Summary

Sharp eyespot, caused mainly by the necrotrophic fungus Rhizoctonia cerealis, limits wheat production worldwide. Here, TaCPK7‐D, encoding a subgroup III member of the calcium‐dependent protein kinase (CPK) family, was identified from the sharp eyespot‐resistant wheat line CI12633 through comparative transcriptomic analysis. Subsequently, the defence role of TaCPK7‐D against R. cerealis infection was studied by the generation and characterization of TaCPK7‐D‐silenced and TaCPK7‐D‐overexpressing wheat plants. Rhizoctonia cerealis inoculation induced a higher transcriptional level of TaCPK7‐D in the resistant wheat line CI12633 than in the susceptible cultivar Wenmai 6. The expression of TaCPK7‐D was significantly induced after exogenous application of 1‐aminocyclopropane‐1‐carboxylic acid (an ethylene biosynthesis precursor). The green fluorescent protein signal distribution assays indicated that TaCPK7‐D localizes to the plasma membrane in both onion epidermal cells and wheat protoplasts. Following R. cerealis inoculation, TaCPK7‐D‐silenced wheat CI12633 plants displayed more severe sharp eyespot symptoms than control CI12633 plants. Four defence‐associated genes (β‐1,3‐glucanase, chitinase 1, defensin and TaPIE1) and an ethylene biosynthesis key gene, ACO2, were significantly suppressed in the TaCPK7‐D‐silenced wheat plants compared with control plants. Conversely, TaCPK7‐D‐overexpressing wheat lines showed increased resistance to sharp eyespot compared with untransformed recipient wheat Yangmai 16. Furthermore, the transcriptional levels of these four defence‐related genes and ACO2 gene were significantly elevated in TaCPK7‐D‐overexpressing plants compared with untransformed recipient wheat plants. These results suggest that TaCPK7‐D positively regulates the wheat resistance response to R. cerealis infection through the modulation of the expression of these defence‐associated genes, and that TaCPK7‐D is a candidate to improve sharp eyespot resistance in wheat.

Keywords: CPK gene TaCPK7‐D, overexpression, resistance, sharp eyespot, virus‐induced gene silencing, wheat

Introduction

Common wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) is one of the most important food grain sources for humans worldwide. Diseases heavily limit wheat production. Sharp eyespot, mainly caused by the necrotrophic fungus Rhizoctonia cerealis, is a soil‐borne destructive disease that considerably decreases wheat grain yield in some regions of the world. For example, in China, since 2005, wheat plants over at least 8 million ha have been subjected to sharp eyespot disease, resulting in yield losses of 10%–30% (Chen et al., 2013). The breeding and application of resistant wheat cultivars provide the most effective and environmentally safe approach for disease control. The efficiency of breeding depends on the availability of resistant accessions and on an understanding of the resistance genetics and underlying mechanisms. However, no sharp eyespot‐immune wheat cultivars/lines have been identified. The resistance in known wheat lines is quantitative and controlled by multiple loci (Cai et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2013). Thus, it is difficult to breed sharp eyespot‐resistant varieties using traditional methods. Genetic engineering provides an alternative approach to improve the defence responses to this disease. To address this challenge, it is vital to identify the genes that play important roles in the resistance response and to elucidate the mechanism underlying their defence roles.

Against pathogen infection, plants trigger defence responses following the recognition of pathogen‐associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) by cell surface pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and the sensing of effector proteins from pathogens via intracellular nucleotide‐binding leucine‐rich repeat (NB‐LRR) proteins. The changes in Ca2+ concentration in plant cells are generally believed to be one of the early intracellular reactions to biotic and abiotic stress, which are sensed and decoded by various Ca2+‐binding proteins and kinases, such as calcium‐dependent protein kinases (CPKs) (Harper et al., 2004). In plants, CPKs belong to a multi‐gene family, being divided into four subgroups (Boudsocq and Sheen, 2013). There are 34 CPK members in Arabidopsis (Cheng et al., 2002), 31 in rice (Asano et al., 2005), at least 20 in wheat (Li et al., 2008) and 30 in poplar (Populus trichocarpa, Zuo et al., 2013).

Accumulating evidence has shown that various CPK members modulate plant defence responses with either a positive or negative effect (Boudsocq and Sheen, 2013; Freymark et al., 2007; Romeis et al., 2001). For instance, NtCPK2, a tobacco CPK from subgroup I, was the first CPK identified to have a positive regulatory role in plant defence signalling (Romeis et al., 2001). In Arabidopsis, overexpression of AtCPK1 from subgroup I confers broad‐spectrum resistance to the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae and the necrotrophic fungal pathogens Botrytis cinerea and Fusarium oxysporum (Coca and Segundo, 2010). TaCPK2‐A, a wheat CPK from subgroup I, is required for wheat resistance to powdery mildew, caused by the biotrophic fungal pathogen Blumeria graminis f.sp. tritici. TaCPK2‐A overexpression in rice increases resistance to bacterial blight disease caused by Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Geng et al., 2013). Transgenic potato plants overexpressing StCPK5 from subgroup I show enhanced resistance to the hemibiotrophic pathogen Phytophthora infestans (Kobayashi et al., 2007). By contrast, in rice, OsCPK12 (a subgroup II CPK) and OsCPK18 (a subgroup IV member) negatively regulate the host defence response to the blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea through the repression of defence gene expression (Asano et al., 2012; Xie et al., 2014). An Arabidopsis subgroup IV member, CPK28, negatively regulates antibacterial immunity (Monaghan et al., 2014). Furthermore, the overexpression of certain CPK members results in concentration changes of phytohormones, such as salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA) and ethylene. For example, AtCPK1 overexpression elevates the accumulation of SA and the expression of downstream marker genes in the SA signalling pathway (Coca and Segundo, 2010). The overexpression of NtCPK2 induces the accumulation of ethylene and JA, but not SA (Ludwig et al., 2005). TaCPK2‐A overexpression in rice up‐regulates the marker genes in the JA signalling pathway (Geng et al., 2013). The above‐mentioned results suggest that CPKs mediate defence responses through the regulation of distinct phytohormone signalling pathways. Although the gene structure and transcriptional profiles of CPK members from common wheat have been investigated (Li et al., 2008), little is known about the function of the CPK family in common wheat because of its huge and complex genome.

In this study, TaCPK7‐D, a subgroup III CPK member in wheat, was identified through microarray‐based comparative transcriptomic analysis. On challenge with the necrotrophic fungus R. cerealis, TaCPK7‐D was more highly induced in sharp eyespot‐resistant wheat lines than in susceptible wheat lines. Following R. cerealis inoculation, silencing of TaCPK7‐D in the resistant wheat line CI12633 impaired host resistance to R. cerealis, whereas TaCPK7‐D overexpression increased the resistance level to sharp eyespot in transgenic wheat plants, suggesting that TaCPK7‐D positively regulates the wheat resistance response to R. cerealis infection. Transcriptional level analyses of defence‐associated genes in TaCPK7‐D‐silenced and TaCPK7‐D‐overexpressing wheat plants suggested that the positive defence regulation of TaCPK7‐D was associated with the modulation of the expression of the defence‐associated genes in wheat.

Results

Identification of TaCPK7‐D involvement in resistance to sharp eyespot disease

To isolate resistance response‐related genes of wheat to sharp eyespot disease, comparative transcriptomic assays were performed by microarray analysis. Among the differentially expressed transcripts between resistant line CI12633 and susceptible cultivar Wenmai 6 at the same time point (microarray raw data, GEO accession number GSE69245), the probe TC411941 showed 1.8‐, 2.4‐ and 1.8‐fold transcriptional increases in CI12633 than in Wenmai 6 at 4, 7 and 21 days post‐inoculation (dpi), respectively. Sequence analysis indicated that the sequence of TC411941 is homologous to that of TaCPK7 (GenBank accession no. EU181192). The sequence alignment with the chromosome‐based draft sequence of the bread wheat (Triticum aestivum cultivar Chinese Spring) genome (http://www.wheatgenome.org/) [The International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium (IWGSC), 2014] revealed that TC411941 was located on wheat chromosome 2DS. To verify this alignment on the chromosome, genomic DNAs extracted from Triticum urartu (AA), Aegilops tauschii (DD), Triticum aestivum (AABBDD) and Chinese Spring Nulli‐tetrasomic lines (NT) were used as templates for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) employing the TC411941‐specific primers (TaCPK7D‐QF and TaCPK7D‐QR) to study the chromosome location of the gene. The results proved that the gene corresponding to TC411941 was indeed located on chromosome 2D of wheat (Fig. 1A). Thus, this gene represented by TC411941 was designated as TaCPK7‐D.

Figure 1.

Chromosome location and transcriptional analyses of TaCPK7‐D in wheat lines infected with Rhizoctonia cerealis. (A) Chromosome location of TaCPK7‐D. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay using TaCPK7‐D gene‐specific primers showed that TaCPK7‐D is located on chromosome 2D. (B) Quantitative reverse transcription‐PCR (qRT‐PCR) analysis between resistant wheat line CI12633 and susceptible wheat cultivar Wenmai 6 on challenge with R. cerealis. Total RNA was extracted from the stems of wheat plants at 4, 7 and 21 days post‐inoculation (dpi) with R. cerealis. (C) Fold change of TaCPK7‐D in wheat tissues at 21 dpi with R. cerealis. Total RNA was extracted from root, stem, leaf and spike tissues of CI12633. (D) qRT‐PCR analysis of TaCPK7‐D in five wheat cultivars with different defence responses to sharp eyespot at 21 dpi with R. cerealis. Total RNA was extracted from the stems of five wheat cultivars. DI indicates the disease index of sharp eyespot. The transcript levels were normalized to the wheat actin gene. Significant differences were analysed based on the results of three replications (Student's t‐test: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). Error bars indicate standard error.

Quantitative reverse transcription‐PCR (qRT‐PCR) analyses showed that the transcriptional levels of TaCPK7‐D were significantly higher in resistant wheat CI12633 than in susceptible wheat Wenmai 6 at 4, 7 or 21 dpi with R. cerealis (Fig. 1B), and the expression trend of the gene was consistent with that in the microarray analysis. Transcriptional levels of TaCPK7‐D in root, stem and spike tissues of CI12633 were significantly induced by R. cerealis, with the induction in the stems being the most drastic (Fig. 1C). Moreover, based on the transcriptional analyses in five wheat lines with different resistance levels to sharp eyespot at 21 dpi by qRT‐PCR (Fig. 1D), the transcriptional levels were associated with the resistance levels to sharp eyespot disease. These results imply that TaCPK7‐D might play a positive role in the wheat resistance response to R. cerealis infection.

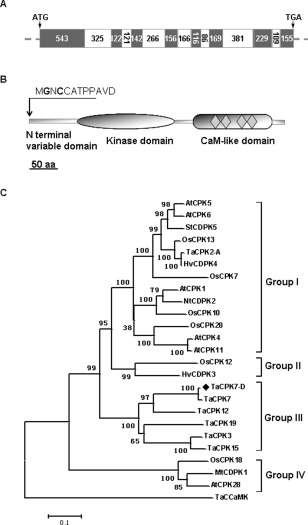

TaCPK7‐D encodes a subgroup III CPK protein

The full‐length cDNA sequence (GenBank accession no. KT749894) and genomic sequence of TaCPK7‐D were cloned from stem cDNA and genomic DNA of R. cerealis‐infected wheat line CI12633, respectively. The alignment of the cDNA and genomic sequences revealed that the gene structure consisted of eight exons and seven introns (Fig. 2A). The full‐length cDNA of TaCPK7‐D contains a 1632‐bp open reading frame (ORF), which encodes the TaCPK7‐D protein with 543 amino acid residues. The TaCPK7‐D protein sequence possesses the typical characteristics of CPKs, and contains an N‐terminal variable domain, a catalytic serine/threonine protein kinase domain and a calmodulin (CaM)‐like domain in the C‐terminus (Fig. 2B). Phylogenetic analysis of the TaCPK7‐D protein and known CPK proteins involved in defence responses showed that TaCPK7‐D fell into a cluster with TaCPK3, TaCPK7, TaCPK9, TaCPK12 and TaCPK15 from wheat, all of which belong to subgroup III of the CPK family (Fig. 2C). These results reveal that TaCPK7‐D is a subgroup III CPK member.

Figure 2.

Structural scheme and phylogenetic tree analysis of TaCPK7‐D. (A) Genomic structure of TaCPK7‐D; dark grey and white portions indicate exons and introns, respectively. The numbers in the boxes indicate the nucleotide numbers of each portion. ATG and TGA are the start codon and stop codon, respectively. (B) Protein structure of TaCPK7‐D has the typical domains of plant calcium‐dependent protein kinase (CPK), including an N‐terminal variable domain, a kinase catalytic domain and a calmodulin (CaM)‐like domain with four calcium‐binding motifs (rhombi in the calmodulin domain). The N‐terminal amino acid sequence of TaCPK7‐D is indicated at the top. (C) Reconstruction of the phylogenetic tree based on the amino acids of putative TaCPK7‐D and known CPK members involved in defence responses from several plant species.

TaCPK7‐D is induced by ethylene stimulus

The responses of TaCPK7‐D to treatments with exogenous phytohormones, including ethylene, SA and methyl JA (MeJA), were examined by qRT‐PCR. The results showed that TaCPK7‐D transcription was significantly induced by an ethylene biosynthesis precursor 1‐aminocyclopropane‐1‐carboxylic acid (ACC), but not significantly induced by SA and MeJA at 1 and 6 h post‐treatment (Fig. 3A). Subsequently, TaCPK7‐D transcriptional levels were further examined after treatments with ACC or CoCl2 (an ethylene biosynthesis inhibitor) at further time points, including 0, 1, 3, 6 and 12 h. The expression level of TaCPK7‐D was significantly elevated after ACC treatment with a peak at 1 h (Fig. 3B), but was significantly suppressed after CoCl2 treatment (Fig. 3C), implying that TaCPK7‐D is positively regulated by ethylene.

Figure 3.

Expression of TaCPK7‐D in leaves of wheat seedlings in response to exogenous applications of hormones and an ethylene biosynthesis inhibitor. Wheat Yangmai 16 plants at the three‐leaf stage were sprayed with 1.0 mm salicylic acid (SA), 50 μm l‐aminocyclopropane‐l‐carboxylic acid (ACC, an ethylene biosynthesis precursor), 0.1 mm CoCl2 (an ethylene biosynthesis inhibitor), 0.1 mm methyl jasmonate (MeJA) and 0.1% Tween‐20 (as a control), and the samples were collected at 0, 1, 3, 6 and 12 h after treatment. The transcript levels of TaCPK7‐D in wheat plants treated with Tween‐20 (A) or collected at 0 h (B, C) were set to unity. Values represent the average ± standard error of three replicates (Student's t‐test: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

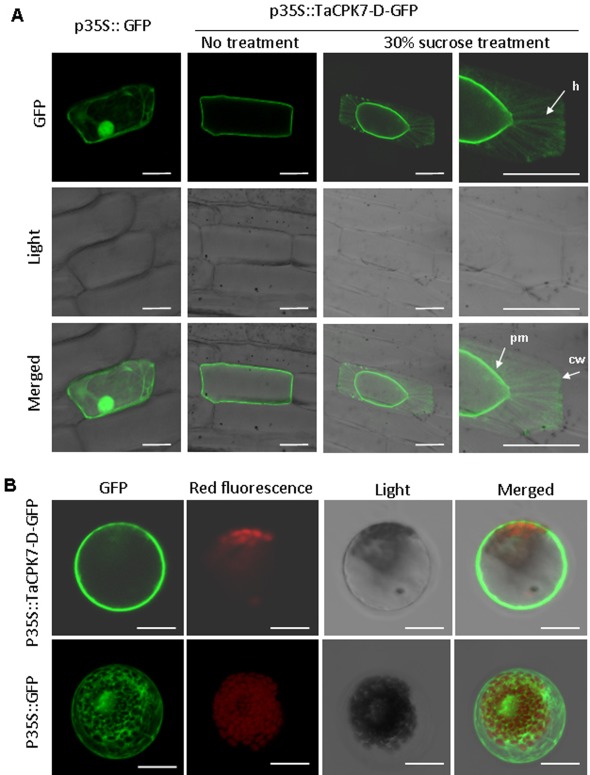

TaCPK7‐D localizes to the plasma membrane

Sequence analysis showed that the protein TaCPK7‐D possesses a predicted N‐myristoylation site (Gly‐2) and a palmitoylation site (Cys‐4), both of which are involved in targeting the plasma membrane (Fig. 2B). To verify the predicted results, subcellular localization assays of TaCPK7‐D were performed. The p35S:TaCPK7‐D‐GFP fusion construct was introduced into and expressed in onion epidermal cells or wheat mesophyll protoplasts; the p35S:GFP construct was used as the control. Confocal microscopic observations showed that TaCPK7‐D‐GFP localized to the onion epidermal cell periphery, probably the plasma membrane (Fig. 4A). After the onion epidermal cells had been plasmolysed, thin plasma membrane bridges, known as Hechtian strands (Campo et al., 2014), were shown in the protoplasts that were pulled away from the cell wall (Fig. 4A), clearly indicating the plasma membrane localization of TaCPK7‐D. As expected, green fluorescent protein (GFP) alone was distributed in the entire cytoplasm and nucleus (Fig. 4A). Subcellular localization assay in wheat mesophyll protoplasts further confirmed that the TaCPK7‐D‐GFP fusion protein was expressed and localized in the plasma membrane in wheat (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Plasma membrane localization of TaCPK7‐D. (A) Onion epidermal cells were transformed with TaCPK7‐D‐GFP or green fluorescent protein (GFP) alone via particle bombardment. Confocal images were taken at 12 h after bombardment. After the onion epidermal cells transformed with TaCPK7‐D‐GFP had been plasmolysed by 30% sucrose treatment for 15 min, confocal images showed the shrinkage of the protoplast. The Hechtian strands (h) attaching the plasma membrane (pm) to the cell wall (cw) clearly appear in the higher magnification of a plasmolysed onion cell. (B) Wheat protoplasts were transformed with TaCPK7‐D‐GFP or GFP alone via the polyethylene glycol (PEG)‐mediated method. TaCPK7‐D is localized to the plasma membrane in wheat protoplasts. Images were captured using the following wavelengths (excitation, 488 nm; emission, 509 nm) and chlorophyll autofluoresence (excitation, 448 nm; emission, 647 nm) Bars, 50 μm.

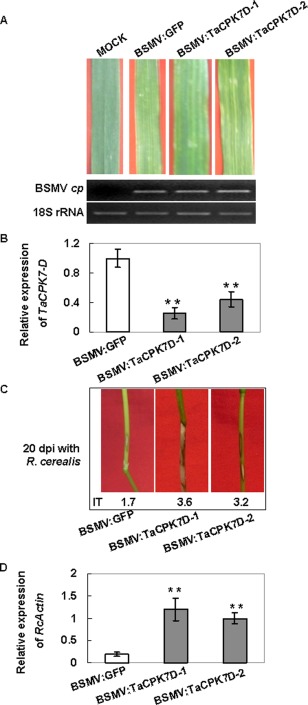

TaCPK7‐D is required for wheat resistance to sharp eyespot

The virus‐induced gene silencing (VIGS) assay in barley and wheat was developed using the Barley stripe mosaic virus (BSMV) (Holzberg et al., 2002; Scofield et al., 2005). The BSMV‐based VIGS has been shown to be an effective reverse genetic tool for the rapid investigation of the functions of genes (Scofield et al., 2005; Zhou et al., 2007; Zhu et al., 2014). As TaCPK7‐D was induced after challenge with R. cerealis, BSMV‐VIGS assay was performed to investigate whether the silencing of TaCPK7‐D impairs wheat resistance to sharp eyespot. The gene‐specific fragment (length, 244 bp) spanning the 3′ terminal ORF and the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of TaCPK7‐D was selected to construct the recombinant virus BSMV:TaCPK7‐D. Via inoculation with the RNAs of the recombinant BSMV:TaCPK7‐D virus onto the second leaves of CI12633, TaCPK7‐D‐silenced plants were generated. After virus infection for 14 days, the leaves of the infected wheat plants exhibited typical BSMV infection symptoms, and the transcript of the BSMV coat protein (cp) gene was readily detected (Fig. 5A), suggesting that BSMV had successfully infected these wheat plants. As expected, qRT‐PCR results showed that the transcript of TaCPK7‐D was significantly suppressed in BSMV:TaCPK7‐D‐infected CI12633 plants (namely TaCPK7‐D‐silenced plants) compared with the BSMV:GFP‐infected CI12633 plants (control) (Fig. 5B). Following inoculation with R. cerealis for 20 days, the TaCPK7‐D‐silenced plants exhibited more severe symptoms of sharp eyespot than did control plants (Fig. 5C). Rhizoctonia cerealis relative biomass was detected by qRT‐PCR based on the relative expression level of the R. cerealis actin gene (Chacón et al., 2010; Zhu et al., 2014). The results showed that R. cerealis relative biomass was significantly higher in TaCPK7‐D‐silenced CI12633 plants than in controls (Fig. 5D). These results suggest that TaCPK7‐D is required for resistance to R. cerealis in wheat line CI12633.

Figure 5.

Responses to Rhizoctonia cerealis inoculation of TaCPK7‐D‐silenced wheat CI12633 plants. (A) Phenotypes of wheat CI12633 plants infected with BSMV:TaCPK7‐D or BSMV:GFP (control) showing typical striped mosaic virus symptoms. The Barley stripe mosaic virus (BSMV) coat protein gene (cp) was detected by reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR); wheat 18S rRNA was used as an internal control for normalization. (B) Quantitative RT‐PCR analysis of TaCPK7‐D in TaCPK7‐D‐silenced plants and control CI12633 plants. Total RNAs were extracted from the stems of CI12633 infected with BSMV. The relative transcript level of TaCPK7‐D in silenced lines was compared with that in control CI12633 plants (set to unity). (C) Typical sharp eyespot phenotypes of TaCPK7‐D‐silenced CI12633 plants and control CI12633 plants at 20 days after R. cerealis inoculation. IT indicates infection type of R. cerealis. (D) Quantitative RT‐PCR analysis of R. cerealis actin gene in TaCPK7‐D‐silenced plants and control CI12633 plants representing the biomass of R. cerealis. The RNA samples were the same as those used for TaCPK7‐D quantification in (B). Values represent the average ± standard error of three replicates (Student's t‐test: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

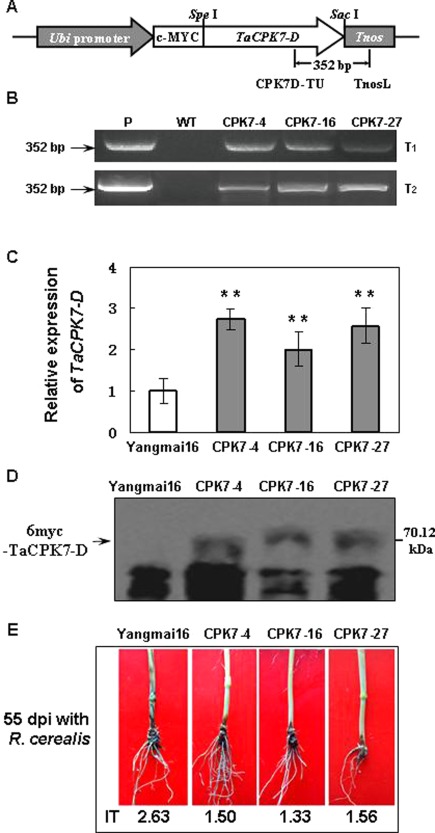

Overexpression of TaCPK7‐D enhances wheat resistance to sharp eyespot

To further explore the defence role of TaCPK7‐D in wheat, TaCPK7‐D‐overexpressing transgenic wheat plants were generated via bombardment of the TaCPK7‐D expression vector pA25‐myc‐TaCPK7‐D (Fig. 6A) into 1200 immature embryos of the wheat cultivar Yangmai 16. The presence of transgenic TaCPK7‐D was detected by the desired PCR product (352 bp) using TaCPK7‐D transgene‐specific primer pairs (Fig. 6B). Three independent transgenic lines, namely CPK7‐4, CPK7‐16 and CPK7‐27, were selected for further research. qRT‐PCR analysis showed that the expression of TaCPK7‐D was significantly elevated in these three TaCPK7‐D‐overexpressing lines compared with untransformed Yangmai 16 (wild‐type, WT) plants (Fig. 6C). Western blotting indicated that the introduced myc‐TaCPK7‐D fusion protein was expressed in these three transgenic wheat lines (Fig. 6D). The R. cerealis responses of TaCPK7‐D‐overexpressing lines in T1 and T2 generations were evaluated following R. cerealis inoculation. The results showed that these three TaCPK7‐D‐overexpressing lines (CPK7‐4, CPK7‐16 and CPK7‐27) exhibited significantly elevated resistance compared with untransformed Yangmai 16 (Fig. 6E). The average disease indices of these three TaCPK7‐D‐overexpressing lines (CPK7‐4, CPK7‐16 and CPK7‐27) in the T1 generation were 20.00, 27.22 and 32.57, respectively, whereas that of untransformed Yangmai 16 was 42.17. In the T2 generation of the three transgenic wheat lines, the average disease indices were 30.00, 26.67 and 31.11, respectively, whereas that of untransformed Yangmai 16 was 52.63. The results indicate that TaCPK7‐D positively regulates the wheat defence response to sharp eyespot.

Figure 6.

Molecular characterization of TaCPK7‐D‐overexpressing wheat plants and responses to Rhizoctonia cerealis inoculation. (A) Scheme of the TaCPK7‐D expression cassette of the transformation vector pA25‐myc‐TaCPK7‐D. Ubi promoter, maize ubiquitin promoter; Tnos, terminator of Agrobacterium tumefaciens nopaline synthase gene. The arrows indicate the amplified regions of transgenic wheat plants by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). (B) PCR patterns of the TaCPK7‐D‐overexpressing wheat lines in the T1 and T2 generations using the primers specific to the TaCPK7‐D‐Tnos cassette. P, transformation vector pA25‐myc‐TaCPK7‐D; WT, untransformed Yangmai 16. (C) Relative expression levels of TaCPK7‐D in the three overexpressing wheat lines and untransformed Yangmai 16. The relative transcript levels of TaCPK7‐D in the three transgenic wheat lines were compared with that of untransformed Yangmai 16 (set to unity). (D) Western blotting analysis of the three TaCPK7‐D‐overexpressing wheat lines and untransformed Yangmai 16 using an anti‐myc antibody. (E) Typical sharp eyespot symptoms of TaCPK7‐D‐overexpressing plants and untransformed Yangmai 16 plants at 55 days after R. cerealis inoculation. Values represent the average ± standard error of three technical replicates (Student's t‐test: *P < 0.05, **P <0.01).

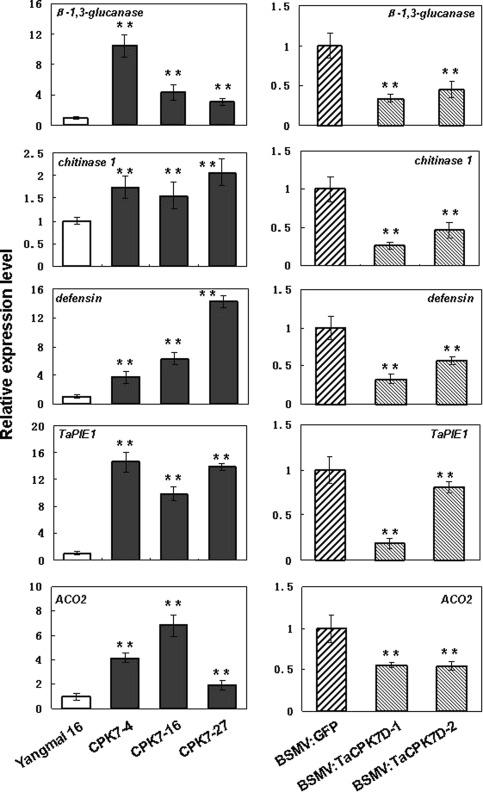

TaCPK7‐D regulates the expression of defence‐associated and ethylene biosynthesis genes

To investigate the potential mechanism of the TaCPK7‐D‐mediated resistance response in wheat, we analysed the transcript levels of some defence‐associated genes by qRT‐PCR in TaCPK7‐D‐overexpressing, TaCPK7‐D‐silenced and control wheat lines after R. cerealis inoculation. The tested genes included the β‐1,3‐glucanase gene, belonging to the pathogenesis‐related (PR)−2 family (Liu et al., 2009), chitinase 1, belonging to the PR‐3 family (Chen et al., 2008), defensin, belonging to the PR‐12 family, and an ERF transcription factor gene TaPIE1, as well as an ACC oxidase gene ACO2. The results showed that the transcriptional levels of these defence‐related genes, β‐1,3‐glucanase, chitinase 1, defensin, TaPIE1 and ACO2, were significantly higher in the TaCPK7‐D‐overexpressing lines than in untransformed Yangmai 16, whereas they were significantly lower in TaCPK7‐D‐silenced plants than in BSMV:GFP‐infected control plants (Fig. 7). These results suggest that TaCPK7‐D positively regulates the transcription of these defence‐associated genes and ACO2 gene.

Figure 7.

Expression of defence‐associated genes and ethylene signalling‐related genes in TaCPK7‐D‐overexpressing wheat lines and TaCPK7‐D‐silenced wheat plants by quantitative reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction (qRT‐PCR). The transcript levels of these genes in TaCPK7‐D‐overexpressing wheat lines in the T2 generation are relative to those in untransformed Yangmai 16 at 55 days post‐inoculation (dpi) with Rhizoctonia cerealis, whereas the levels in TaCPK7‐D‐silenced wheat plants are relative to those in the control plants [infected with Barley stripe mosaic virus:green fluorescent protein (BSMV:GFP)] at 10 dpi with R. cerealis. Values represent the average ± standard error of three technical replicates (Student's t‐test: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

Discussion

Soil‐borne fungal diseases, such as sharp eyespot, seriously limit wheat production worldwide (Cai et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2013). The huge size and great complexity of the wheat genome, as well as the low transformation efficiency, have largely hampered research advances in functional genomics and resistance improvements. The characterization of defence response‐related genes in wheat is critical for the development of wheat varieties with resistance to soil‐borne fungal diseases. CPKs constitute a large multi‐gene family, being divided into four groups. So far, CPK members implicated in plant resistance responses (Asano et al., 2012; Coca and Segundo, 2010; Geng et al., 2013; Kobayashi et al., 2007; Monaghan et al., 2014; Romeis et al., 2001; Xie et al., 2014) have been assigned to subgroups I, II or IV (Fig. 2B). In this study, a CPK subgroup III member, TaCPK7‐D, was identified based on differential transcriptomic analysis through microarray assay, and cloned from the sharp eyespot‐resistant wheat line CI12633. Furthermore, its functional role in wheat resistance to sharp eyespot was studied in TaCPK7‐D‐overexpressing and TaCPK7‐D‐silenced wheat plants. In TaCPK7‐D‐overexpressing wheat plants, the defence response against R. cerealis was enhanced compared with that of untransformed wheat (Fig. 6B). Conversely, in TaCPK7‐D‐silenced wheat CI12633 plants, resistance was impaired (Fig. 5B). There results suggest that TaCPK7‐D is a positive regulator of the defence response to R. cerealis infection.

The transcriptional level of TaCPK7‐D was higher in the R. cerealis‐resistant wheat line CI12633 than in the susceptible wheat cultivar Wenmai 6 on inoculation with R. cerealis. The qRT‐PCR results were consistent with the microarray analysis data (Fig. 1B). Moreover, TaCPK7‐D transcriptional levels were coincident with the resistance response to sharp eyespot disease in five wheat cultivars/lines with different defence levels (Fig. 1D), suggesting that TaCPK7‐D positively participates in the wheat defence response to R. cerealis. Phylogenetic analysis showed that the TaCPK7‐D protein belongs to subgroup III of the CPK family (Fig. 2C). To date, the well‐characterized CPK members modulating plant defence responses mainly belong to subgroup I, with fewer identified from subgroups II and IV. TaCPK7‐D is the first reported member from CPK subgroup III that participates in plant resistance responses.

Previous studies have shown that the majority of CPK members are membrane anchored (Boudsocq and Sheen, 2013). Sequence analysis has shown that TaCPK7‐D has a predicted N‐myristoylation site and a palmitoylation site that are involved in targeting the membrane. In AtCPK28, the G2 residue at the N‐terminal myristoylation motif is critical for its location to the plasma membrane (Monaghan et al., 2014). Our experimental evidence confirms that TaCPK7‐D is localized to the plasma membrane in both onion epidermal cells and wheat protoplasts (Fig. 4A,B). The membrane localization may be correlated with the function of CPKs in Ca2+ sensing and defence signal propagation.

In this study, TaCPK7‐D‐overexpressing wheat plants showed enhanced resistance to the necrotrophic pathogen R. cerealis (Fig. 6B). Conversely, the resistance level in TaCPK7‐D‐silenced wheat CI12633 plants was significantly reduced (Fig. 5C,D). Various PR proteins play important roles in plant defence responses to distinct pathogens. The precise transcriptional regulation of a battery of genes encoding diverse molecules in these plant processes determines plant resistance or susceptibility (Somssich and Hahlbrock, 1998). In our study, the transcriptional levels of defence‐related genes, including β‐1,3‐glucanase, chitinase 1 and defensin, were elevated in TaCPK7‐D‐overexpressing plants compared with untransformed wheat, whereas the transcriptional levels were lower in TaCPK7‐D‐silenced wheat plants than in control plants (Fig. 7). A previous study has shown that the tested β‐1,3‐glucanase possesses inhibitory activity against R. cerealis growth (Liu et al., 2009). Overexpression of a Thinopyrum intermedium ERF gene TiERF1 increased the resistance of transgenic wheat o R. cerealis through the up‐regulation of the chitinase 1 and β‐1,3‐glucanase expression level (Chen et al., 2008). The elevated transcript levels of chitinase 2 and defensin in TaPIE1‐overexpressing transgenic wheat resulted in enhanced resistance to sharp eyespot disease (Zhu et al., 2014). Thus, the overexpression of TaCPK7‐D increases the expression of these defence‐related genes, such as β‐1,3‐glucanase, chitinase 1 and defensin, resulting in enhanced resistance to R. cerealis in transgenic wheat.

In TaCPK7‐D‐overexpressing wheat plants, ACO2 and TaPIE1 showed higher transcriptional levels than in untransformed plants, whereas both genes exhibited opposite transcriptional trends in TaCPK7‐D‐silenced wheat compared with control plants (Fig. 7). ACO2 is a key enzyme in ethylene biosynthesis and can convert ACC to ethylene (Wang et al., 2002). TaPIE1 has been shown to be involved in the ethylene signalling pathway, and to play a positive role in wheat resistance to R. cerealis (Zhu et al., 2014). In addition, the tested β‐1,3‐glucanase, chitinase 1 and defensin are downstream genes in the ethylene signalling pathway (Chen et al., 2008; Ludwig et al., 2005; Zhu et al., 2014). Considering the fact that TaCPK7‐D expression was induced by exogenous ACC (an ethylene biosynthesis precursor) and was suppressed by CoCl2 (an ethylene biosynthesis inhibitor), these results may suggest that the resistance role of TaCPK7‐D may modulate the expression of the defence‐associated genes in the ethylene signalling pathway. The underlying mechanism needs to be explored in future.

In summary, TaCPK7‐D, a wheat CPK member of subgroup III, was identified to be required for wheat defence to R. cerealis infection. The TaCPK7‐D protein localizes to the plasma membrane in wheat protoplast cells. On R. cerealis infection, TaCPK7‐D expression was up‐regulated. TaCPK7‐D overexpression might activate defence‐related genes, leading to enhanced resistance to sharp eyespot caused by R. cerealis. This study has increased our understanding of CPK members of subgroup III in plant defence responses, and has provided a potential gene, TaCPK7‐D, for efforts to improve wheat resistance to sharp eyespot.

Experimental Procedures

Plant materials, pathogen fungus and treatments

Six wheat cultivars, including CI12633, Niavt 14, Yangmai 158, Yangmai 16, Zhoumai16 and Wenmai 6, were used in this study. CI12633 and Niavt 14 are resistant to R. cerealis infection. Yangmai 158 and Yangmai 16 are moderately susceptible to R. cerealis. Zhoumai16 and Wenmai 6 are highly susceptible. As a commercial wheat cultivar, Yangmai 16 was used as the recipient of TaCPK7‐D transformation. Wheat plants were grown in a glasshouse with a 14 h light, 23 ºC/10 h dark, 13 ºC regime. The R. cerealis isolate R0301 is the dominant strain in Jiangsu Province, China, and was provided by Professors Huaigu Chen and Shibin Cai, Jiangsu Academy of Agricultural Sciences, China.

For exogenous hormone treatments, Yangmai 16 wheat plants at the three‐leaf stage were sprayed with 1.0 mm SA, 50 μm ACC (an ethylene biosynthesis precursor), 0.1 mm CoCl2 (an ethylene biosynthesis inhibitor) and 0.1 mm MeJA, all of which were dissolved in 0.1% Tween‐20, and 0.1% Tween‐20 (as a control). The leaves were collected at 0, 1, 3, 6 and 12 h after treatment.

DNA and RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Genomic DNA was extracted using the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method (Saghai‐Maroof et al., 1984). Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and subjected to RNase‐free DNase I (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) digestion and purification according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Five micrograms of purified RNA from each sample were used as template for the synthesis of first‐strand cDNA employing the Superscript II 1st‐strand synthesis kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cloning and sequence analysis of TaCPK7‐D

The microarray analysis indicated that a probe (TIGR number: TC411941) of the Agilent wheat microarray, the 3′‐terminal partial sequence of TaCPK7‐D cDNA, was expressed at a significantly higher level in resistant wheat CI12633 than in susceptible wheat Wenmai 6. TC411941 was homologous to a wheat gene TaCPK7 (GenBank accession EU181192) in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database. The 3′ UTR and full‐length ORF sequences of TaCPK7‐D were separately amplified using a 3′‐Full RACE (rapid amplification of cDNA ends) Core Set kit v.2.0 (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) and nested RT‐PCR from cDNA of CI12633 stems inoculated with R. cerealis at 4 dpi. The genomic DNA sequence of TaCPK7‐D was amplified from genomic DNA of CI12633 stems. The PCR products obtained were cloned into the pMD‐18T vector (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). At least five positive clones were sequenced with an ABI PRISM 3130XL Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The cDNA sequences were analysed using blast (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) and ORF Finder (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gorf/). dnaman software was used for sequence alignment. InterPro‐Scan (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/) and Smart software (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/smart/set_mode.cgi) were employed for the prediction of the conserved domains and motifs. mega 5.0 software was used to construct the phylogenetic tree.

Subcellular localization of TaCPK7‐D

The coding region of TaCPK7‐D without the stop codon was amplified using gene‐specific primers with PstI and XbaI restriction sites, and was subcloned in‐frame to the N‐terminus of the GFP sequence in the pJIT163:GFP vector, generating the TaCPK7‐D‐GFP fusion construct p35S:TaCPK7‐D‐GFP. For onion epidermal cell assay, p35S:TaCPK7‐D‐GFP or p35S:GFP construct was separately bombarded into onion epidermal cells following Zhang et al. (2007). To confirm plasma membrane localization in onion, cells were plasmolysed with 30% sucrose for 15 min. For wheat protoplast assay, the TaCPK7‐D‐GFP fusion construct or GFP alone was separately introduced into wheat protoplasts via the PEG‐mediated transfection method following Yoo et al. (2007). The transformed onion epidermal cells or wheat protoplast cells were incubated at 25 ºC for 15 h. The GFP signals were observed and photographed using confocal laser scanning microscopy (Zeiss LSM 700, Göttingen, Germany) with a Fluar 10×/0.50 M27 objective lens and SP640 filter.

VIGS assay of TaCPK7‐D

BSMV was used for VIGS assay. A 244‐bp fragment from the TaCPK7‐D cDNA sequence, containing 106 bp of the 3′ ORF and 138 bp of the 3′ UTR sequence, was ligated into the γ chain in antisense orientation, resulting in γ:TaCPK7‐D. The recombinant virus BSMV:TaCPK7‐D consists of γ:TaCPK7‐D, and α and β chains of the BSMV genome. The transcript product of the recombinant virus was inoculated onto the leaves of sharp eyespot‐resistant wheat line CI12633 according to the protocol of Zhou et al. (2007). Briefly, the virus was inoculated on the second leaf of CI12633 plants at the two‐leaf stage; BSMV:GFP‐infected CI12633 was used as a control. The inoculated plants were grown at 90% relative humidity for at least 3 days in a 13 ºC, dark for 14 h/24 ºC, light for 10 h regime in a glasshouse, and then grown under natural conditions. BSMV:TaCPK7‐D‐infected plants or control plants at 20 days after virus infection were inoculated with R. cerealis‐colonized wheat kernels in contact with the plant stem base for the assessment of the TaCPK7‐D defence role in R. cerealis infection.

TaCPK7‐D expression construct and wheat transformation

The TaCPK7‐D ORF sequence was subcloned into the SpeI and SacI sites of the modified monocot expression vector pAHC25 (Christensen and Quail, 1996) with a 6 × myc epitope tag, resulting in the transformation vector pA25‐myc‐TaCPK7‐D. In the transformation vector, TaCPK7‐D is fused with the C‐terminal of the 6 × Myc tag, and the myc‐TaCPK7‐D fusion protein gene is driven by the maize ubiquitin promoter and the terminator of nopaline synthase (Tnos) gene. According to the procedure described by Xu et al. (2001) and Chen et al. (2008), a total of 1200 immature embryos of Yangmai 16 were transformed by biolistic bombardment using pA25‐TaCPK7‐D.

PCR detection and western blot analyses of transgenic wheat

The presence of the introduced TaCPK7‐D in transgenic wheat plants in T0–T2 generations was detected by PCR analysis of leaf genomic DNA employing the primers CPK7D‐TU (located in the TaCPK7‐D coding sequence) and TnosL (located in the Tnos sequence). PCR was performed in a total volume of 20 μL containing 1 × Taq buffer, 1.5 mm Mg2+, 0.05 mm of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP); 0.4 mm of each primer, 1 U of Taq polymerase (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) and 50 ng of template DNA, with an initial denaturation at 94 ºC for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94 ºC for 45 s, 54 ºC for 45 s and 72 ºC for 45 s, with a final extension at 72 ºC for 10 min. The amplified products were resolved on a 1.5% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide straining. The untransformed Yangmai 16 and pA25‐myc‐TaCPK7‐D plasmid DNA were used as negative control and positive control, respectively.

The expression of myc‐TaCPK7‐D fusion protein in transgenic wheat plants was tested by western blotting analysis. Total proteins were extracted from 0.3 g of ground leaf powder. Total soluble proteins (∼12 μg) for each transgenic line were separated by 12% sodium dodecylsulfate‐polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS‐PAGE) and transferred to polyvinyl difluoride membranes (Amersham, Pittsburgh, Germany). The western blots were incubated with 100‐fold diluted anti‐c‐myc antibody and secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Little Chalfont, UK). The 6 × myc‐TaCPK7‐D protein in these lines was visualized using the ECL Western Blot Detection and Analysis System (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Little Chalfont, UK).

Transcriptional analysis on target genes

qRT‐PCR was used to investigate the transcription of TaCPK7‐D and four other wheat genes, including β‐1,3‐glucanase (Genbank No. AF112965), chitinase 1 (Genbank No. CA665185), defensin (Genbank No. CA630387) and TaPIE1 (Genbank No. EF583940), as well as the ACC oxidase 2 gene (ACO2, Genbank No. AK332340). qRT‐PCR was performed using SYBR Green I Master Mix (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) in a volume of 25 μL on an ABI 7300 RT‐PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Reactions were set up with the following thermal profile: 95 ºC for 5 min, followed by 45 cycles of 95 ºC for 15 s and 60 ºC for 31 s, and completed with a melting curve analysis program. All qRT‐PCRs were technically repeated three times. The relative transcription levels of TaCPK7‐D and four other genes were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001), where the wheat actin gene was used to normalize the amounts of cDNA among the samples.

Rhizoctonia cerealis inoculation and assessment of transgenic wheat responses

At the early stem extension stage, at least 10 plants of each line of the TaCPK7‐D‐overexpressing transgenic and WT wheat were inoculated. Each plant stem base was contacted with 8–10 wheat kernels harbouring R. cerealis mycelia. The disease ratings of the wheat plants were evaluated at 55 dpi. Infection types (ITs) were categorized from 0 to 5 based on the lesion squares on the base stems. The disease indices (DIs) for each line were scored following Chen et al. (2008). The sequences of the primers are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers used in this study.

| Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) | Usage |

|---|---|---|

| TaCPK7D‐FL‐F | GGTCTGGTCGGCTCCGCTGTCTTT | Amplifying full‐length of TaCPK7‐D |

| TaCPK7D‐FL‐R | TTGCCTATTGCGTTATCATCTACT | |

| TaCPK7D‐FL‐nF | TGTCTTTTTTCCTGATTCGG | |

| TaCPK7D‐FL‐nR | CTATTGGGTACTTGTTATCTGC | |

| TaCPK7D‐3RACE‐F | AAGACCTTGTCAGGGGAATG | 3′RACE assay |

| TaCPK7D‐3RACE‐nF | TTTGGATACTTTGATCGGAACA | |

| TaCPK7D‐chrm‐F | CAAAGATCATACCTGGTAAACT | Chromosome location of TaCPK7‐D |

| TaCPK7D‐chrm‐R | CGTAGTAATATGTAGAAAGTGCAC | |

| TaCPK7D‐GFP‐SalI‐F | TATGTCGACATGGGCAACTGCTGCG | Subcellular location assay |

| TaCPK7D‐GFP‐BamHI‐R | GTCGGATCCTTGGGTACTTGTTATCT | |

| TaCPK7D‐Nhe1F | CGAGCTAGCAACCGACTGGAGGAAAGCC | Construction of VIGS vector BSMV:TaCPK7‐D |

| TaCPK7D‐Nhe1R | GCTGCTAGCCATCAGGATACCAAGCGGAAA | |

| BSMV‐CP‐F | TGACTGCTAAGGGTGGAGGA | RT‐PCR for BSMV‐CP transcript |

| BSMV‐CP‐R | CGGTTGAACATCACGAAGAGT | |

| TaCPK7D‐Trs‐F | AACTCGGTATCTAGAATGGGCAACTGCTGCGC | Construction of transformation vector |

| TaCPK7D‐Trs‐R | CGATCGGGGAAATTCCTATTGCGTTATCATCTA | |

| CPK7D‐TU | ATTAGAGTCCCGCAATTATACAT | Detection of transgenic plants |

| TnosL | ATGTATAATTGCGGGACTCTAAT | |

| TaCPK7D‐QF | TTCTTTGTGGTGTCCCTCC | qRT‐PCR of TaCPK7‐D |

| TaCPK7D‐QR | GCTGTCAAACGCCTCCTT | |

| TaActin‐F | CACTGGAATGGTCAAGGCTG | qRT‐PCR of TaActin |

| TaActin‐R | CTCCATGTCATCCCAGTTG | |

| R.C actin‐F | GCATCCACGAGACCACTTAC | qRT‐PCR of Actin of R. cerealis |

| R.C actin‐R | GCGTCCCGCTGCTCAAGAT | |

| Glucanase‐QF | CCGCACAAGACACCTCAAGATA | qRT‐PCR of β‐1,3‐glucanase |

| Glucanase‐QR | CGATGCCCTTGGTTTGGTAGA | |

| ACO2‐QF | GAGGAACGAGGGCGAGGAG | qRT‐PCR of ACO2 |

| ACO2‐QR | TCAGTTATCAGGCGGTGGC | |

| TaPIE1‐QF | GGAGCCACCAGTCCGTATGA | qRT‐PCR of TaPIE1 |

| TaPIE1‐QR | CACCCGGCAGAGGTATTCAA | |

| Chitinase 1‐QF | ATGCTCTGGGACCGATACTT | qRT‐PCR of Chitinase 1 |

| Chitinase 1‐QR | AGCCTCACTTTGTTCTCGTTTG | |

| defensin‐QF | ATGTCCGTGCCTTTTGCTA | qRT‐PCR of defensin |

| defensin‐QR | CCAAACTACCGAGTCCCCG |

qRT‐PCR, quantitative reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction; RACE, rapid amplification of cDNA ends; VIGS, virus‐induced gene silencing.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the programs of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant nos. 31271799, 31471494 and 31301314). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Asano, T. , Tanaka, N. , Yang, G.X. , Hayashi, N. and Komatsu, S. (2005) Genome‐wide identification of the rice calcium‐dependent protein kinase and its closely related kinase gene families: comprehensive analysis of the CDPKs gene family in rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 46, 356–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asano, T. , Hayashi, N. , Kobayashi, M. , Aoki, N. , Miyao, A. , Mitsuhara, I. , Ichikawa, H. , Komatsu, S. , Hirochika, H. , Kikuchi, S. and Ohsugi, R. (2012) A rice calcium‐dependent protein kinase OsCPK12 oppositely modulates salt‐stress tolerance and blast disease resistance. Plant J. 69, 26–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudsocq, M. and Sheen, J. (2013) CDPKs in immune and stress signaling. Trends Plant Sci. 18, 30–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai, S.B. , Ren, L.J. , Yan, W. , Wu, J.Z. , Chen, H.G. , Wu, X.Y. and Zhang, X.Y. (2006) Germplasm development and mapping of resistance to sharp eyespot (Rhizoctonia cerealis) in wheat (in Chinese with English abstract). Sci. Agric. Sin. 39, 928–934. [Google Scholar]

- Campo, S. , Baldrich, P. , Messeguer, J. , Lalanne, E. , Coca, M. and Segundo, B. S. (2014) Overexpression of a Calcium‐dependent protein kinase confers salt and drought tolerance in rice by preventing membrane lipid peroxidation. Plant Physiol. 165, 688–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacón, O. , González, M. , López, Y. , Portieles, R. , Pujol, M. , González, E. , Schoonbeek, H.J. , Métraux, J.P. and Borrás‐Hidalgo, O. (2010) Over‐expression of a protein kinase gene enhances the defense of tobacco against Rhizoctonia solani . Gene, 452, 54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. , Li, G.H. , Du, Z.Y. , Quan, W. , Zhang, H.Y. , Che, M.Z. , Wang, Z. and Zhang, Z.J. (2013) Mapping of QTL conferring resistance to sharp eyespot (Rhizoctonia cerealis) in bread wheat at the adult plant growth stage. Theor. Appl. Genet. 126, 2865–2878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L. , Zhang, Z. , Liang, H. , Liu, H. , Du, L. , Xu, H. and Xin, Z. (2008) Overexpression of TiERF1 enhances resistance to sharp eyespot in transgenic wheat. J. Exp. Bot. 59, 4195–4204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, S.H. , Willmann, M.R. , Chen, H.C. and Sheen, J. (2002) Calcium signaling through protein kinases. The Arabidopsis calcium‐dependent protein kinase gene family. Plant Physiol. 129, 469–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, A.H. and Quail, P.H. (1996) Ubiquitin promoter‐based vectors for high‐level expression of selectable and/or screenable marker genes in monocotyledonous plants. Transgenic Res. 5, 213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coca, M. and Segundo, B. (2010) AtCPK1 calcium‐dependent protein kinase mediates pathogen resistance in Arabidopsis . Plant J. 63, 526–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freymark, G. , Diehl, T. , Miklis, M. , Romeis, T. and Panstruga, R. (2007) Antagonistic control of powdery mildew host cell entry by barley calcium‐dependent protein kinases (CDPKs). Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 20, 1213–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng, S.F. , Li, A.L. , Tang, L.C. , Yin, L.J. , Wu, L. , Lei, C.L. , Guo, X.P. , Zhang, X. , Jiang, G.H. , Zhai, W.X. , Wei, Y.M. , Zheng, Y.L. , Lan, X.J. and Mao, L. (2013) TaCPK2‐A, a calcium‐dependent protein kinase gene that is required for wheat powdery mildew resistance enhances bacterial blight resistance in transgenic rice. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 3125–3130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper, J.E. , Breton, G. and Harmon, A. (2004) Decoding Ca2+ signals through plant protein kinases. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 55, 263–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzberg, S. , Brosio, P. , Gross, C. and Pogue, G.P. (2002) Barley stripe mosaic virus‐induced gene silencing in a monocot plant. Plant J. 30, 315–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, M. , Ohura, I. , Kawakita, K. , Yokota, N. , Fujiwara, M. , Shimamoto, K. , Doke, N. and Yoshioka, H. (2007) Calcium‐dependent protein kinases regulate the production of reactive oxygen species by potato NADPH oxidase. Plant Cell, 19, 1065–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, A.L. , Zhu, Y.F. , Tan, X.M. , Wang, X. , Wei, B. , Guo, H.Z. , Zhang, Z.L. , Chen, X.B. , Zhao, G.Y. , Kong, X.Y. , Jia, J.Z. and Mao, L. (2008) Evolution and functional study of the CDPK gene family in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Plant Mol. Biol. 66, 429–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B. , Lu, Y. , Xin, Z. and Zhang, Z. (2009) Identification and antifungal assay of a wheat beta‐1,3‐glucanase. Biotechnol. Lett. 31, 1005–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak, K.J. and Schmittgen, T.D. (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real‐time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods, 25, 402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig, A.A. , Saitoh, H. , Felix, G. , Freymark, G. , Miersch, O. , Wasternack, C. , Boller, T. , Jones, J.D. and Romeis, T. (2005) Ethylene‐mediated cross‐talk between calcium‐dependent protein kinase and MAPK signaling controls stress responses in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 102, 10736–10741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monaghan, J. , Matschi, S. , Shorinola, O. , Rovenich, H. , Matei, A. , Segonzac, C. , Malinovsky, F.G. , Rathjen, J.P. , MacLean, D. , Romeis, T. and Zipfel, C. (2014) The calcium‐dependent protein kinase CPK28 buffers plant immunity and regulates BIK1 turnover. Cell Host Microbe, 16, 605–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeis, T. , Ludwig, A.A. , Martin, R. and Jones, J.D. (2001) Calcium‐dependent protein kinases play an essential role in a plant defense response. EMBO J. 20, 5556–5560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saghai‐Maroof, M.A. , Soliman, K.M. , Jorgensen, R.A. and Allard, R.W. (1984) Ribosomal DNA spacer‐length polymorphisms in barley: Mendelian inheritance, chromosomal location, and population dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 81, 8014–8018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scofield, S.R. , Huang, L. , Brandt, A.S. and Gill, B.S. (2005) Development of a virus‐induced gene‐silencing system for hexaploid wheat and its use in functional analysis of the Lr21‐mediated leaf rust resistance pathway. Plant Physiol. 138, 2165–2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somssich, I.E. and Hahlbrock, K. (1998) Pathogen defense in plants: a paradigm of biological complexity. Trends Plant Sci. 3, 86–90. [Google Scholar]

- The International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium (IWGSC). (2014) A chromosome‐based draft sequence of the hexaploid bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) genome. Science, 345, 1251788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.L. , Li, H. and Ecker, J.R. (2002) Ethylene biosynthesis and signaling networks. Plant Cell, 14 (suppl), S131–S151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie, K. , Chen, J. , Wang, Q. and Yang, Y. (2014) Direct phosphorylation and activation of a mitogen‐activated protein kinase by a calcium‐dependent protein kinase in rice. Plant Cell, 26, 3077–3089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.J. , Pang, J.L. , Ye, X.G. , Du, L.P. , Li, L.C. , Xin, Z.Y. , Ma, Y.Z. , Chen, J.P. , Chen, J. , Chen, S.H. and Wu, H.Y. (2001) Study on the gene transferring of Nib8 into wheat for its resistance to the yellow mosaic virus by bombardment (in Chinese with English abstract). Acta. Agron. Sin. 27, 684–689. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, S.D. , Cho, Y.H. and Sheen, J. (2007) Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts: a versatile cell system for transient gene expression analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2, 1565–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. , Yao, W. , Dong, N. , Liang, H. , Liu, H. and Huang, R. (2007) A novel ERF transcription activator in wheat and its induction kinetics after pathogen and hormone treatments. J. Exp. Bot. 58, 2993–3003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H. , Li, S. , Deng, Z. , Wang, X. , Chen, T. , Zhang, J. , Chen, S. , Ling, H. , Zhang, A. , Wang, D. and Zhang, X. (2007) Molecular analysis of three new receptor‐like kinase genes from hexaploid wheat and evidence for their participation in the wheat hypersensitive response to stripe rust fungus infection. Plant J. 52, 420–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X. , Qi, L. , Liu, X. , Cai, S. , Xu, H. , Huang, R. , Li, J. , Wei, X. and Zhang, Z. (2014) The wheat ethylene response factor transcription factor pathogen‐induced ERF1 mediates host responses to both the necrotrophic pathogen Rhizoctonia cerealis and freezing stresses. Plant Physiol. 164, 1499–1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, R. , Hu, R. , Chai, G. , Xu, M. , Qi, G. , Kong, Y. and Zhou, G. (2013) Genome‐wide identification, classification, and expression analysis of CDPK and its closely related gene families in poplar (Populus trichocarpa). Mol. Biol. Rep. 40, 2645–2662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]