Summary

Aspergillus flavus and Fusarium verticillioides are fungal pathogens that colonize maize kernels and produce the harmful mycotoxins aflatoxin and fumonisin, respectively. Management practice based on potential host resistance to reduce contamination by these mycotoxins has proven difficult, resulting in the need for a better understanding of the infection process by these fungi and the response of maize seeds to infection. In this study, we followed the colonization of seeds by histological methods and the transcriptional changes of two maize defence‐related genes in specific seed tissues by RNA in situ hybridization. Maize kernels were inoculated with either A. flavus or F. verticillioides 21–22 days after pollination, and harvested at 4, 12, 24, 48, 72, 96 and 120 h post‐inoculation. The fungi colonized all tissues of maize seed, but differed in their interactions with aleurone and germ tissues. RNA in situ hybridization showed the induction of the maize pathogenesis‐related protein, maize seed (PRms) gene in the aleurone and scutellum on infection by either fungus. Transcripts of the maize sucrose synthase‐encoding gene, shrunken‐1 (Sh1), were observed in the embryo of non‐infected kernels, but were induced on infection by each fungus in the aleurone and scutellum. By comparing histological and RNA in situ hybridization results from adjacent serial sections, we found that the transcripts of these two genes accumulated in tissue prior to the arrival of the advancing pathogens in the seeds. A knowledge of the patterns of colonization and tissue‐specific gene expression in response to these fungi will be helpful in the development of resistance.

Keywords: Aspergillus flavus, Fusarium verticillioides, histology, maize, PRms, RNA in situ hybridization, Sh1

Introduction

Maize (Zea mays L.), one of the most economically important and widely grown crops, is used for human food, livestock feed and alcohol production. Maize ear rots and mycotoxin contamination caused by Aspergillus flavus and Fusarium verticillioides are chronic problems in the USA and all over the world (Bush et al., 2004; CAST, 2003; Johansson et al., 2006; Munkvold, 2003; Payne, 1992; Woloshuk and Shim, 2013).

Aspergillus flavus is an opportunistic fungal pathogen (Payne, 1992) capable of infecting immature maize kernels under favourable conditions, which include high temperature and water stress (Diener et al., 1987; Horn et al., 2009; Jones et al., 1980; Payne, 1992; Payne et al., 1988; Widstrom et al., 2003b). This fungus can invade maize ears through the silk channel or other openings in the husks (Marsh and Payne, 1984). Once in the ear, the fungus colonizes kernel surfaces and enters kernels either through the pedicel region or through wounds created by insect or mechanical injury of the pericarp (Anderson et al., 1975; Hesseltine et al., 1976; Lee et al., 1980; Lillehoj et al., 1975; Payne, 1983; Smart et al., 1990; Widstrom et al., 2003a). Inside the kernel, the fungus can colonize all tissue types, with the most extensive colonization occurring in the germ (Dolezal et al., 2013; Fennell et al., 1973; Keller et al., 1994; Smart et al., 1990).

Unlike A. flavus, F. verticillioides can exist as an endophyte in maize plants, becoming pathogenic under conditions that are not completely understood (Bacon et al., 2008; Cao et al., 2013; Munkvold et al., 1997; Parsons and Munkvold, 2010a, b, 2012). This fungus enters the ear through the ear shank or silk channel of the ear, infects kernels and causes ear rots (Bacon et al., 2008; Duncan and Howard, 2010). Insect feeding and mechanical damage of the kernel also facilitate invasion of F. verticillioides (Koehler, 1942; Maiorano et al., 2009; Munkvold, 2003; Parsons and Munkvold, 2010a, b, 2012; Sobek and Munkvold, 1999; Warfield and Davis, 1996).

Genetic resistance to aflatoxin and fumonisin accumulation has been identified in maize breeding populations, but resistance is polygenic and subject to large gene × environment interactions. The lack of good markers for phenotyping further hampers the development of agronomically adapted maize genotypes with resistance to these diseases (Brown et al., 2013; Bryła et al., 2013; Eller et al., 2008; Moreno and Kang, 1999; Warburton et al., 2013; Warburton and Williams, 2014; Zila et al., 2013). Maize plants have evolved shared mechanisms to defend against ear rot fungi (Mideros et al., 2014), and Robertson‐Hoyt et al. (2007) showed, through marker assisted selection, that at least some of the genes associated with the plant defence response to A. flavus and F. verticillioides infection are genetically linked.

Proteomic and transcriptomic analyses have identified changes in protein production during the infection of maize seeds by A. flavus and F. verticillioides (Brown et al., 2013; Campos‐Bermudez et al., 2013; Dolezal et al., 2013, 2014; Lanubile et al., 2012). The biological activity of many of these proteins is unknown, but a few are known to have antifungal activity, or to be involved in host defence. These include pathogenesis‐related (PR) proteins, lipoxygenases, α‐amylase inhibitors, ribosome‐inactivating proteins (RIPs) and zeamatins (Bravo et al., 2003; Brown et al., 2010; Fakhoury and Woloshuk, 2001; Guo et al., 1997; Kelley et al., 2012; Lanubile et al., 2012; Moore et al., 2004; Murillo et al., 1999; Nielsen et al., 2001; Wilson et al., 2001; Zila et al., 2013).

To gain additional insights into the interaction between these two pathogens and maize kernels, we used histology to follow the colonization of developing maize kernels by each fungus from 4 to 120 h post‐inoculation (hpi). We compared the colonization of maize kernels by the two pathogens under the same field conditions. Concurrently, RNA in situ hybridization was used to monitor the temporal and spatial expression pattern of two maize genes, PRms (pathogenesis‐related protein, maize seed; accession number, X54325; gene id, AC205274.3_FG001) and sh1 (shrunken‐1; synonym, Sucrose‐UDP glucosyltransferase 1; accession number, NM_001279762; gene id, GRMZM2G089713). The two genes were selected to monitor the timing and localization of the host response to infection by the two pathogens. The expression of PRms, one of the better studied PR proteins in maize, was monitored as a marker for defence signalling in maize. Sh1 was selected because earlier studies had shown its expression to be induced in response to infection by A. flavus (Dolezal et al., 2014), and because changes in carbohydrate metabolism often occur in plants during pathogen attack (Berger et al., 2004; Botanga et al., 2012; Doehlemann et al., 2008; Dolezal et al., 2014; Göhre et al., 2012; Santi et al., 2013). Through the observation of fungal colonization and the expression of the two maize genes in serial histological sections of the maize kernels, we found PRms and Sh1 to be expressed in a tissue‐specific fashion before visible fungal colonization.

Results

Colonization of maize kernels by A . flavus and F . verticillioides

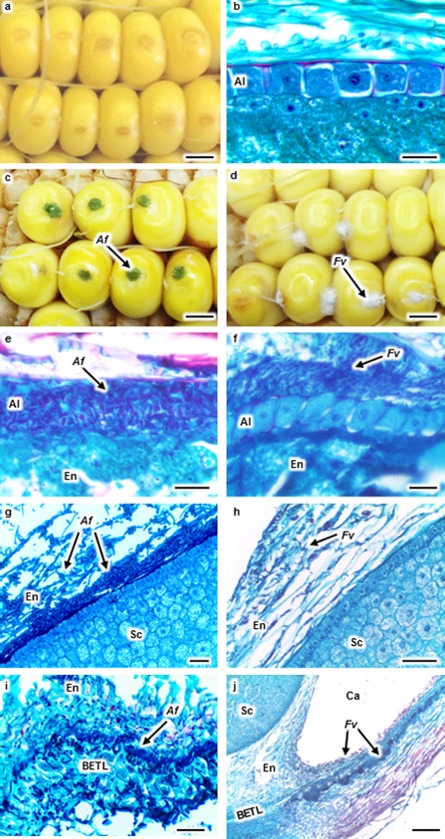

Maize kernels were mock inoculated (Fig. 1a) or inoculated with A. flavus or F. verticillioides by wounding with a needle (Fig. 1c,d). Kernels were collected at 4, 12, 24, 48, 72, 96 and 120 hpi. Figure 1e–j shows the location of A. flavus and F. verticillioides in maize kernels at 96 hpi. The localization of the fungi within the seeds at 48, 72 and 96 hpi is summarized by the schematic drawings in Fig. 2j–l. Initial colonization by these two fungi was observed in the aleurone and endosperm at the site of inoculation at 48 hpi (Figs 2j, S1a,b, see Supporting Information). Mycelia and conidia of A. flavus were observed in the aleurone, endosperm and germ at 72 hpi (Fig. 2k). In contrast, F. verticillioides was detected only in the aleurone and endosperm at 72 hpi (Fig. 2k). Both fungi were observed in all kernel tissues by 96 hpi (Fig. 2l).

Figure 1.

Aspergillus flavus (Af) and Fusarium verticillioides (Fv) colonization in maize kernels at 96 h post‐inoculation. Kernels were wound inoculated with Triton X‐100 (a), Af (c) or Fv (d). Kernel sections were stained with safranin and fast green (b and e–j). No fungal colonization was observed in the aleurone (Al) of a mock‐inoculated kernel (b). Af colonized and destroyed the Al (e), whereas Fv colonized around the intact Al (f). Af colonized at the endosperm (En)–scutellum (Sc) interface forming a biofilm‐like structure and creating cavities (Ca) in the En (g). Fv ramified through the En near the Sc (h). Af colonized in the basal endosperm transfer layer (BETL) (i). Fv colonized in the basal Al and En near the BETL and formed a Ca in the En (j). Arrows denote fungal colonization. Scale bars: (a, c, d) 3 mm; (b, e, f) 30 μm; (g–i) 50 μm; (j) 200 μm.

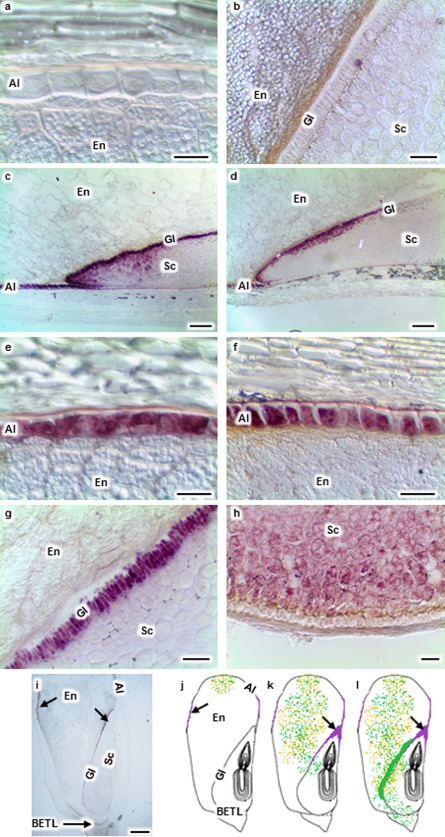

Figure 2.

Localization of pathogenesis‐related protein, maize seed (PRms) transcripts (purple signal) in maize kernels during Aspergillus flavus (Af) and Fusarium verticillioides (Fv) colonization. No PRms transcripts were observed in the aleurone (Al), endosperm (En) or scutellum (Sc) of mock‐inoculated kernels (a, b). PRms transcripts were localized in kernel sections at 96 h post‐inoculation (hpi; c–i). PRms transcripts were present in the Al, Sc tip and glandular layer (Gl) during both Af (c, i) and Fv (d) infection. PRms transcripts were observed in the Al (e) and Gl (g) during Af infection. PRms transcripts were observed in the Al (f) and Sc near the basal endosperm transfer layer (BETL; h) during Fv infection. (j‐l) Schematic drawings of longitudinal kernel sections showing colonization by Af (green dots) and Fv (orange dots), as well as the presence of PRms transcripts (purple signal) over time. At 48 hpi (j), Af and Fv colonized at the inoculation site; PRms transcripts were localized in the Al. At 72 hpi (k), Af colonized in the Al, En and Sc; Fv colonized only in the Al and En; PRms transcripts were localized in the Al, Sc tip and Gl. At 96 hpi (l), Af colonized in the Al, En, Sc, BETL and at the En–Sc interface with the formation of a biofilm‐like structure; Ff colonized in the Al, En and Sc; PRms transcripts were localized in the Al, Sc tip and Gl. Arrows denote the presence of PRms transcripts. Scale bars: (a, b, e–h) 30 μm; (c, d) 200 μm; (i) 1 mm.

Extensive disruption of the cytoplasm and nuclei was observed in the aleurone colonized by A. flavus (Fig. 1e), whereas many aleurone cells were either intact or only partially destroyed by F. verticillioides (Figs 1f, S1d). Only in the later stages of infection by F. verticillioides was substantial degradation of the aleurone observed (Fig. S1f). Both fungi extensively colonized and degraded tissues of the endosperm, creating cavities that often contained mycelia and conidia (Figs 1j, S1i,j). In some areas, these fungi were observed throughout the endosperm without obvious degradation of host tissue (Figs 1h, S1e,h).

In this study, little colonization was observed in the embryo tissue. At 96 hpi, both A. flavus and F. verticillioides colonization was observed in the scutellum of only a few kernels (Figs 2l, S1e,g). Instead, A. flavus often formed a biofilm‐like structure at the endosperm–scutellum interface (Figs 1g, S1e), as reported by Dolezal et al. (2013). In many cases, the biofilm‐like structure covered a large area of the scutellum without evidence of germ colonization (Fig. 1g). A similar biofilm‐like structure was not observed in F. verticillioides‐infected kernels (Fig. 1h). Rarely was A. flavus found in the tip of the scutellum, and this occurred only in those kernels with obvious damage to the germ (Fig. S1g).

Aspergillus flavus colonization of the basal endosperm transfer layer (BETL) was observed at 96 hpi (Fig. 1i). Fusarium verticillioides hyphae were not observed in the BETL, but were observed in the aleurone and endosperm near the BETL region at 96 hpi (Fig. 1j).

Tissue‐specific gene expression of PRms

RNA in situ hybridization was conducted to assess the timing and localization of host expression of PRms in response to the two pathogens. By 48 hpi, transcripts of PRms were observed in aleurone cells during A. flavus colonization of the seed, and were detected in the scutellum by 72 hpi (Fig. 2c,e,g). In F. verticillioides‐infected kernels, PRms transcripts were detected in the aleurone and scutellum at 48 hpi (Fig. 2f). In the scutellum, transcripts of this gene were predominantly detected at the tip and in the glandular layer (Fig. 2c,d,g). PRms transcripts were also observed within the scutellum (Fig. 2c,d). During F. verticillioides infection, PRms transcripts were often observed in the scutellum near the BETL (Fig. 2h). No PRms transcripts were observed in mock‐inoculated kernels (Fig. 2a,b) or kernels collected at 4, 12 and 24 hpi (data not shown). No PRms gene expression signal was observed in the sections hybridized with the control probe (Fig. 4c,f,i).

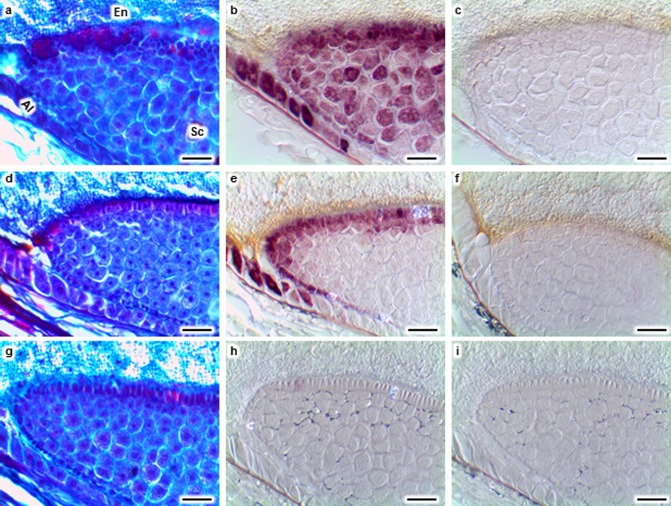

Figure 4.

Activation of pathogenesis‐related protein, maize seed (PRms) gene expression (purple signal) before visible colonization by Aspergillus flavus (Af) and Fusarium verticillioides (Fv) at 72 h post‐inoculation. Adjacent serial sections of an Af‐inoculated kernel were stained with safranin and fast green (a), hybridized with PRms probe (b) or control probes (c). PRms transcripts were detected in the aleurone (Al) and scutellum (Sc) tip of the kernel inoculated with Af (b). Adjacent serial sections of an Fv‐inoculated kernel were stained with safranin and fast green (d), hybridized with PRms probe (e) or control probes (f). PRms transcripts were detected in the aleurone and scutellum tip of the kernel inoculated with Fv (e). Adjacent serial sections of a mock‐inoculated kernel were stained with safranin and fast green (g), hybridized with PRms probe (h) or control probes (i). No PRms transcripts were detected in the mock‐inoculated kernel (h). No fungal colonization was detected in Af‐ (a), Fv‐ (d) or mock (g)‐inoculated kernels. No signal was observed in the sections hybridized with the control probes (c, f, i). Scale bars: 50 μm.

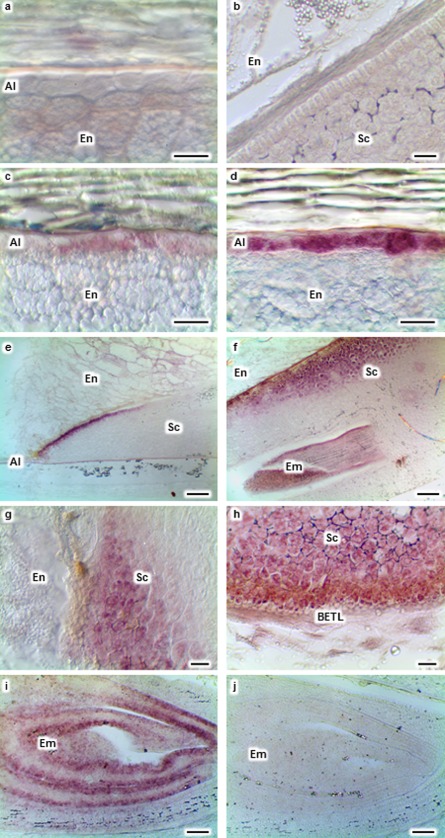

Tissue‐specific gene expression of Sh1

RNA in situ hybridization indicated that the expression of Sh1 was altered on infection by A. flavus and F. verticillioides. Sh1 transcripts were observed in some aleurone cells in response to A. flavus infection at 48 hpi (data not shown). At 72 and 96 hpi, Sh1 transcripts were detected in the aleurone and scutellum (Fig. 3c,e,g). However, during F. verticillioides infection, Sh1 transcripts were observed in the aleurone at 24 hpi (data not shown), before fungal colonization was observed in any tissue of the kernel. At 48, 72 and 96 hpi, this gene was expressed in the aleurone and scutellum (Fig. 3d,f). It was also expressed in the scutellum near the BETL region at 72 and 96 hpi (Fig. 3h). Transcripts of Sh1 were observed in the scutellum near the BETL during A. flavus infection at 120 hpi (data not shown). In both A. flavus and F. verticillioides kernels, Sh1 was often induced at the scutellum tip and in the glandular layer.

Figure 3.

Localization of shrunken‐1 (Sh1) transcripts (purple signal) in mock‐, Aspergillus flavus (Af)‐ and Fusarium verticillioides (Fv)‐inoculated maize kernels at 72 h post‐inoculation. No Sh1 transcripts were observed in the aleurone (Al), endosperm (En) or scutellum (Sc) of mock‐inoculated kernels (a, b). Sh1 transcripts were observed in the Al (c), outermost layer of Sc (e) and inner areas of Sc (g) during Af infection. Sh1 transcripts were detected in the Al (d), Sc and embryo (Em) (f), and Sc near the basal endosperm transfer layer (BETL; h), during Ff infection. Sh1 transcripts were observed in the Em of the mock‐inoculated kernel (i). No signal was observed in the Em of the mock‐inoculated kernel section hybridized with the control probe (j). Scale bars: (a–d, g, h) 30 μm; (e, f, i, j) 200 μm.

Unlike PRms, Sh1 transcripts were observed in the embryo of some mock‐inoculated (Fig. 3i) and non‐wounded kernels (data not shown). However, Sh1 was not expressed in the aleurone (Fig. 3a) and scutellum (Fig. 3b) of either mock‐inoculated or non‐wounded kernels. Likewise, no Sh1 signal was observed in the sections hybridized with the control probe (Fig. 3j). Thus, Sh1 was expressed in the embryo independent of fungal infection, but its expression in the aleurone and scutellum was induced on colonization of the kernel by each of these two fungi.

Tissue‐specific gene expression of PRms and Sh1 before fungal colonization

By comparing histological and RNA in situ hybridization results from adjacent serial sections, we observed both PRms (Fig. 4a–f) and Sh1 (data not shown) transcripts in tissues lacking visible fungal colonization. These results indicate that kernel tissue responds to fungal invasion in advance of visible fungal colonization. Co‐localization of the fungus with PRms and Sh1, as measured by in situ hybridization, was sometimes observed in scutellum tissue, but neither PRms nor Sh1 was detected in the aleurone cells colonized by either fungus.

Quantification of PRms and Sh1 gene expression

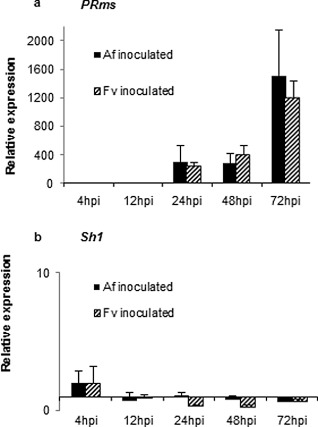

Gene expression levels of PRms and Sh1 were quantified by quantitative real‐time reverse transcriptase‐polymerase chain reaction (qRT‐PCR; Fig. 5). PRms transcripts were not detectable in non‐wounded kernels or in inoculated kernels collected at 4 and 12 hpi (Fig. 5a). However, both fungi activated the expression of this gene at 24, 48 and 72 hpi. Compared with the samples collected at 24 and 48 hpi, expression levels of PRms increased at 72 hpi on infection by both fungi. This finding agrees with the RNA in situ hybridization results. qRT‐PCR analysis showed no elevation of transcript accumulation of Sh1 during fungal infection (Fig. 5b).

Figure 5.

Quantitative real‐time reverse transcriptase‐polymerase chain reaction (qRT‐PCR) analysis of pathogenesis‐related protein, maize seed (PRms) (a) and shrunken‐1 (Sh1) (b) gene expression in maize kernels during infection by Aspergillus flavus (Af) and Fusarium verticillioides (Fv). Expression levels were normalized by the maize gene GRMZM2G024838 encoding the structural component of maize ribosomes, and were relative to the non‐wounded kernels. hpi, hours post‐inoculation.

Discussion

A spergillus flavus and F . verticillioides differ in their colonization of maize seed tissues

Aspergillus flavus and F. verticillioides, two ear rot pathogens exhibiting different tropic behaviour, differed in their pathogenesis of the aleurone and scutellum, two metabolically active tissues of maize seed. Aspergillus flavus rapidly colonized the aleurone and destroyed the structure of the cells. In the later stages of colonization, the cells collapsed and the resulting space was replaced by fungal mycelium (Figs 1e, S2c). In contrast, the aleurone cells colonized by F. verticillioides remained structurally intact during initial colonization (Fig. 1e,f). Some cells had visible mycelium of the fungus within the cells (Fig. S1d), but the cells of the aleurone did not collapse until later in the infection process. Others (Bacon et al., 2008; Duncan and Howard, (2010) have suggested that endophytic growth of F. verticillioides in the aleurone occurs only in non‐symptomatic maize kernels, whereas starburst symptoms and visible rot are associated with disease. Starburst symptoms on inoculated kernels were not observed in our studies as a consequence of infection by F. verticillioides, perhaps because of the stage of kernel maturity. Our observations suggest that extensive colonization of kernels by F. verticillioides can occur without visible macroscopic symptoms of rot. This supports the observations by Bush et al. (2004) which showed high concentrations of fumonisin in visibly sound kernels.

Although both fungi grew extensively in infected cells of the aleurone, this colonization was localized; the fungi began to preferentially colonize the endosperm rather than continuing to colonize the aleurone. This was surprising given the nutrient‐rich status of the aleurone (Bethke et al., 1998). Perhaps defence responses in the aleurone limit the growth of these fungi.

Aspergillus flavus also differed from F. verticillioides in the colonization of the scutellum. Aspergillus flavus mycelium was rarely observed within the scutellum before the formation of a biofilm‐like structure at the endosperm–scutellum interface (Fig. 1g), as reported by Dolezal et al. (2013). This specialized structure of A. flavus resembles the biofilm formed by A. fumigatus in the human lung (Loussert et al., 2010). It was not possible to determine from this study whether or not the structure is absolutely required for colonization of the germ, but the prevalence of this structure at the interface of the scutellum prior to infection argues that it may either be required for infection or needed for resistance to toxic compounds within, or secreted by, the scutellum. The scutellum is metabolically active and is known to secrete hydrolases and defence‐associated compounds (Guo et al., 1999). No such structure was observed during colonization by F. verticillioides.

We found no striking differences in the colonization of the endosperm by the two fungi. Both fungi were detected in the endosperm at the inoculation site at 48 hpi, and reached all tissues at 96 hpi (Fig. 1). Previous studies have shown that A. flavus is detected by PCR assays in the endosperm as early as 24 hpi and in the germ at 72 hpi (Dolezal et al., 2013); however, in our study, neither microscopic nor macroscopic fungal colonization was observed in inoculated kernels until 48 hpi.

A spergillus flavus and F . verticillioides induce tissue‐specific gene expression before visible fungal colonization

The staining of serial histological sections for visualization of fungal colonization or for RNA in situ hybridization allowed for the observation of fungal colonization and the expression of PRms and Sh1 in adjacent tissue sections during the colonization of maize kernels. We found PRms to be expressed in the aleurone and scutellum of infected kernels in advance of visible colonization by either fungus. Using cellular and subcellular immunolocalization, Murillo et al. (1999) also showed that the PRms protein accumulated in the aleurone and inner parenchyma cells of the scutellum of germinating maize seeds early after infection by F. verticillioides. Although they were able to visualize PRms accumulation in the scutellum at the site of infection by F. verticillioides, they did not report the accumulation of PRms in these tissues in advance of colonization. They did observe PRms localization in papillae in advance of colonization by F. verticillioides.

Similar to PRms, Sh1 was expressed in the aleurone and scutellum of infected seeds in advance of visible colonization by either fungus. Unlike PRms, Sh1 was expressed in the embryo of seeds independent of fungal colonization; Sh1 was also detected in the embryo of non‐wounded kernels and mock‐inoculated kernels. Using a histochemical enzyme assay to localize the Sh1 enzyme, Wittich and Vreugdenhil (1998) found maize Sh1 to be activated in the aleurone, endosperm and embryo during seed development. The differences observed between the two studies may be a result of differences in kernel maturity, detection techniques or the genotype of maize used.

Sh1 was expressed earlier in the aleurone in response to F. verticillioides than to A. flavus, even though there was more visible mycelium of A. flavus than of F. verticillioides. Moreover, Sh1 was detected earlier than PRms in the aleurone and scutellum near the BETL during F. verticillioides infection. Transcript accumulation of both PRms and Sh1 in response to the two fungi was highest at the tip of the scutellum. Colonization by these two fungi was rarely observed in the scutellum tip, perhaps because of an accumulation of these defence‐related compounds in this region.

Possible roles of maize PRms and Sh1 in response to A . flavus and F . verticillioides

Maize plants have complex regulatory networks that respond to pathogen attack (Brown et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2007; Denancé et al., 2013; Dolezal et al., 2014; Guo et al., 1999; Royo et al., 2006; Warburton et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2014). We have shown that A. flavus and F. verticillioides induce transcriptional changes in genes associated with the salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA) and ethylene (ET) defence signalling pathways (Dolezal et al., 2014; Shu, 2014). Also induced in response to infection are mRNAs encoding several PR proteins, including PRms. PRms expression is associated with increased resistance to several plant pathogens (Campos‐Soriano and San Segundo, 2009; Cordero et al., 1994; Gómez‐Ariza et al., 2007; Murillo et al., 2003). As an example, transgenic rice constitutively expressing PRms is more resistant to Magnaporthe oryzae, F. verticillioides, Helminthosporium oryzae and Erwinia chrysanthemi (Gómez‐Ariza et al., 2007).

Increased resistance associated with PRms appears to be mediated, in part, by the induction of host resistance priming (Campos‐Soriano and San Segundo, 2009; Cordero et al., 1994; Gómez‐Ariza et al., 2007; Murillo et al., 2003). Gómez‐Ariza et al. (2007) found that the PR genes OsPR1b, PBZ1 and Sci1 in rice were expressed earlier and to a greater level in plants with constitutive expression of PRms on infection by M. oryzae. The authors also found that rice plants transgenic for PRms accumulated higher levels of sucrose and showed increased resistance to M. oryzae (Gómez‐Ariza et al., 2007). Thus, PRms appears to act as a defence regulator to modulate resistance in maize plants (Gómez‐Ariza et al., 2007; Huffaker et al., 2011; Murillo et al., 2001). We also found PRms to be highly expressed in developing maize kernels in response to infection by A. flavus (Dolezal et al., 2014) and F. verticillioides (Shu, 2014). In our studies, we showed the induction of PRms in two tissues that are metabolically active during fungal colonization. Modulation of PRms or other defence compounds in these tissues could be part of a strategy for the control of these ear rot fungi.

Sh1 catalyses the reversible conversion of sucrose and uridine diphosphate (UDP) into fructose and UDP‐glucose (Xu et al., 1989). Fructose and UDP‐glucose are important substrates for various metabolic pathways, including cell wall synthesis and respiratory pathways (Delmer and Amor, 1995; Huber and Huber, 1996). Sh1 is not essential for sucrose synthesis in maize kernels (Cobb and Hannah, 1988), but overexpression of this gene results in elevated levels of starch (Jiang et al., 2013), indicating an important role of Sh1 in starch biosynthesis.

Sh1, whose expression increases during kernel development (Azama et al., 2003), is highly regulated in maize, and expressed in response to specific developmental and environmental stimuli, such as anaerobic stress (Clancy and Hannah, 2002; Hauptmann et al., 1988; Maas et al., 1991; McCarty et al., 1986; Vasil et al., 1989). Maize Sh1 is localized to both mitochondria and nuclei in maize seedlings (Subbaiah et al., 2007).

The role played by Sh1 in host defence is not yet clear. Infection of plants by several fungi causes changes in hexose partitioning and accumulation. Up‐regulation of Sh1 was observed in maize leaves on Ustilago maydis infection, and sucrose contents were increased slightly in this interaction (Doehlemann et al., 2008). Sh1 has also been associated with plant–microbe interactions in other plant species (Fraissinet‐Tachet et al., 1998; Langlois‐Meurinne et al., 2005; Ma et al., 2010; van de Mortel et al., 2012; O'Donnell et al., 1998; Poppenberger et al., 2003, 2006). The induction of Sh1 might enhance the sucrose metabolic pathway and provide substrates for the synthesis of defence compounds (Cobb and Hannah, 1988; Delmer and Amor, 1995; Huber and Huber, 1996). We have shown that A. flavus causes a shift in hexose metabolism away from starch synthesis and into other pathways of carbon metabolism, such as the shikimate and pentose phosphate pathways, two pathways that lead to the production of defence‐related compounds (Dolezal et al., 2014). These observations, together with the evidence that sucrose is involved in defence priming (Berger et al., 2004; Santi et al., 2013), argue that sugars play important roles in host defence.

Our studies show that A. flavus and F. verticillioides colonize tissues of maize kernels in a predictable pattern and establish relationships with the seed that would be expected for other well‐described necrotrophs. Further, these two fungi induce PRms, a characterized resistance‐associated protein, in the aleurone and scutellum in advance of visible fungal colonization. Taken together, these data argue that enhanced resistance to these fungi could be achieved by the manipulation of known pathways of host defence. The greatest challenge to the deployment of resistance genes will be the achievement of the expression of these genes during conditions of plant stress, which favour colonization and mycotoxin production by the two fungi.

Conclusion

Safranin and fast green staining of tissue sections, which allowed the sensitive detection of fungal mycelium and conidia within the maize seeds, coupled with RNA in situ hybridization, which has the ability to detect both rare and abundant transcripts, allowed us to monitor both the location and temporal pattern of host gene expression in relation to colonization by two important ear rot‐causing fungi of maize. Aspergillus flavus grew more quickly and caused more cell death in the early stages of colonization. Mycelium of F. verticillioides, but not that of A. flavus, was observed growing adjacent to intact aleurone cells. Further, infection of the scutellum by A. flavus was often preceded by the formation of a biofilm‐like structure and, in some cases, A. flavus was observed growing among intact cells of the scutellum. No specialized mycelial structures were observed for F. verticillioides.

Maize PRms and Sh1 genes were expressed in tissues before fungal mycelium was visible, indicating that tissues respond to infection before colonization. Expression of PRms was restricted to cells in the aleurone and scutellum, with the greatest expression in the outer layer of the scutellum and at the tip of the scutellum. Sh1 expression was also induced in cells of the aleurone and scutellum in response to infection. Unlike PRms, Sh1 was expressed in the embryo of non‐infected kernels. Both of these genes have been associated with resistance to plant diseases (Casacuberta et al., 1991, 1992; Dolezal, 2010; Gómez‐Ariza et al., 2007; Huffaker et al., 2011; Murillo et al., 1999, 2001) and may play a role in resistance to these fungi. No evidence was found that the host–parasite interactions involving these fungi differ appreciably from well‐characterized host–pathogen interactions. Thus, sustainable host resistance to the fungi should be possible.

Experimental Procedures

Plant and fungal materials

Maize inbred line B73 was grown at the Central Crops Research Station near Clayton, NC, USA. Maize ears were hand pollinated and covered with pollination bags. Fungal strains (A. flavus NRRL 3357, F. verticillioides n16) were grown on potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates at 28 °C for 5 days. Conidia were harvested from culture plates with sterile distilled water containing 0.05% (v/v) Triton X‐100 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The concentration of conidia was determined with a haemocytometer (Hausser Scientific, Horsham, PA, USA), and the conidial suspension was diluted to 1 × 106 conidia/mL for plant inoculations.

Fungal inoculation and tissue collection

Maize ears free of visible disease symptoms or insect damage were inoculated in the field at 21–22 days after pollination with either A. flavus or F. verticillioides. Kernels were wounded with a needle that had been dipped into a conidial suspension. Kernels for the mock treatment were inoculated with sterile distilled water containing 0.05% (v/v) Triton X‐100. Inoculated kernels were collected at 4, 12, 24, 48, 72, 96 and 120 hpi. Corresponding mock‐inoculated and non‐wounded kernels were collected at 4, 12, 24, 48, 72, 96 and 120 hpi and used as negative controls. Three ears were harvested for each treatment as biological replicates. Kernels for histology and RNA in situ hybridization studies were harvested and processed immediately. Kernels collected for RNA extraction and qRT‐PCR studies were frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately, and then stored at −80 °C.

Tissue fixation, dehydration and embedding

Kernels for histology and RNA in situ hybridization were collected in tissue‐embedding capsules (Fisher). Kernels were fixed, dehydrated and embedded in paraffin using a microwave oven (Pelco, Clovis, CA, USA) according to a protocol modified from Livingston et al. (2009, 2013; Table 1). The paraffin blocks were sectioned with an RM2255 microtome (Leica Microsystems, Wetzler, Germany). Ten‐micrometre‐thick sections were mounted on microscope slides (Gold Seal, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for histology staining. Adjacent 20‐μm sections were mounted on Probe microscope slides (Fisher) for RNA in situ hybridization. Slides were dried at 35 °C on a hot plate overnight and stored at room temperature.

Table 1.

Microwave fixation, dehydration and embedding steps to process maize kernels

| Step | Chemical medium | Time | Temperature (oC) | Wattage (watts) | Vacuum (Hg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixation | |||||

| Modified FAA* | 2 h | 35 | 650 | 20 | |

| Dehydration | |||||

| 70% flex | 30 min | 32 | 650 | 20 | |

| 80% flex | 30 min | 32 | 650 | 20 | |

| 95% flex | 30 min | 32 | 650 | 20 | |

| 100% flex | 30 min | 32 | 650 | 20 | |

| 100% flex | 30 min | 32 | 650 | 20 | |

| 1:1 (v/v) flex : xylene | 30 min | 32 | 650 | 20 | |

| 1:1 (v/v) flex : xylene | 30 min | 32 | 650 | 20 | |

| 100% xylene | 30 min | 32 | 650 | 20 | |

| 100% xylene | 30 min | 32 | 650 | 20 | |

| 1:1 (v/v) xylene : paraffin | 30 min | 65 | 650 | 20 | |

| 1:1 (v/v) xylene : paraffin | 30 min | 65 | 650 | 20 | |

| Embedding | |||||

| 100% paraffin | 1 h | 65 | 650 | 20 | |

| 100% paraffin | 1 h | 65 | 650 | 20 |

*Modified FAA fixative is 40% (v/v) distilled H2O, 45% (v/v) methanol, 10% (v/v) formaldehyde and 5% (v/v) glacial acetic acid.

Tissue staining

Kernel sections were stained with safranin and fast green to allow for the differentiation of maize and fungal tissues (Livingston et al., 2009, 2013; Table 2). Stained sections were mounted in Permount (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and covered with coverslips.

Table 2.

Safranin and fast green staining protocol for sections of maize kernels at room temperature

| Step | Chemical medium | Time |

|---|---|---|

| Paraffin removal | ||

| 100% xylene | 20 min | |

| Rehydration | ||

| 100% ethanol | 10 s | |

| 95% (v/v) ethanol | 10 s | |

| 70% (v/v) ethanol | 10 s | |

| 50% (v/v) ethanol | 10 s | |

| Staining | ||

| Safranin | 2 h | |

| Dehydration | 10 s | |

| 50% (v/v) ethanol | 10 s | |

| 70% (v/v) ethanol | 10 s | |

| 95% (v/v) ethanol | 10 s | |

| 100% ethanol | 10 s | |

| Counterstaining | ||

| Fast green | 1 min | |

| Post‐staining | ||

| 100% xylene | 1 min |

RNA extraction and probe cloning

Eight kernels from individual ears were pooled and ground in liquid nitrogen with a mortar and pestle. Ground tissue was added to 0.75 mL of tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (Tris)‐saturated phenol, pH 6.6 (Fisher), and homogenized for 2 min. Samples were then dissolved in Tris‐ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (Tris‐EDTA, Thermo Fisher Scientific) buffer, pH 8.0 (ACROS Organics, Thermo Fisher Scientific), extracted with 5:1 (v/v) acid phenol : chloroform, pH 4.5 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and precipitated with ice‐cold 100% ethanol (ACROS Organics) overnight. Total RNA was further purified with an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The quantity and quality of RNA were analysed using an ND‐1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). RNA was treated with DNase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), and cDNA synthesis was performed using the first‐strand cDNA synthesis kit (Fermentas, Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RT‐PCR was conducted with PRms‐1 and Sh1 primer sets to amplify PRms and Sh1 probe sequences, respectively (Table 3). cDNA from A. flavus‐inoculated kernels collected at 96 hpi was used to amplify PRms and Sh1 probe sequences. RT‐PCR was performed using Ex Taq (Chemicon, Otsu, Shiga, Japan). The conditions used for RT‐PCR were as follows: 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 45 s and 72 °C for 1 min 30 s, and then followed by a final extension step performed at 72 °C for 7 min. The PCR products were resolved through a 0.8% (w/v) agarose gel and cleaned using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen). The purified PRms and Sh1 PCR products were inserted into the dual promoter vector PCR®II‐TOPO® (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's protocol, and sequenced. The vectors carrying PRms and Sh1 probe sequences were linearized by the restriction enzymes NcoI and ApaLI, respectively. The antisense and sense (control) probes were transcribed from the linearized vectors using the Riboprobe® System‐SP6 and ‐T7 transcription kits (Promega) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Table 3.

Primers used in this study

| Gene (gene id) | Primer usage | Primers 5′–3′ |

|---|---|---|

| PRms (AC205274.3_FG001) | Probe | PRms‐1F: TACAATGGAGGCATCCAACA |

| PRms‐1R: CATTGATCGCAGGCACAAT | ||

| qRT‐PCR | PRms‐2F: TACAATGGAGGCATCCAACA | |

| PRms‐2R: CTGTTTTGGGGAGTGAGGTA | ||

| Sh1 (GRMZM2G089713) | Probe | Sh1‐1F: TGGAGTAGCCTGCGTTCTACG |

| Sh1‐1R: TGCAGCCAATTCTCACCAT | ||

| qRT‐PCR | Sh1‐2F: GGAGTAGCCTGCGTTCTACG | |

| Sh1‐2R: GTCAATGTGCAGGCCAGATA | ||

| Ribosome structural component gene (GRMZM2G024838) | qRT‐PCR | Rib‐F: GGCTTGGCTTAAAGGAAGGT |

| Rib‐R: TCAGTCCAACTTCCAGAATGG |

RNA in situ hybridization

RNA in situ hybridization was carried out according to previously described protocols (Franks et al., 2002; Lincoln et al., 1994; Long and Barton, 1998). The hybridization temperature was 65 °C. The sense probes of each gene were included as negative controls. Mock‐inoculated kernels were hybridized with both antisense and sense probes as biological controls.

Microscopy

Images of sections stained with safranin and fast green, as well as sections hybridized with RNA probes, were collected on an Eclipse E600 light microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan), captured on an Infinity1‐3C digital camera and analysed with Infinity Analyze imaging software (Lumenera, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada).

qRT‐PCR expression analysis

cDNAs from either A. flavus‐ or F. verticillioides‐inoculated kernels collected at 4, 12, 24, 48 and 72 hpi were used for qRT‐PCR studies. The primers used for qRT‐PCR are listed in Table 3. qRT‐PCR was performed using a SYBR® Green kit (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The conditions used for qRT‐PCR were as follows: 96 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 96 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 30 s, plate read, 78 °C for 20 s, plate read, and then followed by a final extension step performed at 72 °C for 10 min. The expression levels of GRMZM2G024838, a structural component of maize ribosomes, were used for normalization. Data were analysed by the comparative C T method with the amount of target given by the calibrator 2–ΔΔCT (Schmittgen and Livak, 2008).

Supporting information

Fig. S1 Aspergillus flavus (Af) and Fusarium verticillioides (Fv) colonization in maize kernels. Kernel sections were stained with safranin and fast green. Af (a) and Fv (b) colonized at the inoculation site at 48 h post‐inoculation (hpi). Af typically colonized and destroyed the aleurone (Al) (c), whereas Fv often colonized in the intact Al (d) and destroyed the Al at a later infection stage (f). Af colonized at the endosperm (En)–scutellum (Sc) interface forming a biofilm‐like structure and colonizing the Sc (e). Af colonized the Sc tip of a kernel with obvious damage to the germ (g). Fv colonized the En (h). Af (i) and Fv (j) colonized the En, creating cavities (Ca) in the En (j). Arrows denote fungal colonization. Scale bars: (a, b, g, h) 200 μm; (c, d, f, j) 30 μm; (e, i) 50 μm.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the United States Department of Agriculture, National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) (award number: 2010‐65108‐20496) for financial support. We thank Mr Gregory R. OBrian and Tan Tuong for their invaluable technical help and advice on the manuscript.

References

- Anderson, H.W. , Nehring, E.W. and Wichser, W.R. (1975) Aflatoxin contamination of corn in the field. Food Chem. 23, 775–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azama, K. , Abe, S. , Sugimoto, H. and Davies, E. (2003) Lysine‐containing proteins in maize endosperm: a major contribution from cytoskeleton‐associated carbohydrate‐metabolizing enzymes. Planta, 217, 628–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacon, C.W. , Glenn, A.E. and Yates, I.E. (2008) Fusarium verticillioides: managing the endophytic association with maize for reduced fumonisins accumulation. Toxin Rev. 27, 411–446. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, S. , Papadopoulos, M. , Schreiber, U. , Kaiser, W. and Roitsch, T. (2004) Complex regulation of gene expression, photosynthesis and sugar levels by pathogen infection in tomato. Physiol. Plant. 122, 419–428. [Google Scholar]

- Bethke, P.C. , Swanson, S.J. , Hillmer, S. and Jones, R.L. (1998) From storage compartment to lytic organelle: the metamorphosis of the aleurone protein storage vacuole. Ann. Bot. (Lond.) 82, 399–412. [Google Scholar]

- Botanga, C.J. , Bethke, G. , Chen, Z. , Gallie, D.R. , Fiehn, O. and Glazebrook, J. (2012) Metabolite profiling of Arabidopsis inoculated with Alternaria brassicicola reveals that ascorbate reduces disease severity. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 25, 1628–1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo, J.M. , Campo, S. , Murillo, I. , Coca, M. and San Segundo, B. (2003) Fungus‐ and wound‐induced accumulation of mRNA containing a class II chitinase of the pathogenesis‐related protein 4 (PR‐4) family of maize. Plant Mol. Biol. 52, 745–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R.L. , Chen, Z.Y. , Warburton, M. , Luo, M. , Menkir, A. , Fakhoury, A. and Bhatnagar, D. (2010) Discovery and characterization of proteins associated with aflatoxin‐resistance: evaluating their potential as breeding markers. Toxins (Basel), 2, 919–933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R.L. , Menkir, A. , Chen, Z.Y. , Bhatnagar, D. , Yu, J. , Yao, H. , Yu, J. , Yao, H. and Cleveland, T.E. (2013) Breeding aflatoxin‐resistant maize lines using recent advances in technologies—a review. Food Addit. Contam. A, 30, 1382–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryła, M. , Roszko, M. , Szymczyk, K. , Jędrzejczak, R. , Obiedziński, M.W. and Sękul, J. (2013) Fumonisins in plant‐origin food and fodder—a review. Food Addit. Contam. A, 30, 1626–1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush, B.J. , Carson, M.L. , Cubeta, M.A. , Hagler, W.M. and Payne, G.A. (2004) Infection and fumonisin production by Fusarium verticillioides in developing maize kernels. Phytopathology, 94, 88–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos‐Bermudez, V.A. , Fauguel, C.M. , Tronconi, M.A. , Casati, P. , Presello, D.A. and Andreo, C.S. (2013) Transcriptional and metabolic changes associated to the infection by Fusarium verticillioides in maize inbreds with contrasting ear rot resistance. PLoS ONE, 8, e61580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos‐Soriano, L. and San Segundo, B. (2009) Assessment of blast disease resistance in transgenic PRms rice using a gfp‐expressing Magnaporthe oryzae strain. Plant Pathol. 58, 677–689. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, A. , Santiago, R. , Ramos, A.J. , MarÃn, S. , Reid, L.M. and Butrón, A. (2013) Environmental factors related to fungal infection and fumonisin accumulation during the development and drying of white maize kernels. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 164, 15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casacuberta, J.M. , Puigdomenech, P. and San Segundo, B. (1991) A gene coding for a basic pathogenesis‐related (PR‐like) protein from Zea mays. Molecular cloning and induction by a fungus (Fusarium moniliforme) in germinating maize seeds. Plant Mol. Biol. 16, 527–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casacuberta, J.M. , Raventos, D. , Puigdomenech, P. and San Segundo, B. (1992) Expression of the gene encoding the PR‐like protein PRms in germinating maize embryos. Mol. Genet. Genomics, 234, 97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Council for Agricultural Sciences and Technology (2003) Mycotoxins: risks in plant, animal, and human systems. Potential Economic Costs of Mycotoxins in the United States, Cast Task Force Report No. 139, Ames, IA January, pp. 136–142.

- Chen, Z.Y. , Brown, R.L. , Damann, K.E. and Cleveland, T.E. (2007) Identification of maize kernel endosperm proteins associated with resistance to aflatoxin contamination by Aspergillus flavus . Phytopathology, 97, 1094–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy, M. and Hannah, L.C. (2002) Splicing of the maize Sh1 first intron is essential for enhancement of gene expression, and a T‐rich motif increases expression without affecting splicing. Plant Physiol. 130, 918–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb, B.G. and Hannah, L.C. (1988) Shrunken‐1 encoded sucrose synthase is not required for sucrose synthesis in the maize endosperm. Plant Physiol. 88, 1219–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordero, M.J. , Raventos, D. and San Segundo, B. (1994) Expression of a maize proteinase inhibitor gene is induced in response to wounding and fungal infection: systemic wound‐response of a monocot gene. Plant J. 6, 141–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmer, D.P. and Amor, Y. (1995) Cellulose biosynthesis. Plant Cell, 7, 987–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denancé, N. , Sánchez‐Vallet, A. , Goffner, D. and Molina, A. (2013) Disease resistance or growth: the role of plant hormones in balancing immune responses and fitness costs. Front. Plant Sci. 4, 155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener, U.L. , Cole, R.J. , Sanders, T.H. , Payne, G.A. , Lee, L.S. and Klich, M.A. (1987) Epidemiology of aflatoxin formation by Aspergillus flavus . Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 25, 249–270. [Google Scholar]

- Doehlemann, G. , Wahl, R. , Horst, R.J. , Voll, L.M. , Usadel, B. , Poree, F. , Stitt, M. , Pons‐Kuhnemann, J. , Sonnewald, U. , Kahmann, R. and Kamper, J. (2008) Reprogramming a maize plant: transcriptional and metabolic changes induced by the fungal biotroph Ustilago maydis . Plant J. 56, 181–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolezal, A.L. (2010) Interactions between Aspergillus flavus and the developing maize kernel. PhD Thesis. Raleigh, NC: North Carolina State University. [Google Scholar]

- Dolezal, A.L. , OBrian, G.R. , Nielsen, D.M. , Woloshuk, C.P. , Boston, R.S. and Payne, G.A. (2013) Localization, morphology and transcriptional profile of Aspergillus flavus during seed colonization. Mol. Plant Pathol. 14, 898–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolezal, A.L. , Shu, X. , OBrian, G.R. , Nielsen, D.M. , Woloshuk, C.P. , Boston, R.S. and Payne, G.A. (2014) Aspergillus flavus infection induces transcriptional and physical changes in developing maize kernels. Front. Microbiol. 5, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, K.E. and Howard, R.J. (2010) Biology of maize kernel infection by Fusarium verticillioides . Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 23, 6–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eller, M.S. , Robertson‐Hoyt, L.A. , Payne, G.A. and Holland, J.B. (2008) Grain yield and Fusarium ear rot of maize hybrids developed from lines with varying levels of resistance. Maydica, 53, 231–237. [Google Scholar]

- Fakhoury, A.M. and Woloshuk, C.P. (2001) Inhibition of growth of Aspergillus flavus and fungal alpha‐amylases by a lectin‐like protein from Lablab purpureus . Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 14, 955–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fennell, D. , Bothast, R. , Lillehoj, E. and Peterson, R. (1973) Bright greenish‐yellow fluorescence and associated fungi in white corn naturally contaminated with aflatoxin. Cereal Chem. 50, 404–413. [Google Scholar]

- Fraissinet‐Tachet, L. , Baltz, R. , Chong, J. , Kauffmann, S. , Fritig, B. and Saindrenan, P. (1998) Two tobacco genes induced by infection, elicitor and salicylic acid encode glucosyltransferases acting on phenylpropanoids and benzoic acid derivatives, including salicylic acid. FEBS Lett. 437, 319–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks, R.G. , Wang, C. , Levin, J.Z. and Liu, Z. (2002) SEUSS, a member of a novel family of plant regulatory proteins, represses floral homeotic gene expression with LEUNIG. Development, 129, 253–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göhre, V. , Jones, A.M.E. , Sklenář, J. , Robatzek, S. and Weber, A.P.M. (2012) Molecular crosstalk between PAMP‐triggered immunity and photosynthesis. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 25, 1083–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez‐Ariza, J. , Campo, S. , Rufat, M. , Estopà, M. , Messeguer, J. , San Segundo, B. and Coca, M. (2007) Sucrose‐mediated priming of plant defense responses and broad‐spectrum disease resistance by overexpression of the maize pathogenesis‐related PRms protein in rice plants. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 20, 832–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, B.Z. , Chen, Z.Y. , Brown, R.L. , Lax, A.R. , Cleveland, T.E. , Russin, J.S. , Mehta, A.D. , Selitrennikoff, C.P. and Widstrom, N.W. (1997) Germination induces accumulation of specific proteins and antifungal activities in corn kernels. Phytopathology, 87, 1174–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, B.Z. , Cleveland, T.E. , Brown, R.L. , Widstrom, N.W. , Lynch, R.E. and Russin, J.S. (1999) Distribution of antifungal proteins in maize kernel tissues using immunochemistry. J. Food Prot. 62, 295–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauptmann, R.M. , Ashraf, M. , Vasil, V. , Hannah, L.C. , Vasil, I.K. and Ferl, R. (1988) Promoter strength comparisons of maize shrunken 1 and alcohol dehydrogenase 1 and 2 promoters in mono‐ and dicotyledonous species. Plant Physiol. 88, 1063–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesseltine, C.W. , Shotwell, O.L. , Kwolek, W.F. , Lillehoj, E.B. , Jackson, W.K. and Bothast, R.J. (1976) Aflatoxin occurrence in 1973 corn at harvest. Mycologia, 68, 341–353. [Google Scholar]

- Horn, B.W. , Moore, G.G. and Carbone, I. (2009) Sexual reproduction in Aspergillus flavus . Mycologia, 101, 423–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber, S.C. and Huber, J.L. (1996) Role and regulation of sucrose‐phosphate synthase in higher plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 47, 431–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffaker, A. , Dafoe, N.J. and Schmelz, E.A. (2011) ZmPep1, an ortholog of Arabidopsis elicitor peptide 1, regulates maize innate immunity and enhances disease resistance. Plant Physiol. 155, 1325–1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L. , Yu, X. , Qi, X. , Yu, Q. , Deng, S. , Bai, B. , Li, N. , Zhang, A. , Zhu, C. , Liu, B. and Pang, J. (2013) Multigene engineering of starch biosynthesis in maize endosperm increases the total starch content and the proportion of amylose. Transgenic Res. 22, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, A.S. , Whitaker, T.B. , Hagler, W.M., Jr , Bowman, D.T. , Slate, A.B. and Payne, G. (2006) Predicting aflatoxin and fumonisin in shelled corn lots using poor‐quality grade components. J. AOAC Int. 89, 433–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, R.K. , Duncan, H.E. , Payne, G.A. and Leonard, K.J. (1980) Factors influencing infection by Aspergillus flavus in silk‐inoculated corn. Plant Dis. 64, 859–863. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, N.P. , Butchko, R. , Sarr, B. and Phillips, T.D. (1994) A visual pattern of mycotoxin production in maize kernels by Aspergillus spp. Phytopathology, 84, 483–488. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, R.Y. , Williams, W.P. , Mylroie, J.E. , Boykin, D.L. , Harper, J.W. , Windham, G.L. , Ankala, A. and Shan, X. (2012) Identification of maize genes associated with host plant resistance or susceptibility to Aspergillus flavus infection and aflatoxin accumulation. PLoS ONE, 7, e36892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehler, B. (1942) Natural mode of entrance of fungi into corn ears and some symptoms that indicate infection. J. Agric. Res. 64, 421–442. [Google Scholar]

- Langlois‐Meurinne, M. , Gachon, C.M. and Saindrenan, P. (2005) Pathogen‐responsive expression of glycosyltransferase genes UGT73B3 and UGT73B5 is necessary for resistance to Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 139, 1890–1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanubile, A. , Bernardi, J. , Marocco, A. , Logrieco, A. and Paciolla, C. (2012) Differential activation of defense genes and enzymes in maize genotypes with contrasting levels of resistance to Fusarium verticillioides . Environ. Exp. Bot. 78, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, L.S. , Lillehoj, E.B. and Kwolek, W.F. (1980) Aflatoxin distribution in individual corn kernels from intact ears. Cereal Chem. 57, 340–343. [Google Scholar]

- Lillehoj, E.B. , Kwolek, W.F. , Fennell, D.I. and Milburn, M.S. (1975) Aflatoxin incidence and association with bright greenish‐yellow fluorescence and insect damage in a limited survey of freshly harvested high‐moisture corn. Cereal Chem. 52, 403–411. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, C. , Long, J. , Yamaguchi, J. , Serikawa, K. and Hake, S. (1994) A knotted1‐like homeobox gene in Arabidopsis is expressed in the vegetative meristem and dramatically alters leaf morphology when overexpressed in transgenic plants. Plant Cell, 6, 1859–1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston, D.P. , Tuong, T.D. , Haigler, C.H. , Avci, U. and Tallury, S.P. (2009) Rapid microwave processing of winter cereals for histology allows identification of separate zones of freezing injury in the crown. Crop Sci. 49, 1837–1842. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston, D.P. , Henson, C.A. , Tuong, T.D. , Wise, M.L. , Tallury, S.P. and Duke, S.H. (2013) Histological analysis and 3D reconstruction of winter cereal crowns recovering from freezing: a unique response in oat (Avena sativa L.). PLoS ONE, 8, e53468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long, J.A. and Barton, M.K. (1998) The development of apical embryonic pattern in Arabidopsis . Development, 125, 3027–3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loussert, C. , Schmitt, C. , Prevost, M.C. , Balloy, V. , Fadel, E. , Philippe, B. , Kauffmann‐Lacroix, C. , Latgé, J.P. and Beauvais, A. (2010) In vivo biofilm composition of Aspergillus fumigatus . Cell. Microbiol. 12, 405–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L. , Shang, Y. , Cao, A. , Qi, Z. , Xing, L. , Chen, P. , Liu, D. and Wang, X. (2010) Molecular cloning and characterization of an up‐regulated UDP‐glucosyltransferase gene induced by DON from Triticum aestivum L. cv. Wangshuibai. Mol. Biol. Rep. 37, 785–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas, C. , Laufs, J. , Grant, S. , Korfhage, C. and Werr, W. (1991) The combination of a novel stimulatory element in the first exon of the maize Shrunken‐1 gene with the following intron 1 enhances reporter gene expression up to 1000‐fold. Plant Mol. Biol. 16, 199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiorano, A. , Reyneri, A. , Sacco, D. , Magni, A. and Ramponi, C. (2009) A dynamic risk assessment model (FUMAgrain) of fumonisin synthesis by Fusarium verticillioides in maize grain in Italy. Crop Prot. 28, 243–256. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, S. and Payne, G. (1984) Preharvest infection of corn silks and kernels by Aspergillus flavus . Phytopathology, 74, 1284–1289. [Google Scholar]

- McCarty, D.R. , Shaw, J.R. and Hannah, L.C. (1986) The cloning, genetic mapping, and expression of the constitutive sucrose synthase locus of maize. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 83, 9099–9103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mideros, S.X. , Warburton, M.L. , Jamann, T.M. , Windham, G.L. , Williams, W.P. and Nelson, R.J. (2014) Quantitative trait loci influencing mycotoxin contamination of maize: analysis by linkage mapping, characterization of near‐isogenic lines, and meta‐analysis. Crop Sci. 54, 127–142. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, K.G. , Price, M.S. , Boston, R.S. , Weissinger, A.K. and Payne, G.A. (2004) A chitinase from Tex6 maize kernels inhibits growth of Aspergillus flavus . Phytopathology, 94, 82–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, O.J. and Kang, M.S. (1999) Aflatoxins in maize: the problem and genetic solutions. Plant Breed. 118, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- van de Mortel, J.E. , de Vos, R.C. , Dekkers, E. , Pineda, A. , Guillod, L. , Bouwmeester, K. , van Loon, J.J. , Dicke, M. and Raaijmakers, J.M. (2012) Metabolic and transcriptomic changes induced in Arabidopsis by the rhizobacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens SS101. Plant Physiol. 160, 2173–2188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munkvold, G.P. (2003) Cultural and genetic approaches managing mycotoxins in maize. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 41, 99–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munkvold, G.P. , McGee, D.C. and Carlton, W.M. (1997) Importance of different pathways for maize kernel infection by Fusarium moniliforme . Phytopathology, 87, 209–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murillo, I. , Cavallarin, L. and Segundo, B.S. (1999) Cytology of infection of maize seedlings by Fusarium moniliforme and immunolocalization of the pathogenesis‐related PRms protein. Phytopathology, 89, 737–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murillo, I. , Jaeck, E. , Cordero, M.J. and San Segundo, B. (2001) Transcriptional activation of a maize calcium‐dependent protein kinase gene in response to fungal elicitors and infection. Plant Mol. Biol. 45, 145–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murillo, I. , Roca, R. , Bortolotti, C. and Segundo, B.S. (2003) Engineering photoassimilate partitioning in tobacco plants improves growth and productivity and provides pathogen resistance. Plant J. 36, 330–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, K. , Payne, G.A. and Boston, R.S. (2001) Maize ribosome‐inactivating protein inhibits normal development of Aspergillus nidulans and Aspergillus flavus . Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 14, 164–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell, P.J. , Truesdale, M.R. , Calvert, C.M. , Dorans, A. , Roberts, M.R. and Bowles, D.J. (1998) A novel tomato gene that rapidly responds to wound‐ and pathogen‐related signals. Plant J. 14, 137–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, M.W. and Munkvold, G.P. (2010a) Associations of planting date, drought stress, and insects with Fusarium ear rot and fumonisin B1 contamination in California maize. Food Addit. Contam A , 27, 591–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, M.W. and Munkvold, G.P. (2010b) Relationships of immature and adult thrips with silk‐cut, fusarium ear rot and fumonisin B1 contamination of maize in California and Hawaii. Plant Pathol. 59, 1099–1106. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, M.W. and Munkvold, G.P. (2012) Effects of planting date and environmental factors on fusarium ear rot symptoms and fumonisin B1 accumulation in maize grown in six North American locations. Plant Pathol. 61, 1130–1142. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, G. , Thompson, D. , Lillehoj, E. , Zuber, M. and Adkins, C. (1988) Effect of temperature on the preharvest infection of maize kernels by Aspergillus flavus . Phytopathology, 78, 1376–1380. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, G.A. (1983) Nature of field infection of corn by Aspergillus flavus In: Aflatoxin and Aspergillus flavus in Corn, Southern Cooperative Series Bulletin, 279 (Diener U.L., Asquith R.L. and Dickens J.W., eds), pp. 16–19. Auburn, AL: Auburn University. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, G.A. (1992) Aflatoxin in maize. CRC Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 10, 423–440. [Google Scholar]

- Poppenberger, B. , Berthiller, F. , Lucyshyn, D. , Sieberer, T. , Schuhmacher, R. , Krska, R. , Kuchler, K. , Glossl, J. , Luschnig, C. and Adam, G. (2003) Detoxification of the Fusarium mycotoxin deoxynivalenol by a UDP‐glucosyltransferase from Arabidopsis thaliana . J. Biol. Chem. 278, 47 905–47 914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poppenberger, B. , Berthiller, F. , Bachmann, H. , Lucyshyn, D. , Peterbauer, C. , Mitterbauer, R. , Schuhmacher, R. , Krska, R. , Glössl, J. and Adam, G. (2006) Heterologous expression of Arabidopsis UDP‐glucosyltransferases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae for production of zearalenone‐4‐O‐glucoside. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 4404–4410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson‐Hoyt, L.A. , Betran, J. , Payne, G.A. , White, D.G. , Isakeit, T. , Maragos, C.M. , Molnar, T.L. and Holland, J.B. (2007) Relationships among resistances to Fusarium and Aspergillus ear rots and contamination by fumonisin and aflatoxin in maize. Phytopathology, 97, 311–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royo, J. , Gomez, E. , Balandin, M. , Muniz, L.M. and Hueros, G. (2006) ZmLrk‐1, a receptor‐like kinase induced by fungal infection in germinating seeds. Planta, 223, 1303–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santi, S. , De Marco, F. , Polizzotto, R. , Grisan, S. and Musetti, R. (2013) Recovery from stolbur disease in grapevine involves changes in sugar transport and metabolism. Front. Plant Sci. 4, 171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen, T.D. and Livak, K.J. (2008) Analyzing real‐time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat. Protoc. 3, 1101–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu, X. (2014) Pathogenesis and host response during infection of maize kernels by Aspergillus flavus and Fusarium verticillioides . PhD Thesis. Raleigh, NC: North Carolina State University. [Google Scholar]

- Smart, M.G. , Wicklow, D.T. and Caldwell, R.W. (1990) Pathogenesis in Aspergillus ear rot of maize: light microscopy of fungal spread from wounds. Phytopathology, 80, 1287–1294. [Google Scholar]

- Sobek, E.A. and Munkvold, G.P. (1999) European corn borer (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) larvae as vectors of Fusarium moniliforme, causing kernel rot and symptomless infection of maize kernels. J. Econ. Entomol. 92, 503–509. [Google Scholar]

- Subbaiah, C.C. , Huber, S.C. , Sachs, M.M. and Rhoads, D. (2007) Sucrose synthase: expanding protein function. Plant Signal. Behav. 2, 28–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasil, V. , Clancy, M. , Ferl, R.J. , Vasil, I.K. and Hannah, L.C. (1989) Increased gene expression by the first intron of maize shrunken‐1 locus in grass species. Plant Physiol. 91, 1575–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton, M.L. and Williams, W.P. (2014) Aflatoxin resistance in maize: what have we learned lately? Adv. Bot. 2014, 352831. doi: 10.1155/2014/35283110.1155/2014/352831 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton, M.L. , Williams, W.P. , Windham, G.L. , Murray, S.C. , Xu, W. , Hawkins, L.K. and Duran, J.F. (2013) Phenotypic and genetic characterization of a maize association mapping panel developed for the identification of new sources of resistance to Aspergillus flavus and aflatoxin accumulation. Crop Sci. 53, 2374–2383. [Google Scholar]

- Warfield, C.Y. and Davis, R.M. (1996) Importance of the husk covering on the susceptibility of corn hybrids to Fusarium ear rot. Plant Dis. 80, 208–210. [Google Scholar]

- Widstrom, N.W. , Butron, A. , Guo, B.Z. , Wilson, D.M. , Snook, M.E. , Cleveland, T.E. and Lynch, R.E. (2003a) Control of preharvest aflatoxin contamination in maize by pyramiding QTL involved in resistance to ear‐feeding insects and invasion by Aspergillus spp. Eur. J. Agron. 19, 563–572. [Google Scholar]

- Widstrom, N.W. , Guo, B.Z. and Wilson, D.M. (2003b) Integration of crop management and genetics for control of preharvest aflatoxin contamination of corn. Toxin Rev. 22, 199–227. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, R.A. , Gardner, H.W. and Keller, N.P. (2001) Cultivar‐dependent expression of a maize lipoxygenase responsive to seed infesting fungi. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 14, 980–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittich, P.E. and Vreugdenhil, D. (1998) Localization of sucrose synthase activity in developing maize kernels by in situ enzyme histochemistry. J. Exp. Bot. 49, 1163–1171. [Google Scholar]

- Woloshuk, C.P. and Shim, W.B. (2013) Aflatoxins, fumonisins, and trichothecenes: a convergence of knowledge. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 37, 94–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L. , Chen, H. , Curtis, C. and Fu, Z.Q. (2014) Go in for the kill: how plants deploy effector‐triggered immunity to combat pathogens. Virulence, 5, 710–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.P. , Sung, S.J. , Loboda, T. , Kormanik, P.P. and Black, C.C. (1989) Characterization of sucrolysis via the uridine diphosphate and pyrophosphate‐dependent sucrose synthase pathway. Plant Physiol. 90, 635–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zila, C.T. , Samayoa, L.F. , Santiago, R. , Butrón, A. and Holland, J.B. (2013) A genome‐wide association study reveals genes associated with Fusarium ear rot resistance in a maize core diversity panel. G3, 3, 2095–2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 Aspergillus flavus (Af) and Fusarium verticillioides (Fv) colonization in maize kernels. Kernel sections were stained with safranin and fast green. Af (a) and Fv (b) colonized at the inoculation site at 48 h post‐inoculation (hpi). Af typically colonized and destroyed the aleurone (Al) (c), whereas Fv often colonized in the intact Al (d) and destroyed the Al at a later infection stage (f). Af colonized at the endosperm (En)–scutellum (Sc) interface forming a biofilm‐like structure and colonizing the Sc (e). Af colonized the Sc tip of a kernel with obvious damage to the germ (g). Fv colonized the En (h). Af (i) and Fv (j) colonized the En, creating cavities (Ca) in the En (j). Arrows denote fungal colonization. Scale bars: (a, b, g, h) 200 μm; (c, d, f, j) 30 μm; (e, i) 50 μm.