Summary

Vacuole proteases have important functions in different physiological processes in fungi. Taking this aspect into consideration, and as a continuation of our studies on the analysis of the proteolytic system of Ustilago maydis, a phytopathogenic member of the Basidiomycota, we have analysed the role of the pep4 gene encoding the vacuolar acid proteinase PrA in the pathogenesis and morphogenesis of the fungus. After confirmation of the location of the protease in the vacuole using fluorescent probes, we obtained deletion mutants of the gene in sexually compatible strains of U. maydis (FB1 and FB2), and analysed their phenotypes. It was observed that the yeast to mycelium dimorphic transition induced by a pH change in the medium, or the use of a fatty acid as sole carbon source, was severely reduced in Δpep4 mutants. In addition, the virulence of the mutants in maize seedlings was reduced, as revealed by the lower proportion of plants infected and the reduction in size of the tumours induced by the pathogen, when compared with wild‐type strains. All of these phenotypic alterations were reversed by complementation of the mutant strains with the wild‐type gene. These results provide evidence of the importance of the pep4 gene for the morphogenesis and virulence of U. maydis.

Keywords: fungal dimorphism, plant pathogenesis, proteinase A, Ustilago maydis, vacuole proteinases

Introduction

Proteolysis is an essential life process that plays an important role in protein degradation for cell nutrition, digestion of unwanted proteins, hormone maturation, enzyme activation, animal immune responses, fertilization and other cellular processes (Hecht et al., 2014; Jones, 2002). With regard to fungi, proteases are important in the formation and germination of spores, post‐translational regulation, pathogenesis and development (Monod et al., 1998; Suárez‐Rendueles et al., 1991; Vartivarian, 1992; White and Agabian, 1995).

The vacuole proteolytic system of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is one of the best characterized to date. It contains seven luminal proteases: proteinase A (PrA, encoded by the gene PEP4), proteinase B (PrB, a member of the subtilisin family of serine proteases, encoded by the gene PRB1), carboxypeptidases Y and S (CpY and CpS, encoded by the PRC1 and CPS1 genes, respectively), aminopeptidases I and Y (ApI and ApY, encoded by the LAP4 and APE3 genes, respectively), and the dipeptidyl aminopeptidase B (DPAP‐B, encoded by the DAP2 gene) (Jones, 2002; Li and Kane, 2009).

The pepsin‐like aspartic proteinase PrA (E.C. 3.4.23.25) from S. cerevisiae is essential for the vacuole proteolytic system under conditions of nutritional stress, sporulation and vegetative growth (Parr et al., 2007). Interestingly, the vacuole proteinases PrA, PrB and CpY are synthesized as inactive precursors and require specific proteolytic post‐translational processing to become activated (Jones, 1991; Mechler et al., 1982; Zubenko et al., 1983), and PrA has been implicated in the proteolytic activation of PrB, CpY and ApI (Klionsky et al., 1992; Woolford et al., 1986). The mature versions of these vacuole enzymes play an important role in cell survival during nitrogen starvation and sporulation (Jones, 1991).

The dimorphic Basidiomycotan fungus Ustilago maydis is a pathogen of maize (Zea mays), being the causal agent of corn smut. Of its two complex life cycles, the best known is the pathogenic cycle that involves its sexual development in the host. In this life cycle, unicellular and saprophytic haploid cells are transformed into a dikaryotic form (filamentous and pathogenic) through mating of sexually compatible partners. These dikaryotic hyphae invade the plant and produce the characteristic symptoms of the disease: the development of chlorosis, increased formation of anthocyanins and, characteristically, the development of tumours or galls in which diploid teliospores are accumulated at the end of the pathogenic phase. Teliospores germinate outside the host and produce phragmobasidia, which give rise to budding basidiospores, reinitiating the cycle (Banuett, 1992; Holliday, 1974). The second life cycle is saprophytic, and occurs in the absence of the host through the formation of complex basidiocarps. The latter, in turn, produce holobasidia in which meiosis occurs with the formation of budding basidiospores, which, on germination, may follow either life cycle (Cabrera‐Ponce et al., 2012).

Our previous studies have demonstrated that U. maydis contains acid proteases, both extracellular and intracellular, and that the addition of pepstatin A, a specific inhibitor of aspartic proteinases, inhibits the intracellular aspartic proteinase activity and the yeast to mycelium transition (Mercado‐Flores et al., 2003), which is normally induced at pH 3 (Ruiz‐Herrera et al., 1995). Through proteomic analysis, it was observed that the protein encoded by the pep4 gene (homologue of S. cerevisiae PEP4) was up‐regulated after the yeast to mycelium transition in the fungus induced by the over‐expression of the bE2/bW1 heterodimer, the leading transcription factor involved in the pathogenesis of U. maydis (Böhmer et al., 2007).

Considering the importance of the pep4 gene (um04926) of U. maydis, in the present study, we determined the subcellular localization and physiological roles of the encoded protein through deletion of its encoding gene and the phenotypic analysis of the corresponding mutants. The phenotypic characterization of Δpep4 mutants demonstrated that it plays an important role in the morphogenesis and pathogenesis of the fungus.

Results

Identification of the U. maydis pep4 homologue gene

The putative U. maydis pep4 gene, a homologue of the PEP4 gene of S. cerevisiae (GenBank accession number M13358.1), was identified by a blastx search in the Munich Information Centre for Protein Sequences (MIPS) U. maydis database (MUMDB) with access number (um04926). A U. maydis protein sequence was retrieved, which had an e‐value of 9.1e−112 and 57% identity to S. cerevisiae PrA. This U. maydis putative pep4 gene (1257 bp without any intron detected) is located in chromosome 15, contig 1.180, and encodes a protein of 418 amino acids. The protein sequence contains the characteristic conserved motif of aspartyl proteases with two aspartic acid residues in the active site (VILD125TGSSNLWV and AAID307TGTSLIAM). In addition, the amino acid sequence of PrA in U. maydis contained a characteristic N‐glycosylation motif (Asn160), cysteine residues involved in disulfide bond formation (Cys138–Cys143 and Cys341–Cys374) and a 22‐amino‐acid sequence of a putative N‐terminal vacuole targeting signal sequence (data not shown).

Subcellular localization of U. maydis PrA

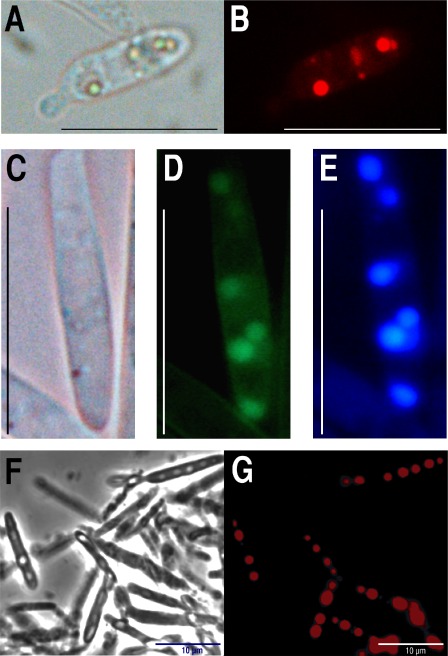

The existence of a vacuole signal peptide in U. maydis PrA suggests that its subcellular location is in the vacuole, as occurs with its S. cerevisiae homologue. To obtain further evidence for this possibility, we fused the monomeric form of red fluorescent protein (mRFP) or the enhanced version of green fluorescent protein (eGFP) to the C‐terminus of PrA as described in Experimental details. The fusion constructs were expressed in haploid cells under the control of the constitutive pep4 promoter. Fluorescence microscopy of strains CS7 (PrA‐eGFP) and CS8 (PrA‐mRFP) grown in complete medium (MC) for 24 h confirmed the vacuole location of PrA [compare Fig. 1A, C and F (bright field) with B, E and G (fluorescence)]. Localization of the proteinase in the vacuole was confirmed by staining with the vacuole‐specific dye 7‐amino‐4‐choromethylcoumarin (CMAC) (compare Fig. 1D and E).

Figure 1.

Ustilago maydis proteinase A (PrA) is targeted to the vacuole. The C‐terminal PrA of U. maydis was fused to enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) or the monomeric form of red fluorescent protein (mRFP) and expressed in haploid U. maydis cells. (A, B) One cell of the PrA‐mRFP‐expressing U. maydis CS8 transformant grown on complete medium (MC), incubated at 28 °C for 24 h and observed by bright field or fluorescence microscopy, respectively. (C–E) One cell of the PrA‐eGFP‐expressing U. maydis CS7 transformant grown on MC, incubated at 28 °C for 24 h and observed by bright field or fluorescence microscopy, or stained with the fluorescent dye 7‐amino‐4‐choromethylcoumarin (CMAC), respectively. (F, G) Large vacuoles observed in CS8 PrA‐RFP cells grown in minimal medium (MM) without nitrogen source for 72 h and observed by bright field or fluorescence microscopy, respectively. Stained vacuoles are observed only in cells at the correct focal plane. Scale bars: 10 μm.

Disruption of the gene encoding U. maydis PrA

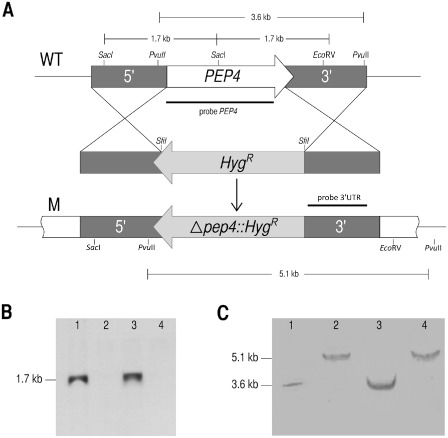

Deletion mutants of the pep4 gene were generated to explore its role in U. maydis. Gene replacement in both sexually compatible strains, FB1 (a1b1) and FB2 (a2b2), was obtained by double homologous recombination using, as selection marker, the hygromycin resistance cassette (HygR) from the PMF1‐h vector (Fig. 2A). pep4 disruption was confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with primers 4 and 11 (Table 1), which gave fragments of 4.3 or 5.8 kb as products, corresponding to the wild‐type and mutant strains, respectively (data not shown). The mutation was confirmed by Southern blot analysis of the genomic DNA digested with SacI‐EcoRV endonucleases, using the whole pep4 gene as the probe (1.2 kb). The absence of hybridizing fragments in the OR1 (a1b1 Δpep4::HygR) and OR2 (a2b2 Δpep4::HygR) null mutant strains indicated the deletion of the gene (Fig. 2B, lanes 2 and 4). In a further experiment, the 3′‐untranslated region corresponding to the terminator of the pep4 gene (848 bp) was used as the probe, and the genomic DNA was digested with PvuI. In this case, a hybridizing 3.6‐kb fragment corresponded to the wild‐type gene (Fig. 2C, lanes 1 and 3), whereas a 5.1‐kb fragment indicated the presence of the mutant allele at the right locus (Fig. 2C, lanes 2 and 4).

Figure 2.

Mutation of pep4 gene. (A) Strategy for replacement of the pep4 open reading frame (ORF) with the hygromycin resistance cassette. (B) Southern blot hybridization of wild‐type and pep4 mutant strains of Ustilago maydis whose genomic DNA was digested with SacI‐EcoRV and probed with an ORF pep4 fragment. The absence of hybridizing fragments in the OR1 and OR2 mutant strains indicated the deletion of the gene (lanes 2 and 4), whereas the fragment was present in the FB1 and FB2 wild‐type strains (lanes 1 and 3). (C) Southern blot hybridization of DNA digested with PvuII and probed with a 3′ untranslated region (UTR) 848‐bp fragment of the region corresponding to the terminator of the pep4 gene. A 3.6‐kb fragment was observed in the wild‐type strain (lanes 1 and 3), whereas a 5.1‐kb fragment carrying the pep4 mutant copy was identified in the mutant strain (lanes 2 and 4).

Table 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Name | Sequence* |

|---|---|

| 1. pMF2Fwd | 5′‐GAGGCTCAACGTAGATCACAGG‐3′ |

| 2. pMF2Rev | 5′‐CAGGCTCTCGCTGAGTTCC‐3′ |

| 3. pepintLFwd | 5′‐TGAGGCCTAGATGGCCCCGCAAACATGTTGAGGAGCTC‐3′ |

| 4. pepintLRev | 5′‐TTCGGCCATCTAGGCCGGGAGAGGTTGAGCTTCCATCC‐3′ |

| 5. pepintRFwd | 5′‐TGAGGCCTGAGTGGCCGTGAAGAGGCGACAAGGCTTTG‐3′ |

| 6. pepintRrev | 5′‐TTCCGGCCACTCAGGCCGTTCAAACACGCCTTGGCCTC‐3′ |

| 7. DerUm25 | 5′‐TTGTTCGGAGCCACCCAGTAC‐3′ |

| 8. pMF1Fwd | 5′‐GTTCGTGCACACAGCCCAG‐3′ |

| 9. pMF1Rev | 5′‐ CGCGCACATTTCCCCGAAAAG‐3′ |

| 10. pep4umFwd | 5′‐CGCGCGAATTCATGAAGCTCAACCTCTCCCTCAC‐3′ |

| 11. pep4umRev | 5′‐CGCGCGAATTCCTTGGCAGTCGCGAGAC‐3′ |

| 12. pPep4tFwd | 5′‐TCGAATTCCCGCAAACATGTTGAGGAGCTC‐3′ |

| 13. pepfusFwdL | 5′‐CCTCAACGCCCAGTACTTTTGC‐3′ |

| 14. pepfusRevL | 5′‐ATTTCGGCCGCGTTGGCCTCCTTGGCAGTCGCGAGAC‐3′ |

| 15. pepfusFwdR | 5′‐TGAGGCCTGAGTGGCCGCAACGTGCTACGAGCAACG‐3′ |

| 16. pepfusRevR | 5′‐CAGCTCTGTTGATGGTGAGCG‐3′ |

*Restriction sites are shown in italics.

Determination of acid protease activity

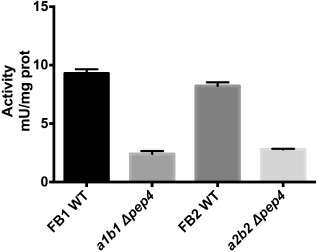

As expected, there was a significant decrease in the protease activity of OR1 and OR2 null mutants compared with the activity of the wild‐type strain (Fig. 3). The residual enzymatic activity in the mutants is probably caused by the presence in the fungus of acid proteases other than PrA.

Figure 3.

Proteolytic activity of wild‐type (WT) and mutant strains (Δpep4::HygR). Specific proteinase A activity in wild‐type and mutant strains of cells grown in complete medium (MC) for 24 h. Error bars indicate standard deviation (n = 9).

pep4 mutation does not affect mating

The mating capacity of mutant strains, evaluated by the Fuzz reaction, was not affected by any combination of mutant–wild‐type or mutant–mutant mating pairs. Similar results were obtained when the formation of conjugation tubes in mutant strains was analysed (data not shown).

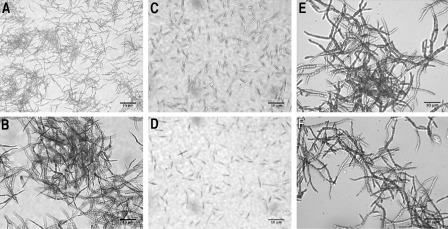

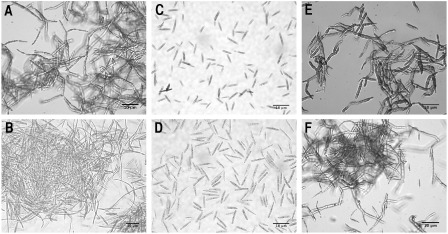

Δpep4 mutant cells are affected in the yeast to mycelium dimorphic transition

The phenotypic characterization of mutants involved the analysis of cell morphology in synthetic minimal medium (MM) with an initial pH of 7 or 3. As expected, FB1 and FB2 wild‐type U. maydis cells grew as mycelium at acid pH at 16 h post‐induction (Fig. 4A,B). However, no filamentous growth of either Δpep4 mutant strains was evident at acid pH after 16 h of incubation (Fig. 4C,D). Complementation of the mutation (see Experimental procedures) reversed the mutant phenotype, and mycelium formation was observed in the complemented strains CS49 (a1b1 Δpep4/PEP4:CbxR) and CS1 (a2b2 Δpep4/PEP4:CbxR) (Fig. 4E,F, respectively).

Figure 4.

Induction of yeast to mycelium dimorphism by acid pH. Strains were grown in minimal medium (MM) at pH 3 for 16 h; the cells were stained with lactophenol blue and observed by microscopy. (A, B) Wild‐type strains FB1 and FB2, respectively. (C, D) OR1 (a1b1 Δpep4::HygR) and OR2 (a2b2 Δpep4::HygR) mutant strains, respectively. (E, F) Complemented strains CS49 and CS1 respectively. Scale bars, 10 μm.

The use of 1% palmitic acid as the sole carbon source in MM at pH 7 for the growth of the FB1 and FB2 wild‐type strains induced mycelium development after 5 days of incubation, as described by Klose et al. (2004) (Fig. 5A,B, respectively). In contrast, OR1 and OR2 Δpep4 mutants remained in the yeast form during the entire incubation period (Fig. 5C,D, respectively). As expected, mycelium formation in the complemented strains CS49 and CS1 (see Experimental procedures) was observed after 5 days of incubation (Fig. 5E,F, respectively).

Figure 5.

Induction of yeast to mycelium dimorphism by palmitic acid. Strains were grown in minimal medium (MM) at pH 7 with 1% palmitic acid as carbon source for 5 days; the cells were stained with lactophenol blue and observed by microscopy. (A, B) Ustilago maydis wild‐type strains FB1 and FB2, respectively. (C, D) OR1 and OR2 mutant strains, respectively. (E, F) Complemented strains CS49 and CS1, respectively. Scale bars, 10 μm.

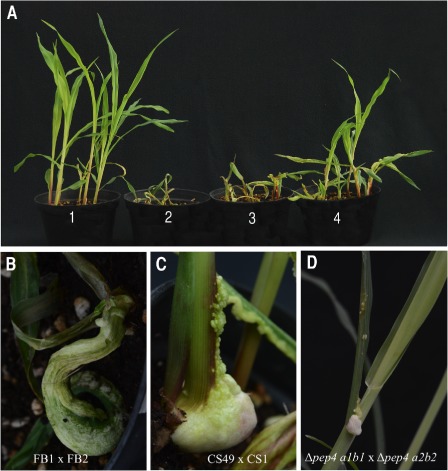

Δpep4 mutants show reduced virulence to maize

Virulence was assayed in maize seedlings infected with compatible mixtures of either wild‐type, Δpep4 mutant or complemented strains. A total of 77% of the inoculated seedlings infected with a combination of the wild‐type strains (FB1 and FB2) developed large tumours and showed evident chlorosis symptoms and anthocyanin pigment accumulation at 14 days post‐inoculation (dpi). However, only 42% of the seedlings infected with the combination of OR1 and OR2 mutant strains developed small tumours (Table 2).

Table 2.

Virulence assays

| Strains | Inoculated plants (n) | No symptomsb (%) | Chlorosis and/or anthocyanins (%) | Plants with tumoursa (%) | Dead (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FB1/FB2 | 137 | 5 (3.6) | 20 (14.0) | 106 (77.3) | 19 (13.8) |

| OR1/OR2 | 146 | 34 (23.0) | 54 (36.9) | 62 (42.4) | 2 (1.3) |

| CS49/CS1 | 150 | 0 | 5 (3.3) | 92 (61.3) | 50 (33.3) |

Statistical comparison of tumour formation by Kruskal–Wallis analysis demonstrated significant variance between the wild‐type, Δpep4 mutant and the complemented strains (P = 0.0023).

Symptoms were observed at 14 days post‐inoculation.

Statistical comparison of tumour formation by Kruskal–Wallis analysis demonstrated significant variance between the wild‐type, Δpep4 mutant and the complemented strains (P = 0.0023).

An interesting observation was that teliospores from plants inoculated with the Δpep4 mutants were not fully pigmented (not shown) and also showed difficulties with germination in contrast with wild‐type teliospores. Accordingly, only 24% of Δpep4 mutants germinated compared with 92% of wild‐type strains.

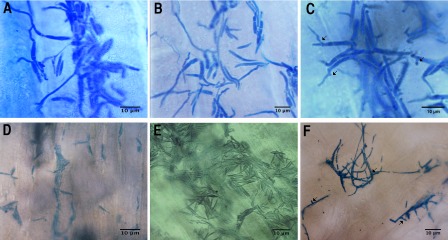

Microscopic observations of maize seedlings infected with wild‐type strains revealed that the infection process by the mutants was slower compared with infection by the wild‐type strains. Thus, hyphae from wild‐type strains appeared branched in the epidermal cells at 2 dpi (data not shown); at 3 dpi, proliferation of mycelium appeared in the underlying tissue and, at 6 and 8 dpi, very long masses of hyphae were observed (Fig. 6A–C). In contrast, in seedlings infected with Δpep4 strains, no hyphae were observed, even at 3 or 6 dpi (Fig. 6D,E), and hyphae appeared branched (arrows) in the tissue only at 8 dpi (Fig. 6F). These results indicate that the deletion of pep4 severely impaired hyphal proliferation and development in the infected plant tissues.

Figure 6.

Development of Ustilago maydis in inoculated maize seedlings. Sexually compatible mixtures of the different strains were inoculated in maize seedlings; sections were obtained at different days post‐inoculation (dpi), stained with lactophenol–cotton blue and observed by microscopy. (A–C) Sections from the inoculation zone of maize seedlings infected with mixtures of wild‐type strains FB1 and FB2 obtained after 3, 6 and 8 dpi, respectively. (D–F) Sections from the inoculation zone of maize seedlings infected with mixtures of OR1 and OR2 mutant strains obtained after 3, 6 and 8 dpi respectively. Some branches are marked by arrows. Scale bars, 10 μm.

As occurred with dimorphism, the phenotype of reduced virulence was reversed by introduction of the wild‐type gene in the mutants, and the complemented strains CS49 and CS1 proved to be as virulent as the wild‐type strains (Table 2, Fig. 7A3,C). In general, we observed that tumours were smaller in the seedlings infected with the mutant strains (Fig. 7A4,D), than in those infected with the wild‐type strains (Fig. 7A2,B).

Figure 7.

Symptoms developed in maize seedlings inoculated with Ustilago maydis. Maize seedlings were inoculated as described in Fig. 6 and symptoms were observed at 14 days post‐inoculation (dpi). (A) Infection symptoms of maize seedlings: 1, plants injected with sterile water; 2, plants infected with wild‐type FB1 (a1b1) and FB2 (a2b2) strains; 3, plants infected with CS49 and CS1 complemented strains; 4, plants infected with OR1 and OR2 mutant strains. (B, C) Large tumour formation in seedlings inoculated with mixtures of FB1 and FB2 wild‐type or CS49 and CS1 complemented strains, respectively. (D) Small tumour formation in seedlings inoculated with OR1 and OR2 mutant strains.

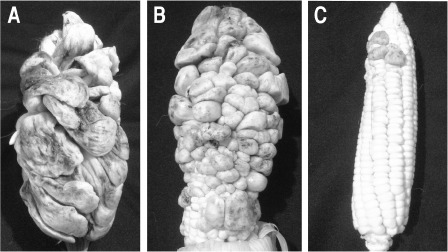

In further experiments, we inoculated the maturing ears of maize plants (‘jilote’ stage) with sexually compatible mixtures of wild‐type, complemented or mutant strains to better evaluate teliospore production and development. Two weeks after inoculation with the FB1 and FB2 wild‐type strains, numerous galls had formed on infected ears (Fig. 8A). As expected, ears inoculated with CS49 and CS1 complemented strains showed numerous galls with dark teliospores (Fig. 8B). In contrast, at the same time, ears inoculated with the OR1 and OR2 compatible mutant strains only showed a few very immature galls (Fig. 8C).

Figure 8.

Virulence assay in fully grown maize plants. Maturing maize ears were inoculated with a suspension of mixed sporidia from sexually compatible Ustilago maydis strains. The symptoms were evaluated after 2 weeks. (A) Tumour development in maize ears inoculated with a mixture of FB1 and FB2 wild‐type strains. (B) Tumour development in maize ears inoculated with a mixture of CS49 and CS1 complemented strains. (C) Reduced numbers of tumours in ears co‐inoculated with a mixture of sexually compatible Δpep4 mutants (OR1 and OR2).

Discussion

In contrast with the vacuole proteases of S. cerevisiae, which have been thoroughly studied and characterized, the knowledge of the protease system of U. maydis is very limited. Data from one of our laboratories have described that crude extracts of U. maydis display proteolytic activity corresponding to the putative homologues of S. cerevisiae PrA, PrB, aminopeptidase pumAPE and dipeptidyl aminopeptidase pumDAP. It has also been reported that pepstatin A, a specific inhibitor of aspartyl proteases, inhibits intracellular aspartic protease activity and also the dimorphic yeast to mycelium transition induced by acidic conditions in the culture medium (Mercado‐Flores et al., 2003). This latter result suggests a possible role of acid protease activity in the dimorphic transition of U. maydis. These experiments were followed by the purification and biochemical characterization of an intracellular aspartyl protease with Mr = 36 kDa and pI = 5.5 (Mercado‐Flores et al., 2005). According to the data from the U. maydis genome (http://pedant.helmholtz‐muenchen.de/pedant3htmlview/pedant3view?Db=p3_t237631_Ust_maydi_v2&Method=ReportGene&GeneticelemID=5261&Elementtype=orf), the aspartyl protease encoded by the yeast homologue pep4 gene has a predicted Mr of 44.7 kDa and pI of 4.84. Although these data do not coincide with those reported by Mercado‐Flores et al. (2005), it must be recalled that the molecular weight decreases in the mature protein, and we hypothesize that the previously purified protease is probably the same one as encoded by pep4.

The existence of a vacuole signalling peptide in the U. maydis PrA studied here suggests that it has a vacuolar location, and this supposition was confirmed by labelling with mRFP or eGFP and analysing its distribution by fluorescence microscopy. Moreover, our bioinformatics analysis showed that U. maydis PrA has a high identity percentage with the vacuole PrAs from Candida albicans (58%), S. cerevisiae (57%) and Neurospora crassa (53%) (Lott et al., 1989; Vázquez‐Laslop et al., 1996; Woolford et al., 1986).

In S. cerevisiae, PrA is important for the maturation of other vacuole hydrolases, as well as for bulk degradation during nutritional stress and morphological transitions (Jones, 1991). In agreement with this latter role, in the present work, we found that the pep4 gene is involved in U. maydis morphogenesis. Accordingly, its mutation affected the yeast to mycelium dimorphic transition of both FB1 and FB2 haploid strains induced in vitro by acidic pH, or by the use of palmitic acid as a carbon source. This also agrees with the observation that the protein encoded by the pep4 gene of U. maydis was found to be up‐regulated during filament induction by both bE1/bW2 and Rac1 (Böhmer et al., 2007). Interestingly, another aspartyl protease (um02178) was up‐regulated during the dimorphic transition from yeast to mycelium, but its function is still unclear (Martínez‐Soto and Ruiz‐Herrera, 2013).

This relationship between PrA homologues and dimorphism is not exclusive to U. maydis. Accordingly, it has been shown that the human pathogen Paracoccidioides brasiliensis expresses its PEP homologue gene during morphogenesis from mycelium to yeast (Parente et al., 2008). In addition, it should be recalled that the corresponding homologue from C. albicans is required for the morphological transition of the fungus (Niimi et al., 1997). More recently, a set of differentially expressed genes was found to be related to the hyphal growth of Malassezia furfur, a distantly related Basidiomycota, among them four with a sequence homologous to U. maydis pep4 (Simon et al., 2010).

An important result obtained in the present study was the observation that deletion of the U. maydis pep4 gene brought about an important reduction in the virulence of U. maydis on maize, including an incomplete maturation of teliospores, which showed problems in germination. Again, this observation does not seem to be an isolated phenomenon. Previously, it has been demonstrated that the C. albicans homologue gene is a virulence factor (Bauerová et al., 2012, 2014; Niimi et al., 1997), and we may also cite data from Reichard et al. (2000), who reported the isolation and characterization of the PEP2 gene, which encodes a novel aspartic proteinase from Aspergillus fumigatus with 64% identity to the S. cerevisiae vacuole PrA, with possible function during invasive aspergillosis.

In conclusion, the results presented here provide evidence that the vacuole PrA is involved in the dimorphic transition of U. maydis and its pathogenic behaviour. These data, when added to the reported phenotypes of PrA mutants from other fungi, indicate that these proteinases are somehow involved in cell differentiation and virulence. Taking into consideration that U. maydis is an ideal model for studies dealing with these problems, the present results also open up the possibility to analyse the mechanisms involved.

Experimental Procedures

Strains, culture media and growth conditions

The U. maydis wild‐type and mutant strains used in this study (Table 3) were maintained at −70 °C in 50% (v/v) glycerol, recovered in liquid MC (Holliday, 1974) at 28 °C, shaken in a rotary shaker at 150 rpm and used as inoculum for subsequent experiments. Ustilago maydis transformants were selected on MC plates supplemented with 1 m sorbitol and 400 μg/mL of hygromycin B or 16 μm of carboxin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA).

Table 3.

Strains of Ustilago maydis used in this study

Yeast or mycelium cells were obtained by growth in MM (Holliday, 1974) at pH 7 or pH 3, respectively, as described previously (Ruiz‐Herrera et al., 1995). In addition, mycelium growth was induced with fatty acids (MM containing 1% palmitic acid as a carbon source), as described by Klose et al. (2004).

Escherichia coli DH10b (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used for cloning purposes; it was grown at 37 °C in Luria–Bertani (LB) medium (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 0.5% sodium chloride) containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin for plasmid selection.

Bioinformatic analysis

Sequence similarities were estimated with clustalw (Kyoto University Bioinformatics Centre, Kyoto, Japan) by comparing the amino acid sequences of PrA from S. cerevisiae, C. albicans and N. crassa. The amino acid sequence from the protein encoded by the pep4 gene was retrieved with the wublast analysis tool from the U. maydis database of the Munich Information Centre for Protein Sequences (MIPS), Munich, Germany (http://www.helmholtz‐muenchen.de/en/ibis/institute/groups/fungal‐microbial‐genomics/resources/mumdb/index.html). The prediction of domains, glycosylation sites and subcellular location was performed using the ScanProsite database, NetNGlyc 1.0 Server (http://www.expasy.org) and SignalP (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/) (Bendtsen et al., 2004).

DNA procedures

Genomic DNA from U. maydis was obtained as described by Hoffman and Winston (1987). Transformation of U. maydis protoplasts and Southern blot hybridizations were carried out by standard methods (Wang et al., 1988 and Sambrook and Russell, 2001, respectively). DNA probes were labelled by PCR using alkali‐labile digoxigenin‐11‐dUTP (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA). The DNA employed in sequencing, ligation and labelling reactions was purified using the QIAquick Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA).

Southern blot analyses

Southern blot analyses were performed with genomic DNA from null mutants OR1 (a1b1 Δpep4::HygR) and OR2 (a2b2 Δpep4::HygR) digested with SacI‐EcoRV for the pep4 probe and with PvuII endonuclease for the pep4‐3′UTR probe. These DNA forms were subsequently separated by electrophoresis in agarose gel and transferred to a positively charged nylon membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ, USA), as described by Sambrook and Russell (2001).

Probes for Southern blotting were generated by PCR. Genomic DNA from U. maydis FB1 (a1b1) was used as template and was labelled with digoxigenin‐dUTP (alkali‐labile digoxigenin‐11‐dUTP) using the DIG DNA labelling and detection kit, following the manufacturer's instructions (Roche). To generate the probe for the pep4 gene (um04926), a 1.2‐kb fragment was amplified using the combination of primers 10 and 11 (Table 1); the probe for the pep4‐3′UTR gene, an 848‐bp fragment, was generated using the combination of primers 5 and 6.

Plasmids

The oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Table 1. Plasmids pCR2.1 TOPO (Invitrogen) and blunt pJET1.2 (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) were used for cloning and sequencing of the fragments generated by PCR. Plasmid pMF1‐h was used to generate the mutants, and pMF5‐1h and pMF5‐2h were used for the subcellular localization of PrA (provided by Michael Feldbrügge, Institute for Microbiology, Cluster of Excellence on Plant Sciences, Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany).

Determination of the subcellular location of PrA in U. maydis

C‐terminal PrA‐mRFP and PrA‐eGFP fusion constructs were placed under the control of the native pep4 promoter. A 969‐bp fragment from the coding sequence of pep4 was generated by PCR on U. maydis FB1 DNA with primers 13 and 14 (Table 1; the latter primer introduces an SfiI site at the 5′ end and removes the stop codon from the pep4 gene). The fragment was introduced in the plasmid TOPO2.1. Separately, a fragment of 956 bp comprising the 3′ flank of pep4 was amplified using a combination of primers 15 and 16 (Table 1), and cloned into blunt pJET 1.2. At the next step, an SfiI fragment of the reporter gene encoding eGFP or mRFP, and the hygromycin resistance cassette from pMF5‐1h or pMF5‐2h, respectively (Brachmann et al., 2004), was introduced into the respective site of the pJET derivative, resulting in pOR17 or pOR61 plasmid. As a result, the eGFP or mRFP protein was placed under the control of the pep4 promoter. These plasmids were sequenced and used for the transformation of FB1 (a1b1) U. maydis strain, obtaining CS7 (a1b1 PrA‐eGFP) and CS8 (a1b1 PrA‐mRFP) strains, respectively.

For vacuole visualization, the CS7 strain was grown in MC for 24 h, recovered by centrifugation and the vacuole lumen was stained with 100 μM CMAC (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) for 30 min. Cells were washed once, suspended in phosphate‐buffered saline and observed by fluorescence microscopy at 100× magnification. In addition, cells of the CS8 strain were grown in MM without a nitrogen source for 72 h, and the vacuoles were observed by fluorescence microscopy.

Generation of Δpep4 mutants

The pep4 deletion mutants OR1 (a1b1 Δpep4::HygR) and OR2 (a2b2 Δpep4::HygR) were generated according to Brachmann et al. (2004). The 865‐bp upstream flank PCR fragment replacement construct was amplified with the oligonucleotide primers 3 and 4 (Table 1) using the U. maydis FB1 genomic DNA, and cloned into pCR2.1 TOPO (Invitrogen). Similarly, an 848‐bp downstream flank was amplified by PCR using primers 5 and 6, and cloned into blunt pJET1.2 (Thermo Scientific). These oligonucleotides recognize SfiI sites (Table 1) for further ligation. The plasmids were digested with SfiI to obtain left and right flanks for the pep4 replacement constructs and ligated to the 2.7‐kb SfiI hygromycin resistance cassette from the pMF1‐h plasmid. The resulting ligation product was cloned into blunt pJET1.2 to generate the pORpepint plasmid. This plasmid was sequenced and linearized with PmeI and then used in transformation to generate the pep4 deletion mutants OR1 (a1b1 Δpep4::HygR) and OR2 (a2b2 Δpep4::HygR). Homologous integration was confirmed by PCR and Southern blot analysis.

Ustilago maydis pep4 complementation

A fragment of 2.9 kb, containing the whole pep4 gene from U. maydis, including the 865‐bp and 848‐bp segments of its promoter and terminator regions, respectively, was amplified by PCR using FB1 and FB2 genomic DNA as template, and the combination of primers 12 and 6 (Table 1). This fragment was cloned into blunt pJET1.2 to generate the pCS7 plasmid (pJET‐pep4). The DNA fragment containing the pep4 gene and its promoter and terminator regions was sequenced and subcloned as an EcoRI‐XbaI fragment into plasmid pCBX122 (Keon et al., 1991), yielding plasmid pCS31 (pep4‐CbxR). This plasmid was used for the transformation of U. maydis strains OR1 (a1b1 Δpep4::HygR) and OR2 (a2b2 Δpep4::HygR). Carboxin‐resistant transformants CS49 (a1b1 Δpep4/pep4:CbxR) and CS1 (a2b2 Δpep4/pep4:CbxR) were recovered and used for phenotypic characterization.

Mating

Mating was analysed by the Fuzz reaction and conjugation tube formation (Banuett, 1992, 1995).

Plant inoculation and determination of symptoms

Essentially, we followed the method described by Martínez‐Espinoza et al. (1997). Maize seeds (cv. Cacahuazintle) were soaked on sterile filter papers and, on germination, were transferred to pots containing a mixture of soil, perlite and vermiculite. After 1 week, seedlings (about 40 per experiment) were inoculated with syringe and needle in the leaf whorl with 100 μL (107 cells/mL) of a mixture of sexually compatible strains of U. maydis. Seedlings were monitored for symptoms during 15 dpi. We obtained sections at 3, 6 and 8 dpi from the inoculation zone of infected maize seedlings; sections of leaf tissue were made with a razor blade, stained directly with lactophenol blue, observed under light microscopy and photographed.

Three independent biological replicates were analysed using appropriate statistical programs (PRISM package; Graph Pad Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Statistical comparison of all groups by Kruskal–Wallis analysis of variance demonstrated significant variance between the wild‐type, complemented and mutant strains (P ≤ 0.05).

In addition, lots of seven maturing maize ears (in two separate experiments) were inoculated by injection with syringe and needle with 106 cells/mL of a suspension of mixed sporidia from sexually compatible U. maydis strains. The symptoms were evaluated after 2 weeks.

Teliospore isolation and germination

The procedure described by Chávez‐Ontiveros et al. (2000) was followed. Mature tumours were excised from plants infected with mixtures of compatible wild‐type sporidia, as described above. Tumours were washed successively with 70% sodium hypochlorite and sterile water, and were crushed to liberate teliospores. These were treated with 0.5% CuSO4 for 2 h, filtered through cheesecloth and recovered by centrifugation at 5000 g. Teliospores were washed and 250 were spread onto CM plates and incubated at 28 °C until germination. After 4 days, the percentage of germination was evaluated between wild‐type and mutant strains.

Acid protease activity determination

The enzymatic activity of PrA was determined as described by Jones (2002) using acid‐denatured haemoglobin (Sigma) as substrate. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and washed once with sterile distilled water. The cells were broken with 0.45‐mm glass beads (equal volumes of cells and glass beads) in a homogenizer and suspended in 0.1 m Tris‐HCl buffer (pH 7.6). The suspension was centrifuged for 10 min at 13 000 g, and the supernatant was used for activity determination.

The enzymatic fraction (20 μL), previously taken to pH 5.0 with 3 M acetic acid, was mixed with 200 μL of haemoglobin (2.5 mg/100 mL) in glycine buffer at pH 3.2. The mixture was incubated for 90 min at 37 °C and the reaction was stopped by the addition of 200 μL of 10% trichloroacetic acid. The sample was centrifuged and the supernatant was removed and analysed using Folin's reagent according to Lowry et al. (1951). One unit of activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that released 1 μg of tyrosine‐containing peptides per minute at 37 °C. The specific activity was related to 1 mg of protein extract.

Microscopy

Samples were observed under a Leica DMRE (Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) light microscope after staining with cotton blue–lactophenol (Sigma), which stained fungal cells only. Vacuoles were observed with a fluorescence microscope (Leica DMRE). Microphotographs were obtained with a Spot digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments, New York, USA).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Michael Feldbrügge (Institute for Microbiology, Cluster of Excellence on Plant Sciences, Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany) for provision of the PMF1‐h, pMF5‐1h and pMF5‐2h plasmids, Melissa Vázquez‐Carrada (Departamento de Microbiología, Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biológicas‐Instituto Politécnico Nacional, D.F., México) for her help with Southern blot analysis and Antonio Cisneros (Centro de Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados del IPN, Irapuato, México) for maize photographs. CVS‐G is a doctorate student recipient of fellowships from Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACyT) and Beca de Estímulo Institucional de Formación de Investigadores (BEIFI‐IPN). LV‐T and CH‐R received support from Comisión de Operación y Fomento de Actividades Académicas del Instituto Politécnico Nacional (COFAA‐IPN) and Estimulo al Desempeño de los Investigadores (EDI‐IPN), as well as grants from Instituto de Ciencia y Tecnología del DF (ICyT‐DF) (PICSO10‐95, 254/10) and CONACyT (208247, SIP‐IPN, 20131171, 20141333 and 20150981). JR‐H is Emeritus National Investigator, Mexico.

References

- Banuett, F. (1992) Ustilago maydis, the delightful blight. Trends Genet. 8, 174–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banuett, F. (1995) Genetics of Ustilago maydis, a fungal pathogen that induces tumours in maize. Annu. Rev. Genet. 29, 179–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banuett, F. and Herskowitz, I. (1989) Different a alleles are necessary for maintenance of filamentous growth but not for meiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 86, 5878–5882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauerová, V. , Pichová, I. and Hrušková‐Heidingsfeldová, O. (2012) Nitrogen source and growth stage of Candida albicans influence expression level of vacuolar aspartic protease Apr1p and carboxypeptidase Cpy1p. Can. J. Microbiol. 58, 678–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauerová, V. , Hájek, M. , Pichová, I. and Hrušková‐Heidingsfeldová, O. (2014) Intracellular aspartic proteinase Apr1p of Candida albicans is required for morphological transition under nitrogen‐limited conditions but not for macrophage killing. Folia Microbiol. 59, 485–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendtsen, J.D. , Nielsen, H. , von Heijne, G. and Brunak, S. (2004) Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J. Mol. Biol. 340, 783–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böhmer, M. , Colby, T. , Böhmer, C. , Bräutigam, A. , Schmidt, J. and Bölker, M. (2007) Proteomic analysis of dimorphic transition in the phytopathogenic fungus Ustilago maydis . Proteomics, 7, 675–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachmann, A. , König, J. , Julius, C. and Feldbrügge, M. (2004) A reverse genetic approach for generating gene replacement mutants in Ustilago maydis . Mol. Gen. Genomics, 272, 216–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera‐Ponce, J.L. , León‐Ramírez, C.G. , Verver‐Vargas, A. , Palma‐Tirado, L. and Ruiz‐Herrera, J. (2012) Metamorphosis of the Basidiomycota Ustilago maydis: transformation of yeast‐like cells into basidiocarps. Fungal Genet. Biol. 49, 765–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chávez‐Ontiveros, J. , Martínez‐Espinoza, A.D. and Ruiz‐Herrera, J. (2000) Double chitin synthetase mutants from the corn smut fungus Ustilago maydis . New Phytol. 146, 335–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht, K.A. , O'Donnell, A.F. and Brodsky, J.L. (2014) The proteolytic landscape of the yeast vacuole. Cell Logist. 1, e28023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, C.S. and Winston, F. (1987) A ten‐minute DNA preparation from yeast efficiently releases autonomous plasmids for transformation of Escherichia coli . Gene, 57, 267–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holliday, R. (1974) Ustilago maydis In: Handbook of Genetics, Vol. 1 (King R.C., ed.), pp. 575–595. New York: Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, E.W. (1991) Three proteolytic systems in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae . J. Biol. Chem. 266, 7963–7966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, E.W. (2002) Vacuolar proteases and proteolytic artifacts in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Methods Enzymol. 351, 127–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keon, J.P. , White, G.A. and Hargreaves, J.A. (1991) Isolation, characterization and sequence of a gene conferring resistance to the systemic fungicide carboxin from the maize smut pathogen, Ustilago maydis . Curr. Genet. 19, 475–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky, D.J. , Cueva, R. and Yaver, D.S. (1992) Aminopeptidase I of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is localized to the vacuole independent of the secretory pathway. J. Cell Biol. 119, 287–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klose, J. , Moniz de Sá, M. and Kronstad, J.W. (2004) Lipid‐induced filamentous growth in Ustilago maydis . Mol. Microbiol. 52, 823–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.C. and Kane, P.M. (2009) The yeast lysosomes‐like vacuoles: endpoint and crossroads. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1793, 650–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lott, T.J. , Page, L.S. , Boiron, P. , Benson, J. and Reiss, E. (1989) Nucleotide sequence of the Candida albicans aspartyl proteinase gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 17, 1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry, O.H. , Rosebrough, N.J. , Farr, A.L. and Randall, R.J. (1951) Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 193, 265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez‐Espinoza, A.D. , León, C. , Elizarraraz, G. and Ruiz‐Herrera, J. (1997) Monomorphic nonpathogenic mutants of Ustilago maydis . Genetics, 87, 259–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez‐Soto, D. and Ruiz‐Herrera, J. (2013) Transcriptomic analysis of the dimorphic transition of Ustilago maydis induced in vitro by a change in pH. Fungal Genet. Biol. 58–59, 116–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechler, B. , Müller, M. , Müller, H. , Meussdoerffer, F. and Wolf, D.H. (1982) In vivo biosynthesis of the vacuolar Proteinases A and B in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae . J. Biol. Chem. 257, 11 203–11 206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercado‐Flores, Y. , Hernández‐Rodríguez, C. , Ruiz‐Herrera, J. and Villa‐Tanaca, L. (2003) Proteinases and exopeptidases from the phytopathogenic fungus Ustilago maydis . Mycologia, 95, 327–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercado‐Flores, Y. , Trejo‐Aguilar, A. , Ramírez‐Zavala, B. , Villa‐Tanaca, L. and Hernández‐Rodríguez, C. (2005) Purification and characterization of an intracellular aspartyl acid proteinase (pumAi) from Ustilago maydis . Can. J. Microbiol. 51, 171–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monod, M. , Hube, B. , Hess, D. and Sanglard, D. (1998) Differential regulation of SAP8 and SAP9, which encode two new members of the secreted aspartic proteinase family in Candida albicans . Microbiology, 144, 2731–2737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niimi, M. , Niimi, K. and Cannon, R.D. (1997) Temperature‐related expression of the vacuolar aspartic proteinase (APR1) gene and β‐N‐acetylglucosaminidase (HEX1) gene during Candida albicans morphogenesis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 148, 247–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parente, J.A. , Borges, C.L. , Bailão, A.M. , Felipe, M.S. , Pereira, M. and Soares, C.M. (2008) Comparison of transcription of multiple genes during mycelia transition to yeast cells of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis reveals insights to fungal differentiation and pathogenesis. Mycopathologia, 165, 259–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parr, C.L. , Keates, R.A. , Bryksa, B.C. , Ogawa, M. and Yada, R.Y. (2007) The structure and function of Saccharomyces cerevisiae proteinase A. Yeast, 24, 467–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichard, U. , Cole, G.T. , Rüchel, R. and Monod, M. (2000) Molecular cloning and targeted deletion of PEP2 which encodes a novel aspartic proteinase from Aspergillus fumigatus . Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 290, 85–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz‐Herrera, J. , León, C.G. , Guevara‐Olvera, L. and Cárabez‐Trejo, A. (1995) Yeast–mycelial dimorphism of haploid and diploid strains of Ustilago maydis . Microbiology, 141, 695–703. [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook, J. and Russell, D. (2001) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 3rd edn Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, I. , Hort, W. , Lang, S. and Mayser, P. (2010) Identification and characterization of differentially expressed genes associated with the production of hyphae in Malassezia furfur by cDNA‐subtraction technology. Mycoses, 53, 403. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez‐Rendueles, P. , Villa, L. , Arbesu, M.J. and Escudero, B. (1991) The proteolytic system of the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe . FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 81, 215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vartivarian, S.E. (1992) Virulence properties and nonimmune pathogenic mechanism of fungi. Clin. Infect. Dis. 14, 30–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez‐Laslop, N. , Tenney, K. and Bowman, B.J. (1996) Characterization of a vacuolar protease in Neurospora crassa and the use of the gene RIPing to generate protease‐deficient strains. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 21 944–21 949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. , Holden, D.W. and Leong, S.A. (1988) Gene transfer system for the phytopathogenic fungus Ustilago maydis . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 85, 865–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, T.C. and Agabian, N. (1995) Candida albicans secreted aspartyl proteinases: isoenzyme pattern is determined by cell type, and levels are determined by environmental factors. J. Bacteriol. 177, 5215–5221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolford, C.A. , Daniels, L.B. , Park, F.J. , Jones, E.W. , Van Arsdell, J.N. and Innis, M.A. (1986) The PEP4 gene encodes an aspartyl protease implicated in the posttranslational regulation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae vacuolar hydrolases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 6, 2500–2510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubenko, G.S. , Park, F.J. and Jones, E.W. (1983) Mutations in PEP4 locus of Saccharomyces cerevisiae block final step in maturation of two vacuolar hydrolases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 80, 510–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]