Summary

Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris (Xcc) causes black rot, one of the most important diseases of brassica crops worldwide. The type III effector inventory plays important roles in the virulence and pathogenicity of the pathogen. However, little is known about the virulence function(s) of the putative type III effector AvrXccB in Xcc. Here, we investigated the immune suppression ability of AvrXccB and the possible underlying mechanisms. AvrXccB was demonstrated to be secreted in a type III secretion system‐dependent manner. AvrXccB tagged with green fluorescent protein is localized to the plasma membrane in Arabidopsis, and the putative N‐myristoylation motif is essential for its localization. Chemical‐induced expression of AvrXccB suppresses flg22‐triggered callose deposition and the oxidative burst, and promotes the in planta growth of Xcc and Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. The putative catalytic triad and plasma membrane localization of AvrXccB are required for its immunosuppressive activity. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that AvrXccB interacts with the Arabidopsis S‐adenosyl‐l‐methionine‐dependent methyltransferases SAM‐MT1 and SAM‐MT2. Interestingly, SAM‐MT1 is not only self‐associated, but also associated with SAM‐MT2 in vivo. SAM‐MT1 and SAM‐MT2 expression is significantly induced upon stimulation of microbe‐associated molecular patterns and bacterial infection. Collectively, these findings indicate that AvrXccB targets a putative methyltransferase complex and suppresses plant immunity.

Keywords: AvrXccB, plant immunity, S‐adenosyl‐l‐methionine‐dependent methyltransferase, type III effector, Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris

Introduction

Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris (Xcc) is the causal agent of black rot, one of the most important diseases of cruciferous vegetables (Alvarez, 2000; Williams, 1980). The pathogen infects a wide range of brassica plants, including broccoli, mustard, cabbage, cauliflower, radish, turnip and the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana (Simpson and Johnson, 1990). Many virulence factors in Xcc have been identified to contribute to successful infection and disease symptom development (Vicente and Holub, 2013). Xcc virulence is greatly attenuated when the type III secretion system is defective, indicating that the type III effectors (T3Es) are the major type of virulence factor (Sun et al., 2011).

Plants protect themselves from a plethora of microbial pathogens through the recognition of microbe‐associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) and/or secreted effectors by plasma membrane‐bound or intracellular receptors (Boller and He, 2009; Jones and Dangl, 2006). The perception often triggers a series of defence responses, including the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), induction of mitogen‐activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and pathogenesis‐related (PR) gene expression, callose deposition at the cell wall and, in some cases, a hypersensitive response (He et al., 2007; Nürnberger et al., 2004). Phytopathogenic bacteria secrete T3Es into host cells to suppress plant immunity through interference with gene expression, protein turnover, vesicle trafficking, RNA metabolism and cellular processes (Block and Alfano, 2011; Block et al., 2008; Colombatti et al., 2014; Deslandes and Rivas, 2012; Feng and Zhou, 2012; Tanaka et al., 2015). Hence, in a susceptible plant, the action of T3Es can promote bacterial multiplication and facilitate disease progression.

Many virulence targets of bacterial T3Es in host plants have been identified recently and molecular mechanisms underlying virulence functions are being uncovered (Block et al., 2008; Deslandes and Rivas, 2012; Macho, 2015; Macho and Zipfel, 2015). It is well known that the effectors from Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato (Pst) target various essential components in the defence signalling pathways, such as pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) on the plasma membrane, MAPK cascades in the cytosol and transcription factors in the nucleus (Xin and He, 2013). By contrast, relatively fewer studies have been performed to elucidate defence suppression mechanisms of T3Es in Xanthomonas spp., although many, such as XopR, XopN, XopZ and AvrBs2, have been shown to be essential for bacterial virulence (Akimoto‐Tomiyama et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2009; Li et al., 2015; Song and Yang, 2010). An elegant study has demonstrated that the Xcc effector AvrAC functions as a uridylyl transferase that uridylylates the receptor‐like cytoplasmic kinases BIK1 and RIPK at conserved phosphorylation sites, and thereby inhibits the activity of these kinases and plant immune signalling (Feng et al., 2012). The effector XopD from X. campestris pv. vesicatoria (Xcv) is a multifunctional protein and targets multiple host defence‐related proteins. It mimics plant endogenous SUMO (small ubiquitin‐like modifier) isopeptidases to hydrolyse SUMO‐conjugated proteins in vivo (Hotson et al., 2003). XopD targets and desumoylates the tomato ethylene‐responsive transcription factor SlERF4 to suppress ethylene production, which is required for anti‐Xcv immunity (Kim et al., 2013). In addition, XopD specifically interacts with the Arabidopsis transcription factor MYB30, causing suppression of MYB30 transcriptional activity and plant defence responses (Canonne et al., 2011). It has been revealed recently that XopD from Xcc targets DELLA proteins in Arabidopsis to trigger disease tolerance and increase bacterial survival (Tan et al., 2014). In addition, XopY and XopP from X. oryzae pv. oryzae have been demonstrated to suppress peptidoglycan‐ and chitin‐induced immunity, respectively, through the targeting of OsRLCK185 and OsPUB44, a rice ubiquitin E3 ligase with a unique U‐box domain (Ishikawa et al., 2014; Yamaguchi et al., 2013). Interestingly, XopL from Xcv exhibits ubiquitin E3 ligase activity and induces cell death in Nicotiana benthamiana, but disrupts defence responses in host plants (Singer et al., 2013). In addition, XopQ from Xcv suppresses effector‐triggered immunity and immunity‐associated cell death by targeting TFT4 (Teper et al., 2014).

The YopJ‐like T3Es are an important type of virulence factor widely distributed in animal bacterial pathogens, phytopathogenic bacteria and plant symbionts (Lewis et al., 2011; Orth, 2002). The YopJ‐like effectors share a highly conserved catalytic triad that includes cysteine‐histidine‐aspartate/glutamate (C‐H‐D/E) residues, a characteristic of Clan CE cysteine proteases (Orth, 2002; Orth et al., 2000). YopJ from Yersinia spp. is the archetype of this effector family and possesses multiple enzymatic activities, such as acetyltransferase and de‐ubiquitinase, to impose various pathogenic effects on host cells (Mukherjee et al., 2006; Orth et al., 2000; Zhou et al., 2005). Multiple YopJ‐like effectors in phytopathogenic bacteria have been identified and characterized recently. Both YopJ‐like effectors, P. syringae HopZ1a and Ralstonia solanacearum PopP2, function as acetyltransferases (Tasset et al., 2010). HopZ1a acetylates plant tubulin, causes a dramatic destruction of the microtubule cytoskeleton and eventually inhibits cell wall‐mediated defences (Lee et al., 2012). HopZ1a also acetylates host jasmonate ZIM‐domain (JAZ) proteins, thereby triggering the degradation of JAZs and activating jasmonic acid (JA) signalling during bacterial infection (Jiang et al., 2013). PopP2 acetylates multiple host defence‐promoting WRKY transcription factors, disabling the DNA binding and trans‐activating functions of these WRKY proteins, which are essential for defence gene expression and disease resistance (Le Roux et al., 2015). However, the acetylation of a key lysine residue within the C‐terminal WRKY domain of RRS1‐R by PopP2 can activate RPS4‐dependent immunity (Le Roux et al., 2015; Sarris et al., 2015). At least four YopJ‐like proteins, including XopJ, AvrRxv, AvrXv4 and AvrBsT, are encoded in Xcv. AvrBsT acetylates ACIP1 which is associated with microtubules. ACIP1 acetylation in planta alters its defence function (Cheong et al., 2014). XopJ targets the host cell proteasome to suppress salicylic acid‐mediated plant defence (Üstün and Börnke, 2015; Üstün et al., 2013). AvrXv4, like XopD, possesses a SUMO isopeptidase activity, and ectopic expression of AvrXv4 in plants results in a reduction in SUMO‐modified proteins (Roden et al., 2004).

AvrXccB, a YopJ‐like effector in Xcc, harbours a putative N‐myristoylation signal (Thieme et al., 2007); however, its subcellular localization in hosts has not been experimentally studied to date. AvrXccB is dispensable for full virulence of Xcc in the host Chinese radish, which may be caused by functional redundancy (Jiang et al., 2009). As a YopJ‐like effector, AvrXccB has been hypothesized to modify specific host protein(s) to suppress plant immunity, and thus promote bacterial infection. In this study, we investigated the pathogenic effects of AvrXccB. Constitutive expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP)‐tagged AvrXccB and AvrXccBG2A in Arabidopsis plants demonstrated the plasma membrane localization of the protein. Transient expression of AvrXccB in protoplasts and induced expression in transgenic plants confirmed the immune suppression activity of AvrXccB in Arabidopsis. Furthermore, we demonstrated that AvrXccB targeted putative S‐adenosyl‐l‐methionine‐dependent methyltransferase (SAM‐MT) proteins in Arabidopsis. These findings broaden our understanding of the virulence functions of T3Es in Xcc.

Results

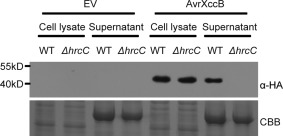

AvrXccB is secreted in a type III secretion system‐dependent manner

To confirm that AvrXccB is a bona fide T3E, we investigated whether AvrXccB is secreted in a type III secretion system‐dependent manner in Xcc. The plasmid‐borne avrXccB gene in fusion with the coding sequence of haemagglutinin (HA) was transformed into the Xcc wild‐type strain B186 and its type III secretion‐defective ΔhrcC mutant (Sun et al., 2011). The secretion of T3Es in Xcc was induced in hrp (hypersensitive response and pathogenicity)‐inducing minimal medium SMMXC (Wang et al., 2007). Western blot analysis was then performed and demonstrated that AvrXccB‐HA was present in the conditioned medium of the wild‐type strain, but not in that of the ΔhrcC mutant (Fig. 1). In contrast, the fusion protein was detected in cell lysates of the wild‐type and ΔhrcC mutant strains (Fig. 1). As negative controls, no signal was detected at all in the empty vector‐transformed Xcc cells (Fig. 1). These data indicate that AvrXccB from Xcc is indeed a T3E.

Figure 1.

AvrXccB is secreted in a type III secretion system‐dependent manner in Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris (Xcc). Western blotting using anti‐haemagglutinin (HA) antibody showed that AvrXccB‐HA was present in hrp (hypersensitive response and pathogenicity)‐inducing culture medium of the Xcc wild‐type (WT) strain B186 transformed with the avrXccB‐HA construct, but not in that of the B186ΔhrcC mutant carrying avrXccB‐HA. AvrXccB‐HA was detected in cell lysates of the avrXccB‐HA‐transformed wild‐type and ΔhrcC strains. No non‐specific cross‐reaction was detected in the EV‐transformed wild‐type and ΔhrcC strains. EV, empty vector; WT, Xcc B186; ΔhrcC, B186ΔhrcC; α‐HA, anti‐HA antibody. Lower panel shows the loading control stained with Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB).

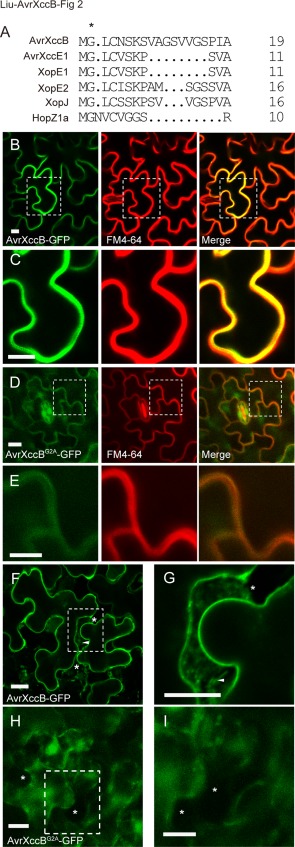

AvrXccB localizes to the plasma membrane when expressed in planta

An N‐myristoylation motif was predicted at the N‐terminus of AvrXccB through the alignment of multiple N‐myristoylated protein sequences (Fig. 2A). This suggests that a myristoyl group is covalently attached to the α‐amino group of the N‐terminal glycine (Gly) residue of the protein, which might direct AvrXccB to the plasma membrane (Farazi et al., 2001). Therefore, transgenic Arabidopsis plants constitutively expressing AvrXccB with a C‐terminal GFP tag were generated to determine the subcellular localization of the protein in host cells. Confocal laser scanning microscopy showed that bright green fluorescence was clearly confined to the periphery of epidermal cells in the transgenic plants and was not detectable in the nucleus or cytosol, indicating that AvrXccB‐GFP localizes to the plasma membrane when ectopically expressed in Arabidopsis (Fig. 2B). To confirm the subcellular localization of AvrXccB, we stained leaf tissue with the membrane‐binding fluorescent dye FM4‐64 (Ueda et al., 2001). The results showed that the green fluorescence of AvrXccB‐GFP overlapped with the red fluorescence of FM4‐64 in Arabidopsis cells (Fig. 2B,C). To investigate whether the putative myristoylation motif is essential for the plasma membrane localization of AvrXccB, we developed transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing the AvrXccBG2A‐GFP variant with the Cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter, in which the conserved Gly residue, key for myristoylation, was substituted by alanine (Ala). In avrXccBG2A‐GFP transgenic lines, green fluorescence was distributed throughout the cell, including the cytosol and nucleus. Red fluorescence stained with FM4‐64 only slightly overlapped with the green fluorescence of AvrXccBG2A‐GFP (Fig. 2D,E). Green fluorescence was also clearly observed in the plasma membrane and Hechtian strands, the attachment site between the cell wall and the plasma membrane, when the cells expressing AvrXccB‐GFP were plasmolysed (Fig. 2F,G). No Hechtian strands were visible in plasmolysed cells expressing AvrXccBG2A‐GFP (Fig. 2H,I). These observations indicate that AvrXccB localizes to the plasma membrane when it is delivered into host cells, and that the putative N‐myristoylation motif is essential for its subcellular localization.

Figure 2.

The subcellular localization of AvrXccB to the plasma membrane in transgenic Arabidopsis plants depends on its putative N‐myristoylation motif. (A) The putative N‐myristoylation motif at the N‐terminus of AvrXccB, as revealed by sequence alignment of multiple N‐myristoylated proteins, including AvrXccE1 (AAM40923.1), XopE1 (CAJ21925.1), XopE2 (CAJ23957.1), XopJ (CAJ23833.1) and HopZ1a (ABK13740.1) in Xanthomonas and Pseudomonas spp. The protein sequences were all downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) website. The second residue Gly (G), marked by an asterisk, is highly conserved and is required for protein myristoylation. (B, C) Subcellular localization of AvrXccB‐GFP. (D, E) Subcellular localization of AvrXccBG2A‐GFP with a point mutation in the second residue Gly in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. The left panels show green fluorescence, the central panels show red fluorescence after staining with the membrane‐binding lipophilic dye FM4‐64, and the right panels depict the overlay images of the two fluorescence signals. The yellow colour in overlay images indicates overlap between green and red fluorescence. Broken squares in (B, D) were enlarged to show details in (C, E). (F–I) The plasmolysed epidermal cells expressing AvrXccB‐GFP (F, G) or AvrXccBG2A‐GFP (H, I). Broken squares in (F, H) were enlarged to show details in (G, I). Asterisks indicate areas between the cell wall and plasma membrane in plasmolysed cells; Hechtian strands indicated by arrows are noticeable in (F, G), but not in (H, I). Scale bar, 10 µm. GFP, green fluorescent protein. Green and red fluorescence were observed using confocal laser scanning microscopy.

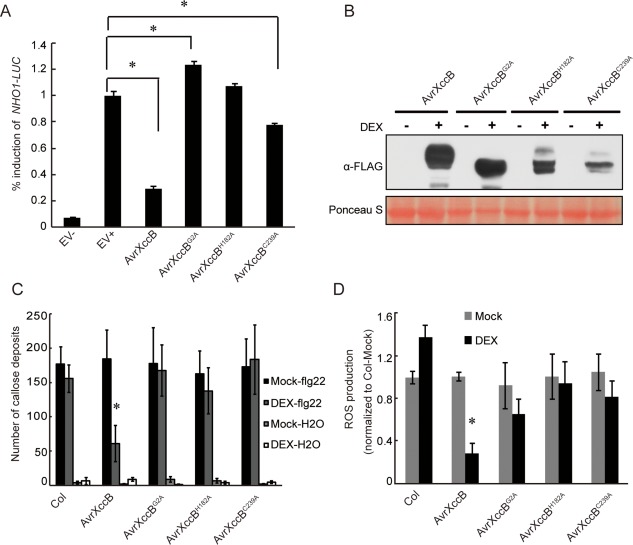

Transient expression of AvrXccB in Arabidopsis protoplasts suppresses flg22‐triggered immunity

To determine the virulence function(s) of AvrXccB, the immune suppression ability of AvrXccB was first investigated through transient expression assays in protoplasts isolated from NONHOST1 (NHO1)::LUC transgenic Arabidopsis plants (Li et al., 2005). NHO1, encoding a glycerol kinase, has been identified previously to be involved in both general and specific resistance in Arabidopsis, and is significantly induced in MAMP‐triggered immunity (Kang et al., 2003; Li et al., 2005). As shown in Fig. 3A, the expression level of luciferase was dramatically induced in the empty vector‐transfected protoplasts after flg22 treatment. However, flg22‐induced expression of luciferase was greatly suppressed after the protoplasts were transfected with the 35S::avrXccB‐FLAG construct (Fig. 3A). Luciferase expression under the NHO1 promoter was not induced by transiently expressed AvrXccB in the transfected protoplasts without flg22 stimulation (Fig. S2, see Supporting Information). These data indicate that AvrXccB inhibits flg22‐induced gene expression driven by the NHO1 promoter in Arabidopsis. As a YopJ‐like protein, AvrXccB is predicted to contain a conserved catalytic triad [cysteine‐239 (Cys239), histidine‐182 (His182) and aspartic acid‐201 (Asp201)] of cysteine protease that is required for immune suppression activity of some YopJ‐like effectors, such as HopZ1a, AvrBsT and PopP2 (Cheong et al., 2014; Jiang et al., 2013; Le Roux et al., 2015; Mukherjee et al., 2006; Sarris et al., 2015). Here, we showed that flg22‐induced luciferase expression was only partially inhibited by transiently expressed AvrXccBC239A, and was not suppressed by AvrXccBG2A and AvrXccBH182A, in transfected protoplasts, even though the expression level of these variant proteins was similar to that of the wild‐type (Figs 3A and S1, see Supporting Information). The results indicate that transiently expressed AvrXccB suppresses MAMP‐triggered immunity and that the putative catalytic triad and the N‐myristoylation site are required for its immune suppression ability in Arabidopsis protoplasts.

Figure 3.

Heterologous expression of AvrXccB suppresses microbe‐associated molecular pattern‐triggered immunity in Arabidopsis. (A) flg22‐induced expression of luciferase driven under the NHO1 promoter was dramatically inhibited by transiently expressed AvrXccB. The inhibition was attenuated in AvrXccBC239A‐transfected protoplasts and was completely lost in AvrXccBG2A‐ and AvrXccBH182A‐transfected protoplasts. Protoplasts isolated from NHO1::LUC transgenic Arabidopsis plants were transfected either with the empty vector (EV) or the indicated effector constructs, and the relative luciferase activity was measured at 12 h after flg22 treatment. EV+ represents EV‐transfected protoplasts treated with 1 μm flg22 and EV– indicates EV‐transfected protoplasts with mock treatment, which was used as a control for basal NHO1‐LUC expression. Each data point [mean ± standard error (SE)] consists of five replicates. Asterisks indicate statistically significant difference between EV+ and each indicated construct (Mann–Whitney test, P < 0.05). (B) Ectopic expression of FLAG‐tagged AvrXccB and its variants AvrXccBG2A, AvrXccBH182A and AvrXccBC239A in transgenic Arabidopsis seedlings at 24 h after dexamethasone (DEX) treatment, as detected by Western blot analyses. Top panel, the blot was probed with an anti‐FLAG antibody; bottom panel, the same blot was stained with Ponceau S to show protein loading. α‐FLAG, anti‐FLAG antibody. (C) flg22‐induced callose deposition in the wild‐type and the different transgenic Arabidopsis lines depicted in (B). Callose deposits per leaf were quantified after the seedlings had been incubated in 10 µm DEX or mock solution for 24 h, followed by 1 µm flg22 or water for another 24 h. Data are means ± SE. *Significant difference in flg22‐induced callose deposits in avrXccB transgenic plants with or without DEX treatment (Student's t‐test, P < 0.05). (D) flg22‐induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in wild‐type plants and the different transgenic Arabidopsis lines depicted in (B). ROS generation in the leaves sampled from the wild‐type and different transgenic plants with or without DEX treatment was induced by 1 µm flg22. The area under the curve for a 40‐min oxidative burst (Fig. S5, see Supporting Information) was calculated for each sample and then normalized to the mean value for the wild‐type plants with mock treatment within the same experiment. Data are means ± SE; n = 8 independent T1 lines for each construct. *Significant difference in flg22‐induced ROS generation in avrXccB transgenic plants with or without DEX treatment (Student's t‐test, P < 0.05).

Ectopic expression of AvrXccB suppresses MAMP‐triggered immunity in Arabidopsis

To further investigate AvrXccB function in the suppression of plant immunity, the transgenic Arabidopsis plants with dexamethasone (DEX)‐induced expression of AvrXccB and its variants, AvrXccBG2A, AvrXccBH182A and AvrXccBC239A, in fusion with a C‐terminal FLAG tag were generated in the Col‐0 genetic background and identified via immunoblotting (Figs 3B and S3, see Supporting Information). Callose deposition induced by flg22 was first examined in transgenic seedlings. A large number of callose deposits were formed after flg22 stimulation in transgenic Arabidopsis seedlings without DEX induction (Figs 3C and S4, see Supporting Information). By contrast, flg22‐induced callose deposition was significantly inhibited in the transgenic seedlings conditionally expressing AvrXccB‐FLAG after DEX treatment, whereas the number of callose deposits was not altered significantly in AvrXccBG2A‐, AvrXccBH182A‐ and AvrXccBC239A‐expressing transgenic seedlings (Figs 3C and S4). Similarly, the flg22‐induced generation of ROS was significantly inhibited in DEX‐sprayed avrXccB transgenic plants compared with that in mock‐treated plants (Figs 3D and S5, see Supporting Information). The ROS burst was not significantly reduced by the ectopic expression of AvrXccBG2A, AvrXccBH182A and AvrXccBC239A in the transgenic plants (Figs 3D and S5). As controls, the flg22‐triggered oxidative burst in avrXccB, avrXccBG2A, avrXccBH182A and avrXccBC239A transgenic plants was not significantly different from that in the wild‐type plants without DEX treatment (Fig. 3D). Taken together, these results indicate that AvrXccB expression significantly suppresses MAMP‐induced immunity in transgenic plants, and that the N‐myristoylation motif and the putative catalytic triad are both important for the immunosuppressive activity.

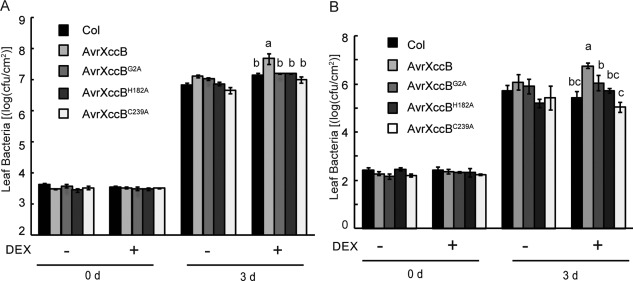

Ectopic expression of AvrXccB‐FLAG in Arabidopsis promotes bacterial infection

Disarming plant immunity through the action of T3Es facilitates the successful infection and colonization of phytopathogenic bacteria in host cells (Kenny and Valdivia, 2009). Next, we investigated whether AvrXccB is capable of promoting the infection of Xcc B186 and Pst DC3000 in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. The results showed that the induced expression of AvrXccB‐FLAG significantly increased the in planta population sizes of Xcc B186 and Pst DC3000 in transgenic plants at 3 days post‐inoculation (Fig. 4A,B). However, no significant difference in bacterial population was observed between the wild‐type and transgenic plants expressing AvrXccBG2A, AvrXccBH182A or AvrXccBC239A mutant proteins (Fig. 4A,B). In addition, the bacterial population in the wild‐type plants was similar, with or without DEX treatment (Fig. 4A,B), indicating that DEX has no effect on the proliferation of Pst DC3000 and Xcc B186. These results indicate that the ectopic expression of AvrXccB promotes bacterial infection in Arabidopsis, and that N‐myristoylation and the putative catalytic triad are essential for its infection‐promoting ability.

Figure 4.

Ectopic expression of AvrXccB in Arabidopsis promotes bacterial infection. (A) Growth of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris (Xcc) B186 in Col‐0 and the different transgenic plants depicted in Fig. 3B with or without dexamethasone (DEX) treatment. Leaves were pressure inoculated with Xcc B186 at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.0005. (B) Growth of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato (Pst) DC3000 in Col‐0 and transgenic plants. Leaves were pressure inoculated with Pst DC3000 at OD600 = 0.0002. In planta bacterial populations were assessed at 0 and 3 days post‐inoculation. cfu, colony‐forming units. Data are means ± standard error. Different letters a–c indicate statistically significant difference (Duncan's multiple range test, P < 0.05).

AvrXccB physically interacts with SAM‐MT1

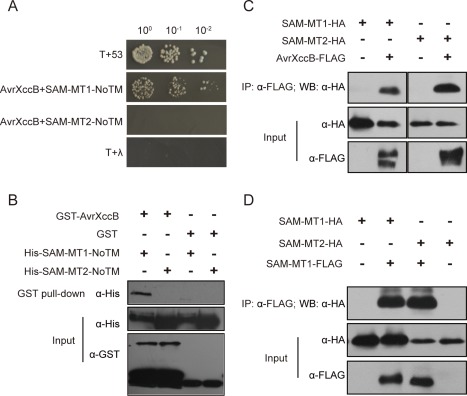

To elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying the virulence function of AvrXccB, host proteins interacting with AvrXccB were preliminarily screened via the yeast two‐hybrid system using an Arabidopsis cDNA library as prey. A putative SAM‐MT (SAM‐MT1) encoded by At3g15530 was identified to interact with AvrXccB three times (Fig. 5A). Notably, SAM‐MT1 is predicted to be a membrane‐bound protein and the identified interactor is a truncated SAM‐MT1 in its N‐terminus. Therefore, SAM‐MT1‐NoTM (lacking the first 88 residues including the predicted transmembrane domain) was used for subsequent yeast two‐hybrid assays. The AvrXccB variants AvrXccBG2A, AvrXccBH182A and AvrXccBC239A were all demonstrated to interact with SAM‐MT1‐NoTM in yeast (Fig. S6A, see Supporting Information). To identify the structural domain of SAM‐MT1 required for the interaction with AvrXccB, three truncated variants of SAM‐MT1 were generated: SAM‐MT1‐N (residues 89–172), SAM‐MT1‐M containing the methyltransferase domain (residues 116–231) and SAM‐MT1‐C (residues 173–288). The results showed that only SAM‐MT1‐C interacted with AvrXccB in yeast, indicating that the C‐terminal region of SAM‐MT1 is essential for the interaction (Fig. S6A).

Figure 5.

AvrXccB physically interacts with an S‐adenosyl‐l‐methionine‐dependent methyltransferase (SAM‐MT) complex in Arabidopsis. (A) AvrXccB interacts with Arabidopsis SAM‐MT1‐NoTM as indicated by yeast two‐hybrid assay. The pGBKT7‐avrXccB and pGADT7‐SAM‐MT1‐NoTM constructs were co‐transformed into yeast Gold strain. The growth of yeast colonies on the plates with quadruple dropout medium indicates a positive interaction. (B) In vitro pull‐down assay to detect the interaction of AvrXccB and SAM‐MT1. Glutathione S‐transferase (GST) pull‐down was conducted with GST‐binding resins after purified GST‐AvrXccB or GST had been mutually incubated with His‐SAM‐MT1‐NoTM or His‐SAM‐MT2‐NoTM. The input proteins and precipitates were subjected to immunoblotting with anti‐His and anti‐GST antibodies. α‐GST, anti‐GST antibody; α‐His, anti‐histidine antibody. (C) Co‐immunoprecipitation (Co‐IP) assays to show AvrXccB interaction with SAM‐MT1 and SAM‐MT2 in vivo. SAM‐MT1‐HA and SAM‐MT2‐HA were transiently expressed alone or together with AvrXccB‐FLAG in Arabidopsis protoplasts. (D) Co‐IP assays to show SAM‐MT1 self‐association and interaction with SAM‐MT2 in vivo. SAM‐MT1‐HA and SAM‐MT2‐HA were transiently expressed alone or together with SAM‐MT1‐FLAG in Arabidopsis protoplasts. Co‐IP was performed with anti‐FLAG M2 agarose beads and the immunoprecipitated complex was analysed with an anti‐HA antibody. α‐FLAG, anti‐FLAG antibody; α‐HA, anti‐haemagglutinin antibody; IP, immunoprecipitation; WB, Western blot.

The interaction between AvrXccB and SAM‐MT1 was subsequently verified by glutathione S‐transferase (GST) pull‐down assay. In vitro‐purified GST‐AvrXccB and GST were incubated with His‐tagged SAM‐MT1‐NoTM and precipitated using glutathione beads. Western blot analyses showed that SAM‐MT1‐NoTM was precipitated in vitro together with GST‐AvrXccB, but not with GST (Fig. 5B). These results indicate that AvrXccB interacts with SAM‐MT1 directly. Furthermore, co‐immunoprecipitation (Co‐IP) was performed to investigate the in planta interaction of AvrXccB and SAM‐MT1. AvrXccB‐FLAG and SAM‐MT1‐HA were transiently co‐expressed in Arabidopsis protoplasts. AvrXccB‐FLAG in the total protein extracts was immunoprecipitated with anti‐FLAG M2 affinity gel beads. The precipitates were subjected to immunoblotting with anti‐HA antibody. The results showed that SAM‐MT1‐HA was present in the AvrXccB‐precipitated immunocomplex, indicating that the two proteins interact with each other (Fig. 5C). Consistently, Co‐IP assays using total proteins isolated from N. benthamiana leaves co‐expressing AvrXccB‐FLAG and SAM‐MT1‐HA also demonstrated that AvrXccB interacted with SAM‐MT1 in vivo (Fig. S6B). In addition, AvrXccBG2A, AvrXccBH182A and AvrXccBC239A were all detected to interact with SAM‐MT1 in N. benthamiana by Co‐IP assays (Fig. S6C), which is consistent with the results from yeast two‐hybrid assays. These results indicate that the predicted catalytic triad and N‐myristoylation site of AvrXccB do not impose a significant effect on the interaction of AvrXccB and SAM‐MT1 in planta. Together, the results suggest that the effector AvrXccB targets SAM‐MT1 in Arabidopsis.

Interestingly, the yeast two‐hybrid and in vitro pull‐down assays did not detect AvrXccB interaction with SAM‐MT2 encoded by At5g54400, the closest homologue of SAM‐MT1 in Arabidopsis (Fig. 5A,B). However, Co‐IP experiments showed that AvrXccB was associated with SAM‐MT2 when the two proteins were co‐expressed transiently in Arabidopsis protoplasts (Fig. 5C) and in N. benthamiana leaves (Fig. S6B). Therefore, it was of interest to determine whether SAM‐MT1 interacts with SAM‐MT2 in vivo. Co‐IP assays using total proteins isolated from Arabidopsis protoplasts co‐expressing SAM‐MT1‐FLAG and SAM‐MT2‐HA demonstrated that SAM‐MT1 formed a complex with SAM‐MT2 in vivo (Fig. 5D). Furthermore, SAM‐MT1 was revealed to be self‐associated in protoplasts by Co‐IP assays (Fig. 5D). Taken together, these results indicate that AvrXccB targets a methyltransferase complex.

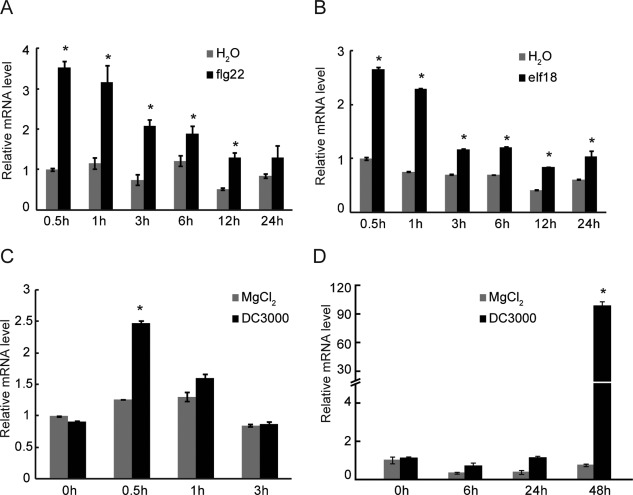

Characterization and localization of SAM‐MT1

SAM‐MT1 is predicted to encode a protein with 288 amino acid residues and a molecular weight of 32.08 kDa. To reveal its potential role in plant immunity, we investigated whether SAM‐MT1 expression was induced after MAMP treatment and pathogen challenge. Quantitative reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) showed that the abundance of SAM‐MT1 mRNA was increased rapidly after flg22 and elf18 treatment. SAM‐MT1 mRNA accumulation peaked at 30 min after MAMP treatment and decreased thereafter (Fig. 6A,B). Both SAM‐MT1 and SAM‐MT2 were significantly induced after Pst DC3000 infection. However, the expression patterns of SAM‐MT1 and SAM‐MT2 were slightly different. SAM‐MT1 expression was rapidly and moderately induced after challenge with Pst DC3000, whereas the expression of SAM‐MT2 was up‐regulated dramatically at later stages, i.e. at 48 h post‐inoculation (Fig. 6C,D).

Figure 6.

SAM‐MT1 and SAM‐MT2 are transcriptionally induced after the treatment of microbe‐associated molecular patterns and pathogen challenge in Arabidopsis. (A, B) Expression patterns of SAM‐MT1 in Arabidopsis seedlings at the indicated time points after treatment with flg22 (A) or elf18 (B). (C, D) Expression patterns of SAM‐MT1 (C) and SAM‐MT2 (D) at the indicated time points after Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato (Pst) DC3000 inoculation. Arabidopsis leaves were spray inoculated with Pst DC3000 at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.2. SAM‐MT, S‐adenosyl‐l‐methionine‐dependent methyltransferase.

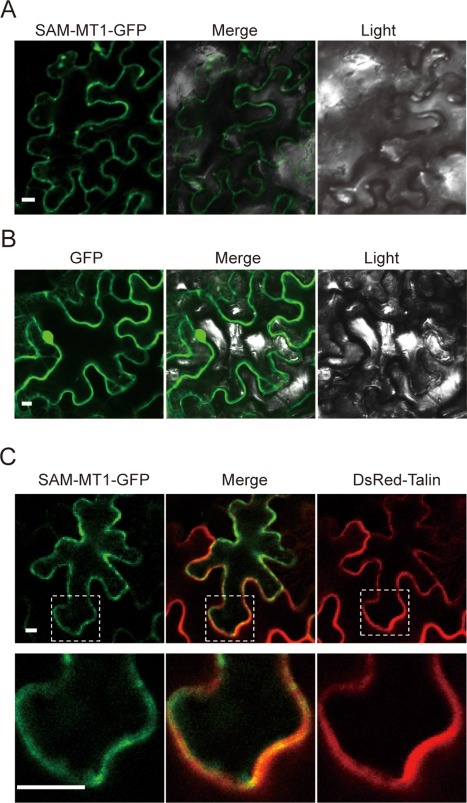

SAM‐MT1 is a putative transmembrane protein; transiently expressed SAM‐MT1‐GFP was mainly observed at the cell periphery in infiltrated N. benthamiana leaves through confocal microscopy. The fluorescence was focused in punctate structures on the plasma membrane and in the cytoplasm (Fig. 7A). As a control, GFP alone was distributed throughout the cells (Fig. 7B). Co‐expression of SAM‐MT1‐GFP and DsRed‐Talin, a membrane‐localized protein (Lim et al., 2009), in N. benthamiana leaves showed partial overlap of red and green fluorescence (Fig. 7C). These results suggest that SAM‐MT1‐GFP is localized to special punctate structures, which are associated with the plasma membrane, but also in the cytoplasm.

Figure 7.

The S‐adenosyl‐l‐methionine‐dependent methyltransferase SAM‐MT1 mainly localizes to punctate structures on the plasma membrane. (A, B) Subcellular localization of SAM‐MT1‐GFP (A) and green fluorescent protein (GFP) (B) in Nicotiana benthamiana cells. SAM‐MT1‐GFP and GFP were transiently expressed in N. benthamiana leaves. Scale bar, 10 µm. (C) SAM‐MT1‐GFP was partially co‐localized with DsRed‐Talin, a membrane‐localized protein, in N. benthamiana leaves. Bottom panels, broken squares in the top panels were enlarged to show detail. Scale bar, 10 µm. The images were photographed at 48 h after agroinfiltration.

Discussion

Genetic analysis has revealed that gene deletion of avrXccB has no significant effect on the virulence of Xcc (Jiang et al., 2009). In this study, we investigated the virulence function of AvrXccB using transgenic and biochemical approaches. Heterologous expression of the protein suppressed MAMP‐triggered immunity and promoted bacterial infection in Arabidopsis. A series of biochemical assays revealed that AvrXccB interacted with putative Arabidopsis SAM‐MTs: SAM‐MT1 and SAM‐MT2.

Through bioinformatic analysis, AvrXccB was predicted to be a T3E (Jiang et al., 2009). Here, we experimentally confirmed that AvrXccB secretion was induced in minimal medium and was dependent on the functional type III secretion system (Fig. 1). These are typical characteristics of T3Es. It is well known that many phytopathogenic bacteria suppress host immunity through the action of secreted effectors (Asai and Shirasu, 2015). For instance, XopJ from Xcv suppresses callose deposition elicited by a type III secretion system‐defective mutant of Pst DC3000 (Bartetzko et al., 2009). The P. syringae effector HopF2 also inhibits stomatal immunity and flg22‐induced ROS production in Arabidopsis (Hurley et al., 2014). The X. oryzae pv. oryzae effector XopR attenuates early defence responses induced by the type III secretion system‐defective hrcC mutant, and thus enhances the proliferation of the hrcC mutant of Xcc in Arabidopsis (Akimoto‐Tomiyama et al., 2012). Here, we have demonstrated that AvrXccB suppresses multiple layers of plant immunity and promotes in planta bacterial multiplication in Arabidopsis. First, transient expression of AvrXccB in Arabidopsis protoplasts dramatically inhibited NHO1 promoter‐driven expression of luciferase upon flg22 stimulation (Fig. 3A). Second, ectopic expression of AvrXccB in transgenic Arabidopsis plants suppressed flg22‐induced callose deposition and ROS production (Fig. 3C,D). Lastly, but more importantly, the ectopic expression of AvrXccB caused a small but significant increase in the in planta population of Xcc B186 and Pst DC3000 in Arabidopsis (Fig. 4A,B). Collectively, our data provide strong evidence for a role of AvrXccB in the inhibition of plant immunity.

It has been predicted that AvrXccB is targeted to the plasma membrane through a myristoyl group (Thieme et al., 2007). Membrane localization of AvrXccB in host cells was confirmed through the expression of AvrXccB‐GFP in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. The replacement of the second residue Gly in AvrXccB with Ala caused mistargeting of the protein to the cytosol and nucleus (Fig. 2B–I). Multiple Pseudomonas and Xanthomonas effectors, such as XopE1, XopE2, XopJ, AvrRpm1, AvrB, AvrPto and HopF2 are targeted to the host cell membrane by protein N‐myristoylation. The myristoylation of these effectors is required for avirulence and virulence functions (Nimchuk et al., 2000; Robert‐Seilaniantz et al., 2006; Shan et al., 2000; Thieme et al., 2007). Xanthomonas XopJ and HopZ4, a YopJ family protein from P. syringae, inhibit proteasome activity through interaction with the proteasomal subunit RPT6. The inhibitory effect is dependent on the plasma membrane localization and conserved catalytic triad of these effector proteins (Üstün and Börnke, 2015; Üstün et al., 2014). Therefore, we investigated the effect of the N‐myristoylation motif on various facets of AvrXccB function. Experimental data demonstrated that the AvrXccBG2A mutant was compromised in the ability to inhibit MAMP‐induced immunity, including the up‐regulation of defence‐related genes in Arabidopsis protoplasts, callose deposition and ROS production in transgenic plants (Fig. 3). The point mutation also significantly attenuated the ability of the effector to promote bacterial growth in the transgenic Arabidopsis plants (Fig. 4). The band shift in the AvrXccBG2A mutant might be caused by structural changes or altered post‐translational modification as a result of mis‐localization (Fig. 3B). Collectively, the conserved Gly2 residue of AvrXccB is essential for its membrane localization and function in immune suppression.

AvrXccB is a putative YopJ‐like cysteine protease/acetyltransferase family effector and harbours a conserved catalytic triad. YopJ variants with point mutations in the catalytic domain were unable to inhibit the MAPK and NFκB pathways (Mukherjee et al., 2006; Orth et al., 2000). Mutations in the conserved catalytic core of other YopJ‐like effectors, including AvrBsT in Xcv or Xcc, XopJ in Xcv, HopZ1a in P. syringae and Pop2 in R. solanacearum, all abolished their avirulence and virulence function (Cheong et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2012; Tasset et al., 2010; Üstün and Börnke, 2015; Üstün et al., 2013). AvrXccBH182A and AvrXccBC239A, with point mutations in the catalytic triad, were compromised in their inhibition of the NHO1‐driven expression of luciferase in the transfected protoplasts after flg22 treatment. Furthermore, AvrXccBH182A and AvrXccBC239A were deprived of their abilities to suppress flg22‐induced callose deposition and ROS production, and to promote the growth of Xcc B186 and Pst DC3000 in transgenic Arabidopsis plants (Figs 3 and 4). These results indicate that the conserved catalytic triad is crucial for the virulence function of AvrXccB.

It has been reported that the YopJ‐like effectors disable the plant immune system by targeting multiple host proteins and through various biochemical strategies. For instance, some effectors, such as AvrBsT and HopZ1a, function as acetyltransferases, which acetylate multiple Arabidopsis defence‐related proteins (Cheong et al., 2014; Jiang et al., 2013). Some effectors serve as proteases. XopJ and HopZ4 specifically degrade the proteasomal subunit RPT6 (Üstün and Börnke, 2015; Üstün et al., 2014). Other YopJ‐like effectors, such as AvrXv4, possess SUMO isopeptidase activity and cause a reduction in SUMO‐modified proteins (Roden et al., 2004). Here, we identified the host targets of AvrXccB in order to gain an insight into the molecular mechanisms underlying AvrXccB virulence function. Preliminary results from yeast two‐hybrid screening showed that AvrXccB interacted with SAM‐MT1 in Arabidopsis through the C‐terminal domain of SAM‐MT1. The interaction of AvrXccB and SAM‐MT1 was subsequently confirmed through multiple approaches. In vitro pull‐down assay showed that the two proteins interacted with each other directly (Fig. 5B). The in vivo interaction of the two proteins was substantiated by Co‐IP assays using transiently expressed proteins in Arabidopsis protoplasts and in N. benthamiana (Figs 5C and S6B). Point mutations in AvrXccBG2A, AvrXccBH182A and AvrXccBC239A had no significant effect on the interaction with SAM‐MT1, although these mutants were compromised in their virulence function (Figs 3, 4, and S6A, C). Consistently, it has been reported previously that the catalytic mutant HopZ1a (C216A), similar to the wild‐type protein, also interacts with GmJAZ1 (Jiang et al., 2013).

SAM‐MT2 is the closest homologue of SAM‐MT1 in Arabidopsis and shares 78% protein sequence identity with SAM‐MT1. The interaction of AvrXccB and SAM‐MT2 was therefore investigated. It was found that AvrXccB also interacted with SAM‐MT2 in vivo (Figs 5C and S6B), but not in vitro or in yeast (Fig. 5A,B). These results suggest that some unknown host factor is most likely required for the in vivo interaction of AvrXccB with SAM‐MT2. Subsequent experiments demonstrated that SAM‐MT1 was self‐associated and also interacted with SAM‐MT2 in vivo (Fig. 5D). We speculate that AvrXccB is targeted to a methyltransferase complex formed by SAM‐MT1 and SAM‐MT2. As many T3Es target multiple host proteins, it remains to be determined whether AvrXccB interacts with other host proteins.

In Arabidopsis, SAM‐MTs belong to a protein superfamily (Arabidopsis Genome Initiative, 2000). It has been reported that some SAM‐MTs are involved in plant immunity. AtHOL1 has been demonstrated to have SAM‐MT activity. hol1 seedlings are more susceptible to infection by P. syringae pv. maculicola (Nagatoshi and Nakamura, 2009). Isoflavone‐O‐methyltransferase (IOMT) is also a SAM‐MT transferring a methyl group from SAM to isoflavones, yielding the methyl ether derivatives. IOMT‐overexpressing alfalfa plants display enhanced resistance to Phoma medicaginis (He and Dixon, 2000). In this study, the potential role of SAM‐MT1 in Arabidopsis immunity was also suggested by the fact that SAM‐MT1 expression is induced rapidly after flg22 or elf18 treatment (Fig. 6A,B). However, SAM‐MT1 function needs to be investigated further using genetic and biochemical analyses. Unfortunately, attempts to identify the null mutant allele of SAM‐MT1 failed. Interestingly, SAM‐MT1‐GFP is mainly localized to punctate structures on the plasma membrane (Fig. 7). The localization pattern is reminiscent of ACIP1, the target of AvrBsT, which is associated with microtubules and required for plant immunity (Cheong et al., 2014). Therefore, in the future, it would be interesting to investigate whether SAM‐MT1 is associated with microtubules.

In summary, AvrXccB suppresses plant immunity and promotes bacterial infection in Arabidopsis. The interaction of AvrXccB with the SAM‐MT1 complex implies a link between SAM‐MT1/2 and AvrXccB virulence function. The up‐regulation of SAM‐MT1/2 expression after MAMP treatment and pathogen challenge suggests a potential role of this type of putative methyltransferase in plant immunity.

Experimental Procedures

Plant materials and bacterial strains

The wild‐type (ecotype Col‐0) and transgenic A. thaliana plants were typically grown at 22 °C under a 12‐h light and 12‐h dark cycle for the collection of seeds and under a 10‐h light and 14‐h dark cycle for bacterial inoculation assays. The Escherichia coli strain DH5α was cultured at 37 °C in Luria broth (LB) medium. Agrobacterium tumefaciens strains GV3101 and EHA105, used for floral dipping and transient expression, respectively, were grown at 28 °C in LB medium. Pst DC3000 and Xcc B186 were cultured at 28 °C in King's B and nutrient yeast glycerol (NYG) media, respectively.

Effector constructs

The open reading frame (ORF) of avrXccB was amplified from genomic DNA of Xcc B186 using Pfu DNA polymerase with the primer set AvrXccB‐XhoI‐F and AvrXccB‐Csp45I‐R (Table S1, see Supporting Information). The resulting PCR product was digested with XhoI and Csp45I, and ligated into pUC19‐35S‐FLAG‐RBS (Li et al., 2005). The gene constructs with individual point mutations of avrXccB, including avrXccBG2A, avrXccBH182A and avrXccBC239A, were generated through site‐directed mutagenesis, as described previously (Sun et al., 2006), with the primers given in Table S1. Subsequently, avrXccB or its variants, together with FLAG‐coding sequences, were released by XhoI and SpeI, and re‐ligated into the binary vector pTA7001 with a DEX‐inducible promoter (Aoyama and Chua, 1997). For subcellular localization of AvrXccB, avrXccB was cloned into pENTR‐D/TOPO (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and recombined using LR clonase (Invitrogen) into the destination vector pGWB5, which allows the expression of the target protein in frame fused with GFP at its C‐terminus under the Cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter (Nakagawa et al., 2007). For secretion assay, the full‐length avrXccB gene was amplified with the primer set AvrXccB‐EcoRI‐F and AvrXccB‐HA‐HindIII‐R using Pfu DNA polymerase. The PCR product was cloned into pEASY‐Blunt II (TransGen, Beijing, China), and subcloned into the wide‐host‐range plasmid pVSP61 (Loper and Lindow, 1987) after digestion by EcoRI and HindIII to generate the pVSP61‐avrXccB‐HA construct. All constructs were subjected to confirmation via sequencing.

AvrXccB secretion assay

The pVSP61‐avrXccB‐HA construct was conjugated into Xcc B186 and its type III secretion‐defective ΔhrcC mutant (Sun et al., 2011) using triparental mating. Secretion assay was performed as described previously (Sun et al., 2011). The secretion of T3Es in Xcc was induced by the culture of bacteria in SMMXC medium (Wang et al., 2007). The proteins were precipitated from the conditioned medium and cell pellets by 10% trichloroacetic acid and then separated by sodium dodecylsulfate‐polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS‐PAGE). The proteins were electrophoretically transferred onto poly(vinylidene difluoride) (PVDF) membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) and detected using anti‐HA‐horseradish peroxidase (anti‐HA‐HRP) antibody (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland).

Generation of transgenic Arabidopsis plants

The avrXccB constructs, including pGWB5‐avrXccB, pGWB5‐avrXccBG2A, pTA7001‐avrXccB and its variants avrXccBG2A, avrXccBH182A and avrXccBC239A, were transformed into Ag. tumefaciens by the freeze–thaw method (Holsters et al., 1978). Agrobacterium‐mediated plant transformation was performed through floral dipping (Clough and Bent, 1998). Transgenic seedlings were screened on half‐strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium plates with 25 μg/mL hygromycin. The expression of AvrXccB, AvrXccBG2A, AvrXccBH182A and AvrXccBC239A was induced by spraying with 30 μm DEX and confirmed by Western blot analyses.

Subcellular localization of AvrXccB and SAM‐MT1

In planta subcellular localization of AvrXccB‐GFP and AvrXccBG2A‐GFP was investigated using transgenic plants constitutively expressing these fusion proteins. Green fluorescence was observed in the epidermal cells of transgenic Arabidopsis plants using confocal laser scanning microscopy (Nikon Ti2000, Chiyoda, Tokyo, Japan) with an excitation wavelength of 488 nm. For FM4‐64 staining, detached Arabidopsis leaves were submerged in 8.2 μm of FM4‐64 solution (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) for 15 min. Leaves were rinsed with distilled water and observed immediately. For plasmolysis, Arabidopsis leaves were submerged in 0.5 m NaCl for 15 min. Subcellular localization of SAM‐MT1 was examined through transient expression in N. benthamiana leaves. Agrobacterium tumefaciens EHA105 carrying pGWB5‐SAM‐MT1‐GFP (OD600 = 0.5) was infiltrated alone or together with the DsRed‐Talin‐containing Ag. tumefaciens strain into N. benthamiana leaves after being incubated in suspension buffer [10 mm 2‐(N‐morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES), pH 5.6, 10 mm MgCl2 and 150 μm acetosyringone] for 2 h. Green or red fluorescence was observed in infiltrated leaves using confocal microscopy at 2 days after agro‐infiltration. pGD‐p19 was co‐infiltrated to suppress gene silencing.

Callose deposition assay

The transgenic Arabidopsis seedlings were incubated with 10 μm DEX or mock solution for 24 h, followed by flg22 treatment (1 μm) for 24 h. Callose deposition induced by flg22 in these seedlings was stained and visualized as described previously (Gómez‐Gómez et al., 1999).

Oxidative burst assay

Approximately 5‐week‐old wild‐type and transgenic Arabidopsis plants conditionally expressing AvrXccB and its variants AvrXccBG2A, AvrXccBH182A and AvrXccBC239A, driven by the DEX‐inducible promoter, were used for oxidative burst assay (Sun et al., 2012). Leaf discs were punched at 24 h after plants had been sprayed with 30 µm DEX, and then floated on 50 μL of sterile water in a 96‐well plate overnight. The leaf discs were transferred into 100 μL of elicitor solution containing 1 μm flg22, 20 mm luminol and 1 μg HRP (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). Luminescence was scored immediately using a Tecan Infinite F200 luminometer (Tecan, Mannedorf, Switzerland) for 40 min.

Protoplast isolation and transient expression

Protoplasts were isolated from the leaves of approximately 5‐week‐old wild‐type and NHO1‐LUC transgenic Arabidopsis plants following the protocol described previously (http://genetics.mgh.harvard.edu/sheenweb). The isolated protoplasts were transfected with different avrXccB gene constructs or the empty vector via polyethylene glycol (PEG)‐mediated transformation. After washing with W5 buffer (154 mm NaCl, 125 mm CaCl2, 5 mm KCl and 2 mm MES‐KOH, pH 5.7), the transfected protoplasts were incubated with 1 µm flg22 in W5 buffer for 12 h. Luminescence was measured using a Tecan Infinite F200 luminometer immediately after the addition of 50 µm luciferin to the transfected protoplasts.

Protein extraction and Western blot analysis

Protein extraction and Western blotting were performed as described previously with minor modifications (Li et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2012). Briefly, N. benthamiana leaves or Arabidopsis seedlings were ground in centrifuge tubes with small stainless steel balls using a milling apparatus (Retsch, Haan, Germany). Total proteins were extracted from the ground powder using extraction buffer consisting of 50 mm tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (Tris)‐HCl, pH 7.4, 500 mm NaCl, 5 mm ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 10% glycerol, 0.1% Triton X‐100, 20 mm dithiothreitol (DTT) and 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). Total proteins in Arabidopsis protoplasts were extracted by the addition of a modified extraction buffer [50 mm Tris‐HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X‐100, 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma)]. The isolated proteins were subjected to separation in SDS‐PAGE gels, and then electrophoretically transferred onto PVDF membrane. The proteins on the membrane were detected with either anti‐HA (Roche) or anti‐FLAG (Sigma) antibodies, followed by a chemiluminescence eECL Western Blot Kit (CWBio, Beijing, China).

Plant inoculation and bacterial growth assays

Wild‐type and transgenic Arabidopsis plants (approximately 5 weeks old) were sprayed with 30 μm DEX or mock solution and used for bacterial inoculation at 24 h after spraying. Overnight cultured bacterial cells were collected and resuspended in 10 mm MgCl2 to OD600 = 0.0002 (for Pst DC3000) and OD600 = 0.0005 (for Xcc B186). The bacteria were pressure infiltrated into DEX‐ or mock‐treated leaves using plastic needleless syringes. The inoculated plants were kept under plastic covers to maintain high humidity for 1 day, and then grown further under normal growth conditions. In planta bacterial population sizes were evaluated as described previously (Sun et al., 2011).

Yeast two‐hybrid screening

Screening of the Arabidopsis complementary DNA (cDNA) library was performed using the MatchmakerTM GAL4 two‐hybrid system 3 (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the yeast strain AH109, pre‐transformed with pGBKT7‐avrXccB, was transformed with the pGADT7 plasmids isolated from the Arabidopsis cDNA library. A total of approximately four million transformants were screened for AvrXccB interactors. For one‐to‐one confirmation assays, the constructed pGBKT7 and pGADT7 plasmids were pairwise co‐transformed into the yeast strain Gold using a Frozen‐EZ Yeast Transformation II Kit™ following the manufacturer's instructions (ZYMO Research, Irvine, CA, USA). The transformants were grown on synthetic defined (SD) double dropout [DDO, SD/–tryptophan (Trp)–leucine (Leu)] medium and then streaked onto fresh quadruple dropout [QDO, SD/–Trp–Leu–His–adenine (Ade)] medium to check protein interaction.

Co‐IP assay

AvrXccB‐FLAG and its variants AvrXccBH182A, AvrXccBC239A and AvrXccBG2A were transiently expressed with SAM‐MT1‐HA or SAM‐MT2‐HA in N. benthamiana and in Arabidopsis protoplasts, respectively. Total proteins were isolated from the inoculated leaves or transfected protoplasts. For Co‐IP, protein extracts (1 mL) were incubated with 40 µL anti‐FLAG M2 affinity beads (Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 4 °C for 4 h with rotation. The beads were then thoroughly washed with phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS). The bead‐bound proteins were resolved with SDS‐PAGE sample buffer (50 mm Tris‐HCl, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 6% glycerol, 0.1 m DTT, 0.01% bromophenol blue) and then subjected to immunoblotting.

Pull‐down assays

GST‐AvrXccB was expressed in E. coli XL1‐Blue cells using pGEX‐TEV. His‐SAM‐MT1‐NoTM and His‐SAM‐MT2‐NoTM were expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells using pET32b. GST‐tagged and His6‐tagged proteins were purified using GST·BindTM Resin (Novagen, Billerica, MA, USA) and Ni‐NTA His Bind® Resin (Novagen), respectively. GST‐AvrXccB (10 µg) was mixed with 10 µg of His‐SAM‐MT1‐NoTM or His‐SAM‐MT2‐NoTM. The mixture was incubated with 40 µL of pre‐equilibrated GST·BindTM Resin at 4 °C for 4 h with rotation. The beads were then thoroughly washed with PBS. Proteins bound to the beads were separated by SDS‐PAGE, and were then analysed by immunoblot analysis after boiling for 5 min in 100 µL of sample buffer. The anti‐GST (ZSGB‐Bio, Beijing, China) and anti‐His (TransGen) antibodies were used to detect GST‐AvrXccB and His‐tagged proteins, respectively.

RNA isolation and quantitative real‐time RT‐PCR

Arabidopsis seedlings (10 days old) were treated with 1 µm flg22 or mock solution. Alternatively, Arabidopsis plants (approximately 5 weeks old) were spray inoculated with Pst DC3000 at OD600 = 0.2 or mock solution (10 mm MgCl2). Total RNA was isolated from the seedlings collected at different time periods using an Ultrapure RNA isolation kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (CWBio). cDNA was synthesized by SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) using total RNA as template. Gene expression was quantified through quantitative RT‐PCR with SYBR® premix Ex TaqTM (CWBio) using an ABI PRISM® 7500 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The expression level of AtUBQ5 was detected and used as an internal reference with the primers given in Table S1.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's website:

Fig. S1 Western blot analysis to detect the transient expression of AvrXccB‐FLAG and its variants AvrXccBG2A‐, AvrXccBH182A‐ and AvrXccBC239A‐FLAG in Arabidopsis protoplasts. Total proteins isolated from the protoplasts transfected with different effector constructs were subjected to immunoblotting with an anti‐FLAG antibody. α‐FLAG, anti‐FLAG antibody; EV, empty vector.

Fig. S2 Luciferase expression under the NHO1 promoter is not induced by transiently expressed AvrXccB‐FLAG in Arabidopsis protoplasts without flg22 stimulation. (A) Luciferase expression under the NHO1 promoter in the avrXccB‐FLAG‐transfected protoplasts without flg22 stimulation. EV, empty vector; –, without flg22; +, with flg22. (B) Transient expression of AvrXccB‐FLAG in the avrXccB‐transfected protoplasts. Total proteins were extracted from the empty vector (EV)‐ or avrXccB‐transfected protoplasts, and were then subjected to immunoblotting. Top panel, the blot was probed with an anti‐FLAG antibody; bottom panel, the same blot was stained with Ponceau S to show protein loading. α‐FLAG, anti‐FLAG antibody.

Fig. S3 Ectopic expression of FLAG‐tagged AvrXccB in transgenic Arabidopsis seedlings. Total proteins were isolated from wild‐type Col and transgenic seedlings collected at 24 h after dexamethasone (DEX) or mock treatment, and detected by Western blot analyses. Top panel, the blot was probed with an anti‐FLAG antibody; bottom panel, the same blot was stained with Ponceau S to show protein loading. –, without DEX treatment; +, with DEX treatment; α‐FLAG, anti‐FLAG antibody.

Fig. S4 Callose deposition induced by flg22 treatment in the wild‐type and different transgenic Arabidopsis seedlings conditionally expressing AvrXccB‐FLAG and its variants AvrXccBG2A‐, AvrXccBH182A‐ or AvrXccBC239A‐FLAG. All seedlings were pretreated with 10 µm dexamethasone (DEX) or mock solution for 24 h, followed by 1 µm flg22 or water for another 24 h. Callose deposition was stained with aniline blue and observed by fluorescence microscopy under UV light. Representative images are shown.

Fig. S5 flg22‐induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in wild‐type plants and different transgenic Arabidopsis lines conditionally expressing AvrXccB‐FLAG and its variants AvrXccBG2A‐, AvrXccBH182A‐ or AvrXccBC239A‐FLAG. The oxidative burst was recorded in leaf samples for 40 min immediately after the wild‐type and different transgenic plants pretreated with dexamethasone (DEX) (A) or mock solution (B) had been stimulated by flg22. Data are means ± standard error; n = 8 independent T1 lines for each construct.

Fig. S6 AvrXccB interacts with the S‐adenosyl‐l‐methionine‐dependent methyltransferases SAM‐MT1 and SAM‐MT2 in vivo. (A) Yeast two‐hybrid assays showed that point mutations in the putative N‐myristoylation motif and conserved catalytic triad did not affect AvrXccB interaction with SAM‐MT1, and that the C‐terminal domain of SAM‐MT1 was essential for the interaction. (B) Co‐immunoprecipitation (Co‐IP) assays showed the interaction of AvrXccB with SAM‐MT1 and SAM‐MT2 in vivo. SAM‐MT1‐HA and SAM‐MT2‐HA were transiently expressed alone or together with AvrXccB‐FLAG in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. (C) AvrXccB and its variants AvrXccBG2A, AvrXccBH182A and AvrXccBC239A all interacted with SAM‐MT1, as indicated by Co‐IP assays. SAM‐MT1‐HA was transiently expressed alone or together with AvrXccB‐FLAG and its variants AvrXccBG2A‐FLAG, AvrXccBH182A‐FLAG and AvrXccBC239A‐FLAG in N. benthamiana leaves. Co‐IP was performed with anti‐FLAG M2 agarose beads and the immunoprecipitated complex was analysed with an anti‐HA antibody. α‐FLAG, anti‐FLAG antibody; α‐HA, anti‐haemagglutinin antibody; IP, immunoprecipitation; WB, Western blot.

Table S1 Primers for effector constructs and quantitative reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction experiments.

Acknowledgements

We thank Shuhua Yang and Dawei Li at China Agricultural University (Beijing, China) for the Arabidopsis cDNA library and DsRed‐Talin construct, and Jianmin Zhou at the Institute of Genetics and Development Biology (Beijing, China) for the plasmids and plant materials. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 31272007), the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (2012AA100703), the Special Fund for Agro‐Scientific Research in the Public Interest of China (201303015) and the 111 project B13006 to W.S.

References

- Akimoto‐Tomiyama, C. , Furutani, A. , Tsuge, S. , Washington, E.J. , Nishizawa, Y. , Minami, E. and Ochiai, H. (2012) XopR, a type III effector secreted by Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae, suppresses microbe‐associated molecular pattern‐triggered immunity in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol . Plant–Microbe Interact. 25, 505–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, A.M. (2000) Black rot of crucifers In: Mechanisms of Resistance to Plant Diseases (Slusarenko A., Fraser R.S.S. and van Loon L.C., eds), pp. 21–52. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Aoyama, T. and Chua, N.H. (1997) A glucocorticoid‐mediated transcriptional induction system in transgenic plants. Plant J. 11, 605–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arabidopsis Genome Initiative (2000) Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana . Nature, 408, 796–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asai, S. and Shirasu, K. (2015) Plant cells under siege: plant immune system versus pathogen effectors. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 28, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartetzko, V. , Sonnewald, S. , Vogel, F. , Hartner, K. , Stadler, R. , Hammes, U.Z. and Börnke, F. (2009) The Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria type III effector protein XopJ inhibits protein secretion: evidence for interference with cell wall‐associated defense responses. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 22, 655–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block, A. and Alfano, J.R. (2011) Plant targets for Pseudomonas syringae type III effectors: virulence targets or guarded decoys? Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 14, 39–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block, A. , Li, G. , Fu, Z.Q. and Alfano, J.R. (2008) Phytopathogen type III effector weaponry and their plant targets. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 11, 396–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boller, T. and He, S.Y. (2009) Innate immunity in plants: an arms race between pattern recognition receptors in plants and effectors in microbial pathogens. Science, 324, 742–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canonne, J. , Marino, D. , Jauneau, A. , Pouzet, C. , Brière, C. , Roby, D. and Rivas, S. (2011) The Xanthomonas type III effector XopD targets the Arabidopsis transcription factor MYB30 to suppress plant defense. Plant Cell, 23, 3498–3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Cheong, M.S. , Kirik, A. , Kim, J. , Frame, K. , Kirik, V. and Mudgett, M.B. (2014) AvrBsT acetylates Arabidopsis ACIP1, a protein that associates with microtubules and is required for immunity. PLoS Pathog. 10, e1003952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough, S.J. and Bent, A.F. (1998) Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana . Plant J. 16, 735–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombatti, F. , Gonzalez, D.H. and Welchen, E. (2014) Plant mitochondria under pathogen attack: a sigh of relief or a last breath? Mitochondrion, 19, 238–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deslandes, L. and Rivas, S. (2012) Catch me if you can: bacterial effectors and plant targets. Trends Plant Sci. 17, 644–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farazi, T.A. , Waksman, G. and Gordon, J.I. (2001) The biology and enzymology of protein N‐myristoylation. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 39 501–39 504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng, F. and Zhou, J. (2012) Plant–bacterial pathogen interactions mediated by type III effectors. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 15, 469–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng, F. , Yang, F. , Rong, W. , Wu, X. , Zhang, J. , Chen, S. , He, C. and Zhou, J. (2012) A Xanthomonas uridine 5'‐monophosphate transferase inhibits plant immune kinases. Nature, 485, 114–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez‐Gómez, L. , Felix, G. and Boller, T. (1999) A single locus determines sensitivity to bacterial flagellin in Arabidopsis thaliana . Plant J. 18, 277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, P. , Shan, L. and Sheen, J. (2007) Elicitation and suppression of microbe‐associated molecular pattern‐triggered immunity in plant–microbe interactions. Cell Microbiol. 9, 1385–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, X. and Dixon, R.A. (2000) Genetic manipulation of isoflavone 7‐O‐methyltransferase enhances biosynthesis of 4'‐O‐methylated isoflavonoid phytoalexins and disease resistance in alfalfa. Plant Cell, 12, 1689–1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holsters, M. , De Waele, D. , Depicker, A. , Messens, E. , Van Montagu, M. and Schell, J. (1978) Transfection and transformation of Agrobacterium tumefaciens . Mol. Gen. Genet. 163, 181–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotson, A. , Chosed, R. , Shu, H. , Orth, K. and Mudgett, M.B. (2003) Xanthomonas type III effector XopD targets SUMO‐conjugated proteins in planta . Mol. Microbiol. 50, 377–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley, B. , Lee, D. , Mott, A. , Wilton, M. , Liu, J. , Liu, Y.C. , Angers, S. , Coaker, G. , Guttman, D.S. and Desveaux, D. (2014) The Pseudomonas syringae type III effector HopF2 suppresses Arabidopsis stomatal immunity. PLoS One, 9, e114921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa, K. , Yamaguchi, K. , Sakamoto, K. , Yoshimura, S. , Inoue, K. , Tsuge, S. , Kojima, C. and Kawasaki, T. (2014) Bacterial effector modulation of host E3 ligase activity suppresses PAMP‐triggered immunity in rice. Nat. Commun. 5, 5430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S. , Yao, J. , Ma, K. , Zhou, H. , Song, J. , He, S.Y. and Ma, W. (2013) Bacterial effector activates jasmonate signaling by directly targeting JAZ transcriptional repressors. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, W. , Jiang, B.L. , Xu, R.Q. , Huang, J.D. , Wei, H.Y. , Jiang, G.F. , Cen, W.J. , Liu, J. , Ge, Y.Y. , Li, G.H. , Su, L.L. , Hang, X.H. , Tang, D.J. , Lu, G.T. , Feng, J.X. , He, Y.Q. and Tang, J.L. (2009) Identification of six type III effector genes with the PIP box in Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris and five of them contribute individually to full pathogenicity. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 22, 1401–1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J.D. and Dangl, J.L. (2006) The plant immune system. Nature, 444, 323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang, L. , Li, J. , Zhao, T. , Xiao, F. , Tang, X. , Thilmony, R. , He, S. and Zhou, J.M. (2003) Interplay of the Arabidopsis nonhost resistance gene NHO1 with bacterial virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 100, 3519–3524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, B. and Valdivia, R. (2009) Host–microbe interactions: bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 12, 1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.G. , Li, X. , Roden, J.A. , Taylor, K.W. , Aakre, C.D. , Su, B. , Lalonde, S. , Kirik, A. , Chen, Y. , Baranage, G. , McLane, H. , Martin, G.B. and Mudgett, M.B. (2009) Xanthomonas T3S effector XopN suppresses PAMP‐triggered immunity and interacts with a tomato atypical receptor‐like kinase and TFT1. Plant Cell, 21, 1305–1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. , Stork, W. and Mudgett, M.B. (2013) Xanthomonas type III effector XopD desumoylates tomato transcription factor SlERF4 to suppress ethylene responses and promote pathogen growth. Cell Host Microbe, 13, 143–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, A.H. , Hurley, B. , Felsensteiner, C. , Yea, C. , Ckurshumova, W. , Bartetzko, V. , Wang, P.W. , Quach, V. , Lewis, J.D. , Liu, Y.C. , Bornke, F. , Angers, S. , Wilde, A. , Guttman, D.S. and Desveaux, D. (2012) A bacterial acetyltransferase destroys plant microtubule networks and blocks secretion. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Roux, C. , Huet, G. , Jauneau, A. , Camborde, L. , Trémousaygue, D. , Kraut, A. , Zhou, B. , Levaillant, M. , Adachi, H. , Yoshioka, H. , Raffaele, S. , Berthomé, R. , Couté, Y. , Parker, J.E. and Deslandes, L. (2015) A receptor decoy converts pathogen disabling of transcription factors into immunity. Cell, 161, 1074–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, J.D. , Lee, A. , Ma, W. , Zhou, H. , Guttman, D.S. and Desveaux, D. (2011) The YopJ superfamily in plant‐associated bacteria. Mol. Plant Pathol. 12, 928–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. , Wang, Y. , Wang, S. , Fang, A. , Wang, J. , Liu, L. , Zhang, K. , Mao, Y. and Sun, W. (2015) The type III effector AvrBs2 in Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzicola suppresses rice immunity and promotes disease development. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 28, 869–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. , Lin, H. , Zhang, W. , Zou, Y. , Zhang, J. , Tang, X. and Zhou, J. (2005) Flagellin induces innate immunity in nonhost interactions that is suppressed by Pseudomonas syringae effectors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 102, 12 990–12 995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim, H. , Bragg, J.N. , Ganesan, U. , Ruzin, S. , Schichnes, D. , Lee, M.Y. , Vaira, A.M. , Ryu, K.H. , Hammond, J. and Jackson, A.O. (2009) Subcellular localization of the barley stripe mosaic virus triple gene block proteins. J. Virol. 83, 9432–9448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loper, J.E. and Lindow, S.E. (1987) Lack of evidence for the in situ fluorescent pigment production by Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae on bean leaf surfaces. Phytopathology, 77, 1449–1454. [Google Scholar]

- Macho, A.P. (2015) Subversion of plant cellular functions by bacterial type‐III effectors: beyond suppression of immunity. New Phytol. 210, 51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macho, A.P. and Zipfel, C. (2015) Targeting of plant pattern recognition receptor‐triggered immunity by bacterial type‐III secretion system effectors. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 23, 14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, S. , Keitany, G. , Li, Y. , Wang, Y. , Ball, H.L. , Goldsmith, E.J. and Orth, K. (2006) Yersinia YopJ acetylates and inhibits kinase activation by blocking phosphorylation. Science, 312, 1211–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagatoshi, Y. and Nakamura, T. (2009) Arabidopsis HARMLESS TO OZONE LAYER protein methylates a glucosinolate breakdown product and functions in resistance to Pseudomonas syringae pv. maculicola . J. Biol. Chem. 284, 19 301–19 309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa, T. , Kurose, T. , Hino, T. , Tanaka, K. , Kawamukai, M. , Niwa, Y. , Toyooka, K. , Matsuoka, K. , Jinbo, T. and Kimura, T. (2007) Development of series of gateway binary vectors, pGWBs, for realizing efficient construction of fusion genes for plant transformation. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 104, 34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimchuk, Z. , Marois, E. , Kjemtrup, S. , Leister, R.T. , Katagiri, F. and Dangl, J.L. (2000) Eukaryotic fatty acylation drives plasma membrane targeting and enhances function of several type III effector proteins from Pseudomonas syringae . Cell, 101, 353–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nürnberger, T. , Brunner, F. , Kemmerling, B. and Piater, L. (2004) Innate immunity in plants and animals: striking similarities and obvious differences. Immunol. Rev. 198, 249–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth, K. (2002) Function of the Yersinia effector YopJ. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 5, 38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth, K. , Xu, Z. , Mudgett, M.B. , Bao, Z.Q. , Palmer, L.E. , Bliska, J.B. , Mangel, W.F. , Staskawicz, B. and Dixon, J.E. (2000) Disruption of signaling by Yersinia effector YopJ, a ubiquitin‐like protein protease. Science, 290, 1594–1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert‐Seilaniantz, A. , Shan, L. , Zhou, J. and Tang, X. (2006) The Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 type III effector HopF2 has a putative myristoylation site required for its avirulence and virulence functions. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 19, 130–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roden, J. , Eardley, L. , Hotson, A. , Cao, Y. and Mudgett, M.B. (2004) Characterization of the Xanthomonas AvrXv4 effector, a SUMO protease translocated into plant cells. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 17, 633–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarris, P.F. , Duxbury, Z. , Huh, S. , Ma, Y. , Segonzac, C. , Sklenar, J. , Derbyshire, P. , Cevik, V. , Rallapalli, G. , Saucet, S.B. , Wirthmueller, L. , Menke, F.L. , Sohn, K.H. and Jones, J.D. (2015) A plant immune receptor detects pathogen effectors that target WRKY transcription factors. Cell, 161, 1089–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan, L. , Thara, V.K. , Martin, G.B. , Zhou, J. and Tang, X. (2000) The Pseudomonas AvrPto protein is differentially recognized by tomato and tobacco and is localized to the plant plasma membrane. Plant Cell, 12, 2323–2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, R.B. and Johnson, L.J. (1990) Arabidopsis thaliana as a host for Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris . Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 3, 233–237. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, A.U. , Schulze, S. , Skarina, T. , Xu, X. , Cui, H. , Eschen‐Lippold, L. , Egler, M. , Srikumar, T. , Raught, B. , Lee, J. , Scheel, D. , Savchenko, A. and Bonas, U. (2013) A pathogen type III effector with a novel E3 ubiquitin ligase architecture. PLoS Pathog. 9, 430–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song, C. and Yang, B. (2010) Mutagenesis of 18 type III effectors reveals virulence function of XopZPXO99 in Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae . Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 23, 893–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W. , Dunning, F.M. , Pfund, C. , Weingarten, R. and Bent, A.F. (2006) Within‐species flagellin polymorphism in Xanthomonas campestris pv campestris and its impact on elicitation of Arabidopsis FLAGELLIN SENSING2‐dependent defenses. Plant Cell, 18, 764–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W. , Liu, L. and Bent, A.F. (2011) Type III secretion‐dependent host defence elicitation and type III secretion‐independent growth within leaves by Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris . Mol. Plant Pathol. 12, 731–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W. , Cao, Y. , Labby, K.J. , Bittel, P. , Boller, T. and Bent, A.F. (2012) Probing the Arabidopsis flagellin receptor: FLS2‐FLS2 association and the contributions of specific domains to signaling function. Plant Cell, 24, 1096–1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan, L. , Rong, W. , Luo, H. , Chen, Y. and He, C. (2014) The Xanthomonas campestris effector protein XopDXcc8004 triggers plant disease tolerance by targeting DELLA proteins. New Phytol. 204, 595–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, S. , Han, X. and Kahmann, R. (2015) Microbial effectors target multiple steps in the salicylic acid production and signaling pathway. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasset, C. , Bernoux, M. , Jauneau, A. , Pouzet, C. , Brière, C. , Kieffer‐Jacquinod, S. , Rivas, S. , Marco, Y. and Deslandes, L. (2010) Autoacetylation of the Ralstonia solanacearum effector PopP2 targets a lysine residue essential for RRS1‐R‐mediated immunity in Arabidopsis. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1001202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teper, D. , Salomon, D. , Sunitha, S. , Kim, J.G. , Mudgett, M.B. and Sessa, G. (2014) Xanthomonas euvesicatoria type III effector XopQ interacts with tomato and pepper 14‐3‐3 isoforms to suppress effector‐triggered immunity. Plant J. 77, 309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thieme, F. , Szczesny, R. , Urban, A. , Kirchner, O. , Hause, G. and Bonas, U. (2007) New type III effectors from Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria trigger plant reactions dependent on a conserved N‐myristoylation motif. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 20, 1250–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda, T. , Yamaguchi, M. , Uchimiya, H. and Nakano, A. (2001) Ara6, a plant‐unique novel type Rab GTPase, functions in the endocytic pathway of Arabidopsis thaliana . EMBO J. 20, 4730–4741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Üstün, S. and Börnke, F. (2015) The Xanthomonas campestris type III effector XopJ proteolytically degrades proteasome subunit RPT6. Plant Physiol. 168, 107–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Üstün, S. , Bartetzko, V. and Börnke, F. (2013) The Xanthomonas campestris type III effector XopJ targets the host cell proteasome to suppress salicylic‐acid mediated plant defence. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Üstün, S. , König, P. , Guttman, D.S. and Börnke, F. (2014) HopZ4 from Pseudomonas syringae, a member of the HopZ type III effector family from the YopJ superfamily, inhibits the proteasome in plants. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 27, 611–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicente, J.G. and Holub, E.B. (2013) Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris (cause of black rot of crucifers) in the genomic era is still a worldwide threat to brassica crops. Mol. Plant Pathol. 14, 2–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L. , Tang, X. and He, C. (2007) The bifunctional effector AvrXccC of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris requires plasma membrane‐anchoring for host recognition. Mol. Plant Pathol. 8, 491–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, P.H. (1980) Black rot: a continuing threat to world crucifers. Plant Dis. 64, 736–742. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, X. and He, S.Y. (2013) Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000: a model pathogen for probing disease susceptibility and hormone signaling in plants. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 51, 473–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, K. , Yamada, K. , Ishikawa, K. , Yoshimura, S. , Hayashi, N. , Uchihashi, K. , Ishihama, N. , Kishi‐Kaboshi, M. , Takahashi, A. , Tsuge, S. , Ochiai, H. , Tada, Y. , Shimamoto, K. , Yoshioka, H. and Kawasaki, T. (2013) A receptor‐like cytoplasmic kinase targeted by a plant pathogen effector is directly phosphorylated by the chitin receptor and mediates rice immunity. Cell Host Microbe, 13, 347–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H. , Monack, D.M. , Kayagaki, N. , Wertz, I. , Yin, J. , Wolf, B. and Dixit, V.M. (2005) Yersinia virulence factor YopJ acts as a deubiquitinase to inhibit NF‐κB activation. J. Exp. Med. 202, 1327–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's website:

Fig. S1 Western blot analysis to detect the transient expression of AvrXccB‐FLAG and its variants AvrXccBG2A‐, AvrXccBH182A‐ and AvrXccBC239A‐FLAG in Arabidopsis protoplasts. Total proteins isolated from the protoplasts transfected with different effector constructs were subjected to immunoblotting with an anti‐FLAG antibody. α‐FLAG, anti‐FLAG antibody; EV, empty vector.

Fig. S2 Luciferase expression under the NHO1 promoter is not induced by transiently expressed AvrXccB‐FLAG in Arabidopsis protoplasts without flg22 stimulation. (A) Luciferase expression under the NHO1 promoter in the avrXccB‐FLAG‐transfected protoplasts without flg22 stimulation. EV, empty vector; –, without flg22; +, with flg22. (B) Transient expression of AvrXccB‐FLAG in the avrXccB‐transfected protoplasts. Total proteins were extracted from the empty vector (EV)‐ or avrXccB‐transfected protoplasts, and were then subjected to immunoblotting. Top panel, the blot was probed with an anti‐FLAG antibody; bottom panel, the same blot was stained with Ponceau S to show protein loading. α‐FLAG, anti‐FLAG antibody.

Fig. S3 Ectopic expression of FLAG‐tagged AvrXccB in transgenic Arabidopsis seedlings. Total proteins were isolated from wild‐type Col and transgenic seedlings collected at 24 h after dexamethasone (DEX) or mock treatment, and detected by Western blot analyses. Top panel, the blot was probed with an anti‐FLAG antibody; bottom panel, the same blot was stained with Ponceau S to show protein loading. –, without DEX treatment; +, with DEX treatment; α‐FLAG, anti‐FLAG antibody.