Summary

The evolution of resistance‐breaking capacity in pathogen populations has been shown to depend on the plant genetic background surrounding the resistance genes. We evaluated a core collection of pepper (Capsicum annuum) landraces, representing the worldwide genetic diversity, for its ability to modulate the breakdown frequency by Potato virus Y of major resistance alleles at the pvr2 locus encoding the eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E). Depending on the pepper landrace, the breakdown frequency of a given resistance allele varied from 0% to 52.5%, attesting to their diversity and the availability of genetic backgrounds favourable to resistance durability in the plant germplasm. The mutations in the virus genome involved in resistance breakdown also differed between plant genotypes, indicating differential selection effects exerted on the virus population by the different genetic backgrounds. The breakdown frequency was positively correlated with the level of virus accumulation, confirming the impact of quantitative resistance loci on resistance durability. Among these loci, pvr6, encoding an isoform of eIF4E, was associated with a major effect on virus accumulation and on the breakdown frequency of the pvr2‐mediated resistance. This exploration of plant genetic diversity delivered new resources for the control of pathogen evolution and the increase in resistance durability.

Keywords: Capsicum annuum, core collection, durability of resistance, genetic background, Potato virus Y (PVY)

The main limit to the use of resistant cultivars is the capacity of pathogens to counter‐adapt and overcome plant resistances. In this context, many research efforts have been devoted to handle the adaptation of plant pathogen populations and maintain the durability of resistant cultivars (Kiyosawa, 1982; McDonald and Linde, 2002; Mundt et al., 2002; Pink, 2002; Wolfe, 1985).

In several pathosystems involving virus, oomycete or nematode plant parasites, the durability of major resistance genes has been experimentally shown to be dependent on the genetic background in which it was introgressed (Acosta‐Leal and Xiong, 2008, 2013; Brun et al., 2010; Fournet et al., 2012; Palloix et al., 2009). In these studies, the breakdown frequency of the major resistance gene decreased when introgressed into a partially resistant cultivar, suggesting that the partially resistant genetic background was favourable to control pathogen evolution and enhance the durability of major resistance genes.

In the plant–virus system Potato virus Y (PVY)–pepper(Capsicum annuum), the protective effect of the genetic background on the breakdown frequency of the pvr23 gene, producing resistance to this virus, is mostly a result of the additional level of quantitative resistance, reducing viral accumulation (Quenouille et al., 2012). The breakdown frequency of the major gene has been shown to be highly heritable (i.e. it is mainly under genetic control) and affected by four quantitative trait loci (QTLs) (Quenouille et al., 2014). These results, obtained on a narrow plant genetic basis, i.e. in a progeny between two Capsicum annuum lines, have opened up new pathways for sustainable resistance breeding, but little is known about the availability of such QTLs and the frequency of favourable backgrounds in plant genetic resources.

In this context, the aim of our study was to estimate the availability and diversity of genetic backgrounds increasing the durability of pvr2‐mediated resistance on a broader genetic scale in pepper resources and to confirm (or not) the relationship with factors affecting quantitative resistance. Our strategy was to select a core collection of pepper landraces from different origins, but carrying two closely related pvr2 alleles, and to measure the resistance breakdown (RB) frequencies in these pepper accessions on the one hand, and the level of quantitative resistance controlled by their genetic backgrounds on the other hand.

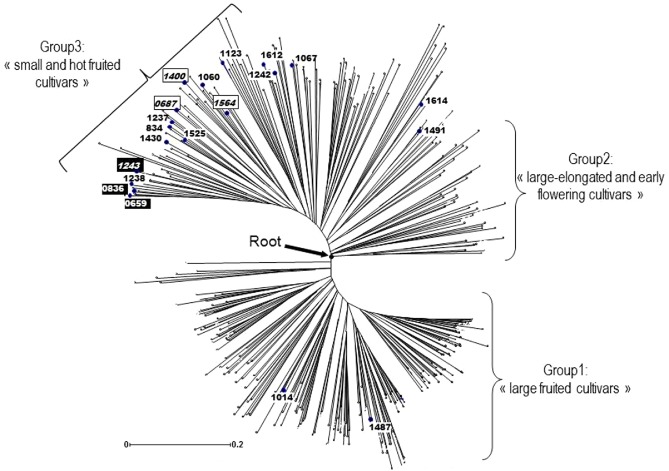

Selection of the Core Collection

The pepper (Capsicum spp.) germplasm collection maintained at INRA Unité de Génétique et Amélioration des Fruits et Légumes was screened for resistance to PVY, and 35.7% of the 862 tested accessions were found to be resistant (Sage‐Palloix et al., 2007). A subset of 107 resistant accessions was chosen whilst maximizing the diversity of their geographical origins, and were sequenced for the pvr2 resistance allele. Twenty‐one accessions carried the pvr23 allele, which was the most frequent allele, and five carried the pvr24 allele (Charron et al., 2008 and personal communication). The sequence of the eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) protein encoded by these two pvr2 alleles differs only by one amino acid substitution at position 205 (a glycine for pvr23 and an aspartic acid for pvr24). They displayed the same resistance specificity towards seven different PVY variants and were easily broken down compared with other pvr2 alleles (Ayme et al., 2007; Charron et al., 2008; Moury et al., 2014). To further test the durability of the pvr2 alleles in these different genetic backgrounds, we selected the accessions which were homozygous for pvr23 (16 accessions) or pvr24 (four accessions), whilst discarding the closely related accessions with identical genotypes at the tested simple sequence repeat (SSR) loci (Nicolaï et al., 2013), resulting in a final set of 20 C. annuum inbred lines issued from American, African and Asian pepper landraces (Table 1). The genetic diversity of this set of 20 C. annuum lines was compared with the genetic diversity of the entire C. annuum germplasm collection, which includes 1063 accessions from 89 different countries, using 28 SSR loci (Nicolaï et al., 2013). The wide distribution of the 20 inbred lines retained for resistance analysis across the phylogenetic tree representing the whole collection attested to their high diversity and poor genetic structure (Fig. 1). No shared origin was evidenced for the accessions carrying pvr23, which were widespread in the different parts of the tree, corresponding to large sweet or small and pungent fruited pepper landraces from diverse geographical origins. The four accessions carrying pvr24 were loosely grouped in the distal part of the tree, corresponding to small‐fruited pepper landraces. The 20 accessions represented 36.7% of the allelic richness present in the entire C. annuum collection (mean of 4.6 alleles for the 20 accessions compared with 12.6 alleles for the whole C. annuum collection at the 28 SSR loci; Nicolaï et al., 2013). These results indicate that, in spite of the choice based on two related pvr2 alleles, the retained 20 accessions carried diverse genetic backgrounds.

Table 1.

Frequency of resistance breakdown (RB), relative viral accumulation (VA) and area under the disease progress curve (AUDPC) for 20 pepper accessions carrying the pvr23 or pvr24 allele inoculated with Potato virus Y

| Accession code | Accession name | pvr2 allele | RB frequency (%) (n = 60)a | VA (n = 10)b | AUDPC (n = 20)b | Deletion in the pvr6 genec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM1237 | Piment de Thaïlande | pvr23 | 0a | 0.001a | 55cd | No |

| PM1123 | 276F | pvr23 | 0a | 0.006ab | 85gh | No |

| PM1242 | G1 | pvr23 | 0a | 0.010bc | 78fg | No |

| PM1614 | C69 | pvr23 | 0a | 0.063cde | 54c | No |

| PM0834 | AC 1448 | pvr23 | 0a | 0.103def | 67de | No |

| PM1238 | Piment Ile Maurice | pvr23 | 0a | 0.166efg | 72ef | No |

| PM1060 | PI 123 474 | pvr23 | 0a | 0.173efg | 69de | No |

| PM1430 | Pikuti | pvr23 | 0a | 0.202efg | 43b | No |

| PM1525 | Ubud Bali 2 | pvr23 | 0a | 0.215bcdefg | 43b | No |

| PM1491 | Copoya | pvr23 | 0a | 0.250efgh | 95h | No |

| PM1014 | Bousso 2 | pvr23 | 0a | 0.269bcdefgh | 70de | No |

| PM1564 | Beijin | pvr24 | 0a | 0.664gh | 61cd | No |

| PM1400 | P 709 | pvr24 | 1.6a | 0.014cd | 35a | No |

| PM1612 | Jaipur | pvr23 | 1.6a | 0.398efgh | 88gh | No |

| PM0659 | Perennial | pvr23 | 1.6a | 0.406fgh | 41b | Nt 89 to 170 |

| PM1067 | Huixtan | pvr23 | 1.6a | 0.416gh | 90h | No |

| PM1487 | Souman Boucoule 3 | pvr23 | 3.3a | 0.142efg | 71e | No |

| PM0687 | PI 322 719 | pvr24 | 5a | 1.010hi | 74ef | No |

| PM0836 | PI 369 940 | pvr23 | 40b | 2.141i | 74ef | Nt 89 to 170 |

| PM1243 | G4 | pvr24 | 52.5b | 2.804i | 75ef | Nt 89 to 170 |

Letters represent homogeneous groups identified by pairwise comparisons (Fisher exact tests at the 5% type‐I error threshold corresponding to a 0.00027 threshold after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons). RB frequency evaluated after inoculation with PVY CI chimera.

Letters represent homogeneous groups identified by pairwise comparisons (Wilcoxon tests at the 5% type‐I error threshold with Benjamini and Yekutieli correction). VA and AUDPC evaluated after inoculation with PVY CI chimera carrying the genome‐linked viral protein (VPg)‐N mutation.

In three accessions, an 82‐nucleotide (nt) deletion (from nucleotide 89 to 170) resulted in a premature stop codon and a truncated non‐functional eIFiso4E (Ruffel et al., 2006).

Figure 1.

Distribution of the accessions carrying pvr2 3 and pvr2 4 in the phylogenetic tree representing the genetic diversity of the Capsicum annuum germplasm collection (core collection of 378 accessions representing the C. annuum genetic diversity at 28 simple sequence repeat (SSR) loci and structure in three groups; Nicolaï et al., 2013). Tree produced using the unweighted neighbour‐joining method based on the dissimilarity matrix for the 28 SSRs (software DarWin‐6; Perrier and Jacquemoud‐Collet, 2006). Scale: dissimilarity index based on simple matching method. Accessions are labelled by their PM code as in Table 1. Non‐italicized are pvr2 3‐ and italicized are pvr2 4‐carrying accessions. Accessions in black boxes and white font are carrying the pvr6‐KO allele.

Breakdown Frequency of the Resistance Controlled by pvr23 or pvr24 in the Core Collection

To measure the RB frequency of pvr23 or pvr24 (pvr23/4), a recombinant PVY, the ‘CI chimera’, was mechanically inoculated to 60 seedlings per accession at the two expanded cotyledon stage in a climate‐controlled room at 20–22 °C and 12 h light/day. The CI chimera is a derivative of the SON41p infectious cDNA clone in which the CI‐coding region was substituted with that of the LYE84.2 infectious cDNA clone, both clones corresponding to isolates of the C1 clade of PVY (Montarry et al., 2011). This ‘CI chimera’ was chosen because of its greater ability to break down the pvr23 resistance compared with the parental clones, allowing more precise estimations and comparisons of the resistance durability of different plant genotypes (Montarry et al., 2011). The CI chimera is not infectious per se towards plants carrying pvr23/4 resistance alleles, i.e. in these plants, only mutants possessing single non‐synonymous substitutions in the genome‐linked viral protein (VPg) cistron could be detected, but not the ‘CI chimera’ itself. The susceptible line Yolo Wonder, carrying the pvr2+ susceptibility allele, was used as virus infectivity control, and the DH285 inbred line, carrying the pvr23 resistance allele and previously known for its high pvr23 RB frequency (Palloix et al., 2009), was used as a control for pvr23 RB capacity by the CI chimera. At 14 days post‐inoculation (dpi), all Yolo Wonder plants showed mosaic symptoms in apical leaves and all plants carrying pvr23/4 were symptom free. Mosaic or necrotic symptoms further appeared over the testing period in apical leaves of parts of the plants of some pvr23/4 accessions. At 35 dpi, three uninoculated leaves were sampled from each plant and pooled to test the presence of PVY by double‐antibody‐sandwich enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (DAS‐ELISA). In these conditions, each case of systemic infection in plants carrying the pvr23 resistance allele was shown to result from the selection of at least one PVY variant carrying an RB mutation(s) in the VPg cistron (Montarry et al., 2011). For each accession, the RB frequency was calculated from the frequency of systemically infected plants amongst inoculated plants. In this test, 80% of the DH285 resistant plants were broken down, attesting to the high capacity of the CI chimera to break down the pvr23 resistance in the test conditions. Among the 20 accessions, the RB frequency of pvr23/4 varied from 0% to 52.5% (Table 1), with highly significant differences between accessions (Pearson χ 2 test, P < 0.001). The 20 accessions were classified into two groups (pairwise Fisher exact tests at 5% type‐I error threshold after Bonferroni correction). For 18 accessions, the pvr23/4 resistance was not, or rarely, broken down (RB frequency ≤ 5%) and for the two accessions, PI369940 and G4, the pvr23/4 resistance was frequently broken down (40% and 52.5%, respectively). For PI369940 and G4, all infected plants were checked for the presence of RB mutations in the PVY VPg cistron: total RNA was extracted and the PVY VPg cistron was amplified by reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) and sequenced according to Moury et al. (2014). For one and four infected plants of G4 and PI369940, respectively, we failed to sequence the PVY VPg cistron. For the other 30 G4 and 20 PI369940 infected plants, all VPg sequences obtained differed from the initial VPg sequence of CI chimera by only one amino acid substitution. Four of the mutations detected have been found previously to result in the breakdown of pvr23 resistance (Ayme et al., 2006), four have been observed previously in pvr23 RB PVY populations and are strongly suspected to be responsible for RB (Montarry et al., 2011), and one has never been observed previously but was located at the same codon position (119) as three other observed mutations, also suggesting its involvement in RB (Table S1, see Supporting Information). Five G4 plants and one PI369940 plant were infected by a mixture of two single VPg mutants. These results confirmed the correspondence between systemic infection of plants carrying the pvr23/4 resistance allele after inoculation by CI chimera and occurrence of RB events. The high RB frequency was not associated with a particular allele at the pvr2 locus, as PI369940 carries pvr23 and G4 carries pvr24, suggesting that the differences observed between accessions most probably result from the effect of the plant genetic background. The low RB frequencies observed in 18 landraces indicated that genetic backgrounds favourable to the durability of pvr2‐mediated resistance are frequent among the genetic resources of pepper.

Differential Selection Pressure Exerted by the Plant Genetic Background

In a previous study (Montarry et al., 2011), 67% of the pvr23 RB events in DH285 were associated with the selection of the aspartic acid to asparagine codon substitution at position 119 of the VPg cistron of PVY (named VPg‐N mutation). In our test, we checked the presence of the VPg‐N mutation in 25 infected DH285 plants by derived cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence (dCAPS) analyses, as described in Montarry et al. (2011). The results showed that 64% of RB events of DH285 plants were associated with the presence of the VPg‐N mutation (Table 2), which is not significantly different from the previous results (P = 0.13, Fisher exact test). In G4 and PI369940 plants, the percentages of RB events associated with the selection of the VPg‐N mutation were equal to 55% (17/31) and 29% (7/24), respectively (dCAPS analyses showed the absence of the VPg‐N mutation in the five PVY populations from G4 or PI369940 plants for which the full sequence of the VPg cistron was not determined; Table S1). As a whole, this revealed a significant difference between PI369940 and DH285 (P = 0.020, Fisher exact test), but not between PI369940 and G4 (P = 0.10) or G4 and DH285 (P = 0.41), for the proportion of RB events associated with selection of the VPg‐N mutation. This variation cannot be associated with the effect of the pvr2 allele, as both PI369940 and DH285 carry pvr23 (and differ in the selection of VPg‐N mutation), whereas G4 (pvr24) and DH285 (pvr23) do not differ in their preferential selection of the VPg‐N mutation. The difference observed between PI369940 and DH285 can be associated with the genetic background, which selects more or less frequently the VPg‐N mutation. This result shows that various plant genetic backgrounds can exert differential selection pressure on RB mutants, leading to differential frequencies of selection of the various virulent mutants towards the same resistance allele.

Table 2.

Frequency of pvr23/4 resistance breakdown events associated with the selection of the aspartic acid to asparagine substitution at codon position 119 of the Potato virus Y (PVY) genome‐linked viral protein (VPg) cistron (VPg‐N mutation)

| Accession | Percentage of plants with VPg‐N mutation | Class* |

|---|---|---|

| PI369940 | 29 (7/24) | a |

| G4 | 55 (17/31) | ab |

| DH285 | 60 (16/25) | b |

*Classes represent homogeneous groups identified by pairwise Fisher exact tests at the 5% type‐I error threshold (corresponding to a 0.017 threshold after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons).

Quantitative Level of Resistance Controlled by the Genetic Background of the Pepper Accessions

It has been shown previously that a large part of the variation of the RB frequency of pvr23 observed in a biparental progeny could be attributed to the level of quantitative resistance conferred by the genetic background (Quenouille et al., 2014). To explore this relationship in an enlarged germplasm, we estimated the level of quantitative resistance conferred by the genetic backgrounds of each of the 20 pepper accessions. The pvr23/4‐breaking mutant of the CI chimera carrying the VPg‐N mutation was inoculated to 20 plants per accession. This RB mutant was chosen because it was the most frequently observed after RB of the pvr23 resistance by the CI chimera. It differed from the CI chimera by only one amino acid substitution (aspartic acid to asparagine) at position 119 of the VPg, allowing the breakdown of pvr23 and pvr24 and permitting the exclusion of the effect of pvr2‐mediated resistance in order to reveal the effect of the genetic background. Symptoms were assessed every 7 days until 35 dpi and, for each plant, the area under the disease progress curve (AUDPC) was calculated according to Caranta and Palloix (1996): symptom intensity from each plant was checked on the new developing leaves, with scores of 0 (no symptoms), 1 (weak mosaic) or 2 (severe mosaic or necrosis) at 7, 14, 21, 28 and 35 dpi. At 36 dpi, the relative virus accumulation (VA) was evaluated independently from 10 plants per accession by quantitative DAS‐ELISA by comparing the absorbance at 405 nm–dilution factor curves of each plant sample with that of a common reference virus sample (Ayme et al., 2006). Significant differences of VA and AUDPC were observed between accessions (P < 0.001, Kruskal–Wallis test) with means of VA varying from 0.001 to 2.804 and means of AUPDC varying from 35 to 95 (Table 1). Nine and eight groups of VA and AUDPC, respectively, were identified among the 20 pepper accessions (pairwise comparisons using Wilcoxon tests at 5% type‐I error threshold after Benjamini and Yekutieli correction), showing a large diversity of the level of quantitative resistance conferred by the accession's genetic backgrounds. No significant correlation was observed between VA and AUDPC (P = 0.3, Spearman correlation test). This lack of correlation between VA and AUDPC (or plant damage) has been observed previously for different plant–virus interactions (Araya et al., 2011 ; Moury et al., 2001; Pagán et al., 2007 ; Sáenz et al., 2000), and reveals different levels of tolerance between the 20 pepper accessions. Here, tolerance is defined as the capacity of the host plant to reduce the effect of an increase in VA on the plant fitness or damage (Råberg et al., 2007). In order to evaluate whether the resistance or tolerance level of the 20 accessions could affect the durability of pvr2‐mediated resistance, we examined the relationship between VA or AUDPC and the frequency of pvr23/4 RB. Two cultivars (G4 and PI369940) presented a high relative VA (>2.0) and simultaneously a high RB frequency (≥40%), whereas all other cultivars had a low VA (<1.1) and a low RB frequency (≤5%) (Table 1). This resulted in a highly significant positive correlation between VA and the frequency of pvr23/4 RB (P = 0.007, Spearman correlation test). A similar conclusion is reached if we consider only two categories of plant cultivars, those with high VA and high RB, and those with low VA and low RB. The probability that the plants belonging to the two categories of VA coincide exactly with the plants belonging to the two categories of RB by chance is given by P = (2/20)2 × (18/20)18 = 0.0015, a value quite similar to that obtained with the Spearman correlation test. In contrast, there was no significant correlation between AUDPC and the frequency of RB (P = 0.38, Spearman correlation test). This reveals a strong relationship between viral accumulation and the breakdown frequency of pvr2‐mediated resistance. A causal relationship can be hypothesized, as an increase in virus census population size will lead to an increase in the probability of appearance of virus mutants, and hence of mutant emergence. Our study broadens the results obtained by Quenouille et al. (2014), extending the relationship between the level of viral accumulation and the frequency of breakdown of pvr2‐mediated resistance previously observed in a pepper progeny to a pepper core collection with diversified genetic backgrounds.

Association between a Locus in the Pepper Genome and pvr23/4 RB Frequency

In the doubled haploid progeny issued from the F1 hybrid between the two pepper inbred lines Yolo Wonder and Perennial, we showed that the pvr6 gene encoding eIFiso4E, an isoform of eIF4E encoded by the pvr2 gene, co‐located tightly with a major QTL (R 2 = 0.40) affecting the pvr23 RB frequency and a major QTL (R 2 = 0.35) affecting viral accumulation (Quenouille et al., 2014). For these two QTLs located at the pvr6 locus, the Perennial alleles strongly increased the frequency of the pvr23 RB and VA. However, this effect was shown to be compensated by additional QTL alleles from the Perennial genetic background, so that Perennial always displayed an extremely low (or null) RB frequency. Compared with the Yolo Wonder pvr6+ allele, the pvr6 allele of Perennial carries an 82‐nucleotide deletion (from nucleotide 89 to 170) which modifies the open reading frame (ORF), leading to a premature stop codon and a truncated, non‐functional protein (Ruffel et al., 2006). To explore whether this ‘natural’ knockout (KO) of the pvr6 allele was present among the 20 pepper accessions, and whether it was associated with the observed variations in VA and pvr23/4 RB frequency, we sequenced the eIFiso4E cDNA of the 20 pepper accessions, as described in Ruffel et al. (2006). These sequences were aligned with the sequences of the Yolo Wonder pvr6+ allele (GenBank accession DQ022080) and the Perennial pvr6 allele (GenBank accession DQ022083) described in Ruffel et al. (2006). Alleles of the pvr6 gene carried by each pepper accession are indicated in Table 2. Among the 20 pepper accessions, three carried the same KO pvr6 allele: Perennial, PI369940 and G4. Interestingly, the two accessions PI369940 and G4, which showed a significantly higher RB frequency of pvr23/4 and the two highest VA values, carried the KO pvr6 allele. In contrast, all plants carrying the pvr6+ allele encoding a functional eIF(iso)4E protein displayed a low to very low RB frequency and a varying but lower VA. The pvr6 allele is also present in the Perennial accession, which showed a very low RB frequency, and this could invalidate the causal relationship between pvr6 alleles and both RB frequency and VA. However, Quenouille et al. (2014) showed that, in Perennial, the effect of the QTL allele at the pvr6 locus was compensated by three other QTLs that decreased the pvr23 RB frequency and VA. Taken together, these results show that the pvr6 gene is a good candidate to explain the observed variation in pvr2 RB frequency and VA. The high frequency of pvr23/4 RB observed in G4 and PI369940 could be interpreted as an effect of the pvr6 KO allele, which increased both VA and RB frequencies, without compensation effects from other QTLs in the genetic background, as observed in Perennial. This simultaneous increase in VA and RB may result from a higher expression of eIF4E encoded by pvr2 3/4 because of the absence of the eIFiso4E isoform encoded by pvr6, as shown in Arabidopsis thaliana (Duprat et al., 2002). Indeed, this higher eIF4E expression could increase its availability for PVY replication and/or translation, possibly by reducing competition effects between PVY VPg and the cap of plant mRNAs (Michon et al., 2006). In turn, higher virus multiplication would lead to higher VA in the case of an RB PVY mutant, and higher probability to generate RB mutants in the case of a wild‐type PVY. However, such a hypothetical mechanism still needs to be demonstrated and functional validation of the involvement of pvr6 in RB and VA will help in this exploration. The compensatory effect by additional resistance QTLs from Perennial has been shown to act at several levels (Quenouille et al., 2012): they have been shown to directly reduce VA, but also to increase the number of viral mutations required for RB. Finally, they slowed down the selection and fixation of RB mutations in the PVY population.

Conclusion

This study provides the first evaluation of the availability, in plant genetic resources, of genetic backgrounds affecting the durability of major resistance genes. Among a core collection of 20 pepper accessions, we observed a high diversity of quantitative resistance and of tolerance levels conferred by the genetic background. In terms of durability of the pvr23 and pvr24 major resistance alleles, the pepper accessions were divided into two groups, with either no or rare breakdown or with frequent breakdown, the latter group including only two pepper accessions. The genetic backgrounds favourable to the durability of pvr2‐mediated resistance were carried by genetically distant landraces from diversified origins, indicating that such favourable genetic combinations are not only frequent, but also widespread, in the pepper genetic resources. The relationship between the pvr23/4 RB frequency and the level of quantitative resistance in a diversified core collection extends the previous results, which showed that the RB frequency of a major gene is reduced when introgressed into a partially resistant cultivar (Brun et al., 2010; Fournet et al., 2012; Palloix et al., 2009) or combined with another major resistance gene (Acosta‐Leal and Xiong, 2008, 2013), and that the same QTLs or genes may affect quantitative resistance and major gene durability (Acosta‐Leal and Xiong, 2008; Quenouille et al., 2014). This former QTL analysis, together with the analysis of the eIFiso4E coding sequence in the core collection, leads us to suggest that the observed variations in RB frequency are strongly affected by the plant allele at the pvr6 locus. However, the genetic background effect cannot be reduced to this single locus as this major effect can be compensated by additional quantitative resistance QTLs. This indicates that breeding ‘accidents’ could happen when a major resistance gene is introgressed into a new genetic background. However, such accidents can be avoided if the major resistance gene is introgressed into a partially resistant cultivar, taking into account that quantitative resistance must be evaluated through the pathogen accumulation level, as symptom expression or tolerance level was not correlated with RB frequency. Another interesting output was delivered by the distribution of the different RB mutants, which differed between pepper landraces, suggesting that selection pressures could be modulated as a result of different plant genetic backgrounds. The availability of plant genetic backgrounds with contrasting differential effects on pathogen populations paves the way towards a durable management of resistance genes by the breeding of appropriate cultivars and deploying appropriate varietal mixtures to control the emergence of the different RB variants.

Supporting information

Table S1 Distribution of genome‐linked viral protein (VPg) mutations in Potato virus Y (PVY) populations infecting G4 (pvr2 4/pvr2 4) or PI369940 (pvr2 3/pvr2 3) pepper (Capsicum annuum) genotypes.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank G. Nemouchi and V. Simon for technical assistance, and A. M. Sage‐Palloix (CRB‐Leg, INRA‐GAFL, Montfavet Cedex, France) for providing the Capsicum genetic resources. This work was supported by Gautier‐Semences and funded by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (Project VirAphid ANR‐2010STRA‐001‐01), the Région Provence Alpes Côte d'Azur (PACA) and the INRA‐Meta Programme SMaCH (Sustainable Management of Crop Health).

References

- Acosta‐Leal, R. and Xiong, Z. (2008) Complementary functions of two recessive R‐genes determine resistance durability of tobacco ‘Virgin A Mutant’ (VAM) to Potato virus Y . Virology, 379, 275–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acosta‐Leal, R. and Xiong, Z. (2013) Intrahost mechanisms governing emergence of resistance‐breaking variants of Potato virus Y . Virology, 437, 39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araya, C. , Peña, E. , Salazar, E. , Román, L. , Medina, C. , Mora, R. , Aljaro, A. and Rosales, I.M. (2011) Symptom severity and viral protein or RNA accumulation in lettuce affected by big‐vein disease. Chilean J. Agric. Res. 71, 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ayme, V. , Souche, S. , Caranta, C. , Jacquemond, M. , Chadoeuf, J. , Palloix, A. and Moury, B. (2006) Different mutations in the genome‐linked protein VPg of potato virus Y confer virulence on the pvr23 resistance in pepper. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 19, 557–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayme, V. , Petit‐Pierre, J. , Souche, S. , Palloix, A. and Moury, B. (2007) Molecular dissection of the Potato virus Y VPg virulence gene reveals complex adaptations to the pvr2 resistance allelic series in pepper. J. Gen. Vir. 88, 1594–1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brun, H. , Chèvre, A.‐M. , Fitt, B.D. , Powers, S. , Besnard, A.‐L. , Ermel, M. , Huteau, V. , Marquer, B. , Eber, F. , Renard, M. and Andrivon, D. (2010) Quantitative resistance increases the durability of qualitative resistance to Leptosphaeria maculans in Brassica napus . New Phytol. 185, 285–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caranta, C. and Palloix, A. (1996) Both common and specific genetic factors are involved in polygenic resistance of pepper to several potyviruses. Theor. Appl. Genet. 92, 15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charron, C. , Nicolaï, M. , Gallois, J. , Robaglia, C. , Moury, B. , Palloix, A. and Caranta, C. (2008) Natural variation and functional analyses provide evidence for co‐evolution between plant eIF4E and potyviral VPg. Plant J. 54, 56–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duprat, A. , Caranta, C. , Revers, F. , Menand, B. , Browning, K.S. and Robaglia, C. (2002) The Arabidopsis eukaryotic initiation factor (iso)4E is dispensable for plant growth but required for susceptibility to potyviruses. Plant J. 32, 927–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournet, S. , Kerlan, M.C. , Renault, L. , Dantec, J.P. , Rouaux, C. and Montarry, J. (2012) Selection of nematodes by resistant plants has implications for local adaptation and cross‐virulence. Plant Pathol. 62, 184–193. [Google Scholar]

- Kiyosawa, S. (1982) Genetics and epidemiological modeling of breakdown of plant disease resistance. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 20, 93–117. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, B.A. and Linde, C. (2002) Pathogen population genetics, evolutionary potential, and durable resistance. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 40, 349–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michon, T. , Estevez, Y. , Walter, J. , German‐Retana, S. and Le Gall, O. (2006) The potyviral virus genome‐linked protein VPg forms a ternary complex with the eukaryotic initiation factors eIF4E and eIF4G and reduces eIF4E affinity for a mRNA cap analogue. FEBS J. 273, 1312–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montarry, J. , Doumayrou, J. , Simon, V. and Moury, B. (2011) Genetic background matters: a plant–virus gene for gene interaction is strongly influenced by genetic contexts. Mol. Plant Pathol. 12, 911–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moury, B. , Cardin, L. , Onesto, J.‐P. , Candresse, T. and Poupet, A. (2001) Survey of Prunus necrotic ringspot virus in rose and its variability in rose and Prunus spp. Phytopathology, 91, 84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moury, B. , Janzac, B. , Ruellan, Y. , Simon, V. , Ben Khalifa, M. , Fakhfakh, H. , Fabre, F. and Palloix, A. (2014) Interaction patterns between Potato virus Y and eIF4E‐mediated recessive resistance in the Solanaceae. J. Virol. 88, 9799–9807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundt, C. , Cowger, C. and Garrett, K. (2002) Relevance of integrated disease management to resistance durability. Euphytica, 124, 245–252. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaï, M. , Cantet, M. , Lefebvre, V. , Sage‐Palloix, A.M. and Palloix, A. (2013) Genotyping a large collection of pepper (Capsicum spp) with SSR loci brings new evidence for the wild origin of cultivated C. annuum and the structuring of genetic diversity by human selection of cultivar types. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 60, 2375–2390. [Google Scholar]

- Pagán, I. , Alonso‐Blanco, C. and García‐Arenal, F. (2007) The relationship of within‐host multiplication and virulence in a plant–virus system. PLoS ONE, 2, e786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palloix, A. , Ayme, V. and Moury, B. (2009) Durability of plant major resistance genes to pathogens depends on the genetic background, experimental evidence and consequences for breeding strategies. New Phytol. 183, 190–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrier, X. and Jacquemoud‐Collet, J.P. (2006) DARwin software. Available at: http://darwin.cirad.fr/.

- Pink, D. (2002) Strategies using genes for non‐durable disease resistance. Euphytica, 124, 227–236. [Google Scholar]

- Quenouille, J. , Montarry, J. , Palloix, A. and Moury, B. (2012) Farther, slower, stronger: how the plant genetic background protects a major resistance gene from breakdown. Mol. Plant Pathol. 14, 109–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quenouille, J. , Paulhiac, E. , Moury, B. and Palloix, A. (2014) Quantitative trait loci from the host genetic background modulate the durability of a resistance gene: a rational basis for sustainable resistance breeding in plants. Heredity, 112, 579–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Råberg, L. , Sim, D. and Read, A.F. (2007) Disentangling genetic variation for resistance and tolerance to infectious diseases in animals. Science, 318, 812–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruffel, S. , Gallois, J.‐L. , Moury, B. , Robaglia, C. , Palloix, A. and Caranta, C. (2006) Simultaneous mutations in translation initiation factors eIF4E and eIF(iso)4E are required to prevent pepper veinal mottle virus infection of pepper. J. Gen. Virol. 87, 2089–2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sáenz, P. , Cervera, M.T. , Dallot, S. , Quiot, L. , Quiot, J.B. , Riechmann, J.L. and Garcia, J.A. (2000) Identification of a pathogenicity determinant of Plum pox virus in the sequence encoding the C‐terminal region of protein P3+ 6K1. J. Gen. Virol. 81, 557–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage‐Palloix, A.M. , Jourdan, F. , Phaly, T. , Nemouchi, G. , Lefebvre, V. and Palloix, A. (2007) Structuring genetic diversity in pepper genetic resources: distribution of horticultural and resistance traits in the inra pepper germplasm In: Progress in Research on Capsicum & Eggplant (Niemirowicz‐Szczytt K., ed.), pp. 33–42. Warsaw: University of Life Sciences Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, M. (1985) The current status and prospects of multiline cultivars and variety mixtures for disease resistance. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 23, 251–273. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Distribution of genome‐linked viral protein (VPg) mutations in Potato virus Y (PVY) populations infecting G4 (pvr2 4/pvr2 4) or PI369940 (pvr2 3/pvr2 3) pepper (Capsicum annuum) genotypes.