV (R1+R2) and ToANV RNA2‐ORF1 null mutants (R1+R2‐p21‐sc and R1+R2‐Δp21), but not with the RNA2‐MP null mutant (R1+R2‐ΔMP) or the negative control (R1+p19). Insets in the upper part are enlargements of the black boxes in the leaf areas showing or not local lesions.

These results suggested that the RNA2‐ORF1 protein is not required for cell‐to‐cell movement. Nevertheless, its absence results in lower viral accumulation in locally inoculated leaves when compared with the WT virus (Tables S1 and S2).

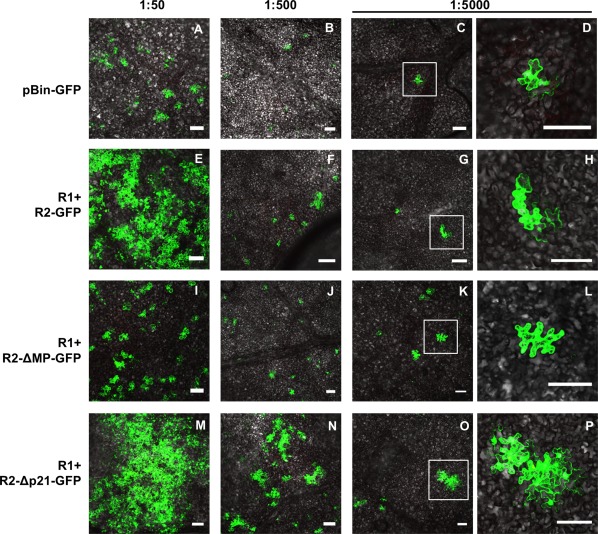

To further confirm the dispensability of the RNA2‐ORF1 protein for cell‐to‐cell movement, we took advantage of a ToANV virus construct expressing GFP from RNA2 (R2‐GFP, Fig. 1B) (Ferriol et al., 2016a). R2‐GFP is capable of cell‐to‐cell movement, but does not result in systemic infection in N. benthamiana plants (Ferriol et al., 2016a). We compared the cell‐to‐cell movement of constructs expressing GFP in combination with a deletion of either RNA2‐ORF1 or the MP (R2‐Δp21‐GFP and R2‐ΔMP‐GFP, respectively, Fig. 1B). Confocal and fluorescent stereomicroscopy showed that both R2‐GFP and R2‐Δp21‐GFP, but not R2‐ΔMP‐GFP, were capable of cell‐to‐cell movement in N. benthamiana plants when using the same concentration of A. tumefaciens cells diluted to the point of originating single infection foci (Fig. 5). Western blot analysis of the agroinfiltrated areas showed no difference in CP accumulation amongst the various binary plasmid constructs at saturating levels of A. tumefaciens cell concentrations (1 : 40). At increasing dilutions (1 : 400 and 1 : 4000), however, CPs accumulated to similar levels for R2‐GFP and R2‐Δp21‐GFP, whereas CP accumulation was diminished for R2‐ΔMP‐GFP (Fig. 6).

Figure 5.

Cell‐to‐cell movement of tomato apex necrosis virus (ToANV) wild‐type (WT) RNA2‐GFP vector and RNA2‐MP‐ and RNA2‐ORF1‐vector mutants in Nicotiana benthamiana epidermal tissue. Agrobacterium tumefaciens suspensions were agroinfiltrated in serial dilutions (1 : 50 to 1 : 5000) into leaves of N. benthamiana plants starting from a suspension adjusted to 0.25 absorbance at 600 nm for each treatment. Groups of cells expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) were evident with the constructs encoding GFP either from the WT RNA2 (R1+R2‐GFP, E to H) or from the RNA2‐ORF1 deletion mutant (R1+R2‐Δp21‐GFP, M to P), suggesting that cell‐to‐cell movement occurred even in the absence of the RNA2‐ORF1 protein. Single‐cell transfection was obtained with the negative controls pBIN‐GFP (A to D) and the RNA2‐MP‐vector mutant (R1+R2‐ΔMP‐GFP, I to L) at 1 : 5000 dilution confirming that ToANV movement protein (MP) is required for cell‐to‐cell movement in N. benthamiana plants. (D), (H), (L) and (P) are enlargements of the areas marked by white square boxes in (C), (G), (K) and (O), respectively. Bars, 100 µm.

Figure 6.

Western blot analyses of Nicotiana benthamiana plants agroinfiltrated with constructs initiating infection of tomato apex necrosis virus (ToANV) wild‐type (WT), R2‐GFP, R2‐ΔMP‐GFP and R2‐Δp21‐GFP using anti‐ToANV‐capsid protein (CP) antibodies. Western blots from leaves of N. benthamiana plants agroinfiltrated with ToANV binary constructs R1+R2‐GFP (A and B), R1+R2‐Δp21‐GFP (A) and R1+R2‐ΔMP‐GFP (B). Agrobacterium tumefaciens suspensions were infiltrated in serial dilutions from 1 : 40 to 1 : 4000 into leaves of N. benthamiana. Coomassie blue staining of the loading controls is shown in the bottom panel. Each lane represents one biological replicate. L1 and L2 refer to two different leaves from the same treatment. Each half leaf was inoculated with the treatment indicated above each lane.

No evidence of the RNA2‐ORF1 protein interfering with the local antiviral silencing machinery in a bioassay

Lack of systemic infection could be a result of failure to overcome a number of plant defence mechanisms, including hormone signalling, expression of defence proteins and protein degradation pathways. One of the most efficient plant defence pathways is that based on post‐transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS) (Hipper et al., 2013): a mobile silencing signal travelling ahead of the infection front which often contributes to the limitation of systemic virus infection (Schwach et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2010); this implies that efficient systemic infection can require efficient suppression of silencing (Hipper et al., 2013). Therefore, to test for possible RNA2‐ORF1 protein‐dependent silencing suppression activity, we performed a common bioassay based on N. benthamiana 16C plants (Voinnet et al., 1999). A plasmid construct expressing RNA2‐ORF1 under the control of the 35S promoter in the context of the ToANV 5′ and 3′ RNA2 untranslated regions (UTRs) (R2‐p21; Fig. S2, see Supporting Information), in combination with a GFP‐expressing construct, was agroinfiltrated into N. benthamiana plants. As controls, a GFP‐expressing plasmid with the silencing suppressor of tomato spotted wilt virus (NSs, positive control) and plasmid pBin61 (negative control, data not shown) were transiently expressed through agroinfiltration into transgenic GFP‐expressing N. benthamiana 16C plants. No suppression activity was observed for the R2‐p21 plasmid construct (Fig. 7A). To verify the expression of the RNA2‐ORF1 protein, we used an RNA2‐ORF1‐FLAG fusion construct (R2‐p21‐FLAG, Fig. S2). Western blot analysis showed that the protein accumulated in the agroinfiltrated area (Fig. S3A, see Supporting Information).

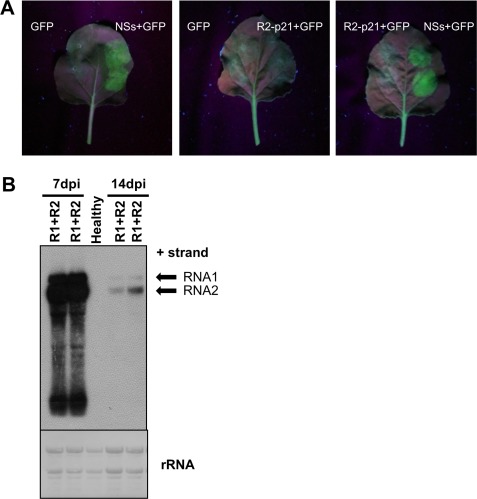

Figure 7.

RNA2‐ORF1 local silencing bioassay. (A) Nicotiana benthamiana 16C plants agroinfiltrated with Agrobacterium tumefaciens infiltrated with binary plasmids expressing the green fluorescent protein pBIN‐GFP (GFP), the silencing suppressor of tomato spotted wilt virus (NSs) and the RNA2‐ORF1 protein (R2‐p21; Fig. S2, see Supporting Information). Each half leaf was inoculated with a different combination of binary plasmids (see labels). (B) Northern blot analysis of N. benthamiana plants infected with wild‐type (WT) tomato apex necrosis virus (ToANV). Total RNA from upper non‐inoculated leaves of N. benthamiana plants infected with WT ToANV infectious cDNA clones (R1+R2) at 7 and 14 days post‐inoculation (dpi). The accumulation of WT ToANV RNA decreased by 14 dpi. Positions of RNA1 and RNA2 are shown with arrows. Methylene blue‐stained ribosomal RNA (rRNA) loading control is indicated. Each lane represents one biological replicate.

Second, we examined the silencing suppression activity during infection with WT ToANV. As with the R2‐p21 construct, no silencing suppression activity was detected in areas in which the virus accumulated (Fig. S3B). Furthermore, monitoring infection over time, N. benthamiana plants infected with WT ToANV showed signs of symptom recovery (data not shown), which is often a hallmark of weak or absent silencing suppressor activity or the results of interaction with host factors (Ghoshal and Sanfacon, 2015). This symptom recovery was paralleled by a decrease in the levels of RNA1 and RNA2 at 2 weeks post‐inoculation (Fig. 7B). Recovery and silencing bioassays in tomato leaves could not be tested because of the strong necrotic response induced by the virus and the A. tumefaciens suspension (data not shown). Overall, these results suggested that the RNA2‐ORF1 protein does not provide a detectable silencing suppressor activity. We cannot exclude the possibility that RNA2‐ORF1 protein can interfere with the silencing pathway in other steps not tested by the local bioassay and/or requires further viral proteins to trigger a stronger anti‐silencing response.

RNA2‐ORF1 is required for virus upload into the phloem

To determine at what step long‐distance movement is impaired, we assessed ToANV presence by DAS‐ELISA in petioles of N. benthamiana leaves separately agroinfiltrated with binary constructs for R1+R2‐Δp21, R1+R2‐WT and R1 alone as negative control. ToANV was not detected in the petioles of leaves inoculated with R2‐Δp21, whereas abundant virus was present in the petioles of leaves inoculated with the WT clones (Fig. S4, see Supporting Information). Therefore, the RNA2‐ORF1 protein is required for steps of systemic infection occurring prior to translocation through the stems from the initially infected leaves.

To better understand possible RNA2‐ORF1 protein effects prior to virus transport in the petiole, we employed immunolocalization protocols for the detection of CPs to assess the presence of the virus in cross‐sections of leaf petioles and of secondary and tertiary veins inside leaf areas agroinfiltrated with A. tumefaciens transformed with constructs expressing R2‐Δp21 or WT virus (Fig. 8). Observations of petioles confirmed that the WT virus is detected in the phloem (Fig. 8A,B), whereas RNA2‐Δp21 is not (Fig. 8C,D). Quantitative DAS‐ELISA indicated that the level of virus accumulation was similar for R2‐Δp21 and WT virus in agroinfiltrated leaves corresponding to each petiole cross‐section (Fig. S4), ruling out the possibility that the absence of R2‐Δp21 in petioles was caused by differences in viral accumulation within the leaves.

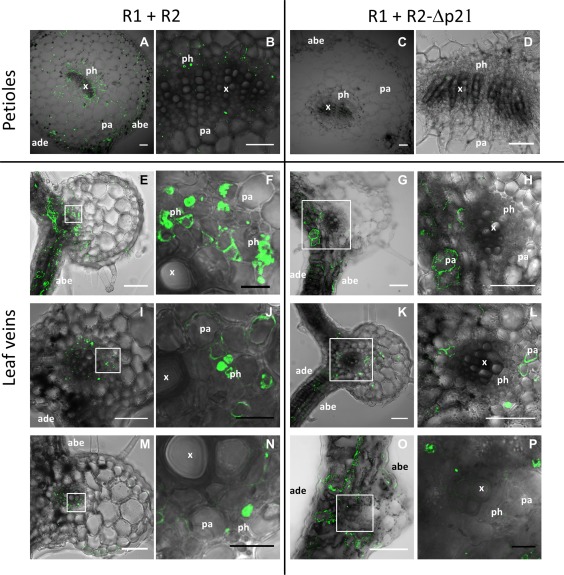

Figure 8.

Immunolocalization of tomato apex necrosis virus (ToANV) capsid protein (CP) in cross‐sections of petioles (A to D) and leaf veins (E to P) of Nicotiana benthamiana plants agroinfiltrated with constructs expressing ToANV wild‐type (WT) (R1+R2) and RNA2‐ORF1 protein mutant (R1+R2‐Δp21). We show images representative of two distinct experiments performed in four distinct agroinfiltrated areas for each construct. Ten sections were observed for at least one nervature in each agroinfiltrated area. Images are the overlays of bright field and fluorescent signals of fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugate, specific for ToANV CP detection. (F), (H), (J), (L), (N) and (P) are enlargements of the areas marked by white square boxes in (E), (G), (I), (K), (M) and (O), respectively. abe, abaxial epidermis; ade, adaxial epidermis; pa, parenchyma; ph, phloem; x, xylem. Scale bars: white, 100 μm; black, 20 μm.

The phloem of secondary and tertiary veins displayed specific fluorescence in the case of WT virus infection, indicating that ToANV was present in these areas (Fig. 8E,F,I,J,M,N). In the case of R2‐Δp21, the phloem remained negative, although parenchymatic cells around the vein showed strong positive reactions for ToANV, as indicated by specific fluorescence (Fig. 8G,H,K,L,O,P). Occasionally, we detected ToANV in some phloem parenchymatic cells inside the bundle sheath (Fig. 8L).

Discussion

Here, we took advantage of recently described infectious cDNA clones of ToANV (Ferriol et al., 2016a) to determine the role of the protein encoded by RNA2‐ORF1 in several apects of the viral infection cycle using a reverse genetics approach. Although there is still no direct evidence of accumulation of the RNA2‐ORF1‐encoded protein, we can provide evidence with regard to the functionality of the protein because: (i) conserved amino acids are present in the alignments of some homologues present in other members of the genus Torradovirus (van der Vlugt et al., 2015); (ii) two different approaches to abolish the translation of RNA2‐ORF1 in the context of the infectious clone (three stop codons engineered in the coding frame and deletion of most of the coding region) resulted in a common distinctive phenotype; and (iii) a vector based on 35S‐driven expression of the protein fused to the flag antigen in the context of the 5′‐ and 3′‐UTRs resulted in accumulation of the protein, as demonstrated by western blot analysis.

Overall, the experiments performed with the infectious cDNA clones and GFP‐expressing constructs point to the requirement of the RNA2‐ORF1 protein for systemic infection in the host plants tested here. Mechanical inoculation experiments using different RNA2‐ORF1 mutants also suggest that the RNA2‐ORF1 protein is required for efficient virus spread in the inoculated N. benthamiana and N. occidentalis leaves. Given the inefficient local spread, we cannot exclude the possibility that failure to cause systemic infection is simply a result of inefficient/insufficient local spread.

An alternative explanation for the differential local accumulation observed could be related to the efficiency in establishing infection: unfortunately, a proper local lesion host to test such a hypothesis is not available. Furthermore, we can conclude that the RNA2‐ORF1 protein is not necessary for replication or cell‐to‐cell movement and does not show silencing suppressor activity in our local bioassay. This does not rule out the possibility that the RNA2‐ORF1 protein plays a role in interfering with the antiviral silencing pathway in other steps not tested by our bioassay. We have also tried to complement the phenotype of the RNA2‐ORF1 mutants through ectopic co‐expression of two efficient silencing suppressors (p19 and TSWV NSs), but no evidence of complementation was detected (data not shown).

Our data also show that RNA2‐ORF1 protein expression is not required for RNA2‐ORF2 protein expression or polyprotein processing.

Looking more critically at our data on local ToANV movement in the inoculated leaf, we can directly compare the effect of MP deletion with the effect of RNA2‐ORF1 deletion in the context of R2‐GFP constructs, which have been shown previously to be competent for local movement: MP knockout impedes exit from the initially infected cell, demonstrating that the MP functions as a cell‐to‐cell MP, whereas R2‐Δp21‐GFP is still capable of cell‐to‐cell movement. Although, formally, RNA2‐ORF1 protein is not a cell‐to‐cell MP, we cannot exclude the possibility that it might have a further role in maintaining movement throughout the various tissues and cell types inside the agroinfiltrated area, or in the mechanically inoculated leaf: indeed, quantitative assessment of virus accumulation after mechanical inoculation shows that viruses that cannot express the RNA2‐ORF1 protein accumulate to a much lower level compared with the WT (Tables S1 and S2).

Overall, our data point to a role for the RNA2‐ORF1 protein in systemic infection and, to our knowledge, this is the first identified determinant for this aspect of the infection cycle for viruses in the family Secoviridae (Hipper et al., 2013; Sanfacon et al., 2009; Ueki and Citovsky, 2007). Furthermore, this is a rare case amongst plant viruses in which a systemic spread determinant is not provided by a CP, a silencing suppressor or a cell‐to‐cell MP (Hipper et al., 2013). Two other examples of a specific protein encoded for long‐distance movement are the newly detected ORF3a‐encoded protein in the family Luteoviridae (Smirnova et al., 2015) and the ORF3‐encoded protein of umbraviruses, but, in the latter case, a CP is absent (Taliansky et al., 2003).

In summary, the RNA2‐ORF1 protein of ToANV is required for systemic infection, but is dispensable for replication, virion formation and cell‐to‐cell movement. Our data show that the RNA2‐ORF1 protein is required for virus cycle steps prior to phloem uploading.

Experimental Procedures

Plasmid constructs

The ToANV constructs used in this study were derived from modifications to the ToANV infectious cDNA clones described previously (Ferriol et al., 2016a). Site‐directed mutagenesis was performed on the cDNA clones pJL89‐M‐R2 (a WT version of ToANV RNA2 cDNA, referred to in this article as R2‐WT) and pJL89‐M‐R2‐GFP (referred to in this article as R2‐GFP), a viral construct derived from it and described previously (Ferriol et al., 2016a) (Fig. 1). Oligonucleotides used for mutagenesis and sequencing are described in Table S3 (see Supporting Information).

To obtain mutants of RNA2‐ORF1, site‐directed mutagenesis was performed by linearizing the constructs R2‐WT and R2‐GFP by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the oligonucleotides R2‐ORF1‐sc‐F/R2‐ORF1‐sc‐R. The expression of ToANV RNA2‐ORF1 protein (GenBank accession no. KT756875) was abolished by the mutations in the codon for amino acids F3, L7 and E12, resulting in three stop codons (Fig. 1). To generate deletion mutants of the ToANV RNA2‐ORF1 protein, R2‐WT and R2‐GFP constructs were each linearized by PCR using the oligonucleotides R2‐ΔORF1‐F/R2‐ΔORF1‐R. PCRs were performed using Phusion Green Hot Start II High‐Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA). PCR products were gel excised, ligated using T4 DNA ligase (Promega, San Luis Obispo, CA, USA) and transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α competent cells. The constructs derived from R2‐WT were named R2‐p21‐sc and R2‐Δp21 (Fig. 1A), whereas the constructs derived from R2‐GFP were named R2‐p21‐sc‐GFP and R2‐Δp21‐GFP (Fig. 1B).

To generate a null mutant of ToANV MP and to obtain a control for infection limited to single plant cells, we derived two new plasmid constructs as described above using oligonucleotides DeltaMP‐760Rev and DeltaMP‐1220F and R2‐WT and R2‐GFP plasmids as templates. The resulting constructs, R2‐ΔMP and R2‐ΔMP‐GFP, had a deletion corresponding to c. 15 kDa in the MP coding region, maintaining the ToANV RNA2‐ORF2 frame (Fig. 1).

To generate a construct that only expresses the RNA2‐ORF1 protein, the plasmid R2‐WT was linearized by PCR using the oligonucleotides pJL89‐R2‐ORF1(3'UTR)‐For/pJL89‐R2‐ORF1‐Rev, as described above. The resulting plasmid, R2‐p21, contained RNA2‐ORF1 flanked by the RNA2 5′‐ and 3′‐UTRs of the virus (Fig. S1).

Because of the absence of ToANV RNA2‐ORF1 protein antibodies, we fused the 3XFLAG epitope (DYKDHDGDYKDHDIDYKDDDDK) to the RNA2‐ORF1 protein to obtain a system for checking RNA2‐ORF1 protein expression. R2‐WT plasmid was linearized by PCR using the oligonucleotides pJL89‐R2–3UTR‐FOR and pJL89‐R2‐ORF1DeS‐Rev, as described above. The HA‐Flag tag was amplified by PCR with the oligonucleotides 3XFlag‐REV and HA‐FOR using the plasmid pGWB14 as template. In‐Fusion cloning was performed using an In‐Fusion HD cloning kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA). The resulting construct, R2‐p21‐FLAG, expresses the ToANV 5′‐ and 3′‐UTRs, the RNA2‐ORF1 protein with the HA and the Flag epitope fused to the carboxy terminal of the RNA2‐ORF1 protein (Fig. S2).

Agroinoculation experiments

Each plasmid was transformed into A. tumefaciens strain C58C1 and infiltrated into N. benthamiana young leaves as described previously (Bendahmane et al., 2002; Margaria et al., 2007; Rossi et al., 2015) in combination with the construct expressing RNA1 of ToANV WT virus (pJL89‐M‐R1, referred to in this article as R1, Ferriol et al., 2016a). To standardize the experiments, the absorbance [optical density at 600 nm (OD600)] of the A. tumefaciens cultures was measured and each bacterial suspension was adjusted to a final concentration corresponding to an absorbance of 0.25, unless specific dilution experiments were performed.

Local lesion experiments

Nicotiana benthamiana plants were infiltrated with A. tumefaciens carrying ToANV WT infectious cDNA plasmid (R1+R2), or RNA2‐ORF1 mutants (R1+R2‐Δp21 and R1+R2‐p21‐sc), or RNA2‐MP mutant (R1+R2‐ΔMP), together with a construct expressing the silencing suppressor of tomato bushy stunt virus (pBIN‐p19). Crude extract from agroinfiltrated areas was inoculated onto leaves of N. occidentalis plants after filtration by a 0.45‐μm filter. Local lesions were observed at 14–21 dpi. Leaves were incubated with ethanol overnight in order to extract the chlorophyll and highlight the necrotic response.

DAS‐ELISA and western blot analysis of leaf extracts

Crude extracts of plant leaf tissue discs (diameter, 0.5 cm) were obtained by mechanical homogenization in 1 mL of phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS)–Tween buffer containing 2% (w/v) PVP (Polyvinylpyrrolidone). For DAS‐ELISA, specific ToANV‐anti‐virion antibodies (Turina et al., 2007) were coated at 2 mg/mL on Greiner high‐binding plates and the alkaline phosphatase‐conjugated ToANV‐anti‐virion antibody was diluted 1 : 1000. A preliminary assay with serial dilutions of the plant extract was carried out in order to find the concentration ranges in which absorbance was linear to virus titre: plant extracts were therefore further diluted 1 : 5 in PBS–Tween buffer in each well. Only samples with an absorbance value of at least three times the absorbance of healthy controls were considered to be positive. When the quantification of the CP was necessary, a standard dilution curve from N. benthamiana infected with ToANV‐WT was inserted for relative quantification of each sample in each ELISA plate.

Sodium dodecylsulfate‐polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS‐PAGE) of total leaf extracts, and subsequent western blot, were carried out as described previously (Rastgou et al., 2009). ToANV‐anti‐virion antibodies were diluted 1 : 2000 in blocking buffer. Secondary horseradish peroxidase antibodies (Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were used at the final dilution of 1 : 2500.

Leaf sections, immunolocalization and confocal microscopy

Agroinfiltrated leaves of N. benthamiana plants were collected and processed immediately. Class II and class III leaf veins were selected in the agroinfiltrated area. Petioles and leaf veins were cut into small pieces and fixed overnight at 4°C in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4). After washing with PBS, and embedding in 8% (w/v) low‐melting agarose, 100‐μm‐thick transverse sections were obtained with a vibrating blade microtome (Leica VT1000S, Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Sections were then processed as described in Rossi et al. (2015), using the polyclonal anti‐CP primary antibody (A405 II from the IPSP [Institute for Sustainable Plant Protection, Italy] collection). As negative controls, some sections were processed omitting either the primary or secondary antibody (not shown), or staining sections agroinfiltrated only with the R1 construct. To make sure that we could correctly recognize the morphology of cells inside the veins, a stain with toluidine blue was carried out on some sections of petiole and leaf: the phloem and the xylem are distinctively stained, the xylem appearing as empty cells with blue‐stained walls and the phloem appearing purple (data not shown). Sections were observed using a Leica TCS‐SP2 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) was excited with the 488‐nm band of an argon laser and imaged through an emission window of 500–550 nm. Images were acquired with Leica TCS‐SP2 software and then processed with ImageJ.

Virion purification and electron microscopy

A drop of the partially purified virions obtained as detailed previously (Ferriol et al., 2016a) was allowed to adsorb for 3 min on glow‐discharged, carbon and formvar‐coated grids. After rinsing with several drops of water, grids were negatively stained with 0.5% uranyl acetate and excess fluid was removed with filter paper. Observations and photographs were made using a CM 10 electron microscope (Philips, Eindhoven, the Netherlands).

RNA isolation and northern blot analysis

Nicotiana benthamiana plants were agroinfiltrated with standardized concentrations of A. tumefaciens and, when the quantitative local accumulation of viral RNA was compared in two distinct treatments, we performed our assays by agroinfiltrating a half leaf for each combination. At 5 days post‐agroinfiltration (dpa), 1 g of agroinfiltrated plant material was harvested, frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground to a fine powder. The total RNA was extracted by TRIZOL reagent and dissolved in Diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC) water to a final concentration of 1 μg/μL.

Northern blot analysis of total RNA was performed as detailed previously using a fragmented ToANV 3′‐UTR probe that hybridizes with both genomic RNAs (Ferriol et al., 2016a). Probe synthesis, hybridization and washes were carried out as detailed previously (Rossi et al., 2015).

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's website:

Fig. S1 Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of virions from tomato apex necrosis virus (ToANV) wild‐type (WT) and ToANV ORF1 and MP null mutants. Samples corresponded to agroinfiltrated leaf preparations of ToANV WT (R1+R2) (A), ToANV RNA2‐ORF1 protein stop codon mutant (R1+R2‐p21‐sc) (B), ToANV RNA2‐ORF1 protein deletion mutant (R1+R2‐Δp21) (C) and ToANV MP protein deletion mutant (R1+R2‐ΔMP) (D). Scale bar, 100 nm.

Fig. S2 Schematic representation of a modification of pJL89‐M‐R2 (R2‐WT) to express only the RNA2‐ORF1 protein (R2‐p21) and the RNA2‐ORF1 protein fused to the FLAG tag (R2‐p21‐FLAG). FLAG tag and RNA2‐ORF1 protein (p21) are indicated with red and blue boxes, respectively.

Fig. S3 RNA2‐ORF1 protein does not interfere with the anti‐viral silencing machinery in a local bioassay. (A) Western blot from leaves of Nicotiana benthamiana plants agroinfiltrated with R1+R2‐Δp21 and R1+R2‐p21‐Flag using ToANV‐CP and Flag antibodies. (B) Nicotiana benthamiana 16C plants were agroinfiltrated with the green fluorescent protein (GFP)‐containing plasmid pBIN‐GFP, the positive control p19, the wild‐type (WT) R1+R2 constructs and the mutated R1+R2‐Δp21. Each half leaf corresponds to a particular combination of binary plasmids (see labels).

Fig. S4 Double antibody sandwich‐enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (DAS‐ELISA) results for the detection of tomato apex necrosis virus (ToANV) in agroinfiltrated leaves and petioles of Nicotiana benthamiana plants. Plants were agroinfiltrated with ToANV wild‐type (WT) (R1+R2) and ToANV RNA2‐ORF1 mutant (R1+R2‐Δp21) constructs. (A) Overall mean of sample/healthy ratio of agroinfiltrated leaves shows no difference between ToANV WT and RNA2‐ORF1 mutant. Standard error of the mean (SEM) is indicated with a bar. No statistically significant differences were detected between ToANV WT and RNA2‐ORF1 mutant in the inoculated leaves (P = 0.709855). DAS‐ELISA results of detection of ToANV in agroinfiltrated leaves (B) and petioles (C). Samples were considered to be positive for ToANV infection when the absorbance of the sample/absorbance of the healthy control was >3. Positive samples are highlighted in grey and bold. Absorbance values, sample/healthy ratio, mean and SEM are indicated.

Table S1 Double antibody sandwich‐enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (DAS‐ELISA) results for the detection of tomato apex necrosis virus (ToANV) in mechanically inoculated leaves using sap from leaf areas agroinfiltrated with a number of different treatments. Samples were harvested at 6 days post‐inoculation (dpi). Virions originating from clones unable to express RNA2‐ORF1 cannot be detected in inoculated Nicotiana occidentalis leaves, but accumulate to a lower level compared with wild‐type (WT) virus in inoculated N. benthamiana leaves.

Table S2 Double antibody sandwich‐enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (DAS‐ELISA) results for the detection of tomato apex necrosis virus (ToANV) in mechanically inoculated leaves (6 days post‐inoculation, dpi) and upper non‐inoculated leaves (14 dpi) using sap from leaf areas agroinfiltrated with a number of different treatments. Virions originating from the movement protein (MP)‐deficient clone result in an undetectable level of virus infection in Nicotiana benthamiana inoculated leaves; virions originating from clones unable to express RNA2‐ORF1 result in a detectable level of virus accumulation, but absorbance is much lower relative to wild‐type (WT) virus in inoculated N. benthamiana leaves. Only wild‐type virus is detected in upper non‐inoculated leaves, indicating that the virus accumulating locally does not originate from revertants or from contamination.

Table S3 Oligonucleotides used for cloning and mutagenesis.

Acknowledgements

This research was partially funded by grant SCB11058 from the California Department of Food and Agriculture. M.T. and E.J.Z.‐M. were supported by a short‐term mobility scholarship from the Italian CNR and the Mexican government (Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología, CONACYT). We thank R. Lenzi for help with the DAS‐ELISA. We thank D. Baulcombe and G. Coaker for kindly providing plasmids pBIN‐P19 and pGWB14, respectively. We thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and editorial suggestions. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adams, I.P. , Skelton, A. , Macarthur, R. , Hodges, T. , Hinds, H. , Flint, L. , Nath, P.D. , Boonham, N. and Fox, A. (2014) Carrot yellow leaf virus is associated with carrot internal necrosis. PLoS One, 9, e109125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batuman, O. , Kuo, Y.W. , Palmieri, M. , Rojas, M.R. and Gilbertson, R.L. (2010) Tomato chocolate spot virus, a member of a new torradovirus species that causes a necrosis‐associated disease of tomato in Guatemala. Arch. Virol. 155, 857–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendahmane, A. , Farnham, G. , Moffett, P. and Baulcombe, D.C. (2002) Constitutive gain‐of‐function mutants in a nucleotide binding site‐leucine rich repeat protein encoded at the Rx locus of potato. Plant J. 32, 195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvajal‐Yepes, M. , Olaya, C. , Lozano, I. , Cuervo, M. , Castaño, M. and Cuellar, W.J. (2014) Unraveling complex viral infections in cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) from Colombia. Virus Res. 186, 76–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferriol, I. , Turina, M. , Zamora‐Macorra, E.J. and Falk, B.W. (2016a) RNA1‐independent replication and GFP expression from tomato marchitez virus isolate M cloned cDNA. Phytopathology, 106, 500–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferriol, I. , Silva Junior, D.M. , Nigg, J.C. , Zamora‐Macorra, E.J. and Falk, B.W. (2016b) Identification of the cleavage sites of the RNA2‐encoded polyproteins for two members of the genus Torradovirus by N‐terminal sequencing of the virion capsid proteins. Virology, 498, 109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoshal, B. and Sanfacon, H. (2015) Symptom recovery in virus‐infected plants: revisiting the role of RNA silencing mechanisms. Virology, 479, 167–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hipper, C. , Brault, V. , Ziegler‐Graff, V. and Revers, F. (2013) Viral and cellular factors involved in phloem transport of plant viruses. Front. Plant Sci. 4, 154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, R.C. , Duffus, J.E. and Liu, H.Y. (1984) Tomato necrotic dwarf a new type of whitefly‐transmitted virus. Phytopathology, 74, 795. [Google Scholar]

- Lecoq, H. , Verdin, E. , Tepfer, M. , Wipf‐Scheibel, C. , Millot, P. , Dafalla, G. and Desbiez, C. (2016) Characterization and occurrence of squash chlorotic leaf spot virus, a tentative new torradovirus infecting cucurbits in Sudan. Arch. Virol. 161, 1651–1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margaria, P. , Ciuffo, M. , Pacifico, D. and Turina, M. (2007) Evidence that the nonstructural protein of Tomato spotted wilt virus is the avirulence determinant in the interaction with resistant pepper carrying the Tsw gene. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 20, 547–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rastgou, M. , Habibi, M.K. , Izadpanah, K. , Masenga, V. , Milne, R.G. , Wolf, Y.I. , Koonin, E.V. and Turina, M. (2009) Molecular characterization of the plant virus genus Ourmiavirus and evidence of inter‐kingdom reassortment of viral genome segments as its possible route of origin. J. Gen. Virol. 90, 2525–2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, M. , Vallino, M. , Abba, S. , Ciuffo, M. , Balestrini, R. , Genre, A. and Turina, M. (2015) The importance of the KR‐Rich region of the coat protein of ourmia melon virus for host specificity, tissue tropism, and interference with antiviral defense. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 28, 30–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanfacon, H. , Wellink, J. , Le Gall, O. , Karasev, A. , van der Vlugt, R. and Wetzel, T. (2009) Secoviridae: a proposed family of plant viruses within the order Picornavirales that combines the families Sequiviridae and Comoviridae, the unassigned genera Cheravirus and Sadwavirus, and the proposed genus Torradovirus. Arch. Virol. 154, 899–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo, J.‐K. , Kang, M. , Kwak, H.‐R. , Kim, M.‐K. , Kim, C.‐S. , Lee, S.‐H. , Kim, J.‐S. and Choi, H.‐S. (2015) Complete genome sequence of motherwort yellow mottle virus, a novel putative member of the genus Torradovirus. Arch. Virol. 160, 587–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwach, F. , Vaistij, F.E. , Jones, L. and Baulcombe, D.C. (2005) An RNA‐dependent RNA polymerase prevents meristem invasion by Potato virus X and is required for the activity but not the production of a systemic silencing signal. Plant Physiol. 138, 1842–1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnova, E. , Firth, A.E. , Miller, W.A. , Scheidecker, D. , Brault, V. , Reinbold, C. , Rakotondrafara, A.M. , Chung, B.Y.‐W. and Ziegler‐Graff, V. (2015) Discovery of a small non‐AUG‐initiated ORF in poleroviruses and luteoviruses that is required for long‐distance movement. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1004868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taliansky, M. , Roberts, I.M. , Kalinina, N. , Ryabov, E.V. , Raj, S.K. , Robinson, D.J. and Oparka, K.J. (2003) An umbraviral protein, involved in long‐distance RNA movement, binds viral RNA and forms unique, protective ribonucleoprotein complexes. J. Virol. 77, 3031–3040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J.R. , Dasgupta, I. , Fuchs, M. , Iwanami, T. , Karasev, A.V. , Petrzik, K. , Sanfaçon, H. , Tzanetakis, I.E. , van der Vlugt, R. , Wetzel, T. , Yoshikawa, N. and ICTV Report Consortium . (2017) ICTV virus taxonomy profile: Secoviridae . J. Gen. Virol. 98, 529–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turina, M. , Ricker, M.D. , Lenzi, R. , Masenga, V. and Ciuffo, M. (2007) A severe disease of tomato in the Culiacan area (Sinaloa, Mexico) is caused by a new picorna‐like viral species. Plant Dis. 91, 932–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueki, S. , and Citovsky, V. (2007) Spread throughout the plant: systemic transport of viruses In: Viral Transport in Plants Plant Cell Monographs, vol. 7, (Waigmann E., and Heinlein M, eds), Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Verbeek, M. , Dullemans, A.M. , van den Heuvel, J.F.J.M. , Maris, P.C. and van der Vlugt, R.A.A. (2007) Identification and characterisation of tomato torrado virus, a new plant picorna‐like virus from tomato. Arch. Virol. 152, 881–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbeek, M. , Dullemans, A.M. , van den Heuvel, J.F.J.M. , Maris, P.C. and van der Vlugt, R.A.A. (2008) Tomato marchitez virus, a new plant picorna‐like virus from tomato related to tomato torrado virus. Arch. Virol. 153, 127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbeek, M. , Dullemans, A. , van den Heuvel, H. , Maris, P. and van der Vlugt, R. (2010) Tomato chocolate virus: a new plant virus infecting tomato and a proposed member of the genus Torradovirus. Arch. Virol. 155, 751–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbeek, M. , Dullemans, A.M. , van Raaij, H.M. , Verhoeven, J.T. and van der Vlugt, R.A. (2014) Lettuce necrotic leaf curl virus, a new plant virus infecting lettuce and a proposed member of the genus Torradovirus. Arch. Virol. 159, 801–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Vlugt, R.A.A. , Verbeek, M. , Dullemans, A.M. , Wintermantel, W.M. , Cuellar, W.J. , Fox, A. and Thompson, J.R. (2015) Torradoviruses. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 53, 485–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voinnet, O. , Pinto, Y.M. and Baulcombe, D.C. (1999) Suppression of gene silencing: a general strategy used by diverse DNA and RNA viruses of plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 14 147–14 152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.‐B. , Wu, Q. , Ito, T. , Cillo, F. , Li, W.‐X. , Chen, X. , Yu, J.‐L. and Ding, S.‐W. (2010) RNAi‐mediated viral immunity requires amplification of virus‐derived siRNAs in Arabidopsis thaliana . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 107, 484–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieczorek, P. and Obrepalska‐Steplowska, A. (2016a) The N‐terminal fragment of the tomato torrado virus RNA1‐encoded polyprotein induces a hypersensitive response (HR)‐like reaction in Nicotiana benthamiana . Arch. Virol. 161, 1849–1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieczorek, P. and Obrepalska‐Steplowska, A. (2016b) A single amino acid substitution in movement protein of tomato torrado virus influences ToTV infectivity in Solanum lycopersicum . Virus Res. 213, 32–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieczorek, P. , Budziszewska, M. and Obrępalska‐Stęplowska, A. (2015) Construction of infectious clones of tomato torrado virus and their delivery by agroinfiltration. Arch. Virol. 160, 517–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wintermantel, W.M. and Hladky, L.L. (2013) Genome characterization of Tomato necrotic dwarf virus, a Torradovirus from southern California. Phytopathology, 103, 160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wintermantel, W.M. , Batuman, O. , Hladky, L.L. , Vasquez, M. and Gilbertson, R.L. (2016) Emergence of two new variants of the Torradovirus Tomato necrotic dwarf virus in California. In: 5th International Symposium on Tomato Diseases, (Acta Horticulturae; conveners: Moriones E., and Fernández‐Muñoz R., eds) p. 63. Malaga, Spain.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's website:

Fig. S1 Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of virions from tomato apex necrosis virus (ToANV) wild‐type (WT) and ToANV ORF1 and MP null mutants. Samples corresponded to agroinfiltrated leaf preparations of ToANV WT (R1+R2) (A), ToANV RNA2‐ORF1 protein stop codon mutant (R1+R2‐p21‐sc) (B), ToANV RNA2‐ORF1 protein deletion mutant (R1+R2‐Δp21) (C) and ToANV MP protein deletion mutant (R1+R2‐ΔMP) (D). Scale bar, 100 nm.

Fig. S2 Schematic representation of a modification of pJL89‐M‐R2 (R2‐WT) to express only the RNA2‐ORF1 protein (R2‐p21) and the RNA2‐ORF1 protein fused to the FLAG tag (R2‐p21‐FLAG). FLAG tag and RNA2‐ORF1 protein (p21) are indicated with red and blue boxes, respectively.

Fig. S3 RNA2‐ORF1 protein does not interfere with the anti‐viral silencing machinery in a local bioassay. (A) Western blot from leaves of Nicotiana benthamiana plants agroinfiltrated with R1+R2‐Δp21 and R1+R2‐p21‐Flag using ToANV‐CP and Flag antibodies. (B) Nicotiana benthamiana 16C plants were agroinfiltrated with the green fluorescent protein (GFP)‐containing plasmid pBIN‐GFP, the positive control p19, the wild‐type (WT) R1+R2 constructs and the mutated R1+R2‐Δp21. Each half leaf corresponds to a particular combination of binary plasmids (see labels).

Fig. S4 Double antibody sandwich‐enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (DAS‐ELISA) results for the detection of tomato apex necrosis virus (ToANV) in agroinfiltrated leaves and petioles of Nicotiana benthamiana plants. Plants were agroinfiltrated with ToANV wild‐type (WT) (R1+R2) and ToANV RNA2‐ORF1 mutant (R1+R2‐Δp21) constructs. (A) Overall mean of sample/healthy ratio of agroinfiltrated leaves shows no difference between ToANV WT and RNA2‐ORF1 mutant. Standard error of the mean (SEM) is indicated with a bar. No statistically significant differences were detected between ToANV WT and RNA2‐ORF1 mutant in the inoculated leaves (P = 0.709855). DAS‐ELISA results of detection of ToANV in agroinfiltrated leaves (B) and petioles (C). Samples were considered to be positive for ToANV infection when the absorbance of the sample/absorbance of the healthy control was >3. Positive samples are highlighted in grey and bold. Absorbance values, sample/healthy ratio, mean and SEM are indicated.

Table S1 Double antibody sandwich‐enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (DAS‐ELISA) results for the detection of tomato apex necrosis virus (ToANV) in mechanically inoculated leaves using sap from leaf areas agroinfiltrated with a number of different treatments. Samples were harvested at 6 days post‐inoculation (dpi). Virions originating from clones unable to express RNA2‐ORF1 cannot be detected in inoculated Nicotiana occidentalis leaves, but accumulate to a lower level compared with wild‐type (WT) virus in inoculated N. benthamiana leaves.

Table S2 Double antibody sandwich‐enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (DAS‐ELISA) results for the detection of tomato apex necrosis virus (ToANV) in mechanically inoculated leaves (6 days post‐inoculation, dpi) and upper non‐inoculated leaves (14 dpi) using sap from leaf areas agroinfiltrated with a number of different treatments. Virions originating from the movement protein (MP)‐deficient clone result in an undetectable level of virus infection in Nicotiana benthamiana inoculated leaves; virions originating from clones unable to express RNA2‐ORF1 result in a detectable level of virus accumulation, but absorbance is much lower relative to wild‐type (WT) virus in inoculated N. benthamiana leaves. Only wild‐type virus is detected in upper non‐inoculated leaves, indicating that the virus accumulating locally does not originate from revertants or from contamination.

Table S3 Oligonucleotides used for cloning and mutagenesis.