Summary

The oomycete Phytophthora capsici is a plant pathogen responsible for important losses to vegetable production worldwide. Its asexual reproduction plays an important role in the rapid propagation and spread of the disease in the field. A global proteomics study was conducted to compare two key asexual life stages of P. capsici, i.e. the mycelium and cysts, to identify stage‐specific biochemical processes. A total of 1200 proteins was identified using qualitative and quantitative proteomics. The transcript abundance of some of the enriched proteins was also analysed by quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction. Seventy‐three proteins exhibited different levels of abundance between the mycelium and cysts. The proteins enriched in the mycelium are mainly associated with glycolysis, the tricarboxylic acid (or citric acid) cycle and the pentose phosphate pathway, providing the energy required for the biosynthesis of cellular building blocks and hyphal growth. In contrast, the proteins that are predominant in cysts are essentially involved in fatty acid degradation, suggesting that the early infection stage of the pathogen relies primarily on fatty acid degradation for energy production. The data provide a better understanding of P. capsici biology and suggest potential metabolic targets at the two different developmental stages for disease control.

Keywords: cysts, mass spectrometry, mycelium, Phytophthora capsici, plant‐pathogenic oomycete, quantitative proteomics

Introduction

The filamentous oomycete Phytophthora capsici is a virulent hemibiotrophic pathogen that causes crown, root and fruit rot in a range of solanaceous and legume hosts, as well as in most cucurbits (Gevens et al., 2008; Gobena et al., 2012; Kamoun et al., 2015; Leonian, 1922). It is ubiquitous and characterized by an explosive epidemiology (Hausbeck and Lamour, 2004; Kamoun et al., 2015; Lamour et al., 2012a, 2012b).

During warm (25–28°C) and wet conditions, P. capsici produces large numbers of asexual spores and rapidly spreads through crops, causing significant losses (Granke et al., 2009). The propagation and survival of P. capsici depend on both rapid asexual reproduction and sexual outcrossing (Lamour and Kamoun, 2009; Quesada‐Ocampo et al., 2011; Risiamo et al., 1991). The sexual life cycle requires interaction between two compatible mating types, designated A1 and A2 (Erwin and Ribeiro, 1996), which results in the production of oospores that can persist in the soil for years, thereby providing a primary source of inoculum in successive crops (Bowers et al., 1990). However, oospores have an indeterminate period of dormancy, generally more than 8 weeks, before germination (Satour and Butler, 1968). This limits their role in the rapid propagation and spread of the disease within an established crop, which is therefore predominantly achieved through asexual propagation. Under favourable environmental conditions, P. capsici produces large numbers of sporangia on the surface of infected tissues, which are easily dislodged by rainfall and irrigation. When immersed in water, the sporangia quickly release 20–40 motile biflagellate zoospores, which swim in search of suitable hosts (Bernhardt and Grogan, 1982). On contact, the spores encyst and adhere to the plant surface, initiating infection. Hyphae are then produced and grow and ramify throughout the host tissue. On maturity, the vegetative mycelium produces new sporangia, which provide the means for dispersal and the establishment of a new infection cycle. Given the importance of the asexual phase in the epidemiology of P. capsici, it is expected that a greater knowledge of the types of proteins associated with the corresponding developmental stages will provide further insight into the growth and infection processes of the pathogen.

Previous proteomics studies of oomycetes have applied both global and more specific approaches using mass spectrometry (MS). For example, a recent study profiled the secretome and extracellular proteome of Phytophthora infestans (Meijer et al., 2014), whereas Ebstrup et al. (2005) identified differentially regulated proteins from the germinating cysts and appressoria of the same pathogen using two‐dimensional gel electrophoresis (2‐DE) and MS. Similar comparative analyses have been made between the hyphae and germinating cysts of Phytophthora pisi and Phytophthora sojae (Hosseini et al., 2015), whereas another study compared the total proteome of P. sojae and Phytophthora ramorum (Savidor et al., 2008). High‐throughput proteomics approaches produce a wealth of data that provide useful information about the basic biology of pathogenic microorganisms. This, in turn, allows the identification of new potential targets of microbial growth inhibitors for the control of devastating diseases.

Here, we have performed a comparative analysis of the proteomes of the mycelium and cysts of P. capsici. The proteins identified were functionally classified, which provides the basis for future research on these developmental stages in P. capsici and closely related species. Many of the proteins enriched in either the mycelium or cysts were found to contribute specific functions in these two life stages. The data provide a better understanding of the metabolic pathways underlying the mycelial and cyst developmental stages of P. capsici and point to potential targets of anti‐oomycete compounds at each of these stages.

Results

Profiling the proteomes of P. capsici mycelium and cysts

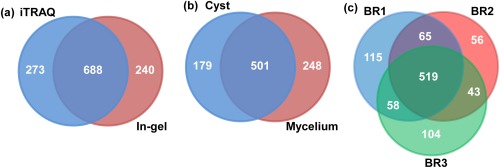

Twelve hundred unique proteins were identified from isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantification (iTRAQ) and gel‐based proteomics analyses of P. capsici mycelium and cysts (Table S1, see Supporting Information). Of these, 688 were common to the lists generated independently by iTRAQ and in‐gel approaches (Fig. 1a). The combination of both experimental approaches increased significantly the total number of unique proteins identified. The in‐gel approach led to the identification of 928 unique proteins, 749 from the mycelium and 680 from the cysts, 501 of which were common to both samples (Fig. 1b). Qualitative analysis of the samples used for the iTRAQ experiments allowed the identification of 757, 683 and 724 unique proteins from the three biological replicates BR1, BR2 and BR3, respectively (Fig. 1c). In addition to the 519 proteins that were common to all three biological replicates, each replicate contained proteins that were not identified in the other two samples (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1.

Qualitative proteomics analysis of the mycelium and cysts of Phytophthora capsici. Venn diagram representing the total number of unique proteins identified from the iTRAQ and in‐gel experiments (a), in‐gel experiments from cysts and mycelium samples (b) and iTRAQ analysis of three biological replicates (BRs) (c).

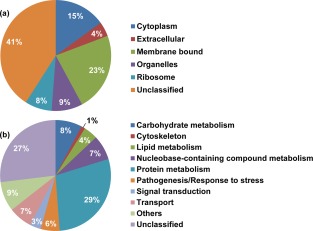

Bioinformatics analysis of all identified proteins (1200) indicated that 69 (6%) contained a signal peptide and were therefore likely to be secreted or membrane proteins (Table S1). Gene ontology analysis led to the categorization of the 1200 proteins into six different groups based on their predicted cellular location (Fig. 2a). A higher proportion of proteins were predicted to be membrane bound (23%) and cytoplasmic (15%). Proteins predicted to be associated with intracellular organelles and ribosomes represented 9% and 8% of the total proteins identified, respectively. A smaller proportion of proteins (4%) were predicted to be extracellular. However, the majority of the proteins (41%) could not be assigned any specific cellular location. The 1200 proteins were also classified into 10 functional groups corresponding to different biological processes (Fig. 2b). The largest groups corresponded to proteins involved in protein metabolism (29%) and proteins with an unknown function (27%). The next largest groups contained proteins involved in carbohydrate metabolism (8%), metabolic processes requiring nucleobase‐containing compounds (7%), transport (7%), pathogenesis/response to stress (6%), lipid metabolism (4%), signal transduction (3%) and other miscellaneous processes (9%). Only a very small proportion of the proteins identified (1%) were predicted to be associated with cytoskeleton organization.

Figure 2.

Predicted cellular location (a) and functional annotation (b) of the proteins identified in the global proteomes of the mycelium and cysts of Phytophthora capsici.

Differential abundance of proteins in the mycelium and cysts

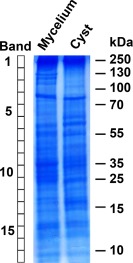

The variation in the intensity of several of the Coomassie blue‐stained sodium dodecylsulfate‐polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS‐PAGE) bands indicated that proteins of different apparent molecular masses were particularly more abundant in either the mycelium or cyst samples (Fig. 3). These results were substantiated by iTRAQ quantitative analysis, which revealed that 73 proteins had significantly different levels of abundance, with 39 being enriched in the mycelium (Table 1) and 34 in the cysts (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Sodium dodecylsulfate‐polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS‐PAGE) analysis of the proteins extracted from the mycelium and cysts of Phytophthora capsici. Twenty micrograms of protein were loaded in each lane and stained with Coomassie blue. Each lane of the gel was cut into 17 bands, as shown on the left side of the figure, prior to proteomics analysis.

Table 1.

List of the Phytophthora capsici proteins with greater abundance in the mycelium than in the cysts.

| P. infestans acc. no. | P. capsici acc. no. | Description* | Score | E value | Hit identity (%) | CC | Functional category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PITG_15476 | Phyca11|505882 | Malate dehydrogenase | 1488 | 0.00E+00 | 88.99 | Cyt | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| PITG_13116 | Phyca11|506671 | Triose‐phosphate isomerase | 1206 | 4.39E‐158 | 93.20 | Cyt | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| PITG_09402 | Phyca11|510172 | Phosphoglycerate kinase | 1081 | 4.82E‐141 | 88.84 | Cyt | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| PITG_05636 | Phyca11|505958 | Transaldolase | 1540 | 0.00E+00 | 92.51 | Cyt | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| PITG_03698 | Phyca11|503568 | Enolase | 2235 | 0.00E+00 | 95.59 | Cyt | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| PITG_18720 | Phyca11|504894 | ATP‐citrate synthase | 5245 | 0.00E+00 | 92.54 | Cyt | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| PITG_10032 | Phyca11|507227 | 6‐Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase | 2500 | 0.00E+00 | 98.36 | Mem | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| PITG_01752 | Phyca11|506857 | Transketolase | 3428 | 0.00E+00 | 93.94 | Mem | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| PITG_00146 | Phyca11|509625 | Glucose‐6‐phosphate 1‐dehydrogenase | 2421 | 0.00E+00 | 93.69 | Unc | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| PITG_03724 | Phyca11|503545 | Phosphate di‐kinase | 4235 | 0.00E+00 | 90.89 | Unc | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| PITG_02785 | Phyca11|507726 | Fructose‐bisphosphate aldolase | 1804 | 0.00E+00 | 94.97 | Unc | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| PITG_02786 | Phyca11|507726 | Fructose‐bisphosphate aldolase | 1815 | 0.00E+00 | 95.25 | Unc | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| PITG_01938 | Phyca11|504523 | Glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase | 1466 | 0.00E+00 | 93.05 | Unc | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| PITG_07960 | Phyca11|575859 | α‐Tubulin | 2084 | 0.00E+00 | 93.06 | Cyt | Cytoskeleton |

| PITG_11069 | Phyca11|509055 | Villin‐like protein | 4817 | 0.00E+00 | 65.78 | Mem | Cytoskeleton |

| PITG_01407 | Phyca11|506353 | d‐Isomer‐specific 2‐hydroxyacid dehydrogenase | 1487 | 0.00E+00 | 86.49 | Mem | Nucleobase‐containing compound metabolic process |

| PITG_01408 | Phyca11|506353 | d‐Isomer‐specific 2‐hydroxyacid dehydrogenase | 1619 | 0.00E+00 | 93.99 | Mem | Nucleobase‐containing compound metabolic process |

| PITG_03552 | Phyca11|538675 | Histone H4 | 410 | 1.93E‐50 | 100.00 | Org | Nucleobase‐containing compound metabolic process |

| PITG_00921 | Phyca11|568375 | Phospholipase D, Pi‐PLD‐like‐1 | 2689 | 0.00E+00 | 94.54 | Unc | Nucleobase‐containing compound metabolic process |

| PITG_15553 | Phyca11|509385 | Inorganic pyrophosphatase | 2856 | 0.00E+00 | 95.15 | Cyt | Other |

| PITG_00488 | Phyca11|530474 | Acyl‐coenzyme A‐binding protein | 289 | 1.44E‐31 | 84.06 | Unc | Other |

| PITG_02594 | Phyca11|17928 | Glutamate decarboxylase | 1751 | 0.00E+00 | 93.24 | Cyt | Pathogenesis/response to stress |

| PITG_12562 | Phyca11|529073 | Elicitin‐like protein | 513 | 2.59E‐61 | 83.05 | Ext | Pathogenesis/response to stress |

| PITG_18316 | Phyca11|503727 | Phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase | 1952 | 0.00E+00 | 92.36 | Mem | Pathogenesis/response to stress |

| PITG_12158 | Phyca11|509308 | Annexin (annexin) family | 1377 | 0.00E+00 | 86.82 | Unc | Pathogenesis/response to stress |

| PITG_11329 | Phyca11|107407 | Annexin (annexin) family | 1742 | 2.98E‐112 | 75.32 | Mem | Pathogenesis/response to stress |

| PITG_05861 | Phyca11|511613 | Metalloprotease family m20 m25 m40 | 1843 | 0.00E+00 | 92.86 | Unc | Protein metabolism |

| PITG_01072 | Phyca11|509774 | 5‐Methyl‐tetrahydropteroyl‐triglutamate‐homocysteine methyltransferase | 3640 | 0.00E+00 | 94.20 | Unc | Protein metabolism |

| PITG_04611 | Phyca11|504366 | Protein kinase | 1714 | 0.00E+00 | 95.13 | Unc | Protein metabolism |

| PITG_11719 | Phyca11|503391 | 4‐Hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase | 1939 | 0.00E+00 | 92.66 | Unc | Protein metabolism |

| PITG_02586 | Phyca11|116914 | Cytoplasmic dynein 1 heavy chain 1 | 1095 | 2.77E‐133 | 92.80 | Unc | Signal transduction |

| PITG_19250 | Phyca11|505536 | 12‐Oxophytodienoate reductase | 1651 | 0.00E+00 | 83.98 | Unc | Signal transduction |

| PITG_14721 | Phyca11|506608 | 12‐Oxophytodienoate reductase | 1694 | 0.00E+00 | 85.87 | Unc | Signal transduction |

| PITG_17921 | Phyca11|510618 | P‐type ATPase (P‐atpase) superfamily | 4957 | 0.00E+00 | 95.26 | Mem | Transport |

| PITG_00693 | Phyca11|535506 | Plasma membrane H+‐ATPase | 3333 | 0.00E+00 | 96.14 | Mem | Transport |

| PITG_03719 | Phyca11|503558 | Voltage‐gated potassium channel subunit β | 1779 | 0.00E+00 | 96.56 | Unc | Transport |

| PITG_02909 | Phyca11|507657 | Carbohydrate‐binding protein | 1782 | 0.00E+00 | 81.77 | Mem | Unclassified |

| PITG_12486 | Phyca11|570704 | Methionine‐tRNA ligase | 856 | 1.07E‐109 | 94.35 | Unc | Unclassified |

| PITG_18305 | Phyca11|503721 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 1533 | 0.00E+00 | 77.47 | Unc | Unclassified |

*From P. infestans protein database.

acc. no., accession number; CC, cellular component; Cyt, cytoplasm; Ext, extracellular compartment; Mem, membrane‐bound; Org, organelles; Unc, unclassified.

Table 2.

List of the Phytophthora capsici proteins with greater abundance in the cysts than in the mycelium.

| P. infestans acc. no. | P. capsici acc. no. | Description* | Score | E value | Hit identity (%) | CC | Functional category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PITG_10031 | Phyca11|534612 | Lysosomal α‐mannosidase | 1973 | 0.00E+00 | 80.67 | Ext | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| PITG_00682 | Phyca11|118794 | Carbonic anhydrase | 1486 | 0.00E+00 | 94.92 | Unc | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| PITG_07027 | Phyca11|503263 | Isocitrate lyase | 2591 | 0.00E+00 | 92.18 | Unc | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| PITG_07999 | Phyca11|575859 | α‐Tubulin | 2088 | 0.00E+00 | 91.01 | Cyt | Cytoskeleton |

| PITG_00156 | Phyca11|576734 | β‐Tubulin | 2199 | 0.00E+00 | 100.00 | Cyt | Cytoskeleton |

| PITG_09955 | Phyca11|529555 | Acyl‐CoA dehydrogenase family member 9 | 2929 | 0.00E+00 | 95.30 | Mem | Lipid metabolism |

| PITG_07197 | Phyca11|534354 | 3‐Ketoacyl‐CoA thiolase | 1517 | 0.00E+00 | 91.59 | Org | Lipid metabolism |

| PITG_13753 | Phyca11|118056 | Choline/carnitine O‐acyltransferase | 2965 | 0.00E+00 | 91.71 | Unc | Lipid metabolism |

| PITG_02282 | Phyca11|502783 | Acyl‐CoA dehydrogenase | 3670 | 0.00E+00 | 92.80 | Unc | Lipid metabolism |

| PITG_06693 | Phyca11|506742 | Trifunctional enzyme subunit α | 2980 | 0.00E+00 | 89.74 | Unc | Lipid metabolism |

| PITG_01208 | Phyca11|508178 | Trifunctional enzyme subunit β | 1998 | 0.00E+00 | 95.84 | Unc | Lipid metabolism |

| PITG_07024 | Phyca11|531975 | Inosine‐5′‐monophosphate dehydrogenase 2 | 2462 | 0.00E+00 | 95.64 | Cyt | Nucleobase‐containing compound metabolic process |

| PITG_08761 | Phyca11|505099 | Nucleoside diphosphate kinase B | 852 | 4.76E‐109 | 93.64 | Mem | Nucleobase‐containing compound metabolic process |

| PITG_13575 | Phyca11|557455 | ATP‐binding cassette (ABC) superfamily | 6567 | 0.00E+00 | 66.70 | Mem | Nucleobase‐containing compound metabolic process |

| PITG_07308 | Phyca11|506928 | rRNA 2′‐O‐methyltransferase fibrillarin | 1243 | 1.33E‐163 | 99.59 | Org | Nucleobase‐containing compound metabolic process |

| PITG_19178 | Phyca11|576174 | 13‐kDa ribonucleoprotein‐associated protein | 561 | 2.80E‐69 | 90.62 | Rib | Nucleobase‐containing compound metabolic process |

| PITG_09609 | Phyca11|13896 | Dpy‐30‐like protein | 276 | 8.57E‐30 | 90.00 | Unc | Nucleobase‐containing compound metabolic process |

| PITG_11046 | Phyca11|574456 | Creatine kinase B‐type | 2409 | 1.65E‐152 | 60.14 | Unc | Nucleobase‐containing compound metabolic process |

| PITG_02968 | Phyca11|534866 | Choline dehydrogenase | 2829 | 0.00E+00 | 91.10 | Unc | Other |

| PITG_12427 | Phyca11|511652 | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit mitochondrial‐like | 576 | 3.01E‐71 | 84.09 | Org | Pathogenesis/response to stress |

| PITG_17708 | Phyca11|511879 | Translationally controlled tumour protein | 908 | 2.91E‐117 | 95.00 | Unc | Pathogenesis/response to stress |

| PITG_06815 | Phyca11|539198 | NADH dehydrogenase flavoprotein 1 | 2483 | 0.00E+00 | 95.61 | Unc | Pathogenesis/response to stress |

| PITG_00850 | Phyca11|507542 | Thioredoxin‐dependent peroxide reductase | 1497 | 0.00E+00 | 93.49 | Unc | Pathogenesis/response to stress |

| PITG_03098 | Phyca11|538943 | Carbamoyl‐phosphate synthase | 7803 | 0.00E+00 | 81.91 | Mem | Protein metabolism |

| PITG_22685 | Phyca11|541961 | Dihydroxy‐acid dehydratase | 2585 | 0.00E+00 | 84.23 | Mem | Protein metabolism |

| PITG_03712 | Phyca11|503562 | Elongation factor 3 | 5249 | 0.00E+00 | 83.76 | Unc | Protein metabolism |

| PITG_08880 | Phyca11|563220 | ADP‐ribosylation factor family | 875 | 2.92E‐112 | 93.99 | Org | Signal transduction |

| PITG_05884 | Phyca11|531039 | AP‐2 complex subunit β | 4091 | 0.00E+00 | 94.02 | Cyt | Transport |

| PITG_04335 | Phyca11|558677 | AP‐2 complex subunit α | 4272 | 0.00E+00 | 92.44 | Cyt | Transport |

| PITG_08785 | Phyca11|505109 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 3677 | 0.00E+00 | 77.23 | Ext | Unclassified |

| PITG_08793 | Phyca11|505109 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 3801 | 0.00E+00 | 73.71 | Ext | Unclassified |

| PITG_05360 | Phyca11|506120 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 577 | 2.92E‐70 | 84.73 | Mem | Unclassified |

| PITG_20397 | Phyca11|555281 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 2192 | 0.00E+00 | 96.40 | Mem | Unclassified |

| PITG_06241 | Phyca11|505003 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 1579 | 4.21E‐133 | 68.78 | Unc | Unclassified |

*From P. infestans protein database.

acc. no., accession number; CC, cellular component; Cyt, cytoplasm; Ext, extracellular compartment; Mem, membrane‐bound; Org, organelles; Rib, ribosomes; Unc, unclassified.

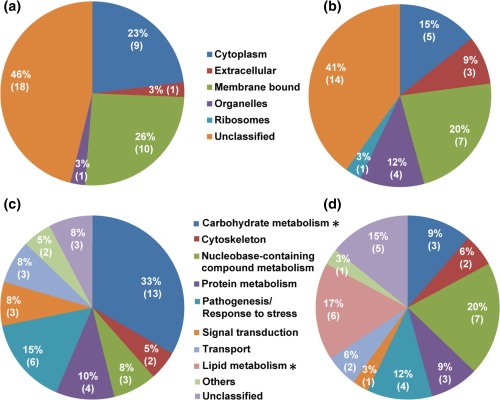

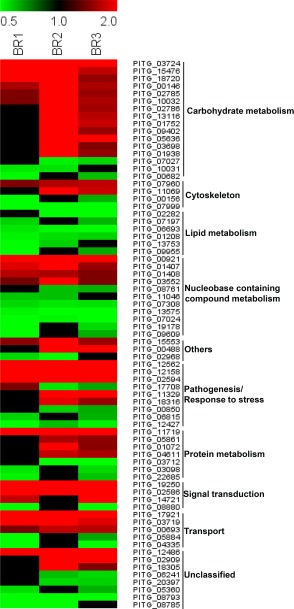

Although the gene ontology analysis failed to ascribe locations for many of the proteins from both the mycelium (46%) and cyst (41%) samples (Fig. 4a,b), it did reveal that the two samples had slightly different profiles, with a higher proportion of the mycelium (23%) relative to the cyst (15%) proteins being located in the cytoplasm, and a greater number of the cyst proteins being extracellular (9%) or associated with organelles (12%) compared with those of the mycelium (3% and 3%, respectively). The two samples also exhibited differences in the function of the enriched proteins (Figs 4c,d and 5). Most notably, the mycelium samples contained a much higher proportion of proteins associated with carbohydrate metabolism (33%) than did the cyst samples (9%). In contrast, the cyst samples contained a higher proportion of proteins associated with lipid metabolism (17%), compared with the mycelium. These data indicate that the two types of sample differ in their primary energy metabolism. The proteins associated with carbohydrate metabolism in the mycelium and those involved in lipid metabolism in the cysts were selected for pathway enrichment analysis. The results showed that the most enriched proteins were involved in glycolysis/gluconeogenesis (Fig. S1, Table S3, see Supporting Information), the pentose phosphate pathway (Fig. S2, Table S3, see Supporting Information), the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) (or citric acid) cycle (Fig. S3, Table S3, see Supporting Information) and fatty acid catabolism (Fig. S4, Table S3, see Supporting Information).

Figure 4.

Predicted cellular location (a, b) and functional annotation (c, d) of the differentially expressed proteins from the mycelium and cysts of P. capsici. (a and c) proteins with greater abundance in the mycelium; (b and d) proteins with greater abundance in the cysts. The asterisks mark the functional categories of proteins that present significantly different levels of expression between the mycelium and cysts (p < 0.05; Chi‐square test).

Figure 5.

Heat map illustrating the relative abundance of the significantly enriched proteins in the mycelium (red) and cysts (green) in all three biological replicates. Missing values are shown in black.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analyses

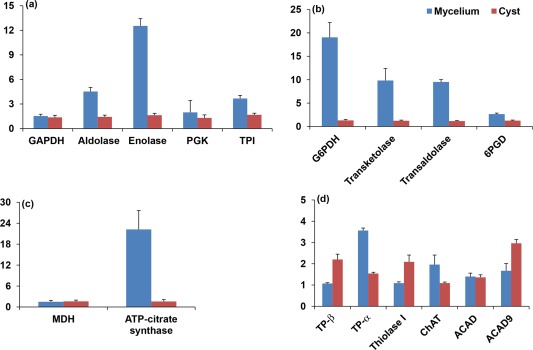

The relative levels of expression of the genes that encode the enriched proteins identified by iTRAQ analysis were determined using quantitative real‐time PCR. Although the expression levels of glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and malate dehydrogenase (MDH) did not differ between the mycelium and cysts, the mRNA levels of the other genes associated with glycolysis/gluconeogenesis (Fig. 6a), the pentose phosphate pathway (Fig. 6b) and the TCA cycle (Fig. 6c) corroborated the data from the iTRAQ experiments, with higher levels of expression in the mycelium than in the cysts. The genes associated with the fatty acid degradation pathway, i.e. the trifunctional enzyme subunit β (TP‐β), 3‐ketoacyl‐CoA thiolase (thiolase I) and acyl‐CoA dehydrogenase family member 9 (ACAD9), exhibited higher levels of expression in the cysts than in the mycelium (Fig. 6d), in good agreement with the quantitative proteomics data. However, in contrast with the data from the iTRAQ experiments, the expression levels of the trifunctional enzyme subunit α (TP‐α) and choline/carnitine O‐acyltransferase (ChAT) were higher in the mycelium than in the cysts (Fig. 6d).

Figure 6.

Expression profiles of selected genes from Phytophthora capsici. Expression levels of genes associated with: (a) glycolysis/gluconeogenesis; (b) the pentose phosphate pathway; (c) the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) (or citric acid) cycle; (d) fatty acid degradation. Relative expression levels were determined by comparison with the 40S ribosomal protein S3a (WS21) and mago nashi RNA‐binding protein homologue. They were calculated using Biogazelle qbase+. Error bars represent the standard deviation based on three biological replicates. ACAD, acyl‐CoA dehydrogenase; ACAD9, acyl‐CoA dehydrogenase family member 9; aldolase, fructose‐bisphosphate aldolase; ChAT, choline/carnitine O‐acyltransferase; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase; G6PDH, glucose‐6‐phosphate 1‐dehydrogenase; MDH, malate dehydrogenase; 6PGD, 6‐phosphogluconate dehydrogenase; PGK, phosphoglycerate kinase; thiolase I, 3‐ketoacyl‐CoA thiolase; TP‐α, trifunctional enzyme subunit α; TP‐β, trifunctional enzyme subunit β; TPI, triose‐phosphate isomerase.

Discussion

The asexual propagation of P. capsici is responsible for regular disease outbreaks that cause significant crop losses worldwide (Granke et al., 2009). Here, we have used a proteomics approach to identify proteins specifically associated with the two asexual life stages of P. capsici to gain further insights into the candidate proteins that might be involved in vegetative growth and the early stages of infection. The combination of iTRAQ‐liquid chromatography‐tandem MS (iTRAQ‐LC‐MS/MS) with a gel‐based qualitative analysis led to the identification of a total of 1200 unique proteins associated with the mycelium and cysts of P. capsici. Approximately 6% (69 proteins) of the proteins were predicted to contain signal peptides (Table S1), which is similar to the proportion of secreted proteins (8%) estimated by analysis of the Phytophthora genome (Haas et al., 2009; Jiang et al., 2006; Tyler et al., 2006). iTRAQ analysis revealed that 73 of the proteins exhibited significantly different levels of abundance between the mycelium and cyst samples. In the discussion that follows, the enriched proteins have been divided into two groups: those that showed higher abundance in the mycelium, which were considered to be candidate proteins for vegetative growth (Table 1), and those that showed higher abundance in the cysts, which were considered to be candidate proteins for early infection (Table 2).

Candidate proteins associated with vegetative growth (Group I)

Compared with the situation in the cysts (Figs 4d and 5), a higher proportion of the proteins that exhibited increased levels of abundance in the mycelium were associated with carbohydrate metabolism, protein metabolism, transport, pathogenesis/response to stress and signal transduction (Figs 4c and 5). Of the proteins for which a function could be assigned based on available annotations, the largest group was associated with carbohydrate metabolism. Similar results have been obtained in previous studies of other Phytophthora pathogens, including P. sojae (Hosseini et al., 2015; Savidor et al., 2008), P. pisi (Hosseini et al., 2015) and P. ramorum (Savidor et al., 2008). In our work, quantitative reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) analysis further confirmed the increased levels of expression of several genes associated with carbohydrate metabolism. The assignment of these proteins to metabolic pathways revealed that they are essentially involved in glycolysis/gluconeogenesis (Fig. S1), the pentose phosphate pathway (Fig. S2) and the TCA cycle (Fig. S3). The up‐regulation of proteins associated with gluconeogenesis suggests that P. capsici utilizes carbohydrates from its host environment for vegetative growth during the necrotrophic phase of the infection. However, the up‐regulation of proteins involved in glycolysis, the pentose phosphate pathway and TCA cycle could also reflect the conversion of nutrient reserves to usable energy to drive the biosynthetic processes needed for infection or growth and development of P. capsici. In addition, isoforms of GAPDH, which are associated with glycolysis, have been reported in the proteome of virulent strains of Botrytis cinerea, leading to the hypothesis that they might also act as virulence factors (Bhadauria et al., 2010). Similarly, another of the up‐regulated proteins is MDH, which is a ubiquitous regulatory enzyme of energy metabolism via the TCA cycle. MDH catalyses the reversible conversion of oxaloacetate, a precursor of oxalic acid, which is reported to be a pathogenicity factor of the ascomycete plant pathogen B. cinerea. Furthermore, it has also been reported that the acidification of the environment by oxalic acid stimulates the production of the botrydial and dihydrobotrydial toxins by B. cinerea (Fernández‐Acero et al., 2006). The important changes associated with energy metabolism observed in the mycelium were accompanied by the increased expression of proteins involved in protein anabolism, for example the up‐regulation of 5‐methyl‐tetrahydropteroyltriglutamate‐homocysteine methyltransferase, which catalyses the biosynthesis of the essential amino acid methionine.

Consistent with vegetative growth and the associated increased carbohydrate metabolism in the mycelium, our data also revealed an up‐regulation of transport proteins that facilitate the uptake of nutrients (Latijnhouwers et al., 2003). A key protein enriched in the mycelium is the plasma membrane H+‐ATPase, which generates a proton gradient across the cell membrane to provide the energy required for the transport of nutrients (glucose/fructose, amino acids) from the environment (Szabo and Bushnell, 2001).

Several of the proteins with increased abundance during mycelial growth were found to be directly associated with pathogenesis and response to stress. A typical example is an elicitin‐like protein, which is a member of the elicitin superfamily of proteins. This type of protein is structurally related to extracellular proteins that induce hypersensitive cell death and other biochemical changes associated with the defence response (Bonnet et al., 1996; Kamoun et al., 1993; Ricci et al., 1989; Van't Slot and Knogge, 2002). Previous studies have indicated that the elicitin‐like proteins from P. capsici exhibit phospholipase activity (Nespoulous et al., 1999), suggesting a general lipid binding/processing role for the various members of the elicitin family in this species (Osman et al., 2001). In addition, it has been suggested that such elicitins are essential to Phytophthora species, which are unable to synthesize sterols, possibly by playing a role in sterol assimilation from the environment (Kamoun, 2006). Another up‐regulated protein is phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase, which is known to provide protection against reactive oxygen species. The occurrence of phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase has also been reported during the in vitro vegetative growth of P. parasitica (Panabières et al., 2005). In addition, two annexins exhibited increased levels of abundance in the mycelium samples of P. capsici. The conserved annexin domains of these proteins contain a typical type‐2 calcium‐binding motif [GxGT‐(38 residues)‐E] (Benz and Hofmann, 1996), and the presence of these proteins in the cell walls of Phytophthora species suggests that they play an important role in the adhesion of the pathogen to the hosts and infection (Meijer et al., 2006).

Two orthologous 12‐oxophytodienoate reductase proteins (Phyca11|505536, Phyca11|506608) were also found to show increased abundance in the mycelium, and might be important during hyphal vegetative growth. blast searches revealed that the amino acid sequences of these two proteins showed a high degree of similarity (∼50%) with the 12‐oxophytodienoate reductase homologues found in Arabidopsis thaliana, which have been associated with jasmonate biosynthesis and plant responses to a variety of stimuli (Müssig et al., 2000; Schaller et al., 2000). The expression of 12‐oxophytodienoate reductase in P. capsici might therefore contribute to its virulence by influencing the stress responses of its host plants.

Another protein that might influence the vegetative growth of the mycelium is phospholipase D, which is known to be expressed in other Phytophthora species (Hosseini et al., 2015; Meijer et al., 2011, 2014; Savidor et al., 2008). Phospholipase D is a member of the phospholipase superfamily, and is responsible for the hydrolysis of phosphatidylcholine to produce soluble choline and the signal molecule phosphatidic acid. Proteins belonging to the phospholipase superfamily participate in various cellular processes, including phospholipid metabolism and signal transduction (Cazzolli et al., 2006; Meijer et al., 2005). Although the precise function of phospholipase D in the biology of Phytophthora diseases has not been determined, its consistently high abundance during vegetative growth suggests that it may have a conserved function in Phytophthora, perhaps facilitating biochemical processes important for the proliferation of the mycelium within the host tissue.

Candidate proteins specifically involved in cyst development (Group II)

Thirty‐four differentially expressed proteins were up‐regulated in the cysts (Table 2). However, compared with mycelium (Figs 4c and 5), a higher proportion of these proteins could not be functionally annotated (Figs 4d and 5), reflecting the fact that many of the proteins associated with cyst development have yet to be characterized in P. capsici and other related organisms.

The single largest functional category for the proteins that could be annotated was lipid metabolism, which accounted for 17% of the differentially expressed proteins. This indicates that lipid metabolism is one of the most distinctive processes that quantitatively distinguishes the mycelium and the cysts. The up‐regulated proteins associated with lipid metabolism included ACAD9, thiolase I, ChAT, acyl‐CoA dehydrogenase, TP‐α and TP‐β. The increased expression of TP‐β, thiolase I and ACAD9 was confirmed by quantitative real‐time RT‐PCR analysis. Interestingly, however, higher mRNA expression levels of TP‐α and ChAT were measured in the mycelium samples, which might have been caused by regulation at the post‐transcriptional level (Brockmann et al., 2007). Metabolic pathway enrichment analysis revealed that the enriched proteins were involved in fatty acid degradation (Fig. S4), which produces greater amounts of energy than does carbohydrate catabolism. Previous studies have also shown that proteins involved in fatty acid degradation are up‐regulated in the germinating cysts of other Phytophthora species (Ebstrup et al., 2005; Hosseini et al., 2015; Savidor et al., 2008), which suggests that fatty acid degradation via the β‐oxidation pathway serves as the primary source of energy in the cysts, ‘fuelling’ germination and penetration of the hosts. The up‐regulation of isocitrate lyase provides further confirmation of this hypothesis, as this protein is a key enzyme that catalyses the cleavage of isocitrate to succinate and glyoxylate as part of the glyoxylate cycle. The glyoxylate cycle is involved in the conversion of acetyl‐CoA from fatty acid degradation to succinate for the synthesis of carbohydrates, and is required for the virulence of fungi (Lorenz and Fink, 2001).

A member of the ATP‐binding cassette (ABC) superfamily, assigned to the category nucleobase‐containing compound metabolic process, was found to be up‐regulated in the cysts. Proteins belonging to this family have previously been associated with detoxification (Torto‐Alalibo et al., 2007), and it is possible that a similar role in the plant–pathogen interaction of P. capsici could contribute to the success of infection. In addition, ABC proteins have also been implicated in the secretion of phytotoxins (Chen et al., 2011; Connolly et al., 2005), which would also increase the virulence of P. capsici. Other proteins associated with the nucleobase‐containing compound metabolic process included rRNA 2′‐O‐methyltransferase fibrillarin, 13‐kDa ribonucleoprotein‐associated protein and creatine kinase B‐type protein. Both the rRNA 2′‐O‐methyltransferase fibrillarin and 13‐kDa ribonucleoprotein‐associated protein are known to be involved in ribosomal RNA processing (Bonnerot et al., 2003; Monaghan et al., 2009), whereas the creatine kinase B‐type protein catalyses the transfer of a phosphoryl group from phosphocreatine to ADP to form creatine and ATP, a process that buffers the levels of ATP in cell types with high energy demands (Kim and Judelson, 2003). A similar role could be played by this protein during cyst germination, which is expected to require high levels of energy. In addition, elongation factor 3, which is involved in protein biosynthesis, and the cytoskeleton proteins α‐tubulin and β‐tubulin, were also found to be up‐regulated in the cysts, indicating that these proteins could play an important role in the production of large amounts of cytoskeleton proteins, as well as other proteins necessary for cyst development.

Several other proteins that could be pathogenicity factors were also found to be up‐regulated in the cysts. For example, lysosomal α‐mannosidase, which is involved in the breakdown of complex glycans derived from glycoproteins (De Gasperi et al., 1992), has been observed to be up‐regulated in the germinating cysts of P. ramorum and P. sojae (Savidor et al., 2008). This suggests that it could have a conserved function, allowing Phytophthora pathogens to utilize host glycoproteins. In addition, carbonic anhydrase has been reported to be a candidate virulence factor in P. infestans based on bioinformatics analysis (Raffaele et al., 2010).

In summary, the data presented here provide evidence for a more specific involvement of carbohydrate and fatty acid metabolic pathways in the vegetative growth of the mycelium and development of cysts, respectively. In the mycelium, many of the up‐regulated proteins were found to be related to energy production via glycolysis, the pentose phosphate pathway and the TCA cycle, which drive the biosynthesis of, for example, amino acids, for vegetative growth. A second group of candidate proteins associated with the adaptation and survival of the pathogen were also identified, including an elicitin‐like protein, phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase, two annexins, 12‐oxophytodienoate reductase proteins and phospholipase D. As opposed to the mycelium, the cysts appeared to obtain their energy essentially from fatty acid degradation, ‘fuelling’ germination and penetration of the hosts. In addition, several candidate pathogenicity factors were identified, including an ABC superfamily protein, lysosomal α‐mannosidase and carbonic anhydrase. Their involvement in the early stages of infection remains to be demonstrated experimentally.

Experimental Procedures

Cultures of P. capsici and extraction of proteins from mycelium and cysts

Cultures of P. capsici isolate Hd11 were established as described previously (Pang et al., 2013) and maintained on potato dextrose agar (PDA). The mycelium was collected from 3‐day‐old cultures (potato dextrose broth) of 100 mL grown at 25 ºC in the dark, whereas the asexual sporangia and zoospores were obtained by growing P. capsici on V8 agar plates under 12‐h light/12‐h dark cycles over a period of 7 days (Pang et al., 2014). The zoospores were stimulated to encyst by vigorous shaking for 1–2 min. The mycelium and cysts were harvested and stored at −80 ºC until further use.

For protein extraction, the mycelial and cyst cells were disrupted using a pestle and mortar or glass beads, respectively. Lysis buffer was added to each of the samples [250 µL of 100 mm triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB), 4% sodium deoxycholate (SDC) and 1 mm ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)], which were subsequently incubated at 80 ºC for 5 min and chilled on ice. Low‐temperature sonication (Branson® Sonifier 250, BRANSON Ultrasonics Corporation, Danbury, CT, USA) was used to assist cell lysis. The samples were then centrifuged at 100 000 g for 30 min to remove cell debris. The supernatant was collected and the protein concentration was determined using the Bradford assay (Bradford, 1976).

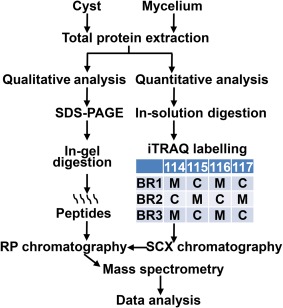

Sample preparation for qualitative and quantitative proteomics

A preliminary analysis of the qualitative differences between the protein profiles of the mycelium and cysts of P. capsici was conducted by SDS‐PAGE. Samples of the mycelium and cysts containing 20 µg of total protein were analysed on 10% SDS‐polyacrylamide gels. After staining with Coomassie blue (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA), each lane of the gel was cut into 17 bands of similar volume from the top to the bottom of the gel, and the proteins were subjected to in‐gel proteolysis and analysed by MS, as described previously (Srivastava et al., 2013).

For quantitative proteomics, mycelial and cyst lysates, prepared as described above (aliquots containing 100 µg of protein), were diluted in 0.05 m TEAB containing 1% sodium deoxycholate (SDC). The proteins were reduced, alkylated and hydrolysed in the presence of trypsin (Srivastava et al., 2013). The resulting peptides were labelled with iTRAQ reagents (114–117; AB SCIEX, Foster City, CA, USA), following the manufacturer's instructions. The iTRAQ tags used for the technical and biological replicates are shown in Fig. 7. The labelled peptides from each biological replicate were combined (Fig. 7), dried and re‐suspended in 10 mm ammonium formate, pH 3.0, containing 10% acetonitrile (loading buffer). The mixtures were then loaded onto 1‐mL Nuvia™ HR‐S cartridges (Bio‐Rad, Munich, Germany), which were prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions, using a syringe pump. After washing the cartridges with loading buffer, the peptides were eluted at a rate of 0.2 mL/min by the sequential addition of 1.5‐mL ammonium formate salt plugs (50, 75, 100, 125, 150, 175, 200, 225, 250, 275, 300, 325, 350 and 400 mm in 20% acetonitrile) at pH 3.0. Each fraction was dried, desalted using C18 Spin Columns (Thermo Scientific) and analysed by MS.

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of the experimental workflow. BR, biological replicate; iTRAQ, isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantification; RP, reverse phase; SCX, strong cation‐exchange chromatography; SDS‐PAGE, sodium dodecylsulfate‐polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

Nano‐LC‐MS/MS analysis of samples subjected to iTRAQ labelling

Reverse‐phase LC‐electrospray ionization‐MS/MS analysis of the peptide samples subjected to iTRAQ labelling was performed using a nanoACQUITY ultra‐performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) system (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) coupled to a Q‐TOF mass spectrometer (Xevo Q‐TOF, Waters). Before analysis, the purified peptide fractions corresponding to each salt plug were re‐suspended in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), loaded onto a C18 trap column (Symmetry 180 µm × 20 mm, 5 µm; Waters) and washed with 0.1% (v/v) formic acid at 10 µL/min for 10 min. The samples eluted from the trap column were then separated on a C18 analytical column (75 µm × 200 mm, 1.7 µm; Waters) at a rate of 225 nL/min using 0.1% formic acid as solvent A and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile as solvent B. The proportion of solvent B varied as follows: 0.1%–8% B (0–5 min), 8%–25% B (5–185 min), 25%–45% B (185–201 min), 45%–90% B (201–205 min), 90% B (205–213 min) and 90%–0.1% B (213–215 min). The eluting peptides were sprayed into the mass spectrometer with the capillary and cone voltages set to 2.2 kV and 45 V, respectively. The five most abundant signals from a survey scan (400–1300 m/z range; scan time, 1 s) were then selected by charge state, and the appropriate collision energy was applied for sequential MS/MS fragmentation (50–1800 m/z range; scan time, 1 s).

Data processing and protein identification and quantification

Our in‐house Automated Proteomics Pipeline, which automates the processing of proteomics tasks, such as peptide identification, validation and quantification from LC‐MS/MS data, and allows easy integration of many separate proteomics tools (Malm et al., 2014), was used to analyse the MS data. The raw MS data file was first analysed using the Mascot Distiller software (version 2.4.3.2, Matrix Science, London, UK) and the resulting mgf files were converted into the mzML file format using msconvert (Kessner et al., 2008). The P. infestans protein database (http://www.broadinstitute.org/annotation/genome/phytophthora_infestans/MultiHome.html; 18 141 entries) was then searched using several algorithms in parallel, i.e. MS‐GF+ (Kim et al., 2010) v1.0 (v8299), MyriMatch (Tabb et al., 2007) (version 2.1.120), Comet (Eng et al., 2013) (version 2013.01 rev.0) and X!Tandem (Craig and Beavis, 2004) (version 2011.12.01.1; LabKey, Insilicos, ISB, Seattle, WA, USA). The following settings were used for the searches: trypsin‐specific digestion with two missed cleavages allowed; peptide tolerance of 200 ppm; fragment tolerance of 0.5 Da; methylthio on cysteine (Cys) and iTRAQ 4‐plex for peptide N‐t and lysine (Lys) used as fixed modifications; oxidized methionine (Met) and tyrosine (Tyr) for iTRAQ 4‐plex analysis in variable mode. The results from all search engines were validated by PeptideProphet (Keller et al., 2002). Protein quantification was performed from the intensities of the iTRAQ reporter ions, which were extracted using the TPP tool Libra (Li et al., 2003) (TPP v4.6 OCCUPY rev 3) after the isotopic correction factors provided by the manufacturer of the iTRAQ reagent had been applied. The iTRAQ channels were normalized using the sum of all the reporter ion intensities from each iTRAQ channel and equalizing each channel's contribution by dividing the individual reporter ion intensities by the corresponding channel‐specific correction factor. The pep.xml files obtained from PeptideProphet were combined using iProphet (Shteynberg et al., 2011) and the protein lists were assembled using ProteinProphet (Nesvizhskii et al., 2003). The final protein ratios were calculated using LibraProteinRatioParser (Li et al., 2003), and a concatenated target‐decoy database search strategy showed that the rate of false positives was less than 1% for all searches.

Sequences with a peptide probability cut‐off of 0.95 were exported for each protein. Peptides matching two or more proteins (shared peptides) were excluded from the analysis, together with proteins that had no unique peptides (i.e. identified by shared peptides only). In each biological replicate, proteins identified by at least one unique peptide were considered to be identified, and those identified by two or more unique peptides were used for quantitative analysis. The mycelium to cyst ratio of each protein was calculated for each of the three biological replicates (Table S1) and log2 transformed to obtain a normal distribution (Ross et al., 2004) before statistical analysis of the quantitative data was conducted. The values were normalized to the median logarithm values, and the global means and standard deviations were calculated for each biological replicate. Proteins with average ratios outside ±1 standard deviations from the global mean in at least two of the three biological replicates were considered to be significantly enriched (Ross et al., 2004). MultiExperiment Viewer (MeV version 4.9.0) (Saeed et al., 2006) was used to construct the relative protein abundance heat map.

The MS proteomics data have been deposited at the ProteomeXchange Consortium (Vizcaíno et al., 2014) via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD002603.

Bioinformatics analysis

The P. infestans protein database was used in the first instance for protein identification because the analysis, annotation and curation of the genome of this species are much advanced compared with those of P. capsici. In addition, a high level of sequence identity has been shown to occur between the two genomes (Lamour et al., 2012a). The sequences of all proteins identified using the P. infestans database were used for blast searches against the P. capsici database. The accession numbers, e‐values, scores and percentage hit identities of the resulting top hit matches from P. capsici were extracted and are listed in Tables 1, 2 and S1. Gene ontology annotation of the identified proteins was performed using Blast2GO (Conesa and Götz, 2008), and conserved domains were analysed using the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) conserved domain database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi). The presence of signal peptides was predicted using SignalP (version 4.1) with the default settings (Petersen et al., 2011), and transmembrane domains were predicted using HMMTOP 2.0 (Tusnady and Simon, 2001). The sorting and grouping of the identified proteins was performed based on the data resulting from these analyses, in combination with literature searches. Enrichment analysis of candidate proteins from different metabolic pathways and metabolic reconstruction were conducted based on the information available in the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Pathway Database (www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html).

RNA extraction and quantitative RT‐PCR analysis

Total RNA was obtained from frozen P. capsici mycelium and cyst samples by grinding them in liquid nitrogen and extracting the RNA using an RNeasy® kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Sweden) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Contaminating DNA was removed from the RNA samples using a TURBO DNA‐free™ kit (Ambion, Austin, Texas, USA) and first‐strand cDNA synthesis was performed from 1 µg of total RNA using the Maxima First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The primers used for the analyses, including primers for control genes and primers for genes involved in glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, the pentose phosphate pathway, the TCA cycle and the fatty acid degradation pathway, are listed in Table S2 (see Supporting Information). qRT‐PCR analyses were performed using a CFX96 real‐time PCR detection system from Bio‐Rad, Munich, Germany. Reaction mixtures had a final volume of 10 µL and consisted of 5 µL of 2 × iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio‐Rad, Singapore), 0.5 µm of each primer and 2 µL of cDNA that had been diluted 15‐fold. The PCR was processed using the following program: 95°C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of 10 s at 95°C, 10 s at 60°C and 10 s at 72°C. Melting curves were generated at the end of the experiment to check the specificity of the PCR products. The raw data from three individual biological replicates were analysed using Biogazelle's qbasePLUS software version 3.0 (Hellemans et al., 2007). Relative expression levels were calculated by normalizing the data to the geometric mean of two reference genes [40S ribosomal protein S3a, WS21 (Yan and Liou, 2006), and mago nashi RNA‐binding protein homologue (Vetukuri et al., 2011)], which were selected from an expression stability analysis of five reference genes using geNorm (D'haene et al., 2012) (Table S2). The PCR efficiency for each gene was calculated using Real‐time PCR Miner (Zhao and Fernald, 2005), which confirmed that they were all in the 85%–100% range.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's website:

Table S1. List of unique proteins and their corresponding peptides obtained from in‐gel and solution (iTRAQ) proteomics analysis.

Table S2. List of oligonucleotide primer pairs used for reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) analysis.

Table S3. List of identified proteins involved in glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, the pentose phosphate pathway, the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) (or citric acid) cycle and the fatty acid degradation pathway.

Fig S1. Glycolysis/gluconeogenesis pathway. All of the proteins presented were identified by proteomics and the enzymes marked in red were found to be up‐regulated in the mycelium of Phytophthora capsici. These include fructose‐bisphosphate aldolase (Phyca11|507726), triose‐phosphate isomerase (TPI; Phyca11|506671), glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase (Phyca11|504523), phosphoglycerate kinase (Phyca11|510172) and enolase (Phyca11|503568).

Fig S2. Pentose phosphate pathway. The figure represents the enzymes that were identified by proteomics analysis. The proteins marked in red were found to be up‐regulated in the mycelium of Phytophthora capsici, including glucose‐6‐phosphate 1‐dehydrogenase (Phyca11|509625), transketolase (Phyca11|506857), transaldolase (Phyca11|505958) and 6‐phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (Phyca11|507227).

Fig S3. Tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (or citric acid cycle). All of the enzymes presented were identified in this work. Malate dehydrogenase (Phyca11|505882) and ATP‐citrate synthase (Phyca11|504894) were found to be up‐regulated in the mycelium of Phytophthora capsici (red).

Fig S4. Fatty acid degradation via the β‐oxidation pathway. All of the proteins presented were identified by proteomics analysis and assigned to the catabolism of fatty acid. The proteins up‐regulated in the cysts of Phytophthora capsici are shown in red and correspond to choline/carnitine O‐acyltransferase (Phyca11|118056), acyl‐CoA dehydrogenase (Phyca11|502783, Phyca11|529555), trifunctional enzyme subunit β (Phyca11|508178), trifunctional enzyme subunit α (Phyca11|506742) and 3‐ketoacyl‐CoA thiolase (Phyca11|534354).

Acknowledgements

This work was partially funded by the National Science Foundation of China (31272061), the Special Fund for Agro‐scientific Research in the Public Interest (201303023) and the Swedish Science Council FORMAS (grant # 2009‐515 to VB). ZP was supported by the China Scholarship Council programme.

Contributor Information

Xili Liu, Email: seedling@cau.edu.cn.

Vincent Bulone, Email: bulone@kth.se.

References

- Benz, J. and Hofmann, A. (1996) Annexins: from structure to function. Biol. Chem. 378, 177–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt, E. and Grogan, R. (1982) Effect of soil matric potential on the formation and indirect germination of sporangia of Phytophthora parasitica, Phytophthora capsici, and Phytophthora cryptogea . Phytopathology, 72, 507–511. [Google Scholar]

- Bhadauria, V. , Banniza, S. , Wang, L.X. , Wei, Y.D. and Peng, Y.L. (2010) Proteomic studies of phytopathogenic fungi, oomycetes and their interactions with hosts. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 126, 81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnerot, C. , Pintard, L. and Lutfalla, G. (2003) Functional redundancy of Spb1p and a snR52‐dependent mechanism for the 2′‐O‐ribose methylation of a conserved rRNA position in yeast. Mol. Cell, 12, 1309–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet, P. , Bourdon, E. , Ponchet, M. , Blein, J.P. and Ricci, P. (1996) Acquired resistance triggered by elicitins in tobacco and other plants. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 102, 181–192. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, J. , Papavizas, G. and Johnston, S. (1990) Effect of soil temperature and soil–water matric potential on the survival of Phytophthora capsici in natural soil. Plant Dis. 74, 771–777. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, M.M. (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein–dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockmann, R. , Beyer, A. , Heinisch, J.J. and Wilhelm, T. (2007) Posttranscriptional expression regulation: what determines translation rates? PLoS Comput. Biol. 3, e57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazzolli, R. , Shemon, A.N. , Fang, M.Q. and Hughes, W.E. (2006) Phospholipid signalling through phospholipase D and phosphatidic acid. IUBMB Life, 58, 457–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X. , Klemsdal, S.S. and Brurberg, M.B. (2011) Identification and analysis of Phytophthora cactorum genes up‐regulated during cyst germination and strawberry infection. Curr. Genet. 57, 297–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conesa, A. and Götz, S. (2008) Blast2GO: a comprehensive suite for functional analysis in plant genomics. Int. J. Plant Genomics, 2008, 619832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly, M.S. , Sakihama, Y. , Phuntumart, V. , Jiang, Y. , Warren, F. , Mourant, L. and Morris, P.F. (2005) Heterologous expression of a pleiotropic drug resistance transporter from Phytophthora sojae in yeast transporter mutants. Curr. Genet. 48, 356–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig, R. and Beavis, R.C. (2004) TANDEM: matching proteins with tandem mass spectra. Bioinformatics, 20, 1466–1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Gasperi, R. , Daniel, P. and Warren, C. (1992) A human lysosomal alpha‐mannosidase specific for the core of complex glycans. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 9706–9712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'haene, B. , Mestdagh, P. , Hellemans, J. and Vandesompele, J. (2012) miRNA expression profiling: from reference genes to global mean normalization In: Next‐Generation MicroRNA Expression Profiling Technology (Fan J.B., ed.), pp. 261–272. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebstrup, T. , Saalbach, G. and Egsgaard, H. (2005) A proteomics study of in vitro cyst germination and appressoria formation in Phytophthora infestans . Proteomics, 5, 2839–2848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng, J.K. , Jahan, T.A. and Hoopmann, M.R. (2013) Comet: an open‐source MS/MS sequence database search tool. Proteomics, 13, 22–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin, D.C. and Ribeiro, O.K. (1996) Phytophthora Diseases Worldwide. St. Paul, MN: The American Phytopathological Society Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández‐Acero, F.J. , Jorge, I. , Calvo, E. , Vallejo, I. , Carbú, M. , Camafeita, E. , López, J.A. and Cantoral, J.M. , Jorrín, J. (2006) Two‐dimensional electrophoresis protein profile of the phytopathogenic fungus Botrytis cinerea . Proteomics, 6, S88–S96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gevens, A. , Donahoo, R. , Lamour, K. and Hausbeck, M. (2008) Characterization of Phytophthora capsici causing foliar and pod blight of snap bean in Michigan. Plant Dis. 92, 201–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobena, D. , Roig, J. , Galmarini, C. , Hulvey, J. and Lamour, K. (2012) Genetic diversity of Phytophthora capsici isolates from pepper and pumpkin in Argentina. Mycologia, 104, 102–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granke, L. , Windstam, S. , Hoch, H. , Smart, C. and Hausbeck, M. (2009) Dispersal and movement mechanisms of Phytophthora capsici sporangia. Phytopathology, 99, 1258–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas, B.J. , Kamoun, S. , Zody, M.C. , Jiang, R.H. , Handsaker, R.E. , Cano, L.M. , Grabherr, M. , Kodira, C.D. , Raffaele, S. and Torto‐Alalibo, T. (2009) Genome sequence and analysis of the Irish potato famine pathogen Phytophthora infestans . Nature, 461, 393–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausbeck, M.K. and Lamour, K.H. (2004) Phytophthora capsici on vegetable crops: research progress and management challenges. Plant Dis. 88, 1292–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellemans, J. , Mortier, G. , De Paepe, A. , Speleman, F. and Vandesompele, J. (2007) qBase relative quantification framework and software for management and automated analysis of real‐time quantitative PCR data. Genome Biol. 8, R19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, S. , Resjö, S. , Liu, Y. , Durling, M. , Heyman, F. , Levander, F. , Liu, Y. , Elfstrand, M. , Jensen, D.F. and Andreasson, E. (2015) Comparative proteomic analysis of hyphae and germinating cysts of Phytophthora pisi and Phytophthora sojae . J. Proteomics, 117, 24–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, R.H. , Tyler, B.M. and Govers, F. (2006) Comparative analysis of Phytophthora genes encoding secreted proteins reveals conserved synteny and lineage‐specific gene duplications and deletions. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 19, 1311–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamoun, S. (2006) A catalogue of the effector secretome of plant pathogenic oomycetes. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 44, 41–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamoun, S. , Klucher, K.M. , Coffey, M.D. and Tyler, B.M. (1993) A gene encoding a host‐specific elicitor protein of Phytophthora parasitica . Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 6, 573–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamoun, S. , Furzer, O. , Jones, J.D. , Judelson, H.S. , Ali, G.S. , Dalio, R.J. , Roy, S.G. , Schena, L. , Zambounis, A. and Panabières, F. (2015) The top 10 oomycete pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant. Pathol. 16, 413–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller, A. , Nesvizhskii, A.I. , Kolker, E. and Aebersold, R. (2002) Empirical statistical model to estimate the accuracy of peptide identifications made by MS/MS and database search. Anal. Chem. 74, 5383–5392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessner, D. , Chambers, M. , Burke, R. , Agus, D. and Mallick, P. (2008) ProteoWizard: open source software for rapid proteomics tools development. Bioinformatics, 24, 2534–2536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.S. and Judelson, H.S. (2003) Sporangium‐specific gene expression in the oomycete phytopathogen Phytophthora infestans . Eukaryot. Cell, 2, 1376–1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. , Mischerikow, N. , Bandeira, N. , Navarro, J.D. , Wich, L. , Mohammed, S. , Heck, A.J. and Pevzner, P.A. (2010) The generating function of CID, ETD, and CID/ETD pairs of tandem mass spectra: applications to database search. Mol. Cell. Proteomics, 9, 2840–2852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamour, K. and Kamoun, S. (2009) Oomycete Genetics and Genomics: Diversity, Interactions and Research Tools. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley‐Blackwell Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lamour, K.H. , Mudge, J. , Gobena, D. , Hurtado‐Gonzales, O.P. , Schmutz, J. , Kuo, A. , Miller, N.A. , Rice, B.J. , Raffaele, S. and Cano, L.M. (2012a) Genome sequencing and mapping reveal loss of heterozygosity as a mechanism for rapid adaptation in the vegetable pathogen Phytophthora capsici. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 25, 1350–1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamour, K.H. , Stam, R. , Jupe, J. and Huitema, E. (2012b) The oomycete broad‐host‐range pathogen Phytophthora capsici . Mol. Plant. Pathol. 13, 329–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latijnhouwers, M. , De Wit, P.J. and Govers, F. (2003) Oomycetes and fungi: similar weaponry to attack plants. Trends Microbiol. 11, 462–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonian, L.H. (1922) Stem and fruit blight of peppers caused by Phytophthora capsici sp. nov. Phytopathology, 12, 401–408. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.J. , Zhang, H. , Ranish, J.A. and Aebersold, R. (2003) Automated statistical analysis of protein abundance ratios from data generated by stable‐isotope dilution and tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 75, 6648–6657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz, M.C. and Fink, G.R. (2001) The glyoxylate cycle is required for fungal virulence. Nature, 412, 83–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malm, E.K. , Srivastava, V. , Sundqvist, G. and Bulone, V. (2014) APP: an Automated Proteomics Pipeline for the analysis of mass spectrometry data based on multiple open access tools. BMC Bioinformatics, 15, 441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer, H.J. , Latijnhouwers, M. , Ligterink, W. and Govers, F. (2005) A transmembrane phospholipase D in Phytophthora; a novel PLD subfamily. Gene, 350, 173–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer, H.J. , van de Vondervoort, P.J. , Yin, Q.Y. , de Koster, C.G. , Klis, F.M. , Govers, F. and de Groot, P.W. (2006) Identification of cell wall‐associated proteins from Phytophthora ramorum . Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 19, 1348–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer, H.J. , Hassen, H.H. and Govers, F. (2011) Phytophthora infestans has a plethora of phospholipase D enzymes including a subclass that has extracellular activity. PLoS One, 6, e17767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer, H.J. , Mancuso, F.M. , Espadas, G. , Seidl, M.F. , Chiva, C. , Govers, F. and Sabidó, E. (2014) Profiling the secretome and extracellular proteome of the potato late blight pathogen Phytophthora infestans . Mol. Cell. Proteomics, 13, 2101–2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monaghan, J. , Xu, F. , Gao, M. , Zhao, Q. , Palma, K. , Long, C. , Chen, S. , Zhang, Y. and Li, X. (2009) Two Prp19‐like U‐Box proteins in the MOS4‐associated complex play redundant roles in plant innate immunity. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müssig, C. , Biesgen, C. , Lisso, J. , Uwer, U. , Weiler, E.W. and Altmann, T. (2000) A novel stress‐inducible 12‐oxophytodienoate reductase from Arabidopsis thaliana provides a potential link between brassinosteroid‐action and jasmonic‐acid synthesis. J. Plant Physiol. 157, 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Nespoulous, C. , Gaudemer, O. , Huet, J.C. and Pernollet, J.C. (1999) Characterization of elicitin‐like phospholipases isolated from Phytophthora capsici culture filtrate. FEBS Lett. 452, 400–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesvizhskii, A.I. , Keller, A. , Kolker, E. and Aebersold, R. (2003) A statistical model for identifying proteins by tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 75, 4646–4658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman, H. , Mikes, V. , Milat, M.L. , Ponchet, M. , Marion, D. , Prange, T. , Maume, B. , Vauthrin, S. and Blein, J.P. (2001) Fatty acids bind to the fungal elicitor cryptogein and compete with sterols. FEBS Lett. 489, 55–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panabières, F. , Amselem, J. , Galiana, E. and Le Berre, J.Y. (2005) Gene identification in the oomycete pathogen Phytophthora parasitica during in vitro vegetative growth through expressed sequence tags. Fungal Genet. Biol. 42, 611–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang, Z. , Shao, J. , Chen, L. , Lu, X. , Hu, J. , Qin, Z. and Liu, X. (2013) Resistance to the novel fungicide pyrimorph in Phytophthora capsici: risk assessment and detection of point mutations in CesA3 that confer resistance. PLoS One, 8, e56513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang, Z. , Shao, J. , Hu, J. , Chen, L. , Wang, Z. , Qin, Z. and Liu, X. (2014) Competition between pyrimorph‐sensitive and pyrimorph‐resistant isolates of Phytophthora capsici . Phytopathology, 104, 269–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, T.N. , Brunak, S. , von Heijne, G. and Nielsen, H. (2011) SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat. Methods, 8, 785–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quesada‐Ocampo, L. , Granke, L. , Mercier, M. , Olsen, J. and Hausbeck, M. (2011) Investigating the genetic structure of Phytophthora capsici populations. Phytopathology, 101, 1061–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffaele, S. , Win, J. , Cano, L.M. and Kamoun, S. (2010) Analyses of genome architecture and gene expression reveal novel candidate virulence factors in the secretome of Phytophthora infestans . BMC Genomics, 11, 637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci, P. , Bonnet, P. , Huet, J.C. , Sallantin, M. , Beauvais‐Cante, F. , Bruneteau, M. , Billard, V. and Michel, G. , Pernollet, J.C. (1989) Structure and activity of proteins from pathogenic fungi Phytophthora eliciting necrosis and acquired resistance in tobacco. Eur. J. Biochem. 183, 555–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risiamo, J. , Respess, K. , Sullivan, T. and Whittington, D. (1991) Influence of rainfall, drip irrigation, and inoculum density on the development of Phytophthora root and crown rot epidemics and yield in bell pepper. Phytopathology, 81, 922–929. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, P.L. , Huang, Y.N. , Marchese, J.N. , Williamson, B. , Parker, K. , Hattan, S. , Khainovski, N. , Pillai, S. , Dey, S. and Daniels, S. (2004) Multiplexed protein quantitation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using amine‐reactive isobaric tagging reagents. Mol. Cell. Proteomics, 3, 1154–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, A.I. , Bhagabati, N.K. , Braisted, J.C. , Liang, W. , Sharov, V. , Howe, E.A. , Li, J.W. , Thiagarajan, M. , White, J.A. and Quackenbush, J. (2006) TM4 microarray software suite. Methods Enzymol. 411, 134–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satour, M. and Butler, E. (1968) Comparative morphological and physiological studies of progenies from intraspecific matings of Phytophthora capsici . Phytopathology, 58, 183–192. [Google Scholar]

- Savidor, A. , Donahoo, R.S. , Hurtado‐Gonzales, O. , Land, M.L. , Shah, M.B. , Lamour, K.H. and McDonald, W.H. (2008) Cross‐species global proteomics reveals conserved and unique processes in Phytophthora sojae and Phytophthora ramorum . Mol. Cell. Proteomics, 7, 1501–1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller, F. , Biesgen, C. , Müssig, C. , Altmann, T. and Weiler, E.W. (2000) 12‐Oxophytodienoate reductase 3 (OPR3) is the isoenzyme involved in jasmonate biosynthesis. Planta, 210, 979–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shteynberg, D. , Deutsch, E.W. , Lam, H. , Eng, J.K. , Sun, Z. , Tasman, N. , Mendoza, L. , Moritz, R.L. , Aebersold, R. and Nesvizhskii, A.I. (2011) iProphet: multi‐level integrative analysis of shotgun proteomic data improves peptide and protein identification rates and error estimates. Mol. Cell. Proteomics, 10, M111.007690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, V. , Malm, E. , Sundqvist, G. and Bulone, V. (2013) Quantitative proteomics reveals that plasma membrane microdomains from poplar cell suspension cultures are enriched in markers of signal transduction, molecular transport, and callose biosynthesis. Mol. Cell. Proteomics, 12, 3874–3885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo, L.J. and Bushnell, W.R. (2001) Hidden robbers: the role of fungal haustoria in parasitism of plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 7654–7655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabb, D.L. , Fernando, C.G. and Chambers, M.C. (2007) MyriMatch: highly accurate tandem mass spectral peptide identification by multivariate hypergeometric analysis. J. Proteome Res. 6, 654–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torto‐Alalibo, T.A. , Tripathy, S. , Smith, B.M. , Arredondo, F.D. , Zhou, L. , Li, H. , Chibucos, M.C. , Qutob, D. , Gijzen, M. and Mao, C. (2007) Expressed sequence tags from Phytophthora sojae reveal genes specific to development and infection. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 20, 781–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tusnady, G.E. and Simon, I. (2001) The HMMTOP transmembrane topology prediction server. Bioinformatics, 17, 849–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, B.M. , Tripathy, S. , Zhang, X. , Dehal, P. , Jiang, R.H. , Aerts, A. , Arredondo, F.D. , Baxter, L. , Bensasson, D. and Beynon, J.L. (2006) Phytophthora genome sequences uncover evolutionary origins and mechanisms of pathogenesis. Science, 313, 1261–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van't Slot, K.A. and Knogge, W. (2002) A dual role for microbial pathogen‐derived effector proteins in plant disease and resistance. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 21, 229–271. [Google Scholar]

- Vetukuri, R.R. , Avrova, A.O. , Grenville‐Briggs, L.J. , Van West, P. , Söderbom, F. , Savenkov, E.I. , Whisson, S.C. and Dixelius, C. (2011) Evidence for involvement of Dicer‐like, Argonaute and histone deacetylase proteins in gene silencing in Phytophthora infestans . Mol. Plant. Pathol. 12, 772–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizcaíno, J.A. , Deutsch, E.W. , Wang, R. , Csordas, A. , Reisinger, F. , Ríos, D. , Dianes, J.A. , Sun, Z. , Farrah, T. , Bandeira, N. , Binz, P.A. , Xenarios, I. , Eisenacher, M. , Mayer, G. , Gatto, L. , Campos, A. , Chalkley, R.J. , Kraus, H.J. , Albar, J.P. , Martinez‐Bartolomé, S. , Apweiler, R. , Omenn, G.S. , Martens, L. , Jones, A.R. and Hermjakob, H. (2014) ProteomeXchange provides globally co‐ordinated proteomics data submission and dissemination. Nat. Biotechnol. 30, 223–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan, H.Z. and Liou, R.F. (2006) Selection of internal control genes for real‐time quantitative RT‐PCR assays in the oomycete plant pathogen Phytophthora parasitica . Fungal Genet. Biol. 43, 430–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S. and Fernald, R.D. (2005) Comprehensive algorithm for quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction. J. Comp. Biol. 12, 1047–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's website:

Table S1. List of unique proteins and their corresponding peptides obtained from in‐gel and solution (iTRAQ) proteomics analysis.

Table S2. List of oligonucleotide primer pairs used for reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) analysis.

Table S3. List of identified proteins involved in glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, the pentose phosphate pathway, the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) (or citric acid) cycle and the fatty acid degradation pathway.

Fig S1. Glycolysis/gluconeogenesis pathway. All of the proteins presented were identified by proteomics and the enzymes marked in red were found to be up‐regulated in the mycelium of Phytophthora capsici. These include fructose‐bisphosphate aldolase (Phyca11|507726), triose‐phosphate isomerase (TPI; Phyca11|506671), glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase (Phyca11|504523), phosphoglycerate kinase (Phyca11|510172) and enolase (Phyca11|503568).

Fig S2. Pentose phosphate pathway. The figure represents the enzymes that were identified by proteomics analysis. The proteins marked in red were found to be up‐regulated in the mycelium of Phytophthora capsici, including glucose‐6‐phosphate 1‐dehydrogenase (Phyca11|509625), transketolase (Phyca11|506857), transaldolase (Phyca11|505958) and 6‐phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (Phyca11|507227).

Fig S3. Tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (or citric acid cycle). All of the enzymes presented were identified in this work. Malate dehydrogenase (Phyca11|505882) and ATP‐citrate synthase (Phyca11|504894) were found to be up‐regulated in the mycelium of Phytophthora capsici (red).

Fig S4. Fatty acid degradation via the β‐oxidation pathway. All of the proteins presented were identified by proteomics analysis and assigned to the catabolism of fatty acid. The proteins up‐regulated in the cysts of Phytophthora capsici are shown in red and correspond to choline/carnitine O‐acyltransferase (Phyca11|118056), acyl‐CoA dehydrogenase (Phyca11|502783, Phyca11|529555), trifunctional enzyme subunit β (Phyca11|508178), trifunctional enzyme subunit α (Phyca11|506742) and 3‐ketoacyl‐CoA thiolase (Phyca11|534354).