Summary

Previous work has implicated glycerol‐3‐phosphate (G3P) as a mobile inducer of systemic immunity in plants. We tested the hypothesis that the exogenous application of glycerol as a foliar spray might enhance the disease resistance of Theobroma cacao through the modulation of endogenous G3P levels. We found that exogenous application of glycerol to cacao leaves over a period of 4 days increased the endogenous level of G3P and decreased the level of oleic acid (18:1). Reactive oxygen species (ROS) were produced (a marker of defence activation) and the expression of many pathogenesis‐related genes was induced. Notably, the effects of glycerol application on G3P and 18:1 fatty acid content, and gene expression levels, in cacao leaves were dosage dependent. A 100 mm glycerol spray application was sufficient to stimulate the defence response without causing any observable damage, and resulted in a significantly decreased lesion formation by the cacao pathogen Phytophthora capsici; however, a 500 mm glycerol treatment led to chlorosis and cell death. The effects of glycerol treatment on the level of 18:1 and ROS were constrained to the locally treated leaves without affecting distal tissues. The mechanism of the glycerol‐mediated defence response in cacao and its potential use as part of a sustainable farming system are discussed.

Keywords: disease resistance, glycerol application, oleic acid, Phytophthora capsici, PR genes, Theobroma cacao

Introduction

Theobroma cacao L. (cacao) is a small understory tropical tree endemic to the Amazon basin and is widely grown in West Africa, Central and South America, Malaysia, Indonesia and elsewhere in the humid tropics worldwide (Lass and Wood, 2008). Cacao is an important cash crop for 40–50 million farmers and their families, and provides the main raw ingredient used for chocolate manufacturing, supporting an $80 billion global business. The main constraints on cacao cultivation are a range of destructive pathogenic diseases, which result in a loss of about 30%–40% of the annual world production. The three most severe diseases, black pod, frosty pod and witches' broom, which have been described as the ‘trilogy of crippling fungal disease’ (Evans, 2007; Fulton, 1989), are caused by Phytophthora spp., Moniliophthora roreri and Moniliophthora perniciosa, respectively. Although there are extensive efforts underway to breed disease‐resistant cacao varieties, limited success has been reported over the past few decades because of the difficult breeding system, scarcity of financial and genetic resources, and lack of good sources of durable disease resistance genes. Therefore, strategies complementary to genetic approaches are important for the deployment of integrated crop management solutions.

Foliar sprays (insecticides and fungicides) have commonly been employed as effective tools for the disease management of many crop species (Buck et al., 2008; Dann et al., 1998; Reuveni et al., 1998). In cacao, copper‐based fungicides and insecticides, such as organochlorides, are sprayed onto foliage to protect against Moniliophthora, Phytophthora spp. and mirids (Okoya et al., 2013; Sosan and Akingbohungbe, 2009). However, there is a concern about the environmental consequences of heavy metal fungicides and the potential risks to human health as a result of the mishandling and carryover effects of pesticide residues (Okoya et al., 2013).

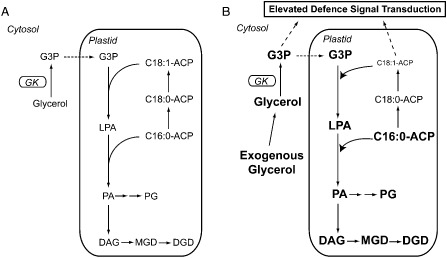

A significant role of glycerol and its in vivo derivative glycerol‐3‐phosphate (G3P) in the participation of the plant defence response has been described previously (Chanda et al., 2008, 2011; Kachroo et al., 2003). Glycerol is an environmentally friendly, non‐toxic, edible and biodegradable sugar alcohol. As a byproduct of the booming biodiesel industry, large amounts of low‐cost glycerol are expected to be produced in the coming years (Yang et al., 2012), and thus the utility of glycerol in agricultural applications has been explored previously as a potential added‐value byproduct of biofuels production (Tisserat and Stuff, 2011). The application of glycerol in foliar sprays has been found to stimulate short‐term plant growth in diverse plant species under glasshouse conditions; however, the mechanism of this enhancement has not been reported. One known physiological effect of the exogenous application of glycerol is an increase in the endogenous level of G3P via a glycerol kinase‐mediated reaction (Chandra‐Shekara et al., 2007; Eastmond, 2004b; Kachroo et al., 2004, 2008; Lu et al., 2001). This is of particular significance because the levels of G3P have been demonstrated to be closely associated with activation of the plant immune system. For example, the basal resistance of Arabidopsis to the fungal pathogen Colletotrichum higginsianum (Chanda et al., 2008) has been shown to be induced by G3P. Furthermore, G3P has been recognized as a novel mobile signal that is able to translocate from locally infected tissues to distal tissues to induce systemic acquired resistance (SAR) against a broad spectrum of pathogens on secondary infection (Chanda et al., 2011). In addition, as a precursor and backbone for the glycerolipid biosynthesis pathway, the plastidial level of G3P determines the carbon flux into the pathway, and thus regulates the level of oleic acid (18:1) through acylation (Fig. 1A; adapted from Chanda et al., 2008; Kachroo et al., 2004). Interestingly, together with the G3P‐induced SAR, the elevated G3P pool in plastids reduces the level of 18:1 fatty acid, which further triggers defence signal transduction (Kachroo et al., 2005; Venugopal et al., 2009), reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation (Campos et al., 2007), pathogenesis‐related (PR) gene expression (Chandra‐Shekara et al., 2007) and the hypersensitive response through a fatty acid‐derived signalling pathway (Chandra‐Shekara et al., 2007; Jiang et al., 2009; Kachroo et al., 2008; Mandal et al., 2012; Song et al., 2013).

Figure 1.

Abbreviated scheme of glycerol metabolism and glycerolipid biosynthesis pathway (adapted from Chanda et al., 2008) in cacao leaves and proposed effects of application of exogenous glycerol on metabolic pools. (A) Glycerol is phosphorylated to glycerol‐3‐phosphate (G3P) by glycerol kinase (GK) in the cytosol. G3P can translocate into plastids, where it is acylated with C18:1‐ACP (stearoyl‐acyl carrier protein) to yield lysophosphatidic acid (LPA). LPA can be further acylated with C16:0‐ACP (palmitoyl‐acyl carrier protein) to yield phosphatidic acid (PA). (B) On application of exogenous glycerol, metabolic flow on the plastidial glycerolipid pathway is increased through G3P, LPA, PA and diacylglycerol (DAG) pools (indicated as larger font sizes in bold), resulting in a reduction in C18:1‐ACP pools (indicated as reduced font sizes) and an elevation of C16:0‐ACP pools (indicated as larger font sizes in bold). DGD, digalactosyldiacylglycerol; MDG, monogalactosyldiacylglycerol; PG, phosphatidylglycerol.

Taking advantage of a rapid leaf disc pathogen screening bioassay developed in our laboratory, we explored the potential of application of glycerol as a foliar spray to enhance the disease resistance of cacao against the oomycete pathogen Phytophthora capsici (Evans, 2007; Fulton, 1989). Our results demonstrate that foliar glycerol application induces the plant defence response in cacao, and suggests that it has potential as an environmentally safe means to fight important plant diseases in the field.

Results

Glycerol application increased endogenous G3P levels and decreased oleic acid levels

According to the proposed glycerol metabolism pathway in plants (Chanda et al., 2008; Eastmond, 2004a), exogenously applied glycerol is absorbed by plant cells and further phosphorylated to G3P by glycerol kinase (EC 2.7.1.30) in the cytosol (Fig. 1B; adapted from Chanda et al., 2008). Given the fact that G3P can be transported into the plastids and acylated with oleic acid (18:1‐ACP) in the glycerolipid biosynthesis pathway (Chanda et al., 2008), increased endogenous levels of G3P may lead to a reduction in oleic acid levels (Fig. 1B). An increase in G3P and decrease in oleic acid levels are thought to be associated with induction of the defence pathway in various plant species.

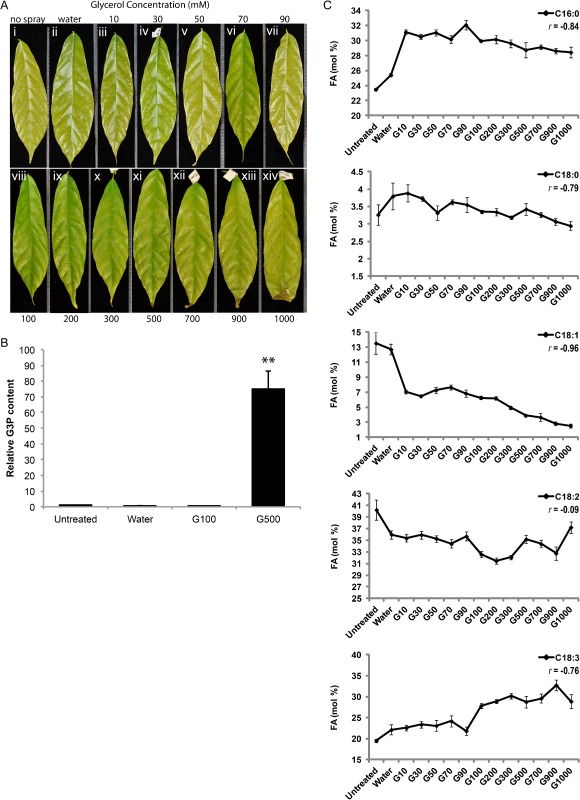

To explore the possibility of using glycerol as a foliar spray for the protection of cacao against pathogens, glycerol solutions at different concentrations were prepared in water and applied to SCA6 cacao, stage C leaves on three to four individual plants growing in a glasshouse (Fig. 2A). Water without any glycerol was also applied as a negative control on separate trees (Fig. 2A, ii). The selected individual leaves were repeatedly treated with water or glycerol once every 24 h for three consecutive days and the effects were evaluated 24 h after the last treatment. In water‐treated leaves, no visible phenotypic changes were observed, except for the normal developmental leaf expansion and hardening identical to that seen with untreated leaves (Fig. 2A, i and ii). Leaves treated with glycerol at concentrations of 10–300 mm also exhibited no significant phenotypic difference compared with untreated or water‐treated leaves (Fig. 2A, iii–x). However, the application of glycerol at concentrations higher than 300 mm caused chlorosis and yellowing of the leaf sections between the subveins, which were first observable 3 days after treatment (Fig. 2A, xi–xiv). The chlorosis increased in intensity with higher concentrations of glycerol and over time. Moreover, cell death was observed on the curled tips of these leaves 2 days after high‐concentration glycerol treatment (Fig. 2A, xi–xiv).

Figure 2.

Effects of glycerol application on leaf morphology, glycerol‐3‐phosphate (G3P) levels and fatty acid (FA) levels in cacao leaves. (A) Morphology of cacao leaves after exogenous glycerol treatments at various concentrations: (i) untreated; (ii) water treated; (iii–xiv) glycerol treated at concentrations 10, 30, 50, 70, 90, 100, 200, 300, 500, 700, 900 and 1000 mm, respectively. (B) Endogenous G3P levels measured 4 days after water or glycerol treatments (n = 7, mean ± SE). (C) FA levels after the indicated treatments. FA levels are presented as mol % (n = 4, mean ± SE). Significance was determined by t‐test (**P < 0.001).

The effect of the exogenous application of glycerol on the endogenous level of G3P within the treated leaves was evaluated by measurement of the G3P levels by ultrahigh‐performance liquid chromatography‐mass spectrometry (UHPLC‐MS) (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, untreated SCA6 cacao leaves contained significantly higher levels of G3P relative to leaves treated with water or 100 mm glycerol (P < 0.05), and no significant difference in the levels of G3P was observed between water‐treated and 100 mm glycerol‐treated leaves. Notably, the 500 mm glycerol application led to a massive increase in G3P of approximately 100‐fold in comparison with the water control (P < 0.001) and 100 mm glycerol‐treated leaves (P < 0.001). These results suggest that glycerol application at a low concentration (100 mm) does not result in the accumulation of G3P. However, the accumulation of G3P after treatment with higher concentrations of glycerol (500 mm) implies that the normal functions of plastids associated with lipid metabolism may be disrupted, which could be related to the phenotypic changes presented above (Fig. 2A).

To further explore the effects of exogenously applied glycerol on the metabolic pools that feed into the plastidial glycerolipid biosynthesis pathway, fatty acid profiles were determined by gas chromatography‐mass spectrometry (GC‐MS) (Fig. 2C). Among all the fatty acid species detected in our cacao leaf samples, 16:0, 18:0, 18:1 (n‐9), 18:2 (n‐6) and 18:3 (n‐3) were the major contributors to the fatty acid pools. Water treatment resulted in no significant difference in fatty acid composition relative to that of untreated leaves, except that 16:0 accumulated at a slightly higher molar proportion in water‐treated leaves than in untreated leaves (P < 0.05). Glycerol application had a significant impact on the levels of 16:0, 18:1 and 18:3, starting from the lowest concentration of glycerol tested (10 mm). Moreover, the progressive decrease in the 16:0 and 18:1 levels and increase in the 18:3 level were highly correlated with the increased concentrations of glycerol applied (correlation coefficient r = −0.84, −0.96 and 0.76, respectively; Fig. 2C). As indicated by the correlation coefficient, the level of 18:1 showed the strongest linear correlation with the concentration of exogenously applied glycerol, which is consistent with the scheme of the glycerolipid biosynthesis pathway (Fig. 1), in which 18:1 serves as the direct substrate for the G3P acylation reaction in plastids.

Glycerol application induced ROS accumulation and increased malondialdehyde (MDA) content in cacao leaves

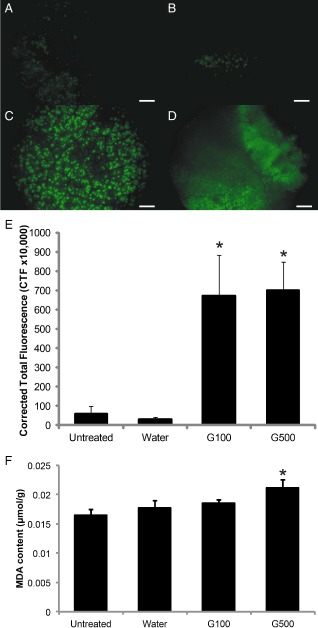

It has been well documented that the production and accumulation of ROS in infected plant tissues play a significant role in early pathogen recognition and defence‐related gene regulation (Torres et al., 2006). In addition, ROS can also lead directly to the cross‐linking of plant cell walls, lipid peroxidation and membrane disruption (Zurbriggen et al., 2010). In this respect, the correlation between the decreased level of 18:1 induced by glycerol and the generation of ROS has been reported in soybean (Kachroo et al., 2008) and rice (Jiang et al., 2009). Therefore, global levels of ROS in untreated, water‐ and glycerol‐treated SCA6 cacao leaves were measured by the 2′,7′‐dichlorofluorescein (DCF) staining method, where bright green fluorescence is an indication of the presence of ROS (Maxwell et al., 1999). Both 100 and 500 mm glycerol were tested, considering that 100 mm glycerol was able to decrease the 18:1 level without causing severe leaf chlorotic phenotypes (Fig. 2A). There was no significant difference in the fluorescence detected between the untreated and water‐treated SCA6 cacao leaves (Fig. 3A, B, E). However, both 100 and 500 mm glycerol application resulted in high levels of fluorescence, indicating significantly higher ROS accumulation in these treatments compared with either untreated or water‐treated leaves (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3C, D, E). No significant difference was observed between 100 and 500 mm glycerol treatments. These results indicate that glycerol application induces global ROS accumulation.

Figure 3.

Effects of glycerol application on reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation and malondialdehyde (MDA) content in cacao leaves. Representative microscope images of cacao leaves infiltrated with 2′,7′‐dichlorofluorescein (DCF) to stain total ROS. (A) Untreated. (B) Water treated. (C) 100 mm glycerol‐treated cacao leaves (G100). (D) 500 mm glycerol‐treated cacao leaves (G500). Scale bars, 0.5 mm. (E) Quantification of ROS accumulation in cacao leaves determined by corrected total fluorescence from DCF using ImageJ. (F) MDA content in cacao leaves (n = 7, mean ± SE). Significance was determined by t‐test (*P < 0.05).

One downstream effect of ROS accumulation is increased levels of lipid peroxidation products, such as MDA (Zoeller et al., 2012). Thus, MDA was measured as a proxy of lipid peroxidation in control and glycerol‐treated leaves (100 and 500 mm). As depicted in Fig. 3F, there was no significant difference in MDA concentration between untreated, water‐treated and 100 mm glycerol‐treated cacao leaves. However, the 500 mm glycerol treatment resulted in a further increase in MDA content, significantly higher than in untreated and water‐treated leaves (P < 0.05).

Glycerol induction of defence gene expression in cacao leaves

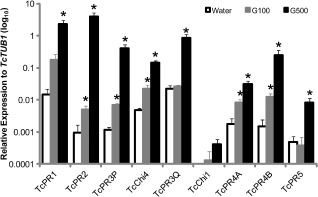

As the generation and accumulation of ROS are highly correlated with defence‐related gene regulation (Kachroo et al., 2008; Torres et al., 2006), the expression levels of five classes of PR genes (Chandra‐Shekara et al., 2007), PR‐1 to PR‐5, were measured in leaves after glycerol application. To select the orthologous genes in cacao, the full‐length amino acid sequences of PR‐1 to PR‐5 from tobacco (queries summarized in Table 1) were blasted against the predicted cacao proteome of the Belizian Criollo genotype (B97‐61/B2) (http://cocoagendb.cirad.fr/;Argout et al., 2011) using the blastp algorithm with an E‐value cut‐off of 1e−5 (Altschul et al., 1990). One hundred and five genes were identified (Table S1, see Supporting Information) and further screened for their inducibility by Colletotrichum and Phytophthora using available cacao microarray data (M. J. Guiltinan laboratory, unpublished data). As a result, 14 candidate genes were selected and their expression levels were evaluated by reverse transcription‐quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT‐qPCR) after treatment with water, 100 or 500 mm glycerol (Table 1 and Table S2). Two additional chitinase genes (TcChi1, Tc02g003890, Maximova et al., 2006; TcChi4, Tc04g018110, Zi et al., unpublished data) from the PR‐3 family were also included in this study, as the overexpression of these genes in cacao conferred resistance against certain pathogens in our previous study. TcTUB1 (Tc06g000360), which was previously identified as the most stable gene during leaf development, was used as the reference gene. The relative expression of PR genes was plotted on a log10 scale (Fig. 4).

Table 1.

Summary of the changes in pathogenesis‐related (PR) gene expression levels in response to 100 and 500 mm glycerol application measured by reverse transcription‐quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT‐qPCR). Expression levels were normalized to TcTUB1. Fold changes were calculated as a ratio of the relative expression levels between glycerol‐ and water‐treated leaves (n = 3)

| PR family | Identifier in cacao genome database | Annotation in cacao genome database | Average fold change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G100/water | G500/water | |||

| PR‐1 | Tc02g002410 | Pathogenesis‐related protein 1 | 9.87 | 156.46 |

| PR‐2 | Tc04g029300 | Glucan endo‐1,3‐β‐glucosidase, basic vacuolar isoform | 3.31 | 4174.80 |

| PR‐3P | Tc01g000770 | Endochitinase | 3.56 | 348.71 |

| Chi4 | Tc04g018110 | Endochitinase PR4 | 4.60 | 30.05 |

| PR‐3Q | Tc04g018160 | Endochitinase PR4 | 0.89 | 37.51 |

| Chi1 | Tc02g003890 | Endochitinase 1 | nd | nd |

| PR‐4A | Tc05g027220 | Pathogenesis‐related protein P2 | 4.70 | 17.65 |

| PR‐4B | Tc05g027210 | Pathogenesis‐related protein PR‐4B | 3.44 | 164.63 |

| PR‐5 | Tc03g026990 | Thaumatin‐like protein | 0.97 | 16.42 |

nd, not determined.

Figure 4.

Transcript levels of pathogenesis‐related (PR) genes measured by reverse transcription‐quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT‐qPCR). The relative expression levels of PR genes were quantified and compared after treatment with water, 100 and 500 mm glycerol (G100 and G500). The expression levels of PR genes were normalized to that of TcTUB1 and plotted on a log10 scale (n = 3, mean ± SE). Significance was determined by t‐test (*P < 0.05).

Every gene evaluated showed a high level of induction in the 500 mm‐treated leaves, up to a 4174‐fold increase. With the 100 mm treatment, all but two of the genes showed a more modest increase in expression, up to 10‐fold. In general, the results clearly indicate that glycerol application significantly up‐regulates the expression of a set of PR genes (Table 1). With the 100 mm glycerol treatment, two genes, PR‐3Q and PR‐5, were not significantly induced (Fig. 4). The expression of TcChi1 was significantly induced under both 100 and 500 mm glycerol applications, even though its expression was not detectable under the specific RT‐qPCR conditions in water‐treated leaves. Moreover, the expression of TcChi4 was up‐regulated by about five‐ and 30‐fold by 100 and 500 mm glycerol applications, respectively, relative to water‐treated leaves (Table 1).

Glycerol application enhanced the disease resistance of cacao leaves against P . capsici

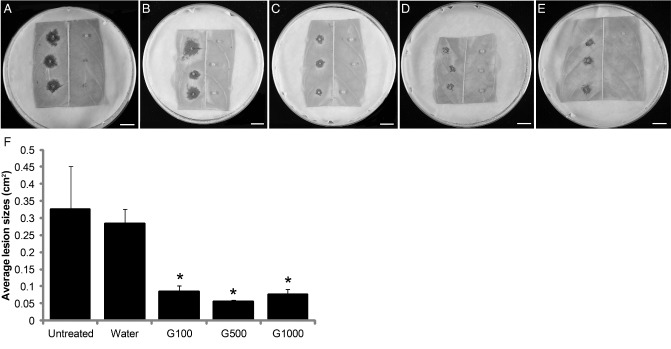

Previously, it has been reported that overexpression of TcChi1 enhances the resistance of cacao leaves against Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (Maximova et al., 2006) and that PR‐1, PR‐2, PR3, PR‐4 and PR‐5 have direct antifungal and/or anti‐oomycete activities in many plant species, such as tobacco and wheat (Campos et al., 2007; van Loon et al., 2006; Yun, 1996). Thus, the impact of glycerol application on the disease resistance of cacao leaves against pathogens was investigated using an in vivo pathogenicity assay. Stage C leaves of SCA6 were treated with glycerol or water for three consecutive days; leaf discs were excised 24 h after the last treatment and infected with the cacao pathogen P. capsici. Untreated leaf discs were also infected with P. capsici as a control. Leaves were photographed (Fig. 5A–E) and lesion sizes were measured 3 days after infection. There were no significant differences in the average sizes of the lesions between untreated and water‐treated cacao leaves (Fig. 5F). Notably, all three glycerol treatments drastically decreased the average lesion size relative to untreated or water‐treated leaves (P < 0.05). There were no significant differences in the average sizes of the lesions among the 100, 500 and 1000 mm glycerol treatments (Fig. 5F), indicating that 100 mm glycerol was sufficient to induce disease resistance against P. capsici, and that increased glycerol concentration did not contribute to further increased resistance. Glycerol treatments at a concentration lower than 100 mm were also evaluated (50, 70 and 90 mm), and did not result in a consistent enhanced resistance response (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Glycerol enhanced disease resistance of cacao leaves against Phytophthora capsici. (A–E) Representative images of leaf lesions 3 days after inoculation with P. capsici. (A) Untreated leaves. (B) Leaves treated with water. (C) Leaves treated with 100 mm glycerol. (D) Leaves treated with 500 mm glycerol. (E) Leaves treated with 1000 mm glycerol. Glycerol treatments at the designated concentrations were applied once per day every 24 h for three consecutive days prior to P. capsici infection. (F) Average lesion sizes were measured by ImageJ 3 days after inoculation with P. capsici (n = 7, mean ± SE). Significance was determined by t‐test (*P < 0.05).

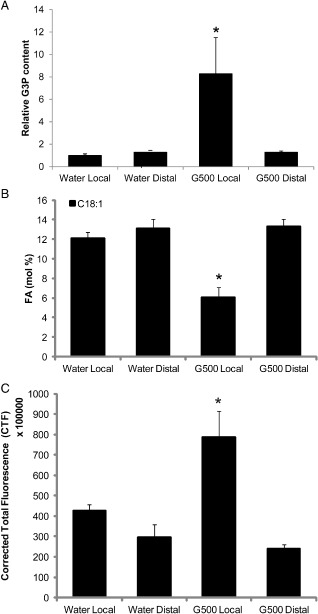

Local glycerol treatments did not affect G3P, ROS or 18:1 levels in distal leaves

We tested whether glycerol treatment would act systemically to alter the levels of G3P, 18:1 and ROS in distal non‐treated leaves. Water or 500 mm glycerol was applied to five leaves of the same branch on two separate cacao plants. Treated leaves and leaves from distal branches were collected and G3P, 18:1 and ROS levels were examined. Consistent with previous results, glycerol application significantly increased G3P and ROS levels and decreased 18:1 levels in the treated leaves relative to water‐treated leaves (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6A–C). However, no significant differences were recorded for the G3P, ROS and 18:1 levels in non‐treated distal leaves on glycerol‐treated plants relative to the water controls (Fig. 6A–C), suggesting that, under the conditions tested, local glycerol treatment did not produce a mobile signal that would induce a similar response in distal leaves; this was consistent with the result indicating that the exogenous application of G3P alone is not sufficient to induce the translocation of G3P to distal tissues (Chanda et al., 2011).

Figure 6.

Glycerol‐3‐phosphate (G3P), fatty acid (FA, 18:1) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in distal leaves in response to local glycerol treatment. (A) G3P levels in local and distal water‐ or glycerol‐treated cacao leaves (n = 4, mean ± SE). (B) 18:1 levels in local and distal water‐ or glycerol‐treated cacao leaves (n = 5, mean ± SE). (C) ROS levels in local and distal water‐ or glycerol‐treated cacao leaves (n = 3, mean ± SE). Significance was determined by t‐test (*P < 0.05).

Discussion

The mechanism of the glycerol‐mediated defence response in cacao

The present study provides a proof of concept of the application of glycerol to enhance disease resistance in cacao. We observed dose responses to glycerol treatment in the cacao leaf physiological and molecular states, which have not been reported previously. A strong correlation (r = −0.96) between the concentration of the exogenously applied glycerol and the oleic acid content of treated leaves indicated that the effects of glycerol application on disease resistance are likely to be transduced through a fatty acid (18:1, oleic acid)‐mediated signalling pathway. In this respect, it has been well documented that a decreased level of 18:1 in the Arabidopsis ssi2 mutant induces ROS production, PR gene expression, hypersensitive response and spontaneous cell death, and that exogenous application of glycerol can mimic these phenotypes (Kachroo et al., 2003, 2004). Thus, it is likely, and consistent with our data, that glycerol application induces defence responses in cacao through a similar mechanism. The fact that glycerol application significantly up‐regulates a large set of PR genes in cacao leaves provides further insights into the mechanism of the induced defence response. For example, it has been demonstrated previously by our group that the overexpression of TcChi1 enhances the resistance of cacao to C. gloeosporioides (Maximova et al., 2006) and P. capsici (Zi et al., unpublished data), which is consistent with our observation that the elevated level of TcChi1 induced by glycerol enhances the resistance to P. capsici. Although detailed functional characterization of other PR genes is still needed, it is likely that glycerol application is able to confer broad‐spectrum resistance, as the direct activities of these PR genes against various fungi and oomycete pathogens have been well illustrated in cacao and other plant species (Campos et al., 2007; Sels et al., 2008). Moreover, in general, the induction of PR genes by glycerol application has been observed to be dose dependent, which may result from increasing levels of transduction signals involved in the 18:1 pathway, such as nitric oxide (Mandal et al., 2012) and/or salicylic acid (SA) (Kachroo et al., 2003; Shah et al., 2001). Together, our data suggest that glycerol application may enhance the disease resistance of cacao leaves via an 18:1‐mediated defence signalling pathway.

As an initial acylation substrate for glycerolipid biosynthesis in plastids, the level of 18:1 is tightly modulated by the level of the glycerol derivative G3P (Chanda et al., 2008). Compelling evidence has revealed the significant role of G3P in contributing to the basal resistance of Arabidopsis against C. higginsianum (Chanda et al., 2008) and as a critical immune signal generated following local pathogen infection to confer SAR in the distal tissues (Chanda et al., 2011). However, it is noteworthy that 100 mm glycerol application conferred sufficient resistance in cacao leaves against P. capsici without significant alteration of the endogenous G3P level, suggesting that G3P does not seem to be involved in the defence response at this level (Fig. 2B), and it is more likely that G3P serves as the intermediate for the acylation of 18:1 instead of the accumulation in plastids. However, our data cannot rule out the possibility that elevated G3P levels might contribute to the enhanced resistance of cacao to pathogens, as 500 mm glycerol application led to a massive accumulation of G3P and also resulted in enhanced resistance (Fig. 5A, B). Alternatively, another explanation for the accumulation of G3P could be that high‐concentration glycerol (500 mm) causes phytotoxic damage to cacao leaves (Fig. 2B) and disrupts the normal function of plastids, which affects the glycerolipid biosynthesis pathway and thus causes the accumulation of G3P as an intermediate. This hypothesis is further supported by the fact that 500 mm glycerol application increases ROS production (singlet oxygen 1O2 and free radicals; Jambunathan, 2010; Zoeller et al., 2012) and elevates the level of lipid peroxidation measured by the MDA content (Fig. 3F), which could potentially destroy the integrity of membranes (Folden et al., 2003) and lead to cell death and prominent symptoms of the hypersensitive response, which have never been described in cacao (Fig. 2A).

It was observed that local glycerol treatment of cacao leaves did not lead to changes in G3P, fatty acid profiles and ROS production levels in distal tissues. Consistent with this observation, in Arabidopsis, the exogenous application of G3P alone did not result in the translocation of G3P into distal tissue (Chanda et al., 2011). Interestingly, DIR1, a lipid transfer protein, was required to assist the translocation of G3P to confer SAR in distal tissue. Thus, it seems plausible that the glycerol applications we tested in cacao did not induce DIR1 accumulation to aid the movement of G3P. However, the elevated level of G3P in locally treated tissue could still be beneficial to induce enhanced SAR when plants are exposed to pathogens and the expression of DIR1 is induced (Chanda et al., 2011). Meanwhile, it has been discovered recently that the NO/ROS → azelaic acid (AzA) → G3P‐derived signalling pathway operates in parallel with the SA pathway to induce SAR, and that ROS triggers SAR in a concentration‐dependent manner (Wang et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2013). Therefore, it is equally possible that glycerol‐induced accumulation of ROS might negatively regulate SAR, which could explain why the local increase in G3P did not induce similar effects in distal leaf tissues. Overall, it remains a formal possibility that either or both pathways are involved in the mechanism of the glycerol‐induced defence response in cacao.

The potential of application of glycerol as a foliar spray in cacao plantations

As mentioned earlier, cacao is very susceptible to many severe diseases that cause significant yield loss in cacao plantations (Evans, 2007). A low‐cost and effective strategy for disease control is thus greatly needed. Remarkably, in this aspect, glycerol is an environmentally friendly chemical excessively generated as a low‐cost byproduct from the biodiesel industry. Our results provide strong evidence to suggest that glycerol has great potential to be applied as a substitute or additive into current agricultural chemicals, which also satisfies the urgent need for the exploration of the value‐added utilization of glycerol (Yang et al., 2012). Further research is needed to bring this potential technology to commercialization. For example, the dosage, timing and intervals of application need to be characterized under natural tropical conditions. In addition, given that the effects of glycerol application in our studies were constrained to locally treated tissues, a broader spray on a whole‐plant scale might be considered to achieve better performance. Further investigations with more cacao pathogens are needed to determine the potential efficacy of glycerol treatment for different diseases and in different cacao‐growing regions.

Experimental Procedures

Glycerol treatment

Fully expanded leaves, developmental stage C (Shi, 2010), of glasshouse‐grown SCA6 were treated with glycerol (MP, Biomedicals, Aurora, OH, USA, Cat. 800688) solutions at various concentrations prepared in sterile water containing 0.04% Silwett L‐77 (Fisher Scientific, Cat. NC0138454). Water containing 0.04% Silwett L‐77 was used as the control treatment. Leaves were completely immersed in 100 mL solutions for 10 s every 24 h for three consecutive days, and collected 24 h after the last treatment for pathogen bioassay and fatty acid analysis.

G3P extraction and quantification by UHPLC‐MS

To determine G3P levels, 1 g of cacao leaf tissue was frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground to a fine powder. About 30 mg of ground tissue were weighed and extracted with 5 mL of 80% (v/v) ethanol, and centrifuged at 5520 g for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were collected and 10 μL aliquots were analysed by UHPLC‐MS (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA, Ultimate 3000 pump and Thermo Exactive Plus Orbitrap). The method and instrumentation were based on an ion‐pairing reversed‐phase negative ion Orbitrap method (Lu et al., 2010); a smaller particle size C18 column was used (Titan 100 mm × 2.1 mm; particle size, 1.9 μm; Sigma, St. Louis, MI, USA) and the mass spectrometer was scanned from 85 to 1000 m/z at a resolution of 140 000 throughout the entire run. Under these conditions, G3P bis salt (Sigma, Cat. G7886) eluted as a single peak at m/z 171.0063 with a retention time of 7.27 min. The integrated areas of the reconstructed ion chromatograms for this ion were used to measure the amount of G3P in the extracts.

Fatty acid profiling by GC‐MS

Plant tissue from glycerol‐treated and control leaves (four biological replicates) was ground in liquid nitrogen, and fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) were prepared from each sample using approximately 30 mg of tissue per sample. Briefly, 1 mL of a methanol–fuming HCl–dichloromethane (10:1:1, v/v) solution was added to each tissue sample and incubated without shaking at 80 °C for 2 h. FAMEs were re‐extracted in 1 mL of buffer (H2O–hexane–dichloromethane, 5:4:1, v/v) with vortexing for 1 min. The hexane (upper phase) was separated by centrifugation at 1500 g for 5 min, transferred to glass GC vials (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and evaporated to dryness under vacuum. The FAMEs were then dissolved in 500 μL of hexane for GC‐MS analysis. Pentadecanoic acid (C15:0) (Sigma, Cat. P6125) was used as the internal standard, added prior to the extraction, and methyl nonadecanoate (C19:0‐methyl ester) (Sigma, Cat. N5377) was used as the spike control, added to the sample prior to the GC injection. Samples were analysed on an Agilent 6890N gas chromatograph coupled to a (Waters, Milford, MI, USA) GCT time‐of‐flight mass spectrometer. Mass spectra were acquired in electron ionization mode (70 eV) from 45 to 500 Da at a rate of one scan per second. The samples were separated on an Omegawax® 250 Capillary GC column (30 m × 0.25 mm; phase thickness, 0.25 μm; Sigma, Cat. 24136) using helium at a constant flow of 1.0 mL/min. The initial oven temperature was 100 °C held for 1 min, increased at 15 °C/min to a temperature of 150 °C, and then increased at 4 °C/min to a final temperature of 280 °C. Samples (1 μL) were injected onto the column using a split/splitless injector maintained at 240 °C with a split ratio of 50:1.

DCF staining of ROS production

Fully expanded, stage C leaves of genotype SCA6 were detached from cacao seedlings after treatment and vacuum infiltrated for 2 min with 20 μm 2′,7′‐dichlorodihydrofluorescin diacetate [H2DCF‐DA; Sigma; 20 mm stock in dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO)]. To avoid saturation of the fluorescence signal, samples were photographed exactly 2 min after infiltration. Images were obtained at 7.5× magnification using a (Nikon, Melville, NY, USA) SMZ‐4 stereomicroscope equipped with an epifluorescence attachment, a 100 W mercury light source and a three CCD video camera system (Optronics Engineering, Goleta, CA, USA). The fluorescence imaging filters were 450–490 nm for excitation and 520–560 nm for emission. Images were analysed by ImageJ software and the corrected total fluorescence (CTF) of DCF was calculated by the formula: CTF = integrated density − (area of selected cell × mean fluorescence of background readings).

Lipid peroxidation assay

Lipid peroxidation in untreated and glycerol‐treated cacao leaves was measured by determination of the MDA content using thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) assay. After treatment, cacao leaves were rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground to a fine powder (30 mg per sample). Five millilitres of 0.1% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) were added to each sample and centrifuged at 5520 g (maximum speed) for 5 min. One millilitre of the supernatant was collected per sample and mixed with 2 mL of TBARS reagent consisting of 15% TCA and 0.375% 2‐thiobarbituric acid (TBA) in 0.25 m HCl. The mixture was boiled for 15 min, cooled on ice for 10 min and centrifuged at 3320 g for 5 min. Two hundred microlitres of supernatant were collected and the absorbance was read at 532 nm. The MDA standard curve was prepared using 1,1,3,3‐tetraethoxypropane.

RNA extraction and RT‐qPCR analysis of gene expression

Plant tissues were first ground in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was extracted using Plant RNA Purification Reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA, Cat. 12322‐012) following the manufacturer's protocol. The concentration of RNA was measured using a Nanodrop 2000c (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). RNA was further treated with RQ1 RNase‐free DNase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA, Cat. M6101) to remove potential genomic DNA contamination (following the manufacturer's protocol). Five hundred nanograms of treated RNA were reverse transcribed by M‐MuLV Reverse Transcriptase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) with oligo‐(dT)15 primers to obtain cDNA. RT‐qPCR was performed in a total reaction volume of 10 μL containing 4 μL of diluted cDNA (1:50), 5 μL of SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Takara, Mountain View, CA, USA), 0.2 μL of Rox and 0.4 μL of each 5 μm primer. Each reaction was performed in duplicate using the (Roche, Nutley, NJ, USA) Applied Biosystem Step One Plus Realtime PCR System with the following program: 15 min at 94 °C, 40 cycles of 15 s at 94 °C, 20 s at 60 °C and 40 s at 72 °C. The specificity of the primer pair was examined by PCR visualized on a 2% agarose gel and dissociation curve. A tubulin gene in cacao (Tc06g000360, TcTUB1; Argout et al., 2011) (TcTUB1‐5′, GGAGGAGTCTCTATAAGCTTGCAGTTGG; TcTUB1‐3′, ACATAAGCATAGCCAGCTAGAGCCAG) was used as a reference gene.

Leaf disc pathogen bioassay of cacao leaves

Fully expanded, stage C leaves of genotype SCA6 were collected after treatment, and detached leaf pathogen bioassays were performed as described previously by Mejia et al. (2012). Briefly, leaves were detached, dissected and the middle sections of the leaves were transferred abaxial side up to a new Petri dish on top of 3M filter paper soaked with 10 mL of sterile water to maintain humidity. The right side of each leaf, delineated by the midvein, was inoculated with three agar plugs (core bore diameter, 3 mm) of P. capsici mycelium. Sterile agar plugs were placed on the left side of each leaf as negative controls. Inoculated leaves were then incubated at 27 °C and 12 h:12 h (light : dark) for 3 days before the evaluation of disease symptoms. At least five biological replicates from each treatment were infected, and images were taken for the measurement of the average lesion size by ImageJ software. Three lesions on the same leaf disc were taken as technical replicates. Average lesion sizes were calculated from biological replicates and significance was determined by t‐test.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have submitted an invention disclosure on the described technology, but that they have no other competing interests.

Authors' Contributions

YZ conceived and performed most of the experiments, such as the glycerol treatments, G3P and fatty acid extractions, gene expression analysis and pathogen assays. PS participated in developing the G3P extraction and quantification protocol, HPLC‐MS and GC‐MS analysis, and reviewed the manuscript. SNM was involved in designing and directing the experiments, and revising the manuscript. MJG contributed to the conception of the study, gave advice on experiments, and drafted and finalized the manuscript.

Supporting information

Table S1 Putative PR‐1–PR‐5 genes identified in the cacao genome by the blastp algorithm.

Table S2 Primer sequences for SYBR Green assay of pathogenesis‐related (PR) genes analysed by reverse transcription‐quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT‐qPCR).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Lena Sheaffer and Brian Rutkowski for technical assistance in the maintenance of our glasshouse. We are also grateful to Andrew Fisher for valuable comments to improve the manuscript. This work was supported in part by The Pennsylvania State University, College of Agricultural Sciences, The Huck Institutes of Life Sciences, the American Research Institute Penn State Endowed Program in the Molecular Biology of Cacao and a grant from the National Science Foundation BREAD program (NSF0965353), which supported the development of the transient gene expression assay for cacao.

References

- Altschul, S.F. , Gish, W. , Miller, W. , Myers, E.W. and Lipman, D.J. (1990) Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argout, X. , Salse, J. , Aury, J.M. , Guiltinan, M.J. , Droc, G. , Gouzy, J. , Allegre, M. , Chaparro, C. , Legavre, T. , Maximova, S.N. , Abrouk, M. , Murat, F. , Fouet, O. , Poulain, J. , Ruiz, M. , Roguet, Y. , Rodier‐Goud, M. , Barbosa‐Neto, J.F. , Sabot, F. , Kudrna, D. , Ammiraju, J.S.S. , Schuster, S.C. , Carlson, J.E. , Sallet, E. , Schiex, T. , Dievart, A. , Kramer, M. , Gelley, L. , Shi, Z. , Berard, A. , Viot, C. , Boccara, M. , Risterucci, A.M. , Guignon, V. , Sabau, X. , Axtell, M.J. , Ma, Z.R. , Zhang, Y.F. , Brown, S. , Bourge, M. , Golser, W. , Song, X.A. , Clement, D. , Rivallan, R. , Tahi, M. , Akaza, J.M. , Pitollat, B. , Gramacho, K. , D′Hont, A. , Brunel, D. , Infante, D. , Kebe, I. , Costet, P. , Wing, R. , McCombie, W.R. , Guiderdoni, E. , Quetier, F. , Panaud, O. , Wincker, P. , Bocs, S. and Lanaud, C. (2011) The genome of Theobroma cacao . Nat. Genet. 43, 101–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck, G.B. , Korndörfer, G.H. , Nolla, A. and Coelho, L. (2008) Potassium silicate as foliar spray and rice blast control. J. Plant Nutr. 31, 231–237. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, M.A. , Rosa, D.D. , Teixeira, J.É.C. , Targon, M.L.P.N. , Souza, A.A. , Paiva, L.V. , Stach‐Machado, D.R. and Machado, M.A. (2007) PR gene families of citrus: their organ specific‐biotic and abiotic inducible expression profiles based on ESTs approach. Genet. Mol. Biol. 30, 917–930. [Google Scholar]

- Chanda, B. , Venugopal, S.C. , Kulshrestha, S. , Navarre, D.A. , Downie, B. , Vaillancourt, L. , Kachroo, A. and Kachroo, P. (2008) Glycerol‐3‐phosphate levels are associated with basal resistance to the hemibiotrophic fungus Colletotrichum higginsianum in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 147, 2017–2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanda, B. , Xia, Y. , Mandal, M.K. , Yu, K. , Sekine, K.T. , Gao, Q.M. , Selote, D. , Hu, Y. , Stromberg, A. , Navarre, D. , Kachroo, A. and Kachroo, P. (2011) Glycerol‐3‐phosphate is a critical mobile inducer of systemic immunity in plants. Nat. Genet. 43, 421–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra‐Shekara, A.C. , Venugopal, S.C. , Barman, S.R. , Kachroo, A. and Kachroo, P. (2007) Plastidial fatty acid levels regulate resistance gene‐dependent defense signaling in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 104, 7277–7282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dann, E. , Diers, B. , Byrum, J. and Hammerschmidt, R. (1998) Effect of treating soybean with 2,6‐dichloroisonicotinic acid (INA) and benzothiadiazole (BTH) on seed yields and the level of disease caused by Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in field and greenhouse studies. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 104, 271–278. [Google Scholar]

- Eastmond, P.J. (2004a) Glycerol‐insensitive Arabidopsis mutants: gli1 seedlings lack glycerol kinase, accumulate glycerol and are more resistant to abiotic stress. Plant J. 37, 617–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastmond, P.J. (2004b) Cloning and characterization of the acid lipase from castor bean. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 45540–45545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, H.C. (2007) Cacao diseases—the trilogy revisited. Phytopathology, 97, 1640–1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folden, D.V. , Gupta, A. , Sharma, A.C. , Li, S.Y. , Saari, J.T. and Ren, J. (2003) Malondialdehyde inhibits cardiac contractile function in ventricular myocytes via a p38 mitogen‐activated protein kinase‐dependent mechanism. Br. J. Pharmacol. 139, 1310–1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulton, R. (1989) The cacao disease trilogy: black pod, Monilia pod rot, and witches'‐broom. Plant Dis. 73, 601–603. [Google Scholar]

- Jambunathan, N. (2010) Determination and detection of reactive oxygen species (ROS), lipid peroxidation, and electrolyte leakage in plants. Plant Stress Tolerance Methods Protoc. 639, 291–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, C.J. , Shimono, M. , Maeda, S. , Inoue, H. , Mori, M. , Hasegawa, M. , Sugano, S. , Takatsuji, H. (2009) Suppression of the rice fatty‐acid desaturase gene OsSSI2 enhances resistance to blast and leaf blight diseases in rice. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 22, 820–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachroo, A. , Lapchyk, L. , Fukushige, H. , Hildebrand, D. , Klessig, D. and Kachroo, P. (2003) Plastidial fatty acid signaling modulates salicylic acid‐ and jasmonic acid‐mediated defense pathways in the Arabidopsis ssi2 mutant. Plant Cell, 15, 2952–2965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachroo, A. , Venugopal, S.C. , Lapchyk, L. , Falcone, D. , Hildebrand, D. and Kachroo, P. (2004) Oleic acid levels regulated by glycerolipid metabolism modulate defense gene expression in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 101, 5152–5157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachroo, A. , Fu, D.Q. , Havens, W. , Navarre, D. , Kachroo, P. and Ghabrial, S.A. (2008) An oleic acid‐mediated pathway induces constitutive defense signaling and enhanced resistance to multiple pathogens in soybean. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 21, 564–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachroo, P. , Venugopal, S.C. , Navarre, D.A. , Lapchyk, L. and Kachroo, A. (2005) Role of salicylic acid and fatty acid desaturation pathways in ssi2‐mediated signaling. Plant Physiol. 139, 1717–1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lass, R.A. and Wood, G.A.R. (2008) Diseases In: Cocoa (Wiley‐Blackwell, 4 edition), pp. 265–365. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Blackwell Science Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- van Loon, L.C. , Rep, M. and Pieterse, C.M. (2006) Significance of inducible defense‐related proteins in infected plants. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 44, 135–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, M. , Tang, X.Y. and Zhou, J.M. (2001) Arabidopsis NHO1 is required for general resistance against Pseudomonas bacteria. Plant Cell, 13, 437–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, W. , Clasquin, M.F. , Melamud, E. , Amador‐Nogues, D. , Caudy, A.A. , Rabinowitz, J.D. , (2010) Metabolomic analysis via reversed‐phase ion‐pairing liquid chromatography coupled to a stand alone orbitrap mass spectrometer. Anal Chem, 82, 3212–3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal, M.K. , Chandra‐Shekara, A.C. , Jeong, R.D. , Yu, K.S. , Zhu, S.F. , Chanda, B. , Navarre, D. , Kachroo, A. and Kachroo, P. (2012) Oleic acid‐dependent modulation of NITRIC OXIDE ASSOCIATED1 protein levels regulates nitric oxide‐mediated defense signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell, 24, 1654–1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maximova, S.N. , Marelli, J.P. , Young, A. , Pishak, S. , Verica, J.A. and Guiltinan, M.J. (2006) Over‐expression of a cacao class I chitinase gene in Theobroma cacao L. enhances resistance against the pathogen, Colletotrichum gloeosporioides . Planta, 224, 740–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, D.P. , Wang, Y. and McIntosh, L. (1999) The alternative oxidase lowers mitochondrial reactive oxygen production in plant cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 8271–8276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejia, L. , Guiltinan, M. , Shi, Z. , Landherr, L. and Maximova, S. (2012) Expression of designed antimicrobial peptides in Theobroma cacao L. trees reduces leaf necrosis caused by Phytophthora spp. Small Wonders Peptides Dis. Control, 1905, 379–395. [Google Scholar]

- Okoya, A.A. , Ogunfowokan, A.O. , Asubiojo, O.I. and Torto, N. (2013) Organochlorine pesticide residues in sediments and waters from cocoa producing areas of Ondo State, southwestern Nigeria. ISRN Soil Sci. 2013, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Reuveni, R. , Dor, G. and Reuveni, M. (1998) Local and systemic control of powdery mildew (Leveillula taurica) on pepper plants by foliar spray of mono‐potassium phosphate. Crop Prot. 17, 703–709. [Google Scholar]

- Sels, J. , Mathys, J. , De Coninck, B.M.A. , Cammue, B.P.A. and De Bolle, M.F.C. (2008) Plant pathogenesis‐related (PR) proteins: a focus on PR peptides. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 46, 941–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah, J. , Kachroo, P. , Nandi, A. and Klessig, D.F. (2001) A recessive mutation in the Arabidopsis SSI2 gene confers SA‐ and NPR1‐independent expression of PR genes and resistance against bacterial and oomycete pathogens. Plant J. 25, 563–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Z. (2010) Functional analysis of Non Expressor of PR1 (NPR1) and its paralog NPR3 in Theobroma cacao and Arabidopsis thaliana In: Integrative Biosciences, pp. 1–215. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University. [Google Scholar]

- Song, N. , Hu, Z. , Li, Y. , Li, C. , Peng, F. , Yao, Y. , Peng, H. , Ni, Z. , Xie, C. and Sun, Q. (2013) Overexpression of a wheat stearoyl‐ACP desaturase (SACPD) gene TaSSI2 in Arabidopsis ssi2 mutant compromise its resistance to powdery mildew. Gene, 524, 220–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosan, M.B. and Akingbohungbe, A.E. (2009) Occupational insecticide exposure and perception of safety measures among cacao farmers in southwestern Nigeria. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health 64, 185–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tisserat, B. and Stuff, A. (2011) Stimulation of short‐term plant growth by glycerol applied as foliar sprays and drenches under greenhouse conditions. Hortscience, 46, 1650–1654. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, M.A. , Jones, J.D.G. and Dangl, J.L. (2006) Reactive oxygen species signaling in response to pathogens. Plant Physiol. 141, 373–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venugopal, S.C. , Jeong, R.D. , Mandal, M.K. , Zhu, S. , Chandra‐Shekara, A.C. , Xia, Y. , Hersh, M. , Stromberg, A.J. , Navarre, D. , Kachroo, A. and Kachroo, P. (2009) Enhanced disease susceptibility 1 and salicylic acid act redundantly to regulate resistance gene‐mediated signaling. PLoS Genet. 5, e1000545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C. , El‐Shetehy, M. , Shine, M.B. , Yu, K. , Navarre, D. , Wendehenne, D. , Kachroo, A. and Kachroo, P. (2014) Free radicals mediate systemic acquired resistance. Cell Rep. 7, 348–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F. , Hanna, M.A. and Sun, R. (2012) Value‐added uses for crude glycerol—a byproduct of biodiesel production. Biotechnol. Biofuels, 5, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, K. , Soares, J.M. , Mandal, M.K. , Wang, C. , Chanda, B. , Gifford, A.N. , Fowler J.S., Navarre, D. , Kachroo, A. and Kachroo, P. (2013) A feedback regulatory loop between G3P and lipid transfer proteins DIR1 and AZI1 mediates azelaic‐acid‐induced systemic immunity. Cell Rep. 3, 1266–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun, D.‐J. (1996) Plant antifungal proteins In: Plant Breeding Reviews, pp. 39–88. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley‐Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Zoeller, M. , Stingl, N. , Krischke, M. , Fekete, A. , Waller, F. , Berger, S. and Mueller, M.J. (2012) Lipid profiling of the Arabidopsis hypersensitive response reveals specific lipid peroxidation and fragmentation processes: biogenesis of pimelic and azelaic acid. Plant Physiol. 160, 365–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurbriggen, M.D. , Carrillo, N. and Hajirezaei, M.R. (2010) ROS signaling in the hypersensitive response: when, where and what for? Plant Signal Behav. 5, 393–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Putative PR‐1–PR‐5 genes identified in the cacao genome by the blastp algorithm.

Table S2 Primer sequences for SYBR Green assay of pathogenesis‐related (PR) genes analysed by reverse transcription‐quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT‐qPCR).